Chapter 4: To Malaya

In the circumstances revealed by the Singapore conference report, and with the danger of war in the Pacific steadily growing, Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham1 arrived in Singapore on 14th November 1940 as Commander-in-Chief in the Far East. He had been appointed, with Australia’s concurrence, a few days before the conference began.

The new leader would command the land and air forces throughout the Far East. Such a charter was rare in British experience. The fact that the task was assigned to an air leader no doubt reflected the importance of air power in the command; but the British Cabinet had chosen an officer of great seniority who had served as both soldier and airman, and therefore might be more acceptable to both Services. Brooke-Popham, aged 62, was, however, relatively old for an active command of such extent.2 Three years before the war he had retired from the post of Inspector-General of the Air Force to become Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Kenya.

From 1898 to 1912 Brooke-Popham had been an infantry officer. Then as a captain he had joined the Air Battalion, Royal Engineers – the beginning of a British military air force, later to become the Royal Flying Corps and later still the Royal Air Force. He gained distinction as an air officer in the war of 1914-18 and when it ended was one of its senior leaders. In the following nineteen years he held a series of high appointments, including command of the RAF Staff College and the Imperial Defence College (school of future senior commanders of all three Services). A tall, spare man, of distinguished appearance, he had stepped from his vice-regal position to rejoin the Royal Air Force in 1939.

On the British Government’s current list of priorities, defence of the United Kingdom came first, on the principle that on this all else depended; then the struggle in the Middle East. Provision for resistance to a Japanese assault was next.3 There was thus little prospect that the deficiencies, especially of aircraft, to which the Singapore conference had drawn attention, would soon be remedied. Nevertheless, Brooke-Popham had been told by Mr Churchill that Britain would hold Singapore no matter what happened, and that there would be a continuous and steady flow of men and munitions to the areas of his command.

Brooke-Popham had been made responsible to the United Kingdom Chiefs of Staff for the higher direction and control, and general direction of training, of all British land and air forces in Malaya (which for the

purpose would include Sarawak and North Borneo) and in Burma and Hong Kong. He was responsible also for the coordination of plans for the defence of these territories. He was similarly responsible for the British air forces in Ceylon, and squadrons which it was proposed to station in the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal for ocean reconnaissance. The General Officers Commanding in Malaya, Burma, and Hong Kong, and the Air Officer Commanding in the Far East, were placed under his command. Despite these widespread responsibilities, his staff originally comprised only eight officers.4 Civil administration, although obviously it must play an essential part in the defence of Malaya, lay outside his jurisdiction; so also did the naval forces, despite the fact that the approaches to his areas of responsibility were largely by sea.

The directive given to Brooke-Popham specified that he should deal chiefly with matters of major military policy and strategy, and should not assume administrative or financial responsibilities, or the normal day-to-day functions exercised by the army and air commanders. This, while perhaps intended to help him concentrate on the broader issues, tended to isolate him from those “normal day-to-day functions” which are underlying realities of planning at even the highest level. Indeed, as he was passing through Cairo on his way to Singapore, General Wavell,5 the wise and learned Commander-in-Chief of the army in the Middle East, told him that he considered a general headquarters based on such a directive was impracticable.

Brooke-Popham opened his General Headquarters, Far East, at Singapore on 18th November. A primary task was to ensure the security of the costly naval base at Singapore, which occupied a large area of the northernmost part of Singapore Island, facing Johore Strait and the Malay state of Johore, on the mainland of Malaya. The two entrances from the sea to the strait, from the south-west and east of the island respectively, were covered by big coastal guns. Near the western end of the naval base area was a long, heavily-constructed causeway which formed the sole link with the mainland for surface traffic. After delays caused chiefly by political and financial difficulties, the base had been officially opened in February 1938. It was then hailed as, for example, “the Gibraltar of the East ... the gateway to the Orient ... the bastion of British might”.6 A correspondent gaily reported that there were “more guns on Singapore Island than plums in a Christmas pudding”.7 But in the fifteen years since the plan for this base had been introduced to the British Parliament, the range of aircraft had been increasing, to an extent which challenged the strategy on which the plan was founded.

