Chapter 16: Struggle for Singapore

In the situation which faced General Bennett on the morning of 10th February, much depended on the Kranji–Jurong line. If the Japanese could not be held there, and prevented from exploiting their gains in the Causeway sector, presumably General Percival’s plan to form a defensive arc on the outskirts of Singapore would have to be put into effect. This would involve abandoning most of the island and, unless they could be destroyed, the outlying masses of ammunition and stores which General Percival had taken into consideration in his original plan to meet the enemy on the beaches.

To the forces assigned to the Kranji-Jurong area was added the 6th/15th Indian Brigade (Colonel Coates) which, as has been shown, was placed under General Bennett’s command on the afternoon of 9th February. Bennett had ordered it during the evening of the 9th to take up a position in the line on the right of the 44th Indian Brigade. This action appears to have been taken largely because of an erroneous report by a liaison officer that the 44th had been cut off on the Jurong road, was fighting its way through, and had suffered heavy casualties. A consequence of the order was that the 44th Brigade was required to sidestep from the positions which it was in process of occupying north of the Jurong road to others south and inclusive of it, with the brigade’s left in touch with the 2nd Malay Battalion at Kampong Jawa on the eastern bank of the Sungei Jurong. The move was difficult in the darkness and the rough country to which the brigade was allotted, especially as it was only partially trained and had no opportunity of reconnoitring the new positions.

Only patrol encounters occurred during the night of the 9th–10th February near the Bulim line. Soon after midnight Major Beale returned from a visit to Western Area headquarters with orders for withdrawal of Brigadier Taylor’s forces, after denying Bulim till 6 a.m., to the line being formed between the Kranji and the Jurong. Taylor, at 4.15 a.m., directed his commanders accordingly. He then visited 12th Brigade headquarters, and told Paris of the dispositions; saw some of his men taking up their new positions; and went to the rear to remove the grime from burning oil dumps with which he like many others had become covered. The 2/29th Battalion was to extend the 12th Brigade’s line astride the Choa Chu Kang road and link with the Special Reserve Battalion in its position north of West Bukit Timah. Major Merrett, whose force comprised remnants of the 2/19th and 2/20th Battalions, received orders to withdraw to about Keat Hong village, and the 2/18th Battalion was to go into reserve in the same locality. The 2/10th Field Company and the company of the 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion were to revert to divisional command.

In the course of the withdrawal, the 2/18th Battalion’s carriers remained in position, with shells falling among them, until its infantry had gone. The carriers were about to leave when two large groups of Japanese were seen, one marching along the road and the other south of it. Waiting in concealment until these came within close range, the crews blazed into them with their machine-guns, temporarily halted the enemy, and withdrew with their vehicles.

Three of the 2/29th Battalion’s companies, under Lieut-Colonel Pond’s second-in-command, Major Hore,1 reached the Argylls.2 The dispositions of the 12th Indian Brigade had been changed meanwhile to the extent that the 4/19th Hyderabad, formerly on the left flank of the Argylls near the junction of the Kranji-Jurong line with the Choa Chu Kang road, had been withdrawn at 2 a.m., apparently without Western Area headquarters or the 22nd Brigade having been informed, to the rear of the Argylls. Hore therefore decided in consultation with Colonel Stewart, the Argylls’ commander, to go into position on the Argylls’ left. This of course meant that the 12th Brigade forward line did not reach as far south as it would have done had the Hyderabads remained in it, and had the Australians been placed on their left to link with the Special Reserve Battalion as intended. The other company of the 2/29th Battalion had become detached, for seeing the other companies coming under fire as they reached the Choa Chu Kang road, Pond led it across country to the southern slopes of West Bukit Timah. There he put it into position in contact with 6th/15th Indian Brigade on its left, and went northward looking for the rest of his battalion. In doing so he located the Special Reserve Battalion headquarters, but as has been shown, the other companies of the 2/29th Battalion were farther north than had been intended, and Pond failed to find them. After returning to his remaining company, he unsuccessfully sought means of telephoning his brigade headquarters. Finally, he went to the headquarters for orders.

Meanwhile, at 12.50 a.m. on 10th February, Percival’s provisional plan for a defence arc round Singapore had been issued as a secret and personal instruction to senior commanders and staff officers. It specified that the northern sector of the arc would be occupied by the III Indian Corps (11th Indian and 18th British Divisions) commanded by General Heath. General Bennett’s responsibility would be the western sector, and General Simmons’ the southern sector. At the time the instruction was drawn up, the allocation of the 12th and 44th Indian Brigades had not been decided, but it was intended that at least one of these would be in command reserve. Bennett’s front was to extend from north-east to west of Bukit Timah village, and to about 750 yards west of the junction of

Reformatory and Ayer Raja roads (some 1,500 yards from Pasir Panjang village). The instruction set out that –

Reconnaissances of areas will be carried out at once and the plans for the movement of formations into the areas allotted to them will be prepared. Formations will arrange to move back and locate in their new areas units located in their present areas which are under command of H.Q. Malaya Command.

Percival had imparted the plan verbally to Heath and Simmons during the previous evening. He issued it so that responsible senior officers might know his intentions in case the situation developed too rapidly for further orders to be issued. Despite Bennett’s antipathy to warnings which might cause his commanders to “look over their shoulders”, the substance of the instruction was embodied in an order issued from his headquarters at 7.30 a.m. on the 10th. Although it indicated that the commanders might have to evacuate their sectors, it stated that no action except reconnaissance was to be taken pursuant of the order. In the event of the new positions being occupied, the AIF sector would be manned by the 27th Brigade on the right of Bukit Timah road (the name of the trunk road in the vicinity of Bukit Timah village) and the 22nd Brigade on the left, with the 44th Indian Brigade in reserve.

Typed copies of the order were dispatched. It naturally made commanders think in terms of how to withdraw should circumstances require it, and subsequent events suggest that in the confused situation in which they found themselves and with signal lines badly disrupted, it acted to some extent as a magnet to their thoughts. When Brigadier Taylor read the order its limited nature escaped him, and he interpreted it as requiring the new positions to be manned forthwith. He accordingly ordered the units under his command – other than the 2/29th Battalion and the Special Reserve Battalion, which were committed to the Kranji-Jurong line – to positions along the line of Reformatory road, in the sector provisionally allotted to his brigade. He had learned at this stage that an additional Australian unit, to be known as “X” Battalion, was being formed in Singapore by Lieut-Colonel Boyes, and would come under command of the 22nd Brigade. This, and remnants of the 2/18th Battalion under Lieut-Colonel Varley, he allotted to positions immediately west of the section of Reformatory road between Ulu Pandan road and Bukit Timah road, with Merrett Force in their rear a little east of Reformatory road. Each of these units was given a machine-gun platoon in support, leaving one in reserve at brigade headquarters. The 15th Anti-Tank Battery was to cover roads in the area, and an armoured car detachment would also be in reserve.

On his way to reconnoitre the new positions Taylor reported to Bennett, who tersely reproved him for his actions, but did not countermand the orders given by the brigadier. Taylor thereupon continued his reconnaissance. The total strength of the 2/18th and Merrett Force at this stage was about 500.

Early the same day (10th February) Brigadier Maxwell visited Western Area headquarters and was ordered to open his headquarters in a position where he would be at call of Area headquarters if required. This he did, in the Holland road locality, although in that position he was out of signal communication with his 2/30th and 2/26th Battalions in the Causeway sector. Meanwhile, the 2/30th under Major Ramsay had taken up its new positions in the Bukit Mandai area, east of the junction of Mandai road with the trunk road from the Causeway. The move by the

2/26th Battalion had been more extensive. With delegated responsibility on his shoulders for dispositions, its commander, Lieut-Colonel Oakes, ordered it to take up a line, east of the railway and the trunk road, from Bukit Mandai back to Bukit Panjang. This gave it a frontage of 4,000 yards, with each company occupying a hill position, and roadless gaps of up to 1,000 yards of dense vegetation between them.

