Chapter 16: Buna Government Station Taken

WHILE Brigadier Wootten’s Australians, with American support from the I/128th Infantry, III/128th and the incomplete I/126th, had been fighting up the coast towards Buna from the South-east, the American infantry of Urbana Force were trying to break into the Buna area from the south.

Their failure to subdue the Triangle on 17th December had left them awkwardly placed. Their way led them Northeast towards Buna Government Station, where the main Japanese resistance was still centred, but both flanks of that route were commanded by strong pockets. The Triangle was on the right; on the extreme left the Japanese held Musita Island, framed by the yawning mouth of Entrance Creek, and were facing the island in strength from the eastern side of the creek. Obviously one or both of these threats had to be dissolved if the American advance on the Government Station was to know any security, and the rear had to be blocked against any Japanese attempts at relief from the strongly-held positions towards Sanananda.

To meet these circumstances, however, Colonel Tomlinson, the Urbana Force commander, would soon have fresh and comparatively well-found troops, for the movement of the incoming 127th was then well under way with the II/127th moving forward from Ango and the I/127th being flown across from Port Moresby. Tomlinson had the II/127th take over Smith’s

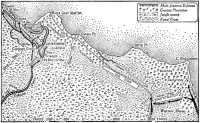

American operations before Buna to 17th December

positions, after the failure to take the Triangle, sent the II/128th back along the track for a rest, and brought Captain Boice’s II/126th back into the line, settling some of them into the Coconut Grove, clamping some about the Triangle and swinging two patrols from that battalion wide to his left rear, one under Lieutenant Schwartz to Tarakena and one under Lieutenant Alfred Kirchenbauer to Siwori village. He held as his reserve the first two companies of II/127th Battalion to reach the front.

As his first move in a new phase his plan now was to clear Musita Island on his left flank on the 18th. He proposed then to reduce the Triangle on the 19th thus giving his men a comfortable start through the Government Gardens to the coast South-east of the Government Station as an overture to an all-out attack on the station from that direction.

This plan went awry early, however. Unopposed, Captain Roy F. Wentland’s company of III/127th had crossed the difficult stream by noon on the 18th. Still unopposed they then began moving towards the bridge which connected the northern tip of the island with the station shore. But soon they met Japanese who killed Wentland and four others, wounded six more and drove back the remainder to the mainland in some disorder.

Licking that wound, Tomlinson turned against the Triangle on the 19th. At 6.50 a.m. 9 Marauder aircraft bombed the Government Station and in less than an hour 13 Bostons followed. While the second wave of planes was pounding the station, two of Boice’s companies (totalling 107) drove southward at the Triangle from the bridgehead leading down from the Coconut Grove. A heavy mortar barrage preceded them, and a third company (though mustering only 37) was stationed south of the road junction as a back-stop. But the day was a costly failure for the attackers and the end of it found forty of them killed or wounded for no gain, and the gallant Boice among the dead. Tomlinson, realising that he could expect no more from the 126th, pulled them back into reserve early next morning, except for the company at the tip of the Triangle. The 127th Infantry was to carry on.

Next day, shortly before 9 a.m., Captain James L. Alford’s company of II/127th crossed the creek from the Coconut Grove under cover of mortar smoke and behind an elaborate artillery and mortar program. But then, unseasoned as they were, they fell into confusion and, by 11.30, all attacking movement had fizzled out. A very gallant attempt to retrieve the situation followed in the early afternoon when Lieutenant Paul Whittaker, 2nd-Lieutenant Donald W. Feury and Staff-Sergeant John F. Rehak, led a desperate attempt by a reinforced platoon to come to grips with the well-protected Japanese, but enfilade fire caught them, killing the three brave young leaders and four of their men and wounding twenty. So another unhappy day ended, at a total cost to Alford’s company of 39 killed and wounded, and Tomlinson withdrew his men to the shelter of the Coconut Grove.

