Chapter 17: The First Day

THE assaulting troops, with their vehicles, moved into position close to the Syrian frontier on the nights of the 5th–6th and 6th–7th June. Throughout the 7th they lay under cover. It was the first time in this war, or the one before, that British troops had hidden, like Germans, near a peaceful frontier ready to make a surprise invasion.

Our particular selection (wrote one soldier) was bounded on one side by the outskirts of an infantry battalion, on another by an anti-tank company, and at the rear by a low stone wall used by the local vendors to display their wares, where one could buy anything from a boiled egg to a bottle of cheap wine. The olive trees were dispersed widely enough to allow vehicles to move in almost any direction through the grove. The trees were low but capable of concealing the bonnets of vehicles, and were a useful shelter from the sun and reconnaissance planes during the day. Generally the practice upon arrival in the area was to run the bonnets of the non-essential vehicles beneath the olive trees, sweep away the wheel marks, and thenceforward restrict movement of vehicles to the roads through the area. Near Er Rama the men camped on the red brown soil (it had occasional rocky outcrops) beneath the trees or in the shelter of the trucks, singly or in twos and threes according to their inclinations, provided they were within the company area. The night was mild, a covering blanket ample. One ill-conceived method of concealing the presence of Australians in the olive groves at Er Rama was an instruction to distort the familiar shape of our slouch hats so to render them unrecognisable; but while it provided opportunities for the company humorists, as a measure of deception it was a dismal failure from the start. To the Wogs we were “Ostralees” when we arrived and “Ostralees” when we left.

For most of us the 7th of June was a day of rest. All our preparations for invasion had been completed. There was some last-minute checking of personal equipment, but for most it was a day for playing cards or draughts, reading, writing or merely talking. Men strolled around in shorts and shirts from group to group, occasionally pausing to fill a bottle at the water-tank, or sauntered over to other camps to see their mates. In other lines there were some simple but oddly moving church services during the day. Towards dusk, when it was usual to change into slacks and roll down shirt sleeves, a group of us gathered round the tailboard of a truck to swap yarns and discuss prospects for tomorrow. We were to move off before midnight and none but the most phlegmatic considered it worthwhile to sleep. A few were inclined to scoff at any predictions of a pushover, and regarded the projected slouch hat invasion as a prize piece of colonial impertinence. One said “All we’ve got to do tomorrow is walk in, wave our hats to the Frogs, and walk on.”

Most were full of confidence, yet this untried division was deeply conscious that it was faced with a test like that which its sister divisions had already passed through – the test which would prove that it was as good as the old AIF “All through,” wrote an historian of the 2/16th, “there was a grim determination to live up to the great fighting record of the old Sixteenth whose history had been widely read throughout the unit.”

On the morning of the 7th Brigadier Stevens assembled his unit commanders for a final conference. That day he learnt that the landing of the

commando battalion would probably be impossible on the 8th because of bad weather.

At 9.30 that night, four hours and a half before zero, the first troops had crossed the frontier. They were two small parties of rubber-shod men of the 2/14th Battalion and 2/6th Field Company, one of which was to cut the telephone wire leading from Ras en Naqoura to the post at the point in the road near Iskandaroun where the French had placed demolition charges, while the other overcame the guards at that point and removed the charges. Australian and Palestinian guides led the men to a Jewish farm colony at Hanita, where they were well fed in the communal dining room, and thence across the enemy frontier where it was unguarded and over the thorny hills. It was cloudy and fairly dark. One group, under Captain Gowling,1 branched off towards the road just north of the Ras; the other (Lieutenants Kyffin,2 Allan3 and Cowdery4 and fifteen men, including three Jewish guides and one Arab) went on until, about 3.30 a.m., after fifteen miles, they reached the road just north of the point near Ras el Bayada where they had been told the charges were. Kyffin left Lance-Corporal Wardley5 and three men to halt any vehicles coming from the north and led the remainder of the party southwards. Stealthily, and in the darkness, they examined various bridges and culverts and found that they were not mined. At one of these Allan was left with three men to block the road while Kyffin went on with the remainder to search still farther south for the mined road. About 5 a.m., when they were north of Iskandaroun, they were fired on from a strong-post built of stone. The Australians rushed the post and took it, and were rounding up prisoners when Allan, who had heard the firing, arrived with his men.