Also early on the 10th General Wavell visited the island once more, and quickly went with Percival to see Bennett at his headquarters. The ensuing conference coincided with a Japanese bombing attack. Debris showered down and some casualties resulted, but the generals were unharmed. By this time, as has been shown, both Australian brigades had retracted from the fronts allotted to them, and were facing west. To Percival, Bennett seemed “not quite so confident as he had been upcountry. He had always been very certain that his Australians would never let the Japanese through and the penetration of his defences had upset him. As always, we were fighting this battle in the dark, and I do not think any of us realised at that time the strength of the enemy’s attack.”3

As Percival and Wavell left Bennett they passed

an undisciplined-looking mob of Indians moving along the road. They were carrying rifles and moving in no sort of formation. Their clothing was almost black. I must confess (wrote Percival) I felt more than a bit ashamed of them and it was quite obvious what the Supreme Commander thought. Only recently have I learnt the truth. This was the administrative staff of a reinforcement camp on the move. The quartermaster had some rifles in store and, good quartermaster as he was, had determined that they must be taken. So, having no transport, he had given one to each man to carry. ... Many of our troops looked more like miners emerging from a shift in the pits than fighting soldiers. It is difficult to keep one’s self-respect in these conditions, especially when things are not going too well.4

The two generals next visited General Heath, and went on to see General Key, whose headquarters were north of Nee Soon near the Seletar Reservoir. There they found that as the trunk road from the Causeway had been exposed to the enemy, Maxwell’s line of communication now ran back through Key’s area rather than Western Area. Percival decided to put the Australian brigade under Key’s command as soon as he had seen Bennett again. Meanwhile, regarding the junction of the Mandai road with the road from the Causeway as being vital to Key’s left flank, he sent a

personal instruction by dispatch rider to Maxwell to place his troops in more advanced positions in the area.

Percival also ordered General Heath to withdraw three battalions from the Northern Area and send them to the Bukit Timah area, which he now considered vital, and where they were to be a reserve under Bennett’s command. These, from different brigades of the 18th British Division, comprised the division’s Reconnaissance Battalion, the 4/Norfolks (54th Brigade), the 1/5th Sherwood Foresters (55th Brigade) and a battery of the 85th Anti-Tank Regiment. They were commanded by Lieut-Colonel Thomas,5 and designated “Tomforce”.

Back with Bennett early in the afternoon of the 10th, Wavell and Percival were informed that although the positions of the troops west of Bukit Timah village were not definitely known, the Kranji-Jurong line had been lost. As it transpired, the Japanese had quickly followed up the withdrawal from Bulim, and made contact with the main body of the 2/29th Battalion and the Argylls astride the Choa Chu Kang road. Out of touch with his brigade headquarters, lacking artillery support, and in danger of encirclement, the Argylls’ commander, Stewart, on his own initiative, decided to place them and the Australians in depth along the road, behind the Sungei Peng Siang, and some way back from the position they had been holding. Hore therefore moved his men to high ground near Keat Hong village, where they became the forward battalion; then, suffering from a mortar shell wound, he handed over command to Captain Bowring and left by motor cycle to seek orders from his brigade or divisional headquarters. Bowring told Stewart that he would remain in the position until by-passed by the Japanese, when he would fall back in stages.

While the Japanese were thus moving towards Bukit Panjang, as Brigadier Maxwell had feared they might, from the west, Brigadier Paris (12th Indian Brigade) received reports that his patrols had been unable to make contact with the unit of the 27th Brigade on his right (just as the 2/26th Battalion had been unable during the night to locate the 12th Brigade). Out of touch with Western Area headquarters, but concluding that an enemy thrust from the north along the trunk road towards Bukit Timah might be expected, he decided on his own responsibility to leave the 4/19th Hyderabad in its position on the Choa Chu Kang road between Bukit Panjang village and Keat Hong; and to place the three companies of the 2/29th Battalion in the village immediately covering the junction of the two roads, with the Argylls to the south.

Bowring and Paris met while the Australian companies were going into their covering position, and Bowring asked for an anti-tank battery to assist them in their task. Believing, however, that the enemy could not yet have landed tanks, Paris refused to meet the request. He similarly declined a later request by Bowring for a battery of the 2/10th Australian Field Regiment.

The moves ordered by Paris were completed early in the afternoon of the 10th. Thus the northern portion of the line between the headwaters of the Kranji and the Jurong was abandoned, and the right flank of the forces in the southern portion of the line – the Australian Special Reserve Battalion (Major Saggers) and the 6th/15th and 44th Indian Brigades – was left in the air. The 6th/15th Brigade had the British Battalion north of the Jurong road, the 3/16th Punjab echeloned back from its right flank, and the Jat Battalion in reserve. On the 44th Brigade front the 6/1st Punjab was on the Jurong road, the 6/14th Punjab was farther south, in touch with the 2nd Malay Battalion, and the 7/8th Punjab was in reserve to the rear of the 6/1st.

General Percival’s secret instruction indicating that a defensive line might be formed around Singapore had reached Brigadier Ballentine about 10.30 a.m. He thereupon notified Colonel Coates (6th/15th Indian Brigade) of its requirements, and told his battalion commanders that in the event of a retirement they were to move along tracks to Pasir Panjang village. Both brigades, and Saggers and his men at West Bukit Timah, were heavily bombed during the morning. Wild firing broke out in the 6/lst Punjab position about 1 p.m. This was followed by hasty withdrawal down the Jurong road of a number of vehicles, one of the battalion’s companies, and some men of the British Battalion. The Punjabis reported – incorrectly as it transpired – that the British Battalion had withdrawn, and permission was given to the battalion to readjust its line. However, the rearward movement quickly got out of control, and soon most of the brigade was streaming towards the village. There it was halted and reformed by Brigadier Ballentine, who received orders to move it to the junction of Ulu Pandan and Reformatory roads.

In the situation created by the withdrawal of the 44th Brigade, Coates moved his brigade back along the Jurong road, to within about two miles of Bukit Timah. Finding itself isolated and without orders, the company which Pond had placed in the Kranji-Jurong line withdrew in search of some Australian headquarters. Saggers used his men to extend the new 6th/15th Brigade position south of the road. Brigadier Williams6 (1st Malaya Brigade), with his right flank uncovered, withdrew the 2nd Malay Battalion to Pasir Panjang, but left outposts on the bridge over the Sungei Pandan.

At his early afternoon conference with Generals Percival and Bennett, while these events were in train, General Wavell said he considered it vital that the Kranji-Jurong line be used as a bulwark against the Japanese thrust from the west towards Bukit Timah, and urged that it be regained. Percival thereupon ordered Bennett to launch a counter-attack, and told him that in view of the situation which had developed in the Causeway sector the 27th Brigade would be placed under command of the 11th Division (General Key) as from 5 p.m. Percival also ordered that a large

reserve of petrol stored a few hundred yards east of Bukit Timah be destroyed.

Japanese troops had reached the Kranji ammunition magazine before engineers arrived to destroy it, and much of the ammunition which had been reserved for a prolonged resistance fell into their hands. On Wavell’s orders, the last of the serviceable aircraft and the remaining airmen on Singapore Island were withdrawn to the Netherlands East Indies. Air Vice-Marshal Maltby,7 who had been acting as Assistant Air Officer Commanding at Air Headquarters, went with them to become the commander of the RAF and RAAF units under the ABDA Command. In an order of the day Wavell declared:

It is certain that our troops on Singapore Island greatly outnumber any Japanese that have crossed the Straits. We must defeat them. Our whole fighting reputation is at stake and the honour of the British Empire. The Americans have held out in the Bataan Peninsula against far greater odds, the Russians are turning back the picked strength of the Germans, the Chinese with almost complete lack of modern equipment have held the Japanese for 4½ years. It will be disgraceful if we yield our boasted fortress of Singapore to inferior enemy forces.

There must be no thought of sparing the troops or the civil population and no mercy must be shown to weakness in any shape or form. Commanders and senior officers must lead their troops and if necessary die with them.

There must be no question or thought of surrender. Every unit must fight it out to the end and in close contact with the enemy. ... I look to you and your men to fight to the end to prove that the fighting spirit that won our Empire still exists to enable us to defend it.

In a covering note, General Percival said “... In some units the troops have not shown the fighting spirit expected of men of the British Empire.

“It will be a lasting disgrace if we are defeated by an army of clever gangsters many times inferior in numbers to our men. The spirit of aggression and determination to stick it out must be inculcated in all ranks. There must be no further withdrawals without orders. There are too many fighting men in the back areas.

“Every available man who is not doing essential work must be used to stop the invader.”

