Chapter 28: To Morotai and the Palaus

WHILE the Australian offensive was in progress the planning of future Allied operations in the Pacific had gone far ahead – as far as the Philippines and the Marianas. In August 1943 at Quebec Mr Churchill, President Roosevelt and their staffs had held their first conference since the one at Washington in May. The Chiefs of Staff arrived on the 12th, Churchill and Roosevelt on the 17th. On the 15th Marshal Badoglio, the Italian commander, opened negotiations to surrender and join the Allies; and recently the Russian Army had opened an offensive which was making spectacular progress. Once again the Pacific area was in the background of a conference at which crucial decisions were made about other theatres. The target date for the invasion of western Europe (1st May 1944) was confirmed; it was decided to establish an Allied South-East Asia Command with Lord Louis Mountbatten in command; certain specific operations in the Pacific in 1943-44 were approved in principle.

In the discussion of future operations in the Pacific the British representatives asked whether operations in New Guinea should not be curtailed and the main effort made in the Central Pacific. Admiral King would have preferred this, but the Americans presented a solid front and insisted on continuing a dual advance.1

Finally the conference approved the American program. In the Central Pacific this included the seizure of the Gilberts, the Marshalls, Ponape and Truk, and either the Palaus or Marianas or both. MacArthur’s plans to take Rabaul were not approved. His task for the next 16 months was to gain control of the Bismarck Archipelago, neutralise Rabaul, capture Kavieng, the Admiralties and Wewak, and advance to the Vogelkop in a series of “step by step airborne-waterborne operations”.

MacArthur was not happy about some aspects of the Quebec decisions. The failure to define any role for his forces after the Vogelkop had been reached would, he argued, have an adverse effect on his own staff and might lead to a let-down of the Australian war effort. General Marshall thereupon asked MacArthur to plan also for a move into the Philippines.

Consequently on 20th October MacArthur’s staff produced a new outline plan RENO III. As before, the general object was to advance the bomber line northwards to the Philippines by the occupation of widely spaced bases along the north coast of New Guinea. In the first phase Hansa Bay would be occupied on 1st February, and then Kavieng (by South Pacific forces) and the Admiralty Islands (by South-West Pacific forces) on 1st March. These operations would provide air bases from which the neutralisation of Rabaul could be completed. In the second phase advances would be made along the New Guinea coast to the

Hollandia area and in the islands of the Arafura Sea South-west of New Guinea. The aim of the advance into the Arafura was to protect later movements to the Vogelkop Peninsula. By moving to Hollandia MacArthur would bypass the strong Japanese forces at Wewak but his own forces were to infiltrate eastward towards Wewak from Aitape. In the third phase MacArthur’s forces would advance to Geelvink Bay and the Vogelkop, beginning on 15th August 1944. In the fourth phase airfield sites would be captured in the Halmaheras or Celebes. If necessary for flank protection Ambon to the south and the Palaus to the north would also be taken. These operations were to start on 1st December 1944. On 1st February 1945 the final phase, the invasion of Mindanao, would open.

A decision whether Admiral Nimitz’s advance should turn northwards through the Marianas and Bonins towards Japan depended on two main considerations. One was that an operation against Truk seemed likely to precipitate a decisive fleet action and, from the middle of 1944 onwards, the Pacific Fleet was so strong that it would welcome such an action. It was decided that strong carrier attacks should be undertaken to test the strength of Truk, the final decision whether to attempt to capture it or not to depend on the result. The other consideration was how to employ the big B-29 bombers (Superfortresses) now being produced in large numbers. At first it had been planned to use B-29’s to bomb Japan from airfields in China but General Arnold was not confident that the Chinese could hold these airfields. On the other hand, Saipan and Tinian in the Marianas were closer to Tokyo than were the airfields in China. Admiral King also favoured the plan to advance by way of the Marianas.

In November and December 1943 the British and American leaders and staffs met twice at Cairo, where the Combined Chiefs reaffirmed the principle established by the American Joint Chiefs that where conflicts of timing and requirements existed between the Central and South-West Pacific areas the claims of the Central Pacific should take precedence. This was the culmination of the discussion concerning the respective advantages of the South-West Pacific and the Central Pacific routes to Tokyo. The Joint Chiefs believed that the Central Pacific route was “strategically, logistically, and tactically better than the South-West Pacific route”, but, as mentioned, decided that they should continue to advance along both axes. It would be wasteful to transfer all their forces to the Central route and the use of both routes would prevent the enemy from knowing where the next blow would fall. Thus, in the next phase, there would be a main offensive in the Central Pacific,. carried out chiefly by the American Navy and Marines, and a secondary offensive in the South-West Pacific, carried out by Allied army forces with such naval support as was appropriate.

As an outcome of these deliberations and decisions Nimitz’s staff on 13th January completed a new time-table. His forces would move into the eastern Marshalls about 31st January; the carrier attack on Truk would be made late in March; in May his forces would advance into the western Marshalls; and on 1st August would be ready either to invade

Truk or to bypass it and move directly to the Palaus. The first landings in the Marianas would take place about 1st November.

At the same time MacArthur’s staff elaborated their plans. The operations against Manus in the Admiralties and Kavieng, hitherto scheduled for 1st March, were moved on to 1st April, partly as a result of the inability of the Pacific Fleet to provide support on the earlier date.

On 27th and 28th January officers of the South-West Pacific, the South Pacific and the Central Pacific Commands conferred at Pearl Harbour to coordinate details for the forthcoming operations. It was agreed that Truk could be bypassed, but that the Palaus should be taken by the Central Pacific forces to protect the right flank of the South-West Pacific advance along the New Guinea coast. Nimitz now put forward a revised time-table: the invasion of the eastern and central Marshalls on 1st February and the western Marshalls on 15th April; and if the proposed carrier attack on Truk drove the Japanese carrier fleet westward it might be possible to bypass Truk, take the Marianas about 15th June and invade the Palaus early in October.

The Japanese leaders had also made plans for the next phase in the Pacific. They decided to concentrate on a defensive front through Timor, the Aru Islands, the Wakde-Sarmi area 125 miles North-west of Hollandia, the Palaus and the Marianas. Thus not only the Eighth Area Army round Rabaul but the XVIII Army falling back on Wewak and the forces at the base at Hollandia were now forward of the main front. The Japanese plan was not, however, purely defensive. On 8th March orders were given that when the American Fleet entered the Philippine Sea the Japanese Fleet would attack and annihilate it. It had always been the Japanese leaders’ intention to seek a decisive naval engagement. They had done so at Midway, but had not been able to make a second attempt sooner because of heavy losses of carrier-borne aircraft pilots there and in the Solomons. By April 1944, however, they would have a first-line strength of about 500 well-manned carrier aircraft.

Before the long-range Allied plans could be carried out, however, there was work to be done round New Guinea. With the Huon Peninsula firmly in Australian hands, the divisions of the XVIII Army in retreat towards Wewak, and an American air base established at Torokina on Bougainville, the time had come to complete the isolation of Rabaul. This was to be achieved in four moves: first, seizure of western New Britain thus gaining control of the straits between that island and the mainland of New Guinea; second, seizure of the Green Islands; third, seizure of the Admiralty Islands where naval and air bases would be established well to the rear of the Eighth Area Army’s actual “front” which ran more or less from Wewak, through the Madang area and New Britain to Bougainville; fourth, seizure of Kavieng in New Ireland.

