Chapter 8: From the Garigliano to the Arno

Preparations for the Offensive

The Strategic Concept

After the failure to crack the Gustav Line in mid-March 1944, General Alexander revised his strategy for the whole campaign. Plans for the spring offensive contemplated combining another and still heavier frontal assault with a double flanking movement from the left. II Corps was to move up the coast, along the axis of Highway 7, while the French Expeditionary Corps predominantly skilled in mountain fighting, was to attack through the lightly held ridges that formed the southern wall of the Liri Valley. Simultaneously, the British Eighth Army was to renew the assault on Cassino, while VI Corps, at Anzio, was to be ready at the strategic moment to cut Highway 6 at Valmontone. If the movement succeeded, an entire German army would be trapped and destroyed.1

The plan of attack called for a high degree of coordination and involved logistical problems of great difficulty, especially in the sector assigned to the French. It was necessary, moreover, to regroup the Allied forces all along the line before the offensive could be mounted, and to do it without giving the enemy any hint of the nature of the forthcoming operation.

Under orders issued on 5 March, the British 10 Corps in the Minturno sector was quietly relieved by the U.S. 88th Infantry Division, newly arrived from Africa where it had completed its training. The British 5th Division from 10 Corps and the U.S. 34th Division from II Corps went to Anzio in March, while the 36th went into training for a later role with the beachhead forces or for new action on the southern front. The French Expeditionary Corps, reinforced by the arrival of the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division, sideslipped to positions on the right of the 88th, while Eighth Army, leaving only one corps of two divisions to hold the Adriatic front, took over the Cassino sector. Moving in small groups at night to camouflaged positions, the reshuffling was not complete until April.

By that time the 85th Infantry Division, fresh from the United States, had joined the 88th on the lower Garigliano. These new American divisions were accompanied by their organic medical battalions, the 310th with the 85th Division and the 313th with the 88th. Both divisions were attached to II Corps, which had been weakened by loss of the 34th and 36th. When the British 56th

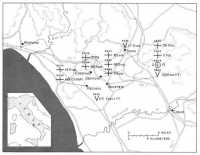

Map 25—Fifth Army Hospitals and Medical Supply Dumps on the Cassino Front, 11 May 1944

Division returned from Anzio it was assigned to Eighth Army. The remaining 10 Corps division, the 46th, was sent to the Middle East, but returned to Italy later in the year as an Eighth Army unit.

Regrouping of Medical Installations

The realignment of the Allied Armies in Italy, as the former 15th Army Group was now called, made Highway 6 the main artery of support for Eighth Army, while II Corps was served by Highway 7 along the coast. U.S. medical installations were accordingly moved to positions in the new Fifth Army area as rapidly as they could be cleared, with due regard to deception of the enemy in the process. (Map 25) Patients were evacuated to base hospitals in the Caserta area, the Naples hospitals being largely reserved for Anzio casualties and those from the French Expeditionary Corps.2

In the new sector, all Fifth Army hospitals were grouped in the vicinity of Carinola, adjacent both to Highway 7 and to the railroad that roughly paralleled that highway all the way to Rome. The area was about 12 miles east of the mouth of the Garigliano and no more than 10 or 15 miles southwest of the Teano-Riardo area from which most of the installations came. The 11th Evacuation Hospital opened at the new site on 11 March, followed two days later by the 95th. The 8th Evacuation Hospital and the neuropsychiatric hospital operated by the 601st Clearing Company were ready to receive patients in the Carinola area on 23 March, and the 38th Evacuation completed its move on the 29th. The 10th Field Hospital, the 16th Evacuation, and the 3rd Convalescent opened in the Carinola area on the 3rd, 16th, and 26th of April, respectively.

The 38th Evacuation had changed places with the 56th from Anzio, and the 11th had rotated with the 93rd before all these moves were completed. The 94th Evacuation Hospital went direct to Anzio from its Mignano site late in March. The venereal disease hospital operated by the 602nd Clearing Company closed at Riardo on 27 March and went into bivouac. Its place was taken by a temporary venereal disease hospital set up under II Corps control by the clearing company of the 54th Medical Battalion. The hospitalization units of the 11th Field Hospital were brought together late in February, operating under canvas as a provisional 400-bed station hospital for troops in training until early April. The 11th Field then went into direct support of the clearing stations of the 310th and 313th Medical Battalions.

Veterinary units serving Fifth Army were also moved during March in the same general pattern. The two Italian-staffed veterinary hospitals were established in the II Corps area, the 110th on the extreme left and the 130th at Nocelleto close to the main concentration of medical units. The first U.S. veterinary installation to reach the theater, the 17th Veterinary Evacuation Hospital, arrived during the regrouping and was established near Teano, on the extreme right of Fifth Army.

For some six weeks before the launching of the drive on Rome, set for 11 May 1944, Fifth Army medical units on the southern front had only routine functions to perform. Hospitals brought their equipment up to standard and replaced losses, while combat medical personnel trained with their divisions. Emphasis was placed on physical conditioning and on evacuation in mountainous terrain, but opportunities for recreation were provided.3

Combat Medical Service

The Drive to Rome

The Southern Front

An hour before midnight, 11 May 1944, Allied guns pounded German positions from the Tyrrhenian Sea to Cassino and beyond. Immediately thereafter the 85th and 88th Divisions of II Corps, and the French Expeditionary Corps on their right, attacked through the mountains north and west of Minturno. In the center of the front, the British 13 Corps of Eighth Army forced a crossing of the Rapido where the 36th Division had

suffered disaster in January; on the right the Polish Corps stormed Cassino and Monastery Hill. Though taken by surprise, the Germans rallied quickly to fight back with their customary stubbornness and skill; but this time the Allies were not to be stopped, and the monastery was taken on the 18th.4

While the Germans were still off balance from the punishing blows of Allied artillery, the French corps stormed the heights where the British had failed in January and within twenty-four hours had broken through the Gustav Line. Against stiffening but disorganized opposition, Algerian and Moroccan mountain troops then followed the ridges that overlooked the Liri Valley from the south, and by 19 May had outflanked the Montedoro anchor point of the still unfinished Hitler line, last of the German fortified positions on the southern front.

Between the French colonials and the sea, the 88th and 85th Divisions of II Corps also penetrated the mountains and, in a series of bitterly contested small unit actions, broke through the enemy’s prepared defenses. On 19 May the important highway junction of Itri fell to II Corps. Fondi was taken the next day, and the corps turned southwest toward Terracina, from which Highway 7 ran straight across the Pontine Marshes to Cisterna, the Alban Hills, and Rome.

On the Eighth Army front, where the strongest German defenses were concentrated, the advance was slower and more difficult, but the threat posed by Fifth Army on the left flank relieved enough of the pressure along Highway 6 to keep Eighth Army moving through the Liri Valley proper and on into the Sacco Valley beyond.

While II Corps drove through another mountain mass toward Terracina and the FEC stormed Pico, an important road junction which the enemy could not afford to lose, VI Corps at Anzio struck on 23 May toward Valmontone, where Highway 6 could be cut, the Sacco Valley blocked, and the whole German Tenth Army trapped.

In the rugged, mountainous area south of the Liri and Sacco Rivers, medical support was difficult in the extreme. Medical supplies and equipment were carried forward by jeep, by mule, by band carry, and in a few instances were dropped by parachute from small planes. Jeeps and mules were also used to evacuate the wounded, supplementing the inadequate number of ambulances and trucks whose usefulness was restricted by the severe limitations of the road network. In some instances it was found advantageous to hold casualties at the

Treating 88th division casualty at a forward aid station, May 1944

aid stations until the advancing troops had secured neighboring roads in order to avoid the long and difficult litter hauls.