Thus, after three days fighting, no progress had been made towards clearing the way to the Government Station. The Japanese still held both the Triangle and Musita Island. Colonel Tomlinson, very tired and worn,

asked to be relieved and General Eichelberger told Colonel Grose, commander of the 127th Infantry, to take Urbana Force over. This Grose did at 5 p.m. on the 20th, just in time to initiate a new phase, for Eichelberger was now planning to by-pass the Triangle, having already broached that idea to General Herring. Herring had agreed that, if the attack on the 20th failed, the Americans might feel for a way through the Government Gardens without first reducing the Triangle.

Eichelberger now decided that his best line of attack was through the Northwest end of the Government Gardens—a line which would involve crossing Entrance Creek about midway between the Triangle and the island. The III/127th were to make the crossing—in canvas assault boats, each about 18 feet long and capable of carrying 10 men with their equipment. At 9.30 p.m. on the night of the 21st–22nd, therefore, the leading company put out into the dark stream in the wake of heavy mortar fire. By that time, however, their enemies were thoroughly alert and beat the black water with fire. The fire was so wild, however, that, by dawn of the 22nd, the company was firm on the opposite bank for the loss of only six men. In the early part of the day they covered the passage of a second company and by the early afternoon both companies were securely in position. They then selected a site for a bridge, about 200 yards upstream from their crossing place, and the engineers at once set to work there using the assault boats as pontoons. The bridge was finished on the 23rd and Eichelberger told Grose to send five companies forward from the bridgehead area on the 24th.

Meanwhile the island had not been forgotten. Strangely unmolested by the Japanese the engineers had been at work repairing a bridge which had previously linked the mainland with the western end of the southern side of the island. By the afternoon of the 22nd the work was done and a strong patrol from the III/127th Battalion crossed to the island without interference. Still unopposed, having traversed the island from west to east, it approached the second bridge, which linked the island with the Government Station area. Then it came under some fire and was strongly reinforced. Before midday on the 23rd, however, uneventfully enough, the Americans were in possession of the whole island and in a position to harass the Government Station with fire which included that from a 37-mm gun which they brought up. Eichelberger could now choose between trying to establish a bridgehead from the island or persisting with his plan to attack through the more southerly bridgehead which was already firm. Wisely, in view of the proximity of the main Government Station defences to the island, he continued with the latter course.

After a night of harassing and searching fire by both sides Grose sent the three rifle companies of the III/127th into the Government Gardens on the 24th with less than 1,000 yards to go to the sea along a line which ran a little north of east. But they were uneasily placed. Not more than 500 yards to their right the Triangle still smouldered corrosively against that flank. The ground ahead of them, though fairly flat, was covered with the tall, coarse kunai which rasped shoulder high in what had once

been cultivated ground, and concealed bunkers and strongpoints. As this enclave of unfriendly grass, about 500 yards wide, approached the sea it came against the edge of the Government plantation which followed the water-line Northwest to the point. The left of this “garden” sagged away into swamp which then, rather more than 100 yards northwards, yielded to the palm-covered higher and drier ground in which the Government Station itself was set.

Although only two companies, “I” on the right and “L” on the left, initiated this movement on a 450-yard front, behind a rolling barrage, almost at once Grose had to thicken the centre of the advance with a third company—“K”. This, however, added little impetus to a movement that was grinding sluggishly in the lowest gear with the right flank barely clear of its start-line and under viciously effective fire from hidden positions. This fire so distorted Company “I’s” strength and purpose, despite brave deeds by such individuals as Sergeant Elmer J. Burr, who threw himself on a Japanese grenade to smother its explosion with his own body, saving his company commander at the cost of his own life, that Grose pulled the company back at 9.50 a.m. and replaced it with Captain William H. Dames’ company of the II/127th. Then, at first, it seemed that the vigorous Dames might regain the impetus which the right had lost. Inspired and led by Sergeant Francis J. Vondracek, who had been acting as a platoon commander in Company “I” and had remained in the line, the newcomers clawed out the most forward of the troublesome positions. Although they then went on to get astride the track which ran Northeast through the gardens to the coast they were held there.

