Chapter 7: The Drive to the Senio

I: From the Savio to the Lamone

(i)

DURING the absence of the New Zealand Division, Eighth Army continued its advance beyond the Savio River to the Ronco, which crosses Route 9 about two miles short of the town of Forli and flows northward across the Romagna plain alongside Route 67 to join the Montone River a mile or two from the city of Ravenna, near the coast. The army crossed the Ronco on 31 October, but because of bad weather did not enter Forli until seven days later. In the week of fine weather which ensued the enemy was driven back to the line of the Montone River, north of Route 9, and to the Rio Cosina, its tributary south of the highway. This advance permitted Eighth Army at last to open Route 67 (the Florence–Forli–Ravenna highway), which gave better lateral communication with Fifth Army.

By 16 November 5 Corps (Lieutenant-General C. F. Keightley) was brought to a halt. Reconnaissance north of Route 9 showed that the high stopbanks between which the Montone flowed, the very muddy approaches and the enemy’s preparations for defence combined to form an obstacle which could be overcome only by a set-piece attack. South of Route 9 the enemy re-established himself in strong defensive positions, supported by tanks and self-propelled guns, with good fields of fire across country that was too muddy and soft to allow 46 British Division to manoeuvre its tanks.

(ii)

An appraisal of the Allied armies’ situation at this stage was not encouraging. Headquarters Allied Armies appreciated on 10 October ‘that active operations with all available forces should continue as

long as the state of our own troops and the weather permitted in the hope that by then we should have at least succeeded in driving the enemy back to the general line of the Adige [a river north of the Po] and the Alps and in clearing up north-western Italy. Secondly, when full-scale operations ceased, there should be a period of active defence during which the minimum forces would be committed against the enemy and the maximum attention paid to rest, reorganisation and training of all formations in preparation for a renewal of the offensive as soon as the weather should permit.’1

During the next fortnight Fifth Army failed to capture Bologna, and the exhaustion of the troops and the shortage of replacements, both British and American, began to be felt. No longer could it be assumed that there was any likelihood of pushing the enemy back to the Adige before it became necessary to halt the offensive. The immediate objectives, therefore, were limited to Bologna and Ravenna. It had been proposed that Eighth Army should continue its offensive at least until 15 November to take Ravenna and draw off the enemy from Fifth Army, which went over to the defensive on 27 October to rest and prepare for a final attack on Bologna. ‘If this plan was unsuccessful,’ wrote General Alexander, ‘then we should have to accept the best winter position that could be managed. ...’2

General McCreery, commander of Eighth Army, did not think three weeks would be long enough to rest the American divisions or to lull the enemy sufficiently into a sense of security on the Bologna front; he therefore suggested that the date be postponed a week or two, which also would allow his army to complete its programme of rest and regrouping. Shortly after the New Zealand Division was taken into reserve, the problem of resting the whole of 1 Canadian Corps was solved by making 5 Corps responsible for its immediate right flank protection, putting 12 Lancers in the place of 1 Canadian Infantry Division, and assigning the rest of the Canadian Corps front as far as the coast to Porterforce (consisting mainly of dismounted armoured regiments). Consequently Eighth Army, which now disposed only 5 Corps and 2 Polish Corps, would be in a better position to undertake the task assigned to it towards the end of November, when three fresh divisions – the two Canadian and the New Zealand – would again be available. It was anticipated that these divisions would be capable of fighting until mid-December.

After consulting both McCreery and Clark, therefore, Alexander decided that the date for terminating the offensive should be postponed to 15 December, that Fifth Army’s final attempt to capture

Bologna should be delayed until about 30 November, and that Eighth Army should be ready to launch an attack on Ravenna by the 30th. These offensives, however, were to be launched only if the weather was favourable and there appeared to be a good chance of success.

McCreery’s immediate intentions at the end of October had been that 5 Corps and the Polish Corps should continue the attack in the better going on the left of the Eighth Army front, with the object of attracting German formations from the Bologna front and, if possible, of capturing Ravenna as well as Forli; at the end of November the three fresh divisions were to be thrown into the fortnight’s all-out effort to take Ravenna, if the city had not fallen already.

The feasibility of this plan was questioned, however, when the allotment of artillery ammunition for November was known. Eighth Army had been obliged from the middle of October to scale down its expenditure to a basic rate of 40 rounds a day for each field gun, 30 for each medium, and 20 for each heavy. Now that the forecast for November and December threatened a further reduction to 25 rounds for field guns and 15 for mediums and heavies, there was doubt whether the reserves would be sufficient. McCreery reported to Alexander that if the operations planned for November were carried out, there would not be enough ammunition for the more important programme planned for December. Nevertheless he was told that the offensive was to go ahead as planned. A world survey of artillery ammunition had revealed that the supply was greater than had been expected. The allotment for December might be increased, but in any case every economy was to be practised, and Eighth Army’s apportioning to its corps was to be cut drastically to build up the essential reserves.

(iii)

Eighth Army gave instructions on 18 November for the final phase of the battle in which it was engaged. Faenza, the next town beyond Forli on Route 9, and the high ground to the south-west and on the west bank of the Lamone River were to be secured as a starting point. The objective was not more than eight miles distant, but the terrain was no easier than that already traversed.

Fifth Corps planned to advance in three phases: in the first 4 and 46 Divisions were to seize crossings over the Cosina stream (about midway between Forli and Faenza); in the second they were to continue the advance to the Lamone (which crossed Route 9 immediately in front of Faenza), and 10 Indian Division was to be committed on the right or left of 4 Division according to the demands

of the situation; and in the third phase, for which detailed orders had not yet been issued, the corps was to cross the Lamone and capture Faenza. The corps was to be given the greatest possible support by medium bombers of the Tactical Air Force and light and fighter-bombers of the Desert Air Force, whose programme would allow for the vagaries of the weather.

Fifth Corps also was to have additional artillery support, which included the three New Zealand field regiments. The New Zealand artillery group, totalling 430 vehicles, left the Division’s rest area in the Apennines on 17 November, followed the familiar Route 16 to Rimini and continued north-westward along Route 9 to a staging area near Cesena. The guns, now under 5 Corps’ command, were disposed within a mile or two to the north and west of Forli. They were to fire a barrage to assist in an attack on a mile-long stretch of the Cosina between Route 9 and its confluence with the Montone north of the highway.

