Chapter 18: Easy Street and the Sattelberg Road

FINSCHHAFEN had been captured on 2nd October, but Brigadier Windeyer realised that “to secure the gains it would be necessary to continue the offensive and to get possession of Sattelberg as soon as possible”.1 Even before 30th September, when the company of the 2/17th Battalion had been relieved at Jivevaneng by Captain Grant’s company of the 2/43rd, it had become obvious that one company could just hold its own there, and by dusk on 30th September only two of Grant’s platoons bad reached Jivevaneng. Grant had no time to work out a fire plan before the enemy were heard moving in the undergrowth. At this time it was Colonel Joshua’s intention that Grant’s third platoon and a second company should reinforce Jivevaneng next morning.

The enemy closing round Jivevaneng were from Lieut-Colonel Takagi’s III/80th Battalion, which had attacked unsuccessfully down the Sattelberg Road on 26th September. Four days later Colonel Sadahiko Miyake, the commander of the 80th Regiment, noted that “it seems the enemy attacking our regiment on the Finschhafen naval front turned towards Heldsbach at about noon on the 27th”. He then attached some of his troops to the Finschhafen naval force and ordered the III/80th Battalion to “continue its present duties”, which accounted for the pressure on. Jivevaneng.

At 6.15 a.m. on 1st October the enemy cut the telephone line between Joshua and his forward company, and much firing was heard from the direction of Jivevaneng. Grant’s men were alert when the first attack came, from the North-east, and, despite the yells of the Japanese “cheer-leader”, the attack was driven off. The Australians retaliated with 2-inch and 3-inch

mortar bombs, while the relieving force was advancing cautiously up the Sattelberg Road. At 9.20 a.m. when about a quarter of a mile from its objective the leading platoon was fired on and its commander (Lieutenant Dost2) killed. Lieutenant Richardson3 from the next platoon went forward to investigate and was wounded. By this time Grant’s men had beaten off two more attacks, both from the same direction. With no communications between the beleaguered company and the relieving force, neither knew what the other was doing, although each knew, from the noise of Owens and Brens, that the other was in action. For the remainder of the morning the South Australians and Japanese exchanged desultory fire, and enemy mortars inflicted casualties on the defenders of Jivevaneng.

One of Grant’s problems was that a platoon of Papuans was cut off with his own two platoons. The Papuans, perhaps unrivalled at scouting and patrolling, were not fitted for a grim defence, as was well known. At 11.25 a.m. Grant wrote in his log: “Two PIB went bush”; at 6 p.m., “6 PIB go through.” Soon after midday Grant sent two Papuans to sneak out with a coded message for Joshua, and distributed the remainder “with our chaps to keep their courage up”.

During the late morning Joshua tried again to clear the enemy position east of Jivevaneng. While one platoon (Lieutenant Williams’4) “fixed” the enemy position from the left of the track, another fired on the position to support an encircling move by the remainder of Captain Richmond’s5 company round the right flank; but this effort failed because the Japanese were dug in along the track as well as across it.

At 3 p.m., when Grant’s company was repelling another attack, Joshua decided to bring up a further company to help overcome the enemy. As the approach on the left flank would be up a precipitous slope through a tangle of bamboos and undergrowth, he decided that Richmond’s company would support an encircling move round the right flank by Captain Gordon’s company.

At 3.30 p.m. the Papuan messengers got through to Joshua and handed him Grant’s message which stated: “HQ attacked on 2 flanks. Amn deficient. 8 casualties. ... Enemy deployed west 40 to 50. Wireless destroyed and cable cut.” Half an hour later he received another message, this time from the 20th Brigade to the effect that small parties of Japanese had been seen on the Song near the northern approaches to Scarlet Beach. Hastily Joshua ordered Captain Siekmann to send one of his platoons from the Katika Track to reinforce what the battalion diarist referred to as the “odds and sods” at the mouth of the Song.

The two-company effort fared no better than the earlier one. By 5.20 p.m. two of Gordon’s platoons were deployed 100 yards on the right of Richmond’s positions, but when the right-hand platoon (Lieutenant

Coen’s6) tried to move forward it was fired on from a steep feature ahead. As no advance seemed possible the companies dug in for the night.

In and around Jivevaneng Grant and his platoon commanders (Lieutenants Foley7 and Clifford8) were now very worried about the shortage of ammunition, and the men were warned to fire only at movement or observed targets. By last light Grant had suffered 12 casualties including two killed. There was no chance of sending out patrols to find the encircling enemy as the perimeter would have been too depleted. The only possible course was to defend, and to go on defending, even though the men were well aware that by this time the enemy should know nearly every one of their foxholes. Once when Grant told a man to be quiet he replied: “It’s all right, Skipper, they know we are here.”

Most of these enemy attacks on Jivevaneng came from the direction of what would normally be regarded as the platoon’s rear. The fifth attack was beaten off at 5 p.m. mainly by the 3-inch mortar, fired at 200 yards. Two hours later a bugle call sounded, followed by yells, as the Japanese prepared to attack. Two more 3-inch mortar bombs into the same north-eastern area from the same range changed the yells to screams. Another bugle call sounded and then silence. Later a dog prowled barking, and sounds of digging were heard until midnight.

On the morning of 2nd October the policy of firing only at definite targets was resulting in a large number of casualties being inflicted on the enemy, but the small force in Jivevaneng was also losing men under the steady enemy bombardment. At 11.30 a.m. it began to rain and soon the weapon-pits were full of water. Two hours later the Japanese opened up with many weapons, but so heavy was the downpour that it was difficult to tell the noises apart. The din ceased at 2 p.m. and the men began to bail out their dismal weapon-pits. Two more attacks during the afternoon were beaten off; almost invariably the Japanese attacked from the same position.

At 1.15 p.m. in heavy rain Richmond’s company, supported by fire from Gordon’s on the right, advanced. Lack of precise knowledge of the enemy positions doomed the attack to failure, and despite the courage of the men they were forced back after having pushed ahead for 80 yards. On the extreme right flank Private Ronan9 crawled to within 20 yards of a Japanese position and shot 6 Japanese with his rifle. The Australian casualties were heavy-7 missing and 12 wounded.

It seemed to Windeyer as he hurried north from the Bumi on 2nd October that Finschhafen had fallen just in time. He knew that he had taken a risk in concentrating his force to the south, but Finschhafen was his objective and his bold plan had succeeded. What was the situation now confronting him? After a bitter fight the Japanese had retreated, and

the coastline from Lae to just south of Bonga was in Australian hands; but round Finschhafen the captured territory was held by only a thin red line; and, if the Japanese had inland bases and the strength and determination to attack, they could choose where to do so. Indeed the initiative might soon pass to the enemy unless reinforcements arrived quickly.

The three battalions of the 20th Brigade were now in the southern area; the 22nd, now under Windeyer’s command, was in the area south of Langemak Bay and the Mape River. Three companies of the 2/43rd Battalion were fighting along the Sattelberg Road and a fourth was along the Katika Track. A mixed group of machine-gunners, Pioneers and Papuans was guarding the area from the Song to North Hill.

Windeyer had to hold the area from Bonga to Dreger Harbour and capture Sattelberg. He regarded this as a large order. To attempt to force a way to Sattelberg via Jivevaneng where the enemy had dug in, however, would not be “propitious”, as Windeyer termed it. He decided, therefore, to press on and capture the Kumawa area with the 2/17th Battalion in order first to disorganise the enemy’s retreat from Finschhafen by cutting the track through Gurunkor-Kumawa-Sisi-Sattelberg, and then to bring pressure on Sisi in order to secure the road junction there and assist an advance up the Sattelberg Road. Thus at 7 p.m. on the 2nd, Colonel Simpson received orders to move early next morning to an assembly area near the airstrip where the battalion would probably move west towards Kumawa.

