Chapter 9: The Seventh Day: 26 May

The Line East of Galatas

AT 9 p.m. on 25 May General Ringel issued his orders for the next day. The attack was to continue. Ramcke’s paratroops in the north, 100 Mountain Regiment in the centre, and 3 Parachute Regiment south of Galatas would advance ‘slowly and methodically’ eastward. The 85th Mountain Regiment would be joined by II Battalion, which had arrived during the day, and would also have under its command I Battalion of 141 Mountain Regiment, borrowed from 6 Mountain Division. Thus reinforced, Colonel Krakau was to renew the attempt to cut through by way of Alikianou.

Considerable importance was now attached to this flanking movement. General Student says that the order for it was the only one he gave Ringel during the operation,1 though nothing could have accorded better with Ringel’s own temperament and the training of his troops. No doubt both commanders thought that the final outcome was no longer uncertain, that the flanking technique might save further heavy losses and might prove a quick means to the relief of Retimo. To ensure good progress 85 Mountain Regiment would bypass Alikianou and seize the high ground east of it, while to intimidate any opposition in Alikianou itself, the village would be dive-bombed during the morning.

These orders were issued before the counter-attack on Galatas; but they had been generally phrased and no local events on the front were likely to disturb them.

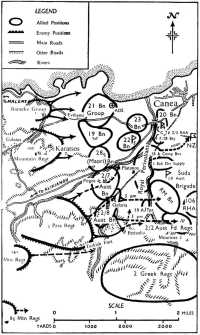

To begin with, at least, the fresh advance the orders enjoined was not difficult; for, after withdrawing during the night, the New Zealand battalions were now back on the new line. The right of this line was held by 21 Battalion Group (21 Battalion with A Company of 20 Battalion, the Divisional Cavalry, and 7 Field

Company under command); its sector ran from the sea to the main coast road, which it included. South of the coast road was 19 Battalion and south again was 28 Battalion, whose positions extended as far as the Prison–Canea road, linking up with those of 2/7 Australian Battalion. In reserve east of 21 Battalion and on either side of the coast road was 23 Battalion; and 22 Battalion, somewhat to the south of 23 Battalion, constituted a second reserve. The 18th Battalion and all of 20 Battalion except A Company had withdrawn to a position east of the transit camp, where they were reforming.2 C Squadron of 3 Hussars had done the rearguard in the night’s withdrawal and was by daylight stationed near the coast road and east of 21 Battalion. The squadron by this time had only five tanks, of which two needed repair. One of the two cannibalised the other and the squadron then had four.

Because the enemy was advancing cautiously the morning began quietly. It was half past ten before 100 Mountain Regiment reported Karatsos clear and about 11 a.m. before Ramcke’s paratroops were at Evthymi. From this latter quarter the first action came, on the front of 21 Battalion.

That battalion was in no very cheerful position. The front was bare of cover and the ground stony. It was already getting light when most of the troops got into position, and there was little time to dig in even had there been tools to do it with. A merciless pounding from the air could be expected to begin almost at once, and the men scraped what holes for themselves they could with bayonets and helmets or built up low sangars with stones.

Headquarters Company and 7 Field Company held the right between the coast road and the sea; A, B, C and D Companies, now organised into one company, and C Squadron of the Divisional Cavalry held the left, covering the road and the area immediately south of it. In reserve to the right flank were A and B Squadrons of the Divisional Cavalry and in reserve to the left was A Company 20 Battalion. To the right front was the former 7 General Hospital, outside the line and tenanted only by those patients for whom evacuation had been impossible.3

The morning began with the usual flight of reconnaissance planes overhead. Then, according to one observer,4 a truck with a Red Cross flag, followed by a motor cycle similarly draped, drove up to the hospital. (Not long afterwards a machine gun opened up on 7 Field Company from the right flank, and a little later a captured

Canea, 26 May

New Zealand medical orderly came through from the hospital under a white flag to say that unless a machine-gun post in line with an ADS behind the 21 Battalion front were removed the ADS would come under fire. The company commander duly shifted the weapon, the orderly returned, and in the subsequent fighting the ADS was respected.)

Shortly after this, about half past nine, the enemy tried to get round the right flank by way of the beach. The Divisional Cavalry from their reserve positions frustrated this, though one enemy machine gun remained in position and was an annoyance throughout the day.

Meanwhile action began to develop along the axis of the road as well. A platoon of Headquarters Company which appears to have been badly briefed withdrew without orders and before fighting had really begun. One man, however, Sergeant Bellamy,5 grasped the importance of defending the road and refused to follow the others. Instead, he mounted his Bren gun in a rough sangar, kept up fire on all enemy movements, and undismayed by his solitude and the fierce fire he received in return, stayed at his post till he was killed.

Dive-bombers had not been long in appearing, their attentions supported by a growing volume of mortar fire from the paratroops. This was difficult for the men to endure in their exposed positions and about 11.30 a.m. Captain Ferguson of 7 Field Company decided that his men on the forward slope of the ridge were suffering unreasonable casualties. He therefore brought them back to the reverse slope. This move isolated the other forward platoon of Headquarters Company, whose left flank had already been opened by the earlier withdrawal. Sergeant W. J. Gorrie, the platoon commander, decided to stay on; but eventually enemy air attack became so troublesome and the threat of a full-scale attack so imminent that Gorrie also moved his men to the reverse slope.6

This minor withdrawal was thought by Lieutenant-Colonel Allen to have been the result of an attack and he at once came forward with reserves to counter-attack. It is not clear whether he found it necessary to do so and the probability is that he did not. At all events the situation was stable again by a quarter past one.

South of 21 Battalion Group, 19 Battalion and 28 Battalion had a not dissimilar morning. The ground in their area, too, was stony, and tools and time were short; though the Maoris had the slight

advantage of having previously done some work on their positions, the machine-gun and mortar fire and the bombing and strafing from the air were very trying. But no major attack developed during the morning, and indeed 28 Battalion had no contact with ground troops at all except for a patrol of 25 enemy which was driven off by A Company.

In fact the enemy planned to put in his main attack in the late afternoon when the sun would be behind him and Stuka support would be available. For some reason the attack did not come in full force, however, and 5 Mountain Division war diary records that at 5.45 p.m. The forward area was ordered to be left clear till nightfall to prevent German bombs falling on German troops. This precaution was probably taken because a battalion of 85 Mountain Regiment had been heavily bombed by mistake this same day.7

Such attack as there was tried the forward battalions sorely enough. Mortar and shell fire was severe all afternoon and at 1.45 p.m. Lieutenant-Colonel Allen reinforced the forward ridge with a section from A Company 20 Battalion and a squadron of Divisional Cavalry. The rest of the 20 Battalion company he held in reserve for counter-attack. Meanwhile a large number of enemy had been observed emerging from Galatas and Allen went over to his left flank. He was held up there by severe air attack till 5 p.m.

While he was away wounded men had been filtering back through the reserve positions of 23 Battalion and, as often in war, brought alarming rumours. According to one, the enemy had broken through 7 Field Company. Major Thomason passed this report to 5 Brigade with the information that he had sent two companies forward on either side of the road and that the remainder were standing by. Brigade HQ endorsed his action and added: ‘Restore the line at all costs.’ To make sure that this was done Brigade also ordered 22 Battalion to move north-east across the main road and help counter the enemy advance.

The consequences illustrate the dangers of moving bodies of troops by daylight in this battle. Both units were caught by low-flying aircraft. The 22nd Battalion had ten casualties; and C Company of 23 Battalion, with thirty casualties, was so severely hit that it had to be replaced by Headquarters 2 Company. The recollections of a private from Headquarters 2 Company give a vivid impression:

As we were making our way up a small gully ‘C’ Coy were coming down causing a lot of congestion. A Hun fighting Messerschmitt crossed

this gully firing his guns. I felt the heat of the bullets pass my face and the leaves were dashed from the tree under which I was crouched. ‘Damn it all,’ I thought, ‘this is no place for mother’s little boy now that bloody squarehead knows we are here.’ So I was out of the gully, crossed the road and made my way up among the olive trees to our rendezvous, and it’s just as well I did for that darn plane came down the gully a few minutes later (not across it as it did the first time) and cleaned up fifteen men.8

Meanwhile Allen had returned to his HQ, where he found Thomason and was able to reassure him that the right flank was holding and the rumour false. His message to 5 Brigade at 5.45 p.m. sums up the situation:

Right flank has caused me considerable anxiety all day. Have had to counter attack once and regained lost ground. Since then have reinforced once; and am standing by to reinforce again. If I have to do so I shall have used all my reserves, but at present line is holding. Left flank position all right but a good deal of Mortar fire coming over. 19th Bn have withdrawn Coy from ridge in front of me.