There was a Churchillian ring in Wavell’s exhortation; and indeed Mr Churchill sent him on this same day a cable on which obviously Wavell had drawn with characteristic loyalty but perhaps, under pressure of events, without mature consideration.

I think you ought to realise the way we view the situation in Singapore (said Churchill). It was reported to Cabinet by the C.I.G.S. [Chief of Imperial General Staff] that Percival has over 100,000 men, of whom 33,000 are British and 17,000 Australian. It is doubtful whether the Japanese have as many in the whole Malay Peninsula. ... In these circumstances the defenders must greatly outnumber Japanese forces who have crossed the straits, and in a well-contested battle they should destroy them. There must at this stage be no thought of saving the troops or sparing the population. The battle must be fought to the bitter end at all costs. The 18th

Division has a chance to make its name in history. Commanders and senior officers should die with their troops. The honour of the British Empire and of the British Army is at stake. I rely on you to show no mercy to weakness in any form. With the Russians fighting as they are and the Americans so stubborn at Luzon, the whole reputation of our country and our race is involved. It is expected that every unit will be brought into close contact with the enemy and fight it out. ...8

Mr Churchill said nothing about the Malayan campaign having been virtually lost at sea and in the air within a few days of its commencement; nothing about the disastrous dispersal of the army on the mainland to protect airfields now valuable only to the enemy; nothing about the Japanese monopoly of tanks; though indeed his figures did indicate that about half the force at Percival’s disposal comprised Asian soldiers. These, in the main poorly trained and inexperienced, and with many officers who were more or less strangers to their units, were pitted against other Asians who had become veterans of campaigns in China and were fighting ardently for their country instead of as subject people. The United Kingdom troops included the newly-arrived 18th Division; more than half the total number of Australians, with a divisional organisation but only two brigades, consisted of other than front-line troops. It will be seen later that Wavell was greatly mistaken in his estimate that the American-Filipino forces at Bataan were facing “far greater odds than the troops on Singapore Island”; nor was the island a Russia or a China, with their vast spaces for manoeuvre and enormous reserves of manpower. Singapore had been indeed a boasted fortress, but it was not the enemy who had been deceived by the boast. To Mr Churchill himself, as has been shown, it had become with a shock of discovery “the naked island”.

Wavell himself left Singapore at midnight, after injuring his back in a fall down some steps during an air raid blackout. Some of the events hitherto described in these pages were not known to him, but despite his order that Singapore must be held to the last, he went “without much confidence in any prolonged resistance”.9 He cabled to Mr Churchill stating that the battle for Singapore was not going well.

Indeed, time was running swiftly against the defenders. Even the effect of a last stand in an endeavour to buy time for resistance elsewhere would depend upon how quickly the essential parts of Percival’s disrupted and battered military machine could be reassembled and made to function.

–:–

Seeking meanwhile to retrieve the situation caused by timely notification not having reached him of the 27th Australian Brigade’s withdrawal from his left flank near the Causeway, General Key employed his reserve (8th Brigade) throughout the day (10th February) to occupy high ground overlooking the road and the Causeway. The troops made substantial gains, though at the cost of heavy fighting and many casualties. One of Key’s staff officers took to Lieut-Colonel Ramsay (2/30th Battalion) during

the morning a request that he send a platoon up to the junction of the Mandai road with the trunk road from the Causeway. Ramsay went forward with a small detachment, and decided to send up a company; but, on returning to his headquarters, received an order from his brigade headquarters to keep his troops in position. Thus when General Key himself visited the battalion about 1 p.m. and again asked for troops to be sent to the junction, Ramsay referred to this order and asked that the issue be taken up with his brigadier.

At 2 p.m., after receipt of Percival’s plan for a defensive line round Singapore, Brigadier Maxwell issued an order to his 2/26th and 2/30th Battalions to withdraw down the Pipe-line east of the trunk road to a rendezvous near the racecourse if they were unable to hold the enemy near Bukit Mandai. The order reached the 2/26th at 4 p.m., but was delayed in transmission to the 2/30th. The 27th Brigade came meanwhile under command of the 11th Division, and the 2/30th received the information at 5 p.m., with an order to move to the trunk (Woodlands) road on a line south from Mandai road. Maxwell reported to General Key about 6.30 p.m. Three companies of the 2/30th Battalion moved at 9 p.m. to high features immediately behind the junction of the two roads, with the fourth guarding the approaches along the Pipe-line north of Mandai road. It was understood by Ramsay that the 2/10th Baluchis would come up on the battalion’s right.

General Bennett had issued at 4.5 p.m. on the 10th, through his GSO2, Major Dawkins, instructions for the counter-attack ordered by Percival. Despite the rapid deterioration of the front, the weakness of the forces now available, and difficulties of organisation and control – factors more clearly apparent in retrospect than they would have been to Bennett with the limited information available to him at the time – these instructions required that the Kranji-Jurong line should be regained in three phases. The first objective was to be gained by 6 p.m. on the 10th; the second by 9 a.m. on the 11th; and the third – the reoccupation of the Kranji–Jurong line – by 6 p.m. that day. The 12th Brigade, with the 2/29th Battalion under command, was to be on the right in the attack; 6th/15th Indian Brigade in the centre; and the 22nd Australian Brigade on the left. The 44th Indian Brigade and Tomforce were in reserve positions. The 2/15th Australian Field Regiment was to be under 12th Brigade command and the 5th Field Regiment was to support the 6th/15th Indian and 22nd Australian Brigades.

Obviously this plan required very speedy action, with little or no time for reconnaissance of the ground over which the attack was to be made, and for correlating action by artillery and other arms; the more so because communication was largely by liaison officers, and the infantry units concerned were scattered and largely disorganised. The 6th/15th Brigade was the most intact, with about l,500 men. The Argylls, of the 12th Brigade, were less than 400 strong, including the administrative personnel, and the Hyderabads were melting away so rapidly that Brigadier

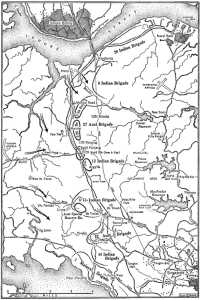

Western Front, Singapore Island, 7 p.m., 10th February

Paris could place little reliance upon them. The 22nd Brigade now included “X” Battalion, of about 200 Australians mustered by Lieut-Colonel Boyes, but the total number of troops available to Taylor was still small.10

After making his reconnaissance for occupation of Reformatory road, Brigadier Taylor received the counter-attack orders from Western Area headquarters, and issued corresponding brigade orders. In the latter part of the afternoon he again visited General Bennett, who gave him a somewhat more advanced objective. Taylor referred to the weakness of the forces at his disposal, and the difficulty of occupying positions in darkness, but Bennett stood firm as to his requirements. The brigadier therefore directed “X” Battalion to occupy a height known as Jurong I on the right, and Merrett Force (Major Merrett) to occupy the left at Point 85, west of Sleepy Valley Estate. The depleted 2/18th Battalion, and two platoons of the 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion, he retained in reserve at Reformatory road. Colonel Coates advanced the 6th/ 15th Indian Brigade to the small extent necessary to occupy its first-stage position, with the Jats (who it was intended should link with the 12th Brigade) on the right and the Punjabis on the left, both north of the Jurong road; and the British Battalion astride the road. The Special Reserve Battalion (Major Saggers) remained to the left of the British Battalion.

Any similar moves by the 12th Brigade (Brigadier Paris) were forestalled by the enemy. Soon after nightfall on 10th February Captain Bowring (2/29th Battalion) was informed that all the brigade’s forward troops had been withdrawn behind the 2/29th. He therefore moved his “C” and “D” Companies nearer the crossroads, leaving his “B” Company on high ground south-west of the junction, with orders to rejoin the others if it were too heavily attacked. Some of the 4/19th Hyderabads, however, were filtering through the Australians when, between 7 and 8 p.m., Japanese troops appeared, and heavy fighting ensued. Japanese tanks then joined in the attack, and although two or three were incapacitated the pressure, in the absence of anti-tank guns, became too great. Heading enemy troops estimated as at least two battalions strong, the tanks made their way along the trunk road towards Bukit Timah, and one of Bowring’s companies, west of this road, became detached. The others moved southeast along the Pipe-line, and were subsequently allotted to other positions. Some linked with the battalion’s “A” Company, and were reconstituted under Lieut-Colonel Pond. They included Captain Bowring with four of his officers and forty-five others who though out of contact with brigade headquarters had waited near Bukit Panjang until nearly midnight before withdrawing, and as will be seen were further occupied on the way back.