Since October a concentrated air offensive against Rabaul had been in progress. General MacArthur’s plan was to occupy the western part of New Britain along a general line Gasmata–Talasea. Command of this operation was given to General Krueger of the Sixth American Army. While the New Britain operation was being planned a group of coast-watchers was at work in the Cape Orford area. These included Lieutenant

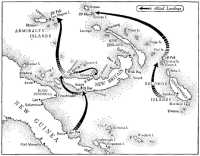

American operations in the South-West Pacific, December 1943–March 1944

Wright2 (RANVR), Captain P. E. Figgis and Lieutenant Williams.3 In September, well in advance of the invasion, it was decided to establish a more elaborate organisation to give warning against possible air attacks from Rabaul: the Cape Orford post was to be retained and others set up near Gasmata and on Open Bay, on Wide Bay, and near Cape Hoskins. On 28th September 16 Europeans and 27 natives were landed by a submarine which was signalled in by Wright. Wright led the Cape Hoskins party, Captain J. J. Murphy the Gasmata party, and Captain Skinner4 the one to Open Bay. Each had a line of native carriers. Murphy’s party

met disaster. A native led a Japanese patrol to them and in the ensuing fight two Australians were killed and Murphy captured. The other parties reached their positions and reported air and barge movements during the subsequent operations.5

After much discussion and some changes of plan MacArthur ordered, late in November, that a landing be made at Arawe on the South-west coast on 15th December and that the main attack, on Cape Gloucester, be made on the 26th. The Arawe landing was made by the 112th Cavalry Regiment (Colonel Alexander M. Miller). At a subsidiary landing place the Japanese were ready and opened fire on rubber boats carrying a covering party of 152 troopers, sinking 12 out of 15 boats and preventing any landing. The main landing, in amphibious tractors, was carried out in some confusion but the enemy were weak and the objectives were taken with few losses.

At Cape Gloucester Major-General William H. Rupertus’ 1st Marine Division had the task of landing on two main beaches and making a diversionary landing on a third. About 1,000 Japanese were in the area with about 9,000 more elsewhere in western New Britain. They belonged to the 17th Division and 65th Brigade. In the first day 12,500 American troops and 7,600 tons of equipment were ashore, and, on the 30th, the airfield was taken. The hardest fighting occurred in the next two weeks during which the Americans dislodged the defenders from heights to the east within artillery range of the airfield. In mid-January serious Japanese resistance ended, after some 3,000 of them had been killed; the marines lost 248 killed.6

The next step was an easy one: to occupy the Green Islands between Buka Island and Rabaul and establish an advanced air and torpedo-boat base there only 117 miles from Rabaul. The task was allotted to the 3rd New Zealand Division. Motor torpedo-boats from Torokina reconnoitred the waters round the Green Islands on the night of the 10th–11th January, and on the night of the 30th–31st a raiding force of 322 New Zealanders accompanied by Lieutenant Archer,7 a former plantation owner and coast-watcher of Buka, landed and examined Nissan, the largest island of the group, without encountering any of the 100 Japanese there, except at one point where a landing craft came under fire from a camouflaged Japanese barge and four men were killed. Next night this reconnaissance force was withdrawn. On 15th February Major-General Barrowclough with divisional troops and the 14th New Zealand Brigade landed on Nissan where they found no Japanese that day. On the third day a company group was landed on a near-by island, where natives reported that Japanese had taken refuge, and in a sharp engagement killed all 21 of them. The few Japanese on Nissan proper were found on the 20th and destroyed that day. The final clash took place on an adjoining island on

the 23rd. When it was over 120 Japanese had been killed for a loss of 10 New Zealanders and three Americans.8

This was the last major task of the 3rd New Zealand Division, which had proved itself an excellently trained amphibious division. It was impossible for New Zealand, with a population of only 1,600,000, to maintain two divisions in action in addition to an air force which in December 1943 numbered 38,000. In 1944 the 3rd Division was disbanded, many of its members going to Italy to reinforce the 2nd New Zealand Division there.

A reconnaissance aircraft, after flying low over the Admiralties on 23rd February, reported that no signs of Japanese occupation could be seen, although the Intelligence estimate was that there were 4,600 Japanese in the group. This greatly interested General Kenney, who proposed to General MacArthur that he should make a reconnaissance in force as soon as possible. MacArthur agreed, and on the 24th instructed General Krueger to land a strong reconnaissance force of not more than about 1,000 men of the 1st Cavalry Division in the vicinity of Momote airstrip on Los Negros Island, not later than 29th February. The force was to be withdrawn if the resistance was too heavy.

On 27th February, two days before the proposed landing, Krueger sent six scouts on to Los Negros to test the accuracy of the air report. Early that morning they were landed in a rubber boat from a Catalina, and that afternoon sent out a message that the island was “lousy with Japs”; next day the party was taken off. Thus MacArthur’s change of plan had been based on evidence that was slender at the outset (merely that no Japanese activity had been visible when aircraft flew overhead) and had now been proved to be inaccurate. However, the operation was not delayed.

Admiral Barbey of the Seventh Amphibious Force was in command of the landing operation. The naval attack group consisted of 8 destroyers and 3 APDs carrying a force under Brigadier-General William C. Chase, about 1,000 strong including the 2nd Squadron of the 5th Cavalry Regiment, with artillery and other supporting detachments. The 1st Cavalry Division (Major-General Innis P. Swift), the only formation of its kind in the United States Army, was originally a Regular formation and, although in the rapid expansion of the army in 1941 it had taken in raw recruits until they totalled 70 per cent of its strength, it was probably the most capable division of the American Army which had yet been in action in the South-West Pacific.9

The attacking force arrived off Hyane Harbour before dawn on the 29th, escorted by cruisers and destroyers. There was little opposition on the beach. In fact the Japanese defences were pointing the wrong way,

The attack on Los Negros, 29th February to 4th March

having been deployed to meet a landing in the spacious Seeadler Harbour on the west side of Los Negros. By 9.50 the cavalrymen had occupied an arc about 4,000 yards in extent enclosing Momote airstrip. At 2 p.m. MacArthur came ashore and ordered Chase to maintain his hold on the island. In the evening Chase decided to pull his troops back to a shorter line of about 1,500 yards enclosing the neck of the peninsula at the southern end of the harbour and there await the probable counter-attack.

A detachment of 25 Angau officers and men and 12 native police of the Royal Papuan Constabulary were with the attacking force. Of these the commanding officer, Major J. K. McCarthy, Lieutenant Hoggard,10 Warrant-Officers A. L. Robinson and Booker11 with four Papuan constables landed with the 2nd Squadron on the morning of the 29th. The task of the Angau party in the early stages was to collect information and guide patrols, in the later stages to administer the natives. On the first day Booker, an outstanding scout, led a patrol including 10 American troops and one Papuan through the Japanese lines and penetrated a mile and a half to the south, finding dumps, trenches and pill-boxes, capturing many documents and destroying weapons. Robinson, in the first few days, patrolled through the enemy’s lines with two men of the Royal Papuan Constabulary on four occasions and each time brought back valuable information.

Colonel Yoshio Ezaki, the Japanese commander, ordered his troops on Manus to annihilate the invaders. That night they made a poorly-coordinated attack, but infiltrated dangerously into the American lines. The attack was resumed next day, and on the night of the 1st–2nd March reached its greatest intensity, but heavy and steady American fire halted

the Japanese with calamitous losses. McCarthy counted 75 dead Japanese in a single revetment next morning, and considered that this night attack was “the last serious attempt by the enemy at organised resistance”.

