Chapter 2: Early Activities in the United Kingdom and North Africa

First Plans for the United Kingdom

The Quartermaster effort against the Rome-Berlin Axis had a modest beginning in the critical late spring of 1941, when American staff planners assumed that, in the event of a declaration of war, small ground and air forces would be established in the United Kingdom as soon as possible.1 On 19 May 1911 the War Department created a Special Army Observer Group (SPOBS), under Maj. Gen. James E. Chaney, in London. Chaney included a Quartermaster Section in his group consisting of one officer, Lt. Col. William H. Middleswart.

Born in West Virginia on 19 October 1894, Middleswart was one year over the age limit which the Chief of Staff, United States Army, had set for an overseas observer, but he was nonetheless well qualified for his staff position. His Regular Army commission in the Quartermaster Corps dated back to 1 July 1920. For the next four years he was in the Office of The Quartermaster General and thereafter served five years in field assignments, including one tour of duty in the Philippines. After two years of schooling at the Army Industrial College and Army War College between 1936 and 1938, and a year of staff work in the Panama Canal Zone, Middleswart in July 1940 became the officer in charge of the Procurement Division of the Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot. His call for duty with Chaney came in May 1941, and he immediately left for England.

In the absence of any formal alliance Middleswart’s work at first was exploratory and confined to the field of planning. He exchanged points of view with his British colleagues, becoming more and more familiar with the problems of coalition warfare. Making arrangements for the provision of solid fuels to the U.S. troops arriving in Iceland, as British forces there were withdrawn for duty elsewhere, was Middleswart’s first practical assignment in SPOBS.2

After numerous conferences Middleswart also made plans to provide

Quartermaster support for U.S. troops in the United Kingdom. In mid-September 1941 he submitted his initial recommendations. Current plans contemplated a force of 107,000 men, including 87,000 ground and air troops and 20,000 service troops, to be distributed under a theater commander within four tactical subcommands, plus a base area. Though no date had been set for their arrival, the combat troops were to be located as follows: in Northern Ireland, 30,000 ground troops; in eastern England, a bomber force of 15,000 air troops and 21,000 ground troops; in Scotland, 13,500 combat troops; and in a small area, thirty-five miles southeast of London, a reinforced regiment of 7,500 men.

Within the Midlands base area, the British were prepared to let Americans select Quartermaster sites and to provide them with all the necessary facilities in full operating condition. Middleswart’s major objective was to set up an establishment requiring little assistance from the British. But it was impossible for the Americans to ignore local conditions. The common interest demanded that the independence of American facilities in base and troop concentration areas should not be attained through wasteful duplication of facilities. Supplies had to enter British ports and move over British railways and highways. Depots were to be located in existing British buildings as far as practicable. Services which had to be performed close to the troops, such as laundry and bread baking, were to be handled by the British insofar as their resources permitted.

Middleswart’s storage plan provided that half of the contemplated supply stockage would be located in areas contiguous to each of the four troop concentrations, with the remaining portion deposited in two general base areas. He suggested to Chaney that two general depots be operated at first, one in Northern Ireland, the other in the Midlands. These depots were designed to maintain 100,000 men on the full scale of clothing and equipage. Standard American rations were to be furnished automatically from the United States. To support the regiment near London the plan recommended activation of a provisional battalion to provide all Quartermaster services. For area defense against parachute attack, a very real threat in 1941, Quartermaster troops should be armed with rifles instead of pistols, and they should have trucks equipped for driving during blackout conditions.

Middleswart further submitted estimates for Quartermaster troops on a scale commensurate with a 100,000-man force. He recommended that all QMC units and half of the 30-day supply level for depots leave the United States at least a fortnight before the departure of the combat troops. He wanted to have accommodations and depots set up and in operation when they debarked. The advantage of such arrangements was emphasized over and over in subsequent planning of troop priorities and shipping schedules, usually with only limited success.3

With the entry of the United States into the war, time became the most important element in Quartermaster plans, which for the moment contemplated support to one army corps, deployed in

defensive positions. Without a staff, Middleswart could not handle the administrative details for supporting a corps. Organizationally, SPOBS was enlarged and redesignated Headquarters, United States Army Forces, British Isles (USAFBI), on 8 January 1942, with Chaney retaining command. Until 24 May 1942, Chaney had no separate administrative command, and Middleswart continued as a staff planner. Between 8 January and late May 1942, a Quartermaster staff was gradually assembled. Maj. Thomas J. Wells, an infantry officer borrowed from the office of the London Military Attaché, Maj. Frazier E. Mackintosh, a Regular U.S. Army officer recalled from retirement in London, Capt. John L. Horner, quartermaster of the American Embassy, and 1st Lt. Louis G. Zinnecker comprised the new Quartermaster Section. On 1 May, Lt. Col. Robert F. Carter, Maj. James E. Poore, Jr., Capt. Leo H. McKinnon, Capt. Burton Koffler, Capt. Gordon P. Weber, and a score of enlisted men arrived from the United States.

Early in January 1942, Middleswart received word that V Corps headquarters was to be activated in Northern Ireland and would assume command of MAGNET Force, consisting of an armored division and three infantry divisions, plus appropriate service troops, and totaling approximately 105,000 men. On 7 January Chaney informed the War Department of his quartermaster needs for the first convoy: POL and solid fuels were not to be sent; tentage, gasoline cans, and 35,000 C rations were needed, but not cotton clothing. Chaney also asked that the troops wear old-type steel helmets. The QMC’s new type somewhat resembled the German helmet, and training British troops to recognize it would require time.4

Actually, MAGNET Force was scaled down by the War Department before V Corps headquarters assembled. Middleswart meanwhile had arranged with the British for debarking the four divisions, for billeting and feeding V Corps, and for furnishing the divisions with motor vehicles, British accommodation stores, and other essentials pending the unloading and movement of supplies which supposedly were to be shipped with the troops or were to follow them soon. Wells and Zinnecker had gone to Northern Ireland to receive the first arrivals. On 26 January Chaney and Middleswart were at Belfast to greet about 4,000 men of the 34th Infantry Division. Disappointment over the decrease in MAGNET Force soon faded as War Department plans for deploying U.S. air power in the United Kingdom began to unfold. On 20 February Brig. Gen. Ira C. Eaker arranged with the Royal Air Force to provide quartermaster support for units of the U.S. Eighth Air Force. On 11 May, the first airmen arrived in England.

The War Department had announced as early as January 1942 that a 60-day level of supply, except ammunition, would be sent to the United Kingdom for U.S. troops stationed there. Local procurement was definitely encouraged. Except for Middleswart’s exploratory planning before 7 December 1941, little or nothing had been accomplished for the reception and storage of the 60-day levels. In fact, the prevailing concept continued that the Americans would decentralize their operations out of two base areas

somewhere in the Midlands and Northern Ireland. Every day of delay in granting Chaney a definite logistical plan hobbled Quartermaster operations, which after February were almost solely confined to Northern Ireland Base Command, a provisional organization.

To assist V Corps and its new base command Middleswart, with an expanding staff after 1 May, made definite assignments among his personnel. Poore headed plans and procedures; Carter worked on subsistence; Mackintosh handled administration; and Weber, Koffler, and McKinnon attended to matters of supply. In their early planning the staff attempted to draw upon the experience of British quartermasters supporting the Eighth Army in Libya and Egypt.

The first arrivals in V Corps had to use overtaxed British resources. Though Middleswart had continuously requested the inclusion of Quartermaster troops in V Corps and its provisional base command, none came, and the USAFBI Quartermaster Section could provide only a series of “how to do it yourself” circulars to show tactical units how to arrange for their own retail services. For these circulars, Middleswart gathered information from many British war agencies including the War Office, the Air Ministry, and the Ministries of Aircraft Production, Supply, Food, Petroleum, Wool Control, and also the Navy Army Air Force Institute (NAAFI), a service organization corresponding to the U.S. Army Exchange Service.