As in the mountain fighting before Cassino, the heaviest burden fell on the litter bearers. The medical battalions organic to the 85th and 88th Divisions—the 310th and 313th, respectively—had each received its authorized overstrength of 100 litter bearers5 before the drive began, but the number available was still far short of needs, and both II Corps divisions drew heavily upon service and headquarters troops for additional bearers. Italian troops were also attached as litter bearers. All together the 85th Division had 700 litter bearers above the normal Table of Organization allotment, and the 88th had almost as many.

The 85th Division, on the left flank of II Corps, left its clearing station and the 1st platoon of the 11th Field Hospital in the vicinity of Cellole some five miles southeast of the Garigliano crossing. Casualties began coming back about an hour after the division went into action, and reached a record 544 during the 24 hours of 12 May. On the second day of the drive, with admissions to the clearing station again exceeding 500, the 3rd Platoon of the 11th Field Hospital joined the 1st in support of the 85th Division. Collecting companies operated in two sections in order to give closer support to the combat forces. All ambulances organic to the division were in use forward of the clearing station, together with additional ambulances borrowed from corps. Jeeps fitted with litter racks were invaluable. Through 14 May weapons carriers and trucks were used to bring out the walking wounded. Evacuation from the clearing station and field hospital was by two platoons of the 54th Medical Battalion.

The offensive was in its sixth day before the 85th Division had moved far enough forward to permit the clearing station to advance, but thereafter for the next ten days its moves were frequent. On 17 May the station crossed the Garigliano River to the vicinity of Minturno, leaving one platoon of the field hospital at the old site to care for patients not yet in condition to be evacuated. The other field hospital platoon similarly remained at Minturno, while the clearing station moved forward to Formia on 20 May and to a site near Itri on the 21st. On 24 May the clearing station was established five miles west of Fondi, with both field hospital platoons adjacent. Two days later the clearing

Italian civilians help carry a casualty down a mountain near Terracina

station again advanced without its field hospital support, this time to Sonnino, where it operated until the division was withdrawn from the line on 27 May.

The 88th Division, on the right of the 85th with the French Expeditionary Corps on its own right, followed a line of advance parallel to that of the 85th but somewhat farther to the north. Highway 7 was the initial axis of both divisions, and was consequently the line along which medical installations of both tended to be located. The starting site of the 88th Division clearing station was in the vicinity of Fasani, just north of the highway and some three or four miles east of the Garigliano.

Although casualties were not as heavy as those of the 85th, 369 passed through the clearing station of the 88th Division on 12 May. The station had crossed the river to a site a mile southeast of Minturno before it was given field hospital support on 16 May. At that time the 2nd Platoon of the 11th Field Hospital moved into the area. Evacuation from the clearing station was by an ambulance platoon of the 54th Medical Battalion.

Once the Gustav Line was broken, the

campaign moved more rapidly. The 88th Division clearing station shifted to Formia on the Gulf of Gaeta on 20 May and the next day to a site just west of Itri. In each move the field hospital platoon lagged behind for a day or two until its nontransportable patients could be transferred to one of the evacuation hospitals behind the lines.

At this point the 88th Division moved into the mountains north of Highway 7, and evacuation became increasingly difficult. Collecting companies were split to establish treatment stations along litter trails, and Italian troops were attached as litter bearers. Two collecting stations were in the vicinity of Fondi when that town was bombed the night of 23-24 May and suffered considerable damage to their vehicles.

Over the next three days, the division cut across roadless mountains to Priverno. In this drive litter carries were up to twelve miles from the moving front back to Fondi, with as many as fourteen relay posts along a single trail.

It was the last important action on the southern front. Once II Corps was in contact with the Anzio forces, German resistance south of the Liri and Sacco Valleys collapsed. On the 88th Division front, the entire 313th Medical Battalion moved to the vicinity of Sonnino on 25 May, and two days later the clearing station, with its attached field hospital unit, was set up just outside Priverno.

The French Expeditionary Corps, on the II Corps right, had the most difficult mission of any Fifth Army formation in the drive to Rome and suffered casualties commensurate with its success. The French medical units supporting the corps, though adequate for normal operations, were unable to carry the exceptional load required, and on 23 May the 403rd Medical Collecting Company, 161st Medical Battalion, with elements of the 551st Ambulance Company attached, was sent to reinforce the FEC. The next day the 406th Medical Collecting Company, 162nd Medical Battalion, was given the mission of evacuating French forward hospitals.

The Anzio Front

TheGermans were retreating hastily from Terracina when VI Corps, now more than seven divisions strong, began its drive on 23 May from Anzio beachhead. The 1st Armored, the 3rd Division, and the 1st Special Service Force led off, passing through the 34th to take the Germans by surprise. The attacking forces quickly penetrated enemy positions before the Germans could regroup. The 45th struck for limited objectives on the left of the salient, while the British 1st and 5th Divisions held defensively from the Albano road west to the sea, and the U.S. 36th remained in reserve.6

In two days of violent action, the 3rd Division once more proved its right to the name the Germans gave it of Sturmdivision. The 7th Infantry took Cisterna, fighting from house to battered house. The 15th and 30th regiments bypassed the town on either side and converged on Con, six miles nearer to Highway 6. In the same two days the Special Service Force seized the dominating height of Mt. Arrestino, southeast of Con, and columns of the 1st Armored were threatening Velletri, key to the Alban Hills and center of German resistance, from south and east. Contact had been made with II Corps patrols on Highway 7; the Twelfth Air Force, in close support, had destroyed hundreds of German vehicles on the crowded escape roads from the beachhead; and VI Corps had taken more than 2,600 prisoners.

On 26 May a sudden change of direction again caught the Germans unprepared. The 34th and 45th Divisions lunged west toward Campoleone Station and Lanuvio, while the 3rd held its gains. The 1st Armored, after a final thrust toward Velletri in terrain too rough for tanks, was relieved by the 36th. The 1st Armored was back in the line in the Campoleone sector on 29 May, but the Germans, holding fanatically along the Albano-LanuvioVelletri railroad, gave ground only by inches.

Meanwhile, the U.S. IV Corps headquarters under Maj. Gen. Willis D. Crittenberger had relieved II Corps headquarters on the southern front on 28 May, and II Corps had shifted to the beachhead, where General Keyes took command of the Valmontone sector. The 3rd Division and the Special Service Force passed to II Corps command at this time. The 85th Division, coming up from Terracina to reinforce the 3rd, went into the line the evening of 30 May, and the 88th Division was on the way.

The final drive to Rome was launched on 1 June, when Valmontone fell to the 3rd Division and Highway 6 was finally cut. The bulk of the German forces, however, had escaped from the Sacco Valley before the trap could be sprung, leaving II Corps to pursue a beaten but still dangerous enemy. At the same time elements of the 36th Division, on a mission in the rough and wooded area north of Velletri, penetrated the eastern slopes of the Alban Hills without encountering any resistance. Seizing the opportunity, the division shifted its ground and by evening of 1 June held commanding positions on the heights above Velletri that made the German position in the town no longer tenable.

Indeed, the Germans were already withdrawing, and only mopping up remained. Small, highly mobile units from II Corps on Highway 6 and from VI Corps on Highway 7, swept into Rome on 4 June, so close behind the retreating enemy that he had no time to destroy the bridges across the Tiber. Highway 6 had not been cut quickly enough to prevent the escape of the bulk of the German forces, but enemy losses in both men and material had been heavy.

The character of medical support on the Anzio front differed markedly from that dictated by the mountainous terrain west of the Garigliano. During the first few days of the VI Corps offensive, clearing companies remained in the hospital area east of Nettuno. The 3rd Division clearing station, supporting both its own division and the Special Service Force,

Half-track ambulance in the breakout from Anzio

was the first to move, setting up south of Con on 26 May along with a platoon of the 33rd Field Hospital.

