Chapter XI: The China–Burma–India Theater, August 1943–January 1945

QUADRANT Directs an All-out Effort

Plans for CBI

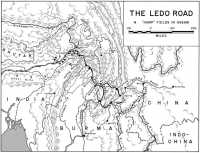

A change for the better for the engineers in CBI seemed to be at hand. Meeting in the QUADRANT Conference at Quebec from 14 to 24 August 1943 to discuss world strategy, the Anglo-American high commands gave much thought to operations in the China–Burma–India theater. The Combined Chiefs, assuming that the Chinese trained and rearmed by Stilwell would eventually link up with U.S. forces in southeastern China, agreed to commit enough British and U.S. strength to the theater to keep China in the war as an effective ally and as a base for operations against Japan. To facilitate strengthening China, they directed the capture of the northern part of Burma in order to increase the safety of flights over the Hump and to make possible the restoration of overland communications by mid-February 1944.1 Much thought was given to developing the line of communications from India to China. Somervell went into this matter with the Quartermaster General of the British Army, Sir Thomas Riddell-Webster. The two worked out a comprehensive program for improving logistical support for the Chinese war effort. Their plans called for an increase in deliveries over the Hump to 20,000 tons a month by mid-1944. There would have to be a redoubled effort to open the Ledo and Burma Roads to make possible trucking 30,000 tons of supplies a month to China by January 1945.2

Plans for constructing a pipeline from India to China figured prominently in the talks. To ship sufficient quantities of fuel to China by truck and plane to support a sustained drive against the Japanese would be impossible. “The old Burma Road ate its head off in gasoline,” Merrill had declared at TRIDENT. “A pipeline is the only way to cure this.”3 Construction of a pipeline system in a combat zone might have met with insurmountable obstacles had it not been for improvements, such as the Shell Oil Company’s invasion-weight pipe. This

pipe was thin-walled, portable, and weighed about half as much as standard pipe. There were two sizes—one, four inches in diameter; the other six. Each piece of pipe was twenty feet long. A piece of 4-inch pipe weighed about go pounds; of 6-inch, about 150. The sections were not welded together as were those of standard weight, but were joined by “victaulic couplings.” These were collars with rubber gaskets, made tight by the pressure of the oil or gasoline flowing through the pipes. A mile of invasion-weight pipeline together with pumping stations weighed thirteen tons. Pipe and stations could be easily transported and installed in any kind of terrain accessible to trucks. Improved types of submarine lines, ship-to-shore loading equipment, and bolted steel tanks holding 250, 500, or 1,000 barrels had also been developed. In July 1943 the Office of the Chief of Engineers reported that construction of a 4-inch, invasion-weight pipeline from the town of Dibrugarh on the Brahmaputra River in Assam through the mountains of northern Burma to Fort Hertz and on to Kunming was practicable.4 The QUADRANT Conference approved construction of a line via Fort Hertz which would skirt enemy-held territory and would be used mainly to supply gasoline to Chennault’s air force. The Combined Chiefs further approved the laying of a second 4-inch invasion-weight line; this one would follow the Ledo and Burma Roads to supply gasoline to trucks hauling supplies from India to China. In addition, the Combined Chiefs directed that two 6-inch pipelines be put in, one to extend from Calcutta to Kunming via the Ledo and Burma Roads to provide gasoline for American and Chinese ground operations, and the other to run from Calcutta to Dibrugarh to feed the 4-inch lines. When finished, these 4- and 6-inch lines would form the most extensive pipeline system in the world.5

The QUADRANT Conference also took up the matter of guerrilla warfare. British Brigadier Orde C. Wingate, who had carried on such warfare in Burma, had come to Quebec to support Churchill’s arguments for broadening the scope of commando operations behind enemy lines. Wingate was convinced that in his recent campaigning he had developed a method of harassment that would cripple Japanese defenses. He proposed to augment his specially trained brigades of Chindits—named after the mythical lion-like animals which guarded Burmese temples and made up of natives of India, whites from the British Isles, and Negroes from West Africa—so that they could strike really effective blows. He wanted to improve the means of sending his forces behind enemy lines by air. Given enhanced mobility and dependable air supply, Wingate was certain the Chindits could harry the Japanese sufficiently to force them out of northern Burma. The Allied commanders approved his proposals. General Marshall directed the assembling of an American task force of

some 3,000 volunteers who would serve with the Chindits. General Arnold promised to supply pilots from the AAF to fly the planes Wingate said he needed. He directed Air Force Col. Philip G. Cochran to go to India in the autumn to organize these men into the 5318th Air Unit, which would be a “custom-made” aggregation of bombers, fighters, transports, gliders, and helicopters. It would be up to the engineers to provide the landing fields for the air commandos behind the enemy lines. Wingate would carry on guerrilla warfare in Burma while the Chinese under Stilwell launched their full-scale offensive.6

General Arnold announced a project at the conference which was destined to have a tremendous impact on the engineer mission in CBI. The Army Air Forces had almost perfected the B-29 or “superfortress” bomber, which was to be capable of delivering 10 tons of bombs on a target 1,500 miles away. Arnold informed the Combined Chiefs that the first B-29’s would be ready during the coming winter. If bases could be provided in the Changsha area of China, midway between Kunming and Shanghai, the Air Forces would be ready to launch a massive assault on Japan by October 1944. This plan of overwhelming Japan with fleets of super-bombers appealed to the imagination of the President. The number of fields to be built was left rather indefinite and methods of providing logistic support were not clearly formulated. Planning staffs in Washington and in the theater would have to work out the details in the next few months. Roosevelt believed that if the plan could be carried out as Arnold proposed, there would be a material improvement in Chinese morale and an early end of the war with Japan.7

Theater Reorganization

The decisions at Quebec were undertaken simultaneously with two basic changes in the Allied command structure in the theater designed to promote more effective use of resources. Hoping to eliminate some of the confused relationships of the existing “loose coalition of Allied headquarters,” Roosevelt and Churchill agreed to set up the Southeast Asia Command. Vice Adm. Lord Louis Mountbatten was named commander. With his main forces based in India, he would control Anglo-American operations in Burma. Stilwell’s position in the new setup was not clear. He would be under Mountbatten insofar as operations in Burma were concerned, and it was generally assumed he would be Mountbatten’s deputy, but there was no official confirmation of this assumption. Arnold’s chief of staff, Maj. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer, was to go to CBI as Stilwell’s air adviser. He was appointed commanding general of U.S. Army Air Forces, India-Burma Sector, and as such was the ranking American air officer in the theater. Under him

was Tenth Air Force, commanded, after General Bissell’s return to the United States in mid-August, by Brig. Gen. Howard C. Davidson. Stratemeyer, arriving in the theater in August, set up his headquarters near Calcutta. He soon learned that he would have little control over Chennault. Roosevelt had assured Chiang that Stratemeyer would not interfere with the operations of the Fourteenth Air Force, and Stilwell exempted Chennault from Stratemeyer’s operational control. To most observers, command relationships in CBI remained as involved as before, and the complexities of the engineer organization as great as ever.8

The growing emphasis on air power led to the organization of engineer offices in the Air Forces in CBI for the first time. On 15 August Col. Herman W. Schull, Jr., organized an Engineer Section in Chennault’s Fourteenth Air Force headquarters at Kunming. Schull and his one assistant were henceforth responsible for maintaining liaison with the Services of Supply regarding the building or maintenance of five airfields in Yunnan and ten in eastern China, together with a dozen reserve fields in widely scattered localities. A similar development took place in India. On zo August Stilwell activated the CBI Air Service Command with headquarters near Calcutta, to succeed the X Air Force Service Command. The new organization was charged with supporting the Tenth Air Force in India and the Fourteenth in China. Col. Lyle E. Seeman, who arrived from the United States in the summer of 1943, became the first engineer of the new organization. At the same time he became theater air engineer under Stratemeyer. Like Schull in China, Seeman, with his small staff, maintained liaison with SOS on airfield construction in India.9

Planning for New Operations

Because of the shortage of planning staffs in the theater, Army Service Forces in Washington had to assume the main burden of planning for the line of communications projects the Combined Chiefs had approved. This responsibility Somervell and his staff accepted with enthusiasm. Styer wrote that the “development of the line of communications from India to China bids fair to be the greatest engineering undertaking of the war. ...”10 Early in September, Somervell established the India Committee. It included specialists from the technical services. The committee’s job, Somervell said, was to keep ASF “in a position at all times to back up and even anticipate the demands which are made on us in the way of men and materials.”11

The principal representatives of the Corps of Engineers on the committee were Col. Louis G. Horowitz, for theater liaison, Col. Thomas F. Farrell, for construction, and Col. Harry A. Montgomery, for supply.

