Chapter 8: The Methodology of Army Requirements Determination

Some General Considerations

The Army’s requirement programs in World War II were the end result of many millions of detailed calculations made by many thousands of individuals in the Army’s complex organization in Washington, its numerous field establishments throughout the United States, and its far-flung network of organizations in overseas theaters. Each of these programs possessed its own basic assumptions and objectives, as formulated at high policy levels and spelled out in the directives and instructions which launched each individual program or recomputation. Indispensable to the development of all such programs was the underlying foundation of concepts, principles, and procedures which comprised the basic methodology of Army requirements determination.

With the heavy expansion of procurement during the defense period, the shortage of personnel experienced in applying the concepts and procedures of requirements determination was a serious handicap to the Army in computing, assembling, and presenting its requirement programs. Lack of knowledge in this area also handicapped the central mobilization control agencies in interpreting and screening military requirements. After Pearl Harbor the War Production Board had the task of appraising the validity of Army requirements as measured against the stated requirements of other claimants upon the nation’s supply of resources. It soon became evident that the ability to make intelligent allocations of national productive capacity presupposed a dependable knowledge of the considerations which entered the determination all down the line for each claimant agency. This required a lengthy process of indoctrination—usually when time was lacking—in basic methodological matters before the rationale behind a given estimate of requirements could be comprehended, much less evaluated.1

As in virtually every other area of its activities, the Army at the beginning of the second world war had an extensive body of doctrine to govern the determination of requirements. Underlying all specific procedures was the twofold logistical principle that supply should be adequate and so far as possible automatic:

... combat troops should not have their attention diverted from their task of defeating

the enemy by anxiety concerning questions of supply. The impetus in the movement of supplies and replacements should be given by the rear, which so organizes its services that the normal routine requirements are replaced automatically and without the preliminary of requisitions. ... Assurance of adequate supply necessitates provisions of the broadest character involving calculations ... as to probable requirements incident to the development of operations and as to the time required for supplies to reach the troops. ... Boldness in placing orders for equipment that will probably be required is essential.2

In application this principle meant that the determination of requirements would have to precede actual combat operations by from one to several years. Before such operations could take place, requirements estimates would have to be translated into appropriations, contracts, production schedules, procurement deliveries, and the distribution of matériel to the far corners of the earth.3 Requirements determination was thus an act of prediction, whose fulfillment depended upon a complex array of unknown future events only partly under the control of those making the prediction. In view of this basic condition of uncertainty and the tremendous issues at stake, it was a fundamental principle of Army supply that all doubts were to be resolved in the direction of oversupply rather than undersupply. The worst kind of failure of a military supply system was conceived to be one which could be summed up in the words “too little and too late.”

The most difficult phase of requirements determination in World War II—from the standpoint of successful prediction—was the period in advance of the actual outbreak of war and up to the time when strategic plans had been crystallized, theaters of operations established, and rates of munitions consumption determined on the basis of current experience. It necessarily followed that, until long after Pearl Harbor, Army requirements rested upon broad considerations of the anticipated size and composition of the Army, generalizations regarding the character of its equipment needs, and a wide array of more or less arbitrary assumptions as to rates of equipment loss, ammunition expenditure, and other operational requirements. With the progress of the war, the concept of automatic supply based upon long-range estimates of future needs was substantially modified. Automatic supply gave way in large measure to supply on the basis of specific requisitions from theater commanders. This permitted procurement and issue of supplies more closely tailored to specific theater needs, as indicated by operational experience and changes in strategic plans.4

Broadly speaking, the Army’s matériel requirements for World War II, as in other wars, fell into two classes—equipment and expendable supplies. Equipment items—such as clothing, rifles, tanks, trucks, and planes—were analogous to “capital” items in industry: they had a relatively long life and were normally “used up” only after repeated operations of the type for which they were designed. Expendable supplies, on the other hand, were comparable to “operating supplies” in industry and characteristically could be used only once. Expendables consisted of such items as subsistence, ammunition, various medical supplies, fuels, and lubricants.

This simple classification into equipment and expendables was the basis for the Army’s broadest division of principles, terminology, and procedures in determining its requirements. Important logistical considerations demanded, however, a further classification which would recognize important differences in the character of demand for the various items of supply, and hence procurement. From this standpoint there were at least three major types of item: (1) items of regular or standard issue whose quantitative requirements depended primarily upon the size of the Army (subsistence, standard allowances of personal and organizational equipment); (2) expendable items whose demand fluctuated widely with variations in the intensity of combat (ammunition, aviation gasoline for fighters and bombers); (3) special equipment subject to urgent but often sporadic demands arising out of major strategic plans and operations and numerous special projects. Among the activities requiring special equipment were intensive overseas shipping operations, the creation or rehabilitation of port facilities, the clearing of sites for airfields, the building of transportation and communication systems in undeveloped areas, and a host of other construction projects at home and abroad. Equipment required for such operations included bulldozers, steam-shovels, cranes, troop transports, tugboats, locomotives, rails, telephone poles, electric wire, lumber, concrete, and so on. Obviously, no clean-cut classification could be developed to reflect accurately all the various logistical considerations. The Army’s approach to the problem was the use of five standard classes of supplies, some of which in turn were further subdivided. Two of these classes (II and IV) consisted primarily of equipment items; three of them (I, III, and V) represented expendable supplies.5 This classification of procurement items according to the nature of demand for them was an important tool in the formulation of policies, such as the establishment of differential reserve levels, designed to insure adequacy of supply. Computed requirements were not, however, published in terms of this classification.

A third classification of procurement items was made, as already seen, on the basis of distinctions in their characteristics of supply, rather than of demand. In order to state requirements in terms of the difficulty

of procurement, items were classified as “critical” or “essential.” Critical items were those which required a long production period, generally a year or more. These were the items which required extensive conversion of industry, the development of new and difficult production skills, special machinery and equipment, and the solution of complex problems in research and development, material substitution, and other barriers to rapid production. In the critical category were ships, planes, tanks, guns, ammunition, surgical instruments, blood plasma, penicillin, and other items which as a whole or because of the inclusion of complex components were difficult and slow of production. Essential items were in many cases no less necessary to the Army than critical items, but they were obtainable on shorter notice, either through regular commercial channels or under special contracts involving relatively little industrial conversion. Essential items included a large number of Quartermaster items—numerous articles of clothing and personal equipment, food, soap, paper products, and miscellaneous housekeeping supplies—as well as larger items which American industry was well equipped to produce in large quantities on relatively short notice. The distinction between critical and essential items was most important during the defense period and the first year of the war. At this time the requirements for critical items were based on a planned force of approximately double the size of that for which essential items were stated.6 The purpose of stating requirements for critical items on an augmented basis was to make sure of their procurement and delivery—despite their lengthier production periods—in substantially the time needed to meet actual schedules of troop activation and deployment. As indicated above, the point of departure in computing total Army requirements was the broad distinction between equipment and expendable items. Equipment requirements, as visualized throughout most of World War II, were composed of three principal elements—initial issue, replacement, and distribution. Requirements for expendables, on the other hand, were computed in terms of only two elements—consumption and distribution. The relative importance of the several elements, as well as the methods of their computation, changed substantially with the progress of the war.

Equipment Requirements Initial Issue

“Initial issue” consisted of all types and quantities of equipment needed to outfit the expanding Army in its growth from barely 200,000 men at the beginning of 1940 to over 8,000,000 in 1945. It included standard allowances of post, camp, and station equipment in the United States as well as personal and unit equipment for organized components of the Army as these were activated and moved into overseas theaters of operations. In addition to standard allowances, initial issue also included exceptional issues to troops of all organizations,

special allowances for task forces, and equipment for construction and other operational projects.

