Chapter 2: Procurement Planning

Planning for military preparedness in the United States before World War II differed somewhat from planning by European military establishments. The differences stemmed largely from two factors: lack of a munitions industry in this country comparable to those of the major European nations, and American emphasis on maintenance of a small Regular Army backed by a modest reserve of war supplies. War Department planners had for many years assumed that, in event of war, the United States would have time to mobilize its reserves both of manpower and of industrial production, and would not need to maintain either a large standing army or large stores of munitions. Quantities of matériel left over from World War I were kept in storage during the 1920s and 1930s, but ammunition gradually deteriorated and weapons became outmoded. With each passing year, therefore, the Ordnance Department gave more attention to development of plans for speedy conversion of private industry to new munitions production in time of war. Ordnance procurement plans provided essential background for the vast rearmament effort launched in 1940.1

In spite of the injunction of the National Defense Act of 1920 to plan in advance for military supply, the War Department found the climate of opinion in the United States during the 1920s and 1930s not at all favorable to such planning.2 The Planning Branch in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of War, headed in the middle 1930s by Col. Charles T. Harris, Jr., provided official encouragement for procurement planning, but its activities were strictly limited. During the years when hopes for peace were high, and military budgets low, this agency managed to keep alive the system of district procurement offices within the supply services and to promote arrangements with industry for

converting to war production.3 By the spring of 1940 a change of popular sentiment was taking place; the American people were demanding more adequate national defense, but they still found the thought of planning for another war extremely distasteful.

The neutrality legislation of the 1930s had reflected the public’s mood by forbidding shipment of American arms to other nations. Though the ban was altered in November 1939 to permit warring nations to purchase munitions in this country, all transactions had to be on a cash-and-carry basis. Under these circumstances, the British and French purchasing commissions made few contracts for munitions before June 1940, preferring to shop around for more favorable prices and to use the United States as a source of aircraft, machine tools, and scarce raw materials.4 It was only after the disastrous defeats of May and June 1940 that the British plunged into an “arms at any price” buying campaign. Meanwhile the build-up of munitions for the U.S. Army was proceeding cautiously but picking up speed. Using a financial yardstick, General Wesson summed it up in the fall of 1939 as follows:

In the fiscal year 1938 approximately $25,000,000 was expended for the procurement of Ordnance material. In the fiscal year 1939 approximately $50,000,000 has been and is being expended for like purposes. In the fiscal year 1940 a total of approximately $150,000,000 has been made available. …5

The depression of the 1930s had a very real, though indirect, influence on procurement planning. Since most industries were operating far below their normal capacity during the depression, Army planners tended to look upon the unused portion of the nation’s industrial plant as an immediately available reserve for war production.6 Unused industrial capacity was, of course, far more readily available for Quartermaster items, which were largely commercial in nature, than for Ordnance items. But the existence of idle factories, tools, and manpower throughout nearly the whole decade of the 1930s served to condition all planning for war procurement. It placed primary emphasis on utilization of existing capacity, rather than on building additional plants, and tended to minimize estimates of the probable impact on the civilian economy of a war production program. It gave rise to the belief, still widely held in 1940, that the capacity of American industry was great enough to support both a war economy and a peace economy, or, to employ the language popular at the time, to produce “both guns and butter.7

Ordnance devoted far more attention to procurement planning during the interwar years than did any of the other Army supply services. In the early 1920s Ordnance officers took a leading part in the establishment of the Army Industrial College, and throughout the interwar years they held key positions in the Planning Branch of the Office of Assistant Secretary of War.8 Through its many procurement district offices Ordnance kept officially in touch with industry in all parts of the nation while the Army Ordnance Association, on a semiofficial level, promoted public interest in industrial preparedness. In fiscal year 1939, Ordnance Department procurement planning (including educational orders) accounted for about $8,000,000 of the $9,275,300 allocated for all War Department (including Air Corps) procurement planning for that year. In the early months of 1940 Ordnance had 231 officers and civilians engaged in procurement planning activities compared to only 264 for all the other supply services combined (including the Air Corps).9 That Ordnance defense production got off to a fast start in 194041 was due in large measure to this prewar planning.10

