Chapter 2: The Ordnance Department: 1919–40

The nearly twenty years between the Armistice of November 1918 and the German Anschluss with Austria in March 1938 saw the American public gradually shift from hope in the possibility of enduring peace to uneasy perception that aggressive force was again taking command of the international scene. For the Army, and for the Ordnance Department in particular, changes in public opinion, expressed through Congressional appropriations, set the pattern of activity; the amount of money available for maintenance, development, and manufacture of fighting equipment always imposed the limits within which the Ordnance Department could work. Had judgment invariably been faultless in interpreting the importance of foreign arms developments, had the Army evolved the most comprehensive, sound doctrine of what weapons were needed for mechanized warfare and how an army in the field should use them, and had the Ordnance Department devised an ideal scheme of procurement and maintenance of munitions, all this must still have been useless without money enough to turn ideas into matériel. Hence, funds voted by the Congress, generally adhering to the dictates of American public opinion, determined the scope of Ordnance work.

At the end of World War I the United States, shocked by recent discovery of its military weakness, appeared to be ready to support an army large enough and sufficiently well-armed to prevent a repetition of the unpreparedness of 1917. The Ordnance Department was instructed to assemble, store, and maintain the equipment that had belatedly been manufactured in the United States or had been captured from the enemy. These stores alone might serve, so the Congress could believe, to guarantee American military strength for some years. Belief in the need of a sizable military establishment endured only long enough to put on the statute books the National Defense Act of June 1920 before a reaction swept away all idea of American participation in international affairs and, at the same time, interest in the Army. The slogan “Back to Normalcy,” which carried Warren G. Harding into the White House, spelled not only repudiation of the League of Nations but rejection of plans to build a strong peacetime Army. Budget cuts for the War Department soon made unattainable the Army of 280,000 men and 18,000 officers authorized by the National Defense Act and reduced the Ordnance Department program to a shadow of the substance hoped for.

Meanwhile, despite American refusal to

join the League of Nations, a steadily mounting pressure to work for permanent peace began to make itself felt. This pressure somewhat altered the temper of the Congress, encouraging small appropriations for national defense. The naval building truce of 1922, followed by the Locarno Pact in 1925, and the high point of faith in world peace reached with the signing of the Kellogg-Briand Pact in 1928, made reasonable the hope that the Army need be only a police force. If war could be outlawed, Ordnance equipment could be kept at a minimum.

The depression of the thirties called a sudden halt to America’s efforts to play a leading role in establishing permanent world peace. The general attitude now became: “Attend to problems at home and let other nations take care of themselves.” Appropriations for the Ordnance Department in the early thirties were reduced to save money, apparently without regard to achieving any purely moral goal. Temporarily, additional funds from PWA and WPA bolstered the Ordnance Department. The public could view the later, larger allocations of money for Ordnance as part of a make-work program, primarily a means of shoring up the whole economy. Absorbed in domestic troubles, the United States turned its back upon Europe and Asia. The Italo-Ethiopian war, the German occupation of the Rhineland, the “dress rehearsal” of the Spanish Civil War, and the Japanese “incident” in Manchuria failed to rouse profound apprehensions in the United States. Conscientious military observers could report upon German rearmament and append data on new weapons, but the Ordnance Department, even if it digested the information, could not act upon it.

A partial awakening to the new aggressive spirit abroad that might involve the United States, rigid isolation notwithstanding, came with the German march into Austria in March 1938. It is reasonable to believe that this move helped the passage of the first act permitting the War Department to place “educational orders” with private industry. Antedating by over two years President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s proclamation of a national emergency, the permission to spend money to give commercial concerns experience in manufacturing munitions marked the beginning of a new era. The next eighteen months, while public opinion veered steadily toward acceptance of national rearmament, saw greatly increased activity in the Ordnance Department. Yet by 1940 the task was just begun.

Because ordnance matériel takes years to design, test, and manufacture, and because it takes years to teach troops to use the finished product, full understanding of the Ordnance situation in 1940 calls for examination of the problems, achievements, and shortcomings of the Ordnance Department in the preceding twenty years. From 1920 to 1940 plans had always to be shaved down, operations were always restricted, projects were frequently stopped short of completion, all for lack of money. This fact must be borne in mind, but it cannot in itself explain 1940. Hence it is necessary to explore the evolution of careful industrial mobilization plans; the performance of the newly created Field Service Division; the mapping and partial execution of a comprehensive artillery development program; the experimentation with tank design; the difficulties besetting Ordnance designers in developing weapons that would satisfy the using arms, yet, if possible, anticipate the emergence of Army doctrine adapted to

modern mechanized warfare; and finally, the consequences of faulty use of technical intelligence about new foreign equipment. Inasmuch as ordnance cannot be hastily improvised, the ideas that took shape during the peace years demand attention. Activities long established and conducted along accepted lines warrant no discussion here, for they represent no new facet of Ordnance Department problems. The organization of the Department must be described briefly in order to supply the framework within which operations were carried on. Some analysis of the budget and yearly appropriations must, of course, be included. But though ever-present financial considerations, be it repeated, and the earmarking of sums for particular projects limited Ordnance activities between wars, the pattern was not determined by money alone.

Organization, 1919–39

World War I proved to the War Department and all its branches that its administrative machinery must be revamped; what had sufficed for the tiny standing Army of the early years of the century could not bear the load that emergency put upon it.1 The National Defense Act of 1920, which established the new over-all organization of the War Department, affected the Ordnance Department immediately in two respects. The first was the increase in the number of officers and enlisted men assigned to Ordnance. Before 1917 the Ordnance Department had been limited to 97 officers; after 1920 it was allotted a major general, two brigadier generals, 350 other officers, and 4,500 enlisted men. Notable though this increase would appear, it was only 1.9 and 1.6 percent, respectively, of the maximum officer and enlisted strength allowed the whole Army, and in actuality for twenty years it was never achieved. The second and greater consequence of the act for the Ordnance Department lay in the provision of Section 5a, which gave the Assistant Secretary of War “supervision of the procurement of all military supplies and other business of the War Department pertaining thereto and the assurance of adequate provision for the mobilization of matériel and industrial organizations essential to wartime needs.”2 Coordination of purchasing activities through the Assistant Secretary was intended to prevent a repetition of the World War I competition for facilities among separate supply bureaus within the Army. It meant that all the services of supply henceforward were to operate both through military channels by way of the General Staff and through civilian via the Assistant Secretary of War.

The Chief of Ordnance did not wait for Congressional action before reorganizing his own Department. Because he believed that the 1918 experience proved the inherent weaknesses of any purely functional plan of organization, General Williams early in 1919 realigned responsibilities, setting up a simple, logical scheme which, with minor changes, served as the basic pattern within the Ordnance Department all through the peace years. In describing his plan and the slight revisions he put into effect in the fall of 1920, he told a group at the General Staff College: “There is no question in the minds of all of us who have had experience in the Ordnance Department but that the subjective system of

organization is far superior to the functional,”3 “Subjective” meant categories of weapons, artillery for example, and artillery ammunition, small arms, and combat vehicles. The board of officers he had appointed in 1920 to study alternatives worked out the details of the organization charts only after careful consideration of the relative merits of other systems. The result was a division of responsibility by function only at the top level. This made three main units. Design and manufacture were assigned to one division, maintenance and distribution to another, while the general administrative work that implemented the other two fell to the third. Within the two operating divisions, lines of responsibility were drawn “vertically” according to type of commodity, a subjective or product system.4

Administration was assigned to a General Office, and for a time to an Administration Division as well, which handled fiscal and legal matters for the whole Department, hired and trained civilian employees, supervised military training and personnel, and maintained records. Indicative of the new postwar awareness of problems of industrial mobilization, a War Planning unit was always included as one subdivision of the General Office. Though the Ordnance district offices, re-established in 1922, undertook some local planning, most administrative business of the Department between 1920 and 1940 was concentrated in Washington under the immediate eye of the Chief of Ordnance and his staff.

