Chapter 14: The March Attack: Deadlock

I: 20 March

(i)

‘ANOTHER lovely day – climatically’. The half-irony with which General Freyberg’s diary greets 20 March was apt; for on this sixth day of the battle the note of ultimate doubt sounds for the first time in New Zealand Corps’ tactical conversations. News converging on Corps Headquarters from above and from below racked it once more between the strategically desirable and the tactically possible. From Churchill at Whitehall issued an inquiry that forced Freyberg to consider whether the corps should persist in its attempts to smash through Cassino and open up the road to Rome or whether it should now be content to secure its existing gains in order to bequeath a goodly heritage to its successors. From the troops, scrambling in the mud and puddles, the rubble and the acrid smoke of the battlefield, came reports that equally faced Freyberg with the choice between what he called a hopeful policy and a contemplative one.

The contest resolved itself into the question whether the corps could seal off Cassino against enemy reinforcement, the Indians by blocking the northern entry round Point 193, the New Zealanders by blocking the southern along Route 6. This effort absorbed every infantry battalion of both divisions and drew 78 Division increasingly into the battle, but it failed. On 23 March failure was acknowledged and the offensive was abandoned, on the night of 24–25 March the outposts on the hillside were withdrawn and on the 26th the New Zealand Corps was disbanded. The second battle of Cassino ended with most of the town in our hands but with the enemy inviolate on Montecassino and across the mouth of the Liri valley.

(ii)

The 20th was a barren day. Strengthened by 23 Battalion, the New Zealand infantry still struggled against the defenders of the town between Point 193 and the Continental. On the northern

flank, men of 25 Battalion could make no gains in the face of heavy machine-gun fire. Lieutenant-Colonel Connolly, who was shocked with the state of affairs in Cassino, had ordered 23 Battalion to attack at first light. His A and D Companies (Captain Parker1 and Major Slee) made some ground at first but, fresh as they were, they soon found themselves as helpless as their predecessors against the barrier of defensive fire. The Maoris on their left even had to yield a few broken walls and the beaten earth they stood on, but they managed to thwart a circling movement by paratroops round their right flank. Both 5 Brigade battalions were troubled by elusive Germans who after eviction from one ruined building would reappear in another, frequently behind our forward troops. It was for this precise reason that Freyberg deplored the partial relief of 25 Battalion overnight: every able man was needed to garrison the town, and he gave strict instructions that 19 Regiment’s tanks were on no account to be withdrawn for refuelling or for any other purpose.

Another worry to the infantry in the centre of Cassino was the loss of smoke cover, which exposed them to the malice of machine-gunners at the road bends by Points 165 and 236. In part, the lifting of the screen was due to a change in the wind that nullified the efforts of the smoke-canister parties along the Rapido. But it was partly a deliberate decision, for 5 Indian Brigade feared smoke might mask new assaults on Point 193. When later in the day their pleas for smoke were answered, the New Zealand tank crews and infantry felt the benefit.

Communications were still causing anxiety. Wireless to the forward companies gave at best a fluctuating service, and from battalion headquarters to brigade the telephone line was even less reliable. For example, after a section of Divisional Signals had spent a whole night and day laying a wire from 5 Brigade to Tactical Headquarters 28 Battalion, it stayed ‘in’ for a minute and a half. At the end of another day maintenance on the line was abandoned, but by that time at least three men had been killed in trying to keep it open.

The tanks of 19 Regiment hit out at German strongpoints with such telling effect and so methodically that the enemy described the situation in the late afternoon as critical. He complained that craters and ruins prevented his anti-tank and assault guns from approaching close enough to reply, and he was even contemplating, if his own Panthers could get no closer, the advisability or necessity of handing over the difficulties of the town to the Allies and

standing on the high ground behind Cassino. But the German artillery was certainly taking a toll of our armour. Seven tanks were disabled during the day, though all but one were recoverable. Fourteen were still battleworthy, but their ambit of action was narrow, and there were times when Lieutenant-Colonel McGaffin wondered whether more could be usefully employed.

In the southern precincts, 24 and 26 Battalions were spared the sustained close fighting of the troops in the town. But they received their full quota of hostile fire, and more than once 24 Battalion had to push back paratroops who came probing under cover of darkness or smoke. Near the station the collapse of the Round House roof – a favourite target for gunners – provided acceptable cover for 26 Battalion riflemen who had taken post in the greasing pits beneath.

The men on the open hillside hung on grimly. Two air drops during the day were well aimed. Though no food canisters seem to have fallen within reach of the fifty men of C Company 24 Battalion, they gathered up tins of water and ammunition. Water they did not need, having two good wells in the vicinity, but it was now possible to distribute half a dozen hand grenades to each sangar. Not all that fell from the sky was so welcome. However, half the company were in dugouts on Point 146 and company headquarters inhabited a cave, in a well hole of which they sheltered sixteen wounded whom it was impossible to evacuate.

(iii)

The closing of the battlefield against enemy reinforcements was the grand object of planning on the 20th. To that end a triple attack was fixed for the night of 20–21 March. As a prisoner confirmed what had long been suspected – that Point 445, north of the monastery, was being used to pass troops down the ravine – 7 Indian Brigade was ordered to capture the feature. It could spare only a single company of 2/7 Gurkhas for the task. So as to open wider and to buttress the doorway on to Monastery Hill and to prevent the seeping in of infantry round Point 193, the hairpin bends at Points 165 and 236 would have to be retaken. The Royal West Kents, now in the castle, were chosen to make the assault. Porters would try to follow through to Point 435.

