Chapter 8: The Battle of Bardia

During the 2nd January General Mackay visited each of the six attacking battalions. Outwardly he was the most calm among the leaders, yet it was probably only he and the other soldiers in the division who had taken part in set-piece attacks in France in the previous war who realised to the full the mishaps that could befall a night attack on a narrow front unless it was carried out with clock-like precision and unfailing dash. The younger leaders were excited, but determined that in their first battle they should not fail. To one of them it was like “the feeling before an exam”. Afterwards their letters and comments revealed how sharply conscious many of them were that this was the test of their equality with “the old AIF” in which their fathers had served, and which, for them, was the sole founder of Australian military tradition.

“Tonight is the night,” wrote the diarist of the 16th Brigade. “By this time tomorrow (1700 hrs) the fate of Bardia should be sealed. Everyone is happy, expectant, eager. Old timers say the spirit is the same as in the last war. Each truck-load was singing as we drove to the assembly point in the moonlight. All ranks carried a rum issue against the bleak morning ... At 1930 hrs we passed the ‘I’ tanks, against the sky-line like a fleet of battle-cruisers, pennants flying ... Infantry moving up all night, rugged, jesting, moon-etched against the darker background of no-man’s land ... The BM and party taped the start-line – historic ... for it is the start-line of the Australian soldier in this war.”

It will be recalled that Major Campbell, by patrolling forward to a point in the ditch about midway between Posts 45 and 47, quietly pacing 1,000 yards back at right angles to the Italian front and marking bushes there by tying rifle-cleaning rags on to them, had made an accurate landmark in the almost featureless desert. On the night of the 1st his Intelligence officer (Lieutenant Ferguson1) had laid 5,000 yards of signal wire to mark the route to this landmark.

Meanwhile the assault battalions had been moving into position at the western end of the narrow corridor along which they would march to the attack. The 2/1st arrived at the “assembly area” at 1.30 a.m. and part slept there on the ground until roused at 2.30; others remained awake watching their bombers attacking Bardia, and the tracer shells climbing into the sky. The men were heavily laden; each wore his woollen uniform with a sleeveless leather jerkin over or under the tunic, and most had also a greatcoat with the skirts turned back to allow freedom of movement. They wore steel helmets and had respirators hanging on their chests; some carried sandbags wrapped round their legs; and, in pouches, pockets and haversack, 150 rounds of ammunition, one or two grenades and three

days’ rations of tinned beef and biscuits. They set out carrying picks and shovels but the combined load was too heavy and most of the tools were abandoned. On his back each man wore a patch of white cloth so that the following troops would recognise their own men – a device first used by Australians at Lone Pine in August 1915. It would be so cold waiting through the night that most had put on (or left on, because few had fully undressed for a week or more) woollen underclothes and sweaters, and some wore scarves and balaclavas. Some doubted whether, with such a weight of clothing and perhaps seventy pounds of gear, they could raise their weapons and fire and, waiting at the assembly area, they practised the motions.

At 2.30 a.m. the men ate a meal and drank their rum2 and at 4.16 the leading companies began to move forward to the start-line in silence except for the swish of feet in the dry soil and low camel-bush. Lieut-Colonel Eather3 led the 2/1st Battalion with Captain Moriarty’s company on the right and Captain Dillon’s4 on the left, each with two of its platoons forward and one back, the two companies extending 300 yards from flank to flank. It was pitch dark. A few minutes after the leaders had arrived at the start-line and while the rear platoons were still moving forward, the barrage opened (at 5.30 a.m.) with a sudden sustained hammering of guns which lit up the horizon with a line of flashes and streaks of light. The sudden noise, the flash of guns, the sound of shells going overhead and crashing in the darkness had an exhilarating effect, dispelled the tension and produced excitement and confidence. Men began calling, singing, and shouting defiance at the enemy, the guns drowning their voices.

The leading platoons now advanced slowly from the taped line and with them six parties of engineers and pioneers, each party carrying bangalore torpedoes – pipes twelve feet in length loaded with ammonal – with which they were to blow gaps in the Italian wire. As they advanced Italian shells began to fall in the area, but mostly behind the leading troops. A shell burst among a leading platoon and a bangalore exploded, killing four men and wounding nine. Nearby a splinter cut through the steel helmet of Lieutenant Dawson,5 one of whose tasks was to give the signal for blowing the gaps in the wire, and who commanded the bangalore parties. It cut his head and left him lying stunned on the ground. About 100 yards short

of the Italian anti-tank ditch the line was halted and, after a short pause, while officers checked the positions of their men and waited for their own artillery fire to lift, seven parties each of three engineers (who did not know of the wounding of Dawson) moved forward. Spaced at sixty-yard intervals, they clambered through and beyond the ditch and each party slid two torpedoes underneath the wire, using the second to push the first beyond the far side of the twenty-foot wide fence. The torpedoes had two-foot fuses, and a few minutes before the time to light them – 6 a.m. – Lieutenant Davey6 of the engineers, who was on the spot to examine a possible minefield near Posts 45 and 47, became anxious about Dawson and began groping his way from one party to another in search of him. Moving cautiously along the ditch, pistol in hand, he was challenged by Johnston,7 Dawson’s platoon sergeant, who also had his pistol ready. Johnston, too, had failed to find Dawson, and Dawson had the Very pistol with which to fire the signal to light the fuses. Davey ordered Johnston to give the signal by blowing his whistle. Johnston blew but the din drowned the noise. Meanwhile Eather, who had become anxious, sought out one of the engineer parties and, learning that the signal had not been given, ordered that a torpedo be blown. The other teams followed this example.

When the infantrymen heard the torpedoes explode they rose to their feet and scrambled forward into the ditch whose sides the engineers were already breaking down with picks and shovels.8 There Eather stood directing the platoons forward with his walking stick. Once through the wire Dillon’s two leading platoons charged forward, Lieutenant Kennedy’s9 at Post 47, Lieutenant MacPherson’s at 46, while his third platoon (Captain Travers10) gave supporting fire, with the Italian shells falling behind them. MacPherson detected what appeared to be an additional post just ahead of him with uncut wire in front of it. Instead of leading to the right through the gap in the wire, he took his men directly at the new post. In a few seconds they had cut the wire and were on top of the new position, which was discovered to be a kind of listening post manned by about twenty Italians who surrendered without inflicting a casualty. MacPherson’s men hurried on towards Post 46, which was still silent, the Italians evidently being dazed by the artillery fire. Kennedy’s platoon which had taken the surrender of six or seven Italians in a listening post between Posts 45 and 47, attacked 47, the Bren gunners firing from the hip. They cut the wire and had overcome the post before the enemy had time to fire more than a few ineffective bursts from one machine-gun.

About forty-five prisoners were taken. Kennedy advanced and took Post 49, with about forty prisoners.

In less than half an hour and while it was still dark MacPherson, who, though wounded, continued to lead his platoon, had taken 46 and 48. About this time a heavy and accurate Italian barrage began to fall along the broken wire, raising a haze of dust. Dillon sent Travers and his platoon forward to take an artillery position enclosed in a sangar close behind the concrete posts, which they did. Meanwhile Moriarty’s company had taken Posts 45 and 44; the Italian line was breached.

The two remaining companies of the 2/1st were next through the gaps in the wire. In extended order, five or six yards between each man, they advanced up the slope behind the Italian posts. After a few hundred yards they came under fire from positions ahead of them, but they plodded on, firing from the hip at a long low stone wall from which heavy but inaccurate fire was coming. The men were spread across 600 yards and, in the dim light, offered a poor target. The Italians behind the wall fought until the leading Australians were inside it throwing grenades and lunging with the bayonet. When the mêlée was over, 400 prisoners were assembled and sent back.