A strong German raid shortly before the attack was about to start (at 2 a.m. on 21 November) prevented the left-hand battalion (2 Cornwalls) of 10 Brigade, 4 Division, from approaching the stream on the route chosen for it, and by dawn only one company had reached the objective on the far bank north of the railway. With the help of the artillery this company beat off several counter-attacks by infantry and tanks and captured some prisoners. The assault by the other assaulting battalion (1/6 Surreys) of 10 Brigade was broken up by minefields and machine-gun and mortar fire, which caused many casualties. Keightley therefore called off the attack. The company of Cornwalls was withdrawn from its isolated position across the stream under cover of artillery smoke.

Fifth Corps made a fresh plan: 4 and 46 Divisions were to clear the German outposts east of the Cosina on the night of 21–22 November, and if the resistance weakened, 46 Division was to cross the stream, with 4 Division protecting its right flank; otherwise (if resistance had not weakened) both divisions were to attack the following night. On the right of 4 Division, 10 Indian Division was to relieve 12 Lancers and prepare to cross the Lamone north of Villafranca di Forli.

The clearing of the ground inside a loop of the Cosina south of Route 9 was completed during the night of the 21st–22nd, and the attack across the stream succeeded next night. A bridge was captured on 46 Division’s front before the enemy could demolish it, an Ark gave an additional crossing, and the tanks joined the infantry on the far side. Mud and the enemy’s artillery and machine-gun

fire did not prevent 4 Division from also getting both infantry and tanks across. The New Zealand Artillery supported the attack during the night and next day.

By nightfall on the 23rd the left wing of 5 Corps thus was firmly established across the Cosina on a front of three miles south of Route 9, and the Polish Corps had made some progress on the higher ground in the foothills of the Apennines. These successes, and an improvement in the weather which gave better going for the tanks, left the German 26 Panzer Division with no choice but to pull back to the shelter of the Lamone River, which meant that 278 Division, on the banks of the Montone, had to protect its exposed right flank, three miles in length, between the two rivers.

The 4th Division turned north on 24 November to begin the destruction of the German forces between the Montone and the Lamone. General Keightley ordered 10 Indian Division to cross the Cosina on Route 9 and also advance northward, on 4 Division’s right. This advance was expected to secure the early capture of the Casa Bettini bridge over the Montone about five miles north of Forli. Porterforce was to screen the Canadian Corps’ approach to the Montone north of this bridge.

The New Zealand Division was to relieve 4 Division, which was to hand over its specialised equipment, including ‘Wasps’, ‘Weasels’ and ‘Littlejohns’,3 to the New Zealanders and Indians.

The 46th Division advanced almost unopposed to the west bank of the Marzeno River, which joins the Lamone just south of Faenza. The Route 9 bridge over the Lamone at the entrance to the town and a bridge spanning the Marzeno above its confluence with the Lamone had been demolished, but an Ark was placed in the Marzeno, and by the evening of the 24th two battalions of 128 Brigade were across this river. While the brigade was preparing to cross the Lamone on the 26th, however, steady rain began to fall. The single Ark over the Marzeno was incapable of carrying heavy traffic, and the route beyond it soon became muddy and treacherous. Meanwhile 4 Division advanced on the north side of Route 9 to the Lamone; 10 Indian Division began to clear the west bank of the Montone towards Casa Bettini, but was thwarted by German strongpoints in houses short of the bridge.

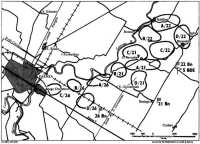

Dispositions, 27 November 1944

(iv)

Fifth Corps intended to capture Faenza and continue the advance along Route 9. In the first phase, which was expected to last until about 1 December, 46 Division (on the left) was to cross the Lamone south of Faenza, the New Zealand Division (in the centre) was to cross this river north of the railway line, which ran through the northern edge of the town, and 10 Indian Division (on the right) was to secure the bridge over the Montone at Casa Bettini and also cross the Lamone. At the conclusion of this phase 1 Canadian Corps would take over the whole of 10 Indian Division’s sector. In the second phase, which was to last five or six days, 10 Indian Division was to relieve the 46th (which was to pass to the command of 10 Corps) and complete the capture of the Pergola- Pideura ridge, south-west of Faenza; the New Zealand Division was to extend its left on to Route 9 and continue the advance. From 5–6 December 5 Corps proposed to keep going on both sides of Route 9, with the New Zealand Division on the right, 56 British Division in the centre, and 10 Indian Division on the left.

General Freyberg held a conference of senior New Zealand officers on 19 November, and told them that the Division was to attack northward from the Lamone to the town of Lugo (between the Senio and Santerno rivers). ‘It looks as if we are going with the

grain of the country. ... We are to push until the weather breaks – then close down for the winter. ...’,4

The Division came from the Apennine rest area in two stages, the first to the vicinity of Cesena, and completed the relief of 4 Division on the night of 26–27 November, with 5 Brigade on the right and the 6th on the left. The Division’s sector extended about 6000 yards along the Lamone River, from the vicinity of the village of Borgo Durbecco (on Route 9, separated from Faenza by the river, over which the bridge had been demolished) to Scaldino. The Lamone wound in a series of bends in a general easterly direction across 6 Brigade’s front and then took a more northerly course across 5 Brigade’s front. Sixth Brigade placed one battalion (the 26th) in the line, and kept the other three (24, 25, and Divisional Cavalry) back at Forli; 5 Brigade had 22 Battalion (on the right flank) and 21 in the line, and 23 and 28 Battalions in reserve. The infantry was given the usual support of tanks, anti-tank guns, mortars and machine guns.5 The New Zealand artillery returned from 5 Corps to the command of the Division.

The two brigades sent out many patrols at night to obtain information about the stopbanks along the Lamone – which varied from 15 to 25 feet in height – the width, depth and current of the water, and suitable crossing places. The enemy had made a stronghold in the hamlet of Ronco, just over the river on 22 Battalion’s front.

Along the river both sides brought down harassing and defensive fire, limited on the New Zealand side by the meagre supply of artillery, mortar and machine-gun ammunition. Because the 25- pounders were not allowed to exceed 10 rounds a gun each day, their shooting was augmented by tank gunlines provided by 18 and 20 Armoured Regiments.