In his planning Windeyer had also to take account of a signal received from General Wootten on the 2nd, that the 2/43rd Battalion should not be used operationally if possible, but should be kept in reserve ready to join the 24th Brigade which was soon due to arrive. As the 2/43rd had already suffered casualties along the Sattelberg Road, Windeyer decided that it should be withdrawn after the 2/17th had captured Kumawa and Sisi, thus severing the enemy’s lines of communication to Jivevaneng. In the meantime the 2/43rd would close the gap of about 400 yards between it and its isolated company, preferably by advancing, but, if necessary, Grant should fight his way back to the main body.

The 22nd Battalion was made responsible for searching, mopping up and holding the area south of Langemak Bay with detachments at Logaweng and Dreger Harbour. The 2/15th Battalion would hold Simbang and patrol to Tirimoro; while the 2/13th would be in reserve at Kakakog and would also patrol to Tirimoro.10

By this time the senior commanders had before them an operation instruction from NGF issued on 29th September stating that on 10th October General Kenney’s main bomber force with necessary fighter escort would be diverted to assist operations in the South Pacific; on 1st November Admiral Carpender’s naval forces would be relieved of responsibility for sea transportation to Lae and on 15th November to Finschhafen; and towards the end of November both air and naval forces would again be diverted to support operations against western New Britain. Allied air and naval forces, however, would “support I Aust Corps operations as far as practicable without interference with missions assigned in support of [New Britain] operation”.

On 30th September General Herring had flown to Lae for a conference with Generals Wootten and Milford. Anticipating the fall of Finschhafen, Herring gave verbal orders for Wootten to defend Finschhafen, develop it as a base sub-area, and gain control of the east coast of the Huon Peninsula up to and including Sio. Wootten was to move the balance of the 9th Division, less one brigade, to Finschhafen “at his discretion”. He was told what he had already guessed: that the only craft available would be the boat battalion of the 532nd EBSR and a boat company from the 542nd EBSR The operations for the capture of Sio, which entailed the clearing of the flank at Sattelberg, should begin as soon as possible. An immediate task would be the capture of the Tami Islands. Wootten immediately warned Brigadier Evans to have a reconnaissance party from his brigade headquarters and from one of his battalions (2/28th) ready to join in a divisional party leaving soon for the Dreger Harbour area.

It was now evident that there was much Japanese barge movement along the east coast of the Huon Peninsula. More by luck than by good management the American PT boats so far had not sunk any barges and other craft belonging to Task Force 76 or to the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade. On several occasions, however, lack of close cooperation between land and naval forces had nearly resulted in a catastrophe.11

To prevent such possibilities in future, Admiral Carpender on 30th September discussed with General Berryman and the commander of the PT boats the question of producing a workable system of cooperation so that PT boats could give more effective support to the land forces. It was clear that coordination could not be effected from 200 miles away. The only satisfactory system would be one of direct personal contact in

the actual area of operations between the PT boat command and the local army command.

On 1st October General Mackay, accompanied by General Morshead who had arrived in Port Moresby on 29th September, flew to Lae for a conference with Generals Herring, Milford, Vasey and Wootten. It had been arranged that for the supply of Finschhafen half the shore battalion of the 532nd EBSR would come under command of the American advanced base at Lae immediately, and on 3rd October the rest of the 532nd EBSR would come under I Corps’ command at Finschhafen. The remainder of the 2nd ESB would stay under Carpender’s command except for a boat company of the 542nd EBSR, which would be reinforced by twenty LCMs and would be employed to support the USASOS base at Lae and for supply along the coast to Finschhafen. The support to be expected being known, the role of I Australian Corps could now be more clearly defined. The main tasks of the 9th Division had already been outlined by Herring to Wootten on the previous day. In addition, the corps commander would be responsible for establishing in the Finschhafen area by 1st December an air base for staging one group of fighters and two light bomber squadrons, and a naval base from which light naval vessels could operate in Vitiaz Strait; he would need to keep in mind the later development of Finschhafen as a major army, navy and air base. Operations and construction activities must be so conducted as to require minimum air support after 9th October. The consolidation of the Huon Peninsula would be effected by infiltration up the coast by operations so conducted as to avoid commitment of amphibious forces beyond those of the boat battalion under command; exploitation beyond Sio should not be undertaken without reference to New Guinea Force.

The instruction gave the 7th Division a similar role: protection of newly-constructed airfields, and limited its operations beyond Dumpu to patrolling only. Finally, after the capture of Sio and Dumpu, “the role of I Aust Corps will probably be restricted to active patrolling and vigorous infiltration and defence of the I Aust Corps area”.12

At the conference on the 1st Herring spoke mainly of his supply difficulties and stated that the development of the airfields areas was entirely dependent on the navy. He pointed out that some of the landing craft which took five hours to load at Buna only stayed two hours at Lae, thus discharging only portion of their cargoes. Wootten stated that when he got the boats due on the 3rd he could “clean up Finschhafen and go on to Saidor”.

General Blamey had already decided that the time had come to give Herring a rest and bring in a new corps commander and staff. Since the return of the 9th Division, General Morshead had been promoted to command and train II Corps (the AIF) on the Atherton Tableland. He then suffered the not-unexpected experience of having the 7th and 9th Divisions sent to New Guinea while he remained in Australia, a corps commander without a corps. On 23rd September Morshead lunched with Blamey and learned that he was at last to have an active command against the Japanese, as his corps headquarters would soon relieve Herring’s in New Guinea. As previously narrated, he arrived in Port Moresby on 29th September and attended the conference at Lae on 1st October. Blamey meanwhile signalled Mackay to arrange the changeover whenever he wished. It was decided that the relief should take place on 7th October. Morshead arrived at Dobodura at 11.15 a.m. on the 7th and half an hour later Herring left for Port Moresby and Australia.

With his departure from New Guinea, General Herring’s period of active service was over – although this was not known at the time. He had given able service in a high appointment through the vicissitudes of a year’s fierce campaigning, starting with the anxious Papuan battles, and needed a rest. When he left New Guinea it seemed certain that in due course he would relieve Morshead, but in February 1944 he became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Victoria.

Now that the general outline of the plans for supplying Finschhafen were known the commanders could proceed with greater confidence. In order to find out exactly how many landing craft were actually at his disposal, Wootten sent Colonel Barham, his GSO1, to Dobodura, where he ascertained that the craft available from the 532nd EBSR would be 63 LCVs and 10 LCMs, while those from the company of the 542nd EBSR would be 54 LCVs and 19 LCMs.

At this time the subsidiary operation was taking place against the Tami Islands. As mentioned, when the planning for Finschhafen was being

rushed ahead, Herring ordered Wootten to establish a radar station on the Tami Islands which were well placed to give warning of the approach of hostile aircraft from New Britain towards Lae and Buna. A company was deemed sufficient to capture the islands and guard the radar station, and Wootten gave the task to Brigadier Edgar of the 4th Brigade, who detailed a company of the 29th/46th Battalion for the task. It was to land at the same time as the 20th Brigade’s landing on Scarlet Beach. The operation was postponed, however, when Wootten was informed that Barbey considered that navigational difficulties made it desirable to wait until he could provide suitable naval escort. On 25th September two barges were reported to be moving from the Tami Islands towards Lange-mak Bay; on the 27th Mackay informed Herring that the navy wad air force were anxious that radar equipment should be installed on the islands.