For two months after its arrival, V Corps subsisted on the regular British ration. The troops found this ration rather scanty, and disliked it because of its high proportion of starches, cabbage, and mutton. On 16 February 1942, Middleswart had prescribed the American field ration, type A, for V Corps, but this could not be issued until sufficient stocks had arrived, a depot system had been established, and balanced stocks were assured. Supplies did not arrive on schedule, and to fill the gap a modified British-American ration was developed. All items in it were of British origin, but it was a somewhat more generous ration, and better suited to American tastes. Slowly it came into use, and meanwhile V Corps kept one B ration and two C rations in reserve, rotating their use on occasions.5

In Class II and III supply planning Middleswart had to improvise at every step. Clothing and individual equipment on the current Table of Allowances (T /BA 21)—a revision appeared in June 1942—included items that had been designed to meet the needs of either trench warfare or peacetime garrison duty. Under the old T /BA initial issues supposedly were to eliminate many of Middleswart’s clothing problems. Monthly requisitions were designed to bring clothing levels to the sixty-day mark quickly and planners believed that this would see V Corps through its formative period. But the level was unrealistic. Also, requisitions stayed on file in The Quartermaster General’s Office as German submarines, now operating off the coastal shelf of the United States instead of in European waters, forced the Allies to husband their precious shipping. Discussing his clothing problems with the British, Middleswart proposed that

shipping space could be conserved through a system of exchange. In brief, Americans would release items manufactured in the United States to British troops in the Pacific; British-made goods would replace items for Americans in the United Kingdom. For many weeks the exchange could not be arranged and direct local procurement remained the only potential source for Class II supplies.

Gasoline, kerosene, diesel oil, and lubricants, all in cans, were to be dispensed to American users when they landed. Vehicles would be serviced at British Army gasoline pumps. This remained the Class III pattern until mid-June 1942 when wholesale issue of POL was arranged for V Corps. Americans found Ireland’s winter unexpectedly severe and Middleswart arranged to increase the daily allotment of coal, charged to reverse lend-lease. As spring wore on, Middleswart developed more and more standing operating procedures for V Corps use in completing arrangements for local services such as laundry, shoe repair, and dry cleaning. But, as troop strength increased and American thoughts turned from Northern Ireland to England itself as a billeting place, it was evident that tactical commanders would soon require a regularly constituted SOS.6

From January until late May 1942, Middleswart’s planning for V Corps reflected Allied concern with Britain’s immediate defense, even though his American superiors soon learned that Quartermaster requirements for the United Kingdom would have to be recast in a new mold. By the end of April, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his military advisers, working with comparable British officers, had decided that the most effective move against the Axis Powers was an invasion of northwest Europe, using the United Kingdom as a base of operations. The two governments ordered the new strategy, dubbed BOLERO, executed at the earliest practicable moment. Anglo-American planners projected BOLERO in three phases: concentration of resources in the United Kingdom, a cross-Channel attack, and preparations at beachheads prior to a continental advance. An intensified air attack on the Continent would accompany all three phases. To avoid confusion planners subsequently narrowed the meaning of BOLERO to a purely logistical concept, and applied the code name ROUNDUP to the tactical phase of the operation.7

As BOLERO planning progressed, a theater level command to administer its American aspects, calling for a new commander with a redefined and specific mission, became a definite necessity. It was generally anticipated that, following the War Department’s lead, the new commander would subdivide his command into three operational commands, consisting of a ground force, an air force, and a service of supply. On 3 May 1942 the Commanding General, Army Service Forces (then SOS), Lt. Gen. Brehon B. Somervell, discussed his SOS concept for

the new theater with Maj. Gen. John C. H. Lee, the War Department’s candidate to command all supply services in the new theater. Four days later The Quartermaster General had been briefed on Lee’s SOS plans, and Lee, in turn, received the name of Brig. Gen. Robert M. Littlejohn as Chief, Quartermaster Service.

By 14 May Lee had talked with Littlejohn, described his draft SOS directive, and suggested the assembly of a staff for overseas duty at the earliest practicable date. As May faded into June, Littlejohn estimated his personnel requirements, closely following what he had been able to learn of Lee’s tentative plan. He hoped to keep Middleswart as a key planner. Carefully selecting his staff, Littlejohn submitted modest personnel requests. In terms of numbers they reflected his understanding that he would initially play a planner’s role, that he would be responsible for a staff to handle his portion of a general depot service, to be operated under G-4, that the depot system would expand in an orderly fashion out of a general base area, and that a transportation service, also under G-4, was not to be a Quartermaster function. War Department manpower agencies had the same impression.

Meanwhile, under USAFBI, on 24 May Chaney established an SOS with Lee commanding. Before the end of May, armed with instructions from the War Department, Lee met with the BOLERO Combined Committee in London, submitting his requirements for U.S. troops either in or about to arrive in the United Kingdom. Using Lee’s estimates, the British planners published their first edition of BOLERO Key Plans. It was a bulletin of instructions, not a directive, to British agencies enabling them to cooperate with Americans in receiving, accommodating, and maintaining U.S. troops. Unfortunately, until mid-June, most SOS special staff officers did not see the first Key Plan. This all-important document pinned down previous rough estimates and stated that 1,049,000 troops and their supplies would arrive, before D-day, tentatively set for 1 April 1943. It gave Lee a manpower ceiling of 277,000 SOS troops, including a Quartermaster quota of 53,226 men. Of this quota, 1,386 officers and 11,822 enlisted men, as casuals or non-Table-of-Organization personnel, were scheduled for headquarters and depot duty. Quartermaster personnel would be 19 percent of the SOS troop strength, or 5.1 percent of BOLERO’S total troop basis, a proportion reminiscent of World War I experience.

On 5 June 1942 there were 36,178 troops in the United Kingdom, of whom 4,305 were in England, the remainder in Northern Ireland. Three days later the European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army (ETOUSA), was formally established, and the same day, 8 June 1942, atop a “cracker box” in Number 1, Great Cumberland Place, London, in the presence of one other Quartermaster officer, Lt. Col. Michael H. Zwicker, Littlejohn activated the Office of the Chief Quartermaster, ETOUSA. Within five days, while retaining his planning role in Headquarters, ETO, Littlejohn also became Chief, Quartermaster Service, a planning as well as an operating post within General Lee’s SOS ETOUSA. Thus, when Maj. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower succeeded Chaney as theater commander on 24 June both a Chief Quartermaster, ETO, and a Chief,

Quartermaster Service, SOS, were in existence. Both positions were in the hands of one general officer.8 The history of the Quartermaster support mission in the United Kingdom and later in northwest Europe is largely bound to the fortunes of SOS ETOUSA and its successive commands. Likewise, the Quartermaster story is linked to the officer, who, in June 1942, was named to head it.

Organizing for BOLERO

In the formative period of the ETO staff it would be an error to regard the Chief Quartermaster (CQM) solely in terms of his official position and duties. The personality of a particular incumbent, QMC field doctrine and tradition or lack of them, and the logistical environment of a major military operation constantly interact to make the functioning staff officer different from the legal one. Born in October 1890, a South Carolinian, General Littlejohn, although more than fifty years of age, was notably self-reliant, active, and robust. Graduating from West Point in 1912, he served two years in the Cavalry before being detailed to the Quartermaster Corps. In France, duty with Brig. Gen. Harry L. Rogers gave him quartermaster experience at the highest field level. Over the next two decades his assignments at depots, service schools, on the War Department General Staff, in the Philippines, and in the OQMG provided further rich experience. His interests and tastes were logistical in the broadest sense and were not narrowly confined to quartermaster detail. His last assignment before going overseas was as Chief, Clothing and Equipage Division, OQMG.