To the three main divisions of the Department, the Chief of Ordnance added a staff group to serve as general liaison on technical questions. The Technical Staff was composed of officers and civilians, each a specialist in a particular field of ordnance design or manufacture—field artillery, coast artillery, ammunition, small arms, tank and automotive equipment, or air ordnance. Primarily advisory, the Technical Staff was charged with the responsibility “to keep informed of the trend and progress of ordnance development at home and abroad,” and, in keeping with this assignment, to act as a clearing house for information on technical engineering problems and to build up a technical library in the Ordnance Office.5 Members of the Technical Staff did not themselves do the creative design work at the drawing boards and in the shops where pilot models were built. This was the function of the engineers of Manufacturing Service. But the Technical Staff was authorized to recommend research projects and to pass upon designs of the Manufacturing Service engineers.

Advisory to the chief of the Technical Staff was an Ordnance Committee. Creation of this committee marked a true innovation, for it included representatives of the using arms and services. It was the successor to the Ordnance Board of prewar days but was expressly aimed at giving “the line of the army a greater influence over the design and development of Ordnance than it ever possessed in the past. ...”6 The chief of the Technical Staff explained: “The line members of the Ordnance Committee will, therefore, be

intimately concerned in establishing the type to be developed, in passing upon and approving the preliminary studies and the final drawings thereof and, lastly, in making and witnessing the actual test of the material and passing final judgment upon its satisfactoriness for use by the service.”7 Not until General George C. Marshall became Chief of Staff in 1939 did higher authority insist upon reviewing proposed military characteristics. Thus, for twenty years it was the Ordnance Committee that put the formal seal of approval upon specifications and designs after satisfactory trials of pilot models were completed, and who, after service tests, issued the minutes that in effect standardized or rendered obsolete each item of ordnance. As final approval of the General Staff and Secretary of War on matters of standardization soon became practically automatic, Ordnance Committee minutes in time constituted the orthodox “Bible of Ordnance.” From the committee stemmed the Book of Standards, Ordnance Department—the listing of equipment, type by type and model by model, accepted for issue to troops.8

On the operating level, responsibility was divided between the Manufacturing Service and the Field Service. The Manufacturing Service designed, developed, produced or procured, and inspected all matériel and ran the manufacturing arsenals and acceptance proving grounds. The tests of experimental models, usually held at Aberdeen Proving Ground, were conducted by Manufacturing Service engineers, although the Technical Staff was in charge and prepared the formal reports of tests. When the district offices were reconstituted in 1922, Manufacturing Service directed their activities also. Within the Manufacturing Service, the breakdown of duties of lower echelons was by commodity—ammunition, artillery, aircraft armament, and small arms. Field Service had charge of all storage depots, maintenance and issue of equipment to troops, and all salvage operations. With the appearance of the more detailed organization orders of 1931, Field Service was assigned preparation of standard nomenclature lists, technical regulations, firing tables, and the tables of organization and basic allowances whereby distribution of Ordnance supplies was to be made. Field Service, like Manufacturing Service, set up separate operating units, during most of the period before 1940 consisting of four divisions, Executive, General Supply, Ammunition, and Maintenance. Although there was some shifting of particular duties from one major division of the Ordnance Department to another and some redistribution of tasks and titles within a division, this general pattern remained intact for twenty years. It was endorsed by the General Staff after a thorough survey of the Department in 1929.9

The orders of 1931 made more explicit allocation of duties in the Office, Chief of Ordnance, than had earlier organization orders. Issued shortly before the announcement of the first War Department Industrial Mobilization Plan, the new organization was “intended basically for either peace or war,” a scheme that would enable changes in time of emergency to be confined to expansion by elevating branches to sections and sections to divisions.10 The only significant change was the assignment to Field Service of responsibility for depots attached to arsenals and for Ordnance sections of Army general depots.

Revision in the summer of 1939 in turn reflected the reviving importance of the Ordnance Department, as the Congress, viewing the troubled world situation, appropriated money for educational orders and over-all Army expansion. While the 1939 organization plan of the Department was in essentials identical with the earlier, the order clearly specified new lines of activity. For example, the Technical Staff was charged with arranging to furnish qualified men to represent Ordnance on the technical committees of other branches of the War Department and was to review technical and training regulations, supervise training of Reserve officers assigned to Technical Staff work, and pass upon requests for loans and sales under the American Designers Act and upon applications for patents to determine their status regarding military secrecy. In the Industrial Service, as the Manufacturing Service was relabeled in 1938, a new Procurement Planning Division was created to expedite execution of educational orders placed with commercial producers and to prepare the path for greater cooperation with private industry. Training of Reserve officers here was also specifically directed. Field Service similarly added a unit, a War Plans and Training Division, and was instructed to so organize its General Supply Division that it could handle sales to foreign governments and other authorized purchasers.11 In almost every particular the new enumeration of duties bespoke a comprehension of emergency needs, though war in Europe had not yet broken out. As far as paper organization went, the Office of the Chief of Ordnance had girded its loins in advance.

The arsenals, manufacturing installations long antedating World War I, were not profoundly affected by reassignments of responsibility in Washington. At the head of each arsenal was an officer of the Department who combined the roles of commanding officer of the installation as a military post and manager of a large industrial plant. His dual position was a small-scale replica of that of the Chief of Ordnance in relation to the Army as a whole. The commanding officers of the arsenals were allowed small staffs of lower ranking officers, in the lean days of the mid-twenties about four each, later seven or eight. One officer was usually assigned to the arsenal experimental unit, one as Works Manager or Production Manager, and one to head the Field Service depot after the Field Service installation at the arsenal was set up separately. Most of the administrative personnel and all the production workers in the shops were civilian. Many of them were Civil Service career men with long years of arsenal service; it was not unusual to find foremen who had been employees at one arsenal for thirty or forty years. These men supplied the continuity in operations that the officers, transferred after, at most, a four-year tour

of duty at any one station, could not give. The old-timers, possessed of the know-how of ordnance manufacture, were the men who perpetuated the art. Though this superimposition of a perpetual succession of relatively inexperienced officers upon civilian administrators and workmen long expert in their own fields might appear to presage conflict, relations between the military and civilians in the peace years were as a rule easy to the point of cordiality.

Design or redesign of any piece of equipment might be undertaken by engineers in the Office, Chief of Ordnance, in Washington or might be assigned to men at one of the arsenals. Before 1940, regardless of the birthplace of a design, the first pilot was always built at an arsenal. The arsenal chosen depended on the article, since the postwar reorganization allotted each establishment particular items for which it alone had “technical responsibility.” Thus, one or another of the six manufacturing arsenals filed and kept up to date the drawings and specifications for every article made or purchased by the Department, Rock Island, for example, assembled and kept all data on the manufacture of tanks; Frankford the drawings and specifications on optical and fire control instruments; and Springfield Armory the data on rifles and aircraft armament.12 No two arsenals necessarily had the same internal organization at any given moment. The commanding officer could align his staff as he saw fit as long as the arsenal mission was achieved.13 Basic research laboratories were maintained at every arsenal save Springfield and Watervliet; every one had an experimental unit, whether within or outside an engineering department, and each had its shops and its administrative division. When arsenal employees numbered only a few hundred, arsenal organization was simple; it was elaborated somewhat when, toward the end of the thirties, activity increased. War planning sections were established in 1935 and charged with maintaining liaison with district offices and with commercial producers who had to be furnished blueprints and descriptions of processes of manufacture of the weapons or parts they might contract to make.14 Training inspectors for accepting the products of contracting firms was always an arsenal duty.

After the Armistice the district offices were closed one after the other, as contracts were terminated and salvage operations neared completion, until only Chicago and Philadelphia survived.15 When surplus matériel, raw materials, and machine tools still undisposed of had been turned over to the arsenals or field depots, no function appeared to remain for procurement districts. But by 1922 War Department stress on planning industrial mobilization pointed to the wisdom of recreating a skeleton organization of district offices. Establishing these offices in peacetime to prepare for wartime procurement was a totally new departure. It showed how fully the War Department had learned that ordnance manufacture demands a skill not to be acquired overnight. Thirteen districts were formed covering the same areas as in the war, except that a San Francisco office was split off from the St. Louis District. Like the arsenals, the districts were a responsibility of the

Manufacturing Service. The civilian district chiefs were leading businessmen familiar with the industrial facilities of their regions. Each was assigned a Regular Army officer as an assistant and each had a clerk. Before 1939 this was the whole staff. The chiefs assembled records of companies’ war performance, made surveys of potential ordnance manufacturing capacity, and kept alive in their districts some understanding of Ordnance procurement problems. The value of the districts lay less in what they accomplished during the peace years than in their maintaining in standby condition the administrative machinery for procurement.16 Meanwhile, probably the best public relations device of these years in nourishing the interest of American industry in Ordnance manufacture was the Army Ordnance Association, founded in 1920, together with its magazine, Army Ordnance.