It was now decided that the expedition should be made by a company of the 24th Brigade and Evans gave the task to the 2/32nd Battalion. Major Mollard, administering command of the battalion in place of Lieut-Colonel Scott who was ill, chose Lieutenant Denness’ company. As well as the company, “Denness Force” would consist of a radar detachment, pioneers, mortars, signals and a section of six .50-calibre machine-guns from the 532nd EBSR which also provided the landing craft (2 LCMs and 14 LCVs). This expedition left the loading beaches at Lae at 11.15 p.m. on the 2nd. After encountering very rough weather, high seas and continual rain, the convoy arrived off Wonam Island, which seemed to have the best beach. The six rear boats reduced speed while the command craft moved in for a reconnaissance. When the craft was about 30 yards from the beach four natives came out of the jungle fringe waving their arms in a friendly manner. The interpreter then learnt that there were no Japanese on the islands. The natives swam and paddled canoes to the craft and were taken aboard as guides through the channel into the lagoon between Kalal and Wonam. As Kalal was the highest island Denness landed on the South-east corner at 8 a.m. and rapidly decided on the location for the radar station. All the assault craft unloaded and one was sent back to guide the supply and equipment craft from Kasanga. By 2 p.m. unloading was finished and all the landing craft, except the two to remain with Denness Force, returned to Lae.

One of Denness’ first tasks was to round up the natives-74 in all. They were short of food, and, because of their terror of bombers and strafers, they had been living in dank, low-roofed and foul-smelling caves

dug out of the coral. All were set to work and treated well. In his report Desmess wrote:

Information gained from them [the natives] is that about last Easter a force of over 100 enemy were encamped on the islands, but left after about a month. Returning with a stronger force of approx. 200 about two months ago, they set up a wireless station, and a complete defence system on the islands. The evidence of this defence system still exists. They were strongly entrenched around the whole of the islands, in large, heavily-reinforced bunkers and air-raid shelters dug in the side of the coral cliffs. Allied bombers and strafing planes made several attacks, the success of which is very evident. Later many barges came in one night and the whole enemy force was withdrawn. The distress of the natives was brought about by the shortage of food, as all pigs, chickens and vegetables were commandeered by the enemy.13

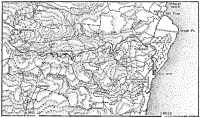

Meanwhile, elements of Windeyer’s five infantry battalions were moving to their new positions. From 8 a.m. on 3rd October the 2/17th Battalion was being ferried in three-tonners north from Kolem to a track junction near the airstrip. From here the battalion was to be led by native guides along a track negotiable by jeeps to Kiasawa 1 and thence by a native pad through Kiasawa 2 to Kumawa. This very difficult route was ironically named Easy Street.14

Grant’s company of the 2/43rd Battalion was still at Jivevaneng, where, on the 3rd, no attacks were made by the Japanese. Four hundred yards east were two other companies of the 2/43rd. A patrol from Captain Gordon’s company in the morning reported that the Japanese who had halted the Australian attack on the previous day were still in position. At 11.30 a.m. Colonel Joshua sent another message to Grant by a small Papuan patrol led by Sergeant Scott-Holland,15 ordering him to withdraw to Zag via the Tareko Track. Half an hour earlier, however, Grant had already decided on a plan to evacuate, and because of the ensuing bombardment of Japanese positions the Papuan patrol was unable to get through that day.

From midday till 1 p.m. the artillery fired 100 shells on the Japanese about Jivevaneng. Some of the shells fell among the defenders, but no casualties were suffered as all were below ground. Under cover of this bombardment and 152 mortar bombs another patrol of platoon strength from Gordon’s company tried without success to get through to Jivevaneng. At 3.40 p.m. Windeyer went to the 2/43rd’s headquarters, informed Joshua of his plan that the 2/17th should capture Kumawa and ordered the 2/43rd to attack in the Jivevaneng area with the double object of supporting the 2/17th and relieving Grant.

After fifteen minutes of artillery and mortar fire, Lieutenant Combe16 led a company into the attack at 5.45 p.m. to the left of the track. Fierce

fighting ensued as the attackers tried desperately to do what had so often been proved costly in jungle warfare: attack well-dug enemy defences by a route well known to the enemy. Soon the company was pinned down. In a leading section Private Dabner17 manned the Bren when one of the gunners was wounded. Running out of ammunition he then silenced two enemy posts with grenades, and, when his platoon commander was killed, he took charge of the platoon. The two forward platoons were both pinned down when Combe, wounded and with his Owen shot out of his hands, led his reserve platoon forward. After half an hour’s severe fighting he sent back a message: “Held up by frontal and enfilade fire, unable to proceed further.” Having suffered 17 casualties including 6 killed, Combe withdrew.

Since its arrival the 2/43rd Battalion had lost 47 including 14 killed and 5 missing. Late at night Windeyer ordered Joshua to attack on the 4th if Grant were not extricated by then.

Windeyer had also to contend with a sudden threat from the north. The track north from the Song to Bonga had been regularly patrolled since the landing, and a patrol skirmish had occurred along the track on the previous day. At 7.15 a.m. on the 3rd one Japanese was seen approaching the position of the 2/43rd’s anti-tank platoon (Lieutenant McKee18) 450 yards north of the Song on the coastal track. The scout was shot, but during the next four hours three attacks were made on the platoon’s position, each time by 30 to 40 Japanese advancing at a jog trot. The platoon repulsed all attacks, and the Japanese withdrew about 1,000 yards and dug in.

These Japanese now appearing on the northern front were from Lieut-Colonel Shobu’s II/80th Battalion which had recently been on the Mongi River. On 28th September Colonel Miyake of the 80th Regiment had ordered that “the Shobu battalion is to seek out and attack the enemy who is advancing in our direction from the Song River”. After a circuitous march, probably through Wareo and Gusika, this battalion was now ready to attack.

Major Broadbent, worried by the proximity of the Japanese threat to Scarlet Beach, immediately sent Major P. E. Siekmann’s company of the 2/3rd Pioneers hurrying north to reinforce Captain Nicholas’ company of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion and the elements of the 2/43rd west of the mouth of the Song. Later in the day Lieutenant Blackburn’s19 platoon from the Pioneers counter-attacked the Japanese positions along the track, but came under heavy fire from a small knoll. Two men were wounded before the platoon made a flank attack. Leading his section, Corporal Moreau20 stood up and threw grenades at the Japanese, and drove them off.

By the time the 2/17th Battalion reached the Easy Street junction, Windeyer knew about the attack north of the Song and decided that Broadbent’s small force must be reinforced immediately. The 2/13th Battalion was too far away in the Kakakog area to be an effective reserve for Scarlet Beach; Windeyer wished to proceed with his plan of sending the 2/17th to Kumawa, as this seemed the most likely place in which to regain contact with the enemy who had retreated from Finschhafen; it seemed best, therefore, as an ad hoc solution, to divide the 2/17th Battalion into two groups. Two companies – Major Pike’s and Captain Shel-don’s – were detached and organised with a separate headquarters under Major Maclarn, the commander of Headquarters’ Company. By last light Maclarn’s detachment had joined Broadbent near Scarlet Beach, while Colonel Simpson led the remainder of the battalion to Kiasawa 1.

On the 4th pressure suddenly eased on both the trouble fronts. Grant received Joshua’s message to evacuate at 7.30 a.m. when Scott-Holland, with two Papuans, finally got through. On the previous afternoon the three men had worked through the jungle at the head of the Quoja River, avoiding several parties of Japanese. When the Australian mortars had opened up the patrol was 150 yards south of the village. After retiring, the patrol lay in the jungle all night and finally reached Grant’s positions at dawn.

At 9.15 a.m., after Grant had given his orders to withdraw, Boomerangs of No. 4 Squadron dropped ammunition and supplies and a message instructing Grant to fight his way out. Soon after midday a reconnaissance aircraft reported that the supplies had been dropped in Jivevaneng, but there were no signs of anyone coming to collect them. Led by Scott-Holland’s patrol, Grant’s Australians and Papuans, carrying their wounded, had already left Jivevaneng. At 1 p.m., strangely unmolested, they met a patrol which had been sent out by Joshua to reach Jivevaneng by the left flank. The defenders had suffered 12 casualties including two killed, but Grant estimated that at least 50 enemy had been killed. By 3 p.m. the weary men reached battalion headquarters and were sent down the track towards Zag to protect the lines of communication.