A long, grim fight began which attracted one group after another of French reinforcements. A party of Kyffin’s men attacked some French troops in a near-by orchard where a machine-gun was silenced by Private Henderson6 who attacked it with grenades; and a mortar was captured. Two of the Jewish guides were wounded. Kyffin’s men, still under fire from the orchard, mounted the mortar and a captured Hotchkiss gun on the roof of the post, and soon were exchanging brisk fire with a French column moving along the road from the north to meet the invader. Some trucks in this column were halted and their crews taken prisoner. Next appeared two armoured cars. A shot from the captured mortar stopped the leading car, the driver was killed and the crews of both cars surrendered. Twelve horsemen then arrived and, when fired on, scattered into the hills.

Wardley and his three men (two were Palestinians) were summoned from the northern post to reinforce the men on and round the blockhouse, which half the men manned while the remainder were still engaged against the Frenchmen holding machine-gun posts in the orchard.

It was about 7 a.m. when a loud explosion was heard south along the road; and both parties, Kyffin’s to the north and Gowling’s to the south, guessed that the road had been blown somewhere on the cliff face north of Naqoura. The demolition they had tried to prevent had been carried out.

After separating from Kyffin, Gowling with a platoon and four Palestinian guides, had reached the road a mile north of Naqoura just before 1 a.m. He found and cut the telephone wire and took up a position astride the road, which his men blocked with boulders. It was quiet until 4.30 when firing broke out round Naqoura and the waiting men knew that their battalion had reached that village. A few minutes later one of the Australians captured a Frenchman who said that he had been sent from Naqoura to give the alarm, because the telephone was dead – as Gowling had intended. Others – French customs officials and African cavalrymen – arrived from the south and were rounded up; at length Gowling held sixty-five prisoners and a captured car. He sent Sergeant Dredge7 and three others in this car towards Iskandaroun, where they came under fire and Dredge and Private Constable8 were wounded. This party was exchanging fire with the French troops there when the road was blown up.

Although Kyffin’s party had been wrongly informed that the road was mined north not south of Iskandaroun9 and had failed to prevent the demolition, the patrol had succeeded in clearing the road for some distance north of the demolition and had captured some thirty prisoners, a number of weapons, six vehicles including one armoured car, and more than thirty horses abandoned by African cavalrymen. Only one of their men had been killed – Corporal Buckler,10 who had evidently been shot while moving out alone into the orchard to attack a machine-gun there.

At 2 a.m. the main advance had begun. It will be recalled that the task of taking the three westernmost French posts and forming a bridgehead through which Colonel Moten’s column could advance along the coast road was given to the 2/14th.11 On the extreme left a platoon of that battalion advanced from the British Customs post south of Naqoura at 3 a.m. After moving forward in the darkness astride the road for about

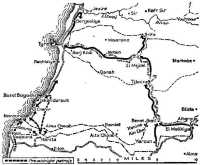

Advance of 21st Brigade, 8th June

one mile the leading scouts, Privates Wilson12 and Curson,13 encountered two French sentries whom they shot. It was 5 o’clock before they reached the wired post at Naqoura another two miles ahead, where the French opened fire. Lieutenant Ayton14 sent one of his sections to each flank and kept one on the road. For about five minutes the Australians exchanged fire with the garrison, which appeared to be using two machine-guns and about twenty rifles. Then, after firing a few mortar bombs, the centre section charged and drove the Frenchmen from the post and the village beyond, killing five men and capturing about twelve. Later a troop of Spahis opened fire from the village, but were driven off.

Stevens, restlessly moving from point to point in a carrier, ordered. that a platoon of the 2/27th be sent forward to discover the condition of the road. Lieutenant Rudd’s15 was dispatched, with six light tanks, two anti-tank guns and some engineers under command. Rudd passed through Naqoura about 6.30 a.m. and attacked a strong group of enemy troops covering the road. The 2-pounder guns went into action near the beach while the tanks advanced on the right of the road to within 300 yards of the enemy and engaged him with machine-guns. The infantry dribbled forward along the higher ground farther inland and after a sharp fight drove the enemy back. Five of the defenders were killed and two wounded.

