The Signal Corps: The Test

Blank page

Chapter 1: December 1941

“This Is Not Drill”

At four o’clock on the morning of 7 December 1941, two U. S. Army signalmen switched on the radar at their station near the northernmost point of Oahu. They would be on duty until seven, when a truck would call to take them back to the post for breakfast. The rest of the day would be theirs, for it was Sunday, and the big SCR-270 radar would be closed down until the next early morning shift. Along with five other mobile stations spotted around the perimeter of the island until the permanent sites could be made ready, the Opana radar was intended to operate for two hours before dawn and one afterward, according to the latest operating schedule agreed upon under the past week’s alert.1

Throughout the Hawaiian Department the alert had been ordered rather suddenly on Thanksgiving Day, and instructed all troops to be on guard against acts of sabotage. The Honolulu Advertiser had printed a story on the Saturday after Thanksgiving that had carried the headline “Japanese May Strike over Weekend,” and certainly it was difficult not to see how ominous the international situation was; yet nothing had happened, after all, and the round-the-clock operating schedule which the alert had brought about had been relaxed. Another week of menacing headlines had reached a climax just the day before, on 6 December, with a warning, “Japanese Navy Moving South,” on the first page of the Advertiser.2 Many persons felt that it would be well, in view of the large population of Japanese origin in the Hawaiian Islands, to prepare for the possibility that a Japanese power drive into the rich Asiatic Indies might be accompanied by trouble stirred up locally.

The officers charged with aircraft warning saw no reason to anticipate trouble beyond that possibility. The operation of the radars and the control of the Signal Aircraft Warning Company, Hawaii (13 officers and 348 enlisted men) were currently responsibilities of the signal officer of the Hawaiian Department, although when the training phase was completed they were to be turned over to the Air Forces, which controlled the information center and the other elements comprising the aircraft

warning system.3 The alert which the commanding general, Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short, had ordered into effect upon receipt of secret messages from his superiors in the War Department was the lowest of three grades, an alert against sabotage. Accordingly, in order not to risk burning out the radars, for which there were few spare parts, the acting signal officer of the Hawaiian Department (in the absence of the signal officer, who was on a trip to the United States) had instituted a short but intensive schedule calling for radar search during the three hours considered to be the most dangerous each day. Moreover, the platoon lieutenant of the Signal Aircraft Warning Company, Hawaii, who had the Opana crew under his responsibility, had agreed that two men would be enough for the Sunday operation and had let the third, normally on the roster for that duty, off with a pass to Honolulu. Pvt. Joseph L. Lockard and Pvt. George A. Elliott drew the duty, went up to the station Saturday afternoon, and woke themselves up at four to begin their stint.

The radio aircraft-detection device, the SCR-270, was very new and very secret. It generated a powerful pulse of electricity which its antenna threw out into the surrounding sky, and it caught upon the luminous face of its oscilloscope the reflection of the interrupted electric beams in case anything got in the way. Some of these echoes were steadfast, caused by nearby cliffs and hills beyond which the radar was blind. Others were temporary—and these were the ones to watch for. They indicated and tracked airplanes in the sky reflecting the invisible beams of the radar transmitter.

For the entire three hours of their scheduled watch, Privates Lockard and Elliott saw nothing out of the ordinary. Elliott was new to the device, but it was as apparent to him as to Lockard that the oscilloscope showed a normal early dawn sky, with an occasional airplane from one of the military or naval fields on the island. At 0700 they prepared to close down. The truck was late. The radar hut was warmer than the out-of-doors and there were places to sit down, so Elliott urged that they keep the equipment on while they were waiting. He could then take advantage of a good opportunity to practice with it under Lockard’s supervision. At 0702 an echo appeared on their oscilloscope such as neither of them had ever seen before. It was very large and luminous. They reasoned that something must be wrong with the equipment. Lockard checked it, found it in good working order, and observed that the echo was as large as ever. He took over the dial controls, and Elliott moved over to the plotting board. By their calculations, a large flight of airplanes was 132 miles off Kahuku Point and approaching at a speed of three miles a minute.

Because such a large formation was so unusual, Private Elliott suggested that they report it to the information center. After some discussion, Lockard agreed, and Elliott made the call at 0720.4 At the

information center at Fort Shafter, atop a small concrete building used as a signal warehouse, only Pvt. Joseph P. McDonald, 580th Aircraft Warning Company, Oahu, and a young Air Corps lieutenant, Kermit Tyler, were present in the building. The plotters had left at 0700 to enjoy their first off-duty day in a month. McDonald had been on duty at the private branch exchange switchboard since 1700 the previous evening, and was waiting out the last ten minutes until he, too, would leave at 0730. So far as he knew at the moment he was alone in the building. There was no one at the Navy position—no one had been appointed. Tyler would not have been in the center, either, except that he was new, and the air control officer had thought it a good idea for him to take a four-hour tour of duty to become acquainted with the routine. Thus it was only an accident that Lockard and Elliott happened to be on hand at the detector station after 0700, and part of no formal schedule that McDonald and Tyler happened to be on hand after that time at the information center.

When McDonald answered Elliott’s call, Elliott told him that a large number of planes was coming in from the north, three points east, and asked him to get in touch with somebody who could do something about it. McDonald agreed, hung up, looked around and saw Lieutenant Tyler sitting at the plotting board. McDonald gave him the message. Tyler showed no interest. McDonald then called back the Opana unit, and got Lockard on the wire. By this time Lockard was excited, too. McDonald, leaving Lockard on the wire, went back and asked Tyler if he wouldn’t please talk to the Opana men. Tyler did, spoke to Lockard, and said, in effect, “Forget it.” Tyler had heard that a flight of Army bombers was coming in from the mainland that morning, and he had heard Hawaiian music played through the night over the radio, a common practice for providing a guide beam to incoming pilots flying in from the mainland. He assumed that the airplanes the radar was reporting were either the B-17’s expected from the west coast, or bombers from Hickam Field, or Navy patrol planes.5

Back at the Opana station after talking with Tyler, Lockard wanted to shut the unit down, but Elliott insisted on following the flight. They followed its reflection to within twenty miles, where it was lost in a permanent echo created by the surrounding mountains. By then it was 0739.6 A little later the truck came, and they started back to the camp at Lawailoa for breakfast. On the way, they met a truck headed away from camp, bearing the rest of the crew with all their field equipment. The driver for Lockard and Elliott blew the horn to signal the other truck to stop, but the driver paid no attention and kept on going. The Japanese air attack on Pearl Harbor began at 0755, with almost simultaneous strikes at the Naval Air Station at Ford Island and at Hickam Field, followed by attacks on strategic points all over the island of Oahu. The residents of Oahu were accustomed to the sight and sound of bombs used in military practice maneuvers; they did not realize immediately that this time it was no practice drill. Some of the Signal Corps officers on the island were on duty; others were alerted by the first wave of bombings; still others knew nothing of it until notified officially.

