Chapter 3: The Pursuit North of Rome

I: After the Fall of Rome

(i)

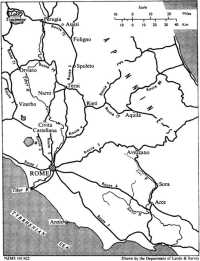

SOUTH of Rome, where the Apennines occupy nearly two-thirds of the width of the peninsula, the terrain had favoured the Germans in their defence of the Winter Line. North of the city, however, the peninsula widens, but the mountain backbone narrows towards the Adriatic coast and gives way in the west to comparatively open, rolling country little suited to the German purpose of blocking the Allied advance. North of Lake Trasimene the country becomes more rugged again, and beyond the Arno River the northern Apennines turn back towards the west to span the peninsula and block the approaches to the plains of the River Po in Lombardy. Apart from the few roads which thread their way through deep valleys and over high passes, the only gap in this great barrier is the narrow corridor of foothills along the Adriatic coast south of Rimini.

It seemed unlikely that Kesselring would attempt a protracted defence until his depleted armies reached the Arno River and the Gothic Line1 in the northern Apennines. He strengthened his right flank, which in the open country west of the Tiber River was in greater danger than the sector nearer the Apennines, by reinforcing with fresh but inexperienced formations, moving 14 Panzer Corps west of the Tiber to join 1 Parachute Corps in Fourteenth Army, and replacing 14 Panzer Corps by 76 Panzer Corps on the right of 51 Mountain Corps in Tenth Army. Kesselring gave orders for a gradual fighting withdrawal to the Gothic Line, but Hitler was

suspicious that he might want to fall back to this position without offering serious resistance and demanded that ‘After reorganisation of the formations the Army Group will resume defence operations as far south of the Apennines as possible.’2 On 14 June, therefore, the German commander-in-chief ordered that the Gothic Line was to be built up sufficiently to resist an Allied attempt to break through to the plains of the River Po, and to gain time for these preparations the Army Group was to ‘stand and defend the Albert–Frieda Line’,3 which crossed the peninsula from coast to coast and passed just south of Lake Trasimene.

(ii)

At first the Allied armies made rapid progress in pursuit of the Germans north of Rome. Eighth Army drove up the Tiber valley with two armoured divisions of 13 Corps, 6 South African Armoured Division along Route 3 west of the river and 6 British Armoured Division up Route 4 east of it; on the left Fifth Army advanced with 2 US Corps on Route 2 and 6 US Corps on Route 1 up the coastal flank. The Americans seized the port of Civitavecchia, 40 miles north-west of Rome, on 7 June and the Viterbo airfields on the 9th. Although the port had been extensively damaged, it was open to Allied traffic in less than a week.

Meanwhile the enemy also began to fall back along the Adriatic coast and 5 Corps4 started to follow up on 8 June. Orsogna – which had withstood the New Zealand Division’s repeated attacks six months earlier – was entered next day, and Chieti and Pescara were occupied and the Pescara River crossed on the 10th, the day the New Zealanders arrived at Avezzano.

General Alexander calculated that the enemy, despite the reinforcements he was known to have received, was not strong enough to hold the Gothic Line against a really powerful attack. In an appreciation to General Wilson (Supreme Allied Commander, Mediterranean) on 7 June he wrote of the Allied armies: ‘Neither the Apennines nor even the Alps should prove a serious obstacle to their enthusiasm and skill.5 He proposed to continue to press the pursuit up the centre of the peninsula and over the northern Apennines. If his armies were held in force he ‘would mount a full-scale attack on Bologna not later than 15th August. I would then establish a firm base in the area of Bologna and Modena for

the development of further operations either westwards into France or north-eastwards into Austria according to the requirements of Allied strategy at that time.’6 Such a plan would be possible only if the existing Allied forces were retained in Italy.

Alexander ordered Eighth Army to advance with all possible speed to the general area of Florence, Bibbiena and Arezzo, on the middle and upper reaches of the Arno River, and Fifth Army to occupy the region of Pisa, Lucca and Pistoia, at the northern extremity of the Tuscan plains; he authorised the two army commanders to take ‘extreme risks to secure [these] vital areas ... before the enemy can reorganise or be reinforced.’7

To carry out these orders both armies regrouped. In Eighth Army 10 Corps (6 British Armoured and 8 Indian Divisions, with 10 Indian Division in reserve) assumed 13 Corps’ responsibilities east of the Tiber River, and 13 Corps (78 Division and 6 South African Armoured Division, with 4 Division in reserve) continued its northward drive west of the river. On the Adriatic coast 2 Polish Corps replaced 5 Corps. The Canadian Corps was still in reserve. The French Expeditionary Corps relieved 2 US Corps on Fifth Army’s right and 4 US Corps took over the coastal sector from 6 US Corps.

The pursuit continued against stiffening resistance. Tenth Corps entered Perugia, east of Lake Trasimene, on 20 June, and was then checked in the hills beyond the town; 13 Corps was halted near the south-western shore of the lake. The Allied armies were up to the Albert-Frieda (or Trasimene) Line, where the Germans had established a coherent defence across the Italian peninsula. Only after hard fighting was 13 Corps able to break this line west of the lake and continue its advance. Between Lake Trasimene and Arezzo, its next objective, 13 Corps was halted again; it did not enter Arezzo until 16 July, after it had been reinforced by the New Zealand Division.

