Chapter 8: The Sixth Day: 25 May

The Attack on Galatas

Although General Ringel had not felt strong enough to launch a general assault on 24 May, the day had not been wasted. More mountain troops landed at Maleme, among them III Battalion of 85 Mountain Regiment and RHQ. The 95th Mountain Reconnaissance Battalion, an AA MG company, a signals unit, and a cycle company made up the rest. III Battalion was apparently at once hurried off to Alikianou, where the opposition seemed formidable enough to hold up for the time being a planned drive through the mountains to relieve the Retimo paratroops and cut off Suda Bay.

On the main front the paratroop artillery and 95 Artillery Regiment had taken up positions near Platanias and Ay Marina from which to support the general assault on the Galatas line; and the infantry units had completed their preliminary reconnaissance.

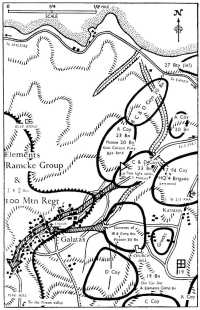

At 7.15 p.m. on 24 May Ringel issued his orders for the next day. The attack was to be twofold. Krakau Group – I and III Battalions of 85 Mountain Regiment – would take Alikianou and the area east of it. It would then push on south of Suda Bay and ultimately cut the road from Canea to Retimo. But the main thrust would be carried out by 100 Mountain Regiment1 and Ramcke’s paratroops. The first would capture Galatas and the high ground south of it. The second would attack simultaneously on the front north of Galatas but would leave a strong force in reserve. Heidrich’s paratroops would advance south of the Prison-Canea road, keeping contact with 100 Mountain Regiment on the left and 85 Mountain Regiment on the right.2 the 95th Artillery Regiment would support Ramcke’s paratroops and the left of 100 Mountain Regiment, though ready to support the right flank of the Division as well if necessary. The 95th Reconnaissance Battalion and 95 Anti-Tank Battalion would be in position to follow up the attack.

The orders also provided for the clearance of the areas west and south of Maleme. The 95th Engineer Battalion was to look after Kolimbari, Kastelli, Platanos and Topolia, while 55 Motor Cycle Battalion took Palaiokhora and held it against any attack.

The units in the main attack were recommended to avoid frontal assaults wherever possible and to bypass Canea in favour of a swift onward drive to Retimo. The latter provision indicates the enemy’s concern for his troops at Retimo; the former suggests that Student’s criticism of Ringel’s tendency to prefer encircling movements which would save blood but not time may have had some substance.3

Air support, which 100 Mountain Regiment had already said would be necessary, was also arranged. There were to be heavy attacks on Alikianou and Galatas at 8 a.m., and again on Galatas at 12.45 and 1.15 p.m.

Zero hour for the attack on Alikianou was to be 8 a.m. and for that on Galatas 1.20 p.m. This latter was left so late in order to ensure that artillery support and co-operation with the flanks would not be lacking.4

These orders set the stage for the day of 25 May. And as progress now warranted his presence Student himself arrived at Ringel’s HQ early that morning. The attack was not likely to lack élan with him to spur it, and shortly after his arrival he visited the Assault Regiment, his chosen favourites.5

Among the defenders of the Galatas line no one deluded himself that the day would be anything less than a grinding test. Brigades were warned, and in turn warned their battalions, that a determined attack was to be expected. Fourth Brigade already had its authority to call direct on 5 Brigade for support and at 6.20 a.m. was warning Brigadier Hargest that 23 Battalion might be wanted that morning. And the remaining tanks of C Squadron, 3 Hussars, had come under command at 3 a.m.

Indeed there were good grounds for uneasiness. On the main front the opposition consisted of two relatively fresh battalions of mountain troops, the remains of the Assault Regiment – reorganised and strengthened with artillery – and what was left of 3 Parachute Regiment, perhaps two battalions. In addition the enemy had the support of an artillery regiment and all the air attack the sky could find room for. And he had reserve troops to follow up.

Against this powerful force the New Zealand Division had in the front line where the blow was to fall only one reasonably fresh battalion, 18 Battalion; and this was down to a strength of about 400. The rest of the line was patched up with non-infantry ad hoc formations; and, although the men in these units were of excellent human material, they were untrained as infantry and had already been in the line ever since the battle began six days before. The 19th Battalion, although not in the main path of the assault, could not be moved without creating a gap, and the same was true of the two Australian battalions – of which one, it should be remembered, was only two companies strong. In immediate reserve there were only the ‘infantillery’ of 5 Field Regiment and the RMT group from the Composite Battalion; for the rest of that battalion were by now part of the front line. The 20th Battalion, much under strength and tired from severe fighting near Maleme, was in second reserve near the Galatas turn-off. The 23rd Battalion and the 28th could be called on from 5 Brigade; but both had had days of heavy fighting and their share of casualties.

There would be no air support. And the artillery, few in guns and low in ammunition, suffered from bad communications and poor observation. Finally, as has already been seen, there were dangerous weaknesses in the dispositions of 18 Battalion.

The enemy had probably spent a good part of the night in getting his guns, mortars, and machine guns into position. Even before daylight there had been desultory concentrations of fire from the machine guns against the front line, and some idea of their number may be gained from the fact that a patrol sent out at 4 a.m. from B Company of 18 Battalion met fire from 18 counted machine guns.6

But the morning passed and the expected attack did not come. As they waited the defenders had to endure a continued and severe drubbing from machine guns, mortars, artillery and aircraft. D Company 18 Battalion alone had 19 casualties; and this though the men were in trenches, if poor ones. But there was at least some chance to retaliate: the enemy was still building up for his attack on the north flank and D Company did good execution on parties advancing along the coast road. More still might have been done if it had not been for the shortages which were the plague of the battle. Thus at one stage during the morning Lieutenant-Colonel Gray found his supply of mortar bombs down to ten and had to borrow thirty more from Colonel Kippenberger, the last he had. What they could do, however, the mortars did, ably

seconded by the artillery and machine guns. Those of the latter with Lieutenant Rawle, on the right of C Company, did particularly good work in keeping the enemy off the forward slopes and crest of Red Hill.

There was no lack of good cover for the enemy’s mortars and machine guns, however, in the olives, on Ruin Hill, on reverse slopes, and in the network of gullies to the west. And as the day went on their fire moved towards a peak which coincided with the first probing attacks by the infantry. Pressure began to develop, and it became apparent that the main thrust could be expected anywhere between the right flank of Russell Force – which had been having trouble near Pink Hill – and the right flank of 18 Battalion, the positions held by D Company. In fact, by about two o’clock in the afternoon, if not earlier, all the forward companies of 18 Battalion and the Petrol Company were under attack.

In this early stage the Petrol Company, aided by enfilade fire from the Divisional Cavalry, was able to prevent enemy progress in the Pink Hill area. The attack against A Company 18 Battalion, to the right of the Petrol Company, occasioned some stern fighting. The enemy’s design was probably to get possession of Wheat Hill so as to bring fire to bear on 18 Battalion’s positions on Murray Hill and those of the Composite Battalion on Ruin Ridge. For the time being their thrust was held, but as the afternoon wore on it grew dangerous enough to make Gray send Captain Bliss with a detachment of men from the Supply Company to A Company’s support.

Although some approach was also made against the front of C Company in the centre of the line it was beaten off by 15 Platoon, and it may have been no more than an attempt to pin the company down while the more serious attack on Wheat Hill was going in. For if the latter were effective, C Company’s position could be made untenable by a drive in from its southern flank.

The attack in the northern section of 18 Battalion’s line, like that on Wheat Hill in the south, was pushed hard and may have had the same object of isolating the centre. On the other hand, the fact that the fighting here was very fierce may merely be attributed to the presence of Ramcke’s paratroops. At all events the attack was serious enough during its first hour for Gray to send up a reserve platoon of gunners under Captain Kissel. As this platoon came forward it ran into trouble on its own account and lost casualties to a machine-gun fusillade. But meanwhile D Company seemed to have beaten the enemy off temporarily and Kissel’s platoon installed itself on the forward slopes of Murray Hill, to the left rear of D Company.