Most initial-issue requirements were determined by multiplying unit allowance figures by the number of units to be equipped. Unit allowance figures were obtained from official allowance tables published and kept current by the several using arms and technical services of the Army. The number of units to be equipped was obtained from the troop basis. Because of the apparent simplicity of multiplying known figures and summarizing the resultant totals, the determination of initial-issue requirements was commonly thought to be the easiest of the several stages in requirements determination. Actually, the process was unbelievably complicated, not only because of the multitude of items, sources of information, and other considerations involved, but because these were all subject to constant change. Moreover, the two basic determinants of Army requirements—the troop basis and unit allowances—were themselves mutually determining. A troop basis could not be developed without a preconceived pattern of unit allowances, and the composition of unit allowances in turn depended upon fundamental preconceptions as to the organization and structure of the Army as a whole.7

The Troop Basis—The troop basis was the most important variable in the determination of Army requirements. Prepared by the General Staff (G-3 in conjunction with OPD), the troop basis was the Army’s official troop mobilization program, indicating the total number of armies, corps, divisions and miscellaneous supporting units—engineer, ordnance, chemical warfare, signal, cavalry, field artillery, and others—scheduled to be in existence at the end of each calendar year for two years, and sometimes longer, in the future. The heart of the troop basis was the number of Army divisions classified by types—infantry, armored, motorized, airborne, mountain, and the like. The troop basis indicated the number of enlisted men composing each type of unit and referred to the governing tables of organization for further details. A summary of the troop basis as it appeared at the end of 1942 is presented in Table 22.8

The troop basis was subject to change from time to time and any major change in it called for a recomputation of matériel requirements. Before Pearl Harbor the troop basis for procurement consisted of the several components of the Protective Mobilization Plan force, and matériel requirements to support the PMP were programed as funds became available. For broad purposes of industrial mobilization, the Munitions Program of 30 June 1940 established basic procurement objectives for forces of one million, two million, and four million men in terms respectively of essential items, critical items, and the creation of industrial capacity. As the Munitions Program got under way and the danger of war increased, the various PMP force requirements were successively raised to levels above those in the Munitions Program. Finally, in the fall

Table 22: Victory Program Troop Basis: Summary of 15 December 1942 Revision

| By 31 December 1943 | By 31 December 1944 | ||||

| Unit | Enlisted Strength per Unit | Number of Units | Total Enlisted Strength | Number of Units | Total Enlisted Strength |

| U.S. Army-Total a | – | – | 7,500,000 | – | 9,000,000 |

| AAF, Replacements, and Overhead-Total | (c) | (c) | 3,085,304 | (c) | 3,386,491 |

| Ground Units-Total | (c) | 6,806 | 4,414,696 | 8,204 | 5,613,509 |

| Headquarters | - | 36 | 14,696 | 46 | 19,052 |

| Field Armies | 778 | 9 | 7,002 | 12 | 9,336 |

| Corps | 279 | 20 | 5,580 | 24 | 6,696 |

| Armored Corps | 302 | 7 | 2,114 | 10 | 3,020 |

| Divisions | - | 116 | 1,627,779 | 148 | 2,066,617 |

| Airborne | 7,970 | 10 | 79,700 | 14 | 111,580 |

| Armored | 13,796 | 26 | 358,696 | 35 | 482,860 |

| Cavalry | 11,476 | 2 | 22,952 | 2 | 22,952 |

| Infantry | 14,758 | 61 | 900,238 | 70 | 1,033,060 |

| Motorized | 16,085 | 13 | 209,105 | 17 | 273,445 |

| Mountain | 14,272 | 4 | 57,088 | 10 | 142,720 |

| Supporting Units b | – | 6,654 | 2,772,221 | 8,010 | 3,527,840 |

| Armored (4) | Various | 68 | 39,054 | 112 | 62,379 |

| Cavalry (2) | Various | 22 | 36,040 | 26 | 42,272 |

| Chemical (8) | Various | 220 | 57,338 | 260 | 68,002 |

| Coast Artillery (21)_ | Various | 1,348 | 789,617 | 1,717 | 1,006,971 |

| Engineers (23) | Various | 435 | 302,368 | 563 | 403,328 |

| Field Artillery (16) | Various | 421 | 201,206 | 580 | 277,885 |

| Infantry (4) | Various | 58 | 173,430 | 62 | 180,966 |

| Medical (29) | Various | 1,089 | 287,631 | 1,453 | 392,160 |

| Military Police (6) | Various | 347 | 119,706 | 428 | 136,060 |

| Miscellaneous (9) | Various | 631 | 15,675 | 297 | 18,046 |

| Ordnance (21) | Various | 995 1 | 205,336 | 1,167 | 240,462 |

| Quartermaster (20) | Various | 469 | 232,242 | 591 | 279,635 |

| Signal (21) | Various | 256 | 100,069 | 320 | 122,853 |

| Tank Destroyer (4) | Various | 184 | 128,213 | 286 | 189,325 |

| Transport. Corps (9) | Various | 111 | 84,296 | 148 | 107,496 |

a Includes AAF, as well as troops in training, replacements, etc., for ground forces.

b Figure in parentheses after each class indicates the number of distinctive types of unit in each class. Types of unit consisted of various

kinds of specialized regiments, brigades, battalions, companies, or other groups.

c Not available.

Source: Adapted from Frank, Requirements, Docs. 72 and 75.

of 1941, the preparation of the Victory Program estimates marked the first statement of troop requirements considered to be necessary in order to win a full-scale war. As already indicated, at the time of its preparation the Victory Program was not adopted as an actual program of troop activation or matériel procurement. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, however, a troop basis was adopted which in size and composition was largely in keeping with the earlier Victory Program estimates.9

It was during 1942 that the great problems and controversies arose in connection with the establishment of a sound troop basis. Two major, interrelated questions predominated: What shall be the ultimate size of the Army? and What shall be its structural composition? The smashing successes of Hitler’s armored divisions in Europe had indicated the need for a heavily armored and mechanized Army. Hence, the troop basis for the U.S. Army as conceived in 1941 and early 1942 was heavily weighted with armored and mechanized divisions, calling for a far greater physical and dollar volume of procurement than would an army of the same size composed chiefly of infantry and other more lightly equipped divisions. The total size of the Army, estimated to reach nearly 10.5 million men in 1944, likewise called for matériel requirements huge in comparison with the program eventually carried out.

A number of influences, including the Feasibility Dispute already discussed, emerged in the course of 1942 and thereafter to compel a reduction in the planned size of the Army and even greater changes in its structure. A fundamental consideration was the lack of shipping capacity to move troops and supplies overseas; the mobilization of a huge Army, only to let it be frozen in the United States thousands of miles from combat areas, would be a wasteful undertaking.10 The shortage of rubber, steel, and other materials, together with a re-examination of the strategic and tactical roles of armored, motorized, and other heavily mechanized divisions, led to successive reductions in these units. Increased emphasis on the importance of the air arm, the need for larger numbers of service troops, and growing indications of a manpower shortage dictated still further reductions in the size of the ground forces.

