Chapter 8: Wartime Organization and Procedures in Research and Development

It is easy even for participants in the military planning and labors of 1940 to forget the strains, the uncertainties, the hours of frustration, and the moments of despair that marked that summer. Feverish activity within the War Department accompanied anxiety born of the successes of the German armies. As money flowed out for rearming the United States, the Ordnance Department set itself vigorously to its task. Pressure eased slightly after the failure of the German blitz upon England, only to mount to a new height in the fall of 1941 as war in the Pacific loomed ever closer and Hitler’s subjugation of all continental Europe seemed imminent. When the disasters of late 1941 and 1942 occurred in the Pacific, grim determination lent new energy to officers responsible for replacing the lost equipment and supplying the Army with weapons more efficient than it had ever had before. The slowness of the build-up in 1943, the hopes for the invasion in mid-1944, the shock of the Ardennes offensive that December, and the ultimate triumph of 1945 formed a backdrop of emotional tension in the arena where the Ordnance Department played its part. The rest of this volume treats of Ordnance research and development work topic by topic, and thus sacrifices much of the drama inherent in the sweep of events. Though clarity has demanded a discussion based on particular aspects of technological problems, the reader must remember that work proceeded in an atmosphere darkening and lightening with the defeats and victories of Allied armies in the field.

Factors Immediately Conditioning Research and Development

Because the time necessary to evolve the complicated mechanisms of modern weapons from initial design to finished product is long, logic suggests that American soldiers must have fought World War II mostly with equipment developed before Pearl Harbor. Down into 1944 this was indeed the case. Yet before V-J Day arrived, American and Allied troops were using a number of weapons that in 1941 were scarcely more than vague ideas. While the truly revolutionizing new items such as the amphibious cargo and personnel carriers, the proximity fuzes, and the homing bombs were not conceived within the Ordnance Department, its staff

contributed such innovations as armor-piercing-incendiary ammunition, bazookas, and recoilless rifles. Equally essential to victory were the series of developments pushed to completion upon weapons and vehicles on which Ordnance technicians had worked for years—the 90-mm. antiaircraft and tank guns, the fire control devices, the aircraft cannon, the tanks. Altogether, some 1,200 new or vastly improved items containing thousands of components were designed and produced before midsummer 1945. The difficulties of achieving this feat bear review.

The first handicaps in this race against time were the late start and the necessity for haste. During the peace years money for Ordnance research and development had been little. The backlog of projects in 1940 was large. Yet in the summer of 1940 research and development work upon new Ordnance matériel had to be relegated to a secondary role because the urgency of getting equipment into the hands of troops was so great that quantity production of accepted items had to be the first task. Not until mid-1942 were experts of the Ordnance Department released to work solely upon design and development of new weapons.

Meanwhile, observation of combat in Europe and, later, actual fighting in the Pacific and North Africa revealed weaknesses and gaps in American equipment that added to the list of projects requiring investigation. Thereupon arose the problem of contriving a system of communication whereby Ordnance officers in the theatres could transmit quickly to research and development men in the zone of the interior the exact nature of the changes combat experience dictated. Establishing machinery to effect this took many months and was scarcely in operation until the spring of 1943. Only delegation of many research problems to other agencies enabled the Ordnance Department eventually to supply American and Allied forces with arms and ammunition as good as or superior to the enemy’s.

A third problem grew out of the climate and terrain to which fighting equipment was exposed. Corroding dampness, excessive heat, bitter cold, beach landings where stores were drenched in salt water, operations over coral reefs, desert sand, or precipitous mountain trails, through thick jungle or deep snows, all threatened to immobilize or seriously damage munitions. Prolonged, careful, and expensive experimentation was needed to find answers to these problems. Money had not been available in the twenties and thirties. Again the late start added to difficulties, although, in the absence of combat testing, some malfunctions could scarcely have been forestalled.

A final difficulty was the problem of designing matériel that could be mass produced by American industry from available materials. No item, regardless of its perfection of design, could be counted upon unless private companies could turn it out accurately and quickly. In spite of the efforts of the Ordnance districts in the 1930s to prepare manufacturers for munitions production, most firms in 1941 still lacked experience. Hence, simplicity of design was important. Machine-tool shortages also emphasized this need. Furthermore, private industry’s inexperience pointed to the wisdom of making as few changes in design as possible once contracts for manufacture had been let and production lines set up. It is true that in some instances success in devising a new piece of equipment depended upon the ability of manufacturers to make intricate

parts of extraordinary delicacy. Thus the proximity fuze was made possible by finding producers who could make tiny turbines and generators and miniature radio circuits of utmost exactness and make them by the hundred thousand. But in all cases the less complicated the design, the surer the Ordnance Department was of getting matériel fabricated to specification. Moreover, since adequate stock piles of strategic raw materials had not been accumulated in advance, or because sufficient quantities of the ideal material nowhere existed, development of ordnance was handicapped by the necessity of finding substitute materials—synthetic rubber, plastics, new alloy steels.1 Shortages of tin and copper launched the attempt to produce steel cartridge cases. Vehicles rode on synthetic tires. Rubber washers gave way to neoprene washers. Tank engines had to be adjusted to burn lower octane gasoline. Use of new materials required extensive preliminary research.2

In view of the baffling problems to be solved and the dearth of men qualified by scientific training and experience to deal with them, the success of the wartime research and development program stands as a triumph. It was a job demanding wide collaboration. President Roosevelt’s creation of the National Defense Research Committee—NDRC, for short—in June 1940 was an all-important step in aligning civilian scientists to share in the task. The Ordnance Department had opened negotiations some months earlier with the National Academy of Sciences to pursue a number of investigations too remote from the immediate urgent problems at hand to be handled by the overworked staff of the Ordnance Department itself. In October these projects, eighteen of them in the field of ammunition, were turned over to the NDRC. Other assignments followed. By thus enlisting leading civilian scientists to undertake most of the basic long-range research for the military, the United States escaped the consequences that Germany faced after 1942 when lack of coordination between projects, subordination of research and development to production, and the resulting recourse to stop-gap measures lost the German nation the fruits of its best scientific knowledge and potential.3

For the scientist, a sharp distinction exists between basic research, the seeking of new principles of broad application, and technical research, that is, the application of new knowledge or of previously existing knowledge to a specific new item. The role of research in most government enterprises is logically limited to the latter. Certainly the military departments of the United States Government have rarely been free to pursue basic research save in the realm of ballistics: their responsibility is to apply the broad findings of fundamental research to specific military problems. Even the MANHATTAN Project was, strictly speaking, concerned largely with technical research, for much of the basic research upon the feasibility of splitting the atom had preceded the study of using this force in a bomb. Thus, apart from the work of its Ballistic Research Laboratory, the Ordnance Department never deliberately engaged in basic research, though occasionally men at Watertown, Picatinny,

and Frankford Arsenals found themselves constrained to carry on fundamental investigations in such fields as metallurgy and explosives. The Ballistic Research Laboratory at Aberdeen Proving Ground was an exception to the rule because study of the behavior of projectiles inevitably involves exploration of physical and chemical reactions of a basic character, and because no civilian institution in America had ever interested itself in this field.

Even technical research, the next step, came to be too complex and time consuming for the Ordnance Department to handle unaided after 1940. Thereafter until the end of the war, the Army’s job on everything but ballistics was primarily one of development rather than of basic or technical research. The delegation of research problems to the National Defense Research Committee, to university scientists, research foundations, and industrial laboratories released the engineering talents of the Ordnance Department for the tasks of transforming laboratory innovations into equipment that could be mass produced. While there were exceptions, most Ordnance Department experimental work from 1940 through 1945 was concentrated upon design and development.