With such cooperation as the CBI staffs could give, headquarters in Washington worked at top speed during the autumn to get men and supplies to the theater. Somervell was determined to obtain for the Ledo Road its full allotment of eighteen engineer construction battalions. As of September 1943 only six were in the theater. Subject to the availability of shipping and the troop priority lists established by Stilwell, Somervell intended if possible to have the entire eighteen on the road by the following January.12 The Corps of Engineers expanded the Petroleum Section of the Engineer Unit Training Center at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana; nine petroleum distribution companies were to be trained and readied for shipment to India by early 1944.13 General Godfrey, the Army Air Forces engineer, was deeply interested in a number of projects scheduled for CBI. At his urging, General Arnold directed that the headquarters of an aviation regiment and four aviation battalions be sent to the theater for work on the B-29 fields. Godfrey, having played a key role in securing the adoption of airborne engineer units by the Army in the summer of 1942, was especially interested in Wingate’s plans for the air commandos. He was largely instrumental in getting air borne engineers assigned to the commandos for the coming campaign in Burma.14

In procuring supplies and equipment for road and pipeline construction, Somervell’s hand was greatly strengthened by the fact that Army Service Forces had already assembled many of the materials needed; they had been intended for the now-abandoned line of communications from Rangoon to Kunming. All of the pipe required for the 4-inch line via Fort Hertz was en route to the theater by late August. Nearly a fourth of the 900 miles of 6-inch pipe and accessories which ASF had originally ordered for the line from Bhamo to Kunming was on its way. Of the 55,715 tons of road construction equipment requested by Wheeler during 1942 and 1943, all was either en route or being procured by Army Service Forces by 1 September. Since additional pumping stations and pipe would be needed, the Corps of Engineers undertook procurement during September and October.

It soon became evident that the B-29 program would have to be curtailed. It ran aground on the shoals of logistics. Having the fields at Changsha would mean developing a line of communications from Calcutta to Kunming of a magnitude and at a speed not contemplated by the Combined Chiefs. The supply effort required would be herculean. As modified by Stilwell and Stratemeyer in October and November, the MATTERHORN project called for the construction of five air bases west of Calcutta and four staging fields near the

city of Chengtu in Szechwan Province, northwest of Chungking. This reduced program would move up the advent of the bomber offensive to the spring of 1944, but mass bombings would have to be given up in favor of careful selection of strategic targets, such as Japanese steel mills and aircraft factories.15

The preparations being made in the United States soon had their repercussions in the theater. The engineers had to make still greater efforts to meet the goals set by the QUADRANT Conference. Work on old projects had to be speeded up and new ones begun. Whether much more could be done until more troops arrived was doubtful. Highly desirable would be a better organization of the theater. In any case, by the fall of 1943 there was a noticeable quickening of engineer work in the theater from eastern China to western India.

Airfields in China and India

In eastern China, Byroade continued to supervise construction of the fields near Kweilin and began to improve several more about 200 miles to the east and southeast. In this part of China, the engineers, as before, met with unexpected developments. Outside Kiangsi Province, where the local authorities were not so fully in control, “uncertified contractors” were permitted to start work on some of the fields. Soon organized gangs were carrying out systematic acts of violence and intimidation against contractors and workers alike with little or no interference on the part of the authorities. A number of additional contractors were subsequently “certified,” after they indicated they were willing to share profits with local officials. Despite such hindrances, progress was made in construction. During the autumn Byroade presented Chennault with 5 improved fields near Kweilin and 7 more zoo miles farther east and southeast. By this time SOS engineers in China were responsible for maintaining 27 fields for Chennault.16

The fields in Assam, upon which so much work had been done to make possible flying larger tonnages to Chennault, also showed progress. This improvement was accompanied by high-level struggles in the final, critical phases of the construction effort. The British, pointing to the top priority assigned by the Combined Chiefs to ground operations scheduled for 1943, explained that it would be necessary to withdraw their military engineers from Assam for duty on the line of communications supporting the British forces facing southern Burma. Stilwell and Wheeler were able early in October to convince them that a wholesale withdrawal would be uneconomical. The British agreed to leave their engineers on the most important of the remaining uncompleted fields. Late that year the Air Transport Command had available ten fields along the upper Brahmaputra.17

With more fields in India and China to

give him support, Chennault in October was able to make a more effective showing. Deliveries of supplies over the Hump increased, and two additional fighter squadrons arrived. After the failure of his trial offensive in August and September, Chennault now found the going much easier. He began to take the initiative in China’s eastern skies. In the last quarter of 1943 his flyers carried out highly successful strikes against Japanese shipping on the Yangtze and off the China coast.18

The Ledo Road

Meanwhile, the engineers in Base Section 3 labored to provide the overland communications indispensable for expanded operations in China and Burma. Inasmuch as Arrowsmith’s successor was a Quartermaster officer, supervision of work on the road now rested largely with Col. Robert E. York, road engineer since 21 May. The return of the 45th Engineers from their rest camp near Calcutta early in September and the tapering off of the monsoon gave Colonel York a chance to push road construction once more. With the 330th Engineers breaking the trail and doing the advance grading and the 45th Engineers doing the final grading and graveling, the Ledo Road inched southward through the jungle and defiles of north-western Burma, despite the 23 inches of rain that fell during the remainder of the month.19 By 15 October the lead bulldozer had advanced nearly seven miles and was beyond Mile 60.20 By this time there were on the road 2 general service regiments, 3 aviation battalions, and one engineer maintenance company, about 5,250 engineers in all.21

On 17 October a new chapter began in the history of the road. Col. Lewis A. Pick, Missouri River Division engineer, arrived to take command of Base Section 3.22 He lost no time in inaugurating a new order of things. On the evening of his arrival, he bluntly told his assembled staff, “I’ve heard the same story all the way from the States. It’s always the same—the Ledo Road can’t be built. Too much mud, too much rain, too much malaria. From now on we’re forgetting this defeatist spirit. The Ledo Road is going to be built—mud, rain, and malaria be damned!”23 Pick set up his command tent near the roadhead. He reinstituted the around-the-clock schedule that General Arrowsmith had been forced to abandon five months before with the onset of the rains. Pick was determined to brook no obstacle to the speedy advance of the road. He sought to provide adequate lighting for work at night by stripping the base of all generators, wiring, sockets, and bulbs that could possibly be spared. He told the troops that if necessary they were to put flares in buckets of oil. Work would have to go on without interruption.24

Pick believed that one of his first jobs

was to relieve the forward elements on the road. The day before his arrival, orders had gone out withdrawing Company D of the 330th Engineers from the roadhead. This unit, which had spearheaded the advance since early July, had been reduced to a handful of men by malaria and dysentery. Its removal for rest and recuperation was clearly necessary. On 1 November Pick lauded Company D for displaying a fortitude “comparable to that cited for combatant troops.” Shortly afterward, he began pulling back the rest of the 2nd Battalion for road maintenance and improvement south of Pangsau Pass. By 14 November he had moved up the 1st Battalion of the 330th to take the lead. The roadhead stood at Mile 63. The advance was about to begin in earnest.25

Early in November Stilwell visited road headquarters. He impressed on Pick the urgent importance to the tactical plan of having a jeep trail open to Shingbwiyang by the first of the year.

