Chapter 4: The Signal Corps in the ETO to V-E Day—I

The initial assault on the Normandy beaches gained the Allies a tenuous toehold. Afterward came six weeks of bitter fighting as they struggled for room in which to build up a force large enough to exploit their potential material superiority.1 The Germans fought tenaciously to contain the beachhead. They were aided by a freakish turn of exceptionally bad weather that not only seriously hampered efforts to land supplies across the beaches but also cut down the effectiveness of Allied air superiority. At the same time, the Allies benefited by the persistence with which the German command, convinced in part by Allied electronic deception, clung to the belief that the Pas-de-Calais area constituted the real point of invasion, with Normandy but a diversion.2 One important element of this deception involved teams of the 3103rd Signal Service Battalion, set up in southeast England. The radio net they simulated completely deceived the Germans, making them think that an American army of three divisions was readying to invade France by way of the Pas-de-Calais, as captured German radio intelligence reports and maps later proved.3

In the initial lodgment and build-up in Normandy, as in the continued “threat” to the Pas-de-Calais area, the Signal Corps played its part. The Signal tasks were extremely varied. This account can underscore only a minute fraction of the signal work in the ETO, and it must be understood that what is not discussed contributed no less to the successful outcome than that which has been chosen as typical, or as unique.

Signal Techniques With the Armies

Expanding and Extending Communications

Within a week of D-day, radio, wire, and teleprinter circuits provided reliable communications links for all headquarters and all army echelons. First Army construction teams had begun to replace their hastily laid field wire with

spiral-four cable and were swarming over the commercial lines leading to Cherbourg, rehabilitating and readying communications for that port city, once it should be captured. By mid-July this work engaged all the construction units in the theater—the 32nd, 35th, and 40th Signal Construction Battalions and the 255th and 257th Signal Construction Companies.4 A communications control office manned by the signal operations officers of the 17th Signal Operations Battalion and the 32nd and 35th Signal Construction Battalions kept in constant touch with all phases of the signal work. These officers were empowered to reroute circuits, patch out defective facilities, and transfer troops when necessary to maintain communications. The radio nets handled 20,000 groups daily from 26 June to 24 July.5

Cherbourg fell on 27 June. An advance detachment of two officers and ten enlisted men of the 297th Signal Installation Company moved in at once to start repairs on the badly damaged Cherbourg exchange of the French Postes Télégraphes et Téléphones (PTT) . Laboring sixteen hours a day, the men succeeded in finishing temporary repairs by 10 July, when they turned the job over to the 3111th Signal Service Battalion to complete the work and establish a permanent installation. Within a day or two, a makeshift message center and a properly secured crypto room were operating. Cherbourg rapidly became an important communications center.6

While the British Second Army pinned down enemy strength around Caen, the U.S. First Army pivoted south after the fall of Cherbourg, attacking toward St. Lô. Two weeks of bloody fighting by the 29th Division yielded the vital railroad center on 19 July and unlocked the gateway out of Normandy.7

The first weeks of operations brought new developments at the FUSA headquarters level. At each location, complete communications had to be established between headquarters and all essential tactical units. Initially, the Signal Corps set up its telephone and teletypewriter centrals in tents, in deference to General Bradley’s wish that his entire command post be under canvas.8 In mid-July, when 12th Army Group became operational and General Bradley assumed command, General Hodges became FUSA’s commander.9 Hodges preferred his command post to be located indoors. Moving exceedingly heavy and bulky Signal Corps equipment into buildings built several centuries before Signal Corps equipment was invented proved difficult. When the men tried to shove it through doors or windows, it usually got hopelessly stuck.

In any event, Colonel Williams had to prepare for a rapid advance once FUSA broke out of the beachhead. Completely mobile communications centers would be needed. He had the men of the 175th Signal Repair Company and the 215th Signal Depot Company install the telephone switchboard and main frame in l0-ton ordnance vans that Col. John B. Medaris, FUSA’s ordnance officer, provided. When in operation, the two vans were lined up tailgate to tailgate with the backs open. The quartermaster officer, Col. Andrew T. McNamara, furnished canvas covers that could be laced around the two van bodies to keep out rain and permit operation under blackout conditions. The electronic equipment—the army switchboard and teleprinter switchboard, the reperforator equipment and the teleprinters, the highly secret enciphering equipment and the auxiliary equipment—everything not already in self-contained vans went into repair trucks, vans, or specially built shelters in cargo trucks. The men also built duplicate sets so that one could be installed and operating in a new command post before the army commander left his old one. Previously, all of Williams’ carrier equipment associated with the radio relay had been installed in vehicles.10

When the breakout came and FUSA began moving rapidly, the mobile communications centers stood ready to accompany either tactical headquarters or main headquarters. FUSA’s command post moves became virtually painless, considering the complexity of such an operation. Colonel Williams would select the next command post forward and would move his stand-by communications control to that point while the duplicate equipment was still in operation at the old post. Usually General Hodges and his section chiefs seized the opportunity afforded by a command post move to visit the front lines or to inspect depots and other installations. As Hodges had remarked, “I never move anywhere until Williams tells me I can.” Ten or twelve hours later, the communications equipment would be set up at the new site, local extension telephones installed to the various staff sections of the army headquarters, trunk lines to the old command post to the rear spliced through, and everything ready for business at the new site. At the height of the rush across France and Belgium, FUSA’s command post moved on an average of every four days.11

Since FUSA was the only American army to take part in the landings and initial combat on the Continent, it contained some of the best-trained and most experienced signal units. In general throughout the campaign, most of FUSA’s signal operations progressed with remarkable smoothness. As FUSA pressed inland, wire assumed the principal communications load.12 FUSA used all types of wire circuits—field wire, spiral-four, rapid pole line, British multi-airline, open wire line, and commercial open line and underground cable

555th Signal Air Unit spotting enemy planes somewhere in France

facilities. FUSA wire crews were so busy with urgent combat needs that they had no time until after the fall of Aachen to rehabilitate their first large commercial repeater station.13

Colonel Williams described FUSA’s radio intelligence service as “very efficient from the very first day.” The members of the traffic analysis units, some of the most intelligent men in the Army, performed particularly well. FUSA’s army and corps radio intelligence companies possessed their own telephone, teletypewriter, and radio nets, and the army unit (the 113th Signal Radio Intelligence Company) was in a cross-Channel net with the Signal Intelligence Service, ETOUSA.14

Strict attention to signal repair work kept FUSA signal maintenance to a minimum. As for supply, Williams had few complaints, describing it as “almost beyond reproach.”15 FUSA’s photographic service, supplied by the 165th Signal Photographic Company, provided assignment units to each corps and division. The 165th became something of a legend in the theater; its photographers suffered more casualties and garnered more decorations than the men of any other Signal Corps unit in the ETO.16

One communications problem never solved to Colonel Williams’ complete satisfaction was close-support communications between tanks and infantry.17 The Signal Corps tried putting microphones and telephones on the rear of tanks, connected with the tank interphone system through holes drilled in the armor. This proved unsatisfactory because an infantryman could not keep up with the tank and still protect himself in those crucial combat situations when he needed communications most desperately. Trying another approach, Signal adapted SCR-510’s, portable vehicular radio sets that would work on tank radio frequencies, altering the sets so that they could be carried on soldiers’ backs. But the 510 weighed twenty-seven

pounds—“When the going got rough, the foot soldiers simply abandoned them.”18 Finally, just before the Ardennes-Alsace Campaign, FUSA signal troops put lightweight SCR-300 infantry pack sets into the turrets of some lead tanks. This provided suitable communications, but at the cost of added discomfort to the tank crew, cooped up in a space already overcrowded.

