Chapter 15: From the Markham to the Ramu

WHEN the fall of Lae was imminent General Blamey’s task was enlarged to include the seizure of areas suitable for airfields near Kaiapit in the Markham River Valley and Dumpu in the Ramu River Valley. This was in accordance with General MacArthur’s instruction of June 1943 in which the task of the 7th Australian Division was to be the prevention of enemy penetration south into the Markham Valley, and the protection of Allied airfields in the Bena Bena and Garoka areas.

On the day that Lae fell – 16th September – General Vasey flew to Port Moresby for a series of conferences with Australian Army commanders and American Air Force commanders. At the headquarters of the Fifth Air Force Brigadier-General Whitehead told Generals Herring and Vasey that fighters should be installed at Kaiapit by 1st November.

Although the movement of the 25th Brigade to Nadzab was incomplete by 61 aircraft-loads of troops and 205 loads of stores, and the 21st Brigade by 362 loads of troops and 178 of stores, Whitehead hoped that movement and maintenance of troops and stores would be kept to a minimum. All realised that every day saved in Army transport requirements meant a day earlier in establishing air bases in the Markham Valley for later operations. This could not be done, of course, until the aviation engineer battalions could be flown in. Once the Markham Valley Road from Lae to Nadzab was finished stores could be built up at Nadzab by the sea and land route; the Americans estimated that the road would take two months to build, however, and Vasey agreed, as his senior engineer had reached much the same conclusion two days previously. As the Finschhafen operation was to be launched as soon as possible Whitehead pointed out that he would be unable to give adequate air support to both the Kaiapit-Dumpu and Finschhafen operations at the same time.

General Herring said that he would reduce maintenance as much as possible and suggested that the Independent Companies in the 7th Division and Bena Force, aided by the Papuan Infantry Battalion, could take Kaiapit. Later in the day Generals Herring and Vasey conferred with General Blamey and the outline plan for operations up the Markham was decided upon. Herring was toying with a bold plan for capturing Dumpu first and then Kaiapit, but this did not commend itself to Blamey who feared the consequences if all air support had to be committed to the simultaneous Finschhafen operation. It was therefore decided that the 21st Brigade with the 2/6th Independent Company and supporting troops would be concentrated at Nadzab where maintenance would be reduced to a minimum. Vasey would send the 2/6th Independent Company and a company of the Papuan Battalion overland to capture Kaiapit as soon as possible. The 21st Brigade would follow, probably overland from Nadzab, except for the 2/27th Battalion which might be flown direct

to Kaiapit from Port Moresby. For the time being the 25th Brigade would remain round Nadzab. For the capture of Dumpu the 25th Brigade, airborne from Nadzab, and the 18th Brigade, airborne from Port Moresby, would probably be used, preceded by the American parachute regiment.

On 17th September the 7th Divislon was very dispersed. The 25th Brigade with the 2/2nd Pioneer Battalion was returning from Lae to Nadzab. Of the 21st Brigade, the 2/14th Battalion was on the way to Boana on the trail of the Japanese retreating from Lae, the 2/16th Battalion was in the Yalu area trying to cut the Japanese escape route, and the 2/27th with the 18th Brigade at Port Moresby. When it was clear that the 51st Division had escaped from Lae both Brigadier Dougherty’s battalions in the area were recalled because of the probable role of the 21st Brigade in the Markham Valley.

Despite the many documents found in Lae the Australian command still had an incomplete picture of the Japanese dispositions in New Guinea. It was known that General Adachi’s XVIII Army consisted of the 20th, 41st and 51st Divisions, but so far only the 51st with a few elements from the others (battalions from the 80th and 238th Regiments) had been encountered. It was assumed that the 51st Division, assisted by marines and a medley of other troops, had been responsible for the Salamaua–Lae–Finschhafen areas. Bena Force patrols had found evidence that part of the 20th Division was in the Ramu Valley and in the Finisterre Ranges. It seemed likely that the 20th’s headquarters was in the Bogadjim-Madang area and that the Rai Coast was also its responsibility. Little was known about the detailed dispositions of the 41st Division, thought to be in the Wewak-Hansa Bay area. Thus, an advance by the 7th Division from the Markham into the Ramu seemed likely to encounter heavy opposition.

For three days before the 17th the 2/6th Independent Company had moved to the marshalling yards in Port Moresby but flying was cancelled because of bad weather. “Getting a bit monotonous,” commented the company’s diarist. At 8 a.m. on the 17th, however, the company took off in thirteen Dakotas, and at 10.15 a.m. landed on an emergency landing ground west of the Leron River. This area had been chosen by the American airborne engineer, Lieutenant Frazier, who had landed there in his Cub a few days earlier. As the aircraft arrived the troops could see Captain Chalk’s company of the Papuan Battalion on the track towards Sangan. Two aircraft were damaged in the landing and were left on the strip. Captain King,1 the new commander of the 2/6th Independent Company, now in its second New Guinea campaign, sent patrols to the west and found that two of the Papuan platoons (one was with the 2/14th Battalion) had reached Sangan, where they came under King’s command.

At 4.30 p.m. an aircraft dropped a message to Chalk and just after 5 p.m. a message was also dropped to King. These contained General Vasey’s orders for the next day. “As far as is known,” King read, “the

enemy has very small forces in the Markham Valley. They are reported to be in Sangan and a small patrol is reputed at Kaiapit. It is possible that small parties escaping from Lae may move into Kaiapit from the hills to the north of the Markham Valley. Their morale is very low.” King’s task was to “occupy Kaiapit as quickly as possible and prepare a landing field 1,200 yards long, suitable for transport aircraft, as well as carry out limited patrols and destroy any enemy in the area”. In the message dropped to Chalk it was stated that the Papuan company would be “for use recce forward”.

The Markham and Ramu Valleys, in which the 7th Division was now to operate, were like a giant corridor some 115 miles long running from South-east to North-west and separating the Huon Peninsula from the rest of New Guinea. From end to end of the river corridor towering mountains rose on the north and south. The valley itself was flat and kunai-clad and most suitable for airfields. Apart from the main rivers – the Markham and Ramu – there were many tributaries which in rainy weather would impede progress, but movement up the Markham was relatively easy, except for the heat.

Vasey knew that the Japanese were pressing ahead with the Bogadjim Road. No. 4 Squadron RAAF kept a close watch on the road but Vasey needed also a report from the ground and this was immediately available because of a small but daring patrol from the 2/7th Independent Company to the road itself. On the last day of August, Lieutenant Dunshea, Corporal Wilson,2 and Constable Kalamsie (of the Papuan Constabulary) crossed the river and headed into the Finisterres. They returned to Maululi on 5th September. Next day Dunshea signalled a brief report to Colonel MacAdie of Bena Force, stating that the road was getting near the headwaters of the Mindjim River and that the survey trail was farther south. Parties of 50 coolies or unarmed soldiers each with an armed overseer were working on sections about 200 yards long and sometimes 100 yards apart. Several strong Japanese patrols were seen in the vicinity of the roadhead and on the 15-foot wide track running west from Kesa-wai, which was probably occupied by about 100 Japanese. In Dunshea’s opinion there was no practicable route to the roadhead for troops except through Kesawai. Along the north bank of the Ramu the Japanese had a screen of natives who would be difficult to avoid.

A patrol from the 2/7th Independent Company at Aiyura met a patrol from Tsili Tsili Force (57th/60th Battalion) at Arau on 6th September; thus met for the first time the two forces which had played such an important part in the events leading up to the assault on Lae and Nadzab. A few days later the linking process was carried a step further when patrols from Bundi and Maululi met at Kaireba on the south bank of the Ramu. During these early days of September the Onga observation post reported that the Japanese were still in Sagerak. The screen of natives reported by Dunshea was apparent on the 6th when a patrol from Maululi towards

the mouth of the Evapia River dispersed two armed bands in the bed of the Ramu.

On the afternoon of 14th September a patrol reported that natives had said that the Japanese were in Kaiapit and had cut the grass on the old Kaiapit airfield. About 35 were later seen moving east towards the Leron. Next day the Onga observation post reported that more Japanese had arrived; between 60 and 100 were camped in or near Kaiapit. On the 16th a small Japanese force from Kaiapit moved off towards Sangan. There now seemed to be between 150 and 200 enemy in the area.

On the 18th Captain King remained behind on the Leron to meet General Vasey while his company moved towards Sangan. At the meeting Vasey elaborated his instructions in his typical style: “Go to Kaiapit quickly, clean up the Japs and inform Div.” He added that the 21st Brigade would relieve the 2/6th Independent Company as soon as possible.