(iii)

While the Allied armies were making these gains in central Italy, Generals Wilson and Alexander were vainly striving to retain for the Italian campaign priority over all other operations in the Mediterranean. The Combined Chiefs of Staff had agreed in April that ANVIL8 (the invasion of southern France) should be deferred so as not to interfere with the offensive which was to

accomplish the capture of Rome, but also had directed Wilson to plan for the ‘best possible use of the amphibious lift remaining to you either in support of operations in Italy, or in order to take advantage of opportunities arising in the south of France or elsewhere. ...’9 Wilson therefore warned Alexander on 22 May that he intended to mount an amphibious operation not later than mid- September, either in close support of the Allied Armies in Italy or elsewhere.

The Combined Chiefs of Staff informed Wilson on 14 June that ‘they were firm in the decision to mount and launch an amphibious operation of the type and scope planned for Southern France’,10 but a choice might be made between a seaborne assault on the south or the west coast of France or at the head of the Adriatic Sea. ‘All such plans were contingent on the completion of the ground advance to the Pisa–Rimini line and the ultimate selection of an operation was dependent on the general strategic situation. ...’11 Wilson informed Alexander of this decision and directed him to prepare for the release of American and French divisions from Fifth Army for assignment to Seventh Army.

Wilson recommended a course favoured by Alexander: the continuation of the Italian offensive into the Po valley and thence, supported by an amphibious assault on the Istrian peninsula, through the Ljubljana Gap (in Yugoslavia) into Austria and Hungary, which would threaten Germany from the south-east. General Eisenhower, however, wanted the operation against southern France. He believed that the Allies could support only one major theatre in the European war, which was in France. An important consideration was that an additional port was needed for the introduction into France of some 40 to 50 divisions waiting in the United States.

Wilson received a directive from the Combined Chiefs of Staff on 2 July that he was to carry out the operation against southern France, on the target date of 15 August if possible. He informed Alexander on the 5th that the new operation must receive priority over the Italian campaign but assured him that not more than four French and three American divisions were to be taken from his command; they were to be replaced by 92 US (Negro) Infantry Division and a Brazilian infantry division. Alexander’s task was to continue the destruction of the German forces in Italy; he was to advance through the Apennines to the Po River and thereafter to a line from Venice through Padua to Verona and Brescia, on the northern edge of the plains.

Alexander realised that, with the loss of 6 US Corps, the French Expeditionary Corps and a large part of the Allied Air Force, the penetration into the Po valley before the winter set in was most unlikely. He therefore gave permission for the bombing of the Po bridges, which previously had been spared because of the engineering problems that would be involved in rebuilding them.

II: The Division at Arce

(i)

While the Allied armies were continuing their advance north of Rome, the New Zealand Division rested and trained alongside the Liri River near the village of Arce. The men settled in tents under trees, in the vineyards or on gentle slopes near the river, in a peaceful countryside well suited to the open-air life. The fine weather, however, was interspersed with occasional showers and sudden thunderstorms, the worst of which drove the men hurriedly and frantically to dig drains around their bivouac tents.

The Eighth Army commander (General Leese) advised General Freyberg on 16 June that he did not see any role for the New Zealand Division in the immediate future. After discussions with Generals Alexander and Leese the GOC passed on the information to the Division on the 20th that it would not be needed for operations for 30 days.

The New Zealanders and Canadians were left out of the advance north of Rome because Fifth and Eighth Armies were both limited to those forces which could be supplied along the available roads. It was hoped that the two armies, so constituted, would be able to push the Germans back to the Pisa-Rimini or Gothic Line, while the forces left in reserve rested and reorganised in preparation for the breakthrough into the northern plains of Italy. This plan, however, had to be modified because of the demands for troops to take part in the landings in southern France, and also because of the unexpectedly determined German resistance south of the Arno River. Consequently the New Zealand Division’s promised 30-day stay around Arce was cut short.

(ii)

General Freyberg had taken steps immediately after the fall of Rome to secure a suitable building there to serve as a New Zealand forces club, and also had made a personal approach to General Alexander for permission to send men on daily conducted tours of the city. The Division took over one of Rome’s best hotels, the

Quirinale, in the Via Nazionale. Leave was not generous and the decision that other ranks were not allowed to stay overnight (only a limited number of officers, nurses and VADs could do so) was not at all popular. Every man was keen to get to Rome, and more succeeded in getting there than were supposed to do so under the scheme of daily leave apportioning.

An officer describing his first visit to the city says that ‘the Catholics all made a beeline for St. Peters where the Pope was giving mass to 4000 members of the Allied forces, and Mac and I started off on a sightseeing tour. ... We walked up the via Nazionale, looking into shops and watching the passers-by. The people of Rome are a different stamp from the Neapolitans and many of the women are really lovely. They are very happy to have their city liberated from the Tedeschi and posters and banners across the streets welcome the Allied soldier. Like all Italians though, they are not above making money out of the troops, and prices of everything are high. Half the trouble as usual is caused by the Yanks with their wads of lucre and their willingness to pay any price for an article they want. They shove the prices up wherever they go. ... We dropped into a bar which must have been a first class place in peace time, with mirrors all over the walls, fine glassware and elegant furnishings. We sampled some of the famous Sarti cognac, a thimbleful costing £25. It was rare stuff, almost like whisky.’