In the interwar period Littlejohn had spent considerable time in analyzing records and compiling dry-as-dust details about “pounds per man per day” and “square feet per man per day,” weight and cube factors—all of which lay at the very basis of any logistical system. Though Quartermaster Corps archives provided little information, he gathered valuable data concerning World War I through correspondence and interviews with Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, former G-4, First Army, AEF, and later The Quartermaster General, and with Col. Martin C. Shallenberger, aide to General Pershing.9 When he arrived in London on 4 June 1942, Littlejohn’s first task, apart from drafting BOLERO Quartermaster plans, was to set up the Office of the Chief Quartermaster and prepare to deploy QMC personnel throughout an island base with particular attention to southwestern England.

In beginning work, Littlejohn took note of Lee’s early dictum that SOS should figure computations broadly and boldly, always bearing in mind the .big picture of ultimate objectives. Fortunately, to get a focus on any size of picture Lee might have had in mind, Littlejohn frequently consulted one of the rare copies, which he later discovered was the only one around the London headquarters, of Pershing’s SOS record. Since few

SOS officers had had war experience, the volume became a valuable reference tool. As Littlejohn reflected on his organization, his gaze was fixed on the troop basis for Quartermaster Service, including recommendations for the procurement and the use of authorized T/O units and their immediate allotment to projected SOS subcommands. His estimate of manpower needed for such units, known as T/O personnel, like the one for casual or non-T/O personnel who would man SOS agencies and staffs, was at best an educated guess. It was still not clear just how the support command was to operate.

Before leaving the United States Littlejohn had examined Lee’s staff chart. It reassigned two important functions traditionally performed by the Quartermaster. A general depot service and a motor transport service would operate under G-4, SOS, direction. On 23 May, The Adjutant General, War Department, had approved Littlejohn’s request for 21 officers as non-T/O personnel to staff the Quartermaster Section of a general depot. As casuals, 9 senior officers were earmarked as division chiefs in OCQM. But Littlejohn persuaded Lee to allot him 25 more officers with the understanding that a total of 58 officers would be present in OCQM by the end of 1942. Littlejohn also asked The Quartermaster General, Maj. Gen. Edmund B. Gregory, to allot OCQM 50 junior officers for future service. Such a reserve would remain in training in the United States, becoming conversant with salvage problems, protective clothing, and storage and distribution procedures of Class I and II supply. Consistent with his idea of working directly with Gregory’s office during this formative period, Littlejohn left Col. James C. Longino in charge of OCQM’s rear echelon in the United States in order to expedite personnel and supply. Though 44 officers were to have sailed with Littlejohn on 28 May, only one QMC officer actually accompanied him.10

Believing that his hand-picked staff would soon arrive, Littlejohn, who never hesitated to get his concepts down on paper, drafted his first organizational chart for OCQM on 8 June. Colonel Middleswart, designated as Deputy Chief Quartermaster, joined the special staff of Headquarters, ETOUSA, where strategic planning for ROUNDUP was centralized. The OCQM itself was to comprise ten divisions, organized mainly on the commodity lines recently discarded by the OQMG in Washington.11 There was considerable justification for such conservatism in an overseas headquarters, where quartermasters attempting to operate in an unfamiliar environment obtained helpful guidance from familiar organizational concepts. The overseas organization was well suited to its original mission, and included one purely functional subagency, the Procurement Division, which reflected the actualities of operating in a friendly foreign country. Under those circumstances, local procurement was largely a matter of intergovernmental liaison, and not a function that could be handled conveniently on a commodity basis.

After 5 June as he talked more and more with General Lee, Littlejohn found that the depot plan which had been conceived in Washington in mid-May was outmoded. To avoid unnecessary construction, a large number of small depots already in existence in England would have to be operated in support of scattered troop stations, each of which would also require a post quartermaster system. Littlejohn had envisaged large quartermaster installations at major ports, but these were already too crowded. In addition, Lee stressed the point that the British would soon release depot facilities throughout southern England, not in the Midlands, in accordance with an elaborate plan worked out by Maj. Gen. Richard M. Wooten, the British Deputy Quartermaster General (Liaison). This news nullified Littlejohn’s current personnel requests in the Office of The Quartermaster General. The speed with which Lee wanted his American staff to accept the British offers, plus the fact that SOS had only a vague notion as to where BOLERO’S troops were to be concentrated, suggested that Littlejohn’s manpower estimates were obsolete before he placed them on paper.

Working under these adverse conditions, Littlejohn instructed his future staff to initiate a series of studies on sundry quartermaster topics and to contact British ministries on retail matters. On 12 June he personally drafted BOLERO’S detailed supply requirements. This was a difficult assignment. He had few QMC manuals at hand to work out basic logistical data and he therefore started to develop his own body of BOLERO manuals. Other staff studies estimated the local scene, noting all the prospective changes which OCQM would have to make in taking over quartermaster responsibilities from the British. Another study concerned the depot system or lack of it.

Confronted with a need for more and more studies and with no one to make them, Littlejohn looked to the whereabouts of his missing staff. With Lee’s approval, he rushed off a message to Gregory for 400 officers, all of whom were expected before the end of 1942. This request was in addition to the fifty-eight officers whom Lee had already approved.12 Summarizing his reactions to the local scene after a fortnight in England, Littlejohn wrote to the Deputy Quartermaster General:

... If one were given the job of organizing, from the Quartermaster angle, one half of the continental United States and at the same time creating a central office paralleling to a large extent the Office of the Quartermaster General a picture of the problem here would become apparent. ... In a way I was rather unfortunate in not having moved into the European problem at the time the other individuals did. As a matter of fact, I believe I was the last to come on the scene. This forced me to depart from the United States without a thorough study of the personnel and supply problems and without having set up the necessary plans to make this end operate. ... The minute I arrived various echelons expected me to start going full blast on every class of supplies in every direction. Actually, for a period of a week Zwicker and I had one desk between us, no typewriters and no clerks. ... Within a few days I hope to dig into and straighten out the flow of supplies. Theoretically the troops are expected to

?come into this area with sixty or ninety days supply. From this end the claim is that these supplies are not arriving.13

On 17 June Littlejohn submitted the first of a series of BOLERO Quartermaster plans to G-4, SOS.14 In brief, its features of necessity appeared to be three-fourths British, one-quarter American, but the plan’s tone suggested Quartermaster Service would become more American after the inauguration of a sound depot system. As he pondered over his supply plan, talked repeatedly to British colleagues, made trips to the field, and read the initial offerings of his arriving staff officers, Littlejohn’s views on what he needed began to change and jell. His desire to apply his talents to the new and unorganized SOS, and the need to move sharply away from dependence on the British in an area where the Americans had not anticipated any large-scale troop concentrations, were powerful incentives in moving him to repeat his argument to General Gregory on the urgent need for 400 more QMC officers. The situation was aggravated by the fact that the Motor Transport Service and the General Depot Service in the ETO, neither of which was any longer connected with the Quartermaster Corps, had arranged to have considerable numbers of QMC officers assigned to them. Feeling that his previous requests for personnel had been evaded, Littlejohn on 26 June wrote to The Quartermaster General with some indignation:

I have been on the receiving end of the most definite “run-around” that I have ever known. ... In discussing personnel matters with the other services I find an eagerness on the part of the Home Office to solve the problems in the field. Take the Ordnance Department for example. The Chief Ordnance Officer here was furnished with every man he asked for by name. He arrives with his staff consisting of all regular Colonels and all graduates of the Military Academy. I arrive with one Lieut. Colonel of the Regular Army and two Colonels of the Regular Army assigned but not arrived ... All I ask for is my fair share of the good personnel—no more, no less. ...15