Disappointing though this day was on the right flank, and marked also by failure of the centre company to get ahead, the most bitter frustration was on the left. There Company “L” was strongly supported by the heavy weapons spread along the creek, mortars vigorously fought by Colonel M. C. McCreary and, after McCreary was wounded, by Colonel Horace A. Harding, Eichelberger’s artillery commander, and by fire from the island and adjacent positions to the north. One of its platoons broke right through to the sea. Led by 2nd-Lieutenants Fred W. Matz and Charles A. Middendorf the platoon reached the edge of the plantation by 9.35 a.m. There two strongpoints halted them. Sergeant Kenneth E. Gruennert refused, however, to be stopped. Single-handed, he grenaded the defenders of the first post to death. Though wounded, he then pitted himself against the second, blasted his enemies out so that they could be shot down by the rest of the platoon, and then fell dead to a near-by rifleman. The rest of the platoon went ahead again behind his high example and by midday had reached the sea. There, however, the Japanese closed them in, and fire from the supporting gunners (who had no means of knowing that they were there since the platoon’s communication had failed) fell among them. Middendorf was killed, Matz wounded. Finally Matz, with only eight men left, ordered most of the survivors out after an afternoon of bitter resistance and with darkness then about him. He

and one of his men, too badly hit to march, remained behind and hid themselves among the Japanese positions.

Meanwhile, Grose, ill-informed about the left flank situation, did not follow up this success until it was too late. The waning day then found him with Company “K” (his original centre company which he had relieved with Company “I”, from which Dames had taken over on the right) returning from a vain bid to assist Matz and Middendorf and the balance of his original left flank company, with Captain Byron B. Bradford’s company of II/127th now on their right, hardly 100 yards from their morning’s start-line.

Thus a well-planned, well-supported attack by adequate forces degenerated and was halted. General Eichelberger summed up:

I was awakened on Christmas morning by heavy Japanese bombing from the air, and my Christmas dinner was a cup of soup given me by a thoughtful doctor at a trailside hospital. For the projected American advance had not proceeded as expected. Troops of Urbana Force bogged down in the kunai grass of Government Gardens and their commander lost contact with his forward units. ... Next morning I wrote General MacArthur: “I think the low point of my life occurred yesterday.”1

Distressed and off balance, Grose asked for a pause in which to reorganise on Christmas Day. Eichelberger told him to press on with the attack and gave him, in addition to the other two battalions of the 127th, elements of the I Battalion which were just arriving at the front—part of Captain Horace N. Harger’s Company “A”, and Company “C” under Captain James W. Workman. Grose then planned his initial movement round Dames on the right (trying to force a way along the track), “K” in the centre, Harger and Bradford on the left where the main emphasis would lie, Workman as reserve.

On this Christmas morning the Americans used heavy fire from the island and its vicinity to mask their intentions. Japanese attention was thus concentrated on the area which linked the island bridge with the Government Station. At 11.35 a.m. Harger and Bradford then began an unheralded advance through the gardens. At first Harger made slow progress but Bradford, on his left, struck vigorously through to the edge of the plantation to a point a mere 300 yards from the sea and only about 600 below the Government Station. There the Japanese, recovering from their disconcertment, encircled the company though Harger fought in to the little garrison during the late afternoon. But these two groups now formed but a precarious enclave. Not only were they some hundreds of yards in advance of any other companies but they were completely out of communication. So night found the Americans’ left-flank thrust—their main one—hard against a foe who was now holding it as a man arrests the downward sweep of his attacker’s arm and holds him then in a state of straining equipoise from which either might emerge the victor.

Meanwhile, on the right, Dames had made only slight gains after a hard day. In an effort to help him yet another attack had been made

upon the Triangle—by Captain Workman, using one of his own platoons as the main component. But this, like those that had preceded it, was cast back, leaving Workman among the dead.

Grose was busy in the darkness reorganising his twisted line and marshalling assistance for Bradford and Harger. He ordered the main part of Company “C” to drive a corridor through from the left front to the beleaguered men. But this they failed to do on the 26th despite the strengthening of their front by the arrival of Company “B”. Colonel J. Sladen Bradley, Chief of Staff of the division and acting as Grose’s executive officer, and Major Edmund R. Schroeder, who had come forward the previous evening to take over the I/127th, then dashed through in the last of the light with the assistance of Lieutenant Robert P. McCampbell and one of the Company “C” platoons, briskly rebuffing sharp Japanese attempts to halt them. They found their comrades in a bad way.