“I can’t build you a jeep road,” Pick replied, mindful of the difficulty of maintaining a narrow track in the swampy jungle, “but I’ll build you a military highway to handle truck traffic.” With Pick’s assurance that such a road could be built to Shingbwiyang by 1 January 1944, Stilwell took him up on it.26 In mid-November, the 330th and the Chinese 10th engineers at Mile 63 began the 54-mile “race to Shingbwiyang,” by breaking a path through the jungle. To the rear, the 45th Engineers were joined by a number of newly arrived units. The 849th and 1 883rd Aviation Battalions helped with final grading and graveling from Pangsau Pass southward. The 209th Combat Battalion operated a sawmill, did road maintenance at the pass, and a little farther south built a 157-foot-long girder bridge over the Nawngyang River. The 823rd engineers maintained the older sections of the road, while the 479th Maintenance Company repaired equipment. With the help of Company C of the 45th Engineers, which had made an overland trek to open an advanced roadhead at Mile 70 early in October, the 330th had pushed its lead bulldozer twenty-two miles beyond that point by the close of November.27

Under Lt. Col. William J. Green, who became road engineer on 3 December, progress was rapid. Favored by generally clear weather, the 330th Engineers gradually improved their performance until they attained early in December an average of a mile a day. The units to the rear maintained the pace set by the those in the lead. Specifications called for a minimum width of twenty-seven feet, shoulder to shoulder, with a 20-foot roadway, maximum grades of 10 percent, and a minimum curve radius of fifty feet. Accounting for the rapid progress in construction were various factors, including around-the-clock operations, the trickling forward of new equipment, and Pick’s insistence on constant supervision of construction and maintenance by all commanders and on giving junior officers

a detailed insight into the planning behind each phase of the work. The ingenuity of maintenance crews made up somewhat for the scarcity of spare parts but was not equal to the task of preventing entirely the continual deterioration of the heavy equipment, too long in constant use. At any rate, by making the best use of the equipment they had and by throwing fresh grading parties from the recently arrived 1905th Engineer Aviation Battalion to create new roadheads, Green pushed his trace to within eleven miles of Shingbwiyang by 23 December. The engineers now pressed forward through the remaining stretch. Green split the 330th to put in advance roadheads and organized two more grading parties. Shortly before noon on 27 December, the 330th engineers connected their traces 3 miles north of the town. Pick flashed the word to New Delhi that the 117-mile road from Ledo to Shingbwiyang was open. He then rode into town at the head of a convoy of jeeps and trucks. He had beaten his target date of 1 January by five days. Finished grading and graveling remained to be done, but the road from Ledo to Shingbwiyang, which Stilwell wanted, was open.28

Soon after his arrival in the theater, Pick had taken steps to begin work on that part of the pipeline system for which he was responsible. Wheeler had informed him that Stilwell was no longer

interested in a line over the mountains by way of Fort Hertz. Early in October the Chief of Engineers had recommended against using the light, invasion-weight pipe in the high elevations of the China-Burma divide. Consequently, on the 16th Stilwell had gone back to the original plan of putting the pipeline along the road. Because materials could be moved forward more easily there, construction would be simplified. Pick had a considerable stock of 4-inch pipe in his warehouses, but no troops to build the line were scheduled to arrive before January.29 Determined not to waste two months of good construction weather, he decided to use men from the 330th Engineers and from the recently arrived 209th Combat Battalion and 382nd Construction Battalion. On 27 October he put the men to work laying pipe from the refinery at Digboi, toward Ledo, fourteen miles to the south. Early in November Col. Kenneth MacIsaac, who had recently arrived from the United States with a staff of four petroleum engineers, took charge of the project. Almost totally inexperienced in this type of construction, the troops under MacIsaac caught on quickly. The line was soon complete to Ledo and was being extended down the road. The men were laying an average of 1.2 miles of pipe a day. The rate slowed down when they reached the mountains, where they rarely laid more than half a mile a day. By the last week of December, the pipeline crews had almost caught up with the graveling details at Mile 60.

Thereafter, MacIsaac slowed the pace of the advance to that of the gravel-head in order not to hamper the forward elements on the road.30

Stilwell’s campaign in northern Burma had gotten off to a premature start on 16 October. The tactical plan called for the Chinese to advance from Shingbwiyang to the Tarung River, which flowed in a southerly direction about twenty miles to the east. From the Tarung, Stilwell’s forces were to drive southward on 1 December toward the town of Myitkyina, some 140 miles away. Myitkyina was the main operational base for the Japanese forces holding northern Burma. Astride the route planned for the Ledo Road, it was a key rail terminus. Near the outskirts of the town was a vitally important airfield. Operations against the Japanese did not develop as planned. On 30 October the Chinese ran into unexpectedly strong enemy formations on the west bank of the Tarung. What was to have been a quiet “forward displacement” became a seesaw struggle.31 The possibility of a counterattack against Shingbwiyang and the roadhead had loomed large in the minds of the engineers near the front. Writing to Pick on 14 December, Lt. Col. William E. Hicks, executive officer of the 330th Engineers, complained that his forward battalion, approaching Shingbwiyang, had only piecemeal information on the location and status of the front. Liaison of the engineers with the ground forces was practically nonexistent, Hicks declared, and the air-raid warning system was totally inadequate insofar as his forward elements were concerned. On 30 December Hicks reiterated his fears, but by the time his letter reached Ledo the Chinese had scored a signal victory at Yupbang Ga. This triumph clinched their hold on the line of the Tarung.32

The Burma Road

Prospects in late 1943 for opening a line of communications in Assam and Burma appeared brighter, but such was not the case in western China. Colonel Dawson could report but slight progress on road work there. By the end of October, funds allotted for the repair of the Burma Road east of the Mekong were exhausted. West of the river the Chinese did some work on bridges, but since they were still haunted by the spectre of a Japanese crossing of the Salween, it was impossible to get them to resurface the demolished portions of the road within thirty-five miles of the river. In December Stilwell proposed a further allotment of 480,000,000 Chinese dollars for widening, surfacing, and reducing grades, but the likelihood of getting the money appeared slight. Little work was accomplished. The Burma Road, Dawson disclosed late that month, was “still essentially a one-track road. ...” Nor could he report any real progress on the Mitu Road. Having appropriated 168,000,000 dollars in September for construction of the first

300 kilometers, the Chinese Government organized a makeshift Mitu Road Authority. Despite Dawson’s repeated protests, the Chinese ignored the graded and generally satisfactory roadbed of the Yunnan-Burma Railroad; they planned instead to turn a nearby supply trail into a one-lane, dry-weather road. This trail occasionally followed stream beds, which meant that monsoon rains would wash a road out altogether. In February the director of the road authority quit. His successor refused to take over because the agency’s funds were exhausted. By this time American hopes for the Mitu Road had been dashed to pieces by Chinese indifference and mismanagement.33

Supplies

Engineer supply for the theater was an immense problem by the latter months of 1943. In October General Somervell, on a worldwide inspection trip, visited Base Section 3. His observations and his talks with General Wheeler and Colonel Strong convinced him that Army Service Forces would have to intensify its efforts even more if Stilwell’s vital supply line across Burma was to be completed before the monsoon began in 1944- The engineers’ most common complaint about their equipment was that the D-4 tractors and ½-yard shovels were too small for the work the general service regiments had to do. On 21 October Somervell radioed Styer, directing him to procure and ship to the theater by January 1944 a large number of heavy construction items. Included were 100 D-7 tractors, 40 shovels, 70 scrapers, 75 graders, and 10 rock crushers. Somervell assured Wheeler that on his return to Washington he would institute changes in tables of equipment for general service regiments to provide machinery of greater earth-moving capacity. Noting that local sources of engineer material were almost exhausted, particularly in the categories of electrical and water distribution systems and builder’s hardware, Somervell directed his subordinates to begin shipment by January 1944 of a 6-month supply of such materials.34