Early in 1942, the troop basis called for a total (by the end of 1944) of 213 divisions—including 88 infantry, 67 armored, and 34 motorized. By the end of 1942 these figures had shrunk to a total of 148 divisions, with 70 infantry, 35 armored, and 17 motorized. (See Table 22.) But this was barely half the reduction which was ultimately to take place. The final number of divisions activated by the U.S. Army in World War II was only 89—including 66 infantry and 16 armored; motorized divisions had been reconverted to standard infantry divisions and were discontinued as a separate type. Instead of attaining the early 1942 objective of 10.5 million men,

the actual peak strength reached by the Army in 1945 was 8,291,336.11

The troop basis was a fundamental determinant of requirements for replacement and distribution as well as for initial issue and applied to expendable supplies as well as to equipment. Since the troop basis was prepared for long-range planning purposes, it frequently differed both from the shortrange troop activation schedules prepared by G-3 and from actual inductions and activations. Furthermore, the broad estimate of overseas shipment and deployment of troops to theaters of operations, as contemplated by the troop basis, was normally at variance with actual troop movements. This was inevitable in view of the many barriers to either the formulation or the perfect execution of complex plans for the mobilization, training, equipment, and transportation of millions of men for service in all parts of the world.

The disparity between different plans, as well as between plans and execution, occasionally reached sizable proportions and was a cause of frequent difficulty in determining and reconciling matériel requirements. In mid-1943, for example, the current revision of the Victory Program Troop Basis provided for 8.2 million men by the end of 1943, while the activation schedule of G-3 indicated activations not in excess of 7.6 million. The 15 August 1943 edition of ASP was computed on the larger basis, as directed by the Chief of Staff, to provide a strategic reserve of equipment to meet contingencies and exploit favorable developments in combat operations.12

The strategic reserve was originally decided upon in November 1942 and was approved by the Chief of Staff and the President. The purpose of the reserve was to provide for the sudden activation of additional troops, either of the United States or of liberated forces in occupied countries, as circumstances and opportunities might require. The 1 February 1943 ASP contemplated a strategic reserve by the end of 1944 of approximately 20 percent of initial equipment needed to support the 7,500,000 U.S. troops then planned for activation. Since the strategic reserve omitted various categories of equipment and supplies, the computation of requirements to meet the reserve introduced many additional complexities into the task of requirements determination. The Richards Committee late in 1943 recommended the reduction of the planned strategic reserve by some 50 percent.

As a result of these recommendations and other developments, the Victory Program Troop Basis was revised and brought into line with troop activation schedules. A related development in the last year and a half of the war was the refinement of the troop basis to show expected troop deployment on a theater-by-theater basis. Only with such a breakdown was it possible to apply revised replacement and distribution factors which were also by this time developed on an individual theater basis.13

Unit Allowances—The second basic factor in the computation of requirements for initial issue consisted of unit allowances. Unit allowances were specified in allowance tables which at the beginning of the war were of two broad types: tables of allowances (T/A’s), covering equipment issued at posts, camps, and stations, mostly in the zone of interior; and tables of basic allowances (T/BA’s), covering equipment issued to organized units of the Army. In general, equipment issues authorized by T/A’s were based on the functions and capacity of individual stations and remained at the installations concerned; such equipment included a multitude of camp and station furnishings, motor vehicles, and training equipment, in addition to personal clothing and other items required to administer the induction, training, and utilization of troops before their assignment to permanent, organized units of the Army. Equipment issued under T/BA’s, on the other hand, became the property of organized units and moved with the individual divisions, regiments, and other units from station to station and ultimately into theaters of operations. T/BA’s showed the full complement of allowances to individuals (clothing, blankets, personal equipment, and similar items per man) as well as allowances to organizations (number of vehicles, heavy weapons, signal items, and other units of equipment per company, battalion, regiment, and so on).14

The task of formulating and keeping up to date the Army’s numerous allowance tables was a formidable one. New items of equipment were constantly being developed and standardized, and old ones eliminated. Quantities of standard items were increased or reduced as wartime experience accumulated. A multiplicity of factors entered into decisions to change allowances and it was difficult to obtain relevant and accurate information; opinions were often conflicting and evidence fragmentary; the issues involved ran the gamut from the aesthetic qualities of the “Eisenhower jacket” to the role of basic weapons and equipment in modern warfare. The availability of raw materials and substitute items, the general procurement situation, and many other considerations besides purely military ones all played a part in the adoption of items for general issue purposes.15

As the war progressed the Army tightened its procedures for determining its allowances and for publishing and disseminating information on changes therein. Allowance tables were systematically reviewed in an attempt to reduce or eliminate items of equipment not strictly essential to the accomplishment of the mission of the organization

concerned.16 Numerous scattered allowance tables, which before the war had been issued by each of the fourteen using and supply arms, were combined into fewer publications. On 1 October 1941, the Quartermaster Corps issued its consolidated T/BA 21, covering all Quartermaster clothing and individual equipment regardless of using arm or service. This led to the separation of personal from organizational equipment in official allowance tables. In October 1942, tables of equipment (T/E’s) were introduced to cover all organizational equipment needed by units described in official tables of organization (T/O’s). By August 1943 tables of equipment had been combined with tables of organization to become tables of organization and equipment (T/O&E’s). Thereafter all allowances of personal clothing and equipment were published in tables of clothing and individual equipment.17

The computation of initial-issue requirements would have been far from simple even if a stable troop basis and unchanging allowance tables had prevailed throughout the war. Difficulties in adopting and using standard nomenclature and classification systems for the many tens of thousands of Army procurement items gave perennial trouble; standard allowance tables necessarily permitted discretionary issue of many items by troop commanders in the field; and production limitations dictated that the issue of both essential and critical items to troops in training be restricted to certain percentages of authorized allowances. Not only did the technical services have to make conjectures as to probable authorization of optional issues; they also were required to develop and apply probability factors as a basis for size tariffs and requirements based on variable allowances.18

Special Projects—Perhaps the most difficult task in computing initial-issue requirements fell to the Corps of Engineers and the Transportation Corps, both of which had to determine needs for complex and heavy items of equipment required for special operational projects. To the Transportation Corps fell the assignment of determining the considerable fleet of vessels and other transportation equipment which would be needed by the Army to carry out its mission. Army vessels in World War II included large and small transports, landing craft, lighters, ferries, tug boats, and motor launches.19 Railway items procured by the Transportation Corps included locomotives, rolling stock, thousands of miles of track, and a wide assortment of related equipment. The Corps of Engineers was responsible for anticipating the Army’s eventual needs for construction equipment and materials, port rehabilitation equipment, tractors, bulldozers, cranes, bridging equipment, aircraft landing mats, and many other major items of special equipment.

Equipment for special projects could not be specified in regular allowance tables but was of vital importance to the ultimate success of the Army’s basic mission. Moreover, it consisted largely of long-term, difficult-toproduce items whose requirements had to be determined at least eighteen months in advance of use. During the early stages of the war when Allied strategy was still in the process of formulation, the ASF was unable to obtain from either the General Staff or theater commanders anything like firm, long-range operational plans upon which to base special project requirements:

It just seemed impossible to get the Staff to understand the importance of lead time in production. This was ... true of strategic and operational plans which affected in large measure the supply of equipment in addition to the basic troop equipment. Firm decisions on these plans were seldom made sufficiently far in advance to meet the required lead time for production. It was necessary for Army Service Forces to do its own strategic and operations planning in an attempt to outguess the Joint and Combined Chiefs of Staff; otherwise we would not have been in a position to meet supply requirements of the operation finally decided upon.20