The engineers had the most important task of keeping open a two-way road leading from Route 9 into the New Zealand sector, and roads and tracks giving access to the troops in the line. ‘What a mess,’ wrote an engineer officer. ‘The roads here are all sunken with deep drainage ditches down both sides and they act as a drain for all the surrounding country. Of course with shell fire and tanks chewing across ditches the drainage is all messed up and

the rain water just flows straight into the road.’6 The sappers were helped by tip-trucks and armoured dozers from British units, and by some 60 men of 240 (Italian) Pioneer Company who cut trees for ‘corduroy’.7 The rubble of brick houses which had been knocked about in the fighting was used as road metal. ‘Undamaged houses conveniently situated were evacuated and demolished for the same purpose’.8 On the night of 29–30 November, when the road to 5 Brigade’s sector became flooded and a wide gap eroded in it, the commander of 7 Field Company (Major Lindell9) quickly organised a bridging party, which – although two of its loaded vehicles were knocked out by the enemy – completed an 80-foot bridge in time for ammunition to be taken forward before dawn.

Fifth Corps and the Polish Corps were both holding the east bank of the Lamone on a front which extended about four miles north-east of Faenza. The crossing of the river had to be postponed because of the heavy rain which began to fall on 26 November. By the evening of the 27th the rivers and canals had risen to a dangerous level, and at the end of the month the ground was still too soft and the Lamone too swollen. This of course gave the German 278 Division and 26 Panzer Division – the latter depleted to a fighting strength of less than 1000 – time to reorganise and consolidate on the other side of the river, while 305 Division closed the gap created on the right of 26 Panzer Division by its hasty withdrawal across the Marzeno.

(v)

Plans for the resumption of the offensive by both Allied armies were agreed upon at an army commanders’ conference on 26 November. After Eighth Army had crossed the Santerno River, which it was expected would not be before the end of the first week in December, because the Lamone and Senio rivers had to be crossed before the Santerno, the two armies were to launch a combined offensive to capture Bologna, the Eighth by a westerly thrust north of Route 9, and the Fifth by a northward push along Route 65.

General McCreery planned that Eighth Army should attack with the Canadian Corps on the right, 5 Corps on Route 9, and the Polish Corps in the Apennine foothills on the left. He would be able to employ all three corps on a broad front because a suitable

axis of advance between Routes 9 and 16 was provided by a secondary road which left the Ravenna-Faenza road near Russi and ran westward through Bagnacavallo, Lugo, Massa Lombarda and Medicina to Bologna. This was allotted to the Canadian Corps, which was to take Russi, cut Route 16 north-west of Ravenna to ensure the capture of that city, and then go through Lugo to establish a bridgehead over the Santerno in the Massa Lombarda area.

At this stage the Germans faced Eighth Army from behind a water barrier which began along the Lamone River and ended at the Fiumi Uniti (passing just south of Ravenna), and which was broken only by a five-mile switch-line between Scaldino (by the Lamone) and Casa Bettini (on the Montone). An attack by 10 Indian Division on 27–28 November failed to secure the bridge site on the Montone at Casa Bettini, which was needed to enable the Canadian Corps to move up on the right of 5 Corps.

The original intention that the Canadians should relieve the whole of 10 Indian Division was modified to avoid a wide dispersal of their effort. Now they were to take over only the right portion of the Indian division’s sector, and consequently 5 Corps was to retain a front that would include a bridge (Ponte della Castellina) over the Lamone about five miles from Faenza and one built by the Germans at Gubadina, about a quarter of a mile upstream from Ponte della Castellina. When 10 Indian Division resumed the attack, the Casa Bettini bridge site was still its primary object, but it was also to try to take the Gubadina bridge intact and cross the Lamone. In addition the New Zealand Division was to send a force northward along the east bank of the Lamone and attempt to seize the same bridge (at Gubadina) and cross the river.

On 30 November the Indian division captured Albereto, the centre of the enemy’s resistance between the Montone and Lamone rivers, and loosed his hold on Casa Bettini. This opened the way for the Canadians to start crossing the Montone at dawn on 1 December, and they took command of the front from Albereto to the coast in the evening. The Indian division made strenuous efforts to reach the Lamone bridges at Gubadina and Ponte della Castellina, north-west of Albereto, but when men from 20 Indian Infantry Brigade closed up to them on the afternoon of the 2nd they found both bridges demolished.10

(vi)

A small force from 5 NZ Infantry Brigade, advancing northward along the eastern bank of the Lamone, had reached Gubadina ahead of the Gurkhas from 20 Brigade.

During a telephone conversation in the evening of 29 November General Keightley told General Freyberg that 10 Indian Division’s attack did not depend on 5 Brigade’s action ‘but would be very much helped if it went well.’ The corps commander added that the New Zealand Division ‘has the effect of attracting all Bosche troops round them like a magnet. He has every reason to know that when the NZ Division comes in something usually happens.11

D Company (Major G. S. Sainsbury) of 22 Battalion and C Squadron (Major Laurie12) of 18 Armoured Regiment, supported by artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire, were given the task of capturing a line from Casa di mezzo to Casa di sopra (about midway between Scaldino and Castellina) and exploiting to Ponte della Castellina. At a conference presided over by Lieutenant-Colonel O’Reilly it was decided that the force should capture Scaldino di sotto (north of Scaldino) and Casa di mezzo, and then, depending on how successful it had been, push on to the Castellina bridge.

At 8.30 a.m. on the 30th the infantry and tanks began their advance from the road east of Scaldino. The 25-pounders of 5 Field Regiment fired over 2000 rounds during the attack with good effect: Germans taken prisoner said the shelling had inflicted serious casualties. Although the ground was sodden, especially on the left flank, where the enemy resisted vigorously from the stopbank, the tanks gave excellent support to the infantry, who took Scaldino di sotto and, with the three platoons working independently, continued towards the scattered farm buildings of Rombola, Casa di sopra and Casa di mezzo.

On the right Second-Lieutenant E. B. Paterson’s platoon steadily approached Casa di mezzo, which was protected by a crossfire from spandaus spaced at intervals, and by bazooka, mortar and artillery fire. The tanks raked the spandau pits with their Brownings and blasted the building with their 75-millimetre guns, and the 25- pounders brought down a stonk almost too close for the comfort of the infantry, who made a frontal assault. They took the last 30 yards at a run, and a section sprinted round to the back to cut off escape. The platoon killed 11 of the enemy in the vicinity of the house and took nine prisoners (among them a company commander from 278 Infantry Division who yielded a rich haul of documents, including the current password, some marked maps and

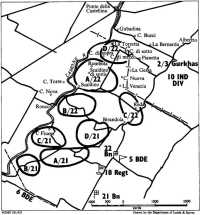

Dispositions, morning 2 December 1944

a minefield trace), and went on without much trouble to Casa di sotto, where it spent the rest of the day.