Meanwhile the engineers had broken down the sides of the ditch on each side of Post 47 and made six crossings for the tanks and trucks at 60 to 100 yard intervals, and had discovered mines between the crossings and the wire. In five minutes two crossings were ready, and at 6.35 a.m. in the half-light the 7th Royal Tanks (with twenty-three tanks) and the 2/2nd moved towards the gap. As the infantrymen marched forward they sang and smoked.11

After passing through the gaps in the wire about 7 a.m. the columns swung right with tanks leading. Captain Caldwell’s12 company followed one troop of three tanks along the inside of the wire against the two lines of Italian posts, Captain Godbold’s13 with another troop of tanks marched against the battery positions farther in. In the first few posts the Italians fought it out, their tracer shells striking the heavy armour of the tanks and ricocheting high into the air. Some garrisons surrendered after the tanks, blazing with 2-pounders and machine-guns, had circled them, but generally there was a sharp little battle, sometimes for a quarter of an hour. Two or three of the cumbrous tanks would concentrate their fire on one post while a platoon fired with rifle and Bren from close behind. When the

Italian fire seemed to have been subdued the infantrymen moved forward, sometimes cautiously, sometimes with a rush, and threw grenades into the concrete-sided gun-pits and down the entrances to the underground shelters. The inner and outer line of posts were about 400 yards apart and consequently the leading platoons were widely extended. In the dust and smoke the men were at times leading the tanks, at times well behind them. Precise control was often impossible. One post would be taken by a concerted attack and according to the book; and another single-handed by some impetuous man who worked forward alone and bombed a post into surrender. One section, having moved forward cautiously, threw a grenade into a post. An Australian voice from below shouted: “For God’s sake don’t do that; I’m here.” It was Sergeant Skerrett,14 an intrepid young leader, who had seized the place unaided. Between Posts 38 and 39 the leading men were fired on by four field guns at a range of a few hundred yards. Covered by the fire of two riflemen, Caldwell and Signalman Webb15 advanced on Post 38, which surrendered.

Because his two leading companies were so far apart Lieut-Colonel Chilton16 ordered Captain Hendry’s17 to fill the gap, where it soon came under direct fire from the Italian batteries and began to lose men, but pressed on without tanks, the sections widely dispersed. It was a wise decision by this resolute and always-thoughtful young leader, because the guns commanded the gap in the enemy’s defences and might have caused grave losses among the troops following the leading battalions. Hendry and his men carried out their orders doggedly, undeterred by mounting casualties inflicted by Italian gunners who fought until the infantry were within 100 yards or less and sometimes until crews lay dead round the battery positions. As Hendry neared the objective the main part of his company, reduced by casualties and because sections had been placed out on the flanks, numbered only twenty men. Two of his platoon commanders had been killed and the third wounded. The remnant now came under fire from eight field guns, some 500 yards beyond the road. About the same time Godbold’s company, moving parallel to Hendry’s and also spread over a wide front, came under artillery fire from the same area. After an exchange of fire the commander of the tank troop regretfully informed Godbold that his petrol and ammunition were exhausted and he must return to the tanks’ rallying point. Godbold halted his line for three-quarters of an hour, then decided to advance without waiting for the tanks’ return. His Bren gunners silenced a battery firing on them from a position near the Iponticelli junction and they reached the objective there.

“I have a vivid recollection,” wrote an infantry sergeant later, “of seeing ourselves as the enemy might have seen us. Just at sunset on the 3rd one

of the Northumberland Fusiliers – a section was with us – called: ‘Christ! look at this!’ I looked around to see, almost silhouetted against the setting sun, a whole plain full of advancing infantry. The half-light, the mass of equipment and the flapping greatcoat of every man, made them look really huge, while the perfect formation and dispersal, the steady advance, gave the impression of great numbers and of inevitability. It was merely one company of the 2/2nd Battalion, moving up towards us, but it was enough to impress even a man from the Northumberland, and it is possible that other sights such as this had, earlier, made an even greater impression on the Italians.”

The gap in the line of Italian posts now extended from the Bardia–Capuzzo road on the right to the southern edge of the Wadi Gerfan on the left, and, in addition to the crossings over the ditch and the gaps in the wire at Post 47, a second series had been made by the engineers at Posts 38 and 39. Here Lieutenant Cantelo18 had cut wire and disarmed mines while the posts were still untaken. Cantelo and three sappers were wounded but, as he lay, he continued to direct Sergeant Crawford19 and the section and, after resting awhile, led them on to Posts 35 and 31, where other crossings were made. Finally this party opened the Bardia road by removing a road-block.20

Meanwhile, the right company of the 2/1st and the whole of the 2/3rd had thrust eastward into the fortress area. On the 2/1st’s front Sergeant McIntosh,21 a rugged, taciturn Scot – a British soldier of 1914–18 – took one of Hodge’s22 platoons forward at about 10.30 a.m. to attack a battery that could be seen on the edge of the Gerfan escarpment, 400 yards away. Hidden by the dust raised by shells and movement, McIntosh was thirty yards from the Italian positions – a scattered group of guns each protected by a rough stone wall about four feet in height – before the Italians saw him. They began to fire, but McIntosh led his twenty-four men fast, shooting as they went, took the nearest gun position, and thence fired on the others. After an exchange of fire the Australians jumped from the sangar and charged towards the remaining guns. The Italians began waving white flags. McIntosh found in the area three field guns, an anti-tank gun and twelve machine-guns, and assembled 104 prisoners, not including some fifty who were lying dead or wounded. While he was reorganising his sections an Italian medical officer arrived and they agreed that both Australian and Italian wounded should be carried by Italian bearers to an Italian dressing station nearby. The unwounded prisoners streamed back towards the perimeter with one Australian as escort.

The left company, now commanded by Captain Travers, was advancing north along the double line of posts. As it approached Post 51 it came under fire from a battery about 700 yards north-east of the post, whose garrison, evidently heartened by this support, maintained brisk machine-gun fire, and was held for about ten minutes. The situation was saved by the arrival of an infantry tank of the troop allotted to this battalion which lumbered towards the battery and silenced it. The infantrymen occupied the battery positions overlooking Posts 51 and 53. It was then about 7.15 a.m. and the leading companies of the 2/1st were along a front of about 1,500 yards on top of the escarpment leading down to the Wadi Gerfan, their left under fire from Posts 53 and 55; the garrison of Post 51 was inactive.

By the time the 2/3rd Battalion had moved through the gap in the Italian line at 7.50 a.m. the dust was so dense that some platoon commanders could not see the platoons on each side of them, and steered by compass. Already prisoners from left and right were streaming through the gap. Beyond the Italian posts the three leading companies of the 2/3rd fanned out and advanced along the flat to the edge of the Gerfan escarpment on the right of the 2/1st. Into the dust and machine-gun fire the thin line strode as fast as their burden of heavy clothing, weapons, ammunition and rations would allow, marching at ease with rifles slung on their shoulders. After a few hundred yards the right company (Major Abbot’s23) met fire from a group of sangars 200 yards away. A platoon went to ground, and opened fire with their Bren guns until they could see the bullets chipping the tops of the stones, and the Italians beginning to wave white cloths; then they advanced and hustled the prisoners to the rear.

Near the objective the company encountered a larger sangar. Lieutenant Murchison24 ordered his men to charge and himself sprinted forward, a revolver in each hand. A bullet hit one revolver but he ran on wringing one hand and brandishing a revolver in the other. As he neared the wall, he and those nearest him threw grenades, leaped on to the wall and into the sangar. The dust began to rise from a scrimmage in which some of the attackers used bayonets until the Italians had all surrendered. Thence the platoons advanced into the source of the Wadi Ghereidia until some hundreds of Italians had surrendered and been ordered “Avanti” – in this case to the Australian rear – and generally without a guard. McGregor’s25 company, next to the left, had taken 300 prisoners and lost only one man killed in crossing the flat. Moving into Ghereidia they found themselves in what was evidently a headquarters, housed in dozens of caves dug into the banks. Sergeant Smith26 fired a shot through the ground sheet that covered one of these, and from it and other dugouts issued dozens of Italians waving white cloths.

Farther left Captain Hutchison’s27 company had no casualties until in sight of an oval sangar 250 yards long with a wall four to six feet high, near the edge of the escarpment. Machine-guns fired from its bays and a look-out tower rose in the centre. As Hutchison arrived this fort was being fired on from the left by Captain Hodge’s company of the 2/1st, and the Italians surrendered before Hutchison’s men reached it. Beyond it, now in new territory, they encountered really heavy fire from another large sangar 200 yards ahead. Hutchison ordered one platoon to fire while the other two charged. They fired as they advanced. Private Blundell,28 very young and excited, ran as fast as he could, jumped on the wall and stood thrusting with his bayonet at an Italian machine-gun team. Another Australian close behind kicked the heads below with his heavy boots. Hutchison himself and Sergeant Owers29 quickly turned one machine-gun about and fired it at the Italians. They noticed that it was sighted at 1,000 metres, the Italians in their alarm having omitted to lower the range; other machine-guns were sighted at 800 metres. In a few minutes the garrison had all surrendered – about 560 men with many machine-guns of various types, two light guns and two small tanks which had been dug into the ground. Four men escorted the prisoners to the perimeter. By 9.20 a.m. all companies of this battalion were on their objectives and a little later were in touch with the 2/1st on the left and with Major Onslow’s30 thin line of machine-gun carriers extending along the high ground between the 2/3rd and 2/2nd.

