Chapter 3: Kanga Force

In the weeks following his arrival in Australia General MacArthur found himself hedged about by those same circumstances which had prevented the Australian military leaders from planning to offer strong opposition to the Japanese in the islands to the north. General Blamey’s reorganised army was only beginning to take shape; American ground troops were only just arriving and the stage of training they had reached did not yet fit them for active operations; the Allied air forces in Australia were still inadequate and sufficient airfields were not available for them to operate far afield; the British Far Eastern Fleet could not hope even to prevent Japanese naval domination of the Bay of Bengal still less to play an effective part elsewhere; and the American Navy was still on the defensive in the Pacific, probing tentatively against the Japanese in a series of hit-and-run raids, and able to guarantee no measure of security for Allied forces which might be sent outside the main base, or even for Australia itself. In very similar circumstances MacArthur had already fought and lost a major campaign in the Philippines. During his first months as commander of the South-West Pacific Area he was in no position to try to force an issue with the Japanese. Even in mid-May, when examining the possibility of an approach towards Japan through New Guinea and New Britain to the Philippines, MacArthur’s Chief of Staff, Major-General Sutherland, wrote:

... the Japanese have, at present, sea and air superiority in the projected theatre of operations; and the Allied Forces, in the South-West Pacific Area, will require local sea and air superiority, either for participation in the general offensive, or for any preliminary offensive undertaken when opportunity offers. Sea control would rest primarily on air superiority.

Until June, at least, MacArthur lacked the forces needed for large-scale operations outside Australia, but, while he was waiting for his air and naval strength to be reinforced, there was one minor way in which the Australians could worry the Japanese on land in the islands—by guerrilla action.

In the Australian Army at this time there were Independent Companies which had been specially formed for such operations; some of these have already been mentioned. Their immediate origin was to be found in ideas which developed in England in the early and difficult months of the war, although the basic idea on which they were founded went back as far as the history of war itself, and had found modern expression in the Peninsular War, after the main Spanish armies had been driven from the field; in the tactics of the Boers who, their formed strength broken, had tied up 250,000 British troops for two years by the skilful use of small bands of well-armed and highly skilled bushmen whom they called “commandos”; in Palestine during 1936–37. When the German armies extended themselves along the coast of Western Europe some British leaders became

interested in plans whereby British commandos might strike them small but stinging blows, and they set about the formation of small units of bold men in whom would be “a dash of the Elizabethan pirate, the Chicago gangster and the Frontier tribesman, allied to a professional efficiency and standard of discipline of the best regular soldier”.1 Thus, by early 1940, the British Army had formed (from Territorial battalions) ten such companies to supplement the Royal Marines in landing operations. By June of that year five were fighting in Norway and, on the 24th of that month, men of No. 11 Commando carried out the first raid across the Channel. Other such raids (by Special Service Troops as the British came to call them) followed, and then Independent Companies began to operate in the Middle East.

Late in 1940, a British officer (Lieut-Colonel J. C. Mawhood), with a small specialist staff, arrived in Australia to initiate training designed to produce a high standard of efficiency in irregular warfare. The original Australian intention was to form four Independent Companies in which each soldier should be a selected volunteer from the AIF aged between 20 and 35, and of the highest medical classification and physical efficiency.

The organisation of a training school (No. 7 Infantry Training Centre) began in February 1941. It was sited on Wilson’s Promontory, Victoria, in an isolated area of high, rugged and heavily timbered mountains, precipitous valleys, swiftly running streams, and swamps. Its winter climate was harsh (and prolonged periods of wet weather were later to impede training and affect the health of the trainees). By October the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Independent Companies had been formed and trained, each commanded by a major and consisting of 17 officers and 256 other ranks, divided into company headquarters, engineer, signals and medical section, and three platoons each of three sections. The nucleus of the 4th Company was then at the centre when it was decided to discontinue training because specific tasks for additional companies could not be envisaged. In December, however, after the outbreak of war with Japan, the school was reopened as the Guerrilla Warfare School, the training of the 4th Company was completed, and the 5th, 6th, 7th and 8th Companies were rapidly formed.

From the beginning the army was not single-minded in its attitude towards Independent Companies. There was a feeling among some officers that well-trained infantry could do all that was expected of the commandos, and that the formation of these special units represented a drain on infantry strength that was out of proportion to the results likely to be achieved. The supporters of the commando idea replied that the new companies would relieve the infantry of the task of providing detachments for special tasks.

While the war with Japan was looming, and in its early months, the Independent Companies were scattered round the fringes of the Australian area with the intention that they should remain behind after any Japanese occupation and harry the invaders. Thus, as mentioned earlier, the 1st

Independent Company was spread from the New Hebrides to the Admiralties, the 2nd went to Timor, the 3rd to New Caledonia, and the 4th to the Northern Territory.2

In April, when the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles were observing the Japanese at Lae and Salamaua, General Blamey thought that there was an opportunity to use independent troops to develop a minor and local but profitable offensive. Thus Major Kneen’s 2/5th Independent Company arrived at Port Moresby on 17th April on the way to cooperate with the NGVR, to keep close to the Japanese in the Markham Valley, and to raid the Japanese installations there with the main purpose of hindering their air operations from the local aerodromes.

During 21st–24th April Generals Vasey and Brett were at Port Moresby. Among the decisions reached during their visit was one to form a guerrilla group to be known as Kanga Force. This was to consist of a headquarters, to be raised from details in the Port Moresby area, the NGVR, Lieutenant Howard’s platoon which was now in the Wau area, the 2/5th Independent Company, and a mortar platoon which was to be raised from the 17th Anti-Tank Battery and other units in Port Moresby. Immediately Howard’s platoon was to reconnoitre the Markham Valley with a view to later offensive action against Lae; the NGVR was to reconnoitre the Lae and Salamaua areas and carry out restricted offensive action there. Neither the commandos nor the NGVR were to take any action that would “prejudice the main role of Kanga Force, which will be the attack of Lae and of Salamaua, making the most use of the factor of surprise”.

MacArthur wrote to Blamey on 1st May that he hoped an opportunity would soon occur to take “a limited offensive”; the chance might present itself to raid Lae and Salamaua, or even to retake them, by an overland advance from Port Moresby.

Blamey replied that he entirely agreed and that tentative plans for such an operation had been made during the visit of Generals Brett and Vasey to Port Moresby; aeroplanes would be needed to transport the new troops and then to maintain them; a raid on Lae could produce very good results, but he doubted whether the forces available would be able to retake and hold the town; the 2/5th Independent Company was being held at Port Moresby in view of the threat of a Japanese attack but, if that threat were removed, he would order the operation to be carried out if air transport could be arranged. MacArthur then asked Blamey to carry out his plan as soon as the position justified it and said he was asking Brett to provide aircraft for the operation and maintenance of the force.