All was not really well, however, on the D Company front. The assault had begun with a sudden intensification of machine-gun fire and an equally sudden cessation of air attack. The front positions were on forward slopes, and as the enemy had also begun to use Bofors against them, Captain Sinclair,7 who commanded the company, went out to see how it was with his men. ‘I could shout and then get a man to hear me and see him turn his head round and signal he was all right.’ If we add to the intensity of small-arms fire necessary to produce such a storm of sound the fact that shells and mortar bombs were bursting at the rate of perhaps twenty a minute on the battalion front,8 we get some conception of the volume of fire.

At 3 p.m. Sinclair observed enemy moving in a re-entrant near Red Hill but, as he attempted to have fire brought down on them, was himself wounded. From this point he was succeeded in command by Second-Lieutenant Robinson.9 Robinson, finding his forward platoons hard pressed, attempted to reinforce them with his reserve platoon and men from Company HQ. But before he could finish doing so he was killed by a grenade and the attempt broke down.

It must by now have been about four in the afternoon and the enemy had begun to throw in his full weight. A frontal attack on the D Company positions coincided with the attack from Red Hill towards the left rear. A runner with the news reached Gray almost at once. He hastily collected some twenty to thirty men – military police, batmen, intelligence staff, clerks, storemen, gunners and men from the Supply Company. The scene is well described by R. T. Bishop,10 a corporal in the carrier platoon which, about twelve men strong, was holding a forward slope behind D Company. Some D Company posts at the seaward end of the line had just been overrun and had surrendered when Gray ‘hove in sight armed with rifle and bayonet and leading perhaps 20 men and yelling to Don Company “No surrender. No surrender.” Sergeant Scott asked if we were to join in but was told to wait for the second wave. However, he took half a dozen men with him and left almost immediately, the rest of us following. We had just got to the top of the ridge when we met the CO coming back, Sgt Scott and others having been killed.’

The gallant and hopeless counter-attack had failed. Its members were few and motley, the enemy numerous and better armed. All it may have done was to hold the enemy back a little longer. The greater part of D Company was already beyond rescue. Only eleven men under the quartermaster-sergeant got away.

Captain Bassett gives a good impression of the scene:

In the afternoon he came again in full blast against Gray’s right and as our wire to him was cut by bombs I offered to go through and check up. It seemed an easy job, but I was no sooner out than flights of dive-bombers made the ground a continuous earthquake and Dorniers swarmed over with guns blazing incessantly. It was like a nightmare race dodging falling branches, and I made for the right Company and got on their ridge, only to find myself in a hive of grey-green figures so beat a hasty retreat sideways until I reached Gray’s HQ just as he was pulling out. I had to admire the precise way he was handling the withdrawal – he greeted me with ‘Thank God Bassett, my right flank’s gone, can you give us a vigorous counterattack at once’, and I promised to put in the two 20th Companies and he insisted on my taking a signaller with me in case I got hit. A bomb landed amongst us and after the scatter I couldn’t find his hide-out, so set [off] back alone, all the time feeling a bullet drilling me in the back from the ground or through the head from the air. My way led through the town, and I found all our sectors undergoing the same massed attack.

A nest of snipers penetrated into the houses, pelted at me and a Stuka keeping a baleful eye on me only (or so it seemed), cratered the road as I scuttled. I reached Kip breathless, the officers were with him, and within a minute rushed off to lead their companies in.11

Before Bassett’s return Colonel Kippenberger had heard that D Company was in difficulties and had ordered Gray to counterattack with Headquarters Company and Bliss’s gunners. But there had been no time for Gray to do more than organise the emergency counter-attack already described, and the only chance now lay in the two companies which had been organised from the remnants of 20 Battalion’s B, C, and D Companies. These two companies, commanded by Captain Fountaine12 and Lieutenant O’Callaghan,13 had been sent up that morning by Brigadier Inglis and were in reserve, about 140 men strong, under the olives just north of Galatas.14 they had been bombed and strafed during the afternoon for the best part of an hour but had had no casualties.

Bassett’s return confirmed that the situation was desperate. If the enemy broke through on the right flank he would have the shortest route to Canea. Kippenberger therefore ordered the two commanders to rush their two companies to the right of Ruin

Ridge. ‘Fountaine and O’Callaghan ran out, stooping under the stream of “overs”. They got into position, finding the Composite Battalion nearly all gone though it had only been getting “overs”, and hung on grimly. For the rest of the evening it was a comfort to hear their fight going steadily on.’15

This move left Kippenberger without further reserves. And reserves were already needed. For a determined attack on A Company had now begun to make headway. Twice runners had been sent from Wheat Hill to get permission to withdraw. Twice the permission was refused.16 But finally the pressure was too great: A Company and its attached troops began to fall back. This left C Company and the supporting platoons of B Company alone.

Soon Major Russell reported that he, too, was hard pressed. The flanking fire his men and also Lieutenant Dill’s platoon on Pink Hill had been bringing down on the main German attack had been so successful that special artillery concentrations had been called for by the enemy to deal with them. And I Battalion of 100 Mountain Regiment was also trying to force a way to Galatas through his positions.

The telephone system had been almost destroyed by bombing and there was no line to 4 Brigade. So, as soon as Bassett had given his message about D Company, Kippenberger sent him on to report to Brigadier Inglis and urge all possible reinforcement.

Already there was a trickle of stragglers, a sinister symptom. The RAP was full of wounded and trucks were running the gauntlet to get them away. And hardly had Bassett gone when it became clear that A Company had been forced off Wheat Hill. This left in the foremost line only C Company and small groups like Lieutenant Rawle’s and the platoons of B Company. Here the weight of attack had been steadily increasing, though the machine guns in Rawle’s detachment and the riflemen in B Company did splendid work keeping down any frontal attacks across Red Hill. But with right and left flanks torn open by the going of D and A Companies and with fire pouring in from three sides, and especially from Ruin Hill, it was obviously impossible to hold out much longer. About

7 p.m. Major Lynch, commander of C Company, felt the situation was desperate and sent a message by runner to Lieutenant-Colonel Gray, asking permission to withdraw. Gray, whose own HQ was in imminent danger of being overrun, sent the runner back: Lynch was to hang on for another hour if possible. It was a quarter of an hour before the runner found Major Lynch, who was up in the forward trenches with a rifle. By this time the enemy seemed to be everywhere around the company. To remain any longer Lynch saw would be to throw away his company. He therefore arranged a covering party, who held off the enemy almost at arm’s length, and the company withdrew in good order.

Meanwhile the enemy had also got behind the B Company positions. No. 11 Platoon was almost wiped out and the survivors of 5 and 10 Platoons had no choice but to retire, with mortar bombs bursting about them and machine-gun fire all around.17 the various detachments of gunners and Divisional Supply in the same area, in similar danger, had to do the same.

By holding on so long there is little doubt that these resolute troops prevented a breakthrough in the centre which would have overwhelmed Battalion HQ and might have carried on with even more serious results. Even so the position was bad enough. The withdrawal was now general and in danger of becoming a rout. Some found their way back towards Galatas. Others fell back on Ruin Ridge and were rallied by Gray near a stone wall that ran alongside the road north from Galatas. As some of C Company came up Colonel Gray halted them: ‘“Ah, C Company, we’ll make a stand.” And make a stand we did.’18 As soon as this was organised Gray went off to find Colonel Kippenberger.

Kippenberger had meanwhile also been trying to dam the tide. ‘Suddenly the trickle of stragglers turned to a stream, many of them on the verge of panic. I walked in among them shouting “Stand for New Zealand!” and everything else I could think of. The RSM of the Eighteenth, Andrews, came up and asked how he could help. With him and Johnny Sullivan, the intelligence sergeant of the Twentieth, we quickly got them organised under the nearest officers or NCO’s, in most cases the men responding with alacrity. I ordered them back across the next valley to line the ridge west of Daratsos where a white church gleamed in the evening sun. There they would cover the right of the Nineteenth and have time and space to get their second wind. Andrews came to me and said quietly that he was afraid he could not do any more. I asked why, and he pulled up his shirt and showed a neat

bullet hole in his stomach. I gave him a cigarette and expected never to see him again, but did, three years later, in Italy. A completely empty stomach had saved him.’19

While Kippenberger was intent on rallying the troops who had fallen back, the reinforcements called for through Captain Bassett and swiftly sent by Brigadier Inglis had begun to come on the scene. Already at 7 p.m. 4 Brigade had warned 5 Brigade that the line was being heavily attacked. By half past seven 23 Battalion had been ordered forward from 5 Brigade to take over in the former 20 Battalion area, near the Galatas turn-off. The 21st Battalion then came forward into the former 23 Battalion positions, and 28 Battalion was ordered to stand by ready to help at dusk. About the same time Brigadier Hargest’s HQ staff were posted along the main coast road to collect and reorganise stragglers.

