Chapter 16: Scarlet Beach to the Bumi

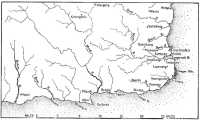

GENERAL MacArthur’s operation instruction issued on 13th June 1943 had given the general outline of the Allied offensive: “Forces of the SWPA supported by South Pacific Forces will seize the Lae–Salamaua–Finschhafen-Markham River Valley area and establish major elements of the AF therein to provide from the Markham Valley area general and direct air support of subsequent operations in northern New Guinea and western New Britain, and to control Vitiaz Strait and protect the North-western flank of subsequent operations in western New Britain.”1

By 16th September Lae, Salamaua and the Markham Valley east from Nadzab were in Australian hands. The success of the attack on Lae from east and west and the speed with which this vital area had been captured caused a quick readjustment of plans. American misgivings about Australian planning, which for the time being was concentrated solely on the capture of Lae, have already been related. Under hard-headed battle-seasoned leaders the Australians’ planning was of a more flexible and practical nature and they were more ready for emergencies and more able to profit by unexpected opportunities. Such an opportunity seemed now to have presented itself.

Because the Australians had produced no detailed plan for the capture of Finschhafen before Lae was assaulted, this did not of course preclude the staffs from having plans ready to exploit any sudden success. Indeed a broad plan had been produced at General Herring’s I Corps headquarters on 24th August 1943 for the capture of Finschhafen by a brigade group of the 9th Division, after which the 9th Division would carry out shore-to-shore operations to Bogadjim and the 6th Division exploit to Madang. Herring decided that the landing should be made just south of the Song River.

In the early stages of planning (wrote General Blamey later) the operation necessary for the capture of Finschhafen had been studied, but completed plans were not prepared since its capture would be dependent on the amount of enemy resistance encountered at Lae and the length of time necessary to reduce it. It was considered that, if the capture of Lae was effected quickly, a brigade group from 9 Aust Div could be used to carry out the operation against Finschhafen.2

As in the days before Lae, the American Navy and Air Force and the Australian Army were busy with cooperative planning for a landing in the Finschhafen area, even before Lae fell. At a conference with the Australians at his headquarters in Buna, Rear-Admiral Barbey, on 9th September, stated that craft for an attack on Finschhafen could not be made available until ten days after the capture of Lae. He had originally been planning for a four weeks’ gap. On 16th September General Cham-

berlin telephoned General Berryman in Port Moresby, stating that General MacArthur desired the capture of Finschhafen as soon as possible. Next morning, the day after the fall of Lae, MacArthur called a conference at Port Moresby to discuss accelerating the assault on Finschhafen. He and Blamey agreed that a brigade group of the 9th Division should be sent to the Finschhafen area as soon as possible and that Herring should determine the date. Because of the uncertainty about enemy strength at Finschhafen, Blamey thought that more than one brigade would be necessary. He wrote later:–

I requested that an additional brigade group be moved to the Finschhafen area immediately after the assaulting force had made the landing. This was approved and Commander I Aust Corps was so informed and laid his plans accordingly.3

Towards midnight on the 17th Herring arrived at Lae by PT boat for discussions with General Wootten. Even before the Allied armada had left Milne Bay for the beaches east of Lae, Wootten had been warned by Blamey and Herring that he might be required to carry out an attack on Finschhafen at short notice, and Wootten had told Brigadier Windeyer to look at Finschhafen on the map because it might interest him later.4 Before Herring’s arrival at “G” Beach warning orders were already passing down the line. At 2.30 p.m. Lieut-Colonel R. J. Barham, Wootten’s principal staff officer, rang Windeyer’s headquarters and asked that Windeyer be informed immediately that a brigade would soon be required for an amphibious operation. Later that night, shortly before Herring landed, another message was received by Windeyer that a planning team from the 20th Brigade for “a future operation” was to attend a conference at divisional headquarters next morning. At 9 a.m. on 18th September Windeyer and his staff attended this conference at 9th Division headquarters on the Bunga River. The conference was attended also by the commanders and principal staff officers of I Corps and the 9th Division. Herring outlined a plan for the capture of the Finschhafen-Langemak Bay-Dreger Harbour area with a quick swoop which would help to gain control of the east coast of the Huon Peninsula and thereby of Vitiaz Strait.

Confidence and boldness marked the planning of this operation. It was unusual in three respects: Allied troops rarely undertook large infantry assaults through jungle at night, let alone after landing on a hostile shore; the notice for mounting the operation was so short as to be probably unique for an amphibious undertaking of such size, particularly when it is considered that the troops were a long day’s march from their assembly areas; the information about the enemy available to the commander could hardly have been more nebulous. A New Guinea Force Intelligence summary of 15th September had put the strength of the enemy round Finschhafen at 2,100, but after the fall of Lae this was reduced to 350, which was the

estimate of the GHQ Intelligence staff. On 18th September the I Corps estimate was “between 1,800 and 350”; the 9th Division’s, however, on 19th September was between 4,000 and 1,500. The divisional staff estimated the strength of units identified as probably being at Finschhafen at 2,070. Windeyer, however, had received only the Corps estimate when he made his outline plan and thus all he knew was that some people considered that the brigade would encounter only about 350 Japanese and some that it would encounter 1,800, and that no sizable fighting force would be round Finschhafen.

The reason why such confusing estimates were reaching the field formations was that the GHQ Intelligence staff headed by General Willoughby and the LHQ Intelligence staff headed by Brigadier Rogers,5 each working on different principles, had, on this as on other occasions, reached very different answers. These could not be reconciled and as a result the field formations were given both figures.6 As shown above, when the various estimates reached the fifth link in the chain – the 9th Division – it rejected the lowest figure, 350.

The 20th Brigade was selected for the landing as it already had the experience of carrying out the initial landings east of Lae and was also relatively fresh. Wootten felt that the task was too much for one brigade and wished to use the division less one brigade. Herring explained, however, that a brigade group was the maximum which MacArthur would allow, taking into account the opposition expected, the difficulty of maintaining a larger force, and the limitation of the available naval resources. The craft already allotted by Barbey for the landing – 4 APDs, 15 LCIs and 3 LSTs – (in addition to 8 LCMs from Colonel Brockett’s boat battalion) were capable of lifting only a brigade group. To aid in supplying Windeyer’s brigade a boat battalion and half a shore battalion from the 532nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment would be available.

Among Herring’s reasons for selecting the beach south of the Song as the landing place were the facts that a landing south of the Mape River would involve the crossing of this major obstacle, and that from aerial reconnaissance and information derived from former residents the only suitable beach appeared to be the one chosen. The beach was called Scarlet Beach to avoid confusion with Red Beach – at this period the main landing beach was usually named “Red”. A further reason for choosing a beach well north of Finschhafen was that most Japanese troops were thought to be facing south near Langemak Bay expecting a coastal advance, and thus a landing at Scarlet Beach would cut their line of supply and withdrawal. Although it was known that there were several enemy garrisons on the coast towards Madang, it was felt that air and PT boat attacks on Japanese coastal traffic would prevent a rapid buildup. “The operation was hurried forward to forestall such a move and was

successful, though substantial movement of enemy troops was already taking place southward as was later discovered. By 22nd September the enemy strength in Finschhafen was approximately 5,000 all ranks.”7

Lieut-Commander Adair, who represented the American Navy at the conference on the 18th, was anxious that the landing should take place soon after moonrise on D-day. On 22nd September moonrise would be at 25 minutes past midnight. The Americans were anxious to unload the craft and leave the beach before first light because of the danger of air attack. Windeyer did not favour landing in darkness because he doubted whether the navy could land them on the correct beach, and in this Wootten supported him. Adair was confident, however, that, because of the irregular and distinctive coastline, consisting, except for Scarlet Beach, of cliffs 15 to 20 feet high fringed by coral reefs, the navy could not fail to find the correct beach even if clouds obscured the moon. Because of the difficulty of resupplying Windeyer on this beach, it was decided that he would take with him supplies for twenty days.

It seemed inconceivable that Scarlet Beach would not be defended. Actually ten men, four of them natives and the remainder American “amphibian scouts” of the 532nd EBSR, had been put ashore near Scarlet Beach during the night 11th–12th September in rubber boats launched from PT boats. Because of Japanese activity in the area, they were unable to obtain the desired hydrographic information and were withdrawn on the 14th. They saw no guns but thought there were machine-gun nests at the north end of the beach. Although the information gathered by this reconnaissance party was useful and, as far as it went, accurate, they were unable to establish definitely whether the beach was defended and may well have been observed themselves.

