Chapter 4: The Advance to Florence

I: A Change in Plan

(i)

THE capture of Arezzo by 13 Corps on 16 July was followed by other successes: 2 Polish Corps broke through to Ancona on the Adriatic coast on the 18th and 4 United States Corps entered Leghorn on the Ligurian coast next day. These advances gave the Allied armies possession of two vital ports of supply – both of which had to be cleared of extensive demolitions before they could be used – and in Arezzo an administrative base for the planned offensive against the Gothic Line. The next objective was Florence, which was wanted as an operational base for such an offensive.

Thirteenth Corps’ sector offered the easiest terrain for an advance to Florence – north-westwards from Arezzo down the valley of the Arno River. This valley, however, was dominated from the east by the rugged and almost unroaded Pratomagno massif and from the west by the comparatively gentle ridges of the Monti del Chianti. The corps advanced on a front of three divisions, with 6 British Armoured Division in the Arno valley, 6 South African Armoured Division on the western side of the Chianti mountains, and 4 British Infantry Division keeping contact between them. It soon became apparent that the enemy was determined to resist strongly in the Arno valley, where he had concentrated some of his best troops.

The widening of Eighth Army’s front, when the French Expeditionary Corps of Fifth Army departed to prepare for the anvil expedition, gave another possible approach to Florence: west of the Chianti mountains. Thirteenth Corps, extending westwards, took over the French Corps’ sector on Fifth Army’s right flank, astride Route 2, which led northwards from Siena through Poggibonsi

(captured by the French on 14 July) and San Casciano to the city. It was a region of rolling hills and many secondary roads and tracks, and according to Intelligence reports and the experiences of the French, was not as strongly defended as the Arno valley.

To take advantage of the expected lighter resistance in this sector, therefore, General Kirkman moved the weight of 13 Corps’ attack westward. On the corps’ right flank 6 Armoured Division was to continue its thrust down the eastern side of the Arno valley and 4 Division was to push down the western side of the lower slopes of the Chianti mountains; these two divisions were to contain the enemy facing them, maintain constant pressure and be prepared to take advantage of any opportunities. The 6th South African Armoured Division, which earlier had the subsidiary role of making down the valley of the River Greve (a tributary of the Arno), an outflanking move to assist the attack down the Arno, was now to take part in the major assault, with the Arno west of Florence for its objective. After the New Zealand Division and 8 Indian Division had relieved the French Expeditionary Corps, the New Zealanders were to share with the South Africans in this assault, and the Indians were to conform with the advance and cover the left flank.

The New Zealand Division was to relieve 2 Moroccan Division and pass through the leading troops as early as possible after dawn on 22 July; it was intended to thrust northwards from Castellina in Chianti (east of Poggibonsi), cut across Route 2 by San Casciano and occupy the Arno crossings at Signa, six or seven miles west of Florence. The Division’s sector was only about three miles wide; it led north-north-westwards and included the secondary road running in that direction from Castellina, a short stretch of Route 2 and a network of minor roads and tracks beyond San Casciano.

In instructions issued on 21 July to the five divisions of 13 Corps General Kirkman directed that every effort should be made, with the help of Italian partisans where available, to secure bridges intact over the Arno, form bridgeheads north of the river, and even take advantage of any opportunity given by the enemy’s weaknesses or disorganisation to penetrate the Gothic Line. He thought it more likely, however, that the enemy would withdraw in orderly bounds and be found firmly deployed in prepared defences in the Gothic Line. The corps commander also said that it was not his intention to become involved in serious street fighting in Florence, but to bypass the city if necessary. Florence was not to be shelled without sanction from Corps Headquarters.

(ii)

General Kirkman informed General Freyberg in the afternoon of 20 July that the New Zealand Division would be called on for the assault on Florence. Orders were given and preparations made for the move of the Division’s 4855 vehicles to Castellina, a distance of about 60 miles. The Division was divided into 14 convoys which, with the exception of 150 tracked vehicles of 4 Armoured Brigade, went by a route from Castiglion Fiorentino past Siena to Castellina; the tracked vehicles’ route was from Castiglione del Lago past Sinalunga and Siena. The first convoys left on 21 July and the last two days later; they completed the journey with few mishaps. The usual security precautions were taken of not displaying New Zealand badges, titles and fernleaf signs, and wireless silence was enforced.

It was mid-summer. During the journey a man who had served in North Africa declared that ‘never before in all my life have I travelled over such a dusty road. The endless stream of vehicles had ground the surface into a light feathery dust which was six inches deep in places. There was little wind, and although the road wound up and down over broken hills and was only visible at scattered points, its whole length could be traced by the pall of dust hanging over it. Vehicles and occupants were covered with a chalky grey powder which gave them a ghastly unnatural appearance. Occasionally we had to drop to crawling speed because the swirling clouds limited visibility to the end of the bonnet. The route took us through the foothills of the Chianti mountains which were thickly wooded at first, later becoming barren and wind eroded as we made towards Siena.’ The convoys drove round the high, massive brick wall of the town, ‘but over the top we could see several domes and spires and some large buildings. A little further on we turned off the main route ... down a side road to our new bivvy area, on the estate of some Italian count. ...

‘We have the trucks parked along a line of white mulberries bordering a lucerne paddock in the characteristic setting of wheat and maize patches crisscrossed by grapevines supported on topped maples. ... A very striking thousand yard avenue of upright Italian cypresses runs from the main gates up to the residence. ... The long line of sombre dark green spires forms a striking contrast with the yellow brown background of rolling hills. The final two hundred yards leading to the house is flanked on either side by groves of fine old ashes, beeches and maritime pines. ... The place has been very pretty but is now in a state of neglect.’1

(iii)

Divisional Headquarters issued an operation order in the evening of the 21st which said the intention was to advance and capture crossings over the River Arno at Signa. Fifth Brigade was to relieve 2 Moroccan Division and then advance against the enemy as early as possible next day. The remainder of the Division was to remain south of Castellina on three hours’ notice until called forward. Three Royal Artillery regiments came under the Division’s command – 70 and 75 Medium Regiments and 142 Army Field Regiment2 (self-propelled) – and in support was B Flight of 655 Air Observation Post Squadron. The Division also took over temporarily some armoured and artillery units which had been supporting 2 Moroccan Division.

On the night of 21–22 July 5 Brigade relieved two battalions of 2 Moroccan Division five or six miles north-west of Castellina, with 23 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas3) on the right at San Donato in Poggio and 28 (Maori) Battalion (Lieutenant- Colonel Young) on the left between the Castellina – San Donato road and Route 2. Each battalion was supported by two platoons of medium tanks and one of light tanks from 757 US Tank Battalion; in addition, 23 Battalion had two troops of A Squadron, Divisional Cavalry, and a platoon of 7 Field Company under command, and 28 Battalion had one troop of A Squadron, Divisional Cavalry, a platoon of 7 Field Company and 5 Brigade Heavy Mortar Platoon. The 5th Field Regiment was deployed two and a half miles north-west of Castellina.

The 23rd Battalion completed the relief of 2 Battalion, 8 Moroccan Infantry Regiment, before midnight and sent out patrols, one of which met opposition on a ridge (Point 337) a mile and a half to the north along the road to Sambuca. The Maori Battalion, whose sector was farther from the road, took until dawn to complete the relief of 2 Battalion, 5 Moroccan Infantry Regiment.

The codeword (Skegness) for the start of 5 Brigade’s advance was circulated by Divisional Headquarters by a signal timed 1.30 p.m. on 22 July; this allowed units operationally engaged to use their wireless sets, and also permitted the display again of New Zealand titles, badges and fernleaf signs.

(iv)

When the New Zealand Division went into the line for the assault on Florence, the Polish Corps, in the Adriatic coastal sector, had crossed the Esino River, between Ancona and Senigallia, and was steadily pushing the enemy back towards the main defences of the Gothic Line, the eastern flank of which rested on Pesaro. In 10 Corps’ mountainous sector armoured car patrols were operating on a wide front east of 10 Indian Division, which was working its way northward along the Tiber valley, and 4 Indian Division was in the rugged country north-east of Arezzo.

