Chapter 2: The Island Barrier

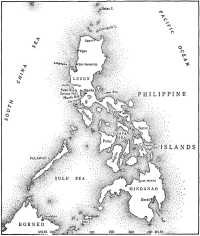

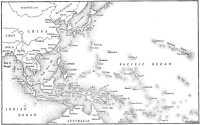

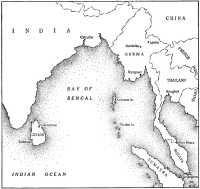

For many years Australians, uneasily peering northward, had comforted themselves with the contemplation of the great arc of islands which stretches from the Pacific by way of the island mass of New Guinea and beneath the centrepiece of the Philippines, through the East Indian archipelago to the Indian Ocean. These islands, particularly in the northeast, seemed a barrier to invasion. But few Australians had much knowledge of them, and the military leaders mostly shared the general ignorance. After the fall of Java in March 1942, the only places where fighting was taking place along this island barrier were Timor, where an Australian Independent Company was at large, and the Philippines.

When General MacArthur left for Australia on 12th March there was confusion in the Philippines over the command arrangements. He did not tell the War Department in Washington that he had divided the forces in the Philippines into four commands, which he planned to control from Australia, and of which Major-General Wainwright was to command only one—the troops on Bataan and small pockets holding out in the mountains of Luzon. Both President Roosevelt and General Marshall assumed that Wainwright had been left in overall command. He was accordingly promoted Lieut-general and moved to Corregidor on the 21st. On the same day MacArthur informed Marshall of his own arrangements. Marshall considered them unsatisfactory and told the President so. Roosevelt thereupon made it clear to MacArthur that Wainwright would remain in full command.

Major-General Edward P. King took over Luzon Force from Wainwright. The total strength was then 79,500 of whom 12,500 were Americans. On 3rd April General Homma’s XIV Army fell upon them with reinforced strength. The defence crumbled, and on the 9th King surrendered his force. On the same day Wainwright wrote to MacArthur that he considered “physical exhaustion and sickness due to a long period of insufficient food is the real cause of this terrible disaster”. Some years later he wrote:

I had my orders from MacArthur not to surrender on Bataan, and therefore I could not authorise King to do it [but he] was on the ground and confronted by a situation in which he had either to surrender or have his people killed piecemeal. This would most certainly have happened to him within two or three days.1

Up to this time the island fortress of Corregidor, where Wainwright had his headquarters, had been under heavy but intermittent aerial and artillery bombardment. The aerial bombardment had begun on 29th December but waned after 6th January, when Homma was left with only a small air force which he could spare for use against the island only in sporadic

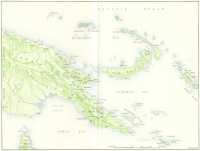

Papua and New Guinea

small attacks; the artillery bombardment began on 6th February from guns sited on the southern shore of Manila Bay. On 15th March it entered a new phase with thickened fire aimed at the four fortified islands in the bay, particularly the two southernmost ones. The shelling decreased once more as the Japanese prepared their final concentrations against Bataan, there was a period of intensified air attack when air reinforcements reached Homma, then, with the beginning of April, there came a temporary respite for the island garrisons as the Japanese moved into Bataan. From the 9th onwards, however, Homma was free to throw all his weight against the islands, with guns sited on both sides of the bay.

The shelling never really stopped. With over one hundred pieces ranging in size from 75-mm guns to the giant 240-mm howitzers, the Japanese were able to fire almost steadily. They destroyed gun emplacements, shelters, beach defenses, buildings—almost everything on the surface—at a rate that made repair or replacement impossible.2

At the beginning of May the Japanese guns and aircraft let loose their final fury. On the 4th some 16,000 shells fell on Corregidor from Bataan. The defenders (11,000–12,000 effectives after the Bataan surrender) had suffered 600 casualties since 9th April, and were shocked and weak; most of their coastal guns were destroyed. But on 5th May they sustained “the most terrific pounding” they had yet received. “There was a steady roar from Bataan and a mightier volume on Corregidor.” That night Japanese troops landed on Corregidor. Though they fell into confusion during their approach and were met with stout resistance at some points, Wainwright decided on the morning of the 6th that further resistance would result in a wholesale slaughter of his men, particularly 1,000 who were lying wounded and helpless. He sent a message to President Roosevelt that he was going to meet the Japanese commander to arrange for the surrender of the fortified islands in Manila Bay.

This proposal left the position in the south unresolved. There, beyond small landings and the establishment of a fairly static garrison at Davao, in Mindanao, in December, Homma had not been able to make any move. On the morning of the 10th, however, he began a series of landings with a force under Major-General Kiyotake Kawaguchi playing a leading part. By 9th May Brigadier-General Bradford G. Chynoweth’s forces on Cebu (about 6,500 strong) were scattered and Chynoweth himself was in the mountains hoping to organise further resistance from there; on Panay Colonel Albert F. Christie with 7,000 men had fallen back in an orderly fashion into well-stocked mountain retreats from which he was preparing to wage guerrilla war; on Mindanao the bulk of Major-General William F. Sharp’s forces had been destroyed.

Wainwright made desperate efforts to avoid the surrender of the troops in the south. About the same time as he first broadcast a surrender offer from Corregidor he told Sharp that he was releasing to the latter’s command all the forces in the Philippines except those on the four fortified islands in Manila Bay and ordered him to report at once to MacArthur. Almost at the same time Sharp received a message from MacArthur himself (sent in the knowledge of the Corregidor surrender but without knowledge of Wainwright’s action in relation to Sharp) in which MacArthur assumed command of the Visayan-Mindanao Force. But when, in the late afternoon of the 6th, Wainwright was taken to meet Homma, the Japanese refused to treat with him except as the overall commander in the Philippines and sent him back to Corregidor to think the matter over. Late that night Wainwright told the local Japanese commander that he would surrender all the forces in the Philippines within four days. This decision inevitably led to great confusion in the south. Sharp, bewildered as to

The Eastern Theatre

where his duty lay, finally made his own difficult decision and directed his subordinates to capitulate. Chynoweth was reluctant to do so and Christie, who was in a particularly strong position, bluntly questioned Sharp’s authority to issue a surrender order and asserted that he did not see

“even one small reason” why he should surrender his force, because “some other unit has gone to hell or some Corregidor shell-shocked terms” had been made.3

In the final event, however, the general surrender became effective, though the wide dispersal of all the defending forces throughout the islands delayed the process.

Although the reduction of the Philippines and the defeat of the American-Filipino army of 140,000 men, took far longer than the Japanese had planned, they did not allow the delay to hold up unduly their plans for a southward advance. Their main movement had swept round the archipelago and, by the time Wainwright surrendered, they were firmly established in New Guinea and at other points in the South-West Pacific adjacent to Australia.

Australia’s main interest in the Pacific war was to be directed towards Papua and New Guinea in which, apart from their strategic importance, she had a direct interest through her responsibility for their government, but there were other Pacific islands to which she also had a responsibility, or which were of such significance in her planning that she was forced to interest herself in them.

Of these New Caledonia had seemed in 1941 and early 1942 to be one of the most important. The 2/3rd Australian Independent Company (21 officers and 312 men), which had been sent there in December, was powerfully reinforced on 12th March with the arrival of the major part of an American task force, commanded by Major-General Alexander M. Patch, consisting of two infantry regiments, a regiment of artillery, a battalion of light tanks, an anti-aircraft regiment, a battalion of coast artillery and a squadron of fighter aircraft. (Later, when the South-West Pacific Area was defined, New Caledonia was not included in it and the responsibility for its defence shifted entirely to America and New Zealand.)

Still farther out in the Pacific, about 2,200 miles Northeast of Sydney and some 200 miles apart, lay Ocean Island and Nauru, both rich in phosphate deposits. Late in February Australian field artillery detachments which had been stationed there in 1941 were withdrawn in the Free French destroyer Le Triomphant, which made a quick dash first to Nauru and then to Ocean Island, took off those who were to leave and trans-shipped them to the Phosphate Commission ship Trienza which was standing by in the New Hebrides. The Trienza then cleared for Brisbane.