At the end of June there were fifty casual QMC officers in the United Kingdom but only seventeen were in OCQM; the remainder had been attached to expanding SOS staffs. During the same period the arrival of T/O personnel in Quartermaster units was so slow that arranging for their reception was a very minor burden on the OCQM. At the end of June there were only seven such units in the British Isles, comprising less than 500 officers and men, mostly occupied in supporting the Eighth Air Force. The Personnel Division of the OCQM was preoccupied with plans for the somewhat distant future. It had computed the Quartermaster quota of 53,266 men for BOLERO already mentioned, basing this requirement upon the following detailed breakdown:16

| Type of Unit | Number of Units | Total Strength |

| Total | 163 | 53,226 |

| Service Battalion | 14 | 13,188 |

| Bakery Company | 16 | 2,608 |

| Graves Registration Company | 7 | 945 |

| Shoe and Textile Repair Company (M) | 19 | 3,838 |

| Type of Unit | Number of Units | Total Strength |

| Salvage Depot, Headquarters | 2 | 414 |

| Laundry Company | 24 | 7,224 |

| Sterilization and Bath Company | 8 | 1,352 |

| Salvage Collecting Company | 6 | 1,230 |

| Railhead Company | 35 | 4,060 |

| Depot Supply Company | 24 | 3,648 |

| Sales Commissary Company | 3 | 615 |

| Refrigeration Company | 2 | 476 |

| Refrigeration Company (M) | 3 | 420 |

| QM Service, Headquarters and Depot Overhead | 13,208 |

In the summer of 1942 Littlejohn appeared to be planning and operating in a vacuum, at times working unwittingly at cross-purposes with the shifting designs of logisticians and authors of grand strategy. He told his officers that his sins would be sins of commission, not omission. He wrote frequent, brief memorandums to his staff, giving them one distinct impression—that OCQM could expect, by running hard, just barely to stay in place. Without warning, G-4, SOS, on 14 July 1942 emphasized his point with the announcement that the Quartermaster BOLERO quota was being cut to 39,000 men. No explanations were given. Immediately, OCQM drafted tables for Lee, indicating how BOLERO and ROUNDUP might suffer if the 14,000-man reduction took place. At the time Lee was sympathetic, but only President Roosevelt and his service advisers could explain all cuts in BOLERO. Throughout July the slowing down of troop arrivals discouraged OCQM. Early in August 2,438 Quartermaster troops in sixteen T/O units were present for a force of 82,000 men,17 a ratio which Littlejohn considered far from ideal.

One aspect of the personnel problem showed a slight improvement. Competition for high-caliber supply personnel, as casuals, had intensified during the early summer of 1942 as Lee pushed his G-4 operation of the General Depot Service and the Motor Transport Service. A portion of this manpower was returned to the Quartermaster Service after Lee, following the lead of the War Department, abolished the General Depot Service in mid-August.18 In the process Col. Turner R. Sharp, former Chief, General Depot Service, became a division chief within OCQM. But another need for additional personnel arose when Headquarters, SOS ETOUSA, moved to Cheltenham, a spa about ninety miles west of London. Two Quartermaster staffs came into existence, forcing Littlejohn to keep his deputy, Colonel Middleswart, on the staff of ETOUSA, and to separate the efforts of his BOLERO and ROUNDUP planners.19

By mid-July the organizational changes within SOS once again upset the OCQM’s manpower estimates. Now its plans had to cover support of from fifteen to eighteen divisional areas and four corps areas as well as provide for items of common use for the expanding Eighth Air Force.

A minimum of fifteen general depots each with a Quartermaster Section had to be manned. Each divisional area, post, camp, and station required a post quartermaster system. Behind each corps area a base section was needed, calling for additional Quartermaster staffs and operational units. Four projected base sections would contain a total of fifty quartermaster branch depots and within each base section, districts would be marked off, requiring still more quartermasters in each SOS subdivision. At station hospitals a full Quartermaster complement was needed.20

The dimensions of this projected organization moved Littlejohn to revise upward every troop basis. Still preferring to solve his problems through the informal and unofficial QMC channel rather than effect solutions along command lines, Littlejohn addressed several more messages to Gregory. Gregory’s reply of 10 July said in part “... I hope you will consider in your requirements for officers the whole Quartermaster picture. We have to supply Quartermasters to units all over the world. ... I hope you will not ask for more officers than you need or faster than you need them. As I understand, we have sent you about 151 and are about to send you 150 more at once. This is a much higher proportion than is present in any other theater. ...” This sort of answer was quite unsatisfactory to Littlejohn, and he tried to get Gregory to visit the European theater.21 Failing in this, the Chief Quartermaster then redefined his manpower requirements as an official demand, and forwarded it to Somervell through Lee, who approved it without change on 31 July 1942. Quartermaster needs for casual personnel as of 1 April 1943 were summarized as 875 officers, 30 warrant officers, and 2,178 enlisted men, or a total of 3,083. OCQM itself required a strength of 315, including 100 officers.22

When OCQM moved to Cheltenham between 9 and 13 July 1942, it consisted of 13 officers, 21 enlisted men, and 16 British civilians, the latter performing clerical work. Operating OCQM on a 12-to 18-hour schedule after 22 July, Littlejohn, who had held Sunday morning conferences in London, now initiated a series of daily seminars among his key officers, opened a map room, and posted the quartermaster situation daily. As officers joined OCQM, they assembled essential planning data in notebooks. An initial assignment called for a geographic survey of their island base. Fledgling quartermasters, many fresh from the world of trade, studied standard logistical works dating back to World War I. Lists of British supply nomenclature and glossaries were compiled so that ignorance would not result in an uneconomical use of shipping space. For example, garbage cans were “dust bins” in Great Britain, and requirements and requisitions had to be so labeled. It was weeks before War Department circulars and technical

literature reached Cheltenham or London, and OCQM was therefore forced to formulate its own supply procedures and circulate them throughout the command.

Despite his practice of keeping in close touch with his subordinates’ progress, Littlejohn continued to have difficulty getting the right man for the right job. Initially, many so-called experts reached Cheltenham, but not enough with the proper qualifications. Several requested reassignment after struggling with their unfamiliar duties. On the other hand career quartermasters grasped the scope of their responsibilities. As Executive Officer, OCQM, Col. Beny Rosaler, who was in his element in straightening out administrative confusion, supervised the work of briefing the command on Quartermaster procedure. In supply matters, Col. Turner R. Sharp (Depot Division, OCQM), Col. Oliver E. Cound (Stock Control Division, OCQM) and Lt. Col. Robert F. Carter (Subsistence Division, OCQM) indoctrinated reservists. Col. Aloysius M. Brumbaugh, chief of the Supply Division, himself a Reserve officer but one with much experience, also contributed to on-the-job training. The Germans unwittingly made their contribution. Many a young Quartermaster lieutenant fresh from Camp Lee, working late at night on requisitions or other essential staff actions, was rudely interrupted by the urgent need to take shelter. This type of realism accelerated training and produced capable officers just when they were required. Inasmuch as senior quartermasters were needed for depot commands, Littlejohn demanded that junior grade officers assume more of the staff load.23

By 8 August, 68 officers and 86 enlisted men were in OCQM and Littlejohn felt better about his staff situation. Now OCQM comprised 14 divisions broken down into 59 branches. The Executive Division administered the OCQM; the others developed policy and procedure, planned projects, and supervised or coordinated operations throughout an expanding SOS. The need to supervise and control increasingly decentralized field operations accounted for most of the organizational changes in the OCQM made since June 1942. To tie OCQM closer together, Littlejohn required each officer and branch to make a continuous study of Quartermaster reference data. Early in September eight studies on this subject were prepared and distributed.24

An early study grew out of Quartermaster troop planning for a “type” force of 600,000 men.25 In mid-August ETOUSA asked OCQM to estimate the support for a type force containing a GHQ, 2 armies of 6 corps, and 16

divisions, of which 7 would be triangular infantry divisions, 2 mechanized, 5 armored, and 2 airborne. In retrospect, such planning was academic during this period of watchful waiting. But in response to a G-4 request of 30 August, OCQM related its troop planning and supply support to a new concept. To meet the G-4 request calling for support to a type army of 300,000 men, OCQM hit upon the idea of tabulating troop units by Tables of Organization and Equipment and aggregate strength in proper balance to give maximum support to a type corps.26 Known later as the 100,000-man plan, this was an important study in percentages and proportions. Continuously refined and revised to meet foreseeable conditions within a typical force under conditions consistent with current plans, this tabulation gave staffs at all echelons a simple arithmetical device for fitting a Quartermaster troop basis into any multiple of 100,000 men. As a reference tool, often used together with supply data, the 100,000-man plan was immediately accepted and applied by commanders to future operations.27