Finally, it was necessary to get astride Route 6 south of the town and to link up with the two outposts on Montecassino. A wider turning movement based on the station was rejected, because of enemy strength in the area, in favour of a closer envelopment. This mission was entrusted to 21 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel

McElroy), which was now detached from Task Force B and reunited with 5 Brigade. Twenty-first Battalion was directed up the slopes of the hill to join the troops on Points 146 and 202, with a line from Point 202 to the Continental as its objective and with two companies of 24 Battalion following up to occupy the ground won. The New Zealanders’ front was to be further narrowed by the relief of 26 Battalion and the Divisional Cavalry on its left flank by 5 Battalion of the Buffs and 56 Reconnaissance Regiment respectively. Seventy-eighth Division would take charge of the area of the station and extend right as far as the crossroads north of it.

On this same day Churchill signalled to ask Alexander ‘why this passage by Cassino, Monastery Hill, etc., all on a front of two or three miles, is the only place which you must keep butting at’. Since ‘five or six divisions have been worn out going into these jaws’, he wanted to know why outflanking movements were not being made. Alexander’s reply was a succinct statement of the difficulties that beset attempts to turn Montecassino from north or south. He thought that Freyberg’s attack had ‘very nearly succeeded in its initial stages, with negligible losses to us’. He was meeting Freyberg and the Army Commanders the next day to discuss the situation.2 Early on the afternoon of the 20th Freyberg received his summons to the conference. It said:

The slow progress made so far in attacking the town of Cassino with the consequent delay in launching the attack on the Monastery, combined with the necessity of preparing the maximum forces for a full-scale offensive in the second half of April makes it essential to decide in the course of the next twenty-four or thirty-six hours whether (a) to continue with the Cassino operation in the hope of capturing the Monastery during the next three or four days or (b) to call the operation off and to consolidate such gains of ground as are important for the renewal of the offensive later. It is also necessary to decide when Eighth Army is to take over responsibility for operations on the Cassino front and when Headquarters New Zealand Corps is to be dissolved and replaced by Headquarters 13 Corps. In the Commander-in-Chief’s view Eighth Army and 13 Corps should assume responsibility for Cassino front as soon as the Monastery has been captured and consolidated, or alternatively immediately it is decided to call off the present offensive, but he wishes to discuss the point with Army Commanders before reaching a final decision. ...

(iv)

With this decision in suspense, we may look at front-line opinion on both sides of the hill. Almost throughout operation dickens expectations at New Zealand Corps had oscillated like the needle of an excited seismograph, not only from day to day but almost from hour to hour, but the mean of these oscillations had been

distinctly on the side of optimism. The uncertainty of communications from the front, added to the very real difficulty of fixing locations on the map in a devastated area, helps to explain the alternation between hope and caution. Often the balloon of optimism, inflated by an early fiction, was pricked by a subsequent fact. The Corps Commander, for example, founded a picture of armour accumulating across the Rapido for the break-out on the false report that a tank had reached the southern stretch of Route 6. Even when one disappointment succeeded another, spirits were revived by the thought of uncommitted resources and of the sore straits of the enemy. And every new decision for the conduct of the attack brought its proper flush of hope.

By the 20th illusions were difficult to support. It was recognised that the wastage of the Indian division would soon necessitate its relief. The problem of supplying the men on the hillside was unsolved. The lessons of street fighting, it was freely acknowledged, had yet to be mastered. The step had been taken of committing the last New Zealand infantry. Seventy-eighth Division was already on a broad front. The enemy in Cassino was thought to have been reinforced. ‘People on the spot are depressed with the situation and we have to take their view,’ said the General in discussing the next day’s decision. Later that evening Brigadier Burrows had a more cheerful appreciation from 5 Brigade. Although the Germans were thought to be numerous in the town, our men’s morale was high and they were confident that they were wearing the enemy down.

The Germans’ resistance at Cassino had its limits, but should it end there it would be resumed on the heights beyond, and no general collapse was likely. Even to win the town the Allies would have to persevere for a few more days. So much is clear from an appreciation by 14 Panzer Corps on the 20th. Cassino was proving a steady incinerator of German infantry. The remnants of 3 Parachute Regiment had lost all identity as battalions and had become fused into a single group, daily concentrating more tightly in the western edge of the town. One battalion commander had had to be replaced because of exhaustion, but the men were undaunted and their spirits were high. Senger would not hear of replenishing them with second-line troops: to water down the quality of the defence would invite disaster. Even II Battalion 115 Panzer Grenadier Regiment, the one alien body among the paratroop heroes of Cassino, had been in part unreliable. ‘Only the toughest fighters can fight this battle’. Allied tanks, while not venturing within range of the Ofenröhre, had come close enough to be able to destroy the fixed defences piecemeal. To counter them, only

one assault gun was left in the town. The blocking of Route 6 as it entered Cassino prohibited close support by the tank company of 15 Panzer Grenadier Division and by a company of Panthers from 4 Panzer Regiment, but the grouping of the foremost artillery outside the town for the purpose of direct support had produced good results. In the Liri valley the German gunners, under the scowling eye of air OPs, were in a miserable plight. As alternative positions were few and, once occupied, soon spotted, the gunners preferred to remain in old positions, where they at least had the protection of dugouts. Around the nebelwerfers, shelling had ploughed the ground into a morass.