At Sangan King, Captain Chalk and Lieutenant Stuart (of the Papuan Battalion) found that the Japanese had been there recently and had dug foxholes and erected shelters, but had withdrawn when they heard of a Papuan patrol moving up. A report now came in from Lieutenant Talbot,3 who was commanding a detachment of the 57th/60th Battalion stationed at Intoap, that enemy headquarters (about 40 strong) was at Kaiapit with patrols to Sangan and Intoap. Other detachments were at Narawap um and Narantap with the line of communication through Sagerak and Marawasa. In order to find out whether or not the Japanese were in Kaiapit, Lieutenant Maxwell’s4 section left Sangan at 3.20 p.m.; after reaching Marangits the section moved into the foothills where they bivouacked late at night.

King gave his orders early on the morning of the 19th. “We will move from here to Kaiapit 0830 hrs destroying any opposition and occupy Kaiapit this afternoon.” One section of Papuans accompanied the Independent Company to make contact with the local natives and to begin work on the Kaiapit airstrip as soon as it was captured. At Sangan King left most of the Papuans, his engineer section and some signallers. These were to act as a message-relaying centre to division and to collect a carrier line for moving stores and ammunition from the Leron to Kaiapit on the 20th. Maxwell’s section was to meet the main body just outside Kaiapit on the afternoon of the 19th. The distance to be covered by King’s force of about 190 men was ten miles, and the route lay through open kunai country. The advance during the morning was rapid and gruelling and the oppressive heat of the kunai and stunted savanna country bore down on the men. They reached Ragitumkiap at 2.45 p.m. and here found that the 208 wireless set would not work back to Sangan. It was vital for Vasey to know what was happening so that he could arrange to send forward the 21st Brigade at the right time, but there was nothing that King could do about it at this stage. There was no

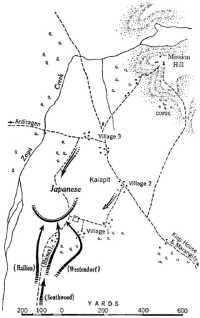

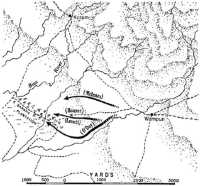

Kaiapit, 19th September

sign of Maxwell, but firing was heard in the foothills about a mile to the north and an enemy patrol seen there, and King presumed, correctly, that the Japanese were in contact with Maxwell’s patrol.

At 3.15 p.m. the company formed up in the flat kunai on the edge of a swamp about 1,200 yards from Kaiapit. King decided that, as it was essential to occupy Kaiapit on the 19th, he would have no time to send in reconnaissance patrols, which in any case would do away with surprise. Captain G. C. Blainey’s platoon therefore advanced on a wide front with Lieutenant Westendorf’s5 section on the right, Lieutenant HaIlion’s6 on the left and Lieutenant Southwood’s7 in reserve. Thirty-five minutes later the leading section was fired on from foxholes 1500 yards from the first Kaiapit village.8 The platoon went in hard and the first rush took the leading section into the village, which it cleared. Westendorf’s section swung out to the right flank at 4.5 p.m. and, with the help of the other two, cleared the main foxholes behind the first village with the use of bayonets and grenades. Westendorf was killed leading a charge but his men killed 11 Japanese where he fell. Against these fierce attacks the enemy broke and fled to the North-west abandoning Kaiapit and leaving 30 dead and several weapons. The Independent Company had 2 killed and 7 wounded, including King who had been forward with Blainey’s company. King carried on. During the

mopping up Corporal Graham,9 who had played a leading part in the attack, was wounded in the face but he too carried on.

At 5 p.m. the company dug in on the captured ground which included the Japanese huts. The wounded were brought in and Captain Row’s10 regimental aid post was established near company headquarters inside the area. The commander of one of the Papuan platoons left in Sangan – Lieutenant Stuart – then arrived to find out what had happened since the wireless had failed. King gave him a message for Vasey that Kaiapit had been occupied and that he needed ammunition speedily, if possible by air, and gave orders that the Papuan company was to move to a point a mile short of Kaiapit at dawn on the 20th with a No. 11 set and reserve ammunition. Stuart left at once for Sangan.

At 7.30 p.m. a native approached the perimeter waving a paper. This was secured from him and when he tried to run away he was shot. The document was later translated: “We believe there are friendly troops in Kaiapit; if so how many and what units?” This was signed with a code name. During the night several Japanese, thinking the area was still in friendly hands, walked up to the Japanese huts with their rifles still slung over their shoulders. Six were killed.

The Independent Company had apparently done its job and King prepared for mopping up as well as securing, and if possible completing, the airstrip on the morrow. The determination and spirit of Blainey’s men had forced the enemy from his foxholes. Had the advance been made with less dash the Japanese may well have stuck to their defensive positions and exacted heavy casualties as they had done so often before. Now, over half their garrison had been killed. It was puzzling that the native should have arrived with the paper, and that Japanese should walk into the Australian perimeter.

Meanwhile Maxwell’s patrol had reached the high ground overlooking Kiap House on the 19th and had quietly observed for three hours. As only natives could be seen the patrol decided to visit the house. At 3 p.m. they hastily withdrew in face of an advance from the North-west by what Maxwell reported to be “two platoons hostile native troops”. By some misunderstanding the patrol did not keep its rendezvous with the company and went straight back to Sangan. This was unfortunate as it had information that would have been valuable to King about the general layout of the airfield and three villages.

Before dawn on the 20th King gave his orders. He thought that there would now be only scattered resistance and ordered Lieutenant Watson’s11 platoon to leave the perimeter at 6.15 a.m. and move through the other two Kaiapit villages to the Mission and airstrip and back. A few minutes before it was due to move what appeared to be a powerful enemy force

20th September

attacked the section of the perimeter it held which covered the track entering Kaiapit from the west. The company’s report says that there was “a hell of a lot of firing and shouting, but very little offensive spirit shown”.

Captain King decided to counter-attack despite the fact that he had very little ammunition left. A quarter of an hour after the first enemy attack, Watson’s platoon charged and drove the enemy back about 200 yards to the No. 3 village where heavy fire forced them to ground. They lost several men including one of the section commanders, Lieutenant Scott,12 seriously wounded.

With Watson’s platoon held up, King sent Blainey’s platoon round on the right flank. The shortage of ammunition was becoming desperate and King saw that he might eventually have to withdraw for lack of it. The third platoon (Lieutenant G. A. Fielding), less one section, was therefore directed to form a firm base and cover the evacuation of the increasing number of wounded, who were later met a mile from Kaiapit by the Papuan company with a carrier line.

At 6.45 a.m. Blainey’s platoon attacked to the right through No. 2 village and pursued some enemy bands into the kunai to the east, using the 2-inch mortar on a small copse surrounded by wire near the foot of Mission Hill. It then fanned out, Lieutenant Southwood’s section making for Mission Hill and the other two moving on parallel lines towards some huts at the foot of this hill. Corporal Graham was now wounded twice more. In the intervening kunai several enemy were killed. By this time at least 100 Japanese had been killed and many of the others were showing signs of having had enough.

Soon after 7 a.m. a small carrying party of signallers and other men from headquarters carried forward to Watson’s platoon some ammunition

which they had been able to scrape together. It was a pitifully small amount but enough to encourage the platoon to rise to its feet and with fixed bayonets break out from the village. Lieutenant Balderstone13 set a fine example by leading his section across 70 yards of open ground and wiping out three machine-gun posts with grenades. The Japanese, superior in number but not in valour, turned and fled into the kunai and pit-pit with the Australians hot on their trail.

By 7.30 Southwood’s section had secured Mission Hill and remained there observing and directing the two platoons below it towards enemy bands and barracking as if at a football match. Lieutenant Hallion was killed when leading his section against an enemy machine-gun post. Corporal Wilson,14 who had carried in two wounded men under heavy fire during the fighting on the previous day, now took command of Hallion’s section. With bayonets and grenades the section captured the machine-gun and killed twelve Japanese where Hallion fell. This was the last organised resistance.

This decisive success had cost the enemy well over 100 lives and caused him a severe tactical defeat. The Japanese were thoroughly demoralised. Dumping their gear they tried to crawl away through the kunai. By 10 a.m. only the dead and dying were left. Small enemy parties occasionally raced through the kunai towards the Antiragen Track giving the men of the Independent Company flying shots. All were relieved when at 11.30 a carrier line arrived with ammunition. A quarter of an hour later Chalk’s Papuan company of two platoons arrived. One platoon was based in the Kaiapit villages and another included in the tenuous perimeter on Mission Hill. Soon arrived that ubiquitous and enterprising American, Lieutenant Frazier, who landed on the strip in a light aircraft at 12.30 p.m. According to him the strip must be ready for transports by 11 a.m. on the 21st.