These cavalrymen had gone into action with the 2/3rd, then wheeled to the right. Often hidden in dust stirred up by shell bursts and by the churning of their own tracks, they had advanced to where the road crosses the source of Wadi Ghereidia. There they were shelled from about a mile ahead, and took cover behind the embankment. One carrier had been hit in the advance, and another was now hit near the road, where for half an hour any movement brought down concentrated artillery fire. The cavalrymen blazed back with Bren guns and anti-tank rifles and, with the help of tanks, succeeded in silencing one Italian battery.

Then followed an episode in which, along the thinly-held line of the 2/3rd Battalion in the centre, so many small groups were involved in such rapid succession that it is difficult to establish the precise sequence of events.

Hutchison had placed a platoon in the captured sangar and the other two forward of it to right and left on a peninsula that juts out into the Wadi Gerfan. With him was Lieutenant Gerard’s31 platoon of the 2/1st.

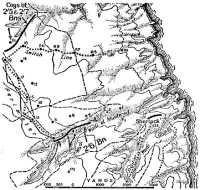

Position of leading companies, dusk 3rd January

Hutchison was visiting his left forward platoon when he saw six tanks approaching. He noticed they were khaki not grey like the British tanks he had seen; but, assuming they were British, he shouted: “I’ll be there in a minute.” There was a burst of fire from the tanks which were now only thirty yards away. Hutchison’s runner, Private Peter Tambakis,32 fell mortally wounded, and a solid shell knocked Hutchison’s rifle out of his hand. Private Hergenhan33 ran forward to bomb one tank but the grenade caught in his jerkin and killed him. The tanks began to circle the sangar, firing at every sign of movement. Lieutenant Fulton34 who had not realised what was happening was walking to the tanks, which he too believed to be British, when he realised his mistake. He ran forward, leaped on the tank, fired his pistol down the open turret and sprinted back into the sangar, hurdling the wall.

The tanks then moved south into the area of McGregor’s company which was still holding a dense crowd of about 500 prisoners. These were being guarded by six men, and the company was dispersed over a wide area. The infantrymen guarding the prisoners had no weapons that could disable these tanks and took cover. The tanks moved among the prisoners and captured the guards, one of whom was sent to McGregor’s headquarters 250 yards away to announce that all must surrender. The messenger met Le Nevez,35 the company sergeant-major, who told him to forget his message. Le Nevez and Sergeant W. R. H. Smith, who was with him, fired on the tanks with a Bren gun, and they lumbered away. Le Nevez then fired a few bursts into the clustered Italians, who re-surrendered. Meanwhile Lieut-Colonel England,36 moving along his forward positions in a carrier, had met Warrant-Officer MacDougal37 of Hutchison’s company who, seeing the tanks between him and the others, had taken his men to the right, putting a steep-sided little wadi between them and the tanks.

MacDougal told England what he had seen and that the tanks were moving south. England realised that this would take them through this thin line and to his headquarters which were established in a tributary of Gerfan not far away. Consequently he hastened back towards his headquarters. On his way he warned Sergeant Long38 who hurried to two infantry tanks which were resting out of sight over the rise beyond the wadi, but the crews, either sceptical, or relaxed after the excitement of

the long morning in action, did not respond.39 Meanwhile England had reached his headquarters and ordered the few men there to form a line behind a low stone wall across the wadi. Soon the tanks appeared in the wadi travelling towards the wall, firing as they moved. Lieutenant Calman40 and Corporal Wyatt41 carried an anti-tank rifle along the bank of the wadi, and began firing on the tanks, but soon Calman was killed by their fire and the tanks advanced again. They were only forty yards from the riflemen lining the stone wall when into the wadi fifty yards behind the infantry drove the three trucks on which were mounted the 2-pounder guns of the anti-tank platoon attached to this battalion. A runner had warned Lieutenant Jay42 of this platoon that Italian tanks were advancing. Corporal Pickett’s43 gun, the first to be ready for action, hit and silenced four of the tanks in quick succession. The gunner of the fifth then hit Pickett’s portee (the truck carrying the gun) killing one man44 and wounding Pickett, but the survivors got their gun into action and knocked out the tank. The sixth tank now hit Pickett’s portee, this time setting it on fire and fatally wounding one of the team,45 but this tank too was soon hit. None of the Italians survived the fire of the 2-pounder guns whose solid shells drove easily through their armour, but lacking enough momentum to pierce the opposite side ricocheted inside the cabin doing ghastly damage.

It was now half an hour after midday. By this time an apparently endless column of Italian prisoners was streaming back through the gaps in the perimeter; the officers in ornate uniforms with batmen beside them carrying their suitcases; the men generally dejected and untidy, strangely small beside their captors. When the 2/5th Battalion, marching into the perimeter, saw this column moving towards them, their first thought was that the 16th Brigade was being driven back – then came the realisation that the close-packed column, winding like a serpent over the flat country, was a sample of a defeated Italian army. Few guards now marched beside the prisoners – the battalions had found that to send even two or three men with as many hundred prisoners soon robbed them of more riflemen

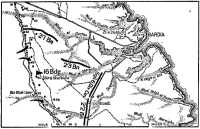

The 16th Brigade dispositions, midday 3rd January

than they could spare.46 Already the forward battalions were learning that the numerical strength of the garrison had been greatly under-estimated. In the course of the morning an Italian medical officer told one of Allen’s staff that there were 40,000 Italians in Bardia, not 25,000 as the Intelligence officers of XIII Corps and 6th Division had decided.47

The 2/5th Battalion, now advancing into the fortress area against this tide of Italian prisoners, had begun its move to the start-line at 12.30 p.m. on the previous day, when it began to shuttle forward in its own first-line transport assisted by some lent by the 2/7th and the Northumberland Fusiliers – but not enough to lift the whole battalion at once. It had to assemble at a rendezvous about three miles south of the corridor along which the 16th Brigade was to enter the perimeter. The track had been crowded with other trucks and with guns, and the fifteen mile journey took nine hours. After a conference at which final instructions were given to his officers, the commanding officer, Major Wrigley,48 returned to Savige’s headquarters to report that his battalion was at the rendezvous and to receive final instructions. During his absence the senior officer with

the battalion, Major Sell,49 received instructions to move the unit about two miles and a half north to a final rendezvous for the night. When Wrigley returned at midnight he found that one half of the battalion had become separated from the other in the darkness. With his Intelligence officer, Lieutenant Shave,50 he found the missing companies. Thence, after little more than two hours of rest the battalion moved to the assembly area where they were due not before 6 a.m. on the 3rd, after the 2/3rd Battalion had vacated it. Skilfully guided by Shave they marched through the second gateway into the defended area, near Post 39, and thence, in box formation and undeterred by the severe artillery fire, to near Post 36, where, still under fire aimed at the gap, they took shelter while awaiting their zero hour-11.30. Meanwhile Green’s51 company of the 2/7th, which was to come under Wrigley’s command and form the right flank of his attack, also had entered the fortress area by still more southerly crossings near Post 35. All companies were under fire from the guns just east of the Bardia road which, it will be recalled, had been shelling the 2/2nd Battalion.

At this stage the 2/5th, whose men were already wearied by an almost sleepless night and two long marches, suffered a series of mishaps. Wrigley was wounded by shell fire at 10.20 and Sell took command. The commander of the supporting troop of tanks arrived twenty-five minutes after Wrigley had been wounded, and reported to Sell that he would have to go back for fuel and ammunition and could not return in time to join the battalion at 11.30. Sell immediately decided to go in without them.

The final plan for this phase of the attack provided that Captain Green’s company of the 2/7th, leading on the right, with Major Starr’s52 company of the 2/5th advancing on his left rear, would capture Posts 27 to 10; Captain Smith’s53 company of the 2/5th with Captain Griffiths’54 company of the same battalion echeloned to its right rear would advance with tanks to “The Triangle” where Smith would remain while the tanks picked up Griffiths and led him along the Switch Line.