As a secondary and later objective, Windeyer was ordered to be ready to capture Sattelberg.8 It was also decided that, concurrently with the landing at Scarlet Beach, a landing would be made on the Tami Islands, South-east of the Huon Peninsula, to establish a radar station. Windeyer also suggested that a battalion should move round the south coast of the Huon Peninsula from Lae to Finschhafen to deceive the Japanese as to the real direction of the threat. The suggestion was approved in principle, but it was agreed that the battalion would not begin its advance before the landing lest it prejudice surprise.

At 5 p.m. on the 18th Windeyer explained his outline plan to Wootten. Briefly, it amounted to an assault on the beach-head by two battalions, the 2/17th on the right and the 2/13th on the left. After the beach-head had been secured the 2/15th Battalion would advance south along the main road towards Finschhafen. If heavy resistance were met frontally on the coastal plain, troops would advance along the fringe of the hills to the west in order to outflank the Japanese. Both agreed that the time for landing desired by the Americans was not suitable.

That evening a further conference was held between the commanders and staffs of corps, division and brigade. Windeyer asked that the operation be postponed a day as his troops were tired from constant marching and road work, and still had half a day’s march ahead before reaching the concentration place at the mouth of the Burep. Windeyer wanted time to issue orders, give his troops some rest, instruct them fully in their tasks, and assemble the artillery and stores. Herring agreed that the expedition should leave “G” Beach on the evening of 21st September and land at Scarlet Beach on 22nd September.

Windeyer then asked that the landing should be made at first light – 5.15 a.m. To the Australians this appeared to be the earliest time which would give the assaulting battalions some light for work in the jungle; and, more important, would ensure that the navy landed them on the correct beach. Adair stuck to his original arguments that the landing should be as soon as possible after moonrise. To overcome the American objection to the late unloading of the LSTs and the consequent danger of air attack, Herring decided to reduce the amount of supplies to be carried from 20 days’ to 12 days’ supply of ammunition and 15 days’ supply of rations. The average load of each LST would thus be reduced to between 115 and 120 tons. Wootten then asked Adair to arrange for the first re-supply mission to take place five days after the landing.

While the staffs were completing the details of their plans, infantry commanders told the troops what their tasks would be. They were shown their objectives on sand models and the general plan was explained. The speed with which the operation was planned, organised and launched was evidence of the training, experience and discipline of the 20th Brigade.

There were many others, of course, with fingers in the planning pie. While the Lae conferences were taking place on the 18th, General Berryman and Colonel L. de L. Barham (brother of General Wootten’s GSO1) were conferring with Admiral Barbey and General Chamberlin aboard the Conyngham off Buna. D-day and H-hour were discussed, but no finality was reached because Herring was still at Lae. Barbey stated that while the Japanese were using the Cape Gloucester airfield it would not be possible to supply Finschhafen continuously. The main conference occurred on the 19th. Writing to Wootten on the same day, Herring reported the conference thus:–

Reached Buna safely about 6 a.m. and was taken straight to Admiral Barbey’s destroyer where I found Berryman and Chamberlin waiting for me to hear how and when we planned to take Finschhafen. So I set in to tell them and when the tale was told the Admiral wanted 0200 hours as H-hour. I refused to budge, but when it became clear that my continued refusal to what had gradually become only one half hour’s change, would involve a reference to GHQ with any possible result, it seemed better to have immediate decision at the price of half an hour. The change of H-hour to 0445 from 0515 will not, I hope, involve any change in Windeyer’s plan. I felt it should not to any real extent.

Replying two days later, Wootten wrote:–

The change of H-hour from 0515 to 0445 did not involve any change in plan. Windeyer was quite happy about it.

Opinions regarding another sudden development were exchanged in the same letters. Herring wrote:–

Since sitting down to write this, Hopkins9 has turned up with a message which at first shook me to my foundations, but which on further thought may prove more of a help than a hindrance. It appears that a close examination of the photos just to hand shows that there is a sand bar on [the southern] half of the beach which will preclude the landing of LSTs on that half, but will not interfere with the landing of any other craft. Result is that three LSTs only can be beached at one time and so it is now planned that wave six at H plus 80 should comprise three LSTs only, while the other LSTs will arrive on the beach at 2300 hours on D-day. ... The only problem will be the sorting of your vehicles so that those you need immediately go on the first 3 LSTs and the remainder will arrive when the beach is better able to receive them. I think really, on a frank reconsideration, this new plot that has been forced on the Navy is really better from your point of view. ... You know that I hate mucking you about, but you are one who can be trusted to deal with difficulties as they arise.

After a very early morning conference with Windeyer to discuss this unforeseen event, Wootten replied:–

Provided the second 3 LSTs are unloaded on the night of D-day at the far shore, that change in previous arrangements will not matter. Roughly, it means that one bty 25-pdrs, one Lt AA bty, about one-quarter engineer stores and the CCS with vehicles will be on the second wave of LSTs.

Plans for air and naval support were simple. Blamey decided on 19th September that preliminary air attacks on the Finschhafen area and Scarlet Beach in particular would only serve to warn the enemy of the landing. This decision, of course, did not prevent the bombing, in the few days remaining, of the airfields, supply dumps and reinforcement routes between Wewak and Finschhafen. In particular, American Liberators set about rendering Cape Gloucester unserviceable, while RAAF Kittyhawks attacked Gasmata and Bostons and Mitchells prepared to attack the enemy in the Finschhafen area after the landing.

Barbey only just had time to move the landing craft and destroyers up from Milne Bay and Buna to load the troops at Lae. While the bombers pounded Japanese installations, the fighters covered the naval movement to Lae and the loading. Naval support for the landing would consist of a preliminary bombardment from destroyers. The task force itself would be protected by an air umbrella of American and Australian planes. These would protect the convoy during daylight to and from the beach and during loading and unloading, and would also blockade the Finschhafen area. North of Scarlet Beach the aggressive American PT boats would operate in Vitiaz Strait to give warning of any approaching naval threat.

The concern of Barbey and his chief, Admiral Carpender, to have adequate air cover and avoid such losses as occurred at Lae, was indeed understandable when air photographs on 20th September showed 23 naval ships including 9 destroyers in Rabaul Harbour. One submarine was thought to be north of Vitiaz Strait and two or three in the Solomon Sea,

while one was reported to be moving along the south coast of New Britain. Barbey therefore included seven sub-chasers in his task force. Despite the battering which it was receiving, the Japanese Air Force was still capable of hitting back. Nine bombers and ten fighters attacked Nadzab on 20th September and Japanese reconnaissance planes daily flew over the Allied supply route from Buna to Lae.

Windeyer’s detailed orders were issued on the 20th. As laid down by I Corps, the objects of the landing were to deny the area to the enemy, gain a base from which future coastwise operations could be launched, provide a base for PT boats in Vitiaz Strait, and provide fighter strips. Windeyer stated his intention simply: “20 Bde will land on Scarlet Beach with a view to the capture of the area Finschhafen-Langemak Bay.” With each of the three battalions would be a battery of the 2/12th Field Regiment, a platoon of the 2/3rd Field Company, and a light advanced dressing station from the 2/8th Field Ambulance. The 10th LAA Battery and a company of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion would be responsible for defence of the beach-head area, while two platoons of the Papuan Infantry Battalion would be used to patrol the coastal track to Bonga, the inland track to Sattelberg, and assist Angau to collect natives.

Watching the improvised arrangements at Red Beach, Windeyer had come to the conclusion that an experienced combatant officer with a staff officer and some signals communications should command all troops in the beach-head area. Major Broadbent, the second-in-command of the 2/17th Battalion, was chosen as this Military Landing Officer.10

With the object of unloading the LSTs in two hours and a half from the time of beaching, the 2/23rd Battalion, the 2/48th Battalion, the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion and the Left Out of Battle group of the 20th Brigade were ordered to provide sufficient men to supply two companies, each of about 100 men, to each of the six LSTs. After unloading at Scarlet Beach the men would travel in the LSTs back to Buna and would then load and accompany the first re-supply mission about five days later. The 22nd Battalion was detailed for the coastal move from Hopoi to Finschhafen.