At 9.30 a.m. on the 20th a small patrol had left for Sangan with a message for the 7th Division. However, when Chalk arrived with his Papuans and a No. 11 set, King after some difficulties was able to let General Vasey know what was happening. During the afternoon the dead were buried, and packs were collected from where they had been dumped at the previous day’s start-line. At 2 p.m. Japanese approached from the North-west but were driven away, three of them being killed and one Australian mortally wounded. Two hours later another Japanese patrol approached from the same direction. They were waved on by Sergeant McKittrick15 but after advancing a little distance became suspicious and disappeared, leaving one killed.

Even before King got through to divisional headquarters by wireless his rear link at Sangan had received the message by runner from King asking them to signal through to Nadzab the information that Kaiapit had

been taken and a request for ammunition, medical supplies and aircraft to evacuate the wounded. By wireless King added a request for reinforcement; his own effective force was now down to 139, but he was sure that the company’s aggressive action and wide-moving patrols had confused the enemy as to the Australian strength, and they had therefore hesitated to counter-attack. The situation was, however, by no means secure. Division replied to King’s request that they would try to bring in part of the 21st Brigade on the 21st if the strip was ready.

A splendid success had been won and the way was now open for a 50-mile aerial advance by the 7th Division. King’s men counted 214 corpses and estimated that about 50 more bodies were lying concealed in the kunai. Blood-stained abandoned packs and equipment indicated that there must have been many wounded. At least 10 officers and 30 NCOs were among the killed. Equipment captured included 19 light and heavy machine-guns, 150 rifles, 6 grenade throwers, 12 swords, four WT sets and a large amount of ammunition, picks and shovels. Most important was the large number of documents, notebooks and diaries taken from the enemy dead. The 2/6th Independent Company had lost 14 killed or died of wounds and 23 wounded.

On the morning of the 20th, not yet knowing what had really happened at Kaiapit, Vasey had Dougherty and the 2/16th Battalion standing by at Nadzab for rapid movement west. At Moresby that day General Chamberlin rang General Berryman and asked what the Australians were doing about Kaiapit. Berryman replied that Vasey was in command on the spot and that General Blamey was content to leave it to him. Berryman that day noted down the subsequent conversation: “He said General MacArthur would not be satisfied with that. I told him General MacArthur should ring up my chief. Chamberlin said MacArthur was hot foot after him.” When the Americans learnt what had happened their praise and their generosity knew no bounds. The Independent Company received General Kenney’s thanks and an offer to fly in a plane-load of whatever the company wanted, and in due course a consignment mainly of soft drinks, sweets, cigarettes and reading matter arrived.

During the night at Kaiapit the Papuans killed five wandering Japanese. Spasmodic firing all night prevented any sleep for the tired and strained men of the Independent Company. From early in the morning of the 21st Australians, Papuans and natives worked hard to prepare the strip while patrols moved two miles north and west, killing one Japanese and capturing another. At 9 a.m., soon after an enemy patrol had been driven off to the north, Captain King received a message from the 7th Division that they would try to land part of 21st Brigade at Kaiapit that day.

At 10 a.m. on the 21st Brigadier Dougherty learnt that his Kaiapit command would consist initially of the 2/16th Battalion, the troops already in Kaiapit, medical, supply and engineer detachments, Major Duchatel of Angau, an interpreter from the American Army, and 600 natives. Vasey told him that his role would be to “secure” Kaiapit and

occupy the Markham Valley as far as Arifagan Creek to cover the construction of landing fields west of Marawasa.

Tropical warfare was no new experience for Dougherty. He was an enthusiastic and unassuming soldier who had been a schoolmaster before the war. He had commanded the 2/4th Battalion in battle in Libya, Greece and Crete; and, then aged 35, the 21st Brigade in operations in Papua from November 1942 onwards.

Colonel Hutchison of the Second Air Task Force was with Vasey when Dougherty was there. No one yet knew whether the Kaiapit strip would be ready on the 21st; Hutchison said that a length of 4,000 feet would be needed as the aircraft had to land up wind and the hill made approach difficult.16

At 3.30 p.m. Hutchison, a splendid airman who had done this sort of thing before, made a test landing on the new airfield with a transport plane. He picked up King’s wounded and returned to Nadzab with them. An hour later he returned to Kaiapit with a load of rations and ammunition. Dougherty and some of his headquarters went in the transport, which landed on the Kaiapit strip soon after Vasey had landed in a Piper Cub; Vasey ordered the wounded King back to Nadzab for treatment. By 6 p.m. six transports had arrived at Kaiapit ferrying up one company of the 2/16th Battalion. The 22nd was a good day for flying and the remainder of the 2/16th Battalion and brigade headquarters as well as a party of American engineers arrived at Kaiapit. During the morning Warrant-Officer Ryan of Angau questioned a Marawasa native about the route to Marawasa. The native said that there had been a landing strip just west of Sagerak as well as the one marked on the map at Atsunas; in pre-war days this strip could take Junkers transport aircraft. Dougherty decided that Sagerak and the country just beyond it would be a good early objective, for, if the brigade met opposition in the narrow part of the valley near Wankon it would have a landing ground on the other side of the Maniang and Umi Rivers, which themselves could be serious obstacles.

At 3 p.m. on the afternoon of the 22nd therefore Lieut-Colonel Sublet’s 2/16th Battalion moved west towards the Maniang, intending to cross it that day and move on to the Umi next day. By dusk the battalion was across the many channels of the Maniang which spread over a breadth of about 2,000 yards.

Twenty minutes after the departure of the 2/16th Vasey’s senior staff officer, Lieut-Colonel Robertson, flew to Kaiapit and told Dougherty that documents captured at Kaiapit showed that the Japanese force destroyed by the 2/6th Independent Company was not an isolated standing patrol but the vanguard of a Japanese force consisting of some 3,500 troops comprising the 78th Regiment of the 20th Division and a battalion of the 26th Field Artillery Regiment with twelve 75-mm guns.

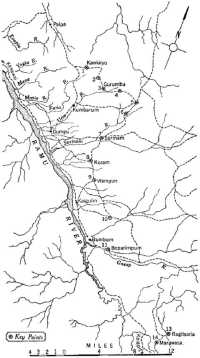

Key points and route as set out in Nakai Force operation order

The Japanese order had been signed by the commander of the infantry of the 20th Division, Major-General Masutaro Nakai, on 8th September: “The force will coordinate movements with 51st Division and advance to Kaiapit area in order to attack enemy coming north from Wau area.” The advance-guard consisting of the III/78th Battalion under Major Yonekura would leave Saipa on 12th September, secure Kaiapit and prepare for an attack on Nadzab. Next day an engineer company would leave Saipa with the task of reopening the supply route to Kaiapit. Next would come a “key points capturing party”, consisting of most of the other two infantry battalions and the I/26th Artillery Battalion under the artillery commander Lieut-Colonel Kagayama. This party would be ready to move at any time and would be followed on 17th September by the main body led by the 78th Regimental Commander, Colonel Matsujiro Matsumoto. Nakai himself would be with his force headquarters at Yokopi by 11th September after which he would establish his battle headquarters at Marawasa by 25th September. A protection force on the right flank of the advance would be supplied by the provosts whose task would be also to “conciliate natives and with their cooperation make them work in the supply lines”, to occupy Usini and to reconnoitre “enemy situation” in the Bundi area. The provosts would thus help the three infantry companies who were already on outposts directed against Bena Force. Ten days’ rations would be carried by the advance-guard but all troops would be on half rations and would “dress lightly as possible”. Supplies for Nakai’s force would depend on the work of the Automobile Company which would carry them forward from the coast to Yokopi; the Independent Pack Transport Company which would carry them forward from Yokopi to Kankiryo; and the natives recruited by the provosts who would carry on from there. The route for the advance would be from Paipa through Gurumbu, Surinam, Wampun, Boparimpum, Ragitsaria, Mara-wasa to Kaiapit; in other words along the line of the key points.

The establishment of the “key points” delayed the enemy and dissipated his strength so that Nakai lost the race for Kaiapit when his advance-guard of two

infantry companies, a platoon of machine-guns, a platoon of engineers and a section of engineers arrived at Kaiapit on 20th September.