On 13 Corps’ right flank 6 British Armoured Division, advancing in a north-westerly direction from Arezzo to clear the eastern side of the Arno valley, had not progressed far beyond the southern end of the Pratomagno massif, and 4 British Division, on a narrow front extending into the foothills of the Monti del Chianti, was less than half-way along Route 69 (the road from Arezzo to Florence).4 Farther west 6 South African Armoured Division was clearing the defences on the main features of the Monti del Chianti to permit an advance along a secondary road to Greve, south of Florence. Thirteenth Corps’ front continued westward through the New Zealand Division’s sector to where 8 Indian Division relieved 4 Moroccan Mountain Division, which had reached a line stretching north-westwards along the Elsa River to Castelfiorentino. The command of the part of the front taken over by the New Zealand and Indian divisions passed from the French Expeditionary Corps of Fifth Army to 13 Corps of Eighth Army at midnight on 22–23 July.

Fifth Army, reduced to a front of four divisions to release troops for the landing in southern France, penetrated over Route 67 (the road from Florence to Pisa and Leghorn), entered the southern part of Pisa on 23 July, and began to regroup along the Arno.

(v)

The enemy held a line across the peninsula south of the Gothic Line defences, with Fourteenth Army (comprising 75 Corps, 14 Panzer Corps and 1 Parachute Corps) on the right (west) and Tenth Army (76 Panzer Corps and 51 Mountain Corps) on the left. Seventy-fifth Corps disposed one division around the mouth of the Arno River and on the Ligurian coast to the north, and another in the Pisa area; 14 Panzer Corps was along the Arno to the confluence with its tributary, the Elsa, with two divisions

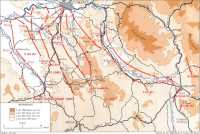

The Advance to Florence, 14 July – 4 August 1944

forward and one in reserve; from Castelfiorentino on the Elsa eastwards across the hills south of Florence to the Monti del Chianti – the part of the front to which the New Zealand and Indian divisions were transferred, alongside the South Africans – was 1 Parachute Corps with three divisions, 29 Panzer Grenadier on the right, 4 Parachute in the centre and 356 Infantry on the left.

East of the boundary between the two German armies, 76 Panzer Corps held the line from the Monti del Chianti across the Arno valley between Florence and Arezzo with seven divisions, one of which was in the process of relieving the Hermann Goering Division, destined to leave the Italian front, and another (1 Parachute Division) was to be withdrawn to Rimini on the Adriatic coast. The line from the Tiber valley through the mountains to the coast was held by 51 Mountain Corps with four divisions.

The enemy had few reserves behind the front line he could call upon if necessary. North of Pisa two German Air Force divisions were being converted into one formation. Spezia, on the Ligurian coast, was garrisoned by a fortress brigade; the coast east and west of Genoa was covered by a German division, and another was guarding the Franco-Italian frontier with the Italian Army Liguria. Tenth Army had one division in reserve at Bologna. A Turcoman division of doubtful reliability was watching the Adriatic coast south of Ravenna, and 1 Parachute Division, as it was withdrawn from the Arno valley, went into position south of Rimini, in rear of the Adriatic flank of the Gothic Line. The German High Command was still apprehensive of seaborne landings behind the front.

Field Marshal Kesselring knew from experience that the mobility of the Allied armies enabled them to attack with little warning at widely separated parts of the front. His own Army Group C, on the other hand, was handicapped by its lack of transport and the continual interruption of communications by the almost unopposed Allied bombing, and therefore had difficulty in transferring formations rapidly from one sector to another. To guard against a breakthrough which might cut in behind and encircle part of his forces, he had to cover as wide a front as possible and fall back evenly across that front. As he could not expect to receive sufficient reinforcements for use as a mobile reserve or as a counter-attack force, his tactics could be only a step-by-step withdrawal under pressure to keep his line intact.

Hitler had given orders to hold the line south of Florence as long as possible. The placing of Tenth Army’s main strength across the Arno valley south-east of the city had influenced 13 British Corps in its decision to change its line of assault to a sector farther

west. Fourteenth Army intended to hold the Heinrich-Paula5 line, which ran along the lower Arno River from the coast to Montelupo and then eastwards through the hills about five miles south of Florence. In Army Group’s opinion this line was too close to the city, and orders were given, therefore, that a line farther south should be reconnoitred and prepared.

II: The Pesa Valley

(i)

The New Zealand Division was now in the Chianti country, famous for its wine, a closely settled region of undulating ridges, slopes and gullies, where thickly wooded land alternated with olive groves, vineyards, crops of wheat and cereals, and where innumerable stone-built farmhouses and hamlets were interspersed with handsome villas. Many of these buildings were to become strongpoints for defence and targets for attack.

This became known as the ‘Tiger country’ because of the many German Tiger (Mark VI) 60-ton tanks encountered there. The Sherman was considered no match for the Tiger.6 ‘From the moment the Tiger appeared it became a kind of bogey, and the air was full of rumours of more and more Tigers lying in wait just ahead; just as in the desert every German gun was an “eighty-eight”, so here every tracked vehicle heard over in German territory was a Tiger. The natural result was that, quite suddenly, the New Zealand tanks became more cautious than they had ever been before. ... The high mutual regard of New Zealand tanks and infantry was in danger.’7 The Chianti country appeared to offer no advantages for the attacking armour: it was intersected by shallow watercourses and narrow roads which could be obstructed by mines and demolitions. Much of the advance would have to be made across country, where the tanks would have to grope almost blindly among the trees and vines.

(ii)

Fifth Infantry Brigade was to start the New Zealand Division’s advance towards the Arno. The intention was that on the right 23 Battalion was to follow the axis of the secondary road leading north-west from San Donato in Poggio into Route 2, and from Sambuca was to continue on the eastern side of the Pesa River; on the left 28 (Maori) Battalion was to take the side road which turned off westward just south of San Donato and swung north-westward to join Route 2 by Tavarnelle in Val di Pesa, and was to follow Route 2 as far as Strada and then turn left on to the side road which ran north-westwards along the west of the Pesa valley.

The first objective (codename BUFFALO) was about three miles north of San Donato, the second (MONTREAL) another mile and a half, and the third (QUEBEC) a further mile and a half.8 These were phase lines rather than objectives; they were intended to indicate the rate and extent of the advance. Both battalions were to keep in contact with the enemy and force him to continue withdrawing; until they met a strong defence needing a set-piece attack, they were to conduct their own advances, with Brigade Headquarters co-ordinating times and objectives. Until relieved by 18 NZ Armoured Regiment, the tanks of 757 US Tank Battalion were to stay in support of 23 and 28 Battalions. Provision was made for the field and medium artillery to move forward as required in support.

At daybreak on the 22nd troops of 23 Battalion prepared to advance against the enemy posts identified by patrols the previous night, and the artillery was asked to fire on Point 337, a mile and a half beyond San Donato, and to harass all likely defences on the route to Sambuca. The 5th Field Regiment began firing at 6.20 a.m.

C Company pushed westward along a ridge towards Point 357, which a platoon quickly occupied, and took a few prisoners from 4 Parachute Division. B Company had a more difficult task. About a mile north of San Donato a side road led off to the north-west towards Morocco and Tavarnelle, and near the road fork the settlement of San Martino a Cozzi would have to be occupied before the battalion could advance up either the road to Sambuca or the road to Morocco. Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas therefore ordered B Company to capture San Martino.

Attacking without tank support, B Company’s men were caught at close range by devastating fire and had to retire when their

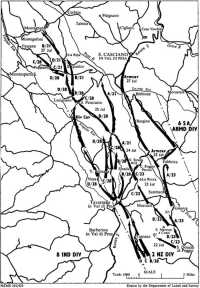

5 Brigade’s advance, 22–27 July 1944

ammunition ran low. About midday the company commander (Major Worsnop9) arranged a stronger assault, supported by artillery and mortar fire, and with covering small-arms fire from Divisional

Cavalry armoured cars. San Martino was captured, but by this time B Company’s casualties were nearly 30 (including five men taken prisoner).

This action was considered invaluable in permitting the later advances on 23 Battalion’s front, but it had not been intended that the infantry should attack without tank support.10 Several American Sherman tanks were in harbour close to San Donato, but their commander had been unwilling to become involved in 23 Battalion’s attack as he was waiting for the New Zealand tanks to take over. He said his instructions had been ‘not to lose a tank or risk one.’11 Later, however, the Americans ignored these instructions.

While B Company was dealing with San Martino, A Company did not go beyond the road fork. Its objectives were Point 337 and the settlement of Ginestra, farther along the road to Sambuca. A Company, also without tank support, captured Point 337, but was counter-attacked and forced to withdraw. Thomas ordered the company commander (Major Hoseit12) to regain the point. Some of the American tanks, a troop of New Zealand tanks and two troops of A Squadron, Divisional Cavalry, went forward to assist, and 5 Field Regiment gave supporting fire. By dusk A Company had retaken Point 337 and occupied some of the houses at Ginestra.