In reviewing the troop situation with Somervell, Wheeler emphasized the fact that units from the United States were not reaching Base Section 3 on time. The causes were varied—insufficient shipping, the relatively low position of the engineers on the theater priority list, and the frequent unreadiness of units in the United States for overseas movement when they were scheduled to go. The troop basis for pipeline companies, which Somervell proposed to expand from ten to seventeen, was a case in point. Three companies were needed at once, but for the reasons given above none would be in the theater before January 1944.35 Commenting on the overall engineer troop situation in a radiogram to Styer on 22 October, Somervell stated that it was impossible “to overemphasize the importance of getting these units here at

the earliest ... date.” “Adequate shipping should be secured,” he directed. In addition Styer should insure “that these units are ready to meet new priorities ... and all delays due to defects in equipment, training, or other causes should be avoided at staging areas.” Also needed in order to “strengthen the general situation” were maintenance, heavy shop, depot, and parts supply companies.36 Stilwell’s staff agreed to improve the engineers’ position on the theater priority lists. The rest was up to Army Service Forces.37

Problems of Organization

The latter part of 1943 saw far-reaching changes in the assignments of key officers in the theater. Wheeler was transferred from the Services of Supply, CBI, to the Southeast Asia Command to become Mountbatten’s chief administrative and supply officer. Mountbatten’s engineer-in-chief was British Maj. Gen. Desmond Harrison; his deputy engineer-in-chief was Col. Walter K. Wilson, Jr., recently arrived from the United States along with Maj. Gen. Albert C. Wedemeyer, who had been selected as Mountbatten’s deputy chief of staff. As Wheeler’s successor in SOS, Stilwell accepted Somervell’s choice of Brig. Gen. William E. R. Covell, an Engineer officer, at that time head of the Fuels and Lubricants Division in the Office of The Quartermaster General. Colonel Farrell of ASF’s India Committee went to CBI as Engineer, SOS, to replace Colonel

Strong, who was to return to the United States. General Godfrey was scheduled to become Stratemeyer’s engineer, with Colonel Seeman as his deputy. More officers were now available. Between mid-November and mid-December about fifty arrived from the United States to staff the engineer structure in the theater.

At this time Chennault and Stratemeyer were making vigorous attempts to take airfield construction away from the Services of Supply. Seeking control of airfield construction in China, Chennault criticized, as contrary to established policy, the arrangement of having fields built under the direction of SOS. “If the present system were working well, it might be best to let it ride,” he declared on 9 October 1943, but, he stated, SOS engineers were in many instances unprepared to do the work which the Air Forces wanted. Moreover, he felt the presence of SOS in the chain of command merely served to extend the interval between the request for and the start of construction.38 Stratemeyer, hoping to get control over construction of the B-29 fields, had placed his aviation engineers on preliminary planning early in November. Wheeler pointed out that the proposals of the airmen, if carried out, would result in the formation of two competing engineer services. The Services of Supply was already critically short of engineers, and things would only be worse if the few that were available had to be shared.39 Upon taking up his duties as commander of SOS, General

Covell supported Wheeler’s views. He explained to Stilwell on 17 November that aviation engineering was “not unlike other construction.” Building up a separate engineer organization for the Air Forces would only delay getting MATTERHORN Off the ground. In his opinion, it would be “more expeditious to expand a going organization.”40 After weighing the arguments, Stilwell on 19 November transferred responsibility for building airfields in China and Burma to the Air Forces. He approved enlarging the Fourteenth Air Force Engineer Section and sending an Air Forces engineer headquarters company to China for service with Chennault. But he kept SOS in charge of airfield construction in India.41

One of General Covell’s first jobs was to deal with a request from Stilwell for a report on SOS and for proposals as to how that command might be reorganized in line with recent War Department plans for reorganizing communications zones in theaters of operations. These plans called for centralizing control of major technical activities in headquarters, SOS, rather than delegating control to the commanders of base and advance sections. In a report made on 2 December recommending strict adherence to the War Department’s plans, Covell suggested that command over construction projects “of a nature that involves highly technical control and operation” be placed directly under his headquarters. Insofar as engineer work was concerned, commanders of base and advance sections would henceforth be responsible only for administrative and housekeeping functions.42 Although Stilwell modified parts of Covell’s proposals, he approved fullest possible application of the principle of centralized command over engineer construction.43

On 22 December Covell established the Construction Service as one of his subordinate commands and made Colonel Farrell its head. At the same time, Farrell remained as Engineer, SOS.44 On 15 January Farrell took charge of all engineer work for which SOS was responsible except that in Pick’s Base Section 3 and in the advance sections in China. To staff his new headquarters, he merely made use of his SOS Engineer Section. Retaining its organizational structure substantially as it was, he took advantage of the recent influx of engineer officers from the United States to expand the various sections.45

By the end of January, Farrell, responsible for engineer work in a vast area, had set up a field organization modeled on what the Corps of Engineers had in the United States; that is, one made up of divisions and districts. There were two divisions and six districts. Division 1, under Col. Philip F. Kromer, included most of central and eastern India, except Assam. In this division, District i o, headed by Lt. Col. Kenneth E. Madsen, was in charge of the

work on the B-29 fields west of Calcutta, just getting under way. District 12, placed under Col. William C. Kinsolving, a petroleum engineer, formerly general manager of the Sun Pipeline Company and recently arrived from the United States, had the task of laying the two 6-inch pipelines from Calcutta to Assam. District 11 had charge of all remaining projects, located principally around Calcutta. Outside the divisional area and reporting directly to Colonel Farrell was District 9, which was responsible for construction in the New Delhi area. Pick was in charge of Division 2, which included most of Assam and part of Burma. He had two districts. District 20 was to do all construction and maintenance at the Hump airfields in Assam. District 22 was in charge of building the pipelines along the Ledo Road. Pick remained in command of Base Section 3, which included the Ledo Road. He retained firm control of all construction for which he had been responsible; work on the Ledo Road was not under Farrell’s jurisdiction.46

In view of the transfer of airfield construction in China from the Services of Supply to the Air Forces, Covell and Stratemeyer in December prepared a plan for reassigning engineer personnel on duty there. All engineer officers assigned to airfield work in Advance Sections 3 and 4 were transferred to the CBI Air Service Command. At the close of the month, the latter organized the 5308th Air Service Area Command, with headquarters at Kunming. The new organization was to direct all airfield construction in China. Colonel Byroade was transferred from Advance Section 4 and assigned temporarily to the area command as project engineer. In early 1944 the area command organized three districts. The first had charge of work on the eight fields near Kunming, the second was to build the 13-29 fields, and the third was to build more fields for Chennault in eastern China.47

The B-29 Fields

Late in 1943 work on the 13-29 fields began. The amount of construction required was considerable, for the size and weight of the B-29 were unprecedented. The craft’s wing span was 141 feet as compared to the 104 feet of the 13-17, or Flying Fortress, the next largest bomber; its loaded gross weight of approximately 70 tons was twice that of the Flying Fortress. Its wheel load was 34 tons as against the 19 tons of the B–17. According to estimates made in the United States, the B-29 required a runway 8,500 feet long and zoo feet wide, an area almost twice that of the 6,000 by 150 foot runway used by the B-17.

In India, the engineers set out to provide the runways for the 13-29’s by enlarging and improving five existing fields in the flatlands west of Calcutta. Little could be done unless help was forthcoming from the government of India. Much of the impetus for getting work started came from the engineers on Mountbatten’s staff. The SOS engineers appealed to General Harrison and

Colonel Wilson for help. They in turn appealed to Mountbatten, whose influence on the government of India was considerable, and help was promised. In mid-December, Stratemeyer’s engineers turned over to Covell the preliminary construction plans already prepared. Company A of the 653rd Topographic Battalion began to survey the fields in order to determine how the extensions could best be made. So that the runways could be made operational at an early date despite the shortages of men and materials, the SOS engineers persuaded the airmen to accept, for the time being, runways 7,500 feet long and 150 feet wide. Since the aviation engineers who were to build the fields would not reach India until February, the engineer-in-chief of the British Eastern Command agreed to furnish local contractors to begin work at the sites. In December, District 10 borrowed 170 equipment operators from various engineer units, together with 300 trucks. By the end of the month the district had provided each field with a project engineer to serve as a liaison officer with the Royal Engineers supervisor. In January Pick released the 382nd Construction Battalion temporarily to rush work on the field at Kharagpur.48 These various makeshift arrangements would have to do until the aviation engineers arrived.