American reinforcements arrived on the 2nd, and by 4 p.m. were dug in on the western edge of the strip. Booker with one Papuan patrolled the Skidway, a narrow causeway leading north towards Seeadler Harbour, penetrated the enemy’s lines and reached the Japanese beach-head at Salami Plantation on Seeadler Harbour.

The Japanese attacked on the night of the 2nd–3rd and again lost heavily. Next day the Americans again enlarged their perimeter a little and that night the Japanese attacked once more; a total of 750 of their dead had now been buried. The Japanese on Los Negros had exhausted their strength whereas the American force was regularly being reinforced. On the 6th the cavalrymen, following the route of Booker’s patrol of the 2nd, reached the shores of Seeadler Harbour. Mopping-up continued. On the 7th a Mitchell bomber was landed on Momote strip, and on the 9th Wing Commander Steege12 of No. 73 Wing RAAF, with 12 Kitty-hawks of No. 76 Squadron, landed on Momote; 12 more Kittyhawks landed next day.

The task remained of capturing the airstrip at Lorengau on Manus. It was decided to cover a landing there with guns sited on two islands off Lorengau, one of which – Hauwei – was occupied. There 26 men, including Warrant-Officer Robinson and a local native, landed from a barge but soon were under heavy fire. The landing craft was sunk while trying to re-embark the patrol, but the 18 survivors swam until they were picked up by a PT boat – except the native, Kiahu, who swam from island to island, and reached Seeadler Harbour that afternoon. Robinson swam for five hours supporting a wounded American before they were picked up. Next day a whole squadron landed covered by naval gunfire, field guns and Kittyhawks and captured Hauwei.

On 15th March the 8th Cavalry made a shore-to-shore landing near Lorengau. The cavalrymen pushed eastward slowly and secured the airstrip on the 17th and Lorengau village on the 18th. By the 16th some 900 Australians of the ground staff of No. 73 Wing and its attached units had landed at Momote and a well-provided forward air base in the Admiralties was in being. By 18th May 3,317 Japanese had been buried. The American force lost 330 killed and 1,189 wounded.13

At the time of the attack on the Admiralties the plan was that on 1st April the South Pacific forces would attack Kavieng. Admiral Halsey, however, convinced that the effective air onslaughts on Rabaul had made the capture of Kavieng unnecessary, wished instead to take Emirau Island, conveniently situated between Kavieng and Manus.

The acceleration of the advances by both Nimitz’s and MacArthur’s forces made revision of the Joint Chiefs’ directives urgently necessary. Early in February MacArthur had sent General Sutherland to Washington to advocate his plan to concentrate all Pacific forces along the New Guinea axis, bypassing both Truk and the Marianas. Later Nimitz and some of his staff arrived to discuss the future. Nimitz presented a revised schedule which provided for landings in the Marianas on 15th June, the capture on 15th July of Woleai in the Carolines (to protect his lines of communication), the seizure of the Palaus from 1st October, and of Ulithi Atoll (which he needed for a fleet base in substitution for Truk) as soon as possible thereafter.

Meanwhile Sutherland also presented a revised plan which provided that in the first phase Hansa Bay should be bypassed and two divisions supported by carriers of the Pacific Fleet should land in the Hollandia area on 15th April. Subsequent advances would be supported from Hol-landia or from other air bases which MacArthur’s forces would occupy as they moved forward. The Geelvink Bay area would be occupied on 1st June. In the second phase, beginning on 15th July, three divisions would seize the Arafura Sea islands whence air forces would cover the advances to the Vogelkop and Halmaheras and attack targets in the Indies. In the third phase operations against the Vogelkop and Halmaheras would open on 15th September. Mindanao would be invaded on 15th November and Luzon in March 1945. The joint planners at Washington disagreed in part with both Nimitz’s and MacArthur’s proposals.

At length, on 12th March, the Joint Chiefs issued a new directive.

Reaffirming their belief that Allied strength in the Pacific was sufficient to carry on two drives across the Pacific, the Joint Chiefs’ directive was, in effect, a reconciliation among conflicting strategic and tactical concepts. The Joint Chiefs took into consideration the Army Air Forces’ desire to begin B-29 operations against Japan from the Marianas as soon as possible; Admiral King’s belief that the Marianas operation was a key undertaking which might well precipitate a fleet

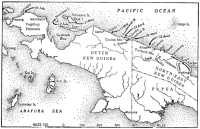

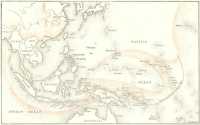

Operations along the north coast of New Guinea

showdown; the knowledge concerning the weakness of Truk gained during the February carrier attacks; the proposals offered by various planners concerning the feasibility of bypassing Truk; Admiral Nimitz’s belief that the occupation of the Palaus and Ulithi was necessary to assure the neutralization of Truk and to provide the Pacific Fleet with a base in the western Pacific; and, finally, General MacArthur’s plans to return to the Philippines as early as possible via the New Guinea-Mindanao axis of advance.

The Joint Chiefs instructed General MacArthur to cancel the Kavieng operation, to complete the neutralization of Rabaul and Kavieng with minimum forces, and to speed the development of an air and naval base in the Admiralties. The Southwest Pacific’s forces were to jump from eastern New Guinea to Hollandia on 15 April, bypassing Wewak and Hansa Bay. The Joint Chiefs stated that the principal purpose of seizing Hollandia was to develop there an air center from which heavy bombers could start striking the Palaus and Japanese air bases in western New Guinea and Halmahera. After the occupation and development of the Hollandia area, General MacArthur was to conduct operations northwest along the northern New Guinea coast and “such other operations as may be feasible” with available forces in preparation for the invasion of the Palaus and Mindanao. The target date for the Southwest Pacific’s landing in the Philippines was set for 15 November.14

Nimitz’s forces would occupy the Marianas from 15th June (as he had proposed) and the Palaus from 15th September. The proposal to occupy Emirau was accepted in Washington and on 20th March four battleships, accompanied by two small aircraft carriers and fifteen destroyers, bombarded Kavieng as though in preparation for a landing, while the 4th Marine Regiment landed instead on Emirau, without opposition. Emirau was rapidly developed as a torpedo-boat base and airstrips were constructed.

Meanwhile the advance of Admiral Nimitz’s Central Pacific forces into the Marshall Islands had begun. An immensely strong naval force was assembled to support the operations. It included three fast carrier groups each of three carriers and three battleships and 297 other warships and transports. The troops numbered 54,000 and included the 4th Marine Division and 7th (Army) Division. The plan was to occupy first an undefended atoll, Majuro, to provide an anchorage for supply vessels, and next day to attack the big Kwajalein Atoll; Eniwetok was to be attacked soon afterwards; other defended atolls in the Marshalls were to be bypassed. Kwajalein is an elongated coral atoll enclosing an area of 839 square miles, but only three islands or pairs of islands in the long chain were big enough to house a large military base. The plan was simultaneously to attack two of these – Roi-Namur in the north (with the 4th Marine) and Kwajalein in the south (with the 7th). About 3,700 Japanese defended Roi-Namur, about 4,500 Kwajalein Island.

