Chapter 4: The Japanese Advance to Kokoda

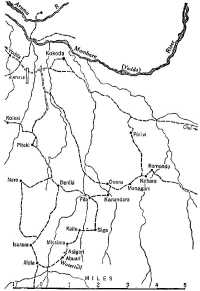

KOKODA lay in the green Yodda Valley, 1,200 feet above sea level, on the northern foothills of the massive Owen Stanley Range. It contained a Papuan Administration post, a rubber plantation, and the only aerodrome in Papua between Port Moresby and the northern coast. A primitive foot track crossed the mountains from Port Moresby and then ran east-Northeast from Kokoda to the Buna–Sanananda–Gona area by the sea. Much of the Port Moresby–Kokoda sector was merely a native pad. Few passed over it—only the barefoot natives, or occasionally a missionary, a patrolling officer of the Administration, or some other wandering European. Aeroplanes served the Yodda Valley. The infrequent travellers whose business took them to the Northeast coast generally went by sea, or flew to Kokoda and walked down.

A road climbed 25 miles or so from Port Moresby up to the Sogeri plateau and across it to Ilolo on the edge of the plateau facing into the main ranges. These rose turbulently to the clouds. Forests covered them densely with seas of green. Winds moaned through them. Rains poured down upon them from clouds which swirled round the peaks and through the valleys. Torrents raged through their giant rifts and foamed among grey stones. Among the mountains native tribes made their homes.

From Ilolo the track fell easily through the bush for three or four miles. Then it plunged down mountainsides through dense forests where afternoon rains drummed into the green canopy above it. There was a sound of water rushing far below. There was a twilight gloom among the trees and in the depths. There was a brawling stream and a bridge of moss-grown logs and stones. After that the track climbed a short distance up a steep slope to the village of Uberi round which mists swirled in the mornings and evenings. From Uberi to Ioribaiwa it was a hard day’s walk. The track toiled up a long mountainside. It was smooth and treacherous, hemmed in by dark trees, beaten upon by rain. It seemed to pause on the crest before it leaped down the other side of the mountain by dim ways to pass over Imita Ridge, and so into the bed of a rushing stream along which it splashed for about three miles. It climbed out of the stream on to a spur of sunlit kunai grass and upwards to the crest of the 4,000-foot Ioribaiwa Ridge. From Ioribaiwa to Nauro was a shorter day but still hard going. The track went down and up again until it overlooked Ioribaiwa from the Nauro side. From that point on to Nauro there were some hours of slippery walking generally downwards but with stretches of hard climbing over ridges and spurs. Nauro lay in a pleasant valley on the edge of the Brown River. Menari was some hours farther on. The track to it first passed along the river valley through bush which dripped with rain and over carpets of dead leaves which were soundless underfoot. From the valley it strained up and over a towering mountain and fell swiftly

down on to the flat ground where Menari lay. Leaving Menari it began the long, upward climb towards the crest of the main Owen Stanley Range by way of precipitous slopes and broken ridges. Often torrents of rain beat a dull tattoo against the broad leaves which roofed much of it. Near Efogi it broke out into the open country of a large river valley in which the village was sited. On the opposite side of the valley Kagi seemed almost to hang from the open mountainside, clearly seen through the thin mountain air but still a weary climb distant. Above it rose the main crest line of the range. The track passed over it at about 6,500 feet through a wide gap on either side of which, as far as the eye could reach, the broken skyline rose some thousands of feet higher into the clouds or lost itself in swirling mist. Here the moss forests—soft and silent underfoot—began. Streamers of moss hung from the trees.

After crossing the crest of the range above Kagi the track dropped easily enough through the bush and over the moss for an hour or two. But then its downward trend grew quickly steeper and steeper. The ground fell away precipitously on either side, dense bush pressed in, the track seemed almost to plunge headlong so that a walker slid and fell and clutched at hanging branches for support. In the silence of the bush and the moss there first welled and then rushed the roar of a torrent far below. High on moss-covered logs the track edged across a number of feeder streams, and then, suddenly, broke out on to the brink of rushing, twisting water thick with white and yellow spume, boiling in whirlpools round grey stones as big as small houses and disfigured with moss and pallid fungus.

This was Eora Creek. It rose high on the northern slopes of the mountains east of Kagi. Its course determined the way of the track from the top of the range down to Kokoda. Where the two met was the beginning of a gigantic V-shaped rift through which the waters raged down to the Yodda Valley, tearing deeper and deeper into the bases of the mountains as they did so until the sides of the V rose in places a full 4,000 feet on either side of the torrent, so steeply that in places they had to be climbed almost hand over hand.

The way ahead which the track now followed did not lead upwards, however, but, clinging like a narrow shelf to the left hand side of the V, followed the torrent along until, after about another hour’s walk it dropped again to the very edge of the water and crossed it. (This point was to become well known during the fighting in the mountains as Templeton’s Crossing.) A small cluster of huts which formed the village of Eora Creek lay about three hours’ walk farther on. The track to the village climbed high along the right bank until the roar of the torrent could be heard no more. Then a ridge thrust down to the creek like a sharp tongue and the track followed its narrow crest from which both sides fell away like a precipice. As the track descended there came from the right the distant whisper of a tributary torrent unseen in the mountain depths below, rushing to join Eora Creek whose muted roar was being borne up from the left. Suddenly the track went over the point of the spur, plunging and

slipping down an almost sheer slope which ended in a flat platform (the site of the few huts of Eora Creek village) overhanging the creek below which filled the air with sound. Below raged a whirlpool formed by the junction of the two creeks, a turbulence spanned only by slippery logs. The track crossed these and continued on for about two more hours of walking to Alola, climbing the left hand side of the V. High along a narrow pinch which clung about 2,000 feet above the creek bed it made its way to the village of Isurava. From Isurava it ran steadily downhill for about two hours with sharp rises over spurs which it crossed at right angles and quick, slippery descents down the other sides of them. It still hung to the side of the valley, was broken by juts of pointed rock, tangled with masses of roots which wove through it, splashed through little streams and passed by waterfalls. So it came to the village of Deniki, whence the Yodda Valley came into sight below, stretched out like a garden, the Kokoda airstrip plainly to be seen, the Kokoda plateau thrust like a tongue from the frowning mountain spurs. Into this green valley the track quickly descended, crossed it in about three hours of walking, leaving the bleakness of the mountains behind and running into steamy warmth, and came to Kokoda itself.

When the Japanese first landed in Papua there was much talk of “the Kokoda Pass”. But there was no pass—merely a lowering of the mountain silhouette where the valley of Eora Creek cut down into the Yodda Valley south of Kokoda.

From Kokoda the track slipped easily down towards the sea for three full days of hot marching. First it passed over undulations fringed by rough foothills and covered with thick bush. It forded many streams, passed through the villages of Oivi and Gorari, went on down to the Kumusi River which, deep and wide and swift, flowed northward and then turned sharply east to reach the sea between Gona and Cape Ward Hunt.

This was the country of the fierce Orokaivas, unsmiling men with spare, hard, black bodies and smouldering eyes. They were still greatly feared by all their neighbours although it was many years since Europeans first came and forced peace upon them. They suffered at the hands of the Yodda Valley gold-seekers at the end of the nineteenth century and the severity of the magistrate Monckton at the beginning of the new century, and it was said that they had not forgiven either occasion. Their kinsmen, the coastal Orokaivas farther on, were of the same type.

The track crossed the Kumusi by a bridge suspended from steel cables. The place of crossing came thus to be known as Wairopi (the “pidgin” rendering of “wire rope”). A little farther on, in the vicinity of Awala, began a network of tracks which passed over tropical lowlands through or past Sangara Mission and Popondetta into spreading swamps and thus reached the coast on which were the two little settlements of Buna and Gona—the former the administrative headquarters of the district, the latter a long-established Church of England mission.

Up to July 1942 Australian military interest in this lonely coast and the

even lonelier track which linked it with Port Moresby was of slow growth. On 2nd February Major-General Rowell, then Deputy Chief of the General Staff, had signalled Major-General Morris:

Japanese in all operations have shown inclination to land some distance from ultimate objective rather than make a direct assault. This probably because of need to gain air bases as well as desire to catch defence facing wrong way. You will probably have already considered possibility of landing New Guinea mainland and advance across mountains but think it advisable to warn you of this enemy course.

