Chapter 20: The French Counter-Attack

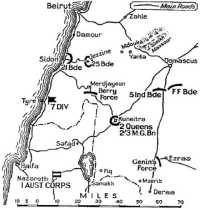

Two deep salients had now been driven into Syrian territory, the point of the eastern thrust being just south of Kiswe and 25 miles from Damascus, the blunt end of the western resting at Jezzine and Sidon, some 30 miles from Beirut. In the Merdjayoun sector, however, the advance had moved fewer than 10 miles beyond the frontier, and thus, between Jezzine and Damascus, the enemy still held a deep wedge of territory embracing the Litani Valley, Mount Hermon and its foothills.

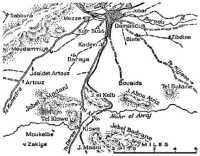

In the eastern sector the Vichy forces defending Damascus on the line of the Nahr el Awaj were in a very strong position. East of the road they had good cover for infantry and tanks in gardens and among houses behind which rose the steep boulder-strewn Jebel el Kelb and Jebel Abou Atriz on which the defenders were strongly sited. West of the road stood the Tel Kiswe, Tel Afair, and Jebel Madani, which commanded both the Deraa and the Kuneitra roads. Most of the undulating lower country was scattered with lava boulders which made it impossible for wheeled vehicles to leave the roads, and even impeded the movement of infantry, who cut their boots to pieces in a few hours of marching over the stones.

It will be recalled that, on the 14th Brigadier Lloyd had replaced the wounded General Legentilhomme in command of the British and Free French forces; Colonel Jones took over the Indian brigade. Lloyd’s plan of attack provided that the Indian brigade, plus the Free French battalion of marines, should attack west of the road before dawn on the 15th and occupy Moukelbe, Tel Kiswe and Kiswe village, whereupon, about 8 a.m., Colonel Casseau’s Free French brigade on the right was to advance and take Jebel Abou Atriz and Jebel Kelb.

It was believed that a Vichy Moroccan and Tunisian battalion were in and round Kiswe and two Foreign Legion battalions at Tel Kiswe and Moukelbe; thus the defenders outnumbered the attackers. In addition, conflicting sentiments were taking the heart out of the French mercenaries. Casseau had two Senegalese battalions and one Foreign Legion, and they now faced Senegalese and Foreign Legion battalions on the Vichy side. Their enthusiasm was visibly waning.

At 4.30 a.m. the 3/1st Punjab Battalion, with a company of the 1/Royal Fusiliers on its left, moved out to attack Kiswe village, carrying thirty wooden ladders with which to cross an anti-tank ditch 13 feet wide and about the same in depth. The guns of the 1st Field Regiment fired on Tel Kiswe and the enemy positions below it as the Indians advanced in the darkness, and, just before 6 a.m., the infantry crossed the wadi east of the village, and confused fighting began in the gardens and houses. The flanking company of the Indian battalion wheeled and helped to attack the village. By 8.30 the French were beaten. A determined attack in the darkness, though made without tanks across an area that offered little cover and against an enemy twice as strong, had succeeded. Luck played a part, because the attackers arrived just as the French were carrying out a relief and many weapons were loaded on lorries. At once the Rajputana began to move forward through the Punjab to attack Tel Kiswe. In little more than an hour the Rajputana, veterans of Keren, had taken the hill, and by 11.30 the French marines and the Fusiliers on the left had taken Moukelbe. Four Vichy French battalions had been forced out of their positions and the enemy flank had been broken.

On the right, however, the Free French attack failed. The Jebel el Kelb was taken, but flanking fire from the Abou Atriz prevented further progress, and, on the far right, Colonel Collet’s cavalrymen were held by artillery fire and tanks.

Meanwhile Lloyd received disturbing news from his rear. From Ezraa on the railway and near the road, 35 miles behind, came a report that on the afternoon of the 14th a column of two companies of Tunisians with ten armoured cars and some artillery had recaptured the town, driving out the two squadrons of the Transjordan Frontier Force, which took up a position across the Ezraa-Sheikh Meskine road. From Kuneitra came news that a strong force was advancing against that town from the north-east. About 2.30 a.m. on the 15th this force, including about ten armoured cars, had moved out from Sassa and driven off the company of the 1/Royal Fusiliers, which, with a few carriers and two armoured cars, as mentioned above, had been sent forward from Kuneitra and was in position four miles south of Sassa. During the day the enemy appeared to be sending south towards Kuneitra large bodies of infantry, tanks and cavalry. The Indian and Free French force had merely blocked the Kuneitra–Damascus road and advanced on Damascus along the circuitous route through Kiswe, leaving the Vichy French force astride the Kuneitra road to its own devices. It now appeared that this force, and their garrison in the Jebel Druse, which had also been by-passed, had sallied out to cut both roads behind the invader.

Promptly Lloyd sent a column consisting of two companies of Free French troops and some British guns under Colonel Genin towards Sheikh Meskine to hold that road.1 Confirmation that Kuneitra was seriously threatened was provided by a French deserter who declared that the

enemy intended to attack the town on the 15th using two battalions of infantry and a force of tanks.

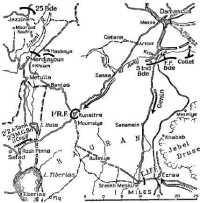

The thrust towards Kuneitra was part of a larger move. On 14th June most of the troops in the Merdjayoun area were combined under Lieut-Colonel Monaghan, his command including his own battalion (the 2/33rd), the 6th Australian Cavalry, the 10th Field Battery, and appropriate detachments of anti-tank artillery and engineers. In addition there were two units in the area

that were directly under General Lavarack’s command, namely the Scots Greys(Colonel Todd),

round Merdjayoun, and the 2/2nd Pioneers whose headquarters were near the Litani crossing with some of the companies at work elsewhere. Thus, for the time being, there were three separate forces in the Merdjayoun sector.

The war diary of the 7th Division states that on 14th June

GOC visited Lt-Col Monaghan [and] gave permission for Lt-Col Monaghan to use one coy in a small attack on Poste Christofini, east of Hasbaya, with the general intention of eventually seizing Hasbaya, which is ... rather a thorn in our side. Instructed Lt-Col Monaghan that his main function is to be to protect the right flank and rear of the Div during its advance north. ... In discussion with Lt-Col Monaghan G.O.C. agreed that his defence should not be passive, and that he should take every reasonable opportunity of harassing the enemy, always subject to the performance of his main task, the protection of the division’s right flank and rear.

