Chapter 10: The Eighth Day: 27 May

Force Reserve and 42nd Street

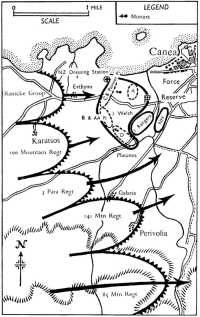

ON 26 May the enemy had gone on reinforcing. III Battalion of 141 Mountain Regiment had been landed and rushed forward to join I Battalion near Pirgos – the two battalions now made up Jais Group. There were other arrivals: the heavy infantry guns of 100 Mountain Regiment; the rest of I and II Batteries of 95 Artillery Regiment; more of 95 Reconnaissance Unit to join the part already in action towards Meskla; and medical reinforcements.

Orders had been issued by General Ringel at 9 p.m. on 26 May. Next day Utz’s 100 Mountain Regiment was to push on towards Kharakia and the southern outskirts of Canea, with Ramcke’s paratroops conforming on the left. On the right Heidrich’s paratroops would also advance and conform with Jais Group on their right. Still farther south 85 Mountain Regiment would move on Ay Marina and thence to Stilos and Megala Khorafia. And on the extreme right 95 Reconnaissance Unit would be directed from Meskla on Neon Khorion.

The main emphasis was on the roles of 141 and 85 Regiments; for Ringel had great hopes that these two would cut off General Freyberg’s main force. ‘Outflanking moves might take a long time, but they promised to gain us victory sooner in the end.’ And again, ‘a concentric attack was planned for 27 May, to tie down the main enemy force at Canea, while our forces to the south cleared the way east.’1

The enemy was of course wrong in thinking that the main force was still in the Canea area, though had it not been for Brigadier Puttick’s withdrawal the night before this might have been the case. But Force Reserve was still there and was to have an unhappy fate.

Force Reserve had moved forward after midnight and taken up positions in the early hours of the morning, still under the impression

Force Reserve, 27 May

that the left flank was continued by the Royal Perivolians of Suda Brigade and beyond Suda Brigade by 19 Brigade. The 1st Welch Battalion was west of the Kladiso River: C Company, the pioneer platoon, and a three-inch mortar covered the right front from the sea to the south of the Maleme-Canea road; on the high ground just to the south of C Company was B Company with the AA platoon; south again was D Company straddling the Prison-Canea road. A Company was in reserve behind C Company and north of the Maleme-Canea road. Battalion HQ was close to the same road a little west of the Kladiso bridge. The battalion was about 700 strong.

The 1st Rangers, perhaps 400 strong, occupied undug positions to the left rear of D Company 1 Welch. Northumberland Hussars, under 200 in strength and also in undug positions, were east of the Kladiso.

Before dawn and after it patrols were sent out by 1 Welch and 1 Rangers to make contact with the Royal Perivolians. They found no one. Shortly after daylight aircraft appeared and strafed the force heavily but ineffectively for an hour. An attack on the forward positions followed. Enemy mortars and machine guns killed or wounded many, and the fighting was the more severe because the enemy had infiltrated the forward defences before first light.

To Lieutenant-Colonel Duncan it became increasingly clear that not only were there no supporting troops on his left but that the enemy was there instead. He therefore sent off his Motor Contact Officer to report to General Weston. The officer did not return and may not have got through.

After midday the attack had become so heavy that Duncan decided he could not with an open flank hold out much longer. He must withdraw to the line of the Kladiso. He reported his intention to General Weston in a message which seems to have failed to get through. In trying to carry the intention out, his companies came under heavy fire and some of them did not come back – either because they could not or because the order had not reached them. He decided that the second position could not be held either. He therefore sent Major Gibson – on whose report this account is mainly based – to take back B and D Companies, which had managed to cross the river, and form a line west of Suda.

Gibson’s detachment set off and on the east side of Canea met 300–400 men – some from the other two units but many from all quarters. All these tried to get through to Suda but found the road already cut. By making use of all cover and taking offensive action when molested, most of them were able to reach Suda, helped no doubt by the enemy’s preoccupation with 42nd Street.

The other companies – A and C of 1 Welch and perhaps elements of the other two units – were cut off with the commanding officer. They fought on as long as they could, and at least one party of a dozen men under a sergeant, just east of the former position of 6 Field Ambulance, was still fighting next morning.2 An eye-witness account conveys the spirit of their resistance:

One incident was that of a Bren gun team. Fired bursts all day, drawing MG and mortar fire. Then must have run short of ammo. One man got out and in full view of the Germans walked 100 yds round the hillside – walked with no intention of hurrying though bullets were hitting the bare hillside. We could see every strike at his feet and above him on the slope. He got into a gunpit, emerged with two Bren mag carriers and walked back at the same pace – bullets and mortars. Then gun went into action again. ... Patients cheered the inspiring sight.3

The main body of 1 Rangers had been attacked at 8 a.m. Eventually the enemy came round the right flank, seized some high ground and consolidated with machine guns. The left flank remained open. Thus exposed on both sides the battalion remained in position till midday when it got orders, presumably from Lieutenant-Colonel Duncan, to withdraw towards Suda. This withdrawal was carried out in small parties, most of which seem to have got through to Suda in the action already described. The commanding officer, however, the adjutant, and some others made for Akrotiri Peninsula, presumably with the intention of crossing Suda Bay by boat. They were cut off. On arrival at Suda the main body got orders from General Weston’s HQ not to attempt to reorganise but to push on in small parties towards Sfakia.4

Thus the last resistance west of Canea ended and the way into the town lay open to the enemy. He for his part had appreciated by early afternoon that this was the case and so diverted 100 Mountain Regiment towards Suda, leaving the seizure of Canea itself to Ramcke’s paratroops. This took place towards evening.