Apart from the proving grounds, manufacturing arsenals, loading plants, and district offices, all field installations were the responsibility of Field Service. This new postwar service found itself obliged to organize and expand simultaneously. Manifestly, the handful of depots and repair arsenals that had existed before 1917 were totally insufficient to handle the storage and maintenance of the vast quantities of matériel accumulated at the end of the war. Nor did earlier experience offer any pattern of permanent organization and procedure. In September 1919 the Provisional Manual for Ordnance Field Service appeared, embodying the principles that had proved sound in overseas operations; upon this basis Field Service proceeded to organize the details of its work in this country.17 Meanwhile, though makeshift arrangements were necessary to provide temporary storage for the tons of matériel that had accumulated in the United States immediately after the Armistice and that were soon augmented by shipments of supplies returned from overseas, common sense dictated formulation of some settled policy on what stocks of munitions as well as what manufacturing facilities were to be maintained for the future. The reports of the so-called Munitions Board, appointed by the Chief of Ordnance in the summer of 1919 to wrestle with this problem, formed the basis upon which plans for storage and maintenance were built. Yet it is worth noting that the failure of the General Staff and the Secretary of War to act upon some of the board’s recommendations imposed upon the Ordnance Department obligation to store and maintain far larger quantities of munitions than the board believed could reasonably be marked as primary reserve. This reserve affected scheduling for the manufacture of new ammunition.18

The decision approved by the Secretary of War was to create a network of depots, some reserved for ammunition, the rest for other ordnance supplies. The five depots built during World War I along the Atlantic seaboard to serve as forwarding centers for overseas shipments were designated as

ammunition depots where 25 percent of the permanent reserve was to be stored. A new depot near Ogden, Utah, was to take 15 percent and one at Savanna, Illinois, the rest,19 Four establishments combined supply functions with repair work: Augusta Arsenal in Georgia, Benicia Arsenal in California, San Antonio Arsenal in Texas, and Raritan Arsenal built at Metuchen, New Jersey, during the war. The first three dated from before the Civil War and had long operated machine shops for overhaul, repair, and modification work. But differentiation between ammunition and general storage or repair depots was never complete. Raritan, after 1919 by far the largest of the Field Service depots, became not only an ammunition depot and a repair arsenal but also the seat of the Ordnance Enlisted Specialist School and, in 1921, the office responsible for publication of the standard nomenclature lists.

By 1923 the twenty-two storage depots that existed in 1920 had shrunk to six-teen—seven ammunition, two reserve, and seven general supply depots. These were Raritan Arsenal; Delaware General Ordnance Depot, located near Wilmington; Curtis Bay near Baltimore; Nansemond near Norfolk, Virginia; Charleston in South Carolina; Ogden; Savanna in Illinois; Augusta; Benicia; San Antonio; Rock Island; Wingate in New Mexico; Erie Proving Ground and Columbus General Supply Depot in Ohio; New Cumberland General Depot in Pennsylvania; and the Schenectady General Depot in New York State. General depots were those where more than one Army supply service maintained sections. Overseas, technically outside the command of the Chief of Ordnance, Field Service had three depots, in Hawaii, Panama, and the Philippines; and after 1923 the depots at the manufacturing arsenals were turned over to Field Service.20

Command of each of these installations was usually assigned to an Ordnance officer who reported to the Chief of Field Service in the Office, Chief of Ordnance, in Washington. As at the manufacturing arsenals, subordinate officers, enlisted men, and civilians made up the rosters, numbers depending on the size and complexity of operations at the depot. Ideal execution of the multiple functions of Ordnance depots—reception, classification, storage, inspection, maintenance, and issue—would have required more personnel than the Ordnance Department could muster through the peace years. But to Field Service was assigned the largest number of the Department’s military personnel. The value of the property to be accounted for was about $1,311,949,000 in the spring of 1921.21 Although in time this valuation dropped as ammunition stores deteriorated and weapons, even when serviceable, approached obsolescence, the property accountability of Field Service continued to be heavy. This routine accounting, the necessarily complicated perpetual check on inventories through the Ordnance Provision System, and the specialized nature of the matériel repair and maintenance work conducted at depots demanded trained men. Hence, Field Service was at first charged with training all Ordnance troops except proving ground companies. While later the special

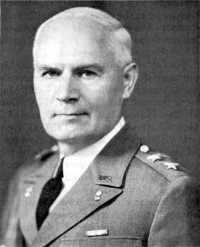

Maj. Gen. William H. Tschappat, Chief of Ordnance, 1934–38

service schools became the responsibility of the General Office of the Office, Chief of Ordnance, enlisted men gained practical experience in such essential operations as stock-record-keeping chiefly at Field Service depots.22

Storage depots were classified as reserve, intermediate, embarkation, area, and station storage. The first were what the name implied, depots for war reserve matériel; the second were for supplies to be issued in bulk to territorial commands and theatres of operations; embarkation storage depots were bases for overseas shipments; area storage for storage and issue within particular territorial commands; and station storage for items to be issued locally to troops at Army posts and camps. Ammunition depots, recognized as constituting a special problem, were organized differently. Classification of ammunition for storage was sixfold: finished ammunition and loaded components; smokeless powder; fuzes and primers; high explosives; sodium nitrate; and inert components such as empty shell, metallic components of fuzes, and also small arms ammunition. To safeguard against deterioration, careful provision was made for “surveillance” with a “Surveillance Inspector” responsible for periodic testing of explosives at each large ammunition depot.23 Maintenance of other matériel was a responsibility divided between repair arsenals servicing designated Army corps areas and the Ordnance officers assigned to the staff of each of the nine corps area commanders and commanders of foreign departments. The position and duties of officers responsible for maintenance of equipment in the hands of troops were analogous to those of Ordnance officers of armies operating in the field.24

The organization of the Ordnance Department during the “twenty-year Armistice” was thus orderly and well suited to the scale of operations the Department was allowed. Restriction to fewer than 270 officers before 1939 automatically limited what the Department could accomplish. That all gaps and overlappings of duties were not provided for was fully admitted. The Chief of Ordnance stated flatly in January 1931: “Whereas this order is intended to indicate division of responsibility and lines of authority within the Office, Chief of Ordnance, it is obvious that hard and fast lines cannot be drawn. Lapses and overlaps are bound to occur. With

Maj. Gen. Samuel Hof, Chief of Ordnance, 1930–34

this order as a guide, all are enjoined to cooperate in the effort to best perform the functions as a whole,”25 In the field installations, as in the Washington office, on the whole the machinery worked.

Four chiefs of Ordnance served the Department during the years between world wars: General Williams, 1918–30; Maj. Gen. Samuel Hof, 1930–34; Maj. Gen. William H. Tschappat, 1934–38; and Maj. Gen. Charles M. Wesson, 1938–42, General Williams, an officer whose conception of the Ordnance mission had been profoundly affected by his overseas service in 1917–18, combined open-mindedness with unusual administrative ability. His vigorous pursuit of the Westervelt Board recommendations on new equipment, his encouragement of industrial mobilization planning, and his judicious selection of officers to carry out these basic policies earned him universal respect. Department morale during his term of office was exceptionally high. His successor, General Hof, was handicapped by the curtailment of Ordnance funds, a result of the countrywide depression of the early thirties. Hof’s greatest contribution to the Department lay in preserving the gains it had already made. General Tschappat, known to his associates as the greatest ballistician of all time, was pre-eminently concerned with the scientific aspects of ordnance and, by his insistence upon the importance of this field, laid the groundwork for much of the later research and development program. General Wesson began his tour as chief shortly before the Congress and the American public discovered the necessity of extensive re-equipping of the Army. To this problem General Wesson dedicated his considerable experience. As a former assistant military attaché in London, for four years the chief of the Technical Staff in the office of the Chief of Ordnance, and for the next four years the commanding officer at Aberdeen Proving Ground, he had a wide knowledge of Ordnance matériel and Army needs. Methodically, and with unfaltering confidence in the ability of the Ordnance Department to meet the new demands, General Wesson laid and executed his plans for the war ahead.