While this exchange had been taking place there had been little movement round Salamaua since the Japanese raid on Komiatum in late April. There had been brushes along the Markham, however. On 1st May near Ngasawapum (about four miles east of Nadzab) an enemy patrol surprised three Australians who were driving along the road in the ration truck. Suddenly, some distance ahead, a native sprang on to the road waving his

lap lap—a recognised danger signal. Between him and the truck, Japanese were waiting in ambush. The Australians escaped into the kunai and their enemies started towards Nadzab in the truck. Farther along the road Sergeant Mayne3 of Howard’s platoon was on his way to join his officer at Diddy, with a signaller, McBarron,4 and two riflemen. The Japanese in the truck overtook them and made Mayne and McBarron prisoners though the two others escaped.

Two days later a Japanese patrol about 15 strong surprised Howard and other men camped in the timber behind Jacobsen’s Plantation. The Japanese began to fire wildly before they got close enough for accurate shooting. Thus the Australians escaped, though they lost most of their clothing and all of their equipment and Jacobsen’s was closed as a forward post.

Following this raid an aeroplane strafed the mission at Gabmatzung, near Nadzab, on 6th May and, on the same day, that aircraft or another flew low for half an hour over Camp Diddy apparently examining this area where Major Edwards had all his wireless equipment, most of his stores and 16 sick men. Edwards therefore withdrew most of his men across the river but soon afterwards Captain Lyon began to operate regularly once more from Diddy as an advanced base and Ngasawapum and Munum as forward posts, with telephones connecting the three.

On 21st May Lieutenant Noblett,5 with a detachment which included Lance-Corporal Anderson6 and Rifleman Emery,7 reoccupied the post near

Heath’s and made a camp in the creek-bed about ten minutes’ walk away. At dawn the next morning Emery guided Anderson towards the post, and left him within a few yards of it. Scarcely had he turned when he heard a shot. He waited. There were no more shots but he heard Japanese talking. He hurried back to warn Noblett and the rest and found that they also had heard the shot. They hid themselves in thick bush along the track and waited. Sergeant R. Emery shot the first Japanese to appear and the other attackers began to fire wildly—even the field gun at the plantation joined in with a few rounds—and most of the Australians began to make their separate ways out of the area as the firing died down. Noblett, however, waited in the bush for about seven hours and a half, watching the Japanese. When he saw one alone he shot him. While he was cutting off the dead man’s badges four other Japanese arrived. “I was very lucky to get out of it,” reported Noblett, who thought that natives had told the Japanese of the presence of the Australians.

It was now clear that some natives were giving information to the invaders. The NGVR, however, continued to use Diddy, Ngasawapum and Munum. They watched the road, made regular visits to Heath’s area and sent occasional patrols as far as Lae itself. At Narakapor, south of Ngasawapum and off the main road, on the 27th May, two of them met a native named Balus who had given the Australians much help in the past. He told them that the Japanese had told the Butibum natives, who were friendly to the invaders, that reinforcements would shortly arrive and that the Japanese, led by natives from Butibum and Yalu, would then move up the Markham Valley and into the Bulolo Valley. (Butibum was close to Lae on the North-western side.)

It must have been difficult for the natives to decide whom they should help. The Japanese were in a commanding position at Lae and Salamaua and the Australians were homeless in the bush—a compelling argument to simple minds. In addition the Japanese did not merely ask but demanded cooperation from the villages and the consequences of refusal were harsh, the burning, or air bombing and strafing of a reluctant village being routine procedures. (The villages of Munum, Guadagasal and Waipali were all burned by the Japanese at various times.) It was understandable that even many villages which had no love for the Japanese, no desire to aid them, and were loyal to their former masters, would greet the Australians with little enthusiasm when they came. But even so the attitude of the natives to the Australians was generally one of friendly helpfulness largely due, no doubt, to the fact that the men of the NGVR were skilled in handling them and many were well known to some of the villagers. Many natives indeed went beyond an attitude of sympathy and friendliness and passed on information at considerable risk to themselves, or patrolled deep into Japanese territory as guides or on other missions. Some, however, were prepared to aid the Japanese, whether from feelings of resentment dating from pre-war times, from hope of gain, or for personal reasons of various kinds it is hard to say.

The men of the NGVR had filled a large gap in the period up to

late May. Under difficult conditions they had carried out a task of watching and keeping touch with the invaders, and of letting the bewildered natives within the Salamaua–Wau–Lae semicircle see that the Australians had not been driven completely from the area. They had done this within a spidery organisation and largely through their own ability to improvise; through knowledge, experience and common sense which had to serve instead of the benefits of training; through individual courage and patient watchfulness instead of as part of an integrated machine. Now they were to take their place in a more ambitious organisation, which brought some benefit to them and some disadvantages.

When the Battle of the Coral Sea was over Blamey and MacArthur agreed that the “limited offensive” they had planned could be got under way. On 12th May Major Fleay8 was appointed to command Kanga Force and was ordered to concentrate his force in the Markham Valley “for operation in that area”, his task, as more specifically defined earlier, “the attack of Lae and of Salamaua, making the most use of the factor of surprise”.

Fleay, only 25 at this time, had been an original member of the 2/11th Battalion. His task now obviously called for coolness and mature judgment, experience in handling men so that the diverse elements under his command could be alternately driven, coaxed and inspired into overcoming the difficulties of the lonely and dangerous days which lay ahead of them and so that they could draw from their commander a strength which would make up for the lack of an orthodox military organisation behind them. But Fleay’s own experience was limited and in particular he lacked knowledge of tropical conditions.

It was planned now to fly the reinforcements into the Wau area. Transport aircraft were very scarce, however, and, with Zeros operating from Lae, strong fighter escort for any troop movements by air was essential. Unfavourable weather also hindered the planes so that it was not until 23rd May that the movement of Kanga Force began. Then the headquarters, most of the Independent Company and the mortar detachment were flown to Wau. This was the first substantial movement of troops by air in New Guinea—a form of troop transport which was to become commonplace later.

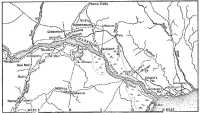

By 31st May Fleay was able to report that his own headquarters and his mortar detachment were at Wau. Kneen’s men were spread down the Bulolo Valley as far as Bulwa, Howard’s headquarters were at Bulwa, with one of his sections at Kudjeru, one at Missim, and one preparing to take over from the NGVR at Mapos. The NGVR still had Captain Umphelby’s company watching the Salamaua sector from Mubo, and Lyon’s company covering the routes inland from the Markham with a rear headquarters at Bob’s Camp, south of the junction of the Markham and Wampit Rivers, and a forward headquarters still at Camp Diddy.

Fleay then prepared to give the weary men of the New Guinea unit

some respite, and ordered one of Kneen’s sections under Lieutenant Doberer9 to move to Bob’s on the 6th June to come under Lyon’s command for forward reconnaissance, and a second section, under Lieutenant Wylie,10 to move similarly on the 10th.

By now Fleay’s instructions had been finally clarified. He defined his object as “to harass and destroy enemy personnel and equipment in the Markham District” (including Salamaua in that area). With this object in view he summed up the position as he saw it about 10th June.