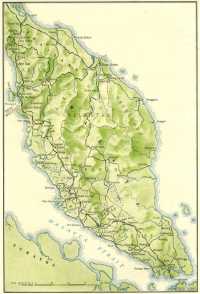

Brooke-Popham’s problems were increased by inter-Service jealousies which, in his view, caused lack of cooperation and a tendency by one Service to go ahead with its plans, particularly for airfields, with scant regard for how they might fit in with defence requirements as a whole. Moreover, the working relationship between the civil and military authorities left a great deal to be desired in the event of swift and effective military action being necessary. The system of government of British Malaya was of a type which tended to develop in Asian and African areas where a European Power had established a trading post and thence extended its influence by a variety of encroachments and compromises. In 1941 Malaya comprised (a) the Straits Settlements, a Crown Colony including Singapore, Malacca, Penang and some other areas, (b) the Federated Malay States, whose sultans still sat on their thrones but which were largely governed by a central administration at Kuala Lumpur, and (c) six “unfederated” States ruled by sultans, beside each of whom was a British adviser with an administrative staff which was almost completely British at the higher levels.8 The most important of these States was Johore, whose capital Johore Bahru lay at the northern end of the causeway connecting Singapore Island with the mainland. The sultan9 of this State was a shrewd and urbane potentate and in 1941 had been on the throne since 1895, when he was 21. The Governor of the Straits Settlements was also High Commissioner for the federated and unfederated States and thus the coordinating authority for the whole area. This organisation with its complex of “influences” and pressures, political, administrative, commercial and personal, had for long served its purpose; but the closest possible collaboration was necessary to adapt it to the demands of war.

In practice it proved difficult, especially because of Malaya’s importance as a source of strategic raw materials and of economic strength, to reconcile the aims of the military authorities, who placed defence requirements first, and of the civil authorities, whose concern continued to be primarily political and economic. Brooke-Popham considered the view of the Colonial Office to be that rubber and tin output was of greater importance than the training of the forces in Malaya; a belief which he based largely upon a telegram from London to the Governor, Sir Shenton Thomas,10 asserting that “the ultimate criterion for exemption (from military service) should be not what the General Officer Commanding considers practicable, but what you consider essential to maintain the necessary production and efficient labour management”.11

As failure to hold Malaya would involve not only loss of these resources, but other and far greater consequences, the need for some over-riding authority for defence purposes was strongly urged, but without avail. The circumstances tended therefore to a pull devil, pull baker relationship between the civil and military authorities.

Lack of a sense of urgency, arising from factors such as a long period of immunity from war in the area, the enervating climate, and a feeling of superiority towards Japan despite the shortcomings of Britain’s Far Eastern defences also had a marked effect on the conduct of affairs. The wide gulf between the standard of living of the Europeans and that of the mass of the Asian population of Malaya separated them socially as well as economically, and in general prevented sympathetic reciprocal understanding of each other’s viewpoints. This situation was accepted fatalistically by the Asians as a whole; but it produced extremes of hardships on one hand, and on the other an artificial existence which tended to restrict the Europeans’ outlook and sense of reality. There were nevertheless many Asians and Europeans to whom this did not apply, and among whom mutual understanding was possible.

Malaya lacked a balanced economy, and a large proportion of the Asian population’s staple diet of rice had to be imported. Rice was “a constant source of anxiety” in maintaining the six months’ supply of food which had been laid down as a minimum military requirement.12 Vast though Malaya’s resources were as applied to the task of feeding distant factories, secondary industries that might have been turned to local production of munitions were almost wholly lacking. On the whole, however, Malaya rated as a prosperous and well-administered territory by standards of comparison at the time. British rule was generally accepted, and its corollary, military protection, was taken for granted.

Within a few weeks of Brooke-Popham’s arrival two additional brigades (the 6th and 8th) arrived from India, and two British battalions (the 2/East Surrey and 1/Seaforth Highlanders) arrived from Shanghai. The military garrison then included 17 battalions of which six (one a machine-gun battalion) were British, ten were Indian, and one was Malay. In addition the headquarters of the 11th Indian Division (Major-General Murray-Lyon13) had reached Malaya. There was thus infantry enough to form two divisions; but the only mobile artillery was one mountain regiment, whereas two divisions should have possessed six artillery regiments between them, not counting anti-tank units.

The air force included two squadrons of Blenheim I bombers, two squadrons of obsolescent Vildebeeste torpedo-bombers, one squadron of flying-boats (four craft) and the three Australian squadrons (two with Hudsons, the third with Wirraways). Since September 1939, one RAF squadron had departed and the three Australian squadrons had arrived.

Only 48 of the 88 first-line aircraft – the Blenheims and Hudsons – could be counted as modern at the time, and the range of the Blenheims was inadequate.

