Chapter 6: Final Stages of the Sicilian Campaign

31 July–17 August 1943

The Capture of Regalbuto, 31 July–2 August

The Hermann Göring Division’s operation order of 27 July, already cited (above, p. 131), contained explicit instructions for holding Regalbuto, which with Centuripe formed the main outposts of defence in front of Adrano, key position in the Etna line. Regalbuto marked the western extremity of the Division’s responsibilities (which extended inland from the coast near Acireale); and the GOC, Maj-Gen. Paul Conrath, regarded this right flank as the critical point of his whole line. This he might well do, for Maj-Gen. Simonds’ eastward thrust made Regalbuto an obvious Canadian objective; while the junction with the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division’s left wing was by no means firm, both formations lacking the necessary troops to secure it.

To strengthen his flank Conrath ordered the Hermann Göring Armoured Engineer Battalion to take over the defence of Regalbuto and to retain or take under command a squadron of tanks and certain sub-units of artillery. The Engineer Battalion, which had previously formed part of one of the Division’s battle groups,*

* Battle Group von Carnap, which had been holding the Regalbuto area.1

now came directly under Conrath’s command. For the first time since their encounter at Grammichele the Canadians were to meet the Hermann Görings again.

An order issued by the Engineer Battalion on 27 July urged the necessity of retaining the Regalbuto position.2 Proudly the author of the document reminded the battalion that enemy action had “hitherto not forced a withdrawal to a new line”. Although preparations had been made for the Hermann Göring Division in due time to fall back to the “bridgehead position (previously the Etna position)”, the only circumstances which could force such a withdrawal would be “the movement of 15 Pz Gren Div”!

Having given instructions for the removal of transport to the rear areas, the order concluded emphatically:–

In all orders concerning the bridgehead position it must be made absolutely clear that the present position must be held at all costs. Any instructions for withdrawal are preparatory. There must be no doubt about this point. The abandonment of the present position and a fighting withdrawal to the bridgehead position will only be carried out on express orders from division.3

Hitler himself could not have been more definite.

It will be recalled that in his order for the capture of Agira General Simonds had assigned the 231st Brigade the task of leading the subsequent advance eastward through Regalbuto and seizing the bridge by which Highway No. 121 crossed the River Salso west of Adrano.4 Early on the 29th the brigade moved two battalions forward from their positions immediately east and south of Agira. Like the Canadians the troops of the Malta Brigade found that the country traversed by Highway No. 121 offered every advantage to the defender. There was the same succession of rocky ridges crossing the road at right angles, each one a potential site for a strong German rearguard action. In this broken and mountainous terrain, much of it covered by thick olive and almond groves, it was practically impossible for reconnaissance to detect the enemy’s whereabouts, and frequently an advancing body of company strength or less might suddenly find itself committed against a defensive force too firmly entrenched to be successfully engaged by anything less than a battalion with supporting arms.

Such a situation the Hampshires encountered on the night of 29 July. With the Dorsets they had led the brigade’s eastward advance for about six miles, cautiously probing every suspicious rise in the ground, without meeting serious opposition. As night fell they received orders to launch an attack against a long ridge which stretched south of the highway within a mile of Regalbuto (see Sketch 2). Unlike most of the other ridges in the area, this one ran parallel to the road, which it commanded along its entire length. On this rocky rise the Hermann Göring Engineers had decided to make their stand to prevent or delay the capture of Regalbuto, a fact of which the Hampshires became unpleasantly aware when a wicked burst of nebelwerfer fire met them as they formed up on their start line. One platoon was practically wiped out. In spite of this inauspicious beginning the battalion pressed on bravely, only to be caught in the deadly cross-fire of machine-guns. In the face of rapidly mounting casualties and a realization of the enemy’s numbers, the attack was called off.5

Daylight revealed the natural strength of the defence position. From the 2000-foot peak of Mount Santa Lucia, which marked the summit of Regalbuto Ridge, the Germans could completely dominate the eastern and southern approaches to the town. Regalbuto, built 1600 feet above sea level, lay at the convergence of three prominent hill features. South-west ran the

mile-long Regalbuto Ridge; to the north-west a somewhat lower spur bearing the name Mount Serione projected about the same distance into the Salso valley; and to the east, separated from Santa Lucia by a deep ravine which admitted the road from Catenanuova, rose almost precipitously “Tower Hill”, the western extremity of the great barrier of heights reaching over to Centuripe.

Entry into Regalbuto by Highway No. 121 was impossible as long as the enemy held the Santa Lucia and Serione heights, and on 30 July Brigadier Urquhart ordered the 2nd Battalion, The Devonshire Regiment, to take the ridge to the south. That night, in a well-planned flanking attack carried out with great courage and skill, the British battalion stormed and seized Regalbuto Ridge. During their attack the Devons had the support of an artillery barrage fired by 144 guns from four field and three medium regiments.*

* The 1st. Field Regiment RCHA, the 2nd and 3rd Field Regiments RCA, the 165th Field Regiment RA, and the 7th, 64th and 70th Medium Regiments RA.6

But with daylight they were exposed to a desperate counterattack launched by the Hermann Görings, who were strengthened by troops of the 3rd Parachute Regiment. The Devons doggedly held their ground and drove off the enemy, though suffering casualties of eight officers and 101 other ranks.7

The action earned the praise of The Red Patch, a daily news-sheet which the Canadian Divisional Headquarters had just begun to publish. It acclaimed

the 231st Brigade’s fight for Regalbuto Ridge and the achievement of the Devons in repelling the German paratroopers and the Hermann Görings, and concluded:–

In Tunisia forty engineers of the Hermann Göring Division alone once counter-attacked a battalion position with such good effect that the battalion was routed. It is greatly to the credit of the Devons that they successfully beat off such a strong attack.

Well done the Devons.8

The Malta Brigade’s possession of Regalbuto Ridge made an assault on the parallel height north of the highway the next logical step, and in the late forenoon of the 31st the Dorsets attacked the long spur of Mount Serione. One company captured the uncompleted railway station, terminus of a line winding up from the Salso valley, construction on which had been halted in 1940. On the high ground above the station another company fought and won a bloody engagement with a group of Germans who were defending a walled cemetery. By mid-afternoon the Dorsets held the length of the Serione ridge as far as the outskirts of Regalbuto, and thus dominated the two roads leading north-west and north from the town. Before dusk they were relieved by the 48th Highlanders of Canada, who were temporarily placed under command of the Malta Brigade.9

The stage was thus set for a direct attack upon Regalbuto itself, and at 4:30 in the afternoon General Simonds outlined to his brigade commanders the form that the operation should take. He explained that two of the three main heights which dominated the town were now in our hands, but that an attempt by the Devons to occupy Tower Hill – so named from an old stone look-out on its summit – had been stopped by the cross-fire of tanks sited in the valley to the south. The 231st Brigade was endeavouring to bring up anti-tank guns to deal with this armour, and would make what would amount to a “reconnaissance in force” against the vital position that night. The RCR (of the 1st Brigade) was to be in readiness to exploit success or, if necessary, to launch an assault supported by the divisional artillery. In anticipation of the fall of the town the 2nd Brigade was directed to send patrols about five miles to the north-east, to explore the mountainous country between the Salso and its tributary, the Troina.10

From their concentration area among the hills east of Agira the RCR made an approach march of half a dozen miles on the evening of the 31st. Leaving the highway they followed a rough track which took them around the southern side of Regalbuto Ridge right into the outlying fringe of houses that formed a horseshoe around the deep gorge below the town. Across the gully from them rose the almost vertical slopes of the Tower Hill objective, with the road from Catenanuova encircling its base. Lt-Col. Powers (promoted from Major on 30 July) now learned that the Malta