When D Company, accompanied by two troops of A Squadron, 18 Armoured Regiment, started an advance to Morocco, the leading troop of tanks, either by mistake or through receiving a request to help A Company, continued along the Sambuca road instead of turning on to the Morocco road and took part in the counter-attack which regained Point 337. These tanks then wheeled left across country to join the other troop of tanks with D Company on the Morocco road.

D Company and the tanks spread across the fields bordering the Morocco road and made excellent progress. ‘The country was gently undulating and we went sweeping forward beneath the scattered olive trees, with farmhouses showing up here and there at the end of lanes running in from the main road. ... When a house, appearing through the trees, looked to house the enemy, the tanks blazed away with their 75s as they advanced. The enemy was on the run. Without the armour I don’t expect we should have got very far,’ says one of the platoon commanders.13

Fire was exchanged with the enemy in Morocco, and on request 5 Field Regiment laid down a ‘murder’14 on the centres of resistance.

The infantry and tanks closed in on the village and, although some Germans were seen in retreat, the houses had to be cleared one by one. A Sherman tank was set alight by a tank or self-propelled gun which subsequently managed to withdraw. D Company collected about 60 prisoners, but owing to a misunderstanding, one of the supporting tanks opened fire on the house where the prisoners were held under guard, and most of them escaped in the confusion.

When Thomas heard of D Company’s success, he changed the plan he had made for C Company with tanks and engineers to attack up the Sambuca road through A Company next morning, and ordered C with all available support to go immediately to Morocco. C Company was relieved at Point 357 by a platoon from 28 Battalion and, travelling on seven of A Squadron’s tanks and other vehicles, set off to join D Company. The combined force advanced to a road junction a short way beyond Morocco and laagered overnight. The engineers cleared the road through Morocco, which had been partially blocked by demolitions.

Meanwhile, during the morning of 22 July, 28 (Maori) Battalion concentrated on the road which led westwards from just south of San Donato and then north-westwards towards Tavarnelle. In the afternoon patrols, reconnoitring the ground over which the battalion was to advance, exchanged fire with parties of the enemy, took a few prisoners, and reported that the enemy was occupying the village of Tignano, less than two miles from Tavarnelle, but apparently not in any strength. Before the advance began 5 Field Regiment laid down fire on positions where the enemy had been observed.

The Maoris set off shortly after 7 p.m. with B Company covering the right flank east of the road, C in the centre, D west of the road, and A in reserve. Half of B Squadron, 18 Armoured Regiment, joined C Company; the other half was in reserve. Machine-gun and mortar fire was met on rising ground leading to Tignano, but under cover of fire from the tanks and mortars, C Company converged on the village, overcame the opposition and took a few more prisoners. B and D Companies passed on each side of Tignano and converged on Spicciano, farther along the road, where they stopped after dislodging small groups of the enemy. The sappers of 7 Field Company cleared a passage for the tanks past demolitions and mines.

(iii)

The Germans had observed on 21 July that the Allies were bringing up reinforcements on 1 Parachute Corps’ front, particularly in the area south of Tavarnelle, and next day that the Allied

preparations had increased still further. Guns and many vehicles could be seen, especially in the area east of the Poggibonsi-Florence road. Statements by prisoners of war indicated that a new formation, ‘presumably 2 NZ Div’,15 had come into the line. Fourteenth Army ordered 1 Parachute Corps to hold the Nora Line (Strada–Fabbrica) until at least the evening of 23 July.

On the 22nd 4 Parachute Division extended its front eastwards by taking over part of 356 Division’s sector, an alteration which brought the New Zealand Division’s line of assault exclusively against the parachute division. Fourteenth Army reports describe the attacks on 1 Parachute Corps’ front, including those south and south-east of Tavarnelle, where ‘after fierce fighting our battle outposts withdrew to the FDLs.’16 The 23rd Battalion of the New Zealand Division was identified by the capture of five men from B Company.

(iv)

C Company of 23 Battalion, accompanied by half of A Squadron, 18 Regiment, left the road junction near Morocco at 4.30 a.m. on 23 July and within an hour and a half had occupied the hamlet of La Rocca. Beyond La Rocca the enemy withdrew behind demolitions, one of which he blew little more than 100 yards in front of the leading tank. C Company crossed Route 2 to the village of Strada, on a secondary road leading to the north-west. There the defence included spandau, mortar and ofenrohr fire, but the tanks ‘hammered the buildings with all their weapons while the infantry moved in, and Jerry fled, abandoning one of his bazookas.’17 C Company was in possession of Strada by 7.15 a.m., and another group of buildings called Case Poggio Petroio about midday.

The artillery engaged a German tank reported at Point 322, by Villa Strada, a large house (known to the New Zealanders as the Castle) not far to the north of Strada. One of A Squadron’s tanks was hit by an anti-tank shell from somewhere near Villa Strada, and burst into flames before the crew could get clear. Early in the afternoon C Company was directed on Point 322, but was forced to fall back. So intense was the fire from this locality that it was decided not to renew the attack that afternoon.

The Maori Battalion resumed the advance from the Tignano area at 5 a.m. on the 23rd and in a little over two hours entered Tavarnelle without opposition. It was then learnt that 23 Battalion, by attacking Strada, had crossed 28 Battalion’s axis of advance (Route 2). Brigadier Stewart therefore directed the Maori Battalion to take a road north of Tavarnelle instead of Route 2, with Villa Bonazza as its immediate objective. After some delay caused by machine-gun fire and mines, C Company moved up this road, followed by half of B Squadron, 18 Regiment, with B Company keeping level on the right. Both companies were fired on by guns and mortars located mostly in the Villa Strada area, where tanks were also seen.

From the direction of Villa Bonazza ‘fast tank shells came whistling down the road. ... [B Squadron’s tanks] began to shoot up the villa and its grounds, but this brought on a savage reaction from Jerry, and a Tiger tank beside a little cemetery on the right flank hit and burnt two Shermans in quick succession.’18 A third troop of B Squadron came up to join in the battle with the Tiger, which left the cemetery and, while heading across a gully towards Route 2, was damaged beyond repair and finally blown up by its crew. This was the first Tiger tank claimed by the New Zealand Shermans.

During the day 18 Regiment’s padre (Captain Gourdie19) pulled the men out of two burning tanks, and repeatedly exposed himself to shell and machine-gun fire to take carrier loads of wounded men back to the RAP.

On 28 Battalion’s left flank D Company advanced up the road through the village of Noce, which was across a gully from Villa Bonazza. The hostile fire increased beyond Noce, and by 6 p.m. D Company, as well as B and C, had come to a halt. Later, however, the Maoris charged Villa Bonazza. Sergeant Patrick,20 of D Company, says ‘a spandau was firing from one of the windows and there was a fair amount of activity in the trees. ... We fixed bayonets and went down the gully and up the other side pretty well worked up too.’ But the enemy must have seen the Maoris coming, ‘for they left their defences and scampered back to the building. The trees seemed alive with running men, and the yelling of the Maoris added to the din created by the shouting of the Jerries. We killed a few but the rest disappeared and we presumed they had entered the casa. We searched but found no one

in it. It was a tremendous building and I remember a beautiful piano. ...’21

(v)

Brigadier Stewart gave 23 Battalion orders in the morning of 23 July to occupy Sambuca, but not to continue beyond the bound MONTREAL (the junction of the Sambuca road and Route 2). Also, Divisional Cavalry’s armoured cars were to establish contact with 6 South African Division’s troops on the right flank. Lieutenant- Colonel Thomas therefore instructed A Company to continue to Sambuca and Fabbrica with supporting arms and an additional troop of A Squadron of Divisional Cavalry under command.

This force came under increasing shell and mortar fire as it approached the western bank of the Pesa; it found that the bridge had been destroyed at Sambuca, but took the village, crossed the river, and continued towards Fabbrica, a village on a hillside more than a mile to the north. The impression was gained from Italians that the enemy had left Fabbrica,22 and this seemed to be confirmed when no fire came from the village.

The vehicles were held up at a demolition where the road crossed a stream, but about 7.30 p.m. the infantry continued to the foot of the hill on which Fabbrica stood, where they were within easy range of the buildings overlooking them. At this point mortars and machine guns opened fire on the men in the open, who went to ground, and artillery fire was directed on the road around Company Headquarters. A request was sent back for a stonk on Fabbrica, but some of the artillery fire fell short. The house in which Company Headquarters had been set up received a direct hit by an enemy shell, which killed Major Hoseit and wounded several of his men. Orders were given for the company to withdraw, which it did with the assistance of covering fire from the Staghounds.