Among the Signal Corps troops serving General Patton and the Third Army, morale was very high in spite of unusually difficult communications problems created by Third U.S. Army’s (TUSA’s) rapid sweep across France. Colonel Hammond, who had served Patton as his signal officer in North Africa and in the Sicily Campaign, was charged with maintaining Third Army’s far-flung, ever-shifting, and complex communications network.19

Third Army began operations short of signal units, equipment, and suitable frequency assignments. The TUSA drive developed so rapidly that the planned wire system could not be used. Usually wire crews had time to install only one spiral-four circuit to each corps. A shortage of radios and radio operators forced Colonel Hammond to put more stations than was desirable into a single net. At times, when as many as five stations were netted, the net control station had found difficulty using special antennas in all of the directions required. Moreover, the far-ranging units became widely separated—too far away for effective ground wave reception, yet too close for 24-hour sky wave operations.20 Communications with VIII Corps in Brittany were almost impossible to maintain. By early September, VIII Corps, attacking Brest nearly four hundred miles from TUSA headquarters, became a part of Lt. Gen. William H. Simpson’s Ninth U.S. Army, which had become operational on 5 September.21

In the first month of operations, the TUSA command post moved eight times for an average distance of 48 miles each move. In this situation Colonel Hammond’s loo-mile radio relay systems became indispensable. The sets had arrived at the very last moment, the first one hurriedly installed in weapons carriers by the civilian engineers Waite and Colaguori, working with men from TUSA’s 187th Signal Repair Company.22 The equipment was used catch-as-catch-can, by men who had had time for only a few hours of instruction in its use, on TUSA’s drive to the Moselle. All across France the two engineers kept moving the relay systems from hill to hill, patching the sets as best they could and praying that they would work. Fortunately they did, and the radio relay proved to be a very important factor in keeping General Patton in touch with other Allied forces in the drive across France.23 Colonel

Hammond used the sets point-to-point over distances as great as 75 miles. All together, during August, his men installed 28 radio relay circuits, operating over distances totaling 1,175 miles.24

Colonel Hammond’s scheme for advancing TUSA headquarters, more or less typical of all such operations, was a leapfrog arrangement. On arrival at a new command post, General Patton would select the location for the next command post forward. Hammond would extend his wire axis toward that point. An advance group, always in radio communication with the rear, went forward to select the actual site as soon as the area fell into Third Army’s hands. Usually the advance party was headed by Hammond’s efficient deputy, Col. Claude E. Haswell.25 Within a few hours Waite, Colaguori, and their crews would set up the radio relay stations. The new location became LUCKY FORWARD (LUCKY being the code name for Patton’s headquarters). When it was certain that full wire communication would be in service at this point, the forward echelon would move in and the process would be repeated. The previous command post then became LUCKY REAR. Since LUCKY REAR did not displace with each forward move, the lines of communication were often greatly extended, both to the front and to the rear.26 At times during August as many as six or seven radio relay stations trailed out behind Hammond all the way to Brest.27

Logistical considerations, most of all a shortage of gasoline, halted Third Army for a time west of the Moselle River at the end of August.28 Gasoline shortages also hampered signal operations, particularly the work of the construction battalions. The TUSA signal units required nearly 5,000 gallons of gasoline daily.29 Other shortages—signal supply and signal troops—plagued Hammond when operations resumed. The signalmen he now and then received as replacements always needed more training since the extremely abbreviated courses they had taken in the United States did not fit them to understand the complicated technical equipment they were expected to use. In combat, communications connections must be made very rapidly, and only skilled operators can make them. Hammond did praise the spirit of his men. “In spite of the almost impossible feats demanded of them,” he said, their “ingenuity, loyalty, and persistence” overcame their lack of training and their few numbers.30

When TUSA was assigned a defensive role at the end of September, Hammond’s signalmen were able to construct open wire lines to each corps and as far forward as possible. Wire crews rehabilitated existing commercial facilities of the PTT and for the first time were able to

recover and service some of the field wire they had laid during the advance. When TUSA resumed the attack on 8 November, Hammond could support the drive with the best wire network available since the campaign began in August. By mid-December TUSA possessed “practically perfect” communications to all its units, to higher headquarters, and to its proposed new command post at St. Avoid.31 This command post, however, was never occupied; the German counterattack of mid-December intervened.32

Air-Ground Communication Techniques

Probably the most significant development of the war in air-ground communications involving armored units occurred during the action at St. Lô. The 12th Army Group plans for the breakout depended heavily upon close air support by the IX Tactical Air Command (TAC). Close air support had generally been regarded by airmen as a bothersome diversion from their main task, but Maj. Gen. Elwood R. Quesada, the IX TAC commander, was a young, brilliant, and unorthodox officer willing to try new theories. Successful air support depended upon extremely careful control and coordination, and the crux of the matter was absolutely reliable communication between ground and air. General Quesada’s signal officer, Colonel Garland, and FUSA’s signal supply officer, Colonel Littell, solved the problem by putting Air Forces VHF command radios (SCR-522, the kind installed in fighter-bombers) into tanks, half-tracks, and jeeps. These radios, in the lead tanks of each armored column, could communicate with fighter-bombers immediately overhead as the advance took place. The tanks were literally led by the fighters, each move scouted by the planes. The speed and magnitude of the breakthrough—and it’s successful exploitation—depended in large measure upon the close air support made possible by this means of communication.33

Under General Quesada’s direction, the fighter-tank team worked “with all the smoothness and precision of a well-oiled watch.” This was how a War Department observer who arrived at IX TAC headquarters just as the breakout was getting under way put it. He went on to describe a typical mission:

German tanks and artillery had withdrawn from contact as [the American column] started off. The tank column was just coming up within range of the brow of a hill as they appeared on the scene. “Hello, Kismet Red, this is Bronco. Have you in sight overhead. We have no targets now. Is there anything in the woods off to the left or over the brow of the hill ahead?” Five minutes later the answer comes back, “Bronco, this is Kismet Red. ... There are twelve Tiger tanks about four miles down the road retreating. Shall we bomb them?” “Yes, go ahead. ...” So the P-47’s go down and catch the tanks in a ravine. They blast the lead tank in the first pass and stall it. The others can’t

turn around and they are caught like eggs in a basket. Systematically the P-47’s work them over from very low altitude and destroy them all. ...