Many of the difficulties experienced by the ASF in determining special project requirements were removed as Allied strategy solidified and theater staffs accumulated field experience. In planning the Normandy invasion, for example, the European Theater of Operations (ETO) as early as August 1943 submitted requests for equipment and materials for the huge reconstruction project anticipated for the port of Cherbourg. Procurement directives to obtain the needed items were issued within the month –

eight months before the actual invasion.21

The basic dilemma faced by Army planners in attempting to gauge special project requirements long in advance of actual need was simply the fundamental problem faced in the determination of all Army requirements involving a significant production period. This dilemma was aptly summed up by the War Department Procurement Review Board in 1943 after scrutinizing the validity of Army requirements in general:

Those charged with procurement are in an onerous and difficult position. If they hold up production on items which take a long time to produce, they may jeopardize an important military operation for want of material at the time it is needed. If they produce in advance of demand and the demand does not materialize, they may be charged with waste and unnecessary extravagance.22

Replacement

The Army’s replacement requirements represented the quantities of equipment needed to offset losses after initial issue.23 As soon as equipment was issued, it was subject to loss through depreciation, destruction, capture, abandonment, pilferage, and other causes. Actual loss rates varied widely both within and between theaters of operations because of differences in climate, terrain,

intensity of combat, and other influences. They also varied within the zone of interior, depending upon whether equipment was intensively used in training activities or merely awaited overseas shipment. Because of the many uncertainties involved, even after combat experience was available, accurate prediction of replacement requirements was an ideal which could only partially be realized.

For most of World War II the Army determined its replacement requirements by the use of replacement “factors” which were multiplied by total initial issue to yield total replacement needs. Replacement factors were percentage figures indicating the estimated average monthly loss of each type of equipment from all causes.24 A 5-percent factor indicated an average life expectancy of twenty months for the item involved. To keep a given force fully equipped for a full year, assuming an even loss-rate of 5 percent per month, would thus call for a replacement supply equal to 60 percent of initial-issue requirements.

Replacement factors were determined on the basis of a wide variety of considerations and were changed from time to time to reflect the latest dependable information. Until the middle of 1944, only two factors were specified for each type of equipment—one applicable to the zone of interior, and one (usually higher) for all theaters of operations collectively.

In using replacement factors, it was necessary to determine from the troop basis the anticipated average strength of overseas forces in each year in order properly to apply the theater of operations rates of replacement to total initial issues of equipment which would be in use overseas. This consideration led to the adoption of techniques of computation which promoted considerable confusion and led to estimates of doubtful accuracy throughout a large part of the war. In order to standardize and simplify machine computations and associated procedures, it was desirable to relate the various segments of total requirements for each year to the single end-of-the-year strength figure as shown in the governing troop basis. Thus, in the first edition of the Army Supply Program (6 April 1942) the estimate of the average number of troops to be sustained overseas throughout the year was roughly 25 percent of the total end-of-period strength called for by the troop basis:

| Item | 1942 | 1943 |

| Total end-of-year strength | 4,150,000 | 8,890,000 |

| Average overseas strength | 1,000,000 | 2,250,000 |

For computational purposes, instead of directly prescribing a year’s combat replacement requirements for the 1 million and 2.25 million men serving overseas for 1942 and 1943, the governing directive called for three months’ (25 percent of one year) replacement requirements at theater of operations rates for the entire terminal strength, which was approximately four times as large as the anticipated average overseas force in each year. Although the actual number of months used for this purpose gradually shifted upward with the relative increase in overseas deployment, this method of computing overseas requirements, both for replacement and distribution (especially theater levels), was standard practice until 1944 when separate replacement factors and troop deployment figures were made available on a theater-by-theater basis. An analogous procedure was used for determining replacement requirements

for troops in the zone of interior, employing the lower replacement factors appropriate to the ZI.25

Apart from errors resulting from the assumption that all theater forces were collectively composed of units reflecting the same composition as that of total forces contemplated by the troop basis, this method augmented the possibility of error common to all factor methods for determining requirements: a small change in a factor would result in a large change in total requirements when the factor was used as a multiplier against large magnitudes. Thus the number of months selected as the overseas multiplier became an independent and important factor itself, superimposed upon the underlying replacement factors which were themselves subject to error. Throughout 1942 and 1943 it was the practice to express this number of months in round-unit figures for computing replacement requirements; for computing stock-level requirements the multiplier was rounded to the nearest half month. Inasmuch as actual troop activations in 1942 and 1943 fell far below the end-of-year strength figures expressed in the troop basis (a difference of around 1.5 million men for 1943), it can be seen that the method of determining replacement and distributional requirements had a heavy upward bias. This result was augmented by overestimates of average, as opposed to end-of-year figures, and even more by the lag in downward revision of replacement factors to reflect equipment loss rates that were lower than anticipated throughout the war.26

The specific rate of replacement called for by each of the Army’s numerous and widely divergent, individual replacement factors was a matter of historical evolution. In the late 1930s the factors consisted largely of those inherited from World War I. Numerous changes in the types and uses of equipment, the quality of materials and construction, the destructiveness of enemy weapons, and other elements all combined to render the old factors obsolete. In December 1937 the General Staff ordered an annual revision of all replacement and distribution factors. At that time the Ordnance Department appointed a special board of officers, headed by Col. Clarence E. Partridge, to study the entire problem of replacement and distribution requirements. The resulting report (known as the Partridge Report) appeared on 13 June 1938 and made a substantial contribution to the theory of requirements determination.27

After the Partridge Report staff planners made efforts to obtain recent replacement data from German as well as British and French sources but the results were generally unsatisfactory. During this period the Army drew heavily upon the findings of development and testing personnel, recommendations

of the using arms, and the experience of private industry with comparable items. Nevertheless, on the eve of Pearl Harbor many of the factors were admittedly artificial and could only be corrected in the future as information on current battle experience and other operations became available.28

With the March 1942 War Department reorganization, the function of supervising the determination of replacement factors formerly exercised by G-4 was transferred to the Allowance Branch of the Requirements Division, ASF. In September 1942 the Allowance Branch proposed the semiannual submission by theater commanders of reports on the adequacy of existing factors for both replacement and distribution in the light of current field experience. This proposal was rejected by the Control Division, ASF, on the ground that such reports would be too general and too infrequent to be of significant help under the rapidly changing conditions prevailing at this stage of the war. Moreover, throughout the early phases of the war, it was established policy to keep theater reporting and paper work to an absolute minimum.

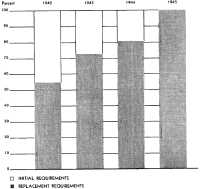

Nevertheless, the pressure for improvement in the quality of replacement factors continued. As early as the summer of 1942 the Quartermaster Corps had questioned the basic methods for determining distribution requirements, and these were intimately related to the determination and use of replacement factors. But the greatest impetus to increased attention to replacement factors was the steadily rising proportion of total Army requirements represented by replacement needs as the war progressed. Replacement needs rose from around half of total requirements for 1942 to virtually 100 percent of all requirements for 1945. (Chart 2)

The shift from initial issue to replacement as the dominant element in Army requirements had important implications for the task of requirements determination. As already indicated, the basic method of determining replacement needs lent itself to astronomical variations in total requirements. An increase from 4 to 8 percent in the monthly replacement factor for an item with an initial issue of two per man for an eight-million-man Army would increase annual replacement requirements by 7,680,000 units. In the early part of the war, substantial overestimates in replacement requirements for one million or two million men might easily be absorbed in the subsequent combat operations of a much larger force. Clearly, the need for accuracy in the determination of replacement requirements would attain urgent proportions as the war reached its maturity.29

On the other hand, if events proved that replacement factors had been set too low, major combat operations at the crucial stage of the war might be seriously jeopardized. To be sure, the Army provided reserve stocks for such contingencies but the time lag between requirements determination and procurement delivery of critical items as expressed in months was often

Chart 2—Approximate Ratios of Initial and Replacement Requirements to Total Army Requirements, 1942-45*

* Includes distribution attributable to replacement.