Brigade’s reconnaissance, carried out by a company of the Dorsets, had not succeeded in making contact with the enemy and drawing his fire to cause him to reveal his positions. There being no specific targets to engage, artillery support was cancelled, and at 2:00 a.m. the RCR put in their attack. Leaving one company to cover their advance the other three began the difficult descent down the crumbling shale of the west side of the ravine. The obstacle proved unexpectedly deep. Only the centre company managed to climb part of the way up the eastern slope before the approach of daylight brought fire from enemy machine-guns and tanks hidden among the buildings in the town’s southern and south-western outskirts. The battalion’s anti-tank guns had not yet come forward, and tank-hunting patrols sent out with PIATs to either flank met with little success. One such platoon having penetrated into Regalbuto in an attempt to surprise the German positions from the left became cut off from its company by enemy fire. It spent the day working its way through the western part of the town and eventually reached the 48th Highlanders on Mount Serione.11

In the early light of 1 August the three RCR companies found what cover they could on the eroded western slope of the ravine. There they spent a most disagreeable day subjected continuously to enemy sniping, shelling and mortaring, and suffering from hunger and thirst aggravated by the burning heat of the sun and the stench that came from the town and from the unburied bodies around them. Once during the afternoon the anti-tank platoon dragged one of its six-pounders into place in the south-western outskirts of the town to bear upon the German positions across the gully. But the enemy was very much on the alert. As the gun was about to fire one of his tanks darted from behind a building and got away three quick rounds. One of these scored a direct hit, knocking out the six-pounder and killing one of the crew and wounding the remainder. As night fell orders came from Brigade Headquarters for the battalion to withdraw under cover of darkness.12

Meanwhile the 48th Highlanders had remained in close contact with the defenders of the north-western corner of Regalbuto. Action on both sides was confined to sniping and the exchange of light machine-gun fire, although the Highlanders suffered some casualties from enemy shelling. The rifle companies, like those of The Royal Canadian Regiment, were without their supporting arms, for as yet there was no way of bringing these across the two miles or more of broken country from Highway No. 121. It was not until early on 2 August, after sappers of the 1st Field Company RCE had worked under shellfire all the. previous day developing an emergency track from the main road to Mount Serione, that supporting weapons, together with much-needed rations, reached the Highlanders.13

As a result of the stalemate which had met the 1st Brigade’s efforts, the divisional commander issued fresh orders during the afternoon of 1

August. It was his appreciation that the enemy on the heights east of Regalbuto would not withdraw “unless ordered to do so by his’ own higher command. He is well sited and possesses about eight tanks. It is probable that he will fight hard to hold his present position.14 But what a frontal attack could not accomplish, a pincers movement might well achieve. Simonds proposed to employ the 1st Brigade in a right flanking movement designed to take the troublesome Tower Hill from the rear, i.e., from the east. On the left the 2nd Brigade was to follow up the work of its patrols by occupying the high ground between the Salso and the Troina. The Malta Brigade’s task was to provide a firm base for these operations and eventually to secure Regalbuto itself, assisted by the 48th Highlanders, who were still under Brigadier Urquhart’s command.15

It fell to the Hastings and Prince Edwards to carry out the 1st Brigade’s part of the plan. About a mile south-east of Regalbuto the road to Catenanuova climbed over a saddle between two hills – conical Mount Tiglio to the west and the more massive Mount San Giorgio to the east. The Tiglio feature became the initial. Canadian objective, and the stretch of road between the, two heights was designated the start line for the subsequent thrust northward against the main ridge east of, Tower Hill. The Hastings set off about 10:00 p.m. on 1 August, and by dawn next morning had scaled and occupied Mount Tiglio, finding it abandoned by the enemy. Several hours were to elapse before preparations for the final assault were completed. The men were glad of the rest, for as so frequently happened in Sicily their route had been across country over which no vehicles could follow, and all food, water, ammunition, wireless sets, mortars and other necessary equipment had to be man-packed over a mule track which the Brigade Major later reported as going “twice as far up and down as it went along.”16

But as the infantry waited, their supporting arms were not idle. While it was still dark, guns of the 7th Medium Regiment were pounding the highway east of Regalbuto, and when daylight came the 1st Canadian Field Regiment laid down a smoke line in the same area as a target for 25 Kittyhawks to bomb and strafe. A divisional task table was prepared for an artillery barrage to be fired ahead of the 1st Brigade’s attack by the three Canadian field regiments.17 All available air support was directed against the east-bound traffic which was expected to fill the road between Regalbuto and Adrano when the infantry assault developed.

Trouble with wireless sets and the difficulty of maintaining other means of communication over such extremely rugged ground delayed the preparations for the final attack. But before zero hour, which had been postponed to 4:00 p.m. on 2 August, word came that a patrol of the 48th Highlanders had entered Regalbuto that morning and found it empty. Accordingly the barrage was cancelled at the last minute, and Major

Kennedy was ordered to take the Hastings and Prince Edwards forward to the final objective.18

The Hastings crossed the Catenanuova road, finding square Mount San Giorgio free of the enemy, and then swung northward across the valley which separated them from the great escarpment towering 2500 feet into the sky. But although the Germans had evacuated the town, they would not relinquish their hold on the Regalbuto area without one final’ effort. A rearguard of paratroopers, estimated at two companies, still held the important ridge, and these met the advance of the Hastings and Prince Edwards with savage bursts of machine-gun and mortar fire. The heavy 3-inch mortars which the Canadians had manhandled across the difficult country now went quickly and effectively to work. One company climbed Mount San Giorgio, and under cover of its small-arms fire the remaining three pressed on the assault. Wireless communications redeemed themselves, and the 2nd Field Regiment’s FOO was able to call down very accurate concentrations on the enemy positions. Thus aided, the infantry stormed the ridge and put the German paratroopers to flight. By eight o’clock in the evening the battalion was in firm possession of the ridge. The last enemy stronghold on the road to Adrano had fallen.19

The enemy’s enforced withdrawal from Regalbuto had given Allied aircraft the opportunity foreseen by General Simonds. During 2 August the air forces reported hitting forty motor vehicles caught on the open road between Regalbuto and Adrano, while eight light bomber attacks on Adrano itself started a large fire in the town. To the north the parallel Highway No. 120 offered equally good targets, for Troina was now under attack from the 1st United States Division, and in the stream of German traffic seeking, escape eastward, fifty vehicles were claimed destroyed at Cesaro.20

When the Canadians entered Regalbuto on the heels of the occupying troops of the Malta Brigade, they came upon a scene of destruction far more extensive than any they had previously encountered in Sicily. The town had received a full share of shelling and aerial bombardment, and hardly a building remained intact. Rubble completely blocked the main thoroughfare, and a route was only opened when engineers with bulldozers forced a one-way passage along a narrow side-street. For once there was no welcome by cheering crowds, with the usual shouted_ requests for cigarettes, chocolate or biscuits. The place was all but deserted; most of the inhabitants had fled to the surrounding hills or the railway tunnels. They were only now beginning to straggle back, dirty, ragged and apparently half-fed, to search pitifully for miserable gleanings among the debris of their shattered homes.21

The Fighting North of the Salso – Hill 736, 2–5 August

The axis of the Canadian advance now swung north of Highway No. 121, as the Division entered upon the last phase of its role in Operation “Hardgate”. This, it will be recalled, was to be a drive for Adrano on the 30th Corps’ left flank, to parallel the 78th Division’s assault from Centuripe along the axis of Highway No. 121. As we have seen, during their advance from the Pachino beaches the Canadians had from time to time fought their way across territory so rugged that the passage of a body of troops seemed a virtual impossibility; the terrain over which the 2nd Brigade was now to operate was unsurpassed in difficulty by any that had gone before.

A mile or so east of Regalbuto the River Salso, which thus far in its descent from the heights about Nicosia has cut for itself a deep, narrow gorge, flows into a more open, flat valley. This widens below the entry of the tributary Troina, so that by the time it reaches the junction with the Simeto it has become a fertile plain two miles across. From the north side of the valley the land rises steadily towards the great mountain barrier which forms the backbone of the whole island. Highway No. 120 (from Nicosia to Randazzo) clung surprisingly to the southern shoulder of the height of land; but between this and the Salso the tangle of peaks and ridges extending eastward to the base of Etna was virtually trackless. In all this wild terrain the only route passable to vehicles was one narrow dirt road, connecting the mountain town of Troina with Adrano, which hugged the left bank of the Troina River until it reached the Salso valley, thence turning eastward into Highway No. 121. But the course of this rough track was almost at right angles to the direction that the Canadian advance must take; there were no east and west communications across the rocky spurs which reach down to the Salso on either side of its tributary from the north.