While the Australians were being attacked, the Argylls hurriedly improvised road-blocks of motor vehicles, and laid some anti-tank mines. About 10.30 p.m., when the leading Japanese tanks reached this point, a lone Argyll armoured car went into action against them, and was quickly knocked out. A large force of Japanese tanks and infantry followed, and although delayed at the road-blocks, the tanks pushed them aside and reached the outskirts of Bukit Timah village before they halted. The road in the Argylls’ area “was solid with tanks and infantry for the rest of the night”,11 and from positions in rubber east of the road the battalion heard someone shouting in English and Hindustani “Stop fighting. The war is over. All British and Indians are to rally on the road.” Stewart planned that his men should lie low until daylight, and then harry the enemy flank; but in the small hours of 11th February a force of Japanese moved up a track to within a few yards of battalion headquarters. Rather than engage in a confused struggle in the darkness, Stewart thereupon decided, with Paris’ agreement, to withdraw his men to the near-by Singapore Dairy Farm, which might serve as a base for further endeavour. His forward companies, however, were attacked and dispersed. Some of the battalion became engaged in near-by areas; others withdrew to the Tyersall Palace area.

Major Fraser, making a liaison trip from Western Area headquarters to the 12th Brigade after 2 a.m. on 11th February, came upon two of the brigade’s staff officers who were seeking to discover the whereabouts of its battalions. With their concurrence Fraser decided to establish a roadblock about 300 yards south of Bukit Timah village, and employed three Australian tractors and men of the 2/4th Australian Anti-Tank Regiment for the purpose. The block had no sooner been constructed than Japanese mortar fire began to fall just to the south of it. The staff officers having meanwhile withdrawn Fraser became senior officer on the spot. He organised gunners of the regiment to cover the block and form a local perimeter, then moved back about 300 yards towards two troops of British howitzers. Coming under fire from Japanese patrols at the side of the road he and his batman disposed of a machine-gun post with grenades. When he got to the howitzers he found that their crews had no orders and did not know what was happening, so he ordered them to fire over open sights at any tank which approached, then move back and be prepared to support a counter-attack on the village which he knew General Bennett intended. Fraser then went to the junction of Bukit Timah and Holland roads, which he reached about 6.20 a.m., to organise defence around that point.

–:–

Having displaced 12th Brigade and gained entrance by midnight on 10th–11th February to Bukit Timah, the enemy was able to seal off the eastern end of Jurong road, and thus sever the line of communication with 6th/15th Indian Brigade and the Australian units also in forward positions for the counter-attack towards the Kranji-Jurong line ordered by Percival.

Japanese fighting patrols pushed southward into the Sleepy Valley area at the rear of Merrett Force.

Unaware of these happenings, the men of “X” Battalion had nevertheless received with concern the unexpected order to advance into an area which none of them knew, and which soon would be cloaked in darkness. They were tired from their many and varied individual experiences since the Japanese landings. Now, as a scratch force, they were equipped with rifles, fifteen sub-machine-guns, eight light machine-guns, five 2-inch mortars, and two 3-inch mortars. Some of the men were armed with only hand grenades, and others carried only ammunition. Machine-gun carrier vehicles were to join the battalion next day. Lieut-Colonel Boyes’ second-in-command was Major Bradley,12 of the 2/19th Battalion, and his company commanders were Majors O’Brien (of the 2/18th) and Keegan (2/19th) and Captain Richardson (2/20th).

English troops through whom they passed in the Bukit Timah area, lurid with flames, reported that the enemy was just ahead. Snipers fired at them, and there were sounds of heavy fighting on the right. Boyes and Saggers, of the Special Reserve Battalion, met as “X” Battalion moved up. Taking a road bearing left from Jurong road, “X” Battalion found Jurong I trig. station, but not the Punjabis of the 6th/15th Indian Brigade who were to be on their right. Merrett Force, about 200 strong, which was to have been on their left, had followed a track from Reformatory road, but after forging a mile westward through bog and tangled growth, hanging on to each other’s bayonet scabbards to maintain contact, had formed a small defensive perimeter in Sleepy Valley to await daylight before pushing on.

Of the three companies of “X” Battalion O’Brien’s took up the right forward position and Richardson’s the left, with Keegan’s looking after the rear, close to battalion headquarters. Although the men were suspicious and uneasy in their surroundings, most of them had fallen asleep by 1 a.m. At 3 a.m. (11th February) the 18th Japanese Division, advancing along the Jurong road, launched a sudden and well-concerted attack on the

battalion front and flanks. This was soon aided by flames from a petrol dump near battalion headquarters, which the Japanese ignited with hand grenades.

Overborne in the rush, sentries were unable to give adequate warning. Some of the Australians were bayoneted in their sleep; others, half awake, sought to defend themselves, but many succumbed. In the full glare of the fire, the headquarters were an especially easy target, and Boyes and Bradley were killed. Assailed by small arms fire, grenades and mortar bombs, and then involved in hand-to-hand fighting, the battalion was soon overwhelmed. Groups dispersed in various directions, some to be again attacked on their way. Keegan was severely wounded in one such encounter and it became impossible to remove him. A party led by Lieutenant Richardson13 was challenged in English, and he went forward with his batman to investigate. Soon he shouted, “I’m O.K. but you clear out”. Although, thanks to his warning, the party succeeded in doing so, neither Richardson nor his batman was seen again. O’Brien’s company missed the main assault, and got away relatively intact, but the battalion’s losses were so great that it ceased to exist, and its remnants were drafted to other units.

Sounds of this struggle, and of firing to the rear, indicated to Merrett that his force was threatened with isolation, and he ordered his men to move back to Reformatory road at dawn. As the move commenced, at 5.45 a.m., the force came under fire, and a series of encounters followed, in which the force became divided into groups fighting different actions. Only remnants of this unit also got back to the Australian lines, and were re-drafted.

Of the forces in forward positions for the counter-attack ordered by General Percival, there remained on 11th February after the dispersal of “X” Battalion and Merrett Force, only the 6th/15th Indian Brigade and the Australian Special Reserve Battalion, astride Jurong road forward of Bukit Timah village. The strength of the battalion, on the left of the brigade’s British Battalion, was about 220. Its commander, Major Saggers, had reported to General Bennett at Western Area headquarters at 8 p.m. on the 10th, and been ordered to remain in position. From 1 a.m. on the 11th the battalion had heard firing at its rear and on both flanks. At 3 a.m. the men could see the blaze which occurred when “X” Battalion was attacked, but did not realise its significance. Finding all communication to his rear severed, Colonel Coates decided at 5.30 a.m. to cancel the counterattack his brigade was to have made at dawn.

His orders failed to reach the Jats, who went forward on their original instructions and became isolated.14 The British Battalion and Saggers’ men withdrew before dawn to a better defensive position about 400 yards to

their rear. As dawn broke the Australians could see Japanese troops silhouetted against the sky on a hill they had just left, and sharp exchanges of fire soon began.

The Japs pushed up to our line firing around and dodging behind trees, crawling along drains and using every fold in the ground (Saggers wrote later). Many had cut a bush and used this to push in front of themselves as they crawled forward, while others smeared mud and clay over their faces and clothing.