Source: ASF Manual, Determination and Use of Maintenance Factors and Distribution, July 1943, p. 32.

double the number of month’s supply represented by combined stock levels. In any case, whether from the standpoint of avoiding wasteful procurement or insuring the adequacy of supply, it was necessary for the Army early in 1943 to undertake the most careful refinement of its estimates of replacement needs for 1944 and 1945. In view of all these considerations the Army began in 1943 an intensive program which eventually resulted in basic changes in its methodology of requirements determination.

In February 1943 a separate Maintenance Factor Section was set up in the Program Branch of the Requirements Division, ASF. This section was charged with the establishment of basic methods and procedures to be followed by all the technical services in the determination and application of replacement and distribution factors. Almost immediately the new Maintenance Factor Section prepared for general use a memorandum stressing the importance of accurate replacement factors, defining numerous associated terms and concepts, and specifying procedures to be followed in gathering information from all sources for the purpose of bringing the factors up to date. Each technical service was directed to submit twice a year, in time for the semiannual revision of the Army Supply Program, a complete list of all current replacement and distribution factors under its cognizance.30

On 24 June 1943 theater commanders were directed to submit reports, at least quarterly, on all equipment losses and expenditures of ammunition and other important supplies in their respective theaters for the period in question. Commanders were requested to submit their estimates of the reliability of such data for the forecasting of future requirements. At the same time it was announced that specially trained officers would be sent to each theater to assist commanders in collecting the required data, to remain on temporary duty status until 1 October 1943. Thereafter it was expected that additional personnel regularly assigned to theaters would discharge this responsibility.31

In July 1943 a comprehensive manual—prepared by the Maintenance Factor Section—was issued by the War Department, expanding, revising, and consolidating all outstanding regulations and procedures for the determination and application of replacement and distribution factors.32 By this time field teams representing each of the technical services were being organized and trained for the conduct of replacement factor surveys at posts, camps, stations, and depots in the zone of interior. As data on actual rates of replacement accumulated from both the ZI and theaters of operations throughout the remainder of 1943 and 1944, the Maintenance Factor Section made numerous changes—for the most part downward—in the individual factors for Army equipment. During the last six months of 1943, factor changes were made for 796 supply items. Of these 713 were downward revisions. Thus, the theater of operations factor for service shoes, which on 15 June 1943 had been lowered from 20.2 percent to 16.7 percent, was further reduced on 15 December 1943 to 14.2 percent. The theater of operations factor for tractors (Corps of Engineers equipment) was reduced on 30 August 1943 from 8 percent to 4 percent.33

Major refinements in the determination of replacement requirements took place in 1944. Since late in 1942 there had been

pressure from within the Requirements Division, ASF, as well as in certain of the technical services, to treat each theater of operations individually in the determination and use of replacement factors. Under the existing system, which used an over-all combat replacement factor for all theaters, the Army’s total replacement requirements were subject to wide margins of error, especially in view of the deployment of increasing numbers of troops to areas differing widely in actual equipment loss rates. In June 1944, for example, data revealed that .30-caliber carbines were used up at the rate of only 0.4 percent per month in the North African Theater of Operations (NATO) but 9.3 percent in the South Pacific. Bayonets were replaced at the rate of 0.85 percent in NATO but 13.5 percent in the South Pacific Area. Trench knife replacements were twenty-five times as great in the South Pacific as in NATO, with a rate of 31.4 percent as compared to 1.26 percent.34 For large items of equipment smaller differences between theaters would still exert an important influence on total requirements. Furthermore, as replacement factors were used more and more for the actual distribution of matériel to the various theaters, it was important from the supply as well as the procurement point of view to develop a more discriminating yardstick of individual theater needs. But the use of separate theater factors awaited the development of two prerequisites: information on individual theater loss rates, and a troop basis showing anticipated deployment by separate theaters.

In preparing for the determination of separate theater factors it was necessary greatly to increase the flow of information and experience data from the several individual theaters. The War Department Procurement Review Board in 1943 had noted the reluctance of theater commanders to become involved in paper work:

They share the impatience of the Duke of Wellington who said, in effect, “On with the campaign and an end to quill driving.” But modern war does not parallel the campaigns of the past. ... In the United States whole industrial system has been realigned so that our productive effort may have its maximum effect on the field of battle. . Inventory control may have a vital effect on the outcome of the struggle, and overseas commanders should be conscious of the fact that it is not “quill driving,” but an essential part of strategic planning.35

In accordance with the McNarney Directive of 1 January 1944, the commanding generals of the six major theaters were directed on 10 February 1944 to submit each month a comprehensive Report of Material Consumed for a long list of supply items classified by procuring technical service.36 Data called for in the report included quantities of authorized allowances in the theater, losses, loss rates, and theater recommendations as to future replacement factors. Brief experience under this directive revealed that equipment actually in the hands of troops varied greatly from authorized allowances. This resulted in erroneous loss rates, since the rates were determined by relating issues to total allowances. On 14 May 1944 the instructions were amended to require all theaters to report actual quantities on hand with troops each month and to compute loss rates on this basis. This was a laborious assignment, especially since the reports eventually required a breakdown between

active and inactive equipment within each theater.37

The first step in the use of separate theater factors was taken in July 1944 when all theaters were grouped into two major areas for factor purposes: the European area (including ETO and NATO) and the Pacific area (including the Central, South, and Southwest Pacific Areas and the China-Burma-India theater). Separate factors were established for the two major areas and requirements in the next edition of the Army Supply Program were computed on this basis.38 By the end of 1944 the War Department was able for the first time to publish and apply separate factors for each of its six major theaters, in addition to the zone of interior. Theater commanders were notified of the change on 9 December 1944 and the new factors were published the following week.39 In the meantime, the War Department troop basis had been refined to show troop deployment by individual theaters. Thereafter until the end of the war, replacement factors, as well as consumption factors for a number of expendable items, were maintained on an individual theater basis.

An indication of replacement factor magnitudes at specified dates may be found by reviewing figures for selected items of equipment for several technical services. (Table 23.) A portrayal of the life histories of the replacement factors covering each of the many thousands of individual items of Army equipment throughout World War II would make a fascinating story. Such a story would reveal the impact of many forces—changes in the strategy, intensity, and character of warfare, improvement or deterioration in the design, quality of materials, and construction of equipment items, the complexities and shortcomings of methods of requirements determination, and many other elements—all influencing the determination of the individual factors at various dates. One or two abbreviated examples will serve to illustrate the point. In mid-1944 the combat replacement factor for the M4 medium tank stood at 9 percent. Battle losses of 559 tanks in one month, after the Allied breakthrough of the Normandy hedgerows in July 1944, led to a change in the factor to 11 percent. In the autumn, increased German resistance resulted in more losses in excess of planned rates and the factor was increased to 14 percent. On 1 January 1945, after still more losses in the Ardennes, the factor was again increased, this time to 20 percent. During the same period the replacement factor for the 60-mm. mortar was doubled, rising from 15 to 30 percent per month; for the Browning automatic rifle the rate moved from 15 to 28 percent. Similarly, the combination of adverse weather conditions and sustained activity in the ETO in the winter of 1944-45 led to the widespread development of trench foot among U.S. troops. The daily change of socks ordered to alleviate this condition resulted in an increase in the replacement factor for the cushion-sole, wool sock from 11.1 to 25 percent, heavily affecting