The resistance put up by Force Reserve had prevented the enemy from bringing his full weight to bear on 42nd Street early in the day,5 but this hardly compensates for what was one of the unluckiest strokes of the whole campaign. The train of misunderstandings and accidents which led to it has already been as fully examined as the evidence available allows. But it can hardly be doubted that it would not have come about if it had not been for General

Freyberg’s decision to put General Weston in command of the whole forward sector. Yet the reasons for doing so were strong. All the New Zealand commanders were very tired, except Brigadier Inglis, and he had been earmarked for the command of Force Reserve. Moreover, General Freyberg hoped to withdraw the New Zealand Division behind the cover of Force Reserve and reorganise it; for this task Brigadier Puttick’s services were essential. Since the troops left forward were to be mainly English it was desirable that they should have an English commander, and General Weston, whom Freyberg had already good cause to regard as a brave, loyal, and resolute officer, was the obvious man. Such a move had the additional advantage that he knew the ground and would be able to go on controlling Suda port for which his own men, the MNBDO, would be responsible.6

The result was, however, that at a critical point of the battle Australian and New Zealand troops came under a commander whose experience was of regular British marines and who would have little understanding of Dominion troops and their special capabilities and outlook.

Thus General Weston cannot have realised that, if Brigadier Puttick thought the situation demanded it, he was quite prepared to take the responsibility of ordering withdrawal without specific orders from above – however reluctant he was to take such a course. Nor does Weston seem to have realised the necessity for keeping his subordinate in touch with his plans; for it is not possible otherwise to account for his failure to apprise Puttick of the result of his discussions with General Freyberg or, again, his failure to keep Division informed of the exact movements and timings of Force Reserve. To some such basic misunderstanding, increased perhaps by the fact that General Weston was a Royal Marine and not an infantry officer, by the extraordinary weakness of communications and by his lack of staff, and to all the standard difficulties of a battle in a state of flux, we must attribute many of the confusions of this period. Had wireless or line communication between Suda Area HQ and HQ NZ Division existed, the whole story might well have been different and many of the misunderstandings of the day would not have occurred. What in fact happened is the story of very tired and very harassed men, driven by extremely heavy pressures, and not fully acquainted with one another’s difficulties and intentions. In such circumstances a certain strain between forward and rear HQs is inevitable.

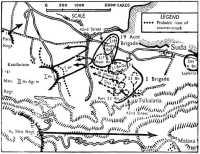

At 42nd Street the line was manned by 19 Brigade on the right and 5 Brigade on the left. Some way behind, at Suda Docks, was A Battalion of Layforce; for Lieutenant-Colonel Colvin had been directed by General Weston at dawn to hold a rearguard position there.7 Presumably the plan was that the two forward brigades should fall back through this commando battalion after nightfall.

After learning from General Freyberg about 4 a.m. that Weston was to organise and command the withdrawal, Brigadier Puttick had gone on to join his own HQ at Stilos. General Weston himself was informed of this role about 6 a.m.

In fact, however, the special circumstances made it inevitable that the rearguard should be carried out mostly by the collaboration of the two brigadiers:

I was able to have little influence on the rearguard operations until Thursday [29 May], owing to the extreme difficulty of movement on the road, the difficulty of locating rapidly moving HQ and the fact that any DR who left his MC unattended for the shortest time had it stolen. The fact that the rearguard actions were efficiently and successfully conducted was due mainly to the excellent cooperation between NZ and Aust. Brigadiers and Col. Laycock.8

The 19th Brigade, having a shorter distance to go, had reached 42nd Street by about 3 a.m. The last of 5 Brigade did not arrive till at least an hour later. Brigadier Vasey and Brigadier Hargest reported to General Weston as soon as they arrived and then, with Lieutenant-Colonel Gentry, reconnoitred the territory. On Puttick’s instruction they were to decide their forward positions in collaboration, and they chose defensive localities for the battalions as best they could in the dark. The units then moved in, the plan being for unit commanders to work out company areas as soon as daylight made this possible.

But this plan does not seem to have reached the unit commanders before daylight came. Lieutenant-Colonel Dittmer, for example, had disposed his unit under the impression that this was to be a rest area and that there was a covering force out in front. Once his companies were under cover, however, he began to feel uneasy and felt more so when he failed to locate Brigade HQ. About 8 a.m. he met Lieutenant-Colonel Allen, who shared his doubts. An encounter with General Weston made them still more uneasy:

A General wearing a rain coat, I think, and not known by either Officer Commanding, approached and asked as to what units the two OCs belonged,

and when told he replied that they should be on their way back. OC 28 Bn replied that they were ordered to be where they were and that they were going to stay there until they received further orders from their own formation. The General informed the two OCs. that they were fools to stay where they were and asked where Bde HQ was. When informed that the OC did not know he turned and moved NE. We were so astonished that we did not think of asking who he was.9

The incident suggests that Weston believed that A Battalion of Layforce and the miscellany of troops in Suda would be able to manage the rearguard. Whatever its precise explanation, it illustrates the confusion prevailing on the front. General Weston, in spite of having seen General Freyberg, Puttick and Hargest, seems not to have grasped the necessity for 5 Brigade’s presence. Hargest was under the impression that he had put his brigade into the line and that they knew attack was to be expected; and the battalion commanders believed that there was a covering force in front.