The Quirinale had not yet been opened as a New Zealand club. ‘We were thinking of going to the NAAFI for a cup of tea and a sandwich when we were accosted by an old man who asked us in broken English if we wanted lunch. We were surprised because there are no “ristorantes” open in Rome, Jerry having taken most of the foodstuffs, but we decided to see what he had up his sleeve. He led us for a couple of blocks [adding several Americans and Englishmen to the party on the way] and then turned suddenly into an inconspicuous doorway in the Street of the Twentieth of September. ... We went up six storeys and were then ushered into the dining room of a well-to-do private home. While the lady of the house set the table we looked around the carpeted and well-furnished room. An expensive radio stood in a corner and through the doors of glass fronted cabinets we could see shelves of crystal & glassware, some of it inlaid with gold. As the Yank major said – this guy musta been a Fascist to have kept all this from the Tedeschi. The meal consisted of macaroni and vegetable soup with a roll of white bread, beefsteak and beans, and cherries for dessert, so it was obviously a black market feed. The price was 150 lire but

any civilian who can turn on a meal with bread and meat can name his own price. ...’12

(iii)

Excursions were made to the Cassino battlefield. The ruins of the town had changed little in two months, except that ‘the rims of the craters on the outskirts are overgrown with weeds, and poppies and daisies are flowering about the place. ...The air is still heavy with a fetid stench from decomposing bodies and the sour taint of the phosphorus shells. ... most of the town is just a flattened chaos of stone rubble, shattered beams and severed girders, all jutting at grotesque angles and torn and twisted by high explosive. We entered the town from Caruso Rd and the first grisly exhibit was a partially intact building, heaped inside to a depth of eight feet with unidentifiable portions of human bodies. ... All over the town bodies lay where they had been struck down. ... Numbers of New Zealanders were working among the ruins, recovering mates whose uniforms alone kept them in one piece. ...

‘We left the town and went hand over hand up a rope trailing down the precipitous mine-free track up Castle Hill. Outside the castle wall, rusting weapons and shrap-riddled equipment mark the scene of many a savage counter attack made by Jerry from Pt 165 in attempts to retake the Castle. ... From the Castle we gingerly picked our way to the zig-zag road which was formerly a walled and bitumen surfaced track. Now the wall is breached every few feet and not a square yard of surface is clear of boulders and loose rocks which have been dislodged from further up the hillside. From foot to summit, Montecassino hill is strewn with the casings of the countless 25 pr. smoke shells which blinded the Abbey for two months. ... Because of the mine and booby trap danger we walked carefully the whole way up, stepping cautiously over a few dead Jerries. ...

‘Behind Hangman’s Hill the little flat is churned, by hundreds of overlapping shell holes, into an earthy mass like a potato patch which has been dug over. Between Hangman’s Hill and the Abbey there was originally a terraced garden with little stone walls and fruit and olive trees. Not a vestige of the walls remain... and the softer-wooded trees are also gone. Only the sturdier olives remain, and they are just tortured trunks. ... Fanning out from the front of the monastery, like the shingle slide at the foot of a crumbling rock face, is a great cascade of dust, mortar and shale – formed

from the shattered walls. ... No earthquake could have so ruthlessly razed the towers and domes and battlemented walls as did the bombing. ...’13

(iv)

The Division organised leave and trips to places other than Rome. Through the courtesy of the Royal Navy, parties were able to spend three days on the Isle of Ischia in the Gulf of Naples. Parties also went to Sorrento, Salerno and Amalfi, and elsewhere on the coast. Units held organised picnics at the lovely Lake Albano, in the Alban Hills, and along the banks of the fast-flowing Liri River. Concerts were given by the immensely popular Kiwi Concert Party and a British ENSA14 party; films were shown by the YMCA mobile cinema, and programmes given by the brigade bands. Units staged race meetings and organised games of cricket, baseball, basketball, athletics, swimming, and aquatic carnivals on the Liri.

The weather was so hot that exertion made men sweat. The atmosphere was still oppressive at 7.30 p.m., when anti-malarial precautions, which included the covering of bare limbs, had to be taken. The flies were also very annoying, ‘not only being persistent like the desert variety, but biting hard as well.’15

Only part of the time was taken up with leave, sport and entertainment. The usual routine was training in the mornings and exercises on many afternoons. ‘This “rest” business you hear about is really only a lot of hard work for us, training, etc. They never leave you alone for long.’16 Units were on route marches, sometimes up steep, zigzag roads to hilltop villages; they held NCOs’ and snipers’ courses and lectures, were instructed in minelifting, attended demonstrations by other arms, and carried out shoots with their own.

In a series of exercises in co-operation between armour and infantry, various combinations from regiments and battalions reached a sound basis of understanding. In one such exercise the companies of 26 Battalion advanced with tanks accompanying each platoon. ‘Guided to their targets by the infantry, the tanks did a lot of shooting which added to the reality of the scene. Radio communication between tanks and infantry was still not very successful, but when the radio failed use was made of the telephone fitted to the rear of each tank.’17

Because the anti-tank gunners had been employed as infantrymen in the recent operations and were likely to be so again, 7 Anti-Tank Regiment trained in infantry tactics and in the use of infantry weapons. The regiment received an issue of nine M10s, the new self-propelled anti-tank guns,18 which were allotted to 31 Battery. There was little time for instruction with these weapons before the Division left Arce, but as many men as possible were sent to 4 Armoured Brigade for short courses in driving, wireless operating, gunnery and maintenance. The M10 was much more vulnerable than the Sherman tank, and its crew therefore needed no less skill than was demanded of the tank crew. The conversion of 4 Brigade from an infantry to an armoured brigade had taken a year, but the men of 31 Battery were in action with their M10s three weeks after they first set eyes on these ‘tank destroyers’.