When Smith’s company moved out of the wadi on to the bare ground on the eastern side, it immediately met heavy and accurate fire from field guns and machine-guns in a semi-circle of enemy positions about 700 yards to the north-east. The infantrymen could see twelve guns blazing at them over open sights. Lieutenant McNally’s55 platoon on the right advanced some distance through this fire, then went to ground and, crawling forward, eventually came into touch with some men of Green’s

company (of the 2/7th) which was attacking on McNally’s right and also under Sell’s command. The platoons in the centre and left, however, and Smith’s headquarters, lost every officer and many men soon after they left the protection of the wadi. Lieutenant Laing56 was killed and Lieutenant Unkles57 wounded; and in a few minutes about half the men had been hit. Sergeant Symington,58 a veteran who had served as an officer with the NZEF in the war of 1914–18, was seriously wounded, yet he crawled in front of Smith to protect him and insisted that Smith rest a Bren gun on his body to fire it. While lying there, the gallant Symington was hit again and killed and Smith was wounded.59 Thus, in a few minutes, all the officers except McNally, and all the senior NCOs, were out of action.

Captain Balcombe Griffiths’ company emerged from the wadi into this deadly fire as soon as the leading company had advanced 150 yards. In the first rush this company lost eighteen men including one officer, Lieutenant MacFarlane,60 and was pinned down on the flat plain, the leading sections lying side by side with the survivors of Smith’s company. Seeing that to advance farther across the open could lead only to the loss of what was left of the two companies, Griffiths, a cool and able tactician, who was with his leading platoon, decided to withdraw his men to the wadi, attack along it, capture the guns and thus enable Smith to continue the advance. He ordered each platoon in turn to trickle back in twos and threes across the shell-swept plain into the wadi; Lieutenant Bradley’s61 platoon, which was forward, to come in last with the company commander and his headquarters. This policy succeeded, and there were no casualties during the retirement. Having observed this withdrawal McNally also brought the survivors of his platoon into the wadi, where he learnt how greatly the company had suffered and that he was the only officer remaining!62

In the wadi Griffiths found a detachment of 3-inch mortars under Sergeant Lawson Wilson63 and a platoon of machine-gunners of the Northumberland Fusiliers. He ordered them to engage the Italian guns. The Fusiliers put their guns into action as if on the parade ground with a speed, determination and nonchalance which greatly impressed the Australians. Their range-taker gave the range – 800 yards – to the mortar-men

of the 2/5th. Wilson went up on to the bank of the wadi where, kneeling in full view of the enemy, he gave his men targets, and his mortars and the British machine-guns began systematically to silence one Italian gun after another.

During this bombardment Griffiths sent Lieutenant Bradley’s platoon down the wadi to outflank the guns. News of the failure of the advance had now reached battalion headquarters. Lieutenant Shave joined Griffiths and was wounded. Then Sell came forward. Griffiths told him what he had done and that he proposed to follow Bradley and attack along the wadi. To this Sell agreed. As he moved along the wadi, Griffiths picked up Sergeant Morse64 of the battalion’s reserve company which was now moving into the wadi. Together they reached the foremost section of Bradley’s platoon, well on the flank of the Italian gunners, some of whom were now waving white flags. About sixty Italians came over and gave themselves up. Griffiths then saw a battery of four guns farther along the wadi, on the western bank. He went forward with Morse to reconnoitre. After having taken cover for some minutes from a prolonged concentration of mortar fire, he sent Morse back for a few men. Morse soon arrived with Corporal Shattock65 and his section, who rushed the guns and took the surrender of 100 more Italians. The remainder of the platoon then advanced along the wadi. The shell of the Italian defence round the Scemmas had been cracked and the twenty or so infantrymen were deep among the Italian artillery positions. They acknowledged the surrender, first of an Italian medical post, then of an anti-aircraft battery of four guns. On the eastern bank, round a sharp bend, four field guns were found. Corporal Cameron’s66 section moved forward and fired a few bursts from the rear, whereupon about forty Italian gunners surrendered.

Thenceforward pickets of two men each were posted along the wadi to usher back the prisoners who now outnumbered the Australians ten to one. Round the next bend in the wadi the infantrymen came face to face with a line of four or five stationary two-man tanks, all unmanned though two had their engines running. Before they could be manned, the Bren

gunners had sent a burst among them and about 200 Italians surrendered. Beyond the next turn the floor of the wadi fell steeply away, forming an amphitheatre about seventy-five feet deep with almost precipitous sides. At first there were no signs of life but, when Morse fired a shot into the pit, about seventy Italians, including twenty-five well-dressed officers, began to appear at the openings of a dozen caves and dugouts waving white flags. It was the headquarters of an artillery group, where the staff had been living in complete security against shell fire from the landward side and in considerable luxury. There were enamelled baths, silken garments and cosmetics. The notepaper in the offices was embossed and the glasses in the messes were engraved.

Leaving Morse in command, Griffiths returned to Sell’s headquarters, driving an Italian car, to report what had happened. It was then 1.30 p.m. Soon after the departure of Griffiths, Morse saw some heads behind a wall 500 yards farther along the wadi. Taking one man with him he advanced firing and shouting to the Italians to surrender. The Italians obeyed and the two men here collected another 200 prisoners whom they shepherded along the wadi. Fire from his own artillery now began to fall along the wadi whereupon Morse, leaving the prisoners to move along the exposed eastern bank, withdrew his own men down the opposite bank to the captured Italian headquarters whence the long stream of prisoners straggled back along the Scemmas.

When he heard of the initial setback to the 2/5th Brigadier Savige, commanding the southern brigade, had sent his brigade major, Brock,67 forward to help to reorganise the attack. Brock arrived about 1 p.m. as Griffiths was advancing to capture the guns. He found the three forward companies of the 2/5th withdrawn to the Scemmas and the left flank open and overlooked by the enemy. The supporting artillery barrage had now moved a considerable distance ahead, according to plan, and was no longer masking the Italian guns immediately ahead, the companies were somewhat mixed, and the confusion was being increased by the presence of perhaps 3,000 Italian prisoners in the wadi. Brock brought forward Captain Savige’s68 company of the 2/7th Battalion, which was in reserve, and directed it to the Triangle – originally Smith’s objective; later he intercepted two tanks which had now arrived and ordered them to accompanying Savige. Griffiths with some twenty men was directed to Twin Wadis on the near side of Little Italy. Later the remaining company of the 2/5th occupied the road angle east of Iponticelli.

–:–

Meanwhile, undeterred by the setback on the left, Green’s company had been steadily advancing. It had formed up on the Bardia road ready to advance with the 2/5th at 11.30 a.m. when Green learnt that tanks would not be available to support him. As his men waited for the advance to begin they came under fire from the Italian batteries that were to stop

the companies on the left, and Green sent Lieutenant Evensen’s69 platoon forward on to a spur to try to subdue these guns while the rest of his company advanced against the perimeter posts. Evensen was wounded there.70 Meanwhile Lieutenant Davis’71 platoon attacked and took Post 27, Davis and others being wounded. Green’s plan was to advance on a two-platoon front, the inner platoon taking the posts along the inner line and the outer platoon the posts along the outer line. The flat ground was swept with machine-gun fire and by shells “skidding knee high”, as one of the infantrymen described them, but the men were well dispersed with twenty yards between each, and casualties were consequently so low that here, as elsewhere, some Italians, puzzled by the way in which the Australians kept moving forward through such fire, were convinced that their shining leather jerkins were bullet-proof. At each post the Italian fire was subdued with Bren and rifle; the thin line of attackers then moved forward; and when the leaders were close enough to begin lobbing grenades round the machine-gun pits the Italians surrendered.

After Post 24 had been taken two tanks arrived and, though his fuel and ammunition were nearly exhausted, their commander said that he would accompany the infantry. These were the tanks which Brock had directed to join Savige’s company; in error they joined Green’s. Post 22 was then taken (a command post manned by twenty to thirty troops). Lieutenant Webb,72 the third platoon commander, was wounded there, leaving only two officers – Green and his second-in-command, a slender, fair lieutenant named Macfarlane.73 As these two stood watching some of the prisoners being rounded up an Italian bobbed up from one of the pits, put a rifle to his shoulder and shot Green through the chest. He then dropped his rifle, put up his hands and climbed out of the post, smiling broadly. An angry Australian threw him back into the post and emptied his Bren gun into him. At the same time others demanded of Macfarlane that they should be allowed to bayonet all the other prisoners, but Macfarlane – now the only officer in the company – forbade them to take revenge, and was obeyed.