Lt. Col. Carroll A. Powell, the Hawaiian Department signal officer, had just returned from a trip to the mainland. Lt. Col. Maurice P. Chadwick had been appointed only a month before as signal officer of the 25th Infantry Division, which was charged with the defense of the beaches, the harbor, and the city of Honolulu. He was in his quarters at Hickam Field when the first bomb dropped on the battleships in the harbor. A few minutes later Japanese planes winged in low over his house as they attacked the nearby hangars. Hastily the colonel piled mattresses around a steel dining table and gathered his children under its shelter. Then he hurried off to direct the communication activities of the signal company as the troops moved into position.7

The officer in charge of the wire construction section of the department signal office, 1st Lt. William Scandrett, was responsible for installing and maintaining all permanent wire communication systems throughout the islands—command and fire control cables, post base distribution facilities, and the trunking circuits from major installations. By one of the quirks of fate that determine the course of events, the Engineers had been remodeling the tunnels at the battle command post, and the Signal Corps had removed the switchboard and distribution cables to preserve them from the blasting and construction. Thus the command post was virtually without telephone communication when the Japanese struck. At once Scandrett’s Signal Corps crews rushed to the command post and restored the switchboard and cables in record time.8

At Schofield Barracks, men from the communications section of the 98th Antiaircraft Regiment were frantically setting up switchboards and connecting telephones at the regimental command post at Wahiawa for the gun positions around Wheeler Field and Schofield Barracks. The communications lines had been strung to each gun position, and at the command post itself all the wires were in and tagged. But under the November alert the telephones and switchboards remained in the supply room at Schofield Barracks as a precaution against theft and sabotage. About 0830 2nd Lt. Stephen G. Saltzman and S. Sgt. Lowell V. Klatt saw two pursuit planes pull out of a dive over Wheeler Field and head directly toward them. Each of the men seized an automatic rifle and began firing. One of the two planes, trapped by high tension wires, crashed on the far side of the command post building. Running around to look at it, the men felt worried—to use Saltzman’s words—at seeing an American engine, an American propeller, and an American parachute. “And, well, that’s about all there was to it”—except that Air Corps Intelligence later decided that the plane was Japanese—“and we went back and finished setting up our communications.”9 Within twenty-five minutes the equipment was connected. In fact, communications were set up hours before the guns were in place and ready to fire, in late afternoon.

Within a half hour after the first bombs fell in Hawaii, the Signal Aircraft Warning

Company, Hawaii, had manned all six radar stations and the information center.10 About 1000 a bomb blast cut the telephone wires leading from the Waianae radar to the information center. The Waianae station commander at once sent a detail of his men to the nearest town where they confiscated a small 40-watt transmitter and antenna, together with the Japanese operator, who was prevailed upon to help install the set in the station. By 1100 the Waianae radar station was communicating with the information center by radio, thus establishing the first radio link in what became within the next few weeks an extensive aircraft warning radio net covering both Oahu and the principal islands nearby.11

The attacking Japanese planes withdrew to the northwest, the earliest returning to the carriers by 1030, the latest by 1330.12 The Opana station, reopened after the first wave of Japanese planes attacked, tracked that flight or some other flight back from Oahu in the same northerly direction from 1002 to 1039. In the confusion and turmoil, amid numerous false reports from both civilian and military sources, the Navy sent its ships and planes out to search for the Japanese carriers, centering the search to the southwest. The Air Corps also sent planes in that direction. There was much bitterness afterward over the question of why there was no search to the north, and why the radar information of the outgoing flights, apparently headed back to rendezvous, was not given to the searchers at the time.13 The reasons for this failure are much the same as those that underlay other mishaps of that day: the information center, and indeed the entire aircraft warning system, was still in a training status, and if any one in authority saw the radar plot, he was too inexperienced to realize its possible significance at the time.14

Except for one major cable put out of

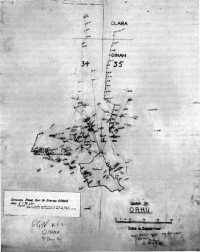

Original Radar Plot Of Station Opana

commission at Hickam Field, the Japanese attack did little damage to signal installations. Soldiers and civilians working through the second phase of the bombings quickly patched all the important circuits in the Hickam cable. Two hours before midnight a third of the damaged Hickam Field circuits were back in the original route, and by two o’clock on the morning of 8 December the whole cable was restored.15

Word of the attack reached the Navy communications center in Washington at 1350 Sunday, Washington time, over the direct Boehme circuit from the Pearl Harbor radio station.16 In an action message over the name of Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, the commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, the broadcaster was saying “Air attack on Pearl Harbor. This is not drill.”17 Thus he was correcting the first incredulous reaction to the falling bombs.

As word spread through the military establishment in Washington, General George C. Marshall, the Chief of Staff, wanted to know why the warning message he had sought to send that morning had not arrived in time to avert disaster.18 Atmospheric disturbances in the vicinities of San Francisco and Honolulu that morning had rendered the Army radio circuits unusable. For that reason, Lt. Col. Edward F. French, the Signal Corps officer in charge of the War Department Message Center, had turned to the commercial facilities of Western Union and the Radio Corporation of America (RCA).19 When he had sent Marshall’s message from the Center (at 0647 Hawaiian time) he had told Western Union that he desired an immediate report on its delivery. Now he perspired at the telephone trying to get it. “I was very much concerned; General Marshall was very much concerned; we wanted to know whose hands it got into. This went on late into the night; I personally talked to the signal office over there.”20 French was not able to talk to Colonel Powell, the Hawaiian Department signal officer, who was busy in the field, but he did talk to the Hawaiian operator, and told him that it was imperative to be able to tell Marshall who got that message.

It was not until the following day that Washington received a definite answer, and learned that the RCA office in Honolulu had delivered the message to the signal center at Fort Shafter in a routine manner. The warning message had arrived in Honolulu at 0733, twenty-two minutes before the attack, and a messenger boy on a motorcycle was carrying it out to the Army post when the bombs started falling. The boy delivered the message at Fort Shafter at 1145, long after the main attacking groups of Japanese planes had retired.21 About an

hour was spent in decoding it; it had to be processed through the cipher machine and then played back to make sure of its accuracy. At 1458 it was placed in the hands of the adjutant general of the department, who delivered it to General Short’s aide, who gave it to Short at 1500. The warning was in Short’s hands, then, 8 hours and 13 minutes after it had left the War Department Message Center, 7 hours and 5 minutes after the attack had begun.22

War in the Philippines

Meanwhile, farther west, the Philippines, a focus of Army and Navy power for forty years, came under attack.23 The one o’clock warning message which General Marshall had sought to send to General Short in Hawaii had gone also to General Douglas MacArthur, commanding general of the United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE). In fact, it had been transmitted, in the signal sense of the term, as number two in the series of four which went out to Panama, the Philippines, the Western Defense Command, and Hawaii. It had left the War Department Message Center at 1205, Washington time.24 But before it reached the Philippines, word of the attack on Pearl Harbor had arrived more or less unofficially. About 0300 on 8 December (it was then 0830, 7 December, in Hawaii) a Navy radio operator picked up Admiral Kimmel’s message to the fleet units at Pearl Harbor. About the same time a commercial radio station on Luzon picked up word of the attack.25

Thus the military forces in the Philippines were on combat alert several hours before sunrise and before hostile action occurred. With the Pacific Fleet crippled by the attack at Pearl Harbor, the prime target in the Philippines became the Far East Air Force (FEAF).26 The Japanese could be expected to launch their initial attacks against the major airfields. Of these, Clark was the only big first-class airfield for B-17’s in the islands.27 Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton, commander of FEAF, had established his headquarters at Neilson Field, which had been taken over from a commercial owner. Nichols Field was of less than top rank. A scattering of others, all the way down to Del Monte on Mindanao, were but emerging. Clark Field was the only one comparable to Hickam Field in Hawaii,

and there were no others like them in between.28

At Clark Field the Signal Corps had provided telephone and teletype connection with Neilson and Nichols. SCR-197’s had recently arrived to give tactical radio communications to each of the fields.29 The Philippine Long Distance Telephone Company brought commercial telephone in to Brereton’s headquarters from all parts of Luzon, where local aircraft spotters had been appointed to telephone reports of what they saw. The spotters’ reports, telephoned to the communication center at Neilson, were supposed to be relayed by teletype to Clark.30

In time, this primitive arrangement of spotters was expected to yield to the mechanized and infinitely more accurate reporting information supplied by the Army’s new aircraft detection devices, the long-range radars SCR-270 and SCR-271. As yet, however, very few sets had been manufactured, and of those few only a half-dozen had been shipped to the Philippines under the strict priorities established by the War Department. Of the half-dozen, only one was set up and in satisfactory operating condition when war came.31