For about three weeks in June and a week in July the New Zealand Army Service Corps, assisted by men and vehicles from the artillery and the armoured brigade, was very busy carrying ammunition, petrol and supplies for Eighth Army from depots in or near the Volturno valley to dumps at Alatri, Valmontone, near Rome, and Narni (43 miles north of the city), and from Anzio to Narni. ‘Moving ammunition and supplies with a rush involved platoons [of the transport] in heavy work over long hours, and although drivers stood up well to the strain of long hours and the choked and often dusty roads, an avoidable annoyance was poor administration at some dumps, together with some double-talk of orders and counter-orders which led to a certain amount of confusion, waste of time, and ripe cursing.’19

(v)

The Eighth Army Chief of Staff (Major-General G. P. Walsh) telephoned HQ 2 NZ Division from HQ Allied Armies in Italy on the night of 7–8 July to say that he had an urgent operational role for the Division and wanted it to begin moving to a forward concentration area south of Lake Trasimene next day. This order was quite unexpected because General Freyberg had been told by HQ Eighth Army on the 6th that there was no forecast of a move for the Division for some time. The task to which the Division was summoned was to reinforce 13 Corps, whose resources were considered inadequate for an attack on the German positions

dominating the approach to Arezzo, about 20 miles beyond Lake Trasimene.

The GOC immediately called the GSO I (Colonel Thornton20) the AA & QMG (Colonel Barrington21) and the Commander NZASC (Brigadier Crump22) to confer with him on arrangements for the move. It was decided that the NZASC should start next day by sending vehicles to Civita Castellana, a town on Route 3 north of Rome, where the Division was to stage en route to Lake Trasimene, and that the first brigade – 6 Infantry Brigade (Brigadier Burrows23) was selected – should move from the Arce rest area on the night of 9–10 July. Formations were warned of the move by telephone.

The move was to be secret: all fernleaf signs and unit signs were to be obliterated from vehicles, and hat badges and shoulder titles removed. But these security measures did not deceive the Italians, who identified the ‘neo-zelandesi’ as they travelled northward.

The sudden call to the Division imposed much organising and travelling on the NZASC, many of whose vehicles were still carrying ammunition and supplies for Eighth Army. All load-carriers were ordered to return immediately to Arce, and company headquarters and workshops were to go to Civita Castellana. On the 8th the troop-carrying vehicles of the two RMT companies joined the battalions of 5 and 6 Infantry Brigades; other transport picked up ammunition, petrol and rations and went to Civita Castellana. Next day the NZASC convoys completed the second stage of the move.

The Division made the 200-mile journey to Lake Trasimene in six groups. The first convoy, 36 Survey Battery, left Arce in daylight on 9 July and was followed that night by HQ 2 NZ Division and 6 Infantry Brigade group, and on the next three nights by 5 Infantry Brigade group, a divisional troops group, and 4 Armoured

Brigade group. The convoys took about seven and a half hours to make the run by Routes 6 and 3 to the staging area at Civita Castellana, where the troops spent a day resting, and about the same time to cover the remaining half of the journey by way of Route 3 to Narni, from there to Orvieto, and on Route 71 to the south-west side of Lake Trasimene.

The first part of the journey was made over good roads and was uneventful except that it gave many men their first glimpse of Rome as they passed through its outskirts at daybreak. On

Arce to Lake Trasimene

Route 3, beyond the city, the New Zealanders saw the unmistakable evidence of the enemy’s hasty retreat under attack from the air and ground forces. The highway had been cut in many places by bombs and was dotted with wrecked German vehicles. At the Division’s staging area hundreds of vehicles and guns were parked nose-to-tail and ‘a single enemy fighter plane could have brewed up dozens of them. That such a risk can be taken, and the fact that we can move a convoy of any size in daylight is a tribute to the air supremacy maintained by the DAF and MAAF. The day was hot and a strong wind blew steadily all afternoon making the place about as comfortable as Amiriya in a khamsin. ...’24

At Narni, a town in a gorge, ‘yawning gaps had been torn in three huge arched bridges by the Jerry engineers but most of the road damage had been caused by our own bombing. At least once in every mile or so the road and railway had been straddled by sticks of bombs which had breached the highway and cratered the surrounding area. ... every few hundred yards lay the burnt-out rusting skeletons of Jerry transport. ... the total of wrecks must have run into four figures. Quite a number of tanks and S.P. guns were among the victims, and every now and then small groups of railway rolling stock sat drunkenly athwart the rails, with peppered sides and blackened ribs. ... In one place a whole double column of Jerry transport had been caught hiding in a tree-lined side road and every vehicle shattered. The Hun has been using a considerable amount of civilian transport, particularly buses and Fiat cars, to try and make up his losses. ...’25

With the arrival of 4 Armoured Brigade’s convey on the 14th, the whole of the wheeled portion of the Division was assembled by Lake Trasimene. The heavy tracked vehicles travelled on tank transporters, which completed the journey three days later. Camp sites were established under oaks and pines in a pleasant rural locality, which was found to be appreciably cooler than the Liri valley. Much of the lake was surrounded by mud and reeds, but where it was accessible for swimming the water was pleasantly warm. Some units, however, were able to make only the briefest acquaintance with Lake Trasimene at this time, for 6 Infantry Brigade was committed for operations on the Arezzo front on 12 July, the day after its arrival. The Division was placed under the command of 13 Corps (Lieutenant-General Kirkman) at midday on the 11th.

Some units, therefore, continued northward along Route 71, past Castiglione on a promontory on the western shore of the lake, and

beyond an airfield crowded mostly with Spitfires. At a railway station a little farther on ‘a whole concentration of locomotives and railway rolling stock had been beaten up by the RAF. Numerous craters were squarely in the middle of the tracks and the rails were bent back like baling wire. ... One or two [locomotives] had been ripped open like tin cans. ... Most of the coaches and trucks were burnt out while others were shattered by the explosion of their contents. ...’26

III: Monte Lignano

(i)

The Allied armies were checked right across Italy before they reached the ports of Ancona on the east coast and Leghorn on the west, and in the middle of the peninsula, the road and rail centre of Arezzo.