Three heights were to play an important part in the forthcoming operations. Five miles north-east of Regalbuto was a prominent feature, the most easterly of the mountain peaks in the angle formed by the Salso and the west bank of the Troina. It bore no name other than that given by its height in metres – Hill 736. On the other side of the road from Troina, respectively two and a half and five miles directly east of Hill 736, two more peaks of only slightly less altitude – Mount Revisotto, rising from the east bank of the Troina River, and Mount Seggio on the west bank of the Simeto – towered more than a thousand feet above the level of the Salso valley. These three hills dominated the entire valley eastward from Regalbuto, and there could be no assurance of safe passage for Allied troops along the river flats until they were denied to the enemy.

The defence of the sector north of Highway No. 121 was, as we have seen, the responsibility of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. At the time of the fall of Regalbuto and Centuripe the main part of this formation’s fighting strength was committed against the 2nd US Corps in the desperate battle for Troina. Subsequent identifications revealed that the role of guarding the Division’s left flank – between Highway No. 120 and the River Salso – had been given to the 382nd Panzer Grenadier Regiment, an independent formation whose two battalions had been raised*

* The original 382nd Panzer Grenadier Regiment, part of the 164th Light Africa Division, had been virtually destroyed in Tunisia. The new formation had been organized in Sicily prior to the Allied landings.22 (Prisoners from the regiment who told interrogators that they had been flown in from the Rome area on 15 July were presumably part of a late draft reaching Sicily.) At the end of August the regiment was dissolved and its personnel used to bolster various units of the 14th Panzer Corps.23

from troops that had served on the Russian front and from veterans of the 164th Light Africa Division.24 Behind them were the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 3rd Parachute Regiment, which had fallen back from its Regalbuto position to defend the Simeto River and the approach to Adrano. This formation had strengthened its depleted ranks by absorbing officers and men of the disgraced 923rd Fortress Battalion.25

It will be recalled that on 31 July, while operations against Regalbuto were still proceeding, General Simonds had directed the 2nd Canadian Brigade to send exploratory patrols north of the Salso, and that on the following day he had ordered occupation of the high ground west of the Troina River, that is, Hill 736 and its outlying spurs. Brigadier Vokes gave the job to The Edmonton Regiment. One of its patrols reached the foot of Hill 736 during the night of 31 July without meeting any enemy, fired several bursts from a Bren gun towards the summit without arousing any reply, and returned on the following morning with a tale of laborious progress over rugged terrain where “the trails were dried-up stream beds filled with rocks, and going would be difficult even for personnel on mules”.26

On the afternoon of 1 August the Edmonton rifle companies assembled at the point midway between Agira and Regalbuto where the River Salso came closest to the highway. There they awaited the arrival of a mule train which was to bring forward rations and ammunition, the battalion’s 3-inch mortars, and the medium machine-guns of a platoon of the Brigade Support Group. The use of mules wrote a new page in the history of the Saskatoon Light Infantry, whose diarist recorded that “Brigade was busy all day getting a supply in for this operation”. These improvisations caused a delay in departure (a message from the brigade to Divisional Headquarters reported that harness fitting was slow work).27 and at midnight the supply convoy had not yet arrived at the rendezvous. Lt-Col. Jefferson therefore decided to take his rifle companies forward alone.

The Edmontons followed the winding course of the Salso for nearly four miles, and then struck north-eastward into the hills. The rocky ground slowed their progress to one mile an hour, and they were further delayed when enemy aircraft dropped flares which forced them to deploy in order to avoid observation. Daylight found the forward companies still more than a mile west of their objective, and brought upon them fire from enemy self-propelled artillery on the Regalbuto side of the Salso. It quickly became apparent that the Germans had reoccupied Hill 736 and its approaches in considerable force, for their medium machine-guns and mortars opened up from the Canadian front and left, and the leading troops, unable to advance or to consolidate under the heavy fire, were forced to seek what shelter they might behind rocks and under the lee of overhanging cliffs. Prevented by the rocky nature of the ground from digging slit-trenches, the forward Edmontons held their precarious positions under fire all day. In the late afternoon they withdrew to the south and reorganized on the low ground at the river’s edge.28

Disappointing though this unsuccessful attempt to gain Hill 736 was, it was illumined by the great bravery displayed by a member of one of the Edmontons’ reserve companies. When “B” Company, leading the attack, suffered a number of casualties and stopped to reorganize, Pte. John Low and a fellow-member of “D” Company were among those volunteering in answer to the call for stretcher bearers. The two began crawling from boulder to boulder up the fire-swept slope, but after advancing 150 yards Low’s companion was wounded. In full view of the enemy the plucky Edmonton dressed his comrade’s wounds, and then dragged him behind a small rock that provided some cover.

To his comrades, the further advance of this soldier could only end in death, but to their amazement he continued on towards the wounded men. German fire appeared to centre around him. Bullets were seen kicking up the dust along the line of his path, but Pte. Low, showing intense devotion to duty and conspicuous bravery, successfully crawled the remaining 300 yards and reached the wounded men. In the open, and under what seemed to his platoon murderous fire, he dressed the wounds of each of the three in turn, found cover for them, and carried and aided them to it.29

Then, his task completed, Pte. Low made his way back to his company and resumed his first-aid work. He was awarded a well-merited DCM.

After its late start the Edmonton mule train, slowly following the infantry, ran into more trouble once it had crossed the river. Its leading section, consisting of 28 animals laden with the Support Group’s machine-guns, was badly scattered by artillery and mortar fire, and three of the guns were lost. The remainder of the convoy had a hard time finding the Edmontons, who were out of touch with Brigade Headquarters all day; not until the evening of the 3rd did it catch up with the infantry companies, bringing

them their 3-inch mortars and heavy wireless set, as well as much-needed water and rations.30

By the afternoon of 3 August Regalbuto had fallen, and now the Canadian Division’s efforts were to be concentrated on its left flank. At his daily conference General Simonds discussed his plan for the operations which would take the 2nd Brigade to the Simeto River. The Edmonton Regiment was to launch another attack that night towards Hill 736, to capture an intermediate spur, Point 344, about a mile south of the original objective. The rest of the brigade would advance down the Salso valley in three stages to secure on successive nights the line of the Troina, an equal bound along the eastern flank of Mount Revisotto, and finally the Simeto itself. During the operation Brigadier Vokes was to have the support of one squadron of the Three Rivers Regiment, a 3.7-inch howitzer battery, and the Division’s four*

* The 165th Field Regiment RA was still under command of the 1st Canadian Division.

field regiments.31

An hour before midnight the Edmontons’ “C” Company attacked Point 344, and in spite of stiff opposition won the peak in five hours. The rest of that day was spent in patrolling towards Hill 736 and the Troina River. The remaining companies of the battalion had taken no part in this action, for they were preparing for a subsequent phase of the brigade operation –the capture of Mount Revisotto.32

For the main advance of the 2nd Brigade Vokes put the Seaforth Highlanders in the lead, with orders to clear the right bank of the Troina River within the divisional sector. The battalion left its rest area near Agira at eight in the evening of 3 August, carried in motor transport. The route followed a very rough road which led north-eastward from Regalbuto to the point where the railway bridged the Salso. The Seaforth crossed the river on foot, and immediately afterwards engineers of the 3rd Field Company went to work. In four hours they had graded approaches to either end of the railway bridge and opened it to the passage of tracked vehicles. A few yards downstream they attacked the dry, boulder-strewn river bed with their bulldozers and levelled a roadway on which wheeled transport could travel. †

† A graphic record of the work of the Engineers at the Salso crossing and the Edmontons’ mule train is preserved in pictures by Captain W. A. Ogilvie, Canadian War Artist, who served with the 1st Division in Sicily.