Only after technical research is far advanced can design begin. For design, the formulation of a pattern from which to build working models, is an engineering process entailing the calculation of stresses and tolerances, and the determination of the mechanical and chemical forces required and the strength of materials needed. From the designer’s hand come the blueprints and specifications from which test models are built. Development can proceed only when there is a model to work upon, inasmuch as development is concerned with making a design practical by testing, discovering deficiencies, and devising corrections. In producing new military equipment, development is quite as essential as research. It may in fact continue after an item is officially accepted for standardization, although minor improvements are frequently labeled modification rather than development. Changes in techniques of production aimed at increasing output, bettering quality, or cutting costs may result in slight modifications of design, changes usually effected by so-called production engineers. When shortages of strategic raw materials necessitate use of substitutes, other engineering changes are often required.

In all these creative processes many people are involved. Patents are still issued, to be sure, and titles to inventions are still vested in particular individuals who establish their claims to having introduced original features into a device or mechanism. Yet patent offices of every nation ordinarily recognize only a few features of a design as constituting a novel patentable contribution. Modern weapons are nearly universally the product not of one inventor, or even two or three collaborators but of innumerable people. The very source of the initial idea is frequently hard to ascertain and the number of contributors to its development tends to produce anonymity. When the Ordnance Department requested the National Defense Research Committee to undertake research upon any one of a series of problems, the NDRC in turn might delegate investigation of particular phases to scientists or several research groups at universities or foundations. The VT, or radio, fuze, for example, evolved from that kind of collaboration; at the request of the Navy, the NDRC and NDRC contractors worked out the basic electronic features,

Maj. Gen. Gladeon M. Barnes, chief of the Research and Development Service

ballisticians and fuze experts of the Ordnance Department supplied the guiding data to make the fuze workable in ammunition. Though the patent for torsion bar suspension for tanks reads in the name of General Barnes of the Ordnance Department, dozens of automotive engineers aided in the development. Consequently, the discussion of research and development in the pages that follow includes few individual names. Participation was so wide that rarely can individual credit be assigned fairly.

Evolution of Organized Research and Development

Whoever else falls into anonymity, Gladeon M. Barnes cannot. From 1938 to 1946, first as colonel, then as brigadier general, and finally as major general, he was a dominant figure in the Office, Chief of Ordnance, on research and development matters and made his influence strongly felt outside as well. As chief of the Technical Staff before 1940, he scrutinized every project proposed and followed progress on all approved. It was largely his decision that determined what research should be delegated to outside institutions. When in the summer of 1940 General Wesson transferred him to Industrial Service to direct production engineering, Colonel Barnes brought with him his organizing capacity and drive. Though the immediate problem then was to hurry through the blueprints and specifications on accepted matériel in order to get contractors started on production, Barnes’ vision of the role research and development should occupy never deserted him. As soon as production was well launched, his opportunity came. By the summer of 1942 ammunition plants were in operation, tanks were beginning to roll out of the Tank Arsenal in Detroit, guns and carriages were emerging from factories in a dozen states, and fire control instruments were in process. Even the newly invented bazooka and bazooka rockets were in production. Convinced, therefore, that the peak of the crisis of initiating manufacture was now passed, General Campbell, the new Chief of Ordnance, placed General Barnes in charge of a separate research and development unit, first called the Technical Division, later the Research and Development Division and still later the Research and Development Service.

Barnes was a skilled engineer, a graduate of the University of Michigan School of Engineering. He was a man of varied ordnance experience, an expert on artillery, sure of his own judgments. An

impassioned fighter for his own ideas, he was unwilling to sit by patiently to wait for his superiors to arrive at a vital decision affecting ordnance, and when necessary would take his argument directly to higher authority. When he believed that action was urgently needed, he took upon himself responsibility for starting work not yet officially authorized. His very inability to see any point of view but his own was in many ways an asset to the Ordnance Department at a time when swift action was imperative, though his opponents regarded his refusal to consider contrary opinion a very great weakness. He cut corners, set aside red tape, disregarded orthodox but delaying procedures. His admirers admit that he made mistakes, but they point out that he never pushed upon others blame for his own errors. On the other hand, just as he took all responsibility for mistakes, so, his critics aver, he took to himself credit for the solid work of his predecessors and of his subordinates. He believed an expanded Ordnance Department quite able to carry out a full research program without the intervention of any other agency except in so far as the Ordnance Department itself might contract for particular investigative work with industrial and university laboratories. In 1940 he appeared to question the value of a special committee of civilian scientists committed to the study of possible new weapons, but he was the man first chosen to serve as the War Department liaison officer with the National Defense Research Committee.4 It was convincing testimony to his competence. While many people found him lacking in warmth and devoid of personal magnetism, throughout the war his opinion carried as great weight with his adversaries as with his supporters on particular issues. His knowledge, his persistence, and his forcefulness combined to fit him for the many-faceted job of directing wartime research and development.

The earlier provisions for Ordnance research and development assigned planning to the Ordnance Committee,5 design to men in Industrial Service. The system was the outgrowth of General Williams’ determination after World War I to have the using arms initiate requests for matériel to meet their needs, specify the military characteristics they desired, and then test the models designers evolved. The onus of responsibility for deciding what was necessary was thus shifted from the Ordnance Department to the combat arms, themselves not always in full accord.6 Still, the arrangement was workable for many years largely because the Caliber Board had thoroughly mapped out so comprehensive a development program that a long series of projects stretched out before the Ordnance Department to pursue as time and money permitted. The Ordnance Committee with its representatives from the using arms and General Staff discussed, accepted, and rejected specific proposals, listened to reports upon progress, made recommendations to the General Staff for standardization, and finally recorded the formal action whereby a new item was adopted or an old one declared obsolete. The minutes of these meetings, the “OCM’s,” constituted a valuable source of information on the course of

development of each item. The supervising unit within the Ordnance Department was a group of trained engineers, the Technical Staff, headed by an experienced officer. As Colonel Barnes described it early in 1940: “The Technical Staff is … responsible for research and development programs and for the approval of basic drawings of new material. It carries out all functions in regard to research and development, except the execution of the work.”7 The exception was a big one. The work was done by men in Industrial Service in the Office, Chief of Ordnance, in Washington, at the arsenals, or at Aberdeen Proving Ground. Occasionally, as in the case of research on powder, a commercial company undertook some investigation. The Technical Staff was an advising and recording group, not in any real sense an operating unit. The operating group in Industrial Service, on the other hand, had little say about policy and program.

As long as Caliber Board projects were in advance of any nation’s accomplishments and as long as the tempo of development work was unhurried, the scheme sufficed. But it was ill-adapted to pushing through the kind of intensive study of alternatives together with the search for totally new scientific devices of war that events in 1939 and 1940 called for. Development work on existing models also suffered for want of a central head to coordinate it. Though in the summer of 1940 General Wesson felt obliged to refuse Colonel Barnes’ plea for a separate research and development division dedicated solely to these problems, his assignment of Barnes to an operating position in Industrial Service proved to be a beginning. In spite of the fact that his job was primarily concerned with production, Barnes encouraged orderly progress on development work and himself proposed new lines to follow. The nearly seventy projects that he listed in May 1940 as requiring immediate attention indicate his awareness of what needed to be done.8 Yet a year after he had taken charge of production engineering he protested the inadequacies of the organizational set-up:–

1. The duplication of effort involved in the design and development of Ordnance matériel lies between the Technical Staff and Industrial Service. Take for example, the usual way in which a new project is initiated. A memorandum is prepared in one of the divisions of the Industrial Service and sent through the office of the Assistant Chief of Industrial Service, Engineering to Technical Staff. Technical Staff personnel prepare the O.C.M. It becomes necessary for this second group of officers and civilians to acquaint themselves with this project, either through contact with the office of the Assistant Chief of Industrial Service for Engineering or with the divisions. Often it is necessary to have these O.C.M.’s rewritten as the writer did not quite understand the project. A duplication occurs after the design has been prepared by the initiating division since the drawings must be approved by both the office of Assistant Chief of Industrial Service for Engineering and Technical Staff. After the O.C.M. is approved it is forwarded by letter to The Adjutant General, and after the general design has been approved by Technical Staff its duties cease until the item is ready for test at Aberdeen Proving Ground.