The battalion commanders, however, decided to act not upon their beliefs but upon their doubts. They found Major Blackburn of 19 Battalion and arranged to put their battalions into a defensive line. They also concerted the plan – to which the commander of 2/7 Battalion also agreed – that if the enemy got to close quarters they would open fire and charge.

The upshot of these arrangements and those already made by the two brigadiers was that 19 Brigade was on the right of the line and 5 Brigade on the left. The 19th Brigade had 2/8 Battalion from the coast to the left of the main road and 2/7 carrying the line on to the left. The 19th NZ Army Troops Company was in reserve.

On 5 Brigade front 21 Battalion Group held the right flank, linking up with 2/7 Battalion. The order of units thence southwards was 28 Battalion, 19 Battalion, and part of 22 Battalion10 Such an account, however, gives too schematic a picture. Units had become mixed up during the night march and the attempt to sort them out was not complete by the time the need for action came.11

Both brigades were thoroughly tired by now. The 19th Brigade had had its share of fighting and air alerts; and the units of 5 Brigade had been fighting or on the move by day and night almost without intermission since the battle began a week before. The men were all hungry, thirsty, and desperately in need of sleep. So now, having dug themselves holes against air attack and eaten such hard rations as they had brought with them, they mostly

42nd Street, 27 May

prepared to bed down, after first looking about to see what had happened to friends in other companies, not seen in many cases for days and, if not seen now, perhaps never to be seen again.

In this area the first thought of each man was to have a wash which we hadn’t managed to have for some seven or eight days and to drink gallons of water which had also been very short. We redistributed the available ammunition and managed to get some washing done as, by this time, our clothes were literally sticking to us. There was very little aircraft action here and the majority of chaps, always prepared to dive for cover, wandered round seeing who was still on deck and who wasn’t as most of the chaps hadn’t seen each other since the action started at Darratsos. Yarns were being swapped, washing was being done and bodies were being washed when, without any warning whatsoever, the enemy opened up with spandau fire from about three hundred yards12

The enemy had indeed arrived. Jais Battle Group of 141 Mountain Regiment had set off at dawn to cut the coast road west of Suda. I Battalion in the lead had passed through Katsifariana

about nine o’clock, brushing aside slight opposition – no doubt from Greeks. It then lost contact with Regimental HQ. III Battalion went forward in turn, in time to report that the remnants of I Battalion were falling back before heavy counter-attacks.

Apparently I Battalion had been working its way at an angle across the front, unaware that it was held. The companies, probably well spread out, bumped the whole line more or less simultaneously and a fierce fire-fight, backed on the German side by mortars and soon by strafing and bombing as well, broke out. The foremost elements of the enemy then began to fall back, with the result that they became more dense about the hinge of the two brigades and in the area of 5 Brigade.

Major W. V. Miller, commanding the right company of 2/7 Battalion, had sent forward a patrol to keep the advancing enemy under observation while he planned a counter-attack. He sent word to Captain St.E. D. Nelson, commander of the left company, asking him to join in. When the shooting started he signalled his company forward to the patrol and engaged the enemy. ‘It took a few minutes to establish superiority of fire and after this was effected the enemy broke and ran.’13 Nelson had meanwhile come up on the left and both companies charged.

On 5 Brigade front the plan already formed by the battalion commanders was at once put into action. Bayonets fixed, the troops charged forward with an élan almost incredible in men who had already endured so much. The Maoris took the lead, the units to right and left soon following. Captain Baker’s account gives a fair impression:

... As soon as B Company clambered up the bank I waved my men forward and was able to keep them under control while section commanders got their men together.

B Company were subjected to deadly fire as soon as they commenced to move forward and by the time they had moved to 50–55 yards they were forced to the ground where from the cover of trees, roots, and holes in the ground they commenced to exchange fire with the enemy, who had likewise taken up firing positions as soon as the attack commenced. I therefore gave immediate orders for A Company to advance. We moved forward in extended formation through B Company and into the attack. At first the enemy held and could only be overcome by Tommy-gun, bayonet and rifle. His force was well dispersed and approximately 600 yards in depth and by the time we met them their troops were no more than 150 yards from 42nd Street. They continued to put up a fierce resistance until we had penetrated some 250–300 yards. They then commenced to panic and as the troops from units on either side of us had now entered the fray it was not long before considerable numbers

of the enemy were beating a hasty retreat. As we penetrated further their disorder became more marked and as men ran they first threw away their arms but shortly afterwards commenced throwing away their equipment as well and disappearing very quickly from the scene of battle. ...14

The other companies were as ardent as A and B. Dittmer had difficulty in getting D Company back into reserve and holding on to Headquarters Company; while his Adjutant, his Intelligence Officer, and his RSM had already ‘got away to a flying start’.15

This example fired the units on either side. The two forward companies of 21 Battalion Group – Captain Trousdale’s16 A Company and A Company of 20 Battalion under Captain Washbourn – ‘went straight in’. The reserves, Headquarters Company and 7 Field Company, as impetuous and eager as those of 28 Battalion, were off before Lieutenant-Colonel Allen could stop them. Fearing that his remaining reserve, the Divisional Cavalry, might do the same (and justly, for some of them did), he hastily gave orders that they should put some troops where the other reserves had been. Then he himself followed the advance.