He considered that there were 2,000 Japanese at Lae and 250 at Salamaua as against 700 men under his own command of whom only 450 were fit for operations: the threat of Japanese entry into the Bulolo Valley committed him to the protection of the numerous tracks which led there from the Salamaua and Lae areas and of the overland route from Wau to Papua by way of Bulldog; the threat of air invasion forced him to provide for the defence of the most likely landing points—Wau, Bulolo, Bulwa and Otibanda; to a considerable extent he was in the hands of the natives, firstly because he had to rely on them to maintain his supply line and secondly because the pro-Japanese activities of some of them gave him little chance of surprising his enemies at Lae or Salamaua with large forces. He concluded that the only course open to him was to maintain as large a force as possible for the defence of the Bulolo Valley and the overland route to Papua and to engage the Japanese by raids designed to inflict casualties, destroy equipment and hamper their use of Lae and Salamaua as air bases. He decided that these raids should be on Heath’s Plantation (where the Japanese formed an obstacle to any large-scale movement against Lae); on the Lae area to destroy aircraft, dumps and installations and to test the defences with a view to operations on a larger scale in the future; on the Salamaua area to destroy the wireless station, aerodrome installations and dumps; that they should take place in the order indicated and should be prepared rapidly, as the need for action was urgent.

Accordingly he at once issued orders for the raid on Heath’s and that preparations be made for the attack on Salamaua. As it transpired, however, the Salamaua raid was made first. It could be planned in great detail as a result of the work of Sergeant McAdam’s scouts, by whom scarcely a movement in Salamaua went unnoticed. From one of their posts the bell sounding the air raid alarm on the isthmus could be clearly heard. They watched working parties, vehicle movements, officers and men entering and leaving buildings. They built up a complete picture of all strongpoints and weapon positions and knew the purposes for which the various buildings were being used. They reconnoitred all the tracks leading into the town.

In his initial orders for the attack on Salamaua Fleay named Umphelby as the commander and told him that, in addition to his own men, he would have two sections (each of one officer and 18 men armed with

rifles, 1 Bren gun and 3 sub-machine-guns), a mortar detachment and 3 engineers from Kneen’s company. His objects were to destroy aerodrome installations, particularly the wireless station and dumps; to kill all Japanese who were met, and to capture equipment and documents so that identifications could be made.

Captain Winning11 of Kneen’s company led the commandos into Mubo on the 15th June. With him were Major Jenyns and three NGVR men under Sergeant Farr12 to control the native carrier lines. Jenyns, Umphelby and Winning then went on to the forward observation areas where they learned that the estimated Japanese strength in Salamaua had risen to 300 men. At a conference of the officers and Sergeant McAdam on the night of the 17th it was decided that Mubo was too far back for a base camp and Winning and McAdam were to reconnoitre for a new advanced base.

On the 18th, therefore, these two and Rifleman Currie went out on a three-day reconnaissance. They chose a forward base about three miles in a direct line from Salamaua, crossed the Francisco River and selected as the assembly point for the raid the site of the old civilian evacuation camp at Butu, entered the aerodrome area and examined the Japanese dispositions and activity, and reconnoitred Kela village area as far as the Japanese wire.

Selected men from the NGVR and the commandos were given brief training together. From an aerial photograph of Salamaua a sand-table was built and on this model tactics were planned, the NGVR men supplying minute details of location and layout.

But some of the preparations were troubled ones. Supply, as always in this difficult country, was a particular problem. At Mubo there were no reserves to meet the sudden accretion of AIF troops and the newcomers had to draw heavily on the small NGVR dumps. The move forward from Mubo had been timed for 23rd June but the late arrival of supplies meant that the force did not arrive at the forward camp until just before dark on the 25th. The carriers were behind them again and so it was not until the 27th that the Butu assembly area was reached. The time for the beginning of the raid was then fixed for 3.15 a.m. on 29th June.

For a short period there was difficulty also regarding the command. Although Umphelby had been nominated by Fleay in his written orders as commander, Winning said that he himself had been instructed to take command. Finally Fleay ruled in favour of Winning, a tough, active, sandy man, dynamic, unorthodox, shrewd; his self-confidence inspired confidence in others.

The raiders spent the afternoon of the 27th and the whole of the 28th in briefing and rehearsal, and in consolidating the work which had been done on the sand-table at Mubo. During this preparation they kept a close

watch from the observation posts on the Japanese who showed no signs of uneasiness or awareness.

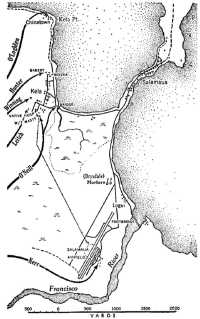

The tactics of the raid were determined by the peculiar topography of the Salamaua area. There the main coastline ran roughly Northwest. From it a narrow isthmus thrust out to the Northeast, not more than a mile long, only a few feet above sea level, generally less than 300 yards wide and spreading into the solid mass of a heavily timbered hill at its northern end. On the southern side of the junction of the isthmus with the main coastline, and about a mile and a quarter below it, the Francisco River, flowing roughly Northeast reached the sea. Less than half a mile from the river, on the Salamaua side, was the airfield. Almost due north of the aerodrome, across a swamp, was the village of Kela from which the coastline ran due north again for less than a mile and turned sharply west to form Kela Point. The whole Kela and Kela Point area was fairly thickly covered with houses—native, Chinese, European—stores and administrative buildings.

The aerodrome, Kela and Kela Point areas were all strongly held by the Japanese and McAdam’s men had noted which houses had the most important occupants. The plan was to attack selected objectives roughly along the line from the aerodrome to Kela Point, with the mortar detachment in position to break up any attack which might develop from the isthmus and fan out towards the aerodrome on the south and the Kela area on the north.

The raiding troops were divided into seven parties. The first, under Lieutenant Kerr13 (of the Independent Company) with Lieutenant Lane14 of the NGVR and 17 men, including the guide, Kinsey, was the aerodrome party. Its task was to destroy three red-roofed houses—where the Japanese had their billets and aerodrome headquarters east of the hangar—and kill the occupants. The second party, under Sergeant O’Neill15 with McAdam as guide, was to blow up the two steel wireless masts and wireless equipment on the southern fringe of the built-on Kela area, and the bridge just to the Northeast by which the coastal road crossed a tidal stream feeding into the swamp. This party was also to hold the road against reinforcements from the isthmus. O’Neill and McAdam had five other men with them, two of them engineers. The third party, four men under Lieutenant Leitch16 and guided by Cavanaugh, had the medical assistant’s former house, just west of the wireless masts, as its objective. A little north of this house was one which had formerly belonged to the “policemaster”, near it a white-roofed house where a sentry was known to be stationed. Winning and Umphelby, with Cavanaugh guiding them also and accompanied by five other soldiers, were to move against these

The raid on Salamaua

buildings. A fifth party, its total strength ten, guided by Currie, was to be led by Corporal Hunter17 against opposition in the Morobe bakery area which was among bush between Kela and Kela Point. Lieutenant O’Loghlen18 of the NGVR, with Archer as guide and six other men under his command, was to destroy houses and Japanese in the Kela Point area. The seventh party was under Lieutenant Drysdale,19 guided by Private Suter20 (the only guide not from the NGVR) who had Gomari, Cavanaugh’s personal boy, to assist him. This was the mortar party and consisted of its leader and ten men (not including Gomari).