In the event, however, Monaghan decided that day to leave only one company of his battalion forward of Khiam in a defensive role while, with the remaining three, he made a wide flanking advance over the foothills of Hermon into the Hasbaya area to cut the road behind the enemy’s leading forces – the task given to a single company on the first day of the invasion. Accordingly, on the night of the 14th–15th, the three companies set off through the mountains aimed respectively at Fort Christofini, Hebbariye, and Ferdisse. To guide them through the mountains they still had no better map than a sheet on a scale of one inch to 3.16 miles, in which the tangled area between Ibeles Saki and Hasbaya could be covered by a largish postage stamp.

Captain Bennett’s company was on familiar ground, having engaged in the similar enterprises during the opening days of the campaign. The

villagers now knew the Australians, and were friendly and helpful, and told them, as they passed through Rachaya el Fokhar, that the French were occupying Christofini, their objective. On the morning of the 15th Bennett established his company and its six mules near Hebbariye and sent patrols forward towards Christofini; these learnt from villagers that French cavalry had recently been using the picturesque fort there, groups of up to fifty at a time entering or leaving it. Bennett decided to probe forward during the night and attack next day – the 16th. (It seems probable that the French had actually abandoned the fort after it was shelled early on the 15th.)

Major Buttrose’s2 objective was Hebbariye. He set out with donkeys carrying the heavy weapons and ammunition, but the country was too steep for them, and the men themselves carried the loads, leaving the animals behind. At Rachaya el Fokhar an Arab who had lived in America offered to guide the men down the face of the cliff into Hebbariye and they arrived there at 11.30 a.m. and took up a position above the village. At 3 o’clock a friendly Arab told the Australians that the French knew where they were. Buttrose promptly moved his company to a new position below the village, a precaution soon justified by the fact that shells began falling in the area that he had abandoned. He could not reach Monaghan by wireless, but was in touch with Captain Cotton’s company. It had entered Ferdisse at 1 p.m., established touch with a patrol of the 6th Cavalry, and met no opposition until 3, when about a platoon began attacking from the direction of Hasbaya. Just at that time the French field guns began briskly shelling the British positions north of Merdjayoun, five miles to the west and far below.

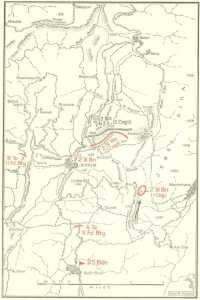

It will be recalled that, just north of Merdjayoun, the road turns south in a long narrow loop, climbs round the foot of the Balate Ridge and, turning north again, forks into Routes “A” and “B”. On the afternoon of the 15th when the French guns opened fire, the one remaining company of the 2/33rd was astride Route “A” at “Windy Corner”, under the command of Major Onslow of the 6th Cavalry, who had his two squadrons

in the same area. Between the road and Ibeles Saki were a platoon of machine-gunners (Lieutenant Clarke),3 two anti-tank guns and the 10th Field Battery, one of whose observers, Captain Brown,4 was on the slopes overlooking “Windy Corner” from the south, while the other (Captain Hodge5) overlooked Route “B” from a post on the south end of Balate Ridge. Hodge’s task was to support the Greys, who were astride the road some distance north of him. At 3 p.m. a rapid concentration of shells fell on Balate Ridge and round it, and, half an hour later, ten French tanks and about fifty cavalrymen appeared on Route “B” and deployed across the valley, while what appeared to be two companies of infantry assembled on the north end of Balate Ridge and set up machine-guns there. About 4.30 p.m. tanks attacked along both routes.6 As they came round “Windy Corner” they were hotly engaged by the anti-tank gunners and machine-gunners from the Ibeles Saki slopes. The gunners hit and disabled the leading tank and two others retired hastily round the corner and concentrated their fire on the machine-guns. At the same time French troops on “Col’s Ridge”,7 towering above the road on the northern side, opened heavy fire with mortars and machine-guns on gun positions of the 2/5th 200 feet below them and about 1,200 yards away.

On Route “B”, where the French were attacking in greater strength, supported by intense artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire, the Greys had now begun to withdraw down the road while the French tanks drove forward under hot bombardment from field and anti-tank guns. Eleven tanks attacked here. In quick succession four were put out of action; the remainder withdrew round the bend in the road. Meanwhile the enemy infantry were steadily advancing. At Route “A” two anti-tank guns were overrun; at Route “B” after a second duel with the enemy tanks the guns were withdrawn. The line to Hodge’s observation post was cut and a gunner sent back to find what was happening returned with the news that the Greys had gone back. Hodge and his team then withdrew covered by a troop of carriers which drove up the Debbine Valley to help him out.

There was now a general withdrawal along the whole front. On the right the tanks had been held thus far but the situation seemed dangerous. Monaghan instructed Onslow to coordinate the retirement of the troops in the forward area, and then went to Todd and suggested that the Greys should hold the high ground immediately north of Merdjayoun while Monaghan held Khiam and organised a counter-attack by his companies round Rachaya el Fokhar.

Attached to Todd’s force was Lieutenant Mayberry’s8 recently-arrived company of the 2/5th Battalion, which had two platoons in Merdjayoun and one in Nabatiye et Tahta. At 4.30 p.m. Todd ordered Mayberry to take up a defensive position on the Balate Ridge; but at 5.15, as the company was moving through the north edge of the town, Todd’s second-in-command told Mayberry that a squadron of the Staffordshire Yeomanry (attached to the Greys) was on that ridge, and ordered him to go through Debbine and on to the ridge west of the Balate to relieve a troop of Australian cavalry. However, this troop was met withdrawing south of Debbine, and Mayberry took up a defensive position north of that village.

The French continued to press the attack. At 7.15 p.m. about two companies of French infantry, following intense artillery and machine-gun fire, drove the squadron off the Balate Ridge and it withdrew to Merdjayoun. At 8 p.m. Mayberry who now, though not being pressed, was 700 yards north of the leading enemy troops, withdrew to Merdjayoun, where he was instructed to join a troop of the Greys, which, with two anti-tank guns, had orders to hold a road-block in the town until 2.45 a.m. on the 16th, while the regiment prepared and occupied defensive positions at Qleaa.