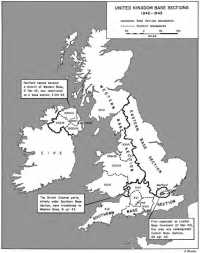

The OCQM structure at the beginning of August reflected its growing activities within an expanding SOS. On 20 July 1942 Lee had announced SOS regional subcommands wherein Quartermaster operations were to be decentralized. The projected four corps build-up was approaching reality as Headquarters, II Corps, now arriving in England, joined Headquarters, V Corps, late in July. With boundaries that closely corresponded to those of British administrative commands, four SOS base sections with respective headquarters were constituted as follows: Northern Ireland Base Command (Belfast); Western Base Section (Chester); Eastern Base Section (Watford); and Southern Base Section (Wilton).28 (Map 1) On 7 August, five general depots, Burton-on-Trent, Thatcham, Ashchurch, Bristol, and Taunton, and three Quartermaster branch depots, Wellingborough, Kettering, and London, were in operation.29

As Chief Quartermaster, Littlejohn had authority to supervise and control technical matters at all echelons. Within the base sections and their respective depots, he recommended the selection and placement of Quartermaster supply officers. On the other hand each base section commander controlled operations within his own area. Thus, as in World War I, the overlapping of command and staff responsibilities produced a host of nagging conflicts as depot commanders, usually colonels of the Quartermaster Corps, were caught between OCQM’s instructions and the base section commander’s orders. One early conflict was of a serious nature, involving the primary mission of the Quartermaster Corps. The case in point developed in Southern Base Section where the commander, Col. Charles 0. Thrasher, set arbitrary levels of supply. To OCQM, this action made the retail aspect of supply of greater importance than the wholesale, and threatened the whole carefully organized

Map 1: United Kingdom Base Sections 1942–1943

stock control system with anarchy. If continued, the policy would mean the depletion of stocks being stored for combat at a future date, and deprive the OCQM of control over theater supply levels. Littlejohn had the policy set aside through Lee’s personal intervention, and, working through the base section Quartermaster staff, retained the authority to set supply levels.30

An early depot problem concerned British civilian workers. For BOLERO, Littlejohn estimated he would need 12,000 local citizens to fill clerical, supervisory, and laboring jobs. Because British laws were complex and little understood by Americans, civilians were paid and administered by the British War Office. Yet problems over wages, hours, quarters, and conditions of employment soon developed and Littlejohn himself often attended to them. In July 1942 the Chief Quartermaster personally satisfied the charwomen of Cheltenham with a tea and milk ration, and they stayed on his payroll. On occasion, he was able to attract and hold competent civilians by the simple device of giving them the substantial U.S. ration.31

Quartermaster depot and service troops created additional problems. The first to arrive were only partially trained in their specialties. Moreover, when they should have been at their regular duties they had to spend precious time mastering their weapons and the manual of arms, since this type of training was also incomplete. Littlejohn deplored the personnel policy which assigned to the QMC enlisted men who were predominantly of inferior intelligence or deficient education, or both. Many of the depot companies and practically all of the service battalions were composed of Negro troops with low Army General Classification Test (AGCT) grades. These units were not representative of Negroes in the Army. Irrespective of color, the number of men who were suitable candidates for commissions, or even for promotion to noncommissioned officers was far too low. Under hastily trained and completely inexperienced young white officers, these troops did not perform very well. The British attitude of friendly tolerance toward all foreigners, regardless of color, surprised both officers and men, and probably aggravated the disciplinary problems in these units. Littlejohn was inclined to lay most of the blame on the officers. He was alarmed to find that even many of the service battalion commanders were lacking in field experience, and he had to devote considerable time to finding competent commanders for these units—something which, he believed, should have been accomplished before they were allowed to leave the zone of interior.32

In addition to coping constantly with problems of decentralization, by mid-July 1942 Littlejohn found himself coordinating more and more jobs with adjacent and higher headquarters. In London, he kept in touch with Middleswart’s planning on ROUNDUP. At Cheltenham he worked with SOS boards of officers, committees, schools, and other chiefs of services. After its creation in late June, Littlejohn became the Quartermaster member on the SOS General Purchasing Board, which set policy for matters of local procurement. The board operated under a General Purchasing Agent, Col. Douglas B. Mackeachie. Littlejohn designated Col. Wayne R. Allen, who had had rich administrative experience as an executive of Los Angeles County, California, as his procurement specialist, and later appointed him to the board. Allen’s job called for the highest type of coordination, and upon Mackeachie’s return to the United States for an important assignment at the end of 1942, Allen became the General Purchasing Agent, a promotion which suggests the high quality of his quartermaster activities.33

Centralization of control touched other Quartermaster fields. Littlejohn’s Class III responsibilities made him a member of the Area Petroleum Board, headed by an area POL officer, whose job it was to coordinate requirements among the Army, Navy, and Air Forces within the theater. To train all sorts of technical specialists, SOS opened the American School Center at Shrivenham, England. Littlejohn added a school course for cooks and bakers on 8 September. Lack of instructors kept OCQM’s initial contribution from extending to mess management and food service. These classes were begun later in the year, and Littlejohn also started field courses for bakery platoons at Tidworth.34

Having taken over the General Depot Service from G-4, SOS, OCQM acquired additional duties, when, on 19 August 1942, it assumed control of the Army Exchange Service, first of its planning activities, and later of its operations. In the summer of 1942 this was a logical arrangement because OCQM was far advanced in procuring local Army Exchange Service items, had depot facilities, and understood issue problems. Lacking issue clerks, OCQM initially proposed to operate a canteen service, combining the operational features of a sales commissary and a post exchange. On 30 August Littlejohn brought Col. Edmund N. Barnum and his former Army Exchange Service staff to Cheltenham, incorporated them as a division in OCQM, and planned to send mobile sales stores to troop stations.35

Mid-September found the Chief Quartermaster hoping that he could devote more and more time to developing Lee’s plans, turning details over to his division chiefs and leaving operations to base and depot quartermasters. Much of the organizational confusion of the past summer was subsiding. With emphasis on

BOLERO instead of ROUNDUP, SOS was expanding rapidly and Littlejohn’s colleagues greatly respected the leading role he had played in its development. Momentarily it appeared that his own days of orientation and improvisation were over. He had tried to eliminate defects in his organization, to create a body of Quartermaster literature to fit BOLERO, and to keep his supply planning up to date.36

Supply Planning for BOLERO

The authors of BOLERO in spring 1942 had made only a tentative and hurried investigation of the complex supply situation which faced OCQM. In the summer of 1942 the major problems of OCQM arose from a shortage of storage space and from the promise of a surplus of shipping which never materialized. To overcome these obstacles, considerable spadework had to be done. Quartermaster supply planning after 8 June 1942 was closely meshed with that of other staffs at all levels, and influence did not always flow down from the upper staff levels to OCQM. Concurrence, often accompanied by correction of detail and by clarification of missions, came from Littlejohn’s staff. With only a few of his division chiefs available, he presented his first supply plan to G-4, SOS, on 17 June 1942. The plan suggests that he had carefully reviewed the BOLERO Key Plans and had attempted to keep abreast of Lee’s planning.37

OCQM’s plan conformed to four estimates which BOLERO planners had outlined late in May.38 These included estimates of the troop basis for BOLERO, the composition of the force including the priority in which the units were to arrive, the tentative shipping schedule, and the preparations which the British and Americans were making for the reception and accommodation of BOLERO troops and cargo. As bulletins of information, the Key Plans of summer, 1942—a second edition would be published on 25 July to reflect the situation at the end of June 1942—had anticipated remarkably well what OCQM’s requirements and problems of procurement, storage, and distribution would be.