(vi)

Field Marshal Kesselring expressed the opinion to General Joachim Lemelsen23 on 23 July that a major Allied attack was imminent, with its main weight on Fourteenth Army’s left flank and possibly to a less extent on Tenth Army’s right flank. It appeared to him

that there was evidence that the Allies had decided against a landing in southern France so as to add all possible weight to the attack in Italy, perhaps supported by a landing on the Ligurian coast or in the Adriatic. The immediate objective would be Florence.

Late on 23 July Fourteenth Army issued orders that 1 Parachute Corps was to delay the Allies as long as possible after they had launched their expected attack on Florence. To enable the Paula Line south of the city to be prepared for a prolonged defence, 1 Parachute Corps was to hold another line (the Olga Line) several miles farther south until the evening of 25 July at the earliest.

Fourteenth Army’s evening report on 23 July states that the New Zealand and South African divisions had attacked the centre and left of 1 Parachute Corps in strength. ‘Very hard fighting took place, in which 4 Para Div particularly distinguished itself. Both sides lost heavily. All attacks were beaten off, and a decisive success was gained. ...’ In a discussion with Lemelsen, General Alfred Schlemm (commander of 1 Parachute Corps) reported that ‘Terrible fighting was in progress on 4 Para Div’s front; the division had New Zealanders opposite it.’24

(vii)

On the morning of 23 July General Freyberg was so satisfied with the way the advance was developing that he anticipated a speedy collapse of the German defences. He therefore decided not to bring 6 Brigade into the attack at that stage, but instead to send Divisional Cavalry through 5 Brigade when it had reached the bound QUEBEC (about 12 miles in a straight line from Florence) with the intention of driving to the Arno to try to save some of the bridges. Later in the day the reports of the opposition on 5 Brigade’s front indicated that there was no immediate prospect of Divisional Cavalry accomplishing this task.

Nevertheless the GOC continued to be hopeful of the enemy’s early withdrawal behind the Arno, and he wished to be fully prepared to follow up such a withdrawal as closely as possible. He considered bringing up 22 (Motor) Battalion and an armoured regiment with Headquarters 4 Armoured Brigade on the right, but it was felt that until 5 Brigade got further ahead there would not be enough room.

It could be seen that the right flank would present many obstacles. Route 2, being a main road, was likely to be well covered with fire; the many ditches and streams which passed under it to drain into the Pesa River gave the enemy ample scope for

demolitions, and the river itself would hinder lateral communications across the front. On the other hand, the road running to the north-west from Strada, mostly along the higher ground of the divide between the Pesa and the Virginio stream, might give greater opportunity for deployment and outflanking movements. It was decided, therefore, to exploit 23 Battalion’s success.

In the evening of 23 July Stewart arranged with Thomas that 23 Battalion’s D Company at Strada should send a patrol at 3 a.m. to Point 322 (near Villa Strada), where the enemy had resisted most strongly, to discover if he was still there. If he appeared to be thinning out, D Company was to stage an attack. If not, 21 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Thodey25) was to pass through the 23rd with fresh tanks and take up the advance.

D Company’s patrol reported that enemy troops were still around Point 322 but vehicles and tanks had been heard withdrawing. Thomas called for artillery fire on the objective, and about 6 a.m. sent D Company forward. The infantry infiltrated across country under cover of a heavy mist, and tanks of A Squadron, 18 Armoured Regiment, followed along the road. When the mist lifted the company came under machine-gun fire. The tanks encountered demolitions, and two were blown up on mines. Mortar and artillery fire swept the road. The attack was called off, and arrangements were put in hand for 21 Battalion to relieve the 23rd, which was to go back to the vicinity of Morocco to rest. This relief was completed late in the evening of the 24th.26

Meanwhile a patrol from B Company, 23 Battalion, reconnoitred along Route 2 from Strada to the Pesa River and found that the highway had been much damaged by demolitions. As might be expected, the bridge over the river had been blown.

(viii)

The Maori Battalion, having gained the bound MONTREAL, resumed the advance north of Villa Bonazza on the morning of 24 July, with C Company on the right, D on the left and B in reserve, and with two troops of B Squadron, 18 Regiment, in close support. A platoon from A Company (which was at Tavarnelle), two Staghounds and some Bren carriers worked along the road north of Noce to protect the left flank, where 8 Indian Division had not yet drawn level.

The Maori Battalion made better progress on the left than on

the right. Early in the afternoon, when Brigadier Stewart learnt that D Company had reached the line of the bound QUEBEC, he instructed Lieutenant-Colonel Young to halt his men and wait until 21 Battalion was ready to support a further advance on the right. D Company was about two miles beyond Villa Bonazza, but C Company was well back, and B farther back still. The Shermans with C Company clashed with a Panther,27 ‘which blazed defiantly away from the Strada road and effectively scotched the advance on the Maoris’ right.’28 But the enemy, after some ‘nasty persistent shellfire’, withdrew during the night, and C Company advanced before dawn on the 25th to secure the crossroads on the Strada – San Pancrazio road about two miles from Strada. The Maori Battalion then took the route north-westward towards San Pancrazio.

A Company of 21 Battalion, having relieved D Company, 23 Battalion, after dusk on the 24th, set off along the road from Strada, supported by two troops of C Squadron, 18 Regiment (which had replaced A Squadron), and with C Company following in a reserve role. The leading infantry was reported on the line of the bound QUEBEC about 2 a.m. As 28 Battalion was cutting in ahead on the Strada – San Pancrazio road, 21 Battalion was directed on to the road leading off to the north from the crossroads secured by the Maoris. A Company followed this road down a long spur towards the Pesa River. Mines and demolitions had to be cleared to allow the tanks through, and in the afternoon the company was brought to a halt by enemy in buildings near the end of the ridge, from which the road descended to a bridge, already demolished, on the Pesa. Route 2, on the other side of the river, turned at right angles not far from the wrecked bridge to climb a spur to San Casciano.

A Company laid on an attack which at first went well, but as the infantry and tanks approached the river they came under mortar and artillery fire, mostly from the San Casciano spur. A Sherman was knocked out. The infantry took up positions along the road leading to the demolished bridge, and stayed there next day.

The Maori Battalion continued its advance north-westward on the road along the ridge between the Pesa and the Virginio on the morning of 25 July. D Company and tanks of B Squadron, 18 Regiment, were held up about midday at San Pancrazio by a mined demolition covered by anti-tank fire. Staghounds of A Squadron, Divisional Cavalry, which had joined the battalion, and others of B Squadron, which had taken over the task of protecting the

left flank by driving along the road from Noce to San Pancrazio, assisted in clearing the village, where 13 prisoners were collected. Beyond San Pancrazio many mines, real and dummy, were lifted, and D Company took 23 prisoners in a sharp fight near Lucignano.

(ix)

Meanwhile changes took place on the Division’s right flank, east of the Pesa River. A Company of 23 Battalion, after being repulsed at Fabbrica, was replaced on the night of 23–24 July by B Company, 21 Battalion, which in turn was withdrawn next night when 21 Battalion relieved the 23rd at Strada. The front east of the Pesa was then taken over by a composite force called Armcav, under the command of Major H. A. Robinson29 and comprising A Squadron of 19 Regiment, C Squadron of Divisional Cavalry, 2 Company and a section of carriers from 22 (Motor) Battalion, a troop of M10s, detachments of engineers, machine-gunners and signalmen, a bridge-layer tank and a bulldozer.

Armcav, under 5 Brigade’s command, was to follow up the enemy’s withdrawal on Route 2 and maintain contact with the South Africans on the right. It was hoped that, with 5 Brigade advancing fast on the western side of the Pesa and the South Africans pressing forward on the east, the enemy holding across Route 2 would fall back under the threat of encirclement.

Early on the morning of 25 July Armcav occupied a deserted Fabbrica and reached the road junction near the Route 2 crossing of the Pesa without opposition. While the main part of Armcav continued northward along Route 2, a detachment including armoured cars took a more easterly route through the hills from Fabbrica. The main part of the force entered Bargino on Route 2 about midday, but was delayed in the afternoon by demolitions and mines and came under long-range shellfire. The bridge over the Terzona stream (which flowed into the Pesa) had been blown, and movement in the vicinity before nightfall brought shell and mortar fire from German positions at San Casciano.