Early in the afternoon alarm had begun to spread among bodies of troops behind the forward positions. Reports were rapidly circulated that “the tanks had broken through”, and were in Merdjayoun and approaching Ibeles Saki. An Australian artillery officer saw a troop of the Greys return to their vehicle park and find their vehicles gone, whereupon a “wave of panic set in among some of the men and control, both mass and individual, was lost”. Four vehicles of the 2/5th Field Regiment “which had not received orders from the battery in the confusion, had got mixed up in a wild stampede through Metulla, and from there on every order received en route was to keep going and to get the roads clear, whilst on arrival at Rosh Pinna wild stories of tanks on the Metulla road were current and no vehicle was permitted to go forward. Eventually, after wandering for two days, during which Nazareth and Er Rama were visited to obtain orders, the little convoy of four trucks returned to the battery”.

At 4.45 it was decided to withdraw the field guns a troop at a time to the Qleaa road junction. One troop moved out safely through Merdjayoun to a position near Qleaa and continued firing. Drivers bringing up ammunition found a canteen at the Police Post abandoned and brought forward to the gun teams not only ammunition but cases of beer and cigarettes. However, at 5.15 p.m., when tanks were advancing astride Route “A” and French machine-guns were firing from the slopes northeast of Ibeles Saki, four guns were still in the battery position near Ibeles Saki. Infantrymen were moving past exclaiming that tanks were coming and, when a driver informed Major Humbley,9 the battery

commander, that tanks were on Route “A”, he decided that the guns must be withdrawn directly along the terraced wadi leading south to Khiam. Captain Evans10 was sent back to find a route, but, before he returned, the French troops were reported to be close, and Humbley ordered that the guns be taken out. Under machine-gun fire from Ibeles Saki the column of trucks and guns moved off and bumped their way along the wadi. Three vehicles, disabled by the rough going, were abandoned. Farther on, in an effort to avoid the difficult country, a leading driver began to make a detour, but it led the column to a series of three stone terraces where runways were furiously cut with picks and shovels and the guns them-selves hauled up the slope with winches. Lieutenant Gilhooley11 brought the rear gun into action and fired at the French on Col’s Knoll – the southern end of Col’s Ridge – over open sights. While most of the vehicles and guns were bunched on the second terrace, which was about 30 yards wide, a French bomber appeared at about 200 feet, banked and sped towards the crowd of struggling vehicles, but, as it began to dive, a British Bofors gun team 500 yards to the west opened fire and in a few rounds hit the aircraft which crashed, its bombs detonating with a roar.12 The gunners stopped work to give three cheers, then went back to their job of coaxing their vehicles up the last terrace wall. From the top of the hill the guns were driven back to the Khiam–Banias road junction. There Onslow told Humbley that the Bofors gun was still forward, and one gun was made ready for action while the Bofors gun and crew came in. At dusk the troop of field guns at Qleaa withdrew to Metulla.

Meanwhile at Merdjayoun, about 7.30 p.m., Captain Hodge had been assured by a major of the Greys that there were no longer any British troops on the ridge in front. The Greys were then moving fast through Merdjayoun.

Some little time earlier than this (said the diarist of the 2/5th Field Regiment) Lieutenant Nagle13 ... went forward on foot and found both British and Australian troops moving south through the town, but no one seemed to have any idea of what was happening except that the French were coming. He endeavoured to rally these troops telling them that the guns would support them but the majority seemed to have no other idea than to get back, although there was some talk of a plan to hold the east side of Merdjayoun. Eventually Nagle got to the south end of the town and held up a trooper carrying his Bren gun to the rear and on ordering him to stay or give up his gun the Bren was handed over without ado.

As frequently happens when alarm spreads throughout a force, particularly if caused by reports of tanks breaking through, stolid parties of infantry, cavalry and artillery were in forward positions unaware of the excitement behind them. At dusk the French attack had in fact halted,

nor could the tanks have continued to move in such country in the dark. The rearguard at Merdjayoun remained in position. Mayberry’s company, carriers of the 6th Cavalry and anti-tank guns of Major Rickard’s14 battery of the 2/2nd Anti-Tank Regiment, were still north of the town. At 2.30 a.m. Mayberry sent a patrol forward and it went 500 yards and saw no sign of the enemy. At 2.45 a.m., in accordance with its orders, the little rearguard abandoned Merdjayoun and moved back to Qleaa, where the squadron of the Staffordshire Yeomanry was in position on the right and a squadron of the Greys on the left. The Victorians took up a position in the centre, astride the road. It was not until 10.30 a.m. on the 16th that the first French tanks appeared, and then only two, one of which was hit and destroyed by the anti-tank guns; the other retreated.

Meanwhile, as part of the general withdrawal, Captain Peach’s15 company from “Windy Corner” had withdrawn to Khiam where it took up a position at the fort. Vickers gunners of the 6th Cavalry were on his left at the Banias-Merdjayoun road junction.

This double-pronged counter-attack, with its immediate threat to the communications of all the invading forces east of the Lebanons, transformed the situation. Few reserves were available to meet it. General Wilson called upon the 7th Australian Division to furnish anti-tank guns and ammunition to help the defence of Kuneitra and ordered the 2/Queen’s (the leading battalion of the 16th British Brigade) to Deraa. The reserves of the 7th Division consisted of the headquarters and two companies of the 2/3rd Machine Gun Battalion and the headquarters and one battery of the 2/2nd Anti-Tank Regiment at Er Rama. In addition the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion, which might be employed as infantry, was engaged in engineer work in the 7th Division’s area – one company on the road leading inland from Tyre, one with the 25th Brigade, and two on the Jezzine road.