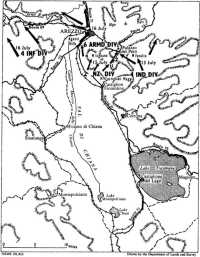

A broad and fertile valley, the Val di Chiana, leads northwards from the western side of Lake Trasimene towards Arezzo, a town four miles from the Arno River. Route 71 runs at the foot of the mountains on the eastern side of the valley and joins Route 73 (the Siena-Arezzo highway) at a defile less than three miles from Arezzo. Eighth Army advanced from the Trasimene Line with 13 Corps in the Chiana valley and the hills to the west, and with 10 Corps in the broken country of the Tiber valley to the east.

On 13 Corps’ right 6 British Armoured Division, which had taken over from 78 Division, found the enemy defending the mountain heights east of Route 71, from which he had observation over the Chiana valley. The armoured division succeeded in gaining a foothold on Monte Lignano, due south of Arezzo, and on Monte Castiglion Maggio, farther to the south-east, but failed to clear the enemy from the crests. In the corps’ centre 4 British Infantry Division and on the left 6 South African Armoured Division were unable to break through the hills west of the Chiana valley and so reach the Arno valley west of Arezzo. A major action would be necessary to dislodge the enemy and capture Arezzo, and for this 13 Corps would need reinforcement. It was decided, therefore, to bring up ‘the most readily available formation,’27 the New Zealand Division. The attack was postponed until 15 July to give the New Zealanders time to move up to the front from the Liri valley, and in the meantime a heavy preliminary artillery and air assault was made on the German gun positions.

Lake Trasimene to Arezzo

It was 13 Corps’ intention to attack the enemy in his positions west and south-west of Arezzo and continue the advance to Florence. The 6th Armoured Division was to capture the high ground south-west of Arezzo, cut the roads north and west of the town, secure crossing places over the Arno River, and occupy the town when the chance occurred. The British armoured division’s right flank was to be protected by the New Zealand Division, which

was to relieve a group named Sackforce28 and occupy the heights from Monte Castiglion Maggio to Monte Lignano; on the left, west of the Chiana canal, 4 Division was to give supporting fire.

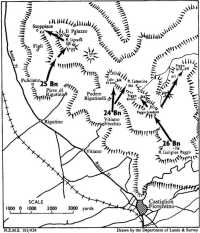

Sixth New Zealand Infantry Brigade group29 was ordered to relieve Sackforce on the night of 12–13 July. Brigadier Burrows instructed 25 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Norman30) to take over the positions of 1 King’s Royal Rifle Corps on the south-western slopes of Monte Lignano, and 26 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Fountaine31) to relieve 1 Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders on the slopes of Monte Castiglion Maggio. These peaks, together with Monte Camurcina and Poggio Cavadenti, which lay between them, rose about 2000 feet above the Chiana valley and gave excellent observation of 13 Corps’ activities to the west as well as commanding the approaches to Arezzo.

The convoy carrying 25 and 26 Battalions and their supporting machine guns and mortars left the south-western side of Lake Trasimene early in the evening of the 12th, drove up Route 71 to Castiglion Fiorentino and halted for half an hour until darkness fell. The 25th Battalion’s vehicles then went to a debussing point three miles farther up the road, where the machine guns and other equipment were loaded on mules. Shortly before midnight the battalion, using the mules and jeeps, set out to climb to the positions occupied by the KRRC on Monte Lignano. The relief was completed by 4.30 a.m. without casualties, despite some shelling and mortaring. Meanwhile, by midnight, 26 Battalion had relieved the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in the Monte Castiglion Maggio sector.

(ii)

The defence of the German position in the mountains south of Arezzo was chiefly the responsibility of 305 Infantry Division of 76 Panzer Corps, but the western slopes of Monte Lignano and the ground extending north-westward to the main road were held by 115 Regiment of 15 Panzer Grenadier Division. The 305th Division,

which was very weak although reinforced by troops from 94 Infantry Division, occupied a front running south-eastwards over a wide stretch of mountains.

Tenth Army had ordered 76 Panzer Corps to hold its existing line but to swing back its left (east) wing. It had been intended that 44 Infantry Division of 51 Mountain Corps should occupy Monte Favalto, a high peak about eight miles east of Monte Lignano, but this had not been done. Instead, troops of 4 Indian Division (10 Corps) reached the slopes of Monte Favalto on 12 July. The commander of 76 Corps (General Herr) then told Tenth Army that 305 Division’s left flank was ‘in an untenable position, and must draw back and lose control of the commanding heights. That may mean that the Corps cannot hold on for long in the rest of the sector. ...’32 Tenth Army gave orders that 305 Division’s right was to hold firm on Monte Lignano, and the rest of the division could take up a line extending over Monte Camurcina and towards Monte Favalto.

The capture of Monte Favalto by 4 Indian Division was a threat to Arezzo from an unexpected direction, and also placed the left flank of 305 Division in a dangerous salient, from which it began thinning out on the night of 12–13 July. Monte Castiglion Maggio, at the southern tip of the salient, was abandoned completely. Thus 10 Corps’ advance assisted 13 Corps.

(iii)

At dawn on 13 July a three-man patrol from A Company, 26 Battalion, climbed to the top of Monte Castiglion Maggio and found it unoccupied. The patrol pushed along a high saddle for about a mile to Poggio Cavadenti without meeting any enemy. There was more activity in 25 Battalion’s sector on the slopes of Monte Lignano, which the enemy shelled and mortared. At least two of the houses the battalion was using received direct hits. That night 24 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Hutchens) moved into the line on the western slopes of Monte Camurcina to fill the gap between 25 and 26 Battalions.