Majuro was occupied on 31st January – the first Japanese territory to be occupied in the war. Roi-Namur was bombarded for three days and nights before the landing on 1st February, about 6,000 tons of shells and bombs being thrown into an area about a mile and a quarter long and half a mile wide. The landing ships entered the lagoon and the attack was launched against the inner shore of Roi-Namur. On Roi the defenders seemed dazed by the bombardment; the marines were on the objective in 20 minutes and were opposed by only 300 Japanese in wrecked blockhouses and among rubble on the north. Organised resistance ceased on the second day.

From 30th January onwards Kwajalein Island was heavily bombarded, about 5,600 tons of projectiles being used. On 1st February the 7th Division landed in perfect formation and secured the beach-head before organised resistance began. This was strong, however, and it was 4th February before resistance was subdued. This southern force killed 4,398 Japanese and lost 177 of its own men; the northern force killed 3,472 and lost 195. The heavy losses suffered at Tarawa had been avoided by intense and prolonged bombardment.

The next target was Eniwetok, a circular atoll with a radius of about 12 miles lying 326 miles west-North-west of Roi-Namur. On 16th and 17th February the Americans occupied several islets on the north side of the ring of coral islands and on the 19th a regiment of the 27th Division was launched against Eniwetok Island proper. There were some 800 Japanese there, but they had concealed themselves and it was not until the last moment that the attackers knew that Eniwetok was defended, and consequently the preliminary bombardment had not been heavy. The infantrymen got ashore successfully but made slow progress and a battalion of marines was sent in. Such intimate cooperation between American marines and army units was difficult because of their different tactical doctrines, and the situation on Eniwetok caused the historian of the United States Navy to offer the following comment, specially interesting from an Australian point of view because Australian troops had

found that their doctrines differed from those of the American Army in very much the same way.

The marines consider that an objective should be overrun as quickly as possible; they follow up their assault troops with mop-up squads which take care of any individuals or strong points.15

Resistance ended on Eniwetok on the 21st. Then the 22nd Marine Regiment landed on Parry Island, which was garrisoned by about 1,300 Japanese. Parry had been subjected to a thorough bombardment, and after a day of bitter fighting the Japanese resistance ceased. In the whole Eniwetok operation the Americans lost 195 killed and 2,677 Japanese died; only 64 became prisoners.

Thus by the end of March the Japanese armies in New Britain and the Solomons had been isolated, the American Central Pacific forces from the east had established themselves on Japanese island territory at Kwajalein and Eniwetok, and in New Guinea the XVIII Japanese Army was in retreat to Wewak. Nearly all the six Japanese divisions deployed on the South-West Pacific front had suffered heavily and were now practically cut off from any supplies except what submarines might bring them. Meanwhile, however, between December 1943 and April 1944 the Japanese had brought fresh troops forward to the new defensive line mentioned earlier: in the Carolines and Marianas the XXXI Army now included the 14th, 29th, 43rd and 52nd Divisions; in western New Guinea, as mentioned, the II Army had the 32nd, 35th and 36th Divisions. In the whole area east of Java there had been, in November 1943, nine Japanese divisions (and other smaller formations). There were now 17, five of the new divisions having been drawn from Manchuria and North China and three from Japan.16

The isolated Japanese forces to the south did not intend, however, to remain inactive if they could avoid it. As mentioned earlier, within the 14-mile perimeter round Torokina on Bougainville was General Gris-wold’s XIV Corps (37th and Americal Divisions). Outside it was a Japanese force of some 45,000 troops and 20,000 naval men. General Hyakutake of the XVII Army decided to drive the Americans into the sea. The offensive was launched on 9th March by 15,000 men supported by 10,000 employed in rear echelons, and particularly in carrying supplies. It made little progress, and later attacks from 12th to 24th March met no better success. The American force lost 263 killed and the Japanese perhaps 7,000-8,000. It was a severe defeat, but nevertheless the Japanese force continued to detain an American corps of two divisions defending the Torokina perimeter, not counting a third division garrisoning the outlying islands.

The next Allied step – the seizure of Aitape and Hollandia – would be the most ambitious amphibious operation yet undertaken in the South-West Pacific. Not only was the force to be employed – some 80,000 men

including two divisions – the largest yet carried forward in an assault phase, but the objective was 425 miles beyond the forward positions, round Bogadjim, and part of the force was embarked 1,000 miles from the objective. In one move a longer advance would be achieved than that which had been made on the New Guinea mainland in the previous 18 months of foot-slogging and coastwise movements.

In the Hollandia area MacArthur’s first objective was Humboldt Bay, the only first-class harbour on the north coast. Above it the Cyclops Mountains rose steeply, and, six miles west of the bay and near the foot of the range, lay Lake Sentani, about 15 miles in length, near which the Japanese had made three airfields. A track led to this area from Tanahmerah Bay 25 miles west of Humboldt Bay.

Since the supporting aircraft carriers could remain for only a limited time and Hollandia was 500 miles from the nearest big air base, at Gusap, it was decided to capture a Japanese airfield at Tadji near Aitape, 125 miles to the east in Australian New Guinea. Possession of Aitape should also enable the invading force to prevent the Japanese XVIII Army at Wewak from moving westward. MacArthur decided, therefore, to land forces at Tanahmerah and Humboldt Bays and Aitape simultaneously on 22nd April.17

The advance into Dutch New Guinea would carry MacArthur’s forces into country less developed than Australian New Guinea and less well known by Europeans. In the Australian territories before the war there were some 6,200 Europeans (hundreds of whom were now in Angau, the “cloak and dagger” forces, and the native battalions) and about 50,000 indentured labourers were employed; in Dutch New Guinea the European population was only about 200 in approximately the same area. Dutch New Guinea, the Dutch administrative officers used to say, was “a colony of a colony”, and its great natural resources had hardly begun to be exploited. It would be difficult to find Netherlanders with knowledge of the areas now to be attacked.

Hollandia was in territory known to few Australians, but it was decided that a party of veteran Australian scouts should reconnoitre the area. Captain G. C. Harris, who had served behind the Japanese lines for about a year on the Rai Coast and in New Britain and had reconnoitred Finschhafen before the invasion, was chosen as leader. There were six Australians, four New Guinea soldiers and an Indonesian interpreter. They were to be landed at Tanahmerah Bay by submarine, make a deep patrol and be picked up again by submarine 14 days later. An American submarine landed the party on the night of 23rd March.

The rubber boat carrying a reconnaissance party of five was swamped and their walkie-talkie was ruined. They found they had come ashore near a native hut whose four occupants seemed untrustworthy. Harris flashed a signal to the submarine not to send the remaining men ashore, but it was misunderstood, and they landed, their boats being overturned as the other had been. In the morning Harris’ party set off inland. It was learnt later that the natives informed the Japanese as soon as they left the beach. Next morning a strong party of Japanese armed with machine-guns and mortars caught up with them. The Japanese opened fire and the Australians fired back. Harris who was wounded waved to Able Seaman McNicol18 to escape to the south. At length all the Australian party had withdrawn except Harris and Privates Bunning19 and Shortis20 who kept up an accurate fire against the Japanese and drew the whole enemy force to them. “The three kept up the action for four hours, until Bunning and Shortis lay dead and Harris, alone, wounded in three places, faced the enemy with an empty pistol. Then they rushed him.”21 The Japanese propped Harris against a tree and questioned him. He was silent. At length they bayoneted him. The Indonesian escaped, was helped by a friendly native and remained in the area until American troops landed. Lieutenant Webber22 and Private Jeune23 walked east and south for five days then decided to remain where they were and try to survive until the landing. After three weeks with very little food they heard the bombardment and began to make their way to the beach. The two men, almost too weak to walk, encountered a Japanese whom they killed in a hand-to-hand struggle. That afternoon they limped on until they met some American soldiers. McNicol and a native sergeant, Mas, lived in the bush for 32 days, almost starving, until the landing. The sergeant was too weak to move. The emaciated McNicol reached the Americans but a patrol sent out to rescue Mas could not find him. Sergeants Yali and Buka set out to walk east to join the nearest friendly troops. As far as they knew these were at Saidor, 400 miles away. Buka became too ill to walk and Yali, having left him while he reconnoitred, and having met Japanese troops and run some distance to escape from them, could not find him again, though he searched for two days. At length Yali reached Aitape, 120 miles from his starting point. Eight months later the last of the five survivors, Private Mariba, who had been captured, escaped and made his way to Allied lines.