Brooke-Popham’s other territorial responsibilities were strung out along a 2,500-mile line from Colombo to Hong Kong. The doctrine of “Burma for the Burmese”, demanding removal of British control, had taken a firm grip in Burma, and there was antipathy by Burmese to Indians, principally because of the hold which Indians had obtained on much of Burma’s best agricultural land. Thus the internal situation, as well as the weakness of the forces stationed there (a few battalions mostly of Burman troops and virtually no air force), complicated the problem of Burma’s defence. Brooke-Popham formed the opinion that Burma’s safety depended largely upon holding Malaya, and that defence of Malaya must have priority, in view particularly of the weakness of the available air forces throughout his command.

Hong Kong, a British colony situated partly on the island of Hong Kong and partly on the mainland of China, with a population of some 1,500,000 people, “was regarded officially as an undesirable military commitment, or else as an outpost to be held as long as possible”. Brooke-Popham held that it was very valuable to China as a port of access, and that had the Chinese “not been convinced of our determination to stand and fight for its defence, and been taken into our confidence and given opportunities to inspect the defences and discuss plans for defence, the effect on their war effort would in all probability have been serious. A withdrawal of the troops in Hong Kong coinciding with the closing of the Burma Road might have had a marked effect on Chinese determination to fight on. ...” He held also that “had we demilitarised Hong Kong, or announced our intention of not defending it, the Americans might have adopted a similar policy with regard to the Philippines. In this case, they might have ceased to take direct interest in the Far East, and confined themselves to the eastern half of the Pacific.”14

A rapid increase of population caused by a large and continuing influx of Chinese was one of the main local problems affecting the defence of Hong Kong. It placed an abnormal strain on the provisioning and other essential services of the crowded little colony, and made adequate security measures practically impossible. From his broad strategical viewpoint Mr Churchill considered at this time that there was not the slightest chance of holding or relieving the colony in the event of attack by Japan.

Brooke-Popham supported the proposal, already mentioned, that if the Japanese entered Thailand the British should occupy the southern part of the Kra Isthmus. He urged that efforts should be made to encourage the United States to show a firm front to Japan. One sequel to the arrival in London in December of his first appreciation was the appointment of Major-General Dennys15 as military attaché at Chungking with the task

of organising a British military mission (“204 Mission”) should war break out between Britain and Japan.16

Meanwhile the Chiefs of Staff in London had examined the report of the October conference at Singapore, and on 8th January replied that although they considered that the conference’s estimate that 582 first-line aircraft were required was the ideal, nevertheless experience indicated that their own estimate of 336 would give a fair degree of security; and in any event no more could be provided before the end of 1941. They would try to form five fighter squadrons for the Far East during the year. (There were then no modern fighters there.) They accepted the conference’s estimate of 26 battalions (including three for Borneo) and indicated that this total would be reached by June. Mr Churchill, however, was unwilling to agree to any diversion of forces to the Far East and on 13th January the Chiefs of Staff received from him a minute in which he said that

the political situation in the Far East does not seem to require, and the strength of our Air Force by no means warrants, the maintenance of such large forces in the Far East at this time.

Five days earlier Mr Churchill and the Chiefs of Staff had decided that “in view of the probability of an early German advance into Greece through Bulgaria it was of the first importance, from the political point of view, that we should do everything possible, by hook or by crook, to send at once to Greece the fullest support within our power”.17 There was little to offer the Greeks; and Churchill evidently considered that there was nothing at all for Singapore.

–:–

Meanwhile some reinforcement of the garrison of Singapore was due soon to arrive from another quarter. At the beginning of December, the Australian Government’s offer to send a brigade group to Malaya if necessary was gratefully accepted by Mr Churchill, who added that the Australian force would be relieved in May 1941 by the equivalent of a division from India. Churchill said to the Australian Government that he believed the danger of Japan going to war with the British Empire was definitely less than it was in June after the collapse of France.

The naval and military successes in the Mediterranean and our growing advantage there by land, sea, and air will not be lost upon Japan (he continued). It is quite impossible for our Fleet to leave the Mediterranean at the present juncture without throwing away irretrievably all that has been gained there and all the prospects of the future. On the other hand, with every weakening of the Italian naval power the mobility of our Mediterranean Fleet becomes potentially greater, and should the Italian Fleet be knocked out as a factor, and Italy herself broken as a combatant, as she may be, we could send strong naval forces to Singapore without suffering any serious disadvantage. We must try to bear our Eastern anxieties patiently and doggedly until this result is achieved, it always being understood that if Australia is seriously threatened by invasion we should not hesitate to compromise

or sacrifice the Mediterranean position for the sake of our kith and kin. ...