Plans for New Facilities

Because of the specialized nature of its products, the Ordnance Department was fully aware of the need for scores of new facilities in time of war.11 For such products as smokeless powder,12 TNT, ammonia, and small arms ammunition, and also for loading artillery ammunition, there were no existing plants that could be readily converted. Furthermore, because powder and ammunition plants offered none of the usual attractions for private capital, it was recognized that they would have to be built at government expense if they were to be built at all. Working on these assumptions during the interwar years, Ordnance engineers, cooperating with the nation’s small peacetime explosives industry and using the technical developments of Picatinny and Frankford Arsenals, drew up plans and specifications for typical plants to be built in time of need. In 1937 they established an office in Wilmington, Delaware, to carry on this work, and in 1938 Congress appropriated funds for the purchase of some of the highly specialized machinery required for the production of

powder and small arms and for the operation of loading plants. By the summer of 1940, thanks largely to the efforts of General Harris, Ordnance had a fairly clear idea as to the type of new facilities it would need to produce smokeless powder, explosives, ammonia, and TNT.13 These plans and reserve machinery, General Wesson told the Truman Committee in April 1941, proved to be of “untold value” in promptly starting the new facilities program.14

In the summer of 1940 the Munitions Program of 30 June opened a new era in procurement planning. It called for immediate procurement of equipment for 1,200,000 ground troops, procurement of important long-lead-time items for a ground force of 2,000,000, creation of productive capacity for eventually supplying a much larger force on combat status, and production of 18,000 airplanes. Approval of this plan, formulated in large part by an Ordnance officer, Col. James H. Burns, was a big step forward along the road toward effective industrial mobilization.15 It made a sharp break with all previous plans to supply equipment for small Army increments, for it established broad planning goals far in advance of any formal action to increase the strength of the Army. It cleared the way for creation of munitions plants for a big military effort and left to the future the tedious task of refining and adjusting its parts. But Ordnance planners found that there were still many unknown factors in the equation—new weapons, tables of equipment, estimated rates of consumption, speed of mobilization, timetable for overseas deployment, and, most important, how much money would be available.

Although Ordnance maintained six manufacturing arsenals in time of peace, they were not intended for large-scale production in time of war.16 It was estimated that all the arsenals combined would never be able to produce more than about 5 percent of the Army’s requirements for war. In the initial stages of an emergency, while

industry built new plants, the arsenals were to produce certain types of urgently needed munitions; but, with a few exceptions, their major wartime role was to serve as sources of production techniques, as development centers, and as training grounds for Ordnance production personnel, inspectors, and key men from industrial plants. The main burden of war production would fall on private industry and on new government-owned, contractor-operated (GOCO) plants built for the purpose.17

Plans for Decentralized Procurement

In terms of organization, the foremost principle of Ordnance procurement planning in the summer of 1940 was decentralization through the six manufacturing arsenals and the thirteen district offices.18 Ever since World War I, Ordnance procurement plans had provided that, with certain exceptions, contracts for war matériel would be placed by the arsenals or the district offices, each of which was familiar with industries capable of producing the required munitions. Over-all direction of the program in wartime was to be exercised from Washington by the Chief of the Industrial Service, General Harris, but the day-by-day work of negotiating and administering contracts was to be carried on in the districts.19

The districts had a combination of civilian and military leadership. Each district had as its chief (until 1942) a prominent local businessman, usually a Reserve officer, who devoted part of his time to district affairs. To each district a regular Ordnance officer was assigned on a full-time basis as assistant chief or executive officer. Most of the districts also had advisory boards made up of prominent business leaders who were sympathetic, at least in theory, with the Ordnance Department’s preparedness plans. There was an element of “window dressing” about these boards but there was some real substance, too. The New York district, for example, numbered among its board members in the 1939-41 period such prominent figures as Patrick E. Crowley, president of the New York Central Lines; James A. Farrell of the United States Steel Corporation; Maj. Gen. James G. Harbord (Ret.), chairman of the board of directors of the Radio Corporation of America; Robert P. Lamont, former Secretary of Commerce; and Owen D. Young, chairman of the board of the General Electric Company. The Cleveland district probably reflected the experience of other districts when it reported that the names of highly respected industrialists on its advisory board helped to unlock industrial doors.