One platoon of the 36th Division clearing company went into action with the division on 26 May, north of Cisterna, but did not have a platoon of the 33rd Field Hospital adjacent until the 28th. Both clearing station and field hospital moved to the Velletri area on 3 June. The field hospital platoon supporting the 3rd Division moved over to support the clearing station of the 45th after II Corps took command of the Valmontone sector. The remaining unit of the 33rd Field Hospital was established near the 34th Division clearing station south of Velletri by 30 May.

In the new II Corps sector, the 10th Field Hospital relieved the 11th on 29 May, units of the 10th Field being attached to the clearing stations of the 3rd, 85th, and 88th Divisions. The unit attached to the 3rd Division was forced to withdraw from its initial site south of Valmontone by enemy shelling on 29 May. The clearing station of the 88th Division in the same general area was

A newly taken German prisoner helps give first aid to a 3rd division casualty in the Cisterna area

bombed on the night of 1-2 June. A direct hit on the admissions tent killed nine persons, seven of them personnel of the 313th Medical Battalion. For the next twenty-four hours 88th Division casualties were taken to the 85th Division clearing station west of Valmontone on the rim of the Alban Hills.

By this time the combat troops were moving rapidly, and evacuation routes between collecting and clearing stations were lengthening. This was especially true of the 1st Armored Division, where treatment stations set up 2 of 3 miles to the rear might be 10 miles behind in a few hours. Both the 52nd Medical Battalion, supporting VI Corps, and the 54th Medical Battalion, supporting II Corps, were called upon to reinforce the division collecting companies in the final drive to Rome. On the II Corps front, along Highway 6, clearing stations moved almost daily.

Litter carries in the same period were long, as the troops outran their medical support. The indispensable jeep, fitted with litter racks, was used in many places inaccessible to ambulances, but even

jeeps were useless in much of the hill country on the 36th Division front.

Casualties were heaviest in the first two days of the drive out of the beachhead and on 1 June, when the Germans made their final effort to hold open their line of retreat along Highway 6. Field hospital units often operated beyond normal capacity and were frequently unable to evacuate their patients in time to move with the division clearing stations. Holding sections were usually left behind on these occasions, permitting the main body of the unit to advance. In other instances, it was necessary for one field hospital unit to support two divisions. Additional nurses for the field hospitals were supplied by Fifth Army, while other personnel and extra equipment were borrowed from nonoperational units. On 2 June the 1st Platoon of the 11th Field Hospital was attached to the 10th Field in the II Corps sector to help carry the load.

Pursuit to the Arno

After the fall of Rome, the German armies in Italy might have been destroyed had Alexander been allowed to retain adequate forces. The Combined Chiefs of Staff, however, gave higher priority to the expanding operations in France. During June and July General Clark reluctantly gave up both VI Corps and the French Expeditionary Corps. to Seventh Army for the invasion of southern France. The equivalent of more than eight veteran divisions, with supporting units, were withdrawn while Fifth Army was in pursuit of a badly beaten foe. In addition to the medical units organic to these divisions, Fifth Army also lost the 52nd and 56th Medical Battalions, the 10th and 11th Field Hospitals, and the 11th, 93rd, and 95th Evacuation Hospitals. At the same time the 750-bed 9th and 59th Evacuation Hospitals were withdrawn from the Peninsular Base Section.7

The combat-hardened units of the VI Corps and the FEC were gone, and in their place were the untested 91st and 92nd Divisions and the Brazilian Expeditionary Force of somewhat more than division strength. Of these only the 91st saw action before the Arno River line was reached. In effective strength, Fifth Army numbered 379,588 on 4 June, when Rome was taken, and only 171,026 on 15 August when the lines were stabilized.

After the fall of Rome the Germans fought only small rear-guard actions, trading ground for time to regroup and reequip their disorganized and decimated forces. Bridges, culverts, port facilities were methodically destroyed

Wheeled litter in the flat beachhead area

wherever their destruction would impede the Allied advance or delay the delivery of supplies. Battles were fought on terrain of the enemy’s choosing by mobile units that could disengage at will and outrun the slower Allied formations. Fifth Army, forced like the Germans to reorganize on the march, never quite caught up with any substantial body of enemy troops.

The pursuit opened on 6 June, the day Allied forces crossed the English Channel and secured the first beachhead on French soil. VI Corps, in the coastal sector, drove out along Highway 1 toward Civitavecchia, the largest port between Naples and Leghorn and urgently needed to shorten supply lines. The 1st Armored led the advance in two columns, the 34th and 36th Divisions following as closely as their transportation permitted. Elements of the 34th passed through the armor that night and took the city after only a token fire fight on the morning of 7 June. Within a week the port had been restored sufficiently to dock Liberty ships.

Some twenty miles inland, II Corps, with the 85th and 88th Divisions, struck along Highway 2 toward Viterbo with its important complex of airfields. The

Giving plasma to a 1st Special Service Force soldier while he is being evacuated by jeep to a collecting station

infantry was outdistanced by a task force of the 1st Armored that swung inland after the capture of Civitavecchia and secured Viterbo the morning of 9 June. By this time the pattern of the campaign was well defined. The hit-and-run tactics of the German retreat did not call for pursuit in force, permitting both the reduction and the reoganization of Fifth Army to be carried out in orderly fashion without loss of momentum. The 3rd Division, which garrisoned Rome until 14 June, did not go back into the line, and the 45th, in VI Corps reserve, was withdrawn on 8 June. The French Expeditionary Corps, which had been pinched out in the final days of the drive to Rome, began relief of II Corps along the Highway 2 axis on 9 June, and both the 85th and 88th Divisions were withdrawn for needed rest. At the same time the VI Corps sector was narrowed and left in sole command of the 36th Division, with the 361st RCT of the 91st Division attached, while the 34th and 1st Armored rested. On 11 June General Crittenberger’s IV Corps relieved VI Corps.

The reinforced 36th Division seized the town of Grosseto on 15June, and

crossed the Ombrone River that night. Two days later the 517th Parachute Combat Team, in Italy to gain experience for a mission in southern France, was also attached to the 36th. The advance, however, was slowing down in the face of stiffening opposition and more difficult terrain. In the French sector, the fighting centered around Lake Trasimeno was becoming particularly bitter.

To relieve the French and prepare for the first withdrawals from the FEC, the IV Corps sector was widened, and the 1st Armored returned to the line on 21 June. Five days later the 34th Division, with the 442nd Infantry attached, relieved the 36th, which went at once to the Seventh Army staging area. The 361st Infantry remained in the line, attached to the 1st Armored, but the 517th was withdrawn on the 28th.

The 34th Division took command of the coastal sector just north of Piombino, the small but immensely useful port that had fallen on 25 June. The division closed rapidly toward Highway 68, a lateral road that runs roughly east from a point on Highway some twenty miles south of Leghorn to a junction with Highway 2 at Poggibonsi, a similar distance south of Florence. The Germans fought hard at Cecina just below the junction of Highways 1 and 68, in an effort to delay the capture of Leghorn as long as possible, but the 34th was beyond the intersection by 2 July. The next day the 363rd Infantry of the 91st Division was attached to the 34th, in time to take part in a 6-day battle for Rosignano, only a dozen miles southeast of Leghorn.

On 11 July the 88th Division came back into the line as a IV Corps unit, relieving the 1st Armored, and the following day the 91st was committed as a division, though its 363rd Regiment remained for the time being attached to the 34th. IV Corps reached the Arno plain on 17 July, and two days later the 34th Division entered the battered port of Leghorn. Pisa fell on the 23rd, and Fifth Army moved up to the Arno on its entire front.