This is the kind of war they are fighting, and do the ground forces love it! The ground officers I talked to in many branches were uniform in their praise of the close support fighters.34

In the first six days, the AAF flew four hundred missions in support of the armored vehicles. Their targets for the most part were tanks, batteries, small troop concentrations, and motor transport. These they destroyed in large numbers, constantly worrying an enemy who was being forced to retreat in full daylight as well as at night. A German prisoner of war, who had served at length in Russia and elsewhere, later described the combined air-ground attack as the most devastating he had ever witnessed. This air-ground communications method served throughout the rest of the war with the same successful results.35

Improvisation and Flexibility

The eight weeks between mid-July and mid-September 1944 brought the spectacular sweep of the Allied armies across France to the German border. With the enemy’s left flank pinned down by the U.S. First Army and his right by the British Second, the U.S. Third Army poured through the gap at Avranches, part bursting into Brittany, part swinging northeast on the Seine and outflanking Paris in the south. The British Second Army, the Canadian First Army, and the U.S. First and Third Armies crushed the German Seventh Army in the Falaise–Argentan pocket. Paris was liberated, Allied armor swept across northern France, the U.S. Seventh Army invaded southern France, and the Ninth Army took over the reduction of the bypassed Breton ports. Everywhere success attended the Allies.

In those weeks the Signal Corps precept, “Victory goes to the army with the best communications,” was put to the test. Improvisation and flexibility, long emphasized in Signal Corps doctrine and training, became the mainstay of signal officers faced with “special situations” that developed all along the front. Slow hedgerow fighting, rapid pursuit, extended fronts, task forces, liaison with adjacent armies, defensive positions—no two situations were exactly alike. Signal Corps officers and troops took genuine pride in devising solutions to communications problems.36

Equipment that was useless in one situation might prove invaluable in another, as the 4th Signal Company of the 4th Infantry Division learned. During the slow Cherbourg campaign, the division turned in a ponderous, long-distance SCR-399 radio set, only to draw another frantically from army supply after the breakthrough and the pursuit to Paris and beyond.37

Signalmen of the 4th Division seldom fought the enemy—their job, as the signal

officer, Lt. Col. Sewell W. Crisman, Jr., saw it, was to lay wire and do it well, leaving the fighting to the infantry elements that had been trained for it. On the other hand, other division signal officers complained that the signal troops lacked “really protective” weapons and cited the need for armor on signal messenger vehicles. Lt. Col. William J. Given, signal officer of the 6th Armored Division, said that, in the action around Brest, the division signal company “has just received 17 bronze stars ... but we’d like to trade them for a couple of wire teams, some armored cars and some machine guns.”38 Nonetheless, he summed up the feeling of almost every signal officer when he said, “Any modern outfit that doesn’t improvise is not doing its job very well.”

On D plus 9 the 30th Signal Company landed at OMAHA Beach, then moved near Isigny with the 30th Infantry Division. The company’s first major test came on 9 July in the crossing of the Vire River. With four infantry and two armored divisions on the move in the area, the wire teams worked continuously for seventy-two hours to maintain their lines. Vehicular traffic along the congested roads snapped the wire on poles; heavy enemy shelling shattered it. Wire laid along the hedgerows suffered when armored vehicles plunged through old openings or made new ones as they moved into fields. Heavy rains created additional difficulties.39 As the First Army advanced against fierce German resistance during August, battle losses among regimental communicators ran high. The 30th Division signal officer, Lt. Col. E. M. Stevens, supplied replacements from the signal company. He also set up a signal school to train forty-one infantry replacements as wiremen and switchboard operators.40 By mid-October the division was across France and Belgium into Germany. Aachen fell. Signal troops learned that lines laid in the gutters of paved streets were least vulnerable to shelling and bombing; antipersonnel bombs in particular spread myriads of fragments like flying razor blades and disrupted communications by damaging overhead wire lines.

At army level, the size and complexity of FUSA’s communications system developed a need for two additional agencies not visualized in prewar or preinvasion planning. These were a communications control center and a locator agency.

The control center began with a large blackboard in an army tent and eventually filled a series of boards, in a hospital ward tent, manned twenty-four hours a day. Every circuit for which army signal troops were responsible was drawn on the board in schematic form. The officer in charge, from the signal operations battalion, wore a microphone combination headset and was connected over an intercom system with the operations officer of the army signal section, the chief telephone operator, the wire chief at the main frame, the NCO in charge of each carrier van in use, the teletypewriter switchboard operator, the radio relay stations, and the message center chief and the chief radio operator. A liaison officer from each signal construction

battalion on duty in the center had direct lines to his battalion command post. Commanding officers of the construction battalions had radio-equipped jeeps. The moment trouble developed on any circuit anywhere all responsible elements knew of it (because the intercom was a party line) and at once took the action necessary to clear it up. There was “nothing casual” about treatment of trouble anywhere in the FUSA army communications system.41

Any field army contains many units besides corps and divisions, units as diverse as artillery brigades and laundry or clothing repair units. At times FUSA’s odd-lot units totaled nearly one thousand. To complicate matters such units were constantly being transferred from Advance Section (ADSEC) COMZ to armies, from one army to another, or attached or detached between corps and divisions. Keeping track of such units was exceedingly difficult, yet the Signal Corps had to deliver messages to them and get receipts. A FUSA message center lieutenant, who in civilian life had worked in the mail order department of Sears, Roebuck and Company, devised a solution that evolved into the FUSA locator agency.42 The locator agency, in cooperation with the army adjutant general’s office, established locator cards for each unit. A unit could not receive its mail unless it signed receipts for routine Signal Corps messages specially bagged and deposited at the designated pickup points. Eventually the system worked so well that staff sections came to depend on the Signal Corps to tell them what small, obscure units were assigned to them at any given time, and where they were.43

Wire Communications

Of all the means of signal communication, the wire systems felt the greatest strain. The swift pace of the pursuit laid an almost impossible burden on wire. The armies used up nearly three thousand miles of wire each day. Surprisingly, even the armored division used a great deal of wire—more and more of it as the campaign progressed—until toward the end its wire consumption was virtually the same as that of the infantry division.44 Wire units produced some amazing records. During the campaign on the Cotentin peninsula, for example, VII Corps’ 50th Signal Battalion provided wire communications for six divisions, corps troops, and many other units not normally served. In one case, a single battalion wire team not only maintained the 82nd Airborne Division line but also installed and maintained the division regimental lines when the division signal company suffered heavy losses. From 1 August to 15 September the 50th kept the wire system operating for the VII Corps through eleven moves, totaling six hundred miles. In forty-five days, the 50th laid a wire axis across France, Belgium, and into Germany.45 The 50th was the first signal battalion to enter Belgium—on 6 September—and the first to enter Germany—on 15 September.46

Signal couriers in ruined Ludwigshafen, Germany

In Brittany, signal units experienced the war of rapid movement across the peninsula and the relatively stable conditions around Brest. When VIII Corps was assigned the job of reducing the fortress of Brest, the 59th Signal Battalion became responsible for wire communications to three divisions, an extensive fire direction net, the radio coordination for naval bombardment of the city, and the maintenance of radio link contact to two armies, an army group, and a tactical air force. In addition, the battalion rehabilitated and placed in service 7,250 miles of existing open wire and underground cable in four weeks. Brest was strongly fortified with much long-range artillery and many antiaircraft and naval guns. Furthermore, the area was heavily mined. All signal units, among them the 2nd, 8th, 29th, and 578th Signal Companies and the 310th Signal Operations Battalion, suffered their heaviest casualties to date.47

As the First Army drew near Germany’s Siegfried Line, signal officers took especial pains that commercial cables terminating in German-held cities be disconnected in order to minimize the possibility of agents transmitting information to the enemy over commercial facilities. At the same time they connected certain other lines directly to American intelligence elements.