To the north Windeyer at 8.30 a.m. instructed Maclarn to find a position north of the Song whence his detachment could attack the Japanese force. During the morning two platoons of Siekmann’s Pioneer company moved forward with the 2/43rd’s anti-tank platoon on the left flank. Skirmishes, during one of which Blackburn was mortally wounded, forced the enemy to withdraw, although they continued intermittently to fire on the Australians from farther north. At 11.30 a.m. an officer in an LCV reconnoitred the Japanese positions from the sea. About 900 yards north of the Song he drew fire, but from no farther north. Thus the general whereabouts of the enemy was established, and Maclarn was instructed to attack.

By 2.15 p.m. a platoon of the 2/43rd re-established contact with the Japanese north of the Song; and soon afterwards Maclarn’s men reached the Song. At 5 p.m. he was ready to send Pike’s company into the attack,

his plan being to push east to the coastal track, hold it with one platoon and attack south towards the platoon of the 2/43rd. An hour later, after an artillery bombardment, Pike’s company moved forward in single file across the kunai to the edge of the timber where the ground dropped sharply for about 50 feet. After walking through kunai for most of the day it was like going into an air-conditioned picture show to walk into the jungle. Heavy fire from the edge of the jungle wounded three men in the leading platoon. Because of failing light and the amount of fire coming from the gloom, Maclarn decided to wait until next day to press the attack. By last light a Papuan patrol reported that the Japanese had withdrawn from their positions round Jivevaneng, apparently about the same time as Grant, probably because of casualties suffered in attacking Jivevaneng and in withstanding the 2/43rd’s attacks. Two companies of the 2/43rd occupied Grant’s former position.

On the 5th Maclarn moved farther up North Hill in a deeper encircling move before launching a two-company attack at 4.50 p.m. He met no opposition and joined the platoon of the 2/43rd to the south after passing through Japanese positions which showed signs of hurried evacuation. By last light it was arranged that a company of the 2/43rd would take over the North Hill area from the 2/3rd Pioneers and Maclarn’s force at dawn.

Along the track to Kumawa on the 5th a Papuan patrol made contact with an enemy post in the village. The patrol returned and informed Captain Dinning, whose company was in the lead, that natives in the enemy’s camp had spotted the patrol. By 12.30 p.m., after a sharp encounter in which six casualties were inflicted on the enemy, Kumawa was captured by Dinning’s company. By last light Simpson’s headquarters was in the village and Main’s company near by. That night the artillery shelled Sisi.21

On the 6th Captain D. C. Siekmann’s company of the 2/43rd relieved Major P. E. Siekmann’s company of the 2/3rd Pioneers – they were brothers. The Pioneers took up a position about 800 yards west of Katika. As patrols found no sign of the enemy up to Bonga, Madam’s detachment of the 2/17th was withdrawn to the mouth of the Song. During the morning a Papuan patrol from Jivevaneng found the enemy in position on a feature known as “the Knoll” about 500 yards west of the village.

It was in the Kumawa area that the enemy now appeared most active. Early on the 6th a platoon of the 2/17th accompanied by a Papuan section, patrolled the track north to Sisi with the hope of occupying it, but the Papuan scouts soon reported an enemy position on the rising ground to the west of the track about 700 yards north of Kumawa near the Quoja River. Simpson then sent Dinning’s company forward up the track to keep contact.

During the day there were several skirmishes with the enemy to the west. One Japanese soldier of the III/80th Battalion wrote in his diary that day: “I went on an officer patrol to Kumawa village. Saw for the first time enemy soldiers at a distance of 30-40 metres wearing green uniforms.”

In particular, a platoon left at the track junction near Kumawa had to deal with several bands of Japanese still escaping from Finschhafen, and Simpson became anxious about his lines of communication. It was obvious too that, if the 2/17th were to vacate Kumawa as originally intended and advance through Sisi to the Sattelberg Road, the Kumawa area and Gurunkor Track junction might be occupied by the enemy. Kumawa was too valuable to lose; it controlled the main route to Sattelberg from the south (although tracks existed through Moreng and Mararuo); it gave observation and access to the Sattelberg Road and Sattelberg itself. But at least one company must remain to protect Kumawa from north, south and west, thus depleting the force available for a push to the northeast.

While adhering to his original intention of eventually concentrating the 2/17th on the Sattelberg Road, Windeyer considered that, for the present, Simpson must remain about Kumawa. At the same time he decided to bring Maclarn’s detachment to Jivevaneng to relieve the companies of the 2/43rd, and thin out his southern flank by bringing the 2/15th to Kumawa. He hoped that, once the 2/15th was at Kumawa, the offensive could be continued with one battalion advancing up the Sattelberg Road and one moving round through Mararuo.

The engineers were beginning to convert Easy Street into a jeep track, a difficult task, for the slope was extremely steep. Heavy rain fell throughout the night, filling the foxholes and trenches and turning the tracks into small streams.

North of the Song, Siekmann’s company of the 2/43rd Battalion moved to a position near Bonga on the 7th. This was in accordance with a message which Windeyer had received from Wootten that the junction of the Gusika–Wareo track should be seized. A patrol forward to Bonga found it unoccupied. Early on the 7th Maclarn’s column of the 2/17th Battalion was on the move again, and relieved one company of the 2/43rd just east of Jivevaneng. During the afternoon two patrols from the 2/17th, led by Lieutenants Bennie22 and McDonald,23 found the positions of the enemy’s left and right flanks respectively, a useful task to have accomplished so soon after arrival.

From very early on the 7th the Japanese were pressing on Simpson’s half-battalion at Kumawa from the North-east, west and south. As his positions were so thinly held, and as the platoon at the track junction appeared to be in danger of encirclement, Simpson withdrew Dinning’s company to thicken his line and preserve his communications. Often

during the day fire was exchanged with infiltrating bands of the enemy, upon whom several casualties were inflicted. Ammunition and one day’s rations were carried forward to the track junction by natives during this miserable day when it rained so hard that the slit trenches were again filled and the area was turned into a quagmire. From the track junction the stores were carried forward by the troops themselves so that the native carriers would not be unduly exposed to fire.

It was obvious that the enemy was very alarmed at the loss of Kumawa and would do all in his power to regain it. There was little Simpson could do except hold on to his positions and hope that the 2/15th would soon arrive. Taken in trucks to the track junction near the airfield, the 2/15th Battalion, less two companies which were returning across the Mape River, reached Kiasawa by last light. The remaining two companies bivouacked near the Easy Street junction. Further heavy rain during the night gave the troops in the forward areas a most uncomfortable night, made it impossible to use jeeps on Easy Street, and swept away the engineers’ bridge over the Song.

On the 8th the men learnt that headquarters of II Corps had relieved headquarters of I Corps. The diarist of one 9th Division battalion expressed the affection and esteem in which General Morshead was held by the men whom he had led in the Middle East:

We learnt tonight that 9 Aust Div is again a part of 2 Aust Corps. As it is commanded by Lt-Gen Sir Leslie Morshead, this re-allocation is welcomed by us.

At 8 a.m. on the 8th Dinning reported seeing a large force of Japanese moving north along a ridge about 200 yards west of the track. On this excellent target the concentrated fire of the company inflicted heavy casualties. An hour and a half later all lines from battalion headquarters to Dinning’s company and to brigade headquarters were cut by a Japanese party which crossed the track between Kumawa and Dinning’s position. During the next three hours the Japanese made several attacks on the two platoons in Kumawa. This was no new experience to Main’s men, who threw back all the attacks. By 1 p.m. a patrol from Kumawa reopened the track to Dinning’s company and a telephone line was quickly relaid.