The last of the French units had been withdrawn on 22 July, and Eighth Army had shifted west to fill the gap. Florence fell to Eighth Army on 4 August. By the 15th of that month the Arno River line was secure, and the Adriatic coast was also in Allied hands as far north as the Metauro River above Senigallia. The weakening of Fifth Army to supply troops for operations in southern France, however, had permitted the enemy to withdraw to the Gothic Line in the northern Apennines. Pursuit beyond the Arno was impossible without rest, regrouping, and resupply. The enemy would also have time to recover his strength and to improve his fortified positions.

On the rolling plains northwest of Rome, clearing stations and their accompanying field hospital platoons experienced great difficulty in keeping up with the racing troops. Advances during the first few days of the pursuit were as much as twenty and thirty miles a day, so that a clearing station located within range of enemy guns in the morning might be miles behind by nightfall. Even with frequent moves it was impossible to avoid long ambulance runs. For similar reasons, litter hauls too became long as combat elements outran ambulance control points and even aid stations.

Field hospital platoons found it impossible to move with the same frequency as the clearing stations they supported,

because of the need for giving postoperative care to their patients, and of the inadequacy of their organic transportation. The field hospitals were given six additional 2½-ton trucks in June, making ten in all, but even this number was sufficient to move only one platoon at a time. The problem of caring for patients who could not be moved was solved only by attaching additional field hospital units and by operating the units in two sections. On more than one occasion a single field hospital had seven separate sections in simultaneous operation, all in support of a single division clearing station.

The 10th Field Hospital remained in the line in support of the 85th and 88th Divisions until the relief of II Corps was completed on 11 June. At that time the 11th Field was brought up from bivouac in the Cisterna area, going into action with IV Corps. Platoons of the 33rd Field Hospital followed the VI Corps drive to Civitavecchia, shifting to IV Corps when VI Corps was relieved. For the 33rd, work was light until the end of June, when the 11th was withdrawn to stage for the invasion of southern France. Thereafter the 33rd carried the entire burden of forward surgery for IV Corps, including the relatively heavy casualties from the battles for Cecina and Rosignano.

The pursuit was characterized by alternating periods of heavy fighting and comparative lull, with corresponding peaks and valleys for the medical service. On various occasions, corps medical battalions were compelled to fill in at the division and regimental levels. During the period of severe fighting in the mountainous area around Cecina early in July, and the subsequent advance to Leghorn and Pisa, the clearing station of the 109th Medical Battalion, Supporting the 34th Division, cleared casualties from five regimental combat teams and their attached troops.

The 316th Medical Battalion, organic to the 91st Division, operated as a unit in combat for the first time when the division was committed on 12 July, although collecting companies of the battalion had been in action with the 361st and 363rd RCT’s.

On 3 August, with all but mopping up operations completed, a rest center for Fifth Army medical personnel was established at Castiglioncello, about fifteen miles south of Leghorn on the coast. The camp had accommodations for 50 officers, 25 nurses, and 100 enlisted men. Each group remained four days.

Hospitalization in the Army Area

The long period of preparation for the May drive on Rome gave ample time to clear Fifth Army hospitals, but the nature of the terrain on the Garigliano front, together with the rapid movement of the combat troops once the Gustav Line was broken, prevented close support. Hospitals remained in the Carinola area until late May, while lines of evacuation stretched out to fifty and seventy-five miles along Highway 7.8

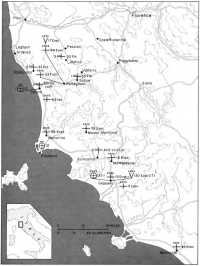

Hospitals supporting II Corps began moving forward after the capture of Terracina. The 95th Evacuation, augmented by the 1st Platoon of the 601st Clearing Company, opened at Itri on 24 May, and the 93rd leapfrogged ten miles farther forward, to Fondi, two days later. The 750-bed 56th Evacuation took over from

the 93rd at Fondi on 1 June, the 93rd going to Campomorto in the Anzio area. At the same time the 95th jumped ahead fifty miles to Con, southeast of the Alban Hills. The 16th Evacuation, meanwhile, had gone by sea to Anzio where it opened on 27 May; and the 8th, after a brief stay at Cellole, between Carinola and Minturno, moved overland to Le Ferriere in the beachhead sector, opening on June. The neuropsychiatric hospital operated by the 601st Clearing Company, and the venereal disease hospital operated by the 602nd Clearing Company, both moved into the Anzio area on 31 May.

Two casualty clearing stations (evacuation hospitals), two field hospitals, three mobile surgical formations, and a mobile surgical group attached to the French Expeditionary Corps were similarly slow in moving up for reasons of terrain and because of the rapid movement of the corps. Additional French hospital units, although requested early in April, were not available in time for the Rome-Arno Campaign.9

As the hospitals moved forward, ambulance control posts were set up to direct the flow of casualties. Movement was facilitated by keeping new casualties out of hospitals scheduled for an early change of location.

General Martin was with the first group to enter Rome, where he quickly located buildings suitable for hospital use. The 94th Evacuation from Anzio and the 56th from Fondi both moved into Rome on 6 June, with the 38th and 15th from Anzio following on 9 and 10 June, respectively. The 38th exchanged its dug-in ward tents with the 59th Evacuation Hospital, newly arrived from Sicily to act as a Peninsular Base Section station hospital at Anzio. (Map 26)

In Rome, the 38th Evacuation set up under canvas in a park near Vatican City. The 15th was located in a school building, while the 94th and 56th shared a large building originally constructed for hospital use by one of the religious orders and recently operated as a military hospital by the Germans—so recently, in fact, that pots of coffee and vats of beans were still warm in the kitchen when the Americans arrived. Although it was recognized that these evacuation hospitals did not have the organic personnel necessary for cleaning and maintenance of fixed structures, General Martin felt that the service they would render in preparing the buildings for later occupancy by PBS units would more than outweigh the disadvantages.10

The last of the Fifth Army hospitals from the southern front, the 3rd Convalescent, moved into the Anzio area on 9 June, opening at Le Ferriere. Movement had been delayed by lack of transportation and congested roads.

In the pursuit north of Rome, where the terrain was well adapted to the use of armor, the combat troops quickly outdistanced their supporting hospitals, and lines of evacuation once more lengthened out, up to 100 miles. Here the main axis of advance for the U.S. forces was Highway 1, along the Mediterranean coast, with the French Expeditionary Corps, supported in part by American medical units, using Highway 2, farther inland. The first hospital to move into the new combat zone was the 11th Evacuation, which opened at Santa Marinella,

map 26: Fifth Army Hospitals and Medical Supply Dumps, 10 June 1944

just below Civitavecchia, on 10 June. The new location was 40 miles northwest of Rome and more than 80 miles from the hospita’ls former Anzio site. The following day the 93rd opened at Tarquinia, some 15 miles farther north. On 13 June the 95th Evacuation was established at Montalto di Castro, 10 miles beyond Tarquinia, where it was joined by the 94th two days later. The 400-bed evacuation hospitals were usually moved in pairs, the organic transportation of the two units being pooled to move first one, and then the other.

Throughout this period, communication was poor and lines of evacuation were maintained only by great effort. The advance of the front was so rapid

Institute of the Good Shepherd in Rome, occupied jointly by the 38th and 94th Evacuation Hospitals

that the Signal Corps was unable to include the hospitals in its telephone network. Pigeons were used to some extent, but for the most part communication was maintained by couriers driving jeeps hundreds of miles a day. The 8th Evacuation Hospital, for example, sent an advance party to lay out a site near Orbetello, 20 miles beyond the 94th and 95th, on 16 June. The party was met by an ambulance driver who had already come 50 miles from the front in search of a hospital. The 8th’s commander, Col. Lewis W. Kirkman, hastily changed plans and after making contact with the Fifth Army surgeon by courier, ordered the hospital established 4 miles south of Grosseto. The new site was only 6 miles from the point of contact with the enemy, but by the time the hospital was ready to receive patients the front was a safe distance away.