The 21st was a day of great activity for the 20th Brigade. Unfortunately there were not enough good aerial photographs of the landing area, and during the morning, while the rain pelted down incessantly, a continuous stream of visitors called at brigade headquarters to inspect the few air photographs. The lack of proper photographs was due to the fact that only one aircraft fitted with equipment essential for beach photographs was available.11

Maps were also in short supply. References in orders were made from the Finschhafen photomap. Just before the brigade embarked a supply of Sattelberg 1:25,000 (1st Edition) sheets arrived. As it was too late to

pack them only twenty copies could be accepted and most of these were given to the artillery.12 “Consequently,” wrote the diarist of the 20th Brigade, “the remainder of the brigade group did not have the benefit of this excellent map in the early stages, which were fought off the photomap.”

In the afternoon of 21st September the smaller and slower craft – 8 LCMs and 15 LCVs – left the Lae area for Scarlet Beach. At 3 p.m. loading of the LSTs began. Each LST loaded about 38 vehicles as well as the 200 unloading troops. By experience the 9th Division had proved that “bulk loading” – as far as possible in one-man loads – was more efficient than “vehicle loading”. During the loading the fighter cover was much in evidence. When nine Japanese bombers, escorted by fighters, approached “G” Beach and the ships riding at anchor they were driven off by Allied fighters and an impressive anti-aircraft display from the various guns on the ships and on land. Aboard the Reid the fighter detector officer recalled a homeward air patrol which shot down several of the Japanese aircraft. The LSTs were loaded smoothly and ahead of time. Soon after dark three of the LSTs, with a strong escort, left for Scarlet Beach while the other three moved south to disperse in the Morobe area until needed later that night.

The troops had moved to the ship assembly areas on the jungle fringe of “G” Beach at 4.30 p.m. Two hours earlier the LCIs and APDs, led by Barbey in his flagship, sailed from Buna, arriving at the embarkation beach at 7 p.m. The embarkation, which was arranged by the navy and Wootten’s staff, proceeded according to plan except that one LCI failed to arrive because of engine trouble. Lieut-Colonel Colvin, one of whose companies was to embark on the missing craft, was able to arrange for this company to be distributed on other craft.

Aboard the Conyngham Barbey was worried about a message from the coastwatchers that Japanese aircraft were coming over. For a while he wondered whether it would be better to “call it off” until next day. Supported by Hopkins, Windeyer urged that no change be made in the plan. The voyage proceeded. The convoy pulled out from Lae at 7.30 p.m. Soon after midnight Barbey overtook the earlier waves and the convoy steamed east and then north through the night to meet its destiny. Arrangements for the troops aboard the LCIs were more satisfactory than for the voyage preceding the Lae landings, while once again the arrangements for the troops aboard the APDs were excellent and cemented still further the good relations existing between the men of the 20th Brigade and the crews of the APDs. During the night enemy aircraft shadowed the convoy.

The target, Scarlet Beach, lay in a small indentation in the coast, making a well-defined bay with definite headlands. It was about 600 yards long and 30 to 40 feet wide with good firm sand which would take LSTs. At the northern end of the sandy beach was the mouth of the Song River

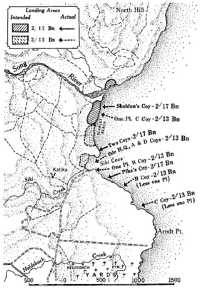

The landing at Scarlet Beach, 22nd September

and at the southern end a small headland and then a small cove into which Siki Creek flowed. South from Scarlet Beach to Finschhafen lay a narrow coastal strip varying from half a mile to 300 yards in width; to the west the mountainous and difficult country of the Kreutberg Range rose steeply. Creeks and rivers were fordable, but usually ran between deep banks and were not easy to cross, thus constituting good defensive positions for the enemy. Along the coast were coconut plantations overgrown with vegetation to a height between four and eight feet. As the convoy headed s north the troops in the APDs prepared for the landing.13 Reveille was at 2.45 a.m. Broadly, Windeyer’s plan was that two companies of the 2/17th Battalion would land on the right of the beach and two from the 2/13th on the left. Each of these companies had therefore embarked in one of the four which had been instructed to land their barges at definite places. Windeyer intended that the right company of the 2/17th should land as near as possible to the northern end of Scarlet Beach to enable it to capture quickly a dominating feature called North Hill on the northern headland; and that the left company of the 2/13th should land in Siki Cove so that it could, as speedily as possible, capture Arndt Point, the southern headland.

This time, as the craft carried the invaders northward towards Scarlet Beach, the troops could not see the green jungle fringe or the beach. All that could be seen by the assaulting troops as H-hour approached were the dim outlines of funnels and barges about to be lowered from the davits.

There was no comforting sight of neighbouring craft, nor was there any impression of the might of the invading force. There was a final burst of speed by the APDs and when, according to Conyngham’s radar, Scarlet Beach was abreast, the APDs trembled to a stop. “Lower barges”, “Get ready to land”, “Away the landing force”. This was by now a familiar routine for the men of the four assaulting companies – Captain Sheldon’s14 and Major Pike’s15 of the 2/17th and Captain Deschamps’16 and Major Handley’s17 of the 2/13th.

For eleven minutes before the landing five destroyers bombarded the shoreline from 5,000 yards, the flashes of the explosions lighting up the blackness of the beach and giving the barges from the APDs some idea of direction in the darkness. The destroyers were using red tracers which looked like giant fireflies. The bombardment probably had considerable effect on the Japanese, even though it did not cause many casualties. Under cover of it the barges sped for the shore. “It’s on again,” men muttered as the machine-guns on the barges raked the shore in reply to machine-gun fire from the shore. The enemy fire and the difficulty in the pre-dawn gloom of distinguishing between Scarlet Beach and Siki Cove caused some of the barges to veer to the left. “Generally,” reported Windeyer later, “the whole wave beached much to the left of the appointed places. Most of the assault troops were thus landed in Siki Cove or further left on the southern headland of the bay at Arndt Point.”18 Nor did they land in order for the barges of both assaulting battalions became hopelessly mixed in the darkness.

The experience of one of the 2/13th’s platoons, which should have landed near the centre of the line, illustrated the confusion. Number 4 barge was detailed to tow another which had broken down the night before and had defied the crew’s efforts to get it into working order. The speed of the two barges was thus reduced and soon they dropped behind, and after some indecision became hopelessly lost. Everyone stood up, straining their eyes and ears for signs of the remainder of the wave. It was no use; blackness hemmed the barges in on all sides. Then the explosions of the naval shells began to light the shore. “Put her straight in! Make for those shell bursts! Get her to the shore somehow. Anywhere will do!” These were the sentiments of the platoon commander as he directed the American coxswain. The bombardment died away and once again the two barges were left with only a dark shoreline to steer a course by. It was then that some of the barges which were landing closer to their planned landing places began raking the shoreline with their machine-guns and once again the lost barges had a bearing.

Closing in on the shore the two barges were hailed by the wave leader, who drew alongside and ordered the leading barge to slip its tow rope. Thus released it raced to the shore while the men in the disabled barge were transferred to the wave leader’s barge. On the leading barge someone suddenly shouted at the coxswain: “Look out! You’ll get us run down. Put her hard to the left!” The black bulk of an LCI, seeming enormous in the gloom, towered above the barge which had become mixed with the second wave just coming in. The coxswain shot the barge to the left and then straightened for the shore. The platoon’s troubles were not yet over for the keel bumped and scraped several times on a reef. The barge bounced off and then ended up with a splintering shudder off the rocky headland of Arndt Point, hundreds of yards south of the correct landing beach. The ramp was lowered gingerly lest the barge founder. Stumbling and swearing in the darkness the men clambered up the rocks. One or two fell into pot-holes and came up spluttering and swearing. Finally, the platoon made its way to the jungle fringe.

In their training the troops of the 9th Division had learnt what they were to do if landed on the wrong beach, as had been done at Gallipoli. They knew that wherever they landed their task was to wipe out the enemy posts in their vicinity, then reorganise and make for their correct objectives.