J. M. Allen, Lt-Col.

Unnecessary though the move of the reserves had turned out to be, such are the chances of war that it might easily have proved providential. For had the enemy attack been full-strength, Allen’s thin screen could hardly have stood it unaided.

South of 21 Battalion also the afternoon had proved more exciting than the morning. The 19th Battalion’s mortars got a good target when the enemy moved out of Galatas, no doubt to put in the late-afternoon attack. Although the mortars broke up the grouping of these troops some did manage to get to close quarters by using the cover of trees; and a shower of grenades forced 5 and 6 Platoons of Headquarters Company to withdraw from their inadequate trenches to a new line about 150 yards back. The territory thus temporarily abandoned was made uncomfortable for the enemy by fire from D Company.

Then at 2.45 p.m. 14 Platoon of C Company counter-attacked and regained part of the lost ground. A quotation from a report by the platoon commander, Lieutenant Cockerill, gives an idea of the conditions:

With Bert Ellis, my senior corporal ... I made a quick recce of the area and it is interesting to note that the German aircraft had so little to do that they chased Ellis and me over a hill firing all the time until we managed to shelter over the brow, and the two aircraft, ME 110s, turned round and chased us up the other side. We managed to hold this position

although the fire was fairly heavy and constant. One interesting part here was that I saw a German reconnaissance unit mounted on a motor cycle attempt to run the blockade down the centre of the road. With Bren guns trained on it from every angle, this unit literally disintegrated.

At 4.45 p.m. Headquarters Company reoccupied the whole position. ‘From then on it was just a case of sitting and taking it as long as possible. We were mortared heavily and had a good few casualties.’9

At half past six 19 Battalion was able to report to 5 Brigade:

Hill SOUTH of EFTHYMI has been re-taken and is now occupied by us. Forward Coys report enemy formations with mortars and field pieces moving EAST along road and in direction our left forward Coy. Am using Reserve Coy which I understand is coming forward; also one PI at present with Div. Cav. Casualties estimated 30.

No serious attack developed, however, and the probability is that the enemy was using the rest of the day to get forward his troops and guns for a big attack on the morrow.

For 28 Battalion the day was fairly quiet, so far as actual fighting went, until about eight o’clock. Here on the extreme left of the battalion front where B Company, the reserve company, had been put in to fill a gap, mortar fire suddenly became very heavy and the forward platoons of B Company – 10 and 12 – had to retire. As soon as the fire slackened, however, Captain Rangi Royal sent in his reserve platoon, together with the sections that had retired, and this counter-attack restored the line.

The tanks of 3 Hussars had had their share in the day’s activities. As well as supporting the move forward of 23 Battalion, one tank had helped 19 Battalion from the north side of the main road until it was located by aircraft and ‘retired along the road hotly pursued by ME 110.’10 At 5.5 p.m., from the rear HQ of 23 Battalion, the OC of the tank troop concerned reported to 5 Brigade:

1705 hrs. Have advanced down road as far as cutting with road block. Shot up Bosche patrol far side of cutting could see nothing else. Light tanks can accomplish very little on this road. I was unable to get off it and aircraft fire was very heavy. At the moment one tank is missing.

A. J. Crewdson.

Twice during the remainder of the day Brigade asked that the tanks should continue to cover the road until further orders, using all available cover.

So long as Galatas held, the enemy had attempted no serious attack on the positions held by 19 Australian Brigade and 2 Greek Regiment. But, now that Galatas no longer offered a threat to the flank of any advance, there was a chance that a strong push by 3 Parachute Regiment might break through and endanger all defending troops to the north of the breakthrough. Accordingly, at half past nine on the morning of 26 May, General Ringel ordered Colonel Heidrich to advance his right wing and try to make contact, to find out just where the southern flank of the defence was, and to go forward in close touch with 100 Mountain Regiment.

A heavy bombing and machine-gunning of the front in the morning heralded the impending attack, and at half past ten, supported by mortar fire, in it came. The point was well chosen. It was at the junction, or rather at the failure to join, between 2/8 Battalion and 2 Greek Regiment. The enemy worked his way through the gap with machine guns and so managed to pin down the two Australian platoons in Pirgos.11 the threat to these two platoons increased and at midday Captain C. J. A. Coombes, commanding B Company on this flank, ordered them to withdraw across the stream behind them and guard the rear of 11 Platoon, stationed between Pirgos and Perivolia. Enemy fire intensified and parties infiltrating behind B Company threatened the whole position, but the Australians held on.

By mid-afternoon the assault seems to have become general along the whole battalion front; according to 11 Air Corps Battle Report it began at 3 p.m., after preparatory fire by heavy weapons, and advanced in a north-easterly direction. In the late afternoon 2/8 Battalion was ordered back to its original positions outside Mournies and at about 5 p.m. it withdrew, B Company being much troubled on the way back by enemy parties in the outskirts of Perivolia. Enemy pressure then began to be felt by 2/7 Battalion, and at 6.30 p.m. Lieutenant-Colonel Walker reported that all his companies were firing. His left rear was now open and the enemy, following up, entered Perivolia and Galaria. A mistaken impression that the Maoris on his right had withdrawn was corrected by reference to 5 Brigade at 7 p.m. Half an hour later Walker reported penetration of two of his companies and that he was taking counter measures.12 Meanwhile 2/8 Battalion fitted its three companies among the force of Marines by Mournies. By nine

o’clock they were in position, strengthening the still-exposed left flank.

Of 2 Greek Regiment no more was heard. This was probably its last day as an organised force, though some speculation about its doings may be founded on German reports. During the day, however, nothing much besides mortar fire seems to have troubled it. Towards evening Major Wooller was warned by Colonel Fiprakis, the commanding officer, that it would be better for him to withdraw with his New Zealand party as the regiment would disband next day.

It remains to give an account of the artillery, now reduced to a total of eight guns: three belonging to F Troop 28 Battery, which had withdrawn the night before; one to C Troop 27 Battery, which had been got out finally with F Troop; and four to C Troop of 2/3 Australian Field Regiment. By dawn these eight guns were ready for action once more in new positions, this time on the east bank of the Mournies River and not far south of the junction between the main coast road and the road from the Prison to Canea.

Owing to persistent attack by low-flying planes, it was impossible for F Troop 28 Battery to set up an OP on the west bank of the stream. There was telephone communication with the Australian troop which did have an OP. But the guns did not have a very satisfactory day: close support to the battalions was too difficult as firing had to be mostly by map reference; ammunition was scarce; and enemy aircraft were very troublesome. Moreover, dysentery was afflicting some of the officers and men, while all alike had begun to feel the effects of nights spent in hard work and no sleep, days when the urgency of battle and the ceaseless worrying of aircraft had denied the sleep lost by night. Food, too, had been very short for a long time now and a man who had had a cup of hot tea since the first day of battle could count himself fortunate.

To make matters worse, as it grew towards evening and the enemy began to work his way in closer, machine-gun fire at long range was added to the trials of the gunners. And so things continued until darkness came.

The troubles beginning to make themselves felt with the gunners were by no means peculiar to them. The infantry were no better off. It is all the more credit therefore to the forward troops that the fight they were putting up made a strong impression on the enemy. Thus CSM Karl Neuhoff of 3 Parachute Regiment says:

At 1400 hours we ran into trouble once again when we were held up by an enemy strongpoint just east of the British hospital. For two hours

we attacked with everything we had, including mortars and machine-guns but could make no progress in the face of a very determined defence. At 1600 hours after having suffered further heavy casualties we desisted in our efforts to dislodge the stubborn defenders and no further progress was made until after dark when the enemy appeared to disengage. ...