Small parties of Europeans remained on both islands—six on Ocean Island, seven on Nauru. The Administrator of Nauru, Colonel Chalmers,4

did not leave. He had served in the South African War, and in the 1914–18 War with the 27th Battalion which he commanded from October 1917 onwards. In a letter which he sent out by Le Triomphant to his Minister he wrote: “We will do our best here whatever may happen.” Although his whole Administration staff volunteered to remain he kept with him only Dr B. H. Quin (Medical Officer), W. Shugg (Medical Assistant) and two volunteers from the Phosphate Commissioners’ staff—F. F. Harmer and W. H. Doyle. Fathers Kayser and Clivaz, missionaries, also remained.5

South and South-west of Nauru and Ocean Island are the New Hebrides (under joint British and French control) and the Solomon Islands (a British Protectorate) where detachments of the 1st Independent Company had been stationed during 1941 to protect aerodromes and seaplane-alighting bases and to man observation posts; a secondary task was to train local inhabitants including natives to undertake these duties. In January 1942 the line manned by these detachments and the rest of the Independent Company ran in a North-westerly direction from Vila (New Hebrides), through Tulagi and Buka (Solomons), Namatanai and Kavieng (New Ireland) to Manus Island in the Admiralty Group. Thus, with the garrison at Rabaul, the 1st Independent Company constituted the Australian “advanced observation line”.

After the war with Japan had begun the men of this company found themselves working closely with the well-planned naval coastwatching network in the islands—an organisation whose task in time of war was to report to the Navy Office instantly any unusual or suspicious happenings, such as sightings of strange ships or aircraft, floating mines, and other matters of defence interest. Among the coastwatchers were included District Officers, Patrol Officers, other officials, and planters, of the Territories of Papua and New Guinea and the British Solomon Islands.

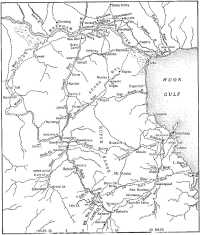

Throughout these areas the occupation of Rabaul on 23rd January was the pivot on which the whole Japanese movement swung. The invaders had made air reconnaissance of the islands of practically the whole Territory of New Guinea—and much of the protectorate—beforehand. On the 21st they bombed Kavieng in New Ireland, Lorengau in the Admiralties, and Madang, Lae, Salamaua and Bulolo on the New Guinea mainland. On the same day that they landed at Rabaul they occupied Kavieng, and their aircraft raided the Trobriand Islands, off the South-eastern tip of the New Guinea mainland. On 3rd February they first raided Port Moresby from the air.

Bougainville Island in the northern Solomons, New Ireland, New Britain, the Admiralty Islands, and the eastern half of the mainland of New Guinea, with their many hundreds of adjacent small islands, were Australian territory. The South-eastern part of the New Guinea mainland and the

smaller islands off its coast formed the Territory of Papua. In 1884 Great Britain proclaimed a Protectorate over this area, and it became Australian territory in 1906. In the first weeks of the 1914–18 War an Australian military force had taken from the Germans the northern part of the eastern half of the New Guinea mainland, New Britain and the arc of islands running from the Admiralties to Bougainville. At the Peace Conference Mr Hughes had demanded possession of these island “ramparts” for Australia to keep them from “the hands of an actual or potential enemy”. Australia was given a Mandate over them in 1920, and in 1921 a civil administration was established.

Papua included some 91,000 square miles of country, the Mandated Territory 93,000, lying completely within the tropics with the characteristic high tropical rainfall and hot-moist climate, though conditions in the high valleys and plateaus of the hinterland may be cool and bracing and the highest mountain areas are bitterly cold. The mainland is dominated by towering and broken mountains, the lower and middle slopes of which are covered densely with rain forests, the higher blanketed with moss. The backbone of the mountain system is the great central spine which runs in a general east-west direction and rises to 15,400 feet. A few of the islands are atolls but most are of the “high” type and share the mainland features—mountains, dense vegetation and rushing river systems.

In 1939 the European population of these Territories, living almost entirely on the coastal fringes, was about 1,500 in Papua and 4,500 in the Mandated Territory, their respective centres being Port Moresby and Rabaul. The native population was probably in the vicinity of 1,800,000—mostly primitive tribesmen, separated by a multiplicity of languages, cultures and social organisations; inter-tribal fighting was the rule among them and ceased only as European influence spread.

When the war came the local administrations in the two Territories, though separate, were similar in form. There were nine magisterial divisions in Papua, each under a Resident Magistrate with a small staff of Assistant Resident Magistrates and Patrol Officers to assist him. In the Mandated Territory there were seven Districts each under a District Officer assisted by Assistant District Officers and Patrol Officers. Although the local officials exercised both administrative and judicial powers over all individuals and activities within their districts, their most important and extensive duties related to natives and the development of areas of European control. Each Territory maintained a native police force officered by Europeans.

Thus far the comparatively short period of Australian administration in both Papua and New Guinea, the tremendous physical difficulties of the country, and the comparative slenderness of the Australian resources had combined to prevent the whole area from being brought under effective control. By 1939, for example, less than half the Mandated Territory was officially classified as “under control”, about 18,000 square miles were considered to be “under influence” in greater or less degree, and some 5,500 of the remaining 36,000 square miles were classed as having

been “penetrated by patrols”. But exploration and the spread of influence was being persistently carried out by hardy officers who had built up a fine record of peaceful penetration:

The patrols showed great restraint—the orders were rigid—in the face of frequent native hostility. Not a few officers and police were killed in open fights and ambush. Drawing-room pioneers understress the natural savagery of the New Guinea scene. The relatively peaceful spread of white influences over both areas was a remarkable achievement.6

Economic development was substantially limited to copra and rubber production in Papua, copra production in New Guinea and mining in both Territories—with the greatest mining development on the goldfields of the Bulolo Valley in New Guinea. There were more than 500 coconut plantations in New Guinea which produced 76,000 tons of copra for export in the peak year 1936–37. That year Papua exported 13,600 tons. In its best years the Papuan rubber industry could produce about one-eighth of Australia’s requirements; in 1940–41 exports were 1,273 tons. Gold production in the two Territories between 1926 and 1941 was valued at about £22,580,000. Of this £19,000,000 was won in the Mandated Territory, most of it from the Bulolo Valley fields, which were almost completely dependent for service and maintenance upon aircraft, the use of which had been developed to a degree probably unparalleled in comparable circumstances elsewhere in the world.

For unskilled labour, economic enterprises of all kinds relied almost completely upon the natives. Although there was a small body of casual labour working under verbal agreements most natives worked as indentured labourers under voluntary contracts of service (usually for three-year periods in New Guinea; 18 months to 2 years in Papua) which defined the conditions of their work and depended upon penal sanctions for their enforcement. In 1940 there were about 50,000 indentured labourers at work in both Territories—under a system, incidentally, which, it was becoming increasingly clear, would have to be superseded by a free labour system, despite the fact that

the protective legislation was of good model and by far the most important and well-policed body of civil law in the territories. Working under indenture was agreeable to the natives and had become of some positive social and economic importance to them. An increasing volume of labour offered itself without direct compulsion.7

There was little real general Australian interest in Papua and New Guinea before the war; little general appreciation of the fact that Australia was the major colonial power of the South-West Pacific; and virtually no military knowledge of the region and no appreciation of the tactical and logistical problems it would pose in war.