East of the coast the hill country was so tangled that in the case of Lieutenant Farmer’s16 platoon that was to take the Labouna post the Jewish guide lost his way and the platoon did not reach the neighbourhood of Labouna until 5.30, three hours late. There it met an enemy patrol of six to ten men and, after an exchange of fire in which one man was wounded, charged with fixed bayonets and drove the enemy off. Labouna itself was occupied without incident. Farther east Captain Noonan’s17 company of the 2/14th rushed a French sentry

post and, with some difficulty, found the village of Alma Chaab and captured it after an exchange of fire in which Sergeant Lawley18 was killed and another man wounded. By 7 a.m. all three posts had been taken; but the brigade commander still did not know whether the road had been cratered ahead of him.

In the tangled country 20 miles to the east, Lieut-Colonel MacDonald of the 2/16th, to secure his bridgehead, sent in two companies of infantrymen, one, Major Caro’s,19 to Aitaroun and another, Captain Horley’s,20 to Yaroun; both were to converge on the village of Bennt Jbail.21 Honey was then to clear AM Ebel. Meanwhile an advance-guard under Major Potts,22 including a squadron of the 6th Australian Cavalry, two armoured car troops of the Royals, a company of the 2/16th and detachments of artillery and engineers, would wait at El Malikiya while a company of the 2/2nd Pioneers made a road able to carry vehicles thence to Aitaroun. When this road had been made Potts’ force was to move along it to Tyre and on, by the coast road, to Beirut – if possible.

Caro’s company took Aitaroun without opposition, capturing four unwary men in a police post there, and, moving through the hills towards Bennt Jbail, encountered a French post equipped with machine-guns. Lieutenant O’Neill23 led his platoon forward and captured the posts, losing one man killed24 and one wounded – Corporal Holmes25 who continued to lead his men until the fight was won. Caro arrived at Bennt Jbail to find that Horley’s company, having taken the sentries at Yaroun unawares, had marched on to Bennt Jbail where there had been a sharp fight in which the West Australians dispersed about seventy Spahis, killing several of them!26 Ain Ebel was found to have been abandoned by the enemy.

Working furiously, a company of the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion quickly made the track linking the Palestine road at El Malikiya with the Syrian at Aitaroun and, about 4 a.m., Potts’ advance-guard crossed the frontier. About 6.30 Lieutenant Mills, an outstanding leader in the 6th Australian Cavalry during the operations in Cyrenaica, with thirteen carriers of his own regiment, followed by a platoon of Captain Johnson’s27 company of the 2/16th in trucks, led the spearhead of Potts’ force through

Bennt Jbail to Tibnine, a picturesque town with an old Turkish castle. There they caught up and drove off what were left of the Spahis whom Horley’s company had expelled from Bennt Jbail earlier on. There was a pause in Tibnine while the friendly mayor of the town telephoned his colleague in Tyre and, after talking with him, informed the advancing troops that they would be welcome there. After waiting for two troops of the armoured cars of the Royals to join the vanguard, Mills moved on. Between Tibnine and the coast Mills’ vanguard had a series of skirmishes, but the enemy were too dispersed to resist effectively and, just before 2 o’clock, his leading cars and carriers drove up to the cross-roads outside Tyre, where they saw a British naval force standing off the port and French aircraft bombing it.

The naval squadron had neared the coast about 6.45 a.m. “Occasional troops and lorries which could not be identified as friend or foe were seen but the extent of the army’s progress could not be established.” The demolition of the road north of Iskandaroun was seen at 7 a.m. The destroyer Kimberley shelled French positions near the Litani Bridge for half an hour.

On land the armoured cars of the Royals, now in the lead, moved north along the road and met no enemy troops, except some Spahis, some of whom they captured while others rode off into the hills, until they were halted by a road-block just south of the Litani. Some men dismounted from the cars and were dismantling the road-block when the French opened fire from the north bank of the river with field and anti-tank guns and mortars, whereupon the Royals briskly withdrew, leaving two damaged cars behind. Lieutenant Dent’s28 troop of the 6th Australian Cavalry (reduced to one carrier), which had followed the cars, also ran into the French fire; with the surviving cars the carrier turned off the road to the shelter of the wadis where the guns continued to shell them. Two guns of the 2/4th Field Regiment, which were with the advance-guard, deployed and opened fire from positions near Bergouliye. Soon only one of the armoured cars was still undamaged, and it remained in the doubtful shelter of the wadi while Dent’s carrier withdrew with French shells chasing it. The carrier broke down; Dent sent his driver, Trooper Jubb,29 back with a message and, after waiting in vain for a reply, went back himself leaving the remaining member of his crew, Corporal Britten,30 to mount guard over the disabled carrier with the Bren gun. He remained there, all night, a one-man outpost. That evening patrols of the leading company of the 2/16th moved to within 800 yards of the river and reached the conclusion that no French troops were south of it.