While he was waiting for 23 Battalion to arrive Inglis considered the situation. The line was temporarily gone, in so far as it had been held by 18 Battalion and the Composite Battalion. His reserve was already in use, except for about a company of 20 Battalion and such reinforcing parties as could be scraped together from his own Brigade HQ. He at once set to work having these latter organised, and as a result an officer and 14 men from J Section Signals were hastily sent forward, the Brigade Band, the pioneer platoon of 20 Battalion, and the Kiwi Concert Party. All these were promptly put into an improvised line along the stone walls north of Galatas, at the western edges of which there were already snipers. The 20th Battalion’s A Company with its attached gunners, under Captain Washbourn,20 took up a position on the right of Fountaine’s and O’Callaghan’s two 20 Battalion companies, which had been pulled back some distance from Ruin Ridge to straighten the line.

Soon A Company of 23 Battalion was also on the spot and it took over the gap between the odd detachments – which also included 20–25 men from 5 Field Regiment under Captain Cowie21 – just to the north of Galatas and the 20 Battalion companies. There was once more a continuous front from Galatas to the sea.

Having overrun D Company ridge Ramcke Group, for some unstated reason, decided to halt on a line there.22 the stout defence put up by the two 20 Battalion companies and the odd parties rallied in the area, and the fact that the paratroop units were under strength, probably discouraged them from the

risks of pushing further forward in frontal attack against forces whose strength they had not been able to reconnoitre. And it was already getting late.

No such pause occurred, however, farther to the south, where II Battalion of 100 Mountain Regiment seems to have been attacking on the main part of 18 Battalion front and that of the Petrol Company, while I Battalion attacked from the south-west towards Pink Hill and the Divisional Cavalry front.

Once the attacks on Russell Force front began to gather weight it became difficult, and indeed impossible, for Major Russell to command it as a whole. Telephone lines began to be cut and control could not extend at best much beyond the range of a runner and at worst beyond that of a commander’s own voice. As a result, in the later part of the day’s fighting, the assortment of units and detachments in Russell Force had to function more or less independently.

Foreseeing that Pink Hill was going to be important and how dangerous it would be if the enemy were to get hold of it, Russell had decided in the early afternoon that the Greeks he held in reserve under Captains Forrester and Smith would not be enough to supply the counter-attacks that would probably be necessary and had asked for two platoons to be sent up from 19 Battalion. Accordingly 7 Platoon of A (Wellington) Company, under Lieutenant Scales,23 and 15 Platoon of C (Hawke’s Bay) Company under Lieutenant Carryer,24 were sent up to him. These two platoons Russell held in reserve for some time, and about four o’clock they were heavily dive-bombed and suffered eight casualties. Then, either believing that Pink Hill was already in enemy hands or that an attack on it was about to make dangerous headway, Russell decided to commit his reserve. He therefore ordered 7 Platoon to go through Galatas and establish itself on Pink Hill, while 15 Platoon went forward to the right flank positions of the Divisional Cavalry and worked its way onto Pink Hill from there. The Greek detachments were to co-operate with 7 Platoon.

No. 15 Platoon duly went forward to the right-hand squadron of the Cavalry, but before it could make any further progress Germans were seen moving through the olive trees to the front. The Cavalry and 15 Platoon at once opened fire, and one section of 15 Platoon led by its corporal advanced, throwing grenades. The enemy were driven back and did not again come forward, although a good deal of small-arms fire from the south-west – no doubt supporting fire for II Battalion, 100 Mountain Regiment, from

I Battalion – kept coming in overhead. Not long afterwards Russell ordered the platoon to withdraw.

Meanwhile Lieutenant Scales’ 7 Platoon had divided into two parties, one – under Scales – going round the western slope of Pink Hill and the other – under Sergeant Rench25 – the eastern. This second party ran into difficulties with enemy machine guns, but eventually the platoon collected near the brow of the ridge and settled down to hold the position, in conjunction with Lieutenant Dill’s platoon of gunners whom they had found still in occupation. There was no sign of the Greek detachment whose help Scales had been led to expect.

At this time the Petrol Company with the various supporting detachments was still holding on to the west of Pink Hill. About the middle of the afternoon Carson’s patrol had come forward to help stiffen the line. Hardly had it arrived when there was an attack by thirty Stukas which weakened the right flank badly.26 Into the gap Lieutenant Carson took his patrol and the whole force stayed grimly put against attacks of increasing intensity. Even after 18 Battalion had withdrawn they stayed on, the runner sent to warn them of the retirement having been killed on the way.

The consequence of 18 Battalion’s withdrawal was that the Petrol Company was now coming under heavy fire from the right as well as the front. But Captain Rowe and his men battled stoutly on in defence of their positions until a message came by telephone – this line must have been one of the few that remained uncut – from Major Russell to the effect that 18 Battalion had withdrawn and that he himself was so hard pressed that he would have to withdraw also; but he would try to hold on for a time so that the Petrol Company could withdraw first. About the same time men who had been sent out earlier to try and make contact with 18 Battalion returned with confirmation of Russell’s news. And Carson’s patrol, who had found the wounded runner from 18 Battalion, also brought in the burden of his message. They found the Petrol Company ‘virtually surrounded, with fire seeming to come from all sides.27

Clearly there was no time to be lost if the Petrol Company was not to be completely cut off by the south-east thrust to Galatas. Captain Rowe and CSM James quickly decided to use the left flank on the lower slopes of Pink Hill as a pivot and to swing back their line right of it in extended order. In this way they could keep

a front facing Wheat Hill, in enemy hands since the withdrawal of 18 Battalion, and might cover Galatas against attack from the west. The manoeuvre was carried out with a skill very creditable to troops untrained in infantry tactics. But when Galatas was reached Rowe found there were no troops west of Galatas to which he could hitch his right flank and so screen the village. There seemed nothing for it but to continue withdrawing.

This move had been carried out in co-operation with Captain Nolan’s two platoons of gunners and Carson’s patrol, and the troops involved mostly managed to make their way back safely through Galatas or round its outskirts.

Already before this had happened the Greek detachment under Forrester and Smith, which had been broken up by machine-gun fire before it could come to the support of Scales’ platoon on Pink Hill, had been ordered to form a screen across the western front of Galatas; but reports reached Captain Smith that the Germans were in the northern outskirts of Galatas, and accordingly Major Russell ordered the Greeks to fall back on 19 Battalion.

As Colonel Kippenberger had by now realised that this threat of outflanking was also endangering the whole of Russell Force he ordered Russell to withdraw, and it was no doubt in consequence of this that Russell telephoned Rowe. Soon after this conversation Russell evidently felt that it would be too risky to keep his companies forward any longer, and so the Divisional Cavalry also made their way back towards Karatsos and 19 Battalion.

This left only Dill’s gunner platoon and Scale’s 7 Platoon still forward. Dill himself had gone out to the furthest point of a spur to watch the attack developing and in this exposed position remained with machine-gun fire landing all around him. Sergeant Norman Hill28 who had gone forward with him expostulated. ‘Even though he was my superior officer I could not resist swearing at him and telling him what a damned fool he was. As a matter of fact he turned to me and stated, “If a man believes he will be hit, he will.” (I think he believed this as his conduct throughout the campaign bore this out.) It was then that he actually was hit.