Summing up, [wrote Senger] the enemy’s air superiority, artillery superiority and ... superiority in tanks all make it improbable that Cassino can be held for any length of time. It is likely that the wastage of the infantry in the town will compel us to pull back gradually to the line between the Abbey and the present left wing of the Machine Gun Battalion. The enemy has suffered heavily, but he is not exhausted, as he is only attacking at this one spot and has fresh reserves.

II: 21 March

(i)

The double effort of 4 Indian Division on the night of 20–21 March was unavailing. Separated from the monastery by the steep gully that had foiled other Indians a month before, Point 445 was still strongly held, and the company of 2/7 Gurkhas gave up after two hours of fighting that cost numerous casualties.

Down the eastern slope of the mountain the Royal West Kents sallied forth from the castle and occupied the yellow house, half-way to their objective, Point 165, without mishap. Then luck deserted them. While digging in, one soldier of the platoon detailed to hold the house struck a mine. A whole minefield was set off and the upheaval drove the attackers back to the castle to reorganise. The enemy was now alert and when the company tried to leave the castle machine guns trained on the gate penned them in.

Another disappointment for the Indians was the failure of the porters to get through to Point 435. The day’s air drop, however, was successful, though the Germans tried to misguide our aircraft by firing green smoke on Monte Trocchio in immediate imitation of our indicator on Hangman’s Hill.

So far was the division from an offensive success that it had to look urgently to its own security. Raiding Germans about Point 175 and between there and Point 193, 600 yards to the south, touched a tender spot, for this patch of hillside overlooked Caruso road,

5 Indian Brigade’s main supply line. Reinforcements and mines were hurriedly brought up in order to make each point firm, to knit them to each other and both to 7 Brigade on the right in a system of mutual support and to block infiltration.

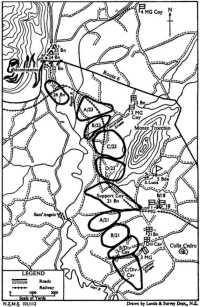

While the Indians strove to seal the northern aperture, the New Zealanders were throwing in their last reserves to picket the south of the town. Lieutenant-Colonel McElroy’s final orders to 21 Battalion entrusted the operation to D and C Companies (Major Bailey and Major Smith). D Company was to thrust down Route 6 to subdue the strongpoints in the area of the Continental Hotel. C Company would then pass through, clear the slopes up to Point 146 and there link up with C Company 24 Battalion. The rest of 24 Battalion would follow up to strengthen the chain of posts that would swing in an arc running from about the Botanical Gardens to Point 202 and bestriding both arms of Route 6.

The two assaulting companies made a slight dent in the defences but no penetration. The men of D Company were hindered by swampy ground, but when a detour brought them within 100 yards of the Continental Hotel they were enmeshed in a deadly crossfire and then counter-attacked. One platoon and most of another went down in the rush. C Company found the battlefield a tangled confusion. It groped forward through promiscuous pockets of Germans and Maoris and by daybreak its platoons lay in unconcerted dispositions vaguely north-east of the Continental, and probably nowhere nearer than 200 yards. Rubble and mud, not to mention a block of well-defended ruins, stood fairly across the way forward. The battalion had lost seventeen prisoners in exchange for about half as many. As its failure to get forward left 24 Battalion without a specific mission, the three companies of the 24th in the town regrouped, A and B Companies coalescing into one of about seventy men under Major Turnbull.

The grim work of eroding the stronghold beneath Castle Hill again occupied 25 and 23 Battalions. The 25th, unable to summon tanks to its assistance, for the most part lay low, but the 23rd, stronger in numbers, fought hard until the solidity of the defence and heavy losses brought it to a halt on a line running about 100 yards from the foot of the hill. Infiltration was especially irksome farther south in 26 Battalion’s sector, but the battalion was now so reduced in strength – A and D Companies could muster only twenty-three men between them – that it could not garrison all the ruins. Thus surrounded, the platoons dared not venture out of their shelters by day. The tanks of 19 Regiment were finding it discreet to cruise about in order to dodge mortar bombs. It was

becoming clear – and the enemy knew it – that the best help they could give our infantry was to knock down points of resistance with their guns; but the going was rough, smoke clouded the gunner’s sights and ignorance of our men’s whereabouts often restrained his fire. To improve co-operation the tanks began to be fitted with No. 38 wireless sets to be tuned to the infantry net.

By now the New Zealand infantry in Cassino were in as much disarray as their adversaries. New arrivals and muddy, stubble-chinned veterans of several days’ standing, stretcher-bearers and signallers, ‘O’ parties from the gunners, straying sappers and dismounted tank crews, section posts and company headquarters – all rubbed shoulders in the press of battle. And Germans often intermingled with them. North of Route 6 in order from the right the New Zealand positions were held by 25, 23, 28 and 21 Battalions, and to the south 24 and 26 Battalions manned a line curving from the sunken road back to the crossroads that marked the Division’s left flank. But no tidy picture is possible.

A nest of battalion headquarters in the convent served as a kind of control centre. It could give rough directions to men bringing up the rations, provide primitive shelter while stretchers were loaded on to jeeps, act as a rallying point for lost infantrymen or as a rendezvous for the more aware and even compose the gossip of the battlefield into something resembling a tactical picture. Mere presence in Cassino generated among the soldiers a fellowship that was less lasting but not less strong while it lasted than the ordinary loyalties of battalion or regiment, for to enter Cassino was consciously to step into a well-defined arena. To this feeling the convent gave a local habitation.