Originally it had been hoped that the raiders might be able to clean up the outer areas quickly and then advance along the isthmus. But that required effective air support beforehand to neutralise the isthmus defences, and two night raids before the 28th had not been well executed and a daylight raid requested for the 28th did not take place.

At 2 p.m. on the 28th the various parties began to move out from Butu for their starting areas. Drysdale’s men moved first and settled at Logui village on the Salamaua side of the Francisco River. The other parties followed at times arranged in accordance with the distances they had to travel. Each rifleman carried at least 60 rounds, each Tommy gunner 150 rounds. Every man carried as well a pistol and two hand grenades. For each house to be demolished one sticky grenade, reinforced with two one

pound slabs of TNT wrapped in a hessian bag, was carried. Bundles of two to four flares with instantaneous fuses were taken for setting fire to other houses and prepared charges were carried by the sappers for destroying the bridge and wireless masts.

The early part of the night was driven through with heavy rain, but this cleared and left Salamaua bathed in bright moonlight.

Before nightfall Kerr’s party was looking over the aerodrome from a position 500 yards from the South-west corner of the strip. Most of them slept while Kinsey reconnoitred an approach in the darkness. He could hear a Japanese sentry singing quietly to himself. At 1.40 a.m. the main body began to move forward. Kinsey took them through bush, pit pit21 and bamboo on the eastern side of the strip until they were roughly opposite their objectives. There was a little delay in finding the track through the last 200 yards of thick scrub and they were barely in position when the sound of sudden fire and a louder explosion from the direction of Kela village shattered the night. Japanese poured out of the houses towards shelters and trenches.

The enemy must have had a defence plan at the drome which made our job harder than that of the other groups (Kerr said later). They must have had alert sentries, because they ran—or tried to run—to their defensive positions as soon as the firing opened up at Kela.

The Australians shot most of them down, then charged to their demolition tasks. Kinsey described what they did.

We used one sticky bomb and two pounds of TNT on each building. We raced up the steps, dropped bombs into the centre of the house, and retreated, covered by rifle and Tommy-gun fire and grenades. Some houses had three or four Japs, some more. The house I went to—some of the Japs had got out into dugouts—I got at least five Japs. After the explosions there was much wild shooting from the Japs. ... We fired into bushes and houses.

Kerr put a Bren gun team on the edge of the strip, near the hangars, to cover the rear of the houses and sweep the area. Several Japanese fired at intervals from an air raid shelter and occasional bursts of fire came from the corners of damaged buildings. Towards dawn Japanese reinforcements began to arrive. The Australians dropped back to the hangars and tried to fire the charges but they would not ignite. As daylight was breaking Kerr led most of his men back into the bush. They waited for some hours while Kinsey searched for four missing soldiers but finally they left without them and arrived back at Butu about 5 p.m.

When the firing from Kela started O’Neill’s demolition party was about 80 yards from the bridge. They raced along the road, fired a Tommy-gun burst into a sentry post, threw a grenade into an air raid shelter where they thought Japanese were hiding, then the engineers went to work with their charges while the rest of the group covered them. The charges were almost set when mortar bombs began to fall, first round Kela Point, then near the bakery and then on the bridge itself and the near-by road

junction. One bomb, exploded squarely on the bridge, set off the charges. The bridge was blown to bits. Machine-guns, firing a large proportion of tracer, began to range on the road junction and one of the engineers was wounded. A large gun, or mortar, began to drop missiles on the hills behind Kela. By this time Winning’s group had joined O’Neill. They had found the houses which had been their objectives empty so had ranged through the village killing any Japanese they saw. A man came running along the road and was brought down. He was a Japanese airman and they took documents from him.

The firing and the explosion which had startled the other parties into action a minute or two before the time actually fixed had come from Leitch’s and Hunter’s parties. Hunter’s raiders had run into an alert sentry near the bakery which sheltered the men they had been detailed to kill. They had to shoot him with a sub-machine-gun and thus the alarm had been given. Other Japanese leapt from their sleep. The Australians killed them but Currie was wounded. Hard after Hunter’s first burst of fire Leitch’s men had thrown a “reinforced” sticky grenade into the medical assistant’s house. Bewildered survivors rushed out. But sub-machine-gunners were waiting at two diagonally opposite corners of the house. One gunner said he shot six of these Japanese, the other said he shot one. Leitch’s men thought that, all told, they killed twenty of the enemy in and around that house, including three officers.

Meanwhile O’Loghlen’s party was busy at Kela Point. Its initial approach had been hampered by the presence of native dogs. Archer had then crept through the shallow water of the ocean’s edge, under cover of a three-foot sea wall, along the whole line of houses. He could hear the voices of the Japanese inside or alongside the houses which were thought to be occupied. O’Loghlen decided to attack from the seaward side. Scarcely did he have his men in position, only five yards from where two Japanese sentries were sitting, when the firing at Kela village began. His men, Archer said later, hurled their bombs into the two houses which they thought contained Japanese and destroyed them. They thought also that they damaged three other houses with flare bombs but in five or six others the flares failed to ignite. The raiders were satisfied that they killed fifteen Japanese and they captured a sub-machine-gun and three rifles. As they began to withdraw they came under machine-gun and mortar fire and had one man wounded.

From Logui Drysdale heard the first shots and had his mortar in action within fifteen seconds. After four ranging shots every bomb fell on the isthmus. All told Drysdale’s men fired 36 bombs. One of them fell directly on the most important target, a strongpost at the neck of the isthmus, soon after the garrison there had opened fire. Fifteen men were thought to have been in this post. When two red Very lights were fired as a distress signal by some of Kerr’s opponents on the aerodrome about 4 a.m. Drysdale thought that Winning had fired them since this had been agreed upon as the withdrawal signal. He therefore ceased fire and prepared to get his men out. But a Japanese mortar was dropping its bombs at the Francisco

River mouth where they were to cross; the tide was high and the crossing deep and dangerous. The Australians therefore hid their mortar to give them a better chance to get clear. Finally they crossed safely.

By 11 a.m. all the raiders were back at Butu except Kerr’s party. The Japanese were still shelling, mortaring and machine-gunning Kela village and the point. Aircraft strafed the bush and bombed what the pilots thought might be the withdrawal tracks. About midday Winning began to lead his men back to the forward base camp, passing through a defensive post of NGVR men under Lieutenant Hitchcock22 waiting for the Japanese to follow up. But pursuit did not come. By the following day when all of Kerr’s men, including those four who had been missing at the time of his withdrawal from the aerodrome, had reported back it was seen that the raiders had suffered only three casualties—the men who had been wounded. None of the wounds were serious.