Before the assault on Lae General Adachi had intended to attack and capture the Bena Bena plateau with a force of about 6,000 men. He was also apprehensive about his strength in Finschhafen which he expected might be the scene of large-scale Allied landings and decided to reinforce it. In the Lae–Salamaua area before 4th September was a total of about 11,000 men. In the Finisterres was the 20th Division less the 80th Regiment and plus other troops. The task of this force of 20,000 men was to supervise the building of the Bogadjim Road and to advance down the Markham Valley. Most of the 80th Regiment on 4th September was at about Saidor on its way along the Rai Coast to reinforce Finschhafen where there were about 4,000 men from shipping units, base troops and transit troops. Madang contained about 10,000 base troops including air force ground staff. Wewak was the biggest base and contained the headquarters of the 41st Division less the 238th Regiment – a total of 12,000 men – and about 20,000 men from shipping and air force units.

The loss of Lae caused Adachi to change his plans rapidly. He gave up the idea of an offensive to the Bena Bena plateau and instead decided to concentrate on the defence of Finschhafen. On 5th September he ordered the fresh 20th Division less the 78th Regiment to move to Finschhafen from its positions on the Rai Coast and in the Finisterres between Bogadjim and Kankiryo.

Nakai’s role was thus a vital one. The Australian capture of Nadzab made it impossible for the 51st Division to join the 78th Regiment in the Markham Valley as originally intended, but a bold thrust down the Markham by Nakai would make the withdrawal of the 51st Division easier and might possibly upset the Australian plans for an offensive up the Markham. Thus the Japanese anticipated attacks on both the Kaiapit area and Finschhafen. They were surprised, however, at the speed with which the Australian vanguard reached Kaiapit. The leisurely Nakai was outwitted by the quick-thinking and aggressive Vasey. Vasey in his turn was enabled to carry out his plan by the enterprise and efficiency of the American 54th Troop Carrier Wing. The prize of Kaiapit was in Australian hands. Nakai thought that he had half completed his object by “drawing” the Australian force from the trail of the 51st Division. It would be much easier to resist the Australians in the rugged Finisterres, and Adachi had left it to Nakai to decide how far to go forward down the Markham.

The information given by Robertson did not greatly change Dougherty’s ideas about the 21st Brigade’s advance. The Australian commanders did not yet know that two regiments of the 20th Division were on their way to Finschhafen, but thought that they must be prepared to meet the whole strength of the 20th Division beyond Kaiapit. They knew, however, that the enemy’s striking power would be limited by shortage of supplies even when the Bogadjim Road was in use. Robertson had also told Dougherty that Vasey hoped to secure Dumpu in the Ramu Valley by 4th October so that supplies and service detachments could be flown in before the period 10th–20th October when there would be no fighter cover for transports. Thus Dougherty was keen to push ahead when his other two battalions arrived. The 2/14th Battalion on the 22nd moved to Nadzab

ready to fly on to Kaiapit, and Vasey asked that the forward move of the 2/27th Battalion from Port Moresby should be speeded up.

Writing to Herring on the 22nd Vasey had some interesting comments to make:–

The situation at Kaiapit is now, I am sure, well in hand as, by this evening, we will have the whole of the 2/16th and perhaps some of the 2/14th there also. There is, however, one object lesson in the action. It is that, in view of the opposition that appears to be likely to be met in the valley, it is quite wrong to send out a small unit like 2/6th Australian Indep Coy so far that they cannot be supported. May future plans take full account of this lesson.

Whatever the value of the lesson, a bold risk had been taken and a triumph won. It was fortunate that, before the Kaiapit action, no one knew of the advance of the 78th Regiment. Had this fact been known an Independent Company and two platoons of Papuans would undoubtedly not have been sent to seize Kaiapit. There were no other troops available at the time so that Kaiapit would have been in Nakai’s hands and the 7th Division would have been faced with a formidable and tiring advance up the Markham Valley. It is not often that it is well not to know the enemy’s intentions, but Kaiapit was an example.

Vasey also gave Herring his views about the future:–

Yesterday I had all the talent of the Air Corps and the US Engineers here. ... The Air Corps seems to have trouble in determining whether they will establish their next permanent station at Kaiapit or Marawasa. Whitehead is very keen on Kaiapit, but some engineers say it is not suitable terrain.17 However, as far as I am concerned I don’t really mind where they go, for I am proceeding North-west along the valley by the bounds Kaiapit–Marawasa–Dumpu. The task of securing the Marawasa area has been given to 21 Bde.

Vasey was already planning his move beyond Dumpu. “I presume that, on arrival at Dumpu,” he wrote to Herring, “my task will be to secure Bogadjim. This will involve construction of 14 miles of road to join up with the one the Japanese have built for us.” Vasey would have been disappointed had he known that General Blamey’s intention was that the 7th Division’s task would be to carry out a holding operation in the hills north of Dumpu.

While Dougherty was gathering his forces at Kaiapit Angau representatives, Warrant-Officers Ashton18 and Seale,19 were recruiting as many local carriers as possible. Although many of these had been working for the Japanese they were ready to return to their old masters. There was some evidence that the Japanese had trained native troops in a school at Sagerak, and at this time Australian patrols from Bena Force into the Ramu Valley

encountered more armed natives than Japanese. Even these Japanese-trained natives were not averse, however, to changing sides, particularly because of the contrast between Australian and Japanese treatment. In one of the huts at Kaiapit were three dead natives who had had their hands and feet tied and had been bayoneted by the Japanese. Such treatment did not endear the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere to the natives.

In the Ramu Valley many of the natives were hostile to any intruders and in the Markham German Lutheran Missions, at such places as Kaiapit, were thought before the war not to have insisted on loyalty to the Australian administration among their converts. One of the senior Australian commanders in the area thought that the mission “had done much to sow the seeds of anti-British feeling”.

Half an hour after midnight on the 22nd–23rd September Dougherty received orders from the division for “no further movement in strength until commander visits you earliest 23 Sep”. At 2 a.m. on the 23rd a message was therefore sent to Sublet ordering him not to move to the

Umi until he had enough carriers, but to send out a platoon to reconnoitre the crossing. Dougherty did not believe that a battalion move to the Umi would constitute a forward movement “in strength”. Later in the morning Vasey flew from Nadzab to Kaiapit to confer with Dougherty about plans to meet the Japanese presumably advancing down the river valleys.20

Swift and lightly equipped a patrol from the 2/16th, led by Lieutenant Wallder,21 moved out before dawn that day towards the Umi crossing. Other patrols scoured the area from Antiragen, where the battalion was now based, and found signs to the north and west that the enemy had left the area after his defeat a few days previously at Kaiapit. One enterprising patrol along the Yafats River found no enemy but managed to return with sweet potatoes, bananas and corn. The belief that the enemy had left the area was confirmed by No. 4 Squadron which reported early in the morning that there seemed to be no enemy along the Yati River to Marawasa.

Late in the morning Wallder’s patrol reached the Umi where three Japanese, seen across the river, disappeared rapidly into the hills after being fired at. Lieutenant McCullough’s22 platoon was then sent forward to support Wallder’s crossing of the river. Sublet’s intention on this day was that one company should establish a bridgehead at the Umi crossing and cover the crossing by the remainder of the battalion as soon as they were ready. Wallder and McCullough crossed the river and followed the tracks north towards Sagerak.

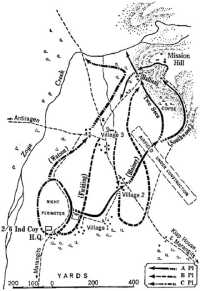

Lieut-Colonel Bishop’s23 2/27th Battalion left Port Moresby in 45 transports and flew direct to Kaiapit on the 23rd. By 10.50 a.m. the last plane had landed and the battalion began to climb the hill behind Kaiapit Mission to take over from the 2/6th Independent Company. Although the stout-hearted Independent Company needed a few days to recover from the Kaiapit fight, Dougherty was reluctantly compelled to give it a further task, mainly because his third battalion had not yet arrived. Early on the 23rd Lieutenant Fielding’s platoon of the 2/6th was instructed to protect the right flank of the 2/16th Battalion by patrolling from Antiragen north towards Narawapum.

Thus, on the evening of the 23rd, with the threat of the Japanese advance down the river valleys apparently looming, the 21st Brigade was spread out between Sagerak and Kaiapit. But Dougherty was confident that, once his 2/14th Battalion arrived, he could hold Kaiapit and

(as he said in his report) “crack the Jap if he attacked, and at the same time secure the Umi crossing, and, with vigorous patrolling, hit the Jap hard in the Sagerak area”. He told Sublet to secure the high ground south of Sagerak on the 24th “leaving something to hold the crossing place with the view of later driving the enemy from Sagerak and preparing an airstrip in its vicinity”.