The landing at Aitape was made on 22nd April by the 163rd Regimental Combat Team, which had fought at Sanananda in 1943. The Japanese strength, estimated to be 2,000 was in fact about 1,000, of whom only 240 were fighting men, and there was little opposition. The Americans lost only 2 killed and 13 wounded. Within 48 hours No. 62 Works Wing, RAAF, had the Tadji airfield ready for the Kittyhawks of No. 78 Wing RAAF. On 23rd April the 127th Regiment (of the 32nd Division) landed, and during May the remainder of the division arrived, relieving the 163rd Regiment for another task.

The Hollandia operation was commanded by General Eichelberger of I American Corps, which included the 24th Division and the 41st, less one regiment. The Japanese strength was estimated at from 9,000 to 12,000. The 24th Division landed at two points in Tanahmerah Bay on the 22nd and immediately the lack of knowledge of Dutch New Guinea became evident. The main landing beach proved to be skirted by impassable swamps, the secondary one to be fringed by coral which made it impossible to beach the craft except at high tide. Troops were transferred from the main to the secondary beach; fortunately the landings were not opposed; and by nightfall patrols had been eight miles inland. Next day Eichelberger and Barbey decided to transfer the main effort to Humboldt Bay.

There on the 22nd the 41st Division had landed on two beaches. The defenders fled and by 26th April the airfields had been occupied. The subsequent mopping-up lasted until 6th June. To that time the Hollandia operation had cost the Americans 159 killed; some 3,300 Japanese were killed and 611 surrendered – a surprising happening never repeated on the same scale in 1944, and probably due to the fact that the 11,000 Japanese in the area were practically all base troops. Indeed, General Adachi had expected the attacks to fall at Hansa Bay and Wewak, and, when the landings took place, the 41st Japanese Division was round Madang, facing the 5th Australian Division, and the 20th and 51st moving towards Wewak and But, one regiment of the 20th being under orders to move to Aitape. Thus in a few days at a cost of 161 Allied troops killed the XVIII Japanese Army was isolated and the main Japanese base east of the Vogelkop occupied. It was a classic illustration of the advantages of possessing command of the sea, and the air above it.

The Hollandia area was swiftly converted into an immense military and air base.

Road construction had proceeded simultaneously [with building runways], and this was a gigantic task. Sides of mountains were carved away, bridges and culverts were thrown across rivers and creeks, gravel and stone “fill” was poured into sago swamps to make highways as tall as Mississippi levees. ... Hollandia became one of the great bases of the war. In the deep waters of Humboldt Bay a complete fleet could lie at anchor. Tremendous docks were constructed, and 135 miles of pipeline were led over the hills to feed gasoline to the airfields. Where once I had seen only a few native villages and an expanse of primeval forest, a city of 140,000 men took occupancy.24

On 10th April MacArthur had issued a warning order for the capture of the airfields on Wakde, a small island off the New Guinea coast about 120 miles west of Hollandia, and near Sarmi on the mainland to the west. The area was defended by the 36th Japanese Division, less one regiment which was on Biak Island, and a force of about two battalions advancing east against Hollandia.25 The American forces were again directed by General Krueger, who allotted the task to the 41st Division.

Wakde itself, an island only 3,000 yards by 1,200, was garrisoned by a reinforced company of infantry about 280 strong, 150 naval men and about 350 other troops. On 17th May, as a preliminary move, a regiment landed on the mainland with no opposition; and a force landed on a very small unoccupied island near Wakde whence mortars and machine-guns fired on Wakde itself. After an intense bombardment from land, sea and air, a battalion was landed and after three days of severe fighting in which 40 Americans and 759 Japanese were killed the island was handed over to the air force.

Krueger now set about clearing the Japanese from the Sarmi area. This led to a long and bitter struggle. In the second week of June the 6th American Division was brought in and by 25th June the Japanese force had been defeated and dispersed, having lost about 3,800 killed in the Wakde-Sarmi area; about 400 Americans were killed in the whole operation.

Biak, the next objective, 315 miles west of Hollandia, is a coral-fringed island consisting mainly of tangled, jungle-clad hills but possessing in the South-west a narrow coastal plain large enough to house several airstrips. Allied Intelligence estimated the garrison at some 2,000; actually there were about 11,000 Japanese on the island. Against this force was to be launched the 41st Division (less one regiment), which was to land on 27th May east of the airstrip area on a narrow coral shore dominated by a high cliff. The craft drifted westward and reached the shore, which was veiled by haze from the bombardment, 3,000 yards west of the intended places, but the landing was virtually unopposed and by nightfall the beach-head seemed secure. On the 28th and 29th, however, the Japanese attacked, and cut the road behind the 162nd Regiment which was advancing along the coastal shelf to the airstrips and hemmed it in. It was re-embarked and brought back to the beach-head. The third regiment of the division arrived on 31st May. The division advanced slowly westward and on the 7th June captured the easternmost airstrip, but it was still under fire from Japanese in the hills.

Progress was very slow and on 13th June a regiment of the 24th Division from Hollandia was ordered to Biak. It was a hard task to clear the Japanese from deep caves above the, airfields, a strongly-defended pocket to the east, and from the jungle-clad northern part of the island,

and it was 22nd July before it could be said that effective Japanese resistance had ceased. About 400 Americans and 6,000 Japanese were killed.

While the long struggle for Biak continued the next task on the time-table – the capture of Noemfoor Island, midway between Biak and Manokwari, headquarters of the II Army – was carried out. Noemfoor contained airfields from which fighters could patrol the Vogelkop Peninsula and also was a base from which Japanese barges might run to Biak. The island was believed to be garrisoned by about 3,000 troops, the main fighting unit being a battalion of the 35th Division; there were in fact fewer than 2,000 Japanese but about 1,000 Formosan and Javanese labourers.

Krueger allotted Noemfoor to the 158th Regimental Group, reinforced for this operation to a strength of 8,000. The landing on 2nd July was unopposed and, by the end of the first day there, had met no organised resistance. On the early morning of the 6th, however, the Japanese made a desperate counter-attack in which they lost 200 killed; mopping-up was virtually complete on 31st August. The Americans had lost 70 killed, the Japanese about 1,900.

The 6th American Division landed in the Sansapor area on the Vogelkop west of Manokwari on 30th July. There was no opposition. The II Japanese Army Headquarters had moved to the narrow neck of the Vogelkop and most of the 35th Division to Sorong.