And a report in 5 Mountain Division war diary for this day describes the ‘enemy’ in these terms:

The enemy is offering fierce resistance everywhere. He makes very skilful use of the country and of every method of warfare. Mainly snipers, MG nests, and positions partially wired and mined. Shellfire has so far come only from the western outskirts of Canea for the most part. Armed bands are fighting fiercely in the mountains, using great cunning, and are cruelly mutilating dead and wounded. This inhuman method of making war is making our advance infinitely more difficult.13

But, though throughout 26 May the enemy was thus being held, the front could not be expected to stand up indefinitely to the weight of men and weapons now put against it. And, while the forward troops were busy dealing with the enemy to their front, in the rear hard decisions which had to reckon with the larger situation were being taken.

The Decision to Withdraw

Once General Freyberg learnt that the Galatas line was broken and that 2 Greek Regiment was about to break up, he had to abandon his hopes that the enemy might yet be given ‘a really good knock’. His first thought was for the preservation of the new line, and in his letter to Brigadier Puttick, written at 4 a.m., he expressly says: ‘You must hold them on that line and counterattack if any part of it should go. It is imperative that he should not break through.14

Major Saville, who carried this letter, met Brigadier Puttick at 5.40 a.m., as Divisional HQ was settling into its new location near the wireless station. In amplification of the letter Saville said that Puttick and General Weston were to have a joint HQ near Suda, and that Brigadier Inglis was to report to General Freyberg at once.

It is not clear how Freyberg envisaged this joint command as functioning; but he wanted Inglis because he intended to form a brigade from 1 Welch, Northumberland Hussars and 1 Rangers, and to put Inglis in command of it. This intention he explained to General Weston at a conference which took place in the new

Creforce HQ not far from Suda docks, and at which the Naval Officer-in-Command, Captain Morse, and Group Captain Beamish were also present. The plan was that this new brigade was to be withdrawn from Suda Area and was to relieve 5 Brigade that night.15

While he was thus providing for the immediate security of the new line, General Freyberg had now concluded that the loss of Crete was only a matter of time. After the conference he sent off a message to General Wavell which reveals his view of the general situation. The troops had reached the limit of their endurance and the position was hopeless whatever the Commanders-in-Chief might decide. The force on Crete was too ill-equipped and too immobile to stand up against the concentrated bombing. Once the Canea sector was reduced the disposal of Retimo and Heraklion by the same methods would certainly follow. Except for the Welch Battalion and the newly-arrived commando, the troops were no longer capable of offensive action. Suda Bay was likely to be under fire within twenty-four hours. Casualties had been heavy and most of the guns, lacking transport, had been lost. If withdrawal and evacuation were decided upon at once it would be possible to bring off a certain proportion of the troops, though not all. If, however, the Middle East position was such that every hour counted, he would continue to try and hold out.16

At Divisional HQ early that morning Brigadier Puttick had also foreseen that further withdrawal would sooner or later be inevitable, and a letter written by him at 2.45 a.m. to Brigadier Hargest shows that he and Brigadier Stewart had been discussing the situation in these terms:

My Dear Hargest,

I think you and Inglis have done splendidly in a most difficult situation. All I have time to write now is to say that in the unfortunate event of our being forced to withdraw, we must avoid CANEA and move well south of it towards SUDA. Brig. Stewart says he will in that event try to organise a covering force across the head of SUDA Bay through which we would pass, south of the Bay, of course. This information is highly confidential to you but will indicate a line to follow in event of dire necessity.

Would you kindly pass one copy to Inglis.

Good Luck, Yours ever, E. Puttick.

Any doubts Puttick felt about the possibility of a prolonged stand were confirmed in the course of the morning. For in conference with Vasey and Hargest he found that the consensus of opinion was that the New Zealanders, and the Greeks on the left of the Australians, were now so exhausted that the present line could not be held much longer. In the morning Vasey himself seemed confident enough that his own brigade could keep its positions; for Hargest describes a visit by Vasey to 5 Brigade HQ at 11.30 a.m.: ‘Tall good looking a soldierly type. He was to be my comrade for one week and a good one. He said his troops were fresh and had not been engaged and could hang on indefinitely.’17

At this stage Puttick did not know of the command intended for Inglis or the proposed relief of 5 Brigade. Inglis himself had spent the earlier part of the morning handing over to Hargest and had then gone on to Division to find 4 Brigade. At Division, which he reached about noon, he learnt that he was wanted at Force HQ. There were further delays while a truck was found and he then went on. At Force HQ Freyberg told him he was to take over the new brigade. Inglis suggested that to add 1 Welch to 4 Brigade might be the better course, but the suggestion was not accepted, General Freyberg thinking that 18 and 20 Battalions were spent.

It had been arranged that the commanders of the units in the new brigade were to meet Brigadier Inglis at Force HQ, but only Major Boileau of the Rangers had arrived. After a wait of some time it was decided that Inglis would return to Division and that the unit commanders would come to him there. Accordingly Inglis went back to Division, arriving about half past two. At this time it was his understanding that he and his new brigade would be under Puttick’s command.

The return of Brigadier Inglis with the news that 5 Brigade would be relieved that night and the implication that the Division would have to try to hold the same line next day disturbed Brigadier Puttick; for his talks with the brigade commanders had led him to think that the line was too weak in the flanks to be able to hold out so long. Because Main Creforce HQ had been sent off farther east under Brigadier Stewart, and General Freyberg was acting from an Advanced HQ with almost no staff and without wireless or telephone communication to Division,18 Puttick’s only chance of discussing the situation with Freyberg was to go to Advanced

Creforce HQ himself. There was no truck and he decided to go on foot. His main purpose was to put to General Freyberg the dangers of trying to hang on for another day and the arguments for moving the whole force back to Suda that night.

He seems to have had little doubt that he would be able to bring Freyberg round to his point of view. For, presumably in consequence of a warning order from Division, at 2.20 p.m. The Brigade Major of 5 Brigade was calling a conference of commanding officers for three o’clock and Hargest’s instructions to the Brigade Major say: ‘In the warning order tell units we are working with Australians and a British covering force. The night’s operation should be an easy one.’ Clearly, withdrawal was the subject of this conference.

But when Puttick reached Creforce HQ about a quarter past three he found General Freyberg adamant that the line must be held: the enemy must be kept well clear of Suda Bay until the supplies and reinforcements had been disembarked.19 At the same time Freyberg told him that he had decided to drop the idea of a joint HQ and to put General Weston in command of the forward area. Puttick and the New Zealand Division would be under Weston.

Brigadier Puttick now set off for his own HQ, taking with him Lieutenant-Colonel Duncan, the commander of 1 Welch, whom he had found at Creforce. Duncan was acting for the commanders of the Northumberland Hussars and 1 Rangers as well and was anxious to discuss the night’s operation with Brigadier Inglis. The two officers travelled in Duncan’s car; but, even so, because of attentions from enemy aircraft it was 4.30 p.m. before they reached Divisional HQ.