2. Drawings, designs, contacts with industry, follow-up, and all other work connected with development is the responsibility of Industrial Service. Design work is executed in the Industrial Service in Washington, by commercial companies, at the various arsenals, or at the Proving Ground. Difficulties are now encountered due to lack of authority of the Industrial Service at the Proving Ground where the ballistic laboratory and

automotive design section have been built up. All other design sections and laboratories are under the control of the Industrial Service.9

The upshot was the abolition of the Technical Staff and the elimination of the duplicating efforts Barnes deplored but the continuation of research and development activities as an adjunct of production,10 Only the Ballistic Laboratory at Aberdeen Proving Ground functioned as a true research unit undistracted by the production problems of Industrial Service. Though the new arrangement was an improvement over the old, and though under both systems some very important work was accomplished, far more rapid progress was possible when research and development became an independent division. That had to wait until June 1942.

In keeping with the major branches of Industrial Service, General Barnes divided the duties of his staff along commodity lines, an organizational scheme that he adhered to both while he was within Industrial Service and after he became chief of a separate division. The principal categories of Ordnance matériel were always artillery, small arms, ammunition, and automotive equipment, but these were of course susceptible of combination and subdivision. Just as artillery and automotive design had at one time been combined in one working unit, so in 1940 aircraft armament was specifically included with artillery, while tank and combat vehicle development was put into a separate subdivision. Two years later aircraft armament development became so important that it was separated from artillery. As the Tank-Automotive Center had by that time been set up in Detroit and automotive design assigned there, a Tank and Automotive Development Liaison section was added to the Technical Division in Washington. Similarly, the rocket program, virtually in infancy in 1942, by 1944 had grown to proportions warranting a separate division for rocket development work. To care for the mechanics of administration of all the commodity groups, an executive office was always included in the organization.

A number of special tasks remained that fell clearly neither into any one of the commodity development spheres nor into the domain of administrative work. These were grouped, therefore, into a unit called, for want of a more comprehensively descriptive name, the Service Branch. After the summer of 1942 the Service Branch was responsible for liaison with other agencies dealing with technical developments, such as the NDRC and the National Inventors Council; it coordinated the work of the ordnance laboratories at the arsenals and issued the technical reports on their findings; it prepared and disseminated the progress reports consolidated from the monthly reports of each development branch; it formulated and supervised investigations and tests of materials to minimize use of strategic materials and revised specifications accordingly; it supervised the activities of the Ballistic Research Laboratory and acted as a clearing house on ballistic information for the using arms and services as well as for other parts of the Ordnance Department; and finally, through its Ordnance Intelligence unit it was responsible for analyzing features of foreign matériel by study of items sent to this country or described in reports from abroad, and then for preparing the

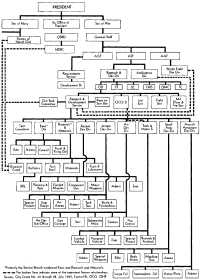

Chart 8: Organization of the research and development service: 1 July 1945

Research and Development Funds

| Appropriations | R&D Expenditures | ||||

| Fiscal Year | Total Ordnance | Research & Development | Total | Within Ordnance | Through Outside Agencies |

| 1941 | $3,023,913,998 | $6,173,000 | $6,162,000 | $2,494,785 | $3,667,215 |

| 1942 | 23,292,124,139 | 9,563,000 | 36,789,999 | 11,971,887 | 24,818,112 |

| 1943 | 9,948,319,237 | 46,419,000 | 46,667,499 | 9,021,732 | 37,645,767 |

| 1944 | 7,992,522,000 | 80,345,840 | 81,183,688 | 17,835,000 | 63,348,688 |

| 1945 | 9,384,694,008 | 45,950,000 | – | – | – |

Senate Subcommittee Rpt 5, 23 Jan 45, Pt. I., p. 309, 79th Cong, 1st Sess. The excess of expenditures over appropriations was made possible by authorizing transfers from other funds.

summaries and intelligence bulletins for distribution to other research and development groups to whom the analyses would be useful. The Service Branch thus touched every special field of research and development, sorting, sifting, channeling data, and making available to each group the pertinent information assembled by all the rest. Later some shifting of labels and reshuffling of duties took place, as when the Service Branch became the Research and Materials Division or when the technical reports unit, enlarged to include the technical reference unit, was switched to the Executive Division. But such changes, usually ordered with an eye to saving personnel, did not reduce the scope of the work to be done.11

The machinery for handling this heavy load of diverse responsibilities was well laid out on paper. Getting it to work depended on manning it. This was enormously difficult. As long as development work was carried on as part of the production process, General Barnes could use the experienced designers of the Industrial Service for such development work as time allowed. But their number was small, and when research and development were separated, Industrial Service pre-empted a good many. To recruit for the Technical Division men of the desired caliber who had more than general knowledge of ordnance was harder in 1942 than in 1940 and nearly impossible by 1944. For example, two branches of the division in November 1942 had 27 out of 72 authorized military assignments unfilled and 16 out of 45 professional civilian jobs in the Office, Chief of Ordnance, still vacant. Assignment of reserve officers with scientific training was one answer, but the supply of qualified men was limited at all times. In July 1945 the entire research and development staff in Washington numbered only 153 officers, 24 consultants, and 357 civilians of all grades.12

Money for salaries was no longer a stumbling block. Though after 1940 a greater proportion of funds than formerly was spent for laboratory facilities, materials, and contracts with outside research groups, appropriations for research and development were generous enough to

provide attractive salaries,13

In recruiting research and development personnel, some units fared better than others, the Ballistic Research Laboratory probably best of all. Col. Hermann H. Zornig, whose genius and foresight had largely created the laboratory in the late 1930s, had built well. As its first director he had started a program of vast importance. Consequently, because the laboratory was unique and could transfer no part of its duties to any other agency, Colonel Zornig was allowed to begin enlarging his staff early in 1940. A nonresident Scientific Advisory Council of eminent civilian scientists, appointed in July, interested a number of distinguished physicists and chemists in undertaking assignments at the Aberdeen laboratory. Oswald Veblen of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, Edwin Hubble of the Mount Wilson Observatory, Thomas H. Johnson of the Bartol Foundation, Joseph E. Mayer of Columbia University, Edward J. McShane of the University of Virginia, David L. Webster of Leland Stanford, and others placed the Ballistic Research Laboratory in a position to apply some of the best brains in the United States to basic and technical research problems. Civilian scientists conducted most of the research, though after Pearl Harbor they generally donned uniforms as reserve officers. In June 1941, upon Colonel Zornig’s transfer, Maj. Leslie E. Simon became director. Trained at the laboratory under Colonel Zornig, Major Simon carried on the program without any break. In addition to the staff at Aberdeen, a University of Pennsylvania Ballistic Research Laboratory Annex was set up in 1942 to handle some of the ballistic computations, especially those on which the University’s differential analyzer could be used. Altogether by mid-1944 the Aberdeen group numbered about 740, including professional people with very special qualifications, officers, Wacs, and enlisted men. All the enlisted men picked for work in the new supersonic wind tunnels laboratory had had earlier academic training in physics, chemistry, mathematics, or engineering.14