Morris, with a difficult administrative situation on his hands, only meagre and ill-trained forces at his disposal and more likely military possibilities pressing him, that month sent a platoon (Lieutenant Jesser) of the Papuan Infantry Battalion to patrol the coast from Buna to the Waria River, the mouth of which was about half-way between Buna and Salamaua, and watch for signs of a Japanese approach.

On 10th March a Japanese float-plane swept over Buna about 11 a.m., bombed and machine-gunned two small mission vessels there, then settled on the water. However, it was promptly engaged with rifle fire by Lieutenant Champion,1 the former Assistant Resident Magistrate, and the small group with him, who were staffing the Administration and wireless station on the shore, and it quickly took the air again.

At the end of March the Combined Operations Intelligence Centre, in an assessment of the likelihood of Japanese moves to occupy the Wau–Bulolo area after the seizure of Lae and Salamaua, had suggested the possibility of a landing at Buna with a view to an overland advance on Port Moresby. But little serious consideration seems to have been given to this suggestion.

The Japanese expedition against Port Moresby, turned back by the Allied naval forces in the Coral Sea, had underlined the need to reinforce the troops and air squadrons in New Guinea. On 14th May MacArthur wrote to Blamey that he had decided to establish airfields on the South-east coast of Papua for use against Lae, Salamaua and Rabaul, that there appeared to be suitable sites between Abau and Samarai, and he wished to know whether Blamey had troops to protect these bases. (The 14th was the day on which the ships containing the 32nd American Division and the remainder of the 41st arrived in Melbourne.) Blamey had already ordered the 14th Brigade to Port Moresby and it embarked at Townsville on the 15th. He replied, on the 16th, that he could provide the troops, and MacArthur, on the 20th, authorised the construction of an airstrip in the Abau–Mullins Harbour area. At the same time he ordered that the air force bring its squadrons at Moresby up to full strength and that American anti-aircraft troops be sent from Brisbane to the forward air-fields at Townsville, Horn Island, Mareeba, Cooktown and Coen.

The 14th Brigade, with only about five months of continuous training behind it (although most of the individual men had had more than that), was thus the first substantial infantry reinforcement to reach Moresby since

General Sturdee had sent two battalions there, making a total of three, on 3rd January, four months before the Coral Sea battle.2 When the inexperienced 14th Brigade was sent forward there were, in eastern Australia, three brigades of hardened veterans—the 18th, 21st and 25th—but unwisely none of those was chosen.

On 24th May Morris was instructed to provide a garrison for the new airstrip but was told that if the enemy launched a major attack it was to withdraw after having destroyed all weapons and supplies. A reconnaissance of the proposed area, however, had led to the conclusion that it was unsuitable; Morris, on the advice of Elliott-Smith, then of the Papuan Infantry Battalion, emphasised that there were better sites at Milne Bay and on 12th June GHQ authorised the construction of an airfield there.

MacArthur could now proceed with greater confidence because of a great defeat that the Japanese Navy had suffered in another hemisphere.

After their occupation of Tulagi on 3rd May the Japanese quickly spread to the neighbouring island of Guadalcanal and began the construction of an airfield there. On 5th May the Japanese High Command had ordered Admiral Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, to take Midway and the Aleutians. On 18th May, as mentioned

On 1st November 1943 Curtin wrote a letter to MacArthur in the course of which he referred to the effects of the return of the AIF and the arrival of the United States Forces in Australia and said: “The additional forces enabled a transformation to be made in your strategy from a defensive one on the mainland, to a defence of the mainland from the line of the Owen Stanley Range.”

earlier, it issued orders for attacks on New Caledonia, Fiji, Samoa and Port Moresby to cut communications between America and Australia.

Early in June, eluding an American naval force which had been sent into those cold seas to intercept them, the Japanese landed at Kiska and Attu in the west of the Aleutians. At the same time they made their advance against Midway.

Although, after the encounter, they had lost touch with the heavy Japanese forces which they had met in the Coral Sea, the American naval staffs had correctly deduced from their Intelligence that the next major Japanese move would be against Midway, and the Aleutians. They therefore quickly concentrated near Midway a fleet consisting of 3 carriers (the Enterprise, Hornet and Yorktown—the last-named having been hastily patched up), 7 heavy cruisers, 1 light cruiser, 14 destroyers and 25 submarines. Marine Corps and army aircraft were based on the island itself.

On the morning of 3rd June Japanese forces, on an easterly course, were sighted several hundred miles South-west of Midway. Army aircraft engaged them. Next morning Japanese aircraft raided the island and the Americans located the centre of the concentration of their enemies. The Japanese were out in strength with a striking force of 4 carriers, 2 battleships, 2 cruisers and 12 destroyers. A support force and an occupation force followed, the former containing 2 battleships, 1 heavy cruiser, 4 cruisers and 10 destroyers, the latter consisting of transport and cargo vessels escorted by 3 heavy cruisers and 12 destroyers. The Americans attacked with both land-based and carrier-borne aircraft during the 4th and the following two days in an engagement which was primarily an air-sea one (though not entirely so as in the Coral Sea).

When the smoke of the battle cleared it was obvious that the Japanese had suffered very heavily. They lost their four carriers, one cruiser and one destroyer, while a number of the other ships were damaged. They lost probably about 250 aircraft; the Americans lost 150 aircraft and the aircraft carrier Yorktown.

This decisive battle redressed the balance of naval power in the Pacific which had been so dangerously shaken for the Americans at Pearl Harbour; it marked the point at which the Allies might begin to turn from defensive to offensive planning. Despite this, it did not yet mean that the Allies had command of the Pacific seas nor alter the fact that there were dangerous groupings of Japanese forces available for operations particularly in the South-West Pacific.

These had already begun to concentrate.3 Lieutenant-General Harukichi Hyakutake’s XVII Army was the instrument being prepared. Its main force was then being drawn from the 5th, 18th and 56th Divisions, which

were concentrated mainly at Davao after the end of the fighting in the Philippines; but Hyakutake was gathering elements also from Java, and Major-General Tomitaro Horii’s South Seas Force, built strongly round the 144th Regiment, was still at Rabaul after its successful assault there in January and the capture of Salamaua by one of its battalion groups. Formidable naval support for Hyakutake was planned to come from Vice-Admiral Kondo’s i (13 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, 24 destroyers), Vice-Admiral Nagumo’s First Air Fleet (7 carriers, 11 destroyers) and Vice-Admiral Mikawa’s fleet which included the four battleships Hiyei, Kirishima, Kongo and Haruna.

A few days after the Midway battle indications of a renewed thrust by the enemy in the South-West Pacific were accumulating. On 9th June MacArthur wrote Blamey that there was increasing evidence of Japanese interest in developing a route from Buna through Kokoda to Port Moresby and that minor forces might try to use this route either to attack Port Moresby or to supply forces advancing by sea through the Louisiades.4 He asked what Morris was doing to protect the Kokoda area.

On 6th June Morris had given the Papuan Infantry Battalion (30 officers and 280 men) the task of reconnoitring the Awala–Tufi–Ioma area. On 20th June General Blamey ordered him to take steps to prepare to oppose the enemy on possible lines of advance from the north coast and to secure the Kokoda area. Thereupon on 24th June Morris ordered that the 39th Battalion (less one company), the PIB, and appropriate supply and medical detachments should constitute Maroubra Force, with the task of delaying any advance from Awala to Kokoda, preventing any Japanese movement in the direction of Port Moresby through the gap in the Owen Stanleys near Kokoda, and meeting any airborne landings which might threaten at Kokoda or elsewhere along the route. One company of the 39th Battalion was to leave Ilolo on 26th June.