This alternative crossing was completed by the afternoon of the 4th; but already a platoon of sappers had moved ahead, to begin building under fire a road across the four miles of uneven country to the Troina River.33

Under cover of darkness Lt-Col. Hoffmeister led his marching companies eastward along the north side of the Salso valley, bearing steadily towards the left into the high ground that edged the widening river flats. All vehicles had perforce been left behind on the south bank, but by considerable exertion on the part of a platoon detailed from the reserve rifle company a heavy 22 wireless set

was dragged forward on a handcart, in order that communications might be maintained with Brigade Headquarters. An hour before daylight the troops in the lead made contact with the Edmonton company in time to help in the clearing of Point 344; and as dawn broke they found themselves at the foot of their own objective, midway between Hill 736 and the Troina – “a high rugged hill topped on the left by a rocky crag jutting straight up to the clouds”.34 Hoffmeister ordered “A” Company to storm the position; and Major Bell-Irving decided to make a right flanking attack, mindful, no doubt, of the success which had attended a similar manoeuvre by his company outside Agira (see above, p. 131). The plan worked, and before the sun was high “A” Company, after a stiff fight with the defending Panzer Grenadier African veterans, had gained a footing on the southern tip of the objective.35 This success was exploited by “D” Company, supported by the Saskatoon Light Infantry’s machine-guns, most of the scattered mules having by now been rounded up. German snipers and machine-gun posts on the high crags at the north end of the ridge came under accurate 75-millimetre fire from two troops of Three Rivers tanks which had crossed on the railway bridge and made their way forward to the battalion area. By mid-morning the whole objective was in Seaforth hands.36

Like the river into which it emptied, the Troina in midsummer was a dry course thickly strewn with the boulders that winter torrents had tumbled down from its higher reaches. About a mile above its junction with the Salso, the river bed was less than two hundred yards wide, with sharply cut verges rising to the stony grainfields that spread across the adjoining flats. At a point where a break in the 20-foot left bank provided an exit from a rough fording place, a narrow mule track wound across the rising ground to join the Troina–Adrano road a little more than a mile to the east. Brigadier Vokes chose this site for a crossing, and ordered the Patricias to secure a bridgehead that night and cut the road beyond. The battalion crossed the Troina at half-past seven in the evening and encountered no opposition; for in the late afternoon a company of the Seaforth, supported by tanks firing from hull-down positions, had already successfully clashed with the enemy and driven him from the long spur which marked the PPCLI objective. Before dark the road was firmly held, and the first phase of the brigade’s operation against Adrano had been completed.37

The Thrust Eastward from the Troina, 5 August

The divisional conference held on 3 August had prescribed the capture of Mount Revisotto as the next stage in the 2nd Brigade’s advance, but by the afternoon of the 4th unexpectedly rapid developments in the wider field

of operations brought a modification of plan. The loss of Agira, Regalbuto, Catenanuova and Centuripe had forced the enemy to fall back from the Catania plain to his final defence line, and all across the 13th Corps’ front extensive demolitions and the blowing of ammunition dumps marked his hurried withdrawal northward. At a conference on the 4th General Montgomery issued instructions for “30 Corps on left to do the punching”,38 and that same afternoon General Leese discussed with his divisional commanders the course that this accelerated action should take. The Corps’ intention was to capture Adrano as quickly as possible, and then exploit northward towards Bronte. The 78th Division was to secure a bridgehead over the Salso north of Centuripe that night (4–5 August) and on the following night a crossing over the Simeto River north of its junction with the Salso. The 1st Canadian Division was to secure Mount Seggio on the night of 5–6 August and also push a bridgehead across the Simeto. The final assault on Adrano was to be made on the third night by the 78th Division, and should this venture fail, an attack would be delivered jointly with the Canadian Division 24 hours later. Throughout these operations the 51st Highland Division would continue to guard the Corps’ right flank and would match the final assault on Adrano by a drive on the neighbouring town of Biancavilla.39

A few hours before the 30th Corps conference the GOC 1st Canadian Division had ascended the steep Centuripe hill with General Leese, General Evelegh and his own Commander Royal Artillery, Brigadier A. B. Matthews.40 From this commanding height General Simonds had studied the whole area over which the forthcoming operations were to take place. The wide, closely cultivated plain formed by the junction of the Salso and Simeto valleys lay below him like a miniature model on a sand table. On his right, half a dozen miles to the north-east, the bleached tiled roofs of Adrano, the Corps objective, stood out clearly in the morning sun against the vast background of Mount Etna. In front of him the ground swept upward from the far bank of the Salso in rolling foothills to the peaks of Hill 736, Revisotto and Seggio, outposts of the great rampart of heights which filled the northern horizon. Below and to his left, a widening of the rocky bed of the Salso marked the entry of the Troina from its ravine-like valley west of Mount Revisotto. Along the floor of the valley at his feet the dry course of the Salso meandered eastward in wide loops to meet the fast-flowing Simeto River, which made its appearance from the north behind a long, outlying spur of Mount Seggio. Near the point where this spur flattened into the level plain the tiny hamlet of Carcaci stood on a slight mound among irrigated plantations of lemon and orange trees. Once a thriving community of more than a thousand inhabitants, Carcaci “had been reduced by successive epidemics of malaria to a population of less than one

hundred living in a mere handful of houses. Through these ran the road from Troina, to join Highway No. 121 a mile to the south-east, just before the latter crossed the Simeto and began its long zig-zag climb to Adrano.

On his return to his own headquarters General Simonds went forward to the 2nd Brigade’s command post for a discussion with Brigadier Vokes. His plan was for an infantry-cum-tank attack through the Troina bridgehead to be launched the following morning to link up with the 78th Division’s Salso crossing, which would be made at the site of the demolished highway bridge, some three miles below the Troina–Salso junction. For this purpose the GOC placed under Vokes’ command the Three Rivers and “A” Squadron of the 4th Canadian Reconnaissance Regiment.41

That evening (4 August), in a letter to Vokes, Simonds amplified his plan. He said that the 78th Division had crossed the Salso that afternoon, and was intending to push its reconnaissance force towards Mount Seggio in order to relieve pressure on the Canadian front.

I consider that once the feature Pt 332*

* The hill occupied by the PPCLI that evening.

in 6498 is in your hands and crossings across the River Troina are available, that a quick blow can be struck in the undulating country north of the river which will carry you right up to the western bank of River Simeto.

He went on to direct the organization of a striking force under Lt-Col. E. L. Booth, the Commanding Officer of the tank regiment, which would comprise in addition to the armour and the reconnaissance squadron an infantry battalion, a self-propelled battery of artillery, and one or two troops of anti-tank guns. Such a move would startle the enemy and would “probably result in a good mix up in the open country”, where the tanks would really be able to manoeuvre. The GOC foresaw the previously planned operations against Mount Revisotto and Mount Seggio as a follow-up to the mobile force’s effort. He concluded his letter:

You must be the final judge as to whether or not the local situation presents an opportunity for the blow I envisage, but indications today are that enemy resistance is crumbling, and I think we can afford to take bigger chances than we have been able to in the last few days.42

The original of General Simonds’ letter is attached to the 2nd Brigade’s war diary. A pencilled note in Brigadier Vokes’ handwriting has been added.

This letter arrived after 2300 hrs 4 August 43. Almost identical orders had already been issued by me and arrangements were already under way. No alteration was necessary. The attack was successful. 5 August 43 – C. Vokes Brig.43

The Brigade Commander selected the Seaforth Highlanders as the infantry component of the mobile force. Soon after midnight Hoffmeister met Booth. They drew up their plans and issued orders “in a deserted farm

house at 0200 hours under sporadic mortar fire and flares.”44 Tanks and supporting arms were to cross the Salso by the railway bridge and ford north-east of Regalbuto, and to join the Seaforth at the Troina crossing before first light. From this start line the whole force was to strike eastward at 6:00 a.m. through the vineyards and orchards between the Salso River and the Troina road. It would swing north of Carcaci and occupy the spur of high ground on the west bank of the Simeto. The column would be led by the Princess Louise squadron, followed in order by an engineer section, the Three Rivers’ “B” Squadron carrying the Seaforths’ “C” Company, a troop of the 90th Anti-Tank Battery, and “A” Squadron’s tanks, bearing “A” Company of the Seaforth. The remainder of the force was to follow in reserve. For artillery support Lt-Col. Booth could call on a self-propelled battery of the 11th Royal Horse Artillery, the 165th and the 3rd Canadian Field Regiments, and the 7th Medium Regiment (the rest of the divisional artillery was changing positions for the final assault on Adrano).45

It was eight o’clock before “Booth Force” pushed off, for the reconnaissance squadron had had difficulty in crossing the Salso railway bridge. Thanks to the efficiency of the engineers in clearing mines from the bed of the Troina, tanks, carriers and armoured cars reached the east bank without mishap. Thenceforward the advance proceeded as planned. With the Princess Louise in the lead, and the men of the Seaforth clinging to the following Shermans, the little force rolled briskly down the road towards Carcaci.