The Signal Company Aircraft Warning, Philippine Department, had arrived in Manila on 1 August 1941 with about 200 men, but with no aircraft warning equipment.32 The first SCR-270 allotted to the Philippines arrived two months later, about 1 October. At once the men uncrated and assembled it. The SCR-270’s were the mobile versions. They required less time to erect than did the fixed SCR-271’s, but for all that they were massive and complicated mechanisms, and it was necessary to spend many hours testing and adjusting the sets at Fort William McKinley, and more hours instructing and training the men who operated them. No test equipment of any sort accompanied the set (or, indeed, any of the others which subsequently arrived). Fortunately, this first set gave so little trouble that Lt. C. J. Wimer and a detachment of thirty men shortly were able to take the radar to Iba, an airstrip on the coast about a hundred miles to the northwest of Clark Field. By the end of October the Iba radar was in operation. At about the same time,

Lt. Col. Alexander H. Campbell, the officer in charge of aircraft warning activities, set up a central plotting board at Neilson Field to coordinate the activities of all types of air warning.33

Within the next two weeks three more SCR-270 sets arrived at Manila, as well as two SCR-271’s in crates. The 271’s were the fixed radars, which had to be mounted on high towers. It took months to prepare the sites,34 so for the time being the SCR-271’s, still in their crates, were put into storage. Of the mobile sets, two appeared to test satisfactorily, but nothing the men could do would coax the third to operate efficiently. Within a few days Lieutenant Rodgers set out by boat for Paracale, Camerines Norte Province, Luzon, about 125 miles southeast of Manila on the coast of the Philippine Sea. He took with him one of the better mobile sets and one of the crated SCR-271’s, planning to use the mobile set until the permanent site for the fixed radar could be made ready. Rodgers and his men got their 270 set up, and started preliminary test operation by 1 December.35

Meanwhile, Col. Spencer B. Akin had arrived in the Philippines to become General MacArthur’s signal officer. Unlike the situation in Hawaii, where the aircraft warning company and the operation of the radars were Signal Corps responsibilities at the outbreak of war, in the Philippines the Air Forces controlled the entire air warning service. Although it was not one of his responsibilities, Colonel Akin felt impelled to recommend strongly that all radar sets and aircraft warning personnel allocated for the Philippines be shipped at once, without reference to the established priority schedules of shipment.36 Doling out the remaining radars in the closing days of November Colonel Campbell sent Lieutenant Weden of the Signal Company Aircraft Warning to a site some forty-five miles south of Manila on Tagaytay Ridge. Weden drew the damaged set. Any hope that it might work better in this location soon faded; the set could not be made to operate satisfactorily, although it was still useful for training. About 3 December another Signal Corps officer, Lt. Robert H. Arnold, rushed the last remaining SCR-270 to Burgos Point on the extreme northern tip of Luzon. Arnold arrived at his location on the night of 7 December.37 A few days earlier, the Marine Corps unit at Cavite had informed Colonel Campbell that it had just received a radar set, but that no one knew how to operate it. This was an SCR-268 radar, a short-range searchlight-control set developed for the Coast Artillery and not intended as an aircraft warning set, although it was sometimes used as such. A Signal Corps crew hurried to Cavite and helped the marines take the set to Nasugbu, below Corregidor, and on the southwest coast of Luzon.38

To sum up, then, this was the tally of aircraft warning radars in the Philippines on the morning of the Japanese attack: an SCR-270 at Paracale, with tuning and testing just being completed, and an SCR-271 in crates; a faulty SCR-270 at Tagaytay Ridge, still giving trouble but able to be used for training; an SCR-270 at Burgos Point, not yet assembled for operation; an SCR-268 at Nasugbu in the care of an untrained crew; one SCR-271 still in its crate in a Manila storeroom; and finally, at Iba, the one radar fully competent and able to perform its role.39

The prime purpose of the Iba radar installation, according to the young officer in charge of it, was to demonstrate to commanders and troops alike what radar was, what it could do, and how it operated.40 A grimmer mission emerged in the closing days of November when Colonel Campbell ordered Lieutenant Wimer to go immediately on a 24-hour alert until further notice. On the nights of 3 and 4 December the Iba radar tracked unidentified aircraft north of Lingayen Gulf, and Wimer radioed the reports to Neilson Field. Single “hostile” planes had been sighted visually that week over Clark Field, as well, but attempts to intercept them had failed.41

Sometime in the early morning hours of 8 December (it was 7 December in Hawaii) the Iba radar plotted a formation of aircraft offshore over Lingayen Gulf, headed toward Corregidor. The Air Forces records put the time as within a half hour after the first unofficial word of Pearl Harbor reached the Philippines, and state that the planes were seventy-five miles offshore when detected. The Signal Corps officer in charge of the Iba radar remembers the time as before midnight, and the distance as 110 miles offshore. He states that the first news of the Pearl Harbor attack had not yet reached Iba.42 The 3rd Pursuit Squadron at Iba sent out planes for an interception. But the long-range radars of that period could not show the elevation of targets, and in the darkness the pilots did not know at what altitude to seek the enemy. Poor air-ground radio conditions prevented contact with the American planes, although the Iba station was keeping in touch with aircraft warning headquarters at Neilson, point by point. As the American pursuit planes neared the calculated point of interception about twenty miles west of Subic Bay, the radar tracks of both groups of planes merged, showing a successful interception. Actually, the pursuits did not see the Japanese

aircraft and apparently passed beneath them, missing them altogether as the Japanese turned and headed back out to sea.

This failure to come to grips with the enemy was the first of a series of tragic mischances which spelled disaster for the Far East Air Force. The events of the next few hours have become clouded by dispute and cannot be reported with accuracy.43 At any rate it appears that the Japanese made several strikes at lesser targets before launching their main attack on Clark Field. All of the initial enemy flights were reported faithfully by the aircraft warning service, both through calls from aircraft spotters and through radar reports. The Iba radar began picking up enemy flights due north over Lingayen Gulf about 1120, at a distance of approximately 112 miles. During the next hour the Iba crewmen were frantically busy, checking and plotting enemy flights, radioing the reports to Neilson Field and to subsequent points along the enemy flight path until the planes were lost by interference from mountain echoes as the Japanese, flew down Lingayen valley. New flights were appearing before the old ones were out of sight, twelve of them in all, in waves of three flights each. The radar was still picking up new flights, still reporting them, when enemy bombers struck Iba at about 1220, silencing the station and completely destroying it.44

Waiting and watching in the Neilson headquarters communications center as the reports started coming in that morning were Col. Harold H. George, chief of staff of the V Interceptor Command; his executive officer, Capt. A. F. Sprague; his aircraft warning officer, Colonel Campbell; and Campbell’s executive officer, Maj. Harold J. Coyle.45 Listening to the reports coming in, Colonel George predicted that “the objective of this formidable formation is Clark Field.” A message was prepared warning all units of the FEAF of the incoming flight. Sgt. Alfred H. Eckles, on duty with the FEAF headquarters communication detail, carried the message to the Neilson teletype operator. There he waited while he saw the message sent, and the acknowledgment of the Clark Field operator that it had been received by him. The time was about 1145.

For the next half hour or so, George, Campbell, Coyle, and Sprague watched the plotting board, where the indications of the approaching flight were being charted. Campbell was apprehensive; he kept asking the others to do something about it, but the air officers were waiting for the enemy to approach close enough to permit the most effective use of the outnumbered American defending aircraft. When they decided that the Japanese were within fifteen minutes’ flying time of their target, Captain Sprague wrote a message. He showed it to George and Campbell. “What does the word ‘Kickapoo’ mean?” asked Campbell. They told him, “It means ‘Go get ’em.’ ” Captain

Sprague took the message into the teletype room for transmission.