Many changes had taken place in the 39th Battalion during its five months in Papua. Some of the men had had experience of action against raiding Japanese aircraft. At the airfield at the Seven Mile, one of the principal targets of the raiders, they had claimed at least one Zero as a “certain kill” and others as “probables”. Reinforcements which arrived in March were all AIF enlistments (and were resentful at having to serve with a militia unit). Brigadier Porter,5 who had taken over the 30th Brigade on 17th April, had driven the battalion hard in common with the other units of the brigade. Porter was active, keen and receptive of new ideas. He had been an original officer of the 2/5th Battalion and later commanded the 2/31st in the Syrian campaign. While he was critical of his brigade in some respects he considered that they had been shabbily treated in many ways and worked hard to overcome disadvantages which they suffered. By

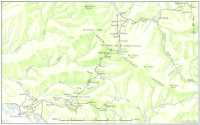

The Kokoda Track

the beginning of July he had sent back to Australia about 20 officers from his brigade and had managed to get forward approximately 30 AIF officers, and AIF men who were commissioned in his units. The 39th Battalion received a strong leavening of these and a survivor of the 2/22nd Battalion, Lieut-Colonel W. T. Owen, took over command. After the reshuffle the only 1914–18 War veteran remaining in commissioned rank was Captain Templeton,6 who retained “B” Company. Templeton was reputed to have served in submarines in the earlier war and had fought in Spain during the Civil War. When the new war came he was rejected as medically unfit for the AIF because he had “flat feet” and consequently he burned to show his fitness at almost any cost. Among his troops he was known affectionately as “Uncle Sam”.

With this battalion preparing to cross the range Morris was faced with new problems. He still had the defence of the Port Moresby area to worry him and had been understandably loath to throw off detachments which would weaken his main force.7 But the problem which was now to loom larger than any others was that of supply. Because of that problem, if for no other reasons, Morris considered the Kokoda Track impassable for any large-scale military movements; and that in such country the force with the longer supply line would be at a very great disadvantage.

Therefore (he had said) even if the Japanese do make this very difficult and impracticable move, let us meet them on ground of our own choosing and as close as possible to our own base. Let us merely help their own supply problem to strangle them while reducing our supply difficulties to a minimum.

Now, however, he was in a position where, if his men met the enemy, the very advantage he sought would not only be denied them but, initially at least, would rest with their opponents. The Australians would be separated from their base by roadless mountains which were impassable to wheeled vehicles. They had no transport aircraft based at Port Moresby. For their main supply line they would have to depend upon native carriers.

Porterage by natives was the traditional method of transporting supplies and equipment in New Guinea from the time when Europeans first began thrusting inland from the coasts. Although the use of natives for carrying was almost always arranged on a casual and day-to-day basis, the general recruitment of native labour and the conditions under which such labour might be employed were rigidly prescribed in both Papua and the Mandated Territory. Regulations limited the number of natives who might be recruited from any area at any time, provided for employment, in most cases, in accordance with contracts which obliged employers to return indentured labourers to their villages at the end of a limited term of service and imposed detailed conditions of service which employers must observe.8

Penal sanctions (gaol sentences or fines) could be imposed to force the natives to fulfil the terms of their contracts. At the beginning of 1942 there were about 10,000 indentured labourers in Papua and 35,000 in the Mandated Territory.

On 15th June the hand of military authority fell heavily on the native labour force of the two Territories. Morris invoked the National Security (Emergency Control) Regulations to terminate all existing contracts of service in Papua and New Guinea and provide for the conscription of whatever native labour might be required by the Services. He ordered that “the Senior Military Officer or any District Officer” might employ any native upon such work and subject to such conditions not inconsistent with the order as he might think fit; that all natives so employed should enter into a contract of employment for a period not exceeding three years; that no labourer duly engaged for or in any such employment should:

1. Neglect to enter into a contract of employment;

2. After he has entered into such contract –

(a) desert from such employment;

(b) absent himself without leave;

(c) refuse or neglect to perform any work which it is his duty to perform;

(d) perform any work in a careless or negligent manner.

Rates of pay were set at not less than 8/- and not more than 15/- a month for “skilled labour”; not less than 8/- and not more than 10/- a month for “heavy labour”; from 5/- to 10/- a month in certain other circumstances. Food and certain personal necessities were to be provided.

On 3rd July Lieutenant Kienzle9 arrived at Ilolo with orders to take charge of all Angau personnel and native labour working on the construction of a road from Ilolo to Kokoda. The work was to be completed by the end of August. But Kienzle was not optimistic enough to hope that he might achieve this. In civil life he was a rubber planter in the Yodda Valley and he was one of the few men in Papua with an intimate knowledge of the country between Ilolo and Kokoda.

At Ilolo he found pack animals at work and about 600 native labourers. The native labourers (wrote Kienzle afterwards) were:

very sullen and unhappy. Conditions in the labour camp were bad and many cases of illness were noted. Desertions were frequently being reported. The medical side was in the capable hands of Captain Vernon,10 AAMC. I commenced reorganising and allotting labour to various jobs. One of the first tasks was to erect quickly sufficient clean, dry buildings to house the labour adequately. Plenty of native material close at hand enabled this to be done rapidly. The consideration shown and an address to the natives had the effect of bringing about a better understanding and appreciation of the task ahead.11

The pack animals were horses and mules of the 1st Independent Light Horse Troop (1 officer and 20 men). This troop had been working round

Port Moresby on track reconnaissance and the location of crashed aircraft and began to pack between the jeep-head and Uberi on 26th June. When they moved up to the beginning of the Kokoda Track they sent six men to trap wild horses in the Bootless Inlet area and break them in. Until the arrival of these horses, however, the main body impressed horses, mules and pack saddlery from the plantations on the Sogeri plateau. They soon found that mules were the best pack animals for their purposes, with the small brumbies from Bootless the next best. The bigger feet of the plantation horses were ill-suited for the narrow mountain tracks. The men found also that the narrowness of these tracks made control of the animals difficult and so they taught them to follow one another in single file, one man riding at the head of the column and one at the rear. As standard practice, loads were made up to 160 pounds for each animal, and to save weight, supplies were packed in bags—an expedient which also facilitated the transfer to native carriers at the end of the packing stage.

At Ilolo Kienzle also found Templeton’s company of the 39th Battalion waiting for someone to guide them across the mountains. At once he began to organise carriers and stages for their march. On 7th July he sent Sergeant-Major Maga, of the Royal Papuan Constabulary, to Ioribaiwa with 130 carriers to erect a staging camp there. On the 8th he led Templeton’s men out from Uberi, with 120 natives carrying rations and the soldiers’ packs. At Ioribaiwa they found that Maga had done his work well and had grass shelters ready for the carriers and tents for the troops. They went on to Nauro the next day, with 226 carriers. On the 10th, while the soldiers rested at Nauro, Kienzle sent forward one of his own men, a native policeman and 131 carriers to Efogi carrying rice and Australian food. On the 12th he led his charges into Kagi and found Lieutenant Brewer,12 the Assistant District Officer at Kokoda, and 186 carriers, waiting there. Thereupon he sent his own carriers back along the way they had come with orders to start building up supplies at the various depots of which the foundations had already been established along the track. (He had formed the opinion that it was best to have the carriers based on definite points with the task of carrying only over the next two stages.) By the 15th the troops had reached Kokoda. Thence Kienzle, after gathering supplies of food for the carriers, mainly sweet potatoes and bananas from his own plantation at Yodda, and handing over to Templeton his own personal stores which were still there, started back again towards Port Moresby. As he went he noted:

The establishment of small food dumps for a small body of troops was now under way as far as Kagi. This ration supply was being maintained by carriers over some of the roughest country in the world. But with the limited number of carriers available maintenance of supplies was going to 13e impossible along this route without the aid of droppings by plane. A carrier carrying only foodstuffs consumes his load in 13 days and if he carries food supplies for a soldier it means 61 days’ supply for both soldier and carrier. This does not allow for the porterage of arms, ammunition, equipment, medical stores, ordnance, mail and dozens of

other items needed to wage war, on the backs of men. The track to Kokoda takes 8 days so the maintenance of supplies is a physical impossibility without large-scale cooperation of plane droppings.13

By the time these comparatively modest plans for defence against any landings which might take place on the north coast had thus developed, events elsewhere, and planning on the highest Allied levels, had resulted in far wider plans being formulated in relation to that area.