Confusion was not complete, but communications were always chancy, so that forward troops were often unable to report their positions even when they knew them, and the town was a place of unexpected encounters. One company, for example, was awakened to the presence of Germans in the next room by bazooka fire through the dividing wall. There was one period of three days when more than forty Maoris shared a house with the enemy and only took their departure because their ammunition was spent.

(ii)

The Germans interpreted the corps attacks on the 21st as a desperate effort to force a decision during the day at all costs, and it is true that short of the wholesale committal of 78 Division tactical inventiveness was beginning to tire. The General still set high store on the drive by 21 Battalion to link up with the men on

the hill, who, though hungry, were well supplied with water and ammunition and in good heart. But when the day’s reports had been sifted of their wishful thinking the residue was the blunt fact that ‘progress today was just a matter of odd buildings’. Before he left for the Commander-in-Chief’s conference in the afternoon, Freyberg had asked Lieutenant-Colonel McElroy for his frank opinion whether 21 Battalion could get through by night. Back over faulty communications came ‘a long answer to say no’. Nevertheless, the conference made a temporising decision: for the time being at least the offensive was to be pressed. This is as Churchill would have wished. On this day he had signalled Alexander his hope that the operation would not have to be called off. ‘Surely the enemy is very hard pressed too,’ he added.

In Freyberg’s mind also this was a cause for perseverance. There were other arguments. Our infantry had got to the very edge of the town, and the Germans admitted that only resolute counter-attacks had kept their men in Cassino at all. It was believed that by working between 23 and 28 Battalions our tanks could command the southern arm of Route 6 and close by fire what the infantry had so far failed to cordon off. It was hoped too that 21 Battalion would now know its ground and would be able to make better progress that night, though the moon, which rose only two hours earlier than the sun, was no longer an ally.

III: 22 March

As it happened, no blow was struck on the night of 21–22 March. But from first light hard fighting developed and by midday it had risen to a savage intensity unusual even in Cassino. The New Zealanders battled with a vehemence born of the knowledge that the sands were running low. As he surveyed the field Freyberg was struck by the disparity between the volume and the effect of his corps’ fire-power. He determined to pursue his advantage and bring to bear every weapon that would help pummel a fainting enemy into collapse. Tanks in the north of the town were to hammer away at the two hairpin bends of Points 236 and 165, tanks in the station area were to take the southern stretch of Route 6 under fire, tank-destroyers and 17-pounder guns were to step up their campaign of levelling enemy-occupied buildings, trench mortars in the town and on Point 193 were to be thickened up and used mercilessly, 78 Division was to exert pressure up to and even across the Gari in the south, and artillery and air support were to be fully maintained, with special attention to offending nebelwerfers.

It was the enemy who made the first move. At dawn a company of 1 Parachute Regiment climbed up towards Point 193 from the wadi to the north, bringing with it a detachment of engineers to throw heavy charges into the castle. The Royal West Kents broke up the attack with vigorous fire, capturing twenty-seven of their assailants and a further eight Germans who came from Point 165 to pick up wounded, and they inflicted perhaps thirty casualties. This was a good beginning, but the rest of the day was only to confirm the ascendancy of the defence.

The main effort of the New Zealand Division was made by a composite force of A Company 21 Battalion (Lieutenant Kirkland)3 and D Company 23 Battalion, with 25 Battalion demonstrating on the northern flank and several tanks of 19 Regiment engaging strongpoints. The intention once again was to crush the enemy at the eastern base of Castle Hill. That done, the New Zealanders would link up with the garrison of the castle and form a line facing south-west – possibly the line of the stone wall running up the hill – which would close the town from the north and enable some of the troops in northern Cassino to be rested. Frontal assaults had cost so much blood and toil that the method chosen was an oblique approach from the school area up the north-eastern ridge of Castle Hill, whence the intruders could swoop down upon the Germans from their flank or rear.

The realities were less kind. Efforts to launch the attack seem to have broken down several times – once because of difficulty in making contact with the tanks, then because the men in the tanks could not see through the smoke to shoot, and finally because wounded making their way down from Castle Hill obstructed the line of fire. When at last all was set, the attack progressed for a while and a few buildings were cleared, but the manoeuvre was detected and then the fire came down, heavy and accurate and the more deadly because the New Zealanders had to scramble across craggy ground with jutting rocks and sharp precipices that forced them into single file. Nothing remained to be done but to hug the earth until the order to withdraw came late in the afternoon.

It was the tanks that caused the day’s crescendo of hope. Their shooting was good both against the strongpoints round Point 193 and farther south. Some of them were conducting a sort of shuttle service between the Bailey bridge on Route 6, where they replenished their ammunition, and the farthest negotiable point west along the road, where they discharged it at the Hotel Continental and the Hotel des Roses. One salvo was reported to have flushed fifty Germans from the latter. From the station area tanks

fired hard across Route 6 at the enemy workings round the Colosseum. General Freyberg, confident that the tanks held the key to success, was delighted that fire was being brought down effectively on the southern entrance to Cassino. He knew that some prisoners held little hope for the Germans in the town unless they could be reinforced and supplied; those taken in the fighting for Point 193 had had no food for three days and were short of weapons; the corps intelligence officer (Captain Davin)4 thought that the breaking-point was near. At last it seemed that the steel cordon round Cassino was being pulled tight.

Yet with Brigadier Burrows’ evening report came the diminuendo. Territorially, in spite of the tanks’ good work, there was little improvement. General Parkinson later confirmed this estimate: the enemy still held the day’s objectives and there was another day’s fighting in mopping up the town. The German view was that there were many more. Heidrich was almost jaunty. He thought that the Allies had lost their dash, and with two battalions now in reserve he faced the future with assurance. The garrison of Point 435 was ‘defending itself with the greatest hardihood’, but its extinction could easily wait.