While the advance-guard of MacDonald’s column was thus pressing on roundabout through the hills to within sight of the Litani, known to be the main enemy line of resistance, Stevens’ chief anxiety had been to learn whether or not the road had been cratered at Iskandaroun, and whether the coastal column could advance. As the hours passed and no news came back, he decided to order the companies of the 2/14th which had overcome the frontier posts to continue the advance and, for the present, not to send on Colonel Moten’s fully-motorised column, ready with its waggons loaded. It might be held up at a demolition and have to halt and return across the frontier again, with the confusion such an about-turn on a narrow road would cause. Therefore, early in the morning, the 2/14th advanced to the demolition with the tank troops of the squadron of the 6th Cavalry (as distinct from the carrier troops Mills was leading through the hills) and a section of anti-tank guns. When the leading troops reached the French crater they found that the face of the cliff had been blown off, making a gap in the road 100 feet long and 30 feet deep.31 At 9.45 Stevens arrived there in a carrier. About noon an anti-tank gun was man-handled across and then towed forward by a captured truck. A section of the 2/6th Field Company, under Lieutenant Harper,32 began to repair the road by blowing spoil down from the cliff above the crater, but it was not until 5 a.m. on the 9th that Moten’s vehicles were able to cross. Meanwhile a company of the 2/14th marched along the cratered road on foot.

In the hills on the right, the main body of MacDonald’s column had followed Potts’ force – its vanguard – through Bennt Jbail. A few miles south of Tibnine it had been delayed just before 9 a.m. while a deviation was cut round an 80-foot crater and a minefield cleared, a task which took the engineers four hours. (Potts’ advance-guard had man-handled their trucks past this crater.) About 5 o’clock in the afternoon the column reached the main coast road and joined the 2/14th. One company of the 2/14th, Captain Howden’s,33 which was with MacDonald’s column, took control of Tyre, where it was given “a great ovation by the populace”.34 Stevens, who had crossed the Iskandaroun crater on foot, was at the Tyre cross-roads when the 2/16th arrived.35 Meanwhile the mounted men of the Cheshire were making progress slowly through the precipitous country between Tibnine and Kafr Sir.

Thus, at the end of the day, Tyre had been occupied, and contact made with the enemy’s main line along the Litani; but it was evident that he

intended to fight hard and that there would be no swift occupation of Beirut by a force which had only to brush aside token resistance.

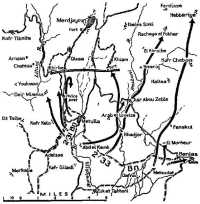

It will be recalled that Brigadier Cox’s brigade was divided into two columns for the first phase of its advance to Rayak. On the right was Moncolumn, commanded by Lieut-Colonel Monaghan and including chiefly his 2/33rd Battalion, of which he had taken command only a few days before, and detachments of cavalry, artillery and others. Its task was to cut the road from Kuneitra to prevent an enemy advance from that direction, advance into the Hasbaya area on the right and through Khiam on the left.

On Cox’s left was Portcolumn, commanded by Lieut-Colonel Porter of the 2/31st Battalion, and including in addition to that battalion “C” Squadron of the 6th Cavalry, a six-gun troop of the 2/6th Field Regiment, and four 2-pounders and two Solathum anti-tank guns of the 2/2nd Anti-Tank Regiment. The cavalry squadron had three light tanks and six machine-gun carriers. The task of this column was to capture a line from Merdjayoun Nabatiye et Tahta. This line was to form the base for a subsequent advance along “Route B”, one of two roads leading north to the vital Damascus-Beirut highway. Farther left a squadron of the Cheshire Yeomanry had the task of advancing through Blida and Adeisse to the main bridge over the Litani River about 5,000 yards south-west of Merdjayoun, and if possible establishing touch in the mountain barrier with the 21st Brigade at Habbouch.