In reporting the results of the raid Winning estimated that a minimum of 100 Japanese had been killed, 25 by Kerr’s men, 7 by his own and O’Neill’s, at least 20 by Leitch’s men, at least 20 by Hunter’s, 15 by O’Loghlen and his party, possibly 13 by Drysdale’s mortar. He claimed six houses certainly destroyed, three trucks, one bridge and a bicycle. He said: “I and my fellow officers consider this estimate to be very conservative.” One of the few particulars in which the raid was not successful was that the charges laid at the wireless masts did not explode.

Up to the time of the Salamaua raid practically no Japanese equipment or documents had been taken by the Australian Army. Winning sent back a sub-machine-gun, a rifle and bayonet, ammunition, shell fragments, a waterproof cape, an airman’s helmet, goggles and gloves. Documents taken included a number of marked maps and sketch maps, a diary, copies of orders and other material which produced valuable information. Badges collected by the raiders assisted materially in building up an Order of Battle.

The raid made the Japanese at Salamaua very nervous. During the 29th they shelled the vicinity of Kela and Kela Point. Aircraft flew low over the mountain trails. Some days later, fighting patrols up to 90 strong scoured the foothills. The Butu camp was found and some stores were destroyed. An estimated 200 reinforcements were seen to come from Lae between 29th June and 8th July. Watchers thought that others might have come unseen by night. Kela village was converted into a strongly-held perimeter position.

On the same day as he had ordered Umphelby to prepare for the attack on Salamaua Fleay had told Kneen to prepare to attack Heath’s with a raiding party formed from Doberer’s and Wylie’s sections, a mortar detachment, and Lyon’s NGVR company. He was to destroy the Japanese soldiers and equipment at the plantation, capture documents and equipment.

By 15th June the commandos and the mortarmen were operating with Lyon’s men from Diddy. They took over the standing patrol at Ngasawapum and patrolled down the Markham Road gathering information for the raid. One of their reports suggested that part of the Heath’s area had been wired and that possibly there was a Japanese position at Lane’s Plantation near Heath’s. Kneen himself patrolled deeply to the Lae side of Heath’s and Doberer was active in the same area. They decided that the high ground on that side offered the best jumping-off place for the raid.

It was about this time (mid-June) that Sergeant Emery and Rifleman Murcutt23 attempted an exploit that was hazardous by any standards. They floated on a raft down the Markham from Nadzab intending to land in the darkness about three miles from Lae and work through to the aerodrome, but found it impossible to stop at their intended landing place. Faced with the prospect of being carried out to sea in full view of their enemies, they capsized the raft and made their way ashore, losing all their stores. They then made a long, dangerous trek back through an area thick with Japanese. Their trip was not entirely fruitless, however, for they noted eight new houses at Jacobsen’s and later informed the air force of these as possible targets.

Kneen now planned to lead Lieutenants Doberer, Wylie, Phillips and 54 men along a track which followed closely the north bank of the Markham between the river and the road, assemble at Bewapi Creek about a mile South-east of Heath’s, move up the creek and then along the road and attack Heath’s from the Lae side. To cause confusion and hinder reinforcements coming from Lae he would blow up the bridge (30 to 40 feet long and supported by two heavy beams) by which the road crossed the creek. After the raid he would withdraw his force along the road past Munum Waters (some four miles north of Heath’s) where Captain Shepherd24 of his own company would cover him through. Air support was promised in the form of attacks on Lae between 6 and 9 on the morning after the raid to disorganise Japanese counter-measures.

About 2 p.m. on the 29th the raiders left Diddy for Narakapor where they spent the night. They were a formidable force; 21 of them carried Tommy-guns, 37 had rifles, most of them had revolvers as well, and each carried two grenades. They had no sticky grenades or TNT but they carried explosive charges to destroy the bridge and the gun.

On the 30th they travelled the overgrown track along the Markham bank and finally broke through swamp and bush to reach about 4 p.m. the small cleared patch on Bewapi Creek which was their rendezvous. Over them as they walked a Zero had dived and twisted, giving them anxious moments, but apparently the pilot did not see them.

Kneen took with him his Intelligence sergeant, Booth,25 and Privates

Murray-Smith26 and Hamilton27 who had volunteered for the task of destroying the bridge, and moved up the creek to the road. From there Booth went on alone while the others determined how the bridge should be blown. He crawled round the southern edge of Lane’s clearing until he reached the boundary between Heath’s and Lane’s. Then he wriggled forward until he could see his objective clearly. He lay concealed behind a log. Two Japanese sentries came and sat on the log for a long time. Booth could not move an inch. Insects bit him and he burned and itched. He did not arrive back at the assembly point until 10.30 and the start-time, originally fixed for midnight, had to be put back in consequence.

It had been raining but the same moon as had lighted the way for the Salamaua raiders was flooding the valley when Kneen began to lead his men forward at 11.30. Sergeant Booth remained at the bridge as cover for the two dynamiters while the rest moved on to the line of kapok trees which paralleled the road on the left and formed Heath’s front boundary. There they were to divide, Wylie’s section—trailed by Kneen, and Phillips with the NGVR group—to follow the line of trees and, concealed in their shelter from the road, kill the sentries at the top of the drive and move down the drive to cover the front of the house from the northern and western sides. Kneen and Phillips were to slip into position on Wylie’s left, help him cover from the north and themselves cover the eastern side. Doberer’s section and the mortarmen (without their mortar) were to strike diagonally across the property from the beginning of the kapok trees directly towards the house, killing any sentries they might meet on the way. Wylie was to open the attack by throwing hand grenades under the house. Booth, Murray-Smith and Hamilton were to rush forward after destroying the bridge and blow up the gun.

All went well. Doberer’s men were well on their way across the cleared area making for a few trees near the house. Then a dog began to bark from the drive. The men froze. The dog stopped barking. The men began to move and the dog began to bark. The dog woke the Japanese in the house and the raiders heard one shout as though to quieten it.

Meanwhile two men who had been detailed to kill the sentries near the entrance to the drive had found them in weapon-pits on the opposite side of the road. They stalked to within ten yards of them but could get no closer in the bright moonlight. They waited until they thought the main parties had had time to reach their positions, not knowing that Doberer’s men had been held up by the dog. Then they shot the sentries down and threw a grenade into their pits for good measure. It was 2.20 a.m. on 1st July.

The drive parties were almost in position but Doberer’s group was thrown off balance and moved back to the road. They joined Kneen in a

ditch on the Lae side of the drive. From this ditch fire was poured into the house and some of Wylie’s men were throwing grenades in and around the building. The steady crackle of fire filled the night. During lulls the raiders could hear groans and bumping noises from inside the house. Japanese trying to get clear were picked off. Then 15 or 20 of them broke out and made for the bush. They were allowed to go because, in a steadily settling mist, it was thought that they were some of Doberer’s men trying to improve their position. Through the rattle of the small-arms fire came a deeper explosion as the shattered bridge settled into the creek bed.