The Germans also had reason to take hope from the day’s portents in the air. The 22nd was remarkable as the first day on which the enemy flew more sorties than the Allies. Most of our twenty-seven sorties were supply missions. The dropping was not faultless, but the 24 Battalion men by slipping out smartly from their shelters salvaged enough ‘K’ rations and packs of chocolate to feed themselves for two more days. The enemy aircraft strafed and bombed Route 6 in the forward areas and attacked anti-aircraft emplacements, but on the whole the defence more than repaid the inconvenience, filling the sky with menace and shooting seven victims out of it. Our field gunners were beginning to feel the strain of an arduous week’s work. Fourth Field Regiment, the great supplier of smoke, had to borrow thirty anti-aircraft gunners to keep its 25-pounders in action. On this day the regiment fired 7456 rounds of smoke and 570 of high explosive – a typical Cassino expenditure of more than 300 rounds a gun.

IV: 23–26 March

(i)

As early as 20 February, after the first New Zealand failure at Cassino, General Alexander was planning a major regrouping

of the Allied forces in Italy.5 His great strategic purpose was to compel the enemy to commit as many divisions as possible in Italy at the time OVERLORD was launched. The best method in his judgment was so to destroy enemy formations that they would have to be replaced from elsewhere to avoid disaster. But as a local superiority of at least three to one in infantry was thought to be necessary to penetrate prepared defences in the Italian terrain, his forces would have to be strengthened and then massed at the point of attack. Against 23 or 24 German divisions in the whole of Italy, the Allies had 21, which were now to be reinforced to 281/2. The overwhelming preponderance of this force would operate west of the Apennine divide. Leaving a corps directly under Alexander in charge of its sector on the Adriatic, Eighth Army would move west, as five of its divisions had already done. Its new sector would lie between the existing inter-Army boundary on the right and the Liri River on the left. There it would assume command of most of the British troops in Italy except those at Anzio, and Fifth Army would concentrate on the southern flank from the Liri to the sea, with responsibility also for the Anzio bridgehead. This regrouping was to be the prelude to a triple attack – by the Eighth Army up the Liri valley, and by the Fifth Army on its main front through the Aurunci Mountains and from the bridgehead towards Valmontone. It would take some time to regroup and mid-April was the earliest date for the launching of the offensive.

On 28 February an Army Commanders’ conference agreed to this plan and in part elaborated it. One decision was to appoint 13 Corps to relieve New Zealand Corps after its attack at Cassino, with command over 2 New Zealand, 4 Indian and 78 Divisions. Alexander’s message of 20 March foreshadowing an early decision on policy sprang therefore not only (if at all) from Churchill’s gentle spur but from a wish not to jeopardise his plans for regrouping by unprofitable delays. Alexander had to balance the timing of his spring offensive against the chance of last-minute success at Cassino. On the one hand, the timetable must not lag unduly; on the other, Churchill was known to want results, and the capture of the Cassino massif, if only it could be pulled off, would start the offensive in April or May with an immense advantage.

Already on the 20th it was evident that New Zealand Corps would have to retrench its original ambitions. It seems probable that at the conference on the 21st operation dickens was officially decapitated of its pursuit phase, but the corps was given an extension of time to complete the conquest of the town. After

Cassino, night 23–24 March

Clark had visited Corps Headquarters on the morning of the 22nd, Freyberg revolved with Keightley the possibilities of an effort by 78 Division to take the monastery from the hills to the north-west, where the Indians had been repulsed a month before. They agreed that the operation would be hazardous without surprise, but 78 Division was ordered to prepare a plan.

By the 23rd – a day of wind and light snow – a final decision could no longer be postponed. In the morning Freyberg held a council of war with the commander of 13 Corps (Lieutenant-General S. C. Kirkman), the three divisional commanders, the CCRA and the CE. For two hours or more the whole Cassino problem was tossed and turned this way and that and thoroughly worried over. Points of view diverged but they set out from the same premise – that the New Zealanders had no more offensive action in them. They had made no headway the day before and it seemed to both Freyberg and Parkinson that the Division had ‘come to the end of its tether’. The rubble defences had not been overcome. It was equally undeniable that 4 Indian Division was fought out. Its

5 Brigade had wasted away on Montecassino; its 7 Brigade had been for six weeks steadily losing men in the hills; its 11 Brigade had been partly broken up to reinforce the other two; and the division had even had to borrow a battalion.

Discussion therefore turned on other questions – whether the corps should commit the rest of its resources in a last endeavour to leave a tidier bequest to its successor, and if so where; or whether, admitting deadlock, it should stabilise the line, and again if so where. The proposal of a 78 Division attack on the monastery from the area of Point 593 was reconsidered, only to be rejected as too slow to mount, difficult to support with gunfire and condemned by experience.

Two offensive possibilities remained. One, which was canvassed more fully after than during the conference, was to turn the town from the north and west through Point 165. A point in its favour was that prisoners taken from that area were dejected. But Point 165 seemed proof against attacks from Point 193 and the alternative approach, from Point 175, was barred by the deep gash of the re-entrant running down from Point 445, which was certain to be strongly defended.