During Puttick’s absence things had altered for the worse. A signal sent by Major Peart, the AA & QMG, to Creforce at 4 p.m. summarises the situation as it had developed in the interval:

Ruck [19 Aust Bde] reports enemy working round his left flank Wuna [5 Bde] reports situation dangerous counter attacking with one bn Comd Duke [NZ Div] had left on foot to visit you before situation deteriorated. Is it possible form rear line with fresh troops in event withdrawal being forced.20

The message represented the situation in a worse light than it actually was, although this could not have been known at Division. Meanwhile a further message from 19 Brigade must have come in;

for at 4.45 p.m. Puttick, having no signals communication with General Weston, signalled to Creforce:

Ruck [19 Bde] reports situation on left very unsatisfactory inform Lift [Suda Bay Sector] urgently.21

As this message indicates, Brigadier Vasey had begun to take a darker view of the situation. Indeed, he was beginning to think in terms of withdrawal; for about five o’clock he visited 5 Brigade HQ and said that the situation on his left flank was critical. Since bullets from machine guns firing from his left rear were already landing near 5 Brigade HQ and Divisional HQ, this was not difficult to believe. He told Brigadier Hargest he believed he would have to withdraw and asked him when he was going to do the same. Hargest replied that he had no orders to do so.22

Telephone between Division and the two brigades was working, and Puttick says that between 4.40 and 5.30 p.m. both brigadiers, and especially Vasey, made strong representations to him in favour of withdrawal.23 It is not difficult to understand and sympathise with him in his predicament. His own reading of the situation quite early in the day had been that withdrawal would be necessary. The two brigadiers who were in the best position to know the strength of the front now supported this view. Freyberg’s plan for the relief of 5 Brigade by the new brigade assumed not only that 5 Brigade would be able to hold on till nightfall but that 19 Brigade would be able to hold its positions next day. If Vasey’s present worry was well founded this might very well prove impossible.24 Moreover, the fact that Ingiis was still waiting for the unit commanders other than Lieutenant-Colonel Duncan to appear, and had still received no explicit orders from General Weston about his night’s role, could not have given Puttick any great confidence that the proposed relief would take place at all.

On the other hand, Weston was now in command of all forward troops and Puttick could hardly use his own discretion, especially as he knew that Freyberg hoped to hold the line for another twenty-four hours by means of a relief.

At length, Puttick decided that he must put the various considerations before Weston and, since he had no direct contact with him by wireless or telephone, to do so by messenger. Accordingly, he began to write the following report, timed 5.30 p.m.:

1. Right and left bdes report total inability to hold their fronts after dark to-day. There has been penetration on right of right bde and on left of left bde.

2. Air attack has been so severe, they report, that the men are completely unable to put up further resistance on a line just in rear, such as the one held by your tps.25

3. there have been no signs of the OC tps to form the new force under Inglis, except the Welch, and the indications are that they would not be available in the fwd area until after midnight at the earliest. To attempt to hold a fwd line with them would in my opinion prejudice the possibility of holding a line further back behind which the fwd tps could reform.

4. I suggest the Welch hold a line as cov.[ering] posn. through KHRISTOS 1553–TSIKALARYA 1552 with the commando extending the line to the South to block the road at AY MARINA.

5. Subsequent movements must be decided later.

6. Presumably rations &c., fwd of the line mentioned in para 4 would be cleared under your or Force arrangements, and all units instructed to take all possible food with them.

7. Force HQ has been asked by W/T to send BGS here at once.26

Puttick had not time to finish this message; for at 5.45 General Weston himself and his GSO 1, Lieutenant-Colonel J. Wills, appeared.27 Puttick read the message to him instead. He underlined its arguments verbally, pointing out that the forward troops might have been forced out of their positions before the relief came up, that the relieving brigade would become needlessly involved in the forward area and would therefore not be available to stabilise the new line near Suda, and that all the time pressure on both forward brigades was growing. He might have added that, since pressure was so strong on the left flank, it would be very difficult to get the right brigade away if the line were held for another twenty-four hours.

At this stage Weston evidently decided to hear Brigadier Vasey’s opinion for himself:

About 1800 hrs Gen. Weston rang me from HQ NZ Div and I informed him of the situation and told him that I considered it was not possible for me to retain my present posn or the line of a wadi about 1000 yards in the rear of it until dark on the 27 May, i.e., for a period of about 30 hrs, and that I considered it necessary for me, in conjunction with the NZ Div to withdraw to a shorter line east of SUDA BAY. Gen Weston stated he was unable

to give a decision on this, but he would represent the matter to Gen Freyberg.28

Weston was now about to set off to consult General Freyberg. Inglis decided that this was his chance to get his own position clarified:

As Weston was about to go, I tackled him about the ‘new brigade’. He was hurried and worried, and very short with me; but I gathered that he intended to use these troops himself and not through me. In any event, neither then nor at any other time did he give them any orders through me, and I did not attempt to make confusion worse confounded by giving them any myself.29

After Weston’s departure – about 6.10 p.m. (although Brigadier Wills says at least 7 p.m.) – Brigadier Puttick found himself in much the same position as before: pressed by his brigadiers to withdraw but without authority to do so. Meanwhile both Brigadier Vasey’s flanks were reported under attack, with the enemy making progress on the left – i.e., southern – flank. Brigadier Hargest, although the fighting on his own front had by now died down, could not but be alarmed for the situation of his brigade should 19 Brigade be overrun or forced back. From 9 p.m. onward both brigadiers were in constant telephone communication with Puttick and asking for orders. In one of these conversations Puttick expressly told Vasey, who said he would be forced to withdraw shortly, that he must not do so without orders, but that if line communication failed and the tactical situation demanded it he must, before moving, inform 5 Brigade HQ on his right and Suda Brigade in his rear.30

The anxiety of Brigadier Puttick at this stage may be imagined. His brigadiers were pressing him for orders to withdraw. His superior officer had felt unable to accept responsibility for the decision. He himself had no authority to order withdrawal, though he agreed with the brigadiers that it was inevitable and considered it tactically expedient. Further delay might make it altogether impossible. Yet his only course seemed to be to wait for further news from General Weston or General Freyberg. To emphasize the urgency of the situation, enemy machine-gun fire from the flank kept passing over his HQ.

Time passed and there was still no news from Weston, with whose HQ direct communication did not exist, or from Creforce. Between eight o’clock and ten Puttick sent off at least one more

message asking for orders. There was no reply. At 10.15 p.m. he tried again:

No reply received to our O 182 and O 183 did comd Lift [Suda Bay sector] return to visit comd Raft [Creforce] late afternoon after visiting Duke [NZ Div] reply urgently.31

At 10.15 p.m. also, a signal which had been sent at ten minutes past ten was received from Creforce. It may have been an answer to one of the earlier signals or may have been merely a routine confirmation of orders already issued verbally. In either case it was hardly helpful:

You are under command Lift who will issue orders.

In his report General Weston says that after his visit to NZ Division he told General Freyberg that Brigadier Puttick and the brigadiers did not think they could hold for another day and were urgent for withdrawal that night. This was at ‘approximately 0930′ hours. By this he presumably must have meant 9.30 – that is, 2130 hours.32 General Freyberg remained firm that there should be no withdrawal. He decided to relieve the New Zealanders with Force Reserve and to go on holding the line with Force Reserve, 19 Brigade, and Suda Brigade.33

In the course of his talk with Weston General Freyberg apparently got the impression that 5 Brigade was ready to stand fast until relieved but that 19 Brigade might withdraw. Freyberg therefore ‘at once sat down and wrote an order that the Australians were to continue to hold their line.’34

The lateness of the meeting between Freyberg and Weston goes some way to explain why Weston did not communicate with Puttick earlier. What remains puzzling, however, is that it was 1.10 a.m. before he sent a despatch rider with General Freyberg’s decision. The only explanation possible – that he assumed Puttick would hold on until he got orders to withdraw – is lame: for he must have known that Puttick was waiting to hear the results of his conference with General Freyberg and that, unless express orders about holding

on reached Division, there was a strong probability that withdrawal would be ordered. The result, whatever the explanation of the delay, was that Puttick was left without an explicit reply to the strong case he had put forward, and was left without information about whether Force Reserve was going to carry through the relief that his own arguments had opposed.

Meanwhile, back at Division Brigadier Puttick, referred by Creforce to General Weston for orders and yet having no communication with him, pressed by a situation which clearly was worsening, and urged by the two brigadiers who were in the best position to judge the danger, decided that there was nothing for it but to withdraw – with or without orders. The new line which he had already suggested to General Weston was that running through Khristos and Tsikalaria to Ay Marina. It was chosen off the map by Puttick as the only line which would be short enough, would give some protection to the left flank, and would still cover Suda Bay against infantry assault. From this point on it will be called 42nd Street, the name by which it became known to the troops and which it owed to the fact that the 42nd Field Company RE had been working there before the invasion.