At 2 o’clock Monaghan’s infantry moved forward in the darkness. The men carried two days’ rations, and wore steel helmets, shorts or slacks. Monaghan, in deference to the higher commanders’ opinion that the French might surrender the more easily if they saw men wearing felt hats, gave an order that “felt hats will be worn as often as the occasion permits”.

One company of the 2/33rd, Captain Bennett’s,36 had been given the task of moving across the frontier under cover of darkness, clambering through the Anti-Lebanon, occupying Ferdisse, cutting the road just west of it, and outflanking the defenders 12 miles to the north of his starting point at Metsudat. If Bennett’s company succeeded in accomplishing its march through the mountains, its efforts would not be felt until a later phase of the advance.

Major Wright’s37 company, which was given the task of capturing frontier posts from Banias to El Morheur and blowing up the bridge south-east of Banias as a precaution against a possible French flanking attack from Kuneitra, took Banias late in the morning and early in the afternoon reported to Monaghan that the bridge had been demolished and all was quiet.

The task of taking the frontier posts farther to the left, in the area of Rhadjar and Arab el Loueize, was given to Captain Cotton’s38 company, which left its assembly area at Abd el Kamh at 2 a.m., marched for half an hour after crossing the border without meeting opposition but, about 3 a.m., encountered a French post. After a mêlée in which one Australian (Lance-Corporal Webb39) was killed and three Frenchmen wounded, the remainder of the garrison – about twenty-five men, mostly Senegalese – surrendered.

Lieutenant Connor’s40 platoon of this company had been given the task of capturing intact the Jisr Abou Zeble, a bridge carrying the Banias–Merdjayoun road over the Hasbani, and of investigating other points where trouble might occur. He divided his platoon into four patrols each with a definite objective, and himself led the patrol that had to save the bridge. This patrol – Connor and four – reached the bridge at 4 a.m., drove off about twelve French infantry and some cavalry, and occupied the area. The bridge was undamaged. Although it had not been blown there was, however, a large crater in the road farther towards Khiam. Captain Ferguson’s41 company of this battalion moved forward under fire along the valley leading past Khiam on the south-east but was held by heavy fire from Khiam and Bmeriq.

At 11.30 a.m. Monaghan ordered Cotton’s company to capture Fort Khiam, which stood on a hill just south of the village itself, and about midday it attacked. The French held their fire and it was not until the Australians were about 300 yards away that they opened with field guns, mortars and small arms. Cotton’s men were well dispersed and moved on, suffering only one casualty, until they were only 50 yards from the square building which resembled the forts they had seen in American films about the French Foreign Legion. Thence the Australians poured fire at the French weapon posts until they had silenced the machine-gun in one of the bastions. Connor ran forward, cut his way through the barbed wire

round the fort and reached the wall where five men joined him. He climbed the wall, ran into a long barrack room, and fired at the occupants with his sub-machine-gun. A machine-gun crew shot at him from an opposite corner of the fort, whereupon he took refuge in the thick-walled bastion where he was joined by three men – Sergeant Sweetapple,42 Corporal Campbell43 and Private Wayte44 – who had followed him over the wall. Soon the little party, its ammunition now exhausted, was joined by a French non-commissioned officer and two medical orderlies who explained that they wished to join the de Gaullists. Until Connor’s voice was heard calling through a firing slit Cotton did not know what had happened to him and his men, except that they were in the fort and there was much noise therein. At length, with the help of the men outside, Connor’s party loosened the stonework of the wall and made a hole large enough to climb through, and they and the Frenchmen emerged, after having spent five hours in the fort. Cotton now decided to attack through the broken bastion with support from his mortars. He put some men through the hole in the wall, but the French – there were nearly 100 in the fort – fired vigorously from other parts of the building and Cotton decided to postpone the attack until next morning.

The 2/31st Battalion was to advance with three companies forward, two moving through Khirbe and the other to Kafr Tibnite past the Litani bridge (which a patrol under Sergeant Davis,45 having crossed the frontier the previous night, was to have saved from demolition). The main French positions covering Khirbe and the Chateau de Beaufort, a Crusader’s castle, were superbly situated from the defenders’ point of view; the Australian attack on the left was made up steep bare slopes, and on the right too there was little cover.