Relations with Civilian Agencies

The distinction of the staff at the Ballistic Research Laboratory, abbreviated to BRL, was an asset to the Ordnance Department in more ways than one. In addition to the effective work these men accomplished, their stature added prestige to the Ordnance Department in its dealings with civilian groups such as the NDRC. The top-ranking scientists of the academic world, in 1940 newly brought in on defense problems, not unnaturally tended at first to regard the military as men of action unsuited to cope with the intellectual problems of the research laboratory, but respect for the gifts of the officers at the BRL soon obliterated this condescension. In time, civilian employees of the Department’s research staff also came to be recognized as possessing the keen intelligence and intensive knowledge of the academic scientist; indeed, many of them had been recruited from universities and important industrial research foundations. Personality clashes, inevitable in any large group, gradually diminished.15

Purely professional differences of opinion about how to solve any given problem and

friction arising from uncertainties about where whose authority ended—uncertainties inherent in the somewhat vague organizational set-up of the NDRC in relation to the Army technical services—endured longer. Yet from start to finish relations between the Ordnance Department and the chiefs of divisions of the National Defense Research Committee, though not invariably cordial, produced useful collaboration. During the first months of NDRC’s life, official machinery for initiating an NDRC research project was slow moving: the technical services submitted projects to The Adjutant General for transmission to the NDRC “from time to time, as conditions warrant.” In November 1940 this procedure was simplified by having requests for NDRC help go through The Adjutant General to the War Department liaison officer to NDRC; this officer then arranged a conference between the technical service and the NDRC. But by late 1942 this procedure also proved needlessly roundabout. Thereafter the Ordnance Department, or any other technical service, drew up its request and hand-carried it to the War Department liaison officer, who in turn hand-carried it to the NDRC. In a matter of hours the appropriate subdivision of NDRC might have the research program launched. The Ordnance Department then assigned men from its own research and development staff, usually at least one officer and one civilian expert on each project, to serve as liaison with the NDRC.16

The investigations thus delegated almost always involved basic or prolonged technical research that the Ordnance Department was not at the time equipped to handle. A sampling of the more than two hundred projects the Department re quested the NDRC to undertake indicates their specialized nature: a basic study of detonations; the kinetics of nitration of toluene, xylene, benzene, and ethylbenzene; jet propulsion; special fuels for jet propulsion; determination of the most suitable normally invisible band of the spectrum for blackout lighting and methods of employing it in combat zones; problems involving deformation of metals in the range of plastic flow; phototheodolites for aerial position findings; the VT fuze; and gun erosion and hypervelocity studies.17

Occasionally the NDRC pursued projects along bypaths or into realms that the Ordnance Department felt itself better qualified to handle or considered untimely to have explored at that stage of the war. An attempt of a division of NDRC to participate actively in tank development elicited a sharp protest from a vice president of the Chrysler Corporation after a visit of the NDRC group to a Chrysler plant in Detroit. He declared that the group’s lack of familiarity with automotive engineering would involve a costly waste of the time of men who did understand its problems. Though one division of NDRC had pushed through design of the DUKW, the famous amphibian cargo carrier,18 and

could therefore claim some knowledge of automotive problems, the proposed tank project was canceled. The NDRC report later explained that progress had been blocked by “inability to secure the cooperation of the Chief of the US Ordnance Department and the automotive industry.”19

Over rocket development also there was some controversy. Though the conflict here was largely between two different schools of thought within the NDRC, and the Ordnance Department was involved chiefly as it had to support one or the other, the question of ultimate control of the rocket research program naturally cropped up. As interest in rocketry mounted, rivalry grew over who was to direct its course. General Barnes contended that all rocket development for the Army should be an Ordnance responsibility; though the Department should seek NDRC help in meeting Army needs, the NDRC, instead of plunging ahead on fruitless projects, should first “determine the military requirements of a device before proceeding with its development.”20 The Chief of Ordnance backed this view by recommending to the Army Service Forces that “all rocket activity” be coordinated through the Ordnance Technical Committee. The Ordnance Department won its point, but not until the summer of 1943 was satisfactory cooperation with the NDRC reached.21 While traces of competitiveness persisted, the general pattern resolved itself into an arrangement whereby the NDRC assumed leadership in one realm, the Ordnance Department in another. The acquisition of basic technical data pertaining to rockets and the making of prototypes of radically different rocket designs fell to the NDRC; the Ordnance department primarily carried out functions of engineering within the scope of at least partly known techniques, and of testing and removing “bugs” from development items, whether originated in the NDRC or in Ordnance.22

Suspicious of outsiders and overprotective of its own authority and prestige though the Ordnance Department may have been at times, its attitude toward the NDRC was nevertheless understandable. Ordnance research men were first and foremost engineers rather than pure scientists. Years of study of the practical engineering difficulties of designing military equipment gave them particular respect for the practical as opposed to the theoretical aspects of a problem. Long experience tended to make them impatient with any assumption that the academic scientist could readily master the engineering knowledge necessary to translate a principle into a usable instrument or weapon. Thus the Ordnance Department was reluctant to see the NDRC invade by ever so little the field of design. When the civilian research men were engaged upon highly technical investigations of physical and chemical phenomena applicable to ordnance, the Ordnance Department recognized their findings as invaluable; when they undertook work impinging upon engineering, the Ordnance Department became wary.

Furthermore, the research and development staff, bound by the Army tradition of not defending itself to the public, suffered from some criticisms it considered unjust. Accused by the NDRC of ignoring the potentialities of hypervelocity guns, Ordnance ballisticians explained that research had first to be directed at causes of gun barrel erosion and means of lengthening barrel serviceability, problems more immediately important and more quickly solvable. While NDRC men themselves soon discovered that erosion studies were an essential preliminary and involved exploration of a maze of possible causes, they deplored Ordnance postponement until January 1942 of a formal request for these studies. By then Ordnance technicians had already expended considerable effort on the study of a German tapered bore, high-velocity, light antitank gun and knew at first hand both the difficulties and the costs of barrel erosion.23 As development of the types of hypervelocity weapons upon which a division of the NDRC wanted to lavish energy must be a time-consuming undertaking, the Ordnance Department deliberately gave priority to the less spectacular allied projects. But when the NDRC successfully developed erosion-resistant stellite liners for .50-caliber machine gun barrels and a nitriding-chrome plating process for small arms bores, the Ordnance Department gratefully acknowledged its debt. It made immediate use of the exhaustive NDRC study of the mechanics of barrel erosion and acclaimed the sabot projectile for the 90-mm. gun and the experimental 57-40-mm. tapered bore gun evolved by the NDRC and its contractors.24 These achievements secured, Ordnance Research and Development Service was ready to encourage further work on hypervelocity guns. The end of the war halted the plan.25 Another criticism voiced by civilian scientists charged the Ordnance Department with failure to develop a recoilless gun.26 The highly successful 57-mm. and 75-mm. recoilless rifles used in the last months of war were in fact conceived, designed, tested, and developed by Ordnance men, virtually unaided. Statements belittling Ordnance research did not grease the wheels of Ordnance-NDRC machinery.