The Budget

Ordnance Appropriations, 1919–37

In 1919 the Ordnance Department expected the Congress to cut its appropriations sharply, but it failed to envisage the extreme economy wave of the mid-twenties that reduced Ordnance funds far below even those of prewar years. No one

Table 1: Total appropriations for the Ordnance Department compared with total appropriations for the military activities of the War Department

| Fiscal Year | Ordnance | War Department | Percent |

| 1910 | $10,093,856.00 | $115,696,518,61 | 8.72 |

| 1911 | 9,210,554.60 | 109,971,367.17 | 8.37 |

| 1912 | 8,794,475.00 | 104,845,810.52 | 8.38 |

| 1913 | 9,001,733.30 | 115,561,920.10 | 7.78 |

| 1914 | 9,503,641.00 | 112,859,212.59 | 8.42 |

| 1915 | 12,353,432.00 | 125,514,560.95 | 9.84 |

| 1916 | 14,947,110.00 | 113,505,383.29 | 13.10 |

| 1920 | 20,805,634,79 | 813,304,262.20 | 2.55 |

| 1921 | 22,880,186.06 | 495,122,339.55 | 4.62 |

| 1922 | 13,425,960.00 | 373,019,831.22 | 3.59 |

| 1923 | 6,859,030.00 | 270,184,805.19 | 2.52 |

| 1924 | 5,812,180.00 | 256,669,118.00 | 2.26 |

| 1925 | 7,751,272.00 | 260,246,731,67 | 2,97 |

| 1926 | 7,543,802.00 | 260,757,250.00 | 2,89 |

| 1927 | 9,549,827.00 | 270,872,055.16 | 3,52 |

| 1928 | 12,179,856.00 | 300,781,710.93 | 4,04 |

| 1929 | 12,549,877,00 | 317,378,294.00 | 3,95 |

| 1930 | 11,858,981,00 | 331,748,443.50 | 3.57 |

| 1931 | 12,422,466.00 | 347,379,178.61 | 3.57 |

| 1932 | 11,121,567.00 | 335,505,965.00 | 3.31 |

| 1933 | 11,588,737.00 | 299,993,920.00 | 3.86 |

| 1934 | 7,048,455.00 | 277,126,281.00 | 2.54 |

| 1935 | 11,049,829,00 | 263,640,736.00 | 4.19 |

| 1936 | 17,110,301,00 | 312,235,811.00 | 5.47 |

| 1937* | 18,376,606,00 | 394,047,936.33 | 4.66 |

| 1938 | 24,949,075,00 | 415,508,009.94 | 6.00 |

| 1939 | 112,226,412.00 | 462,252,552.89 | 24,27 |

| 1940 | 176,546,788.00 | 813,816,590.74 | 21.69 |

* For the years 1937–40 the figures are those of the Ordnance Budget and Fiscal Branch.

Source: Ord Fiscal Bull 2, p. 30, NA.

could think the United States a militaristic country in 1910, yet the ten million dollars allotted for that year was nearly twice the figure for 1924. Ordnance appropriations for 1924 were set at $5,812,180. In the entire 1920–40 period this figure was the nadir not only absolutely but also relatively, as it constituted only 2,26 percent of the entire War Department appropriations, whereas the average from 1910 through 1915 had been 8.58 percent. Not until 1939 did the ratio again equal that of pre-World War I years,26 (See Table 1.) The cuts in appropriations precipitated a struggle to keep activities going at all. The reduction in funds was not paralleled by an appreciable sloughing off of Ordnance responsibilities at arsenals, depots, laboratories, and testing grounds, yet necessitated reduction of force, both military and civilian.

Heavy maintenance expenses obtained

through all these years, Col. David M. King, Ordnance Department, early explained the situation to a Congressional committee: “whether the Army is to have 175,000, 200,000 or 225,000 men has little to do with the size of the appropriation ‘Ordnance Service.’ The Ordnance Department has the enormous quantities of property to be guarded, protected, and cared for, regardless of any other consideration.”27 In 1920, 1,580 guards and firemen were required to protect the vastly increased postwar establishment and matériel, whereas 100 or less had sufficed before the war. Not only were labor and supplies more expensive, but plants and depots were more widely scattered, and often larger. In 1916, with only fourteen small plants, the Department had received $290,000 for repairs. In 1929 with twenty-four plants and ten times the capital investment, it got less than $800,000. The 1929 War Department survey recommended an immediate increase of over 50 percent “to preserve the Government property from serious deterioration.” And in a later paragraph the survey stated: “To carry out the mission of the Ordnance Department in accordance with programs approved by the War Department would require annual appropriations of $54,000,000.”28

In spite of the collapse of the stock market and the beginning of the countrywide depression, in the late twenties and early thirties appropriations picked up somewhat and in 1931 were over $12,000,000. Then, as the Congress realized the severity of the depression, it again cut Ordnance funds, for 1934 appropriating only $7,048,455. At this point only Navy orders placed with the Army Ordnance Department saved Watertown and Watervliet Arsenals from being closed down altogether. Had this occurred, it is doubtful whether they could have been resuscitated later. By 1936 at Watervliet Arsenal 85 percent of the year’s work was for the Navy and at Watertown more than half.29

Fortunately, the financial picture after 1932 was less somber than the official figures of Ordnance appropriations would suggest. The extensive emergency relief program that the Roosevelt administration launched in 1933 benefited the Department greatly. During the Hoover administration the Congress had set the precedent in the First Deficiency Act of 6 February 1931 by which Ordnance obtained a grant of $471,005 for repairs to arsenals. In 1934–35 relief funds for Ordnance purposes were sizable:30

| Procurement and preservation of ammunition | $ 6,000,000 |

| Procurement of motor vehicles | 1,163,200 |

| Procurement of machine guns | 349,204 |

| Seacoast defenses | 1,007,660 |

| Procurement of machinery for modernization | 2,309,491 |

| Repair and preservation of Ordnance matériel, storehouses, water mains, and roads at Rock Island | 370,000 |

| Repairs to buildings at Watertown Arsenal | 89,000 |

| TOTAL | $ 11,288,555 |

Table 2: Employees and Payroll at Springfield Armory

| Fiscal Year Ending 30 June | Civilian Employees Average for Year | Average Monthly Payroll |

| 1920 | 2, 451 | $331, 162 |

| 1921 | 1,000 | 154,509 |

| 1922 | 514 | 61, 903 |

| 1923 | 300 | 35, 176 |

| 1924 | 257 | 33, 365 |

| 1925 | 236 | 31,525 |

| 1926 | 253 | 34,385 |

| 1927 | 321 | 43,258 |

| 1928 | 353 | 47, 646 |

| 1929 | 427 | 57, 058 |

| 1930 | 471 | 63, 236 |

| 1931 | 478 | 63,498 |

| 1932 | 475 | 62,217 |

| 1933 | 466 | 61,130 |

| 1934 | 580 | 79,856 |

| 1935 | 966 | 115,565 |

| 1936 | 905 | 112,652 |

| 1937 | 930 | 115,817 |

| 1938 | 1,285 | 154,645 |

| 1939 | 1,594 | 192,140 |

| 1940 | 2,362 | 272,207 |

Source: Hist of Springfield Armory, Vol. II, OHF.