While Puttick was waiting, Major Peart had gone to 5 Brigade HQ:

Eventually about 9.30 a representative from Div – Major Peart – came and said that Brig Puttick could not get permission for me to go or move, but I was to do so with Vasey.35

It is not now clear what was the precise significance of this visit. The probability is that Peart was asked to go and explain that, although orders had not yet arrived, withdrawal would probably take place and would have to be carried out in conjunction with 19 Brigade. Evidently 5 Brigade went on to make some preliminary arrangements.

At least we went ahead and arranged timings, warned bns and 19 Aust Bde. Then to the best of my knowledge we got orders from Div not to pull out at the arranged time but to await further instructions. No one knew the reason why. We waited 1–2 hours. Then we got the word to go by telephone from Div.36

As Brigadier Puttick says no time was fixed for withdrawal until he gave his final orders to the brigadiers by telephone, the most likely explanation is that Hargest and Vasey had arranged to co-ordinate their withdrawal movements should the enemy break

through and communications break down. The times to which Captain Dawson refers were probably contingent on some such extremity.

The time was fixed when, at 10.30 p.m., Puttick issued his orders to the two brigadiers by telephone. The withdrawal was to take place at half past eleven. And before sending the order Puttick gave Captain Robin Bell,37 the Force Intelligence Officer, who happened to be at Division just then, a message for General Weston:

Duke [NZ Div] urgently awaits your orders. Cannot wait any longer as bde comds represent situation on their front as most urgent. Propose retiring with or without orders by 1130 hrs [11.30 p.m.] 26 May to line North and South through KHRISTOS 1553.

Now that the decision was taken Brigadier Inglis asked Puttick for orders about his own course of action. It seemed clear, after Weston’s visit and his subsequent failure to send further orders, that Inglis’ services were not being called on for Force Reserve and so Puttick sent him back to resume command of 4 Brigade and to put it in a position in reserve to the new line.38

It was now necessary that Divisional HQ should itself set about moving. Major Peart arranged for 1000 rations to be dumped where the troops could pick them up as they withdrew. The remainder of the rations were loaded on trucks and sent to Stilos.

While these arrangements were being made and when the withdrawal had already begun, about 10.45 p.m., Brigadier Vasey’s Brigade Major rang and read over the telephone General Freyberg’s orders that 19 Brigade was to hold on till dark next day. As Vasey says:

Discussion with NZ Div on receipt of this order showed that Div had received no similar order and that they were withdrawing to the SUDA BAY area as previously arranged. That HQ had no knowledge of being relieved in their present position by any other tps. Consequently I decided that to remain in my present positions with the Greeks dispersed on my left flank and the NZ’s withdrawn from my right flank would only result in 7 and 8 Bns being captured. ... This decision was reinforced when after the first message to 7 Bn I received information that the withdrawal of that Bn had already commenced and that they were being followed up closely by the enemy.39

This agrees substantially with Brigadier Puttrick’s account, except that Puttick takes full responsibility for countermanding General Freyberg’s order:

In any case the tactical situation had so altered since the issue of the order by the C-in-C that it could only be observed at the expense of sacrificing 19 (Aust) Inf Bde. The withdrawal of both brigades had already commenced, moreover, and the utmost confusion would have resulted had an attempt been made to cancel the movement.40

The decision to withdraw thus confirmed, arrangements went ahead as before. Shortly before midnight the main body of Divisional HQ moved off for Stilos. Puttick and Lieutenant-Colonel Gentry went in search of General Weston.

The Withdrawal of the Brigades and the Movement of Force Reserve

Although much of the movement that resulted from the order to withdraw took place after midnight, it will be more easily followed if it is treated as part of the story for 26 May. We shall begin with the right flank, 5 Brigade.

The story is tangled and the most that can be attempted is a probable reconstruction of orders and events. Much of the tangle is due to the fact that, in circumstances considered at Brigade HQ to be of great urgency, there were really three different courses of action mooted during the day, that they were discussed for the most part with Brigadier Puttick over the telephone, and that they could not have been easy for Brigadier Hargest to keep clearly separate in his mind.

Thus Puttick’s message of 2.45 a.m. had spoken of the possibility of withdrawal towards Suda Bay and had envisaged in that event a ‘covering force’ to be arranged by Brigadier Stewart. This covering force, as we now know but as was not known to Hargest, would have consisted of the commandos already arrived and of those due to arrive that night.

A second course of action became likely when Brigadier Inglis returned from Force HQ to Division and reported that General Freyberg was organising Force Reserve as a brigade and intended it to relieve 5 Brigade that night, leaving 19 Brigade in position.

But a third possibility arose when the two brigadiers found the situation worsening and began to urge on Puttick withdrawal that night to the Suda Bay area. This was in effect the first plan, with

The difference that while the brigadiers seem to have continued to assume the presence of a covering force, the divisional commander did not, but was rather thinking of a defensive line. This would have become clear to the brigade commanders when they got their final orders at 10.30 p.m.; but by this time warning orders would have gone out to battalion commanders, and they seem to have withdrawn still under the impression that they could look forward to a day out of the line.

In the morning Hargest called a conference for nine o’clock. No record of what passed survives but the probability is that he mentioned the possibility of withdrawal that night. If so, an entry in 22 Battalion war diary for 10.15 that evening – that withdrawal began on the lines of the plan ‘considered that morning’ – would be explained. An earlier entry – for 11 a.m. – in the same diary also suggests that withdrawal was discussed. The entry states that the unit had received orders to be ready to withdraw that evening and company officers had begun to reconnoitre routes. None of the other battalion war diaries has any similar entry for this time.

At 2.20 p.m., however, a fresh message went out to the battalions on Hargest’s instructions, calling a conference for three o’clock. The message to 19 Battalion is probably typical:

19 Bn

Conference of COs at Bde HQ at 1500 hrs. Note: We are working with the Australians and a British Covering Force – the night’s operation should be an easy one. R. B. Dawson, Capt.41

It is possible that when this message was sent out Brigadier Inglis had already returned to Division, and the news he brought with him of General Freyberg’s intentions had been passed by telephone to Brigadier Hargest. Whether this is the case or not, it seems likely that Puttick at this time was reasonably confident he could convince Creforce of the necessity for withdrawal to the Suda area, that he had told Hargest, and that Hargest was now calling a conference to find out what his commanders thought of the forward situation and whether they could hold on till dark and to explain the probable withdrawal.42 No record exists of what took place at the conference; but 21 Battalion war diary records that the Intelligence Officer left to reconnoitre the route back to Suda at 3 p.m. and, if we allow a certain approximateness about the time, this would seem to have been a consequence of the conference.

The general feeling in 5 Brigade HQ that withdrawal was likely must have increased as a result of Brigadier Vasey’s visit at 5 p.m. For the Australian commander’s earlier optimism had changed. He was now certain that he would be forced to withdraw – not so much because of the fighting on his actual front, one may infer, as because of the threat to his left flank. Hargest replied that he himself was still without orders; but his expectation of orders must have remained. For 5 Brigade war diary records that at 6.50 p.m. 19 Battalion was told that withdrawal was probable. The battalion was told to hold on till further instructions. The 21st Battalion was also told to hold on.43

The main events at Brigade HQ for the remainder of the evening are clear enough in spite of some minor confusions about time, probably due to the fact that war diaries were for the most part compiled a good while after the events with which they deal. At 9.30 p.m., if we accept Hargest’s time, but perhaps an hour earlier, Major Peart called at Brigade HQ and apparently explained that withdrawal was very likely but that Division was still without firm orders. No doubt he discussed various administrative arrangements. Captain Dawson then drew up a warning order which gave the general setting of the coming operation:

A line is being formed two miles West of SOUDA at approx the junct of two converging roads. Beyond this line all tps must go. Units will keep close together, liaise where possible to guard against sniper attack. 5 Bde units in general will hide up in area along road between SOUDA and STYLOS turn-off. Hide up areas for units will be allotted by ‘G’ staff on side of road after passing through SOUDA. Bde HQ will close present location 2300 hrs and travel at head of column. Will then set up adjacent to STYLOS turn-off. A dump of rations boxes already opened is situated near the main bridge on main CANEA road also some still at DID. Help yourself. It is regretted that NO further tpt is available for evacuation of wounded. It is desirable that MOs should travel with tps. There is possibility of a dump of amn being on roadside near Main Ordnance dump. Take supplies as you pass.