The 24th was a busy day for the 2/16th Battalion and the 2/6th Independent Company. As they probed forward towards Sagerak Wallder’s men were fired on by machine-guns and rifles. The patrol’s 2-inch mortar fire, however, caused this enemy rearguard to withdraw. Meanwhile patrols from Fielding’s platoon of the 2/6th were moving towards Narawapum and the 2/16th Battalion was advancing from the Yafats River towards the Umi. The Papuan company was patrolling the northern foothills trying to trace a possible route into the Australian area for the Japanese from the Boana–Wantoat areas.

Half an hour after midday two companies of the 2/16th were across the swollen Umi and moving forward to join the two platoons already on the high ground south of Sagerak. The Pioneer platoon manned the rope ferrying the stores across and rescued the washaways. The ease with which the natives “bounced” their way across the fast-flowing river was a source of wonder and envy to the heavily-burdened troops battling their way inch by inch along the rope.

During the afternoon there were two brushes with enemy patrols. In the Narawapum area a patrol from the 2/16th Battalion joined Lieutenant Maxwell’s section of the 2/6th Independent Company and clashed with about 20 Japanese carrying full packs and equipment including at least three machine-guns. The enemy rapidly withdrew. Across the Umi Lieutenant W. J. Duncan’s platoon of the 2/16th became the vanguard, and by 2.40 was overlooking Sagerak and getting ready to move towards it. At 5 p.m. the Australians skirmished with an enemy patrol and Duncan was wounded by a sniper. It was not until well after dark that the West Australians finished their arduous crossing of the swollen river.

During the day Dougherty visited the Umi crossing place. The main channel was about 50 yards wide and 4 feet 6 inches deep in its deepest part and fast flowing. He was convinced that at flood-time the river would spread to a width of up to 200 yards and would then be impossible to cross with existing equipment. After anxiously watching the crossing for two hours Dougherty returned to his headquarters at Kaiapit to find out what troops and supplies had arrived. No aircraft had arrived during the day so there was no 2/14th Battalion, and the only reserves of food and ammunition were those actually carried by the 2/16th and 2/27th. Native reports were arriving that the Japanese were holding the villages along the foothills and in the upper Umi area, and the Boomerangs reported that there were suspected Japanese positions on the upper Umi which might be held in strength. Dougherty began to consider concentrating his brigade in a more favourable position, and was not altogether sorry when, towards dusk, he received a signal from divisional headquarters

that, as the enemy in the area was double the brigade’s strength, Vasey was most concerned about a part of the brigade being separated from the rest by the Umi. Dougherty therefore decided to order the 2/16th back across the Umi at first light on the 25th, leaving a standing patrol south of Sagerak. This message reached the battalion at 8.30 p.m., half an hour after the dangerous crossing had finally been completed. “The order to withdraw was received without enthusiasm,” wrote the battalion’s historian. “The idea of falling back was repugnant and the prospect of crossing back over the Umi River was a dismal one; but orders had to be obeyed.”24 Sublet reluctantly withdrew his battalion across the Umi before dawn on the 25th, leaving a platoon (Lieutenant Crombie25) in the area overlooking Sagerak. Re-crossing the Umi in the dark presented special difficulties but was finished by 8 a.m. and the battalion moved back to an area between the Maniang and Yafats Rivers.

It was ironical that, after all the effort entailed in crossing and recrossing the Umi River, Crombie’s platoon should find Sagerak deserted that day. A party of about sixteen Japanese fled hurriedly on his approach, leaving documents, diaries, medical stores and other equipment. In fact the Japanese seemed to have departed so speedily that they were carrying only their rifles. Lieutenant Frazier walked North-west from Sagerak and pegged out a landing strip which required only four hours’ labour to fit it for the landing of transport planes.

That morning (the 25th) Dougherty was about to climb into a Dauntless dive bomber for a reconnaissance flight to the Ramu when Vasey landed in his Cub. Vasey told Dougherty to go ahead and look at the country about the Umi; he said that if the Japanese decided to attack then the area between the Umi and Kaiapit was a good place to destroy them. Dougherty flew up the Markham and down the Ramu to beyond Dumpu looking particularly at the country through which the Japanese track was thought to go from the Gusap River to the upper Faria River. Carefully examining the country east of the Umi, he agreed that if the Japanese ventured on to the low country it would be to the Australians’ advantage and a winning fight could be fought there. On Dougherty’s return Vasey said that he thought that the enemy would attack Kaiapit because it was their custom blindly to persevere with a plan once formed. Dougherty, however, did not think that the Japanese would do this as they would have difficulty in maintaining a sufficient force so far forward. Vasey finally decided to bring the 25th Brigade to Kaiapit before he made any forward move; originally his idea had been to fly the 25th Brigade in farther forward after the 21st Brigade had secured a landing ground to the west. Thus Dougherty’s activities were restricted to reconnoitring crossings over the Maniang River and patrolling. The 21st Brigade would create the impression of minimum strength in the hope that this would encourage the Japanese to attack.

Back in Nadzab Brigadier Eather received instructions that the 25th Brigade was to be flown to Kaiapit, starting with the 2/31st Battalion next day. At last, on the 25th, the 2/14th Battalion, with part of a battery of the 2/4th Field Regiment, landed at Kaiapit. While patrols of Papuans searched the foothills, Dougherty instructed Captain Rose-Bray,26 now commanding the 2/6th Independent Company, to reconnoitre Narawapum. That day the air force struck Marawasa, and “frightened six months’ growth out of [the 2/6th Independent] Company by dropping auxiliary belly tanks within a hundred yards”.

During these last nine days Lieut-Colonel MacAdie’s Bena Force had been maintaining its watching brief over its vast area of mountains and valleys fronting the Ramu River. Patrols of Bena Force were trying out the crossing places over the Ramu in preparation for new operations. On the 20th a patrol from the 2/7th Independent Company reported that the Gusap and Ramu Rivers were in flood. One man, however, swam both rivers and reconnoitred Bumbum, naked and unarmed. Here he saw seven Japanese before he again swam the rivers. Two days later patrols from the most western platoon of the 2/2nd Independent Company reported that they were unable to cross the Ramu between Sepu and Yonapa.

“When I get to Marawasa,” wrote General Vasey to General Herring on the 22nd, “will Bena Force come under my command? I think it should so that they may clear the hills north of Bena Bena and join me on the Ramu west of Dumpu.” Herring agreed, and decided that Bena Force should be placed under Vasey’s command before Marawasa was actually reached by the 7th Division. Gradually Bena Force began to press forward and even to cross the Ramu. In conformity with higher plans MacAdie had been holding his men on a leash for several months, but it now seemed obvious that Bena Force would have to clear the way ahead from Dumpu as far west as Kesawai at least.

On the 24th a patrol of the 2/7th reported that the enemy was occupying Dumpu and the mouth of the Uria River. There were now, however, no Japanese in Bumbum although there were signs that a small Japanese party had moved from there to Kaigulin recently. By dusk on the 24th another 2/7th patrol reported that there were about 100 Japanese in Arona on the upper slopes of Mount Woodfull and that there seemed to be a large number of Japanese at Marawasa.

The 2/2nd prepared to patrol the Kesawai and Evapia River areas directly opposite Maululi. Corporal J. F. Fowler led a routine patrol to Waimeriba on 23rd September and found unmistakable signs that the Japanese had set up an ambush at the Wei River crossing south of the Ramu and had waited there hopefully but without reward for about a day. At midnight on the 23rd–24th September Lieutenant Nagle27 and two

men crossed the Ramu and sneaked28 as close as they could to Kesawai which they identified by smoke from fires, wood-chopping, voices, and stray shots probably from pig-hunting parties. When watching and listening in a dry watercourse the patrol was suddenly confronted by one of the pig hunters who was immediately shot. As the patrol rapidly withdrew another startled Japanese met them and “fell on his haunches in a cowering suppliant attitude”. Farther east on the night of 23rd–24th September Lance-Corporal J. W. Poynton led a two-man patrol across the Ramu near its junction with the Evapia River. This was a difficult area for patrolling undetected because the natives seemed pro-Japanese and many were armed. Nevertheless the three men did manage to watch from a high observation post the activities of native carrying parties escorted by a few Japanese moving from the Evapia towards Kesawai. When the patrol was discovered by the native observation posts the three raced for the Ramu and escaped from a pursuing force of 9 Japanese and about 50 natives.