Friendly agents behind the German lines transmitted considerable valuable information over these lines.48

In the attack on the Siegfried Line, the men of the 143rd Armored Signal Company (3rd Armored Division) got a taste of fighting beyond their normal signal duties. On the night of 2 September the division command post near Mons, Belgium, was attacked by a German column trying to fight its way out of the trap 3rd Armored Division was devising for it. Capt. John L. Wilson, Jr., commander of the signal company, described the next two days of action as “a type of Indian fighting.” The command post became the focal point of the struggle, and in the numerous fire fights the signal company had its share of the action and took its share of the nine thousand prisoners that 3rd Armored Division estimated it captured in two days.49

VHF Radio Relay

Despite the enormous consumption of wire, ETO’s chief signal officer, General Rumbough, said that the only thing that saved communications was radio relay. It was not a lack of wire itself, although wire was in critical supply all through the campaign.50 The forward rush of the Allied armies demanded something that could be installed more quickly than wire systems. Radio relay was the answer. It could be put into operation very quickly and needed few maintenance men to keep it operating. A single installation furnished several telephone and several telegraph circuits, each of which became a part of the whole communications system, quickly connected with any telephone or any teletypewriter in the system.51

The civilian engineers, Waite and Colaguori, stayed in the theater until mid-October to “introduce, install, and instruct” in the use of the radio relay.52 The “introduction” part of their mission was easy, the engineers wrote later. The equipment sold itself; its inherent value was readily apparent once field signal officers saw it. “Installation and instruction” turned out to mean living and working in the battlefield areas under circumstances few civilians encounter. Colaguori and a small crew, after landing in Normandy with the assault forces, had stayed to help set up additional relay circuits for FUSA.53 Waite remained at the St. Catherine’s installation in control of cross-Channel operations until 14 July, when he flew to France. By then FUSA had six radio relay terminals in operation—one at VII Corps headquarters south of Carentan, one at V Corps near Trévières, one with XIX Corps moving toward St. Lô, and three at FUSA headquarters near Isigny.54 Working in a hedgerow field near Isigny with two ETOUSA officers and crews from the 980th Signal Service Company and the 175th Signal Repair Company, the civilian engineers by 2 August had assembled 14 additional terminals as

quickly as the components could be airlifted to Normandy.55

Late in July an urgent call from VIII Corps sent the two civilians and a 6-man crew hurrying off toward Phillipe with AN/TRC-1 equipment. At corps headquarters they learned that VIII Corps had made a breakthrough west of St. Lô, and both the 4th and the 6th Armored Division were heading toward Avranches. An antrac terminal was urgently needed to maintain corps communications with 6th Armored Division headquarters. Hurrying by back roads to a rendezvous point east of Coutances, where a division wire crew was to meet them with spiral-four, Waite and Colaguori set up their equipment and made contact with corps headquarters. Corps informed them that division headquarters had moved on to a point north of La Haye du Presnel in Brittany. Once more they set out, reached the designated point, and learned that 6th Armored Division headquarters was now three miles south of the town. For several hours corps had been unable to keep in continuous contact with its fast-moving division. Wire was out because of the rapid advance, and even the normal radio communications had proved sketchy.

By this time it was near midnight. Packing up in total darkness, the men encountered further delay when successive groups of enemy bombers appeared and dropped bombs on American tank columns on a road paralleling the antrac position. Defending antiaircraft guns showered the ground near the radio station with shrapnel. Driving cautiously in darkness for twelve miles on roads littered with wrecked enemy vehicles, past American crews filling shell craters in the road, the communications men arrived at their new location about 0300 and set up their station once more on listening watch. They congratulated themselves on the relative quiet of the spot; they could hear nothing more ominous than a few German machine gun and pistol volleys a few hundred yards away. At 0830 they got their first call from corps headquarters. But once more the division wire crew failed to appear. At noon the assistant signal officer of VIII Corps arrived at the station. He had no word of the wire crew, but he did have two pieces of news. American tanks had entered Avranches, and, in the darkness, Waite, Colaguori, and their crew had set up their station eight hours before the infantry units followed the tanks through the area.56

As radio relay’s virtues became known, everybody wanted it. Demands from signal officers of all armies, army groups, air forces, and forward sections of COMZ poured in. Tables of equipment had not caught up with it; as rapidly as sets could be seized from the production line they were shipped. General Rumbough directed that all requests for radio relay come to him personally, and he doled sets out as they were received.57 Men of the 980th Signal Service Company, the only trained radio relay unit then in the theater, spread out all over France.

Originally the company was organized into a number of 6-man radio and carrier teams. Now the number of teams fell short of the demand for radio relay installations, and the experienced teams had to be split in half, then thinned again, the gaps being filled by men from the replacement pools. The 12th Army Group had one small detachment from the 980th, but, in order to keep in touch with the armies in the drive across France, it took radio repairmen from the Ground Force Reinforcement Command and gave them on-the-job training in radio relay.58

The two civilian engineers traveled from one headquarters to another. From the moment they arrived in Bristol until they left Paris in October they worked ceaselessly, giving on-the-spot instructions for unpacking and testing the equipment, installing it, siting it, operating it, and maintaining it. Finally, at a time when the calls for their services were coming in simultaneously from a half-dozen headquarters, ETOUSA set up a school in Paris. There, a first class of seventy officers and enlisted men representing all the interested organizations met for a week’s instruction. It is a measure of the importance attached to radio relay that so many high-ranking field commanders engaged in decisive combat operations permitted men to be detached from the scenes of battle to travel to Paris for a training course. It would have been easy, the engineers wrote afterward, for commanders to have shrugged off the untried device, since including it meant deliberately upsetting signal plans that had been carefully worked out months earlier. From among the many they felt deserved special credit, they particularly singled out Colonels Williams, Garland, Hammond, and Littell with high praise for their foresight and vigorous championship.59 After the initial class, the Paris training school was maintained and conducted by officers of the Technical Liaison Division of the ETOUSA Signal Office. The school trained 25 officers and 450 enlisted men, more than half of them for the AAF, before December 1944.60 Meanwhile, during September, October, and November, civilian technicians from Western Electric Company and officers from Camp Coles and the Technical Liaison Division, ETOUSA Signal Office, were busy introducing and setting up later antrac models, AN/TRC-6 and 8 sets. A British No. 10 (a 6-centimeter pulse set) was installed in the Eiffel Tower in Paris, with a second set on a high hill near Chantilly twenty-eight miles away.61 By V-E Day there was enough relay equipment in the theater to provide 296 point-to-point installations, or 74 loo-mile systems, each comprising two terminal stations with spares.62

The Invasion of Southern France

Meanwhile preparations had proceeded apace for the invasion of southern France by the U.S. Seventh Army under the command of Lt. Gen. Alexander M. Patch and by sizable French forces. The assault was to be mounted and supplied from the Mediterranean theater. Signal planning began early in 1944 from an

AFHQ command post established on the island of Corsica. In control of the forces was 6th Army Group, with Colonel Lenzner as chief signal officer and Maj. Max R. Domras as signal supply officer. Col. George F. Wooley was Seventh Army’s signal officer.63