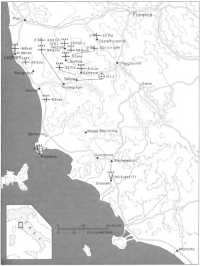

Other moves were made toward the end of June. The 15th Evacuation moved from Rome to Grosseto on the 23rd of the month. The 94th left Mont-alto on the same day to set up at Montepescali, 10 miles south of Grosseto, where it was joined on 27 June by the 16th Evacuation. The 3rd Convalescent moved to Grosseto on 29 June. Also on 29 June the 56th Evacuation opened at Venturina, near Piombino, 30 miles northwest of Montepescali. The

venereal disease hospital moved on 26 June to Guincarico, about 5 miles from the sites of the 94th and 16th Evacuation Hospitals. The 38th Evacuation shifted from Rome to Massa Marittima, about 10 miles north of the venereal disease center, on 2 July.

By this date the rate of advance had slowed owing to the withdrawal of substantial forces for the invasion of southern France and to the more rugged terrain. For the first time since the fall of Rome the location of hospital sites with respect to availability of air evacuation became a problem, requiring reconnaissance from the air as well as on the ground. Hospitals caught up with the combat troops, and even outdistanced organic medical units on occasion. The 8th Evacuation for example, moved into the outskirts of Cecina while the fighting for that town was still in progress and was actually set up on 2 July forward of the 34th Division clearing station.

The next series of moves came toward the middle of July, when the 11th, 93rd, and 95th Evacuation Hospitals were withdrawn from Fifth Army. The 94th Evacuation, with a platoon of the 601st Clearing Company attached, moved up to Ponteginori, about ten miles east of Cecina along the road to Florence, on 11 July; and the venereal disease hospital moved into the same area four days later. At the same time the neuropsychiatric hospital was established at Cecina. The 38th Evacuation opened on the coast road, twelve miles above Cecina, on 18 July, after a 24-hour delay because the area was still under fire. The 15th Evacuation moved to Volterra, a few miles beyond the site of the 94th. The 32nd Field Hospital, released from attachment to the Peninsular Base Section, was established at Saline, halfway between the 15th and 94th Evacuations, on 23 July.

The 16th Evacuation operated at Ardenza, on the southern outskirts of Leghorn, from 26 July to 12 August. The 3rd Convalescent moved on 2 August to Laiatico, twenty miles southeast of Leghorn; and the 56th Evacuation was established three days later about five miles farther north, at Peccioli. On 8 August the 6oist Clearing Company set up its neuropsychiatric hospital at Montecchio, a mile or two south of the Peccioli site of the 56th Evacuation. The front was stabilized at about this time, with the actual fighting reduced to patrol actions along the Arno River line. (Maps 27, 28)

The Rome-Arno Campaign again demonstrated the value of the separate ambulance company, of the 400-bed evacuation hospital, and of the field hospital platoon as a forward unit. The shortcomings of these platoons with respect to size were overbalanced by their mobility in a campaign of rapid movement. The capacity of the 400-bed evacuation could be readily increased, even beyond its own expansion limits, by the attachment of one or more clearing platoons from the corps medical battalions. The field hospital platoons operating with the division clearing stations were also augmented from time to time by additional personnel and beds from other sources. In the Rome-Arno Campaign the field hospital platoons were able to move forward with the divisions they supported because holding units to care for their nontransportable patients were improvised from personnel of the corps medical battalions, with nurses borrowed from evacuation hospitals. As

Map 27: Fifth Army Hospitals and Medical Supply Dumps, 15 July 1944

Map 28: Fifth Army Hospitals and Medical Supply dumps, 15 August 1944

img310 Table 11: Admissions to Hospital and Quarters from Fifth Army, May–August 1944

| ?Month | All Causes | All Nonbattle | Disease | Injury | Battle Casualties | Mean Strength* |

| May | 23,586 | 15,462 | 12,499 | 2,963 | 8,124 | 236,826 |

| June | 32,623 | 21,677 | 17,570 | 4,107 | 10,946 | 231,360 |

| July | 21,219 | 14,836 | 12,313 | 2,523 | 6,383 | 162,003 |

| August | 12,555 | 11,723 | 9,928 | 1,795 | 832 | 151,133 |

* U.S. strength only.

Source: Annual Rpt, Surg, Fifth Army, 1944.

in previous Mediterranean campaigns, surgical, shock, and other specialist teams of the 2nd Auxiliary Surgical Group worked with the field hospital platoons and the evacuation hospitals. The usual complement was one shock and four surgical teams for each field hospital platoon.11

It should be noted in this connection that the 750-bed evacuation hospitals in the Italian campaign were moved with much greater speed than had been the case in Tunisia. The 8th Evacuation, for example, struck its tents, moved 80 miles from Cellole to Le Ferriere, and set up again for operation in 30 hours, while the 38th closed in Rome, moved 160 miles to Massa Marittima, and reopened in 40 hours. The improvement owed something to accumulated experience, but more to the effective cooperation of corps and army in providing the necessary trucks when they were needed. For the most part, however, these larger units were not required to make rapid changes of position. As the lines of combat moved forward, the 750-bed evacuation hospitals tended to function toward the rear of the army area more as fixed than as combat units, eventually being replaced by base section hospitals.

Admissions to hospital and quarters from Fifth Army during the period of the Rome-Arno Campaign reached a peak in June of more than 32,000, of which one-third were battle casualties. (Table 11)

Evacuation From Fifth Army

For the first two weeks of the drive on Rome, evacuation from Fifth Army continued to follow the pattern of the preceding months. Casualties from the southern front were evacuated from the Carinola area by rail to Naples. The 41st Hospital Train, controlled by the Peninsular Base Section, operated between that city and the Sparanise railhead. The 42nd Hospital Train, scheduled for southern France, was brought over from Africa and went into service between Sessa, near the main concentration of Fifth Army hospitals, and Naples, starting 12 May. As had been the case in Africa, the necessary hospital cars were converted from local rolling stock. Holding

Table 12: Air evacuation from Fifth Army hospitals, 26 May–31 August 1944

| ?From | To | Air Miles | 802nd MAETS | 807th MAETS | Total |

| Total | 15,984 | 17,809 | 33,793 | ||

| Priverno | Naples | 70 | 221 | 135 | 356 |

| Nettuno | Naples | 95 | 6,105 | 3,407 | 9,512 |

| Palo | Naples | 135 | 381 | 454 | 835 |

| Cerveteri | Naples | 140 | 94 | 94 | |

| Tarquinia | Naples | 160 | 107 | 138 | 245 |

| Montalto | Naples | 170 | 510 | 724 | 1,234 |

| Castiglione | Naples | 190 | 3,962 | 2,521 | 6,483 |

| Ombrone (Grosseto) | Naples | 205 | 688 | 709 | 1,397 |

| Rosia | Naples | 225 | 1,323 | 550 | 1,873 |

| Follonica | Naples | 230 | 323 | 61 | 384 |

| Cecini | Naples | 250 | 63 | 63 | |

| Ombrone | Rome | 90 | 34 | 594 | 628 |

| Follonica | Rome | 110 | 208 | 4,452 | 4,660 |

| Rosia | Rome | 115 | 22 | 228 | 250 |

| Cecina | Rome | 140 | 2,100 | 3,442 | 5,542 |

| Cecina | Grosseto | 50 | 237 | 237 |

Figures include patients from the French Expeditionary Corps, from the British components of VI Corps, from the Anzio area, and some Italian military and civilian personnel. Flights from the Eighth Army sector have been excluded, but some Eighth Army casualties are not separable from Fifth Army figures. Excludes Air Forces casualties insofar as possible.