With his two brigades Lavarack was responsible for 37 miles of front, measured through the forward posts. The counter-attack at Ezraa, Kuneitra and Merdjayoun offered a threat to the roads serving his right-hand brigade, because the enemy, already astride the communications of the force attacking towards Damascus, might move from Kuneitra either towards Banias or Rosh Pinna. He decided therefore to send the depleted 2/3rd Machine Gun Battalion, with the remaining anti-tank battery, to hold the crossing over the Jordan at Jisr Bennt Jacub (bridge of the daughters of Jacob) and to dispatch a proportion of the anti-tank and machine-guns north towards Metulla. The 2/2nd Pioneers were ordered to prepare the Litani bridge west of Merdjayoun for demolition and to protect the crossing. These decisions disposed of his only reserves; further reinforcement of the hard-pressed force at Merdjayoun could be achieved

only by transferring units already engaged at Jezzine or on the coast. Lavarack ordered that the 2/25th Battalion, the 2/5th Field Regiment (one of whose batteries was already with Monaghan) and a troop of the 2/6th should move from Jezzine to the Merdjayoun sector. This left only one battalion, the 2/31st, in Cox’s 25th Brigade at Jezzine, whereas at Merdjayoun a force considerably stronger than a brigade was now assembling. General Lavarack instructed Brigadier Berryman, his artillery commander, and the most experienced of his three brigadiers, to take command of all troops in the Merdjayoun sector west of the Litani and organise a defensive position facing east to cover the right rear of the 25th Brigade.

Orders to concentrate at the Litani crossing reached the scattered companies of the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion late on the night of the 15th–16th. One company, which had been repairing the road near Jerme, set out on foot about 11 p.m. and marched to the crossing, arriving just before dawn. The others began marching but were picked up by trucks. All were very weary next morning.

The order to guard the Jordan crossings reached Lieut-Colonel Blackburn16 of the 2/3rd Machine Gun at 6.30 p.m. on the 15th, and he hastened forward from Er Rama to reconnoitre, driving as fast as he could without lights over a twisting road crowded with vehicles. As he descended into the Jordan Valley a thick mist was enveloping road and river. He reached the bridge about midnight and found some British horsed cavalry guarding it. Half an hour later an officer arrived from Lavarack’s head-quarters with orders that Blackburn send a company to occupy a defensive position on one of the two main roads leading into Palestine. Blackburn drove along the valley with this company, saw it placed in position, and arrived back at the Jordan bridge at daylight. During the night two troops of the 2/2nd Anti-Tank Regiment arrived at the Jordan bridge. The little force busied itself preparing for the defence of the crossing, and the bridge was made ready for demolition.

Brigadier Berryman received his orders at Jezzine about midnight on the 15th. He sent Lieut-Colonel O’Brien of the 2/5th Field Regiment to the Merdjayoun sector to discover the situation there. He himself left Jezzine at 1 a.m. on the 16th, and at 6.30 a.m. met Lieut-Colonel Wellington17 of the 2/2nd Pioneers at the Litani crossing. Although his responsibility was confined to the area west of the Litani, Berryman took the initiative of ordering Wellington to send one company to take up a position on the ridge between Merdjayoun and Qleaa where the Greys were already in position; and he ordered that the Greys were to hold on.

Meanwhile, at 3.45 a.m. on the 16th, the French Force advancing south astride the Damascus road attacked Kuneitra, now held by the

Fusiliers less a company. The defenders estimated that more than 1,500 French troops with eleven tanks, ten armoured cars, and one or two field guns opposed the garrison – about 570 British infantry supported by one Italian 20-mm gun.18 By 6 a.m. the French tanks were cruising in the streets; the Breda gun was broken and the tanks were impervious to the anti-tank rifles and Molotov cocktails of the defending infantrymen, and overwhelmed one section post after another. At 11.30 a.m. the commanding officer collected the survivors in three stone houses.

The siege started, the enemy sniping strongly from tanks and houses (wrote the historian of the Royal Fusiliers). Spirited replies from Bren gunners reduced the numbers of enemy snipers ... the tanks roamed exactly where they liked and cruised round the battalion area shooting up the trenches, into doors and windows and at all trucks. ... Tank-hunting squads, mostly M.T. drivers, drew grenades from the battalion reserve SAA truck ... and continued their hopeless hunt. ...

At about this time Corporal Cotton, D.C.M., distinguished himself for the last time. He withdrew to the area of battalion headquarters at about 1230 hours. With Second Lieutenant Connal and one Fusilier, he carried back a Hotchkiss machine-gun he had captured a week before, together with 1,300 rounds. With this he continued in action for half an hour, but when the gun broke down he took an antitank rifle and went to attack the tanks single-handed. He drew their fire and was eventually killed by a round of high-explosive. ... There were many other gallant deeds that day. Towards the evening it looked as if the enemy infantry had withdrawn, as there was a lull. At 1820 hours a French officer approached in an armoured car, waving a white handkerchief, and came to battalion headquarters with a Fusilier prisoner. The officer explained that the battalion was surrounded by a vastly superior force of tanks and other armoured fighting vehicles. He hoped they would surrender now, as he hated shooting Englishmen. The Commanding Officer demanded half an hour to decide. After consultation with the second-in-command and Regimental Sergeant-Major, he decided that to give in was the only alternative to the massacre of the remainder of his men .... As he went over to speak to the French Commander, he saw eleven medium tanks behind the nearest group of houses. At 1900 hours he surrendered, with thirteen officers and 164 other ranks. ...19

Later in the evening the fourth rifle company of the battalion with a 25-pounder gun approached down the Sheikh Meskine road from Kiswe, but withdrew after the gun had fired all its ammunition.

Late in the afternoon of 16th June news had reached Blackburn that the Fusiliers were hard pressed and short of ammunition. He ordered Captain Kennedy20 to take a small force forward to Kuneitra in three trucks and with two anti-tank guns with the object of luring the French tanks out and destroying them.21 Soon after this party had set out Captain Houghton of the Cheshires, who had joined Blackburn as a liaison officer from General Wilson’s headquarters, issued instructions to Blackburn that he was to send forward two armoured cars, one company of

machine-gunners and two anti-tank guns to take 60,000 rounds of ammunition to the Kuneitra garrison. Houghton said he was speaking with the direct authority of General Wilson’s headquarters. Blackburn questioned these orders, saying that he had received no such orders from General Lavarack. Houghton was insistent that “his instructions were to be acted upon”. However, at 7.15, Captain Kennedy’s party returned, together with a patrol from the Yorkshire Dragoons and five men who had “escaped from Kuneitra”, and Blackburn suspended the move of the company towards Kuneitra. Towards midnight, however, the orders from Wilson’s headquarters were confirmed.