The leading Australian companies moved off from a taped start-line just north of Metulla a few minutes after 2 a.m. Captain Houston’s46 on the right found only one man in the police post on the frontier, and he in bed. In the darkness Houston’s men began moving along the ridge leading to Khirbe. A Free French liaison officer who was with them marched forward into the village holding a white flag. His fellow-countryman in command at Khirbe rejected a proposal that there should be no resistance and the envoy began to march back again. Before he had reached the Australian lines a shot fired from Khirbe hit and wounded him, and heavy fire from field guns, mortars and machine-guns was brought down on the leading Australians, now advancing through open fields. The Australians were only 200 yards from well-sited French pill-

boxes and mortar pits and any movement attracted heavy fire, but they continued to advance. Houston’s second-in-command, Lewington47, was wounded. One of the platoon commanders, Lieutenant Kelly,48 was killed leading his men forward to the enemy’s wire, and in the course of the morning eight of his men were killed or wounded. Soon it was apparent that any further attempt to edge forward would lead to disastrous casualties and the men sought cover. On the left Captain Byrne’s49 company advanced without incident, until a little after 4.30, when it too was pinned down. In the next few hours it lost thirteen or fourteen men and made no progress. Captain Brown’s50 company, advancing on the left towards Deir Mimess, was pinned down and Brown wounded. Thus the battalion was halted on open ground and casualties were mounting. Sharp artillery fire was brought down on the French positions by the 2/6th Field Regiment; while its shells were falling, parts of the Australian line were withdrawn to better cover but were still under searching fire. So far from the French defence being a thin shell on the frontier which the infantry could crack by a brisk night attack, it was a well-prepared position so far north of the frontier that the advancing Australians had not come in sight until light was breaking. The French had shrewdly held their fire until the attackers were almost on top of them and they were the more likely to inflict crippling losses.

Porter had planned to use his remaining company in an attack with artillery support at 10 a.m. but, now realising the strength of the enemy, he cancelled this project, having decided that the only hope of success lay in a deliberate attack supported by at least a regiment of artillery. About 10.30 the three light tanks of the 6th Cavalry51 in support of Porter’s column were led forward by Lieutenant Lapthonie.52 They silenced three French machine-gun posts but drew the fire of every French weapon within range. Lapthorne’s tank was hit and he was killed; a second tank was hit and disabled, its commander, Corporal Hicks,53 being fatally wounded; and the third tank (Sergeant Groves54), after driving forward and rescuing the wounded, withdrew. Byrne’s company then withdrew about 400 yards south along the Litani valley under heavy mortar fire; Houston’s remained until dusk and then was withdrawn after having hung on all day in the position it had reached at dawn. At the end of the day

little had been gained beyond finding the enemy’s defences, sampling his strength, and learning that hard fighting lay ahead. The battalion’s line ran east and west through the police post about two miles south of Khirbe.

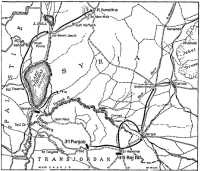

Meanwhile, on the extreme right flank, Brigadier Lloyd’s 5th Indian Brigade Group had moved across the frontier at 2 a.m. in four columns each in motor vehicles. The left column, comprising the 1/Royal Fusiliers, some field artillery (including the 9th Australian Battery) and other troops, passed the frontier just east of the Jordan at 4.15 a.m. and at 5 o’clock was at Kafr Naffakh where the infantry left their vehicles and advanced on foot towards Kuneitra. An hour later the advance-guard came under fire from Tel Abou Nida, a hill about two miles south-west of the town, and two emissaries – a British and a French officer – went forward to demand surrender and fire ceased. When these returned about 9.30 they said that they had received the impression that the younger officers wished to join the Free French but that the commander was determined to resist, and in any case would have to refer to General Dentz at Damascus. Later in the morning the envoys went forward again and a truce was agreed upon to enable the civilians to leave the town. It was evident that the French were trying to gain time; the invaders for their part took advantage of the delay to move their artillery observers forward, and the envoys discovered that the garrison consisted of a battalion of Senegalese and six armoured cars carrying light guns. At length a French officer came out and, like a herald in a mediaeval war, announced that hostilities would begin again at midday; and at that hour the guns opened fire. After a sharp concentration of artillery fire the infantry attacked and occupied Tel Abou Nida, with little opposition. Next morning it was discovered that the French had abandoned Kuneitra in the night, and the British troops entered it before dawn on the 9th, and took prisoner six “white” French machine-gunners.55

A platoon of the Rajputana Rifles under Captain Adam Murray56 was given the task of preventing the destruction of the railway viaduct at Chehab (the bridge which T. E. Lawrence tried without success to destroy in 1918 during Allenby’s offensive). Murray and a havildar crawled into the French sentry post in the darkness and shot the occupants while the remainder of the platoon rushed the guard post on the viaduct and saved the bridge, in which charges had been laid. Meanwhile a detached company of the Fusiliers had occupied Fiq with little opposition.