That left one chance. An enveloping movement south about to join with the garrison on Point 435 had been broached before: now it was examined. What was envisaged was an advance by a brigade of 78 Division from roughly the station area across the Gari and Route 6 and up the south-eastern face of Montecassino. Tactically, it conformed to Freyberg’s notion that the way to win the battle was to isolate the enemy from his supplies, though he still harboured suspicions of an underground system. Given food, the Gurkhas were prepared to stay on Point 435 for two or three days longer.

But the more closely the plan was scrutinised, the larger loomed the difficulties. Any hope of surprise could be discounted. Behind the Gari, which was five feet deep and running fast, lay a belt of strongpoints manned by watchful Germans and the Hotel des Roses, militarily speaking, was as solid as rock. The approach to the objective lay for some distance across flat ground wide open to enemy observation; and when that had been crossed the way was straight uphill frontally into the very jaws of the defence. Nor could the operation be mounted in less than three days. No one enthused over it, but it was the fittest and it survived for higher consideration.

Opinion, however, clearly inclined to a pause in the offensive. It would be necessary to recall the troops from Montecassino, but

there was general agreement that the extremes of the ground securely won – Point 193 and the station area – should be held. To withdraw from them would be a declaration that the battle was over. To defend them would not only keep the enemy extended (the ultimate object of the battle and the campaign) but it would hold the wedge in place until a stronger force could drive it home. Again, no one relished the prospect of dwelling on a line which had not been chosen for its defensive possibilities but which was simply the high-water mark of an arrested attack. Freyberg confessed that ‘the troops in the town and the south were in the worst military position that he had ever seen troops in’. But the gravest forebodings were those of the Indian division’s commander, who repeatedly urged the hazards of holding Point 193 once the battle ended. It could be made defensible only by extensive engineering works and by securing beyond all risk Point 175 and the jail area of the town. Even then he thought it would attract fire that was now dispersed, and a terrible drain of casualties must be expected.

Freyberg’s decision fairly represented the sense of his commanders. Through General Clark, who concurred, he advised the Commander-in-Chief that the operation should be suspended and the isolated posts withdrawn from the hill. The plan of a 78 Division attack from the south was passed on, but without any positive recommendation.

When Alexander came forward that afternoon to see the ground again and to hear the arguments for himself, he seemed disposed to try the 78 Division venture as a last chance. Certainly he wanted to question a prisoner from the south, and there were long discussions in Freyberg’s caravan, from which Freyberg emerged with his views apparently challenged but unchanged. Alexander left at nightfall for final conferences at Fifth Army and at 9.30 p.m. his decision was telephoned to Freyberg. The corps would stand firm where it now stood and the change of command would take place in a few days.

One last effort to conjure victory out of deadlock perhaps deserves record. On the morning of the 24th, the GSO I of 4 Indian Division proposed a night attack on the monastery with a fresh brigade. Let the Castle Hill garrison strike at Point 165 to take or at least to contain it, while the fresh troops made a mass infiltration uphill to Point 435 and thence to the top. Hangman’s Hill was to play Anzio to the abbey’s Rome. Both Freyberg and Kirkman warmed to the idea, but Galloway objected and Alexander dismissed it without hesitation. He had come not to revive a corpse but to bury it: planning to reorganise the front proceeded.

(ii)

The decisions of 23 March set in motion a long train of disentanglement and rearrangement. This process occupied nearly a week and its object was not only to allow an offensive to dwindle slowly away but also to give effect locally to Alexander’s strategic regrouping. The larger intention may be described first. New Zealand Corps was to be dissolved on 26 March, handing over to 13 Corps, which would simultaneously come under command of Eighth Army. This was one in a sequence of reliefs that by the end of the month would range five corps across the peninsula from the Adriatic to the Tyrrhenian in the order 5 Corps (directly under the Commander-in-Chief), 2 Polish Corps and 13 Corps (Eighth Army), and the French Expeditionary Corps and 2 United States Corps (Fifth Army). Within 13 Corps 4 British Division would hold the Monte Cairo sector on the right, 78 Division would relieve 4 Indian Division in the centre, and on the left 2 New Zealand Division would continue to hold Cassino and extend its left to cover the old 78 Division sector as far south as the inter-army boundary.

While preparing for this redeployment, New Zealand Corps had also to wind up the battle without seeming too obviously to do so. The isolated posts on Montecassino would have to be withdrawn; otherwise not an inch of the hard-won gains was to be yielded. The corps’ policy was defined in an operation instruction issued on the morning of 24 March as one of active defence with vigorous patrolling. Positions were to be wired and mined and field works were to be employed wherever possible. Plans for counter-attack were to be made ready. The instruction indicated six points which were to be heavily defended as vital to the holding of the line, including Point 193, the north-west part of the town, the area west of the Botanical Gardens, the railway station and the hummock. Tanks already in Cassino were to remain there in close support until the reorganisation was complete, when they would be withdrawn into infantry brigade reserve in a counter-attack role. To reduce hostile shelling there was to be no unnecessary movement by day in the forward areas, and active counter-battery fire was to continue. For security reasons the telephone was to be preferred to the wireless. Beginning on the night of 25–26 March, the New Zealanders’ relief of 78 Division was to be complete by the night of 27–28 March.