In rocky nests scattered over the objective troops of the 3rd Parachute Regiment with machine-guns and mortars awaited the oncoming Canadians. They held their fire until the leading carriers were about 500 yards short of the spur, in order (as revealed later by a German prisoner) to let the infantry come within effective range. But the two Seaforth companies had already dismounted farther to the rear, and now the Shermans of “B” Squadron “moved forward at best tank speed to the objective”, followed by the Seaforths’ “C” Company supported by the second tank squadron.46

It was about 10:30 when the Germans opened fire, and brisk fighting ensued. There was general agreement afterwards among participants and observers – including General Simonds, who with the Army Commander watched from the hilltop of Centuripe – that it was a model infantry-cum-tank action. Each arm gave the other excellent support. Although the enemy had the advantage of position, he was without anti-tank guns, having little expected an armoured attack from that quarter. According to the Three Rivers war diary “it was found that the best way to deal with them was to have the tanks scout around the terrain and clean out all suspicious looking places with 75 mm. HE and with blasts of machine-gun fire.” In some instances the tanks were able to burn the enemy out of his positions by igniting the tinder-dry grass and brush with tracer ammunition; then, as the

Germans broke from cover, small arms picked them off. Once during the morning the enemy attempted a counter-attack, trying to break through between the Canadians and the 2nd Battalion London Irish Rifles (of the 78th Division), who had occupied Carcaci. The effort failed. Subsequently Booth Force used to good advantage the services of a British FOO who was able to direct artillery fire from his point of vantage in the village.47

By noon “C” Company had gained a foothold on the southern tip of the objective and there were signs of enemy withdrawal to the north-east, although fire continued to come from his rearguard dispersed about the rocky spur. Hoffmeister (who rode in Booth’s tank during the action and was thus able to maintain control) sent “A” Company forward to exploit this first success by an assault from the extreme right flank. One by one the paratroop positions were methodically mopped up, the dogged defenders holding on, according to one observer, “to the last man and the last round”.48 Not more than a dozen prisoners were taken, and a signal received at Brigadier Vokes’ command post in mid-afternoon reported “many dead Germans found in area”.49 By comparison, Canadian casualties were light; ‘the reconnaissance squadron came through unharmed, while the tank regiment lost two men killed. The toll was heaviest on the Seaforth; their losses of eleven killed and 32 wounded were their severest since the opening day of the battle for Leonforte.

The operation by Booth Force had been completely successful. A late afternoon reconnaissance of the west bank of the Simeto, east of the newly-won high ground, disclosed that the enemy “had retired up the valley in sizable numbers and apparently in some disorder.”50 For the “dash and determination” with which he had carried out his task Lt-Col. Booth was awarded the DSO. (He was later killed in France while commanding the 4th Canadian Armoured Brigade north of Falaise.) The outflanking of Adrano had been achieved, however, by the cooperation of all arms and services, a point which General Simonds made clear in a subsequent radio interview.

This plain afforded the first bit of ground on which it was possible to employ tanks with maximum effect – and it was due very largely to the operations of the Twelfth Canadian Tank Regiment that we were able – so quickly – to gain the west. bank of the Simeto after crossing the Troina. In turn – it was the fine work of the sappers in building a crossing and tracks from the Salso to the Troina that enabled the tanks to get forward – and this crossing was constructed in spite of the fact that at times the men were under heavy artillery fire. Again the sappers could not start the crossing until the infantry, supported by guns, had gained a bridgehead and the operation as a whole could not have been undertaken unless the services and supply from behind had provided the means. What I want to emphasize is that all these operations have been successful because each arm and service has gone full out to do its share-and though the spectacular actions sometimes fall to individual units, and the infantry carry the brunt of the fighting, the ultimate success has resulted because of the contributions made by all.51

Mount Revisotto and Mount Seggio, 5–6 August

Of the tasks assigned to the Canadian Division west of the Simeto there remained by nightfall of 5 August the capture of Mount Revisotto and Mount Seggio. During the afternoon Hill 736 had fallen to The Edmonton Regiment. Earlier in the day “C” Company had captured an intermediate high point half a mile short of the main peak, which was held by an enemy force later estimated at 100 in strength. As the men of “C” Company were near exhaustion after four days of being under continuous fire, exposed to a blazing sun and with practically no sleep, two platoons of “D” Company were brought up to assist in the final assault. They attacked at 4:30 p.m., supported by the guns of the 3rd Field Regiment, a detachment of mortars, and two medium machine-guns which had been rescued from the scattered mule train. In spite of difficulties of communication between infantry and artillery – the passage of fire orders necessitated the improvisation of an elaborate chain of shouted commands and No. 18 wireless sets – the field regiment did what was wanted. Major A. S. Donald, the commander of “C” Company, who won the DSO for his part in the action, led his small force “up, across and around the bullet-swept feature into a position from which the height was assaulted and captured.”52 One of the encouraging features of the action, according to an Edmonton officer, was “that while one officer was killed and another badly wounded and both platoon sergeants were killed, the junior NCOs carried the attack through to success.”53

The wounded officer was Lieut. J. A. Dougan, who had shown such resourcefulness in directing his platoon at the road block on the Agira–Nicosia road on the night of 26 July (above, p. 130). His gallantry on Hill 736 brought him the Military Cross (he won a bar to it at San Fortunato Ridge in September 1944). While leading the forward platoon in the final assault he was wounded by machine-gun bullets in both arms and both hands. Eye witnesses recorded that “he could hold his revolver only by gripping it in both hands. Under intense pain he led the platoon across the 300-yard stretch of open ground under continuous observed fire, led the charge on the objective, and captured it.”54

Mount Revisotto and Mount Seggio were not occupied until the morning of 6 August. Heavy opposition encountered on Revisotto by the Edmontons’ “A” and “B” Companies during the 5th resulted in a decision to postpone the final attack until artillery support could be arranged.55 Late that same day the Patricias, to whom Brigadier Vokes had entrusted the capture of Mount Seggio, sent two companies forward from the Troina River to attack from the positions won by Booth, Force. shortly before midnight these reached the Seaforth headquarters, which had been established in an old

room at the back of a farmhouse. Here the PPCLI company commanders found Lt– Col. Hoffmeister “sitting on a dilapidated straw chair munching at some hardtack spread with jam and looking very tired.” They learned from him the situation on Mount Seggio as it was then known, and discussed their plan of attack.”56

The PPCLI force moved up to the area held by the forward Seaforth company, although their advance was somewhat delayed when they were given a lift by a relieving squadron of tanks which promptly lost its way in the darkness. Since Seggio was believed to be still held in strength by the enemy, the Patricias decided to postpone their assault until daylight, when they would have the benefit of artillery and heavy mortar support. But the Germans did not linger. When the Canadian attacks went in on the morning of the 6th, Mount Revisotto and Mount Seggio were taken without resistance.*

* The Brigade Commander afterwards gave his opinion that had the Patricias attacked Mount Seggio in battalion strength on the night of 5-6 August they might have carried their objective with disastrous results to the enemy withdrawal.57

The 30th Corps’ left flank along the line of the Salso was now secure.58

The fighting in the Salso valley was the Canadian Division’s last major operation in Sicily. It had cost the 2nd Brigade in the five days from 2 to 6 August more than 150 casualties. Hardest hit were the Edmontons. In the fighting for Hill 736 and Mount Revisotto they had lost 93, of whom 26 had been killed.