The third and fourth columns, one commanded by Lloyd himself and including the 3/1st Punjab and the other by Colonel Jones57 of the 4/6th Rajputana Rifles, had surrounded Deraa by 6 a.m. after having met little opposition. A flag of truce was sent into the town with a demand for

surrender. When the car carrying the party was fired on and hit by a shell which did not explode the envoys bravely continued on foot, but their demand for surrender was rejected. Thereupon at 7.30 the artillery opened fire. After a brief bombardment the two Indian battalions attacked and by 8.30 a.m. had occupied the town, with few casualties. The Rajputana with a battery of artillery then drove on towards Sheikh Meskine where they arrived late in the afternoon after having met some opposition from armoured cars and having been bombed by aircraft on the way. An attack on the town failed in the face of machine-gun and artillery fire but late in the afternoon, after a hard fight, high ground dominating the town from the west was occupied.

Early on the morning of 9th June, the Rajputana occupied Sheikh Meskine and Ezraa, which the enemy had abandoned during the night, and at 10 a.m. the Free French contingent passed through on its way to Damascus, leaving the Indian brigade to guard the desert flank, at Kuneitra, Sheikh Meskine and Ezraa, while they took up the pursuit. The Indian brigade had done its job swiftly and had captured thirty officers and some 300 men.58

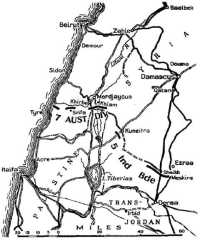

Dusk, 8th June

The French Army in Syria included all or part of seven regiments of regular infantry – the 6th Foreign Legion, 1st Moroccan, 16th Tunisian, 17th Senegalese, 22nd Algerian, 24th Colonial and 29th Algerian. There were 18 battalions in all, four of them belonging to the Foreign Legion.

There were two regiments of Chasseurs d’Afrique each armed with 45 twelve-ton tanks (“Renault 35”) armed with a 37-mm gun and a machine-gun; 150 locally-adapted armoured cars, some armed with 37-mm guns and some with machine-guns; 30 batteries of artillery. In addition there were eleven battalions of Levantine troops of doubtful reliability.

On the day the invasion opened a force of Spahis (Algerian troopers) and part of one of the Algerian regiments was deployed in the coastal sector and part of an Algerian regiment at Khirbe and Khiam. From Banias eastwards the 17th Senegalese Regiment and detachments of tanks and armoured cars were deployed. One company of the I/17th was driven from Banias. The II Battalion escaped with difficulty from Sheikh Meskine, having been reduced to 350 men. The III Battalion was at Kuneitra.

In a report to Berlin, Rahn, the German agent, declared, evidently with some pride, that just before the campaign began he had persuaded Dentz to transfer units from the Turkish frontier to the area south of Damascus, and at the same time to advance his main defensive line from Kiswe to a line Kuneitra–Soueida–Ezraa.

As soon as the invasion began General Catroux and the British Ambassador in Egypt (Sir Miles Lampson) each broadcast a declaration to the Syrian people. Catroux, speaking for de Gaulle, declared that the Free French intended to put an end to the mandate, to proclaim the people of Syria and the Lebanon free and independent, and to negotiate a treaty to ensure this independence. Lampson said that the British Government associated itself with this assurance of independence, and that, if the people of Syria and Lebanon joined the Allies, the blockade would be lifted, and they would enter into immediate relations with the sterling bloc, and thus gain “enormous and immediate advantages from the point of view of ... exports and imports”.

At the end of the first day, however, it seemed evident that Syria would have to be won by military not political operations. The French had shown that they would resist. Consequently, since the French deployed 18 good battalions of regulars against 9 good Australian, Indian and British battalions, and 6 Free French battalions of doubtful quality, the “armed political inroad” which Churchill had advocated was likely to develop into a hard-fought campaign.