The four assaulting companies were landed not only on the wrong beaches but mixed with one another. Captain Sheldon’s company of the 2/17th on the extreme right, together with the anti-tank platoon, appeared less disorganised than the other three because it had landed generally in the Scarlet Beach-Song River area and was soon under control. The next company to the south was Major Pike’s of the 2/17th. Landing in the Siki Cove–Arndt Point area his troops became so badly mixed with those of the 2/13th that he decided that as he had no opposition the best course would be to move inland about 100 yards and wait for daylight. This sensible action enabled the two assaulting companies of the 2/13th on his left to get clear.

The right-hand company of the 2/13th Battalion (Captain Deschamps’) landed from Siki Cove to Arndt Point. The barge carrying Deschamps’ headquarters was first to land and for a considerable time he had no idea where his three platoons were. By good luck, however, these platoons, including the two which had been lost, landed more or less in the same place. The fourth company in the initial line-up (Major Handley’s) landed all over the place. One platoon (Lieutenant Huggett’s19) veered off to the right and landed near the mouth of the Song, while the others landed near Arndt Point.

Huggett’s platoon was the only one to experience serious opposition after the landing. It drew fire from machine-gun posts near the mouth of the Song. Engaging the enemy with grenades and small arms fire, Huggett’s men eventually silenced two enemy posts. They were aided by

Lieutenant Herman A. Koeln, an American amphibious scout who had been landed at the wrong spot and decided to remain and fight with Huggett. Another American amphibious scout, Lieutenant Edward K. Hammer, ran into a party of Japanese, shot a few and continued on. Both these scouts were handicapped by having to carry marking signs ten feet high – two long poles and a piece of red-painted canvas.20 When the 2/17th Battalion began to become organised in this area Huggett moved his platoon south along the beach to rejoin his company. On the way he passed several bands of 2/17th Battalion men moving north.

By landing too far south most of the wooden barges from the APDs escaped fire from enemy positions on Scarlet Beach. The mission of the assault wave, however, was the capture of Scarlet Beach and its immediate jungle fringe. This had not been captured when the second wave, consisting of LCIs and LCMs, headed for the shore. In this wave the men were ready behind the landing ramps, kneeling as though in prayer. Enemy fire, not neutralised by the assault waves, spat at the LCIs as they came in. This fire and the darkness caused them to veer to the left also and most of this wave beached in Siki Cove. One eye-witness in the second wave described his experiences thus:

We were the second wave this time, and we expected that the first wave of Diggers would have “done over” the Japanese before we hit the sand. But the first wave missed Scarlet Beach entirely in the darkness and ran into Siki Cove and on to coral farther south. Our wave, also of six or eight LCIs, ran into the cove, but our boat hit coral with a jarring, creaking crash on a small headland between Scarlet Beach and Siki. One gang-plank was immediately out of action, and we began jumping off the other. Odd sniping shots snapped out from the shore. ... To our left a machine-gun fired a stream of white tracers down on to the beach. ... Ahead and above us, on top of the headland about 100 feet away, a Japanese machine-gun opened fire with tracers. Its first burst went high into the air, the second into the water beside the boat. The third burst crashed over my head and hit two men behind me; I heard them cry out as I jumped on to the coral and splashed through a pool or two to the beach.21

Because of a sand bar at Siki Cove some of the LCIs dropped their ramps in deep water. Most men from these craft were soaked as they struggled to the shore. Some lost their footing, and, loaded as they were, they would have drowned but for helping hands. Two LCIs, having struck the bar, retracted and came in closer. Among the casualties on the beach and in the surf the stretcher bearers and medical orderlies were busy at their work. Soon after the event an eye-witness22 described the scene:

Abruptly our Sig Sgt ordered us to ground and down we went to the sands awash with the surf. Dimly I was aware of sea water washing over my boots and swirling round my chest. Near by someone groaned, and, glancing quickly to my

right, I saw the inert figure of a man, face towards the still visible stars, a stained hand resting on his chest. A little farther down from him lay another man gently rocking back and forth to the rhythmic beat of the surf. “Poor devils,” you think then “Thank God”, as a crawling figure looms up out of the lifting veil of darkness. A stretcher bearer! You shudder a little as he merely glances at the gently rocking one, for already he is in hands far greater than any mere human’s. Next moment he is by the side of one who is not beyond his aid.

To deal with the enemy fire from the beaches one of the LCIs poured heavy fire from its 20-mm into a machine-gun post. Although instructions had been given at Lae that the LCIs were not to fire, the sudden bursts from one seemed to release the fingers of the gunners of all the LCIs who were soon firing at the jungle fringe and behind the beach or at the tree tops. Although not in orders,23 this heavy firing may have helped to cause the Japanese to leave the beach defences. But had the assaulting troops and the troops in the second wave actually landed at Scarlet Beach, casualties would have been heavy among the Australians.

All this confusion “meant that Wave 3 (LCIs) were the first craft to land any large number of troops on Scarlet Beach proper”.24 The troops of this wave (brigade headquarters, headquarters of supporting arms and the reserve battalion-2/15th Battalion) thus landed under enemy fire, some of which was neutralised by point-blank fire from the LCIs. In this disorganisation timings had not been adhered to. The first wave was seven minutes late in landing; by the time the third wave landed it was half an hour behind schedule. Moving in slowly the LCI leader appeared hesitant when he heard the firing and when an enemy bomber flew over. Other LCIs which were taking their dressing from him began to lower their ramps well off shore. Some men jumped off into deep water and swam ashore. Once the guns of the third wave began to fire, however, determination revived and the third wave sped to the shore at the good speed necessary to beach an LCI. Even after most of the troops were ashore some of the LCIs continued firing and in futile anger some of the men bunched ashore beneath the fire yelled at the gunners to cease. Because of these delays the three LSTs were half an hour late in coming to the beach. Unfortunately Colonel Brockett’s men were an hour late due to unexpected navigational difficulties.25

Although the early waves were landed in such confusion, it did not take long to clear the jungle fringing the beaches. The invaders’ one idea had been to get their feet on dry land and “have a go at the Jap”. Most of the Japanese did not stay to fight in the face of the fire from the LCIs and the thrust from the beach, which soon became congested as

various platoons in the light of dawn used it as the quickest route to their correct positions.

At this stage much of the battalion commanders’ time was spent in finding just where their troops were and in directing platoons towards their companies. Colonel Simpson, sitting with bandaged head on a log near the edge of a kunai patch, warned his troops against snipers who were still exacting their toll.

By the time portions of brigade headquarters landed, in the third wave, there were about 300 to 400 troops near the south end of Scarlet Beach trying to find their units or to climb the cliff along a single track. When Windeyer and his brigade major, Wilson,26 arrived on an assault barge from Conyngham, Broadbent, aided by other officers, had the troops cutting their own tracks and preparing lanes for the clearance of stores. Air raid alarms, however, proved the most effective means of clearing the beaches quickly.

By 6.30 a.m., with the beach and jungle fringe cleared of all but dead Japanese, Windeyer had established his headquarters and was in telephone communication with each of his battalion commanders. As brigade headquarters went forward round the edge of a kunai patch about 200 yards in from the beach a Japanese threw a grenade which mortally wounded Corporal Appel27 and wounded Captain Maughan,28 the brigade Intelligence officer. The Japanese was soon killed with an Owen burst.

By 6 a.m. the APDs and LCIs were on their way back to Buna. Three hours and a half later the LSTs pulled out. Two were completely unloaded, but the unloading of the third was not quite finished. The men of the 2/23rd and 2/48th Battalions and 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion unloaded with a will, clearing an average of 50 tons of stores and 20 vehicles an hour; according to Barbey’s report, this was much faster than hitherto. From first light high and low fighter umbrellas were over the landing area and dealt effectively with enemy planes which bombed the beach soon after the LSTs pulled out, causing one casualty but no damage. Before the landing six PT boats from the Morobe base were stationed north of Fortification Point watching for surface and underwater craft, and during the landing four destroyers swept an area to the north.

On the right flank the 2/17th Battalion, after sorting itself out, proceeded towards its objectives. The first report which Simpson received, at 6.15 a.m., was from Lieutenant Gibb’s29 platoon from one of the reserve companies (Captain Dinning’s)30 which had landed in some sort of order on each side of the Siki headland and had advanced inland with one platoon on each side of the head. Gibb’s platoon on the left had met a

machine-gun post which Private Spratt31 knocked out before most of his platoon had left the LCI and before he was mortally wounded. “Doing over MG post,” reported Dinning. Half an hour later Simpson learnt that the right-hand platoon had killed seven Japanese withdrawing from the south end of Scarlet Beach. Dinning then immediately departed for his objective 400 yards up the Song River.