(x)

The 1st Parachute Corps had withdrawn during the night of 23–24 July to an intermediate line south of the Olga Line, and had been ‘followed up sharply’ by forces which at daybreak were already close to the forward German positions. ‘Throughout the day the enemy continued his attacks in strength against 4 Para

Div, with heavy artillery and tank support. He made several local penetrations, all of which were sealed off. ...’30 On the night of 24–25 July 4 Parachute Division and 356 Division, holding the centre and left wing of 1 Parachute Corps’ sector, withdrew to the Olga Line, and the following night 29 Panzer Grenadier Division, on the corps’ right wing, also went back to this line. Fourteenth Army then held the Heinrich Line from the west coast to Empoli (on the southern bank of the Arno River about 15 miles west of Florence) and from there the Olga Line eastwards through Montespertoli (on 8 Indian Division’s front), San Casciano (on the New Zealand Division’s front) and Mercatale (on 6 South African Armoured Division’s front). Heavy attacks, ‘as expected’,31 were launched in 1 Parachute Corps’ sector on 25 July. By the end of the day 6 South African Armoured Division and 2 NZ Division were facing squarely up to the Olga Line.

(xi)

Sixth New Zealand Infantry Brigade, having fought in the Arezzo sector, had been held in reserve during the initial stages of the advance to Florence, but had been kept well forward so that, when required, it could pass through 5 Brigade and maintain the impetus of the advance. Divisional Headquarters issued orders at 7 p.m. on the 25th that 5 Brigade was to continue the advance during the night to a line running through Montagnana to a bridge over the Pesa west of Cerbaia. When this objective had been secured, and at a time to be decided by the two brigade commanders, 6 Brigade was to pass through the 5th, establish a bridgehead over the Pesa in the vicinity of Cerbaia and advance northwards to a line west of the Pian dei Cerri hills32 and about half-way to Signa. On the same night Armcav was to capture San Casciano and remain responsible for the protection of the Division’s right flank. Next day (the 26th) 5 Brigade was to patrol to the north-west and 4 Armoured Brigade was to be prepared to operate to the east and north-east of 6 Brigade’s objective.

When the GOC told the corps commander, during a telephone conversation in the evening of the 25th, that the Division was putting through another brigade to attack in the direction of Signa, General Kirkman wondered whether it would not be better for the Division to direct its attack on to a bridge in Florence as he appreciated that it would be less likely to capture the Signa

bridge intact. Next morning Divisional Headquarters issued fresh orders which provided for the possibility of capturing both the Signa bridge and a bridge in Florence. After passing through 5 Brigade, 6 Brigade was to form a bridgehead over the Pesa between San Casciano and Cerbaia and advance north-eastward on to the Pian dei Cerri hills. Armcav was to capture San Casciano, if the opposition was not too strong, and protect 6 Brigade’s right flank. If San Casciano was not captured, Armcav was to continue to threaten the town from the south and south-east. Divisional Cavalry was to advance on the left of 6 Brigade to the Arno River eastward from and including the Signa bridge. Fourth Brigade was to be prepared to pass through 6 Brigade’s objective on the Pian dei Cerri hills, and taking Armcav under command, advance to the Arno westward from and including the westernmost bridge (Ponte della Vittoria) in Florence.

(xii)

As 5 Brigade’s front was gradually narrowing between the Pesa River and the Division’s western boundary, Brigadier Stewart decided to let 21 Battalion alone continue the advance while 28 Battalion protected the axis road from the west until 8 Indian Division drew level on the flank.

Shortly after midnight on 25–26 July B and D Companies of 21 Battalion were sent up (on foot, because 6 Brigade’s transport, now on the way forward, had priority on the road) to relieve the leading troops of 28 Battalion. The enemy counter-attacked the Maoris that night, and Major Awatere33 therefore decided to leave his men forward with 21 Battalion’s. A platoon from the 21st and one of C Squadron’s tanks went along the road to the north-west and soon met strong opposition. Three enemy machine-gun posts were silenced, but fire from mortars and what was claimed to be a Tiger tank forced the party to retire with half a dozen casualties.

The GOC gave orders that there was to be no infantry attack in daylight on the 26th. The forward positions were shelled and mortared throughout the day. A Company, 21 Battalion, still near the demolished Pesa bridge, was under fire from the San Casciano spur. This slackened towards evening, but when three of C Squadron’s tanks attempted to reconnoitre a possible ford, they were caught in a fresh outburst of shelling; all three were hit and one was set alight.

The fire from San Casciano was sufficient to prevent Armcav from making any progress beyond the Terzona stream, about a mile and a half south of the town. Reports were received that Tiger tanks and anti-tank guns were defending San Casciano, which was shelled and twice raided spectacularly by fighter-bombers. Patrols sent out eastward in the afternoon met South African patrols and learnt that the enemy was still holding strongly in the Mercatale area.

General Freyberg, feeling that he should not leave the Division at this time, deputed Brigadier Inglis on 26 July to receive His Majesty the King when he passed through the New Zealand sector while visiting the troops in Italy. Only men from the units not in action, which included part of 4 Brigade and 23 Battalion, were available to line a road about 20 miles from Florence to cheer King George, who sent the General a message that he was sorry he had not been able to see him but quite understood.

(xiii)

Fifth Brigade’s plan for the night of 26–27 July was for 21 Battalion to continue the advance north-westwards to the village of Montagnana, while 28 (Maori) Battalion guarded the western flank until 8 Indian Division drew level.

With strong artillery support, D Company of 21 Battalion, accompanied by some 17-pounder guns and sappers with a bulldozer, and joined later by tanks of C Squadron, 18 Regiment, led the advance along the road past San Quirico to where it forked about a mile and a half from Montagnana. B Company, without support, went along tracks and across rough country to the nearby village of La Ripa, which it reached unopposed. Word was sent back immediately that the way was clear for 6 Brigade.

When troops of 26 Battalion, coming up for the attack across the Pesa River, reached La Ripa, it was decided to pass B Company, 21 Battalion, through D Company to continue the advance to Montagnana. B Company was joined by a party of tanks, 17-pounders and engineers, and set off before dawn on the 27th. The enemy offered little resistance, but left freshly-blown demolitions and mines, which kept the sappers busy clearing a passage. As the light improved the company found that it was following a road along a spur in full view of the enemy on the high ground across the Pesa. Although several salvoes of shells were directed on the road, the German gunners appeared to be more concerned with the 6 Brigade troops gathering near the river. A report that Tiger tanks were in Montagnana was found to be incorrect, and B Company entered the village without opposition.

The havoc in a large mansion in Montagnana suggested that its owner might have incurred reprisal for pro-Allied sentiment, ‘for everything possible, furniture, glass, earthenware and oil paintings had been destroyed, presumably by the enemy. Even the wine casks in the cellar had been broached.’34 In the neighbouring village of Montegufoni, however, a property owned by the English family of Sitwell happily had escaped this fate. None of the family was in residence and the house had been taken over by the Italians to store a priceless collection of paintings. Apart from being structurally suitable for storage, it was situated in a hollow unlikely to be a defended position, which no doubt helped to preserve its treasures.

Two Divisional Cavalry men discovered that the only occupant of the Sitwell’s house ‘seemed to be a gentle old Italian with the air of a Major Domo. We felt rather like Barbarians in this house with its aristocratic atmosphere and we in our common army boots. Stacked around the walls were dozens of pictures and the largest of all was leaning against a table. This huge dark canvas commanded our attention. ... I’m no art connoisseur, but I knew that this was Botticelli’s Primavera. We were rather awestruck. Naturally we didn’t know that UNRRA35 were waiting to take care of the place, but we knew it should be reported immediately.’36

(xiv)

The occupation of Montagnana brought 5 Brigade to its final objective, the bound OMAHA.37 The Maori Battalion occupied positions along the open western flank. Because 6 South African Armoured Division had been unable to keep pace on 5 Brigade’s other (eastern) flank, it was necessary for the New Zealand Division to clear Route 2 and make a frontal assault on San Casciano while 6 Brigade exploited 5 Brigade’s success and crossed the Pesa to make a left hook round the north-west of the town. The enemy was expected to resist stubbornly at San Casciano, which was a centre of communications on commanding ground.

Armcav, driving up Route 2, had been held up on 26 July at the Terzona stream. Early next morning an armoured car patrol managed to cross farther upstream and reach a road junction near Mercatale, but was halted by mines on the Mercatale – San Casciano road. The main body of Armcav also crossed the Terzona and advanced along Route 2. The tanks and other vehicles were delayed

by demolitions, but shortly before 10 a.m. infantry of 22 Battalion entered San Casciano unopposed except by some sniper fire.