BOLERO operated on certain assumptions which conditioned Littlejohn’s first draft plan. As strategists had studied invasion plans for ROUNDUP, they agreed that U.S. troops should take the right of the line, the British the left. Logically, this placed the Quartermaster build-up in southwestern England, or on the right of the line as BOLERO troops faced the Continent. Although cargo and a few troops had begun to arrive in the ports on the Clyde and the Mersey, the earliest depots had been located inland from the Bristol Channel. It was logical to continue and expand this deployment of men and their resources. Another assumption was based on the steady growth of the Quartermaster Service. The British were gradually to relinquish their responsibilities toward the Americans as the latter demonstrated that they could handle their own services of supply. While be recognized that the build-up phase would be governed by tactical requirements, Littlejohn planned to concentrate on BOLERO first, and then on

ROUNDUP. This meant that during the summer of 1942, the Chief Quartermaster might have some time, at least, in which to develop first his organization, next his levels of supply, and then his services.39

In terms of his daily wholesale and retail mission, Littlejohn entered a vast unplanned area in summer 1942. His task was to reduce his requirements to a simple expression, namely, pounds of quartermaster supply per man per day. This was difficult to compute because the basic Tables of Organization and Equipment were often not available, were obsolete, were constantly being modified, or were little understood by his freshmen planners. Ultimately, after hundreds of man-hours of tedious work, the estimated gross weight factor appeared to stand steady at 27 pounds per man per day, broken down by class of supply as follows: food, 6 pounds; clothing and equipment, soap, and other expendables, 1½ pounds; petroleum products, 15 pounds; solid fuels, 3½ pounds; and miscellaneous items such as post exchange and sales store items, 1 pound. By multiplying these factors by the number of men involved, Littlejohn could estimate his requirements for a day of supply for the entire ROUNDUP force.

Concurrently OCQM worked out its space requirements as the basis of a storage and distribution system. These factors expressed supply in terms of square feet per man per day. Then both space and weight factors were neatly arranged in tables, ready for the day when supplies rolled in. Late in June OCQM began to requisition its Class II and IV supply from the United States, to explore what could be procured locally, and to locate storage.40

The scene of Quartermaster BOLERO activities, the United Kingdom, was 3,200 nautical miles from Littlejohn’s port of embarkation, New York City. The round trip to Bristol Channel ports took forty days for troop ships and sixty days for cargo vessels. Class I and III supplies, automatically issued, and Class II and IV supplies, periodically requisitioned, would come from the New York Port of Embarkation (NYPE). The plan complied with earlier directives that everything possible would be procured locally, and it was in line with the War Department’s announced objective of January 1942 to set a 60-day level for Quartermaster supply in the United Kingdom. This objective was revised on 6 July to give zone of interior port commanders more authority in the logistical system, and to set up an additional 15-day cushion of supply. Littlejohn had anticipated this action, and his first Class II and IV requisitions, submitted early in July, recommended the higher levels. Littlejohn’s memorandum expressed the hope that the 75-day levels could be reached before the end of September. Thereafter, he proposed to maintain BOLERO stocks by securing shipments for both maintenance and reserve in accordance with troop arrivals within a given month.41

To bring Quartermaster supply to the prescribed levels, the War Department had delegated to the Army Service Forces authority to approve overseas allowances,

name the ports of embarkation, place representatives of ASF and of each technical service at the New York Port of Embarkation, provide shipping, and announce policy for port commanders.42 The New York port commander, with clearer authority after 6 July, controlled the flow of Quartermaster supply, effected automatic issue, filled requisitions, and recommended through ASF to OQMG the minimum reserves to be held at the port and amounts to be stocked in inland depots. The NYPE commander also controlled scarce shipping, edited requisitions, and served as a link between Little-john’s staff and Gregory’s office.

In the United Kingdom OCQM effected distribution by coordination with SOS transportation agencies. Early in its history, OCQM insisted that manifests reach its officers in advance so that, where practicable, storage and distribution could be planned ahead. Quartermaster requisitions were submitted through G-4, SOS, to NYPE by class of supply. Special needs, supply shortages, and other difficulties were reported in the same way. Notwithstanding the absence of a depot system in the summer of 1942, Littlejohn prepared a plan requiring his mythical depot supply officers to report weekly stock levels. To receive rations, organizations had to present strength returns, preferably consolidated at divisional level, and at the time of its writing, Littlejohn’s plan envisaged the receipt of eighteen divisional reports. He had devised a new requisition form for use as a voucher, and desired each division to consolidate all requisitions to facilitate supply.

Local commanders and Quartermaster supply officers in general depots were to be authorized to sign certificates of expenditure for property to the value of $100.00. Chiefs of technical services would be authorized to approve certificates when the value did not exceed $5,000.00. In regard to local procurement procedure, Littlejohn suggested that he would furnish an estimate of Quartermaster requirements every six months in advance to the general purchasing agent, and report actual needs on a quarterly basis. Whenever practicable, he proposed to decentralize Quartermaster purchasing to depots, camps, posts, and stations.

The first ration plan for BOLERO, which had to conform to the 75-day levels set by the War Department, provided for a field ration at a 55-day level and an operational ration at a 20-day level.43 The British-American ration, announced on 29 May, was to remain in effect and was to be supplemented by each combat division and air unit through the local procurement of foodstuffs. OCQM had no choice in this planning step, and always considered it tentative as subsistence experts at Cheltenham went about placing all U.S. troops on a type A field ration. Early in July 1942, OCQM championed the cause of outdoor manual workers, increasing their ration by 15 percent. They required more nourishment than the 4,070 calories of the British-American ration.

The 17 June plan announced, meanwhile, that the 20-day level for operational rations was to be broken down into a 17-day stockage of type C or K, and a 3-day level for the D ration. The distribution plan called for the troops to keep

with them a day’s D ration, a week’s C or K type, and two days of the B ration. In forward areas there was to be a month’s supply, of which to days, as noted above, was in the troops’ hands. It is interesting to note that this distribution plan for operational rations was to influence greatly what the soldiers soon carried ashore in their first amphibious operation, that against North Africa. In reserve depots, a 45-day level was to be held. Aware that the British controlled all cold storage space, Littlejohn estimated that his requirement for refrigerated reserve foods would be a minimum of 30 days. With his subsistence needs on paper, and the first shipments on order at NYPE, Littlejohn’s next task was to find storage space for rations.

In the concluding paragraph of his plan Littlejohn asked G-4, SOS, for an early decision on the line of demarcation between the post exchange service and the Quartermaster operation of sales stores. He was not suggesting Quartermaster operation of the post exchange but anticipated confusion if lines of responsibility were not set immediately. OCQM understood that on a wholesale basis it was to procure and store post exchange items, and that the job would be accomplished in line with the retailer’s wishes. Littlejohn had no evidence of what the Army Exchange Service needed, and the troops would demand such services immediately upon arrival. Unfortunately, G-4, SOS, was unable to arrive at any immediate decision. Two months later, OCQM incorporated the Army Exchange Service as a staff section on its roster, as already described.44

On the same day that he submitted his first detailed supply plan, 17 June 1942, Littlejohn set out with General Lee and other SOS officers on a tour of England, including depot sites at Bristol, Exeter, Taunton, Westminster, Thatcham, and Salisbury, all of which later became key Quartermaster installations. During this trip he strengthened his conviction that all field quartermasters must have a “look-see” for themselves on important depot sites instead of accepting observer reports or the British paper offer. Many depots were converted civilian buildings not built for military use and located far from projected troop cantonments. He also saw that quartermaster resources in the United Kingdom were not fully at his disposal. They were controlled in the interests of a global imperial strategy by the British War Office, whose attention as June came to an end was riveted on recent German successes in Libya that endangered British sea power in the eastern Mediterranean.