Source: Annual Rpts, 802nd and 807th MAETS, 1944.

hospitals at the railheads were maintained by the corps medical battalions. Casualties from Anzio continued through most of May to be evacuated exclusively by hospital ships and by LSTs staffed by teams from the 56th Medical Battalion.

On the fifth day of the attack the encampment of the 56th Medical Battalion near Nocellito was bombed in bright moonlight, apparently deliberately, with two enlisted men killed, seven wounded, and extensive damage to equipment.

After the consolidation of the two fronts, air evacuation began from the army area, and thereafter, for the remainder of the campaign, forward hospitals were cleared by planes of the 802nd and 807th Medical Air Evacuation Transport Squadrons. The first flight from the Nettuno airstrip was made on 26 May. Air evacuation for both U.S. and French forces was directed by the Office of the Surgeon, Fifth Army, which had made proximity to an airfield or to level ground where an airstrip might be constructed a condition in the selection of hospital sites. By 1 June approximately 400 patients a day were being flown from the combat zone to fixed hospitals in Naples and Caserta.12 (Table 12)

Holding units for air evacuation were operated at various points by two

Table 13: Evacuation from Fifth Army to PBS Hospitals, 1 January–31 August 1944

| ?Month | Ambulance | Rail | Hospital Ship | LST | Air | U.S. Army | Total* |

| Total | 23,473 | 15,071 | 30,271 | 2,950 | 23,397 | 80,299 | b 102,298 |

| January | 5,094 | 8,874 | 2,768 | 0 | 0 | 15,020 | 16,736 |

| February | 3,639 | 826 | 9,070 | 0 | 0 | 12,794 | 13,535 |

| March | 2,312 | 0 | 4,986 | 647 | 0 | 7,655 | 7,945 |

| April | 1,375 | 0 | 4,361 | 607 | 0 | 6,063 | 6,343 |

| May | 6,367 | 5,371 | 6,546 | 1,696 | 5,185 | 15,846 | 25,165 |

| June | 905 | 0 | 2,540 | 0 | 3,855 | 8,928 | † 14,436 |

| July | 3,067 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10,973 | 10,403 | 14,040 |

| August | 714 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,384 | 3,590 | 4,098 |

* Includes U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, Allies, POW's.

† Includes 7,136 patients for whom no means of evacuation is given. Most of these were probably evacuated by air, which explains in part the large discrepancy between the total evacuated by that means shown in this and in the preceding table, The remainder of the discrepancy may be accounted for in British casualties, not taken to PBS hospitals.

Source: Annual Rpt, Surg, MTOUSA, 1944, an. B, app. 18.

collecting companies of the 161st Medical Battalion and by the clearing company and one collecting company of the 163rd Medical Battalion. The 56th Medical Battalion handled both air and sea evacuation at Anzio until 23 June, when it was relieved by the 54th and departed for Naples to stage for the invasion of southern France. The 402nd Collecting Company of the 161st Medical Battalion, assigned to the French Expeditionary Corps, even helped to construct and maintain an airstrip, and directed the approach and take-off of the C-47 transports.

Transportation between hospitals and airfields was handled by corps medical battalions. The 162nd Medical Battalion also cleared patients from evacuation hospitals in Rome to the 59th Evacuation, which functioned as a Peninsular Base Section station hospital at Anzio until 23 June. By this date more than 3,000 fixed beds were available in the Italian capital, so that forward evacuation hospitals began sending casualties to Rome instead of to Naples and Caserta.

During the entire 7-month period of the Anzio, Cassino, and Rome-Arno Campaigns, casualties were evacuated from Fifth Army hospitals to Peninsular Base Section installations by ambulance, hospital train, hospital ship, LST, and transport plane. The figures are not reported by campaigns, only on a monthly basis. For the period 1 January-31 August 1944 the total was 102,298. (Table 13)

Medical Supplies and Equipment

Like the Fifth Army hospitals, the supply dumps of the 12th Medical Depot Company moved forward only after II and VI Corps had joined at Anzio. The

Loading an ambulance plane on Nettuno airstrip, June 1944

company headquarters and base platoon and the 2nd Platoon went from Calvi Risorta to Nocellito on 20 April, in the general alignment of Fifth and Eighth Armies. The 2nd Platoon moved forty-five miles to Itri on 23 May, and went on to Rome on 9 June. Headquarters and the base platoon had meanwhile moved from Nocellito to Anzio on 5 June, where the 1st Platoon reverted to control of the parent company.13

The 1st Platoon was established in Civitavecchia on 11 June, only four days after the capture of the city and before the harbor had been cleared. On 18 June, headquarters and the base platoon went on to Grosseto. Ten days later the 2nd Platoon turned over the supply function in Rome to Peninsular Base Section installations and followed the rapidly moving army to Piombino. The 1st Platoon was in Cecina on 9 July.

The 12th Medical Depot Company was reorganized at this time, the personnel complement being reduced from 178 to 150. The three platoons were

redesignated the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Storage and Issue Platoons.14

Headquarters and the 1st Storage and Issue Platoon moved from Grosseto to Saline on 30 July, where they were joined on 14 August by the 3rd Storage and Issue Platoon. The latter unit was established in the vicinity of Florence at the end of the month.

In all these rapid changes of position, one platoon of the 12th Medical Depot Company was always in support of each of the two U.S. corps engaged, with the headquarters group accessible to both. The French Expeditionary Corps had its own system of combat medical supply, which was organized under the same U.S. Table of Organization as its American counterpart, and was supplied through the same channels.15

Medical supplies were brought up by water, air, and truck as circumstances dictated, with no shortages developing except the perennial shortages of blankets, litters, and pajamas stemming from faulty property exchange with air evacuation units. This shortage was felt at all airstrips used for evacuation, since the incoming planes were on other missions, which generally precluded the carrying of bulky medical items.

One of the features of the supply system, in the later phases of the campaign, was the daily arrival of whole blood by plane from the 15th Medical General Laboratory.

Professional Services in the Army Area

The months of March and April 1944, when the armies were regrouping and re-equipping for the crushing attack that would carry Allied power to the Arno River, were used by the Medical Department to review past practices and improve techniques for the future. The conferences and seminars that medical officers had been able to attend only spasmodically up to that time were systematized, with all phases of the work of the medical service being discussed. Medical officers of all levels profited by these interchanges before they returned to active combat support.16

Medicine and Surgery

Forward Surgery

The techniques of forward surgery in the Rome-Arno Campaign did not differ greatly from those employed during the preceding eight months in Italy. While there were a number of clinical improvements, including a more extensive use of penicillin and the unrestricted availability of whole blood in the field hospital platoons, the only important administrative change was the withdrawal of twenty-eight teams, or half of the entire Complement, of the 2nd Auxiliary Surgical Group early in July to stage for the coming invasion of southern France.17 The loss of these teams was not made up until the next stage of the Italian campaign.

Neuropsychiatry

The early success of the 3rd Divisions experiments at Anzio in treating psychiatric cases at the division level led General Martin to initiate similar experiments in the 88th

Division, which had not yet been in combat. It was hoped that the incidence of psychiatric casualties could be reduced if adequate facilities for early treatment existed from the start.18

The 88th Division Training and Rehabilitation Center was formally established on 18 April 1944, commanded by a line officer with two noncommissioned officers as assistants, all with extensive combat experience. The division psychiatrist, Capt. (later Maj.) Joseph Slusky, acted as consultant. The center was attached for rations and quarters to the clearing company of the 313th Medical Battalion. Actual operation began on 11 May when the division went into combat. The procedure was simple, but effective.