The total amount, spread over two years, roughly equaled normal appropriations for one year. The Roosevelt administration stressed projects that employed large numbers of men rather than expensive equipment, and much of the repair work at Ordnance installations fitted admirably into that category. From the Civil Works Administration, Ordnance received about $1,390,000, mostly for the pay of laborers to spray and paint buildings and to clean and reslush machinery. Though this labor force taken from the rolls of the unemployed was usually unaccustomed to Ordnance assignments and suffered many physical handicaps, it accomplished valuable work that must otherwise have been delayed or left undone.31

Every Ordnance establishment inevitably felt the pinch of economy, especially in the years from 1923 to 1936. At Springfield Armory, for example, the civilian staff of the Ordnance Laboratory in 1923 was cut from sixteen to four persons,32 and over-all cuts in personnel were proportionate, (See Table 2.) The story at Springfield was typical. At Watervliet when Lt. Col. William I. Westervelt assumed command on 31 May 1921 he supervised 550 employees; on 1 September 1923, the date of his transfer, only 220 employees. Under his successor, Col. Edwin D. Bricker, Watervliet touched a low of 198 employees.33 Secretary of War John W. Weeks in the fall of 1922 noted that on 1 January 1923 there would be a smaller force employed in the government arsenals than at any time in the previous twenty years.34 The close correlation between Ordnance appropriations and Ordnance payrolls meant that as funds in the mid-twenties dipped below the levels of the 1910–15 period, so also did total personnel.35

From 1919 on, the Chief of Ordnance, General Williams, protested vigorously against the small quota of officers allotted to the Department. He submitted in 1919 a figure of 494 officers as “a bona fide minimum estimate ... not subject to discount,” Instead, the Ordnance Department was allotted 258 officers, a number

Table 3: Ordnance Department Military and Civilian Strength: 1919–41

| Military Strength* | |||||

| Enlisted Personnel | |||||

| 30 June | Total Military | Officers | Total | Philippine Scouts | Civilians Employed |

| 1919 | 10,597 | 1,885 | 8,712 | 0 | † |

| 1920 | 4,081 | 368 | 3,713 | 0 | † |

| 1921 | 4,009 | 281 | 3,728 | 0 | 14,569 |

| 1922 | 3,087 | 288 | 2,799 | 0 | 8,119 |

| 1923 | 2,557 | 266 | 2,291 | 48 | 6,340 |

| 1924 | 2,747 | 248 | 2,499 | 0 | 4,561 |

| 1925 | 2,570 | 251 | 2,319 | 48 | 4,378 |

| 1926 | 2,571 | 267 | 2,304 | 49 | 4,754 |

| 1927 | 2,540 | 271 | 2,269 | 49 | 5,207 |

| 1928 | 2,665 | 271 | 2,394 | 48 | 5,899 |

| 1929 | 2,676 | 278 | 2,398 | 48 | 6,461 |

| 1930 | 2,576 | 277 | 2,299 | 49 | 6,852 |

| 1931 | 2,498 | 275 | 2,223 | 44 | 8,378 |

| 1932 | 2,500 | 271 | 2,229 | 49 | 7,707 |

| 1933 | 2,382 | 270 | 2,112 | 47 | 6,751 |

| 1934 | 2,348 | 271 | 2,077 | 45 | 8,986 |

| 1935 | 2,401 | 266 | 2,135 | 45 | 9,315 |

| 1936 | 2,631 | 269 | 2,362 | 47 | 10,005 |

| 1937 | 2,990 | 270 | 2,720 | 46 | 10,921 |

| 1938 | 3,040 | 269 | 2,771 | 47 | 12,656 |

| 1939 | 3,063 | 287 | 2,776 | 47 | 16,213 |

| 1940 | 4,330 | 334 | 3,996 | 46 | 27,088 |

| 1941 | 27,073 | 3,024 | 24,049 | 137 | 67,612 |

* Represents military personnel in all Army commands whose duty branch was reported as Ordnance Department; does not include personnel assigned to the Chief of Ordnance whose duty branch was reported as an arm or service other than Ordnance Department.

† Data not available.

Source: Stat Div, Office of Army Comptroller, 1949. Military: Ann Rpts SW. Civilian: 1921 from Special Rpt 158, 12 Nov 21, Stat Br, WDGS; 1922 from Regular Rpt 195, 10 Aug 22. Stat Br, WDGS; 1923 and 1924 from Special Rpt 182, 9 Oct 24, Stat Br, WDGS; 1925–38 from records of Civ Pers Div, Office Secy Army; 1939 from Special Rpt 264, 1 Dec 39, Stat Br, WDGS; 1940 and 1941 from tabulations in Stat Div, Office of Army Comptroller.

which General Williams considered entirely out of line with totals assigned to other departments. The average property responsibility per Ordnance officer, he pointed out, was some $7,000,000, far above that of officers in any other branch of the Army,36 Despite this plea, Ordnance officers on active duty as of 30 June 1921 numbered only 281, and even in 1939, a mere 287.37 (See Table 3.) What the figures do not reveal is the excessive reductions in rank and the stagnation in promotion that stemmed largely from the paring down of officer strength. In 1923 reductions for noncommissioned officers ran from 2.44 percent in one grade to 100 percent in

Table 4: Proposed ten-year ordnance program

| Weapon | Quantity | Units To Be Equipped | Cost | Ammunition for 1-year Period |

| Infantry | ||||

| Cal. .30 semiautomatic shoulder rifle | 2, 000 | 3 divisions | $1, 000, 000 | $168, 000 |

| Cal. .276 semiautomatic shoulder rifle | 2, 000 | 3 divisions | 1, 000, 000 | 200, 000 |

| 37-mm. infantry-accompanying gun | 22 | 1 division | 350, 000 | 16, 500 |

| 75-mm. infantry mortar | 24 | 1 division | 320, 000 | 100, 000 |

| Divisional | ||||

| 75-mm. pack howitzer | 48 | 2 regiments | 2, 000, 000 | 180, 000 |

| 75-mm. field gun | 24 | 1 regiment | 1, 300, 000 | 100, 000 |

| 105-mm. howitzer | 72 | 3 regiments | 4, 110, 000 | 390, 000 |

| Corps | ||||

| 4.7” gun | 24 | 1 regiment | 3, 285, 000 | 168, 000 |

| 155-mm. howitzer | 24 | 1 regiment | 3, 285, 000 | 150, 000 |

| Army | ||||

| 155-mm. gun | 16 | 2 battalions | 2, 920, 000 | 90, 000 |

| 8” howitzer | 16 | 2 battalions | 2, 920, 000 | 72, 000 |

| 8” railway matériel | 2 | * | 420, 000 | 10, 000 |

| tanks (23-ton, medium) | 64 | 4 companies | 5, 200, 000 | * |

| Antiaircraft | ||||

| Cal. .50 Browning machine gun | 1, 000 | * | 1, 400, 000 | 500, 000 |

| 37-mm. cannon | 200 | * | 1, 000, 000 | 650, 000 |

| 3” antiaircraft gun | 36 | 3 regiments | 1, 050, 000 | 225, 000 |

| 105-mm. antiaircraft gun | 20 | * | 800, 000 | 100, 000 |

| Aircraft | ||||

| Cal. .50 aircraft machine gun | continue as at present | * | covered | * |

| 37-mm. automatic gun | 50 | * | 250, 000 | |

| Bombs | continue as at present | * | covered | * |

| TOTAL | $32, 610, 000 | $3, 119, 500 | ||

| GRAND TOTAL | $35, 729, 500 | |||

* Unknown.

Source: Memo, CofOrd for ACofS G-4, 8 May 25, sub: Extended Service Test and Limited Rearmament with improved Types of Ordnance Weapons in the Next Ten-Year Period, 00400.11/51, NA.

another, action that seriously hurt morale.38 At no time did military personnel approach the figure of 350 officers and 4,500 enlisted men, set in the National Defense Act of 1920 as a reasonable peace-time level, or the recommendation of 373 officers in the War Department survey of 1929. Since of the small staff about 87 percent was assigned to the Field Service, the Chief of Ordnance had only some

35 officers for all other duties, except in so far as officers from other branches of the service were detailed to special Ordnance duty. This circumstance goes far to explain the Department’s inability to assign a number of officers as military observers abroad.39

Lack of money similarly limited planning and execution of plans. With the experience of World War Ito give perspective, the Ordnance Department in 1922 prepared a comprehensive munitions policy aimed at procuring for and supplying to the Army at all times munitions that would “at the minimum be equal in quality and quantity to those available to our enemy.” Achievement of this aim called for a development program, a reserve stock program, and a manufacturing, replacement, and rearmament program.40 Three days after its submission, the Ordnance statement of basic policy, with a few modifications, obtained the approval of General of the Armies John J. Pershing and the Secretary of War. The story of the rearmament plan will suffice to illustrate the effects of the budget cuts.