D Company’s centre platoon met misfortune in a minefield. Near a disabled tank one of two approaching German prisoners trod on an S-mine and escaped injury himself, but five New Zealanders fell wounded or severely shaken, and two of them died. This platoon and the one on the left cleared the ground between Casa di sotto and the river bank, completing an advance of 1200 yards, and by nightfall D Company was in possession of La Torretta and Casa di sopra as well as Casa di sotto, towards which a party of engineers opened a road. While clearing a booby-trapped road block two sappers were wounded, one of them fatally. D Company’s casualties were three killed and five wounded. One of C Squadron’s tanks had been knocked out on the minefield, and two immobilised by mechanical troubles; two casualties had occurred in a tank crew.

The tanks withdrew and M10s helped the infantry consolidate on the freshly won ground.

That night 22 Battalion patrolled from La Torretta and Scaldino to the Lamone and to Gubadina without making contact. After a three-man patrol had scouted to Gubadina, 16 Platoon occupied a large house close to the river, and at daybreak on 1 December ‘unsuspecting Germans directly across the road stretched and settled comfortably around three spandau pits and strolled round a small house.’13 The platoon trained its Bren guns on the spandaus, and when two Gurkha scouts came up the road from the direction of Albereto, opened fire on the enemy while a section charged out to seize the house and five of its occupants. Apparently the German survivors of 22 Battalion’s attack had retreated across the Lamone by a wooden bridge at Gubadina, but a party had returned to act as a battle outpost.

A Gurkha battalion relieved 16 Platoon later in the day, when 20 Indian Infantry Brigade took over Gubadina and the New Zealand and Indian divisions redistributed their troops.

A Squadron of 18 Armoured Regiment shelled the towers and belfries of Faenza which, it was suspected, sheltered German observation posts. A large tower collapsed ‘like an avalanche’14 in the afternoon of 1 December; another was destroyed the following afternoon, and others were damaged. During the shooting an elderly woman stood in the command post weeping and crying repeatedly, ‘la mia bella Faenza’. Faenza, a town with a history of sieges and sackings dating from 390 BC, was to be the centre of much of the New Zealand Division’s activities in the winter of 1944–45.

(vii)

From the jumping-off place secured by 10 Indian Division at Casa Bettini the Canadian Corps continued the northward clearing of the German switch-line positions between the Montone and Lamone rivers. On the left 1 Canadian Infantry Division captured Russi and turned westward towards the road and railway crossings of the Lamone on the way to Bagnacavallo. The Germans had withdrawn across the river, but 1 Canadian Infantry Brigade’s attempt to seize a bridgehead was harshly repulsed by the German 114 Jaeger Division.

The 5th Canadian Armoured Division made more satisfying progress on the right flank, where it cleared the west bank of the

Montone and cut the Russi-Ravenna railway and road. Meanwhile patrols of the 27th Lancers and Popski’s Private Army15 cross the Fiumi Uniti south of Ravenna. ‘Spurred on by this competition’,16 two squadrons of the Princess Louise Dragoon Guards, accompanied by a squadron of 9 Canadian Armoured Regiment, drove rapidly eastward along the Russi-Ravenna road. The tanks were stopped by a demolished bridge a mile from the city, which the infantry entered on 4 December to join hands with the Lancers.

II: The Capture of Faenza

(i)

Because the Lamone River downstream from Faenza flows between stopbanks rising 15 feet above the level of the surrounding country, where the approaches deteriorate rapidly in bad weather, it was decided to launch 5 Corps’ attack over the upper reaches of the river, where the stopbanks are smaller and the water channel is comparatively narrow. Quartolo, about four miles from Faenza, is about the most southerly point from which the Pideura ridge, descending from the Apennines west of the Lamone, could be climbed fairly easily; farther south the high ground is broken by steep escarpments. The very narrow sector of reasonably favourable ground over which the attack could be made, therefore, was limited on the right by the difficulty of crossing the river near the enemy-occupied town and on the left by the rough country farther upstream. There was no permanent road bridge in this sector; in fact the only bridge for several miles south of Faenza was within a few hundred yards of the town and completely dominated by it.

The enemy was expected to appreciate that Quartolo was the only place near Faenza where a crossing of the Lamone could be made without difficulty, but 5 Corps hoped to deceive him into thinking that crossings might be attempted elsewhere. In the first phase of the corps plan 46 British Division (commanded by the New Zealander, Major-General C. E. Weir) was to capture a bridgehead at (or near) Quartolo and the high ground at Pideura, drive north to cut Route 9 north-west of Faenza, free the town of the enemy, and clear a site for a Route 9 bridge across the Lamone; at the same time the New Zealand Division was to be ready to capture a bridgehead in its own sector, just north of the town, either to contain the enemy’s reserves or to take advantage

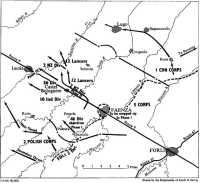

Plan for offensive, December 1944

of any thinning out of his forces there; 10 Indian Division was to patrol across the river to simulate an attack, cross it if the enemy thinned out, or stage a dummy attack, co-ordinated with the New Zealand Division, if he remained firm.

In the second phase of the corps plan the New Zealand Division was to pass through 46 Division and cross the Senio River on Route 9 to Castel Bolognese, a small town about four miles beyond Faenza, and then swing north; 10 Indian Division and 56 British Division were to relieve the 46th. In the third phase it was intended that the corps should advance with the New Zealand Division north of Route 9, 56 Division astride the highway, and 10 Indian Division south of it; all three divisions were to be prepared to swing to the north once Castel Bolognese had been captured.

(ii)

Low cloud and fog obscured the battlefield on 3 December, and the visibility was so poor in the afternoon that the tanks of A Squadron, 18 Regiment, had to stop shooting at the towers of Faenza. At 7 p.m., when 128 Brigade of 46 Division began to cross the Lamone

at Quartolo, 169 Brigade (from 56 Division but temporarily under the command of the 46th) began a feint towards Faenza from the south, and simultaneously the New Zealand Division and 43 Indian (Gurkha) Lorried Infantry Brigade simulated attacks across the river north of the town. The New Zealanders were to deceive the enemy with tank and infantry movements, artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire, bogus wireless traffic, and by assembling bridging material and smoking bridge sites if necessary.

These feints provoked an immediate and satisfying response, and for some time 128 Brigade advanced almost without opposition. In answer to the barrage the enemy brought down concentrated defensive fire, not only on the New Zealanders’ side of the river, but also on his own bank where assaulting troops might be expected, and most violently in the vicinity of the Ronco bridge site on 5 Brigade’s sector. One of 22 Battalion’s outposts complained ‘most bitterly’ of smoke shells (fired by a New Zealand battery) landing among its positions. Divisional Cavalry, which had relieved 26 Battalion in 6 Brigade’s sector on the 2nd, threw large stones into the river to give the impression that assault boats were being launched.