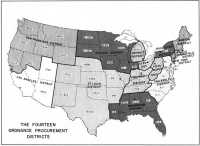

The fourteen Ordnance Procurement Districts

In the early stages of an emergency, while the districts built up their staffs and established operating procedures, the arsenals were to let contracts for the more complicated types of matériel and were to aid the districts by providing blueprints, specifications, and technical guidance to manufacturers.20 Up to July 1940, the districts had no authority to award contracts. During the preceding eighteen months they had handled some of the preliminary work for educational orders and production studies.21 They had been given increasing responsibility for inspecting finished products, but they had had no authority to place orders with industry. The grant of that authority to the districts was nevertheless an integral part of the Ordnance plan, and to lend realism to such planning each district was requested in December 1939 to submit its recommendations covering the first twenty contracts it expected to place in time of war. The reports sent in by the districts showed names of plants, items to be produced, types of contracts to be used, and the reasons for selecting each plant.22 The Chicago district, to cite one example, planned to place orders with Elgin National Watch Company for time fuses, with Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Company for machining 75-mm. shells, with Bucyrus-Erie Company for 3-inch AA gun mounts, with Stewart-Warner Corporation for metallic belt links, and so on through the list.23

The Industrial Service in mid-July 1940 described in some detail the specific procurement procedures to be followed by the arsenals and districts. To use the district procurement system and at the same time retain competitive bidding to the maximum extent, Ordnance proposed to divide the requirement for each item among districts that had facilities allocated for production of that item.24 When district offices received these assignments they would request facilities allocated to them to submit bids. The bids from all districts would then be reported to the Ordnance office in Washington. That office would compare the bids with each other and with known costs of manufacture at arsenals and would make awards to facilities that offered the best assurance of producing on schedule and at a fair price. Rigid acceptance inspection by the district offices, coupled with periodic interchangeability tests, would assure uniformity of product. In analyzing the plan the Chief of Ordnance wrote:

It will be observed that this plan, in effect, provides for nation-wide competition among allocated facilities, with contract negotiations carried on in the geographic territories of the several Ordnance Districts. Assurance of the timely production of munitions through use of the district system cannot be obtained in any other manner, and it is considered that

the plan will bring forth the best facilities producing at the lowest cost, consistent with the desired distribution of the load.25

It was estimated that in meeting requirements of the Munitions Program of 30 June the districts would place approximately four hundred prime contracts, utilizing some eight thousand facilities. For that part of the procurement load assigned to the arsenals, competitive bidding among allocated facilities or any other facilities with suitable production experience, and the signing of fixed-price contracts, were to be the rule. Arsenal commanders had authority to close contracts involving less than $50,000 without referring them to Washington for approval, but larger contracts had to have the approval of the Chief of Ordnance, the Assistant Secretary of War, and Commissioner William S. Knudsen of the Advisory Commission to the Council of National Defense (usually referred to as NDAC).26

Each district office was to administer its own contracts and also all contracts with industries within its borders placed by the arsenals. Administration of contracts included, among other things, helping contractors solve production problems, making periodic reports to the Chief of Ordnance on the status of production, inspecting finished products, and paying for the goods delivered. By means of production reports from the districts and the arsenals the Chief of Ordnance planned to exercise close control over the flow of components to final assembly points and loading plants, and to bring pressure to bear upon contractors who failed to meet their production schedules.

Contract Forms and Legal Restrictions

By the summer of 1940 the Assistant Secretary of War had approved six stand- and contract forms for use in a national emergency.27 These had been drafted to prevent recurrence of the confusion of World War I when purchasing agencies of the War Department evolved and used over four hundred different and troublesome contract forms. Ordnance expected that the most important of the approved contracts would be Standard Form No. 32, a fixed-price supply contract to be used under the system of competitive bidding. It was thought that this type of contract would account for 95 percent of all awards by the district offices. But, because of the difficulty of estimating costs of war equipment that manufacturers had never before produced, other types of contracts, such as the cost-plus-fixed-fee (CPFF), which allowed greater flexibility in pricing, were also considered.