The Japanese gun opened fire. The first three or four shots passed over the raiders’ heads and fell in the vicinity of the Bewapi Creek bridge, but the next shot appeared to strike Kneen full in the chest and he fell dead. No provision had been made for the leader’s death and some confusion followed before Wylie took over. It was reported that a Japanese machine-gun was firing from the opposite side of the road and there seemed to be other indications that Japanese were at large in the area. The attackers withdrew after action had been joined for 15 to 20 minutes though little fire had come from the house itself. Orders for a special party to silence the gun were cancelled. There was no pursuit as the Australians fell back helping two of their men who had been wounded but leaving Kneen’s body behind.

Next morning bad weather hampered the attempts to strike Lae from the air and confuse Japanese retaliatory action against the raiders. Marauders (B-25s) attacked the town between 5.25 and 5.40 a.m. Of six Mitchells (B-26s) sent from Port Moresby three failed to find the target but three dropped bombs between 5.40 and 6.10 a.m. Despite these attacks Japanese fighters were busy strafing the road as soon as daylight came but they did no damage to the returning Australians. On the 2nd they made direct attacks on the Ngasawapum and Nadzab areas where some of the Australians were hiding but, in spite of some very narrow escapes, there were no casualties. There were further bombings again on the 3rd (at Gabmatzung and Gabsonkek) and strafing aircraft swept the roads.

The raid was not the success which had been hoped for. Heath’s still remained an obstacle to any large-scale movement against Lae although the house itself had suffered virtual destruction. The threatening gun remained in position. None the less an unexpected blow in the guerrilla tradition had been struck at the invaders. Fleay reported that the spirit of the men was excellent, that they had answered every call and had stood up extremely well under fire. He reported also “42 enemy killed, many others wounded” (but although an intense fire was poured into Heath’s for some twenty minutes and the occupants must have suffered heavily, there could have been no certain basis for this claim).

In anticipation of retaliatory action the Australians closed Camp Diddy and began to operate from a forward base south of the Markham—at Sheldon’s Camp, opposite Nadzab. The expected immediate movement

by Japanese ground forces did not take place along the Markham, however, but the invaders were active on the Salamaua side as July came.

By the 16th Kanga Force estimated that the Salamaua garrison had been increased to 400 or 500. Patrols continued to scour the foothills looking for the guerrillas and it became too dangerous for the Australians to retain the most forward observation posts. The old secret NGVR tracks were secret no longer and it was difficult for the scouts to move at all. The Japanese air forces were now sweeping wide and it seemed that a direct threat to the Bulolo Valley was growing. Komiatum and Mubo were bombed and strafed a few hours after the Salamaua raid. Nine bombers hit Wau on 2nd July. Next day the town was again bombed and strafed and five bombers also attacked Bulolo scoring a direct hit on one of the dumps, where two soldiers were killed and stores were destroyed. This loss, combined with large-scale desertions by carriers who melted away to the hills in face of the raids, seriously affected supply, and, among other things, caused the relief of the NGVR men still in the forward Markham area to be delayed.

On the 5th July Fleay ordered that the actions of Kanga Force be restricted to extensive patrolling and observation, except when Japanese patrols were met, presumably because his troops were tired and sick (particularly the men of the NGVR) and because of the shortage of supplies in forward areas. But now his men did not have to patrol to find action for it was coming to them.

On the 21st July McAdam’s men reported that a force about 100 strong was crossing the Francisco at the bridge near the airstrip. They were lightly equipped and were moving fast, guided by four or five natives—Tapi, a former police sergeant, Malo of Wanimo, Tuai of the Sepik, and Abalu of Busama. Above these men three seaplanes were making a close reconnaissance of the trail towards Komiatum. By 4.55 the leading troops were entering the Mubo strip clearing, having covered the distance from Salamaua in nine hours—fast going.

There were 64 Australians at Mubo, about half of them commandos and half NGVR. The rest were on patrol or were maintaining the Mount Limbong lookout. The 64 waited for the Japanese on the high ground overlooking Mubo village and the airstrip. When the Japanese entered “the gorge” they did so without any attempt at deployment and made a good target. The Australians engaged them with machine-guns from the heights and struck many of them down. The Japanese fire was erratic and caused no casualties among the defenders. By last light the invaders had had enough and fell back the way they had come, carrying their dead and wounded with them.

A captured document gave the original strength of the patrol as 136 and reports of the return of the Japanese to Salamaua indicated that they then numbered only 90. Malo and Tuai, who had been captured, said that the raiders had been recent arrivals at Salamaua and were naval troops. Both natives told of the presence of a European in Salamaua who had been working with the Japanese since before the Australian raid. Lieutenant

Murphy28 of Angau, a former patrol officer, was convinced that he knew the man.

He is particularly well acquainted with all the country between the coast and the Bulolo Valley and knows the Waria backwards. He is familiar with many out-of-the-way bits of the country and tracks, and is well known to the natives in the villages.

The attack on Mubo was apparently synchronised with a movement against the Australians along the Markham for the Japanese pushed out from Heath’s also on the 21st July. This sally followed a clash on the 19th.

The Moresby headquarters had asked Kanga Force for a prisoner. Two patrols crossed the Markham from Sheldon’s on this errand. One, consisting of Sergeant Chaffey,29 Privates Gregson30 and Pullar,31 and Rifleman Vernon, went past Heath’s along the river track then cut back on to the road to set an ambush between Lae and Heath’s, planning to cut off a supply truck and capture the driver. Chaffey had a Tommy-gun, the others had revolvers and grenades. About 2 p.m. a lorry came slowly up the road but bogged just short of the ambush position. Chaffey opened fire on two guards standing on the back of the truck. He killed one but the other dropped on the tray and opened fire with a machine-gun which he had set up there. Vernon came from behind a stump, dropped on one knee to steady his revolver, and received a burst of machine-gun fire in the chest. Chaffey fired the rest of his ammunition and thought he got two out of three men sitting in the front seat—but the revolvers of the others were of not much use against the machine-gun. Gregson went to help Vernon who said that he was done for and told the others to get out. He was bleeding badly and seemed to Gregson to have not much longer to live. As the other three dropped back into the bush they heard a single revolver shot and then a burst of fire. It sounded like Vernon having one last shot at the Japanese before he died. He had been one of the outstanding NGVR men on the Markham side.

Two days later came the Japanese thrust up the valley. The Australians had been keeping a standing patrol at a camp called Nick’s, close to and slightly west of Ngasawapum. Shortly before 21st July Lieutenant Noblett had established a new camp about 1,000 yards south of Ngasawapum and just off the Markham Road. Usually 16 to 20 men at a time worked from there patrolling the tracks to Narakapor, Munum and the Yalu area. On the 21st a relief was being carried out and there were two patrols at the new camp with weapons only for one as it was the custom of the relieving patrol to take over the weapons of their predecessors. About 1.30 p.m. two shots were heard from the direction of the Markham Road

and parties went out to investigate. Corporal Jones32 took two men down a “short cut” but ran into a Japanese party led by a native. Both groups opened fire and the native was one of the first casualties. Outnumbered, Jones’ men made their individual ways back to Nadzab, but he himself was cut off and forced to hide in the thick growth.