At Kiswe Lloyd did not allow the threat to his rear to upset his plan. He ordered the Indian brigade to advance on Jebel Madani, and they did so during the night of the 15th–16th. Soon after dawn on the 16th the Punjab had driven the French from the heights and could see the minarets of Damascus, nine miles away; the Rajputana, whose positions on Tel Kiswe had been taken over by a Free French battalion, had passed through and seized a line from Jdaidet Artouz along the Kuneitra road for two miles to the south. There the French marine battalion joined them, and in the afternoon they were heavily attacked by tanks and strafed by fighter aircraft, suffering heavy casualties.

By sending these battalions across to the Kuneitra road Lloyd had improved an extremely awkward situation. The French at Ezraa threatened the Deraa road along which he was operating and on the alternative road there were French troops between him and Kuneitra. By occupying Artouz, however, he had in his turn cut the road behind the French force at Kuneitra; and, in the afternoon, he received news (incorrect at that time) that Ezraa had been recaptured.

In the Merdjayoun sector on the 16th a brief but successful action was fought on the remote right flank. About 11 p.m. on the 15th a messenger reached Major Buttrose’s company of the 2/33rd at Hebbariye with news of the fight at Merdjayoun and orders from Colonel Monaghan to withdraw forthwith to a position astride the Bmeriq–Banias road. The messenger then set off to deliver a similar order to Captain Bennett at Fort Christofini. Buttrose’s company began to retire about midnight and by 6 a.m. on the 16th reached Rachaya el Fokhar just ahead of some squadrons of Vichy French Circassian cavalry which had advanced along the track leading into that village from the west. The Australians quickly took up a position round the village and poured fire into the French as they advanced towards them on foot, and did specially effective work with a 2-inch mortar. Meanwhile, about 7.30 a.m., the runner had reached Bennett with orders to withdraw. At 1 p.m., as he was moving his company along the track to Rachaya, Bennett came over the top of a hill and saw Buttrose’s fight in progress below him about 1,000 yards away. Some 200 French cavalrymen on the right, as he faced south, were then advancing up the terraces to attack Buttrose’s company.

Bennett decided to advance down the hill against the French flank. Lieutenant Copp’s platoon fixed bayonets and charged, then Marshall’s platoon charged on his right, while Dwyer’s men, farther to the right, established themselves overlooking the track along which the French would have to withdraw to Ferdisse. Copp’s platoon advanced among the French with Tommy guns and bayonets, and the enemy ran. Buttrose’s company joined in the chase, and his mortars and Dwyer’s Bren gunners poured fire into the fugitives. More than fifty French troops were killed. Both companies then took up defensive positions on the high ground west of Rachaya until, about 5 p.m., orders came from Monaghan to withdraw to Bmeriq. They did so and took up positions there that night. Thirty-two French cavalry horses, fine Arab stallions, were captured in the fight at Rachaya. The battalion used them to mount its messengers and for officers’ chargers.22

At Khiam fort early in the afternoon about a company of French troops attacked Peach’s company from both flanks. The French were not using tanks, but they attacked with vigour and Peach withdrew to a position 300 yards south of the fort. Here Cotton’s company, having marched back from Ferdisse, joined him, and both took up a position in a ravine, where they remained until, in the evening, Monaghan ordered them to fall back to a line about one mile and a half south of the fort.

Farther to the left the Greys and Lieutenant Mayberry’s company of the 2/5th were astride the road north of Qleaa, with a company of the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion on its way to reinforce them. There the enemy had been singularly inactive since 10.30 in the morning when the advance of his two tanks had been stopped.

Brigadier Berryman decided that the best way to check the enemy in the Khiam area would be to attack at Merdjayoun. On the 16th General Lavarack visited him, extended his command to include all the troops in the Merdjayoun area and approved his plan to attack Merdjayoun on the 17th, using the 2/2nd Pioneers and 2/25th Battalion. Meanwhile Berry-man allotted a lavish supply of ammunition to the guns intending to compensate for his lack of tanks by generous use of artillery. Berryman’s force now included three battalions, 22 field guns, the Scots Greys, and part of the 6th Cavalry.23 In fact the French counter-attack had, in less than twenty-four hours, attracted to this area the strongest force – though a motley one – on any of the three sectors west of the Damascus front.

The counter-attack fell also on the 25th Brigade at Jezzine, but less forcibly. The swift move along the tortuous mountain road had placed

this brigade on the flank of the 21st Brigade; and, on the morning of the 15th, patrols travelled along the Sidon-Jezzine road and found it clear of the enemy. Jezzine was a pleasant mountain town, lying in the centre of a tobacco-growing area. From it a good road wound north to the larger town of Beit ed Dine. To the east the lofty Jebel Niha towered between the Jezzine Valley and the valley of the Litani; whereas at Merdjayoun the brigade had been on the eastern slopes of the Lebanon, it was now on the western. From a point a few miles south of Jezzine a winding track led through the mountains to Machrhara, the terminus of a first-class road from the Zahle district, and thus provided a route by which the enemy might attempt to cut across the Australians’ slender line of communication. The road leading north was cut into the side of the range and dominated on the east by a series of hills which came to be known by their altitudes as marked on the map (in metres) – the “1199 Feature”, the “1284 Feature” and the “1332 Feature”. On the west the land fell away steeply, sometimes in sheer precipices into a deep gorge. Indeed, the line of advance offered every advantage to the defender. Cox’s force at Jezzine now comprised only the 2/31st Battalion and supporting detachments; its second battalion, the 2/25th, and some of the artillery having been recalled to reinforce the hard-pressed force at Merdjayoun. On the 15th the 2/31st had its leading companies forward on the high ground overlooking the town from the north, and astride the Machrhara road. The Cheshire was holding the road leading west to the coast.

Early on the 15th the infantry north of Jezzine saw trucks and horsed cavalry moving far ahead of them and reached the conclusion that the enemy was reorganising for a counter-attack. In the evening, a few hours after Cox had learnt of the counter-attack at Merdjayoun, Captain Thomson’s24 company, which was forward just north of Hill 1199, was attacked by what appeared to be a company and a half of infantry and a squadron of cavalry with three field guns. One French gun was dragged round the sharp bend of the road and fired over the heads of the men in the forward positions. Within ten minutes hard and accurate artillery fire was brought down on the French and they withdrew before their infantry had fired a shot.