For the Allies the victory at Midway had shed a ray of light upon an otherwise sombre scene. June was elsewhere a month of great anxiety. The Allied forces had been driven out of Burma and there were fears that China might lose heart. In North Africa Tobruk had been surrendered on 21st June and the Eighth British Army had fallen back to El Alamein. Malta was facing starvation. In Russia the defending army had been pushed back across the Don and now faced the German summer offensive. In June, losses of British, Allied and neutral shipping reached a higher total than in any previous month.

One outcome of the reverses in the Middle East was that the prospect of obtaining the return of the 9th Division to Australia became remote. Late in June it was hurried from Syria to reinforce the Eighth Army, and by 7th July was in action. Moreover in June the 16th and 17th Brigades were still in Ceylon, so that of eleven brigades that Australia had sent overseas only four had returned. When, on 2nd March, Mr Curtin had offered to allow the 16th and 17th Brigades to be added to the garrison of Ceylon, it was on the understanding that they would soon be relieved by part of the 70th British Division, due in a few weeks. Mr Churchill, however, intended to hold them in Ceylon for a longer period; on 4th March he had written to the Chiefs of Staff in London that the brigades

ought to stay seven or eight weeks, and shipping should be handled so as to make this convenient and almost inevitable. Wavell will then be free to bring the remaining two brigades of the 70th Division into India and use them on the Burma front. ...14

The brigades had been in Ceylon almost five weeks when, on 28th April, Mr Curtin, on General MacArthur’s advice, asked Mr Churchill to divert to Australia a British infantry division rounding the Cape late in April and early in May, and an armoured division that was to round the Cape a month later. These, he proposed, should remain in Australia only until the return of the 9th Division and the 16th and 17th Brigades. Churchill replied that this would involve “the maximum expenditure and dislocation of shipping and escorts”. He hoped to relieve the brigades in Ceylon with two British brigades about the end of May. At the end of June, however, the 16th and 17th Brigades were still in Ceylon. On the 30th of that month the Australian Government, having agreed not to continue seeking the return of the 9th Division for the present, again asked for the return of the 16th and 17th Brigades. At length, having been in

Ceylon not “seven or eight weeks” but sixteen, the brigades sailed from Colombo on 13th July. They disembarked at Melbourne between 4th and 8th August.

In the Central Pacific the success at Midway was followed by the reinforcement of the garrison of the Hawaiian Islands. By early October there were four divisions there—a relatively heavy insurance when it is recalled that there were only four American divisions west of Hawaii.

In the South-West Pacific Midway was followed by an ambitious proposal by General MacArthur. On 8th June he suggested to General Marshall that he should attack in the New Britain–New Ireland area preparatory to an assault on Rabaul. To achieve this he asked for an amphibious division and a naval force including two carriers. With it he would recapture the area “forcing the enemy back 700 miles to his base at Truk”.15 On the 12th Marshall presented a plan to Admiral King. It required a marine division to make the amphibious assault and three army divisions from Australia—presumably the 32nd and 41st American and 7th Australian—to follow up; and three carriers and their escort. To succeed, Marshall emphasised, the operation must be mounted early in July. In retrospect, these plans reveal an inadequate appreciation by the Staffs concerned of the complexity of amphibious operations on the scale proposed, the unreadiness of the American Army divisions, and the naval implications. The Navy Staffs objected on the grounds that they would have to expose their carriers to attack by land-based aircraft in a narrow sea where they would have no protection from their own land-based aircraft, and that MacArthur would be in command.

Finally King informed Marshall of his own plan for a drive Northwest from the New Hebrides by forces under naval command. MacArthur protested at the prospect of “the role of Army being subsidiary and consisting largely of placing its forces at the disposal and under the command of Navy or Marine officers”.16 The outcome was a directive by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, issued on 2nd July, their first governing the strategy of the war in the Pacific:

The objective of this directive is the seizure and occupation of the New Britain–New Ireland–New Guinea area, in order to deny those regions to Japan. Task I is the conquest and garrisoning of the Santa Cruz Islands, Tulagi and adjacent positions; Task II involves taking and retaining the remainder of the Solomons, Lae and Salamaua, and the North-eastern coast of New Guinea; and Task III is the seizure and occupation of Rabaul and adjacent positions in New Ireland–New Guinea area. ... Forces to be committed are ground, air and naval strength of SWPA, at least two aircraft carriers with accompanying cruisers and destroyers, the SOPAC [South Pacific] Amphibious Force with the necessary transport divisions, Marine air squadrons and land based air in SOPAC, and Army occupational forces in SOPAC for garrisoning Tulagi and adjacent island positions plus troops from Australia to garrison other zones. Command for Task I will be a CTF [Commander Task Force] designated by the C-in-C PAC [Commander-in-Chief Pacific] assumed to be Admiral Ghormley who is expected to arrive in Melbourne for conferences.

C-in-C SWPA is to provide for interdiction of enemy air and naval activities westward of the operating area. Tasks II and III will be under the direction of C-in-C SWPA.

Both Ghormley and MacArthur protested that the date (early August) projected for the embarkation upon Task I, did not allow them sufficient time for preparations. On 8th July they sent a joint dispatch to Admiral King (the American naval Commander-in-Chief) and General Marshall.

The opinion of the two commanders, independently arrived at, is that initiation of this operation, without assurance of air coverage during each phase, would be attended with the greatest risk (demonstrated by Japanese reverses in the Coral Sea and at Midway). The operation, once initiated, should be pushed to final conclusion, because partial attack leaving Rabaul still with the enemy, who has the ability to mass a heavy land supported concentration from Truk, might mean the destruction of our attacking elements. It is our considered opinion that the recently developed enemy positions, shortage of airfields and planes and lack of shipping make the successful accomplishment of the operation very doubtful.

The Chiefs of Staff replied, however, that not only did the threatened complete occupation of the Solomon Islands group offer a continual threat to the mainland of Australia and to the 8,000-mile-long sea route to the United States, but also, through the building of air bases on Guadalcanal, to the proposed establishment of American bases at Santa Cruz and Espiritu Santo. They appreciated the disadvantages of undertaking Task I before adequate forces and equipment were available for continuing with Tasks II and III, but it was imperative to stop the enemy’s southward advance.

Ghormley was thus committed to a task he mistrusted and MacArthur’s own forebodings were soon to be realised.

In July MacArthur had begun moving forces nearer to the threatened areas. Early in the month he ordered the 41st American Division northward from Melbourne to Rockhampton and the 32nd from Adelaide to Brisbane. They were to form a corps, the command of which was given to Major-General Robert C. Richardson, but Richardson objected to serving under Australian command and was replaced by Major-General Robert L. Eichelberger of I Corps.17 On 20th July MacArthur moved his own headquarters from Melbourne, 2,000 miles from Port Moresby, to Brisbane, 1,300 miles from it.

On the 15th July he had issued an outline plan for the development of an Allied base in the Buna area, as one of his first steps in preparing to carry out the directive of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Australian infantry and American engineers were to move overland from Port Moresby “to seize an area suitable for the operations of all types of aircraft and secure a disembarkation point pending the arrival of sea parties”. A force of approximately 3,200 was to be established at Buna early in August. The

rapid development of airfields for use by both fighter and bomber aircraft was to follow.

The development of this base would complement preparations which were already advanced for the construction of airfields at Milne Bay—part of the third step of a plan which MacArthur was to describe to the American Chiefs of Staff on 2nd August:

My plan of operations to prevent further encroachment in New Guinea has been and still is affected by transportation problems and lack of assurance of naval assistance to protect supply routes; before augmenting defences in New Guinea it was necessary to build a/ds [aerodromes] progressively northward along the Northeast coast of Australia, since the then existing development at Moresby was too meagre and vulnerable to permit keeping AF [Air Force] units therein; first step was to develop the Townsville–Cloncurry area; engineers and protective garrisons and finally AF units were moved into that area and Moresby used as an advanced stopping off a/d; the second step was then instituted by strengthening Port Moresby garrison to two Australian infantry brigades and miscellaneous units, moving in engineers and AA units to build and protect a/ds and dispersal facilities, developing fields further northward along the Australian mainland through York Peninsula and movement forward thereto of protection garrisons and air elements; this step was largely completed early in June although some of the movement of engineers into undeveloped areas of the York Peninsula and the construction of airfields was incomplete, but rapidly progressing; the first two steps were primarily defensive, the succeeding steps were to prepare for offensive executions; lack of amphibious equipment limited offensive steps to infiltrations; the third step was to build airfields at Merauke, 150 miles NW of Torres Strait, to provide a protective flank element to the N of that strait; to secure the crest of the Owen Stanley Range from Wau southward to Kokoda; to provide an airfield at Milne Bay to secure the southern end of the Owen Stanley Range bastion.