Scale’s platoon and the remainder of the gunners had all this while been defending their position vigorously against the attack, which was by now coming from the south-east as well; for I Battalion, 100 Mountain Regiment, had joined in in earnest and had been attacking since ten minutes past six. In the hard fighting Scales was wounded in the arm, one of Dill’s sergeants was killed and Private A. McKay,29 who a little while before had driven off

a German machine-gun crew from the brow of the hill by hurling grenades, was wounded.

Finally the Divisional Cavalry were observed to have withdrawn and Scales saw that he must get his men away from what was now a hopelessly isolated position. Dill had already been dragged down to the road by Sergeant Hill and then, with the help of the crew of one of the 106 RHA two-pounders, carried to the outskirts of Galatas. Hill went on to get help from the RAP and found it evacuated. He returned to Dill, found he had been wounded a second time, and again went for help. He was followed by Scale’s platoon and Dill’s surviving gunners. As they went through Galatas the Germans came in behind them. It was now impossible for Sergeant Hill to get back. The survivors of the defence of Pink Hill – out of 23 men in 7 Platoon only 12 came off Pink Hill – made their way towards 19 Battalion. There seems little doubt that the remainder of the brigade owed much to the stubborn bravery with which they had defended the key feature entrusted to them. For by now the defence had had a chance to reorganise, it was approaching dark, and the enemy effort for the day was almost spent.

It remains to describe the fate of the guns. Of the two guns in C Troop, the more northerly had been about a mile west of the Galatas turn-off under the command of Lieutenant Gibson. When most of the withdrawing infantry had passed his position Gibson decided he must save his gunners also; to save the gun was impossible without transport. He therefore disabled the gun and went back with his crew until he met Captain Beaumont and the gunners with 20 Battalion. These he joined in their position on the right of the new line.

The other gun, commanded by Lieutenant A. H. Boyce, was half-way between Galatas and the turn-off. About the time of the withdrawal Boyce had gone to discuss the situation with C Troop 2/3 Field Regiment RAA. He returned to find that a passing officer had ordered his men to spike the gun and withdraw. Assuming Boyce himself to have become a casualty, they had obeyed. He therefore took them to the Australian position, where they joined a defence platoon Major Bull30 was organising, and he himself took command of an Australian gun.

The Australian troop had done good work all day bringing down fire on the right flank. Eventually the enemy aircraft located them and gave them special attention but the guns kept on firing. They were still firing over open sights with their four Italian 75s

when the Germans reached the outskirts of Galatas. At point-blank range, with each gun firing on its own commander’s orders, they did a great deal to save the situation.

. ... I got instructions to report to 4 Bde HQ near the Galatos turn-off. There was heavy air activity and going alone across country even was difficult. As I went Jerry started to shell – not bomb – Galatos. The bursts were – believe it or not – a brilliant peach colour. I never saw anything like it before or since. It was crumbling some of the houses about the NW corner, but not collecting any military target. I got my instructions, and then it appeared clear by the row that something was going on in Galatos itself, so I bolted up to the guns to see if they were all right. When I got to C Troop RAA, stragglers were starting to come through them and from the ridge you could see Germans on the outskirts of Galatos. The only thing to do was to protect ourselves so we hauled the guns up to the ridge. It wasn’t very difficult to persuade the stragglers to lie down along the ridge to form a sort of firing line on each side of the guns. It was all very primitive but it seemed the only thing to do. There was a little potting but no one in the position got hit. Our gun fire was gloriously accurate using the open sights and gun control, and very soon all Jerries hastened out of sight.31

F Troop, 28 Battery, though it was unable to bring down fire on the right flank, had also had plenty to do all day. Its telephone line to Galatas exchange was continually being cut and the signalmen under Bombardier Khull32 had a difficult time trying to keep it in repair. But whenever they had communication to the observation post, they fired by its reports and, when they had not, they relied on registered targets. Finally, darkness came and the guns of both troops had to fall silent.

The Counter-attack for Galatas

Back at Galatas Colonel Kippenberger had barely had time to take comfort from the restoration of a line on his right and the news that further help was on the way from 23 Battalion when a message reached him of attack on Major Russell’s front. The position seemed critical. So far as he knew Russell Force had not yet withdrawn. The enemy had entered Galatas, however, in the wake of 18 Battalion and the whole left flank held by Russell Force was therefore in danger. Worse, the enemy might still before nightfall renew his thrust and by debouching from the village deny 18 Battalion a badly needed chance to reorganise. Successful breakthrough in the centre would enable him to drive north for the coast road and cut off the restored right flank.

Then, a little before eight in the evening, two tanks appeared. Major Peck had learnt at 7 p.m. that Galatas had fallen and at

Counter-attack at Galatas, 25 May

once sent Lieutenant Farran to block the eastern exit, while two other tanks under Captain A. J. Crewdson went to block the entrance to Karatsos. Close behind Farran’s tanks came C and D Companies of 23 Battalion.

Here was a chance for the anvil to hit the hammer. A hard blow now would give Russell Force the opportunity to disengage and would check the enemy for at least the hour or so needed till dark. Colonel Kippenberger acted quickly.

Farran stopped and spoke to me and I told him to go into the village and see what was there. He clattered off and we could hear him firing briskly, when two more companies of the Twenty-third arrived, C. and D., under Harvey and Manson, each about eighty strong. They halted on the road near me. The men looked tired, but fit to fight and resolute. It was no use trying to patch the line any more; obviously we must hit or everything would crumble away. I told the two company commanders they would have to retake Galatos with the help of the two tanks. No, there was no time for reconnaissance; they must move straight in up the road, one company either side in single file behind the tanks, and take everything with them. Stragglers and walking wounded were still streaming past. Some stopped to join in as did Carson and the last four of his party. The men fixed bayonets and waited grimly.33

There was a pause while the two companies organised for the attack. Then Farran returned, after having gone well into the town and sprayed each side of the road with machine-gun fire. ‘the place is stiff with Jerries,’ he said.34 Would he go in again with the two companies? Certainly he would; but the corporal and gunner of his second tank had been wounded. Could they be replaced? Kippenberger called for volunteers among the troops standing by.

Volunteers came forward and from among them two were chosen. Private Lewis,35 a machine-gunner attached to 23 Battalion, became commander of the tank. Private E. H. Ferry,36 a driver from 4 Brigade HQ, became gunner – for as a school cadet he had learned how to handle a Vickers. The wounded men were dragged out and Farran gave his new recruits a brief course:

This one-pipper bloke was a man of action, he gave us many words of instruction and a few of encouragement, finishing up in a truly English manner ‘Of course you know you seldom come out of one of these things alive.’ Well, that suited me all right – it seemed a pretty hopeless fight with all these planes knocking about and a couple of my bosom friends had been knocked.37

The extra time got by this delay was not wasted. Kippenberger sent his batman to warn Lieutenant-Colonel Gray of the counterattack and tell him to join in. Captain Bassett, as indefatigable as his opposite number, Captain Dawson of 5 Brigade, went as well.

I ... found that amazingly virile warrior, John Gray, who no sooner grasped Kip’s message than he fixed his own bayonet, and jumping out of the ditch cried ‘Come on 18th boys, into the village.’ And blow me if most of the line didn’t surge out after him.38.

Gray formed up these survivors of his battalion – at this stage a few dozen strong – on the eastern edge of the village. Here they were joined by a further party from Headquarters Company 20 Battalion, including the Bren carrier platoon. These men had been mustered by Major Burrows and had come forward from 4 Brigade with Bassett and Lieutenants Bain39 and Green.40. They now found Gray ‘personally directing operations and undaunted by all the enemy fire power from the ground as well as air going on round him.’41 Gray told them they were to clear the village with the bayonet – ‘not a very bright prospect as the Jerries seemed to have MGs and Mortars everywhere. There was a terrific amount of fire coming from the village.’42

Other stout soldiers joined in. ‘I found the fair Forrester bare-headed, with only a rifle and bayonet, itching to go, and that great lump of footballing muscle William Carson, with a broad grin, licking his lips saying “Thank Christ I’ve got a bloody bayonet.” ‘43 For Driver Pope44 and about six men of Carson’s patrol who had found their way out shortly before from the Petrol Company’s lines, to see an attack preparing was to join it. And all sorts of men who had got cut off from their units and found themselves in the vicinity would not be left behind. The spirit of such men, the flower of those left from the day’s fighting, may be dwelt on, if only to set off the less creditable – and indeed less typical – straggling that had taken place when the line broke. A quotation from Lieutenant Thomas of 23 Battalion will illustrate:

I rejoined my platoon. Their numbers seemed greater. Looking closer in the gloom I made out several unfamiliar faces.