As far back as 18th March 1941, the War Cabinet had approved that women and children not engaged in any essential work in New Guinea and other Territories should be encouraged to leave unobtrusively for

Australia. In November it was decided that further encouragement should be given to these people to leave, with a strong warning that it might not be possible to make any special arrangements in the event of war. On 11th December, the War Cabinet endorsed a decision of three days before that there should not yet be any compulsory evacuation of women and children from Papua and New Guinea. Next day they reversed this decision, and by 29th December about 600 women and children had left the islands and it was considered that the evacuation had been substantially completed. None the less a number of women (other than missionaries and nurses to whom the orders did not apply) still remained. As for the civil male population, a proportion was, for some time after the occupation of Rabaul, to constitute something in the nature of a leaderless and difficult legion although many civilians, both from inside and outside the Administration, were to render heroic service and those who were fit and eligible were gradually called up, or voluntarily enlisted, in various branches of the three Services.

On 8th December 1941 Brigadier Morris who commanded the 8th Military District (i.e. all troops in Papua and New Guinea) had been authorised to call up for full-time duty the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles (NGVR), a force manned by some of the local European inhabitants of the Mandated Territory. On 25th January, two days after the fall of Rabaul, the War Cabinet decided that all able-bodied white male British subjects between the ages of 18 and 45 should be called up immediately for service. But by this time civil control throughout the Mandated Territory had been disrupted and the Administrator, Sir Walter McNicoll, was on his way to Australia.

By this time also a difficult situation was developing in Port Moresby between the Administrator of Papua (Mr Leonard Murray8) and the army commander. Murray had been in the Papuan Administration for more than 30 years and was a nephew of the distinguished former Lieutenant-Governor of Papua, Sir Hubert Murray, who had built most carefully between 1908 and 1940 the form and tradition of the Papuan Service which his successor was now understandably reluctant to see submerged beneath the weight of a military administration. Morris was a regular soldier who had been in the Middle East in charge of the Australian Overseas Base before his appointment in May 1941 to command the 8th Military District. A gunner by training he was an unassuming and courteous man with a strong sense of duty and much sound common sense. He recognised bluntly the military necessities of the circumstances which had now developed.

The situation which arose between Morris and Murray was best exemplified by the difficulties which manifested themselves late in January over the calling up for military service of the local white residents. When, on 27th January, Morris issued the call-up notices to men in the 18 to 45

years age group his action inevitably caused the dosing of the commercial houses and, just as inevitably, signified the actual if not the legal end of the civil administration and the substitution of the military commander as the supreme authority in Papua. The difficulties of divided control became accentuated and the processes of civil administration rapidly became more and more confused, particularly after Japanese air raids on Port Moresby on 3rd and 5th February which caused panic among the natives. After the second attack the civil administration was unable to maintain order in the town. On the 6th the Administrator was told that the War Cabinet had approved the temporary cessation of civil government in Papua. This decision was gazetted in Canberra on the 12th. The Administrator published a Gazette Extraordinary on the 14th stating that civil government had ceased at noon that day; he left for Australia on the 15th and, that day, Morris issued an order by which he assumed all government power.

Many of the functions of civil administration had to be maintained and it was necessary particularly to preserve, as far as possible, control of native labour. The authority of both the Government and the private employers had already broken down, or was fast doing so, in many areas, so that conditions of anarchy quickly developed among the natives of those areas. It was also most desirable that the Territories’ production of copra and rubber should continue to the greatest possible extent. Early in March Morris posted most of the officers of both civil administrations, and many other men experienced in the Territories, to two new units—the Papuan Administrative Unit and the New Guinea Administrative Unit. Lieutenant Elliott-Smith9—formerly Assistant Resident Magistrate at Samarai who had been called to Port Moresby late in January to work on Morris’ staff as a link between the military and civil authorities—organised the Papuan, and Captain Townsend,10 formerly a senior District Officer in the New Guinea Administration, the New Guinea Administrative Unit. The two units were merged on 21st March and became the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit—Angau—to function as a military administrative unit for both Territories. At that time Angau was divided into a headquarters and two branches: District Services—to police the Territories and maintain law and order, regard the welfare of the native people, and to provide and control native labour; Production Services—to provide the food required by the natives, transport for the men of the District Services and those working the plantations, and technical direction for production.

The other forces which Morris commanded consisted in the main of the 30th Brigade Group. In February 1941 the Australian Chiefs of Staff had directed attention to the possibilities of a Japanese advance by way of New Guinea. Out of that had come a decision to send the 49th (Queensland) Battalion

to Port Moresby, where one of its companies had been since July. This battalion had been formed as a result of the division of the 9th/49th Battalion into its two original components; each battalion then completed its establishment with volunteers for islands’ service. But the 49th contained a great many very young soldiers and, until well into 1942, was considered to be neither well-trained nor well-disciplined. At the time of the main party’s arrival in March 1941, the Port Moresby defence plans centred on the Paga Coastal Defence Battery of two 6-inch guns. The defence of these guns was the basic task of the 1,200 men of the garrison. After the warning on 8th December by the Australian Chiefs of Staff that the Japanese would soon attempt to occupy Rabaul and Port Moresby, General Sturdee’s assessment that the minimum strength required at each of these two places was one brigade group, and a decision that Port Moresby (and Darwin) must be considered second only to the vital Australian east coast areas, efforts were made to reinforce these outposts. The 39th and 53rd Battalions, and other units of the 30th Brigade, arrived at Port Moresby on 3rd January. But these reinforcements were also very raw and very young. (One calculation later placed their average age, excluding officers, at about 18½)11

The 39th Battalion was a Victorian unit which had been formed in September 1941 from elements of the 2nd Cavalry and the 3rd and 4th (Infantry) Divisions; some units had sent good men to the new battalion, but others had taken the opportunity to “unload” unwanted officers and men. The commander, Lieut-Colonel Conran,12 who had served in the 1914–18 War, had tried to ensure that each of his companies would be commanded by an old soldier who would also have another veteran as his second-in-command. He had been vigorous in training. In November a spontaneous and widespread move by men in the battalion to enlist in the AIF had been frustrated because recruits for that force were not then being accepted.

The 53rd Battalion, however, had had rather a different history. Up to November 1941 it had been part of the composite 55th/53rd (New South Wales) Battalion, but was then given separate identity, “specially enlisted for tropical service”, and marked for movement to Darwin. In developing its separate form, however, it was made up from detachments from many units in New South Wales and (as often happened in such cases) was given many unwanted men from those units. At the time of its formation most of the men had had three months’ militia training though about 200 of them had been called up as late as 1st October. As its embarkation date approached towards the end of December many of its members were illegally absent, bitter because they had been given no Christmas leave, so that, just before it sailed, its ranks were hastily filled with an assortment of rather astonished and unwilling individuals gathered from widely varied sources. Consequently it was a badly trained, ill- disciplined

and generally resentful collection of men who landed at Port Moresby on 3rd January as the 53rd Battalion.

These three inexperienced and ill-equipped battalions-39th, 49th and 53rd—had the 13th Field Regiment and the 23rd Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery to support them. (The original establishment of the anti-aircraft battery was increased by the diversion to Port Moresby of additional anti-aircraft guns which had been destined for Rabaul so that, by March, it was organised on the basis of a fixed station of four 3.7-inch guns at Tuaguba Hill and three mobile 3-inch gun stations whose positions were changed frequently.)

Morris also had two units of local origin which spread wide as a reconnaissance screen. The first was the Papuan Infantry Battalion (PIB), consisting of Papuan natives, led by Australian officers and a number of Australian NCO’s. The nucleus of this battalion had been formed as one company in June 1940, through the efforts of Major Logan,13 a Papuan police officer, who became its first commanding officer. Soon after Japan came into the war Logan was succeeded by Major Watson,14 a bluff outspoken man, quick in thought and speech, who had been with the PIB since its formation. He had served as a young artillery officer in the old AIF and had won a reputation for great personal courage. He was one of the old hands in New Guinea, had “made his pile” in the gold rush days and was disappointed that only a few of his junior leaders were New Guinea identities. Most of them had been brought in from various units serving in the Moresby area—notably from the 49th Battalion—as the second and third companies were formed during 1941. Since the value of this unit was seen to lie chiefly in its knowledge of local conditions, and its main role would be scouting and reconnaissance in which the bushcraft of the natives could be used to the fullest extent, the disadvantages of having officers and NCO’s who were not experienced in the country were obvious. Morris, however, soon had the Papuans operating in the role for which they had been enlisted and, by February, Lieutenant Jesser15 and his platoon were patrolling the Papuan north coast from Buna to the Waria River, while other platoons were screening lines of possible approach closer to Port Moresby.