The same night 26 Battalion had its first encounter with the enemy since taking over from the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. Two platoons of B Company left about 5 p.m. to spend the night as a standing patrol on Poggio Cavadenti, which had been found unoccupied in the morning. On the summit the leading platoon (10 Platoon) met an enemy patrol of about 10 men. ‘Surprise was mutual but the New Zealanders were the first to

6 Brigade’s attack, 14–16 July 1944

recover. One German was killed and three taken prisoner; two of those who escaped were believed to be wounded. The two platoons dug in along the crest. Later in the night they were subjected to heavy mortar fire which slackened off towards morning. Only one man was hit. ...’33 The prisoners were from a unit of 94 Infantry Division under the command of 305 Infantry Division.

As he felt that the enemy already was beginning to withdraw, Colonel Fountaine ordered C Company, 26 Battalion, to occupy Poggio Spino, about two miles north of Monte Castiglion Maggio. The company set out about 1 a.m. on the 14th and had much trouble

in keeping direction because of the darkness and the nature of the ground. When it had gone about two miles its commander (Major Williams34) ordered his men to rest until daylight, when he would be better able to determine his position. At daybreak, however, it was evident that the company was still some distance from its objective. Williams decided to rest his men until early afternoon.

When C Company approached Point 671, the nearer of the two peaks of Poggio Spino, it came under fire from a farmhouse. A forward observation officer from 6 Field Regiment who was with the company put through a call on his wireless to the guns, which laid a heavy concentration on the enemy-held position. No. 14 Platoon charged in after the concentration, and the enemy retired down the reverse slope. The other two platoons took up position on the other peak (Point 691), which they found deserted. The company was still digging in at nightfall when, following a mortar concentration, the enemy counter-attacked 14 Platoon and forced it back about 80 yards from the farmhouse. The other two platoons stayed on Point 691 and returned the enemy’s fire. The artillery FOO called down another concentration, which fell in the company area. This, or possibly simultaneous enemy fire, caused four casualties, including two men killed. The enemy made no attempt to press home his advantage, and 14 Platoon later reoccupied its position on Point 671 without opposition.

Monte Camurcina, like Poggio Spino, had twin summits: the main peak (Point 846) and Colle de Luca (Point 844), farther west, were joined by a low saddle. C Company, 24 Battalion, had taken over a position from a platoon of 25 Battalion at Podere Rigutinelli, a group of farmhouses less than a mile to the south-west of Colle de Luca. The commander (Second-Lieutenant Crawshaw35) of 15 Platoon, which was occupying this position, had been informed by the commander of the platoon he had relieved that Colle de Luca was either unoccupied or very thinly held. He set out at 5.30 a.m. to discover whether or not it was clear of the enemy. The platoon advanced cautiously with a section on each side of a ridge, scouts out in front, and the third section some way in the rear. One of the scouts was fired on 200 yards from the summit. Crawshaw ordered the two leading sections to make an encircling movement, but they were fired on from newly disclosed positions and sent to ground. The reserve section, going to assist, was also pinned down.

Concluding that the position was too strong for a single platoon

to assault, Crawshaw reported to Company Headquarters and was told to await the arrival of 14 Platoon. Second-Lieutenant Lloyd36 set off with 14 Platoon at 7.30 a.m. and made contact with 15 Platoon, but also came under fire and consequently withdrew down the ridge and reported to Company Headquarters. He was told to consolidate, and while he was doing so, 15 Platoon came down the ridge to the vicinity of his position. Crawshaw’s men had been counter-attacked by the enemy with grenades and automatic weapons and had beaten off the attack, but with the loss of two men killed and five wounded. He then gave orders for the withdrawal, in the course of which three more men were killed and one wounded. The two platoons held their positions below Colle de Luca for the rest of the day.

Some of the opposition encountered by C Company had come from spandau posts on Monte Camurcina, Point 781 (between Monte Camurcina and Monte Lignano) and Poggio Altoviti (to the south-east). C Company estimated there was a company of the enemy on Colle de Luca, and reported three machine guns in the saddle between the twin peaks. Lieutenant-Colonel Hutchens decided that A Company should relieve C Company and capture both peaks of Monte Camurcina. That night A Company advanced about the same time as 25 Battalion made its attack on Monte Lignano.

(iv)

The plan to break through the German defences at Arezzo was for 1 Guards Brigade of 6 British Armoured Division, supported by the tanks of 17/21 Lancers, to capture the high ground at the head of the Chiana valley, south-west of the town, after which 26 Armoured Brigade was to pass through into the Arezzo plain and capture crossings over the Arno River. Concurrently with the first phase of this attack, 6 NZ Infantry Brigade was to clear Monte Lignano and protect the right flank of the Guards Brigade.

The orders for 6 Brigade’s part in the attack stated that 25 Battalion, with one platoon of 2 MG Company and two troops of 17/21 Lancers under command, was to capture Monte Lignano (Point 838) and then Point 650, about 1200 yards north-west of the summit of Lignano. The three New Zealand field regiments, which were located in the Castiglion Fiorentino area, were to support the attack by firing concentrations on the two objectives and other targets. A British medium battery also was to support the attack. The 4.2-inch mortars were to put down timed concentrations along a line east of Monte Lignano and in the area of II Palazzo,

north-east of the feature. After the capture of Monte Lignano 6 Brigade was to reorganise on the high ground running from Poggio Spino to Monte Camurcina and Lignano.

‘It was recognised that the precipitous nature of the country made the task of the artillery very difficult. ...’37 The field regiments were warned that care was to be taken in the computation of correct angles of sight for individual guns during the fire plan.

There was a thunderstorm about midnight. The artillery bombardment on the New Zealand front and in support of the Guards Brigade’s attack on the left opened at 1 a.m. on the 15th, and 25 Battalion’s advance began 40 minutes later. A and C Companies had orders to capture Monte Lignano, and D Company to take Point 783, 500 yards to the north-west, and then clear the ridge running 700 yards westward to Point 650; B Company was to occupy the positions vacated by C Company on the southern slopes of Lignano. C Company moved off first, followed at 10-minute intervals by A and D Companies.