‘We’ve got some reinforcements, Sir,’ said Sgt Templeton. ‘these chaps are from the 18th and 20th and want the chance of a crack at the Hun.’

A tall Lance-Corporal stood up. ‘Is it OK, Sir?’ a little anxiously. ‘the bastards got my brother today.’

While this was happening the two 23 Battalion companies stood in two files on either side of the road, bayonets fixed. They had come forward through men demoralised in the withdrawal – losing their commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Leckie, wounded on the way – but were themselves thirsting ‘to get stuck into the Huns’.

The plan, for lack of time, was simple. C Company, under Captain Mark Harvey, was to attack on the right of the road, D Company under Captain Manson,45 on the left. And for the platoon commanders the orders were no more complex, as Captain Harvey’s to C Company will show:

D Company will be attacking on the left of the road and we have two tanks in support but the whole show is stiff with Huns. It’s going to be a bloody show but we’ve just got to succeed. Sandy, you will be on the right, Rex on the left. Now for Christ’s sake get cracking.46

By now Farran was back with his second tank and its novice crew It was time to be off. Colonel Kippenberger gave his orders. He was not to go farther than the village square. ‘Now get going.’

It was not quite dark. Farran set off in the first tank towards the village, 200 yards away. The second tank followed. Behind came the infantry, marching at first and then at a run. All of C Company went up the road, and one platoon of D Company. The other two – 16 and 18 – swung left and came in from the flank. It was between eight o’clock and a quarter past.47

Almost at once there arose above the jabbering of small-arms fire a shout that swelled and spread into a savage clamour and left a memory that still vibrates in the minds of all who heard it.

... as the tanks disappeared as a cloud of dust into the first buildings of the village the whole line seemed to break spontaneously into the most blood curdling of shouts and battle cries. Heaven knows how many colleges and schools were represented by their ‘hakas’, but the effect was terrific – one felt one’s blood rising swiftly above fear and uncertainty until only an inexplicable exhilaration quite beyond description surpassed all else, and we moved as one man into the outskirts.48

2 Coys 23, 2 tanks, remnants 18 under Gray commenced attack on Galatos at 2010. Hard fighting in progress. No report back.

Have line of 1 Coy 23 and 2 pls 20 from EFI North and 1 Coy 20 abt Galatos main rd junction with gap on left. Don’t know position N. of road. Have 2 Coys 23 (weak) in hand and cannot do more than complete line indicated.

Recapture position requires serious c/attack say at dawn. Tanks not returned.

The infantry charging down the main road soon found themselves under fire from the front and from both sides. Enemy signal lights called desperately for mortar support and the mortar bombs were not long in following. At first the New Zealanders stopped to clear the houses of enemy as they passed them. But they soon saw that by doing so they were losing momentum. So they charged on, ignoring the fire from their flanks, firing steadily to the front, and arrived at the main square, the enemy’s mortar bombs by now bursting harmlessly behind them.

At the square the tanks had already preceded them. The leading tank was knocked out there. The second halted and turned back. An altercation with Lieutenant Thomas who had by now come up followed; for Private Lewis had been slightly wounded, had lost his grip of the speaking tube to the driver, and so lost control of the tank as well. But the tank now turned again and went on in front of the infantry once more. It then got stuck in a gutter and was heavily handicapped by a partly jammed traverse. The street in front seemed quiet, and the fighting sounded as if it were behind. So the tank turned back once more.

Meanwhile the infantry had found Lieutenant Farran lying wounded with his wounded crew in the square. A fierce battle began in the square itself. A German seized a C Company cook by the throat and began to use him as a shield against the bayonets of the others. Private Kennedy, of Sergeant Dutton’s49 13 Platoon, finished off the German with a butt stroke.

But fire was coming from the other side of the square and the enemy was gathering. The New Zealanders decided to charge.

The consternation at the far side was immediately apparent. Screams and shouts showed desperate panic in front of us and I suddenly knew ... that we had caught them ill-prepared and in the act of forming up. Had our charge been delayed even minutes the position could easily have been reversed. By now we were stepping over groaning forms, and those which rose against us fell to our bayonets, and bayonets with their eighteen inches of steel entering throats and chests with the same ... hesitant ease as when we had used them on the straw-packed dummies in Burnham. One of the boys just behind me lurched heavily against me and fell at my feet, clutching his stomach. His restraint burbled in his throat for half a second as he fought against it, but stomach wounds are painful beyond human power of control and his screams soon rose above all the others. The Hun seemed in full flight. From doors, windows and roofs they swarmed wildly, falling over one another to clear our relentless line. There was little aimed fire against us now.50

The square carried, the charge went on. More enemy appeared in the narrowing lane, fired and fell. Then Thomas himself was hit simultaneously by a bullet in the thigh and a grenade. His sergeant had already fallen. The platoon, led by Private Diamond51 – ‘Come on, you blokes, let’s get stuck into the bastards and be done with it.’ – went on. As he lay on the ground Thomas could hear Farran calling behind him: ‘Good show New Zealand, jolly good show, come on New Zealand.’

By now the only other two officers in C Company, Captain Harvey and Lieutenant Rex King, had both been wounded – Harvey with a bullet in the mouth, King with a bomb in the face and legs. D Company which had thrust in from the flank was in hardly better case, with only Lieutenant Connolly52 and Lieutenant Cunningham53 still standing.

With so few officers to control the charge, the men were by now tending to lose direction and the fighting became ever more confused. By now Gray and his men had also reached the square and helped 23 Battalion destroy a machine gun that was holding up the advance. Lieutenant Bain led the platoons of 20 Battalion in a bayonet charge – ‘nothing short of a 25 pounder would have stopped him.’54 He was wounded; and in the same charge Lieutenant Green was killed.

Lieutenant-Colonel Gray, Lieutenant Macdonald55 (the 18 Battalion signals officer), Lieutenant Lambie56 and some members of 5 Platoon patrolled beyond the square and encountered machine-gun fire and grenades at the schoolhouse some distance beyond it. Macdonald was wounded and the patrol returned to the square to try and get help from the tanks, which were unable to give it. The schoolhouse itself was eventually dealt with by Sergeant A. C. Hulme, who went forward alone and with a series of grenades so discomfited the enemy that the counter-attack was able to get on. When at last the fighting died down only one strongpoint at the south-west exit of the village still held out.

The surviving officers now began to reorganise their troops for the enemy counter-attack that might still follow. But, though the enemy had the troops for it, he seems to have been too dazed

for further fighting and preferred to wait for daylight to bring the accustomed support from artillery and aircraft.

Major Thomason had come up to replace Leckie in command of 23 Battalion, and Colonel Kippenberger showed him where the line ran and put him in charge of Galatas. Thomason accordingly left C Company to hold the village, placed A Company on the right flank, D Company between it and C Company, Headquarters 2 Company on the left, and B Company in reserve.

So ended one of the fiercest engagements fought by any New Zealand troops during the whole war. Its success against superior forces had fully justified Kippenberger’s sudden and bold decision. Although Russell Force whom it was largely intended to help had already withdrawn, a breathing space had been gained and the line was secure for a few hours more.

But with this day’s fighting 10 Brigade no longer existed as a formation. The Composite Battalion had never been thought of as more than a static unit, incapable of manoeuvre and unsuited to attack; the stabilised situation in which it could have been used again as a holding force was not to be granted in the days to follow. The Petrol Company and the Divisional Cavalry were for the moment out of the picture, having come in on 19 Battalion. That battalion itself, which had fought so well since the first day under its imperturbable commander, Major Blackburn, properly belonged to 4 Brigade.57 Moreover, by this time all New Zealand units were so reduced in numbers that there was no need for more than two brigades. Colonel Kippenberger, therefore, ‘more tired than ever before in my life, or since’, set off to report to Brigadier Inglis at 4 Brigade HQ.