(iii)

One of the earliest tasks of the corps was to disengage its troops on the hillside above the town. Since 18 March they had been

supplied exclusively from the air; 194 sorties had been flown for the purpose on seven different occasions. Despite the enemy’s trickeries to mislead the aircraft and the resiting of his anti-aircraft guns to harry their run-in, about 50 per cent of the loads fell where our troops could retrieve them. Some days no food was gathered and both parties, Indians and New Zealanders, went hungry; but the only serious shortage was the Indians’ lack of radio batteries, most deliveries of which floated wide. Ammunition stocks were abundant. There was plenty of water, for not only did the containers fall luckily, but both parties drew upon local wells until the Indians found a dead mule in theirs. Though there were a few light skirmishes and much sniping, shelling (from friendly as well as hostile guns) was the severest hardship; but perhaps cold and hunger were worse. The German policy was to let these outposts wither from their own isolation. It was not until the 21st that the enemy identified the troops on Point 435 as Indians, and then only from a report by a German NCO who had escaped from them. Major Reynolds’s New Zealanders on Point 202 were kept in daily touch with the Indians above them by the visits of a Gurkha officer.

To guard the secret, it was decided to transmit the orders for withdrawal by word of mouth. On the night of 23–24 March three officers who had volunteered set out separately across the hillside, each with a carrier pigeon to take back the news of the success of his mission. One officer was intercepted, but the other two reached Hangman’s Hill and passed on three prearranged signals – by radio code-word, Very lights or bursts from Bofors guns – any of which would be the order to withdraw. Major Reynolds received the warning to evacuate when he visited the Gurkhas early on the morning of the 24th. That day’s air drop was a spectacular success. A copious shower of food, drink and raiment descended on the New Zealanders – potted meat, ‘M & V’, sardines, mincemeat, Indian bread, milk, tea, sugar and eight gallons of rum, cigarettes and clothing. The New Zealanders watched their windfall jealously until the light waned, calculating that they would have enough rations for a week, but they had barely begun to collect the canisters when the word came through to withdraw. God’s plenty had to be left behind. But they marched out, or rather slipped away, in good order, carrying the standard burden of personal weapons and ammunition and their emergency rations still unconsumed.

Fortune for once favoured the brave. As General Freyberg predicted, the evacuation was achieved without a casualty. While our guns thundered and our tanks made distraction in the town, and while the Royal West Kents preoccupied the Germans on Point

165 with a diversionary attack, the Indians and New Zealanders in fighting patrols of about platoon strength made good their crossing of the hillside. They went unhindered. Within less than two hours, C Company 24 Battalion was back at the quarry in Caruso road, having passed through the bottleneck by climbing the wall that ran down from Castle Hill. Major Nangle described afterwards how the Indians had to work forward between two lines of shells bursting across the hillside:

Between these walls of fire lay the way to the Castle [he wrote]. We continued to move slowly across the face of the hill. The artillery fire quite covered any noise we made as we stumbled over the loose stones. A slight deviation allowed us to give the Brown House [the Continental Hotel] a wide berth as we were uncertain whether it was held or not. No sound came from this ruin and we continued, hardly believing our good luck, to the Castle. We filed up the narrow path and were challenged by the West Kents.6

So ended what for some had been a nine days’ ordeal.

Three New Zealand officers and 42 other ranks returned from Point 202. From Point 435 the numbers who came back were 12 officers and 255 other ranks, the great majority from 1/9 Gurkha Rifles, but including some from 1/4 Essex Regiment and 4/6 Rajputana Rifles. Eleven wounded – nine New Zealanders, an Englishman and an Indian-were left overnight just north of Point 146 and brought in next morning. According to one account,7 the last stretcher party was given a card by an enemy patrol stating that in future the German divisional commander would not permit the evacuation of casualties under the Red Cross.

The implication – that the enemy command was unaware of the withdrawal – is confirmed by the documents. A puzzling series of entries in the records of 14 Panzer Corps attributes to the men on Point 435 a desperate defence against fighting patrols on 26 March, nearly two days after they had left; and it is not until 27 March that 1 Parachute Division claims to have retaken Point 435, where ‘the enemy lost heavily’. The mopping up of stragglers is then said to have begun and its completion is reported on the evening of 30 March, along with a tally of casualties and trophies of war – 165 dead, 11 prisoners, 16 light machine guns, 2 German machine guns, 2 heavy machine guns, 103 rifles, 38 machine pistols, 4 wireless sets, 4 bazookas.

At what level this fantasy originated it is not possible to say with certainty. But a clue may be contained in the story told by a German prisoner many miles away and several months later. On 10 August 1944 troops of 13 Corps captured

Lieutenant-Colonel Egger, commanding 4 Parachute Regiment, who was run to earth in a Tuscan orchard after having escaped once. In an expansive mood he told his interrogator that during the Cassino fighting his headquarters was on Montecassino – a verifiable fact – and he added that he himself led the attack upon the Gurkhas who had penetrated the positions, and restored the critical situation.8 Whether or not the offspring of vanity, the reports to 14 Panzer Corps served the Allied cause by concealing the informative truth that Point 435 had been freely evacuated.

For the Indians and New Zealanders who had held on so staunchly the evacuation was a bitter disappointment. Themselves the curiously passive centre of the last week’s fighting, the still pivot on which the battle turned, they were tired and hungry and their limbs were weak for want of exercise. But the faith and fire were still in them, and had the acceptable hour come they would have roused themselves up and crossed the crest of the hill to assault the ruined abbey. When warned for the withdrawal, the Gurkhas wanted to know who would relieve them.