The Italians in Post 25, on the skyline 500 yards away, having witnessed this incident, sent out an emissary who could speak English and surrendered without firing another shot. Macfarlane kept him as an interpreter. Sergeant Foxwell’s74 platoon took Post 23. By the time Post 20 had been reached – about 3 p.m. – one tank had returned to refuel and the second had shed a track and could not move. Macfarlane’s company –

what was left of it – now faced the Switch Line. Two Australians had been sent to the rear with each batch of prisoners from the first few posts, but later one rifleman was considered sufficient guard for fifty or sixty Italians. Even so Macfarlane’s company had been so depleted by casualties and detachment of escorts, that it now consisted of himself and sixty-five men. However, this company with little aid from tanks and in about three hours had taken six posts and widened the breach in the Italian line by 2,000 yards.

Major Starr’s company appeared on the left – the first friendly troops Macfarlane had seen since leaving the Bardia road more than two miles away. It was then about 4 p.m. Starr’s company had made a relatively uneventful advance parallel with Macfarlane’s. As they neared Little Italy Starr’s men had rounded up some 200 prisoners. Both Starr and Macfarlane were now under heavy fire from Post 16; Macfarlane called his attacking platoon back to the protection of Post 18 which looked at 16 across a depression – the end of the heel of Little Italy – and sent his recently-acquired interpreter to 16 to demand its surrender. Watching through binoculars he saw the Italian go to the post and bend over it. Presently a figure half emerged from the post and shot him. Thereupon Macfarlane’s men turned the Italian guns upon Post 16. Starr’s company was now in the toe of Little Italy on Macfarlane’s left.

The heel and leg of Little Italy had been reached by Captain Savige’s company some time before. At 2.45 Savige, on Brock’s orders, had begun his advance towards “The Triangle”, 3,000 yards away. His men advanced in very open formation, using their automatic weapons as they moved. Before they had gone 1,000 yards they were under gruelling fire from field and machine-guns from left and front. The line moved on steadily with its trucks following, the fire becoming more accurate and intense the closer it approached. Lieutenant Timms75 was fatally wounded. Two of the company’s trucks, following across the bare country, were hit by shell fire. Then the Australians found themselves close to a group of Italian batteries protected by machine-gunners – part of the strong concentration of artillery in the southern sector. The infantrymen attacked, manoeuvring forward under the fire of Brens and rifles and, after a half-hour fight, had captured eight field guns and many light and medium machine-guns. Here the two remaining platoon commanders, Lieutenants Howard76 and Arnold,77 were wounded and fewer than half Savige’s original ninety-six men were left with him. Three officers having been hit, Sergeants McDonald,78 Hoban79 and Corrie80 stood out as leaders. Savige pressed on

in cover of the wadi which leads eastward from The Triangle, taking the surrender of one machine-gun team after another, then of another four-gun battery. He was now deep in the enemy’s artillery positions and had at least 2,000 prisoners, but only forty-five of his own men; consequently, after scouting forward for 400 yards with seven men, and capturing four more guns, he decided to halt and establish himself in the Little Italy wadi for the night. Thither the signallers laid a telephone line from battalion headquarters so that he was able to report his position, but it was not considered feasible to send vehicles forward under fire from the remaining Italian batteries to fetch his twenty-three81 wounded. Thus Savige’s company, like Macfarlane’s, by a skilful and resolute advance maintained in spite of severe losses, had established itself on the objective.

On the right, however, neither Macfarlane nor Starr had been in communication with battalion headquarters during the afternoon, or knew the course of the battle since the repulse at the Wadi Scemmas. They planned a concerted attack on Post 16 at dawn, using captured weapons. About midnight, however, Major Marshall,82 second-in-command of the 2/7th, arrived, to say that Brigadier Savige had ordered the Switch Line to be cleared as soon as possible.

–:–

It will be recalled that Savige’s brigade was fighting in two widely-separated sectors, and that as soon as he had learnt of the setback to the 2/5th he had sent his brigade major to it to help in reorganisation. Later in the afternoon he sent his Intelligence officer, Lieutenant Schofield,83 forward to his northern sector with orders that Lieut-Colonel Walker,84 the trusted commander of the 2/7th, was to take command of all troops in the Switch Line area. Schofield returned from this task at 7.30 p.m. and reported on the situation of the northern battalions. Thereupon Savige, leaving his staff captain, Bishop,85 at his headquarters to keep in touch with Godfrey, himself went forward to the 2/5th. There he found the situation “extremely confused; the attack was stagnant.”86

Griffiths, with only 20 men, was unable to gain any contact with other of our troops and had been and was under heavy gun fire over open sights, MG and mortar fire (he wrote later) . He therefore wisely decided to withdraw. Sell and his adjutant were feeling the effects of a particularly gruelling day and were unable to locate Starr. Savige was fighting guns firing over open sights and stoutly resisting machine-gunners and people serving mortars. He could be depended to hang on despite the fact he, too, had lost officers. Bennett87 with A Coy 2/5 Bn, was at Road Angle. The gap in the left flank was extremely dangerous.

Savige now conferred with Walker and Sell. In obedience to the order conveyed by Schofield earlier in the

afternoon to take over part of the area west of the Switch Line, Walker had gone forward, leaving instructions for the remainder of the battalion to be brought up. He had called at the 2/5th’s headquarters and gone on to Post 20 whence he could see Macfarlane’s men attacking Post 16 and, farther left, heavy fire and dust marking the whereabouts of Captain Savige’s company. He decided that the best plan would be to use one of his two fresh companies – Halliday’s88 – on the posts of the outer perimeter and to build up strength on the left by directing Macfarlane to continue against the Switch Line and close the gap between himself and Savige. The Brigadier adopted this plan and gave comprehensive orders for reorganisation and the advance.

Halliday (D Coy 2/7 Bn) to push on through Macfarlane and fight his way southward during the night. Macfarlane was ordered to do likewise along the Switch Line. Starr 2/5 Bn who was thought to have his company about Post 20, was ordered to occupy Twin Wadis. A composite company from personnel of 2/5 Bn was organised and placed under command of Capt J. W. Duffy89 and ordered to occupy [part of the Scemmas] send out a patrol and link up with 16 Aust Inf Bde. The area was divided into two sectors – Walker in command of forward sector, Sell in command of rear sector.90

The sector boundary was fixed – a more or less east-west line. Savige then established an advanced headquarters in the ditch by the Bardia road with a telephone line through Sell’s headquarters to his main headquarters. His link with Walker was by liaison officer.

It was the above orders which Major Marshall carried forward to Halliday (who had arrived within the perimeter about dusk and whom Marshall reached about midnight), and to Macfarlane. In detail, the order to Halliday provided that he should open his attack at 12.30 a.m. and not push beyond Post 10. Halliday had met Macfarlane’s company at Post 18 about 9 p.m. and taken up a position at Post 21.

In obedience to the new order Macfarlane advanced along the Switch. He gave Sergeant Foxwell the task of creeping up to Post 16 in the darkness,

cutting gaps in the wire on the western side, and leading his men silently against the Italian garrison. Macfarlane himself with another platoon was to make a simultaneous attack while the third platoon remained outside the wire. As the attackers charged, a Bren gunner fired his weapon and gave the Italians warning, but before they had time for more than a few shots and grenades Macfarlane’s men were over the entrances, dropping in grenades, jumping down into the concrete-lined pits and trenches, flashing torches (which they had taken from Italians earlier in the day) and demanding surrender. Employing the same tactics Macfarlane then went on and took R11, the second post along the Switch Line.

The company’s only compass had been with Green, and Macfarlane now had none. However, having found a shallow “crawl trench” he deployed his men and began following it, as he believed, towards R9, but soon realised that he was going astray. He halted his men, very quietly for they could hear Italians speaking nearby, and waited for dawn.