The Decision to Form a New Line

During the afternoon it had become clear to Brigadier Puttick that the situation was steadily altering for the worse. There had been heavy air attacks on the forward troops, on Canea, and on all the roads. This might have been endured as it had been for six days already; but casualties had been mounting and, although morale was still astonishingly good, the forces in the line were too few for the ground, had inadequate artillery support and none from the air, were patchwork in organisation, and from lack of reliefs were growing exhausted.

Even so, had the day been got through successfully, there would have been a case for hanging on yet another day. But the enemy’s late-afternoon success – which was probably no great surprise to Puttick – made it obvious that, if the Division was to keep an unbroken front, the line would have to be shortened. The only way was to withdraw the forward units to make a line with the right flank of 19 Australian Brigade. If either 4 or 5 Brigade could hold this, the other might be withdrawn for reorganisation and rest.

Puttick’s idea was that 5 Brigade should man the new line. At the same time, however, he realised that the units of the two brigades were now very mixed and that to disentangle them would not be easy. Accordingly, when Brigadier Inglis asked by a telephone message relayed through 5 Brigade at 10 p.m. for Puttick to come forward to 4 Brigade HQ as soon as possible. Brigadier Puttick – unable through other preoccupations to go himself – at once sent Lieutenant-Colonel Gentry, giving him ‘outline instructions for the withdrawal of 4 Bde’ and leaving him ‘to tie up the detailed arrangements.’58

The situation as it appeared at Divisional HQ between Gentry’s departure at 10.15 p.m. and his return is well seen in two messages sent by Puttick about eleven o’clock, one to Force HQ and the other to General Weston. Both were sent while Brigadier Stewart, who had come from Force HQ, was still at Division. Their burden was the same: the Galatas line had been broken,59 Puttick was trying to form a new line north from the Australians, the Australians had already been warned to adjust their line accordingly, and he hoped to form a second line in support along the river immediately east of Divisional HQ. His own HQ was to move about midnight to a position near that of 19 Brigade HQ.

The message to General Weston adds the detail that Brigadier Inglis was establishing the new front line ‘possibly through rd incl South of Hospital.’ But this must have referred only to the immediate emergency and did not imply that 4 Brigade was to man it. For one paragraph says: ‘Elements of 4 Brigade (stragglers in and possibly complete units) may assemble north of right flank of your Marines on the river to reform, but this depends partly on plans arranged at 4 Bde HQ.’ Evidently a good deal was being left to the discretion of Lieutenant-Colonel Gentry and the commanders on the spot; but, short of going forward himself and

leaving his HQ at a difficult time, there was nothing else Puttick could do.

Back at 4 Brigade HQ Inglis had warned Lieutenant-Colonel Dittmer that he would probably have to counter-attack with 28 Battalion, had gone off to inspect the northern half of his sector, and had then come back to send the message requesting Puttick’s presence and to hold a conference of his commanders.

By this time Inglis had had a chance to sum up the situation and he did not find the prospects for counter-attack good.

The front was far too wide for a single bn in a night attack; the terrain was cut across by vineyards and small ravines lying at angles to the line of advance; the Maoris did not know the ground; the rolling features made identification of the objective almost impossibly difficult; even if 28 Bn were to make the objective, it was a certainty that it would leave a lot of unmopped enemy in its rear, for it had not enough men to cover the area.60

On the other hand, to decide against counter-attack would be to take a decision vitally affecting the battle. It was for this reason that Inglis had called for Puttick; for it was just possible that he could produce some reinforcement that might make counter-attack more feasible.

Meanwhile the battalion commanders had assembled in 4 Brigade HQ, ‘a tarpaulin-covered hole in the ground ... with a very poor light.’61 When Colonel Kippenberger arrived he found Brigadier Inglis, Major Burrows, Major Blackburn, and Major Sanders (the Brigade Major) seated round a table. Dittmer arrived soon after, having already had time to consider his probable role. Gentry had not yet arrived.

Brigadier Inglis put the case for the counter-attack in order to draw the views of his commanders. All realised that if the attack were not feasible Crete was lost. And all knew how difficult it was. Kippenberger said it could not be done without two fresh battalions. Dittmer, as the battalion commander affected, could hardly say as much. He said it was difficult. Inglis continued to press: ‘“Can you do it, George?” Dittmer said, “I’ll give it a go!” ‘62

At this point, while the commanders looked in silence at the map, Gentry ‘lowered himself into the hole.’63 the circumstances were altered by his arrival. For, had Puttick been able to come,

The decision would have lain with him. Now Inglis saw it would have to be his own. He asked Gentry for his views about counterattack. The answer was against: the Maoris were the last fresh battalion. If they were used now a line could not be held next day.

This opinion bore out Inglis’ own doubts and he decided that the counter-attack could not take place. Then could Galatas be held? Obviously it could not. It was outflanked, it was an obvious target for concentrated bombing and, apart from the fact that it still contained many civilians, the houses were too flimsily built to offer much protection against the bombing.

If Galatas was sacrificed, then the rest of the line would have to go. In fact there was no alternative to the plan already favoured by Puttick – and presumably now explained by Gentry – for withdrawal to a line running from the Australian right flank to the sea.

There was still the question of which brigade was to man this new line. Gentry passed on Puttick’s view that it would have to be 5 Brigade, and it was clear enough to those present at the conference that this was correct. For of 4 Brigade 18 Battalion was temporarily disorganised and exhausted; 20 Battalion was still split and had had no pause since the Maleme counter-attack in which to knit itself together again; and only 19 Battalion was reasonably strong and fit to fight as a whole next day. Fifth Brigade, on the other hand, in spite of the heavy fighting it had seen, had at least had some sort of rest since the withdrawal from Platanias. True, 23 Battalion had just fought in Galatas and had had losses; but it was still a unit and strong enough to fight again next day. The 21st Battalion was reduced in numbers even from the under-strength state in which it had begun battle on 20 May; but it had had a relatively quiet day. The 22nd Battalion was thought to be hardest hit of all but would be useful as a reserve. And 28 Battalion, for all its exploits so far, was as spirited and reliable as ever.64 Moreover, 23 and 28 Battalions were forward already.

By the time these conclusions had been reached and the conference broke up it was after midnight. Gentry returned to Division where he found Brigadier Puttick and, with him, Brigadier Stewart. They approved the general line taken at the conference, and a confirmatory order was sent out by special despatch rider at 2.35 a.m. After giving a brief account of the loss and recapture of Galatas and stating that renewed attack could be expected next day, the order went on to give the new line and dispositions. The

line was to run from the coast of the peninsula east of the old 7 General Hospital, southwards over the hill about a mile east of Karatsos, and then down the stream that ran along the front of 19 Australian Brigade. That brigade would hold the left sector up to and including the Prison-Canea road. Fifth Brigade would hold the line to the right of this and up to the coast. It would have under its command, as well as its own units, C Squadron of 3 Hussars, the Divisional Cavalry, 7 Field Company, a company from 20 Battalion, and 19 Battalion. The 5th Field Regiment with nine 75s would be in support. The 18th Battalion, the Composite Battalion, and 20 Battalion would reform behind this line under the command of 4 Brigade.65

Either before or after the despatch of these orders but presumably with full knowledge of the plan, Major J. N. Peart, A/Q to Division, called at 4 Brigade HQ and saw Brigadier Inglis. They both then went on to 5 Brigade HQ to discuss detailed arrangements.

Though Brigadier Hargest was disappointed at not securing the rest for his battalions which he had hoped, there was nothing for it but to accept the situation. He borrowed A Company of 20 Battalion to strengthen his own 21 Battalion and asked Inglis to wait and see the new positions established as he himself was not acquainted with the ground. This Inglis agreed to do; but as his brigade staff had been more or less dispersed by the emergency calls made on them during the day, he had to ask Peart to assist his Brigade Major by arranging for dispersed elements of 4 Brigade to be directed into a concentration area as they crossed the bridge west of Canea.

Before the new line was manned the various units affected were to have a busy night moving out of the forward areas and into their new positions; but these movements can best be treated when the time comes to give an account of the situation at first light next morning.