On 25th June a small force from Port Moresby had disembarked at Milne Bay to protect the new airfield site, and on the 29th a company of American engineers had landed. These troops consisted principally of two companies and one machine-gun platoon of the 55th Battalion, the 9th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery (less one troop) with eight Bofors guns, one platoon of the 101st United States Coast Artillery Battalion (AA) with eight .5-inch anti-aircraft guns, No. 4 Station of the 23rd Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery with two 3.7-inch guns, and one company of the 46th United States Engineer Battalion. Their task was to construct and defend at Gili Gili an airstrip from which heavy bombers could operate and, the day after they landed, they were told that the work must be completed at the earliest possible moment, the target date being set at the 20th July. They had not been long at work, however, before it was decided to build up a much stronger garrison. So, on 11th July, Brigadier John Field18 arrived at Milne Bay with advanced elements of his 7th Brigade Group. He was to command “Milne Force” which, in addition to the troops already in the area, would consist mainly of the 9th, 25th and 61st Battalions of his own brigade, Australian artillery and engineers (4th Battery of the 101st Anti-Tank Regiment, 6th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery, 9th Light Anti-Aircraft

Battery, 24th Field Company), and an additional American anti-aircraft battery and “Service” units. As soon as the airfield was ready one Australian fighter squadron would be sent to Milne Bay. Field was to operate directly under Blamey’s headquarters: he would not be subject to control by New Guinea Force, and was to exercise “operational control” over all land, sea and air forces in his area.

His task was defined in the following terms:

(a) To prepare and defend an aerodrome at the upper end of Milne Bay for the operation of all types of aircraft.

(b) To preserve the integrity of South-east New Guinea by

(i) Preventing hostile penetration in the area.

(ii) Denying, by air attack, Japanese use of the sea and land areas comprising the D’Entrecasteaux, Trobriand and Louisiade Islands Groups.

(c) To maintain active air reconnaissance of the above areas in conjunction with the Allied Air Forces.19

The maintenance of Milne Force would be an American responsibility.

Despite great natural difficulties significant advances were being made at Milne Bay as July went on. If the proposed Buna base could be pushed ahead rapidly the Allies would soon be set fair to fend off any Japanese attempts to land in Papua. But their enemies forestalled them.

About 2.40 p.m. on 21st July a float-plane machine-gunned the station at Buna. Perhaps two hours and a half later a Japanese convoy, reported at the time to consist of 1 cruiser, 2 destroyers and 2 transports, appeared off the coast near Gona. It was part of a concentration of shipping which Allied airmen had detected gathering at and moving south from Rabaul during the preceding days. About 5.30 p.m. the Japanese warships fired a few salvos into the foreshores east of Gona. The convoy was attacked first by one Flying Fortress without result and then by five Mitchell bombers which claimed to have scored a direct hit on one of the transports. Air attacks continued as landings began on the beaches east of Gona. Darkness then shut off the ships from further attack and the whole scene from further observation. At 6 next morning a cruiser and two destroyers shelled Buna, and the landings near Gona, which had apparently been going on through the night, were seen to be continuing at 6.30. The defending aircraft reported a direct hit on the transport which was thought to have been hit the previous day, and the sinking of a landing barge. Meanwhile more warships and transports had been sighted off the Buna–Gona coast.

As a result of the landings Morris was instructed on the 22nd to concentrate one battalion at Kokoda immediately, to prevent any Japanese penetration South-west of that point and patrol towards Buna and Ioma. He was also told that arrangements were being made to fly across the mountains 100,000 pounds of supplies and ammunition but that it was unlikely that any troops could be similarly transported. On the same day he ordered Lieut-Colonel Owen of the 39th Battalion to leave for Kokoda

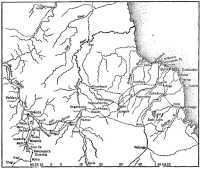

Kokoda–Buna area

on the 23rd and take command of Maroubra Force. If Owen failed to block a Japanese advance to Kokoda he was to retire to previously prepared positions in the vicinity and prevent any further penetration towards Port Moresby. At the same time (so deep rooted was the belief in the effectiveness of the mountains as a barrier against invasion) he was told that an attempt to move overland against Port Moresby was not likely and that the Japanese intentions were primarily to establish an advanced air base in the Buna–Gona area.

In the vicinity of Buna and Gona themselves there was inevitable confusion after the attacks. At Buna, Lieutenant Champion, and Lieutenant Wort20 of the Papuan Infantry Battalion with some of his men, watched the approach of the attackers. They left Buna for Awala about 6 p.m. At Gona the Reverend James Benson of the Anglican Mission there and two mission sisters waited until the landings were actually beginning before they also took the track towards Kokoda with a few possessions hastily thrown together.

Meanwhile Major Watson of the Papuan Battalion was uncertain what was happening. On the day the landings began 105 of his natives, under

three Australian officers and three Australian NCO’s, were spread from Ioma to the Waria; Lieutenant Smith21 and Sergeant Hewitt22 with 30 natives were in the vicinity of Ambasi, near the mouth of the Opi River, Wort’s detachment was in the Buna area; the remainder of Watson’s force was round Kokoda–Awala. He himself, with Captain Jesser, was moving down from Kokoda to Awala. Late that afternoon and early next morning he had reports from Captain Grahamslaw,23 the senior Angau officer in the area, of Japanese action off Buna but the reports were necessarily vague and Grahamslaw himself had gone forward towards Buna before Watson arrived at Awala early in the morning of the 22nd.

Grahamslaw took with him Lieutenant McKenna,24 Warrant-Officer Yeoman25 and 9 police. At Isagahambo Warrant-Officer Bitmead,26 assisted by Warrant-Officer Barnes,27 was running a hospital with 300 native patients in it. Grahamslaw told Bitmead to pack his drugs and fall back to Awala. Bitmead, however, said that he would send Barnes back while he himself remained to do what he could for his patients until the last moment. He said that he had a guard posted about a mile down the road and would thus have sufficient warning of the approach of the Japanese. Grahamslaw and his party then pushed on towards the coast but were surprised by the advancing Japanese soon after midday.

About 9.30 a.m. Watson had received news from Wort at Awala, and then thrust forward patrols, the strongest consisting of 35 natives under Jesser. These left Awala at 11.15 a.m. on the 22nd and, early in the afternoon, came up with Bitmead who told them that he had natives scouting along the Sangara-Buna track and felling trees to block the road. The patrol reached Sangara but later withdrew again before the approach of the Japanese who had, unknown to Jesser, engaged Grahamslaw earlier in the day.

That night Lieutenant Chalk28 took four men into Sangara and confirmed that the Japanese had camped there. Jesser’s party then withdrew to Hagenahambo, tearing up small log bridges and obstructing the road as they went, for the Japanese were using bicycles. About 4 p.m. next day (the 23rd) Chalk was in position approximately 1,000 yards east of Awala when the Japanese appeared moving behind a screen of natives. Chalk’s men engaged them; the Japanese, armed with mortars, machine-

guns and a field piece accepted action immediately it was offered. Chalk withdrew and most of his native soldiers melted away into the bush.

Just at this time the first of the 39th Battalion men (Lieutenant Seekamp’s29 platoon) were arriving as a result of quick movement by Captain Templeton. On the 21st Templeton had been in the Buna area where he had gone on a reconnaissance and to ensure that the unloading of stores which had come round by sea had been completed. He had hurried back towards Awala where he had arrived next day. He had ordered Seekamp’s platoon forward to Awala. He then had his second platoon between Awala and Kokoda and his third at Kokoda for the defence of the airfield there. He himself returned towards Kokoda to meet Owen.