Aboard the USS Henrico and the USS Catoctin, as the invasion fleet sailed from Naples, 1st Signal Battalion men handled communications afloat.64 The command ship for this operation was unique in that it served as a joint Army-Navy-Air Forces control point. In the actual landings on 15 August, the airborne troops went first, communications men with them.65 Since 8 June Signal Corps men who had been dropped in southern France had been taking part in guerrilla warfare assisting the partisans.66

Just before the amphibious assault, other Signal Corps troops emerged from their gliders with jeeps and trailers loaded with radio sets, telephone switchboards, field wire, and other communications supplies. They had networks operating when the amphibious landings took place. Some of these signalmen had been infantrymen, glidermen, and paratroopers before they had received training in communications; others were Signal Corps soldiers who had volunteered for the hazardous and difficult work. However, the attachment of the 1st Special Service Force to the 1st Airborne Task Force created what was, in effect, a provisional division employed as infantry, and the 512th Signal Company, Airborne, was not equipped to function as a division signal company since it did not have enough vehicles, men, or communications apparatus. Other signal troops with the Seventh Army also would not have been adequate for their tasks, had they encountered stiff resistance. The 57th Signal Battalion lacked a complete radio intelligence platoon, and the 3151st SIAM Company was handicapped by a shortage of about seventy-five men, chiefly radio operators. A further complication lay in the failure of the naval task force to unload more than one platoon of one construction company before D plus five.67

As it turned out, the Seventh Army encountered heavy resistance only in the strikes against Marseille, which was taken on 23 August, and at the naval base at Toulon, which fell a few days later to French forces closing in from the north and west. By 28 August organized resistance at those two important ports had ended.

Landing with the assault troops were the signal supply troops of the 207th Signal Depot Company and the 177th

Signal Repair Company. Five enlisted men of the depot company working under Lt. Robert Miller got a taste of battle not ordinarily the lot of a depot crew. Coming ashore at H plus 1, much earlier than a depot unit would ordinarily disembark, they made their way to a designated rendezvous point through small arms fire and took thirteen German prisoners.68

Also among the initial assault forces were the signal operations personnel of the 71st, 72nd, and 74th Signal Companies (Special) to work communications for the three division beach groups. The 163rd Signal Photographic Company handled photographic coverage of both French and American units. A successful Seventh Army innovation was the use of SCR-300 radios in cub planes operating in a liaison net back to the command ship. The planes took to the air at H-hour plus 90 minutes from special flight decks on LSTs. One plane reconnoitered in each division sector, sending back valuable information throughout the day.69

For men of the 57th Signal Battalion—veterans of Salerno and Anzio—the landing at Ste. Maxime on the Riviera was their third amphibious assault landing. H plus 2½ hours found the first wire teams ashore laying spiral-four cable for the VI Corps’ three assault divisions, the 3rd, 36th, and 45th. But the Signal Corps troops were to expend their greatest efforts in maintaining the swift pace of the advance. As fast as supplies were unloaded on the beaches, they disappeared to forward units. The assault moved ahead so fast that signal supply was soon in difficulties. In particular, the troops needed field wire, batteries, and radio tubes. Railroad bridges at Grenoble and Besançon had been destroyed and could not be repaired immediately, and supplies therefore had to be moved forward by truck. There were so few trucks available to the Signal Corps that officers had to take communications vehicles to get the supplies off the beaches and had to arrange for special convoys of trucks to carry batteries and wire to the troops in the Besançon area. Despite all this, Colonel Wooley reported that there were no complaints on communications—the only request to the rear from the forward elements was, “Keep the wire and batteries coming.”70

Throughout the campaign, a shortage of transportation plagued signal operations. As echelons of command spread apart, even high-speed wire construction methods such as rapid pole line (RPL) and multi-airline (MAL) became inadequate and were no longer used. Instead, wire construction men of two battalions rehabilitated 1,716 miles of PTT open wire lines and strung 152 miles of spiral-four. Operations were handicapped, too, during the early phase of the campaign by delay in the arrival of signal units equipped with special-purpose vehicles for wire line construction. The 57th Signal Battalion used a captured German section car to follow open wire leads along the railroads through isolated stretches of country, and

four mobile radioteletypewriter installations built on 1½-ton cargo trucks to assure teletypewriter communications between corps command posts and divisions when wire circuits were cut off by shellfire or other interruptions. Insofar as communications were concerned, September was the Seventh Army’s worst month. High-frequency, long-range radio took over where wire could not. Sky wave could be used almost exclusively to reach all commands. The majority of radio circuits covered distances of more than 100 miles.71

By 11 September, the Allied armies pushing up from the south made contact with those coming east from Normandy, and on 15 September SHAEF assumed command of the Franco-American forces.72 Slowed by the barriers of the Vosges Mountains and the Moselle River, Seventh Army’s communications altered, radio yielding largely to wire. By October, at army and corps level, radio was only an emergency means, although artillery, engineer, and infantry units constantly demanded more radios. Teletypewriter began to carry the bulk of army messages. Field wire became critical in November and had to be rationed. When three new division elements entered the Seventh Army without division signal companies, Colonel Wooley reported that only the close cooperation of corps and division signal officers and tactical good fortune prevented serious signal complications. After the slow push through the mountains to St. Die and Strasbourg, VI Corps speeded up and crossed the German border between Bitche and the Rhine River. Serving with the Seventh Army as it advanced into Germany were six signal companies—the 3rd, 44th, 45th, 79th, 100th, and 103rd. The veteran 36th Signal Company was with the French 1st Army. Three signal battalions, the 1st, 57th, and 92nd, worked on the corps level.73

From D-day at Ste. Maxime to the German border and the Rhine, the 57th Signal Battalion laid 1,511 miles of spiral-four cable, 879 miles of W-110-B, and 451 miles of long-range W-143, recovering 75 percent of all the wire it laid except the W-143, and 26 percent of that. It also rehabilitated 2,614 miles of PTT open wire line; it transmitted 2,273,836 teletypewriter groups and 574,254 radio groups. Its messengers, traveling 129,867 miles, carried 91,749 messages.74

The Continental Communications System

The signal communications system in the ETO provided telephone,

Swimming wire across the Moselle River

teletypewriter, and radio circuits serving over 70 major headquarters.75 The British War Office, SHAEF, COMZ, ADSEC, SOLOC (Southern Line of Communications) , CONAD (Continental Advance Section), the various army group headquarters, the 10 base section headquarters, the many Air Forces and Navy installations, the 7 army headquarters, the ports of Cherbourg, Marseille, Antwerp, and Le Havre, as well as UTAH Beach and OMAHA Beach—all required extensive communications systems. There were also the oil pipelines (2 main lines, with pumping stations with telephones every 10 miles, and main stations with telephone control every 50 miles). There were the railroads, which required two communications circuits along each right-of-way. And there were the redeployment centers, the hundreds of branch and general supply depots, and the many general and evacuation hospitals, all of which had to have extensive communications facilities.76