The 19th Battalion, on the left of 28 Battalion, had D (Taranaki) Company forward and 14 Platoon of C (Hawke’s Bay) Company. In concert with the Maoris these rushed forward, but found fewer enemy on their front and could not press on so far because of machine-gun fire coming from the hills to the south.

Still farther to the left 22 Battalion also charged. And even some of 23 Battalion, the reserve unit, hearing the uproar and led by Sergeant McKerchar,17 hastened into the battle.

Accounts of how far the attack was carried and what numbers of enemy were killed vary. A conservative estimate of the former is about 600 yards. And whatever the exact number of enemy killed, the figure was astonishingly large – large enough to make the German authorities inquire afterwards into allegations that their wounded had been bayoneted. The 21st Battalion reported 70 dead on its front when all was over as against 21 killed and wounded of their own. The Maoris claim 80 killed on one part of their front against four of their own killed and ten wounded. The Australians estimated that 200 Germans were killed; 2/7 Battalion lost ten killed and 28 wounded. Over the whole front the enemy can hardly have lost fewer than 300 men, and I Battalion of 141 Regiment was virtually finished in this its first action.

The experience was salutary. Colonel Jais decided that the prudent course was to keep clear for the time being of the wounded lion and take literally his orders to make for the head of Suda Bay. He therefore withdrew the remnants of I Battalion to the high ground along the road from Canea to Katsifariana. And in the afternoon he sent III Battalion forward to cut the coast road which its machine guns and the advanced parties of I Battalion had already been harassing. By the middle of the afternoon the road was cut, but patrols sent towards Suda were soon forced back by fire from 19 Brigade.

So successful had been the aggressive response of the two brigades to his first approach that even by nightfall the spirit at Jais’ HQ was still far from offensive. Jais was worried about the gaps in the defensive front that he had formed and he had fears for his right flank. He was convinced there was a superior force in front of him – ‘This enemy force was launching counter attack after counter attack to restore its situation. ...’18 And ammunition, because of the stand of Force Reserve, did not come up until late evening. He therefore satisfied himself by building up a ‘firm defensive position’ which, according to him, ‘beat off despairing enemy counter-thrusts with no difficulty’ before and after midnight.

Reports from 5 and 19 Brigades confirm the enemy’s more cautious attitude, although mortars and machine guns were troublesome and 19 Brigade had from time to time to discourage infiltrating infantry – no doubt patrols trying to get into Suda.

The really disturbing thing for the defence was the sight of enemy parties moving across the hills on their left flank – presumably the left elements of 85 Mountain Regiment. One of these parties entered the village of Tsikalaria on the extreme flank of the 42nd Street line. This was going too far. A counterattack by D Company of 23 Battalion expelled the interlopers and was rewarded by the discovery of a dump of beer and gin.

The constant procession across the southern flank occasioned a series of signals to 5 Brigade HQ during the afternoon. No action beyond the kind of local counter-attack already mentioned could be taken against it; for the guns had missed the guides the night before and were far on the road south. If the brigades stayed where they were that night they would be cut off next day and would run the risk of a much heavier frontal attack as well. The 19th Brigade, indeed, thought that a big attack might come before

dark, the pressure on its front and along the axis of the main road seeming likely at any time to mount to full strength.

The two brigadiers, however, were not at all sure what course was expected of them. ‘Neither Comdr 5 NZ Bde nor myself received any orders as to the future withdrawal of our forces, though we were aware that the whole of the garrison was withdrawing to SPHAKIA where it was hoped to re-embark.’19 This statement rather suggests that copies of the order for withdrawal issued at 3 a.m. had not reached 5 and 19 Brigades. It may be, however, that the order had reached them but that the two brigadiers felt the situation had been seriously modified by the elimination of Force Reserve which had been meant to do the rearguard, and that further orders from General Weston were called for. If Weston had intended to issue further orders to meet the new situation, it can only be assumed that he was not able to get back to 42nd Street once he had left it, because of the stream of traffic.

In the absence of General Weston they had to reach their own arrangements. During the day they found Lieutenant-Colonel Colvin, the commander of A Battalion Layforce, at Suda Docks. His orders from Weston were that Layforce should delay the enemy on the road to Sfakia.

D Battalion meanwhile was about four miles from Suda, and its commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Young, had been sent out by Colonel Laycock to reconnoitre for a suitable delaying position. He eventually found one at Babali Hani. Young was also ordered to put a company at dusk to cover the main road where it turns south to Stilos. This seemed a bad tactical position and Laycock protested but was overruled by Force HQ.20

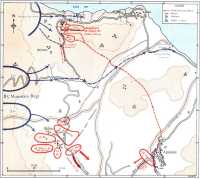

The two brigadiers, apparently thinking that the main body at least of A Battalion would cover their withdrawal through Suda, decided to go out that night, 5 Brigade making for Stilos and 19 Brigade for Neon Khorion, where 2/7 Battalion would guard the road from Stilos and 2/8 Battalion the road from Kalivia. To try and make sure of the turn-off from the coast road, Brigadier Hargest would strengthen the commandos there with another two companies.