All three companies followed the same route, up a fairly narrow ridge. ‘The terrain was such that the start line could only be reached by scrambling on hands and knees in single file,’ a member of 15 Platoon said later.38 C Company was held up some distance from the summit by shellfire which was believed to be from the supporting artillery, but it deployed and moved on when the barrage lifted at 2 a.m. ‘We ... commenced to move forward up the steep face of the main feature. It was terribly rocky and often it was a case of helping one another over the obstacles. ... First opposition was from a Jerry fox-hole, but we silenced it and pressed on over the rocky terrain, until we encountered the next opposition. Another Jerry strongpoint was left in silence. ... We made the crest on which was a very badly shattered building and we occupied it. ... Prisoners were now being taken. ... We wirelessed back that the position had been taken and to lift the barrage, but it continued to whittle away at what poor protection we had. ...’39

A Company encountered very little opposition on the way to the summit. Two or three spandau posts were silenced. Some mines with trip wires attached caused no casualties because the wires were too slack to explode them. D Company passed through on the way to its more distant objective, where it overcame a more stubborn resistance than the enemy had offered on Lignano.

In case the enemy should counter-attack, Colonel Norman at 4.45 a.m. asked for the tanks of 17/21 Lancers to come up and support the forward companies. The difficult going prevented them

from getting close to the high ground held by the infantry, but they took up a position where they could deal with an enemy attack. By daybreak 25 Battalion was firmly established, with A Company on the summit of Lignano, C a little to the south-east, D holding the line of the ridge from Point 783 to Point 650, and B in reserve on the southern slope of Lignano. The battalion’s casualties on 15 July were 12 dead and 27 wounded; it had killed an estimated 20 of the enemy and taken 19 prisoners, most of whom were from 115 Panzer Grenadier Regiment.

‘The only serious trouble encountered in the attack by 25 Battalion was the shellfire reported on many occasions, and from several sources, as coming from the supporting artillery.’40 A report from the battalion gives 14 instances on 15 July of the shelling of A, C and D Companies by the supporting guns, which caused 16 casualties. On six occasions, from 2.25 a.m. to 3.25 a.m., the shells fell on the summit of Lignano, which was the target for concentrations timed to end at 2 a.m. There should have been no fire after that hour on the peak, but despite the battalion’s attempts to rectify this, the shells continued to fall there.

The guns believed to be responsible were reported to be on a bearing of 155 degrees, which passed through the area occupied by the supporting artillery and, if projected beyond the summit of Monte Lignano, ran through one of the artillery target areas 750 yards north-west of the peak. It appears, therefore, that either the guns firing the concentrations on Monte Lignano failed to lift at 2 a.m. as they should have done, or those that were to have fired concentrations on targets 750 yards beyond Lignano shelled that peak instead. Nevertheless, the bearing cited by 25 Battalion as the source of the shelling, if extended in the opposite direction, passed through the site of a German battery just west of Arezzo. It is quite possible, therefore, that this battery or some other German long-range guns were responsible for at least some if not all of the damaging fire while the attack was in progress. ‘The German artillery had the area well surveyed. ... and [was] easily able to bring down fire on the ground over which the New Zealanders attacked.’41

The Guards Brigade, attacking at the same time as 25 Battalion, met stubborn resistance along the lower north-western slopes of Monte Lignano. A battalion of the Grenadier Guards captured Stoppiace, less than half a mile from Point 650, after a short fight, but a company directed to Point 575 (north-east of Stoppiace) was counter-attacked and forced back 300 yards from the crest, and a

squadron of 17/21 Lancers which went to the company’s assistance at dawn was engaged by anti-tank guns. Later in the morning a battalion of the Coldstream Guards captured Point 575, but a company which reached a hill farther to the north-west in the afternoon was immediately counter-attacked and forced to withdraw. The Coldstream Guards attacked again and recaptured the hill. The enemy made no further attempt to recover it.

(v)

The loss of Monte Lignano, the dominant peak in the Arezzo defence system, meant that the Germans would have to withdraw. Tenth Army reported to Army Group C during the morning of 15 July that ‘we have lost M. Lignano. From there the enemy has a view of Arezzo. Therefore we cannot remain there much longer. ... A counter attack would be very costly and is out of the question. ...’ Field Marshal Kesselring agreed that ‘with M. Lignano in the hands of the enemy we must withdraw.’42 Permission was given for 76 Panzer Corps to make a delaying withdrawal, lasting two days, to the Arno River.

Although the Germans had been compelled to yield Monte Lignano, they still held Monte Camurcina and other points on the high ground in the New Zealand sector. The previous evening (14 July) Hutchens had ordered A Company, 24 Battalion, to relieve C Company on the slopes of Colle de Luca and take first that peak and then the other peak of Camurcina. A Company had moved up during the night and passed through C Company, but had been brought to a halt by machine-gun fire at the locality where C Company had been engaged on the morning of the 14th. A Company attempted no further action on the 15th. Much enemy activity was observed on Colle de Luca in the afternoon and, at the company’s request, the artillery fired on the peak.

Less than a mile south-east of Colle de Luca an eight-man patrol from B Company of 26 Battalion (which was occupying Poggio Cavadenti with two platoons) clashed with Germans on Poggio Altoviti. The patrol set out just before dawn and, on reaching the crest of Altoviti, its leader (Corporal Brick43) and another man tripped over a spandau post. Brick opened fire before the enemy gunners recovered from their surprise. One German was killed and two others wounded and taken prisoner, and although other spandaus in the vicinity began firing, Brick and his men, driving their prisoners before them, raced back across

open ground to Poggio Cavadenti, which they reached without casualties.