The German Commander-in-Chief reported to Berlin that ‘the enemy tried to cross the Lamone, both north and south of Faenza,’17 and the Berlin radio proudly announced that ‘strong attacks opposite and just North of Faenza were beaten off with heavy losses to the enemy, including losses of AFVs and trucks.’18

As the night wore on the enemy’s reaction to the feint abated and he turned his attention more to 46 Division’s front. The New Zealand Division, therefore, repeated its diversionary programme early in the morning of the 4th, and again the enemy took the bait: he threw a very heavy bombardment into the area screened by smoke on the approaches to Faenza and the Ronco bridge site. Obviously Ronco would have been an unhealthy place to have attempted a crossing of the Lamone.

Better visibility on 4 December allowed the Allied aircraft to support 5 Corps’ offensive: fighter-bombers attacked German gun and mortar positions, strongpoints on 46 Division’s front, and targets north of Route 9 – where 22 Battalion admired excellent strafing by rocket-firing aircraft on the opposite bank of the Lamone – and medium and light bombers also concentrated on gun and mortar positions. The German artillery fire dwindled under this onslaught.

After crossing the Lamone in the vicinity of Quartolo, where only scattered German outposts were met, 128 Brigade came up against the main line of resistance on the bare ridges south-west of Faenza, and could get no farther during the day. The New Zealand Division made another feint in the afternoon, and again the enemy reacted vigorously on 22 Battalion’s front, especially in the Ronco area, but only for five or 10 minutes.

By this time, however, the feints had served their purpose. The enemy, having sited his main positions back on the ridges above the river instead of along its winding bank, with the intention of counter-attacking as soon as he located the main Allied bridgehead, had hesitated in concentrating his reserves, with the result that 46 Division had driven a salient on to the high ground beyond the river before he was ready to counter-attack. On 7 December the British captured Pideura, the dominating village on the ridge.

(iii)

Although 46 Division’s crossing of the Lamone threatened Faenza and the German positions along the lower reaches of the river, the capture of the town and the breakthrough to the Senio River had not yet been achieved. Communications within 5 Corps’ bridgehead were tenuous and in danger of being severed by a rise in the Lamone, and the roads south-east of the river were not capable of carrying more than a few tanks and self-propelled guns. After four days’ fighting 46 Division was tired. The corps plan, therefore, would have to be modified, but without departing from the original intention.

The capture of Faenza was still to be 46 Division’s task before the New Zealand Division (on the right) and 10 Indian Division passed through, but 25 Indian Infantry Brigade was to relieve a brigade of 46 Division immediately, and 5 NZ Infantry Brigade was to be ready to move two battalions into the bridgehead at six hours’ notice if the capture of Faenza proved difficult. If General Weir considered he had sufficient troops, he was to attack Faenza with 25 Indian Brigade and 169 British Brigade, but if he needed additional troops, he was to use the two battalions from 5 Brigade. The New Zealand Division was to bridge the Lamone into Faenza as soon as the situation allowed. The 43rd Gurkha Brigade, which had been made responsible for the right of 5 Corps’ sector on 4 December, was to extend its front progressively southward to relieve the New Zealand units as they were required.

On the night of 7–8 December 25 Indian Brigade relieved 128 Brigade, and 169 Brigade moved completely into the bridgehead. A battalion (2/10 Gurkha Rifles) of 43 Brigade took over from

22 NZ Battalion next day, and the latter, now in reserve, went back to billets in Forli. Preparations were begun for assembling 23 and 28 NZ Battalions in 46 Division’s sector over the Lamone.

At this stage, however, the enemy counter-attacked. Having decided where the greatest danger to his defence lay, he prepared to break into 5 Corps’ bridgehead south of Faenza, where he had brought the British to a halt. On 46 Division’s right 169 Brigade was unable to close in on the town; in the centre, south of the hamlet of Celle (about two miles west of Faenza), 138 Brigade was confronted by strong concentrations of German tanks and infantry; on the left 25 Indian Brigade could gain no ground beyond Pideura.

On 9 December the enemy began ‘one of the heaviest bombardments of the winter’19 and attacked along the whole of 46 Division’s front, with his main weight against 138 Brigade south of Celle, where 200 Regiment of 90 Panzer Grenadier Division ‘attacked with tanks and infantry and high hopes and pressed forward regardless of loss’.20 Fifth Corps’ artillery, including New Zealand guns, ‘put down an unceasing curtain’ of defensive fire, and Allied aircraft bombed and strafed the German concentrations. The British inflicted ‘extremely heavy losses’21 on 200 Panzer Grenadier Regiment.

The enemy reported to Berlin that ‘after hand-to-hand fighting fiercer than any yet seen we succeeded in reoccupying a considerable tract of ground. ... Our losses were considerable. The enemy ... had enormous casualties.’22 The counter-attack, however, had failed: the enemy reverted to the defensive, with the regiments of 90 Panzer Grenadier Division deployed on the northern and western sides of 5 Corps’ bridgehead and 305 Infantry Division around Pideura.

(iv)

It was now apparent that 46 Division alone could not accomplish the first phase of 5 Corps’ plan, the capture of the whole of the ridge at Pideura and the cutting of Route 9 west of Faenza, with the object of taking the town and reopening communications along the highway; also, the relief of 46 Division could be postponed no longer. The offensive was halted, therefore, while the remainder of 10 Indian Division and part of the New Zealand Division were brought into the bridgehead.

While Faenza was still in German hands and Route 9 closed to traffic, the maintenance of the troops on the far side of the Lamone was most difficult. A seven-mile one-way track, known as the ‘Lamone road’, between Route 9 and 46 Division’s crossing at Quartolo so far had proved adequate only because of the great exertions of the British and New Zealand (8 Field Company) engineers who had built it and daily repaired it, but obviously was incapable of coping with any additional traffic.

It was decided, therefore, that 5 Corps should operate a road circuit with an ‘up’ track from Route 9 over a bridge across the Marzeno River to the Lamone and a ‘down’ track in the opposite direction over another bridge, and that traffic on the circuit should be regulated by a series of control posts. Because of the slowness of movement on this circuit, however, the New Zealand Division decided to maintain its troops in the bridgehead by a jeep train using a small part of 5 Corps’ ‘up’ track and another route opened by the Division’s engineers over the Marzeno and Lamone rivers.