In January 194.0 the Ordnance Department regarded the legal restrictions on peacetime procurement as a major factor that would retard the award of Ordnance contracts in time of emergency. It cited the law requiring public advance advertising and award to the lowest responsible bidder, and other legislation affecting hours, wages, and profits. In January 1940, General Wesson stated that because of this legislation, with which many

Assistant Secretary of War Louis Johnson

manufacturers were not familiar, it took about ninety days to advertise for bids, examine the bids, and make an award. He went on to say that this procurement cycle could be cut from ninety to thirty days for essential items in an emergency only if the industrial mobilization plan were put in effect, legal restrictions removed, and Ordnance permitted to negotiate directly with selected facilities.28

Surveys of Industry

In the summer of 1940 each district office had on file hundreds of reports of industrial surveys made during the preceding years and kept as nearly up-to-date as possible with the handful of officers and civilian engineers available for the job. These surveys, made under the broad supervision of Louis Johnson, Assistant Secretary of War, covered major industrial plants within each district that might be converted to munitions production in time of war. For each plant the survey recorded the firm’s normal product, its productive capacity, floor space, and major items of equipment. It also gave information on the firm’s financial standing and resources, transportation facilities, availability of skilled workers, and, most important, the type and quantity of Ordnance matériel the company might produce in an emergency. Above all, Ordnance was interested in firms with good management and strong engineering departments. “It was not just the machines and floor space that counted,” observed Brig. Gen. Burton 0. Lewis, a leader in Ordnance procurement planning. “Of even greater importance were the men—the skilled workers, the production engineers, the executives who understood the secret of high-quality mass production.”29 In most cases, after the survey

was complete, Ordnance and the company signed an informal agreement known as an “accepted schedule of production” showing specifically what the company was prepared to produce.30 Accepted schedules of production were “all important,” General Wesson told Industrial College students early in 1940. “They are part of our war reserve. They are as vital as the material in our storehouses.”31

Before 1940 the process of making industrial surveys was slow, hampered by lack of interest on the part of some manufacturers and by lack of personnel in the district offices. It was also hampered by the fact that not all Ordnance district officers had sufficient manufacturing background and engineering knowledge to do a good surveying job. But during the first six months of 1940 the tempo of survey work increased markedly, stimulated by a procurement planning conference called by Louis Johnson in October 1939. The Pittsburgh District made more than two hundred surveys during the first half of 1940 as compared with only thirty-nine during the preceding six months, and the cumulative total for the District in July 1940 rose to five hundred.32

By 1940 the purpose of industrial surveys had generally ceased to be discovery of firms that could turn out complete items of Ordnance matériel ready for storage or issue. The search was for several firms, each of which might manufacture one or more components or perform one or more steps in the whole process of manufacture. Further, surveying officials were looking for plants that could do the job by using equipment already on hand and with workers already trained in similar processes.

The search for plants that could undertake Ordnance production with existing equipment was dictated largely by the anticipated shortage of machine tools. Ordnance planners were aware that the nation’s small machine-tool industry would be swamped in time of war; they realized that every possible step should be taken to utilize existing machines rather than count on extensive retooling. The dearth of machine tools in the South was spectacularly revealed in the fall of 1939 when the Birmingham District office reported that, of eighteen contractors approached, not one had the tools needed to begin production on any type of matériel contemplated for production in that District.33 The educational orders program revealed that lack of machine tools was also a problem for industries in the North. In January 1940, for example, the Philadelphia District reported that bids on educational orders “indicate a larger deficiency of machine tools than was anticipated six months ago.”34

Planning for an adequate supply of gages—those essential measuring and checking devices needed to assure precision manufacture—was an altogether different story. Profiting from the experience of World War I, the Ordnance Department during the 1920s and 1930s took a number of important steps to assure an adequate supply of gages for a future emergency. More than half a million World War I gages were collected, checked for accuracy, and put in storage. During the 1930s nine district gage laboratories were established at universities to provide gage-checking services to manufacturers and to train personnel for gage-surveillance duties, and gage laboratories were established at all the arsenals. Beginning in 1938 Ordnance made a concerted effort to design gages for all items for which it was reasonably sure that production would be required. Gages on hand at the arsenals were brought up to date, and new gages were procured for

standard items. In July 1940 Ordnance allotted approximately $2,500,000 for gage procurement in advance of actual production of weapons or ammunition. At the same time, steps were taken, in cooperation with other government agencies and private industry, leading to allotment by the War Department of $4,000,000 to expand productive capacity of the gage industry.35 So effective were these preparatory measures that the gage problem, which proved so serious in World War I, was scarcely a problem at all in World War II.