To implement the rearmament portion of the munitions policy, the Ordnance Department on 8 May 1925 submitted to the Secretary of War a detailed ten-year program of “Extended Service Test and Limited Rearmament.” (See Table 4.1 The program was critically studied by the Chief of Staff and the General Staff, and by the Cavalry, Coast Artillery, Air Service, Field Artillery, and Infantry. It received enthusiastic approval as a whole, though modifications and reductions were recommended. General Williams explained that unit cost for many of these items was high because, as they were new, the expense of dies, jigs, tools, and gages had to be added to the necessarily high cost of small-scale production.

The Ordnance limited rearmament program of 1925 thus proposed merely a modest scale of re-equipment for a part of the Regular Army. The Adjutant General informed the Chief of Ordnance that the program would be subject to annual revision, and, after lengthy study, the Secretary of War in April 1926 approved the plan with the proviso: “the extent to which it is carried out to be dependent upon funds appropriated for the purpose.41 But the moderate character of the program failed to protect it from large reductions. Cuts were made in nearly all items so that the $35,729,500 program of 1925 was scaled down to the $21,798,500 program of 1928.42 Unfortunately, and ironically, the maximum production was scheduled for 1932–36, with the peak in 1935. From the start, funds available remained below the amounts scheduled even in the reduced program. At the Congressional hearings in December 1928 for the fiscal year 1930, for example, General Williams stated that financial limitations had forced reductions of $500,000 in the 75-mm. and 105-mm. howitzer and 3-inch antiaircraft phases of the rearmament program.43

By June 1933, more than seven years after the ten-year program had been approved, Ordnance production of major artillery items stood as follows:44

| Item | Produced or Appropriated For | Ten-year Goal | Percentage Achieved |

| 75-mm. pack howitzer | 32 | 58 | 55 |

| 3-inch AA gun | 62 | 110 | 56 |

| 75-mm. mortar | 16 | 48 | 33 |

| 75-mm. field gun | 4 | 12 | 33 |

| 105-mm. howitzer | 14 | 48 | 29 |

| 155-mm. howitzer | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| 155-mm. gun | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| 8-inch howitzer | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| 8-inch railway gun | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 105-mm. AA gun | 0 | 20 | 0 |

In no category had progress been rapid, and in the larger caliber matériel, army, corps, and seacoast artillery, not a single weapon had been completed. Nor did items completed in the next few years brighten the picture. Only a few guns and mortars came off the production line at the arsenals and, apart from three 155-mm. guns, there was still no heavy artillery.45 Yet The Inspector General’s reports consistently commended the efficiency of the arsenals. By and large the program was too small to keep the arsenals busy, much less to give selected private firms production experience.46

Meanwhile, in line with a War Department attempt to integrate the numerous, and often overlapping, programs that had been started since the end of the war, the Ordnance Department submitted a rearmament and re-equipment program for the six-year period, 1935 through 1940. The objective was to equip the units involved in initial mobilization under the 1.933 mobilization plan,47 The original Ordnance six-year re-equipment program as submitted in 1932, although considerably revised later, offered an excellent picture of the most pressing needs of the Department in supplying the Army. The program called for only $1,400,000 yearly. For the six years the chief items, in order of cost, ranked: (1) antiaircraft guns, $1,240,800; (2) tanks, $1,000,000; (3) combat cars $837,000; (4) semiautomatic rifles, $900,000; (5) railway artillery, $610,000; and (6) antitank guns, $442,400. Yet budget cuts prevented full execution of these plans. For example, in estimates for the fiscal year 1938 under its re-equipment program the Ordnance Department asked for $7,849,536. G-4 reduced this to $5,395,363, and the Bureau of the Budget forced it down to about $5,000,000.48 The Ordnance Department did well when in any one year it could proceed at more than half the pace envisioned in the six-year program.

If the entire rearmament program had been carried out, by 30 June 1940 the results would have comprised: mechanizing one cavalry regiment, equipping the 1st Cavalry Division with standard armored cars, supplying active units of the Field Artillery with high-speed artillery, new or modernized, supplying antiaircraft units with standard matériel including fire

control, and the beginning of supply to the Infantry of new tanks, rifles, mortars, and guns. That would have been all.49

The consequences of the meagre appropriations year after year, limiting operations and narrowing down planning to the conceivably attainable, are so clear in retrospect that the layman must wonder whether the Ordnance Department could not have staged a successful fight for more money. Could the Chief of Ordnance not have persuaded the General Staff to allot to him a larger share of the War Department budget? Or, failing that, could he not enter a special plea for urgent projects when he appeared at hearings of the House Appropriations Committee? To the second question the answer is an emphatic no. The budget law of 1924 expressly prohibited any government official from appealing to the Congress for more money than the President’s budget had allotted his department, and Army officers were further bound by military discipline to accept the decision of the Commander in Chief, once it had been formulated.50 The most a service chief dared hope to accomplish before the Congress was to present his needs so convincingly that the Appropriations Committee would not slice his part of the budget. The answer to the first question, on the other hand, might theoretically be yes. It was always possible for the Chief of Ordnance to protest to the General Staff any proposed budget cuts before G-4 approved them. But each service had to compete with every other for its share. The War Department had to consider the Army as a whole, and the supply branches were not likely to get special favors. Still, protocol permitted each chief to convince the General Staff, if he could, that the needs of his service exceeded those of any other, and Ordnance representatives frequently tried their powers of persuasion. But skillful salesmanship, Ordnance officers agree, was not a strong point in the Department during the twenties and thirties. Furthermore, military tradition precluded protracted argument with one’s superior officers. There was simply never enough money to go round. Each Chief of Ordnance in turn was obliged to accept his allowance and then stretch it as far as he could.

The Upturn, 1938–40

Fortunately, after 1935 Ordnance appropriations increased steadily. Up through fiscal year 1938 the gains were in line with those for the War Department as a whole. For the fiscal year 1939 the Ordnance Department’s share showed a pronounced proportional gain, from 6 percent of the War Department total of 1938 to 24 percent. The Ordnance appropriation for 1939 was 4,5 times that for 1938 and 16 times that for 1934. (See Table 1.) As the situation abroad darkened, President Roosevelt’s interest in the deficiencies of the armed forces grew. A special message to the Congress on 28 January 1938 asked for $16,880,000 for antiaircraft matériel, manufacture of gages, dies, and the like, and a start on making up the ammunition deficiency. The Congress promptly authorized this expenditure. The $112,226,412

available for Ordnance in that summer of 1938 permitted planning and operations on so enlarged a scale that an Assistant Chief of Ordnance later declared that for the Ordnance Department the war began in 1938.51

By October descriptions of conditions in Europe, particularly information brought back by William C. Bullitt, US Ambassador to France, so alarmed the President that he called for immediate reports on what was most needed to strengthen the Army,52 The Chief of Ordnance on 20 October 1938 presented an itemized bill for $125,000,000 as the minimum price for meeting Ordnance deficiencies and, one day later, an estimate of $349,000,000 as the cost of matériel to equip a 4,000,000-man Army to be called up under the Protective Mobilization Plan.53 On 12 January 1939 President Roosevelt, armed with detailed figures, forcefully urged upon the Congress the appropriation of some $477,000,000, of which the Air Corps would get the largest amount, and the ground forces $110,000,000 for new equipment. In April the Congress passed the regular appropriation act granting the Ordnance Department $62,000,000. But the President’s plea for full rearmament asked for much more: the proposed bill gave Ordnance $55,366,362 in cash for expenditures for “Ordnance Service and Supplies, Army,” plus authorization to place contracts with commercial companies up to $44,000,000.54 The Second Deficiency Appropriation Act, when passed, carried the exact amounts requested. The general breakdown for Ordnance read:

| Project | Item | Amount |

| 4 | Renovation of ammunition. | $10,000,000 |

| 11 | Maintenance and overhaul of matériel in storage | 4,891,052 |

| 11 | Augmentation of stocks of ammunition | 37,506,505 |

| 11 | Augmentation of critical items of antiaircraft equipment | 7,581,500 |

| 11 | Augmentation of other critical ordnance items | 39,387,305 |

| Total | $99,366,362 |

“Other critical ordnance items” signified chiefly semiautomatic rifles, antitank guns, 60-mm. and 81-mm. mortars, ground machine guns, trucks, tanks, 8-inch railway artillery guns, 155-mm. howitzers, and modernization of 75-mm, guns.55 “Critical” items were defined as those essential to effective combat but for which the maximum procurement rate fell short of war requirements,56 These appropriations, Ordnance officers declared, would enable industry to get ready for production and be somewhat prepared in case of real emergency. On 1 July 1939 another $11,500,000 was appropriated for Ordnance. Thus, all together the Ordnance Department got $176,546,788 for the year ahead, $62,000,000 additional in May, and approximately $11,500,000 on 1 July.57 The total constituted a 58 percent increase over the appropriations for 1939. The lean years were over, but their legacy

was an accumulated deficiency of desperately needed matériel.