At this point the record dissolves in a mass of contradictions. Most Air Forces accounts state that no warning message was received at Clark Field, and place the blame variously on “a communications breakdown,”46 “cutting of communications to Clark Field by saboteurs, and jamming of radio communications by radio interference,”47 and the allegation that “the radio operator had left his station to go to lunch,” and that “radio reception was drowned by static which the Japanese probably caused by systematic jamming of the frequencies.”48 Colonel Campbell states that he and the others assumed that the “Go get ‘em” message had been sent and received properly, since they had had perfect communication with Clark, and since neither Captain Sprague nor anyone else mentioned any difficulty at the time.49 If the teletype circuit was out of order, there were direct radio circuits to Clark, as well as long-distance telephone and telegraph lines available in the Neilson headquarters, which could have been used. Campbell believes that “if the Bomber Command was not notified [as its former commander, Brig. Gen. Eugene L. Eubank, insists] internal administration was at fault.”50

Whatever the facts, the strike at Clark Field, plus the other lesser attacks during the day, rendered the Far East Air Force ineffective as an offensive force. There remained no more than seventeen of the original thirty-five B-17’s, the long-distance bombers which it had been hoped could alter the entire strategy of defense in the area. The military forces in the Philippines must revert to the prewar concept, and resist as long as it was humanly possible to do so.

The First Month of War in the Field

The reverberations of Pearl Harbor brought additional duties to the Signal Corps organization in Hawaii. The biggest single item of Signal Corps responsibility was radar: to get sets in place, get them operating and coordinated with the information center and an effective interceptor system. In the first hours after the attack, the Air Corps had taken over responsibility for continuous operation of the aircraft warning service. Crews of the Signal Aircraft Warning Company, Hawaii, went on 24-hour duty, working in three shifts: 4 hours of operation, then 4 hours of guard duty, then 4 hours off, then repeating the cycle. Thanks to the Japanese attack, Colonel Powell, the department signal officer, could get equipment, men, and military powers as never before. He no longer had to contend with the peacetime obstacles which had hindered his efforts to put up the several SCR-271 long-range fixed radar stations allotted to him. The station at Red Hill, Haleakala, Maui, had been slated for completion on 8 December. The attack on 7 December intervened, but the project was rushed to completion a few days later. At Kokee, on Kauai, where heavy rains had held up installation of a communications cable late in November, the entire station was completed a few days after the attack.

and its radar went into operation early in January.51

The installation of the fixed 271 stations with their towers atop mountain peaks had been thought to be of primary importance because current opinion among radar engineers held that for the best long-range detection, a radar must be located as high as possible. Fortunately, the mobile SCR-270s proved quite good enough for long-range detection, even at lower sites, as the radar at Opana had demonstrated on 7 December. As Signal Corps units acquired more men and equipment, they quickly put up other radars and extended communication nets. Immediately after the attack, they installed two more radars on Oahu. One at Puu Manawahua was borrowed from the Marine Corps; the other was a Navy set, salvaged from the battleship California and set up in the hills behind Fort Shafter. On 18 December the Lexington Signal Depot shipped two SCR-270’s and these Colonel Powell put on Maui and Kauai when they arrived. Next, an SCR-271, complete with three gasoline power units, communication radio equipment, and other attachments, which had been in San Francisco labeled for Alaska, went to Hawaii instead. Three other sets due for delivery in January and originally intended for installation on the continental coasts were similarly diverted, and a mobile information center from Drew Field was shipped by rail and the first available water transportation. Unfortunately the difficulties of shipping so delayed the equipment that it did not arrive in port in Honolulu until 28 March 1942. In the meantime the temporary information center carried on as best it could, in the quarters it had occupied for training before the Pearl Harbor attack, and with such makeshift equipment as it could beg, borrow, or steal.52

All sections of the Hawaiian Department Signal Office under Colonel Powell worked around the clock for several weeks following the attack. For about a week, the civilian employees of the Signal Office lived right on the job. After that they were permitted to go home each night, but many preferred the safety of the signal area to the unknown hazards of the streets outside. The stringent blackout, with armed volunteer guards patrolling the streets, presented its own dangers. There were stories of trigger-happy guards, and of unauthorized lights shot out or smashed with gun butts. Before long, life settled down to a fairly even tempo, although the amount of signal construction sharply increased.53

Communications among the islands, provided by a system which was partly Army, partly Mutual Telephone Company, had been unsatisfactory. To the islands of Kauai, Maui, Molokai, and Hawaii, there was also a radiotelephone service. Powell took over all the amateur radio stations on the islands immediately after the attack.54

The limited telephone facilities at once clogged with a rush of civilian and military calls. The situation, in particular the traffic on the interisland lines, seriously endangered the Army’s and Navy’s means of

communication, especially since it seemed possible that the islands might be blockaded. Some means of control had to be found. Two days after the attack, General Short gave Powell supervision over the local activity of the Mutual Telephone Company in order to limit business to essentials if necessary (it turned out unnecessary) and in order to distribute the limited stock of commercial telephone equipment where it was most needed. Another task added to Powell’s growing burdens was the unwanted but inevitable business of censoring telephone traffic.55

On Oahu a network complex of cable supplemented by much field wire served both tactical and administrative needs.56 Eventually, after 7 December, cable replaced much of the field wire, the latter being retained only where bad terrain made trenching difficult. The network operated through a series of huts located in each of the sectors into which the island of Oahu was divided. These huts contained BD-74 switchboards through which, if one cable became inoperative, another could be connected to reach the desired destination by an alternate route.57

In the Philippines, communications were sorely taxed. At the outbreak of war, Colonel Akin was the signal officer of USAFFE. His assistant, executive, and radio communications officer was Col. Theodore T. “Tiger” Teague, a man who, Maj. Gen. Jonathan M. Wainwright declared, “could make any kind of radio work.”58 In the next seventeen days after 8 December, Akin and Teague arranged the orderly transfer of communications as the forward echelon of Headquarters, USAFFE, prepared to withdraw from Manila to Corregidor. Akin would accompany MacArthur, Teague would remain in the rear echelon with General Wainwright.

Akin and Teague could not count on replenishment of supplies from the United States; they would have to improvise. True, USAFFE had a signal depot, taken over from the Philippine Department, and wire, cable, and radio communications were ostensibly available. So long as the atmosphere of a peacetime Army installation endured, the signal service was adequate, but, like all the other services of the Army, it faltered under the pressures of war. The depot, located in the port area of Manila, became a regular target, and its supplies had to be removed to a less conspicuous building on the outskirts of the city.59 Headquarters telephone service to the three subordinate elements-the South Luzon Force, the North Luzon Force, and the USAFFE reserve—was almost immediately imperiled,

even though the Philippine Commonwealth Telephone Company, which owned the facilities and employed the operators, gave the Army priority service.

The control station for the Army’s tactical radio network occupied a room inside the old wall of Manila, at the Santa Lucia gate, but could not occupy it for long after the invasion. On the day before Christmas, when General MacArthur and his staff left Manila for Corregidor, Teague sent one of his assistants along to set up another temporary control station there. During Christmas week, the new station went up despite unceasing heavy air attacks, and one by one the subordinate stations signed out from the old control station and into the new net on Corregidor. On 1 January 1942 Teague signed off the Manila station permanently, dismantled it, and shipped the equipment by water to Corregidor.

The administrative radio network was also vulnerable. Its transmitter stood near the signal depot and was therefore near the first bombings. Its control room station had to be shifted to an old building, which later crumbled under attack, and then into a vaulted room in the fortress, which still could not save it. So swift was the Japanese advance that the network’s subordinate stations in the north and south, Camp John Hay at Baguio, Mountain Province, on Luzon, and Pettit Barracks in Zamboanga on Mindanao, signed out within three weeks. It was obvious that soon the Manila station, too, would be silenced, and that only the one at Fort Mills on Corregidor would remain.