At dawn Macfarlane led his men to within 400 yards of Post R9 and organised an attack, but the fire from the now alert Italian post was too heavy. Private Jinnette91 who had been in the forefront all through the battle went back under fire to Starr to ask for a 2-inch mortar. Starr sent this forward and, with its help, Macfarlane’s handful of men attacked and took R9 from which emerged about forty prisoners. Shell fire was still coming from batteries only 300 to 600 yards away to the north-east and mortar fire from the next post along the Switch Line. Macfarlane’s men took shelter with their prisoners in the anti-tank ditch and engaged the next post. From the eastern end of the post Corporal Taylor,92 a high-spirited and courageous soldier, engaged in a twenty-minute duel with an Italian battery clearly visible about 300 yards away. Taylor was one of a number of first-rate rifle shots, mostly from the irrigation areas of north-western Victoria, who had joined the 2/7th. With his rifle he was hitting Italians as they ran from one sangar to another carrying shells to the gun. Eventually the Italians swung one gun off its more distant target and began firing at Taylor and those with him. One of their first shells hit the edge of the machine-gun post from which he was firing. Macfarlane anxiously hurried to the far end of the post where he saw “a big red-head shouldering off bits of concrete and saying with a giggle: ‘See, the bastards don’t like it’.”

Sergeant “Joe” Solomon93 and some others with Taylor tried without success to turn the abandoned Italian weapons against the next post whence an Italian machine-gun was firing accurately at R9. Solomon hit the man at the trigger of the Italian gun and was peering along his rifle

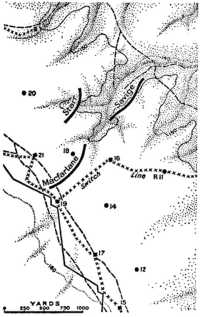

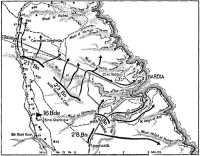

Soon after dawn 4th January, forward companies, 2/5 and 2/7 Battalions

for the next gunner to appear when the gun reopened fire, killing Solomon instantly.94

While this fight was still in progress Macfarlane received the order to lie low because his own artillery was about to fire concentrations along the road which passed through the Switch Line nearby.

Halliday’s company on Macfarlane’s right had set off about 1.30 a.m. His tactics at Post 19 were to send a few scouts forward from a covering platoon while his two remaining platoons worked their way to the opposite side of the post and attacked with fixed bayonets. In this style he took, at 2.30 a.m., Post 19 with 73 prisoners and, at 4 a.m., Post 14 with 64, for a loss of one man killed and 7 wounded, Lieutenant Bernard95 being in the forefront in each of these encounters. Post 17 was on the alert and a prolonged fight took place; it was daylight before it was taken. Halliday now held 103 prisoners and his company was only 46 strong, parties having been sent back with prisoners. He decided he should not try to go farther without support. Thus, soon after dawn, Halliday was at Post 17, Macfarlane at R9 with Starr nearby and Captain Savige in the Little Italy wadi farther north. Duffy had patrolled along the Scemmas to a point overlooking Bardia town.

The original plan had been perilously complicated; and, as a result partly of the failure of the tanks to appear on time, partly of the strong resistance of Italian gunners which had stopped the 2/5th’s attack in its first few minutes, largely of lack of artillery support, the fight had not gone according to plan.96 However, the courage of the men and the determination of young leaders (particularly Macfarlane, Savige and Griffiths) to carry on to the objective saved a situation that was causing anxiety at brigade and divisional headquarters; and in a short afternoon the survivors of the

midday set-back had driven deep into the Italian artillery positions, captured at least sixty guns and some thousands of prisoners, seized 3,000 yards of the Italian perimeter, and (by the early hours of the second morning) had taken half of the Italian Switch Line. The six rifle companies that had been engaged had taken prisoners from the four infantry regiments that comprised the infantry of the 62nd and 63rd Divisions. And with little aid from the tanks which were to have led them into the attack, they had taken and passed the allotted objectives.97

–:–

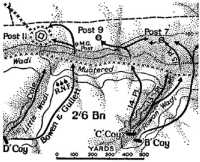

It will be recalled that, while the 16th Brigade broke through the Italian perimeter in the early morning of the 3rd, Godfrey’s 2/6th Battalion was to create a diversion seven miles away at the southern end of the perimeter. It now remains, before leaving the events of the first twenty-four hours on the left flank, to describe the fate of this “diversion”, carried out in the area in which elaborate efforts had already been made to persuade the Italians that the main attack would fall. By aggressive patrolling the 2/6th had gained control of all the country up to the south bank of the Wadi Muatered along the top of whose north bank was a line of Italian posts similar to those round the remainder of the perimeter but somewhat closer together. To assault them an attacker would have to climb 150 to 200 feet down the steep southern side of the wadi, cut a path through the wire there and then climb the northern side. To command every part of the wadi, the Italians had established small sangars forward of and between the numbered posts.

Godfrey’s orders to his companies were that, by 5.15 a.m., Captain Muhlhan’s98 company on the right, Captain Rowan’s99 in the centre and Little’s on the left would move in darkness and (so far as Rowan’s and Little’s were concerned) under cover of the two tributary wadis which Savige had named after them to within 400 yards of the Muatered. The remaining company (Lieutenant Kerr100) would be in reserve. Fifteen minutes after the bombardment opened the two leading companies on the left would occupy the north bank from Posts 7 to 11 while Muhlhan’s would establish itself on the right as far left as Post 3. One platoon (Lieutenant Sherlock’s) was posted on the extreme right near the top of the cliffs leading down to the sea.

The plan of Captain Little, whose company was to take Post 11, was to send two platoons across the open ground on the right of Little Wadi, and thence across the Muatered to attack the post from the right. Artillery fire was to shield them until they reached the Muatered. When it lifted, the fire of machine-gunners of the Northumberland Fusiliers was to beat

upon the post while the attackers reached the wire round it and fired a Very light – the signal for the machine-gun fire to cease – while the remaining platoon rushed the post from the front and the nearer platoons cut their way through the wire and attacked it from the left. By a last-minute decision Little posted the nine Bren guns of the company with the Fusiliers to thicken the barrage and thus the attackers went in with only rifles and grenades.101

When the attack opened the platoons on the right, commanded by Lieutenant Bowen102 and Sergeant Gullett,103 crossed the high ground, climbed down into the Wadi Muatered, cut gaps in the ten-foot-wide barbed-wire apron there, and clambered up the farther bank without a casualty, though Italian shell fire was now falling heavily along the wadi and tracer bullets were flying overhead at the Northumberland Fusiliers who were pouring fire at Post 11 from the southern bank. At the top of the far bank the attackers encountered a machine-gun post whose men were put out of action with one grenade. The two platoons, forty-three men all told, moved forward to the wire surrounding Post 11 and cut a passage, still without losing a man, though they were sure they could be seen and that the Italians were deliberately holding their fire. Bowen now fired his signal light and the men jumped to their feet and charged, moving as fast as they could and shouting. Bowen’s platoon was on the left, Gullett’s on the right. The trench that formed the outer edge of the Italian post was forty yards from the wire and the attackers had covered half this distance when fierce and sustained machine-gun and rifle fire opened from the post and grenades began to fall among the Australians. In a few seconds nearly all the attackers were thrown to the ground. Flares were lighting the area like daylight and there was no cover. On the extreme right Corporal Latham104 and several men of his section reached the trench first; and on the extreme left Bowen reached it but was killed soon afterwards. Sergeant Millar105 of his platoon organised a bayonet attack against Italians in sangars nearby, but he, too, was killed (by an Italian who had just surrendered). Four who survived took shelter in a sangar where two hours later they were taken prisoner.

By this time several men had obtained a footing in parts of the trench, having torn up the loose planks that covered it and jumped in but, in the mêlée, nearly all were killed or wounded. Latham was wounded, mortally. Most of the fire was coming from machine-gun posts beyond the trench and near the centre of the post.

Gullett led three of the men who were still unhit – Sergeant Scott106 and two brothers named Damm107 – against each of these posts in turn and silenced the crews. On one sortie Gullett and Scott were knocked down by a grenade. As they lay Scott was hit again and killed and Gullett was hit twice and stunned. Eventually he struggled back to the part of the outer trench where Latham had first obtained a footing, and there found Corporal Maloney108 and several others wounded but only one unwounded man – Private Brockley,109 a driver who had left his post to join in the attack, because, he said, “he felt like a bludger sitting at battalion headquarters, and wanted to be in it.”