Relations with the NDRC were thus marked by occasional differences of opinion, flickers of mutual distrust and, after the war, some exasperation within the Ordnance Department at what its research staff felt to be NDRC’s tendency to claim credit for what the Ordnance Department had itself done. But it is easy to

exaggerate the importance of these difficulties. They rarely interfered with getting on with the job. The undercurrent of slight mutual distrust was never more than an undercurrent.27 As the war wore on and Army men saw the fruits of NDRC research, their attitudes underwent marked change. This shift was of utmost importance in determining the role of civilian scientists in the postwar organization of the Department of Defense.

The roots of the Ordnance Department’s initial distrust of the NDRC lay in the century-old conflict of military versus civilian. The Constitution vested control of the Army in civilian hands, in the President as Commander in Chief and the Secretary of War as his adviser. Beyond that the Army had always believed national defense should be controlled by the military; civilians should be used for particular jobs, but under the aegis of the War Department. To this system the Office of Scientific Research and Development, under which the NDRC operated after June 1941, could well be a threat. Just as Army control over design and manufacture of weapons had been challenged in the 1850s, might not the NDRC in the 1940s take unto itself the Army’s direction of military research and development? That many men of the NDRC thought civilian direction desirable there can be no doubt. The official history of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Dr. Baxter’s Scientists Against Time, implies this attitude. “The failure to make the most of our possibilities in high-velocity ordnance reveals inadequate civilian influence upon strategic thinking,” wrote Dr. Baxter after the war.28 He repeatedly hints at shortcomings of American ordnance that civilian supervision of research and development would have overcome.29

Throughout the war the Ordnance Department was strongly opposed to any such scheme. In explaining why Ordnance officers believed that neither the NDRC nor any other civilian agency should be allowed to govern Army research programs, General Barnes later stated:

No group of scientists no matter how wise could have undertaken this task with no preparation. It had taken years to train Ordnance officers to understand the meaning of Ordnance equipment in war. NDRC organized a number of very useful committees. However, their usefulness was handicapped by their lack of knowledge of the subject. They needed Ordnance leadership. From time to time we attempted to give them that leadership ... to tell them what was wanted. ... In my opinion, if through some political move NDRC had been given the Ordnance job the Allies would have lost the war.30

In 1942 General Williams, Chief of Ordnance from 1918 to 1930 and later War Department liaison officer to the NDRC, attempted to allay the anxiety shared by all the supply services:

The liaison between the Supply Bureaus of the War Department and the NDRC has not been as efficient as it should have been. One of the reasons for this was that there was no clear line of demarcation between the activities of the NDRC and those of the Bureaus. This led to a certain amount of confusion. Also there was a slight feeling of apprehension amongst the Bureaus because they feared they might lose some of their responsibilities and that these would be assumed by the NDRC. It seems to me that

these apprehensions are groundless because the NDRC is a temporary organization that in all probability will be dissolved shortly after the termination of the war. The duties and responsibilities of the Bureaus, as stated above, continue in peace as well as in war and are just as important in peace as they are in war.

Closer and more cordial relationship between the Bureaus and NDRC would be greatly to the benefit of the Bureaus.31

Gradually, Ordnance fears of the NDRC subsided, though the “clear line of demarcation” of authority was never officially drawn.

Nevertheless, uneasiness long remained lest some scientific super agency be created that would strip the technical services of their research and development functions. A proposal to create an agency coequal with, but independent of, Army, Navy, and Air Forces, to take charge of all national defense research work sounded particularly alarming.32 By comparison the Research Board for National Security, established in November 1944 as a subsidiary of the National Academy of Sciences, was innocuous since this board received its funds from the military. Not until the Secretaries of the Army and Navy set up the Joint Research and Development Board after the war to coordinate Army and Navy research programs, did Ordnance apprehensions disappear.33 Fifteen months later, in September 1947, the National Security Act of 1947 established within the Department of National Defense the Research and Development Board where civilians and military men shared authority.34 In 1940 the Ordnance Department would have considered such an arrangement unthinkable, but wartime cooperation with the NDRC left its mark.

With other civilian agencies engaged in munitions development during the war, the Ordnance Department had no altercation. The National Inventors Council frequently submitted new designs of weapons and proposals for innovations, but it served principally as an intermediary between the inventor and the Ordnance Department. Manned by a group of gifted people including a former Chief of Ordnance, Maj. Gen. William H. Tschappat, the council saved endless time for the military by screening the proffered ideas, winnowing the familiar and “crackpot” from those that had some promise. Even then the council in some months passed on to the Ordnance Department as many as a hundred “inventions” to study. Very few could be used, but the Department neither wished nor dared to toss aside any without careful examination.35 If the Ordnance Committee rejected the idea as impractical or as a duplication of an idea already recognized, there, without argument, the matter usually ended.

The Ordnance Department also dealt with a number of committees organized to advise on particular problems and with special groups within industry. Engineering advisory committees drawn from private industry had been an outgrowth of the early months of the rearmament program. In the fall of 1940, at the Ordnance Department’s request, twenty-nine distinct

groups had been organized, each of them as an engineering advisory committee on a particular type of ordnance—the tank committee, the gun forging committee, the bomb fuze committee, the pyrotechnics committee, the metallic belt link committee, and the like. The first purpose had been to give manufacturers who had little or no experience in making weapons opportunity to thrash out engineering problems with Ordnance officers and Ordnance engineers. After the first meetings, when by vote of the manufacturers’ representatives the committees were given a permanent basis, the discussions produced not only clarifications of existing procedures but also a number of sound ideas for improving designs and simplifying manufacturing methods. These engineering committees at the end of two years became “industry integration” committees, because engineering problems had largely been solved and pressure shifted to increasing production of matériel by the then well-established methods.

Another vital link between the research and development staff of the Ordnance Department and research groups of private industry was the series of research advisory committees. Some of these had existed for years. The Society of Automotive Engineers Ordnance Advisory Committee, for example, had done yeoman service during the 1930s by advising Ordnance engineers on suspension and transmission problems of tank design, The Committee on Petroleum Products and Lubricants gave the Ordnance Department the benefit of wide experience in that specialized field. Perhaps most useful of all, among a host of valuable contributions, was the work of the Ferrous Metallurgical Advisory Committee. Divided into eight subcommittees, its members represented more than two hundred individual companies commanding 85 percent of the steel capacity of the country. At frequent meetings of these men with Ordnance Department experts, research programs were initiated that later resulted in improved processes and conservation of critical alloys. Of the contributions of all these groups General Barnes enthusiastically noted: “Through these committees, the Ordnance Department has maintained close contact with industry and with the best scientific talent in the country and has obtained the cooperation and assistance of these groups in the solution of vital problems pertaining to Ordnance matériel.”36

Relations with Other Military Agencies

Relations of the Ordnance research and development staff with civilian scientists have been discussed at some length not only because the ultimate outcome was significant but also because it was achieved in the absence of established precedents. The National Research Council of World War I, intended to perform services like those of the NDRC, had been started too late, had had too nebulous authority, and had died too early to provide a pattern for collaboration in World War II.37 In the 1940s working procedures and mutual

responsibilities had to be evolved step by step. Ordnance relations with other segments of the Army, on the other hand, and with the Navy and the Air Forces, followed a relatively familiar pattern. To be sure, the creation of the Army Ground Forces and the Army Service Forces and later the creation of the New Developments Division of the General Staff introduced some new quirks, but controversy, when it occurred, was still a family quarrel to be fought out along well-known lines.