At dawn next morning, the 16th, an enemy patrol approached along the road from Machrhara. Here Captain Houston’s company was well concealed astride the road at the foot of towering Mount Toumat. Houston was a cool and deliberate soldier, and Porter had instructed him, if he was attacked by a small enemy detachment, to hold his fire and capture a prisoner. He held his fire until the enemy column was only 200 yards away and then opened with a 2-pounder gun (of the 7th Anti-Tank Battery) and small arms. The gunners hit the leading armoured car, then the rear one and the one in the middle in quick succession. The crews ran, leaving behind the three wrecked cars (which thenceforward formed

a useful road-block) and two undamaged motor-cycles. Sergeant Sheppard25 and Private Murray Groundwater26 clambered over high ground and headed off and captured seven men. During the day an officer in a motorcar and another armoured car drove up to the road-block and were captured. At this stage Houston reported that he was “running out of parking space”.

A similar thrust, equally costly to the enemy, was made along the northern road later in the morning by French horsed cavalry which were caught under artillery and machine-gun fire and lost almost every man and horse. Throughout the day French artillery fired on Jezzine and the exposed mile of road to the south of it. Trucks carrying rations forward over the difficult mountain road had not arrived and some companies had had to eat their iron rations; a little food was requisitioned from the townspeople who gave it willingly and added two sheep ready-cooked.

At 3.15 a.m. on the 17th, Colonel Blackburn, in accordance with General Wilson’s order, dispatched one company of his machine-gunners, under Captain Gordon,27 two lightly-armoured cars belonging to the Palestine Police, and two anti-tank guns towards Kuneitra, 25 miles away. The plan was to move forward in three bounds on the last of which the machine-gunners would occupy a covering position while the armoured cars attempted to enter the town.

On the way Gordon met an officer of the Fusiliers, who told him that the French were holding Kuneitra strongly with a force of tanks, armoured cars, infantry, artillery and cavalry, and that they had outposts on the hills between the town and the little force advancing against them. At

6 a.m. another officer of the Fusiliers was met who said that his battalion had surrendered the previous evening at 6 p.m. to a force of “twenty-six tanks and armoured cars, a battery of artillery and 1,200 to 1,500 infantry and cavalry”. He added that “only 160 Fusiliers were left, seventeen of them officers”. Gordon decided that it was useless to attack such a force as the French evidently possessed with a company of machine-gunners, two armoured cars and two 2-pounder guns, and took up a defensive position astride the road on a ridge overlooking the town; thus at least he could block the route to Palestine. From an observation post on this eminence he saw three armoured fighting vehicles on the far side of the town. Some cavalry and two armoured fighting vehicles approached the machine-gunners’ position. Fire was opened by the machine-gunners with the object of drawing the tanks within effective range of the anti-tank guns; but immediately the French armoured fighting vehicles returned to the town, and the cavalry went to ground until the British armoured cars drove forward and scattered them. Three more tanks were then seen

in the town of Moumsiye opposite the Australian positions, and the machine-gunners saw artillery moving northward along the Sheikh Meskine-Kuneitra road, but could not determine whether they were enemy guns or not. When these guns were close to the village, however, the French opened fire on them – they were British. The British artillerymen went into action, the French tanks retired, and Gordon sent his armoured cars over to the newly-arrived guns to point out his position.

A 9 a.m. Gordon received a message that two battalions of infantry were coming out to support him. At 5 p.m. one battalion – the 2/Queen’s – arrived. Its commanding officer took charge of the force and planned an attack which began at 7 p.m., with the Australian machine-gunners and anti-tank gunners giving supporting fire from the left flank and the armoured cars following the infantry into the town. Using long range ammunition the machine-gunners fired on the French field guns and their forward defences. The infantry advanced and retook the town, losing only one man.

Kuneitra was a remarkable sight (wrote Blackburn afterwards). In 48 hours it had been successively 1. held by a British force, 2. attacked for nearly 24 hours, 3. held by the enemy for nearly 24 hours, 4. twice bombed by our aircraft, 5. shelled by our artillery, 6. attacked and recaptured by our forces. In the centre of the town was a French tank burning and nearly red hot. Along the streets and roads were overturned lorries, British and French, three smashed armoured cars, dead horses, piles of ammunition, papers, clothes, shells, guns, rifles and several ordinary cars riddled with bullets. In spite of this most of the shops were open. Australians – those off duty – were wandering along the streets buying. Locals were calmly cleaning up, sorting their belongings, shopping, and seeming indifferent to the war.

During the 16th and 17th the force at Sheikh Meskine had been hard pressed. At dawn on the 18th Colonel Genin attacked Ezraa with one company, but in the fight it was surprised by tanks and scattered and Genin was killed. Thereupon Major Hackett,28 a young Australian serving in the British regular army, led forward in trucks a force of fewer than 100 men – half a company of Senegalese, twelve Royal Fusiliers, two carriers and one anti-tank gun. These men made a determined assault, gallantly supported by their one small gun, manned by Corporal A. Clarke, and recaptured the town, taking 168 prisoners, three light guns, sixteen machine-guns, a mortar and a field gun. Hackett lost fourteen men; in the five days of fighting round Ezraa 71 Allied and probably about 120 enemy troops were killed or wounded.

Throughout the 17th June Lloyd’s Indian battalions pressed on, reaching Artouz, but the Free French on the Jebel el Kelb made no move. Lloyd decided that on the night of the 18th–19th he would make a surprise attack towards Mezze and cut the Damascus–Beirut road. Meanwhile his battalions would rest.

As mentioned above, Brigadier Berryman had decided, on the 17th, to recapture Merdjayoun. His plan29 was that, in the early morning, the 2/25th, which had reached Jerme early on the 16th and that afternoon had begun moving through the hills towards Merdjayoun, should march across the Litani and attack towards Merdjayoun from the north-west, and cut the road into Debbine. At dawn a company of the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion was to attack from the direction of Qleaa, supported by artillery and machine-gun fire, and a second Pioneer company was to follow through and exploit the success of the first.

The orders gave an imposing task to both battalions. The pioneer battalion, though a year old, had arrived in the Middle East only in May and had done no advanced training as an infantry unit, nor was it fully equipped or organised to fight as an infantry battalion. It had only one light automatic and one sub-machine-gun to a platoon, no mortars, no Intelligence section, and a signal section of only seven men. Now one of its companies had the task of attacking with patrols over country which (as the 25th Brigade had learnt) was easy to defend, and familiar to the French, and in which was deployed an enemy force possessing tanks and strong enough to have carried out a sweeping counter-attack. The advance by the 2/25th towards “the first b in Debbine” entailed a march, partly in the dark, over tangled mountain country, through the gorge and the swift-flowing stream of the Litani, to the steep ridge on which lay Merdjayoun.