This decided, there remained the usual problem of disengaging. It was the more difficult because the enemy became rather more active towards evening. The following from a report by Captain J. P. Snadden, who had walked from the hospital with his arm in

a sling and attached himself to 5 Brigade (where he was to command two companies of 23 Battalion as well as a platoon of gunners before the day was out), gives an idea of the conditions:

His mortars were searching blindly and collected a few of our men. One bomb killed two and wounded five Sigs personnel of 5 IB [Inf Bde] HQ who were sheltering in a slit trench. Though there was little food there was water in two good wells but these involved some risk as Jerry had his mg laid on fixed lines to their approaches and fired up the olive lanes at odd intervals. ... The scrap raged pretty fiercely towards evening and Jerry advanced in mass two or three times on our right, but bayonet charges by Aussies on the right rotated him somewhat and firing settled to blind sniping again. The Aussie MGs dealt out a fair walloping every time Heine collected as he was trying to advance straight up the road.

According to the plan 19 Brigade was to begin moving at 9 p.m., 2/8 Battalion first and 2/7 Battalion a quarter of an hour later. The whole brigade was expected to be clear by ten o’clock and then 5 Brigade was to move in the order of Brigade HQ, 28 Battalion, 22 Battalion, 19 Battalion, 21 Battalion Group, and finally 23 Battalion which would do the rearguard. Units were to begin thinning out at dusk in preparation for the move. And 28 Battalion, which was to leave first, was to pay for that privilege by providing the two companies for the stand at Beritiana.

The wounded were a difficulty. Since there were too few trucks to make a general plan possible, the units were left to do the best they could. The 21st Battalion Group still had a truck, and Lieutenant-Colonel Allen, to shorten the trip, ordered it to take the wounded to Retimo, thinking the road open. Fortunately Hargest met it and directed it towards Sfakia. The 23rd Battalion discovered some abandoned trucks, which two volunteers from Headquarters Company repaired under fire, and was thus able to evacuate its casualties as well as some Maoris and Australians. The fate of the rest must be inferred from Brigadier Hargest’s words:

. ... we loaded our wounded and sick on to lorries and pushed them off as far as we could. Poor chaps, little could be done for them but move them – the seriously wounded we had to leave.21

A curious incident occurred as 2/8 Battalion was about to withdraw. An escaped prisoner brought news that the enemy was aware of the intended withdrawal. The two Australian commanders decided to go on with their plan. But when the time came it was still fairly light and the enemy had become very active, bringing down a good deal of automatic fire. They therefore changed their minds and put their timing back an hour.

Beritiana–Stilos, 28 May

As a result 2/8 Battalion did not move until 10 p.m. The New Zealand battalions seem to have begun to leave about the same time or a little after, except for 23 Battalion. The time when 2/7 Battalion left is difficult to decide. According to the second-in-command, Major H. C. D. Marshall, it left at 10.15 p.m. But 23 Battalion sources say that the enemy was pressing forward and making it difficult to disengage. In order to put a stop to this 2/7 Battalion put in a counter-attack, and as a result 23 Battalion was able to withdraw about eleven o’clock, its last company, D Company, still under fire from machine guns on fixed lines. The German sources, though inclined to turn the merest exchange of fire into a counter-attack, do something to confirm this story.

Eventually at some time after midnight all the units of both brigades had passed through A Battalion Layforce, Brigadier Hargest watching his men go past from a Bren carrier on the Suda road. They had a weary march before them, and to get an idea of it we cannot do better than resort to Snadden’s account of how he and his gunner platoon fared:

Tired as we were, the thought of early relief spurred us on and we burned up the pavement of the excellent motor road which led round Suda Bay. Soon however we broke off on to a much rougher going and started climbing. Throughout there was silence broken only by the tramp of feet. Our greatest hardship was the lack of water and the fact that we could not smoke. Over the rise and down into a huge valley, the road getting worse all the time. At the bottom we see lights. These turn out to be burning stumps of olive trees which glow hotly in the breeze which fans them. What can have been the tragedy here? We strike a bridge just before we begin climbing again. A plane is heard overhead – ‘Keep still’. A yellow flare lights up the whole countryside and we are a huddled column on the roadway. How long does it take to burn out? It seems an age but it shows one thing – a well. The flare out, in we go ‘Boots and all’. To hell with planes. Two I tanks roll forward towards our friend. Up more hills and really we think we must be climbing the main ridge. Somewhere about 0300 hrs 28 May we doss down on a stony ridge overlooking the road and sleep the sleep of the just.

In much the same way all the battalions went on towards Stilos, 28 Battalion dropping A and B Companies – about company strength when combined – at Beritiana under the command of Captain Rangi Royal. As they arrived at Stilos in the hours before dawn they were put in position by the brigade staff.

By 6.30 a.m. The weary troops had collected their rations from the DID – ‘a sparse handout of grub, one can of BB [bully beef] per five men and six biscuits’.22 Sanguine spirits now hoped that

The screen of troops in front might prove effectual and that the mirage of rest they had so long been pursuing might become a reality.

Behind 42nd Street

While the two brigades at 42nd Street kept their line unbroken, behind the front the various headquarters were struggling against chaotic conditions and hopelessly inadequate communications to make the withdrawal orderly and arrange for its protection. What the one road of withdrawal was like may be gathered from General Freyberg’s description:

The road from Suda Point over Crete to Sphakia traversed steep hills and went through mountain passes to one of the most inhospitable coastlines imaginable and was well described by someone that night as the ‘via dolorosa’. There were units sticking together and marching with weapons – units of one or other of the composite forces which had come out of the line – but in the main it was a disorganised rabble making its way doggedly and painfully to the South. There were the thousands of unarmed troops including the Cypriots and Palestinians. Without leadership, without any sort of discipline, it is impossible to expect anything else of troops who have never been trained as fighting soldiers. Somehow or other the word Sphakia got out and many of these people had taken a flying start in any available transport they could steal and which they later left abandoned on the road to give away to the enemy what was taking place. ... Never shall I forget the disorganisation and almost complete lack of control of the masses on the move as we made our way slowly through that endless stream of trudging men.