Although the two ten-kilowatt installations of the Corregidor station made it the strongest in the network, the increasing traffic soon showed that it was hardly qualified to be the sole eastbound channel between Corregidor and the War Department. It was designed to work with Fort Shafter, on Oahu, which in turn relayed to the Presidio in San Francisco. Knowing the system to be slow and inadequate for the demands suddenly placed upon it, Akin, now a brigadier general, got authority to lease the Mackay Radio high-speed machine-operated channel between Manila and San Francisco, and to operate it with Signal Corps personnel. For a time while USAFFE still occupied Manila, traffic to the United States improved; then the Mackay facilities, too, had to be destroyed to keep them from the enemy. The War Department had continued in any case to send all of its messages to USAFFE over the Army channel.

Communications to the northwest, southwest, and south had suddenly and simultaneously increased in importance, for the British, Dutch, and Australian Allies were isolated along with American forces in the Far East. For two weeks, an excellent RCA high-speed channel provided the connection with the British in Hong Kong and, by relay, with the Straits Settlements and Singapore. As the only fully mechanized means of communication in the Manila region, where any operators, let alone skilled ones, were hard to get and almost impossible to replace, the RCA facility was thankfully put into use. Then Hong Kong surrendered, and another outlet was lost. For keeping in touch with the Netherlands Indies, the theater rented Globe Radio facilities. They were less satisfactory, because the Bandoeng, Java, station, although operating with adequate power, was not to be counted upon to adhere to broadcasting and receiving schedules. Most hopefully of all, the signal office set up a radiotelegraph channel between Manila and Darwin, Australia. This channel was

crucial; in those early stages the Americans in the Philippines were hoping to hold out until reinforcements assembled to the south. But this circuit, too, was a disappointment and frustration. The USAFFE signal stations were aggrieved at the Australian use of student operators at Darwin, who were almost impossible to “read”—as if, it was said afterward, “the fact that there was a war in progress and that they and we were combatants and allies [was] merely a topic of academic interest.”60

Meanwhile, the troops were withdrawing to the Bataan peninsula and to Corregidor. Colonel Teague, as signal officer of the rear echelon of the staff, remained behind for a week with a skeleton crew of signalmen to assist in destroying the radio stations still in operation. Day by day during that week, the men worked at their melancholy duty. In the closing days of December, Colonel Teague ordered the receiving equipment of the Manila station dismantled to save it from the enemy. The fixed transmitting equipment and antenna were blown up to keep them from falling into the hands of the Japanese. On 26 December the plant of the Press Radio Company, both transmitting and receiving, was demolished; on 27 December crews dismantled the interisland radio equipment of the Philippine Commonwealth Telephone Company, crating it and shipping it to Corregidor; on 28 December they destroyed the Manila radio broadcast station; on 29 December the Mackay station; on 30 December that of the Globe Radio Company; and on 31 December the RCA station. On New Year’s Eve, trucks carrying troops and supplies headed from the capital to Bataan, and Teague with others crossed to Corregidor from a flaming port at 0330. Signal Corps communications now withdrew to the “Rock” to carry on the fight.

Meanwhile, in the gloomy succession of defeats, disaster came to tiny Wake Island and its small American garrison, which included a handful of Signal Corps men. Only the month before, Capt. Henry S. Wilson with “five cream [of the] crop radio people” from the 407th Signal Company, Aviation, in Hawaii had been sent to Wake Island in order to establish an Army Airways Communications System station there for the Air Corps.61 Previously Air Corps messages handled by the Navy had sometimes been delayed as long as twenty-four hours and the local Pan-American station had not been able to operate the homing beam successfully. Both circumstances had seriously interfered with the prompt routing of airplanes to the Philippine Islands. The Signal Corps detachment, two days after its arrival, had put into operation an SCR-197 radio truck and trailer which the Navy had transported to the island.

On Sunday morning, 7 December, Wilson was expecting a flight of planes from Hawaii. On awakening he picked up his telephone to check with the sergeant on duty in the radio station, as was his custom. Immediately, the sergeant pulled his radio receiver close to the telephone mouthpiece and Wilson heard the radioed dah dits coming in from Fort Shafter, “This is the real thing! No mistake!” Wilson recognized Lt. Col. Clay I. Hoppough’s “fist” as he pounded out the alarm again and again.62 In the next few hours of preparation the men moved the radio truck into the brush near the half-finished powder magazine. In the meantime Sergeant Rex had tried to warn the garrisons in Darwin, Australia, and in Port Moresby, New Guinea, that the Japanese had launched a war, but they would not believe him.

A few minutes before noon the war broke over Wake Island. On the tail of a rain squall a wave of Japanese bombers glided in, engines cut off, undetected. The island had no radar; clouds obscured the raiders. “They just opened their bomb bays and laid their eggs in my face,” Wilson recalled in describing the attack. Then they circled and came back to machine gun. Two bullets penetrated the walls of the SCR-197 trailer and a thick safe (borrowed from the marines), went on through the radio receiving position, but failed to wreck the set. Both the marines’ radio station, near the original location of the Army’s installation, and the Pan-American radio station were destroyed.63 In that first raid the Japanese transformed the three islands of the atoll into a bomb-pitted shambles, and for the next few days they repeated their attacks. Daily they strafed the position of the Signal Corps radio station, and each night the men changed its location.

On 11 December the Japanese took Guam. On 12 December they landed on southern Luzon. At about the same time the enemy attempted a landing on Wake, but the small force successfully repulsed this initial effort. That night the signalmen dragged the transmitter out of the radio truck and moved it into the concrete magazine, with the help of a civilian contractor’s employees who had been caught on the island. They bolstered the hasty installation with spare bits of equipment salvaged from the Pan-American radio station. They further protected the shelter both by reinforcing it with concrete bars intended for structural work and by piling about eight feet of dirt on top, covering the whole with brush. A day later the naval commander moved his command post into the radio shelter. By this time all naval communication installations had been demolished, except a small transmitter limited in range to about 100 miles. By now the six Signal Corps men constituting the Army Airways Communications System detachment provided the only communication with the outside world. They installed and operated line communication for the Navy as well. During the constant raids they were out under fire chasing down breaks in telephone lines and in receiver positions. Finally, the end came on 22 December when the enemy landed, overwhelmed the small force despite strong resistance, captured the island and bagged the Navy and Marine forces there, together with the little Signal Corps unit. By Christmas Eve the Americans on Wake

Maj. Gen. Dawson Olmstead arriving at Panama. From left: Lt. Col. Harry L. Bennett, Brig. Gen. Harry C. Ingles, Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, General Olmstead, and Col. Carroll O. Bickelhaupt

lay entirely at the mercy of the Japanese, who used the communications wire lying about to bind their captives.64

The closing days of December brought only a sharpening of the bleak pattern of defeat. On Christmas Day Hong Kong fell. The next day the capital of the Philippines was declared an open city, and General MacArthur prepared to withdraw his troops to Bataan. By the end of the month, Corregidor was undergoing its ordeal of heavy bombing. The Japanese entered Manila on the second day of the new year, and newspaper headlines bespoke the coming loss of the islands. Against this grim background, the Signal Corps entered its second month of war, not yet ready, not yet equipped with enough of anything.

The Impact of War in the Office of the Chief Signal Officer

The opening of hostilities found the Chief Signal Officer, Maj. Gen. Dawson Olmstead, in the Caribbean. He had left Washington on 2 December, heading into what appeared to be one of the most likely storm centers, with intent to appraise, stimulate, and strengthen the Signal Corps installations there. While word of the attack spread through Washington by radio and telephone that Sunday afternoon, Signal Corps

officers not already on duty hurried to their desks.65 There were scores of emergency actions to be put into effect at once as the Signal Corps went on a full war basis.

In Quarry Heights in the Canal Zone, General Olmstead was inspecting defense installations in the company of Maj. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, commanding general of the Caribbean Defense Command, and his signal officer, Brig. Gen. Harry C. Ingles, when word came of the Japanese attack.66 For the next few days Olmstead remained in the Caribbean, making note of the most urgent needs for communication troops and equipment.