Other Fronts and Creforce

Although the enemy on the Australian front was not very active at this stage, aggressive plans being suspended until Galatas should be taken, Brigadier Vasey was aware of the hard pressure against 4 Brigade and anxious to do anything possible to relieve it. The attack by 2 Greek Regiment the previous day had failed to drive the enemy from the high ground, and in a conference on 25 May at the

Greek HQ it was decided that 2/8 Australian Battalion should try to seize the two hills which were the hub of his position. Such an attempt if successful might do much to relieve the pressure round Galatas. The attack was therefore planned for that evening66 and the plan was that 2/8 Battalion, having taken the two hills, would swing right and advance about a thousand yards to link up with the New Zealand front.

When news reached 19 Brigade, however, about two hours before dusk, that 4 Brigade’s front was still unbreached it was decided to cancel the attack. This was as well. If such an attack were to be made at all the time for it was earlier in the battle. Withdrawal from now on was inevitable, and a forward move would have wasted lives and exhausted energies that were going to be severely taxed before the battle was over.

The 2nd Greek Regiment itself seems to have had little to do on this day, and the arrival of a party from 8 Greek Regiment with the news that it was still fighting, though so short of food and ammunition that it might have to break off action, had a depressing effect; so much so indeed that Major Wooller set off that evening to report the general situation to Creforce and see if any further supplies could be obtained. For he rightly felt that if 2 Greek Regiment threw in its hand the way would be open to the enemy to work round the flank and cut off the New Zealand Division.

It now appears, however, that the report from 8 Greek Regiment, though it may not have exaggerated the difficulties the Greeks were meeting, painted too black a picture when it suggested they might abandon the battle. And, since the resistance they continued to offer had an important influence on the main front, it is necessary to pause here and give an account of it. Unfortunately, owing to the absence of material from Greek sources, such an account has to be based largely on German versions of the fighting; but from these it should be possible to infer a story in its main lines reliable.

It has already been seen that the Engineer Battalion of 3 Parachute Regiment failed in an attempt to take Alikianou on 20 May; and that Colonel Heidrich felt his situation so serious that night that he ordered the battalion to close under cover of darkness so as to establish itself in positions from which it could cover his rear and at the same time act as his reserve.67 But from this day on communications between 8 Greek Regiment and Creforce practically ceased;

while the evidence of Lieutenant K. L. Brown, who had been captured on 21 May and escaped the same day, suggests that the enemy had by this time got into Alikianou and Fournes and that the only part of 8 Greek Regiment still holding out was on the ridge east of the road between Alikianou and Aghya.

It seems likely, however, either that Brown was misled by his Greek informants or that the Germans in Alikianou and Fournes were only scattered parties of parachutists, who soon found it prudent to withdraw on to their main body or were dealt with by Greek soldiers and civilians.

At all events Heidrich found himself with enough to do in these first three days without attempting aggression elsewhere than on the Galatas front, and we may assume that in this respite the Greeks – soldiers and civilians – had time to reorganise themselves for defence. It was not till 23 May that General Ringel had made enough progress on the Maleme front and had enough troops to decide the time had come for a drive through Alikianou which would emerge south of Suda Bay and cut off all the British troops defending Canea and the areas west of it. The operational diaries of Ringel’s group for 23 May therefore show a considerable interest in Alikianou.

A reconnaissance report – probably air – at 1.30 p.m. on that day reports scattered enemy at Alikianou, while a report from 100 Mountain Regiment in the middle of the afternoon says that nothing was known of the situation there. It is evident, however, from a situation map for the evening, that I Battalion of 85 Mountain Regiment was already probing in that direction. But there was not enough time and too great a distance had to be traversed over rough country for any collision to be expected that day.

Till now only I Battalion had been available and had been operating under the command of Colonel Utz, commander of 100 Mountain Regiment. But on the morning of 24 May Colonel Krakau, the commander of 85 Mountain Regiment, had arrived, with III Battalion close behind him. The plan was that the two battalions, and II Battalion as soon as it arrived, should be directed towards Alikianou to carry out the original flanking scheme. And while Krakau was taking over his regiment, Utz was either still in charge of I Battalion or was relaying to General Ringel its reports about Alikianou. Thus at 4.45 p.m. he reports that Alikianou is occupied by enemy, while a report late that night says that enemy troops are dug in there in the strength of about two companies with heavy weapons, with civilians taking part. The strength of the obstacle was such that reconnaissance to Fournes was impossible – a patrol leader had already been killed in Alikianou – but the evidence was that both Fournes and Skines were occupied.

In these circumstances I Battalion, 85 Mountain Regiment, evidently decided that it would be more prudent to defer attack, protective posts facing the village were established, and patrols were sent out to see if a route could be found round the flanks. It seems a fair inference from all this that 8 Greek Regiment and its civilian auxiliaries were still holding the line, and with enough vigour to deter the enemy from a forward move until it could be made in overwhelming strength. Thus it can safely be said that the Greeks by their stoutness in this obscure part of the front had delayed a dangerous thrust.

General Ringel, however, was anxious that his ambitious right hook should be brought off, and his orders for 25 May were that I and III Battalions of 85 Mountain Regiment should take Alikianou and the area east of it, including the high ground. From there they were to push on to Ay Marina, two kilometres south of Suda. To ease their attack there would be heavy air bombing of Alikianou in the early morning.

Had the two battalions of 85 Mountain Regiment struck direct at Alikianou on 25 May there is little reason to doubt that they would have broken through the badly armed Greeks without much difficulty. But whether because Colonel Krakau overrated their strength and was deterred into timidity by his lack of artillery and fighter support, or for whatever other reason, his drive on this occasion was below the standards later associated with good German regimental commanders. By the beginning of the afternoon his own HQ had got no farther than Episkopi, I Battalion was somewhere on his left, and III Battalion was in Koufos. He was still sending out reconnaissance patrols to find the Greek flanks, and he seems to have been disproportionately distressed over the failure of two promised Stuka bombings on Alikianou to eventuate. At the end of the afternoon he had no change to report.

It is no depreciation of Greek courage, however, to say that Krakau’s lack of initiative prevented an ugly threat from developing more rapidly. For the Greeks were badly armed and could hardly have withstood a determined attack. They were well aware of this but remained none the less in position, and by doing so frightened the enemy into time-wasting and futile flanking movements in mountainous country.

The fact that the main front had now begun to move so much closer to Canea was not without its effect on Suda Area. For the growing improbability of invasion from the sea or further air landings was now replaced by a strong likelihood that before long

The units under General Weston’s command would be drawn into the ground fighting.

Accordingly the arrangements of the previous day were modified and embodied in a formal order.68 Suda Brigade, constituted as we have seen,69 was to hold the defensive line of the Mournies River from the Prison–Canea road to the hills south of Mournies. In this way a secondary defence line was created which, extended next day by the reserves of 5 Brigade, would run from the hills in the south to the coast. Should the forward troops have to withdraw there would be a screen through which they could pass.

Northumberland Hussars and 1 Rangers now came as a single command under Major D. R. C. Boileau of the latter unit. They were to be known as Akrotiri Force and were to establish a stop line across the isthmus of Akrotiri, with the further task of dealing with any seaborne or airborne landings on the peninsula.

The 1st Welch under Lieutenant-Colonel A. Duncan was to act as reserve to Creforce and was to exchange places with 1 Rangers, which till then had been holding St. John’s Hill in an anti-parachutist role. And the Suda Area provost, the Greek gendarmerie, and any other Greek forces in the area were to take over the local protection of Canea against parachutists.

Finally, various changes were made in the positions of the AA units round Canea, largely as the result of the bombing of the town which went on relentlessly and continually throughout the day.

It is interesting to notice that so much consideration was still being given to the possibility of sea invasion or airborne landing. Thus General Weston, at a time when the obvious need was for a compact reserve striking force which could be brought to bear quickly, used Northumberland Hussars and 1 Rangers, among the best troops available, to create a stop line which was of little importance and gave them a secondary role which they were most unlikely to have to play. And the result was that Suda Area was in effect without a reserve at all.