With the Navy, relations were almost invariably harmonious. Cooperation with the Bureau of Ordnance had had a long, untroubled history. Navy and Marine Corps representatives on the Ordnance Technical Committee effected constant liaison on development projects, and a steady exchange of formal and informal reports on work afoot enabled Army Ordnance and Navy to collaborate. Furthermore, after January 1943 high-ranking officers of both Army and Navy held several special conferences to discuss research and development problems common to both services.38 Division of labor in new fields of research was usually sufficiently defined to prevent duplication of effort. For example, while the Army Submarine Mine Depot was concerned with mines for harbor defense and the Naval Ordnance Laboratory with mines for offense in enemy waters, joint efforts went into developing ship detection devices for use in submarine mines for both purposes, and joint use of mine testing facilities ensued in taking underwater measurements. In the VT fuze program the Navy agreed to sponsor the development of projectile fuzes for both Army and Navy antiaircraft gun shells, the Army the development of fuzes for bombs and rockets for both services. Both services, as well as civilians, worked on adaptations for using the fuzes in other ground weapons.39

Collaboration with the Army Air Forces in developing air armament also was eased by years of close association. From 1922 to 1939 an Ordnance liaison officer had always served at Wright Field where Air Corps experimental work was centered. When in the summer of 1939 the aviation expansion program called for an extension of Ordnance work, Maj. Clyde Morgan of the Ordnance Department was assigned as chief of the Ordnance section of the Wright Field Matériel Division. Perpetuation of the division of responsibilities between the Air Corps and Ordnance Department as established in the 1920s made the Air Forces responsible for development of all matériel that was an integral part of the plane—the gun turrets, bomb shackles, and bomb sights—the Ordnance Department for the guns, the gun mounts, the bombs, and fire control mechanisms.40 Arguments inevitably occurred from time to time over such controversial matters as the advisability of wire-wrapping bombs or the efficiency of the 20-mm. aircraft cannon but, until development of guided missiles began, differences were minor.41

In the summer of 1944 Brig. Gen. Richard C. Coupland, the Ordnance officer assigned as liaison at Army Air Forces headquarters in Washington, urged that the Ordnance Department assume responsibility for development of all guided missiles, commenting that “projects of [this] type are running around loose and being furthered by anyone aggressive enough to take the ball and run.42 Air Forces and Ordnance Department, as well as the NDRC, had for months been pursuing investigations of this type of weapon, German use of “buzz bombs” and later of the deadly V-2 rockets, about which specialists in the United States already knew a good deal, sharpened awareness of the urgency for work in this field. The field was wide enough to be divided, but obviously the duplication of research or the withholding by one group of data useful to the other must stop.43 A conference of representatives of the Air Forces and of the New Developments Division of the General Staff in September cleared the air. A General Staff directive followed, charging the AAF with “development responsibility ... for all guided or homing missiles dropped or launched from aircraft , . . [or those] launched from the ground which depend for sustenance primarily on the lift of aerodynamic forces.” Army Service Forces—in effect, the Ordnance Department—was to develop missiles “which depend for sustenance primarily on momentum of the missile.44 Early in January 1945 the General Staff requested the Ordnance Department to attempt development of a missile suitable for antiaircraft use, though the Air Forces was also working on a ground-to-air missile.45 No obstructive competition between the services resulted.

With headquarters of the Army Service Forces, the Ordnance research and development staff faced some difficulties, particularly during ASF’s first year. The interposition of a new command between the operating divisions of the Ordnance Department and the policymakers of the General Staff and the Secretary of War’s office inevitably introduced new channels through which communications must go before decisions were reached and Ordnance requests approved.46 Since many ASF officers were unfamiliar with the peculiar problems of Ordnance research and development, Ordnance officers were frequently irked at the necessity of making time-consuming explanations to the ASF Development Branch of the whys and wherefores of Ordnance proposals. Nevertheless, as time went on, General Barnes’ staff found that watchfulness, plus patience in interpreting a problem to General Somervell’s headquarters, generally served to win ASF over. If General Barnes believed a specially important project likely to be side tracked, he bypassed routine channels and went directly to General Somervell, General Marshall, or even to the Secretary of War. Thus, in the face of AGF opposition, he persuaded General Somervell of the wisdom of proceeding with development of a heavy tank and got Mr. Stimson’s express approval for making the 155-mm. gun self-propelled by

mounting it on a medium tank chassis.47 Though the struggle during 1942 to get the highest priority for Ordnance development work was acute, and though later occasional controversies arose, such as those over limited procurement of the T24 light tank and over the heavy tank program, fairly amicable relations came to be the rule. The ASF Development Branch usually accepted the Ordnance Department’s judgment about the importance of individual projects and only disapproved a program when it appeared to mean the diversion of industrial facilities from other more pressing jobs. As long as ASF headquarters confined itself to staff jobs of coordination and eschewed what Ordnance officers regarded as operational activities, jurisdictional troubles scarcely existed.48

In spite of ASF coordinating efforts, from time to time friction developed between the Ordnance research staff and the Corps of Engineers and Signal Corps. With the Engineers the differences of opinion over weight and width of equipment in relation to bridge capacity were as old as tanks. The Engineers periodically protested acceptance of vehicles and self-propelled artillery that exceeded authorized limits by even a few inches or a few pounds, for road and bridge maintenance was difficult at best, and unloading tremendously heavy equipment from ships’ holds multiplied problems.49 However justified the Engineers’ objections to added weight and bulk, they were usually overridden. Assignment in 1944 to the Engineers of responsibility for all commercial tractors having top speeds of twelve miles or less per hour took out of the hands of the Ordnance Department control of some slow-moving artillery prime movers.50 With the Signal Corps some conflict was eventually inescapable because of the interrelatedness of electronics, VT fuzes, and fire control instruments using radar. The Ordnance Department disclaimed any wish to “enter the radar business,” as the Signal Corps charged, but believed that the Signal Corps should be used only as “an assisting agency” in all development work on fire control and guided missiles. That, in effect, was the ultimate decision reached jointly after V-E Day.51

When the Army Ground Forces was created, relations with the using arms were altered somewhat by the interposition of the AGF Requirements Section between the combat arms and the Ordnance Department. The advantages of the new arrangement were twofold: decisions were reached more quickly, and the requirements of one arm were reconciled with those of another. For example, instead of the Chief of Infantry and the Chief of

Cavalry independently submitting requests for new or improved equipment, to be used for the same general purpose but having slightly different features, the Developments Division of the AGF Requirements Section passed upon the need and prepared a single statement of the military characteristics deemed essential. As in the past, the request with all the pertinent details was then processed through the Ordnance Technical Committee to the appropriate section of the Ordnance research and development staff to act upon itself or to delegate to an outside agency. More often than in peacetime, the Ordnance Department also initiated projects through the Ordnance Technical Committee and submitted to the AGF models for comment and test.52 Particularly was this the case in developing tanks and self-propelled artillery. It was largely over these that conflicts between the Ordnance Department and AGF arose.