The second local unit was the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles. So scrupulous had the Australian Government been in observing its undertakings to the League of Nations that, until the beginning of war in 1939, it had refrained from making any defence preparations whatever in the Mandated Territory. Shortly before that, however, returned soldiers took a vigorous lead in demanding that at least some effort should be made to arm and train those residents who wished to be better prepared to defend themselves and their homes. Colonel J. Walstab, the Chief of Police, was

one of the leaders of this movement and, largely because of his efforts, it was finally decided to form a militia-type battalion in New Guinea.

Army Headquarters issued the necessary authority on 4th September 1939 for the raising of what was to become known as the NGVR But the members were to be volunteers, who would be unpaid until they were mobilised, and warlike stores would not be issued to them direct as to an army unit but through the Administration police force. Nor was their strength to be more than about half the normal strength of a battalion although the original limit of 20 officers and 400 other ranks was raised to 23 and 482 by June 1940. These numbers were to provide for a headquarters, headquarters wing, machine-gun section and one rifle company (less two platoons) at Rabaul; a rifle and a machine-gun company at Wau; one rifle company each at Salamaua and Lae; machine-gun sections at Kokopo (near Rabaul), Kavieng and Madang.

The early days of the battalion were marked by vigour and enthusiasm with the old soldiers taking a leading part. Two regular instructors were sent from Australia and travelled from centre to centre introducing modern training methods. By mid-1941, however, the battalion had lost much of its zest. Many of the youngest and most ardent members had gone away to the war. Particularly on the goldfields, those who remained were finding the difficulties of getting from their scattered and often remote homes to the training centres increasingly irksome, and were disappointed at the seeming scarcity of stores and ammunition for training.

In September, Captain Edwards,16 who had been one of the most enthusiastic of the mainland volunteers since the creation of the battalion, was promoted to command the unit and set up his headquarters at Bulolo. He was already on full-time duty and so could concentrate on his unusual task which required him to be adjutant as well as commander. To help him Warrant-Officer Umphelby,17 one of the regular instructors, was promoted lieutenant and made quartermaster. Several of the men (notably Sergeant Emery18 and Rifleman Vernon19) were available full time. By December Edwards’ mainland strength was 170 to 180. Although immediately after Japan entered the war Morris was authorised to place the battalion on full-time duty only a comparatively small group was then called up and it was not until 21st January that the battalion was actually mobilised.

At the beginning of January the air force based on Port Moresby had only two squadrons of flying-boats, with a protective reconnaissance role. At the end of the month there were only 6 Hudsons, 4 Wirraways and 2 Catalinas there and General Wavell would not, either then or in mid-February, consent to divert American Kittyhawk fighters (P-40s) then

available in Australia and destined for ABDA Command. At this same time the naval organisation in Papua-New Guinea consisted of shore installations only. In the wider naval plan it seemed unlikely that a sufficiently powerful naval force could be concentrated off the east coast of Australia to prevent a Japanese move against Port Moresby.

Fortunately for the Australians there came a pause in events between late January and early March while the Japanese organised their next major moves forward. In New Guinea the obvious immediate objectives were the four most important European centres along the mainland coast—Wewak, Madang, Lae and Salamaua. In all of these the bombing of the three last-named on 21st January set off a series of extraordinary events.

Wewak was the administrative centre of the Sepik District (the largest of the New Guinea Administration districts) which stretched from the Dutch border eastward along more than one-third of the Mandated Territory coastline and south as far as the Papuan border. It took its name from the Sepik River which flowed through its centre from Dutch New Guinea to the sea between Madang and Wewak. Between the coast and the river the country was made forbidding by the rugged Bewani and Torricelli Mountains. South of the river lay the almost unknown heart of New Guinea, shut in by the Central and Muller Ranges running from east to west, heaving their broken heights to 13,000 feet and more, enclosing the Papua-New Guinea border between them. But it was the river itself which gave the district its distinctive character. In its course of some 700 miles it spread into seemingly limitless swamps, flowed deeply through a main channel a quarter of a mile or more wide in places, and bore with it masses of debris and floating islands of tangled grass and scrub. Crocodiles infested it, and hordes of mosquitoes bred there. The sago-eating people who lived along the river were of smouldering temperament and oppressed with witchcraft and superstitious fears. Traditionally they were head-hunters. In the big houses which were the ceremonial centres of each village, they hung by the hair long rows of heads, each head dried and smoked and with the features modelled in painted clay.

District Officer Jones20 was in charge of the Sepik District. He had been an original Anzac at 19 years of age, and had gone to New Guinea soon after his return from the 1914–18 War. He was a big man with a ruddy complexion and an unhurried manner. At the beginning of January he had worked out an escape route for the people of his district to follow if they were cut off by sea and air: by way of the Sepik, the Karawari (a tributary of the Sepik), overland to the Strickland River and on to Daru on the south coast of Papua. In determining this route he heeded the advice of J. H. Thurston, who had been one of the pioneers of the Morobe goldfields and later pioneered the fields near Wewak, and Assistant District Officer Taylor,21 who had already, on a great patrol, covered much of the country through which the proposed route passed.

After the news of the bombings of 21st January most of the 30 or 40 private European people in the district gathered in the camps which Jones was preparing and stocking on the Karawari and there awaited further instructions about evacuation. By mid-February, however, they were restless and began to leave the Karawari for Angoram, the Administration post on the Sepik, about 60 miles from the river mouth. Most believed the overland trip which Jones had planned for them to be impossible. About this time some hopes developed that it might be possible for them to be flown out to safety, but these were disappointed. On the 19th Jones ordered Rifleman Macgregor22 (of the NGVR Madang detachment), a pre-war Sepik recruiter and trader who had been using his two schooners on the river on evacuation tasks, to take the Administration launch Thetis and four schooners out to Madang. This Macgregor did, accompanied by four other Australians (to supplement the boats’ non-Australian crews). They reached Madang safely and, under orders from Sergeant Russell23 who was in charge of the NGVR there, worked bravely from that point, either crossing to New Britain to assist survivors from Rabaul or building up stores along the route to the Ramu and assisting parties into that area. Jones meanwhile had sent word to Angoram that he proposed remaining at Wewak with some of his staff and that the rest of the Administration staff would remain on duty in the district.

At this time the behaviour of the Assistant District Officer at Angoram began to disturb Jones and, on 10th March, he told Taylor to take over. The Angoram officer’s mind had, however, become unhinged. He refused to leave his station, and armed and entrenched about 40 of his native police; on the 20th he fought a pitched battle for more than two hours with Taylor and the party with him, shot Taylor and drove him and the rest of the Europeans away from the station.

Next day Jones arrived on the river. He then planned to attack the station with the help of seven other Europeans and seven natives. On the 23rd they closed in on the station. But the Assistant District Officer there had shot himself dead and his police had fled. Jones then left Assistant District Officer Bates24 in charge at Angoram and departed for Wewak on the 24th.

Scarcely had Jones gone than Bates had word that some of the rebel police had killed Patrol Officer R. Strudwick on his way down from the Karawari to Angoram. Later rebel police also killed three European miners, two Chinese and many natives, ravaged a wide area, fomented local uprisings at some points and caused serious disorders among the natives generally before they themselves were finally killed or apprehended.