Closely related to industrial surveys was the system by which a certain percentage of a plant’s capacity was allocated by the Army and Navy Munitions Board for the exclusive wartime use of one or possibly several supply services.36 Originally adopted to guard against recurrence of the confusion and interagency competition that had marked the procurement process in 1917, the allocation system was designed also to forewarn industry of the tasks it would be called upon to perform in time of war, to promote mutual understanding between industry and procurement officers, and to serve as a basis on which to plan war production. The supply services furnished allocated facilities with drawings, specifications, descriptions of manufacture, and in some cases samples of the critical items they were scheduled to produce, and encouraged them to study means of converting their plants to munitions production.37

Educational Orders and Production Studies

Perhaps the most radical departure from conventional practice, and the most highly publicized feature of Ordnance prewar procurement plans, were the educational orders. Approved by Congress in 1938, after years of urging by procurement officers and the Army Ordnance Association, the Educational Orders Act permitted placement of orders with allocated facilities for small quantities of hard-to-manufacture items. The purpose was to give selected manufacturers experience in producing munitions and to procure essential tools and manufacturing aids. Other supply services participated in the program to some extent, but the bulk of the educational orders were for Ordnance matériel.38

After a rather cautious start in fiscal year 1939, when Ordnance awards went to only four companies, the program leaped ahead in fiscal 1940 with more than eighty educational awards. As orders for a wide range of items went to manufacturers in all parts of the country, the district offices and arsenals plunged into the task of sharing with industry their knowledge of production methods peculiar to munitions making. The invitations to bid for educational orders were issued by the arsenals and the contracts were let from the Office of the Chief of Ordnance, after approval by the Secretary of War and the President, as required by law. Selection of firms to receive invitations to bid, negotiation of contract details, and inspection and acceptance of finished matériel were all managed by the district offices. The entire process was thus an educational experience for the Ordnance Department as well as for the manufacturers. But, just as the program was getting well under way in the summer of 1940, it was suddenly halted. Because of the swift German victories in western Europe and the huge appropriations for military supplies voted by Congress, educational orders gave way to production orders. Ordnance placed its last educational order in July 1940 while the British Army was recovering from its evacuation of Dunkerque.39

The prevailing opinion in the Ordnance Department and among contractors holding educational orders was that the program, in spite of being too limited in scope and too brief in duration, proved its value as a means of industrial preparedness.40

The Winchester Repeating Arms Company estimated that its educational order for the M1 rifle saved a full year’s time in getting into quantity production.41 Not all companies with educational orders completed them successfully, nor were all holders of educational contracts later given production orders for exactly the same product. But in April 1941 Ordnance reported that about half had received production orders for the same or similar items.42 All told, the educational orders had spread the “know how” of specialized ordnance manufacture to some eighty-two companies, made available to them at least a minimum of special tools and other manufacturing aids, and, by familiarizing them with Ordnance inspection methods, probably cut down rejections on later production orders.43

While Ordnance was launching its educational orders experiment it also entered

into nearly one hundred contracts for production studies to determine the techniques and equipment needed for quantity production of items of ordnance.44 Congress authorized the War Department to purchase such studies in 1939. In the spring of 1940 General Wesson told a Congressional committee that funds for 420 additional studies should be appropriated as he considered such studies to be “of paramount importance to national defense.”45 Averaging about $5,000 each, these studies had the advantage of being much cheaper than either educational orders or production orders, but they were of far less value. Their usefulness depended in large measure on the strength of the contracting company’s engineering staff and on the seriousness with which it tackled the study. In the final analysis, only production orders under wartime conditions could provide the proof of the pudding. That proof was not slow in coming, for in some cases contracts for production studies were replaced, even before they were signed, by production orders.46

During the year ending 30 June 1940 the Ordnance Department awarded 1,450 contracts to industry for approximately $83,000,000 worth of weapons, ammunition, and new machinery, and it allocated a nearly equal sum to the arsenals for production and modernization.47 Plans called for completion of this 1940 program within two years, with 95 percent of it completed by December 1941. “In general,” observed General Wesson, “it takes approximately one year to place orders and to get production started, and a second year to finish any reasonable program.”48 Beyond the 1940 program, provision had been made for a tremendous increase in production when funds for fiscal year 1941 became available.