By late 1943 work on the 13-29 fields in China was also under way. Byroade and his staff had begun planning during the last week of November. To find sites for the fields, Byroade personally reconnoitered the plains around Chengtu, 150 miles northwest of Chungking. He believed the area to be the best in Free China. The terrain was similar to that of the American midwest, and in the Chengtu Valley a number of fields already existed, the runways of which could be easily lengthened for the big bombers. After studying his report of 8 December,49 Chinese and American commanders worked out an agreement to get construction started. The Superfortresses would be based at four sites—Kwanghan, Pengshan, Kiunglai, and Hsinching. (Map 21) There were to be seven fighter fields. The Chinese Military Engineering Commission would control construction; American engineers would do mainly staff work. The responsibility of Lt. Col. Waldo I. Kenerson, head of District 2, would be limited to drafting specifications, preparing layouts, making inspections, and assisting with the organizing, administering, and paying the hundreds of thousands of peasants who would be conscripted for work on the airfields.50 Since the runways would have to be built largely by hand and probably could not be brought up to required standards, the full length of 8,500 feet was authorized

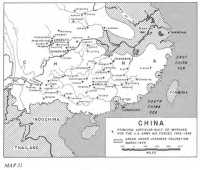

Map 21: Principal airfields built or improved for the U.S. Army Air Forces, 1942-1945

to lessen the chance of serious mishaps in takeoffs and landings.

Particularly irritating to the engineers was the radical departure from existing financial arrangements whereby the Chinese had paid for building operational facilities, and the Americans had supplied quarters, recreational facilities, and other nonoperational features. President Roosevelt had promised Chiang reimbursement for all labor and materials expended on MATTERHORN in China. How far Roosevelt had committed himself became evident in mid-December when the Chinese came up with a preliminary cost estimate of two to three billion Chinese dollars. “Appalling,” wrote Stilwell on 18 December, suspecting that “squeeze” accounted for a large share of this astronomical figure, which at the official rate of exchange amounted to $100-150 million in American money.51

By early 1944 the engineers were making progress in providing the logistic

Pipeline carried across a stream on an A-frame

basis for the impending Allied offensives. Of a total U.S. Army strength in Stilwell’s command of 100,000, tt,000 were engineers. Five thousand more were on the high seas, due to arrive within the next few months. The engineers were building or maintaining some forty-five airfields in India and twenty-five in China. Nearly 90 percent of the troops were working on the Ledo Road and the pipelines in Base Section 3. There were now about 80,000 tons of supplies and equipment in the hands of engineer troops in the theater, almost all of the tonnage being in Base Section 3. The condition of most of the equipment was poor. Nearly half of the machinery in Pick’s command was deadlined because of the lack of spare parts. Local sources of supply, almost depleted because of India’s low level of industrialization and the difficulty of maintaining imports

from the West, furnished no remedy to alleviate this situation. The engineers were becoming increasingly dependent on the United States for men and materials, and Army Service Forces was working against time to make good Somervell’s commitments to the theater.

The All-out Effort Continues

There was no slackening in the pace in the first months of 1944. With the Japanese brought to battle in northern Burma, work on the Ledo Road was of great importance. The engineers in western China continued urging upon the Chinese the necessity for early reconstruction of the Burma Road to support the Y-Force’s coming advance. At the same time engineer commanders were taking advantage of their growing resources in men and materiel to push the pipelines northward from Calcutta to Assam, and from there southeastward into Burma. To help prepare the great surprise which the B-29’s had in store for the Japanese, the engineers had ahead of them the enormous job of completing the bases in India and China for the Superfortresses. In addition, the demands of the struggle in northern Burma were to involve the engineers in combat for the first time.

Combat Support

After the Chinese won their victory over the Japanese at Yupbang Ga in the last week of December, Stilwell made plans to push the enemy farther southward. One of the prominent terrain features in northern Burma was the Tanai River, which flowed northwest

ward for about 50 miles through the Hukawng Valley to within ten miles of Shingbwiyang, where it made an abrupt turn to the south. The Tarung River, its source in the northern hills, flowed southward into the Tanai in the Hukawng Valley at a point about 18 miles southeast of Shingbwiyang. An oxcart trail led from Shingbwiyang eastward across the Tarung and then south across the Tanai to the village of Mogaung, 30 miles southwest of Myitkyina. This trail was the main supply route for the Japanese. Stilwell wanted to move a Chinese force across it some 30 miles southeast of Shingbwiyang in order to envelop the Japanese believed to be along the north bank of the Tanai east of the Tarung. While the main body of the division would assault the enemy frontally along the Tarung, a Chinese regimental combat team would slip across the Tanai south of Shingbwiyang and proceed along the river’s left bank. At the same time, a Chinese infantry regiment, assembled 25 miles southwest of Shingbwiyang, would move eastward into the upper Hukawng far behind the Japanese. If this plan of campaign could be carried out successfully, the Japanese would be trapped and destroyed in the Hukawng Valley. After that, the march on Myitkyina would be virtually unopposed.52

While the Chinese were preparing for the offensive, Stilwell detached two companies of the 330th Engineers to clear trails through the ten miles of jungle between Shingbwiyang and the Tarung so that the infantrymen could move forward more easily. This area was so near the enemy troops that patrols from both the 330th and the Chinese units had to be kept on both flanks. On 6 January a route to the Tarung was open to jeeps. The engineers then graded and widened a 12-mile-long, dry-weather road leading eastward from Shingbwiyang, to be used as a supply line for the Chinese.53

The attack was soon under way. On 13 January the Chinese crossed the Tarung and came to grips with the main body of the enemy. The regimental combat team which crossed the Tanai southeast of Shingbwiyang, hoping to envelop the enemy left flank, encountered unexpectedly strong resistance on the south bank. Although it managed to push the enemy eastward beyond the confluence of the Tanai and Tarung, it had to pause to root out pockets of resistance and consequently could not put any serious pressure on the main enemy force north of the Tanai. The envelopment of the Japanese flank failed. Elsewhere, the Chinese made reasonable progress. During the first’ week of February, they reached the village of Taihpa Ga located at the point where the oxcart trail crossed the Tanai, four miles east of the Tarung.54 The stubborn Japanese resistance halted progress on the Ledo Road. Pick had to keep almost all of his men north of Shingbwiyang, where they were engaged in grading and widening the stretch of road already put in.

Stilwell had decided that as soon as Taihpa Ga had been captured, he would

send Col. Rothwell H. Brown’s Chinese tank group down the oxcart trail toward Mogaung. He directed Pick to send in engineers to improve and hold open this “combat trail,” as it was henceforth usually called. This would mean a serious diversion of Pick’s engineers from the Ledo Road. The combat trail, lying dangerously below the flood levels of the Hukawng Valley, had already been rejected as a possible route for the road. A great deal of work would be needed to make it passable for military vehicles. Pick, bowing to tactical necessity, put a strong engineer force on the job of improving the trail and bridging the rivers. Men of the 1st Battalion, 330th Engineers, worked long and hard to make the trail passable for military vehicles. They were joined by the 76th Light Ponton Company and Company A of the 1883rd Aviation Battalion. Early in February a detail from the 330th built a dry-weather transport strip at Taihpa Ga, despite the frequent shelling from Japanese artillery south of the Tanai. In the first half of the month the 76th pontoniers put a 470-foot pneumatic ponton bridge across the Tarung. The overall situation was encouraging.55