Pronounced differences of opinion about the tactical utility of heavy tanks had first been voiced in 1920 when “heavy” meant any tank weighing more than twenty-five tons.53 For the next twenty years lack of money as well as War Department disapproval prevented the Ordnance Department from pursuing work upon heavy tanks, but in 1940 and 1941 engineers of the Department’s automotive section succeeded in designing and building a sixty-ton model mounting in the turret a 3-inch gun and a 37-mm. gun. The tank was standardized in February 1942 as the M6. Notwithstanding this official approval, the AGF immediately objected. Further tests led the Armored Board to pronounce the M6 unreliable and much too heavy, and consequently procurement was limited to forty tanks. Not one was shipped overseas. Periodic Ordnance proposals to modify the M6 to eliminate its weaknesses never met with approval.54 But General Barnes was convinced that before the war was over the ground forces would need a heavy tank. He therefore set his arguments and plans in some detail before General Somervell, who concurred in Barnes’ proposal to develop a much more powerful tank than any the AGF was willing to adopt at that time.55

Fighting in North Africa, in the spring of 1943, was proving that American tanks must have greater fire power than the 37-mm. and 75-mm. guns on the Grants and Shermans could furnish. Though the Shermans, rushed to the British in the autumn of 1942, had helped to turn the tide at El Alamein, in the course of the winter the Germans’ increasing employment of long-barreled, high-velocity 75-mm, guns on Panzer IV tanks and the appearance of sixty-ton Tigers mounting 88-mm. guns gave Rommel’s troops an advantage. Nevertheless, the AGF was reluctant to accept heavy tanks carrying thicker protective armor plate and mounting bigger guns. The commanding general, Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair, doubtless fortified by the advice of officers in North Africa, clung to faith in the superiority of the more mobile, maneuverable medium tank. He demanded more powerful but not heavier guns and tanks; the greater weight of large-caliber guns tended to offset the advantage of the greater mass of the projectiles they fired. As muzzle velocity

usually decreases with increased caliber, unless the gun barrel be excessively long, it was axiomatic that the smallest caliber that could deliver a sufficiently effective projectile to destroy the target would be the best. The problem was to design a weapon in which the various factors were most effectively balanced. Use of high-velocity, tungsten-carbide-core, armor-piercing ammunition, known as HVAP, was a partial solution, and subcaliber projectiles with discarding sabot might have been another. The discarding sabot type of projectile was not adopted by AGF because of probable danger to the user.56 General McNair also disapproved mounting a 90-mm. gun in a medium tank.57 The M4 series of medium tanks, plus a suitable tank destroyer, would serve, he believed, to defeat German armor.58 Though advances in metallurgy by 1942 had enabled the Ordnance Department to build light but powerful 76-mm. and 90-mm. guns out of newly developed, thin, higher physical steel, Ordnance men were convinced that medium tanks, whether mounting 76-mm. guns or 105-mm. howitzers, must be supplemented by heavy tanks. The conflict of opinion, which was “fought out bitterly around 1943,” was actually three-sided, involving the Armored Force as well as AGF headquarters and the Ordnance Department.59

While General Barnes and his staff worked on a series of heavy models embodying the results of Ordnance experience, the Army Ground Forces early in 1944 undertook to draw up a lengthy list of specifications for a “general purpose” tank,60 These specifications the chief of the tank development unit at the Detroit Tank Arsenal later characterized as “amateurish.”61 The wanted combination of light ground pressure, high speed, great fire power, and heavy protective armor, Ordnance engineers believed, comprised mutually irreconcilable features. When a request was submitted for what the Ordnance Department considered a physical impossibility, the Research and Development Service became indignant at accusations of non-cooperation. Admittedly, pressure to achieve the “impossible” sometimes produced astonishing results, but in prevailing Ordnance opinion shortcomings in American equipment were attributable far less to Ordnance ineptness than to the shortsightedness of the using arms and to the frequent shift of AGF ideas. General Barnes felt that battle trial of some experimental matériel would prove to combat troops that equipment was available that met their needs even though AGF had not thought of it. Between early 1943 and the end of the war he repeatedly urged the battle testing of a series of heavy tanks the tank arsenal had developed. These tanks varied in weight from 45 to 64 tons and carried 90-mm., 105-mm., or 155-mm. guns. The models armed with 105-mm.

and 155-mm. guns were not tested until after the war. The model mounting a 90-mm. gun fared better. In the face of some opposition from the AGF, permission was at last secured from Secretary of War Stimson and General Marshall to send overseas twenty of the experimental model, the 46-ton T26E3. Nicknamed the General Pershing, this tank with its 90-mm. gun M3 was first used by the 3rd and 9th Armored Divisions in the drive from the Roer River to the Rhine. Despite conflicting reports of its performance the tank was standardized in March 1945 as the M26.62

Only less prolonged and heated was the disagreement about the value of self-propelled artillery, though the 105-mm. howitzer motor carriage M7 had proved itself in British hands in North Africa. The Tank Destroyer Command took exception to Ordnance proposals to construct a tank destroyer by mounting a 90-mm. gun upon a 3-inch gun motor carriage, and General McNair also objected. Later, the 90-mm. mounted on a tank chassis was enthusiastically received.63 Over medium self-propelled artillery AGF headquarters again differed sharply with the Ordnance Department. General McNair cited a British report on the battle at El Alamein which stated that the artillery preparation for the advance would have been handicapped if it had been necessary to lift ammunition to the raised platforms of self-propelled guns. When he added that the British had not paid much attention to self-propelled artillery, General Barnes, obviously considering this no valid argument, tartly replied that the British “have not gone very far with anything else either.”64 In each case the Ground Forces was eventually converted, but such items as the 155-mm. howitzer motor carriage M41 were not approved until late in the war.65

The technicalities of tank and artillery design will be discussed below.66 Here it is necessary only to note that the protracted arguments between AGF and the Ordnance Department over these developments were based wholly on professional differences of opinion. In the field of small arms such conflicts did not obtain. But as each side vigorously defended its views on tanks and motorized artillery, each sure of its rightness, relations were often distinctly strained. The controversy assumed such proportions by the summer of 1944 that the General Staff appointed a board to recommend procedures to be followed after the war. The report of the Army Ground Forces Equipment Review Board was submitted in June 1945. It carried further a less drastic plan prepared by the General Staff in 1940, revived in 1941, and then dropped as impractical, to centralize all Army research and development in a War Department Technical Committee, which, it had been hoped, would hasten standardization of new items and at the same time provide sound doctrines of tactical employment.67 The 1945 report flatly

stated the necessity of vesting control of all development of ground force weapons in the hands of the Ground Forces. “This would necessitate the creation in Army Ground Forces of development groups organized on a functional basis and staffed by users, technicians and civilian specialists.68 In his reply the Chief of Ordnance repeated his department’s conviction that acceptance of this plan would bring disaster.69 No steps were taken to put the AGF recommendations into effect.

Relations with Theatres of Operations

Theoretically, the Ordnance research and development staff had no direct relations with overseas theatres during the war. The theatre Ordnance officer attached to each theatre headquarters was the liaison between Office, Chief of Ordnance, and combat troops, and his reports were expected to supply comment and criticisms of ordnance in action. Information on enemy equipment might also be transmitted by military intelligence to the G-2 Division of the General Staff and thence to the Ordnance Department. But the system entailed delays, and before mid-1943 reports often lacked the specific data designers needed. Distance was inescapably an obstacle and the chain of command was another. Proposals to dispatch special Ordnance observers to European combat zones early in 1940 had been vetoed by G-2. In 1943 the first Ordnance Technical Intelligence units sent to overseas theatres were not welcome—they added to problems of billeting and feeding without making any immediate contribution to combat.70 While later they became an accepted part of the intelligence system and assembled invaluable data, throughout the war the Chief of Ordnance—and chiefs of the other technical services as well—felt hampered by faulty communications with the theatres.71 The surest, quickest way of getting essential information proved to be an unofficial avoidance of “channels” and recourse to personal letters from officers on overseas duty directly to the Chief of Ordnance or the chief of the Research and Development Service. Both officers relied upon this correspondence to supplement official communications.