At this time Simpson, whose headquarters was established half way between Katika and the Song, had little idea where his other three companies were. He hoped that Sheldon’s company, accompanied by the Papuan infantrymen, would be on North Hill. The second rear company – Lieutenant Main’s32 – also landed near the Siki headland at the same time as Dinning’s. After killing two Japanese who waded into the water in a puny effort to attack the LCI, Main collected his company and advanced inland a short distance to a garden patch about 100 yards west of the coastal track. He then patrolled to the north and by 9 a.m. his company joined Dinning’s on the Song River. Pike’s company reported at 6.45 a.m. that it was about to pass west through Katika, controlling the outlet to Sattelberg, to the high ground beyond, having already made contact with troops from the other two battalions. Even though he did not know the whereabouts of Sheldon’s company, Simpson felt confident enough to report at 6.50 a.m., “Progress satisfactory – little opposition.”

By 7.30 a.m. Simpson received his first intimation that the Japanese had stayed to fight, when Pike reported opposition just outside Katika. A quarter of an hour later he heard from Sheldon: “Am across river – present strength 51 – trying to locate 10 P1 who landed north of Song River-2 P1 [of 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion] with us – moving to North Hill – PIB have passed on to Bonga.” Thus, about two hours and a half after the landing, Simpson had a fair idea of the general location of his companies – one across the Song moving to North Hill, two on the Song or moving towards it, and one in the Katika area.

On the left flank Lieut-Colonel Colvin’s experiences were similar to those of Simpson. When the second two companies of the 2/13th Battalion landed they were unable to find the first two. Colvin ordered the second companies – Captain Cooper’s33 and Captain Cribb’s34 – into the timber fringing the beach. A few remaining pill-boxes were cleared and a prisoner was captured. The two companies then advanced to the coastal track with battalion headquarters close behind. As efforts to contact Deschamps and Handley by walkie-talkie were unsuccessful, Colvin sent his Intelligence officer, Lieutenant Murray,35 down the track to the south to look for

the forward companies. About 150 yards down the track he met Captain Snell’s36 company of the 2/15th, who informed him that elements of Deschamps’ company had moved on towards Siki Creek, and warned that snipers were still in the area.

It was just on daylight (6.20) when Colvin got through to Deschamps on the walkie-talkie. Not knowing where his other two platoons were, Deschamps and one platoon (Lieutenant Appleton37) had headed north from his landing place and had crossed Siki Creek about 400 yards from its mouth. Passing through Snell’s company he found the Katika Track and turned south to seek the junction of the track and the creek. After firing at some fleeing Japanese in the shadows Deschamps’ company approached Siki Creek again. About 100 yards down the track two Japanese appeared and both were shot by the leading scout, Private O’Malley.38 Another 50 yards farther on he shot one more. At the creek Appleton went forward to investigate a crossing. Two Japanese rushed out from under the creek bank and in the exchange of shots Appleton was fatally wounded. Seeing his platoon commander’s predicament, Private Howlett39 jumped into the creek and shot both Japanese with his rifle.

Deschamps then ordered the platoon, now under Sergeant Crawford’s40 command, to cross the creek. It did so and took up a position on the far side. At this stage Murray, guided by the noise of battle, found Deschamps, and, to the best of his ability, told him what the rest of the battalion was doing. Hearing movement on the left, Crawford’s men were alert, but the noise materialised as Lieutenant Hall’s41 platoon came up along the south side of Siki Creek. Soon afterwards the third missing platoon – Lieutenant Angel’s42 – followed from the same area. The two platoon commanders, who had met no opposition, informed Deschamps and Colvin that Handley’s missing company had landed to their south. Deschamps placed his two platoons on the north bank of Siki Creek, one on each side of the Katika Track. The company had thus reached its objective and there it stayed all day.

Apart from Huggett’s platoon, the remainder of Handley’s company had landed on the coral cliffs between Siki Cove and Arndt Point. With Lieutenant Thomson’s43 platoon, Handley’s headquarters clambered up the cliffs and set off for the south. Handley reached Heldsbach Creek

without opposition, but was unable to get through on the walkie-talkie to battalion or brigade until 11.30 a.m.

Lieutenant Mair’s44 platoon, which had landed south of Handley, ran into a Japanese gun position, where five Japanese huddled behind logs were killed by the platoon, which then led the march south. Mair arrived without further incident at Launch Jetty at 8.50 a.m. and, using his initiative, sent a section to the north end of the airstrip where no enemy were seen. About the same time Handley’s second-in-command, Captain Fletcher,45 with one man, advanced south looking for the rest of the battalion (Handley was still out of contact) and reconnoitred the Heldsbach Plantation ahead of the southward advance of Cooper’s company.

Meanwhile at 6.30 a.m. Cribb’s company on the northern flank of the 2/13th was ordered to capture Zag, where the track to Jivevaneng zigzagged. Cribb was informed that the stream on his right was Siki Creek, and decided to advance up the creek and across to Zag. The stream was not Siki Creek but another little one flowing from just north of Katika. About 150 yards after starting along the narrow track following the creek Lieutenant Birmingham’s46 platoon had three men killed, and three wounded, one mortally, when a Japanese threw a well-directed grenade. About 7 a.m., after advancing along the creek’s left bank for 60 yards, the leading scouts were fired on and the company soon lost another two men killed and one wounded. Cribb was unable to attack immediately because some of Pike’s men were on his left flank and close to the line of fire.

Two hours and a half after the landing, Colvin knew where three of his companies were – Cooper’s advancing on Heldsbach, Deschamps’ guarding the track where it crossed Siki Creek, and Cribb’s under fire 200 yards north of Katika. The fourth company (Handley’s) was missing, although Huggett’s platoon had joined battalion headquarters.

The reserve battalion of the 20th Brigade – Lieut-Colonel Grace’s 2/15th – landed in much the same sort of disorder as the other two battalions. Three hours after the landing, Grace was not sure of the whereabouts of two of his companies – Captain Christie’s47 and Captain Snell’s. The other two companies – Captain Angus’48 and Major Newcomb’s – were with battalion headquarters, concentrated in the area between Katika and Scarlet Beach. Snell meanwhile pushed on to the Katika Track where he met Pike of the 2/17th preparing to attack Katika. Christie’s company was also in the general area east of Katika.

Pike’s men were the first to attack Katika. After reaching the main track, Pike saw some high ground to the west, and leaving the track he

advanced for 200 yards. The leading scout came to a clearing ahead with two dilapidated huts. This was Katika, but at the time Pike’s doubts as to what it was were shared by all those with him. Pike ordered the forward platoon – Lieutenant Waterhouse’s49 – to advance, skirting the clearing. When it reached a deep re-entrant leading off from the clearing the company was stretched out in a half moon behind it round the clearing with Pike in communication with his platoon commanders by

walkie-talkie. Lieutenant McLeod,50 whose platoon was following company headquarters, suddenly reported seeing movement in the clearing and sent out a section to investigate.

Firing simultaneously broke out from the direction of Waterhouse’s position 50 yards ahead and from McLeod’s section near the huts. After McLeod reported killing four and losing four wounded, Pike ordered him to attack the huts frontally and Waterhouse to reconnoitre a route round the enemy, who were apparently on the high ground immediately ahead. Before McLeod moved round the huts into the open Pike sent his third platoon – Lieutenant Craik’s51 – round to the left to pin the enemy with fire. As these two platoons were moving into position intense fire came from the enemy defences along a 100-yard front on the high ground immediately to the west. The Japanese then attempted to encircle Pike’s left flank, but fire from Craik’s men killed two of them and drove the remainder back. At this stage Snell, who had picked up the gist of what was happening by listening with his walkie-talkie to Pike’s orders, called Pike and told him that he would watch the left flank. Snell moved into the positions occupied by McLeod’s and Craik’s platoons and farther left.

Waterhouse then reported that the ground which the enemy occupied was high and that the approach was through thick undergrowth interlaced with vines. Snipers were firing from the trees, but so far there were no casualties. Seeking a better line of approach, Waterhouse moved farther right and then led the attack up the slope. He reached within eight yards of the enemy position before he was mortally wounded. The platoon withdrew into a re-entrant and temporarily lost contact with the company commander because the walkie-talkie was still with Waterhouse. When the new platoon commander, Sergeant Cunningham,52 regained contact with Pike he stated that Cribb’s men were in the re-entrant to his right and were going to attack.