The leading pioneer company (Captain Aitken30) was to move behind a barrage some 400 yards wide and lifting 100 yards every five minutes, and advance to a depth of 600 yards to the fort at the southern end of the town. The walls of the fort were about 15 feet high and so thick that 25-pounder shells did them little damage. The two forward platoons of the leading company followed the barrage closely on the left of the road. Soon they were under hot fire from machine-gunners and riflemen well concealed among the stone walls which criss-crossed the area, and machine-gunners firing through slits in the walls of the fort. They lost

men rapidly, but the survivors reached a point about 30 yards from the fort. A supporting company following 50 yards behind the first was pinned down. When it was light, both companies were lying out under searching fire from the slopes ahead of them. Soon French tanks emerged from Merdjayoun and captured thirty-eight of the survivors (the Pioneers had no effective anti-tank weapons), including Lieutenant Summons31 of the leading company, and Lieutenant Pemberton32 of the supporting company. Later Captain Aitken became a prisoner. For the remainder of that hot day those who were left lay behind such cover as they had been able to find and tried to drive the enemy outposts back to the fort. A captured anti-tank gun and a captured 81-mm mortar were brought forward to assist. At dusk the survivors of the leading companies straggled back and the line was stabilised about 800 yards from the fort, where the tanks could not advance without coming under fire from anti-tank guns of the 8th Anti-Tank Battery north of Qleaa. The two companies of Pioneers had lost 27 killed, 46 wounded, and 29 prisoners.

Meanwhile, at 10 p.m. on the 16th, the 2/25th had begun to move across the Litani valley. In single file they stumbled and slipped down the hillside, and in the early hours waded the swift-flowing river breast high and arrived wet and weary on the opposite bank. By dawn they had advanced some distance up a valley leading to the Merdjayoun plateau, but it was three hours after dawn before they reached the upper slopes. All chance of surprise had now been lost and the battalion was halted far short of its objective.

In the Jezzine area, as a result of the events of the 16th, Cox, who had moved his headquarters back to Kafr Houn, decided that he could defend Jezzine, but could not advance with so small a force. Soon after dawn on the 17th the enemy made it plain that he held the initiative. He launched a strong attack with apparently a whole battalion against Robson’s and Thomson’s companies on the heights east of the Beit ed Dine road. The attackers reached a copse south of Hill 1332 and were held there under heavy fire from Thomson’s company. Robson, on the right, about 8.30 a.m. led his men by a circuitous route until he was only 75 yards from the French position, and then charged with two of his platoons, their bayonets fixed, while the third gave covering fire. After a sharp hand-to-hand fight in which three Australians were killed and several wounded, the survivors of the French – two officers and sixty-five men, mostly Senegalese – surrendered. The prisoners were weary and dejected. They said that they had marched for four days before the attack and were very hungry; they were obviously fatigued and utterly weary of war. Never-theless, despite this set-back, the enemy continued to press forward all day and threatened to outflank the two companies by moving round them on

Soon after dawn, 17th June

the east. Pack animals carried their supplies over the rugged range. Robson’s company thrust forward and occupied Hill 1332 but was forced back to the copse by searching mortar fire and infantry attack, and eventually withdrew to a position well south of the hill. Thomson’s company held astride the road under constant mortar fire. Meanwhile Porter had hurried the company which had been on the Machrhara road (leaving one platoon and the anti-tank guns there) to Hill 1377 whence it harassed the attackers with machine-gun fire; and by 4 p.m., though the enemy continued to mortar and machine-gun the forward positions, his thrust had been halted with considerable loss. At the end of the hard day the Australians were weary, hungry and cold – they wore only shirts, and shorts or trousers. On Hill 1377 they collected food from the French dead in front of their positions, and their stretcher-bearers collected the enemy wounded; the Australians shared their water with these though very short of it themselves.

That night the French artillery shelled the Australian posts at frequent intervals, and when light came, enemy infantry were seen concentrating on the high ground east of the road and showing signs of renewing their costly attacks. Porter ordered Houston’s company to drive them off Hill 1332 whence they dominated the Australian positions. The advance began at 10.50 a.m. from a position near the copse, with artillery support. When his men were about 100 yards from the French on Hill 1332, Houston, in accordance with a prearranged plan, sent up a Very light signal to the artillery to cease fire, and charged. His line was only 50 yards from the French posts before they retaliated with withering machine-gun fire. Houston, a fine leader, Lieutenant Coakley33 and five others, were killed and twenty-two wounded.

This was an unhappy end to the successful repulse of the counter-attack in this sector, but the enemy had lost far more heavily than the Australians. Cox’s depleted force had held its ground. Some of the 2/31st’s success then and later was due to the fact that the battalion had been formed in England largely from artillery and other technical troops, and contained officers and men who were expert with the wireless telephones they had obtained there, and officers able competently to direct artillery fire. This produced particularly close cooperation with the field battery (Major Reddish34).

Late in the afternoon as this long fight was ending six bombers, escorted by fighters, dropped about twenty bombs on Jezzine. Several hit the three-storeyed Hotel Egypt where the 2/31st’s ration store and kitchen were installed. Forty men were buried in the wreckage, of whom seventeen, including three company quartermaster-sergeants who were collecting rations, died; ten others were sent to hospital. The terrified townspeople

fled to refuge in caves in the surrounding hills. Some were carried away to other villages in army vehicles, and the force had to find men to police the town against the Arabs who crowded in from the outlying areas looking for loot.

What had been the objectives of the French counter-attacks? On the 13th General de Verdilhac had ordered that offensive reconnaissance be made in front of the Nahr el Awaj positions. To that end a patrol comprising an armoured car troop and a lorried troop of the 1st Spahis was ordered to move out from Sassa. It reached the neighbourhood of Kuneitra where it was fired on and withdrew. On the 14th, however, Verdilhac decided to attempt counter-attacks on a larger scale with the object of so disorganising the invading army that it would be possible to divert some of his forces to meet an expected British attack from Iraq. Verdilhac had now used thirteen of his eighteen regular battalions; others were dispersed on defensive tasks; his reserves were almost exhausted. A column, including the 7th Chasseurs d’Afrique, a company of Senegalese and a few guns, was ordered to take Kuneitra, if weakly held, and advance to Banias and Jisr Bennt Jacub; a weaker patrol was to advance on Sanamein; and a third, with armoured cars and lorried infantry, to advance from Hijjane to take Ezraa and Sheikh Meskine and cut the Deraa-Damascus road. At this stage three battalions – III/29th Algerian, V/1st Moroccan and I/17th Senegalese – were deployed on the Nahr el Awaj protecting Damascus.