Watson now ordered Seekamp to hold at Awala for thirty minutes while the remnants of the Papuan Battalion established themselves at Ongahambo, two or three miles back along the track. Some confusion followed, however, and Seekamp withdrew to Wairopi. Watson then destroyed his stores and the buildings at Ongahambo and fell back to Wairopi himself. By this time his force was woefully reduced and consisted of a few European officers and NCO’s and a mere handful of natives, the rest of the Papuans having “gone bush”.

By the early morning of the 24th Seekamp’s men and Watson’s small group were on the western side of the Kumusi and had destroyed the bridge behind them. At 9 a.m. they received a message from Templeton:

Reported on radio broadcast that 1,500–2,000 Japs landed at Gona Mission Station. I think that this is near to correct and in view of the numbers I recommend that your action be contact and rearguard only—no do-or-die stunts. Close back on Kokoda.

At 10.30 Captain Stevenson,30 Templeton’s second-in-command, arrived at Wairopi. He said that Lieutenant Mortimore’s31 platoon was waiting near Gorari. He ordered Seekamp to prepare to fight a rearguard action as he withdrew along the track and to leave a lookout on the west side of the Kumusi. About midday Jesser, tireless and intrepid, who had been scouting round the Japanese advance, swam the river and reported that the Japanese had spent the night at Awala and had made no forward move from there by 7 a.m. He reported also that he had been in touch with the mission people from Sangara, who like those from Gona, were refugees in the bush. But the Japanese were not far behind him and by 2.30 appeared on the east bank of the river. Fire was exchanged and then once more the Australians fell back and took up a position in rear of Mortimore’s men near Gorari. There Owen and Templeton found them about 2 a.m. on the 25th.

Owen decided to make a stand 800 yards east of Gorari and dispersed his Australians beside the track with some of the Papuans in the thick bush on their flanks. He himself returned then to Kokoda to meet reinforcements who were expected by air and so was not present when the Japanese walked out of the silence of the bush track into the ambush which had been laid. The Australians claimed that they shot down fifteen of their enemies before they themselves withdrew to Gorari. But the invaders were swift and determined in pursuit, and by 4.45 p.m. they were again engaging the Australians. They forced them back to Oivi—two hours’ march east of Kokoda. The Australians were very tired then and six of their men were missing.

Owen, disturbed about the state of his men and by the fact that there were no other forces between Kokoda and his “C” Company (Captain Dean32), which had left Ilolo on the 23rd and was moving up the track, asked that two fresh companies of his battalion be flown in. General Morris, however, had only two aircraft serviceable, out of four which arrived at Port Moresby on the 25th and 26th, and the best he could do was to get two aircraft in to Kokoda on the 26th, each carrying fifteen men of Lieutenant McClean’s33 platoon.

McClean, eager for action, hurried forward to Oivi with those of his men who arrived in the first lift. He was with Templeton’s two platoons and the Papuans when the Japanese attacked at 3 p.m. The attackers were halted at first by the fire of the forward section, then outflanked it and forced it back to the main positions on the plateau on which Oivi stood. The defenders then went into a tight perimeter defence of diameter about 50 yards. The two opposing groups maintained a desultory fire during the afternoon, the Japanese sometimes pressing to within a few yards of the perimeter before they were killed. About 5 o’clock Templeton went to examine the rear defences and to warn the second half of McClean’s platoon, under Corporal Morrison,34 whom he thought to be about to arrive. There was a burst of fire from the gloomy forest. Templeton did not return.35

As dusk was falling the Japanese finally encircled the tired men on the plateau and moved in for the kill. Watson, commanding both Papuans and Australians, estimated that the enemy was strongest in his rear and .that the attackers were bringing fire to bear from about twenty light machine-guns. Their shooting, he marked, was high and wild—fortunately, because he felt his force to be greatly outnumbered, although their machine-gun fire continued to hold the attackers outside the perimeter. McClean and Corporal Pike36 temporarily lessened the pressure on the rear positions

about 8 p.m. when they crawled to the perimeter edge and engaged their enemies with hand grenades. The groans and cries of pain from the victims of this sally were plainly heard within the defences, and were of different tone to the coaxing “Come forward, Corporal White!” and “Taubada me want ‘im you!” and similar invitations with which the Japanese were trying to trick the Australians out of cover.

But the militiamen were approaching a state of exhaustion. Stevenson showed Watson some of his men falling asleep over their weapons even as their enemies pressed them closely. At 10.15, therefore, guided by Lance-Corporal Sanopa (a Papuan policeman), Watson led the whole group out to the south where the fewest Japanese were thought to be. He intended to circle back across the Kokoda path and re-engage at daylight. But there was no track. It was very dark and heavy rain was falling. The men struggled towards Deniki (as easier to reach than Kokoda). They stumbled into creeks, slipped on the steep hillsides. The bush tore at them. When daylight came they were still only two miles from Oivi.

Meanwhile there had been uncertainty at Kokoda where Owen was waiting with Lieutenant Garland’s37 platoon and, among others, Brewer, who had two signallers operating his wireless set in the bush outside the settlement and had been building a supply dump at Deniki. Owen had no news of the fighting at Oivi until some of Morrison’s men reported about 2 a.m. on the 27th that Oivi had been surrounded and cut off from their approach. Later he decided that, failing more news from Oivi by 11 a.m., he would then leave for Deniki. At dawn he ordered most of his little force to withdraw. He and the few who remained then stacked into the houses as much as they could of the material they could not carry away, and at 11 a.m. set out for Deniki leaving the houses burning. To their surprise they found, when they reached Deniki, that Watson and Stevenson and most of their men had arrived there an hour or two before. Early next morning a small group of McClean’s men, who had become separated from the main force, reported in with the news that they had slept at Kokoda the previous night and that there had been no appearance of the Japanese before they left. Owen then realised that he had erred. He had told Port Moresby that he had left Kokoda and was thus cut off from supplies and reinforcements which could have been landed there (and which, in fact, were ready at Port Moresby to be sent in to him). He at once hastened to retrieve the situation. Leaving McClean and two of his sections at Deniki he hurried back to Kokoda with the balance of the 39th men and the PIB (the latter now including about 20 Papuans). All told the force numbered some 80 men.

With them went Captain Vernon, who had served as a medical officer with the 11th Light Horse in the first war. He had become an identity in Papua where he had been making a living for some years, partly as a medical officer, partly as a planter. He was deaf. Early in July he had been sent to Ilolo to act as a medical officer to the carriers there. Soon

afterwards his duties were extended to cover all the carriers along the track to Kokoda. He left Ilolo on 20th July on his first forward tour of inspection and arrived at Deniki just in time to accompany Owen on his return to Kokoda. Owen was particularly pleased to see him as there was no other doctor available at the time. Warrant-Officer Wilkinson,38 assisted by Warrant-Officer Barnes since Bitmead had sent the latter back from Isagahambo, had been doing the medical work for the forward troops up to that time. He was an “old hand” in New Guinea where he had been mining and “knocking round” from 1930 to 1940. He had served with the AIF in the Middle East and was now a member of Angau.

By about 11.30 a.m. or the 28th Owen was disposing his force round the administrative area on the extreme tip of the tongue-shaped Kokoda plateau which poked northward from the main range. The administrative area was about 200 yards from east to west at its widest and not much more from north to south. The eastern northern and western side of the plateau fell away sharply for about 70 feet to the floor of the valley of the Mambare River which flowed roughly east and west in front of the settlement. At the southern end of the administrative area a rubber plantation began and stretched over level ground back towards the mountains and Deniki. The track from Oivi ran in from the east to the tip of the plateau. As he faced down this track, along which he felt attack would come, Owen posted Garland’s platoon on his right flank with most of the Papuans on their left. Seekamp’s platoon was round the tip of the plateau with Morrison’s section on their left. Behind Morrison the regimental aid post was set up at the northern end of the rubber. Mortimore’s men dug in among the trees and astride the track to Deniki.

About midday two aircraft circled the field. Owen’s men hastened to try to remove the obstructions which they had placed there but finally, on

instructions from Port Moresby, where naturally General Morris was ill-informed about the position at Kokoda, the aircraft did not land the reinforcements they were bringing and made back the way they had come.