In attempting to coordinate his own arrangements with the first BOLERO Key Plan, Littlejohn recognized that the British had been as generous as possible in making their resources available. Yet the Key Plan allowed only a glimpse of the real conditions in the United Kingdom. Littlejohn saw that it was not an ideal Quartermaster base.45 The British Isles had supported 48,000,000 people during more than two years of war, including the supreme crisis which Churchill had eloquently proclaimed as “their finest hour,” but the requirements of the U.S. Army weighed down an economy that was already severely and increasingly regimented by a stringent

rationing system. Military service and war industries had claimed most of the available labor supply. The Axis Powers, concentrating on winning the current Battle of the Atlantic, had made Allied shipping a primary target.

As he traveled Littlejohn perceived many of the problems his future planners would have to consider. First, they must acknowledge the position of the British in supporting their own portion of BOLERO and ROUNDUP as well as playing host to American troops. Second, all scales of accommodation would be upset if procurement quartermasters ignored British standards and wastefully prescribed greater comforts for the Americans. Third, quartermasters had to be patient with centralized British administration, conducted through a complex of ministries. And fourth, in deference to British methods and means, American quartermasters had to unlearn or lay aside their training in such things as mass production and thinking in expansive terms. For example, storage experts could not enjoy the advantages of laying large areas of concrete in a minimum amount of time because this technique was not understood in England.

Littlejohn foresaw that in managing depots American officers might be frustrated by a host of little things. One embarrassment might result from voltage variations as quartermasters tried to operate electric power tools and lights. Tools of American design simply refused to fit local plumbing and electrical systems. Lack of time and resources restricted any alterations in British buildings. Along with colleagues in the engineer and transport services, quartermasters had to share all the griefs which British hard subsoil and insular weather heaped upon their construction activities. In looking over the sites which he might eventually inherit from the British, Littlejohn foresaw that his staff could easily misunderstand why the British had divorced their depots from access to water, to transportation sidings, to sewage systems, and, above all, to any logistical blueprint that contemplated an offensive against Hitler’s Europe. Of course, British depots had been dispersed for defensive warfare long before Americans had entered the war.46

Though quartermasters no longer operated a transportation system,. they remained an integral part of BOLERO’S distribution system. Littlejohn noted in June 1942 that the Irish Sea ports were open, but had obsolescent facilities that were not very well prepared to handle the influx of BOLERO’S 1,000,000 men and their supplies in the short space of ten months. He doubted that the rail transport system for clearing the ports could handle the estimated additional monthly burden of 100,000 men and 120 ship cargoes.

As for storage estimates, Littlejohn’s field trip confirmed his belief that his own 9 June figures were much more accurate than the estimates he had received from BOLERO planners upon his arrival in London. They had estimated that SOS would require 15,000,000 square feet of covered storage, including 1,230,000 square feet of shop space. This space, beginning 1 July, was needed at the rate of 1,333,000 square feet a month. Of the total space the Quartermaster share approximated 4,000,000 (gross) square feet,

a figure which Littlejohn’s own slide rule practically tripled.

After his June trip and those of early July the space problem appeared insignificant as compared to the problem of depot location and the condition of the sites. Of necessity, SOS had accepted space for the projected eighteen divisional areas, “in penny postage-stamp size, on a where is, as is” basis. To reach its storage goals many new construction projects were unavoidable unless OCQM was resourceful and uncomplaining. Since there was a critical shortage of construction materials (all lumber would have to be imported) a maximum of ingenuity was clearly indicated. To turn British depots to full account, Littlejohn saw that adroit administration had to be exercised by his depot quartermasters from the beginning.47

A field quartermaster could foresee most of the physical limitations which the BOLERO Key Plans imposed on the formative period of his wholesale support mission, but it was more difficult, and just as important, for him to understand the challenge a million Americans away from home invited to his retail support mission—housekeeping. He had to find ways and means to impress his problems on those at home who had the job of supporting him. Equally important, he had to impress upon the combat troops and their commanders the need for supply discipline and a certain amount of self-denial during the period of waiting in the British Isles.

The characteristic traits of the American soldier, while an asset to the combat commander, constitute a grave problem for the quartermaster. The qualities of individual initiative and ready adaptability that make him a formidable opponent in battle also make him demanding and individualistic in his relations with the supply services. American armies have always been composed of citizen soldiers, very conscious of their status as citizens. With combat experience such veterans develop the competence, but never the point of view of professional soldiers. They will endure the privations, the fatigue, and the serious injuries of war—not silently, but with that minimum of grumbling characteristic of good troops. But they protest vociferously against even minor hardships when not actually engaged in combat. Partly trained and untried soldiers vocalize even more loudly regarding the exposure, hunger, and fatigue that inevitably accompany advanced combat training. It should be remembered that the United Kingdom was a training ground as well as a staging area for U.S. troops.

American soldiers expected to find a large part of their accustomed civilian environment in Great Britain. Quartermasters were expected to supply cigarettes requisitioned by brand name, nickel candy bars, two-piece metal razors, comic books, the latest magazines, and all the peacetime gadgetry of a modern industrial nation. The applied psychology of combat commanders convinced the men that they were the best soldiers in the world and tended to carry with it the conviction that they deserved the best the world had to offer in supplies and services. Many officers appeared to share this conviction. The situation inevitably thrust the role of King Solomon upon the theater quartermaster, who had

to approve some demands, deny others, and then attempt to secure the concurrence and cooperation of all concerned. The Americans shared some, but not all, of Britain’s wartime hardships in 1942, and possibly their presence speeded up an improvement in the local standard of living in the summer of 1943, when the shipping crisis was overcome.48

Normally, Quartermaster operations follow the steps of planning, organization, and logistical preparations. When Littlejohn returned to London at the end of June, all BOLERO phases were abreast. His 17 June plan, his trip, and staff studies by OCQM’s division chiefs began to bear fruit in early July. Ably assisted by Colonel Allen, Littlejohn turned his attention to local procurement in order to save shipping space and money. It was a promising vineyard. Deals ranged from beer to undertaker’s supplies. But each Quartermaster class of supply involved different acceptable standards and OCQM itself had to decide how far it could go in deviating from those standards in order to cooperate with the British. For instance with rations compromises might possibly be reached as long as the substitute foodstuffs complied with U.S. food laws and provided the American soldier with enough calories, minerals, and vitamins to keep him physically fit. English farmers had large surpluses of potatoes and cabbage but a steady diet of these would be monotonous, and, in the long run, injurious.

With Class II supplies there was more latitude in accepting products which could be procured locally. On the other hand clothing specifications and general supplies and organizational equipment were too highly specialized to permit local procurement by a British or British-American committee not familiar with the items’ intended use in the U.S. Army. Once the British had determined there was a capacity to produce U.S. Army requirements (to save transatlantic shipping) and then agreed to produce an item, OCQM was determined to hold the British to the agreement. A companion to his local procurement activities, Littlejohn foresaw, would necessarily be an OCQM research and development program. With it, OCQM could be in a much better position to exploit local facilities, to perfect its own standards, or to entrust OQMG with furthering its field projects.49

Littlejohn’s proposals regarding local procurement were accepted. Colonel Mackeachie would procure and inspect all local supplies, perfect arrangements with designated agents of British ministries or other allied or neutral governments, make arrangements for services and labor, issue regulations, and consolidate SOS purchases. Colonel Allen, as agent for OCQM, was to present Quartermaster estimates to Mackeachie and Lee six months in advance, and detailed requirements quarterly.