Kesselring’s report to Berlin on 6 August, concerned as usual to break bad news gently, forecast as a forthcoming possibility what was already an accomplished fact: “If correction of the situation in the sector of 15 Panzer Grenadier Division is not possible, Corps Commander will withdraw division to shortened ‘Hube’ position.59 This division had been charged with no light task. Its sector of defence between the Hermann Görings and the 29th Panzer Grenadiers faced the Canadians on its left front, and on its right stretched north across the inter-army boundary to cover the important Highway No. 120, control of which was vital to the withdrawal of all the German forces west of Mount Etna. This road was the central axis of the advance of the US 1st Division, and on it – just as the Hermann Göring Division planned to stop the Canadians at Regalbuto – the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division chose the mountain fastness of Troina for a supreme effort to halt the progress of the Americans.

The struggle for Troina has been described as “the Seventh Army’s most bitterly contested battle of the Sicilian Campaign”.60 For five days the town was under relentless attack by American infantry, backed by the fire of eight and a half artillery battalions and continuous aerial support from fighter-bombers and medium Mitchells and Baltimores. During that time the enemy, in a determined effort to keep open his life-line along Highway

No. 120, launched no fewer than twenty-five counter-attacks. By nightfall on 5 August, however, the Americans had a commanding hold of the high ground about Troina, and the town itself was taken next morning.61 Allied reconnaissance aircraft returning from patrols on the afternoon of 5 August reported very heavy enemy traffic pouring eastward towards Cesaro, and on the 6th it was apparent that the bulk of the German forces had pulled out from the Troina sector, leaving behind small groups to engage in stubborn rearguard action along the heavily mined highway.62 In the Canadian sector a hint of the disorganized nature of the general German withdrawal came from three German paratroops captured on the 6th, who declared that the enemy had broken up into groups of two or three, with instructions to make their way back as best they could to rejoin the main body of troops on the Adrano–Bronte road.63

The Halt at the Simeto

The telling blows delivered against the enemy’s western positions had produced the desired results on the Allied right flank. The best news on the Eighth Army front on 5 August came from the 13th Corps, which reported an unopposed occupation of Catania that morning by the 50th Division.64 Farther inland British troops surged forward against the line of foothill towns along Etna’s southern flank. At 4:55 p.m. Montgomery signalled the good news to Alexander:–

Have captured Catania, Misterbianco and Paterno*

* The announcement appears to have, been premature as far as Paterno was concerned. Although an Eighth Army Sitrep issued at 4:00 p.m. 5 August reported the town’s capture an hour before by the 13th Brigade (5th Division), the brigade’s war diary gives the time of its entry into Paterno as 10:15 a.m. on the 6th.

... on left leading troops 30 Corps now within 2000 yards of Biancavilla and within 1000 yards of Adrano. Am keeping up the tempo of operations and once Adrano is secured will strike rapidly towards Bronte and Randazzo.65

As the Eighth Army’s front narrowed, the convergence of the various divisional axes of advance necessitated a reduction in the number of formations engaged. With the fall of Adrano imminent the end of “Hardgate” was in sight; thereafter the 30th Corps’ zone of action to the west and north of Mount Etna would be restricted to a one-division front, that of the 78th. The 1st Canadian Division’s active participation in the Sicilian campaign was rapidly drawing to a close.

Its final operation was a bloodless crossing of the Simeto River by the 3rd Brigade on the night of 5-6 August. From their concentration area at Regalbuto the Royal 22e Regiment went forward by motor transport across the Salso and Troina Rivers, travelling the Canadian-built track which

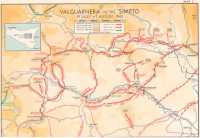

Map 5: Valguarnera to the Simeto, 19 July–7 August 1943

during the past few days had so effectively justified its construction. Near Carcaci the troops left their vehicles, and by seven in the morning they had secured a bridgehead across the Simeto without difficulty. They found the enemy’s machine-gun posts empty, and everywhere there was evidence of a hasty departure.66 Lt Col. Bernatchez quickly sent patrols northward and eastward, in a race with the 78th Division to reach Adrano. One 22e party reached the western outskirts of the town, but at 10:30 the Corps Commander intervened with orders that the 78th Division was to be given unrestricted entry. The Canadian battalion was withdrawn to the Simeto, and in the early hours of 7 August units from the 11th and 36th Brigades took possession of the devastated town.67 The Royal 22e was joined by the remaining units of the 3rd Brigade, while the advance battalions of the 1st Brigade, originally assigned a role of exploitation through the Simeto bridgehead (during the forenoon of the 6th the 48th Highlanders had followed early-morning patrols across the river), settled down temporarily in the area about Carcaci. The 2nd Brigade units were disposed on the Division’s left – the Seaforth moved back to the east bank of the Troina, while the Edmontons and the Patricias, remaining respectively on Mount Revisotto and Mount Seggio, continued during the 6th and 7th to patrol into the hills to the north and east.68

Relieved of operational responsibilities, the Canadian Division moved during 11–13 August to a concentration area at the southern edge of the Catania plain.*

* The Division passed into army reserve on 6 August, but remained under the command of the 30th Corps Headquarters until 10 August, when it became part of the 13th Corps.69

The 1st and 2nd Brigades found themselves on the high ground about Militello, not more than ten miles from Grammichele, where four weeks previously the Hastings and Prince Edwards had had the first Canadian encounter with the Germans. Divisional Headquarters and the 3rd Brigade settled about Francofonte, half a dozen miles to the east. It was a well-earned rest to which the Canadians came. In their month-long march through the interior of Sicily they had travelled 120 miles, much of it over rough and mountainous terrain, exposed to very trying conditions of dust and great heat, and opposed by a resourceful and determined enemy. Although lack of shade in their new surroundings meant little respite for the troops from the Dower of the sun, and there were complaints about the scourge of flies, the prevailing wind brought some relief from the heat, and the altitude helped provide safeguard against the malarial mosquito (see below, p. 176).

At midday on 10 August the Division came under command of General Dempsey’s 13th Corps, which three days later handed over all its operational responsibilities to the 30th Corps.70 Dempsey’s headquarters was withdrawn to prepare for the invasion of the mainland. Into reserve at the same

time came the 5th Division, which had been selected with the Canadian Division to take part in the forthcoming operation.

The Army Tank Brigade’s Part in HUSKY

The story of Canadian operations in Sicily would not be complete without a brief account of the activities of the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade. We have followed the fortunes of one unit of this formation – the Three Rivers Regiment, which played so vigorous a part in the advance of the 1st Canadian Division from the Pachino beaches to the Simeto River. The remainder of the brigade (consisting of Brigadier Wyman’s headquarters, The Ontario Regiment, The Calgary Regiment, and certain appropriate Medical, Ordnance and Army Service Corps sub-units) had sailed to Sicily, it will be recalled, in the follow-up convoys. On the evening of 13 July LSTs of the slow convoy disembarked their tanks at Syracuse, and these moved to a harbour area near Cassibile, nine miles south-west of the port. The personnel ship Cameronia of the fast convoy docked four days later, and the troops marched into camp that same evening.71

The brigade (less the Three Rivers), now part of the Eighth Army Reserve, was placed under the command of the 7th Armoured Division, whose commander, Maj-Gen. G. W. E. J. Erskine, had arrived from Tripoli on 14 July with a small tactical headquarters to advise the Eighth Army on the employment of its armoured forces.72 For a week the Canadian formation remained in the Cassibile area, becoming acclimatized and adjusting itself to its forthcoming role. Nightly enemy air raids on Syracuse brought a “stand to” every morning at five, when all units went on the alert “with kits completely stowed, vehicle engines running and everything in readiness for instant movement or action should such occur.”73

Early on the morning of 21 July, the brigade began to move forward to positions four miles north-east of Scordia, in the Contrada* Cucco, a district lying along the southern escarpment of the Catania plain, south of the Gornalunga River (see Map 1). Its role here was to cover a ten-mile gap between the two corps of the Eighth Army, which were then holding a defensive line along the Dittaino River. On the 23rd units deployed into their new positions ready (as confirmed in a brigade operation order dated 27 July) to “destroy all enemy attempting an attack between the left flank of 13 Corps and the right flank of 30 Corps.” Ahead of the Canadian armour the 5th Division’s reconnaissance regiment was patrolling the area between the Gornalunga and the Simeto Rivers, and on its right a strong anti-tank screen was being maintained by the’ guns of the same division’s anti-tank

* Region.

regiment (105th). The Canadian task was to support these two units, and “to be prepared to fight an armoured battle” should occasion arise. But no German attack developed, and the end of the month brought further dispersal of the brigade’s units for the final phase of the campaign.