It was now dawn and no sounds came from Bowen’s end of the trench. One part of the Italian post – evidently an ammunition store – was on fire and the flames lit up the area brightly. It seemed that all Bowen’s men were killed or wounded. Gullett ordered the others, of whom only three were now unwounded, to abandon him and go back, but Brockley lifted him and helped him along, while Bernie Damm carried on his back his brother, who had been hit in both legs. They had moved only a few yards among the rocks when the Italians began to cut them off, but Maloney, Brockley and Damm, with their rifles, kept them back. In one of these skirmishes Claudie Damm was hit again and killed. The survivors stumbled down into the wadi, under fire from Post 9. Some Italians ran out of this post to intercept them but Damm shot one dead and wounded another. In the wadi they were unable to find the gap through the wire, but cut a new one and lay among some bushes until mortars from their own lines began dropping bombs among the Italian weapon pits that overlooked them. This quietened the Italian fire and the four men climbed to the exposed top of the northern bank, where they spread out and ran for shelter. Here Gullett and Maloney were again hit, but Maloney was able to help Gullett to safety. Of the forty-eight men who had gone into the attack only these four returned that day.

While this fight was in progress the remaining platoon, Sergeant Cole’s,110 had taken up a position in the wadi fifty yards in front of the wire. There one man was killed and one wounded. Captain Kiddle111 went forward,

saw that they had little chance of advancing through the intense fire, and returned to report to Little, while the men of Cole’s platoon cautiously built up little walls of stone for shelter. About 8 o’clock, while Little and Kiddle were conferring in a tributary wadi, an Italian mortar bomb had landed near them and wounded them, Kiddle mortally. Lieutenant Warfe112 led three carriers into the wadi, fired on the sangars round Post 11 and brought in the wounded Little. Cole’s platoon remained behind its stone shelters all day firing on such targets as offered. The company was now commanded by its sergeant-major, Cowie,113 who led the remaining men forward as far as the fire would allow; and with them the Fusiliers, who coolly fired at Post 11 from this exposed position, losing one man after another until only one gun remained in action, manned by the platoon commander, Sergeant-Major Bell, and the company quartermaster sergeant.114

On the right of Little’s company, Rowan’s had attacked, one of the two leading platoons aiming at Post 9 and the other at 7. The left platoon (Lieutenant Paterson) reached the bottom of the wadi, cut the wire about 150 yards from Post 9, lay among the bushes there to reorganise, and then dashed up the slope spread across a front of about 150 yards. There they ran upon Italians in sangars. Attacking only with grenades they killed twenty-five, took forty-seven prisoners and established themselves, under constant fire from the front and from posts to the left. The right platoon reached the wire at the bottom of the wadi at about six o’clock, and there came under intense fire. Men began to filter back. Rowan, seeing this, ordered the commander of this platoon to reorganise and sent a second platoon against Post 7, but it too was held at the mouth of Rowan wadi. At this stage Privates Phillips,115 Streeter116 and Weston117 of Paterson’s platoon advanced along the north bank of the wadi, attacked with a Bren gun and grenades, and soon the post was occupied.

Muhlhan’s company meanwhile had gone through the Muatered and occupied some 400 yards of the north bank. During a determined counterattack by the Italians it occupied Post 7 and took charge of the prisoners there. The Italian counter-attack lasted an hour, but the Victorians held their ground. Ammunition running low, Phillips made four journeys through the fire-swept wadi draped with bandoliers. There was another unsuccessful counter-attack at 3.30 and a third, by about 300 men, at dusk. Thus, at the end of the day the 2/6th held a front of about 600 yards along the north bank of the Wadi Muatered and held Post 7 and

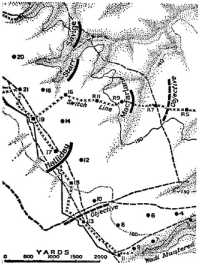

Situation southern flank, dusk 3rd January

part of Post 9 – it had cost, according to the estimate at dusk, thirty-eight killed or missing and twenty-six wounded.118

Meanwhile on the extreme right of the 2/6th’s position the Italians had made an effective raid on one of the observation posts of the 2/2nd Field Regiment which was supporting it. Major Arthur,119 with Lieutenant Crawford,120 Bombardier Russell121 and some signallers, had established an observation post on the old Italian frontier wire only a few hundred yards from the edge of the cliffs on the east and the Wadi Muatered to the north. The main concentration or the 2/6th Battalion was nearly two miles to the left. This observation post was to have been protected by the platoon under Lieutenant Sherlock who had originally found the post), which, it will be recalled, was placed on this flank but (according to Sherlock) Arthur’s party did not arrive at a rendezvous and he was unable to find the party. Sherlock’s task was not only to protect this post but to prevent the escape of the Italians southwards. When dawn broke Arthur found that he was looking into the Italian “backyard”. Between his post and the Switch Line were guns, ammunition dumps and observation posts, including the now-familiar ones consisting of a tall pole with a steel drum on top for the observer to stand in. By this time the regiment had begun to fire according to its pre-arranged program, but, by increasing the rate of fire of other guns, Arthur was able to direct the fire of one gun on these new tempting targets. He became anxious about the absence of infantry. At length a party appeared 500 yards on his left, but when he went to see them they had no officer and he found them vague about their future movements. After Italian shells began to fall round his post, Arthur decided to move into a concrete building just beyond the wire a few hundred yards to the right. There he and others observed from the roof while the telephone was operated from within the house, and thence Arthur

directed fire on the Italian guns until a long burst of machine-gun fire drove the observers off the roof. Arthur, now inside the hut, was listening to the voice of Colonel Cremor reporting on the telephone that Lieutenant Nethercote,122 another observer, had just been killed and warning him to be careful when there was a scuffle and a shout of “Mani alto!” He turned and saw the muzzles of several Italian rifles. Without further warning three grenades exploded in the building, wounding Arthur seriously in both legs and Crawford slightly but leaving Russell unscathed. Crawford and Russell were escorted away by the Italian patrol while Arthur lay in the house tying ligatures above each knee with signal wire. A second Italian patrol eventually carried him to the Italian lines.

Nothing but good news had arrived at Mackay’s headquarters during the morning of the battle. From 7.3 a.m. onwards reports were wirelessed from a carrier posted near the gap in the Italian line (and in the thickest of the shell fire) for this purpose. At 9 a.m. Major Campbell telephoned to Colonel Berryman from 16th Brigade’s headquarters in Post 40 his estimate that they had already taken 8,000 prisoners. About 11 a.m. Mackay went through the shelling in one of a troop of light tanks to see for himself and for two hours coolly watched the developing battle.123

During the afternoon, however, lack of definite reports from 17th Brigade caused some anxiety to Mackay’s staff and this was not alleviated by a message from the 2/2nd Battalion that they did not know where the 2/5th was, except that part of it was behind the 2/2nd. (In fact both were in their correct areas and hidden from each other by the rough country.) At 3.20 p.m. Mackay, hearing of this, ordered that the 2/8th Battalion of the 19th Brigade should move to the right of 16th Brigade and come under its command. About an hour later Berryman, going forward to Allen’s headquarters, passed two companies of the 2/7th moving towards the perimeter and two miles and a half away from it and decided that they could not “do more than arrive inside the perimeter that night.”124 When he arrived at 16th Brigade headquarters he discussed the situation with Brigadier Allen, Colonel Jerram of the 7th Royal Tanks and Frowen of the British medium artillery, and finally gave orders that next day Allen, with all available tanks and with the support of Frowen’s guns, should cut off the town of Bardia. Allen told Berryman that he agreed, but asked whether Berryman could give him these instructions without the approval of the general. The staff officer assured Allen that Mackay would agree; “there’s no other plan in the field,” he said. Thereupon Allen began to prepare an attack for the following day; about midnight the thrustful Berryman telephoned confirmation of the order.

Meanwhile, during the afternoon the 16th Brigade’s line had been under intermittent fire, but there was no sign of an effective counter-attack developing. On the left Travers’ company of the 2/1st was at 1 p.m. still being held by Posts 55 and 57 (51 had been taken by Lieutenant Rogers’125 platoon now on Travers’ left) and mortars were sent forward to help him. The mortars and a troop of the 104th Royal Horse Artillery bombarded Post 55, which Kennedy then took without casualties at 1.30, while Rogers took 53. Again with the support of the guns of the Royal Horse Artillery and the battalion’s mortars Travers’ company took Post 57, with about forty prisoners. Kennedy was reorganising this post when to his surprise he saw a white flag waving above 59 on the other side of the wadi; Travers sent Kennedy forward with two sections and a carrier and they took the surrender of some fifty men without firing a shot. However, the battalion’s flank was now insecurely extended and in the evening Travers was withdrawn to Posts 53 and 55; the enemy still held 54 and thus during the night there was a wide no-man’s land on this flank.