Table 23: Monthly Replacement Factors for Selected Items of Army Equipment at specified dates

| 1942 a | 15 Dec 43 | 15 Jun 44 b | 15 Dec 44 c | |||||||

| Item | Z/I | T/O | Z/I | T/O | Z/I | ETO Area | PAC Area | Z/I | ETO | SWP |

| Ordnance | ||||||||||

| Howitzer, 105-mm., M2A1 | (e) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 3 |

| Rifle, cal. .30 M1 | (e) | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 5 | 3 |

| Tank, Medium | (e) | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0. 5 | 9 | 9 | 0. 5 | 14 | 10 |

| Signal | ||||||||||

| Radio, SCR-193 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 5.5 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 4 |

| Radio, SCR-536 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 15 | 2 | 13 | 13 | 2 | 20 | 13 |

| Wire, W-110 | 5 | 50 | 4 | 44 | 4 | 75 | 50 | 4 | 100 | 75 |

| Corps of Engineers | ||||||||||

| Grader, Road, Mtzd | 1 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 8 |

| Roller, Road, Sheepsfoot | (e) | (e) | 0.5 | 3 | 0.5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 8 |

| Tractor, Crwl, Type | (e) | (e) | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Chemical Warfare Service | ||||||||||

| Flamethrower, Portable | 5 | 10 | 2.8 | 16.6 | 2.8 | 12.6 | 16.7 | 2 | 8.3 | 8.3 |

| Mask, Gas, Service | 3 | 12 | 2. 1 | 8.3 | 2.1 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| Mortar, Cml., 4.2" | 1 | 3 | 0 | 12.5 | 0 | 10 | 12.5 | 0 | 7 | 8.3 |

| Medical Department d | ||||||||||

| Blanket. White | 3.6 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.5 | 1. 5 |

| Kit, First Aid, 24-Unit | 2 | 4 | 2.5 | 5 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0. 7 | 0.7 |

| Sulfadiazine, USP, (Class 9) | (e) | (e) | (e) | (e) | 20 | 220 | 220 | 30 | 220 | 220 |

| Quartermaster Corps | ||||||||||

| Breeches, Cotton, Khaki | 8.3 | 25 | 5.6 | 11.1 | (e) | (e) | (e) | (e) | (e) | (e) |

| Cot, Folding, Canvas | 2.8 | 8.3 | 2.8 | 8.3 | 2.8 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 2.8 | 8.3 | 8.3 |

| Outfit, Cooking, 20-Man | (e) | (e) | 1.7 | 4.2 | 1.7 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 1.7 | 5.0 | 4.2 |

| Shoe, Service | 10 | 25 | 8.3 | 14.2 | (e) | (e) | (e) | (e) | (e) | (e) |

a Various dates.

b On 15 Jun 44, the overall T/O factor gave way to separate factors for ETO and Pacific Areas.

c On 15 Dec 44, factors were separately shown for 6 theaters, only two of which are shown herein.

d Expressed in rates per 1,000 men (except Kit, 1942 and 1943, and Blanket, 1943).

e Not shown in Source.

Source: ASF, Rqmts Div, “Replacement Factors” (Control Symbol RME-8) eds. of 15 Dec 43, 15 Jun 44, and 15 Dec 44. Earlier data from files of Requirements Division, ASF.

required production of this item for 1945.40 Many developments in the fields of requirements determination, procurement practice, and modern technology all converged in the course of the war to affect the significance of the Army’s equipment replacement factors. By 1943, in addition to their use in the computation of replacement requirements as such, replacement factors had also come to be used in determining certain elements of “distribution.” The most important of these were various reserve or stock “levels” required to insure the availability of adequate supplies to troops at all times. Since these levels were expressed in

terms of months or days of supply, it was necessary to have dependable rates of wastage per month or day to determine the quantities of equipment needed to establish any particular reserve level. As indicated in a later section, replacement factors gradually supplanted distribution factors in this computation. By the end of 1944 the Army’s replacement factors served three official purposes:

(1) as fundamental bases in the computation of the over-all requirements for the Army Supply Program;

(2) as a unit of measure for the initial establishment of reserve levels in the zone of interior and theaters of operations;

(3) as a unit of measure in the supply of equipment and supplies to oversea theaters, bases, and commands.41

Spare Parts in Relation to Replacement—Of increasing importance as the war continued was the gradual shift from complete units of equipment to spare parts as the basis for estimating replacement demand.42 It was standard practice from the beginning of the defense period for the Army to procure spare parts in varying proportions along with finished items of equipment. Spare parts for many items constituted a substantial portion of total Army procurement both in physical and dollar terms.43 Some of the most complex and thorny problems in the administration of Army procurement and supply arose out of the spare parts program. The determination of requirements for spare parts was often more difficult than that for finished items. The distribution of parts in proper proportions to Army installations throughout the world posed virtually insoluble problems. The establishment of a far-flung empire of maintenance and repair facilities equipped with tools and machinery and staffed with trained mechanics required the investment of billions of dollars and the employment and training of hundreds of thousands of military and civilian personnel. The build-up of the Army’s repair facilities took a long period of time, thus forcing greater reliance, during the early stages of the war, upon complete replacement.

The Army’s spare parts program, as part of the larger program of repair and maintenance, arose out of military necessity as well as the desire to maintain combat-worthy forces at the least cost. Initial issues of complex items of equipment regularly included a complement of spare parts in order to permit emergency repairs under battle conditions, and additional quantities of parts were distributed to various repair echelons. In many instances the availability of spare parts was more important than complete replacement: the emergency repair in mid-ocean of an Army transport laden with troops and cargo was, for example, to be preferred to complete replacement. But in the year and a half after Pearl Harbor, in the general effort to attain high procurement objectives for complete end items, spare parts procurement was often subordinated. Parts originally earmarked for spare purposes were utilized in turning out additional quantities of end items. This practice, most notable in the case of aircraft procurement, became known as the “numbers racket” and was roundly criticized by the Richards Committee. As a result of the committee’s recommendations, the McNarney Directive of 1 January 1944

ordered both the AAF and the ASF to procure adequate spare parts even at the expense of reduction in the output of end items.44

The increased attention to repair and maintenance in the later stages of the war had the effect of reducing substantially the Army’s procurement requirements for complete replacement. Reclaimed equipment returned to stock after previous replacement had the effect of increasing total assets to meet gross requirements, thus avoiding additional procurement. Lower-echelon repairs to in-service equipment accomplished a similar end by lowering replacement factors and hence replacement requirements. The general falling off of replacement rates for complete equipment was accompanied by the increased significance of spare parts replacement, making necessary a much more refined instrument of inventory and supply control. Such an instrument was made available in the spring of 1944 in the form of the Supply Control System, with its elaborate records of issue experience and monthly analysis of the supply and demand position of all important procurement items.