The condition of the companies on our arrival was deplorable (wrote McCampbell later). The dead had not been buried. Wounded, bunched together, had been given only a modicum of care, and the troops were demoralised. Major Schroeder did a wonderful job of reorganising the position and helping the wounded. The dead were covered with earth ... the entire tactical position of the companies [was] reorganised and [they were] placed in a strong defensive position. ...2

On the morning of the 27th Bradley returned to the main American positions leaving Schroeder in vigorous command of the forward positions. Captain Millard G. Gray, Eichelberger’s aide-de-camp who had now taken over Company “C”, spent the day drilling into the Japanese swamp positions on the American extreme left, while Lieutenant John B. Lewis, leading Company “B”, skilfully took advantage of the Japanese absorption with Gray to edge closer and closer to Schroeder. By 5 p.m. he was through.

Apparently, however, this did not yet mean that the Americans were in any way firmly placed. Now the full story has been lost, but the impression is ineradicable: of a confusing array of infantry companies moiling in bewilderment amid the kunai grass; of unit and sub-unit commanders changing so rapidly that sometimes it is impossible now to determine who was locally in command at any given moment; of senior officers working as section, platoon and patrol commanders as the only means to drive their purpose through; of many very brave men fighting and dying to get results through their own individual courage which should have come through a cohesion of purpose and effort which was never present. An endless array of weary questions plods unanswered through the historian’s mind. Consider only the sortie through the gardens and into the plantation of Bradford’s and Harger’s men (and the similar circumstances surrounding the earlier break-through on this same American left flank by Matz and Middendorf, and the still earlier one by Sergeant Bottcher near Buna village). Where was the crisp command which should have quickly exploited and reinforced these successes; the loyalty and cohesion and quick

initiative which should have brought their fellows in the field hard in their wakes? If Bradley and Schroeder could get through what held back all the other companies in the small garden area? Why, having reached their summit with such fine touch, did Harger’s and Bradford’s men present such a sorry picture on the arrival of Schroeder and McCampbell? Why, with the position apparently so encouraging when night came on the 27th, did Eichelberger later write this?

I was to explore the depths of depression ... on the night of 27 December. ... At two a.m. a conference took place in my tent. We heard the reports, and they were grave all right. Our troops, if the reports were to be credited, were suffering from battle shock and had become incapable of advance. A number of my senior officers were convinced the situation was desperate. I think I said, as I had said before, “Let us not take counsel of our fears”. Nevertheless I was thoroughly alarmed.3

From all this, however, real achievement emerged on the 28th. That day Captain Dames, who had been slowly fighting forward up the track on the extreme right flank, and Gray, who had been whittling away at the left, closed in to the support of the beleaguered Schroeder. With the forward positions then strongly held the Americans were able to develop a corridor leading from their firm positions along the line of Entrance Creek to the plantation where Schroeder was now dominant. Before this reality the Japanese defenders of the Triangle unostentatiously drifted out of the positions they had defended so worthily for so long. The Americans, probing cautiously into the Triangle on the evening of the 28th, found a labyrinth of bunkers and strongpoints, littered with abandoned pieces of equipment and scattered ammunition, scored by shell bursts, with here and there fragments of human bodies.

Eichelberger, planning in anticipation of these heartening developments, had already decided to chop into the Government Station area from a new angle. To that end, early on the afternoon of the 28th, he had ordered Colonel Grose to get the III/127th Battalion marshalled on and in the vicinity of Musita Island. The plan was to force a crossing over the bridge which linked the northern tip of the island with the shore. To neutralise the fire of the strong Japanese positions which commanded the northern end of the bridge a fifteen-minute artillery and mortar barrage was arranged. Under cover of that barrage five assault boats would round the eastern side of the island, storm ashore at the northern end of the bridge and hold there while the main assault crossed the bridge itself, in the wake of a volunteer party whose task was to span with stout planks a 15-foot gap in the decking of the bridge.