On the right of the 16th Brigade the squadron of the 6th Cavalry was withdrawn into reserve during the afternoon and the 2/2nd Battalion sidestepped to the left and took over its position, the 2/5th now occupying the area formerly held by the 2/2nd.

That night Berryman, who had reached the conclusion that the 17th Brigade was disorganised and tired, and that by the end of the second day the 16th Brigade would be too fatigued for further effort, decided that fresh troops would have to be obtained to finish off the battle. Early the following morning he called Robertson and Herring to a conference, described the situation as he saw it, and said that, if the Italians did not collapse during the day, he thought the remaining two battalions of the 19th Brigade should be launched against the Italians still holding out against the 17th Brigade. When Berryman presented this proposal to Mackay, the older soldier, who was less anxious about the position, said that General O’Connor had asked him to take Bardia with only two brigades, leaving the third fresh at the end of the battle. While they were discussing this, O’Connor and Brigadier Harding,126 his senior staff officer, arrived. With Mackay’s permission Berryman put the plan to O’Connor,127 who, after a few minutes, agreed to it.

In warfare it is not unusual that, after a set-back, anxiety increases in proportion to the distance from the enemy. If the 17th Brigade was disorganised (as Berryman believed) that disorganisation had been imposed only partly by the enemy and partly by a divisional plan which had split the brigade into two widely-separated groups, and to inadequate tank and (in the later stages) artillery support. The companies who were pressing the southern pocket of the defences would have been surprised to learn that they were believed to be a spent force. But they were tired. The truth

was that the brigade was reaching the end of its strength and, in spite of its gallant efforts to strengthen its fire power by using captured guns, could not make further substantial progress against a well-fortified and still aggressive enemy without the support of guns or tanks, or both, in effective strength.

Nevertheless, as described above, the forward companies of the 17th Brigade had fought on all night and, at dawn, Savige decided that “the position, which at midnight appeared to be hopeless, was secure”. He decided to remain in his northern sector and hand over the southern to Godfrey, with Bishop remaining at what now became his rear headquarters. With Cremor of the 2/2nd Field Regiment and Frowen, who arrived at his headquarters on the morning of the 4th, he arranged counter-battery fire on the remaining Italian guns and harassing fire on Posts 4, 6, 8, 11 and 13. He decided to continue the attack and capture Posts 12, 15, 10 and 13 on the right, and on the left, the next two posts along the Switch. Lieutenant McGeoch’s128 company of the 2/7th – the only company not yet committed – had arrived on the field late on the 3rd and occupied Post 16, where, next day, it was under intermittent artillery fire.

While Savige was conferring with Walker and Sell about 11 a.m. concerning this plan, Lieut-Colonel Barker129 of the 2/1st Field Regiment arrived and artillery support was again discussed. It was decided that because of “the difficulties of communication between forward troops and guns, and the exposed nature of the ground, then being swept by artillery fire over open sights and machine-guns”, the attack should be delayed until it could be carried out under cover of darkness. Barker was asked to bombard the posts to be attacked from 3.30 to 5 p.m. Sell was instructed to rest Bennett’s company and Griffiths’ for the night attack. The leading companies of the 2/7th were only from 35 to 45 strong and very tired.

On the right the 2/2nd Field Regiment, shooting with great accuracy, bombarded Post 11 at 10.25 a.m. and again at 3.30 p.m., obtaining direct hits on the post itself and the sangars around it and Post 9, whence the Victorians had withdrawn to comparative shelter under the north bank of the wadi; but the Italians not only held their positions but fought back strongly with artillery, mortars and small arms. During each bombardment they withdrew from the sangars to the shelter of the concrete posts, but reoccupied them when the artillery ceased fire. During the day Godfrey became increasingly worried by the mounting casualties, and after considering a night attack, abandoned the idea.

–:–

While divisional orders for the employment of the 19th Brigade were being prepared, the attack on Bardia town was in progress. The Bardia fortress was divided by a deep irregular depression, the Wadi Gerfan,

which begins outside the ring of perimeter posts and runs into the sea at the town itself in a deeply indented little bay. “Lower Bardia” lies on the northern shore of this inlet; “Upper Bardia” on a headland above it. At the end of 3rd January the 16th Brigade was strung out on a four-mile front on or overlooking the southern bank of the Gerfan, its line on the right crossing the tributary wadi Ghereidia. On the right two roads led away from the Australian positions, one to lower Bardia zigzagging in its final stages down the face of the cliff; and the other north across Gerfan where it joined at right angles a road which led east to upper Bardia and west to the perimeter and beyond.

Allen allotted a troop of three tanks and a company of the Northumberland Fusiliers to the 2/2nd on his right and ordered the commanding officer, Colonel Chilton, to clear the wadis leading to Bardia from the south, while the 2/3rd, with two tanks and Onslow’s cavalry squadron, pushed across the Gerfan to the road junction, whence the tanks and the cavalry would advance into upper Bardia while the infantry occupied a line north of the road. The 2/2nd had the support of a battery of the 7th Medium Regiment and the 2/3rd of the 104th Royal Horse Artillery. The 2/1st Battalion would continue the line to the left and clear the enemy from the western part of Gerfan. Chilton ordered two of his companies, Hendry’s and Godbold’s, to advance down the line of the Scemmas and attack an Italian fort on the southern headland of Bardia, while the three tanks moved on the high ground to their right. At 10 a.m. Hendry’s company was assembled at the crossroads and four hours later set off along the precipitous wadi. After three hours of climbing and having taken some hundreds of prisoners on the way, they reached the headland and at 4.45 attacked the fort in open order. The three tanks moved forward from the east to pit their 2-pounder guns against two 6-inch guns, two field guns and five lighter guns in the fort. (But the 6-inch guns were sited so that they were unable to fire inland.) The Italians held their fire until the tanks were 500 yards away, then their field guns opened fire and the tanks replied, their tracer shells hitting the walls of the fort and skidding off. Advancing slowly, the tanks closed in until they were cruising and firing only 400 yards from the fort, with the infantry close behind. One of the tanks made straight for the gate of the fort while the others continued to fire. The appearance of the tank charging towards them persuaded the Italians to resist no longer. They opened the gate and the tanks drove in and cruised round inside, about 300 Italians surrendering. In the dusk Hendry’s company then clambered down a goat track into lower Bardia itself and took some thousands of prisoners, while Godbold’s company which had advanced to the headland on Hendry’s right and Caldwell’s cleared out Italians who were sheltering in the little Wadi Helgh el Anz and elsewhere on the south side of the harbour.

Here where the Italian gunners had their backs to the sea and could discern tanks and infantry manoeuvring between them and the town of Bardia, they were in no mood to prolong their resistance. In addition large numbers of depot troops had now sought shelter in the wadis and the

artillery areas near the coast. About midday two carriers from the 2/5th Battalion went out into this country and returned with 1,500 prisoners. Captain Vickery,130 who had joined the 2/2nd Battalion at midday to direct the fire of guns of the 2/1st Field Regiment, was reconnoitring on the southern edge of the battalion’s area in a Bren carrier a little later when he saw an Italian battery which was being shelled by his own artillery. He drove his carrier towards them and fired on them from the rear, whereupon they surrendered. To his surprise he discovered about 1,000 troops waiting to surrender and shepherded them to the 2/5th Battalion. The 2/8th Battalion which Allen ordered forward to high ground south of the Wadi Homer collected some thousands of prisoners there.

On the left of the 2/2nd Onslow’s cavalrymen advanced across the Wadi Gerfan with the 2/3rd following on a three-company front. The tanks were late arriving and it was 10.30 before the line of infantrymen moved off. On the right Abbot’s company advanced across the flat ground and came to the Gerfan at a point where its banks are so steep that the men took off their greatcoats and haversacks and left them on the top before beginning to clamber down. As they descended some Italians appeared from the caves in the side of the wadi. The Australians shouted “Lashay lay army” (Lascie le armi – lay down your arms) at the top of their voices which echoed back from the opposite face of the ravine, and some 800 Italians obeyed and were sent climbing back the way the Australians had come. After a pause for a meal the infantrymen, now desperately tired, climbed on to the road beyond the north bank.