Just south of Stilos the HQ of NZ Division, which had broken up during the march, established its nucleus about 4 a.m. An hour later came a message from 5 Brigade: could the guns be sent up? the only reply possible was that 5 Brigade was under General Weston’s command and that the guns could not be traced. Fourth Brigade and its units, all that was now under divisional command, took time to locate, but eventually Brigade HQ, 18 Battalion, 20 Battalion, and Major Leggat’s company from 22 Battalion were found. C Squadron of 3 Hussars also turned up, having missed 5 Brigade in the withdrawal. It was put under command of 4 Brigade.

Fourth Brigade HQ had moved along with 20 Battalion in the night, Brigadier Inglis having learnt en route from Brigadier Puttick that the brigade was to go on to Stilos. The 18th Battalion had spent the night south-east of Suda, and its commanding officer had been awakened by Major Lewis with the news that the Composite

Battalion had been ordered to move towards Sfakia. Lieutenant-Colonel Gray reasoned correctly from the weakness of the brigade that no active role was intended for it and that similar orders had probably been meant for him. He decided to continue south and reached Stilos about 9 a.m.; his B Company, which had overshot the turn-off and gone on to Kalivia, caught up with the battalion about midday. Leggat’s 22 Battalion company was located also during the day, but rather later.

The 5th NZ Field Park Company, which had been near Canea throughout the earlier phases, had worked from the beginning at various engineering jobs and had done a good deal of patrolling in liaison with 1 Welch. On 26 May it had got orders to withdraw, and late on the 27th it began its march from Suda, keeping on till eleven o’clock that night. The 7th Field Company and 19 Army Troops were forward at 42nd Street all day.

The Composite Battalion was still no more than a collection of groups: the Petrol Company, the Supply Column, 4 RMT, and those members of 4 and 5 Field Regiments who had been fighting as infantry or who had been in 27 or 28 Battery and had lost their guns. At Stilos these groups halted by the DID and had a meal – for some of them the best they were to have till the end of the war. And here the gunners sorted themselves into two groups, Major Bull leading one and Major Bliss the other – Major Lewis had gone forward and was out of contact. A third party of gunners was with Captain Snadden in 5 Brigade.

As if the confusion of troops, more or less unattached, now passing through Stilos or halting near it were not enough, enemy aircraft were soon overhead. Strafing and bombing went on all day, at their worst about 6 p.m. and continuing till an unusually late hour.23 Three trucks, a petrol dump, grass and trees were set on fire.

During the morning – perhaps because no one seemed to know where General Weston was and the situation was so confused – NZ Division asked under whose command 5 Brigade was. Creforce replied that if Weston could not be found Creforce itself would control the forward brigades. For Freyberg seems at this stage to have planned to get Brigadier Puttick to prepare a defence line farther south.

Division had an intimation of this at 10 a.m. when an LO brought orders from Creforce for Division to provide an anti-paratroop force on the Askifou Plain and a flank guard for the Georgeoupolis road. The precaution was prudent. Everything depended on keeping the line to Sfakia clear. So Puttick now gave 4 Brigade

verbal orders to guard the plain, protect the Georgeoupolis approaches, and establish control posts at the north entrance to the plain where New Zealand stragglers could be collected.

At 3.30 p.m. General Freyberg himself visited Division, ordered Puttick to move his HQ to the plain, and explained that Creforce would look after the brigades, failing General Weston. Then, later in the afternoon, Weston appeared.

At 7.15 p.m. Division’s written orders to 4 Brigade provided for a company to be posted about three miles east of Vrises and to stay there till General Weston ordered it to retire. Meanwhile 4 Brigade had produced its own orders for the move to the plain: the move would begin at half past eight, Brigade HQ leading and 20 Battalion, 18 Battalion, and 3 Hussars following in that order. Guides would be awaiting their arrival and the brigade would keep up its role throughout 28 May.24

These arrangements complete, Divisional HQ itself set off at 8.45 p.m. Hardly had it gone when an LO arrived from 5 Brigade with a message timed 6.30 p.m. This reported the day’s fighting and said that 5 and 19 Brigades intended to continue to withdraw that night in conjunction with Layforce. Artillery to cover the move and trucks for the wounded were urgently needed. Fifth Brigade’s next HQ would be Stilos.

Evidently Brigadier Hargest still felt that his best hope of getting what he needed was from Brigadier Puttick. Indeed it is hard to see where else he could apply; for he had had no contact with General Weston since early morning and did not know where Suda Area HQ was. The only remedy for this would have been for Weston to have given explicit orders that morning about the further conduct of the withdrawal or to have made some definite statement about where he could be found if he could not again get forward.

With Division gone, all Major Peart could do was show the LO where ammunition and rations were dumped and send the message on to Puttick.25

Apart from 5 and 19 Brigades, with which he had lost touch, the only organised units under Weston’s command were A and D Battalions of Layforce. Even so, A Battalion was at Suda and almost as much out of reach as the brigades. D Battalion had been ordered to find a delaying position some way to the south;

A Battalion would hold the enemy round Suda as long as possible and then pass back through D Battalion. As an extra precaution D Battalion was to leave a company where the road turned off south at Beritiana.