During March Pick, now a brigadier general, had to lend a number of his engineers to the infantry to provide support for the forward movement. At the beginning of the month, at Taihpa Ga, the 71st and the 77th Light Ponton Companies built a 470-foot ponton bridge across the Tanai over which Brown’s Chinese tankers and infantrymen passed and then moved down the combat trail.56 Ten bulldozer operators from the 330th General Service Regiment volunteered to support Brown’s forces with their machines. On 3 March they went into action with the tankers at a point thirteen miles southeast of Taihpa Ga. The engineers’ mission was to hew a trail through the jungle to the southeast and help get the tanks across numerous streams so that they could make a surprise assault on the Japanese at the hamlet of Walawbum, twenty-two miles southeast of Taihpa Ga. Three of the engineers were wounded the first night. Three were subsequently awarded the Silver Star, and the entire group was commended, as Stilwell put it, “for resolute conduct under very difficult terrain conditions and while frequently in contact with enemy opposition.”57

As infantry and tanks closed in on Walawbum from the northwest, a new threat to the Japanese appeared from the east. The American infantrymen originally scheduled at QUADRANT to serve under Wingate were, upon arrival in the theater, diverted to Stilwell to be used as a hit-and-run force. Merrill, now a brigadier general, was in command. Correspondents dubbed the force “Merrill’s Marauders.” On their first mission, the Marauders suddenly appeared at Walawbum on 3 March and threatened the Japanese there with entrapment. The enemy commander on the same day ordered a general retreat to the south. By 9 March the Japanese were gone.58

Early in March Wingate was ready to

begin his airborne offensive. He had assembled Colonel Cochran’s Air Commando unit, 4 brigades of Chindits, and the 900th Engineer Airborne Aviation Company at 2 airfields, 300 miles northeast of Calcutta. The engineers were to prepare strips in the Burmese jungle for the Chindits to land on. Engineers in other theaters had already carried out airborne missions; this one would be the first mission in which they would travel to their destinations in gliders. Airmen, reconnoitering at low altitudes over the Burmese forests, had come upon two fairly level clearings near the western bank of the Irrawaddy, eighty miles south of Myitkyina. Engineers flown in with the first infantry detachments were to prepare the clearings for the large number of planes to come in later. Aerial photographs made shortly before the scheduled takeoff showed that trees had been dragged onto one of the clearings to block a landing. All the gliders would therefore have to be flown to the other clearing despite the congestion likely to ensue.

On the evening of 5 March men, planes, and gliders were ready to take off for their destination, 250 miles deep in enemy-held territory. Accompanying the infantry were Capt. Patrick J. Casey, commander of the 900th engineers, with 13 of his men. They had four bulldozers, two scrapers, a grader, a jeep, and hand tools. The men loaded the bulldozers, with blades attached, on the gliders. The air fleet took off, the planes towing the gliders in tandem. Crossing the 7,000-foot-high mountains of the Indo-Burmese border, the fleet soon approached the clearing. The heavily loaded gliders came down at high speed. Some of the first ones ran into unforeseen difficulties. The field was crisscrossed with ruts, which, overgrown with grass, had been invisible to the reconnoitering parties. The ruts tore off the landing gear of some of the craft and caused a number of crashes. With so many craft coming down at once, several pile-ups resulted. Some of the gliders rammed into the trees surrounding the clearing. The glider in which Captain Casey and an engineer enlisted man were riding came in too high. Attempting to circle the clearing for a landing, the pilot lost control of the craft; it plunged into a tree, and the occupants were killed. All told, about 5 percent of the landing force was lost. A bulldozer and a scraper were wrecked.

The first infantrymen to land dispersed to guard against possible enemy infiltration. The engineers began to prepare the landing strip. Their main job was to level the clearing as rapidly as possible with their machinery. Some of the infantry, using hand tools, filled in ruts and cut grass. The soil, with a high clay content, would be satisfactory for dry-weather operations. The next night, about seventy C-47’s safely brought in troops and supplies on a runway already provided with lights, radios, and radar. That same night another detachment of the 900th was flown to a glade fifty miles farther south. This landing was made without mishap. Using their bulldozers, the engineers smoothed the surface of the clearing sufficiently to enable transports to land without serious damage. Chindits, flown to these two fields, set out to dynamite the Burma Railway.59

Harassed from the front and rear, the Japanese in the Hukawng Valley withdrew southward, hoping to make a stand on a ridge at the southern end of the valley. On 19 March the Chinese upset these plans by seizing the ridge. They then pushed on, while the Marauders repeatedly hit at the enemy’s rear and flanks. In late March, with his forces only seventy-five miles from Myitkyina, Stilwell planned a bold stroke to seize the city and its important airstrip before the monsoon closed in. The Chinese were to continue the advance in such strength as to lead the Japanese commanders to believe that Mogaung, not Myitkyina, was their goal. While the Japanese moved troops from Myitkyina to defend Mogaung, two Chinese regiments and the Marauders would slip over the Kumon Range and descend on Myitkyina from the northwest.60

Meantime, the Japanese began an offensive of their own against the British Fourteenth Army near Imphal on the Indian-Burmese border. The British had been expecting an attack for months and had their plans ready for meeting it. At the first enemy attacks, they intended to retire from the mountainous frontier and draw the Japanese into the Manipur Plain. When the Japanese reached Imphal, British ground troops with the help of airborne reinforcements would turn on them. But the enemy struck with much greater speed and strength than expected, and the British position soon appeared to be precarious.61

The extent of the Japanese offensive suggested to Mountbatten the need for stronger measures against the enemy’s lines of communications. Additional airborne troops would have to be flown into Burma. To place his last two Chindit brigades across enemy lines of communications and to supply his more or less isolated units already in Burma, Wingate called upon the airborne engineers to prepare a landing strip in a clearing about eighty miles southwest of Mogaung. At dusk of 21 March a third detachment of the airborne engineers was flown to Burma. Construction of this landing field was a race against time. Wingate’s staff believed the Japanese, who would undoubtedly learn of the landing, would attack within twenty four hours. The engineers would have to prepare the strip so that the Chindits could land before the enemy arrived. The race was won by two hours; this was the length of time it took the first Chindits to make contact with the approaching Japanese. Personally directing this new assault, Wingate was killed in a plane crash on 24 March. He left to his successor, Maj. Gen. W. D. A. Lentaigne, the problem of coping with the desperate situation of those Chindits holding the railroad block at Mawlu against frantic Japanese attempts to break their grip.62

On the plains of Manipur, things continued to go badly for the British. By 30 March the Japanese vanguard had reached the highway leading north from Imphal to Dimapur, about 170 miles southwest of Ledo. The British Fourteenth Army,

70,000 strong, found itself cut off from contact with friendly forces. In an emergency meeting on 3 April at Jorhat with Mountbatten and his principal subordinates, Stilwell was relieved to discover that the British were confident of ultimate success because of the logistical overextension of the Japanese forces. In fact, for the first time, Stilwell’s British colleagues seemed really enthusiastic about his offensive against Myitkyina.63

Because of the desperate plight of the Chindits at Mawlu, Lentaigne sent the commandos and the engineers on a rescue mission. On 4 April the commandos landed five gliderloads of engineers with equipment in a clearing near the roadblock. The men prepared a landing strip at the foot of the high hill upon which the Chindit stronghold was located. Additional troops and supplies flown in enabled the Chindits to keep the Burma Railway blocked until the monsoon rains began one month later.64

Progress on the Ledo Road

During the first months of 1944 work on the Ledo Road lagged. Because of the unfavorable tactical situation east of the Tarung, nothing was done on the roadhead east of Shingbwiyang until 26 January. Between then and early February, the engineers cleared twelve miles beyond the city. Work stopped. The proximity of the Japanese and the diversion of troops to the combat trail made it advisable to halt. For the time being, the 45th and 330th General Service Regiments and four aviation battalions graded and graveled the road north of Shingbwiyang. The beginning of March saw the resumption of sustained work on the roadhead. The 1st Battalion of the 45th Engineers took the lead. Hardly had it finished its clearing and grading to the Tarung during the last week of March, when Stilwell directed it to move south of the Tanai to help maintain the combat trail. Moving up to the forefront on the Ledo Road, the 1883rd Aviation Battalion began pushing through the forests and marshes beyond the Tarung. The unit did both grading and graveling. In April, to speed the work, General Pick sent the 1905th Aviation Battalion and Company A of the 330th Engineers ahead of the 1883rd to put in a finished and separate four-mile stretch of road. At the same time, details of engineers built a number of landing strips along the road so that supplies could be flown in and defense of the road facilitated.65