Meanwhile practically all the other European residents of the district,

except the Administration staff, had set out finally to get clear of the approaching Japanese. On his arrival on the river Jones had sent about 12 of them off in the schooner Nereus with instructions to land at Bogadjim and make their way overland to safety from that point. After the fight at Angoram Thurston took a party as far as they could travel by water up the May River to start overland thence for Daru through the mysterious breadth of New Guinea. At the end of April, 8 Europeans and 82 natives, they struck into the mountains on foot.25

Jones and his men then busied themselves with the long task of bringing the renegade police to book and restoring order among the natives who had become disaffected—and with the general task of maintaining their administration.26

Meanwhile, in the adjoining Madang District, the civil administration was interrupted by the bombing of Madang on 21st January. Most of the civil population of the town then gathered at a pre-arranged assembly point about two miles to the south. Next day they set out on foot along an evacuation route which had been planned previously. Within a fortnight most of them arrived at Kainantu (in the Central Highlands due south of Madang). There they remained, comfortably situated, until the fit men of military age among them were ordered to report for military service and the others went on to Mount Hagen to be flown out to Australia.

When Madang was thus evacuated Sergeant Russell assumed control of the town, but he and his few men were in a most difficult situation after the civil authority over the natives disappeared and when several more bombing raids during the ensuing weeks intensified the confusion. When District Officer Penglase27 arrived to take charge of the district on 24th May he noted:

Natives [had] found themselves in circumstances to which they were not accustomed. Overnight, the Government, with its benevolent policy in which they had the greatest confidence and respect, no longer functioned. Roads, gardens and villages were neglected, and some natives, hitherto residing in villages near Madang, evacuated and moved to safer locations in the bush. Vast numbers were passing through the district from Morobe and other places of employment, whilst others were travelling

to the Markham, Finschhafen and Waria, spreading the most impossible rumours. Japanese bombs had struck fear into their very hearts and they were bewildered and apprehensive about the future. In addition the town had been looted, plantations were deserted and practically every unprotected home had been ransacked. In this connection it can be said that the natives were not only responsible. The District Office had been demolished, all records destroyed and the safe blown open and robbed of its entire contents of value. Missionaries, however, had remained at their respective stations and were exercising their influence in an endeavour to maintain control of the natives, and members of the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles also did good work in this respect. ... The only [Administration] officers remaining in the District on the 24th May were Lieutenant J. R. Black28 at Bogia, who had not received any instructions and decided to remain at his post, and Lieutenant R. H. Boyan who was actively engaged assisting in the evacuation of troops from New Britain.

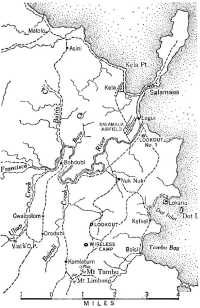

During this January-May period events in Lae and Salamaua moved more swiftly than elsewhere in the Mandated Territory. The Japanese needed Lae to build into a forward air base and they needed Salamaua to make Lae secure. The two towns were the air and sea points of entry into the forbidding country of the great goldfields area of New Guinea.

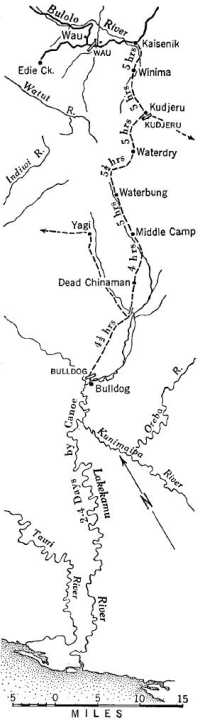

The inland town of Wau was the centre of that area. Primitive tracks converged on it from the mouth of the Lakekamu River on the southern coast of Papua and from Salamaua and Lae on the Northeast coast. But the country through which these tracks passed was an upheaved mass of twisted mountains, rising and sprawling seven and eight thousand feet above the level of the sea, the peaks cloud-covered, mists swirling away from the slopes and summits as the sun rose. Lonely winds blew among the trees which spread like a tumultuous ocean of green as far as the eye could reach. There was the noise of many waters falling or hurrying through deep ravines. The mountains were the homes of wild tribes.

On the southern coast the Lakekamu River mouth was 150 miles northwest of Port Moresby, 12 to 15 days’ journey by land, up to 24 hours’ by small lugger or schooner. Bulldog was 50 miles up river, slightly east of north from the mouth. Then over broken ridges and mountain crests and slopes, a difficult way wound generally still northward to Kudjeru, 35 miles as the crow flies, but up to a week of exhausting climbing and walking.29 From Kudjeru to Wau by way of Kaisenik was two days’ fairly comfortable walking. This was the only feasible overland route from Port Moresby to Wau. But the general area through which it passed from Bulldog to Kudjeru was the sinister “Baum country”, scarcely known,

and what knowledge there was of it had been gained from events which marked well its own savage nature and that of the people who lived there.

Hellmuth Baum was a German who refused to surrender when the Australians first seized New Guinea. He disappeared into the mountains where he wandered barefoot for years among the natives, learned their ways and languages and prospected for gold. He reported himself when the war ended and then continued his wanderings and prospecting. He was a gentle and just man. In 1931 Kukukuku natives, welcome in his camp at the head-waters of the Indiwi River (a tributary of the Lakekamu), treacherously killed him. One struck him a terrible blow on the head with a stone club. They cut off his head with one of his own axes and then disembowelled him and sang over the remains. Quite methodically they began clubbing his carriers to death. They killed seven of these but a number escaped. When the District Officer (Eric Feldt—who later directed the coastwatchers after the Japanese invasion began) received this news, he took a patrol towards the scene of the murders but the country largely defeated him. Penglase, then an Assistant District Officer, led a series of remarkable patrols into the area during the year October 1931–October 1932 to try to arrest the murderers and find practicable routes through the baffling country. His patrols were attacked by the natives and suffered hardships among the rugged and inhospitable mountains but, as a result of these trips, Kudjeru was established as a “jumping-off” point from the Wau side and the line of a primitive route between Kudjeru and Bulldog was established.

Wau–Salamaua–Lae area

To the Northeast of Wau was the Buisaval Track, which followed the surveyed route of a proposed road from Wau to Salamaua. First it led South-east along the Bulolo River to Kaisenik then swung Northeast to Ballam’s, climbing a steady grade which passed over dry and sun-drenched

kunai ridges. It was three to four hours’ walk from Wau to Ballam’s. From Ballam’s to the summit of the main range lying between the Bulolo Valley and the coast it was about three hours’ comfortable climbing, for the first hour over more dry kunai ridges but then through cool, damp mountain bush. From the summit the track dropped for three hours in a steady downhill grade to the Northeast, through bush and over many

sparkling streams to Skindewai. Thence it continued for three to four hours to House Bamboo, over rougher ways and precipitous mountain sides, falling down to the deep valley of the Buisaval River which the track paralleled. Then it climbed sharply to the Guadagasal Saddle, precipitously below which on the east, down the tangled and rushing mountain, the Buisaval raged into its junction with the Buyawim River and, equally close in the plunging depths on the other side, the Bitoi River swept into the so-called Mubo Gorge (a valley of narrow river flats between steep mountains). From the Guadagasal Saddle the track leaped down into the Mubo Gorge, and within 40 minutes, crossed the Bitoi by a swaying kunda30 bridge and junctioned with the track which ran from Wau to Mubo by way of the Black Cat Creek and the Bitoi River. The village of Mubo was less than half an hour’s walking along the bed of the Bitoi. From Mubo the track turned due north out of the depths of the Bitoi River system, over three to four hours of exhausting climbing, before it broke forth into the harsh kunai country, into sight of the sea far below, and into the village of Komiatum. There was then nearly two hours’ travel down and across hot and thirsty ridges before the track ran into the steaming, green, flat country at Nuk Nuk, and so quickly down the last reaches of the Francisco River, across it into the village of Logui and on to the narrow isthmus on which Salamaua lay.

The Black Cat Track left the Bulolo River just north of Wau, climbed to the head of the Black Cat Creek, then followed the Bitoi River to junction with the Buisaval Track near Mubo. It had been the original route from the coast into the goldfields of the Bulolo Valley but, by the time the war came, was rarely used. A little farther down again along the Bulolo was the beginning of another track, but this was even more undeveloped and more rarely used than the Black Cat Track. It struck north from Wau to the village of Missim then turned east to follow the Francisco River to its mouth less than two miles from Salamaua.