I am also persuaded that if Japan should enter the war the United States will come in on our side, which will put the naval boot very much on the other leg, and be a deliverance from many perils.

... With the ever-changing situation it is difficult to commit ourselves to the precise number of aircraft which we can make available for Singapore, and we certainly could not spare the flying-boats to lie about idle there on the remote chance of a Japanese attack when they ought to be playing their part in the deadly struggle on the North-western Approaches. Broadly speaking, our policy is to build up as large as possible a Fleet, Army, and Air Force in the Middle East, and keep this in a fluid condition, either to prosecute war in Libya, Greece, or presently Thrace, or reinforce Singapore should the Japanese attitude change for the worse. In this way dispersion of forces will be avoided and victory will give its own far-reaching protections in many directions. ...18

Arrangements were made in Australia for the 22nd Infantry Brigade and attached troops, 5,850 all ranks, to embark for Malaya early in February preceded by a small advanced party. The Chief of the General Staff (General Sturdee) visited Malaya in December on his way back from a visit to the Middle East, and inspected the areas and accommodation that the AIF was to occupy.

On 27th December a vessel with a Japanese name, and showing a Japanese flag, shelled and wrecked the phosphate loading plant on Nauru Island, north-east of the Solomon Islands and just south of the Equator. The island, a prolific source of phosphates of particular importance to Australia, was among the German possessions in the Pacific occupied by Australian forces in 1914. Placed by the Versailles Treaty under mandate to Great Britain, Australia, and New Zealand, it had then been continuously administered by Australia. The raider, after she had signalled that she was about to fire, hoisted a German flag. It later transpired that she was the Komet, which with the Orion, another German raider, had sunk near Nauru early in the month five ships engaged in the phosphate trade.

–:–

As 1941 dawned, America intensified her diplomatic and material assistance to the Allies. “We were convinced,” wrote the American Secretary of State subsequently, “that an Allied victory was possible, and we were determined to do everything we could to bring it about, short of actually sending an expeditionary force to Europe or the Orient. We were especially convinced that an Axis victory would present a mortal danger to the United States. ... We were acting no longer under the precepts of neutrality, but under those of self-defense.”19

American policy crystallised in a directive from President Roosevelt in mid-January 1941. At informal talks in London in August 1940 between British and American officers, the United Kingdom Chiefs of Staff had made it clear that despite the importance of Malaya they were not prepared to support its defence at the cost of security in the Atlantic and

the Mediterranean. Roosevelt agreed at the end of November to further Anglo-American staff talks being held at Washington; and in preparation for these, steps were taken to plot a clear course for the United States to follow. In the resultant directive, which followed a White House conference between the President and his Secretaries of State (Mr Cordell Hull), War (Mr Henry L. Stimson), Navy (Mr Franklin Knox), Chief of Naval Operations (Admiral Stark), and Chief of Staff (General Marshall) Roosevelt laid it down that

The United States would stand on the defensive in the Pacific with the fleet based on Hawaii; the Commander of the Asiatic Fleet would have discretionary authority as to how long he could remain based in the Philippines and as to his direction of withdrawal – to the East or to Singapore; there would be no naval reinforcement of the Philippines; the Navy should have under consideration the possibility of bombing attacks against Japanese cities; it should be prepared to convoy shipping in the Atlantic to England, and to maintain a patrol offshore from Maine to the Virginia Capes.

The Army should not be committed to any aggressive action until it was fully prepared to undertake it; the United States military course must be very conservative until her strength had developed; it was assumed that she could provide forces sufficiently trained to assist to a moderate degree in backing up friendly Latin-American governments against Nazi-inspired “fifth column” movements.

The United States should make every effort to go on supplying material to Great Britain, primarily to disappoint what Roosevelt thought would be Herr Hitler’s principal objective in involving the United States in war at this time; “and also to buck up England”20

For the purpose of the Washington staff talks, which it was emphasised must be held in the utmost secrecy, the British delegation wore civilian clothes and were known as “technical advisers to the British Purchasing Commission”. The talks, which commenced at the end of January and lasted until late in March, resulted in a plan for the grand strategy of Anglo-American cooperation, and embodied the “Beat Hitler first” principle (the principle that, in a war against both Germany and Japan, the aim should be to concentrate first against Germany and go on the defensive in the Pacific and Far East). Provision was made for continuing exchange of information and coordination of plans. In sanctioning such measures, Roosevelt took a big political risk, for