When he returned to Washington on 16 December, he at once found himself in the center of enormous pressures generated by the sudden onset of conflict: pressures which assumed an infinite variety of forms. The communications industry clamored for instructions and help. Swarms of small manufacturers of electronic items descended upon the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, wrote letters, sent telegrams, and asked their congressmen for assistance. Hollywood, too, sent messages and assurances. Many high-ranking officials in the huge moving picture industry held Signal Corps reserve commissions. With Army photographic needs in mind, they sought ways of assuring their personnel of most useful placement, and at the same time aiding in the war effort. Amateur radio operators wanted assignments. The Federal Communications Commission, intimately concerned with matters of frequencies and radio broadcasting and monitoring in general, needed conferences to map out areas of authority. Other agencies and war boards had to be consulted. The matter of priorities for materials and tools was urgent. There were budgets to prepare, appropriations to distribute, new troop allotments to parcel out.

There was the matter of lend-lease to consider. Equipment which had been rather too confidently allotted to other nations now was ardently desired for this country’s use and defense. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, orders sent out by the War and Navy Departments virtually stopped all lend-lease shipments. Trains were sidetracked, ships held at docks, and manufacturers were instructed to hold shipments from their factories. The Chief Signal Officer wired the Philadelphia and Lexington Signal Depots to stop all shipments of lend-lease materials, and to attempt to call back all equipment then en route, while a rapid survey took place to determine whether any lend-lease supplies should be diverted to American forces on the west coast, Hawaii, and in the Far East. Consequently, some materiel intended for lend-lease countries was sent to American forces, such as 1,100 miles of Signal Corps wire W-110-B diverted from the British and sent to American military units, mostly in the Pacific, but the balance was released to move as planned. Shipments actually were delayed only a few days. The Axis had propagandized that lend-lease would cease entirely as soon as the United States needed all its resources for self-defense. But in his report to Congress on 12 December, the President

removed all fear that lend-lease might not continue.67

Most of all, the demand for equipment was bitter, pressing, and confused. Olmstead was beset on all sides: from Brig. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, Jr., in Alaska and Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt of the Western Defense Command, whose long-standing and vociferous complaints concerning the inadequacy of defenses in their areas now seemed wholly justified; from Maj. Gen. Henry H. Arnold of the Army Air Forces whose needs were obviously urgent; from the General Staff; from the Allied missions in this country. From every outpost requests poured in for more air warning equipment, higher powered transmitters, and radios better suited to the locality. Commanders overseas became more critical of what they had, and more impatient at delays or omissions in filling requisitions. Often the items they asked for had not gone into production.

Basically, all demands centered around the three essential ingredients for the brew of war: money, men, and materials. Money, it could be assumed, would be forthcoming in adequate supply. But funds alone could not be converted immediately into fully trained and fully equipped armies. All the advance planning had been predicated upon a theoretical mobilization day (M Day) which would permit an orderly progression from a state of peace to a state of war. But M Day had remained unidentified, and the events of war now differed from the plans. Necessities which might have been satisfied months hence overwhelmed the military establishment with the most immediate urgency. Like its units overseas, the Signal Corps headquarters organization would have to improvise. It would have to stretch the supply of materials and men on hand far beyond the limits of desirability.

Acquiring Manpower

Pearl Harbor set off tremendous demands for manpower, both civilian and military, which the Signal Corps could not hope to meet until training facilities and allotments were greatly increased. On 7 December just over 3,000 officers and 47,000 enlisted men comprised the Corps’ total strength.68 By 10 December revised authorizations for Signal Corps personnel for duty with the Army Air Forces alone called for 3,664 officers and 63,505 enlisted men.69 Filling the authorizations was another matter. On 7 December nearly every Signal Corps reserve officer was already on duty or under orders to report for duty. In its senior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps units, the Signal Corps had far too few basic and advanced students, and had to face the fact that of those few, some would take commissions in other branches of the Army.70

The need for radar men had been given the sharpest sort of underscoring by the events of Pearl Harbor. Yet in the highly specialized courses for radar specialists and

technicians in the Aircraft Warning Department at the Signal Corps School at Fort Monmouth, only 169 officers and enlisted men were on the rolls. About one hundred Signal Corps officers were taking advanced electronics courses at Harvard University and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and between two and three hundred more specially selected, recently commissioned young engineers and physicists were studying radar in the British Isles as members of the Electronics Training Group.

The supply of trained aircraft warning specialists was pitifully inadequate, despite the fact that no other training activity had received so much critical attention in the past six months. The Air Defense Board’s report, issued in the previous September, had recommended expansion of the signal aircraft warning service by 2,200 officers and 40,200 men, the first sizable increment to be added in October.71 The War Department had responded to the recommendation on 13 November by asking Congress for funds to supply 900 officers and 17,000 men, with the first increment to be added in December.

Meanwhile, the supply of trained men had melted away. Throughout the summer of 1941, Air Forces and Coast Artillery quotas in the Signal Corps School Aircraft Warning Department had remained unfilled, class after class.72 From existing Aircraft Warning Service (AWS) units the Signal Corps drew men to form cadres for new units in this country and at overseas bases. Indeed, by October the I Intercepter Command had lost almost all of its signal personnel by transfer to form cadres for the II, III, and IV Interceptor Commands, and to provide the entire quota of aircraft warning personnel for Iceland and Greenland.73 That same month the commanding general of the Caribbean Defense Command asked for AWS troops for Panama and Puerto Rico. To furnish them would take all the remaining men, and the Signal Corps had been counting on them to help train the expected 17,000 novices.

Joining forces, the Signal Corps, the Army Air Forces, and the Air Force Combat Command united in an urgent plea to the General Staff not to wait until the small “breeding stock” of trained AWS specialists in the United States was entirely depleted, but rather to expand the Aircraft Warning Service immediately by 320 officers and 5,000 enlisted men, charging them off against the 17,000 in the expansion program when it should be approved.74 The 5,000 men to be furnished could come, they argued, from replacement training centers other than the Signal Corps center. This would be necessary because the total estimated output of the Signal Corps Replacement Training Center for November and December would be only 3,220, and of these 1,320 would be required for replacements for task forces, overseas garrisons, base forces, and overhead for schools and replacement training centers, which

current personnel policy required to be maintained at full strength.75

The air staff had prepared the action memorandum on 6 November, but on 5 December an air staff officer reported that it had still not reached the desk of the Chief of Staff. It was “bogged down in a mass of conferences and trivial non-concurrences in the G-1, G-3, and G-4 divisions of the General Staff.”76 To consider the non-concurrences and get the paper cleared would take another month because of the approaching holidays, he thought, and he suggested an alternate plan which could be accomplished at once because the necessary staff approvals were already in hand. It involved the use of Fort Dix, New Jersey, and Drew Field, Florida, as training centers for the desired 5,000 men, the Signal Corps to furnish cadres of trained men from its existing aircraft warning companies to form new ones.

It was this plan that won approval in the first frantic hours after word of the Pearl Harbor disaster reached Washington. Early Sunday evening, Lt. Col. Orin J. Bushey, Army Air Forces staff A-1, called Maj. Raymond C. Maude in the Signal Corps’ Air Communications Division to tell him that the Chief of Staff had given Bushey authority to put the plan into operation at once. It called for 5,000 men for the eastern and southern coastal frontiers, 3,300 of them to go to Fort Dix to be trained in the I Interceptor Command, and 1,700 to Drew Field for the III Interceptor Command. Colonel Bushey asked Maude whether the Signal Corps could furnish the 300 officers needed. At a conference with the air staff the next day, Lt. Col. Frank C. Meade, head of the Air Communications Division, promised the full number at once. Before the conference ended, G-3 had authorized an additional 5,000 men for the other coastal frontier: 2,200 to be divided between the Portland Air Base, Oregon, and Fort Lawton, Washington, for the II Interceptor Command, and 2,800 to be assigned to Camp Haan, California, for the IV Interceptor Command. Ten of the Signal Corps officers went to Panama on 20 December; 55 to Fort Dix, 25 to Mitchel Field, and 60 to Drew Field on 10 December; while 60 reported to Seattle and 90 to Riverside, California, on 12 December.77

These 10,000 men so hastily allotted on the morrow of Pearl Harbor to man Aircraft Warning Service units had had none of the radar training that the Signal Corps gave at Fort Monmouth. For the trainees who went to Fort Dix, the I Interceptor Command was already operating an aircraft warning school of sorts. For those going to the Pacific coast, there were no training facilities in operation as yet. For others going to Drew Field, the III Interceptor Command planned, but did not yet have, another training school.