The vanguard of the 2/15th Battalion now reached the Kumawa area, and by 4 p.m. the two rear companies arrived and the battalion dug in between Kumawa and the track junction while Dinning’s company moved to Kumawa. The heavy rain had made it impossible for jeeps to use the track from Kiasawa. Along the long and difficult supply route native and Australian porters had to carry the supplies. Since the 5th Simpson’s men had only had nine scanty meals and by last light on the 8th there were no rations left at all. “This problem of supplies,” commented the battalion’s diarist, “prevented us from being able to take further offensive action towards Sisi.”

To the south the 2/13th Battalion was now in position, from Simbang to Tirimoro, to protect Finschhafen. South of the Mape the 22nd Battalion watched the approaches to Finschhafen in the Butaweng–Logaweng

area. Colvin had already sent a patrol to Logaweng to get in touch with the luluai and tell him to bring in native carriers.

In Jivevaneng on the 9th Maclam decided to capture the Knoll in order to improve his tactical positions. At 9.30 a.m. Sheldon’s company set out to encircle the Japanese round their left flank positions which had been discovered the previous day. An hour later Sheldon reported that his company was in position undetected about 50 yards from the Japanese positions north of the track. Artillery then bombarded the Knoll for a quarter of an hour. Led by Papuan scouts, Bennie’s platoon sneaked to within ten yards of the Japanese. Lieutenant Williams’24 platoon followed closely, with McDonald’s in the rear. The approach up which Bennie was about to attack was a steep and heavily wooded slope rising from a ravine. The approach from the south was similar, while that from the east was along the road, where the turns, first to the right and then to the left, were guarded by machine-guns.

Suddenly, at 11.10 a.m., Bennie’s men opened up on the enemy posts ahead. There was no stopping the dash of the attack and the 75 yards to the road were covered quickly and several Japanese posts wrecked. Three posts and their occupants were destroyed by Private Brooks25 firing his Bren from the hip. In the final assault on the Knoll itself only one Japanese was encountered and he ran. Nine Japanese had been killed for the loss of four wounded. By 1 p.m. Sheldon’s company was digging in on the Knoll where there were about 60 Japanese holes.

Half an hour later Lieutenant McLeod’s platoon moved up to reinforce Sheldon. After mortar fire, the Japanese counter-attacked from the low ground north of the road where they had been driven. Preceded by a bugle call and encouraged by the usual cheers, the Japanese attacked viciously and some got to within five yards of the defences before they were beaten back. Grenades were rolled down among them and the automatics of the defenders ran hot repulsing the counter-attack. When Sheldon was wounded by mortar fire Bennie took charge of the defence and handed over his platoon to Sergeant Wood.26 At 6.45 p.m. a second counter-attack, this time of company strength and in grim silence without the bugle and cheers, was also repulsed. Most of the attacks were being made against Wood’s platoon. When one of his Bren gunners was wounded Wood dashed forward to the weapon-pit and manned the Bren. For the loss of 13 casualties, including 4 killed, Maclarn’s detachment had captured a vital feature.

The supply difficulty was such that Windeyer felt that, before the 2/17th and 2/15th could advance, reserves of ammunition and general supplies must be built up. The 2/17th Battalion diarist, describing the day for Simpson’s column, wrote: “The enemy caused us no trouble ... but our stomachs did.” Maintenance of the 2/15th was becoming pre-

carious because of the very bad state of the wet track and the risk of the enemy cutting it, but Colonel Grace turned down an offer by Win-deyer to arrange an air drop because he believed that the Japanese did not yet know of his men’s presence in Kumawa, where he had a chance of intercepting any belated parties moving towards Sattelberg along the track from Tirimoro. At present the toiling engineers had pushed the jeephead to Kiasawa 2. The few native porters available were used on the Easy Street supply line, together with a company of the 2/15th and another of the 2/3rd Pioneer Battalion.

All round the Australian front on the 10th there was evidence that the Japanese intended to contest the Australian gains. A patrol of the 2/43rd Battalion found signs of considerable enemy movement along the tracks in the Bonga and Gusika areas, indicating that large numbers of reinforcements were arriving from the north. As be now had two of his companies north of the Song (the others being still on the Sattelberg Road), Colonel Joshua moved his headquarters 200 yards north of the river. To the south Lieut-Colonel Gallasch’s27 2/3rd Pioneer Battalion, all of which had now arrived, was made responsible for close defence of Scarlet Beach. That the enemy was patrolling extensively became clear when a patrol from the 2/43rd encountered a Japanese patrol between Zag and the main coastal track, and killed four of them.

At 1.30 p.m., an Australian and Papuan patrol led by Lieutenant Graham28 of the 2/17th arrived at Jivevaneng after finding a feasible route from Kumawa across the Quoja River. Graham had left Kumawa at 8 a.m., and after going about 1,000 yards east of Kumawa bad moved directly north to Jivevaneng. At 2.45 p.m. an enemy 70-mm mountain gun began firing rapidly on the Knoll. Within five minutes 53 shells were fired, and two men were killed and two wounded. Then the Japanese attacked with what appeared to be two companies, one on each flank. The attack, which was the fiercest yet, was repulsed, and three more counter-attacks during the afternoon were also driven back. During each thrust the Japanese were encouraged by the blowing of bugles, and as they charged upwards they shouted what appeared to be “Ya”. After the first attack the defenders replied with “Ya’s” and “Ho, Ho’s”.

West of Finschhafen the 2/13th Battalion also met Japanese stragglers and rearguards for the first time since the capture of Finschhafen. A patrol from Simbang, moving west along the north bank of the Mape, saw a lone Japanese sitting on the track. He escaped as did six others 50 yards farther along. At the junction of the river and Tirimoro tracks the patrol was fired on. As Colvin’s orders, received the previous day, were to patrol to Quembung and Tirimoro, but not to become involved in a serious fight, Captain Cooper was instructed to hold the position. Two light attacks were repulsed, and at 8.30 p.m. Japanese bombers dropped three bombs on the position, destroying a Bren gun and some equipment.

All was in readiness for the move of the headquarters of the 9th Division and the 24th Brigade to Finschhafen. At midday and again at 2.15 p.m. on the 10th landing craft departed from Lae for Finschhafen carrying the two headquarters. The first group had an uneventful voyage, but the second, of four LCVs, carrying Brigadier Evans and part of his headquarters, was bombed by two enemy aircraft near Finschhafen at 8.15 p.m., without much effect; these were possibly the same aircraft that had bombed Cooper’s position. Evans’ group disembarked at 11 p.m. at Finschhafen Harbour; Wootten landed at Finschhafen half an hour after midnight.

The area in which the 9th Division was now to operate was a formidable one. It lay between Sattelberg and Sio and the Mongi River Valley. The Cromwell Mountains, to the north of the Mongi, were a continuation of the high Saruwaged Range which terminated at its South-east end at Mount Salawaket (13,400 feet), where the range divided to form the Mongi Valley. The Cromwells dropped fairly rapidly from Mount Salawaket to an area about ten miles to the east where there were extensive areas of grass and swamp at between 5,000 and 7,000 feet. They continued at this elevation for almost all the remainder of their length, and fell away towards Sattelberg to a little over 3,000 feet. As the Cromwells were used for hunting by the natives there were innumerable tracks running towards the coast. Except for the track from the Hube district to Sattelberg, however, all were foot tracks only.

To the north of the range was the Kwama River Valley system containing the well-populated Selepe and Komba districts. A good track ran up the main valley of the Kwama to Iloko where the top of the Saruwageds could be reached in one day. It was along this track that some of the 51st Japanese Division had escaped. Another track ran from Iloko to Geronn, thence over the Cromwells to the Hube district. The northern and eastern slopes of the Cromwell Range were a series of coral terraces rising to between 1,500 and 2,000 feet. At the lower levels they were grass-covered, but south from Bonga into the Finschhafen area they were covered in jungle. Movement along the terraces resolved itself into a series of steep ups and downs in unpleasantly warm surroundings, and it was quicker, particularly in the Kalasa district, to go down to the coast, follow the coastal track and return inland at the required spot.