Consequently, on the night of 9–10 December, 7 Field Company built a 100-foot Bailey bridge over the Marzeno close to a brickworks about a mile south of Faenza. This task took over nine hours, of which five were spent in carrying the components the last 60 yards to the site. ‘It was a cold starlight frosty night and the clanking of the Bailey parts probably caused the stonk [by Nebelwerfers] –the enemy was rather close to us and we had ... a covering party dug in around the bridge site.’23 Poplar poles were stuck in the ground to help conceal or camouflage what became known as the ‘Brickworks bridge’ and its approaches.

Fifth Brigade entered the bridgehead on the night of 10–11 December, the night after the Brickworks bridge was completed, and on the same night 6 Field Company, with an RASC platoon under command, assembled the components for a bridge in Cardinetta village, about two miles from Faenza, preparatory to constructing access for vehicles to 5 Brigade. A platoon under Lieutenant Hunter24 built a 110-foot Bailey with two sets of timber cribbing (for eight-foot piers) in daylight under the cover of smoke supplied by the artillery.

‘I selected an approach road site and kept all traffic off it,’ Hunter wrote, ‘got the bridging to the site and we got stuck into it by mid-morning. ... Had a straight go with only the occasional shell none of which landed too close to stop the job. Used half a dozen Itie haystacks for the wheeled vehicle road ... and covered it with reinforced mesh ... and put [demolished] houses

on top of the mesh. ... we plugged along and finished it late in the evening. ... A heavy day’s work for my gang and I can’t speak too highly of my platoon.25 Hunter’s bridge earned General Freyberg’s commendation.

The sappers toiled with corduroy, debris from houses and road netting laid on straw to make the two-mile track between the Brickworks and Hunter’s bridges ‘into something resembling a road’,26 which was used by the jeep train and later by tanks. In spite of these efforts, however, the jeep drivers were not favourably impressed. ‘Some drivers who had known the Terelle “Terror Track” declared they preferred it to the one they now had to use to supply 5 Brigade. ... Whereas at Terelle they could and did move at full speed, this was quite impossible in the mud. Thus, it often took the jeep train with rations twelve hours to get from Forli to 5 Brigade Headquarters. Harassing fire was a trouble but was nothing compared with the condition of the roads. On the night of 12–13 December, for instance, out of a convoy of twenty-six jeeps with trailers, two jeeps crashed over a bank, six trailers had to be temporarily abandoned beside the track and only sixteen won through to Brigade Headquarters. ...’ The supplies were then delivered to the companies by mule train or jeep. ‘If jeeps had accidents, so, too, did mules.’27

This road also made a strong impression on the New Zealand tank crews when they moved into 5 Brigade’s sector: ‘All up and down Italy the Division had struck all types of roads, some good, some indifferent, some downright dreadful; but this road to the Lamone was the champion of the lot. It startled even the oldest hands. In a desperate, urgent effort to keep supplies up ... the engineers had hacked the road out of cattle tracks, fields and river marshes. They had blown down houses and dumped tons of brick and rubble on top of the mud; they put down hundreds of tree trunks; they had built Bailey bridges under Jerry’s nose. They had shored up the ditches beside the track, and still these caved in under the weight of passing trucks. Sappers had to toil continuously to keep the road open.’28

(v)

The regrouping of 5 Corps was planned to take place in three stages: in the first 5 NZ Brigade was to enter the bridgehead, relieve 138 Brigade and part of 169 Brigade, and pass temporarily

to the command of 46 Division; 43 Gurkha Brigade and the New Zealand Division were to sidestep to the left. In the second stage the New Zealand Division was to take over 46 Division’s right sector (by resuming command of 5 Brigade) and 10 Indian Division its left sector; in the third stage 169 Brigade was to relieve the Gurkha Brigade.

On the night of 10–11 December, therefore, 28 (Maori) Battalion relieved a battalion of 169 Brigade, 56 Division, on the right, and 23 Battalion relieved two battalions of 138 Brigade, 46 Division, in the centre; next night 22 Battalion relieved the third battalion of 138 Brigade on the left. Meanwhile 21 Battalion was replaced north of Route 9 by the Gurkhas and went back in reserve to billets in Forli.

The Maoris, ‘muffled to the ears’ on a cold winter’s day, were put down from their trucks near the Marzeno and marched two miles across muddy creeks and the Lamone to the headquarters of 2/5 Queens, in a large building, where they stayed until night. They completed the changeover ‘with some care and in extreme silence for, according to the guides, “Jerry was very trigger happy and at the slightest sound they would know all about it.” It was a matter of crawling to the most forward casas and, as the ground was very muddy, some of the Maoris soon got careless and began to walk. A stream of tracer about waist-high decided for them that perhaps crawling was the better method.’29

The battalion was disposed in the vicinity of a road junction – which became known to the Maoris as ‘Ruatoria’ – a little more than a mile from the outskirts of Faenza. Two roads and a railway led into the town and a third road north-westward to the hamlet of Celle. Houses occupied by the enemy were only 150 yards away. Sergeant Cullen30 took a patrol of 11 men of 8 Platoon to investigate one of these houses, and discovered ‘a real hornets’ nest. Three well-hidden tanks were behind the building. The patrol was detected and a battle royal ensued in the darkness while the patrol withdrew with four wounded. The medium and heavy mortars were turned on to the locality and the tanks were heard moving back towards Faenza, whereupon Cullen returned with his patrol and killed six Germans who were still in the house.’31 The Maoris were preparing to settle in when the tanks returned and shelled the house. Again the patrol withdrew, this time with four more wounded.

The 23rd Battalion debussed less than two miles from Faenza and marched 10 miles in five hours on muddy road verges to take

over from 6 Lincolns and 6 York and Lancasters in positions on the left of the Maori Battalion. As the New Zealand armour was not expected to arrive for several days, 15 tanks of the Queen’s Bays stayed in the bridgehead.