(iv)

Meanwhile the New Zealanders were regrouping in Cassino. The intention was, without perceptibly diminishing fire-power, to thin out in the town so as to rest troops, to organise a defence in depth and, above all, to expand over a much wider front. A start was made on the night of 23–24 March with the order to battalions to give each company in turn two days in a rest area, for none but internal reliefs could be expected. The defensive role gradually elaborated itself. An ad hoc company of 26 Battalion manned the eastern bank of the Rapido about Route 6 as a back-stop, and as a similar buffer in the north 25 Battalion sited anti-tank guns and medium machine guns between Caruso and Parallel roads and prepared a further line of machine guns and mortars in a wider arc from Caruso to Pasquale roads. The indispensable need for security in the jail area, about which General Galloway had been so emphatic, was acknowledged by a liaison between 28 Battalion and the Royal West Kents and Rajputs to establish interlocking defences at the inter-divisional boundary. Minelaying and wiring engaged the nights of forward infantry posts. Anti-tank guns, mortars and machine guns were sited; fields of fire were cleared; communications were improved. The gunners dug deeper pits for their 25-pounders and took the opportunity to stop leaky valves and replace damaged packings. Brigadier Weir could give an assurance

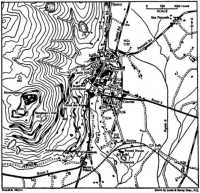

New Zealand Division’s positions, 28 March

that his guns would respond within seconds to a call for defensive fire from the Cassino garrison. The smoke screen was maintained.

The tanks of 20 Armoured Regiment gradually replaced those of the 19th, and in the town they were left in position camouflaged under the increasingly scarce cover, so that the crews but not their vehicles were relieved.

The new divisional front stretched for about five miles and a half, almost to the point where the Liri gathered the waters of the Gari and Rapido and turned south to become the Garigliano. The reliefs incidental to the occupation of this sector began on the night of 25–26 March and lasted for three nights. They were carried out at some cost in casualties but without derangement. When they were complete, 6 Brigade held a line from the north-west corner of Cassino running west of the Botanical Gardens, by way of the sunken road, the railway station and the hummock, to the junction of the Gari with a stream about 700 yards south of the station. Fifth Brigade’s responsibilities began here and extended to the Division’s left boundary, which ran east along the 13 northing (roughly parallel with, and just north of, the Liri) as far as the junction of the Rapido with the Ladrone stream and thence to Colle Cedro. In the northern sector 6 Brigade disposed four battalions – the 25th on the right under Castle Hill, the 24th between the arms of Route 6, then 22 (Motor) Battalion (now deployed for the first time since the battle began) and 26 Battalion round the station and south to the brigade boundary. Fifth Brigade’s battalions were arrayed from north to south in the order 23 Battalion, 21 Battalion and the Divisional Cavalry. The Maoris were in reserve.

The reorganisation did not at once becalm the battlefield. Our tanks and guns in particular gave the last days of the New Zealand Corps a dying illumination. Though plans were considered for sapping and blowing German strongpoints in the west of Cassino, it was left to the armour to hammer away at close quarters and to the artillery to attempt the work of demolition at long range. The two embattled hotels were now sprawling cairns of stone and brick, but they still harboured live paratroops, and they were now, if anything, more dangerous to approach. After days spent in clearing and epairing Route 6 the enemy had succeeded in bringing Mark IV tanks and anti-tank guns into the infantry zone and the New Zealand armour was beginning to feel the impact of the new arrivals.

Because of the continued exchanges in the town and perhaps because he was misinformed as to the true position on Point 435, it took the enemy some days to penetrate the Allied design. And even when he realised that one battle was at an end, movement that the smoke failed to screen led him to predict the imminence of another. On the 24th 14 Panzer Corps thought that Cassino

could be held for eight days longer. The four battalions of paratroops in the town varied in strength from a company to a strong platoon, in numbers from 120 to 40. In spite of a wastage of about forty dead a day, the ruins of the town were deemed to be worth defending if only to prevent the Allies from rolling up the whole Gari line. After two quiet days on the 25th and 26th, the German outlook brightened. On the 27th Senger was able to report to Tenth Army that enemy pressure was slackening and that as a result of reliefs by panzer grenadiers in the hills above the town the paratroops now had two battalions in reserve. They would retake Point 193 in heir own good time, seize the station if it was evacuated and follow up any withdrawal as a precaution against renewed large-scale bombing. Senger ended with a cautious claim to victory.

The second battle of Cassino has ended in our favour. But the enemy will probably launch another major attack in the corps sector very soon. He will hardly lie down under his two defeats, as they represent a loss of prestige for him, and have an undoubted effect on the morale of his armed forces elsewhere and on the international political situation. There is no indication yet just where the enemy plans to strike next.

(v)

Senger was right in predicting that the Allies would strike again, though he misconceived the timing and the weight of their blow. It was in preparation for this blow that New Zealand Corps handed over its front to 13 Corps at noon on 26 March and went out of existence. Its dissolution was therefore not merely the end of an old chapter but the beginning of a new. The story of Cassino had not yet run its course. As the days lengthened, the rivers fell and the ground became hard, Alexander massed his forces for the broad-fronted offensive that he had promised Churchill on 20 March.9

In the last hour of 11 May his two armies rolled forward in the attack from Cassino to the sea. For several days, while the French thrust deeply through the Aurunci Mountains and 13 Corps forced a crossing of the river in the mouth of the Liri valley, 2 Polish Corps fought the third battle of Cassino among the hills north and west of the monastery. It is no disparagement of the Poles’ splendid bravery to say that it availed little until successes elsewhere threatened the defenders of Montecassino with encirclement. Only then, on the morning of 18 May, did the Polish flag and the Union Jack fly above the dusty ruins of the abbey. So at last though the great fortress fell, it was never conquered.