But there was confusion in carrying out the plan. About 5.20 p.m. the protecting fire began to fall and the five boats put out into the stream, inadvertently leaving behind the officer-in-charge. Staff-Sergeant Milan J Miljativich, to whom the command then fell, bravely tried to drive the venture home, but his boats were still in mid-stream when the barrage lifted and were caught there by the uncowed defence. Miljativich’s was

sunk under him and the other four washed back to the American shore. Meanwhile the bridge party, slow to assemble, had met with no more success. Six volunteers had succeeded in laying their planks in position and a few attackers crossed behind them. Then, however, the ricketty framework refused any longer to support the improvised decking and most of the few who had crossed were marooned among the enemy who killed or wounded all of them. (A patrol took off the surviving wounded the following night.)

The Americans spent the next day searching for a way out of their difficulties. That way opened on the night 29th–30th when a patrol, crossing the shallows from the narrow finger-like spit which projected eastward from Buna village to the Government Station shore, found no Japanese to greet them—the silence made tinglingly alive for the Americans by memories of the hot reception which had met an attempt to cross this way on the 24th. Thus the approach for which the attackers were searching was open and they planned now to use it to the full—by throwing a force through the shallows, simultaneously forcing the passage of the bridge and crowding up from the south where Major Schroeder was now in strength.

Schroeder by this time had gathered round him most of his own I/127th Battalion and some elements of the rest of the regiment just above the junction of the coastal and Gardens’ tracks and, with Lewis’ company, had closed the gap between the right flank and the sea. The right of that sector was therefore firm and the left echeloned back on to Entrance Creek. In the Gardens south of the track other parties were at work clearing out the remaining opposition isolated among the kunai and on the fringes of the Triangle.

This was then the plan: at dawn on the 31st Schroeder would intensify the pressure he was already exerting on the Government Station from the South-east; after an attack through the shallows on their left two companies of II/127th—Captain Dames’, practised and assured after the determined part they had played in the Gardens’ fighting, and Captain Edmund C. Bloch’s—would cross the bridge from Musita Island and press towards the Government Station from the south; a third company of II/127th, under Lieutenant William W. Bragg, a young officer who had already shown his mettle, and Captain Jefferson R. Cronk’s company of II/128th (the 128th and 126th men having been brought back from their rest area a day or two before) would ford the shallows. Bragg and Cronk were instructed to secure a firm enough footing on the hostile shore southwest of the Government Station to draw to themselves the main enemy attention and cover the right, thus enabling Dames and Bloch to establish the bridgehead and then try themselves against the South-west defences of the Government Station coincidentally with the forward thrust of the other two prongs of the attack.

This whole movement depended upon the left flank. There Bragg led his company, Cronk’s following behind, into the ripples washing over the sandy bar, in the last of the darkness. Surprise was to be their most

effective weapon. But this was thrown away by irresponsible firing as Bragg’s company mounted the sandy spit, and suddenly a startled enemy seemed to have them bathed in light and blanketed in explosions. Bragg fell wounded.

Colonel Grose was waiting on the spit to hear news of the action from a man who was following the attackers with a telephone. The first information he received was that the lieutenant who had taken command when Bragg was wounded was running to the rear and others were doing the same.

I told the man (Colonel Grose said afterwards) to stop them and send them back. He replied that he couldn’t because they were already past him. Then the man said, ‘The whole company is following them’. So I placed myself on the trail over which I knew they would have to come, and, pistol in hand, I stopped the lieutenant and all those following him. I directed the lieutenant to return and he said he couldn’t. I then asked him if he knew what that meant and he said he did. The first sergeant was wounded, and I therefore let him proceed to the dressing station. I designated a sergeant nearby to take the men back and he did so. I then sent the lieutenant to the rear in arrest and under guard.4

Fortunately the other company had been more resolute. By the time the sergeant got the wounded Bragg’s men back to the scene of their panic, Cronk was fighting hard. He then took the whole group under his command and edged forward some little distance during the day. Nevertheless, the main object of the left-flank movement—to make possible the creation of the bridgehead—had not been achieved. And, from the south, Schroeder had little to report.