On 31 July, as the 30th Corps began the preliminary operations to “Hardgate”, The Ontario Regiment, commanded by Lt-Col. M. P. Johnston, was placed in support of the 5th Division’s 13th Brigade, which had been given the task of defending two crossings of the Dittaino at Stimpato and Sferro, on the extreme western flank of the 13th Corps. The Canadian Tank Brigade had come under the command of this Corps on 28 July, when the Tactical Headquarters of the 7th Armoured Division returned to Tripoli after its brief stay in Sicily.74 The brigade, less the 11th and 12th Regiments, retained its defensive role near Scordia, taking temporarily under its command the 98th Army Field Regiment (SP) RA, a squadron of the 1st Scorpion Regiment,*

* “Scorpions” were modified General Grant tanks with special whip-like attachments for clearing paths through minefields.

and a troop of a British light anti-aircraft battery. As the 51st Highland Division pushed the 30th Corps’ right flank forward across the Dittaino River, squadrons of The Ontario Regiment supported units of the 13th Brigade in a parallel advance towards the north-east.75 The Gerbini aerodrome was taken on 4 August, and on the sixth the 13th Brigade entered Paterno without opposition (above, p. 164).

The general enemy withdrawal continued, and the 5th Division, as the left flank formation of the 13th Corps, found itself operating in the difficult terrain of the foothills south-east of Etna and on the lower slopes of the volcano itself. The steep gradients, rocky terraces and rough, hummocky fields of black lava made it impossible in places to deploy off the roads, and the Division was forced to advance on a single brigade front. Demolished bridges hampered the progress of the armour, which was chiefly used to beat off small-scale but vigorous counter-attacks launched against the infantry by persistent German rearguards.76 On 7 August Belpasso was taken, and Nicolosi, high up on the magnificent autostrada which swept half way to the summit of Etna. On the 9th General Montgomery decided to adopt a more aggressive role for the 13th Corps, whose task until now had been to follow up and keep contact with the enemy without becoming involved in a major operation and sustaining heavy casualties. He ordered the Corps to drive forward on a two-divisional front along the narrow defile between Mount Etna and the sea, in order to cut the lateral road running north of the volcano from Fiumefreddo to Randazzo.77

On the left the 13th Brigade led the 5th Division’s advance northward along the mountain road which clung to the eastern slopes of Etna, 2000 feet above sea level. An Ontario squadron supported the 2nd Cameronians

near the village of Trecastagni on 9 August, and next day its tanks assisted the infantry in seizing a bridgehead north of Zafferana Etnea and beating off an enemy counter-attack.78 This action ended the Sicilian operations of the Canadian Tank Brigade, and indeed of all Canadian troops in Sicily, for Montgomery now decided to disengage the 5th Division in preparation for the forthcoming operations on the Italian mainland, and, as we have seen, the 1st Division had been withdrawn into reserve on 6 August. At midnight on 10–11 August The Ontario Regiment reverted to the command of the Army Tank Brigade, and moved southward to join its parent formation near Scordia, in the area that The Calgary Regiment had continued to occupy since the end of July.79 The Three Rivers Regiment had already arrived from its tour of service with the 1st Division, and for the first time since leaving Scotland all the Canadian armoured units were concentrated together. The casualty lists for the three tank regiments reflect the different operational roles which each had been called upon to undertake. The Calgaries had only eight wounded in Sicily; the Ontarios one killed and 13 wounded; while the Three Rivers Regiment, which was in almost continual action throughout the campaign, lost 21 killed and 62 wounded.

The brigade now came directly under the 1st Division, as it was desirable (said the brigade war diary) “to centralize the Canadian command so that there will be uniformity of policy on all Canadian matters”.80 There was opportunity now for appraisal of past performances and a critical examination of the many special administrative problems arising from the fact that individual tank regiments, or the brigade itself, might be detached and placed under the command of other formations. Such situations were bound to recur in the future; at a conference between General Simonds and Brigadier Wyman on 12 August it was announced that the brigade “would be maintained as a separate formation ... ready to move under command of any other formation and able to stand on its own feet.”81 The story of the brigade’s subsequent operations in Italy shows how accurately this forecast its future role.

The German Retreat from Sicily

When the 1st Canadian Division halted at the Simeto, the fighting in Sicily was almost over, for with the breaking of the enemy’s main defensive line began the final stages of his retreat to the mainland. According to von Bonin, on 8 or 9 August the Commander of the 14th Panzer Corps, influenced by the rate at which his divisions were daily losing ground, and by the critical shortage of supplies, established 10 August as “X Day” – the date on which the general retirement was to commence. On the 10th

Kesselring told Berlin: “The evacuation of Sicily has started according to plan.”82

This plan of withdrawal had been prepared at the 14th Panzer Corps Headquarters with characteristic German thoroughness. On the day after Mussolini’s deposition Hitler, bowing to the inevitable, had issued orders to OB South “to make preparations for the evacuation of German troops from Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica”,83 and, as we have seen, General Hube had taken prompt measures to secure an escape route across the Messina Strait. From his Chief of Staff we learn that the plan for the final evacuation was based on an appreciation that six nights

* On 29 July Kesselring reported to Hitler that it would be possible to evacuate Sicily in three nights.84 Hube’s decision to take six nights reflects the thoroughness of his planning and suggests his intention of withdrawing as much equipment as possible.

would be required to transport with the boats available the approximately 60,000† German troops

† This is the figure given by the Armed Forces Operations Staff on 18 August. Von Bonin, relying on memory, put the total at 50,000.

who were on the island. Hube designated five lines of resistance converging on Messina, to be occupied on successive nights and held for one day each. The first of these lines was to the rear of the “bridgehead position,” and ran from the north coast just east of Sant’ Agata, through Bronte and around the southern slopes of Mount Etna to Acireale. The last was just outside Messina. It was planned that on each withdrawal a total of eight to ten thousand men would be released from the three divisions, and moved on foot towards Messina. The Hermann Göring Division would go first, to be followed in order by the 15th and the 29th Panzer Grenadier Divisions. From the fifth line of resistance the last remaining troops would march direct to the boats on the final night of evacuation. Late in July operations officers of the German divisions in Sicily were flown to Kesselring’s headquarters in Rome to discuss the plan of evacuation (Operation “Lehrgang Ia”), which would go into effect at a time to be decided by the Commander of the 14th Panzer Corps.85

This action by OB South came while the German High Command, in spite of its warning order of 26 July, was still debating whether to continue the defence of the Sicilian bridgehead. The record of Hitler’s naval conferences shows that as late as the evening of 11 August (when the evacuation plan had actually been in operation for 24 hours) Admiral Dönitz and Field-Marshal Rommel were arguing that to abandon Sicily would release strong Allied forces for thrusts into Southern Italy; while holding the opposite view was General Jodl, who pressed the need for abandoning the island in order to concentrate German formations against an assault landing near Naples. Hitler himself made “no definite decision” but asked “to have the various solutions considered as possible choices.”86 Kesselring got no thanks for presenting the High Command with a

fait accompli. “I was for a long time persona ingrata”, he writes in his Memoirs, “because I took the decision to evacuate Sicily on my own initiative.”87

Although details of the German scheme for withdrawal were not, of course, known at the time to the Allied armies, it was correctly appreciated that the enemy would attempt a slow retreat to Messina, fighting for time in which to extricate the maximum number of his forces from Sicily. In this he was once again favoured by the topography of the island. The tapering conformation of the Messina peninsula admirably suited his scheme of thinning out his forces on shortening lines of resistance, while the mountainous terrain restricted the pursuing formations to the use of the few existing roads, progress on which could easily be blocked by demolitions and the action of light, mobile rearguards. As a result the Allies were unable to upset Hube’s time-table; indeed, by holding one of his intermediate defence lines longer than originally planned, he contrived to gain an extra night and day* for the evacuation of his divisions.88

* The Germans occupied the first line of resistance on the night of 10–11 August; the fifth, outside Messina, on 15–16 August.