At Drew Field, four aircraft warning companies, the 530th, 307th, 317th, and

331st, plus a signal headquarters and headquarters company, were in existence on 7 December. It had been expected that these units would form the nucleus of the projected III Interceptor Command school. But within a week, 1,700 infantrymen had arrived from Camp Wheeler, Georgia, to be taught radio operation “without advance notice or instructions as to their disposition.” To provide shelter, authorities hastily erected a tent city, made up of Army tents supplemented by a circus tent from Ringling Brothers’ winter quarters in Sarasota, Florida. On 16 December classes for information center technicians, radio operators, and administrative clerks began. The rainy season was well advanced. Classes of forty men each marched about in quest of comparatively dry spots in which to study. A pile of tent sidings was likely to provide the only sitting-down space. Instructors shouted above the noise of diesels that were plowing up the mud preparatory to building operations. The teacher shortage was so acute that several students who had been teachers in civil life were pressed into service as instructors, although they knew nothing about the subjects they taught and had to learn as they went along, hoping to keep a jump ahead of their classes. The calls for aircraft warning personnel were so pressing that radio operators were partially trained in fourteen days and sent overseas immediately, a practice which all training officers deplored. But it had to be done.78

There were urgent calls for enlisted specialists in other categories. Jamaica in the British West Indies, for example, had more radio sets on hand than it had men to operate them.79 On 11 December the Signal Corps broadcast an urgent appeal to all corps area commanders, asking them to enlist without delay an unlimited number of amateur and commercial radio operators for the Signal Corps. A recognized license was accepted in lieu of a proficiency test, and the men were rushed to the nearest reception center for transfer to the Signal Corps Replacement Training Center.80

The Signal Corps had been adding civilian workers at the rate of about 1,000 per month during the last half of 1941.81 In the last three weeks of December, it added 1,000 per week, more than doubling the midyear figure and bringing the total to about 13,500.82 This meant that at least every other worker was a “new” employee, with less than six months’ experience. Such an influx could not be assimilated without a certain amount of confusion, especially within the headquarters offices, where practically all sections were understaffed. Prospective civilian employees had to be interviewed, processed through Civil Service, and then trained to the particular work of the office which employed them. Consequently the original staff, both officer and civilian, worked all hours trying to keep abreast of current rush jobs while interviewing, training, and finding space for new employees. Interviews had to be sandwiched in between long distance calls and conferences; new employees meant more

desks; more desks called for more space. In most instances desks had to be crowded into the original office space in the old Munitions Building on Constitution Avenue and in sundry other buildings scattered around Washington.

Even with enough money to hire the civilians needed, it was not always possible to find employees possessing the desired qualifications. Private industry, the armed services, and government agencies and bureaus were competing fiercely for qualified employees, while Civil Service procedures in the first weeks of war still used peacetime wage standards and job descriptions that were somewhat unrealistic in the light of the sudden emergency. The need for more workers was most evident in the Signal Corps’ procurement activities, which increased manyfold.

The Procurement Division in the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, barely able to support the increasingly heavy work load during the fall of 1941, was literally overwhelmed during the first weeks of war. For example, its Inspection Section was just being organized. In December it comprised but two men: Maj. John Shuler, the officer in charge, nominally transferred from the Purchase Section in October but still obliged to spend most of his time on Purchase Section work, and one reserve officer, 1st Lt. William H. Caruthers, Jr. Shuler knew his section was being organized to provide staff supervision over the hundreds of inspectors who were already operating in procurement districts and the thousands of additional ones who would be needed for a full-scale procurement program, but he had received no specific directive outlining his functions and duties, and he had as yet only one small office for the staff he hoped to get. One problem, he knew, was the scarcity of qualified men in the field. The inspection training program initiated in Philadelphia before the outbreak of the war and an additional one begun in Chicago shortly afterward could not fill the requirements. In December there were some 800 inspectors in the field, of whom about 260 were in the Chicago Procurement District, and the rest in the Philadelphia Procurement District. They were working long hours of overtime without pay before 7 December; afterward, they worked even longer hours. At the same time, Selective Service was subtracting from the numbers on hand and drawing potential inspectors away from the first training course.83

The Production Expediting Section under Maj. Carrington H. Stone furnished another example of turmoil within the Procurement Division. Since November the section had fallen under the scrutiny of Wallace Clark and Company, management engineers whom General Olmstead had hired to survey his organization and make recommendations to increase general efficiency and to ease expansion for war. Two days before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Wallace Clark had proposed reorganizing the entire system of operation within the Expediting Section. The recommendations were mandatory, and the work involved had to be accomplished concurrently with the

mounting daily schedules, despite the shortage of workers.84

Expediters were expected to be professional breakers of bottlenecks, whatever the nature of the stoppage, and in the first weeks of war the staff in the headquarters section had to eliminate numerous peacetime procedures which slowed up production and procurement. For example, complaints from the depots that radio parts were missing among the elements sent them for assembly brought to light one of the difficulties of the current method of procuring radio sets. During the prewar period, Signal Corps contracting officers placed separate contracts for individual components of radio sets, thus distributing work among more manufacturers. Final assembly of the sets took place at the Signal Corps depots. This system had worked well enough when the volume of procurement was moderate. But with the sudden upward sweep of requirements for radio in late 1941, the contracting officers in the rush of their work tended to overlook some of the components when they placed contracts. Soon after Pearl Harbor, depot crews trying to assemble sets for overseas shipment discovered parts missing: anything from nuts and screws to antennas. In the belief that an incomplete set was better than none, and might be used in some fashion, the depots had been distributing a number of imperfect sets, to the outrage of overseas units that received them. Expediters arranged that henceforth assembly should be delegated to the manufacturer of the largest component, who would assemble complete sets, obtaining the minor components by his own purchase or manufacture, or from a Signal Corps depot. Thus, for example, with the widely used short-range radio set SCR-284, the depots would provide the manufacturer, Crosley, with the headphones, microphones, and antennas, so that the sets could be shipped complete from the Crosley plant.85

Field installations everywhere needed additional civilian workers, and the Secretary of War granted blanket authority to employ any civilians required. The Civilian Personnel Branch of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer stepped up its recruiting efforts to meet the increasing demands from the corps areas, exempted posts, and stations.86 Requests poured in for civilians to fill special posts outside the continental limits of the United States. Puerto Rico needed radio mechanics. Panama wanted large numbers of radio engineers, telephone installers, and telephone engineers. To meet the request, Civilian Personnel arranged with the American Telephone and Telegraph Company to borrow some of the company’s cable splicers for temporary duty in Panama. In the Canal area, a desperately needed radar SCR-271 waited for trained engineers to install it. Signal Corps was asked to recruit civilians with all haste, and send them along by the first available air transportation.87

Accelerating Production

Such signal equipment as was available had to be allotted carefully to those who needed it most. The Signal Corps cupboard, although not completely bare, was not well stocked. The final report of the Army Service Forces states that on 7 December 1941 the Signal Corps had less than 10,000 usable ground and vehicular radio sets, less

than 6,000 aircraft radio sets, and less than 500 radar sets “available,” but does not state whether the equipment was available in depots, or was in the hands of troops.88 Certainly insofar as radar sets were concerned, deliveries of commercial models had not begun until February 1941, and altogether only 491 sets had been delivered by the end of the year.89 These had gone immediately to aircraft warning troops and to training schools as soon as they came off the production line.90 Practically none of them remained in depots for distribution. But even had the Signal Corps possessed equipment and supplies in abundance, the Army did not have enough ships available to carry all the kinds of military items needed when war struck,91 and signal equipment carried a lower priority than ordnance items. Finally, there were not enough escort vessels to afford effective protection in hostile waters—and suddenly all the waters were hostile.