On 1 July 1942 Allen submitted his first estimates outlined in eleven broad listings to Littlejohn. The report gave British light industry sources of supply, suggested products of Ireland, Spain, and Portugal for investigation, noted items definitely available, and listed those of doubtful availability which needed

further study by both the British and OCQM. In forwarding Allen’s report to Lee, the CQM remarked that some decisions might be reached immediately, others could drag on for months. Specifically, Littlejohn understood that BOLERO’S camp equipment could be procured from British sources, initially for 250,000 men, and by D-day for the full troop basis. He also reported that locally produced equipment for laundry, shoe repair, and bakery companies was under discussion and test. Shoe repair equipment, he believed, would have to be imported, while trailer-mounted laundry and bakery machinery, if available, might be delivered locally, in limited quantities.50

With many details still to be clarified, the British agreed to furnish from a common pool requirements of frozen pork, lamb, and mutton, and also beans, cereals, National Wheatmeal Flour, potatoes, bread, lard, sugar, syrup, tea, fresh vegetables, and several other foods. Regarding Class II and IV supplies, Allen continued to make considerable progress, having presented orders to British firms for office equipment, furniture, soap, cleaning materials, most camp stores (including a cot and two British blankets per man), all mess gear, and tent poles. Littlejohn told Lee that OCQM intended to recover the issue of the all-wool U.S. blankets, storing them for continental operations.51 In anticipation of assuming responsibility for the supply of common-use items to the Eighth Air Force on 1 August, Littlejohn advised Lt. Col. Lois C. Dill, air force quartermaster, of what he might expect from local sources. Dill drew rations from Kettering and clothing from Wellingborough.52

As summer advanced and shipping space grew scarcer, Littlejohn’s time was almost completely monopolized by local procurement matters. Administrative hitches developed, and procedures had to be established, of which many were not clarified until early 1943. With various economies in mind, meanwhile, on 4 July 1942 OCQM proposed and the British agreed to exchange certain Class I and II items—at first, blankets, wool drawers, and undershirts—before 1 January 1943. On 26 July 1942 the War Department approved the “swap idea,” but within a week reversed the policy, holding that items would only be procured on a reverse lend-lease basis. Littlejohn asked Lee to have Somervell reinstate the exchange agreements, especially on food. The British previously had given assurances that components of the recently announced type A field ration (July 1942) could be furnished locally with the possible exception of pork, cheese, evaporated milk, and dried beans. At three-month intervals, both parties would consider issues from the British reserve of foodstuffs.

On 17 September Somervell reaffirmed his original instructions, namely, that local resources were to be exploited to the maximum extent, with reverse lend-lease still to be the basis for the program. Such supplies had to conform with standard American equipment or

comply with U.S. food laws. Foodstuffs and Class II and IV items had to be handled in a simple, direct fashion, remaining under the complete control of Eisenhower. Somervell granted Littlejohn authority to procure (1) food for which no replacement to British stocks was necessary; (2) food whose packaging or processing would appreciably increase cargo tonnage; (3) emergency food, even though replacement was necessary; and (4) perishable food, requiring replacement, which would spoil if unused. Somervell also wanted clearly defined procedures to be established between the British Ministry of Food and OCQM. He said that food, to be replaced by the War Department, would be requisitioned. OCQM continued to procure locally from the NAAFI a wide variety of vegetables, fruits, and condiments.53 The 17 September directive now cleared the way for Littlejohn to continue negotiations with the British but in the autumn months of 1942 the OCQM found itself confronted with many administrative bottlenecks, involving conditions of purchase, communication channels, and British standards.

Local procurement appeared particularly promising in POL supply. When Littlejohn began to analyze ROUNDUP in detail, he noted on 17 July that the initial invasion plans called for 5-gallon gasoline cans. The assault phase required 6,000,000 cans, of which 400,000 were for water. On 29 July, Mackeachie ordered 50,000 cans from NYPE and enough prefabricated parts to assemble 500,000 more each month prior to D-day in the United Kingdom. The War Department replied that it would ship one million complete units as a reserve, and also the machinery for assembling the prefabricated cans. As part of his July 1942 procurement program Littlejohn sought a British plant to house the American machinery, which was scheduled to arrive in two months. In November 1942, the War Department for strategic reasons decided to defer this shipment and continued to ship a modest number of cans from the United States. The can assembly project was not revived until early 1943.54

Deliveries from OCQM’s local procurement activities in 1942 totaled 184,822 dead-weight long tons and represented a saving in shipping space of 259,334 measurement tons (40 cubic feet per measurement ton), broken down by class of supply as follows:55

| Class of Supply | Long Tons | Measurement Tons |

| Total | 184,822 | 259,334 |

| I | 57,707 | 93,579 |

| II | 2,825 | 15,930 |

| III | 113,863 | 128,905 |

| IV | 10,427 | 20,920 |

TORCH Interrupts BOLERO’s Quartermasters

Events far from the British Isles compromised Littlejohn’s first Quartermaster plan of 17 June, as well as his later ones of July and August which had grown out of its details. But to its authors, the framing of a detailed Quartermaster plan for BOLERO was an

experience as valuable to Littlejohn’s new Quartermaster staff as a maneuver is to a tactician. Before June had expired, planners were fashioning a Mediterranean strategy, presenting BOLERO quartermasters with a serious rival for resources. In fact, the attack in the western Mediterranean could have meant the end of BOLERO preparations but as a result of a series of compromises the basic plan of BOLERO was preserved, although momentarily suspended. By 25 July 1942 Operation TORCH had been tentatively outlined. Early in August, Allied Force Headquarters (AFHQ) was constituted and General Eisenhower was formally designated Commander in Chief, Allied Expeditionary Force. His Allied staff, meeting at Norfolk House, London, had selected the TORCH objectives before the end of August. By 5 September the tactical phases of planning ended, the mounting phases commenced, and D-day, early in November, had been set.56

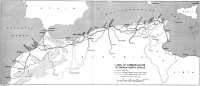

The TORCH strategic plan, on which the logistical plan necessarily had to be based, consisted of a three-pronged assault against French North Africa. In the center of the 800-mile coastal front, landings were to be made against Oran, on the Mediterranean coast of Algeria. (Map 2) On the extreme east flank, after rejecting Tunis or Bone because of the fear of overextending themselves, TORCH planners selected the port of Algiers. A third landing was to be made in the west, near Casablanca on the Atlantic coast in French Morocco. Since Generalissimo Francisco Franco’s attitude was uncertain, this western landing would place a force along the borders of Spanish Morocco to ensure control of the Strait of Gibraltar and the railroad from Casablanca to Oran, and to improve the security of the whole North African coast. By effecting a speedy junction of the three forces, AFHQ might create a favorable opportunity for an early capture of distant Tunisia.57

Lucid though it was, the TORCH plan became increasingly difficult to carry out. By mid-September a Center and an Eastern Task Force, bound for Oran and Algiers respectively, entered their mounting stage in the United Kingdom. Simultaneously, the Western Task Force, with Maj. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., commanding, was being readied in the United States and moved to the Moroccan beaches.58 From the United Kingdom, AFHQ estimated that between 102,000 and 122,000 Allied troops would leave over a two months’ span. Of this number, 40,000 men comprised the assault force, broken down into regimental combat teams and an armored combat command, plus supporting troops. The D plus 3 convoy was to follow with 21,000 troops. Drawing from the 1st and 34th Infantry Divisions of II Corps already in England, plus the 1st Armored

Map 2: Lines of communication in French North Africa

Division, yet to arrive, Eisenhower organized Center Task Force, Maj. Gen. Lloyd R. Fredendall commanding, and Eastern Task Force. Maj. Gen. Charles W. Ryder commanded the assault force of the Algiers operation.59

Apart from the assault phase, AFHQ looked ahead to the time when the task forces would regroup into conventional units, coupled with air and service support. Accordingly, planners assumed that there would be an American field army of seven U.S. divisions (later the Fifth Army), a new air force, the Twelfth, and two base sections to be known as Atlantic and Mediterranean Base Sections. It was hoped that this team could be built in ninety days and that the Americans could be supplied entirely from the United States by that time. Each task force was, meanwhile, to be supplied by the base from which it was mounted. Gradually ETOUSA was to relinquish its supply responsibilities until TORCH and BOLERO, possibly within the framework of a single theater command, developed separate supply channels.60 But this was in the future and at the level of high policy. At their own level, pipeline and spigot quartermasters had to be content with a few paragraphs extracted from highly classified TORCH administrative orders.