Fire was opened on the camp from several different directions. It was obvious that the Japanese were there in force and the Australians fell back in small groups to Nadzab and Sheldon’s, leaving most of their gear behind them. Jones was the last man back. He said that he had counted two parties, one of 81 and the other of 53, both led by natives. It was thought that the Japanese had suffered 6 casualties and two of their native guides had been wounded.

Private Underwood33 was wounded and missing. Warrant-Officer Whittaker,34 formerly an Administration Medical Assistant, who was running a small hospital at Bob’s, heard this. As far as anyone knew the Japanese were still at Nick’s. Whittaker said later:

I went back and got Bill Underwood out after he was wounded. I had to go six hours to get him. I set out at 1730 and got to Ngasawapum hours later, went into the bush in the area where he was shot, went into the camp, called quietly, and he answered. I bound him up. I walked him back to Nadzab to where a canoe was waiting, got him to Sheldon’s and on to Bob’s Camp at 0730.

Natives said afterwards that the Japanese burned Munum village on their way up the valley to punish the inhabitants for “going bush” when they arrived; that before the raid four Ngasawapum and three Gabsonkek boys had been closely questioned by the Japanese so that the latter must have known a good deal about the activities of the Australians before they started out. It was also said that four natives captured at the camp during the raid were flogged and threatened and then allowed to go.

From this time forward the fortunes of Kanga Force suffered a marked decline. This was due to a number of causes—the effects of sickness and strain among the troops, vigorous Japanese efforts to rid themselves of their turbulent neighbours and their constant threat of advance over any of seven or eight routes, lack of reinforcements, a threatening new crisis with regard to supply. The last three at least were conditioned to a large extent by Japanese action elsewhere for, on 21st July (the same day as the raids on Mubo and Nick’s had taken place) invading forces landed on the north coast of Papua and began to push vigorously over the Owen Stanley Range, constituting a threat which bore daily more heavily on the maintenance plans for Kanga Force—plans which even under the most favourable conditions had never produced a smooth flow of supplies to the guerrillas.

The supply line through Bulldog had failed to come up to expectations.

By improving the track, building bridges and rest camps, and re-organising the carrier lines, it had been hoped to make the track carry 6,000 pounds daily, but it never provided anything like that figure. Aircraft could have been used either to supplement deliveries over this track or replace them almost completely, but General Morris did not have aircraft. As late as early August he had none stationed permanently at Port Moresby and, in his efforts to get some, did not hesitate to say that, through their lack, his forward troops were “liable to starvation”. Nor, when they did begin to be available, did Kanga Force figure largely as a commitment for their services as, by that time, a far more urgent need had developed in Papua.

So the outbreak of serious fighting elsewhere increased Kanga Force’s difficulties. Even after the raid on Salamaua Winning’s men had to rely to a large extent on Umphelby’s rapidly diminishing reserves as Winning said that he had then, at one time, only 11 tins of soup and 7 pounds of rice to feed 72 men, with no tea or sugar. On 10th July he and Umphelby went to Wau to stress the difficulties of their food situation, largely responsible, he claimed, for the fact that only 23 of his 49 men then at Mubo had been reported fit for duty on the 5th. Considerable improvement in the circumstances of his own group followed this visit but elsewhere in the forward areas bad conditions had prevailed and the men, besides becoming rapidly weak and unfit, found their tempers fraying and their spirits drooping.

An example was a message sent back to Howard by one of his officers, Lieutenant Littlejohn,35 who was watching the Mapos Track. It was dated 16th June and was written in pencil on a piece of paper six inches by four.

To us the tobacco position is still most unsatisfactory. You tell us 82 tins have been sent and more were sent to make up a three weeks’ supply. Then you say our issue is 70 tins. Also that 14 tins went forward with Private Pearce.36 Pearce denies this. I am not interested in how much we should have but where is it? To whom was the mythical 82 tins of tobacco given? Where is the 70 tins (2 weeks’ supply)? Who gave Pearce the tobacco to bring out here? The fact remains that we have no tobacco (not even stock tobacco), have received none and want some badly. If 82 plus 14 tins have gone astray it is time somebody found out where it has gone to.

This question of supply pivoted on the evergreen problem of securing and keeping native carriers—one which had been aggravated by the early July air raids and which, particularly in the forward areas, became more acute as July advanced. Japanese intimidation tactics and the difficulty of getting native rations forward to feed carriers had a cumulative effect. Patrols had to be restricted, reliefs and other troop movements could not take place.

On the 27th July Captain Lang,37 who had succeeded Kneen and was

in charge of the Markham area, reported that 40 boys had deserted from Bob’s the previous night and that lack of carriers was holding up his patrols. On the 28th he reported the desertion of 40 more carriers—from Partep 2 (on the Wampit River Track forward of Zenag)—and said that the Japanese had threatened to bomb Old Mari village (south of the Markham between Bob’s and Sheldon’s) if Australian patrols crossed the river. In consequence the local natives were reluctant to supply labour and he had to rely entirely on overworked mules to supply outposts at Sheldon’s and Kirklands.

The position is therefore very serious (he wrote). Any Jap bombing or strafing along our L of C will disrupt our supply line for some time. This may even occur as a result of threats and rumours, and we have no permanent line of labour. We cannot use force since we have none. ... We can do nothing to protect these natives who help or have helped us in the past largely on promises.

We now cannot obtain labour on the north side of the Markham and we are now seeing a rapid, inevitable and progressive diminution this side. The Jap technique with natives has never been bad and is improving. Moreover they are not even trying yet, since no bombs have fallen this side.

Partly as a result of all these problems of supply, partly through the general strain of warfare in the country where Kanga Force was operating, weakness and sickness rapidly thinned the ranks of the guerrillas. Naturally the men of the NGVR were suffering most. McAdam’s scouts, most active and successful of all groups under Fleay, had worked themselves to a standstill and had to be relieved. A 2/5th Independent Company party took their places, led by Sergeant O’Neill who had developed into an outstanding scout in the NGVR tradition. By 7th August Fleay told General Morris that all troops forward of Bulolo and Wau were AIF (although this was not entirely correct as some individuals, like Rifleman Pauley38 at Mubo and Sergeant Emery at Sheldon’s, remained to act as scouts, observers and contact men with the natives, and the NGVR was to be represented in some form in the area until the guerrilla period finally ended). But even the relatively fresh AIF men were suffering badly. By early August Fleay had found it necessary to relieve Howard’s detachment at Mapos as there were not sufficient fit men left there to send out a patrol. On 31st August headquarters at Moresby were told that the total effective strength of the 2/5th Company had been reduced to 182 although the company had come into the area 303 strong.

This dreary situation had been partly relieved by some attempts to make life easier for the force during July and August. Accommodation at Mubo was improved by the erection of huts, a forward hospital unit was opened at Guadagasal on the 2nd August, an attempt was made to establish a canteen at Wau. But the history of that canteen probably provided the perfect example in miniature of the failure to keep Kanga Force supplied, for it was able to remain open for only a fortnight. At the end of that time all stock had been sold and the canteen closed.