The town, at the junction of several roads, had been abundantly mined and booby-trapped, and the roads badly blocked by a combination of British bombing and shelling and German demolitions. When one of 22 Battalion’s carriers following the infantry struck a mine, two men were killed and three wounded. A house-to-house search by infantry and tanks cleared the town of snipers. The engineer detachment from 6 Field Company, with a bulldozer, worked hard to make the road passable up to and through the town, but this work became extremely hazardous about midday, when the enemy laid shell and mortar fire on the roads and their junction in the town. Much of this fire came from the east.

On the occupation of San Casciano Armcav passed from 5 Brigade’s command to 4 Armoured Brigade, which was to take over this sector and continue the advance. When tanks of 20 Armoured Regiment and the rest of 22 Battalion reached San Casciano, Armcav was disbanded.

Fourth Brigade sent out strong patrols, including armoured cars or tanks (or both), to reconnoitre the roads radiating from San Casciano. They found that movement north of the town was hindered by shelling and numerous demolitions and mines. B Squadron of 20 Regiment and 3 Company, 22 Battalion, attempted to go along the road leading north-westward through Talente to Cerbaia, but were halted by a bad demolition about a mile from San Casciano. One of B Squadron’s tanks was set alight by shellfire, another damaged on a mine, and a third halted by mechanical trouble.

Florence, about 10 miles to the north, was visible from a tower in San Casciano.

(xv)

Sixth Brigade had received orders on 26 July to pass through 5 Brigade with the task of forming a bridgehead over the Pesa between San Casciano and Cerbaia and continuing the advance. After 5 Brigade had occupied La Ripa, 26 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Fountaine) was to advance to the Pesa and establish a bridgehead as close to Cerbaia as 5 Brigade’s advance would allow. After crossing the Pesa this battalion was to attack objectives on the high ground to the north. It was to have under command C Squadron (less a troop) of 19 Armoured Regiment, a platoon of machine guns, a troop of six-pounder anti-tank guns, a section of 17-pounders, and a detachment of engineers. The 24th Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Hutchens), with a similar supporting force,

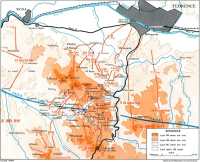

San Casciano to Florence, 27 July – 4 August 1944

was to follow hard on the heels of the 26th into the bridgehead and was to attack on its left. The 25th Battalion (Lieutenant- Colonel Norman), in reserve, was to form a firm base in the bridgehead.

The three battalions had been brought up to positions along the road south of San Pancrazio. A Company of 26 Battalion took over La Ripa from 21 Battalion at 3 a.m. on the 27th.

At the start of 26 Battalion’s advance the artillery, which had been firing on targets ahead of 21 Battalion, turned its attention to previously selected targets in the area of the proposed bridgehead and eastwards from Cerbaia to La Romola. The tanks and other supporting vehicles were unable to get past a mined demolition on the edge of La Ripa until a way had been cleared by the sappers of 8 Field Company. As dawn began to break the infantry and tanks came under shell and mortar fire from across the Pesa. The infantry reached the bank of the river about 7 a.m. and soon discovered that a heavy explosion heard earlier had been the demolition of the bridge.

No enemy was found on the western side of the river, so the tanks were called forward to assist the infantry to cross and attack Cerbaia, from which machine-gun fire was being directed at the men on the bank. A small bridge over a stream collapsed under the weight of the leading tank, which rolled over into the stream, but a bulldozer made a crossing for the other tanks, which engaged in a duel with enemy guns on the high ground behind Cerbaia.

A patrol investigated the demolished bridge, which had so dammed the Pesa that the fording of it appeared feasible. A Company’s commander (Major McKinlay38) decided about 8 a.m. to attack across the river. C Squadron’s leading tanks tried to cross where the slope of the bank offered a route, but two ran on to mines, and the others temporarily withdrew to cover while the sappers bulldozed a track in an unmined area. Meanwhile the infantry crossed and found that the enemy had gone from Cerbaia.

The remainder of 26 Battalion came forward on the western side of the Pesa, as also did 24 Battalion, which was intended to move across the rear of the 26th to a base at the nearby village of Castellare, also vacated by the enemy; there the 24th was to take over the left-hand sector of a two-battalion attack by 6 Brigade against the Pian dei Cerri hills. The tanks of B Squadron, 19 Armoured Regiment, under 24 Battalion’s command, crossed the Pesa at a shallow place discovered east of La Ripa and advanced to Talente, where they engaged enemy gun positions, but apparently

did not make contact with the 4 Brigade patrol attempting to reach Talente from San Casciano.

The New Zealand Division had been able to occupy San Casciano and Cerbaia without opposition and reach its final objectives west of the Pesa on 27 July because 1 Parachute Corps had withdrawn the previous night, as planned, to the Paula Line. The Division now was about to embark upon the final and hardest-fought stage of its advance to Florence.

III: The Pian dei Cerri Hills

(i)

The Paula Line, the last of the enemy’s planned delaying positions south of Florence, followed an eastward course from Montelupo, at the confluence of the Arno and Pesa rivers, across Route 2 towards the Arno valley between Florence and Arezzo. When 1 Parachute Corps withdrew to the Paula Line on the night of 26–27 July, the adjacent left wing of 14 Panzer Corps went back to the same line, and the point of contact between the two corps was moved eastward (to about two miles west of Cerbaia) to give 1 Parachute Corps a smaller sector, which enabled the enemy to thicken the concentration of armour, artillery and infantry opposing the two divisions – the New Zealand and South African – most closely approaching Florence.

As a result of this contraction of 1 Parachute Corps’ front the New Zealand Division, which had been opposed from the start of the advance by 4 Parachute Division, now faced its western neighbour, 29 Panzer Grenadier Division, whose sector included the high ground of the Pian dei Cerri. From the crest of these rolling wooded hills, rising in places over 1000 feet, both the Pesa valley to the south and the Arno valley and Florence to the north could be dominated by fire.

The New Zealand Division’s front had widened sufficiently to permit a two-brigade attack against this high ground. General Freyberg was confident early on 27 July that an advance over the Pian dei Cerri would drive the enemy back and clear the way to Florence. He discussed plans for the opening of a New Zealand club in the city. By the evening, however, it was obvious that the Division had run up against more determined opposition than it had yet encountered in the campaign, and that something more in the nature of a set-piece attack would have to take the place of the probing advances by single companies which had succeeded up to this stage. The plan for that night, states the GOC’s diary, was ‘modified and qualified and modified again in the usual

manner.’ Finally it was decided that 4 and 6 Brigades should make independent attacks with limited objectives.

On the left of the New Zealand sector 8 Indian Division had entered Montespertoli unopposed on the morning of 27 July and, before the day ended, had drawn level with 5 NZ Brigade, whose role of protecting the New Zealand Division’s left flank therefore was no longer necessary. On the right of the New Zealand sector 6 South African Armoured Division had found Mercatale, south-east of San Casciano, vacated by the enemy, but had been able to advance only a short distance beyond the village against stiffening resistance and under fire from guns on the high ground around Impruneta, and also had come up against strong enemy positions on Poggio Mandorli, south of Strada. Thus, until such time as the South Africans should draw level, 4 NZ Armoured Brigade, which was proposing to push north from San Casciano, had an unprotected right flank and was exposed to counter-attack and to fire from the guns around Impruneta.

(ii)

The plan on which 2 NZ Division acted on the night of 27–28 July evolved from the earlier orders, which had given less importance to the occupation of San Casciano than to the formation of the bridgehead over the Pesa by 6 Brigade. After establishing the bridgehead 6 Brigade was to have occupied the line La Romola–San Michele (this bound being given the codename ATLANTA) and then the crest of the Pian dei Cerri hills (BROOKLYN).39 As San Casciano would have been untenable by the enemy once 6 Brigade was on these heights, the capture of the town had been left to Armcav. Fourth Brigade’s original role had been to pass through 6 Brigade on the capture of BROOKLYN and make a dash to the Arno in three bounds, while Divisional Cavalry made a similar advance on the left flank. Because all three brigades of the Division would have had to use the single route gained by 5 Brigade’s advances west of the Pesa, precise priorities had been allotted for the movement of fighting and maintenance vehicles.