Industrial Mobilization Plans

One immediate consequence of the supply tangle of World War I was the War Department’s decision thenceforward to plan in advance. From 1920 on, industrial mobilization planning was a task to which the Ordnance Department gave constant thought. The planning involved two stages: preparation of cost estimates and schedules of items and quantities needed to fit the over-all Army mobilization plans; and plans for allocating manufacture of the matériel to commercial companies and government arsenals. The War Plans Staff in the Office, Chief of Ordnance, was in charge of the first, but the Manufacturing Division, because it supervised the district offices and the arsenals, had a large part in the second, the actual procurement planning. The considerable labor expended on both phases of planning was a clear reflection of the Ordnance Department’s conviction that careful preparation for industrial mobilization was essential if the disasters of supply in 1917–18 were not to be repeated.

Three steps taken in the first years after the war indicated the constructive thinking of Ordnance officers on this whole subject. The Ordnance Munitions Board reports, submitted in twenty-four separate papers between 1919 and 1921, mapped out an intelligent, comprehensive policy for keeping the United States Army equipped and industry prepared to meet military emergency demands. That higher authority disregarded many of these recommendations in no way invalidates their soundness, as later events proved.58 The second measure was the drafting of Section 5a of the National Defense Act of 1920. While this was the work of a number of men besides Ordnance officers, several high-ranking men in the Department played a considerable part in bringing about the creation of a War Department office specifically charged with responsibility for procurement and industrial mobilization planning.59 The third move was the founding of the Army Industrial College to which officers were assigned to study problems of industrial mobilization. This project, like the National Defense Act, was the fruit of many men’s efforts, but Ordnance officers conceived the idea and by skillful persuasion contributed to its realization.60 Through the years of discouragement that lay ahead, the Ordnance Department constantly worked at the problem of preparing the nation’s industry for the moment when the nation must rearm. Though, as World War II approached, Navy and Air Force priorities obliged the Department to recast some of its plans, Ordnance officers believed that their work had been sound and the surveys and production studies valuable.61 To understand the character of this work, review of Army mobilization planning and

brief examination of district procurement planning is necessary.

Early Mobilization Plans

Preparation of over-all Army mobilization plans was a nearly continuous process throughout the peace years. The blueprint for American rearmament—the elaborate Protective Mobilization Plan of the late 1930s—had its beginnings in the simpler plans of the early 1920s. When the National Defense Act of 1920 made the Assistant Secretary of War responsible for industrial mobilization planning and procurement, he organized his office to include a Planning Branch. This staff, together with the Army and Navy Munitions Board, was charged with coordinating Army and Navy procurement programs and exerted strong influence upon the Ordnance Department’s planning between world wars. For two decades these two groups, in the face of public indifference, struggled to devise comprehensive programs of industrial mobilization.

The 1920s saw the completion of several editions of mobilization plans. As soon as one version was finished, modification began, and usually within four years a new one appeared. The earlier plans, especially those of 1921 and 1922, tended to be chiefly munitions plans for the Army instead of all-around industrial mobilization plans.62 Ordnance experts who drafted the extensive Ordnance annex of the 1922 plan noted that the 1921 plans were absurd in that they set impossible requirements for Ordnance. The 1922 over-all Ordnance plan ran to about fifty mimeographed pages. In addition, the Ordnance unit in each corps area had branch plans, while Field Service and other divisions, as well as all field establishments, each had a unit plan prepared by the individual installation and submitted to the Chief of Ordnance for approval,63 In 1924 a new mobilization plan superseded the less detailed scheme of 1922. The Ordnance Department took its part in the planning with such seriousness that it ran an elaborate test on a mythical M Day to ascertain the quality of its plans. Analysis of this test revealed manifold complications and numerous deficiencies.64 By decision of the General Staff, the Army’s still more exhaustively detailed plan of 1928 was based entirely upon manpower potential, rather than upon reasonable procurement capacity. The result was a schedule of procurement objectives that the supply services considered impossible of attainment,65 The special survey of the Army made in 1929 called attention to several basic defects. One serious weakness was the failure to apply one of the fundamental lessons of World War I—that it takes at least a year longer to arm men for fighting than to mobilize and train them for actual combat. The survey stated: “... it will be noted that in all munition phases there is a wide gap between the exhaustion of the present reserve and the receipt of munition[s] from new production.”66 The Ordnance Department could not meet the requirements of the plan under its budgetary

limitations, and indeed as late as 1930 execution of the 1924 procurement program was still far behind schedule. Nevertheless, the 1928 plan for a four-field-army, 4,000,000-man mobilization formed the basis of all Ordnance computations of requirements right down to 1940. It constituted what Maj. Gen. Charles T. Harris, one of the key men of the Ordnance Manufacturing Service, called the “Position of Readiness Plan.” If goals set seemed in the thirties too unrealizable to achieve with funds that the Department dared hope for, at least Ordnance officers were ready with detailed estimates of quantities of each type of munitions needed and a planned procedure for getting them.67

The over-all Army and Ordnance mobilization planning of the twenties, defects notwithstanding, marked a great forward step simply because it was the first extensive peacetime planning the United States had ever undertaken. It was experimental and flexible. The plans, although not considered secret in broad outlines, were shielded from public view because the War Department feared an unfavorable public reaction. Probably the chief drawback of the top-level planning effort was its superficial, generalized nature. It failed to envision the extreme complexity and the enormous scale of operations another war would entail.68

The 1930s saw a pronounced broadening of perspective in mobilization planning. In part this was brought about by the work of the War Policies Commission, a body created by the Congress to consider how best “to promote peace and to equalize the burdens and to minimize the profits of war.”69 The commission, composed of six cabinet officers and eight congressmen, made a painstaking survey and submitted reports in December 1931 and March 1932. It pronounced the Army procurement program excellent and recommended Congressional review of the plans every two years. The Congress took no action.70

While earlier plans had been confined to a narrowly interpreted scheme for producing munitions, a plan worked out in 1930–31 dealt with the problem of over-all mobilization of national industry. This took a new approach based on the premise that Army procurement plans could not be made workable unless the entire economy of the nation was subject to governmental controls.71 A revision in 1933 made more explicit provision for these controls and for administrative organization.72 But in the Ordnance Department the 1933 plan was not popular because it called for equipping a large force faster than Ordnance could possibly effect it, particularly in view of the fact that most of the World War I stocks of matériel by then were obsolete and approaching uselessness. If troops were supplied at the rate at which they were called up, the heaviest procurement load would come in the first few months and then taper off—obviously an impossible arrangement. A revision of 1936, primarily important because issued jointly by the Army and Navy, took a somewhat wider view of the problems of

mobilization.73 In the next two years study of British industrial mobilization procedures produced a series of informing articles in Army Ordnance,74 but public interest in preparedness remained almost nil. The Neutrality Act had become law in 1935, the Nye Committee investigations were pillorying Army officers advocating any planning for war, and a series of magazine articles and books, under suggestive titles such as The Merchants of Death, were fanning public hostility to such measures. The Congress before 1938 made no move to legislate for industrial mobilization.