It is an ironic fact that in all probability no great damage would have been done had the details of these plans fallen into the hands of the Germans and the Japanese; whereas, had they fallen into the hands of the Congress and the press, American preparation for war might have been well nigh wrecked and ruined. ...21

Canada, Australia22 and New Zealand were represented at meetings of the British delegates but not at the joint meetings.23 Despite the growing

partnership between the United States and Britain, the United States Joint Planning Committee gave warning in a memorandum preparatory to the talks that “it is to be expected that proposals of the British representatives will have been drawn up with chief regard for the support of the British Commonwealth. Never absent from British minds are their post-war interests, commercial and military. We should likewise safeguard our eventual interests. ...”24

Britain’s critical plight in American eyes at the time was indicated by an accompanying statement that the conversations should include “the probable situations that might arise from the loss of the British Isles”; and the “Beat Hitler first” policy was maintained in the outcome of the talks as basic to the common aim. It was agreed that America’s paramount territorial interest was in the western hemisphere, though dispositions must provide for the ultimate security of the British Commonwealth of Nations, a cardinal policy in this respect being retention of the Far East position “such as will assure the cohesion and security of the British Commonwealth”.25

Should Japan enter the war, military strategy in the Far East would be defensive, it was agreed; but the American Pacific Fleet would be used offensively in the manner best calculated to weaken Japanese economic power, by diverting Japanese strength away from the Malay Archipelago. It was held that augmentation by the United States of forces in the Atlantic and Mediterranean would enable Britain to release the necessary forces for the Far East. The British delegation proposed that the United States send four cruisers from its Pacific fleet to Singapore, but this proposal was rejected on the grounds that they would not be enough to save Singapore; that the United States might later be compelled either to abandon these vessels to their fate and face Japan with a weakened Pacific fleet, or reinforce them to the extent of applying the navy’s principal strength in the Far East, with resultant risk to the security of the British Isles.

The agreements reached at the talks were not formally accepted by either the British or the United States Governments, but planning proceeded along the lines agreed on by the staffs. Whether or not Japan became aware of this policy, it certainly suited her designs. European and American possessions in the area which Japan sought to dominate, whose peoples were insufficiently armed and trained by their rulers to enable them to defend themselves, were an inducement to aggression, especially if, by diversion of America’s main effort towards Europe, the extent of possible intervention in the Pacific by the United States Fleet would be lessened.

–:–

At this stage Germany retained her mastery of Europe, but Italian failures were proving an embarrassment to her in Greece and North Africa, and Britain was gaining strength. Russia, neutral but wary, was still a

Malaya

danger to Japan, who therefore maintained large forces along the borders of Manchuria and Mongolia. Despite the pro-British attitude of American leaders, isolationist sentiment in the United States was still strong. Perhaps the greatest single deterrent to further Japanese aggression was the presence of the American fleet in the Pacific. Was there any way by which Japan might remove this obstacle? “If war eventuates with Japan, it is believed easily possible that hostilities would be initiated by a surprise attack upon the fleet or the naval base at Pearl Harbour,” wrote Knox to Stimson on 24th January 1941. Knox added: “The inherent possibilities of a major disaster to the fleet or naval base warrant taking every step, as rapidly as can be done, that will increase the joint readiness of the Army and Navy to withstand a raid.” In this Stimson completely concurred. The United States Ambassador in Tokyo, Mr Grew, cabled to Hull on 27th January that there was talk in Tokyo that a surprise mass attack on Pearl Harbour was planned by the Japanese military forces in case of “trouble” between Japan and the United States. This report was passed on to the War and Navy Departments. The new Japanese Ambassador to Washington, Admiral Kichisaburo Nomura, who called on Hull on 12th February, gave an impression of sincerity in seeking to avoid war between the two countries. He said, however, in the course of interviews during which President Roosevelt and Hull at least did some frank talking, that his chief obstacle would be the military group in control in Tokyo.

The Lend-Lease Act, which provided means whereby Britain could obtain the supplies she needed from the United States without paying cash for them, was to become law on 11th March, providing a further answer by America to Japan’s signature of the Tripartite Pact. Evidence given by Hull in support of Lend-Lease before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs in January, in which he hit hard at Japan’s proposed “New Order” in Eastern Asia, stung the fiery Japanese Minister for Foreign Affairs to belligerent reply.