Wire carried the major portion of traffic, both tactical and administrative. Excluding air-ground traffic and traffic between highly mobile forward units, wire carried perhaps 98 percent of all messages transmitted by electrical means.77 Planning, building, and controlling wire systems engaged the energies of a very large group of signal officers and men for many months before and after the invasion. In fact, even before strategical and tactical concepts of OVERLORD jelled, the Signal Corps was hard at work evolving plans for an adequate outside wire plant. But equally early planning for the ETO allotment of signal troops fared badly. The theater general staff considered the requirements excessive and returned them for revision. So much time elapsed before the theater finally reached a decision that the War Department had already committed a large proportion of the available Signal Corps troops to other theaters. The ETO signal troop basis was fixed at a figure far too low. In spite of much frantic juggling of personnel figures later, there were never enough wire construction and maintenance men in the theater.78

Planning the Continental Wire System

Basic instructions for the combined main line system were laid down by SHAEF. In the U.S. zone, responsibility for the planning lay with the Joint Wire Group, composed of the signal officers of the First and Third Armies, Forward Echelon and Advanced Section, COMZ, and the Ninth Air Force, as well as of the 12th Army Group when it became operational. The group agreed upon two basic policies: pool all circuits in the main-line build, making them available to all organizations on a common user basis; and place all construction troops except those needed for specific missions under the control of the 12th Army Group signal officer. Each section of the main-line build, whether constructed by army, army group, or COMZ troops, would become a part of a coordinated,

planned system. No French line or cable would be rehabilitated and put into service (except for immediate combat needs) unless it had an approved place in the over-all theater wire system. Thus the limited amounts of available wire plant materials and the limited numbers of construction troops could be utilized most efficiently.79

These policies were sound, but unfortunately the theater organization itself partially defeated their application. Because of the decentralization of control, a unified communications system had to be built upon cooperation rather than command action. As operations progressed and the combat zone moved forward, the rear areas divided into fixed-area base sections, each with its own headquarters command. Signal officers of the base sections were responsible to the base commanders rather than to the theater signal officer. Naturally, the primary interest of the base signal officers was to develop a good area system connecting the various depots, hospitals, and other service installations of their respective areas, rather than to extend or maintain portions of the main-line system that fell within the base section. They were also extremely reluctant to release any of their Signal Corps troops for theater requirements on trunk-line work. This led to many delays.80

It was also difficult to maintain the common-user principle. The air forces in particular made heavy demands for point-to-point operational circuits in the main-line system. As a matter of fact, several special systems were imposed upon the main-line system. There was, for example, the Red Line system for key officers of SHAEF. Some Signal Corps officers contended that the priority system of handling trunk calls would have given staff officers the same rapid service as the Red Line without reducing the number of circuits available to common users.81 General Lanahan, however, felt that in so large a theater the Red Line system was essential for rapid handling of high echelon calls. In addition, such a system “took the load of complaints off the back of the signal officer” and permitted him “to get on with the myriad of other duties” he had to perform.82

In their planning, the Joint Wire Group had decided that initially the continental main-line wire system must consist of new construction—open wire and spiral-four cable. The decision was a wise one. The French open wire system and the commercial cables were so damaged that for many weeks they could not be restored rapidly enough to supply military requirements.83 Until the breakout, construction and rehabilitation troops had been bottled up in a fairly small area, unable to advance line communications forward. Once the Allied forces broke out of the beachhead, their advance was so rapid that new line construction could not keep up with the communications demands of higher headquarters. For a time, radio and messenger service had to take up the slack.84

In this period, 12th Army Group, the

most forward headquarters having construction and rehabilitation troops, became responsible for extending the main-line system eastward. The rapid advance of the armies placed a desperate strain on the construction units. Two construction battalions per army and two for the army group were simply not enough in the period of rapid advance, even though 12th Army Group obtained all possible help from COMZ, ADSEC, and Air Forces sources.85

With new line construction temporarily unable to keep up with the advance, various military units began using the civil cable system on a help-yourself basis. Lines of the French government-owned long-distance cable system, the PTT, traversed normal military boundaries of control. Months before the invasion, the SHAEF Signal Division had worked out details of a control plan to be put into effect as soon as Paris was firmly in Allied hands. On 1 September SHAEF took over control and arranged for the establishment of the Paris Military Switchboard to provide trunk service by connecting military exchanges in other centers to the Paris exchange through the French PTT system.86 On 10 September SHAEF established the operating medium, the Allied Expeditionary Force Long Lines Control Agency (AEFLLCA). Administered by the SHAEF Signal Division, it controlled policies, allocated routes and circuits to the army groups and to COMZ, and served as a central liaison office with the French civilian authorities.87 Primarily intended to control the rehabilitation and use of the PTT cables, AEFLLCA later took an active part in the whole main-line system. Actually, despite a certain amount of delay and friction, all organizations cooperated extremely well, considering the various pressures exerted.88

Rehabilitating Cable Systems

The prewar PTT system was quite extensive. During the German occupation PTT employees had managed to operate a clandestine smelting plant in suburban Paris and to construct new cables to serve secretly built transmitter and receiving radio stations. Meanwhile, the Germans also secretly built an extensive network of long-distance cables for their military needs.89

Allied bombings and the retreating Germans had heavily damaged both the liberated and the enemy facilities. Just before the Allied landings in Normandy, the French Forces of the Interior (FFI), in agreement with the Allied command, launched a systematic and successful program of sabotage. French technicians cut the cables at widely separated points, avoiding damage to hard-to-repair equipment such as loading pots and repeater stations. Within a few days after the landings there were widespread failures on existing systems in the Normandy

area, and all efforts of the German wire crews to cope with them were to no avail. French cable splicers, when forced to work for the Germans, frequently made temporary splices wrapped with a bandage and then covered with a non-watertight sleeve. The splices held only until the first rain put them out of commission. This maneuver worked well against the Germans, but it caused the Allies a good deal of trouble later on when some of the splices became covered with the rubble of fallen buildings. Then it was the Allies who sweated and labored to locate and dig out the faulty cables.90

The Germans themselves, as they were driven back, wrecked the communications centers as thoroughly as possible, using destruction troops specially organized and trained for that purpose.91 When time permitted, the demolition troops blew up or burned entire buildings, opened up buried cable and sawed or cut it in half and reburied it, cut single lengths of cable at successive manholes, and poured water over the severed ends. At some cable terminals, German signal troops created damage almost impossible to repair.92

Luckily, some installations were left to the ministrations of German troops inexperienced in signal matters and their “wreckage” was usually easy to repair. Luckier still, French technicians were able to save some of the vital communications centers. So hurriedly did the enemy evacuate the Rhone Valley, along which the Dijon-Marseille cable ran, that at some points ingenious Frenchmen saved the communications installations for the Allies. At one repeater station the station chief convinced the German commander that a grenade exploded on top of the cable-run over the equipment bays would be most destructive. The resulting explosion, though satisfactorily loud, caused no real damage. At another repeater station the Germans, in a hurry to leave, accepted the promise of the French technician to blow up the station. As the Germans left the town, they heard explosions at the station and were satisfied. The technician had pulled the pins of the grenades and thrown them into an empty lot adjoining the station.93

French PTT employees gave the Allies one of the great breaks of the drive to liberate Paris. As Allied armies neared the outskirts of Paris, most of the Germans withdrew from the long-line terminal plant on Rue Archives and wired the plant with time bombs that were intended to wreck it. The French employees seized the last few Germans remaining in the plant and informed them that everyone would stay in the plant. After several hours, the Germans, faced with the fact that they would be blown up along with the plant and their French captors, disconnected the time bombs. An important communications asset had been saved for the Allies.94