Meanwhile, 730 miles to the rear, the isolated but resolute XVIII Japanese Army had made a determined counter-attack, just as the XVII Army had done on Bougainville. In May the 32nd American Division had been concentrated at Aitape where it formed a perimeter about 9 miles wide by two deep round the Tadji airfield. Patrols moved east as far as Babiang, 25 miles from Aitape, and in that area from 7th May onwards there were clashes with strong parties of Japanese. The divisional commander, Major-General Gill, decided to maintain a forward position on the Dandriwad River, but the Japanese pressed on and forced a withdrawal to the Driniumor, about 12 miles from the perimeter.26

Radio messages intercepted in June suggested that the XVIII Japanese Army would attack the Aitape perimeter in the first ten days of July using 20,000 men and with 11,000 in reserve. Thereupon the 112th Cavalry Regiment was sent to Aitape and XI American Corps headquarters (Major-General Charles P. Hall) took command. The 43rd Division and the 124th Regiment were also ordered to Aitape to help meet the coming attack.

Aitape–Babiang

By 10th July the Japanese had three regiments on the Driniumor and early next morning they attacked and broke through the American line. The defenders withdrew about four miles. Counter-attacks carried the Americans forward again to the Driniumor, and by 18th July they held the river line from Afua to the coast. By the end of July the Japanese pressure was easing. The enemy troops were ill-fed and many were sick. Nevertheless General Adachi decided to make one more attack. This was repulsed and almost simultaneously the Americans attacked and were soon thrusting the XVIII Army eastward to the Dandriwad where a Japanese rearguard halted them. The defenders had lost 450 killed and estimated that 8,800 Japanese had been killed from 22nd April to 25th August.27

In this period there had been little contact between the XVIII Army and the Australians to the east. In the early days of May the 5th Division carried out only local patrols from Madang and Alexishafen. All trails leading into the two towns were patrolled and a few Japanese were mopped up. When General Savige issued his first instruction as GOC New Guinea Force on 8th May he reiterated the tasks already given to General Ramsay, but there was a more positive call to action in one sentence which said, “Maintain pressure on the enemy northward of Alexishafen by patrol activity.” Savige suggested that an infantry company with a Papuan platoon should move to Mugil Harbour whence patrols could operate and where a base could perhaps be established for a battalion and a Papuan company which could be “used for patrols into the back country”. Any movement would, of course, be limited by the ability of the company of the Engineer Special Brigade to support it and that company also had to carry out maintenance of the Madang-Alexis-hafen area.

The 35th Battalion moved to Megiar Harbour on 10th May and gradually the patrols stretched out along the coast. Ahead of their advance HMAS Stawell bombarded Karkar and Manam Islands on 12th May, drawing light fire from Manam. Four days later an Australian frigate accompanied by two corvettes shelled Hansa Bay, Bogia and Uligan Harbour.

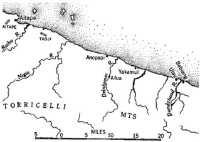

Madang–Wewak

At the beginning of June the 35th Battalion reached Kronprinz Harbour without opposition. Patrols reached Suara Bay five miles west from Dugumur Bay on 9th June. Here the 35th Battalion was relieved by the 4th, which resumed the advance towards Hansa Bay accompanied by the Papuan troops. Patrols reached Bogia on 13th June and were told by a solitary Chinese that the Japanese had departed before the end of April. By the 14th patrols passed through Potsdam, deserted except for about 90 emaciated Chinese, and during the next few days the 4th Battalion explored a deserted Hansa Bay, reaching the northern tip of the harbour on 17th June. The Australians learnt from the Chinese that there were no Japanese anywhere in the area and that the withdrawal of thousands of them had taken place by day and night weeks ago.

Meanwhile, on 19th May, an American fighter pilot, flying low over the area between the Sepik and Ramu Rivers searching for a pilot who had crashed, saw a party of dark-skinned troops in green who tried to attract his attention. On 1st June Lieutenant Barnes, an American pilot flying a Cub, flew low over a village west of the Ramu and saw three

soldiers about 4 miles North-east of the village. They had a ground signal displayed and a message suspended between two poles. The Cub picked up the message and from it Barnes learnt that the troops below were Sikhs of the Indian Army who had been captured at Singapore, and who had escaped on 6th May during the Japanese withdrawal from Hansa Bay to Wewak. A subadar-major of the 1/14th Punjab Regiment was in charge. His message gave a detailed map and full report of the Japanese evacuation routes. After reading the message Barnes dropped instructions to guide the Indians to the emergency strip he had used to rescue the American pilot mentioned above. In the afternoon he returned from Saidor and dropped rations and medical stores to the Indians.

The Indians were apparently in very poor health, and a medical sergeant, Gregory28 of the 24th Battalion, volunteered to land at Sanai by parachute so that he could attend to the Indians until arrangements could be made for their rescue. He left Saidor on 4th June and was landed by Staff-Sergeant J. L. Henkle on the emergency strip. Gregory found the Indians – now 29 in number – after two days’ searching and led them back to the strip where a Flying Fortress from Nadzab guided by Barnes had dropped three tons of rations, clothing, equipment, arms, ammunition and medical stores. The Indians were in a pitiable condition, suffering from malaria, dysentery and starvation, and Gregory, assisted by Henkle, did his best to nurse them back to health. By 17th June all had been evacuated to Dugumur Bay whence some were flown to Saidor and some sent by barge to Madang.

The Indians brought with them first-hand knowledge of the plight and intentions of the XVIII Army. They themselves had escaped from a party of 547 Indian prisoners who left Hansa Bay for Wewak on 21st April as part of the general retreat. The Japanese had begun to evacuate Hansa Bay in March and had finished in May. The evacuation was at the rate of about 1,000 a day. Only one in ten was armed and the remainder carried packs and rice only. Hundreds were said to have died between Hansa Bay and the Sepik. The Japanese went by foot to the mouth of the Ramu which was crossed at night in boats, by foot to Wangan, by barge up the Sepik to Marienberg, and finally by foot to Wewak. Craft used were three big barges each carrying 70 men, three or four small launches, holding 20 to 30 each, and native craft.

There was no material change in troop dispositions late in June and early in July. The 4th Battalion continued to patrol the Hansa Bay-Bogia area while the Papuans went farther afield and probed the area between the mouths of the Ramu and the Sepik. The Papuans found the Sepik natives seemingly friendly but unable to understand the bombing and strafing of their villages long after the departure of the enemy. Another Papuan patrol down Watam Lagoon to Wangan on 6th July found that the Japanese had excavated a passage linking the lagoon with the Sepik, thus enabling launches to negotiate the passage through to Singarin. The

natives showed that they were on the Japanese side. When a Papuan patrol reached Wangan on 4th July natives told them that there were about 100 Japanese at Singarin. The patrol cut across the swamp country and three days later reached Old Bien on the Sepik. Here they waited while local natives went to bring canoes. The natives fetched the Japanese instead, and before dawn on the 9th the patrol was attacked by a mixed band of about 50 Japanese and natives and was forced to disperse, losing much equipment and many weapons. The patrol arrived back at Wangan on the 11th, footsore after clambering through the sac sac swamp. The Japanese apparently had forces at Singarin, New Bien and Marienberg, and the Sepik was probably an outpost defence line.