From Wau a motor road ran Northwest down the valley of the Bulolo River, after about twelve miles passing through the Bulolo Gold Dredging Company’s township of Bulolo, running on to Bulwa and thence to Sunshine. From that area two main tracks branched. The one turned Northeast over scorched and broken kunai ridges, becoming alternative tracks which followed either the valley of the Snake River or the high ground east of it and converged at Mapos. The Snake Valley provided easier going, the alternative route a good path but arduous travelling over timbered ranges, down and up steep gorges. From Mapos the track provided hard climbing over the Buang Mountains, then fell steeply to Lega and down the valley of the Buang River to the river’s mouth. Generally these tracks would mean five or six days’ strenuous walking from Wau. They had been favoured routes into the goldfields when gold first boomed at Edie Creek and along the Bulolo.

The second track led to Lae over some 80 miles. After crossing the

Snake it climbed steeply over grass ranges to Zenag, then dropped down the divide between the watersheds of the Snake and Wampit Rivers. It followed the course of the Wampit to its junction with the Markham, but threw off a branch at Wampit which struck east to the Markham through Gabensis. Down the broad Markham Valley from Nadzab a road some 26 miles long ran to Lae, through sun-drenched kunai grass and stony river flats.

On 21st January, just about noon, Patrol Officer Pursehouse31 reported from Finschhafen that some 60 Japanese aircraft were headed towards Lae and Salamaua. These divided and simultaneously struck hard at the two little towns, and at Bulolo, where five fighters, flying just above the ground up the valley, destroyed three Junkers, but, turning east again before they reached Wau, missed five aircraft on the field there.

The people at Lae got Pursehouse’s warning and took cover, but the attackers left destruction and confusion behind them. As they flew away two Australian Wirraways from Rabaul dropped down out of the clouds where they had remained concealed and landed on the airfield among the wreckage of seven civil aircraft which had been on the ground when the Japanese arrived. Half an hour after the raiders went, Major Jenyns,32 second-in-command of the NGVR who had arrived just before the raid, went to see the Administrator, Sir Walter McNicoll, who, with a small group of senior officials, had been working from Lae for some time in anticipation of the final transfer of the capital from Rabaul. The Administrator was sick and weak from a difficult and protracted illness. He agreed with Jenyns that a state of emergency existed and told him to “take over” with his soldiers. Most of the civilians then moved out of the Markham Valley.

At Salamaua (where Pursehouse’s report had not been received) the raiders took the town completely by surprise. They destroyed one RAAF and 10 or 12 civil aircraft on the ground. Despite the intensity and efficiency of the attack, however, there was only one Australian casualty. Kevin Parer (member of a well-known goldfields family and brother of Ray Parer who had been one of the England-Australia air pioneers) was in his loaded aeroplane, its engine running ready for take-off to Wau, when the Japanese struck. He was shot dead. Another pilot had just landed and, all unsuspecting, was taxiing to the hangar. Suddenly bullets were ripping through his plane and it was on fire. He dropped out of it and rolled into the kunai grass. After the raid all business in the town stopped and most of the European population (of whom there were probably 70 to 80 left at this time) “adjourned to the pub” to discuss the situation.33

Penglase, District Officer in charge of the Morobe District, whose headquarters were at Salamaua, had with him at this time R. Melrose, the Director of District Services and Native Affairs in the Administration. The Salamaua people heard nothing from Wau and Bulolo and feared that those centres had suffered heavily. They saw black smoke rise and hang over Lae but could not get in touch with the people there. They expected further attacks and, on the night of the 22nd, the civil population withdrew to a camp previously prepared in the bush outside the town. On the 23rd Melrose picked up enough news on a small wireless set to know that the Japanese were then at Rabaul.

There was general agreement that a Japanese landing at Salamaua was imminent and that all civilians should leave as soon as possible. But Penglase and Melrose were in a difficult position. Assuming, as they did, that all air traffic out of Wau had been immobilised, they decided that there were only two ways of escape: on foot, south to Port Moresby—and Penglase, one of the very few men who had experienced the rigours of that terrible country south of the Bulolo, felt that the old and the sick among them would never survive the journey; or by sea, down the coast, in the only two small craft and canoes available—a risky prospect in view of the known presence of large numbers of Japanese aircraft and the probable presence of hostile surface craft. Finally, however, they decided that Melrose, who was himself suffering from heart trouble, would take out by sea those who were obviously unfit for the overland trip (and the one woman among them, Sister Stock from the Salamaua hospital, who had been most steadfast) while Penglase led the rest towards the Lakekamu. The two parties set out on 24th January.

After their departure the only Europeans left in the town were six air force men, who were manning a signals station, and five or six of the NGVR with Sergeant Phillips34 directing them. Among the NGVR was Rifleman Forrester,35 who, with two or three others, had been on full-time duty in Salamaua since about mid-December preparing barbed wire and machine-gun posts.

In the days immediately after 21st January Phillips and his men were kept busy refuelling RAAF aircraft of which about four or six called most days. This was hard work as they had to do it from drums and natives were not always available to help them. The raid had frightened the natives, Administration control had disappeared, prisoners had been released from the gaol and some of them had secured arms, disorder was rife. Some little time after the civilians left, one of the RAAF pilots reported Japanese shipping which might have been moving towards Lae and Salamaua. When the NGVR relayed this to Port Moresby they were told to destroy all they could of Salamaua but not to leave until they were sure that occupation was imminent. That evening they threw petrol over the main offices, the stores and the hotel and burnt them.

Meanwhile, a scratch NGVR platoon under Lieutenant Owers,36 a surveyor with New Guinea Goldfields, had set out from Wau soon after the raid by way of Mubo, not knowing whether the Japanese had landed at Salamaua. As these men plodded towards the top of the range they passed groups of dispirited civilians making a slow way inland through the mountains and bleak bush which were foreign to most of them. With these were some NGVR men who, confused as to where command lay in the suddenly changed circumstances, had joined the civilian exodus. Corporal McAdam,37 a large, quiet forester with a battered nose who considered a man a weakling who could not do twenty miles a day in the mountains for days on end, pushed ahead of the rest of the platoon. From Salamaua he sent word of the situation back to Owers and some days later the platoon arrived at the isthmus to find the small group there in difficulties among disorderly natives.

Behind Owers’ platoon Umphelby set out over the Buisaval Track about mid-February with the rest of his company (which included a medium machine-gun platoon). Before leaving Wau they requisitioned anything they thought might be useful to them. In appearance they were a motley group, wearing a medley of their own clothing and army uniforms, their equipment mostly of the 1914–18 War leather type, emu feathers in their hats. They had no steel helmets, no entrenching tools, and, except for a few made at the Bulolo workshops, no identity discs. All carried packs and haversacks, their packs weighing between 40 and 50 pounds. None of them had ever carried such loads before in their walking through New Guinea; in pre-war days, it had not been considered possible (or seemly) for a white man to carry even the smallest load in the mountains. Even in war many of them considered that they could not operate without their “boys” and so, when they reported in for service, brought their “labour lines” with them. Umphelby’s company formed a “pool” of such natives and thus 70 “boys” or more moved with them in a long line. The company was typical of the NGVR. They had knowledge of the problems of New Guinea, the terrain and of natives. Like the Boers in South Africa nearly half a century before, they had come together from their isolated homes to fight, but each yielded only as much of his own individuality as he thought fit. There were many of enthusiasm and great courage among them, but they had had little training which would fit them to operate as a coherent unit; their average age was about 35; their supply services were sketchy, and to provide food was always a problem.

Umphelby made Mubo his headquarters. He mounted two Vickers guns on a ridge commanding the entrance to the valley from Salamaua. In the days which followed he kept one platoon at Salamaua, changing it from time to time, disposed the rest for the protection of his base, and kept them at hard training and reconnaissance patrolling. One task of the Salamaua platoon was to watch for the approach of the Japanese. They

manned Lookout No. 1, a camouflaged platform in a lofty tree on Scout Ridge (as it later came to be known), just south of the mouth of the Francisco River; this had been established immediately after the raid. Other tasks were to collect information and gather stores from the abandoned town—sugar, rice, tobacco and tinned goods—to send back to Komiatum and Mubo where supply dumps were being established.