It had been recognized from the first that one of the biggest jobs on the Ledo Road would be bridging the turbulent rivers of northern Burma. Materials had been requisitioned early and had begun to reach the theater in the first months of 1943. The engineers in the theater had decided that the H-20 bridge would be best. This bridge consisted of decking, supported by two trusses made up of rectangular, latticed steel sections, each 12½ feet long, 6 feet high, and 2 feet wide, weighing nearly a ton

apiece, and bolted together. The maximum span, made up of ten sections on a side, was 125 feet; it could carry loads up to 15 tons. With shorter spans and more than two parallel trusses, the capacity of the bridge could be increased to 54 tons. Early in March, General Pick placed the main responsibility for bridging on the 209th Combat Battalion. One company of the battalion, helped by the 76th Light Ponton Company, built an H-20 bridge, 960 feet long, over the Tarung in 27 days, completing it early in April. The other companies of the 209th bridged the lesser streams beyond the Tarung. In mid-March, Company A of the 209th started to build an H-20 over the Tawang. This bridge, together with its wooden trestles over the swampy approaches, was 1,200 feet long. The major accomplishment of Company F of the 330th Engineers during the dry season was the erection of a third H-20, 607 feet long, over the Tanai. This job was completed early in May.66

As a result of the QUADRANT Conference, bridging for the Ledo Road had become a major subject for planning in the Office of the Chief of Engineers and in Army Service Forces in the fall of 1943. During the following winter OCE sponsored various study projects in order to find the most suitable types of bridges for the major river crossings. Since the structures for the road would be built far behind the front lines, various types of military bridges and even commercial bridges could be considered. At this time a new type of structure, the Bailey bridge, was replacing the H-20.

Named after its British inventor, Sir Donald Coleman Bailey, it was based on an entirely different principle from that of the H-20. Its basic unit was a flat panel 10 feet long and 5 feet high, weighing about 600 pounds. The panels were connected by pins to form trusses, which were joined beneath by transoms to support the decking. Multiple trusses and multiple stories of panels made it possible to erect spans of 30 to 220 feet that could carry loads from 10 to 100 tons. The panels could also be used to build piers. One great advantage of the Bailey was its adaptability to various loads. Another type of bridge which might be used was the I-beam bridge, produced commercially, the decking of which rested on steel beams from 30 to 60 feet long.67 Confronted by a shortage of engineering data within and without the theater, the Chief’s Office sent a team of bridging specialists to CBI in January 1944 for firsthand consultations with engineers in the theater. As a result of investigations and discussions held at Ledo and New Delhi during February and March, the theater engineers chose the H-20 bridge as still the best for the Ledo Road. This decision created something of a stir in Washington, since the H-20’s during the past year had been replaced by Baileys in the Engineers’ catalog of standard equipment. Attempts by the Office of the Chief of Engineers to get Pick and Farrell to accept substitutes were to no avail. Bailey bridge panels would require more cargo space for a given bridge capacity than would the H-20, and I-beams were

too long for shipment on the diminutive cars of India’s railways. Faced with these irrefutable logistical arguments, OCE accepted the theater’s decision and reinstituted procurement of H-20 bridging in late April 1944.68

The longer the finished portion of the Ledo Road became, the greater was the effort needed to keep it open to traffic. Pick systematically turned over to various engineer battalions the responsibility of maintaining each new section of the road as soon as the forward troops finished compacting the final layer of gravel or crushed rock. On 29 April, he set up a road maintenance division under Lt. Col. Donald L. Jarrett, to direct the work of engineer troops who were to keep completed sections in repair.69 By mid-May, Jarrett had three aviation battalions working full time on maintaining the road between Ledo and Shingbwiyang. They built and repaired bridges, resurfaced poor sections, eliminated some of the worst curves, reduced grades, and installed better drainage. Since Jarrett’s organization was directly under Pick, Colonel Green as road engineer was able to concentrate his attention almost entirely on road construction.70

Progress on the Pipelines

During the first months of 1944 Colonel MacIsaac began to make more rapid progress on the pipelines. Late in January specially trained troops arrived from the United States and took over construction of the 4-inch line along the road. The 699th and 706th Petroleum Distribution Companies, joined by the 775th in February, strove to complete the line from Ledo to Shingbwiyang as soon as possible without getting in the way of the graveling crews. Having arrived without their equipment, the troops had to borrow hand tools, welding machines, bulldozers, and trucks from units at Ledo and on the road. They soon discovered what troops on the road had long known—that constant hauling and rough roads gave trucks a merciless beating and burdened drivers and mechanics with ceaseless maintenance chores. As if to climax their trials, the 699th engineers had hardly gotten pumping operations under way early in March when a 1 ,000-barrel tank of gasoline at Logai, fifty miles down the road from Ledo, burst into flames and had to be junked. Nevertheless, by mid-March the line was through to Shingbwiyang. Thereafter, MacIsaac moved the 706th and 775th forward as rapidly as the tactical situation permitted.71

Colonel Kinsolving, head of District 12, had hoped to begin construction in January on the first standard-weight 6-inch line, which would extend from Calcutta to the Assam Oil Company’s storage tanks at Tinsukia, 30 miles west of Ledo. The diversion of troops to build a 6-inch line to the MATTERHORN fields, and the delay in the arrival of salvaged standard-weight pipe from British depots in the Middle East forced Kinsolving to mark time until mid-February. Then,

with three petroleum distribution companies, the 709th, 776th and 777th, he began to build the line from the tanker terminal at Budge-Budge, south of Calcutta, up along the Bengal-Assam Railway toward Tinsukia—a distance of 750 miles. At Tinsukia the line would connect with the 4-inch invasion-weight line running along the Ledo Road. It must have seemed to Kinsolving that many factors were in conspiracy against his plans to complete the project by August. When the pipe began to come in, it was frequently in damaged condition and without couplings and screws. Farrell and Kinsolving decided in late February to build the line with invasion-weight pipe, newly arrived from the United States and intended only for the northern reaches of the line. This decision produced complications, for in the densely populated lower Brahmaputra Valley it was necessary to bury this thin pipe, which was highly subject to corrosion and leakage. Stilwell’s drive in Burma and the Japanese invasion of Manipur Province placed such a strain on the Bengal-Assam Railway that the tonnage allotted to District 12 had to be cut by nearly 75 percent in March. There were bright spots, however. The railway officials and crews proved highly cooperative in hauling and unloading pipe along the right-of-way, and the British garrison engineers at various posts along the route did effective work in securing land and rounding up local workmen.72

Progress on the B-29 Fields

Meanwhile, the engineers were rushing work on the MATTERHORN fields. In West Bengal, Colonel Madsen, head of District 10, had the 879th Airborne Aviation Battalion, the 382nd Construction Battalion, and the 853rd, 1875th, and 1877th Aviation Battalions. These units began work on the five B-29 fields in March with borrowed equipment, pending the arrival of their machinery. In mid-April, with the arrival of the 1888th Aviation Battalion, Madsen had 5,000 engineers on the job. By the end of the month Kinsolving announced substantial completion of a 6-inch pipeline from the tanker terminal at Budge-Budge to the fuel distribution systems at the airfields. With the arrival of the aviation battalions’ machinery in April more rapid progress was possible on the runways. A major task was to make the best use of the local workmen, who were not too efficient at best. It was soon obvious that native customs would have to be observed, if the construction was to go on smoothly. At Chakulia, the 1877th engineers, unaware that the Bengalese regarded the quarrying of rock as man’s work and the screening of it as woman’s, bulldozed stockpiles for both sexes to screen. Everyone walked off the job. Religious considerations obliged the engineers in District 10 to stock seven types of rations. Work moved ahead, but slowly.73