The three battalion commanders, each with a company in the Katika area, began to wonder what was happening. The signal from Pike to Simpson was laconic – “Struck opposition at 633682, extent unknown – dealing with it.” At 10.53 a.m. Colvin signalled Simpson about the three companies in the area – “They seem to be in trouble,” he concluded. The next signal from Pike came to Simpson soon after 11 a.m. “I am in Katika village. On east of Katika and slightly north. Cribb 2/13 Battalion west of Katika – Snell 2/15 north and east of village. Waterhouse’s platoon west of village. Cribb took over and doing a show.”

When the companies of the 2/17th and 2/13th, led by Pike and Cribb respectively, found themselves close against one another, Cribb asked Pike’s leading section to pull back so that he could bombard the enemy position with grenades and 2-inch mortars. Cribb then decided to attack the strong enemy defences on the high ground. With Birmingham’s platoon

giving supporting fire from the left and Lieutenant MacDougal’s53 watching what Cribb called “the back door”, Lieutenant Pope’s54 platoon prepared to attack. Before the attack fifteen mortar bombs were sent over and a Vickers gun was set up on the left flank.

At 10.55 a.m. Cribb’s attack went in. Stumbling over thick secondary growth and pushing through kunai, Pope’s men advanced on the Japanese positions. The firing was heavy from both sides, but the odds were not even. Although he advanced to within grenade-throwing range, Pope, who was now wounded but remaining on duty, found what many another commander had found, that it was usually futile to attack frontally against strong enemy defences. With two men killed and ten wounded, including himself, he “went to ground”, but held on until called back by Cribb.

During the attack Private Dutton55 carried out three of the wounded men on his back. Other casualties were sent back along the signal wire, but it was very difficult to remove all casualties under fire. Colvin told Cribb that he could have mortar support if he could give a reasonably accurate map reference. Under cover of fifteen 3-inch mortar bombs all the dead and wounded were removed, except for one dead man who was brought out later. Strangely, there was no fire from the enemy during this period Cribb’s company had suffered 28 casualties including 8 dead.

By midday Windeyer decided that no further advance would take place towards Finschhafen until the beach-head was stabilised. Battalions would mop up stragglers and snipers within their areas, and the 2/15th, which had concentrated as brigade reserve east of Katika, would capture that village and destroy the enemy as soon as possible.

The efforts of Pike’s and Cribb’s men, although unsuccessful in capturing the high ground west of Katika, were nevertheless sufficient to cause the enemy to doubt his ability to withstand another attack. Thus when Snell’s and Christie’s companies attacked at 3.15 p.m. after a bombardment by 3-inch mortars, they found the strong position deserted and eight corpses lying there. No more opposition was encountered on the day of the landing, and by last light the battalions had sorted themselves out and were on their objectives. On the northern flank a platoon of the Papuan Infantry reported Bonga deserted. The 2/17th Battalion was guarding the northern sector with Sheldon’s company on North Hill, Pike’s on the high ground south of the Song, and the remainder of the battalion half way between Scarlet Beach and this high ground. In the southern sector the 2/13th Battalion had driven rapidly south after the clearing of Katika; Cooper’s company having taken the wrong turning was at Tareko, Handley’s at Launch Jetty with a patrol on the Quoja River, and the remainder of the battalion in the Heldsbach area. Brigade headquarters was in a hollow just west of Scarlet Beach.

The Papuan company’s tasks were to get platoons astride the Bonga and Sattelberg Tracks, report movement, harass the enemy and assist Angau to collect natives. The two Papuan platoons available (Numbers 9 and 10)-101 men – had shared in the confusion of the landing. Landing on the right 10 Platoon pushed inland behind the enemy posts on the beach in an attempt to bring down cross-fire on the defenders. In doing so the Papuans were the first troops to get behind the enemy, but they came under fire from both the enemy and the Allies and suffered seven casualties. The other platoon and company headquarters were on an LCI in the third wave. When the gangway jammed and broke Captain Luetchford56 led his troops over the side and jumped into deep water. Badly wounded, Luetchford was helped ashore but on arrival at the medical dressing station he was dead. By dusk the two platoons had done valuable reconnaissance work. No. 10 Platoon, after reporting Bonga deserted, camped with Sheldon’s company on North Hill and 9 Platoon was with Cooper’s company at Tareko.

Two batteries of the 2/12th Field Regiment landed from the LSTs in the morning and were shelling Finschhafen by last light. The third battery arrived when the other three LSTs came to Scarlet Beach half an hour before midnight on the 22nd. The whole regiment (735 men) was then ashore. Major Pagan’s57 2/4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment (less one battery)-489 men – had Bofors guns in action by 7 a.m. and all its guns in position by 9.30 a.m. At 10 a.m. a gun of the 10th LAA Battery was bombed at the north end of the beach and five men were wounded, one fatally.

Judging from previous experience the sappers would have one of the hardest tasks in making roads and bridges and clearing obstacles. Specifically, the 270 men of Major Moulds’58 2/3rd Field Company and the detachment of the 2/1st Mechanical Equipment Company were to make a crossing over the Song, a bridge over the Mape, and “trs and brs in sp of the op [tracks and bridges in support of the operation] and the maintenance thereof”. Moulds also had for support Major Siekmann’s59 company of the 2/3rd Pioneer Battalion. Part of the headquarters of the 2/3rd Field Company had an exciting period when they found themselves ahead of the leading infantry. This small party, led by Captain Eastick,60 shot a Japanese in the foot and captured him. After sorting themselves out sappers and pioneers began work on beach exits, tracks and dumps.

On the beach itself, Major Broadbent’s task was to coordinate the defence of the beach, the movement of stores, the development of the beach-head, the requirements of small craft, and the control of traffic.

Broadbent, quick, energetic and full of initiative, proved an excellent choice, and in the succeeding days the force owed much to his drive and flair for improvisation. Broadbent carried out his tasks in conjunction with Pagan of the 2/4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Brockett of the 532nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, and Captain Nicholas,61 whose company of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion provided 12 Vickers guns for beach defence.

The positions occupied at last light by all the units and sub-units of the 20th Brigade group were those actually planned by Windeyer, except that Cooper’s company of the 2/13th should have been astride the Sattelberg Road near Zag instead of at Tareko. The fact that these troops had reached their first day’s objectives despite the confusion of the landing said much for their training, determination and leadership.

By midday Windeyer had been forced to ground the bulldozers which were severing the telephone lines to his forward troops at a time when he was trying hard to follow the fight. Despite this temporary lull in their major activities, the sappers by dusk had bridged Siki Creek and constructed a road from the south end of Scarlet Beach to link with the coastal road in Heldsbach Plantation. By 11 a.m. on the 22nd Windeyer’s adviser on native affairs, Lieut-Colonel Allan,62 appreciating the labour difficulties, brought in the luluai of Tareko and sent out messages through him to tell the “kanakas” to come in and work. In Allan the brigade commander had the support of an officer not only widely known and respected throughout New Guinea but one who had served with the brigade in its Middle East campaigns both as a regimental officer and as its brigade major.

At 10.30 a.m. on the 22nd a grave administrative deficiency was discovered: very little 9-mm ammunition for the brigade’s main close-quarter weapon – the Owen gun – had been landed. About five-sixths of the 9-mm ammunition loaded at Lae had apparently remained on the third LST which had not been fully unloaded that morning, though Admiral Barbey’s report stated buoyantly that the unloading was “virtually complete”. The battalions were immediately warned to conserve their Owen gun ammunition – a difficult task for the companies preparing to assault Katika. At the same time Windeyer authorised an “emergency ops” signal to the 9th Division repeated to I Corps asking for an air dropping of 9-mm ammunition.

This signal bearing as it did the highest franking produced speedy results. Dropping was arranged for after dark on the 22nd. The dropping area was a kunai patch near brigade headquarters and instructions were to illuminate the area. As they had no other means of illuminating it, the brigade staff asked all who possibly could to lend their torches. At 7.15 p.m. the men of brigade headquarters stood in a circle round the kunai

patch shining their torches, while 115,000 rounds of 9-mm ammunition were dropped; 112,000 rounds were recovered and the situation was saved. It was a fine achievement on the part of the RAAF Boomerang crews and Captain Garnsey,63 the Air Liaison officer.