“Japan must demand America’s reconsideration of her attitude,” declared Matsuoka, “and if she does not listen there is slim hope for friendly relations between Japan and the U.S.A. I will try my hardest to make the United States understand, but I declare that this cannot be accomplished by courting – the only way is to proceed with unshakeable resolve.”26

Undaunted by an accompanying assertion by Matsuoka that Japan must dominate the Western Pacific, the Dutch rejected any suggestion of having the East Indies incorporated in a “New Order”, under the leadership of any Power whatsoever. Japan found opportunity further to assert her claim to such leadership, however, by acting as mediator between Thailand and Indo-China, the latter under Vichy (French) government

but now subject to Japanese domination. Fighting between Thai and French forces had flared up at the end of December, in a territorial dispute which it was suspected had been promoted by Japan. Terms for an armistice, presented by a Japanese general, were signed aboard a Japanese warship at the end of January, and a peace treaty was subsequently concluded in Tokyo.27

Matsuoka said early in February that the situation between Japan and the United States had “never been marked by greater misunderstanding”. The United States, however, gained means of knowing a great deal more about what was in the minds of Japanese leaders than the latter intended that they should. Although it was a top secret at the time, means of deciphering the secret code used in communications from Japan to her representatives in America were discovered by American experts. By this means, known as “Magic”, many of Japan’s secrets were bared. As an instance, Roosevelt was able to know not only what Nomura was saying to Hull, but Matsuoka’s instruction to Nomura of 14th February – to the effect that United States recognition of Japanese overlordship of the Western Pacific was the price sought for avoidance of war. At the same time it was learned that Japan contemplated the acquisition of military bases in Indo-China and Thailand, and ultimately an attack on Singapore; that her aims included incorporation of south-east Asia and the south-west Pacific in the Greater East Asia CO-prosperity Scheme.28

In London, in the second week of February, Mr Churchill

became conscious of a stir and flutter in the Japanese Embassy and colony. ... They were evidently in a high state of excitement, and they chattered to one another with much indiscretion. In these days we kept our eyes and ears open. Various reports were laid before me which certainly gave the impression that they had received news from home which required them to pack up without a moment’s delay. This agitation among people usually so reserved made me feel that a sudden act of war upon us by Japan.29 might be imminent. ...30

Thereupon Churchill sent Roosevelt a message, dated 15th February, in the course of which he said:–

Any threat of a major invasion of Australia or New Zealand would of course force us to withdraw our Fleet from the eastern Mediterranean, with disastrous military possibilities there. ... You will therefore see, Mr President, the awful enfeeblement of our war effort that would result merely from the sending out by Japan of her battle-cruisers and her twelve 8-inch gun cruisers into the Eastern oceans, and still more from any serious invasion threat against the two Australian [sic] democracies in the South Pacific.31

In Australia, cable messages from Japan were intercepted which instructed Japanese firms to reduce staffs and send home all who were not required, particularly women, by 1st March. In assessing the action likely to be taken by Japan in the near future pursuant of her southward expansion policy, the Senior Intelligence Officer at Army Headquarters, Colonel Chapman,32 reported that as at 8th February there were indications that the most suitable time for any such action would be in the three or four weeks ending in mid-March. An endeavour to convey a sense of urgency to the Australian public was apparent in newspaper reports of meetings of the Advisory War Council33 on 5th and 12th February. Records show that keen concern about the safety of Australia had been expressed by Mr Curtin, to the extent that at the later meeting he suggested a test mobilisation of Australia’s forces. Although this proposal was not adopted, he also drafted a suggested press statement. This was modified in response to objections that it might create a panic, but the statement issued contained a declaration that “it is the considered opinion of the War Council that the war has moved to a new stage involving the utmost gravity ... there should be neither delay nor doubt about the clamant need for the greatest effort of preparedness this country has ever made”.

The alarm soon died down; but it had served to draw more attention than hitherto to the danger from Japan, as compared with the needs of the Middle Eastern theatre of war. Mr Curtin, who would become Australia’s Prime Minister later in 1941, had declared publicly on 11th February that it was imperative that both the front and back doors of Singapore should be safeguarded, and Darwin and Port Moresby should be made as strong as possible. Islands of the Pacific must not become the spring-boards for an attack on Australia, and increased naval strength should be afforded to the Australia Station. Mr Menzies, who was in Cairo on his way to discuss the war situation with Mr Churchill and others in England, was asked to press for a frank appreciation by the United Kingdom authorities as to probable actions by Japan in the immediate future which would make war unavoidable, and possible moves she might make which would be countered by other means. Mr Menzies had passed through the Netherlands East Indies, Malaya, and India on his way from Australia.