Lieutenant-Colonel Young found that the only suitable place for his main delaying position was Babali Hani. It was well to the south and so less likely to be outflanked by enemy cutting across the hills to the rear; it was less impossibly narrow than any alternatives farther north; and although the two withdrawing brigades could hardly be expected to get farther south than Neon Khorion on the night of 27 May, it was no doubt assumed that A Battalion would still be providing cover, although it was supposed to leave Suda on the night of the 27th.

Orders along these lines were given to Colonel Laycock by General Weston or Lieutenant-Colonel Wills some time before dawn, and three I tanks which had apparently come from Heraklion were put under his command. Suda Area HQ itself passed most of the day moving south. It can hardly have reached Neon Khorion much before midday, and at half past six it moved again for a position not far from Vrises. It moved again during the night and arrived at Sin Ammoudhari at 7 a.m. Since General Weston could not get back along the roads, had no signals, and had a staff which was exiguous and untrained for such operations, there was nothing he could do to control the rearguard. The only way to have done so would have been to be with it. And once he had gone south this was impossible.

Little is known of the actions of A Battalion, Layforce. It began its withdrawal from Suda shortly after the two brigades and went on towards Babali Hani. Captain Baker says he was overtaken by a company of commandos on his way to Stilos and that their commander complained that their training had never envisaged an operation of this kind. Indeed, Laycock had already pointed this out to General Weston and General Freyberg, and explained that his men were armed only with rifles, tommy guns, and Brens.

In the event the enemy seems to have cut off a good part of A Battalion north of Stilos, though many of them got back to Sfakia. The battalion was so disorganised by the withdrawal and its failure to disengage completely, that daylight found no covering force in front of 5 Brigade at Stilos except the ‘Spanish Company’ and Captain Royal’s two companies at Beritiana; somewhere between Beritiana and Stilos also were two of the Layforce I tanks and the light tank sent back by C Squadron.

D Battalion, meanwhile, had reached Babali Hani about midnight and Lieutenant-Colonel Young put his men into the area which they were to occupy. In this way the detailed defensive plan for this position could be worked out at dawn with the minimum delay.

At Retimo the garrison’s bad luck was now moving into the ascendant. An attempt by the RAF to drop supplies during the night had failed because there were no flares for recognition signals and the pilots could not locate the airfield. The attack on Perivolia broke down again because one tank lost a track on a mine, while the other was hit by an anti-tank shot and set on fire. Previous experience had shown that the stronghold was too well defended for infantry alone and so the attack was called off. The two companies which had made it were pinned down all day in front of the German outposts which they had almost reached and were attacked from the air as well. They could not be extricated till nightfall. Thus the last hope, had Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell known it, of breaking through to join up with the main force round Canea and Suda was gone.

Unaware of this, however, he once again pondered his determination to eliminate the enemy post. This time he decided he must try a night attack, and so plans were made for it to be put in at three o’clock next morning.

But it was not only communication by aircraft and land that had failed. Wireless messages to and from Creforce had to be in clear and it was too risky to send evacuation orders even in guarded language. Moreover, when Force HQ left Suda, General Freyberg was still without authority to order evacuation and without details of how evacuation could take place if it were authorised. He had arranged the night before for the MLC (Motor Landing Craft) to try and get through with a share of the supplies that had come with the commandos. Lieutenant R. A. Haig, RN, who commanded the vessel, was waiting near Suda Point with the intention of trying to get through to Retimo on the night of 27 May. Freyberg therefore thought there would be time to get the evacuation orders through to him for Retimo. We shall see in the sequel how here, too, misfortune played its part.

Heraklion, too, was troubled by poor communications among its other problems. Unable to get direct touch with Creforce, Brigadier Chappel sent a message through Middle East. The enemy was

posted in strength so as to cut the roads leading west and south of the town and had strongpoints on the high ground to the south-east. From these positions he commanded all the positions of the defence, which must take in the town of Heraklion as well as the airfield now that the Greek forces, after heavy casualties, had had to withdraw to the Knossos area. Enemy strength in automatic weapons was increasing daily while the garrison was running steadily more short of ammunition. It was clear that the enemy was building up for an eventual attack. The only courses open to the defence were to hold on in the present positions; to try and clear the roads to the west if that seemed advisable; to open the road to the south; to try and clear the high ground to the south; or to attack the enemy positions in the south-east. Chappel proposed to continue holding where he was and then, if supply policy made it desirable, to clear the western or southern roads.

But the pace of events elsewhere was to solve his problems in a way not to be foreseen when he drew up this appreciation. Middle East HQ sent him his orders for evacuation on the night of 28 May. A warship would arrive about midnight and would have to be clear by 3 a.m. on 29 May. Rear parties which covered the evacuation and could not be got off by sea that night would have to go south to Tymbaki.

From now on Brigadier Chappel had only to hold his perimeter, keeping his own counsel about the plans for evacuation until the time came to organise the troops in preparation for it.

For General Freyberg this was a trying day. He had been forced to act as if evacuation were to take place before he had received General Wavell’s authority to do so. Most of the day he was still waiting for that authority to come. Then there was the worry about the disappearance of General Weston and what consequences this might entail for the two brigades still at 42nd Street. And he was full of concern for the garrison at Retimo.