The enemy’s early and scarcely expected withdrawal from San Casciano40 caused a change in plan. The advantages of occupying the town were recognised before Armcav had entered it. Instructions issued at 9.30 a.m. on the 27th gave 4 Brigade a new thrust line, northwards from San Casciano to Giogoli and then by the three

bounds to the Arno. This would ease the Division’s supply lines by widening the front and using Route 2 to San Casciano and the roads to Giogoli, and also would allow 4 Brigade’s tanks to avoid the more formidable of the Pian dei Cerri hills.

When it was realised that the South Africans were unlikely to keep pace with the New Zealand advance the scope of the plan was modified by a message sent by Divisional Headquarters at 7.35 p.m., by which time 4 Brigade had absorbed Armcav and 6 Brigade had tested the opposition on its front. Fourth Brigade now was given the task of attacking the eastern portion of the objective BROOKLYN, from a road fork south of Poggio delle Monache to La Poggiona, and 6 Brigade the crest of the Pian dei Cerri, which it was to gain in three stages.41 The two brigades were to attack independently. A further modification, issued at 10.40 p.m., limited 4 Brigade’s objective to the high ground from north of Faltignano to La Romola, and 6 Brigade to its first objective (Poggio Cigoli to Torri). Divisional Cavalry was made responsible for the road leading north-east from Geppetto, on the left flank.

Sixth Brigade, in a message issued at 11.30 p.m. on the 27th, instructed its units42 that the ‘intermediate objectives’ were to be attacked that night, Poggio Cigoli (Point 281) by 26 Battalion and La Liona (Point 261) by 24 Battalion; the advance to the ‘final objectives’, Poggio Valicaia (Point 382) and La Sughera (Point 395), would not be carried out until 4 Brigade had ‘completed tasks on right flank’.43 This second phase was expected to take place on 28 July. The 25th Battalion was to remain in reserve and protect the bridgehead over the Pesa River and the left flank.

Several roads led into the hills from the vicinity of Cerbaia, one north-eastward along a ridge to La Romola and beyond to join the San Casciano–Giogoli road; another from Castellare up a ridge to San Michele and over the Pian dei Cerri; and another, also from Castellare, up a ridge between La Romola and San Michele. Sixth Brigade’s first objectives (Points 281 and 261) were on this middle ridge.

C Company, which was to take 26 Battalion’s first objective (Point 281), crossed the Pesa, passed through A Company at Cerbaia before midnight, and was joined by two troops of C Squadron,

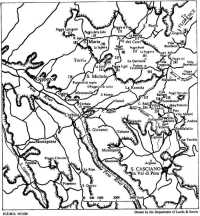

The Pian Dei Cerri Hills

19 Regiment. A section (two Vickers guns) of 6 MG Platoon was loaded on to the tanks, and anti-tank guns were hitched on behind some of them. Just before 1 a.m. C Company reached its start line on a side-track (from Cerbaia di sopra44) linking the Cerbaia – La Romola road with the road on the middle ridge. B Company followed C into Cerbaia, while D waited west of the Pesa until called forward; B and D were to occupy the second objective (Point 382).

A Company, which was to take 24 Battalion’s first objective (Point 261), crossed the Pesa after dark; B and D, which were to occupy the second objective (Point 395), waited on the other side. C Company covered Battalion Headquarters, which was set up in Castellare. A Company was delayed by shellfire while crossing the

river and, instead of passing through Castellare as it should have done, eventually found itself in Cerbaia; it then followed the route taken earlier by C Company, 26 Battalion, to the start line, and was at least an hour and a half late in starting.

The tanks of B Squadron which were to support 24 Battalion did not arrive until much later. As soon as dusk obscured enemy observation, they left the Talente area (south-east of Cerbaia), where they had arrived earlier in the day, but could make only slow progress because of demolitions, mines, scattered fire and mechanical troubles. About 10 completed the journey, the leaders reaching Castellare not long before dawn on the 28th.

(iii)

C Company, 26 Battalion, advanced up the road from Castellare on the middle ridge (between La Romola and San Michele), but owing to the difficulties of the going and the need to sweep for mines, the infantry soon outdistanced the tanks. As early as 2 a.m. the company reported back that it had covered the two miles to Poggio Cigoli (Point 281) and was beyond that point, but had not been able to make contact with 24 Battalion on its left flank. Brigade Headquarters learnt at 3.30 a.m. that C Company’s leading men were on the road some 500 yards north of Point 281, but the tanks, having been held up by a demolition, were well to the rear.

The Vickers guns were unloaded and the anti-tank guns unhitched, and while two tanks returned to bring up more guns, five managed to get past the demolition and push on to join the infantry. They overtook part of the reserve platoon (14 Platoon), which had been given the task of covering the sappers and guiding the tanks, and about daybreak were in a position from which they could cover the infantry ahead.

As the light improved, C Company, which had dug in hastily on both sides of the road, came under mortar and shell fire, and by the time the tanks arrived the whole area was under constant fire from almost all quarters. Obviously the company had penetrated well into the enemy’s lines. Anti-tank guns were firing from the La Romola ridge, almost due south, and other fire came from the north-west, west and south-west along the San Michele ridge.

In fact C Company had gone farther than had been intended,45 probably because it had appeared at that stage that the enemy had

either withdrawn or was withdrawing. The OC (Major Kain46) apparently had felt at liberty to exploit as far forward of the first objective as he could get. It had been demonstrated during 5 Brigade’s advance west of the Pesa that single companies forging ahead almost independently had made great gains on the heels of a retreating enemy, and it was not yet fully understood that the Division had come up against the Paula Line, which was to be stubbornly defended. The thought of being the first into Florence was in everyone’s mind.

A detachment from B Company of platoon strength followed in C Company’s tracks but did not get as far as Point 281; it met men of 24 Battalion about dawn and remained with them. Meanwhile A and B Companies of 25 Battalion joined the 26 Battalion troops at Cerbaia.

A Company, 24 Battalion, after getting away to a late start along the route on the ridge taken by C Company of the 26th, found a house occupied by five Germans, who were taken prisoner, and released two men of 26 Battalion who had been captured by this party. Continuing its advance, A Company met men at the tail of C Company who had just overcome a German machine-gun post near the road, and also stopped and captured an enemy truck which had driven through C Company. As dawn approached, A Company was well short of its objective, Point 261, which was separated from the road by a wooded gully. The OC (Major Howden47) then gave orders for a defensive position to be taken up with two platoons covering the road and the third with Company Headquarters in a house. The company made contact with C Squadrons tanks and was joined by the machine-gun section which had been carried on them. Three of B Squadron’s tanks reached A Company’s house just as day was breaking; others took up positions farther back to cover the San Michele and Geppetto roads.

Evidently 6 Brigade’s advance had penetrated into a thinly held sector of the German defences between the strongpoints at La Romola and San Michele. Shortly after dawn on the 28th the enemy, who appeared to have a large concentration of guns and heavy mortars on the Pian dei Cerri hills, brought down heavy fire on the salient and the roads to the rear. He had often used shellfire to cover his withdrawal, and as he had not seriously counter-attacked for some time, the New Zealand commanders apparently were expecting him to fall back, as he had been doing during the last few days. They therefore took little immediate action to ease the isolation of the two companies in the salient.

There were signs, however, that the enemy was preparing to counter-attack from the high ground to the north, where movement was observed and on which the fire of the New Zealand guns was directed. The tanks of B Squadron in the salient were finding it difficult to avoid the fire of enemy self-propelled guns or tanks on the San Michele ridge, while those of C Squadron were exposed to fire from tanks and anti-tank guns on the La Romola ridge. Of the seven C Squadron tanks supporting C Company, 26 Battalion (the original five plus the two which had gone back to bring up more anti-tank guns), two were knocked out and four damaged. Those mobile enough to avoid the fire from La Romola withdrew down the road past Point 281, which left C Company without support.

Under fire from three sides, C Company’s men gathered in the house north of Point 281 where Company Headquarters had been set up. A Company of 24 Battalion also drew in its platoons and concentrated around a house south of Point 281. About 10 a.m. German infantry began to close in on C Company’s house. Kain ordered his men to drop back by sections, well dispersed, which they did, taking their wounded with them. On the way they were joined by some men of C Squadron whose tanks had been immobilised. At A Company’s house the combined group (which also included the platoon from B Company, 26 Battalion) took up positions.

Having forced C Company to withdraw, the enemy seemed to pause in his counter-attack, but maintained steady fire across the whole front. The three tanks of B Squadron which had gone to the support of A Company, 24 Battalion, were knocked out or badly damaged, and one or two more of the same squadron were put out of action on the left flank. Late in the morning the tanks of B and C Squadrons still in running order retired down the ridge to refuel and replenish, evacuate the wounded and reorganise their crews. All the surviving tanks of the two squadrons were then placed under the command of B Squadron, and went back up the road.