There were few other developments before the story of the great New Guinea offensive dwindled to a close. The only fighting unit left in the Ramu Valley was Captain Chalk’s company of the Papuan Battalion, which returned there in June from Port Moresby and was based at Dumpu and Faita with an air-sea rescue party far down the river at Annanberg which the Japanese had left two months earlier. On 13th July the 30th Battalion relieved the 4th Battalion at Hansa Bay and continued patrolling towards the Ramu while the Papuans set up bases at Watam and Wangan and patrolled to the Sepik. August opened with a Papuan patrol near the mouth of the Sepik watching the Japanese on the other side through field glasses.

Throughout 1943 and 1944, while large-scale fighting was taking place along the northern littoral of New Guinea, only a few skirmishes and some desultory air action occurred along the south coast. The Japanese evidently decided in 1942 that an advance along the south coast of Dutch New Guinea offered few prospects of paying military dividends. The country was inhospitable, with vast areas of swamp, and the island-studded Tones Strait presented an awkward barrier between the Arafura and the Coral Seas. At the beginning of 1943 the foremost Japanese post of any size was at Kokenau, on the coast 325 miles North-west of Merauke. A sprinkling of Dutch and Indonesian officials and missionaries remained in the area east of Kokenau. Merauke had been bombed by the Japanese and the population had dispersed. At Tanahmerah, a penal settlement on the Digoel River, were some hundreds of political exiles from Java – a possible embarrassment if military operations began in the area – and they were soon removed to Australia. At the Wissel Lakes, in the mountains north of Kokenau, was a Dutch outpost with a radio set. It seemed likely that, if the Japanese advanced in southern Dutch New Guinea, Wissel Lakes, on which flying-boats could alight, Tanahmerah, where an airfield could be built, and finally Merauke would be among their main objectives. At intervals during 1943 there were fears – unfounded, it transpired – that such an advance might be undertaken.

After the reinforcement of Merauke from December 1942 to February 1943, mentioned earlier, “Merauke Force” included an American antiaircraft battery and port detachment, the 62nd Australian Battalion, and

Area of Merauke Force operations

a company of NEI troops. An air force radio station had been at Merauke since 1942. The tasks of the force were to deny the Merauke airstrip and docks to the enemy. This little force, situated more than 200 miles from Thursday Island, and on the edge of a sea in which Japanese naval control was unlikely to be seriously disputed, would not have been able to hold Merauke against a strong attack by the Japanese, who then had two divisions – the 5th and 48th – in the Timor-Ambon-Aru Islands area.

In mid-March 1943 Intelligence concerning a possible Japanese offensive against northern Australia reached GHQ and MacArthur, in April, ordered a general strengthening of the Torres Strait area. As a result the headquarters of the 11th Brigade and one more infantry battalion – the 31st/51st – were ordered to Merauke, with a strong force of engineers. In May a company of the 26th Battalion arrived. Brigadier J. R.

Stevenson of the 11th Brigade became commander of the force, whose tasks now included construction of airfields, roads, wharves and other requirements of a substantial base. The air base, when completed, was to be occupied by No. 72 Wing, with one fighter and one dive bomber squadron. The first aircraft landed on the airfield on 30th June, and by 3rd July No. 86 (Kittyhawk) Squadron was complete at Merauke. No. 12 Squadron, with dive bombers, came later. Merauke was under intermittent air attack during 1943. On 9th September, for example, it received its twenty-second raid – by 16 bombers and 12 fighters.

Patrols from Merauke Force probed deeply northward and westward, often making all or parts of their journeys in the network of rivers in small craft. At the same time small outposts were thrust farther and farther westward. Thus, by August, there were outposts with RAAF radar stations at Cape Kombies and Tanahmerah, the latter being now protected by a whole company of the 26th Battalion, and small outposts, each under an infantry sergeant, at Mappi and Okaba.

It was not until December 1943 that the first clash with a Japanese patrol occurred. Wing Commander D. F. Thomson, an anthropologist, set out with a small party to find a suitable position for an outpost in the Eilanden River area. On 24th November he and two of his men were wounded by natives with stone axes. They were taken out by a flying-boat and Captain Wolfe,29 an engineer who had already made some very long patrols, took over, and continued probing westward along the channels in the vast swamp area, moving in the launch Rosemary and a 20-foot tow-boat. On 22nd December near Japero the patrol suddenly encountered two Japanese barges, each about 40 feet long and carrying 10 Japanese. A sharp engagement followed, the Japanese firing machine-guns and mortars and the Australians firing Brens and rifles and – as the craft closed one another – throwing grenades. After two minutes the Japanese made off. One Australian was killed – Corporal Barbouttis30 who played the leading part in the exchange of fire – and 6 wounded.

As an outcome of this patrol “Post 6” was established near the mouth of the Eilanden River, and here a second clash soon occurred. In the evening of 30th January a flotilla of three 30-foot barges and five 15-foot launches manned by Japanese appeared upstream from Post 6, having evidently entered the Eilanden along a channel leading into it from the west in search of the Australian post. The Australians under Lieutenant Roodakoff31 held their fire until the three leading craft were only 150 yards away, poured fire into them for a few minutes, killing about 60 (they estimated) and then pulled back from the river bank. The Japanese fired towards both banks of the river for 20 minutes, without effect, and, after dark, sailed downstream and out to sea. Next day aircraft from

Merauke strafed four barges in the vicinity. After this Post 6 was reinforced, and eventually a company was stationed there.

The 62nd Battalion was replaced by the 20th Motor Regiment in February 1944. In August the 11th Brigade was withdrawn to prepare for other more active tasks, leaving the 20th Motor Regiment as the main infantry component of the garrison. Merauke Force succeeded in establishing a well-developed base, patrolling a very large area of difficult country and advancing fairly strong outposts more than 200 miles north and North-west, eventually extending its military control to most of that part of Dutch New Guinea that lies south of the central range.

During the advance along the coasts of Dutch New Guinea General MacArthur’s staff had been considering the need for air bases in the islands between the Vogelkop and Mindanao. At length on 15th June 1944 a revised plan (RENO V) was completed which provided for an advance into the Halmaheras area on 15th September – the date tentatively fixed for Admiral Nimitz’s invasion of the Palaus. It will be recalled that MacArthur’s staff still considered that it would be necessary to seize islands in the Arafura Sea from which to give land-based air cover to the operations farther north. It was now decided that these islands would be occupied only if land-based aircraft from Darwin and the New Guinea bases could not secure the left flank from attack by Japanese aircraft based on Ambon, Ceram and Celebes. The landing on Mindanao was scheduled for 25th October. It was believed that the Japanese had some 30,000 troops in the main islands of the Halmaheras whereas Morotai, some 50 miles to the north, was lightly defended. Consequently on 19th July an outline plan for the occupation of Morotai was completed.

Meanwhile, in June, the offensive against the Marianas Islands had been mounted by Admiral Nimitz’s forces. In some respects this expedition was on an unprecedented scale. Over the last 1,000 miles a fleet of 535 fighting ships and transports would carry 127,000 troops. They included the V Marine Corps (2nd and 4th Marine Divisions) aimed at Saipan and Tinian, the III Marine Corps (3rd Marine Division and 1st Marine Brigade) aimed at Guam, and as a floating reserve the 27th Division; the 77th Division was in general reserve. D-day for Saipan was 15th June, but the dates of Guam and Tinian were not to be decided until the outcome at Saipan was known. It was impressive evidence of the immense volume of shipping now available to the Allies that, while this seaborne Pacific operation was making ready, the invasion of Europe began.