As soon as it was possible he sent off a message to General Wavell, at 11 a.m. The situation in the battle area was obscure, but the enemy was thought to be held up north-west of Suda and the Layforce rearguard was in readiness east of Suda. Most of the troops from the Base area, some troops who had come back from the main front, and some of the wounded were back in the area of Stilos and Kalivia. Those still at the front were under heavy pressure and enemy aircraft were everywhere active. There was really no choice about what must be done and he urged an

immediate decision in favour of evacuation so that plans could be made.26

This was followed up by a further message in the early afternoon to report that a seaplane had landed in Suda Bay behind 42nd Street, and that 5 and 19 Brigades were out of touch but might be able to fight their way out after dark. His own HQ was to move to Sfakia that night and, though he was still waiting for orders, his hand was being forced. There were rumours of enemy landing trucks in Almiros Bay, and he suggested that Middle East should land parties to protect Porto Loutro, Sfakia, Frango Kastelli [Frangokasterion], Ay Galene, and Tymbaki. Rations should also be landed.27

In fact, General Wavell was himself waiting for orders from London. At 9.30 a.m. he had telegraphed to the Prime Minister reporting collapse on the Canea front, a temporary line at Suda Bay, and no possibility of reinforcement. He explained that the enemy air superiority had made prolonged defence and administration impossible, and reported just having received a message – no doubt that sent at 3 a.m. – that General Freyberg considered the only chance for his forces was to withdraw to the southern beaches by night, that Retimo was cut off and short of supplies, and that Heraklion was almost surrounded. He ended by saying that it would now have to be accepted that Crete could be held no longer and that the troops would have to be withdrawn in so far as that was possible.28

This message elicited a response from London at 7.30 p.m. It ordered Wavell to evacuate Crete at once, giving the saving of men an absolute priority over that of material. Admiral Cunningham was to prevent any landings by sea that might interfere with the evacuation.29

But already Wavell had accepted the inevitable, and at 3.50 p.m. he sent a further message to the CIGS explaining that he had ordered the evacuation of Crete according to whatever opportunity there was.

A copy of the message to General Freyberg is not available, but it is plain enough what it must have contained: the order to evacuate, and perhaps some details of the ships available and the times. The order reached Freyberg ‘during the afternoon’.

As soon as Freyberg received this his first thought was for Retimo. He at once wrote a message for Lieutenant-Colonel Campbell which ran as follows:

We are to evacuate Crete. Commence withdrawal night 28/29 May leaving rear parties to cover withdrawal and deceive enemy. If liable to observation move only by night and lie up by day. Embark Plaka bay east end night 31 May/1 Jun. Essential place of embarkation be concealed from enemy therefore you should be in embarkation area and concealed by first light, 31 May. Make best arrangements you can for wounded. Most regrettable we can do nothing to help in this matter. Hand prisoners over to Greeks. This goes to you by hand of Lieut Haig RN, Comd MLC. Acknowledge receipt of this in clear by wireless tomorrow. We will be on move tonight. You and your chaps have done splendidly. Evacuation is due to overwhelming air superiority in this section. Cheerio and good luck to you.30

Unluckily for Campbell’s gallant force and Freyberg’s hopes, the liaison officer who was given this vital order to take to Lieutenant Haig at Suda Point got there only to find that the MLC had already gone. All that Haig could tell Campbell on arriving that night was that he had orders to report next to Sfakia. From this the most that Campbell could infer was that evacuation was probable and that in part at least it would take place from the south coast.

Meanwhile Freyberg reported to Wavell that the orders to Retimo had been sent on and that they had been told when to expect the ships and where. He himself hoped to have troops at Sfakia for protection purposes next morning. The Naval Officer-in-Command was separately informing Admiral Cunningham about the numbers to be taken off, the beaches from which they would go, and the times they would be there.

This was in hand, and the Naval Officer had reported that the plan was to embark 1000 men on the night of 28 May; 6000 on the night of 29 May; 5000 on the night of 30 May; 3000 on the night of 31 May – all these from Sfakia – as well as 1200 of the Retimo garrison from Plaka Bay on this last night.

With the universal recognition that there was now nothing for it but to evacuate, one more phase of the battle for Crete had ended. For the Navy this meant a reorientation of plans. From concentrating on preventing invasion, it would have to turn to the problem of finding ships to transport or escort troops across the hazardous seas between the beaches and Alexandria.

The change of plan found Glenroy and her escort already on the way back, and Abdiel, Nizam, and Hero likewise. Ajax and Dido, after their night sweep of the north coast, were also making for home. On the way out to Crete was a convoy of two supply ships

with escort. And Force A under Vice-Admiral Pridham-Wippell – Queen Elizabeth, Barham, Jervis, Janus, Kelvin, Napier, Kandahar and Hasty – was bound for the Kaso Strait to cover Abdiel and her consorts. They had been attacked at 8.58 a.m. by 15 enemy aircraft and Barham had been hit and a fire started. The fire was put out and at 12.30 p.m. The new orders reached them. They then changed course for Alexandria, getting there safely at 7 p.m.

Till now the Navy had been operating without fighter cover except for the one occasion when the aircraft of the Formidable had been available. From now on there was some prospect of a slight relief from these hard conditions. Air Marshal Tedder promised that he would try and put fighters into the air but said that, because of the distance from his bases, cover would be only meagre and inadequate. To co-ordinate what protection was possible with the movements of the fleet, an RAF liaison officer was attached to Admiral Cunningham’s HQ.

Over Crete itself the RAF continued to do what it could. After another night raid Blenheims and Hurricanes came back by day and shot three Junkers 88 down over the sea. At dusk more Blenheims attacked Maleme airfield and a further attack by night was made by Wellingtons.