At this stage Mr David Ross,34 a former air force officer, then Superintendent of Flying Operations of the Australian Department of Civil Aviation, was instructed to go to Dili, capital of the Portuguese section of the island of Timor, ostensibly as the Department’s representative there, but also to send Intelligence reports, especially about what the Japanese

were doing there, and to tell the Government how Australia’s interests in the area might be promoted.

Brooke-Popham flew to Australia and attended a meeting of the Australian War Cabinet on 14th February which discussed an appreciation of the position in the Far East by the Australian Chiefs of Staff. This followed receipt of the views of the United Kingdom advisers on the report of the October Singapore conference, and the tactical appreciation at that time by the commanders of the forces at Singapore. The British advisers held that the views of the Singapore commanders on the general defence position were unduly pessimistic, and that both the threat of attack on Burma and the need for additional land forces for defence of Burma and eastern India had been over-estimated. Nevertheless, the weaknesses in British land and air forces in the Far East, particularly the air forces, were “fully recognised”, and “everything possible was being done to remedy this situation, having regard to the demands of theatres which are the scene of war”. Brooke-Popham urged the War Cabinet to press on in every possible way with local manufacture of munitions. Reviewing prospects in his command, he said that although the defences on the mainland part of Hong Kong might be overcome shortly after war began, the island could defend itself for at least four months. In Malaya, even if Johore were captured by Japan, and use of facilities at the naval base lost, this would not prevent Singapore Island from holding out.

The supreme need at the moment was more munitions and more aircraft, Brooke-Popham declared; but he added that Japanese planes were not highly efficient, and he thought that the air forces in Malaya would cause such loss to the Japanese Air Force as to prevent it from putting the British forces out of action. Japanese fighter aircraft were not as good as Brewster Buffaloes, of which sixty-seven were on the water from the United States to Singapore. The training of the British and Australian Air Forces was more thorough and sounder than that of the Japanese. He said he did not look upon the Japanese as being air-minded, particularly against determined fighter opposition, and that the Japanese were not getting air domination in China despite overwhelming numerical superiority. He spoke, however, of the necessity for a clear definition of actions by Japan which would be regarded as justifying retaliation, and said that he hoped the line would be drawn at Japanese penetration of southern Thailand. He estimated the minimum naval strength necessary at Singapore at a battle squadron of four or five battleships and three or four cruiser squadrons totalling between ten and twelve cruisers, but said that with the British commitments elsewhere it would not be possible to provide this unless America joined in.

Neither the Australian Chiefs of Staff nor the War Cabinet were as confident regarding the situation as the United Kingdom authorities or Brooke-Popham. The Australian Chiefs of Staff gave warning that the current trend of events pointed to Japan having made up her mind to

secure freedom of action in Indo-China and Thailand for her forces, preparatory to securing control of those two countries. If the penetration included southern Thailand, they said, it might be regarded as a disclosure of intention to attack Malaya, and Japanese movement in strength into southern Thailand should be considered a cause of war. Numerous reports recently received had given evidence of great activity by the Japanese in increasing the defences and facilities of her mandated islands east of the Philippines, such as would facilitate seizure of further bases from which she could harry American lines of communication with the West Indies, and attack sea communications vital to Australia. Japan could make available forces greatly superior to the British and Dutch naval forces in the Far East and, in the absence of American intervention, was free to take any major course of action she might determine. She could provide a preponderance of military forces in any two of the three principal areas – Malaya, the Netherlands East Indies and Australia – and air forces greatly superior in numbers to the combined total of British and Dutch air forces in the Far East. If Australia deferred reinforcement of her “outer zone” of defence until hostilities began, she might find that Japan had forestalled her; but arrival of Australian troops at other than British territories, while she was at peace with Japan, might serve as a pretext for war.

The Australian Chiefs of Staff were anxious to establish air forces in the islands as far north as possible. The Chief of the Air Staff, however, was not willing to station air forces in the islands unless there were army garrisons to protect the airfields. With reluctance, General Sturdee agreed to send a battalion group to Rabaul for this purpose, and to hold two other such groups ready to go to Timor and Ambon when war became an immediate threat. The Chiefs of Staff recommended that these moves and preparations be made, but advised that the concurrence of the Dutch authorities be sought for the stationing of Australian forces in the Netherlands East Indies, particularly Timor; and that the 8th Division, instead of joining the Australian Corps in the Middle East as had been intended, be retained for use in the Australian area and East Asia.