At that time it was estimated that about 47,000 natives lived in the Huon Peninsula, half of them on the Finschhafen-Sio fall of the ranges where the 9th Division would be operating. About 5,000 were coast natives of good physique, while the remainder were short, stocky mountain people. As with the folk of the Bena plateau, these mountain natives were poor labourers, and prone to malaria and tropical ulcers if employed on the coast. Unlike the wilder people of the Bismarck Ranges, however, they would seldom attack isolated men. It was these natives that Colonel Allan had been recruiting since the landing at Scarlet Beach. He found that the former administrative system of using luluais and tul tuls had been retained by the natives and could be immediately used.

Wootten decided that the vital ground was the Sattelberg mountain feature and the long narrow ridge running west from the coast at Gusika to Wareo. Patrols from the 2/43rd and from the Papuan Infantry had already established that the enemy was using the Gusika–Wareo track to carry supplies from the barges into the Wareo-Sattelberg area. Possession of this ridge would not only cut the enemy’s main supply route from the coast, but would prevent him observing the Australian activities along the coast as far south as Dreger Harbour. Wareo, at the western end of the ridge, was on a 2,600-foot plateau which dominated the Song River Valley and the country from Scarlet Beach to Sattelberg. It was also a junction of several important tracks – the Japanese inland track from Kalasa; the track from Kulungtufu in the rich Hube district; tracks down to the coast at Gusika, Kiligia and Lakona; and tracks to Sattelberg, Palanko and Nongora. All these tracks through Wareo were supply routes for the enemy based on Sattelberg, and routes which the enemy could use should he wish to contest the Australian possession of the coast.

“The capture of the Gusika–Wareo line would therefore both secure the Finschhafen area and provide the ground from which an offensive could be launched to drive the Japs from the east coast of Huon Peninsula and capture Sio, which were the two operational tasks given to the Div.”29 Unless Sattelberg were first captured, however, an attack on the Gusika–Wareo line could be endangered by an enemy attack on the left flank. Wootten therefore decided on two preliminary operations: first, the capture of Sattelberg, and second, the control of track junctions in the Bonga area with the object of cutting the enemy supply line from the coast and attacking Wareo from the east along the spur which joined it with Gusika.

He issued his first operation order in the new area on 11th October: “9 Div will reorganise and continue offensive ops to gain control of approaches to Wareo and Sattelberg with view to capture that area.” He divided the area into three sectors of responsibility. North of the Sattelberg Road and a line from Heldsbach Plantation to Arndt Point, the 24th Brigade, consisting at present only of the 2/43rd Battalion and the 2/3rd Pioneers, would protect the Scarlet Beach area in depth against any attack from west or North-west, and gain control of the Bonga Track junctions. The 20th Brigade would be responsible for the central sector between the Sattelberg Road and the Mape River, both boundaries being inclusive, and would “continue pressure towards Sattelberg with a view to its capture”. In the southern sector the 22nd Battalion would protect the area south from the Mape River and defend Dreger Harbour.

From the date of the Scarlet Beach landing the staff of the division had done all in their power to maintain the 20th Brigade by sending up supplies in the craft of the 532nd EBSR As the units themselves had also to be carried to Finschhafen in these small craft, the maintenance position was complicated: for example, it was impossible, with the craft available, to guarantee to replace an expenditure of more than 600 rounds of artillery ammunition each day, and at one stage only two days’

balanced rations were held at Finschhafen. Difficulties were increased by the irregularity with which supplies were brought to Lae from Buna. Lack of suitable craft resulted in a shortage of vehicles and workshop facilities and this remained acute throughout the campaign.30

For three weeks Windeyer had led his force in a fierce campaign to capture Finschhafen and then to hold it against an enemy whose strength had been under-estimated; Wootten thoroughly approved the dispositions as he found them. The courage and tenacity of the men of the 20th Brigade from 22nd September had been matched by the skill and determination of their leader. The brigade had lost 82 officers and men killed or missing and 276 wounded.

The main activity in the forward areas on the 11th was the move of Simpson’s column from Kumawa via Graham’s route to Jivevaneng. The Kumawa area was handed over to Grace at 9 a.m.; Simpson’s two companies departed half an hour later and arrived at Jivevaneng after a seven hours’ march. After Simpson’s arrival the 2/17th took up positions in depth along the Sattelberg Road from the Knoll 500 yards west of Jivevaneng to the feature known as “the Pimple” 400 yards east of the village.

Action on the 12th was mainly confined to patrolling. That day Joshua wrote to Evans that “patrolling has revealed the use by enemy of certain tracks on the high ground inland from Bonga some 1,500 yards. ... The enemy may be withdrawing by this route, or may be supplying and reinforcing Sattelberg area from a point on the coast further north.”

At Jivevaneng, Pike’s company, which was now on the Knoll with Bennie’s, prepared to occupy a small knoll forward from the main one. Captain Rudkin’s31 platoon was given the task of capturing this feature. The platoon managed to go only about 40 yards forward when it was fired on and pinned down; the forward scout was killed and four men including two section leaders were wounded. Sergeant Cunningham’s platoon then advanced along the south side of the road under cover of a ledge and reached unoccupied Japanese holes about 100 yards forward and level with the knoll. They could see the enemy level with and behind them, but because of the strong defences and the rugged terrain, the platoon was withdrawn and the enemy position mortared. The battalion decided to leave any further move forward until later, and to neutralise the enemy position by artillery and mortar fire.

On the 12th Wootten informed Captain Gore, who had arrived to command “C” Company of the Papuan Battalion, that he would have complete control of his company which would come under divisional and not brigade command. Experience had shown in the recent New Guinea campaigns that it would be difficult to keep the Papuans under one command as all front-line units were constantly asking for a few Papuans as scouts. Wootten stated that the Papuan company’s main task would be

to obtain information about the country and the enemy by deep patrols; first, into the Bonga-Wareo area, and second in the Wareo-Sattelberg-Mararuo area. No Australians were to accompany the Papuans outside the areas held by the 20th and 24th Brigades.

At 9 a.m. on 13th October Captain Angus’ company of the 2/15th attacked the enemy positions west of Kumawa; the company was fired on by enemy machine-guns sited about 150 yards from its start-line. Fierce fighting then began and raged for a quarter of an hour as the men attacked one Japanese post after another, sited in a line. Despite heavy casualties, Sergeant Else32 kept urging his platoon forward, and thus prevented the attack from becoming pinned down. Private Woods,33 commanding the leading section, from a distance of 30 yards immediately charged the first enemy machine-gun to open fire. Two of his men were killed and 4 wounded, leaving only himself and another man unhit, but Woods continued to advance, firing his Owen gun and throwing grenades, and silenced the post. Woods then engaged a medium machine-gun 20 yards away which had been causing casualties in another section. This enabled the rest of Else’s platoon to storm the remaining two posts. During his undaunted fight, Woods used 12 grenades and about 15 Owen gun magazines. A rifleman himself, he had discarded his rifle for an Owen and gathered the ten extra grenades from his fallen comrades. As with the attacks on Snell’s Hill, the east bank of Ilebbe Creek and the Knoll west of Jivevaneng – positions which seemed impregnable – the enemy company was unable to withstand so spirited and determined a challenge. Having lost 39 killed, the defenders fled; the attacking company suffered 30 casualties including 5 killed; in Else’s platoon 15 of the 26 men were hit.

The loss of this position west of Kumawa affected the Japanese of the III/80th Battalion keenly. A soldier wrote: “Enemy is now closing on our position. With tears in our eyes we had to withdraw. ... Muddy roads, steep mountain trails. ... The trench, which is the safest place, is filled with water.”