Brigade headquarters was attacked from Bukit Timah village, and Coates moved forward to the British Battalion’s headquarters, where in the midst of increasingly hot fighting he ordered a withdrawal across country to Reformatory road, in view of the obvious prospect that the brigade would become isolated if it tried to remain where it was, and annihilated if it attempted to pass through the village. By the time the move was under way the forward troops had held the enemy for nearly three hours, despite increasingly fierce small arms and mortar fire, and the danger that they might find themselves stranded by the tide of invasion. To assist other units to get away, one company of the British Battalion and one company (“E”) led by Lieutenant Warhurst15 of the Special Reserve Battalion joined just before 9 a.m. in a bayonet attack which quickly lessened the enemy pressure. The brigade then withdrew in three columns, British, Australian, and Indian. They had gone about a mile through the heavy scrub in the area when they came into an open saucer-shaped depression and were caught in a storm of rifle, light automatic and mortar fire from huts in front of them, and on both flanks. “Almost instantly the columns became intermingled,” wrote Saggers later, “and all control appeared lost. The more numerous Indians ... rushed across from their flank and intermingled with our troops ... many held up their rifles, butts uppermost, as a sign of surrender, and one produced a white flag which he held up.” Tommy-gun fire was pumped into the huts, but many men fell before the remnants of the columns escaped from the ambush.16 Even when they reached Reformatory road they were machine-gunned as they crossed it. East of the railway line, where the force was temporarily halted during a search for a headquarters from which instructions could

be obtained, Saggers could muster only eighty of his men, and there remained only about 400 of the Punjabis and the British Battalion. Neither the 12th nor the 6th/15th Indian Brigades, brought from reserve to help Bennett check the enemy, now remained effective, and Brigadier Taylor’s slender force on the line of Reformatory road stood directly in the path of the enemy advance on Singapore.

As survivors and stragglers drifted in during the small hours of 11th February to the Reformatory road area, and sounds of battle to the north and north-west were heard, Taylor realised that the situation in his sector was rapidly becoming critical. Moving south from Bukit Timah, Japanese attacked his headquarters in Wai Soon Gardens at 5 a.m., but were held off while dawn approached. To the right, on a rise overlooking Reformatory road, was Varley’s 2/18th Battalion, which had been transferred to this position from the Bukit Panjang area. It was about to move to ground offering a better field of fire, and to connect with brigade headquarters, when it also was attacked, but the move went on. As the Japanese increased their pressure on brigade headquarters, staff and attached officers, signallers, machine-gunners and infantry counter-attacked across Reformatory road, driving the enemy back from a near-by ridge. Beale, the brigade major, and Lieutenant Barnes,17 commander of the brigade’s defence platoon, were wounded leading bayonet charges. The Intelligence officer, Lieutenant Hutton,18 was killed as he assailed a Japanese machine-gun crew with hand grenades. Lance-Corporal Hook19 and Corporal Bingham were both severely wounded while leading a group of signallers against another machine-gun post. The Japanese were checked also when Lieutenant Iven Mackay,20 Varley’s carrier officer, with three carriers, charged up Reformatory road to Bukit Timah road, thence south to Holland road, and back to battalion headquarters. Using machine-guns and hand grenades, he and his men dealt out death and confusion. Enemy accounts indicate that having reached the objectives they had been given, and as delay had occurred in transporting artillery and ammunition to the island, the two Japanese divisions (5th and 18th) paused at this stage. The vigour of their attacks had suggested, however, that they would have pressed on had the resistance been less determined.

In the early hours of 11th February General Bennett received news of the Japanese having reached Bukit Timah village. He thereupon ordered Tomforce to come up at once to re-possess this village and then Bukit Panjang village. Lieut-Colonel Thomas ordered the force to carry out a sweeping movement to 2,000 yards on each side of the road for these purposes – a difficult task particularly because of the steep terrain on the right. The Reconnaissance Battalion was to advance astride the trunk

road, with the 4/Norfolks on the right of the road, and the Sherwood Foresters on the left. Still at the junction of Bukit Timah and Holland roads, where he had been organising resistance by such men as were available, Major Fraser met the commander of the Reconnaissance Battalion at 6.30 a.m., outlined the local situation to him, and discussed plans for the attack. In response to urgent requests from the anti-tank gunners in the perimeter position covering the road-block near Bukit Timah village, he arranged for a detachment to go to their assistance. He was still engaged in furthering the movement of the battalion when he met Lieut-Colonel Pond with part of the 2/29th Battalion, and informed him that he was under Tomforce command. When Thomas arrived Fraser informed him of the action he had taken; then he returned to Bennett’s headquarters and reported on the situation in the area from which he had come. It was decided to move Western Area headquarters back to Tanglin Barracks.

Meanwhile Captain Bowring and the portion of the 2/29th Battalion which had withdrawn with him from Bukit Panjang had taken up a position on the right of the trunk road behind Bukit Timah village, guarding guns of the 2/15th Australian Field Regiment. The guns were withdrawn about 6 a.m., but as the infantrymen were experiencing only occasional sniping from the enemy they remained in position. They came under fire from the Reconnaissance Battalion about 8 a.m., however, and when contact was established Bowring was taken to Thomas. Although the Australians had had practically no sleep for four nights, Thomas declined to relieve them, on the ground that their experience and knowledge of what was happening made them too valuable to be dispensed with at that stage.

Dissatisfied with the progress being made by Tomforce Bennett later instructed Fraser to return to the force with a message urging that it should press on with more vigour. As he was about to leave Fraser was informed that Major Dawkins would be sent in his stead, allowing him to gain some rest after his activities during the night. Dawkins was killed on his way forward, but the message was delivered by Bennett’s aide, Lieutenant Gordon Walker.21 The Reconnaissance Battalion encountered strong resistance near Bukit Timah railway station, adjacent to the junction of the Reformatory and Bukit Timah roads.22 The Foresters, to whom Pond with his part of the 2/29th Battalion gave left flank and rear protection, also came under fire nearby, but got to within 400 yards of the village. At 10.30 a.m., however, they were forced back some distance and Pond and his men found themselves pinned down a little east of the station. The Norfolks swung over to the Pipe-line and gained heights overlooking the village from the north-east, in the vicinity of the Bukit Timah Rifle Range, but were held there by Japanese who had penetrated the area.

As it transpired, the Japanese 18th Division was holding the Bukit Timah area, and the 5th Division was on commanding heights east of the trunk road in this locality, each division with two regiments forward. Thus, although heavy fighting occurred, Thomas found it necessary to withdraw his force during the afternoon to positions covering the Racecourse and Racecourse village. Pond received no orders and he and his men remained in position for some hours. They had been joined about midday by Bowring’s force which had been eventually relieved by the Reconnaissance Battalion to enable it to do so. As enemy troops had been seen by-passing them, Pond withdrew his force after dark, and in the course of skirmishes it became split into groups. With remnants of his headquarters company, Pond withdrew last, and reached General Bennett’s headquarters at dawn next day.

–:–

General Percival had woken at 6 a.m. on 11th February at his headquarters in Sime road to the sound of machine-gun fire which seemed to be about a mile away. He decided therefore to move to Fort Canning, and did so just before the main reserve petrol depot east of the Racecourse caught fire and added its smoke to the depressing pall from other such conflagrations. He then went up Bukit Timah road to see for himself how Tomforce was getting on.

It was a strange sensation (he wrote later). This great road, usually so full of traffic, was almost deserted. Japanese aircraft were floating about, unopposed except for our anti-aircraft fire, looking for targets. One felt terribly naked driving up that wide road in a lone motor car. Why, I asked myself, does Britain, our improvident Britain, with all her great resources, allow her sons to fight without any air support?23

This was a cry which had been in the hearts of his men for the past two months, as they suffered the miseries of their long withdrawal with little or no answer to the onslaughts of Japanese airmen, and under constant threat of seaborne attack to the flanks and rear. It had deeply concerned the Australian Government, seeking to gain the air reinforcements which, but for the demands of another war on the other side of the world, might have provided the answer.

Concerned at a gap west of MacRitchie Reservoir in the forces defending the near approaches to Singapore, Percival sent a unit composed of men from reinforcement camps to the eastern end of the Golf Course. He placed the 2/Gordons from Changi under Bennett’s orders, and made General Heath responsible for the whole of the area east of the Racecourse. With this responsibility on his shoulders, Heath considered the possibility that the enemy might thrust towards the reservoirs from the north, where the Guards Division had gained a footing, and between them from the Bukit Timah area, now held by the enemy. He therefore ordered another formation of brigade strength, commanded by Brigadier Massy-Beresford,24 to deny the enemy approach to Thomson village, east of MacRitchie Reservoir,

and the Woodleigh pumping station, farther east. This formation, known as Massy Force, which was also to form a link between Tomforce and the reservoirs, took up positions during the afternoon at the eastern end of MacRitchie Reservoir. It comprised the 1/Cambridgeshire, from the 55th Brigade, the 4/Suffolk (54th Brigade), the 5/11th Sikh (from Southern Area), a detachment of the 3rd Cavalry, one field battery, and eighteen obsolescent light tanks recently landed, and manned by a detachment of the 100th Light Tank Squadron.