An exhaustion or psychiatric case admitted to the clearing station was examined by the division psychiatrist, who evaluated the severity of the symptoms. The patient was retained at the clearing station for two or three days, where he was given sodium amytal three times a day after meals. Sedation was sufficient to ensure adequate rest and sleep, but not heavy enough to keep the patient from going to mess and otherwise taking care of himself. After 24 to 48 hours of this treatment, the patient was again examined by the division psychiatrist. If he appeared to be responding, he was retained. If not, he was transferred to the Fifth Army Neuropsychiatric Center, operated by the 601st Clearing Company.

The patients who showed improvement under sedation were given suggestive and supportive therapy and turned over to the division Training and Rehabilitation Center, where they were given lectures combined with calisthenics, hikes, and other physical activities, including tactical training with weapons. Most were ready to return to duty after two days at the center. Others were retained for a few days longer, while those whose symptoms persisted were evacuated to the neuropsychiatric hospital.

Each patient was re-examined by the division psychiatrist before returning to combat and was given a final therapy session oriented toward reassurance. Returns to duty were made through non-medical channels.

The record for the period 11 May–9 June, during which the 88th was in continuous combat under particularly difficult conditions, showed a total of 248 psychiatric admissions to the division Training and Rehabilitation Center. Of these, 141 or 56.9 percent, were returned to duty from the center. One hundred and four were evacuated to the 601st Clearing Company, from which 24 were later returned to duty. Total returns to duty were thus 165, or 66.5 percent. Eighty, or 32.3 percent, were lost to the division. Two remained under treatment at the end of the period, and one was absent without leave.

The results of this experiment led to an order of 2 July 1944 directing all divisions of Fifth Army to establish similar training and rehabilitation centers. Thereafter, admissions to the Fifth Army Neuropsychiatric Center were exclusively by transfer from these division installations. A Fifth Army consultant in neuropsychiatry, Maj. (later Lt. Col.)

Table 14: Disposition of Neuropsychiatric Cases in Fifth Army, May–August 1944

| ?Month | Returned to Duty | Evacuated From Army Area | Total Dispositions | ||||

| From Divisions | From Hospitals | ||||||

| No. | Percent | No. | Percent | No. | Percent | ||

| May | 283 | 16.0 | 437 | 24.6 | 1,054 | 59.4 | 1,774 |

| June | 429 | 26.0 | 454 | 27.5 | 767 | 46.5 | 1,650 |

| July | 378 | 23.5 | 487 | 30.3 | 744 | 46.2 | 1,609 |

| August | 105 | 13.6 | * 254 | 32.8 | 415 | 53.6 | 774 |

* Includes 95 returned to limited or Class B duty.

Source: Annual Rpt, Surg, Fifth Army, 1944.

Calvin S. Draper, was also named at this time. A further development, which went into effect the first of August, was the return of certain neuropsychiatric casualties to limited or noncombat duty in the army area, a disposition board for this purpose being set up by the 3rd Convalescent Hospital.

In general, the psychiatric cases developing in the drive to Rome and the subsequent pursuit to the Arno River were less severe than those encountered during the static fighting before Cassino and on the Anzio beachhead. The incidence was higher in the divisions new to combat, but the response to treatment in these divisions was excellent. The record of the 88th Division has already been noted. The 91st returned 68.1 percent of its 116 psychiatric casualties to duty between 13 and 31 July when the division was in combat. The 85th Division, out of action between 1 July and 15 August, had a smaller total of such cases, 76 being admitted in this period to the division training and rehabilitation center, but the cases proved more obstinate, only 51 percent being returned to duty at the division level.

The disposition of psychiatric cases in Fifth Army as a whole for the last four months of the Rome-Arno Campaign is shown in Table 14.

Common Diseases

Malaria in Fifth Army reached the year’s peak of 94 cases per 1,000 per annum in June 1944, dropping only slightly to 82 in July. During these two months the season was at its height, and the army was operating in areas that had been controlled by the enemy during the earlier part of the breeding season. Atabrine continued to be the primary preventive measure available, the use of netting and gloves being for the most part impractical in combat.

A sharp rise in the incidence of diarrhea and dysentery (including bacterial food poisoning) from 28 per 1,000 per annum in May to 102 in June and 135 in July may be explained by the simultaneous advent of warm weather, the fly season, and the fresh fruit season. Even the July figure, however, was far below the rate of 195 cases per 1,000 per annum experienced in June 1943 in North Africa. Insecticides were available in adequate quantities, and the diseases were quickly overcome when the period

Table 15—Venereal Disease Rates by Division, Fifth Army, May–August 1944*

| ?Month | 1st Armored | 34th Infantry | 3rd Infantry | 45th Infantry | 36th Infantry | 88th Infantry | 85th Infantry | 91st Infantry |

| May | 57 | 71 | 23 | 55 | 63 | 44 | 10 | † |

| June | 22 | 40 | ‡ | 67 | 12 | 32 | 20 | 8 |

| July | 33 | 54 | ‡ | ‡ | 45 | 56 | 12 | |

| August | 38 | 144 | 34 | 36 | 11 |

* Rates expressed as number per annum per 1,000 average strength.

† Not yet in Italy.

‡ Withdrawn from Fifth Army.

Source: Annual Rpt, Surg, Fifth Army, 1944.

of active fighting came to an end in early August.

Venereal disease in the summer of 1944 followed a predictable pattern, the rate being relatively low during periods of combat and high during the rest and bivouac periods. (Table 15) The rate continued to be highest among veteran troops.

Dental Service

On 6 May 1944, just before the launching of the drive on Rome, the Fifth Army dental surgeon, Colonel Cowan, was returned to the United States on rotation. His acting successor was Maj. (later Lt. Col.) Clarence T. Richardson of the 16th Evacuation Hospital.19

Major Richardson inherited a dental establishment much better equipped to fulfill its mission than the one Colonel Cowan had taken to Salerno eight months earlier. Facilities for prosthetic work were still less than adequate, but in other respects Fifth Army began the drive to Rome well prepared to meet the dental requirements of its troops. Each of the divisions had improvised laboratory facilities. In addition, three of the four mobile dental laboratories—built on 2½-ton truck chassis—reaching the theater in May were assigned to Fifth Army, the fourth going to the Air Forces.

By June, when IV Corps went into the line north of Rome, the Fifth Army Dental Clinic, operated by the 602nd Medical Clearing Company, was functioning smoothly enough to care for all cases that could not be handled by the divisions. IV Corps, accordingly, set up no dental clinic of its own, while the II Corps clinic was discontinued toward the end of the month. Aside from inadequate prosthetic facilities, the only serious defect in the Fifth Army dental setup at this time was the familiar problem of getting dental services to troops in distant positions, and the correlative loss of man-hours in sending men to the rear to the Army clinic.

The reorganization of July gave a

Field unit of the Fifth Army Dental Clinic in the Piombino area, July 1944

dental unit to the 12th Medical Depot Company, but personnel and facilities for it were not available until fall.

For Fifth Army as a whole, the ratio of dental officers to troop strength dropped sharply from one dental officer for each 987 men in May 1944 to one for each 1,019 men in June. The July and August ratios were 1:915 and 1:963, respectively. The work accomplished by these officers and their staffs during the last four months of the Rome-Arno Campaign is summarized in Table 16.