During the rest of the day disquieting signs of Japanese movement were seen but there was no attack. Darkness came. About 2 o’clock in the morning of the 29th the Japanese began to lay down machine-gun and mortar fire. Half an hour later, through the moonlight, they launched an emphatic attack up the steep slope at the northern end of the area where Seekamp was waiting. The attack pressed in. It was close fighting with the Australians beating the attackers back with grenades. Owen was in the most forward position at the most threatened point in Seekamp’s sector, on the very lip of the plateau. He was throwing grenades when a bullet struck him above the right eye. Watson sent for Vernon, deaf and unconcerned, who was asleep at the RAP which had now been moved forward of Morrison’s section. The two carried Owen back to the medical post.

Watson now took command of the force which, as the night wore on and the Japanese pressure continued, was becoming separated and confused. He ordered Morrison’s section forward to Seekamp’s assistance but soon defenders and attackers were so intermingled that it was difficult to tell friend from foe in the misty moonlight. About 3.30 Brewer and Stevenson moved out from what had been the Assistant Resident Magistrate’s house—about 40 yards below the centre of the melée—towards a group of men over whose heads Stevenson threw a grenade as be called upon them to assist in repelling what seemed to be a new facet of the attack. Then a cross-fire from both defending flanks swept the group while, from their right, someone began to throw bombs at the two officers. The men Stevenson had called to were Japanese.

Soon it was clear that the attackers were through the northern positions and both flanks. The Australians were falling back, leaving Owen unconscious and with only a few minutes to live. Watson, Stevenson, Brewer and Morrison were among the last to withdraw. Just behind them were a Bren gunner named “Snowy” Parr39 and his mate, reluctantly giving ground. A group of 20 or 30 of their enemies appeared in the cleared area close to Parr. He blasted them deliberately at close range. Brewer said later “I saw Japs dropping”. Parr thought he got about 15 of them. “You couldn’t miss,” he said. Vernon was smoking behind a tree at the edge of the plantation. They left Kokoda and about them was

the thick white mist dimming the moonlight; the mysterious veiling of trees, houses and men, the drip of moisture from the foliage, and at the last, the almost complete silence, as if the rubber groves of Kokoda were sleeping as usual in the depths of the night, and men had not brought disturbance.40

The men were jaded and very dispirited when they arrived back at Deniki. Their actual casualties at Kokoda had not been heavy (about 2 killed, 7 or 8 wounded) but some men had been cut off in the fighting

and were missing and a few had fled. Most of the Australians were very young (the average age of one of Templeton’s sections, for example, was only 18) and the closed green world into which they had been suddenly cast was strange to them. They felt very isolated. Their enemies were the best soldiers in the world at that time in jungle warfare.

The week after their return to Deniki, however, brought both respite and assistance to the forward Australians. By midday on the 30th Dean and his company had arrived with supplies and ammunition. On 1st August Captain Symington,41 thickset and volubly confident, who had fought with the 2/16th Battalion in Syria, arrived with his “A” Company and took over as second-in-command to Watson. Two other companies and other details were moving up the track. Major Cameron, who had been appointed brigade major of the 30th Brigade after his return to Port Moresby from Salamaua, was now hurrying to the front to take temporary command of Maroubra Force.

Better organisation was now developing along the lines of communication. After Kienzle had arrived at Uberi from his trip across the mountains with Templeton he had started more carrier trains forward to Nauro, with four days’ supplies for 120 men, and to Efogi with similar quantities. On 24th July he sent Dean’s company off with 135 natives carrying packs and supplies of various kinds and 22 carrying rice. He then went quickly back to Port Moresby and there stressed to Morris the need for more carriers, for the development of a supply-dropping program with aircraft possibly using Efogi and Kagi initially as dropping areas, and for a telephone line across the mountains. Next day he set off again from Bolo with Symington’s company, Warrant-Officer Lord42 and 500 carriers. Three days later the first air drops began; rice was dropped at both Efogi and Kagi. But when Kienzle arrived at Isurava on the 31st he had word from Watson that the latter’s need for both food and ammunition was urgent as the supplies at Kokoda had been lost and no reserves were held. Kienzle then decided that the only solution was to find a dropping ground reasonably close to the front.

He remembered that on flights from Kokoda to Port Moresby before the war he had noticed a clear area on the very crest of the range which looked as though it might be the bed of a dry lake or lakes. On 1st August, therefore, accompanied by four natives, he set out from Isurava to look for this. About the point where the track topped the range he struck eastwards cutting through a tangle of dense bush and vines, and moss. Early on 3rd August he emerged from the bush on to the edge of the smaller of the two old lake beds which lay close to one another but separated by a mountain spur. It was set like a saucer in the high mountain tops, was well over a mile long and up to half a mile wide. The ground was flat and treeless and covered with rippling fields of kunai grass. A sparkling stream (part of the headwaters of Eora Creek) cut across its centre.

Bright sunshine was dissipating the last of the morning mists. Quail started up from the coarse grass and the harsh cry of wild duck broke the silence. But Kienzle did not linger. The place had no name (it was forbidden ground to most of the natives who lived in those areas) so he called it Myola.43 He sent word to Sergeant Jarrett44 at Efogi to come forward and establish a large camp at Myola as quickly as possible; then he blazed a new trail back to Eora Creek on the 4th and the point where it met the old track on the banks of the creek he called Templeton’s Crossing. By that time the laying of telephone lines across the mountains to Deniki was just being completed; next day, Kienzle told the supply officer at Ilolo of his discovery and of the acute supply position and asked for air dropping to begin at Myola. That day an experimental drop was made.

At this time, however, no effective air dropping technique had been developed. At the beginning of the Kokoda fighting, when the Australians still held the Kokoda airfield, lacking transport aircraft they used fighters to drop supplies. The belly tanks of these were slit along the bottom, filled with stores and then cast loose over the strip. But this was an expedient which could not be widely used. Practically the only guidance up to this time was to be gained from pre-war New Guinea days when supplies had sometimes been dropped to isolated individuals or parties. Following the practices then developed stores were dropped enclosed in two, or more, sacks, the outer sack being considerably larger than the inner. While the inner one would usually burst on impact with the ground the outer one would sometimes hold and prevent the contents from scattering. But not much accuracy could be achieved and, unless the area over which the stores were cast was clear and level, much of the cargo was lost, since many of the bundles could not be found in the thick bush or retrieved from rugged slopes; even in those bundles which were picked up most of the contents might be damaged beyond use; and the types of materials which could be supplied were severely limited.

Nevertheless Myola was quickly to develop as a main base in the mountains. Despite this, however, there was still a long carry of two or three days forward to the front. Over that stage everything—ammunition, rations, medical supplies, blankets—had to be transported by natives. To Kienzle, therefore, fell the task of establishing staging points and dumps at Temple-ton’s Crossing, Eora Creek, Alola and Isurava. At each of these places Angau men were in charge of carriers and, for some time, of stores also.

At the same time as these supply arrangements were developing the medical position also improved. On 30th July Captain Shera45 arrived at Deniki as medical officer to the 39th Battalion. Next day, therefore, Vernon started back along the track. At Isurava on 1st August, however, Captain McLaren46 of the 14th Field Ambulance on his way forward asked Vernon

to look after the wounded at Eora Creek until other assistance arrived. This Vernon did until Captain Wallman47 marched in on the 6th “with ten orderlies and a good supply of comforts”. Although the day was far spent Wallman himself insisted on pushing on to Isurava but he left his team at Eora Creek and thus freed Vernon for his proper duties.

There was plenty of work for him to do among the carriers. On his forward journey he had found a small hospital full of sick carriers at Ioribaiwa with an ominous threat of dysentery to come; at Nauro the Angau representative was spending most of his time doctoring the carriers and local natives; at Efogi the carriers, though well cared for by Jarrett, were showing very positive signs of hard work and exposure; they were feeling the cold acutely and lacked even one blanket a man. At the beginning of his return journey Vernon noted:

The condition of our carriers at Eora Creek caused me more concern than that of the wounded. ... Overwork, overloading (principally by soldiers who dumped their packs and even rifles on top of the carriers’ own burdens), exposure, cold and underfeeding were the common lot. Every evening scores of carriers came in, slung their loads down and lay exhausted on the ground; the immediate prospect before them was grim, a meal that consisted only of rice and none too much of that, and a night of shivering discomfort for most as there were only enough blankets to issue one to every two men.