Despite this unhappy outcome it was clear that the Americans could not be kept out of the Government Station much longer. They had now only to keep pressing the beleaguered Japanese and the nut, tough though it was, must crack. Eichelberger, anxious to keep pace with the close of the Warren Force operations, ordered the full-scale clearing movement to begin on the first day of the New Year—to synchronise with the drive of the 2/12th Australian Battalion to clear the Simemi Creek–Giropa Point area. The Japanese, however, great defensive fighters as they had proved themselves at every point along the coast, still staved off the inevitable, grudgingly yielding only a little to the pressure from the south and holding Cronk fast on the spit. But with the evening there were unmistakeable signs that even their strong spirit was breaking: swimmers were seen striking out to sea from the Government Station area. And the morning of the 2nd saw the coastal waters from the Government Station to well past Buna village dotted with swimmers and desperate men clinging to anything that would float. Many sank, hit by fire from the shore. Enough remained within the Government Station defences, however, to make the 2nd a difficult day for the Americans. Captain Dames led the main movement off at 10.15 a.m., up the shoreline from the South-east and through the coconuts, with a second company—from the II/128th—hard behind. In the central sector Captain Gray’s company reached the point, the

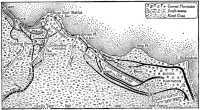

Lines of advance Warren and Urbana Forces, 18th December to 2nd January

men heaving themselves dripping out of swamps, where they had been working indefatigably for days, to clear the positions commanding the bridge and allow the long-sought passage from the island to open. From the spit Cronk was still straining inwards, but the advance was slow. It was not until 3.30 p.m. that Dames reached the tip of the bulge with which the coastline encircled the Government Station, to be joined there a few minutes later by Gray, whose task of clearing the approach over the bridge was finished. By that time other companies, too, were packing round. Less than an hour later the passage over the bridge had been made good and by 4.30 p.m. the Government Station—an area of broken houses, splintered trees and blasted earth, strewn with the twisted shapes of the dead—was at last in American hands.

While the fierce, flickering encounters which always marked the mopping up of dogged Japanese went on around the Government Station, the Americans sent a second company south along the coast to assist Lieutenant Lewis who had been trying unsuccessfully for some time to break through to link with the advancing Australians. By the early evening this link had been forged and the Buna operations were virtually finished.

To the actual front-line had been drawn the whole of the 32nd American Division, except for the small parts of the 126th Regiment on the Sanananda Track, as well as Australian forces consisting of an infantry brigade, a commando company, two squadrons of armour, a separate Bren carrier component, artillery and engineers. Also the operation necessitated a wide and constant use of Allied air power and the build-up of an elaborate system of air-sea supply. It cost the Allies some 2,870 battle casualties, some 913 of them Australian. Of those casualties the three infantry battalions of the 18th Australian Brigade accepted 863—approaching a third

of the American total for the employment of roughly one-third of the American strength for a third of the total time involved: a comparison which attests the vigour of this Australian brigade and the decisive nature of its entry into the struggle.

The Japanese are known to have lost a minimum of 1,390 men killed at Buna. These were counted dead: 900 east of Giropa Point, 490 west of that point including 190 buried at the Government Station itself. How many more, buried alive or dead in their strongpoints or uncounted for other reasons, must be added to that minimum it is impossible now to determine. Fifty prisoners were taken—on the Warren Force front 21 coolies and 1 soldier; by Urbana Force 28, mostly coolies, but with a few soldiers who were dragged naked and defenceless from the sea after they had swum hard for their freedom.

Captain Yasuda had deployed probably rather fewer than 1,000 men in the Buna Government Station–Triangle–Buna village area, with his main strength at the Government Station, his next strongest point at the Triangle, and less than 200 men allocated the task of defending the village itself. They fought bravely and exacted a cost far out of proportion to their numbers. When they saw that they had lost the fight, however, Yasuda and Colonel Yamamoto solemnly met by appointment and, together, ceremonially killed themselves.

Thus, soon after the beginning of January 1943, with the Japanese Buna positions destroyed, and the threat from Gona and westward dissolved, the whole of the Allied attention on the Papuan coast could be concentrated on Sanananda where a weary struggle was still going on.