MacAdie had been expecting that the attack on Lae might precipitate an enemy attack in strength across the Ramu River to the Bena-Mount Hagen plateau. However, the Japanese had not crossed the river for some time, and it almost seemed that they might be thinking of withdrawing not only from the Markham Valley but also from the upper Ramu. If the Dumpu-Kesawai area could be cleared before the arrival of the spearhead of the 7th Division, Bena Force would indeed have fulfilled a useful task.

The enemy must have been in something of a quandary at this stage. The vanguard of the 78th Regiment had been soundly thrashed at Kaiapit. If they crossed the Ramu they encountered resistance at various points along a front of 100 miles. Not only that, but the XVIII Japanese Army had met parties of Australians from Mosstroops, AIB and FELO in the remote west of the Sepik Valley on several occasions. The Japanese commander must have wondered how many Australians were in the area, for one of his patrols from Atemble had driven out one of MacAdie’s patrols at Kumera far down the Ramu on 20th September. The loss of wireless equipment, maps and codes by this Australian patrol was perhaps balanced by the enemy’s fear that the Australians were everywhere.29 His reconnaissance aircraft had also seen the rapid construction of roads, bridges and buildings on the Bena plateau.

Determined to gain all possible information about the area between Dumpu and the 21st Brigade, MacAdie instructed Captain Lomas of the 2/7th Independent Company to send out two linking patrols on the 26th. Lieutenant Dunshea set out on a long patrol direct from Lihona in the upper Ramu Valley through the Dumpu area and down the Markham Valley to Kaiapit. Lieutenant Danne’s patrol took a more indirect route from Kainantu, through Onga to Kaiapit. He arrived at dusk and reported

that there were no signs of Japanese having been in the area for the past month.

Back at Kaiapit patrolling and building up of stores continued. Lieutenant Crombie found on the 26th that Rumu, forward from Sagerak, was unoccupied. With all this evidence of a non-aggressive enemy confronting him Dougherty was anxious to get moving. Vasey understood his feelings for, on the 26th, he sent him a message –

I am terribly sorry about the delay in getting 25 Brigade up to your area but this b–––y Air Force is too tiresome. I cannot guess when the move will be completed. In the meantime I would like you to get all possible information of the Jap, particularly in the foothills east of the Umi. I have a feeling that he will not now attack us at Kaiapit but has withdrawn 51 Div to Marawasa area where we shall have to attack him.30 If you can confirm this feeling for me it will save time when 25 Brigade does come up and I remove your leash. Will you consider the possibility of crossing the Umi at night so as to get a flying start for Marawasa at daylight on the day you do move? I don’t know whether this is practicable.

Unfortunately the 25th Brigade did not begin arriving until the 27th. At a conference in Port Moresby the previous day between Generals Mackay, Herring, Berryman, Kenney, and Admiral Carpender, Kenney had pointed out that his air resources were so strained that he would be unable to move the 18th Brigade from Port Moresby unless the tactical situation demanded it. He had also urged that the construction of the Lae–Nadzab road was all important. Thus Vasey knew that once his two forward brigades were committed he would not be able to use his third brigade as a reserve except in an emergency.

Vasey protested to Herring that the delay was “giving the Jap adequate time to implement any plan he may have for controlling the upper reaches of the Markham and Ramu Valleys”. He thought that, if the Japanese decided not to attack Kaiapit, “the most likely Japanese course now appears to be to hold the Valley in the Marawasa defile”. He pointed out that, although the Fifth Air Force had two squadrons of transports available at Nadzab, the restriction on landing at Kaiapit between the hours of 9.30 a.m. and 3.30 p.m., imposed by the Americans on the 26th evidently because of shortage of forward-based fighters, reduced by more than 50 per cent the number of possible landings at Kaiapit.

“I am not in the position to know of the Air Force’s problems,” he wrote, “but I would stress that until the rate of movement can be increased considerably, the progress of this division towards Dumpu, or even Marawasa, will be materially delayed.” Vasey was right – he was not in a position to know. The Air Force was fully committed and the reinforcement of Finschhafen took priority.

Only the advanced headquarters of the 25th Brigade arrived at Kaiapit on the 27th. The planes were now landing on the new airstrip which had

been built mainly by “Marys”, under the direction of Angau officers, as the native men had been recruited for the carrier trains.

As patrols from the 2/6th Independent Company and the Papuans reported on the 26th and 27th that Narawapum was deserted and that natives said that the Japanese had retreated across the Umi River, Vasey decided to wait no longer. Late on the 27th he signalled Dougherty that if he was convinced that there were no enemy east of the Umi he was to cross the river on the night of the 28th–29th September and move as quickly as possible to Marawasa.

Dougherty promptly ordered Sublet to send two of his companies across the Umi to hold the crossing. On this occasion the leading company crossed the river in eight minutes soon after midday and formed the bridgehead. The second company to cross occupied Sagerak and sent forward a patrol under Lieutenant Bremner31 to clear and hold the Maringgusin area. By 5 p.m. Bremner reported that the area was clear and that the track from Sagerak to Maringgusin was suitable for jeeps. Half an hour later the rest of the battalion crossed the river in rubber boats and dug in at Sagerak. The 2/14th and 2/27th Battalions, relieved at Kaiapit by the arrival of the 2/31st and 2/33rd, followed across the river. When dawn broke on the 29th Dougherty was ready for a sprint to the west.

On 27th September two patrols from the 2/7th Independent Company were already crossing the areas between their Kainantu base and the vanguard of the 21st Brigade. “You will continue with your present role,” said a message from 7th Division to MacAdie on the 27th. “GOC will visit 28th September if possible.” Encouraged by MacAdie, Major Laid-law of the 2/2nd decided that the “present role” was a little too inactive. On the afternoon of the 27th therefore he signalled Captain Dexter at Maululi that further information was required about the enemy in the Kesawai area and that the platoon should “take advantage of all favourable chances to harass”. Thus when Vasey was flown into Bena Bena on the 28th a strongly-armed patrol from Maululi had already set out to cross the Ramu two miles west of Waimeriba.

Leading a patrol which consisted of Lieutenant Fullarton’s32 section, a few men from platoon headquarters, two police boys and five lowland carriers, Dexter reached the crossing at 3.30 p.m. and took compass bearings on Kesawai. A route for the night advance on Kesawai and the all-important rendezvous were selected before darkness fell. Three Australians, a police boy and the carriers were left to cover the crossing. The patrol to cross the river was armed with 2 Brens, 9 Owens and 4 rifles besides a liberal supply of grenades and a grenade discharger.

In pitch darkness at 9.30 p.m. the patrol prepared to cross the Ramu which was here flowing in eight streams, the bed of the river being about

half a mile wide. The last stream was a very difficult one to cross but, as the strong swimmers had already taken a wire across the river, the patrol crossed safely and the Brens were kept dry. At 11 p.m. the patrol marched off on a bearing of 87 degrees through kunai, swamp, creek beds, pit-pit and bamboo until it reached the fringe of the rain forest in the foothills of the Finisterres about 1.30 a.m. on the 29th. Wet and weary and with many barked shins, the men lay down to get what rest they could, assailed by hordes of mosquitoes. At 6.30 a.m. the patrol had its breakfast of bully beef and biscuits, and half an hour later moved to a spot west of Kesawai where an ambush was set.

From previous reconnaissance it was thought impossible to find Kesawai because of the heavy timber in the surrounding country. Rather than stumble on unknown Japanese positions it was therefore decided to try and lure the Japanese towards the ambush. At 7.40 a.m. Lance-Corporal Poynton, Private Birch33 and police boy Tokua advanced boldly for about a mile and a half east towards Kesawai. Just outside this Japanese base the patrol was sighted and fired on by the Japanese. Half an hour after setting out the patrol returned briskly.

All was quiet and tense after Poynton made his report and the men wondered whether the ruse would be successful. They were arrayed in a semi-circle on both sides of the track with their weapons pointing towards the bend about 100 yards away. At 9.50 a.m. there was some noise to the east and round the bend came two natives armed with bows and arrows followed by many Japanese in twos and threes, watching the tracks made by Poynton’s men and talking and gesticulating. Over 60 had rounded the bend and the leaders were within 30 yards of the ambush when the Australians opened fire. The heavy volume of automatic fire was like a reaper’s scythe among the Japanese. A few staggered back around the corner and some dived down the slight slope on the right flank where Private Campbell’s34 Bren raked the bushes. Fullarton’s Bren firing straight down the road was responsible for many of the Japanese casualties.