Harassing fire and patrols caused a few casualties. Two stretcher-bearers and another man, sent to collect four wounded from B Company of 23 Battalion, went in error to the wrong house and were taken prisoner. This might have been the enemy’s first evidence of the New Zealanders’ presence. Later 90 Panzer Grenadier Division fired into 5 Brigade’s lines shells containing leaflets which proclaimed how the ‘boys of the 2nd NZ Division’ invariably were needed ‘when the going becomes rough. ... Now, on the eighth day of the Battle for Faenza, after the British 56th Division failed with tragic losses, you are called to save the situation. You may reach Faenza, but every yard towards that town must be paid for with the life blood of hundreds of New Zealanders. ...’32

The enemy in slit trenches and dugouts at Casa Colombarina could be seen clearly by C Company of 23 Battalion from the Ragazzina ridge, and was harassed by artillery, mortars and snipers. ‘It was rather unique for us to hold the high ground from the outset, and from an excellent O.P. a murderous fire was directed on this strongpoint,’ Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas wrote. ‘The Hun sustained casualties, stretcher bearers and ambulance being seen from our O.P.’33

The relief of 2/4 King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry by 22 Battalion, on the left of the 23rd, was completed on the evening of 11 December. In this position most of 22 Battalion could look across a steep, bush-covered descent to a sharp rise, near the top of which ‘stood the pocket-fortress of Casa Elta.’34

While 5 Brigade replaced 46 Division in the bridgehead west of Faenza, 6 Brigade side-stepped to the left on the other (south-eastern) side of the Lamone. On 10 December its boundary with 43 Gurkha Brigade was brought southwards to the railway, which placed two squadrons of Divisional Cavalry immediately opposite Faenza, D between the railway and Route 9 and C near the confluence of the Marzeno and Lamone just south of the town and the highway. The other two squadrons were farther back. On the left of Divisional Cavalry, 24 Battalion replaced 44 Reconnaissance Regiment (under the command of 46 Division but from 56 Division) between the Marzeno and Lamone.

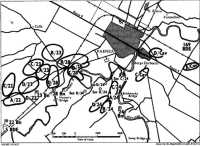

Dispositions, 12 December 1944

The tanks of 18 Armoured Regiment and A Squadron of 20 Regiment entered the bridgehead and came under 5 Brigade’s command on 13 December. They were weighed down with extra ammunition and fuel, and 18 3-ton lorries also carried fuel. The move took all day. ‘The convoy crept along at walking pace, past dozens of trucks lying forlornly with wheels in the air, past gang after gang of workers ... for at the soft places every tank left its quota of damage. By the Lamone, where the road came into Jerry’s view, the unit went through a smoke screen specially laid for it, a thick grey fog that blotted everything out except the few yards immediately round you. Not a shell came near throughout the move, and everyone breathed freely again, for that road had an evil reputation.’35

The anti-tank batteries brought forward M10s, 17-pounders and heavy mortars. The artillery was able to support both brigades. Three companies (36 Vickers guns) of 27 (MG) Battalion were placed where they could harass the enemy at night.

The relief of 46 Division was completed on the morning of 12 December, when the New Zealand Division took command of the right sector of the bridgehead, occupied by 5 Brigade; 10 Indian Division had resumed command of 25 Brigade on the left sector

the previous day. The final stage of 5 Corps’ regrouping was the relief of 43 Gurkha Brigade by 169 Brigade of 56 Division on the 13th, when the Gurkhas withdrew into reserve. That day, therefore, 56 Division held the line of the Lamone from the corps’ right boundary to the railway, 2 NZ Division extended across Route 9 and straddled the Lamone south-west of Faenza, and 10 Indian Division held the remainder of the bridgehead across the river on the left.

(vi)

Fifth Corps was now ready to begin the second phase of its offensive, which had for its object the capture of crossings over the Senio River south of the Rimini-Bologna railway and about three and a half miles beyond the Lamone River. Faenza, the objective of the first phase, was to be cut off and secured as the advance progressed.

The corps’ plan was to attack with the New Zealand Division on the right and 10 Indian Division on the left. The first objectives, which were to be captured by dawn on 15 December, were for the New Zealand Division Point 54, 1000 yards north-west of Celle, and for the Indian Division the ridge and road 1000 yards north of Pergola and the high ground nearly a mile north and north-west of Pideura. Both divisions, after taking these objectives, were to cross the Senio. At the same time 56 Division, on the right flank was to simulate an assault across the Lamone in the vicinity-of the Ronco bridge site. On the other flank the Polish Corps, co-ordinating its attack with 5 Corps, was to strike for the rising ground beyond the Senio west of Riolo del Bagni, about six miles north-west of Castel Bolognese.

The plan for the capture of Faenza depended on whether or not the enemy still firmly held the town after the New Zealanders had reached their objective beyond Celle. If necessary, a Faenza Task Force (43 Gurkha Brigade with tank, artillery and engineer support) was to cross the Lamone and clear the town while the New Zealanders continued their thrust towards the Senio.

General Freyberg discussed the Division’s part in the operation with the brigadiers and heads of individual services on the morning of 13 December. The GSO III (Intelligence), Major Cox,36 estimated that the maximum enemy strength on the Division’s sector was 1085 men, 112 guns and up to 60 tanks (of which a third might be Tigers). If 700 Germans were holding the front, the Division would

have an advantage of two to one. The GOC told the conference that ‘the basis of our plan is surprise.’ It was hoped to show no more than normal activity until zero hour, 11 p.m. on 14 December, when ‘we will open with everything we have, hit him a crack and go as hard as we can and try to take advantage of any surprise we can gain by the rapidity of our blow. ... We want to hit him when as many of his troops as possible have their boots off and have gone to sleep. ...’37 The high ground that the Indian division was attacking was very important because it overlooked the whole area, which included the German gun positions. Celle would be the key to the New Zealand sector.

A divisional operation order issued in the evening of the 13th said 5 Brigade was to advance at the rate of 100 yards in seven minutes to the first objective, and then continue to the bridge over the Senio on Route 9 and the high ground overlooking the river farther west at Casale. Sixth Brigade was to take over the sector held by 28 Battalion and protect the right flank during 5 Brigade’s advance. If the enemy remained firm in Faenza in spite of the attack, the Faenza Task Force was to clear the town. The engineers were to construct a bridge over the river in the vicinity of Faenza.

Fifth Brigade’s first objective was a shallow inverted V about two and a half miles in length, which began on the right at a road and rail crossing near the outskirts of Faenza, passed north of Celle to a road and track junction about half a mile beyond the hamlet, and then continued south-westward to the junction of a lateral road ascending the ridge west of Celle and a road running north from Pergola. The Maori Battalion, on the right, was to attack with half of A Squadron, 18 Armoured Regiment, in support, and would have to fan out slightly to reach its objectives; 23 Battalion, in the centre, supported by B Squadron, would be attacking where the enemy was expected to be the strongest – the hamlet of Celle, the flat ground beyond it and the edge of the ridge, 22 Battalion, on the left, with the other half of A Squadron in support, would be attacking in the most difficult country, where its objectives would be on the lateral road on the ridge west of Celle and (in co-operation with the Indians) the high ground on the left flank.