Mr Bowden, Australian Government representative in Singapore, had cabled to Australia on 9th February: “It appears significant that February 11th is greatest Japanese patriotic festival of the year, namely, anniversary of accession of their first Emperor, and it can be taken as certain that they will make a supreme effort to achieve capture of Singapore on this date.”25 General Yamashita, commander of the Japanese forces in Malaya, chose the morning of the 11th to send aircraft with twenty-nine wooden boxes, each about eighteen inches long, to be dropped among the forces now seeking desperately to retain their last foothold on the illusory stronghold of British interests in the Far East. They contained a note addressed “To the High Command of the British Army, Singapore”. It read:–

Your Excellency,

I, the High Command of the Nippon Army based on the spirit of Japanese chivalry, have the honour of presenting this note to Your Excellency advising you to surrender the whole force in Malaya.

My sincere respect is due to your army which true to the traditional spirit of Great Britain, is bravely defending Singapore which now stands isolated and unaided. Many fierce and gallant fights have been fought by your gallant men and officers, to the honour of British warriorship. But the developments of the general war situation has already sealed the fate of Singapore, and the continuation of futile resistance would only serve to inflict direct harm and injuries to thousands of non-combatants living in the city, throwing them into further miseries and horrors of war, but also would not add anything to the honour of your army.

I expect that Your Excellency accepting my advice will give up this meaningless and desperate resistance and promptly order the entire front to cease hostilities and will despatch at the same time your parliamentaire according to the procedure shown at the end of this note. If on the contrary, Your Excellency should neglect my advice and the present resistance be continued, I shall be obliged, though reluctantly from humanitarian considerations to order my army to make annihilating attacks on Singapore.

In closing this note of advice, I pay again my sincere respects to Your Excellency.

(signed) Tomoyuki Yamashita.

1. The Parliamentaire should proceed to the Bukit Timah Road.

2. The Parliamentaire should bear a large white flag and the Union Jack.

Captain Adrian Curlewis,26 one of Bennett’s staff officers, was given the note from a box which fell in the Australian lines. Covered in grime

from the smoke-laden air, he took it to Fort Canning, and handed it to Colonel Thyer, who was there.

Yamashita’s statement of the plight of Singapore was all too true. On the face of it, the note was a courteous and considerate offer to cease hostilities. Perhaps certain terms might even be obtained to modify the bitterness and humiliation of surrender. This, in any event, could hardly be long postponed, as the events of the day were making increasingly evident. With the loss of all the food and petrol dumps in the Bukit Timah area, only about fourteen days’ military food supplies remained under Percival’s control; the remaining petrol stocks were running perilously low; Singapore’s water supply was endangered as the enemy approached the reservoirs and the pumping station, and water gushed from mains broken by the Japanese bombardment. Incendiary bombs dropped on the crowded and flimsy shops and tenements which occupied much of the city area might start a holocaust which nothing could arrest. What civilians and troops might suffer in this event, or if the Japanese forces in the heat of battle were to break into Singapore, was a horrifying speculation.

But General Percival was under orders from General Wavell, who, in keeping with Mr Churchill’s instructions, had decreed that “there must be no thought of sparing the troops or the civil population”. Whatever Percival’s intellect or feelings might have dictated, his orders were clear. Percival cabled to Wavell, telling him of the Japanese demand for surrender. “Have no means of dropping message,” Percival added, perhaps unconscious of the irony of these words, “so do NOT propose to make reply, which would of course in any case be negative.”

As yet, the Japanese Guards Division on the 11th Indian Division’s left flank was playing a minor role, but General Heath’s anxieties grew when he learned early on 11th February that the 27th Australian Brigade had been ordered to recapture Bukit Panjang.27 As this would remove the brigade from use against the Guards, a proposed attack by the Baluchis to regain ground on the 2/30th Battalion’s right flank was cancelled, and the battalion was ordered to a defensive position astride the Mandai road about two miles back from Mandai Road village. Maxwell had moved his headquarters to a point near Nee Soon, some 8,000 yards east of Mandai Road village. Orders for Colonels Ramsay and Oakes, timed 8.44 a.m., were conveyed by Captain Anderssen28 of the 2/26th Battalion, who had reported at brigade headquarters on his way from hospital to rejoin the battalion. The move on Bukit Panjang was to commence at 11 a.m., which was the earliest Maxwell thought it possible. Travelling at first on a motor cycle, and then on foot, Anderssen did not reach Ramsay’s headquarters

until about 10.30 a.m. When he got to the headquarters Oakes had been occupying, he found that all but “C” Company of the 2/26th Battalion had moved, and as Oakes was not there he was unable to give him the order. As it happened, a message had reached Ramsay meanwhile by runner from Oakes, indicating that he was moving his men down the Pipeline towards the Racecourse, but Ramsay could of course assume that this movement would be cancelled by the counter-attack order.

Clashes by the forward troops of the 2/30th Battalion with Japanese troops during the morning had made it evident that they were present in strength, but the Australians were in the disconcerting circumstance of having contact neither with the Baluchis nor with the 2/26th Battalion to the left. By the time Colonel Ramsay received the order to move on Bukit Panjang, extensive fighting was in progress between his men and the enemy, but most of the battalion broke contact without serious difficulty. Captain Booth’s29 company in its rear position guarding approaches to the Pipe-line at Mandai road had found early in the morning that the Japanese had penetrated between it and the main battalion positions. The company was ordered to hold on as long as possible to allow the other companies to get clear, and fought hard to do so. Eventually, because of enemy infiltration on its right flank and at its rear its commander ordered withdrawal. This was in progress when a two-pronged attack was made on the right and left of its position.

Men, machine-guns and mortars were rushed back, and two of the forward machine-guns were fired at almost point-blank range as Japanese swarmed over a ridge in front of them. Mortars, too, were used to marked effect, but after suffering considerable losses the enemy deployed along the company’s flanks under cover of high ground. The Australian company therefore continued to withdraw, with its forward troops fighting from tree to tree to give cover to the rear. Having used its last round, the mortar section loaded its weapons on a truck, but the Japanese put it out of action before it could be driven away. The machine-gunners also lost their vehicle, in similar circumstances. Following the route of the Pipe-line, the Australians were pressed with more persistence than the enemy had shown on the mainland. Particularly as wounded men had to be carried by hand, a section commanded by Lieutenant Hendy was detailed to act as a rearguard. It fought gamely, though the number of Japanese swarming over the recently contested ground and along the line of withdrawal showed that a substantial force was being employed to force the pace. It was only when the company reached the battalion rendezvous a mile short of Bukit Panjang that contact was broken, and it rejoined the main body.

Colonel Ramsay, unable to locate or obtain further news of the 2/26th Battalion, out of touch with his brigade headquarters, unaware of the strength of the enemy in the Bukit Panjang area, and with Japanese forces to his rear, concluded that he would be unable to justify throwing his battalion alone into a counter-attack in such circumstances. He therefore

decided to lead his men eastward through the municipal catchment area to Upper Thomson road, by a track parallel to Peirce Reservoir where he hoped to regain touch with brigade headquarters. With a heavy over-lacing of jungle growth, the track was, in the words of the Headquarters Company commander, Captain Howells, “as cool and cloistered as a cathedral aisle”. During mid-afternoon the leading troops came upon Captain Matthews,30 the brigade signals officer, who with a party of his men was laying a cable to the now-abandoned attack rendezvous. Ramsay was thus able to speak to Maxwell, telling him of the move, and arranging transport for his wounded. He received orders to continue his move to Thomson road. Near nightfall about seventy men of the 2/26th Battalion led by Captain Beirne emerged on the track. They related that the battalion had been ambushed while moving along the Pipe-line, south-eastward from the Bukit Panjang area. With this addition the column eventually reached its objective and was placed between the Peirce Reservoir and the Seletar Rifle Range to block a possible Japanese attempt to cut the road south of Nee Soon, perhaps by way of the track the column had used.