The War Cabinet approved these recommendations; and decided to raise two reserve motor transport companies and one motor ambulance unit for service in Malaya, to overcome a shortage of drivers there which Brooke-Popham had mentioned. Soon after, the Cabinet decided, “in principle”, to move one AIF Pioneer battalion and one AIF infantry brigade group less one battalion, to the Darwin-Alice Springs area. These, with units already at Darwin, could provide one battalion for Timor and one brigade group for the Darwin area, as well as coast and anti-aircraft units. It authorised the distribution of one militia battalion between Port Moresby and Thursday Island; and the sending of one AIF battalion to Rabaul. Thus there would be three AIF divisions in the Middle East, a brigade at Singapore, another at Darwin, and another in training in Australia, where also a proportion of the militia was always in training.

The original plan to send a brigade group to Malaya, where it would be directly under Malaya Command, had given way to a decision to send also part of the divisional headquarters, on the ground that the staff of a brigade was insufficient to handle an Australian force in an overseas country. Major Kappe35 left Australia on 31st January with a small advanced party, and General Bennett on 4th February, by air, to set up the headquarters in Malaya. On 2nd February the 22nd Brigade and attached units boarded the 81,000-ton Queen Mary, formerly famous as Britain’s largest liner. The vessel (whose designation was then “H.T.Q.X.”) rode in Sydney Harbour, off Bradley’s Head, site of Taronga Park Zoo. Although efforts had been made to keep the destination of the troops, known as “Elbow Force”, as secret as possible, the embarkation became a great public occasion. Crates marked “Elbow Force, Singapore”, which had been waiting to be loaded on the ship, were among the factors which robbed security precautions of much of their effect. Relatives and friends of the men, and sightseers from city and country, crowded rowing boats, yachts, launches, and ferries, and massed at vantage points around the harbour when, on 4th February, the Queen Mary, accompanied by the 45,000-ton Aquitania and the Dutch liner Nieuw Amsterdam (36,000 tons) carrying troops to the Middle East, put out to sea escorted by the Australian cruiser Hobart.36

The convoy as a whole lifted approximately 12,000 members of the AIF. Their cheers mingled with those of many thousands of spectators ashore and afloat, the toots of ferries and tugboats, the screams of sirens, and the big bass of the Queen Mary’s foghorn as the convoy steamed down the harbour and through the Heads. Despite the brave showing of the farewell, it impressed on many more deeply than before the extent to which Australia was committed to a war on the other side of the world while it showed signs of spreading to the Pacific, and possibly to her own soil.

Colonel Jeater was addressing his men at sea next day on subjects which included the necessity for security measures, when the Queen Mary picked up a radio message that when the convoy had been at sea only twelve hours an enemy raider was within 39 miles of the ships.37 The voyage was otherwise uneventful until the Mauretania, carrying reinforcements to the Middle East, joined the convoy early on 8th February. At Fremantle, which the convoy reached on the 10th, small vessels circled the ships and collected parcels and letters from the men. These local craft

were searched when they returned to shore, and 6,000 pieces intended for mailing, which might have spread details of the force far and wide, were confiscated.38

The convoy weighed anchor again on 12th February, and next day Major Whitfield, Deputy Assistant Adjutant-General of the 8th Division, cleared air thick with rumours about the destination of the force when he told the men that they were going to Malaya, and described their probable role. On the 16th the British cruiser Durban came into sight, and swung into line abreast of the Australian cruiser Canberra, which had taken over escort duty from the Hobart at Fremantle. The scene which followed stirred the emotions of the entire convoy, as the Queen Mary swung to port, circled behind the other ships, and then when they were again in formation, charged past them at twenty-six knots. Wholehearted cheers burst from the men thronging the decks of the vessels, and from the nurses who accompanied them. New Zealanders cheered Australians; Australians cheered New Zealanders, with equal vim. Bands rolled great chords of music across the waters; then the convoy headed by the Canberra set course towards the sinking sun, and the Queen Mary and the Durban headed for the tropics and a land where never yet an Australian contingent of soldiers had set foot. The splitting of the convoy was eloquent of Australia’s now divided responsibilities – for assistance to the Imperial cause in the European war, and for helping to man barriers against onslaught by Japan.

A broadcast by Moscow Radio on 11th February to the effect that the Queen Mary had arrived in Singapore laden with Australian troops was recorded in Australia. The time of the broadcast was approximately nineteen hours after the vessel could reasonably have got there had she not, as happened, altered course shortly after leaving Sydney, and travelled via Fremantle instead of around the north of Australia. Whether or not this change of course misled enemy raiders, the Queen Mary, after several nights of stifling heat for the troops pent up under blackout conditions, arrived safely at Singapore on 18th February, and poured them into their new and strange environment.