The story of the Allied pursuit can be quickly told. After the capture of Adrano, the Eighth Army’s 78th Division pressed northward in the 30th Corps’ narrow field of operations west of Mount Etna. The axis of advance lay between the high, trackless slope of the volcano and the deep gorge of the upper Simeto, along a route which gave the enemy full scope for his delaying tactics. Bronte fell on 8 August, but thereafter General Evelegh’s troops met strong German resistance, so that they did not take Maletto, only four miles farther north, until the 12th. Next day they reached Highway No. 120, and assisted the US 9th Division, moving eastward from Troina, to capture badly battered Randazzo, long a major target of the Allied air forces.89

On the Eighth Army’s right flank progress was equally slow, for in the narrow defile of the coastal strip the Hermann Göring engineers had blocked the roads with every conceivable obstacle. It took the 50th Division a week to advance sixteen miles from Catania along the main coastal highway to Riposto, which was entered on 11 August. On the 13th Corps’ inner flank the 5th Division kept abreast, supported until 10 August by Canadian tanks. It was relieved by the 51st Highland Division on the 12th when, as we have seen, General Leese’s 30th Corps took over control of the operations of the three divisions remaining in action. By 14 August the enemy had broken contact all along the front, and the rate of pursuit was now governed entirely by the speed with which the Engineers could reopen the blocked routes. On the 15th the 50th Division reached Taormina, whose famous Greek ruins had happily survived their latest war unharmed, and

on the same day the 51st and 78th Divisions completed the circuit of Etna and joined forces near Linguaglossa.90

Meanwhile, on the Army Group’s northern flank, General Patton’s forces had been driving into the Messina peninsula and meeting the same delaying resistance. The 9th Division, forming the 2nd Corps’ right wing, had relieved the battle-worn 1st Division after the struggle for Troina, and had pushed forward along Highway No. 120 on the heels of the retreating enemy. The Americans entered Cesaro on 8 August, and five days later, as we have seen, captured Randazzo. This was the last strong German position on the Seventh Army’s southern axis, and its fall marked the end of the 9th Division’s advance.

The US 3rd Division led the drive along the northern coast road. During the first week in August it encountered “numerous demolitions, mines, and sporadic artillery fire”, and at times “stiff, determined opposition”.91 Early on 8 August it carried out a successful amphibious operation against the enemy rear, when a party comprising an infantry battalion, a tank platoon and two batteries of artillery, landed east of Sant’ Agata and broke resistance on the strongly held Mount San Fratello. Three nights later the same force repeated its success in a landing two miles east of Cape Orlando, near Brolo, thereby outflanking and ending the German hold on the important junction of the coastal highway with the lateral road from Randazzo. By 15 August, as in the other sectors, contact with the enemy had virtually ceased. Indeed the tempo of the pursuit had so quickened that a third amphibious operation, which had been planned to take place early on the 16th east of Milazzo, was diverted to beaches north-west of Barcellona in the Gulf of Palli when its intended point of landing was outdistanced by the troops advancing overland.92

Messina fell on 17 August – 38 days after the first Allied landings in Sicily. American infantry of the 3rd Division, cutting across the tip of the peninsula, pushed into the city shortly after 6:00 a.m. (some patrols had reached the outskirts on the previous evening), and four hours later British tanks of the 4th Armoured Brigade and men of No. 2 Commando, who had landed ten miles down the coast near Scaletta on the night of the 15th–16th, arrived from the south.93 During the morning General Patton himself entered Messina, to mark the successful conclusion of an advance which General Eisenhower later described as “a triumph of engineering, seamanship, and gallant infantry action.”94 The first United States field army to fight as a unit in the Second World War had worthily accomplished the mission assigned to it.

The Allies found Messina empty of German troops; early that morning General Hube had crossed the Strait with the rearguard of his island garrison. The naval officer in charge of the crossings, Commander Baron von Liebenstein, won high praise from Hube for not having “given up a

single German soldier or weapon or vehicle to the enemy.” Von Liebenstein employed a variety of craft for the job, shuttling the bulk of the troops and equipment across the Strait in seven Marinefährprähme (80-ton ramped barges, each capable of carrying three tanks or five trucks), ten “L”-boats (army engineer pontoon “landing-boats” that could take two trucks), and eleven Siebel ferries. These last were double-ended motor rafts built to carry ten trucks or 60 tons of supplies. Originally designed for the invasion of Britain in 1940, several of these craft had been dismantled and transported across France to the Mediterranean in the early summer of 1943. Most of the crossings were carried out by daylight because of the greater fear of night attacks by Allied bombers using flares.95

Considerable credit for the successful evacuation must go to the resourceful Colonel Baade, whose job it was to defend the escape route across the narrow channel against Allied sea and air attack. As early as 3 August General Alexander had warned Admiral Cunningham and Air Marshal Tedder of the possibility of the Germans beginning to withdraw to the mainland before the collapse of their front in Sicily. “We must be in a position to take immediate advantage of such a situation by using full weight of navy and air power,” the C-in-C signalled.96 However, although light coastal patrols of the Royal Navy operated in the Strait every night, the restricted waters, covered by some 150 German 88-mm. and Italian 90-mm. mobile guns supplementing the fixed coastal batteries, prevented successful daylight intervention by Allied naval forces;97 and intensive efforts by heavy, medium and fighter-bombers to disrupt the flow of men and materials to the mainland were frustrated by the protective canopy of fire put up by Hube’s well-sited flak and coastal guns. From 8 to 17 August inclusive 1170 sorties were flown against the enemy’s evacuation shipping in transit and off the beaches, but the estimated casualties inflicted were not high. In the opinion of some RAF pilots98 the anti-aircraft defences of the Messina Strait exceeded in density those of the Ruhr. Some critics have asserted that Allied naval and air forces might have been used more effectively to impede the German evacuation. The US Naval Historian thinks that “the Strait looked too much like the Dardanelles to British commanders who had been there, and to Americans who had studied the Gallipoli campaign in their war colleges”; and in Kesselring’s view,

The enemy failure to exploit the last chance of hindering the German forces crossing the Straits of Messina, by continuous and strongly coordinated attacks from the sea and the air, was almost a greater boon to the German Command than their failure immediately to push their pursuit across the Straits on 17 August99

Three days before he left Sicily Hube sent Kesselring some “suggestions for the final communique after the conclusion of the evacuation”. The “main idea” would be “to describe battles in Sicily as a big success.” This would

“raise morale and confidence at home and create pride in the Sicilian formations.” Recalling that “the catastrophe of material at Dunkirk was presented to the British public as a great success”, he proceeded to demonstrate that with a favourable conclusion of the evacuation

... the end of the Sicilian campaign is actually a full success. After the initial fiasco, the fighting, as well as the preparation and execution of the evacuation, with all serviceable material and men (including the wounded) went according to plan.100

Hube lauded the work of his anti-aircraft units, but recorded sharp objection “to any possibly intended mention of the Air Force as giving immediate assistance to the troops on the ground”, who “had practically to rely entirely upon themselves in their battles against the enemy on land and in the air.” He submitted that praise for Italian troops could “only be justified in the case of the artillery”, and concluded with this pointed observation:

I consider it as especially harmful when, as happens time and again, one encounters communiques that do not correspond in any manner with the actual situation ... and that appear ridiculous to those who were there.

Kesselring took his cue correctly, and his report on the campaign contrasted the British evacuation at Dunkirk, when “even though most of the personnel was taken across successfully, the army lost its entire armament”, with the retreat from Sicily, when “all serviceable material of value was taken, as well as the complete German formations, which are now again ready for immediate service on the Italian mainland.”101 According to the figures prepared by OB South for submission to Berlin, 39,569 German troops (including 4444 wounded) were ferried back from Sicily during the first fifteen days of August, and they took with them 9605 vehicles, 47 tanks and 94 guns, besides more than 17,000 tons of ammunition, fuel and equipment.102

These statistics are difficult to challenge;*