A large Japanese force now moved rapidly west from Kesawai towards the ambush. Taking up positions around the bend in the road they returned the fire of the Australians who were now running short of ammunition. One man was killed and Dexter wounded. On a pre-arranged signal the action was broken off and the men disappeared silently and rapidly south of the road to the rendezvous, whence they raced for the Ramu and crossed it in broad daylight. The Japanese had misjudged the Australian line of withdrawal, and scoured the kunai-covered foothills of the Finisterres.

The Japanese had been hit hard at Kaiapit in the Markham Valley and now at Kesawai in the Ramu. It was little wonder therefore that Major-General Nakai decided that he could best draw the Australian force and

so facilitate the retreat of the 51st Division, not in the river valleys, but at Kankiryo Saddle. Only delaying forces were left in the river valleys while the Japanese prepared their defences in the difficult Finisterre Ranges.

Vasey informed General Herring that he intended to move the 2/2nd and 2/7th Independent Companies into the Ramu Valley as the forward elements of the 7th Division moved to the North-west. As far as Vasey was concerned the Bena Bena-Mount Hagen plateau did not now need to be garrisoned. Besides the two Independent Companies there were about 38 specialist troops, 40 Angau men and 120 Americans, whose main task was to keep the new Garoka airstrip in operation as a forward or emergency airfield and to establish a radar station. The troops on the plateau would need some local protection, and Vasey recommended that one militia company be stationed there.

On 29th September the 21st Brigade had been moving more rapidly westward from Sagerak through the overpowering heat of the kunai-clad valley. Behind the advance some jeeps and light guns were dragged across the Umi but beyond Sagerak the track soon became impassable. The Sagerak strip was made ready during the day and transport aircraft landed bringing jeeps and trailers; and Vasey arrived in his Cub.

There was nothing to stop the advance; Lieutenant Dunshea’s patrol from the 2/7th Independent Company arrived at brigade headquarters early in the morning from the Dumpu area, and reported that Marawasa (where Vasey had expected the enemy to make a stand) was deserted. The 2/16th Battalion had previously occupied Wankon Hill, a natural observation post about 300 feet above river level with observation far into the Ramu Valley beyond Marawasa, and patrols from the 2/16th had probed forward and confirmed that Marawasa was empty. The 2/14th Battalion pushed through to occupy it by 5 p.m. The 2/27th Battalion which had had some difficulty crossing the Umi occupied the Wankon villages. From Wankon Hill at night the 2/16th could see many fires on the north side of the Ramu among the foothills: these may have been native hunting fires or they may have been the fires of Japanese withdrawing before the 2/6th Independent Company to Atsunas along the right flank of the 21st Brigade.

The remainder of the 25th Brigade arrived at Kaiapit by dusk on the 29th, and late at night Brigadier Eather issued his orders for an advance to the Umi next day by two battalions, leaving the third, the 2/25th, to guard Kaiapit until it could be relieved by the 2/2nd Pioneers.

At Ragitsuma on the afternoon of the 29th Vasey and Dougherty discussed the future. Vasey’s instructions were left with Dougherty in a document called “Development of Operations”. “All our information points to the Jap withdrawing North-west to the Marawasa area,” it began. “Whether he will attempt to hold the line of the Gusap River or will continue to fall back towards his MT road from Bogadjim is not yet clear.” After saying that the enemy’s main line of withdrawal seemed to be along the North-east side of the river valley, Vasey continued: “It

is not my intention at present to follow the Jap along the North-east side of the valley but rather to move along the southern side and secure his crossings over the Gusap River wherever they may be.” Vasey therefore decided that the 21st Brigade would move along the south part of the river valley to the Gusap and then eastwards along that river until the Japanese crossing place was found.

The advance of the 21st Brigade along the main valley and of the 2/6th Independent Company on the right flank – actually in pursuit of the 78th Regiment along the North-eastern side of the valley – continued rapidly on the 30th. The 2/16th Battalion again took over the lead and had one of its most gruelling day’s marching. The day’s objective for the battalion was Arifagan Creek, but as this was an inhospitable and waterless area the battalion pushed on to the bank of the Ramu. In the battalion’s report the crossing of the river divide between the Markham and Ramu was described as follows: “It was a complete surprise to most of the battalion to learn that during the day’s march – actually just before reaching Arifagan Creek – they had crossed the divide between the Markham and Ramu River basins. The divide was impossible to pinpoint on the ground as the gradients were imperceptible. The only visible indication that a divide had been crossed was that rivers were now flowing in the opposite direction from the Markham drainage basin.” The 2/27th followed the 2/16th across Arifagan Creek.

Since early on the 29th the 2/6th Independent Company, advancing on Atsunas by the northern track, had been out of wireless contact. Dougherty intended the company to follow and harass the enemy in the Ragitsaria area, but he decided not to move the 2/14th Battalion forward until he knew where the Independent Company was. It was not until late in the day, when Lieutenant Hall’s newly-arrived Papuan platoon managed to make contact with Captain Rose-Bray, that Dougherty decided to send the 2/14th about a mile beyond Marawasa. The Independent Company had left Asia early on the 30th following native guides. All “information” from native rumours seemed to indicate that the Japanese had retired through this area a few days previously. The Atsunas natives said that about 80 Japanese had passed through there on the 26th carrying several wounded. Their footwear and clothing were in bad shape, their ammunition light and some were without weapons. It therefore seemed to Rose-Bray that the Japanese had retired up the track to the Gusap River. Soon after midday the company reached Marawasa where Rose-Bray reported to brigade headquarters and learned that Papuan patrols and aircraft had been out looking for him. Dougherty then ordered the company north to Ragitsaria to harass any Japanese there.

Late on the evening of the 30th Dougherty received an unpalatable message from divisional headquarters saying that the 25th Brigade would not cross the Umi until further orders. No reason was given, but this information affected Dougherty’s decision about his moves for the next day. If the 25th Brigade was to follow he could advance to carry out the role as set out in the document which Vasey had left with him on the

29th. If, however, the 25th Brigade were not coming and Dougherty had to fight a battle alone, he would have to leave some of his brigade round the landing strip.

The main reason for this change in plan was that Vasey, on the 30th, received a message from General Herring that, because of commitments at Finschhafen, Generals Mackay and Herring did not wish to become heavily committed in the Markham and Ramu Valleys. The main efforts were now bent on reinforcing Finschhafen. Indeed it soon appeared that the main body of the 20th Japanese Division, which Vasey had anticipated meeting near Marawasa, was, in fact, not advancing down the river valleys but round the Rai Coast, by barge and any other available means, and over the inland trails towards Finschhafen, and that the 78th Regiment alone faced the 7th Division. This change in Japanese plans made Nakai’s decision to hold at Kankiryo Saddle, and not in the Markham or Ramu Valleys, the only possible one. The Australians were not yet aware of the precise Japanese decisions but their general intentions were rapidly becoming apparent.

Herring now gave Vasey three tasks: first “to prevent Japanese penetration southward through the Ramu and Markham Valleys”; secondly, “to seize the Marawasa area with a view to further advances to Dumpu after 18th Australian Infantry Brigade has become available and the maintenance situation permits” – the 21st Brigade had in fact already seized the Marawasa area; and thirdly, “to ensure the protection of Allied Air Force installations in the Bena Bena-Garoka area”. The force to be maintained in the Kaiapit area would not “be reduced below one infantry brigade without reference to this headquarters”.

There was also the supply situation to consider. By the evening of the 30th the 2/16th Battalion spearheading the advance along the Ramu was well ahead of its supply columns and rations had to be dropped from aircraft that evening and next morning. Progress had been so rapid during the last few days that service troops and stores were left far behind, thus necessitating the dropping of stores from the air, a never-very-satisfactory procedure. The problem of supplying the Independent Companies, which were in remoter areas than the battalions, was more difficult. For instance, the heavier gear of the 2/6th Independent Company, dumped before the Kaiapit action, was only now catching up to the company and the men were at last receiving their bed rolls. On the Bena Bena plateau itself there was little difficulty in living off the land provided enough cowrie shells and salt were available for barter, but once the men crossed the Bismarck Range the supply problem became very acute.

On 1st October General Vasey reported: “Bena Force reports Japs withdrawn from positions held for some time. This, together with lack of contact by 21st Brigade, strongly indicates Japs withdrawn from Markham and upper Ramu Valleys.” He therefore decided to bring an Independent Company from the plateau into the Ramu to make sure that the area ahead of the 21st Brigade was clear. On the same day he signalled MacAdie:–

In view rapid advance 21st Brigade concur in your suggestion to concentrate 2/7th Independent Company Bumbum area where contact will be made with 21st Brigade.