Early in the afternoon the enemy appeared to be renewing the counter-attack from the north under shell, mortar, anti-tank and machine-gun fire, but was held off by 6 Brigade’s infantry, artillery, tank and heavy-mortar fire. The tanks engaged in duels with enemy tanks. The artillery shelled Points 281 and 261 and San Michele, as well as targets in the La Romola area, where the enemy appeared to be forming up as if he intended to counter-attack from that direction.

The German activity steadily increased towards evening, and

about 7 p.m. A Company, 24 Battalion, was attacked from the north and north-west. The enemy came close to the road (he may have crossed it) south-west of A Company, but did not threaten C Company and the platoon of B Company, 26 Battalion, on the eastern slope of the ridge. A Company reported at 7.15 p.m. that it was ‘completely surrounded’, and two minutes later that it was ‘in good strategical position. We will do our best. ...’ At 7.50 p.m. the company was ‘still fighting hard, posn a little easier, tanks engaging SP gun and MG posts.’48

Other enemy troops probed westward from the Tattoli area (about midway between La Romola and Cerbaia), and in an encounter with a platoon of A Company, 26 Battalion, which had taken up a position near Cerbaia di sopra covering the road to La Romola, captured two New Zealanders and wounded three.

Headquarters 24 Battalion received a message from A Company at 10.10 p.m. that the position was ‘still grim’49 but by that time other troops of 6 Brigade were on their way forward to renew the advance.

(iv)

Whatever success 6 Brigade might gain, it was unlikely that resistance on the Division’s right flank would lessen until the South Africans assaulted Impruneta. A long exposed flank would be too much of an imposition on 4 Armoured Brigade’s only infantry, 22 (Motor) Battalion, which would have to carry out both an assaulting and a protective role, even if the armoured regiments managed to break through the Paula Line. Brigadier Inglis therefore had asked for a battalion from 5 Brigade to guard this flank, and 23 Battalion, which the GOC agreed should be on temporary loan for the task, was waiting south of San Casciano early in the morning of 28 July.

Fourth Brigade’s role was to maintain pressure on the right flank to assist 6 Brigade’s assault on the left. After the various modifications of the Division’s plans on the evening of the 27th, 4 Brigade’s objective was an east-west line about two and a half miles north of San Casciano and, at its western end, some 300 yards south of La Romola; an intermediate objective was just over half-way to this line.50

The attack began at 1 a.m. on the 28th, with 2 Company of 22 Battalion and A Squadron, 19 Regiment, taking the road to

the north past Casa Vecchia, and 3 Company, 22 Battalion, and B Squadron, 20 Regiment, the Pisignano road to the north-west – towards La Romola.

The force advancing northward met no direct opposition, but came under machine-gun, mortar and shell fire in the vicinity of Casa Vecchia. The infantry reached the intermediate objective near Spedaletto well ahead of the tanks, which had to contend with demolitions. Although the leading infantrymen were reported at one stage to have penetrated much farther to the north, 2 Company’s ultimate positions were not beyond Spedaletto.

The force on the left also was delayed by demolitions. The infantry, going on ahead of the tanks, met opposition beyond Pisignano and withdrew about 400 yards to rejoin the tanks near the village, which was on a ridge overlooking the deep valley of the Sugana stream, on the far side of which was the La Romola ridge.

Before daybreak 4 Brigade was under the impression – as was 6 Brigade – that the enemy was withdrawing. On hearing about 5.30 a.m. of 26 Battalion’s almost unopposed advance up the Poggio Cigoli road, 4 Brigade instructed 3 Company and B Squadron to push on in an attempt to draw level with 6 Brigade’s right flank. At the same time orders were given for the formation of two parties, each of a troop of A Squadron, 20 Regiment, and a platoon of 1 Company, 22 Battalion, to search and mop up areas missed in the advance.

To investigate the route beyond Pisignano a troop of B Squadron and a section of infantry descended a steep track into the Sugana valley directly below La Romola and stopped short of a huge hole in the road which ran along the valley. About 7 a.m. all three tanks were set alight by shells thought to come from a self-propelled gun or Tiger tank. ‘Suddenly like a broadside from a huge battleship, the whole hillside opened fire simultaneously – 88 mms, mortars, spandaus, small-arms fire – everything seemed to come out at once from the whole area of the hill opposite.’51 The hostile fire continued ‘intermittently heavy or light almost without let-up’ all that day and night and the next.

Meanwhile, early on the morning of the 28th, the mopping-up parties entered the area between Spedaletto and Pisignano without opposition; one drove up the road through Cigliano to the crossing of the Borro Suganella, a creek which flowed into the Sugana stream below La Romola, but as it was then daylight and the tanks were exposed to fire coming along the valley from the direction of La Romola, they withdrew to cover.

The enemy did not counter-attack immediately – as he did on 6 Brigade’s front – perhaps because 22 Battalion actually had not penetrated the main positions of the Paula Line, but during the day he shelled, mortared and machine-gunned the forward positions, and heavily shelled San Casciano and the roads north of the town. Counter-battery fire, directed on the sources of this fire when they could be located, ‘occasionally caused diminution’.52 Nearly a dozen ‘murders’ or ‘stonks’ were laid on La Romola and its immediate approaches by 4 and 142 Regiments, which also engaged targets elsewhere on the front and east of the Greve River.

In mid-afternoon 2 Company asked for defensive fire to the north-east because of the likelihood of a counter-attack. Such an attack, supported by a self-propelled gun, appeared to be in progress at 3.45 p.m., but ‘the situation was well in hand’53 after some well-directed defensive fire by 4 and 142 Regiments and the engaging of the self-propelled gun by tanks of A Squadron, 19 Regiment.

(v)

The enemy undoubtedly was pleased with the performance of 29 Panzer Grenadier Division on 28 July. Fourteenth Army reported in the evening: ‘Fighting was extremely hard and confused, particularly on 29 Pz Gren Div’s front, where the enemy forced a penetration this morning at Cerbaia. All further attacks ... were beaten off with heavy casualties to the enemy. We committed our last reserves. This evening the FDLs were still in our hands all along 1 Para Corps’ front. ...’54

At 10 a.m. 15 Panzer Grenadier Regiment (on 29 Division’s right facing 6 NZ Infantry Brigade) counter-attacked north of Cerbaia and ‘came up against fierce defence by the New Zealanders and extremely heavy shellfire,55 but attacked again and again and pushed the enemy back with very heavy casualties and equipment losses. After 8 hours of fighting in tropical heat the FDLs were completely in our hands once more. ...’ In the sector where 71 Panzer Grenadier Regiment faced 4 NZ Armoured Brigade, attacks ‘were beaten off after stubborn fighting ... with heavy casualties to the enemy.’

The claim was made that 29 Division ‘has thus gained a complete defensive success against an enemy much superior in numbers. Its

artillery and tanks (129 and 508 Pz Bns) gave it excellent support in the actions. ...’ The division was commended for ‘the staunchness and fanatical stubbornness of every man.’56

Nevertheless the commander of Fourteenth Army (General Lemelsen) reported to Army Group C that, despite the successful defence, 1 Parachute Corps ‘could not continue to hold its present line unless it received fresh reserves, which Army did not have. ... The high ammunition expenditure of the last few days was also causing ammunition to run out, as petrol was so scarce that ammunition could not be brought up in adequate quantities.’57

IV: San Michele

(i)

Neither 4 nor 6 Brigade had fully gained the first objectives of the New Zealand Division’s plan for capturing the high ground of the Pian dei Cerri, and much of the armour, instead of being kept in reserve for exploitation when the high ground had been secured, had joined in the battle. For the New Zealand commanders 28 July was a day of conferences and the issuing of fresh directives, mostly verbal, for continuing the offensive.

General Freyberg, having earlier given permission for 23 Battalion to provide flank protection for 4 Brigade, agreed to Brigadier Inglis’s proposal that this battalion should hold on the right of the brigade’s sector while 22 Battalion closed to the left, with the purpose of thickening up the infantry screen on the brigade’s front so that much needed armoured reliefs could be carried out. The General, who visited both 4 and 6 Brigades in the afternoon, approved plans for limited attempts to gain the first objectives that night. Fourth Brigade was to get into La Romola if possible, and 6 Brigade was to attack San Michele.

(ii)