At Kagi he met Warrant-Officer Rae48 of Angau

who was one of the best fellows on the line. ... He and I had a long talk over the troubles of the carriers and the upshot was that I sent a message to Angau to say that less than half had blankets and none a liberal enough diet. We added that a day of rest once a week was becoming a necessity and that overwork and exposure was playing havoc with the [native] force. Indeed at this period I thought that our [native] force was rapidly deteriorating; later on I considered it almost at breaking point.49

Meanwhile, at Deniki the spirits of the Australians were rising once more. They were rested; their isolation was lessened by the completion of the telephone line on 4th August. Cameron arrived to take command of them the same day and they felt his vigour. They were reinforced. When Captain Bidstrup,50 with the remainder of his “D” Company, arrived at Deniki on the afternoon of the 6th, all companies of the 39th Battalion were represented in the Deniki–Isurava area and the total strength was 31 officers and 433 men; there were also 5 Australian officers, 3 Australian NCO’s and about 35 natives of the Papuan Infantry Battalion; there was a small group of Angau leaders with 14 native police. Cameron’s plans for an attack on Kokoda—where it was thought there were 300–500 Japanese—were then well advanced.

The 7th August was the day of final preparation. One of Symington’s

patrols reported that they had killed eight and wounded four of an opposing patrol for the loss of one man wounded. Cameron sent Brewer and Captain Sorenson,51 with Sanopa and another policeman and two local natives, to reconnoitre a track along which he hoped to send Symington’s company into the assault. Sanopa, keen of sight and hearing, moved warily in front of the patrol all the way, a rifle swinging loosely in one hand, the other hand holding a grenade. The patrol reached the edge of the rubber just south of the station and saw no Japanese on the plateau.

In the early morning of the 8th three companies moved out for the attack. Bidstrup left at 6.30 for the vicinity of Pirivi where he was to hold any Japanese movement from Oivi against the right flank of the attack. With his company went Warrant-Officer Wilkinson, Sergeant Evensen52 and 16 Papuans. Half an hour later Symington moved out, Brewer with him and Sanopa heading the forward platoon. Symington’s men were to drive into Kokoda by way of the track which Brewer and Sorenson had explored the previous day and which ran between the track to Oivi on the right and the main track from Deniki on the left. They constituted the central pivot of the assault. At 8 o’clock Dean’s company, with the task of attacking along the main Deniki–Kokoda track as the left flank company, started for their forming-up area. They took with them four Australians and 17 Papuans of the PIB.

On the right Bidstrup’s company met opposition near Pirivi and lost 2 men killed and 2 wounded (including Lieutenant Crawford,53 the platoon commander). Sergeant Marsh54 took over this platoon and Bidstrup sent Crawford back to Deniki for treatment with an escort of two men. (Later Crawford told the men to leave him and return to the company; he was not seen again.) This fighting delayed Bidstrup’s ambush which was planned to be in position by 11 a.m. at the junction of the track the Australians had followed from Deniki and the Oivi–Kokoda track. None the less Bidstrup had his ambush in position by the time a strong Japanese party from Oivi, warned by escapers from the clash at Pirivi, came questing carefully up the track. McClean’s platoon, in the right-flank positions on the southern side of the track, poured telling fire into them and shot many Japanese before they could get to cover. Australians and Japanese then engaged one another in the thick bush. But Marsh’s platoon, just getting into position 100 yards or so to the left, had been set upon by a party of Japanese coming down from the Kokoda side. Almost at once they lost 2 men killed and 2 wounded and, as some of the Japanese from the Oivi side joined in the fight, were very hard pressed. They were forced into a tight perimeter defence and could get no word to Bidstrup, who had been trying, just as anxiously, to get in touch with them. He sent two

runners out but neither was seen again. At 4.30 p.m., therefore, with darkness approaching and knowing that Marsh had been ordered to make his own way back to Deniki if cut off, he withdrew his main force, harassed by energetic attacks from the front and flanks as he did so. He had heard no firing from Kokoda so, feeling that the attack had not gone according to plan, made for the village of Komondo where he bivouacked for the night. He knew that he had lost 11 men killed, wounded or missing, but did not know what losses Marsh had suffered.

While Bidstrup’s company was thus engaged Symington, on the central axis, was having an easier time. At noon he and his men had moved north from the rubber plantation, their advance preceded by bombing and strafing by 16 Airacobras (P-39s). They found only four or five Japanese in Kokoda and these fled. They ranged through the settlement area and to the northern end of the airfield and then, having taken a small quantity of Japanese equipment, dug in for the night.

Moving down the main track Dean’s men quickly ran into trouble. First they clashed sharply with a Japanese patrol and then came against well-sited machine-gun positions commanding a creek crossing in a steep gully. Though they fought hard, and Cameron strengthened them with some Headquarters Company men, they could make little progress. Sergeant Pulfer55 was killed trying to bring in a wounded man. Cameron himself went forward to study the position and discuss it with Dean. Dean then moved across the creek and was shot. Shera hurried forward to help him but Dean was dead before he arrived. The company then attacked so vigorously that they drove the Japanese out of their most forward positions and killed a number of them. As they pressed on, however, they came hard against other positions. The day wore on and Cameron realised that his men could not advance and he broke off the attack. As the troops fell back they picked up their wounded. (Chaplain Earl,56 who had moved out with the company at the beginning of the day, had been caring for eleven of these in a little clearing among what had been the foremost Japanese positions; he gave them cigarettes taken from the pockets of dead Japanese.) But the Japanese followed the withdrawal and began firing on the front of the Deniki positions at about 5.50 p.m. Their fire continued intermittently until about 9 p.m.

During the night of the 8th–9th August, therefore, the position was that Bidstrup’s company (less Marsh’s platoon) was bivouacked at Komondo on their way back to Deniki; Marsh’s platoon, unknown to Bidstrup, was in a tight perimeter defence just south of the Oivi–Kokoda track (and they lost another man during the night when Private Joe Dwyer57 slipped quietly away to try to find water for the wounded and was never seen

again); Symington was passing an undisturbed night at Kokoda; “C” Company, now commanded by Captain Jacob,58 was standing-to at Deniki.

On the 9th the Japanese began to attack Deniki again about 7.45 a.m. and continued their attacks sporadically until the early afternoon. During these attacks Jesser shot a native whom he saw guiding a Japanese party into the battalion position but, in doing so, was wounded himself About 1.30 Bidstrup and his main body began to arrive. Bidstrup still had had no word of Marsh’s platoon. (Marsh and his men arrived next day, the two wounded men carried by the others. They had slipped out of their perimeter position near Pirivi in the dull dawn of the 9th, concealed in the half-light and thick bush.) The attacks on Deniki waned as the afternoon advanced and night settled quietly over the Deniki area.

Little of this quiet was shared by Symington’s men, who were being gradually beleaguered at Kokoda. News of them had been brought to Deniki on the morning of the 9th by the indefatigable Sanopa who, with another policeman, had then brought out some captured maps, probably the first taken in this campaign, and a request for aircraft to drop food and ammunition as each man was carrying only two days’ dry rations, about 100 rounds, and two grenades. The two policemen had then returned to Kokoda.

By that time events were moving fast there. The morning of the 9th had found Symington’s men dug in in the old Australian positions. In the rubber at the South-east end of the administrative area Lieutenant Neal59 had his platoon. About 11.30 a.m. he detected Japanese, smeared with mud and hard to see among the trees, creeping stealthily forward to his position.

He was reinforced with another section and drove his enemies to the ground with fire. Intermittent weapon engagements took place during the afternoon. Towards evening the attackers gathered a force which Symington estimated to be about 200 strong and struck violently at Neal’s position. The Australians flayed them with fire. In the early evening quiet figures crept towards the defence and there was close fighting with grenades and bayonets. Going up to Neal’s position later in the night Sorenson found two of the men lying in a forward position with their throats cut. It was hard to see the enemy in the darkness and the rain. Firing continued, and in the early morning of the 10th, another attack was beaten off.