Vasey flew to Lae for a conference with Generals Mackay, Herring, Milford, Wootten and also General Morshead who was preparing to take over in New Guinea at a later stage. The conference mainly concerned the Finschhafen situation, but the Ramu Valley operations were also discussed. Vasey said that, having achieved his original objective, he now required further orders and, as his maintenance was by air, an advance of a few miles would not affect his administrative plot. There was no objection to him pushing on to Dumpu but he was not permitted to remove the whole of the two Independent Companies from the Bena Bena plateau. Vasey thereupon ordered Dougherty to concentrate on the Gusap on the 2nd; Eather would arrive there on the 3rd.

On 2nd October the 7th Division made ready for its punch at Dumpu. By dusk the 25th Brigade was camped in the Marawasa area and it was here that reinforcements arrived to build the 2/33rd Battalion up to strength after the disaster at Port Moresby. The 2/14th and the 2/27th Battalions moved up to the junction of the Gusap and Ramu Rivers during the day and the 2/16th established a bridgehead across the Gusap.

Pushing on from the Gusap Captain G. W. Wright’s company of the 2/16th picked up a message left on the track by Dunshea in which he said that the Japanese were not in Bumbum and Boparimpum on 28th September. Wright crossed the Tunkaat River on his way to Kaigulin, but heard firing from trees about 1,000 yards ahead. The 2/7th Independent Company was on its way into the Kaigulin-Bumbum area. Lomas reported to Dougherty at the junction of the Gusap and Ramu Rivers about the time when the 2/16th Battalion was starting to cross the Gusap. The firing heard by Wright’s men came from a Japanese outpost in Kaigulin which contested the crossing of the Ramu by the forward troops of the 2/7th Independent Company. The Australian patrol withdrew to the south side of the Ramu.

About 4.30 p.m. a patrol from the 2/7th managed to cross the Ramu elsewhere and work round on the right flank. Wright’s men then moved straight into the attack and, half an hour later, struck opposition from the enemy outpost. One Australian was killed but the enemy was driven out leaving six killed, including one who had been decapitated with a captured Japanese sword brandished by the leading platoon commander, Lieutenant R. D. Watts.

Elsewhere in Vasey’s area extensive patrolling continued during the 2nd, mainly by the Independent Companies. The 2/6th found plenty of evidence in the foothills of the recent presence of the 78th Japanese Regiment. At Mesagatsu they found signs of a Japanese headquarters – staging camp, foxholes, dugouts, shelters of all descriptions and even a two-storey hut. The Papuans were also patrolling the foothills from their base at House Sak Sak, and assisting in the construction of the

airfields. Since the Kesawai ambush, patrols from Maululi, now commanded by Captain D. K. Turton, were probing the tracks and foothills on both sides of Kesawai. On the far west flank the main difficulty encountered by Captain Nisbet’s platoon was in crossing the flooded Ramu. One patrol tried to cross on the night 30th September-1st October. Placing all their gear on top of a raft the swimmers tried to propel the raft across, but swimmers and raft were swept downstream, collided with a snag which caused the raft to overturn, and all gear was lost. Major Laidlaw determined that in future a lifeline would be strung across the river to assist crossings. As a result of MacAdie’s requests an aircraft on the 3rd dropped Mae Wests and cordage at Bundi.

On this western flank native police sent out by Angau reported that the enemy were now keeping a mere skeleton force at Sepu, Usini, Obsau and Glaligool while more substantial bodies of troops were at Urigina, Kulau, Egoi and other places in this general area South-west of Madang. The main body of troops formerly in this western area, however, had been recalled to meet the threat from the Markham Valley. A small patrol led by Corporal Harrison between 28th September and 4th October found that there were actually no enemy in New and Old Glaligool35 or Sepu.36

The 3rd October was a Sunday and, while waiting for the 25th Brigade to move up to House Sak Sak, Dougherty restricted his brigade’s activities to patrolling only, while his men enjoyed a swim in the Ramu and Gusap Rivers and “the administrative side of affairs was consolidated”. After this spell the battalions were fresh and ready for the final advance on the 4th.

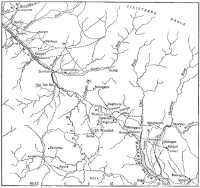

Early on the 4th the 21st Brigade set out towards its western objectives – the 2/14th on the right flank towards Wampun and the 2/16th on the left flank towards Dumpu. Farther down the Ramu the Japanese were again hit from Maululi when a patrol led by Lieutenant Nagle attacked an enemy outpost in the village of Koropa about 10 miles west of Kesawai. Nagle was killed and although only a few Japanese were accounted for, this further evidence of the Australian intention to strike the enemy all along the Ramu Valley undoubtedly helped to cause the Japanese commander to pull in his remaining outposts in the river valley.

By 2 p.m. Captain C. L. McInnes’ company of the 2/14th found Warn-pun deserted, as expected. After a hot and tiring day’s march the native porters, who carried no water, had nothing to drink or cook their rice in. Colonel Honner, therefore, sent McInnes’ company towards Karam to find whether the area was clear and also to look for water. The company moved west and then climbed rising ground on the right where they

The 2/14th Battalion action, 4th October

had a more secure position and a better view. A second company was sent to the east and a third to the South-west of Wampun.

Honner soon after 2 p.m. decided to follow the trail of McInnes’ company towards Koram to find whether there was any water in this vicinity, so that he could quickly reach a decision whether to push on towards the next day’s objective or ask for water to be sent up by jeep. Later he was joined by a water party consisting of Sergeant Pryor37 and three others. After about a mile Honner’s small party saw a banana plantation and noticed troops moving about breaking down banana leaves. As these ignored his approach Honner assumed they were from McInnes’ company. The banana plantation was astride the main track and merged into a belt of vegetation stretching across the river valley. The track itself ran North-west towards the plantation through kunai grass, a patchy regrowth after fire, varying from two to four feet in height.

The small patrol was about 130 yards from the plantation when a burst of machine-gun and rifle fire wounded both Honner and Pryor. Pryor, wounded in the chin and the chest, tried to drag his commanding officer back but Honner, wounded in the thigh, and only able to crawl with difficulty, ordered him to return to the nearest company with information about the strength and position of the enemy. On his way out Pryor met Private Bennett,38 one of the other three. Bennett decided to stay with Honner, who had crawled, using hands or elbows and one leg, about 250 yards into tall kunai. The enemy now sent out patrols towards these two men. The Japanese fired into the kunai and hit Honner again, in the left hand. Bennett was preparing for a one-man charge when fortunately the patrols stopped short and returned to the banana plantation.

After crawling 500 yards Pryor reached a dry watercourse where he got up and bolted down the track towards the battalion position picking up the other two men on the way. On receiving Pryor’s report, Captain O’Day39 immediately sent out a lightly-armed platoon under Lieutenant

A. R. Avery to move fast to Honner’s rescue and then followed with another platoon with heavier weapons.

Leaving O’Day to move cautiously towards the scene of action the adjutant, Captain Bisset, branched off to try and trace McInnes’ company. McInnes had already sent a patrol to find out what was happening when he heard the firing. Although this patrol located the direction of the firing they could see nothing of the action. Bisset then suggested that McInnes should secure the high ground stretching for a distance of about 1,500 yards on the right of the banana plantation.

At 4.30 p.m. Avery’s patrol, under fire, found Honner and Bennett. Using Avery’s wireless set the wounded battalion commander ordered Bisset to arrange that two companies be sent forward to make an attack and to ask brigade headquarters to send up water by jeep if none had yet been found. As McInnes’ company was already moving to the high ground and could not be brought into position for an attack, Bisset, who had now returned, and the senior company commander, Captain Hamilton,40 decided to send forward Hamilton’s own company, commanded by Lieutenant Levett,41 to support O’Day’s. Honner, still in full control of his battalion, was told of these changes and also that a stretcher party was going forward for him. While there was so much firing Honner refused to allow the stretcher party to come forward from a dry watercourse 300 yards behind him for fear of unnecessarily endangering the men’s lives.

At 5 p.m. O’Day reached Honner, who told him his plan of attack: by Levett on the right with O’Day swinging out to the left and attacking through the plantation from that side. At 5.30 p.m. O’Day collected his two platoons in the watercourse, led them round to the left and began his attack. As the enemy’s fire was now concentrated on the attackers, the stretcher bearers came up to Honner and adjusted his field dressings and, crawling, dragged him on a stretcher for 150 yards through the grass before rising and carrying him back to the watercourse. Here Honner met Levett’s newly-arrived company, rapidly gave them the necessary information, and sent them in through a scattered line of trees on the right.