Oakes had become aware of the break-through towards Bukit Timah when about 10 p.m. on 10th February the 2/26th Battalion regimental aid post truck, well to the rear of his headquarters and near a company of the 2/29th Battalion, was captured. His Intelligence officer, Lieutenant Moore,31 whom, in the absence of contact, he had sent during the morning to brigade headquarters, returned in the afternoon with Maxwell’s order for the battalion to rendezvous at the Racecourse in the event of further withdrawal. Early next day a report reached Oakes that large bodies of Japanese, supported by tanks, were moving along the Choa Chu Kang road within a few hundred yards of his headquarters, making for Singapore. Japanese planes appeared to be concentrating on the main road south of the battalion area. The battalion had almost run out of rations at the time. Deciding that it was too widely dispersed to mount an attack, Oakes ordered his men to withdraw south-east to the rendezvous, each company to move as a separate fighting force if the column was broken. The move began at 10.15 a.m. on 11th February – a quarter of an hour before the time specified in Brigadier Maxwell’s order (of which Oakes was unaware) for the counter-attack on Bukit Panjang.

After a two-hour march “D” Company (Captain Tracey) which was in the lead, reached ground overlooking the Singapore Dairy Farm, a former site of the brigade headquarters, and the men were astonished to see what were estimated at 2,000 troops sitting in the open. Opinion was divided as to whether they were Japanese or Indians, but it was decided, especially as the battalion could not be assembled for attack without being observed, to continue the withdrawal. The company thereupon swung

east into jungle growth, and followed a compass course until it came to a dirt road north of the Swiss Rifle Club, where a sharp clash occurred with Japanese troops. In this, Private Hayman32 distinguished himself by getting wounded men away on two occasions and returning to the fight. After fending off the enemy attack, the company acted as a rearguard and with the rest of the battalion, less “A” and “C” Companies, reached the Singapore Golf Course.

Meanwhile “A” Company (Captain Beirne) to the rear, with a “B” Company platoon replacing one of its own, had encountered other Japanese. Calling out that the company was surrounded, a Japanese spokesman promised that if it surrendered the troops would be back in Australia in a fortnight. Private Lloyd33 was captured and sent back with a similar message. Someone else, who claimed to be an Argyll, shouted that he was a prisoner and that the enemy was a thousand strong. Machine-guns were seen behind buttresses of the Pipe-line. However, Beirne decided that the company should fight its way out, and after a short but furious encounter it succeeded in joining the 2/30th Battalion on the track to Nee Soon. A platoon which was cut off during this move rejoined the 2/26th Battalion, at the Golf Course.

Last in the column, “C” Company was met by Captain Anderssen at 11.45 a.m. and given a copy of the order for recapture of Bukit Panjang. However, as it was obvious that the order could not now be put into effect, and as it indicated that the Japanese had got through to the Racecourse and Sime road, the company set out to follow the Pipe-line to the Dairy Farm and then to move east on a compass bearing. It eventually found its way to the General Base Depot at the Island Golf Club which was in charge of Lieut-Colonel Jeater.

Oakes decided that his group should move from the Singapore Golf Course to Bukit Brown, south-east of it, for the night and Captains Tracey and Roberts34 were sent in search of brigade or other headquarters where orders could be obtained. Tracey eventually got through by telephone from Fort Canning to General Bennett’s headquarters and received orders for the battalion to move at first light from Bukit Brown to Tyersall Park, which surrounded the Singapore residence of the Sultan of Johore. There it met remnants of the 12th Indian Brigade.

Taking into consideration the circumstances on his left flank, General Heath had decided meanwhile to abandon the Naval Base area. The 53rd Brigade readjusted its line to face north-west, covering the Sembawang airfield, and the 8th Brigade continued the line southward, across the east-west road to Nee Soon. The 28th Brigade went into reserve beside Thomson road, south of Nee Soon. What remained of the 18th Division

after supplying troops to Tomforce and Massy Force remained where it was. During the afternoon of the 11th General Percival, with Heath’s concurrence, ordered Massy Force to occupy Bukit Tinggi, west of the Mac-Ritchie Reservoir, and establish contact with Tomforce; but enemy troops got there first. Massy Force thereupon went into a position from the reservoir to the northern end of the Racecourse, where the contact with Tomforce on its left was made.

–:–

Steps had been taken before 9 a.m. on 11th February to consolidate the 22nd Brigade position. Brigadier Taylor decided to move his headquarters back along Ulu Pandan road to its junction with Holland road, where line communications had been laid on. Part of the 2/18th Battalion lost contact during its move under heavy fire to new positions, but with such other fragmentary forces as became available, the front was held. The latter included about ninety men under Major Robertson of the 2/20th Battalion, who had been got together as a nucleus of a “Y” Battalion which it was intended to form largely of reinforcement troops. Heavy fighting and casualties followed, with Captain Chisholm from time to time leading parties of men, including British and Indian troops, to wherever they were most needed, and Mackay’s men again giving valiant aid. Heavy artillery fire became available early in the day, and was effectively used among Japanese troops massing for attack. Bennett’s headquarters at Holland road closed after mortar bombs had fallen in its grounds, and was reopened at Tanglin Barracks, south of Tyersall Park and Holland road.

Early in the afternoon Brigadier Taylor, with General Bennett’s concurrence, shortened his front, and swung it so that it would be in line on its right flank with Tomforce. Its main position would face west in an arc from the southern junction of the railway and Holland road to near the junction of Ulu Pandan and Reformatory roads, with its apex at Ulu Pandan IV. Bennett ordered as many men as could be made available from the 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion to be sent to fight as infantry on this front, and arranged with Percival that the 2/Gordon Highlanders should be ordered up to fill a gap between the brigade and Tomforce on its right. On the left, the 44th Indian Brigade continued the 22nd Brigade line southward to Ayer Raja road. From there to the coast at Pasir Panjang was occupied by the 1st Malaya Brigade, reinforced by the 5/Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire (less two companies) from the 18th Division, and a battalion formed from Royal Engineer and Indian Sapper and Miner units.

Taylor directed that a composite company of forty men of the 2/20th Battalion led by Captain Gaven,35 which had reached him at noon, should be on his right flank (where they were joined by “D” Company of the 2/29th). The bulk of the 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion was to be in the centre, with Robertson’s force and some of the machine-gunners on the

left. The British Battalion and some other United Kingdom troops who had come under Taylor’s command were to support the line, and the 2/18th Battalion was to go into reserve. The new line was manned, though with difficulty, under constant attack from land and air. Pressure had been particularly heavy in the northern part of the bulge in Reformatory road, and of 71 men led by Captain Griffin (2/18th Battalion) who had occupied a foremost feature in the area, only 22 came out of action. Private Beresford36 acted as No. 1 of a light machine-gun crew while five successive No. 2’s were wounded, and until the gun was destroyed by Japanese fire. Small groups of men arrived during the day to rejoin their units, whose strength therefore was constantly changing. In response to a request by Brigadier Ballentine, the British Battalion and some other troops who had become attached to it were placed under his command. Artillery support by both Australian regiments and the 5th Regiment, Royal Artillery, continued throughout the night of 11th–12th February, and appeared to be hampering further development of the enemy attack.37 General Percival recognised that Brigadier Taylor’s men had held their ground “most gallantly”.38 They had in fact been attacked by the 56th and 114th Regiments of the 18th Japanese Division at heavy cost to the Japanese in casualties.

The Indian Base Hospital at Tyersall caught fire during the day. The huts of which it was comprised blazed fiercely, and despite gallant rescue work by Argylls and Gordons, most of the inmates perished. As another grim day ended, Percival was faced with the need for further revision of his plans. At midnight on 11th–12th February he gave Heath command of all troops to and including the trunk road39 near Racecourse village, on his left. These included Tomforce, formerly under Bennett’s command, which was now combined with Massy Force. The new boundary for Bennett’s forces was from this point to Ulu Pandan road, and General Simmons was responsible for the rest of the front to the coast.