At Retimo the garrison still had plenty of spirit and tried yet another early morning attack on the enemy positions at Perivolia. But the results were again disappointing. The supporting tank was ditched and 2/11 Battalion had to postpone the assault for a further day while it was recovered. Advantage was taken of darkness to move a 75-millimetre gun from the eastern sector to

support the next day’s attempt. In the eastern sector itself no attack was launched, though the enemy was made uncomfortable by fire from the guns and a captured enemy mortar.

The enemy at Heraklion still had enough initiative to try a further attack on the town from the west. But this was beaten off by 2 Yorks and Lancs, which had taken over the town’s defence from the Greek forces while these latter, reorganised into two battalions, were given the task of defending Knossos hospital and the road to Knossos. An encouraging development was the arrival of an advance party during the morning from 1 Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. Before midnight the whole battalion had come in and was able to relieve 2 Leicesters, who now went into reserve. The reinforcement was welcome as ammunition was running low.

Although 25 May was no less anxious a day for General Freyberg than any of the days that had preceded it, such news as reached him while daylight lasted did not seem to give any very special grounds for anxiety. Communications, owing to the move of Force HQ and of many of the subordinate headquarters, and the undiminished severity of the bombing, were worse than ever; but so far as the evidence went, until late in the day the troops in the forward sector were holding their own. Thus Freyberg was able to report to Wavell during the morning that in spite of a local withdrawal on the right flank the situation there was satisfactory.70 And a further report covering the situation up till 9 p.m. speaks of a land battle going on, synchronising with a heavy attack from the air, but shows no special signs of alarm.71

A personal message to General Wavell written late that night began to the same effect but was interrupted to give more drastic news. To quote General Freyberg:

On the night of Sunday 25th I sat writing my cable to the C-in-C after having watched a savage air attack on the forward troops by dive bombers, heavy bombers, and twin-engined fighters with machine guns and cannon guns. This is what I had written:

Today has been one of great anxiety to me here. The enemy carried out one small attack last night and this afternoon he attacked with little success. This evening at 1700 hrs bombers, dive bombers and ground straffers came over and bombed our forward troops and then his ground troops launched an attack. It is still in progress and I am awaiting news. If we can give him a really good knock it will have a very far reaching effect.

While I was writing the above the following message came in from Brigadier Puttick:

Heavy attacks about 2000 hrs have obviously broken our line. Enemy is through at Galatos and moving towards Daratsos. Right flank of 18 Bn was pushed back about 1600 yds 1800 hrs and 20 Bn moved forward and 23 and 28 Bns were moved to 4 Bde assistance. Tanks were also moved forward towards 18 Bn area to assist in restoring line. Hargest says Inglis is hopeful of establishing a line.

Am endeavouring to form a new line running north and south about 1200 yds west of Div HQ linking up on south with Wadi held by Australians, who have been warned to swing their right flank back to that line. A second or support line will be established I hope on the line of the river, from the right of the Marines on that river past the bridge at the road junct thence down the river to the sea.

Reports indicate that men (or many of them) badly shaken by severe air attacks and TM fire. Am afraid will lose our guns through lack of transport. Am moving my Div HQ about midnight 25/26 to near 19 Aust HQ for the moment. Am exceedingly doubtful on present reports whether I can hold the enemy tomorrow (26th).

E. Puttick, Brig., Commanding NZ Div.

On receipt of this I struck out the last sentence of my draft telegram (see underlined) and added in its place:

Later: I have heard from Puttick that the line has gone and we are trying to stabilise. I don’t know if they will be able to. I am apprehensive. I will send messages as I can later.

This message I sent off there and then at 2 in the morning.72

Once he had told Wavell of the change for the worse, Freyberg’s next thought was to reassure Brigadier Puttick and encourage him for what was to come. His message went at 4 a.m.:

Dear Puttick,

I have read through your report on the situation. I am not surprised that the line broke. Your battalions were very weak and the areas they were given were too large. On the shorter line you should be able to hold them. In any case there will not be that infiltration that started before. You must hold them on that line and counter-attack if any part of it should go. It is imperative that he should not break through.

I have seen Stewart and I am sending this by G 2 who will tell you my plan.

I hope we shall get through tomorrow without further trouble.

B. Freyberg.73

It must have been also in the early morning that Major Wooller reached Creforce and reported on the state of 2 and 8 Greek Regiments. General Freyberg says he ‘made it clear that the Greeks were about to break.’ And, according to Wooller, Freyberg promised food and ammunition ‘but pointed out that if we could

keep the line intact for 24 hours, the matter would not be so vital. I gathered from this that consideration must have been given to withdrawing the force from Crete.’74

No doubt Wooller was right and General Freyberg had seen the writing on the wall. Brigadier Puttick’s message must have made clear to him what was indeed the case: that with penetration of the Galatas line and the enforced withdrawal to a new one the character of the fighting had radically changed. There was now little or no hope of a counter-offensive which could retake the lost ground. From now on steady withdrawal was the best that could be hoped for. But whether or not this was the case, the plans already being put into action were the only ones practicable this night – there would not have been time to get fresh troops from Suda area forward and into position on strange ground. And so relief of 5 Brigade was not for the time being possible.

Black day as 25 May had turned out to be, it had had for Freyberg and his troops one redeeming feature. Middle East had carried out its promise to provide all possible help in the air. And although that help was very far from being enough to turn the scale in the land fighting, the troops had been greatly cheered by seeing a force of Marylands, Blenheims, and Hurricanes attack Maleme aerodrome at ten o’clock in the morning and two further attacks by Blenheims in the afternoon. As Freyberg reported, this was a ‘great tonic for all personnel.’ Nor was this the limit of the RAF’s help or attempted help. A force of Hurricanes and Blenheims had set off at dawn to attack the airfield but had failed to find it because of smoke and mist. And that night four Wellingtons bombed both Maleme and the beaches.

Besides affording help in the air, General Wavell was also doing his best to land reinforcements. Further commandos – D Battalion and HQ Layforce – had attempted to land off the south coast the night before, but the weather was too bad, their boats were washed away, and they were forced to turn back for Alexandria, arriving there at 7.15 p.m. As they returned a further force sailed for Crete, this time 2 Queen’s and HQ 16 Infantry Brigade, which had had to turn back on 23 May.75 As on that occasion they were aboard the Glenroy.

As well as escorting or carrying these troops, the Navy was still active in all possible ways. The Abdiel, which had brought the advance party of 200 commandos on the night of 24 May, left

early in the morning of the 25th with walking wounded from Suda Bay. Ajax, Dido, Kimberley, and Hotspur had carried out a sweep north of Crete the same night and, after failing to reach Maleme in time to bombard it before daylight, had withdrawn to the south again. The Navy was to repeat the sweep on the night of 25 May, Hotspur and Kimberley having been relieved by Napier, Kelvin and Jackal from Alexandria. And at midday a battle squadron, consisting of Queen Elizabeth, Barham, Formidable, Jervis, Janus, Kandahar, Nubian, Hasty, Hereward, Voyager, and Vendetta, left Alexandria to attack Scarpanto aerodrome which was known to be one of the operational bases in use against Crete. In this attack the twelve Fulmars which the Formidable now had were to bomb the airfield, assisted by some RAF Wellingtons.

To us who now know what the true situation was in Crete and how at this very time General Freyberg was being forced to admit to himself that the problem was now no longer one of holding Crete but of saving his force from capture, there is a certain irony in considering the state of mind in Cairo and in London, where distance and the time lag in communications justified hopes which had no ground in reality.

The irony must have been even more present to Freyberg when he read such a message as General Wavell’s sent on 25 May, Wavell having just returned from Iraq. General Wavell complimented Freyberg on the splendid fight he and his troops were making and went on to say that its results for the whole situation in the Middle East would be profound. The enemy had lost a large percentage of his trained troops and the survivors must be weary and dismayed. Instead of an easy win they were confronted with the prospects of a costly defeat. In aircraft, too, the enemy’s losses had been heavy. And Wavell went on to promise maximum effort by the RAF and a further cable about reinforcements. To Freyberg it must have been already clear that no support the RAF was likely to be able to give and no reinforcements the Army was likely to be able to spare would turn the scale.