Japanese security regarding documents, maps, prisoners, marks of identification and diaries, was still extremely poor. Vital operation orders and marked maps were still being carried in the front line by Japanese officers. Japanese headquarters still refused to believe that soldiers of Japan could be taken prisoners, and consequently the soldiers were given no instructions as to their behaviour when captured. Their only instructions were that they should save their last grenade to blow themselves up, and thus avoid disgracing Japan, and incidentally falling into the hands of the brutal Australians and Americans who would probably eat them or torture them.

Sullen at first, and fatalistically expecting the worst, Japanese prisoners seemed surprised at the fair treatment accorded to them, and soon were keen to give information. Often they would ask to see the interpreter again and tell him everything. Their motive probably was that, having disgraced themselves in their country’s eyes by becoming prisoners, they sought to regain self-esteem by raising their stature in the eyes of their captors.

It was from diaries that the Allies were learning most about their enemies. Most Japanese soldiers carried diaries, in which they wrote down their reactions to

events. Diaries captured at this time were usually compounded of frustration at the failure and limitations of Japanese arms, despair at their own situation, optimism at the slightest hint of a change for the better, vitriolic hatred of their enemies, propaganda slogans, and some doubts about ultimate victory.

Around the remainder of the divisional front on 13th October activity was confined largely to patrolling. Captain Cribb’s company of the 2/13th occupied Tirimoro while Captain Cooper’s found the enemy position at the track junction deserted, and patrolled along the Quembung Track where marks of a field gun were seen.

The 14th was a quiet day on most fronts. In the northern sector Lieut-Colonel Norman and half his 2/28th Battalion arrived at 2.30 a.m. in craft from Lae, after being harmlessly bombed off Finschhafen. Only along the Katika Track was there any evidence of aggressive intentions by the Japanese. From his position about a mile and a half west of Katika, Captain Fisher34 of the 2/3rd Pioneers patrolled forward along the track at 2 p.m. with two warrant-officers – Bernard35 and Hughes36 – and Privates Brown37 and Page.38

About 450 yards forward of the company position Brown and a Japanese saw one another on the track and the Japanese was shot dead. Bernard, attempting to find the enemy flank, was killed. Covered by Brown, who fired eight Owen magazines during the action, the other men attempted to reach Bernard. Page was killed and Fisher wounded, but under cover of Brown’s grenades and Hughes’ rifle fire, Fisher managed to escape. Brown’s aggressive action was mainly responsible for the three men withdrawing safely, and probably for preventing the enemy from making a direct attack to the east. At 5 p.m. the signal wire was tugged from the direction of the enemy. As Captain Knott’s39 company of the 2/3rd Pioneers was about half a mile farther along the Katika Track where it took a bend to the south, it appeared that the enemy had infiltrated between the two companies.

On 5th October documents captured north of the Song by Maclarn’s detachment had indicated clearly that the enemy was not in full retreat, but apparently intended some offensive action. At night on the 11th Wootten’s newly-arrived headquarters had warned the two brigade commanders that an intercepted enemy wireless message sent between Sattelberg and Sisi stated that “the crisis is at hand”. The probability of a counter-attack was indicated also by aerial and naval reconnaissance. During the night 12th–13th October PT boats patrolling as far north

as Umboi Island, sank an enemy ketch and damaged another off Tuam Island, strafed the beaches at Gizarum, and damaged about eight barges. Another important barge hide-out on Long Island had also been found. The heavy damage inflicted on barge traffic first by air attack and later by PT boats as well, caused the Japanese to pay careful attention to camouflage of their barge hide-outs and adjacent bivouac areas, and to use the barges only at night. Again, in the early morning of the 15th, PT boats sank four Japanese barges laden with troops heading southeast from Sio. By this time aerial reconnaissance and special patrols had indicated that the following were the most likely barge-staging areas between Madang and Gusika: Marakum, Mindiri, Biliau, Fangger, Gali, Kiari and Sio-Nambariwa.

The Allies’ difficulty in supplying Finschhafen was as nothing compared with the difficulties which the Japanese staff was experiencing in supplying Sattelberg. On 13th, 14th and 15th October submarines were seen moving from Rabaul to New Guinea, but it seemed unlikely that regular and substantial supplies could be carried by them. Barge traffic along the north coasts of New Guinea and New Britain, starting just before dusk, carried most supplies. Mostly the barges unloaded troops at Sio and Sialum Island, whence they moved by tracks to Kalasa for overland movement to Sattelberg, but occasionally the barges ran south as far as Gusika. They would be more likely to take this risk with stores than with troops. From Sio and Sialum there were two main routes to Wareo and Sattelberg: the coastal route from Sio to Gusika taking about five days, and the inland route from Kalasa to Sattelberg taking about four. To supplement their rations the Japanese were forced to gather produce from native gardens, and as their methods usually included pillage and arson, they incurred the hostility of the natives.

“Tac R” reports between 13th and 15th October underlined the probability that the enemy was reinforcing the area. No. 4 Squadron’s report for the 13th and 14th stated that the coastal track was well used and that “it is not considered that inter-village movement would produce such a well defined track”. The report for the 15th stated that “the coastal track north of Lakona to Fortification Point appears to have been used extensively overnight. Black soil well churned up with footprints.”

Warnings of a Japanese attack now began to reach Wootten also from higher formations. At 7.15 p.m. on the 14th he received from Morshead a message which had in turn come from Mackay, to the effect that an intercepted message showed that a Japanese divisional commander had been ordered to attack, at dusk on 16th October, positions from Arndt Point to Langemak Bay. On the morning of the 15th Wootten learnt from Morshead that the principal objectives would be the airfield and PT boats near the mouth of the Mape.

Like Windeyer during the Finschhafen campaign, Wootten was finding the shortage of infantry a constant handicap “not only to offensive and counter-offensive operations, but also to the creation of an adequate

div reserve”.40 By the 15th, however, the remainder of the 2/28th Battalion had arrived at Scarlet Beach. Thus, by 15th October, Wootten had two-thirds of his division in the area; and a signal from Morshead informed him that GHQ had ordered CTF 76 to prepare to move the 26th Brigade from Lae to Finschhafen at 30 hours’ notice. This was indeed heartening news, and contrasted strongly with the protracted negotiations which had been necessary to send the 2/43rd Battalion to Scarlet Beach at the end of September. It was indicative of the gravity of the situation, and of the fact that the various commanders had learned their lesson. Relations between the American air and naval commanders on the one hand, and the senior Australians on the other, were now excellent, and there was little difficulty in securing sympathetic cooperation. The enemy, however, had been given a chance to seize the initiative. Writing to Blamey on 20th October, Mackay stated:

Through not being able to reinforce quickly the enemy has been given time to recover and we have not been able to exploit our original success. Through the piecemeal arrival of reinforcements the momentum of the attack has not been maintained. As was proved in the Lae operations the provision of adequate forces at the right place and time is both the quickest and most economical course.

To the north of the Song two patrols, important in their results, had been made on the 15th. Along the river’s north bank Lieutenant Cavanagh41 led one from the 2/28th Battalion about 3,000 yards west. On the way back at 3.20 p.m. it captured a slightly-wounded Japanese who was carrying a white flag. He later stated that he was a corporal from the I/238th Battalion of the 41st Division. His battalion had moved from Wewak to Lae and Salamaua in August, except for 100 men, of whom he was one, who had arrived in Finschhafen in September, when it was too late to send them on. Forward of Gusika a Japanese officer’s satchel was found after a patrol clash. It contained a copy of an operation order issued on Sattelberg on 12th October by Lieut-General Shigeru Katagiri, the commander of the 20th Japanese Division.

Most Allied Intelligence reports before the landing on Scarlet Beach made a point of emphasising that the loss of Lae and Salamaua destroyed the principal usefulness of Finschhafen to the enemy. In point of fact the loss of Lae and Salamaua made the enemy more determined than ever to hold Finschhafen.