Veterinary Service

The May 1944 offensive carried Fifth Army through some of the most rugged and difficult terrain in Italy. In the drive from the Garigliano front to Rome, II Corps was supported by eight Italian pack trains, with an aggregate strength of 97 horses and 1,897 mules. Divisional animals, including those assigned to two pack field artillery battalions, included 106 horses and 1,270 mules. Pack trains of the French Expeditionary Corps in the

Table 16: Dental service in Fifth Army, May–August 1944

| ? | May | June | July | August |

| Admissions | 20,569 | 15,599 | 15,298 | 17,289 |

| Sittings | 34,951 | 23,876 | 24,969 | 27,316 |

| Restorations | 30,031 | 19,651 | 19,564 | 21,764 |

| New dentures | 1,296 | 773 | 796 | 1,000 |

| Dentures repaired | 426 | 240 | 394 | 423 |

| Teeth extracted | 7,034 | 3,959 | 4,655 | 4,612 |

| Teeth replaced | 9,933 | 6,316 | 6,697 | 7,193 |

| Total operations | 72,115 | 50,989 | 55,737 | 56,777 |

| Restorations per officer | 135 | 92 | 123 | 153 |

| Operations per officer | 309 | 239 | 351 | 395 |

| Days of duty | 6,911 | 6,407 | 4,912 | 4,400 |

Source: Annual Rpt, Surg, Fifth Army, 1944.

same operation utilized 2,023 horses and 7,266 mules. In the drive, 146 animals were killed in action and 1,111 were wounded. The particularly heavy animal casualties in the French sector made it necessary to attach the 1st Veterinary Hospital (Italian), a Peninsular Base Section unit, to the French Expeditionary Corps.20

Veterinary hospitals in support of Fifth Army experienced considerable difficulty in finding sites with buildings suitable for animal use. Close support was nevertheless given by these units. The Italian-staffed 110th Veterinary Hospital moved from the Carinola area to Nettuno on 20 June, and to Rome on 4 July. The 130th Veterinary Hospital, also Italian staffed, moved from Nocellito to Rome on 1 July, to Grosseto a week later, and to Saline on 1 September. The U.S. 17th Veterinary Evacuation Hospital, supporting the 601st and 602nd Field Artillery Battalions, moved seven times between 4 April and 15 July. Among its operating sites were Monte San Biagio near Terracina; Cori and Nemi in the beachhead area; Castagneto, south of Cecina; and Ponteginori west of Cecina on Highway 68. With the battalions it supported, the 17th was assigned to Seventh Army on 20 July.

Replacements for animal casualties were supplied by the Base Remount Depot, operated by Peninsular Base Section. To minimize delay as much as possible, however, each veterinary hospital maintained a small exchange unit that supplied a sound animal for each wounded one received. Only on the French front, where animals were most numerous and casualties heaviest, did the system break down. In those cases where hospital exchange units were exhausted, fresh animals were allotted by Fifth Army.

When flat or rolling country was reached after the fall of Rome, all animal units were placed in rest areas, where they remained throughout the summer. The only exception was a

period in July when elements of the 1st Armored Division, operating in mountains between Massa Marittima and Volterra, substituted horses for half-tracks and trucks.

During the rest period, all Italian pack trains and veterinary hospitals were reorganized in accordance with U.S. Tables of Organization and Equipment. Four new Italian pack companies were also organized at this time, and the 20th Mule Pack Group, which controlled all the Italian pack trains, set up a center under Colonel Canani for training recruits in the handling of pack animals.21

Medical Support for the Eastern Command

Before the end of 1943, negotiations began for the use of Russian airfields by U.S. bomber squadrons based in Italy and in the United Kingdom. Arrangements were finally completed in the spring of 1944, with the designation of three bases in the Ukraine. The headquarters base was at Poltava, 200 miles east of Kiev. The others were located at Mirgorod, 50 miles west of Poltava, and at Piryatin, another 50 miles in the direction of Kiev. Collectively, they were administered as the Eastern Command (EASCOM). The first flight, made by planes of the Fifteenth Air Force from Italy on 2 June 1944, was timed to be contemporaneous with the capture of Rome and the launching of the Normandy invasion. The first task force of B-17’s, personally led by General Eaker, destroyed marshaling yards and shops at Debrecen in eastern Hungary before ending its mission at Poltava airfield.22

Lt. Col. William M. Jackson, Eastern Command surgeon, established his headquarters at Poltava, where his staff included a Veterinary Corps officer and a Sanitary Corps officer. Each of the three bases was supported by a 75-bed provisional hospital expanded from a 24-bed aviation dispensary. Instead of the two medical officers called for in the TOE, the Poltava and Piryatin hospitals had four each, while Mirgorod had three. Each hospital had the one dental officer and one supply officer (MAC) provided in the TOE, and each had four nurses. Eighty-five enlisted men, divided among headquarters and the three hospitals, brought total Medical Department personnel to 117. All medical personnel and facilities came from the United Kingdom.23

The first problem faced by Colonel Jackson and his staff was one of sanitation. Whatever war may have left of water and sewerage systems had been destroyed by the Germans as they retreated, together with virtually all buildings. The Russians had been too short of medical personnel themselves to take

adequate preventive measures, and typhus, malaria, dysentery, and venereal diseases were prevalent. In the absence of buildings, the hospitals were set up in tents, close to the airfields they served. The hospital at Piryatin was well concealed in a wooded area near a river, but those at Poltava and Mirgorod were in open fields. All units were established and ready to receive patients by 1 June.

The medical service of the Eastern Command underwent its acid test three weeks later. The first shuttle bombing mission by the Eighth Air Force from British bases arrived at Poltava the afternoon of 22 June after a successful raid on a synthetic oil plant south of Berlin. The bombers were apparently trailed to their destination by a German plane, and that night the Poltava field was attacked in force. At the time of the attack there were 370 permanent and 714 transient U.S. personnel at the base.

It was estimated that 110 tons of bombs were dropped over a 2-hour period. Every one of the 73 B-17’s on the field was hit and 43 were destroyed, together with 3 C-47’s, one F-5, numerous ground vehicles, and quantities of gasoline, oil, bombs, and ammunition. Twenty-five Russian YAK fighters were also damaged on the ground. Two Americans, a pilot and copilot, were killed and 14 wounded. The Russians, who manned the antiaircraft batteries and fought the fires on the field, lost 30 killed and 95 wounded. First aid was given in the slit trenches that served for shelter, the wounded being moved to the hospital when the raid was over.

The following night the other two bases were attacked, but with less disastrous results. A gasoline dump was hit at Mirgorod, but at Piryatin the Germans failed to locate the target and contented themselves with bombing the town.

Poltava was nonoperational for forty-eight hours and operated to a limited extent only for a month. Russian sappers were still locating and detonating unexploded bombs as late as 7 September.

After the attacks of 22-23 June, installations were dispersed as much as possible. The hospitals were relocated some distance from the airfields, and an attempt was made to enlarge the available medical facilities. A request for a 400-bed field hospital to replace the three outsize dispensaries was refused, however, on the ground that no field unit was available for that purpose.24

The bases became steadily less important as the Russian front pushed westward and the advance of the Allied Armies in Italy and France brought more enemy targets into normal bomber range. Personnel were gradually withdrawn until by 1 October only Poltava retained a medical complement, reduced to 3 medical officers, 4 nurses, and 14 enlisted men. Housed in three prefabricated barracks, this unit continued into 1945, but performed only routine dispensary functions.

The medical installations of the Eastern Command were supplied from Tehran, and during the period of greatest activity patients were evacuated by air to the 19th Station Hospital in

that city. After 1 October 1944, evacuation was to the 113th General Hospital at Ahwaz, Iran. Considering the unsanitary conditions and the prevalence of disease in the Eastern Command, the medical service was excellent. The average weekly noneffective rate was 18.32 per 1,000 only a little higher than that for similar units in the United Kingdom.