Brigadier Burrows decided to stage an attack on the remaining features in the New Zealand sector believed to be still in enemy hands, and gave orders in the afternoon of the 15th for an attack which was to begin at 2 a.m. next day: 26 Battalion on the right was to capture Poggio Altoviti, and 24 Battalion on the left was to take Colle de Luca and the main peak of Monte Camurcina. The 23rd Battalion, having passed temporarily to 6 Brigade’s command, was to be in reserve.

The three field regiments were to support this attack with a series of concentrations on the objectives and other targets. The 4.2-inch mortars also were to give support by firing on Point 812 (north of Colle de Luca) and at dawn were to carry out observed bombardments of the valleys north of the objectives.

The artillery opened fire on Poggio Altoviti at the appointed time (2 a.m.). B Company of 26 Battalion, led by 7 Platoon (attached from A Company), advanced to the peak and found it deserted. Soon afterwards the company came under what was believed to be 25-pounder fire. ‘Frantic messages were relayed back to the gunners and the firing soon ceased, but not before two men had been killed and two wounded.’44 It is again possible that the German artillery, which was well placed to fire on this peak, may have been responsible. The enemy could have judged from the New Zealand shelling how the attack was progressing and where to place his fire to best advantage.

Before the bombardment began A Company, 24 Battalion, withdrew 400 yards from Colle de Luca, and half an hour after the guns opened fire, moved forward again unopposed. D Company passed through and found Camurcina deserted. The two companies were ordered to send out patrols at daybreak to search for any enemy who might be lying low. Supplies and equipment, including machine guns, were taken up to Monte Camurcina by a mule team. A patrol from A Company made contact with 25 Battalion on Monte Lignano, and also took two prisoners. Mines and several enemy dead were found.

(vi)

While 6 Brigade was driving the enemy off Monte Lignano and the adjacent peaks, a column consisting of B Squadron of Divisional Cavalry, two troops of C Squadron, 18 Armoured Regiment, and D Company of 26 Battalion was making its way through the hills

to the south-east, along a narrow winding road which linked Castiglion Fiorentino on Route 71 with Palazzo del Pero on Route 73 five miles from Arezzo.

The column made slow progress on 14 July, being delayed at several places by mines and demolitions, and was halted in the afternoon by a large crater at the junction of a side road which led round the northern face of Poggio Spino (the peak occupied by C Company, 26 Battalion, that afternoon), about two miles from Palazzo del Pero. Enemy shell and mortar fire prevented the sappers of 8 Field Company from repairing the road, and as the shelling had not stopped next morning (the 15th), it was decided to bulldoze a bypass, which was completed before midday. An armoured car patrol then advanced without opposition to the road junction at Palazzo del Pero, where it found more mines and demolitions and came under fire from enemy guns. The tanks, which also moved to Palazzo del Pero, engaged with harassing fire small distant parties of the enemy, who appeared to be pulling back through the hills.

Meanwhile troops of 4 Indian Division, of 10 Corps, which planned to cross Route 73 east of Arezzo and capture the Alpe di Poti, the high ground dominating the east and north-east of the town, came through the mountains south-east of Palazzo del Pero, and early on 16 July – when C Squadron’s tanks had just started off along Route 73 – the New Zealanders were recalled from what was now 10 Corps’ sphere of operations.

(vii)

The enemy had broken contact on the New Zealand front; he had also gone from 6 Armoured Division’s sector, on the left, where a battalion of the Welsh Guards moved unopposed on to the Agazzi hills, across the highway leading to Arezzo. The 26th Armoured Brigade drove through the gap in the hills, occupied the town and crossed the Arno.

The occupation of Monte Camurcina and Poggio Altoviti had ended the New Zealand Division’s part in the battle. The Division went into reserve, and orders were given for the withdrawal of 6 Brigade. Equipment was loaded on mules and the various companies came down from the high ground to the road, where they were picked up by the transport which took them back to the brigade’s B echelon area, west of Cortona in the Chiana valley.

The New Zealand casualties in the battle for Arezzo totalled 116, including 37 killed or died of wounds; 66 of these (22 killed and 44 wounded) were incurred by 25 Battalion.

Immediately after 6 Brigade’s return General Freyberg held a conference of formation and unit commanders to announce the New Zealand Government’s policy on furlough. Already most of the men who had left New Zealand with the First, Second and Third Echelons had been granted furlough; the Ruapehu draft of over 6000 had left Egypt for New Zealand in June 1943, and the Wakatipu draft of over 2500 in January 1944. But the 4th Reinforcements, who included men who had fought in Greece, Crete and North Africa, were still serving with the 2 NZEF.

The GOC issued a special order on 17 July stating that replacements were being sent from New Zealand to relieve the 4th Reinforcements, a proportion of whom would be withdrawn forthwith and the remainder later in the year after the arrival of the replacements. The first group, numbering 1500, was to include all the married men of the 4th Reinforcements and a proportion of the single men selected by ballot; and also officers of the first three echelons who had not yet had furlough (except a few in key positions) but no officers of the 4th Reinforcements.

Celebration parties for those who were going – and to drown the sorrows of those who were not – were staged before the departure of the Taupo draft on 20 July. Several weeks later, when the GOC found it necessary to draw the attention of formation commanders to breaches of discipline, he listed as one example of ‘unrestricted consumption of intoxicating liquor’ the occasion when ‘troops from certain units turned up at the parade of 4th Reinforcements in a hopelessly drunken condition, and had to be kept off the parade ground. Numerous men of this draft were in possession of large quantities of liquor which was taken on the trucks with them.’