Although the background picture was thus darkening there were men in the force who refused to be depressed. One of them was the energetic Winning who was not content to sit idle at Mubo. For some time reports had been coming of a Japanese gun sited at Busama and Winning determined to investigate them. On 19th August he took a patrol out from Mubo. He found that the natives at Busama were very pro-Japanese and had warned his enemies of his coming. He saw 60 Japanese disembarking from three barges soon after his arrival, but found no gun and no evidence of Japanese concentration. His observations at Busama convinced him that the village was the centre of a deception plan, “that the Jap during the day as a blind merely moved up and then moved back under cover of darkness”. He had been uneasy before this about possible large-scale movements against Mubo where he had left 49 men under Captain Minchin,39 and had sent a note to Minchin telling him not to move out with a patrol as he had proposed to do. Now he sent Minchin a second note stressing that the Japanese activity was “a blind” and followed it with a third, while, with his party, he struck out through the Buangs for Bulwa.

Meanwhile both Fleay, back at Wau, and Minchin, had been reacting to reports of Japanese movements which had reached them. Heeding, apparently, a report from Mubo about 27th August, Fleay informed Moresby that 200 Japanese had moved to Busama. By the 29th he was reporting that the numbers had grown to 300, that the Japanese were concentrating stores at Busama, and had obtained natives to guide them thence to the Bulolo Valley.

But even more disconcerting news was at hand. A 6,000-ton transport, with a destroyer for escort, was in the harbour at Salamaua on the 27th. Several hundred troops and stores, including motor vehicles, were unloaded on the night 28th–29th August. Next, Kanga Force informed Moresby that three sampans had been carrying an estimated 200 to 300 troops to Lokanu, a coastal village a few miles south of Salamaua.

Fleay decided that simultaneous attacks on Mubo from Lokanu, and on the Bulolo Valley from Busama, were likely. He asked for reinforcements, knowing that the 2/6th Independent Company had arrived at Port Moresby on the 7th August and had originally been intended to augment his force. But Lieut-General Rowell, who had taken over from Morris at Moresby about two weeks earlier, was watching an uneasy situation develop just south of Kokoda where a mixed force was fighting hard to stop the Japanese penetration which had developed from landings at Gona on the 21st July, and was apprehensive of the consequences of a Japanese assault on Milne Bay which had started on 26th August. Fleay was told, therefore, that he would have to do the best he could with what he had and that there was little prospect of the other company joining him.

At Mubo on the 29th Minchin received news that 130 Japanese had been seen entering the valley of the Francisco River. He then left Mubo with a patrol of 20 men meaning to intercept the Japanese near Bobdubi.

On the way, however, he saw the Japanese approaching Komiatum by another track. Hastily he warned Wau by radio from the nearby observation post where Pilot Officer Vial had originally been established40 and, assuming that he was cut off from Mubo, set out for the Bulolo Valley across the main range.41

By the morning of the 30th Fleay had made up his mind that Mubo was about to be attacked from three sides—from Komiatum frontally, from Lokanu on the right, and from Busama on the left. He reported later:

We had only a small garrison at Mubo, and orders were issued to this party that if forced to withdraw they were to fall back on Kaisenik. No defensive position is possible between Mubo and Kaisenik owing to the nature of the country.

His feeling of insecurity was strengthened by uncertainty concerning the actual numbers advancing on Mubo; he estimated that there were about 1,000 Japanese in that vicinity. Whatever the number was it was obviously too many for Lieutenant Hicks,42 who had been left at Mubo with 29 men. By 2 p.m. Hicks had reported that his enemies were closing in on him. Now Fleay made up his mind.

It appeared obvious that the Japanese would continue their advance to the Bulolo Valley (he wrote subsequently). If so the enemy could reach the Kaisenik area by the night of the 31st August, thereby cutting off our planned move to the defensive position near Winima [two hours’ walk south of Kaisenik].

It now became apparent that the movement of troops and stores to the Kaisenik area would have to proceed with all speed. It was decided to carry out demolitions under cover of darkness and as twelve hours was required for the completion of demolitions, orders were given to commence at nightfall 30th August 1942.

At 3 p.m. on the 30th Fleay issued instructions for the “scorching” of the Bulolo Valley and withdrawal to Winima and Kudjeru. His plan was to form a line in the Kaisenik–Winima area and carry out his secondary role—to hold the Bulldog Track. Troops from along the Bulolo Valley were ordered to report at once to No. 6 Camp near Wau. There rations for the march were handed out, arms and ammunition were distributed for carrying.

As darkness fell the camp buildings and any others still standing in Wau township were set alight. Equipment, stores, ammunition that could not be carried, blazed in great fires. At Bulolo, Bulwa and Sunshine, the demolition parties worked steadily with petrol and dynamite. The night resounded with explosions and demolition charges were blown on the Wau and other aerodromes, roads were cratered and bridges shattered.

By midnight the main body of troops was clear of the smoke and glowing embers that marked Wau. Trucks could be used to Crystal Creek, three to four miles South-east of Wau. After that the job was a marching and carrier-line one. Confusion manifested itself for a time, with a growing and untidy accumulation at Crystal Creek, equipment abandoned along the track, carriers deserting.

Not all of Fleay’s men, however, took the track through Kaisenik during the main movement. Lieutenant Hicks did not report at Blake’s Camp (one hour and a half south of Winima) until 2nd September. He had sent a runner before him to say that the Japanese, 900 strong, had entered Mubo from three sides at 2.30 p.m. on 31st August. He had withdrawn before the Japanese, his men carrying what weapons they could and hiding the rest. His force was intact and had inflicted some casualties on the Japanese. They had not suffered casualties themselves. On their way down they passed a patrol of 20 under Lieutenant Wylie who, Fleay said later, had been sent to reinforce the garrison. But Wylie and his men went on alone to keep contact with the invaders. On the night of the 5th–6th September one of their small patrols got close enough to Mubo to observe the Japanese dispositions and two nights later another patrol found the enemy in considerable strength on Garrison Hill, just west of the village. The Japanese were at Mubo to stay.

Farther down the Bulolo Valley Winning and his patrol from Busama arrived at Bulwa on the 3rd and found the area burnt and their friends gone. They came up the valley some days in the wake of the main body.

But the men whose position gave real cause for anxiety were those elements of Lang’s company which were still operating in the Markham area. Earlier they had been concerned about the spread of Japanese influence south of the river. Their own patrolling during August, however, had suggested that this concern might have been over-emphasised and by the end of the month a patrol which had been across the river was of the opinion that the time was favourable once more for an attempt by some of the former Administration officers to re-establish contact with the natives there and for the establishment of a permanent patrol east of the river. The withdrawal of the main body from the Bulolo Valley, however, gave them rather more urgent matters to attend to since their supply line was broken and it seemed likely that the line of their withdrawal was also to be severed.

Thus, with the end of August, came to an end the first phase of the irregular operations in the Salamaua–Lae–Wau area. The Japanese were poised at Mubo within easy striking distance of Wau and the Bulolo Valley but had not yet thrust up the Markham in any force; the Australians had abandoned the Bulolo Valley and the town of Wau, left them smoking behind them, and were hastily preparing to fight at the head of the Bulldog Track.