For every installation saved, however, two others had been destroyed. The big

repeater station at St. Lô, for example, was demolished by Allied bombings. Of the 130 principal repeater stations in the PTT system, 85 were destroyed or heavily damaged, as were 45 buildings housing them. The Signal Section, COMZ, had anticipated this contingency and had stockpiled all available repeaters. Special truck convoys rushed American repeater equipment to the front areas. When the supply was exhausted, captured enemy equipment and French-manufactured items were used. Though at first unfamiliar with foreign-built equipment, U.S. signal troops within a very short time were installing German, French, and Belgian equipment quite as easily and quickly as that of American manufacturers.95 General Lanahan, visiting a British-American signal crew working in the rubble of St. Lô shortly after its capture, noted that in addition to the destruction of the repeater station, artillery fire and bombs had broken the cables in numerous places. The British major in charge of the rehabilitation crew assured General Lanahan that he would have the cables repaired within five weeks. This promise he kept, although Lanahan had mentally calculated that if he succeeded within three months he would have done an outstanding job.96 French civilian workers also provided valuable assistance on many cable rehabilitation projects, some crews working as much as ninety hours a week. Finally, from the United States came special volunteer crews of civilian cable splicers hurriedly recruited from telephone companies on the eastern coast and flown overseas to help restore civilian cables.97

Equipment and workers were not the only necessities. Coal to heat and dry out the buildings and equipment was another big item. For the shattered window panes, new glass—or temporary substitutes for glass—had to be found. The French had no diesel oil, engine oil, or gasoline to operate the power plants, and these items had to be furnished from Allied stores. The French civilian crews, though eager and able, lacked transportation, food, and blankets. The retreating Germans had commandeered all of the PTT vehicles, leaving only a few broken-down trucks, and from these the Germans had filched all the good tires.

The Allies’ intensive efforts to rehabilitate the system quickly brought results. Five months after the liberation of Paris, almost 90 percent of the circuits in service in 1939 had been restored to service. By the end of the war, the long-distance network equaled that of the prewar system.98 Throughout the campaign, the underground cable network was used almost entirely for military purposes. After the initial stages of the campaign, the cable system became the backbone of Allied communications. By V-E Day, COMZ had rehabilitated over 392,000 circuit miles of toll cable and had installed 1,907 new repeaters in fifty-five repeater stations in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany.99

The value of the rehabilitated civil system of long-distance telephone and

telegraph facilities in the ETO was amply demonstrated. For example, during September and October 1944, the rehabilitated civil system yielded 3,076 circuits, totaling 205,845 circuit miles, compared to an estimated 100,000 circuit miles of new construction built by the combined efforts of the army groups, COMZ, and the tactical air forces. In other words, out of 300,000 circuit miles, only one-third were provided by new construction, even though all the military resources of the theater went into the effort.100 If the Army had been forced to build lines equivalent in number to all those it used in the ETO during the course of the campaign, signal construction troops would still have been hard at work three years after the cessation of hostilities.101

The Paris Signal Center

Once liberated, Paris soon became the theater communications center. For a time, however, especially during late August and early September, communications facilities could not be installed fast enough to accommodate the rapid moves of large headquarters from England to the Continent. Communication between the War Department and the ETO suffered. Traffic to the United States was delayed as much as fourteen hours, and there were serious interruptions in the theater communications system.102 The situation served well to illustrate the point that signal communications systems do not instantly come into being full-blown. They require much advance planning and a great deal of work, time, and trouble.

During August and September, traffic between the War Department and ETOUSA was extremely heavy—so heavy, indeed, that it put a strain on War Department facilities handling overseas business. A total of 356,669 messages containing more than ten million words flowed between the two points. Moreover there were 75 high-level secrecy telephone conversations and 95 teletypewriter conferences, not to mention 736 telephotographs transmitted.103 This was more traffic than the amount carried across the Atlantic by all the existing prewar commercial facilities in any comparable period. Only extensive and complicated semiautomatic and automatic equipment of the most modern type could handle such loads. Furthermore, in the theater a telephone system to serve a large headquarters such as COMZ or SHAEF required as much equipment as that necessary to serve a city of 30,000 people in the United States.104 Yet within two months’ time SHAEF moved its main headquarters from London to Portsmouth to Granville to Versailles; Headquarters, COMZ, moved from London to Valognes to Paris; and Headquarters, 12th Army Group, moved four times.

Months earlier in London, plans had been set up for a phased, orderly move of COMZ to France as soon as two or more base sections had been established on the Continent.105 But the tactical situation did not develop according to plan, and when COMZ moved to the Continent the phasing plan was disregarded. As a result, communications of the kind and in the quantity desired could not be provided immediately. A COMZ forward party arrived on the Continent on 14 July; requisitions for communications materials went forward to the United Kingdom on 20 July, and the troops and materials arrived on 29 July. When COMZ headquarters opened at Valognes on 7 August, the Signal Section had had only nine days to prepare for it. Working under the supervision of a single staff signal officer, Lt. Col. Percival A. Wakeman, the 3104th Signal Service Battalion and a small detachment of the 980th Signal Service Company selected sites, constructed buildings, installed a complete 15-kilowatt radioteletypewriter station, and established a cross-Channel radio relay circuit. On 25 August Paris was liberated. The next day an advance group from COMZ entered the city to search for housing and facilities. Within two weeks COMZ headquarters moved into Paris, bag and baggage.106

General Eisenhower considered the precipitate move of COMZ from Valognes to Paris to be ill-advised, particularly since COMZ used up precious air and motor transportation for the move at a time when there was a critical supply shortage at the front, a circumstance that resulted in a deluge of criticism from combat commanders.107 General Eisenhower went so far as to tell the COMZ commander that he could not keep his headquarters in Paris.108

But from the communications standpoint, the move to Paris had been a logical one. Paris was the center of the cable, road, and railroad systems; it was “incomparably the most efficient” location for a communications zone headquarters and perhaps “the only entirely suitable location in France.”109 During the period when it seemed that COMZ would be forced to leave Paris, members of General Rumbough’s staff, working with a reconnaissance group looking for new locations, considered the communications possibilities of Versailles, Reims, and Spa. They concluded that “any move of Hqs, COMZ, outside the greater Paris area would seriously cripple its present communications and hence its efficient operations.” After a high-level meeting at SHAEF on 22 October, it was decided that COMZ need not move from Paris but must rigidly limit its personnel and the number of buildings it occupied.110

In spite of the potential advantages of Paris from a communications standpoint, the requisite facilities could not be

provided immediately. General Rumbough described the signal facilities he was able to provide during the first few weeks as “the best possible, but not adequate.”111 The fact of the matter was that a large headquarters had displaced from one location to another without adequate consideration of the ability of the signal officer to provide service at the new location.112