While the capture of Scarlet Beach was being consolidated on 22nd September, Barbey’s convoy was steering south from the landing beach. About noon the destroyer Reid, again acting as fighter controller, began to chart the approach of a formidable air force from New Britain and within about 70 miles of the convoy. Surprised by the landing at Scarlet Beach, the Japanese only now sent 20 to 30 bombers and 30 to 40 fighters from Rabaul. Off Finschhafen they swerved South-east to attack the retiring convoy. But three American fighter squadrons were then patrolling the Lae–Finschhafen area as an air umbrella and were due soon for relief by other squadrons which were now warming up. The result was that five squadrons were ready above the convoy when the Japanese flew into the trap.

The American fighters claimed they shot down 10 bombers and 29 fighters for the loss of three Lightnings. Anti-aircraft fire from the destroyers, the landing craft and a tug also “splashed” nine out of ten torpedo planes which swept in too low for the radar to detect them. There were no losses among the ships. “Actually this little action helped to dispel an old South-West Pacific bugaboo, the fear of land-based air attack which had long kept ships out of the Solomon and Bismarck Seas.”64

The three LSTs which had been unable to participate in the morning landing because of the discovery of a sand bar in Scarlet Beach, sailed from Morobe at 6 p.m. with the remainder of the 20th Brigade’s units and stores and the unloading parties. They began unloading at 11.30, and by 4 a.m. on the 23rd were empty and steering south. While patrolling off Scarlet Beach about midnight the destroyers guarding the LSTs sank three barges full of Japanese sailing north. American naval records state that on 22nd September Barbey’s force landed on Scarlet Beach: 5,300 troops, 180 vehicles, 32 guns and 850 tons of stores comprising 15 days’ rations and 12 days’ ammunition.

Except that a lone Japanese walked into Sergeant Crawford’s platoon of the 2/13th on the south bank of Siki Creek and was promptly shot, the night was uneventful. Windeyer’s orders for the next day were: “20 Bde will continue advance on Finschhafen.” The 2/15th Battalion would lead the advance to the Bumi River; the 2/13th would assemble in the Heldsbach Plantation-Launch Jetty area, ready to move at 30 minutes’ notice. Thus the brigade was geared for an advance to the south, but Windeyer could not neglect possible threats from the north or west, and his orders were to be ready for Sattelberg after Finschhafen. General Wootten had told him before he left Lae that he should get at least a company on to Sattelberg as soon as possible. At the time neither realised

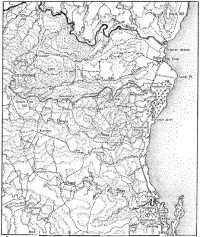

Hopoi to Scarlet Beach coastline

how inaccessible Sattelberg was and both thought of its occupation merely as a method of guarding the open right flank of the advance.

From prisoners and documents, captured on the first day, Windeyer learnt that an enemy force of 300 to 400 had been holding the Scarlet Beach-Katika area at the landing. These Japanese defenders had killed 20 Australians, including 3 officers, and wounded 65; 9 were missing. The Japanese defenders were companies from the 80th and 238th Regiments. The survivors had withdrawn along the Katika Track towards Sattelberg.

A captured map showed troops of the 80th Regiment east of the Mongi River. Soon after the Australian landing east of Lae the Japanese had sent this force of about three companies together with two 75-mm guns to the mouth of the Mongi to resist an anticipated drive by the Australians from Hopoi to Finschhafen. Towards them was moving Lieut-Colonel O’Connor’s65 22nd Battalion which had departed from Blue Beach near Hopoi at 6 a.m. on 22nd September, and by last light reached Wideru without opposition after a rough and slippery march.

At 8 a.m. on the 23rd, the 2/15th began its advance along the coastal track, with Major Newcomb’s company in the lead. Three hours and a half later the leading platoon approached the Bumi near its mouth. The river appeared easily fordable. As the leading scout neared Kamloa at 12.40 p.m., however, he saw two Japanese sitting under a hibiscus. He fired but missed, whereupon the two Japanese fired their rifles into the air, obviously as signals, and disappeared. Soon after 1 p.m. the leading

section under Corporal Tart66 advanced through the undergrowth to the cover near the river bank. Walking on to the bank to survey the crossing, Tart was shot dead. Heavy fire came from the south bank, where the Japanese had strongly fortified and wired positions, as Corporal Cousens’67 section covered the extrication of Tart’s men. When bringing in one of the wounded men, Cousens himself was wounded.

Colonel Grace was moving with the forward company. He had a quick word with Windeyer by telephone, and promptly put into operation an alternative plan. Windeyer had previously agreed with Grace that, if heavy opposition were met along the flat, a detached column should swing off the coastal track and continue the advance along the ridges to the west. Thus Grace left two companies at the north bank of the Bumi near Kamloa while Major Suthers68 led Christie’s and Snell’s companies with some Pioneers, stretcher bearers and mortar men into the hills. Lieutenant Shrapnel69 brought up six 3-inch mortars in support of the companies at the Bumi crossing, established an observation post overlooking Salankaua Plantation and, using his mortars as a battery, pounded the plantation area.

Leaving the battalion at 4 p.m. this force hacked its way up into the foothills of the Kreutberg Range. This was the first time that any unit of the 9th Division, apart from the 2/24th Battalion and individual companies, had done any hill-climbing on operations in New Guinea, and it was a tough initiation. There was no track and no water, and the force had to cut its way for about 800 yards through dense creeper and jungle along the flat and then up a slope so steep that any man carrying a heavy load had to have it passed up to him. Several tin hats clattered down the hillside and the stretcher bearers decided to leave all except two stretchers half way up. By 5.30 p.m. the force reached the crest of the ridge and, after regaining its breath, advanced south along the crest. An hour later, just after last light, the companies were established on the forward slopes of the spur at a spot later known as McKeddie’s OP.70

At midday on the 23rd Windeyer had ordered the 2/13th to follow the 2/15th and camp between the Quoja and the Bumi. When the 2/15th met opposition at the mouth of the Bumi, Colvin was ordered to follow Suthers, who would secure a bridgehead over the Bumi through which the 2/13th would pass and capture Finschhafen. As it was late when these orders were received and one company was protecting the guns and brigade headquarters at Launch Jetty, Colvin asked for permission to delay until early next morning and Windeyer agreed.

While the 23rd Battery was moving to the Finschhafen airstrip area there was some intermittent enemy shelling from 70-mm guns in

Finschhafen. In the late afternoon enemy aircraft bombed Scarlet Beach and destroyed 500 cases of ammunition belonging to the Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment. During the night it rained heavily and the Australians on the coast heard much barge movement off Finschhafen. Harassing fire by the Australian artillery soon caused the noises to cease.

At first light on the 23rd the 22nd Battalion had resumed its advance along the coast from Wideru. By 8 a.m. the first signs of Japanese occupation, all old, were seen. Soon afterwards the leading company saw smoke ahead, and natives reported that the Japanese had slept on the previous night at Buiengim. At 1.35 p.m. Captain Martin’s71 company approached Bua where the leading troops had a sharp skirmish with a Japanese outpost which withdrew. By 4 p.m. a section of Australians seized a steep rise where the track passed through a deep cutting approximately 250 yards east of Bua. Just after dark this section was fired on and several shells from a mountain gun were fired over the main Australian positions.

Reveille for the 2/13th Battalion on the 24th was at 4.15 a.m. and an hour later the battalion was slipping and staggering up the foothills in the wake of the 2/15th, following its signal wire. At 7.30 a.m. Colvin tapped the wire and informed Suthers of his progress. Now that the 2/13th was close behind, the 2/15th moved off for the river. Progress was still slow and by 8.15 a.m. when the men of the 2/13th lay panting on the top of the ridge Suthers was still about 350 yards from the Bumi. At 10 a.m. the leading company reached the river and found an unoccupied enemy position on the south bank of the river which was 15 to 20 yards wide. Barbed wire on the opposite side of the river, however, was an ominous sign. Half an hour later Lieutenant Rogers’72 platoon fired on two Japanese seen on the south side. Deciding that it would be foolish to attempt a crossing at that particular spot, Suthers with Captain Christie, Lieutenant Harpham,73 and one platoon, went upstream about 150 yards and found a more suitable place. Christie went forward to reconnoitre this crossing and was hit by a Japanese sniper firing from the north bank. The sniper was actually seen for an instant recrossing the creek. Harpham went forward to see if Christie was dead – he was – and, while in the open, was sniped and himself killed.