The development of the Supply Control System had important effects on the Army’s methods of determining replacement requirements. After a study by the chiefs of the technical services in April 1944, planners concluded that accurate forecasts of requirements for numerous items could be made directly upon the basis of recent issue experience. Monthly redeterminations of replacement rates would be made and substituted for formal replacement factors whose revision tended to lag behind the realities of recent issue experience, with generally inflationary effects upon total requirements. Consequently in June of 1944 the number of items to which War Department (G-4 approved) replacement factors were assigned was reduced from 4,300 to around 600.45 At the same time concentrated attention to spare parts requirements led to a basic change in procurement policy. The practice for many items of equipment had been to order an estimated year’s supply of replacement parts concurrently with the complete item. This resulted in unbalanced inventories. To remedy the situation, detailed information on issues of individual parts was obtained from the Supply Control System and from special teams sent to the European and Mediterranean theaters. Beginning in November 1944, spare parts procurement was based on actual issue experience and excess stocks were returned to manufacturers for completion of end items still under production. Basic allowances of spare parts for major ASF items were prepared, and by the end of 1944 more than 3,500 spare parts catalogs, covering 90 percent of all major items, had been published.46

The broad effect of the developments just described was not abandonment of formal replacement factors but confinement of their application to important tactical items of concern to the General Staff. Decisions as to the methods of computing replacement requirements for the much larger number

of less important items were largely decentralized to the several technical services.47

Distribution Changing Concepts of Distribution—Initial-issue and replacement requirements, already discussed, would have been adequate for all the Army’s equipment needs only on the assumption that these requirements had been predicted with perfect accuracy, that procurement to meet the requirements had been completed exactly as needed, and that the finished items had been miraculously and instantaneously transferred in proper proportions from factories in the United States to individual using troops throughout the world. Needless to say, any war waged under such an assumption would be lost almost before it began. The exigencies of warfare, the impossibility of perfect prediction of requirements in complete detail with respect to types, quantities, and time and place of eventual use, and the technical and economic aspects of production, transportation, and distribution all required that the process of procurement and supply be conceived and executed primarily on a bulk basis well in advance of actual need. These considerations made necessary the inclusion in Army requirements of the important element of distribution.

For World War II “distribution” referred to the additional quantities of matériel, over and above initial issue and replacement, required to “fill the pipelines” in the Army’s world-wide system of supply. The basic purpose of allowances for distribution was to insure, without fail, the timely delivery of supplies from point of acceptance from the procurement source to the point of ultimate issue. Often likened to their counterpart in a municipal water supply system, distributional requirements were theoretically large while the pipelines and reservoirs were being filled and extended, negligible when only minor leakages occurred after the system was filled, and negative when supply lines were curtailed or withdrawn. But the crude analogy was merely suggestive, since the military supply system comprehended many tens of thousands of different items instead of a single homogeneous commodity and involved numerous and constantly changing sources of supply, ultimate destinations, and techniques as well as channels of distribution. The Army’s distribution system for World War II included not only matériel in transit via every available type of transportation throughout the world, but multitudinous inventories of equipment and supplies in post, camps, stations, warehouses, depots, and ports of embarkation in the United States and corresponding ports of debarkation, base depots, intermediate depots, advance depots, and ultimate supply dumps in forward areas.

In principle, the Army’s distribution requirements as defined from time to time consisted of four elements:

1. stocks of matériel at various points of distribution;

2. matériel in transit;

3. distributional losses (ship sinkings and other in-transit losses); and

4. tariff of sizes for appropriate items.

Actually, there was considerable confusion throughout the war surrounding the entire concept of distribution. This confusion was reflected in numerous changes in the methods of computing distribution requirements, in the adoption of constantly changing and often inconsistent terminology, and in the

unintelligible accounts which have subsequently appeared in connection with the entire subject.48

At the beginning of the World War II procurement program, little or no attempt was made to evaluate separately the several elements comprising distribution. In computing total distribution requirements for an item, a blanket distribution “factor” or percentage figure was applied to the sum of initial-issue and replacement needs. This factor varied from one technical service to another and frequently within a particular service for different classes or items of equipment. For the Corps of Engineers the distribution factor prior to Pearl Harbor was 10 percent for all items of equipment. For the Quartermaster Corps it was 25 percent for all nonsized items and 27 to 50 percent for most items subject to size tariffs. Distribution factors ranging all the way from 5 to 90 percent were used in computations of the Army Supply Program until mid-1943.49

Two basic assumptions underlay the use of distribution factors. The first was that distributional requirements were directly proportional to the total quantity of supplies needed to equip and maintain forces in the field. Therefore the application of a given percentage factor to the sum of initial issue and replacement was considered to yield the best available measure of distributional needs.50 Distribution factors were, of course, subject to revision from time to time on the basis of experience; until the 1 August 1943 edition of the Army Supply Program which discontinued the use of distribution factors, directives for the recomputation of the program prescribed the use of “the latest approved distribution factors.”

The second basic assumption was that after the distributional “pipelines” and “reservoirs” had once been “filled” no further quantities for distribution would be needed, except for specific types of leakage and loss which could thereafter be directly computed and provided for. Distribution was thus conceived primarily as a nonrecurring demand, under which maximum distribution allowances would remain “frozen” in supply pipelines until supply lines were eventually curtailed.51 Accordingly, for any given period the distribution factor would be applied only to increments of total initial-

issue and replacement requirements over the maximum for the previous period. This was accomplished without difficulty in the case of initial issue, which was by nature an incremental quantity for each period. But in applying the factor to replacement, which consisted largely of recurring needs from year to year, it was necessary in principle to isolate and use only increments to previous replacement maxima. In view of all the practical difficulties involved, no such accurate division of replacement requirements was made. For requirements through 1942, the distribution factor was apparently applied by the several technical services in accordance with their own interpretation of policy. But in the summer of 1942, and again at the beginning of 1943, the ASF Requirements Division directed that the distribution factor be applied only to initial issue and then only for requirements prior to 1944. Although this approach did not fully accord with the theory underlying the use of distribution factors, the limitation in question was prescribed at a time when every effort was being made to curtail requirements and with the assumption that various buffer elements in the total estimates would provide adequate reserves.52

By the fall of 1942, the use of the simple factor method for computing distribution requirements had been seriously challenged by the Quartermaster Corps. Requirements personnel in the Office of the Quartermaster General (OQMG) as early as July 1942 had pointed out that blanket distribution factors were both crude and inelastic. Instead of basing distribution requirements upon the specific elements entering into the distribution process, the factor method arbitrarily assumed that distribution bore a fixed or given ratio to total issue requirements (initial issue plus replacement). This assumption ignored completely the fact that even if total issue requirements remained fixed, distributional needs would vary widely with the expansion and contraction of supply lines throughout the world. OQMG personnel in 1942 feared that with supply lines steadily lengthening the existing distribution factors might prove to be grossly inadequate.53

The alternative proposed in the Quartermaster Corps was the so-called “carry-over method”, which focused attention upon the principal element of distribution, that is, stocks (often referred to as reserves). The carry-over method contemplated the establishment of sufficient stocks, both in theaters of operations and in the zone of interior, to carry operating forces at all times until any probable interruptions in the supply function could be overcome. The quantitative carry-over of supplies to be held at various points of distribution would be prescribed in terms of stock or reserve levels, expressed as the number of months or days of supply deemed adequate by higher authority to meet the contingencies in question. A day of supply was defined as one thirtieth of one month of supply; one month of supply was determined by applying current monthly replacement factors to total initial issue for the forces concerned. With stock levels thus defined in terms of operational needs, separate computations could be made for “in-transit” requirements, sinking losses, and size tariffs. Total distribution requirements

would then be functionally determined and would automatically possess the desired degree of flexibility.