At Kuneitra the mobile column (under Colonel Lecoulteux) after fierce fighting took the town, with 470 prisoners, including 18 officers. However, because of the failure of the column which was to take Sanamein (which was found “strongly held”), Colonel Keime, in command of all the raiding columns, ordered Lecoulteux to withdraw his main force to Sassa, leaving a detachment of one company of infantry and some armoured cars to hold Kuneitra until heavily attacked, when it was to retire. Meanwhile, as a result of Lloyd’s continued attack, and the loss of Kiswe, the threat to Damascus became so pressing that Verdilhac reinforced the area with two fresh battalions – I/29th and III/24th Colonial. He replaced the commanders of two of the three battalions at Kiswe and appointed Colonel Keime to replace General Delhomme in command of the whole South Syrian Force. Keime placed his newly-arrived battalions in the Artouz-Mezze area.

At Merdjayoun the counter-attack was made by three African battalions (evidently the I/22nd Algerian, II/29th Algerian and II/16th Tunisian), with some twenty tanks. Two of the battalions attacked from an east-west line astride Routes “A” and “B” and the third moved along the axis of the advance in their rear. Cavalry guarded the eastern flank round Hasbaya. The final objective was a line just south of Khirbe and Fort Khiam, whence the eastern battalion was to exploit towards Banias, the west towards Metulla. By the 21st the III/6th Foreign Legion was also in this area.

The advance to Jezzine attracted enemy reinforcements from the Damascus area: the II/17th Senegalese Battalion and companies of the I/6th Foreign Legion. At the end of this phase there appear to have been two battalions in the Jebel Druse, five in the Damascus area, three at Merdjayoun, one and a half about Jezzine, and five or six in the coastal sector.

The French counter-attack on the inland sectors had the indirect effect of halting the 21st Brigade on the coast: on the 17th June General Lavarack ordered Brigadier Stevens to stand fast and adopt an “aggressive defence” until the position at Merdjayoun had been cleared up. That evening Brigadier Cox informed General Lavarack that he was opposed by three French battalions and a half – an over-estimate – and, if he did not receive reinforcements, would have to withdraw. General Lavarack ordered him to hold on; Brigadier Stevens was told not to advance farther

until the position of the 25th Brigade had been stabilised; later that night Stevens was instructed to reinforce Jezzine with his 2/14th Battalion and detachments of artillery. At 1 a.m. the following morning Lavarack informed General Wilson of these steps and asked that he be given the 2/3rd and 2/5th Battalions. Wilson allotted him instead the 2/King’s Own of the 16th British Brigade. Lavarack ordered it to join the 21st Brigade to replace the 2/14th. The 2/3rd and 2/5th, as mentioned above, had been included in the order of battle of the 7th Division from the outset, and one company of the 2/5th had fought at Merdjayoun. The 2/King’s Own would be the second battalion of the 16th British Brigade to arrive forward, the first having been the 2/Queen’s which recaptured Kuneitra.

In the middle days of June the sea and air battle off the Syrian coast became more intense. On the 15th French aircraft bombed and severely damaged the British destroyers Isis and Ilex. Next day aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm, based in Cyprus, sank the French destroyer Le Chevalier Paul, believed to be running arms into Syria. On the 17th a French sloop appeared off Sidon, came close inshore and shelled and machine-gunned the gun positions of the 2/4th Field Regiment north of that town. In accordance with orders not to disclose gun positions to enemy warships, the troops took cover until the sloop began to move out to sea. Then seventeen guns opened fire at about 4,000 yards and maintained it until the ship was out of range, achieving some direct hits.

The plan of campaign had provided that when the attacking force reached the Beirut-Damascus road – the first and main objective – General Lavarack would hand over his division to General Allen, take command of I Australian Corps, and assume control of the operations in Syria and the Lebanon. After ten days of fighting the objective had not been reached, but there were good reasons for transferring command of the forces in the field to a leader who would have a smaller sphere of responsibility than General Wilson had. Wilson’s main headquarters were in Jerusalem (at the King David Hotel), and his area included all Palestine and Transjordan. At 9 a.m. on the 18th Lavarack handed over the 7th Division to Allen, and took over I Australian Corps Headquarters,

which had been established at Nazareth since the beginning of the cam-paign awaiting the order to assume command.

All troops in Syria except “Habforce”, a column which, on the 13th had been ordered to advance into Syria from Iraq, thus came under Lavarack’s command – namely the 7th Australian Division, the 5th Indian Brigade, the 1st Free French Division, and the lines of communication. At a conference that morning Wilson instructed Lavarack to regard the operations against Damascus as of secondary importance and concentrate his main effort against Beirut. He ordered that the 16th British Brigade, which had one battalion at Kuneitra, one at Rosh Pinna, and the third on its way to the coastal sector, be incorporated in Allen’s division, which was to prepare for an advance on Beirut. That evening General Wilson broadcast a message to General Dentz calling on him to declare Damascus an open city and withdraw his troops from it; but without result.

General Lavarack and his staff thus took over a problematical situation. In three sectors the French were either attacking or else had soundly defeated recent Allied attacks; and on the coast the advancing column had been ordered to halt. The 5th Indian Brigade had lost heavily and the Free French troops were in low spirits. Practically all reserves had been committed, and two hard-pressed sectors had been reinforced at the expense of others. However, by collecting the scattered units of the 16th British Brigade, a reinforcement could be provided for the Sidon-Jezzine salient, on which Wilson ordered the new field commander to concentrate his main strength – a return to the original plan. That afternoon General Lavarack informed General Allen that the Merdjayoun sector would be placed under the command on Major-General Evetts, now leading the 6th British Division, so that Allen could concentrate the 7th Australian Division west of the range for a decisive thrust towards Beirut, against which the main effort would now be directed.