In China, progress on the B-29 fields was encouraging. Each field was to consist of a runway, taxiways, hardstands, a fuel distribution system, revetments, and housing for service crews. Since it was impracticable to transport either cement and concrete mixers or asphalt from India, runways would have to be built of rock, gravel, and sand. Limited in theory to staff and liaison functions, Colonel Kenerson, as District 2 engineer at Chengtu, had to assume numerous responsibilities which the Military Engineering Commission was charged with but could not perform adequately. Kenerson had to supervise much of the administrative work required in hiring and utilizing the 365,000 peasants conscripted by the Governor of Szechwan. Despite centuries of experience in building hard-surfaced roads by hand, the Chinese were largely unprepared to construct the 8,500-foot runways capable of sustaining the 70-ton bomber. Kenerson found he had to teach them the elements of soil mechanics; then he had to supervise them constantly to see that they applied what he had taught them. As a rule, the peasants toiled dutifully, but there were some serious riots caused by disgruntled workers whose only desire was to go home.74

In late February there was a noticeable slowdown, partly as a result of the failure of the Chinese to find enough trucks for hauling material and partly because of

the breakdown in the government’s system for distributing funds. Brig. Gen. Thomas F. Farrell, supporting Kenerson’s efforts insofar as possible, sent several small rock-crushers by air and supplied a detachment of engineers to install gasoline distribution systems at the bomber fields. By the time construction had started in January, Chinese estimates of the cost of the fields had risen to a fantastic five billion dollars. “Squeeze” in the Chengtu area would inflate even that figure. By late spring cost estimates were to reach seven billion dollars. At the official rate of exchange, the United States would have to pay $350,000,000 for the fields at Chengtu.75

Airfields for Chennault

Work was continuing on the fields in eastern China for the Fourteenth Air Force. Since the fall of 1943 Chennault had been trying to enlarge his engineer staff of four men to make possible more effective supervision of the work. Shortly after the 5308th Air Service Area Command activated its Engineer Division under Byroade at Kunming on 1 February 1944, Chennault conceived the idea of merging Byroade’s office with the Engineer Section of the Fourteenth Air Force. On 16 March Byroade assumed the dual role of Engineer, Fourteenth Air Force, and Engineer, 5308th Air Service Area Command. He merged his two offices within the month. On 18 March, Stilwell gave Chennault control of all construction for air force elements in China, a control Chennault delegated

to Byroade.76 The air force engineers had their work cut out for them.

District 3 in eastern China inherited all the harassments and irritations Advance Section 4 of SOS had experienced with Chinese officials and contractors. The lieutenant-governor in South Kiangsi, who had tied up construction at Kanchow and Sincheng during the winter because of a dispute over the certification of contractors, finally had the situation sufficiently under control to permit construction to start early in March. “He has merged all the contractors in the area into a company of his own,” one engineer wrote to Byroade, “and has jacked prices for earthwork, paving, etc., up 200% at Sincheng and 100% at Kanchow.”77 Merchants supplying materials for American projects, informed that local officials expected generous kickbacks on each sale, adjusted prices accordingly. In many instances work was held up, specifications were flouted, and schedules disrupted by the paramount importance of “face.” The engineers learned that the Chinese could easily lose face if they took orders from foreigners, admitted their ignorance, or dealt with officials of lesser rank. In China, ways and means had to be found to remove even the most minor incompetent officials without affronting their dignity. But progress was made on the airfields. By t April 1944 Engineer District 3 was maintaining eight major fields in eastern China, and construction was well under way on eight more.78

Even at this late date work on the Hump airfields was continuing in Assam to enable them to handle bigger loads for Chennault. As head of District 20, Lt. Col. Karl M. Pattee had a staff of twenty officers and the 848th Aviation Battalion at his disposal. Most construction and maintenance continued to be a responsibility of the Royal Engineers. But Pattee was able through his control of his aviation battalion to exercise a more than nominal control over the course of airfield work in Assam. As before, airfield construction conformed to British specifications at all of the eight airfields regularly used by the Air Transport Command in Assam. By the spring of 1944 the airlift was beginning to realize its potentialities.79

While the Fourteenth Air Force was unable during the first quarter of 1944 to carry out all of Chennault’s claims, the successes that it did achieve were such that the Japanese high command was compelled to act in the spring. Shipping on the Yangtze River had become so unsafe that the enemy determined to reopen the Peiping-Hankow railway as an alternate supply line. Because of Chennault’s crippling attacks on the sea-lanes linking Japan to her southern conquests, the high command ordered its mainland armies to overrun Chennault’s eastern airfields and open railroad communications from the Yangtze Valley to Canton and French

Indochina. The first phase of this operation, starting in April, was to be the conquest of a large pocket north of Hankow. In May the Japanese began to move south from their base at Hankow to drive the Fourteenth Air Force off its advanced bases around Kweilin.80

The Theater Engineer

Colonel Newcomer, Stilwell’s engineer, was little concerned with all this activity in China. Although his responsibilities were theater-wide, Newcomer never looked upon his office as playing “a critical role.” His staff at peak strength included one officer, Lt. Col. Robert F. Seedlock, and three enlisted men. Stilwell rarely consulted Newcomer. His principal job remained that of coordinating with the Chinese on airfield construction for Chennault and MATTERHORN and supplying Chinese troops to be sent to Burma. His office continued to take responsibility for supervising housekeeping duties for the American forces in Chungking. To do such administrative work as was needed for the engineer units in India, Newcomer had set up a small rear echelon office in New Delhi.

Early in May, General O’Connor, formerly head of the Northwest Service Command, arrived in India to replace Newcomer, who was transferred to Panama. Newcomer later stated that he was never so happy as when he received his orders for his new assignment. General O’Connor set up his theater engineer office in New Delhi and maintained a forward echelon in Chungking under Colonel Seedlock. The office of theater engineer assumed no more importance under O’Connor than it had under Newcomer.81

Overall Progress in Burma During the Early Monsoon

Work on the Ledo Road continued well into May. The 45th Engineers, taking over the lead on the road on the 15th of that month at Mile 168, began clearing and grading. But it was soon evident that the 1944 monsoon would be the equal of its predecessor. “The rain never stopped,” recorded the regimental historian.82 Progress through the mud slowed to a crawl. Toward the end of the month, General Pick came to definite conclusions about the immediate future. Mindful of the loss of engineer troops to the fighting front and the increasing maintenance efforts required by the rains, Pick decided that for the time being his engineers could do little more insofar as road construction was concerned. Having advanced about 70 miles during the past four months, the road was open to trucks as far as the Tanai, 145 miles from Ledo. The roadhead had reached a point 30 miles beyond the river. “I do not wish to give you the impression,” Pick wrote to General Covell on 25 May, “that we are folding up.” He went on to say:–

But I thought you would like to know

what the conditions are. ... Our equipment to a very great extent is just about shot. Our troop strength has been reduced to such an extent that we can not be expected to go any further [than] Warazup during this season... But unless I can get troops and equipment, I don’t think we can advance any farther and maintain the soft, spongy, newly completed road. …83

It was hardly likely that the Ledo Road would be extended much further during the monsoon.

The campaign in northern Burma was so far behind schedule that it was questionable whether the road could have been pushed through to Myitkyina before the monsoon rains in any case. To make matters worse, the Chinese had persistently hung back from launching the Y-Force across the Salween. These unfavorable developments, together with the British reverses on the Manipur Plain, had gradually forced Stilwell to give up hope of extending the road into Myitkyina during May. But since late March he had been making plans for taking Myitkyina by an air attack before the monsoon set in. Capture of the town would be desirable for many reasons. It would have beneficial effects for the airlift to China. Seizure of the airfield would drastically curtail the enemy’s power to interfere with the airlift and would at the same time permit the Air Transport Command to use a lower and more southerly route across the mountains to Kunming. Besides, the extension of the two 4-inch pipelines to Myitkyina, which could probably be achieved before the Ledo Road was completed that far, would enable transports to refuel there and thus conserve valuable cargo space for supplies for China.84