R. B. Dawson TOO 221544

The despatch of this order would mean that all units could get on with essential preparations so that nothing would delay them when the actual order to move was sent. The order itself is interesting because it clearly indicates that at 5 Brigade HQ it was assumed

There was no question of the withdrawal ending in the occupation of another line. Puttick’s idea by this time was that the Division should itself man the 42nd Street line; but this does not seem as yet to have been understood at 5 Brigade HQ.

This misunderstanding, so far as 5 Brigade HQ was concerned, must have been cleared up when Puttick issued his orders by telephone at 10.30 p.m. The withdrawal was to take place at 11.30 and the destination was the line at 42nd Street.45

It was inevitable, however, that there should be some confusion among the battalion commanders between a warning order which envisaged hiding up along the road between Suda and Stilos with other troops holding a covering line, and an order which called for the line itself to be held. And this will account for some misunderstanding in the sequel.

Brigade HQ probably moved off at 11 p.m., the time given in the warning order.46 the first battalion to move was 22 Battalion, which followed Brigade HQ, leaving one of its companies under Major Leggat to guard the bridge at the junction of the main road and the Prison–Canea road.47 the 23rd Battalion followed shortly afterwards, having been told off to guard the main bridge while the troops passed through. Presumably, as soon as it arrived Leggat’s company was able to leave.48

For the forward battalions disengagement was a trickier matter. The 28th Battalion started to thin out at half past ten, immediately after getting the warning order. By 11.30 p.m., when it would have had the final order, all companies had checked in at a central assembly point. The battalion had been instructed to bypass Canea and keep off the roads leading west and south-west from it. Lieutenant-Colonel Dittmer therefore took his unit across country and reached 42nd Street without incident.

The 19th Battalion also left at half past eleven and made for a point approximately two miles west of Suda. The 21st Battalion Group was the last to leave. With a heterogeneous group Lieutenant-Colonel Allen, a meticulous commander, was leaving nothing to chance and had worked out a careful schedule which took a longer time to operate. The battalion seems to have used the main road at least part of the way, for the Divisional Cavalry passed through 23 Battalion, no doubt at the bridge, at 1 a.m.49

C Squadron, 3 Hussars, covered the withdrawal and, missing the route, found themselves in Canea. There they were put on the right road and came safely on to Suda, arriving at 5.15 a.m. The 23rd Battalion had probably preceded them from the bridge, once all the infantry were through; on reaching Suda it got orders to go to 42nd Street.

With 3 Hussars had gone Captain Dutton,50 Adjutant of 21 Battalion, who had found a truck. He alone of the brigade records meeting Force Reserve: ‘On my way back thro’ Canea I met a Coy Welch Bn going fwd – uncertain about the situation but going fwd.’

A quotation from Brigadier Hargest may suggest something of the atmosphere of the withdrawal.

All arrangements had been made and at about 10.30 we moved each Bn on its route with the Australians on our flanks to the south. The going was terribly hard, the roads had been torn up, vehicles burned across them, huge holes everywhere – walking was a nightmare. Our guide lost us with result that we went through Canea itself, transformed from a pleasant little town to a smouldering dust heap with fires burning but otherwise dead.51

Brigadier Vasey had received authority from Brigadier Puttick to issue a warning order for withdrawal to Suda Bay and he did so about 9 p.m. Then came the final order by telephone.52 Vasey then warned not only the battalions but 2 Greek Regiment on his flank and Suda Brigade in his rear.

Then, a quarter of an hour later, came the order from General Freyberg already mentioned, the discussion with Brigadier Puttick, and the decision to carry on with the withdrawal. Clearly, no other course was by this time possible.

Accordingly, the battalions carried on with the plan already arranged in consultation with 5 Brigade and reached the Suda area about 3 a.m. Here they settled down for the time being to rest.

Fourth Brigade had gone into reserve when 5 Brigade took over the front on the night of 25–26 May. It now consisted of 18 Battalion, 20 Battalion (less the company forward with 21 Battalion Group), and the remains of the Composite Battalion. All three were in a battered state.

Moreover, a double confusion arose over the whereabouts of the units of the brigade and over the question of command. The night before Brigadier Inglis had agreed to stay forward and assist Hargest with the take-over of the front line. To prevent the troops of 4 Brigade from getting too widely dispersed while he was thus preoccupied, he asked Major Peart to sort out the men of the three battalions as they crossed the bridge west of Canea and concentrate them in an area where he would be able to find them next morning. When he came back to Division next morning to look for 4 Brigade, he got orders at once to report to Force HQ and so was not able to locate his units. It was afternoon before he could get a message to his Brigade Major, warning him that he and the 4 Brigade staff might have to take over Force Reserve and ordering him to arrange for Colonel Kippenberger to take command of 4 Brigade.

When Kippenberger received this news he was with 20 Battalion in a bivouac area in the rear of 5 Brigade. He at once chose a staff and set about finding 18 Battalion and the Composite Battalion.

The 18th Battalion, presumably on orders from Division, had at first assembled in the area behind 5 Brigade. It was soon found that this was overcrowded and the battalion was ordered to move to the old transit camp area. But this again was unsatisfactory, for the new area was just behind the front line of 19 Brigade. Accordingly, Division ordered the battalion to yet a third area south-east of the wireless station.

The Composite Battalion, in spite of having been employed piecemeal over so many parts of the front on 25 May, and in spite of lacking the trained unity of an infantry battalion, was surprisingly successful in reforming during the morning at the transit camp. Small parties attached to other battalions or independent kept coming in most of the night and early morning.

Somewhere about midday Lieutenant-Colonel Gray and Major Lewis had reported to Colonel Kippenberger and pointed out the location of their two units. He ordered them to send him liaison officers and to stay where they were.53

Gray took the order from Division to move to the wireless station area as countermanding this. He may have assumed that Division would inform Colonel Kippenberger; if he did send further messages to Kippenberger, no record of them has survived. The upshot in either case was that 18 Battalion set off for the new area and the Composite Battalion, on Lieutenant-Colonel Gray’s orders, followed. This had unfortunate results. For Kippenberger was now completely out of touch, and there was no chance of 4 Brigade

operating as a single organisation until much later when contact between all three units and their HQ could be restored.

Moreover, the new move had to take place in broad daylight at a time when the enemy’s aircraft were more active than ever. One enemy air attack killed the commander of A Company 18 Battalion, Captain Lyon,54 and caused about a dozen casualties among his men. These air attacks broke up the unity of the march and in consequence B Company and part of D Company overshot the new assembly area and continued westward towards Kalivia.

Still later 18 Battalion was ordered to continue to withdraw to the east of Suda Bay. Thus most of the day was spent in a cheerless, harassed and dispirited trudge, brightened only by a glimpse of General Freyberg on the back of a motor cycle:

... Andy Provan driving the cycle flat out and Tiny on the back holding tight with one hand and the other holding his hat on his head.55

He stopped and gave the men an encouraging word – ‘told us to be careful to keep our rifles and keep together and things. ... I know the mere sight of him pulled me together a hang of a lot.’56

The Composite Battalion, having followed 18 Battalion, was similarly plagued by enemy aircraft, and in the resulting confusion tended to break up into small groups under individual officers and NCOs, most of whom were to do good work in the hard days that followed ensuring that the men for whom they were responsible held together.

Colonel Kippenberger continued the vain search for his two missing units by runners and expeditions on his own account. The 20th Battalion itself spent the day resting and preparing for whatever might next be expected of it. By early afternoon it looked battleworthy once more and had been reinforced by the arrival of two of its members who had just reached Canea that day from Greece by rowing boat.

The eight guns of F Troop 28 Battery and C Troop 2/3 Regiment RAA, after an unpleasant day of attention from enemy aircraft, were ordered to withdraw about the same time as the brigades. They were to go back through Canea and Suda to a crossroads where they would find a staff officer with further instructions. The surviving gun of C Troop 27 Battery could not be moved and had to be abandoned; the other seven duly got away. But when the staff

officer was found at the crossroads the orders he gave were for the two troops to make south towards the coast. This they did and towards dawn lay up at Stilos.