At the beginning of March there came to the platoon at Salamaua a grim little band led by Captain A. G. Cameron. They were thirteen survivors from the 2/22nd Battalion which had been at Rabaul. Their leader was a ruthless and able soldier who, as a fugitive after the fall of Rabaul, had been in touch with General Morris’ headquarters at Port Moresby, giving news of the disaster and of the movements of his fellow fugitives. Morris had ordered him to come out of New Britain if he felt sure that he could not engage in guerrilla activities there, and Cameron had done so in a 21-foot boat with a two-stroke engine, bringing twelve men with him.

Meanwhile Edwards had increased his small local detachment at Lae to a company with Captain Lyon,38 who had recently returned from a school in Australia, in command. Lyon spread three platoons from Lae to Wampit building up stores dumps. On 7th March five aircraft raided Lae, which had been laid waste and was almost empty. Lyon then got word that a big convoy was headed in his direction. He himself stayed in the town with four men to await events while the rest of his men, making for Nadzab, prepared to destroy the one remaining petrol dump—at Jacobsen’s Plantation, about two miles from Lae in the Markham Valley, where 15 cars also awaited destruction. At 4.45 a.m. on the 8th Lyon was awakened to hear the noise of Japanese coming ashore. He had a lorry waiting. He and his men, accompanied by three natives, then turned their backs on the lost town, and went up the main road towards Nadzab.

That morning the Japanese landed also at Salamaua, where the bulk of the NGVR platoon fell back across the Francisco River leaving behind a few men, with whom were Cameron and several 2/22nd Battalion survivors, to demolish the aerodrome and fire the petrol dump. As Cameron and his runner, Lance-Corporal Brannelly,39 were falling back, Brannelly shot an enemy soldier at point-blank range—probably the only Japanese casualty from land action in the landings either at Lae or Salamaua. After the rear party had crossed the bridge over the Francisco, and when the Japanese appeared on its approaches from the Salamaua side, the NGVR men destroyed it. Most of them then took the track back to Mubo.

From late January to early March Wau had become an evacuation centre. After the January bombings most of the European and Asian civil population of the goldfields gathered there feeling that they had only a limited time to get out of the threatened area. They were joined by the

civilians from Lae who came in on foot under the leadership of E. Taylor40 (Assistant Director of District Services and Native Affairs in the Administration) and the overland party from Salamaua whom Penglase had diverted to Wau when he discovered, after pressing ahead of the rest, that that town was still intact. On his way out by air the Administrator had appointed the senior Assistant District Officer there (McMullen41) Deputy Administrator, and Assistant District Officer Niall42 was helping McMullen. They managed to get some of the displaced people out to Port Moresby by air with hardy pilots flying aircraft which, in some cases, they would not normally have been permitted to take into the air. Soon, however, it was evident that no more unescorted air traffic could be allowed in and out of New Guinea; the RAAF, hard pressed, could not supply fighters to assist and the air line closed.

After the arrival of the Lae party Taylor took charge of an improvised refugee camp which was set up at Edie Creek. He was a man highly respected and of great experience in New Guinea. As the senior Administration official on the spot he felt a deep responsibility for the people in his care and was determined to prevent them falling into the hands of the Japanese. And most of these people themselves were restless and were ready to face the hardships of travelling over unknown or little known country rather than accept capture. The advice of Penglase and three local surveyors (Ecclestone,43 Fox44 and G. E. Ballam) was therefore sought. They decided that Fox and Ballam should head a party to blaze the track to Bulldog and locate and build camps between Wau and Bulldog each capable of housing 40 people; that, three days in their rear, parties of carriers, each under an Administration official, should begin leaving Wau daily to build up food stocks at each camp. In the mean-time the authorities at Port Moresby had been asked to arrange to provide food at, and sea transport from, the mouth of the Lakekamu for 250 people from 25th February. Fox and Ballam led their party out on 9th February. There were three other Europeans, 70 native carriers and five native policemen. They carried out their task but the plan to maintain supplies along the route was not realised and the parties of evacuees leaving Wau subsequently carried their rations with them and supplemented them from a dump which had been built up at Kudjeni. Penglase and Ecclestone led one of these parties to Bulldog and then returned to Wau. Taylor took approximately 60 European and Chinese men out from Edie Creek on 7th March. In this fashion all the refugees reached Port Moresby safely.

March, however, brought other troubles to the goldfields. On the morning of the 1st, nine bombers struck at the centres there, and, heavily, at

Wau. When, a week later, news of the landings at Lae and Salamaua reached Major Edwards at NGVR Headquarters, he moved from the Bulolo to the Watut and reported to Port Moresby that he was preparing to destroy all the important installations from Wau to Baiune (the great Bulolo Gold Dredging “power house” area on the Baiune River). Because of his lack of suitable portable radio equipment the move cost him communication with both his forward positions and Morris’ headquarters and he remained out of touch until the 16th. The drone of many aircraft passing above him but hidden by rain and low clouds suggested the possibility of parachute attacks, of which very lively apprehensions were common throughout the whole valley at this time. On the morning of the 9th he gave orders for demolitions to begin. The two main power stations at Bulolo and Baiune and the main bridges at Wau and Bulolo were then put out of action. (Bombs had previously set off demolition charges which had been placed ready in the main Bulolo workshops.) Vehicles throughout the valley which might be useful to the invaders were immobilised.

During the next week Edwards had no news until the 16th. On that day a runner came to him with news from the coast (which he believed) that the invaders were preparing to move out from Lae up the Markham and that a platoon which had previously been sent from Lae to the mouth of the Buang River to cover that line of advance had been surprised by Japanese raiders. Thereupon he ordered his forward men to fall back. When, however, he realised that he had made a mistake he sent Umphelby and his company back to Mubo, established NGVR Headquarters firmly at Reidy Creek (four miles from Bulwa) with Jenyns in charge, and himself took command at the Lae end where his main centre was set up at Camp Diddy.

But the Japanese, it seemed, were in no hurry to push inland. Their first definite move in that direction came from Salamaua on 18th March, ten days after the landings. That day about 60 Japanese led by 4 natives, marched to Komiatum, destroyed the NGVR stores dump there, and returned to Salamaua. On the Lae side the invaders kept to the township area for several weeks, getting the aerodrome into order and establishing base workshops and dumps.

The Japanese pause gave the New Guinea men time to meet new problems. Their supply systems which depended on long carrier lines began to work better, communications, medical and other services were put on a sounder basis, a school of instruction was established at Wau, scouting parties began to slip up to and through the fringes of the Japanese positions, and vitally important observation posts, some of which had been prepared and were operating before the invasions, were manned.

In the Salamaua area Lookout No. 1 which had been abandoned after the Japanese arrival was reoccupied in April by the men of one of the newly-formed NGVR scout sections, under McAdam, now a sergeant.

When the first confusion which followed the arrival of the Japanese was dying down Edwards had told McAdam that information of what the

Salamaua observation posts

invaders were doing at Salamaua was vital. McAdam said he would get it if he were allowed to pick his own men. He chose Jim Cavanaugh,45 a forester like himself but younger in the service, fair haired and blue eyed; Geoff Archer,46 a welder with the Bulolo Gold Dredging Company and a wanderer by instinct; Bert Jentzsch,47 older than the others, a mine manager; Gordon Kinsey,48 Bob Day,49 and Jim Currie.50 These were all men who loved the bush and had an instinctive understanding of its ways.