Conclusion

Such, in broad outline, was the nature of Ordnance procurement planning in the summer of 1940. It was fundamental].) sound, in terms of the political and economic atmosphere of the time. Its most serious weakness lay in the limitations on its application and development. The value of plant surveys made in the late 1930s was demonstrated time and again during the defense period and was recognized by the Office of Production Management (OPM) in the spring of 1941 when it declared that they “have been found adequate for the purpose of OPM’s defense contract service and will not be duplicated.”49 But Ordnance and the other supply services never had enough money or enough manpower to carry on a fully adequate program of industrial surveys. Similarly, the educational orders program, although soundly

conceived and effectively administered, was started so late and was allotted so little money that its full value was never realized. The system of plant allocations formed the basis for a fruitful exchange of information between Ordnance and industry during the interwar years, and, when the emergency came, the allocation plans provided most useful guidance for placing Ordnance contracts. But the allocation plans were only a first step toward industrial preparedness. Their effectiveness depended upon their being backed up by the district system, the arsenals, and a competent managerial staff in Washington.

Maintenance of the six manufacturing arsenals as the “Regular Army of production” throughout the interwar years was one of the most important Ordnance contributions to the cause of industrial preparedness. But it must also be remembered that, because of lack of funds, the equipment of the arsenals was not kept up-to-date. Although some progress toward modernizing arsenal equipment was made in the late 1930s, particularly at Frankford, by 1939 some 80 percent of the machine tools in the arsenals were eighteen or more years old, and some of them antedated the Civil War.50 With such equipment the arsenals were not able to keep abreast of the latest developments in manufacturing techniques, nor were they fully prepared in 1940 to serve as model factories to be copied by private industries about to convert to munitions making.

Without the district offices, with their continual and friendly liaison with industrial leaders, the paper plans for war procurement would have been far less valuable than they actually proved to be. But the fact that no annual meeting of the district chiefs was held between 1931 and 1935 because of lack of funds is eloquent testimony to the limitations on district activity during those years. So is the fact that before 1939 the employees on duty in the average district office could be counted on the fingers of one hand. It is no doubt true, as General Harris asserted, that there was never a time in the 1938-40 period when he could not gain a sympathetic hearing from the president of any leading corporation in the United States to discuss procurement plans. In some degree the same was true of the district chiefs who were themselves prominent industrialists and were supported by advisory committees composed of industrial leaders. But most businessmen were reluctant to undertake detailed planning for an unforeseeable future. They were willing to go just so far, and no farther. As a result, within the limited budgets of the peacetime years the districts did a great deal of valuable work, but in 1940 much still remained to be done before a major program of munitions production could be launched.

In one respect a great advance was made in Ordnance procurement planning between the fall of 1939 and the fall of 1940. More and more people, both in and out of the Army, began to take such planning seriously for the first time. Before

1939, when the prospects of American involvement in war seemed remote, only a few people took procurement planning seriously. Among these, it should be noted, were the members of the Army Ordnance Association, who worked throughout the interwar years to promote the cause of industrial preparedness for national defense. Established in 1919, the AOA immediately gained recognition in both industry and government when it elected as its first president Benedict Crowell, director of munitions in World War I. At the annual dinners held by AOA posts in major cities the most important leaders of American industry were brought together to consider industry’s role in national defense. The bimonthly magazine, Army Ordnance, brought to all members of the association articles on new developments in ordnance engineering along with news and comment on industrial preparedness.

In the late 1930s Louis Johnson made countless speeches in all parts of the country urging the need for industrial preparedness, but the response was generally apathetic, and frequently hostile.51 Then, in the spring of 1940, the swift German victories aroused public interest in rearmament of the United States and in plans for national defense. Instead of being denounced for making war plans, military men were now criticized for not having made better plans. With the launching of the munitions program in the late summer of 1940 a new attitude prevailed in the Army and among businessmen. The change did not come overnight, nor was it complete before Pearl Harbor, but it had a steady growth. It gave to all considerations of procurement plans a sense of reality and urgency they had never had before. It not only freed the procurement planners of the psychological handicap under which they had labored for two decades but it also brought forth the money needed to transform blueprints into weapons.52