This day of general withdrawal is perhaps a favourable point to take up the story of the medical services, whose difficulties increased with every day of the battle and had been made particularly acute by the loss of most of the RMOs of 5 Brigade.

The 5th Field Ambulance had been evacuated from Modhion in the early hours of 23 May and had proceeded thence to the former site of 6 Field Ambulance. In the same move its stretcher cases were taken on to the improvised hospital being run by 189 Field Ambulance in Khalepa, a suburb of Canea. The 5th Field Ambulance itself made a further move the same day to the original site of 7 General Hospital. On 24 May about 200 further wounded who had come in during the interval were cleared to 7 General Hospital, 189 Field Ambulance, 1 Tented Hospital RN at Mournies,57 and 6 Field Ambulance.

Towards evening of 25 May casualties from the heavy fighting at Galatas began to pour back, most of them going to 6 Field Ambulance. For by this time machine-gun and mortar fire were striking in the 5 Field Ambulance area, and at 7 p.m. The ADMS of Division (Lt-Col Bull) arrived and ordered a withdrawal to Nerokourou. This order applied also to 7 General Hospital.

The staff and more lightly wounded were to walk. All the remaining patients of 5 Field Ambulance were to be taken back during the night by the four trucks available, which would make three trips. Delays made only two trips possible before daylight. This meant that there were still about twenty stretcher cases left, together with Major S. G. de Clive Lowe,58 Lieutenant R. F. Moody, Padre Hiddlestone,59 and 14 orderlies. Three truck drivers volunteered early on 26 May to try and get them out. Only one driver got through and an enemy motor-cycle patrol arrived about the same time. The driver, Jenkins,60 escaped by climbing down a cliff. Patients and staff were captured.

The 6th Field Ambulance had also got orders to withdraw, though after 5 Field Ambulance. It had already admitted a good many

wounded from the day’s fighting when Major Fisher,61 the commander, was told to evacuate his 250 walking wounded to 1 Tented Hospital RN. The 100–150 stretcher cases would have to be left behind. Early in the morning of 26 May, therefore, the Ambulance split up: the stretcher cases remained behind under the care of Lieutenant Ballantyne, Padre Hopkins,62 and 20 orderlies and were later captured; the walking wounded went to the Naval Hospital and most of them were evacuated in the destroyers that brought in commando reinforcements on the night of 26 May; while the staff went on to Nerokourou and new tasks there.

No. 7 General Hospital, unable to evacuate its 300 stretcher cases, had to leave them in the caves under the care of a small medical staff. The walking wounded and the rest of the staff went off to Nerokourou on foot.

At Nerokourou an MDS was established and worked through the day of 26 May, with both field ambulances and the surgical team from 7 General Hospital all assisting. Then DDMS Creforce (Col Kenrick) ordered 2/1 Australian Field Ambulance to establish a temporary hospital at Kalivia, and as the medical units at Nerokourou were to move back as part of the general withdrawal, they were ordered to send their patients to Kalivia. The seriously wounded were sent there in trucks while the walking wounded went on foot. Eventually some 530 patients collected there, and when next night it was obvious that further withdrawal was inevitable, some of these were taken south in trucks while some set out on foot. About 300 had to be left behind, many of them New Zealanders, in the charge of an Australian medical officer and some orderlies.

When Lieutenant-Colonel Hely, who commanded Suda Brigade, learnt that 5 and 19 Brigades were to withdraw, he realised that this left him no alternative but to withdraw also from the brigade positions along the Mournies River. For, like the Australians, he had no contact with the Greeks on his left, and if he remained he would be surrounded next morning. Towards midnight, therefore, he gave his orders for withdrawal. After this movement had begun, an order from General Freyberg on the same lines as that sent to Brigadier Vasey reached him. But compliance was now out of the question: his troops were already on the move and, in any case, to

stay would have been suicidal once 19 Brigade had gone. The withdrawal proceeded.

General Weston’s report states that he learnt of the relief role intended for Force Reserve at 9 a.m. when he saw General Freyberg.63 At Creforce it was evidently understood that Brigadier Inglis would command this relief, and as we have seen he spent the afternoon waiting for the unit commanders to appear at the rendezvous, Divisional HQ. According to Brigadier Wills, line communication to 1 Rangers and Northumberland Hussars from Suda Area HQ was established for only a short time that morning, then cut. Runners had difficulty in locating them and both units were busy with infiltrating enemy. Thus only Lieutenant-Colonel Duncan got the order to go to NZ Division.

Duncan returned to his unit about dusk. The battalion had been concentrated, ready for a move, about half past three by his orders. He now told his officers that there were two possible roles in store: either withdrawal to a defensive position at 42nd Street; or an advance to defensive positions west of the Canea crossroads bridge. Major J. T. Gibson of 1 Welch, who was present and who supplies this information, says that Duncan told him that ‘it was being strongly urged that we should carry out the first task.’ From this it seems a reasonable inference that Duncan had learnt at Division of Puttick’s belief that nothing short of complete withdrawal to 42nd Street was practicable. He may well have known also that General Weston had set off to Creforce to get a decision.

Gibson also says that 1 Rangers and Northumberland Hussars were placed under command and that the two commanding officers reported to 1 Welch HQ and remained there waiting for orders.64 these did in the end come, although there is some doubt about the time. Weston says that Force Reserve ‘had already been warned by me to be in readiness to move by 2030 hrs, but owing to blockage of roads, and the difficulty of moving during daylight, some delay occurred in getting the orders through to the battalions concerned who did not move until late that night.’65 the Rangers’ war diary records that orders to move and take over from the New Zealanders

were received at 8.30 p.m. from Suda Bay Area, and this is probably a confusion with Weston’s warning order.66

The actual order must have been much later, as indeed is suggested by Weston’s account already quoted. Captain J. N. Hogg of the Rangers is reported by Captain A. R. W. Low as having said orders arrived at 10 p.m. Major Gibson says ‘it was certainly not any earlier than 2200 hrs and probably considerably later that we received a message brought in by our Motor Contact Officer ordering us to carry out the 2nd task, i.e., to occupy the positions WEST of CANEA BRIDGE.’ This is supported by a witness from Northumberland Hussars who says ‘the CO got his orders at 11.30 and we moved out at 0015. We thought we should have got orders earlier.’67

It looks therefore as if Weston did indeed send a warning order at 8.30 p.m. but did not send off his final orders until after he had seen General Freyberg and returned to his HQ in 42nd Street. It would be later still by the time these orders got to the battalions. The result was that Force Reserve was not in position when 5 Brigade withdrew and was still coming forward when Captain Dutton passed through Canea. This is borne out by Gibson’s statement that 1 Welch moved at 12.30 a.m. and got into position at 2.30 a.m.; as also by the Rangers’ war diary which says the battalion did not get settled in until 4.30 a.m.

Meanwhile the message which Brigadier Puttick had sent by Captain Bell reached General Weston very late, if it reached him personally at all. For Bell, leaving Division before half past ten, went first to Weston’s Canea HQ only to find that this had now moved to 42nd Street. Bell showed the message to Lieutenant Kempthorne,68 who was GSO 3 (Intelligence) for Suda Area, in case anything should happen to himself, and then went on to look for General Weston in 42nd Street. After great trouble in getting there he found the new HQ. ‘I can remember having difficulty in getting access to General Weston personally that night. I think Weston was asleep when I arrived but my message was certainly delivered, if not to General Weston himself then to his GSO 1.’69 Bell then went on to Suda Point and reported the situation to General Freyberg.

By now Puttick and Lieutenant-Colonel Gentry were also on their way to see General Weston. En route, about 1.45 a.m., they met a

despatch rider with a message from Lieutenant-Colonel Wills. The message was timed 1.10 a.m. and read:

Brig. Puttick,

GOC in C has ordered that 4 [ sic] NZ Div70 must hold fast positions tonight 26/27 May until relieved by 1 Welch, NH and 1 Rangers. These latter units received orders to move about 2000 hrs and they should move about Midnight.