Suthers now ordered Captain Snell to cross the river and seize a bridgehead on the opposite bank. The artillery shelled the kunai patch on the south bank overlooking the river about 12.30 p.m. As the company formed up for the crossing enemy fire inflicted three casualties. A slight delay ensued while a section of machine-guns got into position. They were ready at 1.15 p.m. and a quarter of an hour later Snell’s men advanced again. The stream was up to the men’s waists, but only one man was killed

during the crossing; most of the enemy’s strength appeared to be farther downstream.

Although stray bullets were flying, one going through the seat of Snell’s pants, the company scrambled up a very steep hill without serious opposition to a track junction on the left and stopped there. The bridgehead was thus established, and with the other company, now led by Captain Stuart,74 guarding the crossing from the south bank, the task of the 2/13th was to cross and continue the advance. Major Handley’s company had little difficulty in crossing the river at the bridgehead, despite harassing fire from snipers and machine-guns concealed in the undergrowth farther downstream, and by last light had linked with Snell’s company higher up.

As there had been no enemy activity in the Scarlet Beach sector, two companies of the 2/17th were moved south along the coast as brigade reserve. This left in the Scarlet Beach area only two companies of the 2/17th along the Katika and Sattelberg Tracks, one company of the 2/3rd Pioneer Battalion, the 10th LAA Battery with six guns, one company of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion, and engineers and others. Brigadier Windeyer knew well that, with such a thin scattering of troops, Scarlet Beach was vulnerable. As yet, however, there was no sign of any threat from north or west, and, as his objective was Finschhafen, Windeyer felt it imperative to have a reserve within close call. That there was no immediate cause for anxiety about his exposed right flank seemed evident when a signal from Lieutenant Main of the 2/17th Battalion on the 24th stated: “Coy less one pl now approx 3 miles along main track and proceeding to Sattelberg. Patrol PIB moving ahead of coy.”

Just before Handley’s company crossed the Bumi, Colvin suggested that, as evacuation and resupply would be very difficult along the route traversed by the 2/13th and 2/15th, some attempt should be made to cut a track around the foothills to the bridgehead positions. The difficulty was underlined when the rain began and men floundered and slipped carrying supplies and ammunition up and stretchers down. Windeyer therefore directed that a jeep track should be cut through the jungle from the coastal track just north of Kamloa to the bridgehead. A platoon from the 2/3rd Pioneers and men from the 2/17th and the reserve companies of the 2/13th and 2/15th were employed for carrying along the rough and arduous route while the track was being cut.

Japanese aircraft were over the Scarlet Beach area from early in the morning while Allied planes were attacking airfields on New Britain. At 12.30 p.m. on the 24th the Japanese air force enjoyed unusual success when 12 bombers and over 20 escorting fighters attacked the Australian gun positions at the north end of the airstrip; the guns had been shelling enemy positions in the Kakakog and Salankaua Plantation areas. Although the 60-odd bombs which were dropped did not damage the guns, 18 casualties (including Captain Nelligan75 killed and one man who later

died of wounds) were inflicted on the gunners, and the 2/3rd Field Company lost 14 killed and 19 wounded. The air liaison party from the Fifth

Air Force lost all its equipment and its commander, Captain Ferrel, was killed. For once the Japanese radio reports about the damage and casualties inflicted by their air force were only too true.

Looking at the photo-map of the Finschhafen area, Windeyer estimated that his forward troops were on the high ground about a quarter of a mile west of the MT ford, while the enemy were entrenched in the Salankaua Plantation and the foothills to the west. For the 25th he ordered the securing of the Kreutberg Range with the 2/13th passing through the 2/15th’s bridgehead and establishing itself, with two days’ rations and ammunition, overlooking the main enemy positions. The companies of the 2/15th at Kamloa would stage a mock attack.

Along the south coast of the Huon Peninsula the advance of the 22nd Battalion continued on the 24th. North of Bua a large deserted Japanese camp containing equipment and documents was found and a large dump of ammunition, petrol and tools. By 11.15 a.m. the forward troops arrived at Tamigudu near Cape Gerhards where they saw signs that a gun had been dragged along. At noon an abandoned ammunition dump for a 75-mm gun was found near Oligadu. At 1.40 p.m. the battalion reached the Mongi, thus achieving its original objective, and dug in along the river and on its islands. During this process one Japanese was killed.

A patrol led across the river by Sergeant Hogan76 was overdue at nightfall when heavy fire came from the direction taken by the patrol. At the same time the enemy suddenly opened fire from the east bank of the river. Rifles, sub-machine-guns, machine-guns and mortars mingled with about 70 rounds from a 75-mm gun. It was as though the Japanese, realising the hopelessness of their position, were determined to fire off as much ammunition as possible before it fell into Australian hands. During this half-hour bombardment one man was killed and one wounded.

The enemy air force was again active on 25th September. Between 4.45 a.m. and 7.30 a.m. there were three raids and again the Allies suffered relatively heavy casualties-8 killed and 40 wounded – mainly anti-aircraft and administrative troops. There was a further raid at 5.15 p.m. which was more in accordance with the usual pattern – no casualties or damage. The Allied air force, which had been concentrating mainly on near-by Japanese airfields in New Guinea and New Britain, retaliated at 9.35 a.m. when about 20 Bostons and Vultees bombed and dive-bombed Japanese positions in the Finschhafen area.

Some of the hardest worked troops in Windeyer’s force at this time were the men of Lieut-Colonel Outridge’s77 2/8th Field Ambulance. When the three LSTs of Wave 7 departed from Scarlet Beach in the early hours of 23rd September only the walking wounded were able to get aboard in time. The more seriously wounded from the first day as well

as those wounded subsequently by enemy land and air operations were unable to receive any attention other than that provided by the 2/8th Field Ambulance and Major Gayton’s78 section of the 2/3rd Casualty Clearing Station. As there was no re-supply mission for ten days the wounded could not be evacuated and normal medical installations became holding centres. The recovery of fracture cases was seriously prejudiced by the lack of proper facilities for treatment. The third LST, which had not completed unloading on the morning of the landing, sailed with the lighting plant for the MDS and CCS operating theatres still on board, and not enough stretchers had been landed. It was no part of the brigade or divisional commander’s job to clear this MDS It was the responsibility of the higher headquarters to provide the necessary ships. Within the brigade, medical arrangements were as good as could be expected under the circumstances, but the higher planning was proving faulty in this respect.

In addition, as a result of the speed with which the operation had been undertaken, there were few canteen goods, canned heat, razor blades and hospital comforts. The main shortages were in tobacco, cigarettes, matches and chocolate. Only three ounces of tobacco a man were available during the battle for Finschhafen and other canteen issues were limited. One of the most serious deficiencies was canned heat. This had been developed so that men in forward areas, where the lighting of fires would disclose their positions to the enemy, could still have a cup of tea. Only 1,152 tins were landed and some men in the areas where fires could not be lit went for three days without a hot drink.

In the Bumi sector the 25th was spent in patrolling, consolidating the bridgehead, bringing up supplies and completing the jeep track. A patrol led by Lieutenant Mair of the 2/13th Battalion was sent out soon after first light to deal with a troublesome enemy mortar to the east. At 8.45 a.m., after following an old and indefinite track down into a very rough gully, Mair found a Japanese strongpost 20 feet above him. He lost two killed and four wounded, and with great difficulty extricated his wounded. It seemed that this enemy position, containing bunkers and foxholes and barbed wire from the river up, was the left flank of enemy defences opposing the crossing at the ford. It had also inflicted most of the casualties during the crossing.

Snell’s and Handley’s companies found themselves on a razor-backed ridge running in a South-west direction towards the main Kreutberg Range. On top the ridge was bamboo clad and varied in width between 5 and 15 yards. On each side steep slopes fell into thick gullies. In case the Japanese should push up from the east, Handley, on orders from Colvin, sent Angel’s platoon west along the south bank to reconnoitre for another battalion crossing. As the country consisted of a series of steep razor-backs running down to the river there seemed little point in establishing another

crossing, particularly as Suthers reported in the late morning that men could now cross the river without opposition.