During this first month of war all movement was to the west. As quickly as cargo space could be assigned and escort vessels provided, Signal Corps units and equipment moved out of California ports. Some ships that had left before 7 December for the Philippines were caught by the war en route, and were diverted to Australia. The Army transport Meigs, for example, had headed out of San Francisco for Manila at the end of October, with some Signal Corps men and equipment aboard. After a stop at Honolulu, she was on her way, and crossing the international date line when her radio received news of Pearl Harbor. Diverted from Manila, she went on by way of Fiji to Darwin, Australia, only to be bombed and sunk in the harbor there.92

On the whole, loss of signal equipment in transit across the Pacific was unexpectedly light during the early weeks of the war. Of the approximately 18 transport vessels which war caught at some point in the Pacific between the west coast of the United States and the Philippines bearing troops and supplies to MacArthur, two, both of which were unescorted freighters, were sunk in the course of the journey. Only one of the two, the Malama, sunk about 600 miles from Tahiti on 1 January, was known to have signal equipment aboard. It had only twenty-five tons of Signal Corps cargo. About seven ships turned back after 7 December. The remainder were diverted in mid-ocean to Australia. The Navy transport Republic, flagship of a convoy which had formed just west of Honolulu on 29 November and which was diverted, after Pearl Harbor, from Manila to Brisbane, had aboard the 36th Signal Platoon and its

organizational equipment. This convoy, carrying the first American forces to Australia, reached Brisbane on 22 December.93

The shortage of signal equipment was so critical and the competition for supplies so bitter that on 23 December General Olmstead issued a plea to all segments of the Army to conserve signal supplies and to practice the strictest economy, particularly during training and maneuvers. Use only qualified men familiar with signal equipment to act on surveys, and on inventory and inspection reports, the Chief Signal Officer urged. Waste nothing; remove and repair all serviceable parts of discarded signal equipment for use in training. Units which had been supplied with nonstandard types of equipment should not turn it in, he warned, no matter what the tables of basic allowances said. Rather, they should repair equipment and continue it in service until it was possible to supply the newer types authorized in the tables.94

There were obstinate blocks to be overcome before the goal of quantity production, great enough to fill all requirements, could be achieved. The immediate demands for equipment constituted only part of the total requirements. Requirements, in the peacetime definition, were “the computed needs in supplies and equipment of all kinds necessary to meet a military plan established by the War Department.”95 In the first weeks of war the definition lost meaning. Which plan, whose needs, what computations were to have precedence? For example, in May 1941 the Signal Corps planning staff had estimated that requirements for wire W-110-B would be 412,000 miles for the first year after M Day. But in the three weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, “actual” requirements as computed by commanders in the field and staff planners rose to 832,000 miles. At the same time, requirements for five-pair cable increased thirteenfold above 1940 estimates.96

Actually, requirements could not be expected to be firmly fixed at this early date. One thing was clear enough: whatever the final figures might be, they would exceed the existing capacity of the communications industry to produce. The Signal Corps had devoted much effort to prewar planning for industrial expansion, and most of it was sound enough so that given time it would cover the enormous requirements of global war. But without funds or authority to translate plans into action, little could be done except to blueprint the objectives. Thus only one of the numerous proposed plans to expand the communications industry had been launched before the opening of hostilities. Only 15 out of 180 radio manufacturers in the country had produced any military radios for the Signal Corps before 7 December; of the 15, only 5 had built separate plants for their military work and were producing sets acceptable by military

standards.97 Obviously expansion of manufacturing facilities was going to be a basic problem. In the first week of war the need for a much larger electron tube industry was evident, and representatives of the Army, the Navy, and the Office of Production Management met to devise an expansion program of $14,000,000 affecting eleven companies making transmitting, cathode ray, and special purpose tubes.98

On the day after the Pearl Harbor attack, the Signal Corps’ Production Expediting Section drafted a letter which it sent out to contractors on 9 December. The letter asked for immediate, reply by wire detailing what might be needed to attain the maximum possible production, right up to the limit of twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. “What are your limitations respecting raw materials, skilled labor, plant facilities and machines?” the Signal Corps wanted to know.99 On 20 December the Signal Corps wired officials of the General Electric Company, Bendix Radio Corporation, Westinghouse Electric Manufacturing Company, Radio Corporation of America Manufacturing Company, Aircraft Radio Corporation, and Western Electric Company inviting them to meet with certain officers of the Signal Corps at the Philadelphia Signal Corps Procurement District on the afternoon of 23 December to discuss procurement plans and facilities.100 These were the industrialists upon whom the Signal Corps would depend for the major share of its wartime procurement. They would bear the initial strain of the procurement crisis. They must lend their industrial know-how to train smaller firms in mass production methods. Those among them who were already producing signal equipment must redouble their efforts, take on new contracts, and speed up deliveries.

Neither contracting nor delivery was progressing well. Some critical items for which money had been allotted under the fiscal year 1941 procurement program had not been contracted for; in particular 1,500 SCR-288’s, substitute short-range radio sets for ground troops, who needed them badly, and 20 SCR-251 sets, instrument blind-landing equipment for the Air Forces. In fact, less than half of the $498,311,000 appropriated for critical items of signal equipment on the regular and first supplemental fiscal year 1942 expenditure programs had been awarded.

Deliveries especially were discouraging. Under the procurement programs for fiscal years 1940 and 1941, the week ending 6 December showed that of the 54 important signal items contracted for, 33, or a total of 61 percent, were behind schedule. Delinquencies included 14 types of ground radio totaling 4,542 sets. Contracts for radio sets SCR-536, the handie-talkie used by airborne and parachute troops, called for delivery of 1,000 sets in November, but none were delivered. Deliveries of short-range portable sets SCR-194 and SCR-195 were delinquent by 2,500 sets. Six items for the Air Forces—frequency meter sets SCR-211, marker beacon receiving equipment RC-43, microphone T-30, radio compass SCR-269, and aircraft liaison and command radios SCR-187 and SCR-274—also were behind schedule, but fortunately none

of the delinquencies were serious enough to interfere with the delivery of aircraft.101 In the three weeks remaining in December after Pearl Harbor, contracting speeded up appreciably, but delivery lagged behind. By the end of the year, 16 types of ground sets had fallen behind schedule for a total of 5,812 units, as had six critical types of aircraft signal equipment.102 At that rate, it would take years to complete the equipment orders, yet the stupendous production program required completion in from 12 to 18 months.

Most dire of all shortages were those pertaining to radar. Shortages of materials and tools had delayed production; until July 1941, aircraft detector equipment (which became known as radar in 1942) had a preference rating no higher than A-1-B.103 In December 1941 radar was to American industry a new and uncharted realm, and only two or three of the largest companies had ventured into it. Only three types had been delivered in any quantity: the SCR-268, searchlight control (SLC) radar, and two early warning (EW) radars, the mobile SCR-270 and the fixed SCR-271. The SCR-268 was especially important because it could provide approximate target height data. Enough of them could relieve the serious shortage of optical height finders for fire control, and also provide a stopgap for the Air Corps’ need for ground-controlled interception radars. On 16 December the Signal Corps contracted for 600 additional sets at a cost of $33,000,000 from supplemental funds.104