The foregoing summary of the carry-over method is at once oversimplified and more inclusive than the original Quartermaster proposal. Many of the details and corollaries of the plan emerged only after repeated conferences and discussions. The ASF Requirements Division did not approve the plan at the time of its presentation; the entire process of requirements determination was in a state of flux and all of its elements required re-examination and clarification. Moreover, the Quartermaster proposals were accompanied by specific recommendations for stock levels which would have raised requirements at the very time when the Feasibility Dispute and other pressures were compelling reductions. But the basic merit of the plan was recognized, and its adoption by the Quartermaster Corps for the 1 February 1943 edition of ASP was approved. By the time of the 1 August 1943 recomputation, the plan had been adopted by the War Department for all technical services, and directives governing the computation of distribution requirements were amended accordingly.54

Stocks—The revised procedure for determining total distribution requirements called for careful attention to each of the elements of distribution. As the most important element, stocks (reserves) received the greatest attention and gave rise to the most difficult policy decisions and problems of control.55 Stocks fell into a number of classes, including theater stocks, stocks reserved for theater needs at ports and filler depots in the United States, stocks at major distribution depots in the United States for zone of interior needs, and post, camp, and station stocks. Theater stock levels were prescribed by the General Staff and consisted of two components—a minimum level and an operating level. The minimum level was, so far as possible, to be maintained at all times to meet emergencies; the operating level represented working stocks over and above the minimum. Theater levels were determined in accordance with distance from the procurement source and other conditions.

The 1 August 1943 Army Supply Program was designed to provide procurement adequate to establish and maintain minimum levels averaging 75 days of supply for all theaters, and operating levels of 45 days (operating stocks were considered to fluctuate in size from 0 to 90 days of supply, depending upon fluctuations in issues and arrivals

of matériel in transit). Total theater levels thus averaged 4 months of supply as measured by current replacement factors. At the same time theater of operations reserves to be maintained at ports and filler depots in the United States ranged from 50 days of supply for Ordnance up to 120 days for the Quartermaster Corps. Stock levels for troop requirements in the ZI consisted of 60 days of supply in distributing depots, plus an average of 60 days of supply at posts, camps, and station.56

The change-over from the use of blanket distribution factors to the expression of distribution requirements in terms of days or months of supply tended in practice to break down the distinction between distribution and replacement. Not only stock levels but in-transit and sinking-loss requirements were now expressed in terms of days or months of supply. Since replacement requirements were also expressed in terms of a number of months’ supply applied to the entire terminal force in the troop basis for a given calendar year, it became standard procedure in the ASP to add the total number of days of supply required for distribution (likewise applicable to end-of-period strength figures) to the total for replacement and to lump the whole under the general heading of replacement (maintenance) requirements. Not only did this tend to confuse the record; policy makers at the time also apparently suffered considerable confusion over the distinction between replacement and distribution. Thus in the 1 February 1943 computation of ASP requirements, while the change-over to the new methodology was in transition, the technical services were ordered to continue the use of blanket distribution factors while at the same time making provision, under the heading of “maintenance,” for 4½ months’ theater stock levels for average overseas forces.57 Although this double provision for distribution requirements was formally rectified by the abandonment of the use of distribution factors in the 1 August 1943 edition of ASP, the production requirements for 1943 were at this time frozen on the 1 February 1943 basis.58

Stock levels, regardless of type or location, were redetermined from time to time in accordance with the procurement as well as the strategic situation. The entire question of the state of Army stock levels was raised by the War Department Procurement Review Board in 1943 and shortly thereafter was carefully investigated by the Special Committee for the Re-study of Reserves (Richards Committee). The numerous findings and recommendations of the Richards Committee for the most part remain outside the scope of the present study. In general, prescribed levels as well as actual stocks both overseas and in the zone of interior were found to be too high. Substantial reductions and changes in procedures were ordered by the McNarney Directive of 1 January 1944.59

The actual procedures for computing procurement requirements needed to establish and maintain the prescribed stock levels were of labyrinthine complexity. For each edition of the Army Supply Program the governing directive laid down the broad stock-level objectives and the general estimating procedures to be followed. The great burden of obtaining the necessary detailed information and translating this information into requirements data in a form suitable for manipulation by automatic tabulating machinery fell to the technical services, working under the close supervision of the Requirements Division, ASF. A detailed understanding of the complexity of the problems surrounding this one element of distribution would provide for anyone a healthy insight into the magnitude of the task of determining Army requirements as a whole.60

In-Transit Allowances—Requirements to meet the elements of “in-transit distribution” were not separately calculated so long as the factor method of computing distribution requirements was used; the blanket factor was deemed adequate to cover all elements of distribution. With the adoption of the carry-over principle and the abolition of blanket distribution factors, it became necessary to compute separately the increments in each calendar year to the total quantity of matériel “frozen” in transit. This was accomplished by applying a complex formula which underwent change from time to time until no further additions to in-transit pipeline quantities were authorized. The procedure as revised in July 1943 called for the use of two weighted “in-transit times”—one for the zone of interior and one for theaters of operations collectively—as officially determined by the director of the Requirements Division, ASF, in consultation with the chief of the Transportation Corps and other technical service chiefs. In-transit time was the average period required in months or days for all types of equipment to be physically moved from points of acceptance at the procurement source to the zone of interior point of issue or the theater of operations port of debarkation. These two weighted periods were then applied to increments of initial and replacement issues destined respectively for the zone of interior and the theater of operations in the calendar year in question. In the 1 August 1943 ASP, which allowed an average of 45 days in-transit time to all theaters, theater of operations in-transit requirements for the year 1944 were defined as 45 days of supply to maintain the additional 3,186,000 troops to be sent overseas in that year; for the year 1945, the figure was 45 days of supply for 1,750,000 additional troops. At the same time, the approved zone of interior in-transit allowance was 15 days of supply at the lower ZI replacement rates and was applied to ZI troop requirements for the years in question.61 By the end of 1943, transportation pipelines had generally been filled, and in accordance with the recommendations of the Richards Committee in-transit requirements were thereafter eliminated. This

change took effect with the 1 February 1944 edition of the Army Supply Program.62

Sinking Losses—The early editions of ASP made no specific provision for requirements to compensate for sinking losses, although actual losses were deducted from estimated quantities “on hand” in each revision of ASP. In the two 1943 editions of ASP a separate allowance equal to 2 percent of all theater of operations replacement requirements was included to cover sinking losses. This allowance conformed closely to rates of loss actually experienced. From 1 January 1942 to 1 October 1943, U.S. Army cargoes lost at sea totaled 1.74 percent of all cargoes shipped. After the peak loss of 6.72 percent for March 1943, sinking losses declined rapidly and amounted to only 0.39 percent for the six-month period, April through September 1943.63 At the end of 1943, the Richards Committee, noting that the submarine menace had been fairly well overcome and that loss rates had fallen to less than a half of 1 percent, recommended the elimination of the sinking loss factor as a procurement requirement. This was approved in the McNarney Directive.64

Size Tariffs—The problems associated with “tariffs of sizes” were of particular importance in computing Quartermaster requirements, although other services were faced with size problems.65 During World War I the failure to predict the composition of total Army personnel by size groupings led to grave shortages in particular sizes of shoes and clothing. The nature of the problem is illustrated in the following statement of Senator James Wolcott Wadsworth, Jr., during the World War I Senate investigation of the War Department:

For instance, at Camp Custer it became necessary, in order that a detail of one regiment of infantry could go to target practice, to march half of the detail to the target range, as I understand it, with the available shoes that could be gotten together; that they then had to march back, change those shoes, and put them on the other half of the detail in order to send that half of the detail to the range, such was the scarcity of shoes that the men could wear, while at the same time thousands of pairs of shoes were there which no one could wear.66

In order to determine total requirements of shoes, it was not enough for the Quartermaster Corps to know in advance the total number of troops to be activated, the exact initial allowance of shoes per man, and normal replacement and distribution requirements. Provision also had to be made for wide differences in individual size requirements, and these could not be perfectly predicted.