It is not easy to see why Weston should have waited so long before sending this message. The move of his headquarters might help to explain, but can scarcely justify, delay in a case of such urgency. He knew that Puttick and his brigadiers thought withdrawal inevitable; and he knew that Puttick must have been anxiously waiting for the decision that he had gone to General Freyberg to get. Nor do his own words to Puttick help to clarify the situation. For, about 2.15 a.m., when Puttick found him asleep in his new HQ and asked why orders had not been sent, ‘Gen Weston replied that it was no use sending orders as Div Comd had made it very clear that NZ Div was retiring whatever happened. Div Comd replied that the retirement could not have been avoided but that orders were necessary so that he would know where to retire to and how best to co-operate with other tps.’71

It is difficult to believe that Weston can have meant what he said to have been taken literally; for if he had really believed that the retirement would take place whatever happened, his action in sending Force Reserve forward would be quite incomprehensible. To find an explanation of his actions we must assume that his words on this occasion were prompted by exhaustion.

Even so, however, we are left with two puzzles. For it remains inexplicable that Weston did not at once signal to Puttick when he learnt from General Freyberg that there should be no withdrawal; and that he left it till 1.10 a.m. before he sent not only the necessary orders but the information that Force Reserve was to move about midnight. The death of General Weston makes it unlikely that a satisfactory explanation can now be found.

The conversation between Weston and Puttick was necessarily brief.72 Puttick went on to inform him that 5 Brigade and 19 Brigade had been ordered to form a defensive line along 42nd Street. Weston replied that he already had troops on or near this line and would not require the two brigades. Puttick said that an attack in force would probably develop shortly after dawn and that the help of the brigades would be found very necessary. On this Weston agreed that they should man the line as ordered and said that he

himself would order their further retirement when the situation made it desirable. Puttick offered him any assistance he needed and the services of his own staff, but the offer was declined.73

Meanwhile Lieutenant-Colonel Hely had also arrived and General Weston ordered him and Brigadier Puttick to report to General Freyberg. On his way to do so, at 3 a.m., Puttick met Brigadiers Hargest and Vasey. He hurriedly discussed the situation with them – it was urgent that no time should be lost in seeing General Freyberg – and told them to choose their brigade positions in co-operation with each other. He then left for Creforce, arriving at 4 a.m.

General Weston had realised that Force Reserve was now in an ugly situation and would have to be recalled. ‘Some difficulty was found in getting DR’s to take this message but two were despatched about 0130 hours. These DR’s have since been interviewed and the fact that the message was delivered to the Welch HQ has been established. The DR’s arrived back at Suda Sector HQ at 0345 hours.’74

If Weston is right in saying the time of despatch was 1.30 a.m., then the message must have been sent before Puttick’s arrival at a quarter past two. If so, it was presumably sent on the receipt of the message carried by Captain Bell and, since the order of 1.10 a.m. for Brigadier Puttick could hardly have been sent if he had been known to be already withdrawing, the not unlikely inference would follow that Bell arrived between 1.10 and 1.30 a.m.

The alternative explanation is that Weston is wrong in his recollection of the time and that the message was sent about 2.30 a.m. If so, Weston must also be wrong about the time of the return of the DRs. But, whatever time it was sent and in spite of the subsequent testimony of the despatch riders, it can hardly be doubted that the message failed to reach Lieutenant-Colonel Duncan; and indeed it is strange that a message of this importance was not given to a staff officer who would realise how vital it was that it should reach the proper quarter.

If Duncan had in fact received the order it is inconceivable that he would have disobeyed it. General Weston suggests that he may have received it and decided that there was not time before daylight to carry it out. But, apart from the fact that Weston says the despatch riders were back before 3.45 a.m., it seems most unlikely that Duncan would not have taken the risk of having his force

caught by enemy aircraft on the roads at dawn rather than accept the certainty of being encircled. Major Gibson specifically says that no order to withdraw was received.

At all events and whatever the explanation, this was the unluckiest confusion of all the confusions on that trying and unhappy day. Its consequences for Force Reserve will appear in the sequel.

Other Fronts and Creforce

It will be remembered that General Student and General Ringel attached great importance to the outflanking movement which was to pass through Alikianou and go on towards Ay Marina. The enemy’s object was partly to cut off the troops in the Canea sector and partly to relieve his own hard-pressed force at Retimo.

Attempts to get this movement going had been hitherto thwarted by the presence of Greek opposition across the proposed line of advance. But after the fall of Galatas the Greeks probably moved back into the hills and the enemy himself began to attack with more determination.

As a result Alikianou was taken in the course of the morning. III Battalion of 85 Mountain Regiment pushed on east of it as far as the hills south-west of Varipetron. It should have been relieved there by I Battalion, which was then to push on to Malaxa with II Battalion following.

Unluckily for this scheme and luckily for the defence, I and III Battalions were severely attacked by their own bombers during the early afternoon and this had an adverse effect on progress and morale. Then I Battalion encountered ‘stubborn enemy resistance’. This and the hard going prevented the regiment from getting more than a few kilometres beyond Varipetron. The breakthrough to Ay Marina and Malaxa had again to be postponed.

Had this thrust been begun earlier and with more energy, and had not the remnants of the Greek forces and the Cretan civilians put up the resistance they did, grave consequences might have followed for General Freyberg’s main body.

At the same time the enemy was building up another threat on the former front of 6 and 2 Greek Regiments. In the morning of 26 May Colonel Jais, commanding 141 Mountain Regiment, was ordered to begin advancing south of Colonel Heidrich’s 3 Parachute Regiment. To do so he had I Battalion complete and elements of his other two battalions. His object was to cut the main coast road at Suda Bay. He began to move in the middle of the afternoon and by evening had reached Pirgos. No opposition

was met, and it may be inferred that any Greek forces still in the area were making for the high country farther to the south.

At Retimo the Australians, unaware of the deteriorating situation on the main front, made yet another attempt on 26 May to reduce the German strongpoint in Perivolia. The 2/11 Battalion set off at dawn, accompanied by a supporting tank. But their usual ill luck dogged them and the tank’s machine gun broke down almost at once. The battalion had to withdraw, postponing its attack for another twenty-four hours.

By 11 a.m. The tank’s machine gun was repaired. It was too late to renew the Perivolia attack, and so instead the tank was used in support of an attack on the factory in the eastern sector. In this engagement B Company of 2/1 Battalion took 80 prisoners, 40 of them wounded. A further enemy party to the east, about 80 strong, was attacked and contained by Cretan gendarmerie. To make the morrow’s plans more certain the troops dug out the second tank and trained a crew that night.

During the afternoon also the Quartermaster of 2/1 Battalion succeeded in making his way back from Suda. Unfortunately, as he had left during the previous afternoon, he knew nothing of the latest developments in the situation there. Retimo force therefore continued to expect reinforcement and guessed nothing of the evacuation which was by now being planned. In this ignorance of the true situation they felt no reason to be dispirited and were embarrassed only by a shortage of supplies, which their possession of 500 prisoners seriously aggravated.

The enemy at Heraklion was still intent on concentrating his forces in the eastern sector if possible and continued his attempt to do so into daylight of 26 May. The route followed was to the south of the defence, and one concentration in the course of the morning forced a minor Australian withdrawal. A more serious development took place on the front of the newly arrived Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. Early in the morning the enemy surrounded the forward elements of this battalion, and an attempt by 2 Leicesters to counter-attack in the afternoon was frustrated by an ambush and by low-flying fighter aircraft.

This was the only serious aggression by the enemy, however. He dropped more stores in the eastern sector during the morning, and was in the main content to hold the Knossos road from the south and build up in the east.

The morning began for General Freyberg with his decision that, whatever the Commanders-in-Chief might decide, the position was hopeless and his message to General Wavell to that effect sent at half past nine. Unfortunately Wavell was away in Alexandria when this message arrived, discussing the situation with Admiral Cunningham, Air Marshal Tedder, General Blamey, and the New Zealand Prime Minister, Mr. Fraser. Available to this meeting were the opinions of Brigadier Falconer, who had left Crete on the Abdiel in the early morning of 24 May and who had stressed the effect on the troops of continuous and unchecked air attack.