–:–

The tempo of battle increased sharply on 12th February. With half the island in their possession, the Japanese sought to enforce their demand for surrender. While Heath continued to realign his forces, the 2/10th Baluch held off Japanese tanks and troops attempting to reach Nee Soon. Massy Force was attacked and gave ground. At 8.30 a.m. enemy tanks dashed down Bukit Timah road as far as the Chinese High School before they were turned back by United Kingdom troops, and a patrol of the Australian 73rd Light Aid Detachment firing at the tanks with rifles – their only weapons. The patrol was from a modified infantry battalion formed

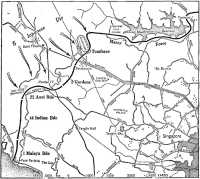

South-western front, early morning 12th February

by Lieut-Colonel Kappe, commander of the Australian divisional signallers, of about 400 men who could be spared from signals and other duties. (Kappe named it “the Snake Gully Rifles”.) The patrol was led by Captain Couch,40 of the 2/20th Battalion. The thrust by the tanks caused confusion in Massy Force, and resistance had to be hastily reorganised. The force was withdrawn during the morning from the Racecourse area to the general line of Adam and Farrer roads, which meet Bukit Timah road about 3,000 yards south-east of Racecourse village. Couch’s force of Australian signallers and others, stationed between Massy Force and the 22nd Brigade, resolutely checked Japanese attempting to penetrate its area.

Percival again drove forward to see for himself what was happening. This convinced him that there was a real danger that the Japanese would break through in the area. Reflecting that, as things were, there would then be little to stop the enemy from entering the city, he went to see Heath. They agreed that it would be foolish to keep troops guarding the

northern and eastern shores of Heath’s area while the city was thus endangered. Percival therefore decided to put into effect his plan to form a defensive line round Singapore, though now it would have to be smaller than the one he had previously planned. He therefore ordered Heath to withdraw the 11th Indian Division and the remainder of the 18th British Division to positions covering the Peirce and MacRitchie Reservoirs, and General Simmons to prepare to withdraw his troops from the Changi area and the beaches east of Kallang. These were major decisions, bearing also on the civil administration, so he then went to see the Governor. Sir Shenton Thomas, with characteristic phlegm, had remained at Government House despite repeated shellings. He reluctantly agreed to order destruction of Singapore’s radio broadcasting station, and of portion of the stock of currency notes held by the Treasury.

The line to be occupied included the Kallang airfield and ran thence via the Woodleigh pumping station, a mile south-west of Paya Lebar village, to the east end of the MacRitchie reservoir; to Adam road, Farrer road, Tanglin Halt, The Gap (on Pasir Panjang ridge west of Buona Vista road), thence to the sea west of Buona Vista village. Sectors allotted were: Kallang airfield–Paya Lebar airstrip, 2nd Malaya Brigade; airstrip to Braddell road one mile west of Woodleigh, 11th Division; thence to astride Bukit Timah road, 18th Division; to Tanglin Halt, the forces under General Bennett’s command (including 2/Gordons); Tanglin Halt to the sea, 44th Indian Brigade and 1st Malaya Brigade.

General Bennett, too, had been taking stock of the perilous situation. Lieut-Colonel Kent Hughes had urged that all Australian transport and troops, except the men in hospitals, be brought out of the city proper, and a plan had developed to create an AIF perimeter in the area around Tanglin Barracks up to Buona Vista road, where the Australians would make their last stand together. Colonel Broadbent, Bennett’s senior administrative officer, had set about the task of preparing for the move.

Meanwhile Brigadier Taylor, dazed with fatigue but unable to sleep, sent for Lieut-Colonel Varley, who had been with his 2/18th Battalion in reserve during the night, and asked him to take over, temporarily, command of the brigade. “I realised,” Taylor recorded, “that I would have to get a few hours’ rest in a quiet spot; my brain refused to work and I was afraid that if I carried on without rest the brigade would suffer.” Having given the order, he collapsed and, with Captain Pickford,41 his Army Service Corps officer, was taken to divisional headquarters. Pick-ford hurried in with the news, and Taylor, reviving, entered after him. After reporting to Bennett, Taylor returned to his brigade headquarters with some maps which were required. As he got back into his car, his acting brigade major, Captain Fairley,42 took the responsibility of ordering the driver to take the brigadier to hospital, irrespective of what he said.

Taylor, however, insisted on being driven back to Western Area headquarters again on the way.

The 22nd Brigade had spent a relatively quiet night, attributed largely to close and effective cooperation between British and Australian field artillery, and fire by fixed defences guns to the area of Bukit Timah village and of the main road north of it. Before noon on the 12th an armoured car detachment commanded by Corporal Brisby43 encountered an enemy convoy a little south of the Ulu Pandan-Reformatory roads junction, which indicated a move past the brigade front to the southern flank. The detachment disabled thirteen trucks and one car, creating a temporary roadblock at this spot. Varley was informed during the morning that he had been promoted by Bennett to brigadier, and remained in command of the brigade. The number of Australian troops at his disposal was approximately 800, including 400 in the 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion. Valuable aid was being given by about 100 Sherwood Foresters.

The 27th Brigade was now out of action as such. In the withdrawal from the Northern Area ordered by General Percival, the 2/30th Battalion came temporarily under command of the 53rd Brigade (Brigadier Duke). Men of the 2/29th Battalion not posted on the 22nd Brigade front were being rested, refitted and reassembled by Lieut-Colonel Pond in the Tanglin area. The 2/26th, among spacious and beautiful homes in the Tyersall Park area, experienced a strange reaction to their struggles in plantations and jungle. Their respite was brief, for at midday they were sent under shelling and air attack to occupy a position left of Bukit Timah road and forward of Farrer road, on the right flank of Bennett’s final perimeter. The move was made more difficult and hazardous by the activities of snipers, who seemed to be in every house and tree, while “hundreds of enemy planes were carrying out every kind of attack on Singapore city and troops. Five enemy raids were counted in twenty minutes.”44

Bennett received news during the day that the last of the Australian nursing sisters and the matrons of the two Australian general hospitals had embarked for Australia. The 2/10th A.G.H., at Manor House and Oldham Hall, though under shell and mortar fire, was still behind the front line, but the 2/13th, at St Patrick’s College beyond the Kallang airport, would be exposed by the withdrawal to the defensive line planned by Percival. Bennett decided that as the city was under such heavy assault from land and air it would be better to leave the inmates where they were. “I consider that the end is very near,” he noted, “and that it is only a matter of days before the enemy will break through into the city.”45 That day Brigadier Callaghan, commander of the Australian artillery, returned to his headquarters from hospital, but Colonel McEachern remained in command of the artillery.

The Japanese 18th Division persisted in attempts to thrust between Varley’s and Ballentine’s brigades near the Ulu Pandan-Reformatory roads junction. On Varley’s right, penetration was occurring in the area between the Ulu Pandan-Holland roads junction and Racecourse village to the north, across the northern flank of the machine-gunners on Ulu Pandan IV. Evidently therefore an attempt was being made to envelop or by-pass the Australian forward positions. Machine-gun detachments sent to the railway bridge across Holland road halted a force approaching the 2/Gordons on the right flank. An armoured car detachment led by Stanwell,46 of the 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion, engaged in a sharp fight, until the car was disabled, with enemy troops on Holland road just south of Racecourse village. The results obtained in these engagements by armoured cars led naturally to thought of what might have been achieved had the Australians been equipped with tanks.

Varley ordered up the 2/18th Battalion, now commanded by Major O’Brien, with Captain Okey as his second-in-command, to deal with the Japanese turning movement on his left. Late in the afternoon he ordered it to drive Japanese from a rise which they had captured from the Punjabis, south of Ulu Pandan road and east of Reformatory road. The brigade area, however, was constantly under bombardment and Japanese planes were circling like hawks, swooping from time to time to strike. The Japanese, in good cover, were covering their approaches with fire, and the positions occupied by the machine-gun battalion and Robertson’s “Y” Battalion were swept by bullets and mortar bombs. Lieutenant Mackay brought forward a water truck, machine-guns, and three armoured cars manned by British troops. Captain Chisholm, in charge of a force allotted to the task, himself acted as forward observation officer for counter-artillery fire. O’Brien’s men, numbering about sixty in the vicinity of the ridge, reached its forward slopes but as night fell they had not dislodged the enemy.

Japanese, thickly clustered on hills west of Reformatory road, also thrust strongly against the brigade’s northern positions, with the result that they gained a height between the road and Ulu Pandan IV. Under pressure from both flanks, the Australians were gradually forced back. The commander of the 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion, Lieut-Colonel Anketell,47 was mortally wounded, and his battalion, after mowing down successive waves of Japanese, became almost surrounded. Fifty of the 400 Australians were killed or wounded.