The Protective Mobilization Plan

In spite of public opposition to any preparations for war, in 1937 the Protective Mobilization Plan was born. The 1938 annual report of the Secretary of War, Harry H. Woodring, describes its genesis:

During my tenure of office as Assistant Secretary of War from 1933 to 1936 I became convinced that the then current War Department plan for mobilization in the event of major emergency contained discrepancies between the programs for procurement of personnel and procurement of supplies which were so incompatible that the plan would prove ineffective in war time. ... It became evident to me that the War Department mobilization plan then current was gravely defective in that supplies required during the first months of a major war could not be procured from industry in sufficient quantities to meet the requirements of the mobilization program. ... My conviction of the inadequacy of the initial plan from the supply procurement standpoint was so strong that one of the first directives issued by me as Secretary of War was that the General Staff restudy the whole intricate problem of emergency mobilization with a view to complete replacement of the then current War Department mobilization plan. ... The result of that study is now found in what we term the protective mobilization plan of 1937. The 1937 plan has not been perfected; details remain to be worked out and are being worked out thoroughly and diligently. But we have every reason to believe that the protective mobilization plan is feasible and will meet our national defense requirements.75

The name Protective Mobilization Plan, usually abbreviated to PMP, was designed to reassure the average American. The plan underwent steady amplification and refinement for the next two years.76 Unlike its forerunners, it set only attainable goals for the Ordnance Department. It called for an Initial Protective Force of 400,000 men within three months after mobilization, far fewer than demanded in earlier plans; eight months after M Day, 800,000 men were to be ready for combat, and in one year, 1,000,000 men. The maximum-size Army envisioned was 3,750,000 men. Ordnance leaders felt reasonably confident that the Department could equip the new quotas on time.77

From mid-1937 on, Ordnance plans in large part revolved around the PMP. Endless computations and recomputations were requested by the Secretary of War,

the Assistant Secretary of War, and the General Staff.78 Calculation of war reserves, for example, in August 1937 resulted in scheduling expenditures of funds by priorities up to $50,000,000.79 When the worsening international situation led President Roosevelt in October 1938 to confer with his top military advisers on stepping up defense expenditures, the Deputy Chief of Staff asked the Chief of Ordnance to prepare a program to plug the biggest holes in Ordnance supply. Twenty-four hours later General Wesson turned in an estimate of $125,000,000, an amount that would “supply the deficiencies in essential equipment required for the Initial Protective Force.” Only the existence of plans already well worked out under the PMP enabled the Department to complete a tabulation so speedily. One day later, 21 October, following a telephone conversation with G-4, General Wesson submitted a supplemental plan calling for $349,000,000 to meet the additional requirements for the PMP as a whole, in contrast to coverage of the Initial Protective Force only.80 A conviction that the White House mood favored a bold program, plus the readiness of the Department’s plans, help explain this move. Actually the translation of such a program into action had to wait many months till more decisive events abroad crystallized American public opinion in favor of large expenditures for arms.

Just before the outbreak of war in Europe, the Office of the Assistant Secretary of War requested the Chief of Ordnance to provide in forty-eight hours a detailed outline of Ordnance action in case of war in Europe. The reply listed funds needed under three headings: those to equip completely the forces under PMP, those for PMP requirements with augmentation for one year, and those for PMP requirements with augmentation for two years,81 Soon after, the Ordnance Department estimated the cost of the munitions procurement program under PMP augmented for two years to be $6,076,750,000 and declared that its computations were up to date for all items under PMP.82

The Ordnance sections of PMP were thus subjected to careful revision over a period of more than two years. The 132-page document, which became effective 30 November 1939, was entitled “Ordnance Protective Mobilization Plan, 1939.”83 Ordnance corps areas and field installations prepared their individual plans. All these were the bases upon which the Department built its program of preparation for war.

Procurement Planning

Procurement planning, the step that followed over-all industrial mobilization planning, was mapped out in the Office, Chief of Ordnance, but the arsenals and

the Ordnance districts supplied the data. The districts were re-established in 1922 for the express purpose of keeping contacts the country over with industrial concerns that might one day serve as sources of supply. A group of Ordnance officers had already evolved a careful scheme of procedures upon which district operations thereafter were based.84 While orders for matériel down into the late 1930s were scarcely enough to keep the government arsenals in operation, and contracts with commercial producers were rarely negotiated, every district office had the job of determining its area’s industrial potential for manufacture of each type of ordnance item. Analysis of this information from all the districts permitted the Manufacturing Division in Washington to allocate particular items to particular districts. Thereupon the district staffs made plant surveys. A complete survey called for a large amount of detailed information:

... the location, construction, and equipment of the plant; the availability of power, materials, and labor; the examination of the manufacturing processes involved to determine the readiness with which the facility can adapt itself to the proposed task of manufacture, and the extent to which variations from the Ordnance prescribed routine may be permitted; the new equipment and new construction which will be needed for conversion, the sources from which this equipment and the construction material must come, and the time within which they can be secured.85

With staffs of only three or four people through most of the peace years, district offices could not undertake any such thorough job. The partial surveys first completed merely produced lists of companies arranged according to the type of ordnance they were capable of manufacturing. The early industrial mobilization records in one district consisted of a few reference cards filed in shoe boxes. During the depression, economy necessitated abandoning even the yearly meetings of district chiefs. These were resumed in 1935. Over the years some districts succeeded better than others in keeping interest in planning alive, for some were able to enlist the cooperation of a greater number of Reserve officers. In this the New York District was particularly successful; every winter from 1923 on a group of Reserve officers met once a week with the district officials to discuss district problems, to hear lectures on Ordnance developments, and occasionally to rehearse the steps in negotiating contracts. Where district officers had less help of this sort, keeping in readiness the machinery for large-scale procurement was more difficult, but all districts maintained some activity.86

In spite of meagre budgets and limited personnel, the districts succeeded from time to time in obtaining from manufacturers gentlemen’s agreements, known as Accepted Schedules of Production, which specified quantities and rates of future war production. Upon request, the Assistant Secretary of War then allocated their plants to Ordnance. This arrangement was designed to eliminate competition among the Army and Navy supply services for particular facilities. By 1937 the districts had in hand some 2,500 accepted schedules representing 645 different commercial facilities. When any company had thus pledged itself to ordnance

manufacture in case of emergency, the district executive assistant worked out with the management fairly detailed production plans—plant layouts, machine tool requirements, gages, raw materials, power and manpower needs to convert rapidly to manufacture of the unfamiliar Ordnance item. The government arsenals’ blueprints and data on production methods were always available for this purpose. Ordnance officers regarded these as manufacturing aids, not mandatory instructions.87 In view of public apathy and industrialists’ reluctance to be involved in government munitions making, it is hard to see what more the Ordnance Department could have done in these years toward planning procurement from private companies.

Special mention must be made of the machine tool surveys. Though neither the Ordnance districts nor the Office, Chief of Ordnance, conducted these alone, their participation was of importance. The over-all studies were the responsibility of the Assistant Secretary of War; the Army and Navy Munitions Board also played a part. The urgency of having an adequate supply of machine tools suitable for munitions manufacture was well understood, but the problems involved were as complex as they were vital. The industry was always relatively small and except in boom periods operated below capacity. From the mid-thirties on, through a special committee of the National Machine Tool Builders Association, the industry cooperated with the government in an effort to forestall the shortages a national emergency might bring. The questions were: What did the armed forces require? and then. Could the industry meet the requirements?88 In a computation of Army machine-tool requirements prepared in 1937, the needs of the Ordnance Department comprised a big percentage of the total. Out of 20,613 lathes needed for the whole Army, Ordnance required 16,220.89 In spite of efforts to anticipate these needs, 1939 and 1940 found machine-tool supply the principal bottleneck in the rearmament program. Indeed, to stretch the supply early in 1940 it became necessary to resurrect obsolete or incomplete machine tools from arsenal storehouses.90

In 1938 conditions in Europe brought an upward turn in district activities. In every district Army inspectors were appointed to inspect items under current commercial procurement, a scheme that was later of great help because it provided a nucleus of trained inspectors qualified to train others when war came, Col. A. B. Quinton, Jr., Chief of the District Control Division, was directed to conduct more extensive industrial surveys and, as soon as funds were available, to enlarge the district organizations.91 Louis Johnson, Assistant Secretary of War, in December 1938 at a conference of district chiefs, urged them to bring their surveys up to

date so that “you are familiar with every potential war-producing facility in your District.”92 The money was appropriated early in 1939. Accordingly, as soon as procurement planning engineers, more inspectors, and more clerks could be hired, district office personnel increased. The Pittsburgh District, which in 1930 had had only two full-time workers, by mid-1939 had twenty-three; Philadelphia jumped to fifty-one. Even teletype systems were installed that summer. To prepare for the “accelerated Procurement Planning Program” every district submitted lists of machine-tool shortages.93