There were some 32,000 Japanese on Saipan including the 43rd Division and 47th Independent Mixed Brigade and 6,700 naval men; there were 71,000 Americans in the V Corps. From 11th to 13th June the aircraft of fifteen carriers struck at the objectives, and on the 13th, 14th and 15th June battleships and smaller vessels bombarded them. At 7 a.m. on the 15th the landing craft carrying the V Corps set off from a line 4,000 yards from the shore and on a front of almost four miles. The

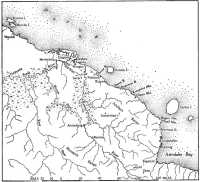

The Allied offensive in the Pacific, April 1943 to September 1944

troops were met by intense fire and at the end of the first day were far short of the objective and clinging to narrow beach-heads. They broke up Japanese counter-attacks, however, but the position seemed perilous on the 16th. It was decided to send the 27th Division ashore and it began landing at dusk. By the 17th the beach-head seemed secure but a long battle lay ahead. By 21st June the Americans had secured the southern one-third of the island, by the 27th the southern half, and by 6th July had confined the defenders into a pocket about four miles long. The last resistance ended on the 9th.

There were perhaps 20,000 Japanese civilians on Saipan. Hundreds of these fled to the northern end of the island, where they refused to surrender and, eventually, on 11th and 12th July

believing that the end had come, embarked on a ghastly exhibition of self-destruction. Casting their children ahead of them, or embracing them in death, parents flung themselves from the cliffs onto the jagged rocks below. Some waded into the surf to drown or employed other gruesome means of destroying themselves. How many civilians died in this orgy of mass hysteria is not known.32

The Americans lost 3,426 killed. Only 971 Japanese troops were taken prisoner.

While the fight for Saipan was in progress the Japanese sought to carry out their intention to engage in a decisive naval battle. On 15th June the Japanese “Mobile Fleet”, including 9 carriers and 5 battleships, sallied out into the Philippine Sea against the American Fifth Fleet, which had 15 carriers and 7 battleships. In the ensuing clashes on the 19th and 20th the Japanese lost 3 carriers, two sunk by submarines, the Americans none, although a number of their ships were damaged.

Lessons learnt at Saipan were applied at Tinian which was taken by the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions. The landing took place on 24th July and the whole island was in American hands by 1st August, with a loss of 389 killed; more than 5,000 Japanese were buried.

On Guam (the first American territory to be regained) were 19,000 Japanese including the 29th Division. The attacking force was the III Marine Corps including the 3rd Marine Division, 1st Brigade and 77th Division, an army formation not previously in action. The two marine formations landed at separate beaches each side of the harbour on 21st July, threw back the counter-attacks and, with the 77th, gained control of the island by 10th August, although thousands of Japanese were then still at large in the jungle. The Americans lost 1,435 killed, all but 213 being marines. Japanese casualties included about 10,600 killed and 1,250 taken prisoner.

MacArthur gave the task of taking Morotai to General Hall’s XI Corps, with the 31st Division and a regiment of the ubiquitous 32nd under command. Two of the attacking regiments were embarked at Aitape, 920 miles from the objective. There was no opposition on the beaches, which was fortunate since coral boulders and mud made landing extremely

difficult and there was some confusion. The objective – an area 7,000 yards by 5,000 round the airfield – was reached on the second day (16th September) and thereafter there were only patrol actions against Japanese groups at large in the bush to the north. The perimeter was later extended.

The Palaus operation was a far larger affair, carried out by the III Marine Corps which included the veteran 1st Marine Division and the 81st Division, an unblooded army formation, the first to take Peleliu and the second Angaur. The 77th Division and the 5th Marine Division were in reserve.

There was little opposition as the troops came ashore at Peleliu on 15th September, but resistance increased as they pressed inland, and by nightfall the perimeter was only 400 to 700 yards deep except at one point where the marines had pushed across the narrow atoll. In the next six days the marines pressed on but had 4,000 casualties. A regiment of the 81st Division was landed, but it was not until 30th September that only mopping-up of resolute parties remained. The Japanese dead were estimated at 11,000; and pockets of Japanese still remained which were not defeated until 27th November. It had been a costly operation, the 1st Marine Division losing about 1,250 killed and the 81st Division 278.

The 81st Division was landed on Angaur on 17th September and by the morning of the 20th it had killed 850 Japanese and reported that the island was secure. It was 21st October, however, before the last pockets of Japanese resistance had been cleared. By that time 1,300 Japanese had been killed and 45 captured. The Americans lost 264 men killed and their total casualties, including 244 cases of “battle fatigue”, were 2,559 (nearly twice the strength of the enemy garrison).

Between January and September 1944 the American amphibious forces had advanced from a line through the Huon Peninsula, Torokina and the Gilbert Islands to one through Morotai, the Palaus and Saipan. They were half way to Tokyo. Thirteen Japanese divisions, apart from smaller formations, had been destroyed or isolated. In the process the American forces had gained greatly in experience and skill. Although the Pacific war was two years old when this drive began, the only divisions of the American Army that had fought against the Japanese were four (the Americal, 25th, 37th and 43rd) in the Solomons, two (the 32nd and 41st) under MacArthur, and two (the 7th and 27th) in the Central and North Pacific; three marine divisions had been in action. Now 16 army divisions and four divisions of marines had been in action, some of them several times.33

In the third quarter of 1944 fewer Australian troops were in contact with the enemy than at any time since the few weeks that elapsed between the relief of the siege of Tobruk and the opening of the war against Japan. Most of the divisions of the Australian Army were re-training for

the final effort in 1945 in which every division would be involved. They needed rest, and some reorganisation, for the offensive of 1943-1944 had brought the nation near the limit of its resources. At the end of July 1944, 697,000 men and women – nearly one in ten of the Australian population – were still serving in the armed Services.34 In their long, hard fight in 1943 and 1944 the Australians had defeated a brave and tenacious foe. Old traditions had been worthily upheld. Courage, determination, self-sacrifice, team work, initiative, endurance – and humour – had enabled them to triumph over a fanatical enemy, and over the rugged and pitiless terrain and the rigours of a tropical climate. Throughout this period they had been uplifted by the knowledge that they were the spearhead in the land battle against the Japanese, and they had developed a confident and masterful efficiency in jungle warfare. Australian Army battle casualties to 26th August 1944 totalled 57,046, including 12,161 deaths, 15,726 wounded, 3,548 missing and 25,611 prisoners. In the operations described in this volume 1,231 Australian soldiers were killed and 2,867 wounded.

After the war General Kane Yoshiwara, of General Adachi’s staff, gave the maximum strength of the XVIII Japanese Army as 105,000, including those lost at sea – about 3,500.35 By March 1944 its strength, he writes, was 54,000. About 13,000 Japanese had died in Papua by January 1943. Therefore about 35,000 must have died during the fighting and the retreat described in this volume.

In April 1943 Australia, according to her Prime Minister, had still been under the shadow of Japanese invasion. One seasoned brigade of Australian troops and two Independent Companies were holding the Japanese in the forbidding ranges between Wau and Salamaua – the only place in the Pacific theatre where there was then any fighting. The onrush of the Japanese invaders through New Guinea had already been stopped in the fierce Papuan campaigns, and in the South Pacific the Americans had held Guadalcanal. Months of fighting, patrolling and planning were followed by the triumphant Australian offensive which shattered the XVIII Japanese Army, drove it back beyond the Sepik, and paved the way for the spectacular American advance towards the Philippines. In 16 months of war the Japanese had passed from the exhilarating heights of victory to the grim verge of defeat.