Until wire lines could be brought into Paris and facilities rearranged, a single SCR-399 brought in with the advance group on 26 August provided the main communications channel between Paris and Valognes. On 10 September signal engineers set up a radio relay circuit, the terminal located on top of the Eiffel Tower. Rumbough’s men brought landline printers and additional radio circuits into Paris when the major portion of Headquarters, COMZ, moved there. As quickly as possible during September the signalmen added new communications facilities. The fundamental difficulties in message handling during September lay in the shortage of reliable teletypewriter circuits between Valognes and Paris and between Paris and London. New direct VHF channels between London and Paris solved much of the difficulty. A major task, installing a 6-channel, long-range 40-kilowatt radio station, occupied scores of troops working in shifts twenty-four hours a day. The equipment for the station came packed in more than 1,000 individual boxes and crates, many of which had been severely damaged in shipment.113

Meanwhile, the various moves of SHAEF headquarters laid another heavy burden on the SHAEF Signal Section. SHAEF moved from Portsmouth, England, to the Continent at Granville on 1 September, despite a plea from General Vulliamy, the SHAEF chief signal officer, that the move be made no earlier than 15 September because of “signal considerations.”114 The signal center was set up at Jullouville, five miles south of Granville, in an area that had been heavily mined by the Germans. One signal officer was seriously injured and a truck loaded with equipment was destroyed by mines missed when the area was cleared. The signal offices were installed in portable huts; the thirty-two officers and thirty-nine enlisted men operating the facilities were housed in tents and trailers. The stay at Jullouville was short—on 20 September SHAEF Forward moved to Versailles.115 General Vulliamy, hoping for enough time to provide adequate telephone facilities at Versailles, was told that SHAEF main headquarters also would move there immediately.116 SHAEF was willing to accept a temporary reduction in communications facilities to gain political and tactical advantages by the move.117

On 5 October the main SHAEF headquarters moved officially. Actually, most of the staff officers had “infiltrated” Versailles during the two weeks the forward echelon had been located there. “The Signal Division ... was not given enough advance information as to installations required,” the historical

report of the division noted.118 Most of the men from the signal units, who should have been at work maintaining existing communications, had to be diverted to the task of completing urgently required new installations.119 Through the herculean efforts of Le Matériel Téléphonique a 3,000-line automatic exchange in the Petite Ecuries—Louis XIV’s stables was readied in the remarkably short time of five weeks.120

By mid-October communications matters at the Paris Signal Center were well in hand. The center and its associated military communications system were destined to become the largest ever established by any overseas theater. Within a year it rivaled the great signal center in Washington.121

Wire and radio, together with messenger service, were integrated into a smoothly functioning system—the sort of system that American commanders were wont to demand, wherever they were. In fact, it did not occur to them to expect anything less, accustomed as they were to the vast communications facilities available to them at home. By early 1945, most of the PTT cable systems in France and Belgium had been restored to service. Signal Corps troops had constructed many miles of open wire lines on important communication routes, while spiral-four and field wire served the forward areas. Approximately 1,660 wire circuits, incorporating an estimated 200,000 miles of wire facilities, operated in the COMZ.

VHF radio and manual radio telegraph systems supplemented and protected wire service. Paris was linked with WAR, the communications center of the War Department in Washington, by 2 complete multichannel and 2 single-channel radioteletypewriter systems, providing a total of 11 independent two-way radio circuits, and by 3 transatlantic cable circuits. The cable circuits had been established by restoring and diverting the German Horta-Emden cable. Before the war this cable had run from the United States through Horta in the Azores and Southampton, England, to Emden, Germany. British technicians severed the Southampton link. Specially trained Signal Corps crews terminated the cable and placed it in operation at Urville-Hague, near Cherbourg.122 Communication between Paris and the other theaters was provided through radioteletypewriter channels to Caserta and Algiers, or by relay through WAR. Fifteen to 20 miles of teletypewriter tape sped through the automatic-packaged teletypewriter assemblies daily, carrying a traffic volume of approximately 7,500 messages—1,500,000 groups.123

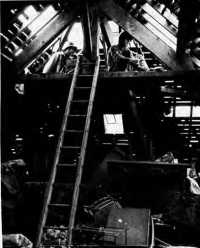

To serve the 4,000 military stations in the Paris area, there were about 40 local switchboards, several of which were PTT automatic exchanges. Cables interconnecting the various exchanges permitted the routing of local traffic from one to another, handling 35,000 local calls daily. Long-distance calls, through the Paris Military Switchboard, averaged 19,000

Paris Signal Center in German-built blockhouse

each day, 700 of them cross-Channel calls. Direct circuits from this board provided connections to each of the base sections on the Continent and in the United Kingdom, and to each of the army groups.124

The Signal Center had moved from the cramped, inadequate quarters in which it began operations in September to a new location. A 5-story concrete blockhouse built by the Germans a short distance from the Majestic Hotel offered suitable space. At the converted blockhouse, the Signal Corps installed tape relay and manual printer rooms, a radio operation room, crypto rooms, a message center, a radio control room, and conference rooms.125 Pneumatic tubes sped messages between this center and the classified message center in the Majestic Hotel. The radio control room was the first of its kind to be installed in the European theater. It was a technical center for controlling radio circuits and, in time, the entire tape relay network. All trouble shooting, distortion measurements, circuit rearrangements, and trouble analysis were controlled here by twenty-four highly trained men—nine officers and fifteen enlisted specialists. These men supervised the operation of the transatlantic radio, including the multichannel systems, VHF radio circuits, manual circuits, and high-speed circuits.126

The tape relay network was a part of ACAN, controlled by the Chief Signal Officer, Washington. The ACAN network consisted of the net control station in Washington, a network in the United States, and major trunk routes to overseas theater headquarters, where messages were relayed over the local networks of the individual theaters to their destination.127 Stations in the ACAN net received messages by any means—messenger, pneumatic tube, private line teletypewriter, and so on—from the originator. These stations placed the messages on the network. Intermediate relay stations received the messages on a tape by means of typing reperforators, and fed them on to the next relay on the net by means of high-speed transmitter

distributors. Relaying the messages by tape gave rise to the popular designation “tape relay network.” Users found that this system provided a faster and more accurate means of handling messages. By February 1945, eight major relay stations in the ETO were tied into the ACAN network. They included: SHAEF; Headquarters, Communications Zone and ETO; Headquarters, 12th Army Group; Headquarters, U.S. Strategic Air Force; Headquarters, United Kingdom Base; Headquarters, Normandy Base Section; Atlantic Cablehead, Cherbourg; and SHAEF Forward. Each of these relay stations had direct communications to Washington and to each other. There were six relay tributaries and twenty tributary stations in the network.128

Two WAC officers and 180 WAC enlisted women were on duty in the Paris Signal Center by early 1945. Fifty-four Signal Corps women of the 3341st Signal Service Battalion in fact constituted the first WAC contingent on duty on the Continent. They had arrived at Valognes on 14 July for service in the signal center there. Three WAC telephone operators took over the long-distance PTT board in Paris on the first day the French turned it over to the Allies. All together, five hundred Wacs served the Signal Corps in the COMZ as telephone operators, cryptographers, draftsmen, artists, clerks, and drivers of message center courier vehicles, releasing technically trained men for forward areas. The women operated their own messes and had their own administrative headquarters, the 3341st WAC Signal Service Battalion, activated in ETO, the first unit of its kind to be formed. These women on Signal Corps assignments represented 23.5 percent of all the WAC personnel in the Communications Zone, exclusive of the United Kingdom, approximately one Signal Corps woman to every 55 Signal Corps men in the area, as compared to one woman to every 234 men for the other services.129