Problems of Standardization and Limited Procurement

Two problems, be it repeated, were ever present for the Ordnance research and development staff—the problem of devising matériel that would counter any developments of the enemy and then the problem of getting new models approved in time to be of real use in combat. Knowledge of enemy ordnance and of what Allied troops needed to more than match it depended upon the adequacy of military intelligence. The working of the military intelligence system, and particularly of Ordnance Technical Intelligence and the Enemy Equipment Intelligence teams, will be discussed later.72 There remain to be examined here the consequences of the time lag between the establishment of a requirement and the moment when combat troops

had in hand the new or improved weapon filling the need. Even when the research and development staff had detailed information from combat zones and, acting upon it, produced a design calculated to meet the want effectively, months or years might elapse before the innovation was accepted by the service boards for standardization. Standardization ceased in the latter part of the war to be a preliminary to use of new items in battle, but before late 1943 it generally was, for the AGF was long opposed on principle to sending matériel into combat that had not received the stamp of approval of the testing boards in the United States. Furthermore, without standardization of a weapon, quantity production was difficult to contrive.

Review of the official peacetime procedures for acceptance of new equipment may clarify the problem. Once standardization was achieved, the responsibility of the Research and Development Service for a particular item ended. It should be noted, however, that even under the pressure of war it took months after an article was standardized to compute quantities required, negotiate production contracts, complete manufacture, and distribute the finished product to the fighting forces. The latter processes could not be greatly hurried.73 It was in the stages preceding large-scale procurement that the Ordnance Department hoped to expedite matters in World War II by telescoping or skipping altogether some of the ten steps prescribed for standardization.

Of these ten steps the first five were unavoidable and the first four usually taken rapidly. First came the decision, approved by G-4 of the General Staff, that a specific need for a new or improved item existed. Second was the statement of the military characteristics that the article must have in order to accomplish its purpose; physical characteristics such as weight, length, and width, were listed only when they affected the military usefulness of the item. This statement was drawn up by a board of officers of the using arm. An Ordnance officer represented the Department on each board. The third step was the formal initiation of a development program, a procedure handled by the Ordnance Technical Committee. The committee assigned to the project a classification, designating its type, nomenclature, and later a model or T number. Before 1942 the War Department had to approve classification; thereafter Army Service Forces assumed that function. Classification changed during the course of development. Originally labeled “required type,” an experimental model was further identified in later stages as “development type.”74 Still later, when variations of a basic model of a development type were called for, the differentiations were marked by E numbers. Thus a series of experimental tanks might be designated T26E2, T26E3, and T26E4. Following the first official classification, the project was turned over to the appropriate unit of the Research and Development Service to work out. Study of the problem might have to be protracted to explore alternative methods of attaining the desired result. In designing and building a first sample or pilot model, scientists, draftsmen, engineers, and technicians might collaborate for years. When a model embodying the stipulated military characteristics was developed and ready for its

first tests, its complete classification was “required type, development type, experimental type.”

The next five steps in peacetime tended to be long drawn out, as the tests upon the semiautomatic rifle in the 1920s and 1930s show. First the men who had designed and built the pilot model subjected it to a series of engineering tests. Each component had to correspond to the specifications. A model that met these requirements was then labeled “service-test type” and was ready for the next process—service testing. Service tests, conducted by a board under control of the using arm or occasionally by troops in the field, were to determine the suitability of the equipment for combat in the hands of ordinary soldiers. These tests almost always revealed hidden defects, parts too weak for serviceability, instruments inconveniently placed, interference of a control device with operating mechanisms, and the like. Ordnance engineers then undertook modifications of the original design to correct these faults. Even in so relatively simple a weapon as the carbine, service tests produced a list of modifications required for acceptance ranging in importance from knurling of the butt plate to redesign of the rear sight.75 Modifications might run into the hundreds in complicated pieces such as tanks and artillery. Service tests of the modified models followed until the service boards pronounced them ready for extended service tests. Items such as the carbine might be accepted without extended service tests, but major items were usually tested by tactical units in order to gauge performance under more rigorous trial than the service boards could effect. For these tests production in some quantity was necessary and the equipment procured was classified as “limited procurement type” within the broader classification of “development type.” The manufacture of the first “limited procurement type” models gave the producer experience and enabled him to eliminate production bugs.

The final step was largely a formality. If the extended service tests proved the item satisfactory, the Ordnance Committee recommended standardization and the General Staff, or after 1942 the Army Service Forces, approved it. The article then became an “adopted type” and received an M number and name by which it was entered on the standard nomenclature lists. Items less satisfactory than standard items might be classified as “substitute standard” and procured merely to supplement supply. Equipment formerly standard but now superseded by new was often classified as “limited standard” so that it could be used in the field until the supply was exhausted. When equipment was no longer considered suitable for its original purpose, it was classified as either obsolescent or obsolete. The latter was withdrawn from service as rapidly as possible.

Reducing the time consumed from the beginning to the end of the development process had to be done largely in the testing stages. It is true that the AGF proposal to have development carried on under the aegis of the arm laying down the essential military characteristics of a new weapon was clearly aimed at eliminating waste efforts early in the game by preventing the designer from proceeding with a model in which the most important features were sacrificed to less important. The Ordnance Department, on the other hand, believed the solution of that problem lay not in relinquishing development work to the user but in obliging him to stipulate the

alternative he considered preferable when it must be either/or. If, for example, the Armored Forces wanted tanks with powerful guns and great maneuverability, they must rate heavy armor protection as of secondary importance.76

Closer collaboration before drafting-board work was completed and a first pilot model built, more careful consultation between Ordnance policymakers and Ordnance engineers, might sometimes have saved time. Still more important was the role of the Ordnance member of the service board drawing up the statement of desired military characteristics of a new item. Building a sample incorporating unacceptable features could usually be avoided if this Ordnance officer were at once a competent engineer and a salesman skillful enough to persuade the board to request what the Ordnance Department believed feasible and essential features of design. Much depended upon his adroitness and ability. Unhappily, as the war wore on, the ideas of the service boards did not always coincide with those of combat troops overseas, but that was a complication the Ordnance Department could not resolve.77 Nevertheless, in developing most new items, when time was lost needlessly it was in the course of service testing, modifying, retesting, and extended service testing. If, instead of being submitted to prolonged tests against dummy targets in the United States, new matériel could be shipped to the active theatres for battle trial, then, the Ordnance Department contended, a dual purpose would be served: the research and development staff would have indisputable proof of weaknesses and strong points of the new equipment under real, not simulated, combat conditions, and the armies in the field would have the use of weapons usable even if far from faultless. Later modifications could be made with greater certainty.

Here was a variation of the Ordnance pleas of the 1930s protesting the refusal of the War Department to standardize matériel until it was as nearly perfect as possible. Ordnance engineers concurred in Colonel Studler’s statement of 1940: “The best is the enemy of the good,”78 But after Pearl Harbor official standardization was not the point at issue. It was the battle testing of T models. The AGF had some reasons for opposing the shipment to overseas theatres of matériel not yet wholly proved. The scarcity of cargo space early in the war was one; the possible infringement of Ground Forces control over tables of equipment was another; danger to the user, most compelling reason of all, was a third,79 A failure of a new item to accomplish in battle what it was intended to do might cost far more than loss of time. The Ordnance Department’s job, the AGF argued, was to develop, manufacture, and issue battleworthy munitions; it should not expect the using arms to risk the success of their mission—fighting—to prove the adequacy of the Ordnance Department’s performance. General McNair repeatedly objected to issuing matériel possessing

even minor defects of design.80 Moreover, battle testing small quantities of a new device introduced the hazard of giving the enemy a chance to develop countermeasures before a successful new weapon could be fully exploited in large-scale attacks.