When the Allies began to close in on Salamaua from late July, General Adachi began to send reinforcements to the Huon Peninsula. Under the command of Major-General Eizo Yamada, Colonel Miyake’s 80th Regiment (less its 1 Battalion which was in the Salamaua fighting), the III/26th Field Artillery Battalion, the 7th Naval Base Force and other sub-units – a grand total of about 3,200 troops – left Madang on 23rd August and arrived at Finschhafen on 15th September, one day before the fall of Lae. The 80th Regiment remained at Finschhafen to reinforce the 1,000 troops from assorted units there. Later they were joined by about 1,000 more troops who had been on their way overland from Finschhafen to Lae when Lae fell. Thus

a force of over 5,000 Japanese troops was in the general Finschhafen-Mongi River area when the 20th Brigade landed behind them at Scarlet Beach. Parts of all three Japanese divisions of the XVIII Army were in the Finschhafen area on 22nd September. As well as the 80th Regiment of the 20th Division, there were portions of the 238th Regiment of the 41st Division, which, like the I/80th Battalion, had been sent to Salamaua, and even the battered company of the 102nd Regiment of the 51st Division which had first met the Allies at Nassau Bay.

“With the cooperation of the Navy,” stated General Imamura’s order from Rabaul on 20th September, “the essential places of the Dampier Strait and Bougainville Island will be held. The Army, Navy and Air Forces will combine their strength to eliminate the enemy on land and sea.” In order to carry out this intention it was necessary to send more troops to Finschhafen. Little could be expected from the broken 51st Division, the remnants of the I/80th Battalion, and the main portion of the 238th Regiment now retreating over the Saruwaged Range to the north coast. Thus, the main body of Katagiri’s 20th Division departed from Madang by land and sea on 15th September. The 79th Regiment, 3,196 troops, comprised the majority. As the task of opposing the 7th Australian Division was being undertaken by the 78th Regiment, Katagiri would have in the Finschhafen area his 79th and 80th Regiments and the equivalent of another regiment from the various sub-units and reinforcements in the area. The equivalent of a division of Japanese would soon be in the Finschhafen area.42

It can thus be seen how narrow was the margin between victory and defeat in the battle for Finschhafen. The 20th Japanese Division was already on the way to Finschhafen when the 20th Australian Brigade, one-third its size, landed ahead of it, and secured a foothold on the east coast of the Huon Peninsula. Bold planning, determined fighting, skilful generalship and luck had combined to give the Australians at Finschhafen a good chance of weathering the storm which they now knew was gathering at Sattelberg.

When Adachi learnt of the landing at Scarlet Beach he ordered the 80th Regiment to occupy the Sattelberg feature until the arrival of the rest of the 20th Division when an attack would be launched on Finschhafen. When the attempt was made on 26th September by Lieut-Colonel Takagi’s III/80th Battalion to attack east along the Sattelberg and Katika Tracks but was beaten back, Colonel Miyake, of the 80th Regiment, decided to wait until more of his force arrived from the Logaweng area before renewing the attack at the end of September. When this attack, in its turn, made no real progress the Japanese decided to wait for the larger number of reinforcements from the north.

Hearing of the Australian landing at Scarlet Beach General Katagiri hastened his advance. It had been intended that all of this force would arrive by 25th October, but now they pressed ahead as fast as their physical condition and the difficult terrain would permit. By the 10th, Katagiri and part of his force had arrived in the Sattelberg area. The main body, including most of the 79th Regiment, came to Sio and Sialum by barge and then marched to Kalasa and Sattelberg along

the inland track. Other units and sub-units, including the headquarters of the 26th Field Artillery Regiment and the II/26th Field Artillery Battalion, marched with the 79th Regiment. The 5th Shipping Engineer Regiment, from 23rd September onwards, aided the 9th Shipping Engineer Regiment, which was already carrying stores along the coast. Because of the transport difficulties the artillery were able to take with them only six mountain guns.

Along the overland route from the north coast members of the 79th Regiment had seen survivors of the 51st Division from Lae and Salamaua struggling north in small groups. They were starving and in pitiful condition, but the 79th Regiment either would not or could not give their miserable comrades any rations. During October what was left of the 51st Division arrived at Kiari, and, after recuperating and reorganising, took up defensive positions there to strengthen the rear of the 20th Division.

Thus the Australian and Japanese divisional commanders arrived in the Finschhafen area at the same time. General Wootten’s orders for a resumption of the offensive were issued on 11th October, and General Katagiri’s orders for a counter-attack on the following day.

“After dusk on X Oct,” stated Katagiri’s order, “the main strength of 79th Infantry Regiment will attack the enemy in Arndt Point area from the north side. The assault boat Butai will penetrate through the north coast of Arndt Point on the night of X-day.”

The order continued that the commander of the II/26th Artillery Battalion, with two companies of the I/79th Battalion, would destroy the enemy in the northern sector by occupying the Bonga area by the evening of 14th October.

Katagiri’s attack was to be three-pronged. First, there would be a diversion from the north by the II/26th Artillery Battalion and portion of the I/79th Battalion. Secondly, a seaborne attack by 10 Company of the 79th Regiment which had been left behind at Nambariwa, supported by a detachment of the 20th Engineer Regiment with explosives and demolition charges, would take place “on the night of X-day”. Instructions to this “Boat Penetration Tai” were that “ammunition dumps, artillery positions, tanks, enemy HQ, moored boats, barracks, etc. should be selected as objectives”. Thirdly, the main attack from the west would be made by the 80th Regiment astride the Sattelberg Road towards Heldsbach and the artillery positions, and the 79th Regiment to the north with the object of destroying the enemy north of Arndt Point.

“X-day,” stated Katagiri’s order, “will be decided on X-minus-1-day at 2200 hrs and a fire will be seen for 20 minutes on the Sattelberg heights. When the fire is seen answer back at a suitable spot (by fires).”

The information which General Wootten had received from higher formations about signs of an impending attack had given no clear indication as to the probable nature or direction of the attack. Even before the capture of General Katagiri’s order on the afternoon of 15th October, however, he had changed his plans in order to fight a defensive battle. After a conference with senior commanders on the morning of the 15th be issued an operation order stating that “indications are that the enemy may counter-attack towards either or both Finschhafen airfield and Langemak Bay” by sea or land or a combination of both. It can thus be seen that on the 15th the Australians were not clear as to where the main Japanese attack would occur, except that they thought it would be in the southern sector. Windeyer was ordered to coordinate the defence of Langemak Bay and “hold important ground at all costs”, defend in depth,

maintain a mobile reserve, and organise coastwatching stations and beach defences. Wootten ordered that the ground to be held should include the track junctions in the Bonga area, North Hill, the high ground about two miles west of Scarlet Beach between the Song and Jivevaneng, Kumawa, Tirimoro, Butaweng, Logaweng and the 532nd EBSR base at Dreger Harbour.

Two companies of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion were placed under Windeyer’s command and one under Evans’. Light anti-aircraft guns were given an extra role of beach defence, extra guns were sited to protect the beaches, infantry 2-pounder guns were sited along the coast, and coast-watching stations were established. When the 2/32nd Battalion arrived on 15th October, it and the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion less three companies became the divisional reserve.

Then came news of the translated document – an even more important document than the Japanese evacuation order captured by the 7th Division four days before the capture of Lae. Thereupon, at 3.35 p.m., Wootten instructed Evans to “site and hold at all costs a post north of River Song on direct track running through 620700 to Wareo, which track possible axis of enemy land attack”. This was the only redisposition considered necessary by Wootten as a result of the capture of the plan of attack.

As rain fell and the mists came down, anxious Australian eyes were turned to the western mountains where Sattelberg heights faded into the dusk. Wootten’s instructions were clear: “All units whose location permits will establish lookouts to report immediately ... the lighting of any fires at night on Sattelberg heights and any answering fires.”