McAdam began his move forward on 30th March. He made very quick time to Mubo and went on to get the latest information from Pilot Officer Leigh Vial,51 a promising young Assistant District Officer who had escaped from New Britain after the occupation of Rabaul, became one of the coastwatchers, and was installed by Umphelby’s men in a lofty lookout about eight miles in a bee-line South-west of Salamaua. (For some six months his quiet voice was to be heard regularly at Port Moresby reporting full details of Japanese aircraft landing at, taking off from and passing over Salamaua.) Leaving Vial, McAdam then began to edge his lookouts and his base camps closer and closer to the Japanese until within a short time his men were on the watch from the original Lookout No. 1 just below the mouth of the Francisco. Although scarcely a movement in Salamaua escaped them, for

some time they were hard put to make the best use of the information they gained because their communications system was primitive. In their early days their nearest wireless was at Mubo. Ingeniously and, having no maps, through the exercise of magnificent bush sense, notably on Cavanaugh’s part, they linked their various lookouts and camps with a telephone network contrived mostly with salvaged wire taken from abandoned camps, and burnt transformers from Wau, and sent their reports back to Mubo by runner. (Later the wireless was brought from Mubo to Wireless Camp—just forward of Komiatum—and information from the observation posts was telephoned to Wireless Camp and radioed back to Port Moresby in a few minutes.)

They were continuously watching, scouting tirelessly into the very fringes of the garrison area itself. They survived by adapting themselves completely to their new circumstances, with cool courage, intelligence, physical hardihood and superb bushcraft. McAdam said later:

We only used our own tracks and we took pains never to mark the main tracks so that, whenever we saw them, they were a book telling us what the Japs had been doing. ... Our tracks were so lightly marked that it took a good bushman to find them. We left no marks in that forward country. We walked carefully on roots, stones. We had the heels taken off our boots. Where necessary we walked our natives behind us to put their tracks over ours. ... We went there with three automatic revolvers only one of which we could rely on. We couldn’t carry our rifles because they caught in the bush so, in forward scouting in pairs, we took a pistol each, the good one and one uncertain one. Our sole defence was our speed. We could see a Jap before he could see us and if we had 10 yards’ start we could get away. What I wanted was a Tommy-gun so that our forward scouts could put the Japs flat and so get a 10 yards’ start on them. All the four months I was there we were unable to get a Tommy-gun. There were about six in NGVR but we didn’t have one.

The Japanese, however, knew they were there and after scouts (mainly Currie and Archer) had operated from the old Lookout No. 1 for about a month a Japanese patrol came searching for them. The searchers actually passed beneath the telephone line but did not see it. They condemned the local natives for assisting the Australians. Mainly to avoid further trouble for the natives McAdam withdrew his men from the old No. 1 soon afterwards.

At Lae less spectacular but more important work of a similar kind was going on—more important because Lae was the main Japanese base on the Huon Gulf and from it the main Japanese air strength operated. Before the Japanese occupation Sergeant Mitchell,52 an amateur wireless operator, had been installed on Sugarloaf, a conical hill overlooking the Huon Gulf, 9 miles south of Lae. On his set, which had been built up from civilian sources, he was in touch with both Wau and Port Moresby. He wirelessed to Port Moresby a full description of the landings on the 8th March. About noon that day, however, he saw a Japanese gunboat patrolling below him and, suspecting that it was using direction-finding apparatus to pinpoint his position, then closed his station.

After 8th March when Captain Lyon was established at Kirkland’s, on the south bank of the Markham, he sent a party to find a suitable site for an observation post on Markham Point, a high bluff on the opposite side of the Markham from Lae and about 8 miles from the town. It offered excellent observation of Lae and of the whole Huon Gulf area, marred only by the fog and cloud which closed Lae for days at a time.

Other watching posts were established along the Markham which, although of briefer life, provided more excitement for the men manning them.

Early in April the NGVR built and manned a post just Northeast of Heath’s Plantation which was about seven miles from Lae on the road to Nadzab. About the middle of the month they ventured as far as Jacobsen’s Plantation. Thence, from a near-by post, they could watch Japanese moving along the road and keep the aerodrome under observation. But as there was no signalling equipment at the observation post, and it took about nine hours for a runner to reach Camp Diddy by a back route through Yalu, the observations from Jacobsen’s lost much of their value.

Individuals of the NGVR, however, were thrusting even farther forward than this. Phillips (who had come across from Salamaua) and Corporal Clark, one of five New Guinea Volunteers of that name, actually entered Lae itself. While Phillips lay on a terrace on the western side of the strip, counted more than thirty aircraft arriving and watched where they were hidden, Clark circled the airfield and examined ammunition dumps. As proof of what he had done he brought back tags from some of the bombs which he had found. Acting on the reports of these two, Allied airmen were later able to destroy a number of the aircraft and several of the dumps.

While the men of the NGVR were thus settling to their lonely work General Morris, back in Port Moresby, could, at that time, do little to help them. Not only was he worried about the security of the Bulolo Valley and the threat of a Japanese approach to Moresby by the Bulldog Track but he was finding the maintenance of the NGVR most difficult. As soon as its existence was established he began to use the Bulldog Track for this purpose but his best efforts could keep only a trickle of supplies moving over it. Engineering improvements necessary to the track represented a Herculean task which he had not the men to attempt.

To increase the security of this troublesome but vital route, to form a base at Kudjeru for patrols and air observation, and to provide a link with the NGVR, he decided to send forward a group of reinforcements who had been bound for the 1st Independent Company and who now could not join their parent unit. Even before he had left Australia Lieutenant Howard,53 in charge of these men, had been instructed

You will ... take immediate steps to organise the reinforcements as one independent platoon of three sections with a view to its employment in 8 MD on tasks for

which the special training given to Independent Companies makes it particularly suitable.

He was ready, therefore, when Morris gave him his orders and the first of his men left by sea for the Lakekamu on 29th March.

By the time Howard himself arrived on the Markham about 25th April to get first-hand experience of what was happening, the Japanese were beginning to react in protest against the presence of the Australians both at Salamaua and at Lae.

From Salamaua a fighting patrol, about 65 strong, which had crossed from Lae on 23rd April accompanied by two Europeans dressed in white, set out along the track to Komiatum. One European seemed to be acting as a guide. But from their observation posts some of Umphelby’s men had seen them coming and three of them lay waiting in ambush at Komiatum. They reported later that they killed five of the Japanese and wounded others before they themselves, unharmed, left Komiatum. As on the occasion of the previous visit the strangers did not linger unduly and soon returned to Salamaua.

From the Markham the NGVR men reported on 24th April that a Japanese outpost had been established at Heath’s Plantation and, a little later, that a small gun had been sited there facing Northwest along the road.

While this interesting situation had been building up in the Lae–Salamaua–Bulolo area during the period January to April, the Japanese had been on the move elsewhere throughout the Mandate and along the island arc from Vila to the Admiralties.

The New Hebrides positions remained comparatively unmolested but at Tulagi Captain Goode54 of the 1st Independent Company who had moved forward from Vila, was watching the rapid approach of the Japanese. Goode stood by while the Resident Commissioner of the Solomons Protectorate evacuated the Northwest of his islands, retaining only a small staff in the South-east, and turned his civil administration into a military administration as the British Solomon Islands Protectorate Force. The AIF and RAAF detachments—some 50 all told—remained on Tanambogo Island in Tulagi Harbour. Soon after the fall of Rabaul the Japanese began desultorily to bomb Tulagi. The bombing grew more purposeful towards the end of April when, on the 25th, eight bombers carried out a determined raid.

On Bougainville and Buka coastwatchers and soldiers had been having a rather more difficult time. When Rabaul was occupied it seemed that invasion of Bougainville was imminent. Kieta, the administrative centre of the District, was at once abandoned but Lieutenant Mackie,55 who commanded the section of the Independent Company at Buka Passage, did not allow that to move him to hasty action. He was working closely

with Assistant District Officer Read56 and the two were preparing to continue to operate on Bougainville atter the arrival of the Japanese. Mackie moved to Bougainville and, on 24th January, a small rearguard and demolition party which he had left on the airfields at Buka engaged strafing Japanese aircraft (one of which they claimed to have shot down into the sea) and blew up the fuel supplies and bombs before they too left for the larger island.