A Squadron of 20 Regiment was to assist the advance by fire on the right flank in the direction of Faenza, and was to be prepared to support 6 Brigade. C Squadron of the Queen’s Bays also was to assist with fire, and was to be prepared to support 22 Battalion on the left flank. Tasks were allotted to the mortars,

anti-tank guns, machine guns and engineers.38 From zero hour onwards artificial moonlight (searchlights) would be used over the battlefield.

On capture of the objective 5 Brigade was to consolidate, M10s were to take over from the tanks of 18 Regiment in 28 and 22 Battalions’ sectors, and 23 and 28 Battalions were each to release a company to support 18 Regiment, which was to be prepared to exploit at dawn to the bridge at the crossing of Route 9 over the Senio and establish a bridgehead over the river. For this purpose an Ark bridge, an armoured bulldozer and other mechanical equipment were placed under the regiment’s command. When a bridgehead had been established, 28 Battalion was to be prepared to cut Route 9 and protect the right flank. The 22nd Battalion was to continue its advance northward to the high ground south of Casale.

Sixth Brigade’s orders were for two companies of 25 Battalion to cross the Lamone by Hunter’s bridge and relieve two companies of 28 Battalion on the evening of the 14th. Other troops were to simulate a crossing south of Faenza. After 5 Brigade’s attack, the 6th was to adopt one of three courses. The first of these was for 25 Battalion to complete the crossing of the Lamone and prepare to take over 28 Battalion’s bridgehead, and for 24 Battalion to cross and, together with the 25th, to attempt to outflank Faenza; the second plan was for 6 Brigade to clear Faenza with Divisional Cavalry, 24 and 25 Battalions, if the enemy vacated the town; the third plan was for 6 Brigade to advance north-westwards from 5 Brigade’s bridgehead, if the enemy defended Faenza, while the Faenza Task Force took over on the right flank and assaulted the town.

A total of 256 guns39 on the New Zealand Division’s front and 180 on 10 Indian Division’s front were to be available for the attack. The barrage in support of 23 and 22 Battalions’ advance was to be fired by the three New Zealand field regiments and a regiment from 46 Division, and in support of 28 Battalion by two regiments from 46 Division. Other tasks for the field, medium and heavy guns were concentrations, counter-mortar fire, and pre-arranged defensive fire. In addition 290,000 rounds of Mark VIIIZ40

ammunition were released for the Vickers guns of 27 (MG) Battalion, two companies of which were to harass roads into Faenza and the known enemy positions, while a third company was to shoot with the artillery barrage and harass the ground over which the infantry was to advance.

The planning also provided for aircraft to attack defined targets and to co-operate with the ground forces. If the weather permitted, in fact, 5 Corps was going to do everything in its power to capture Faenza and cross the Senio River.

(vii)

At zero hour (11 p.m.) ‘to a second, the horizon behind us blazed with the flashes of the artillery. ... Looking back towards the gunlines you see the skyline dancing with flashes – fan shaped radiances from the decrested guns and the intense white spots of those whose actual muzzle flash is visible. They flicker back and forth so swiftly they leave you bewildered. ... The shells whizz overhead, not whining or whistling at this stage, but cracking in the air like whiplashes as they hurtle upwards towards the top of their trajectories. The air literally vibrates with the passing of each projectile and ... every loose shutter and window pane rattles continuously. Where the shells are bursting, if it is visible to the observer, he sees myriads of winking pin pricks of light, looking very small and insignificant, but in reality each one an expanding shower of deadly splinters. If the shells are bursting well ahead, the explosions all blend into an insistent rumbling like distant thunder or the boom of surf when heard inland from the beach. Even miles back from the barrage, the earth is continually shivering with tremors from the hundreds of explosions. ...

‘When the barrage lifts and begins to creep forward the infantry come to grips and then all the smaller signs and sounds begin. Wavering yellow flares hover briefly over the front, necklaces of tracer curve through the blackness, single red sparks of our own red recognition climb vertically, red globes of Bofors speed out and then slow down before finally winking out, haystacks here and there become lit and blaze brightly for an hour or so illuminating the smoke above them and then smoulder redly for the rest of the night. Pauses in the barrage are generally filled by the insistent chattering of the Vickers guns, and here and there at scattered intervals one hears the smooth even Burrrr of the spandau, nearly always followed swiftly by a short stutter of bren or the clicking of tommy gun. Grenades pop, tank engines are roaring, Jerry mortar and shellfire crunches down, and every now and then the giant retching

5 Brigade, 14–15 December 1944

of the Nebelwerfer is heard, followed by the moaning of rockets before they explode in rapid succession.’41

That was how the attack on the night of 14–15 December appeared to a New Zealander near the Lamone River.

(viii)

Lieutenant-Colonel Awatere’s plan for the Maori Battalion was to attack some houses within a triangular area between the railway (the branch line from Faenza through ‘Ruatoria’) and the road to Celle: C Company, on the right, was to capture Pogliano and another locality near the road parallel to Route 9; D Company (with a platoon of B under command), on the left, was to capture Casa Bianca and other houses north-east and north of Celle, and Villa Palermo (short of Celle); A Company, in support of C, was to seize buildings about midway to C’s objectives; B Company, in support of D, was to occupy houses near ‘Ruatoria’.

‘The great and unavoidable weakness of the Maori position ... was the lack of an axis road; on the right was the embanked railway line, but on the left the only road was in 23 Battalion’s area and that was useless until Celle was cleared.’ Awatere warned his officers that ‘the presence of enemy armour might influence the fortunes of the attack. Provided the tanks and anti-tank screen could get forward at the earliest possible moment, he considered the Maoris need have no fear of the outcome.’42

From the steeple of the church at ‘Ruatoria’ Awatere had a final look over the flat country towards Celle and Pogliano. Small, fallow paddocks were separated by single rows of mulberry and poplar trees, which in season would support the trellised grape vines. The rows of trees ran in the same direction as the advance and would have been no obstacle to the passage of tanks if the ground had been firm – but it was not firm. Awatere’s descent from the church tower was hastened by shells, the third of which brought down the whole structure.

When the attack began, two platoons of C Company had little trouble in approaching to within a few hundred yards of Pogliano; they waited in a small house near the railway for the arrival of the rest of the company before the start of the final assault. A patrol sent to investigate Della Cura, between the railway and Pogliano, crawled along a ditch until within a few yards of two Tiger tanks and some Germans. The Maoris had no suitable weapon for attacking tanks. Lieutenant Mahuika43 (who had taken charge

a few days earlier when the company commander was wounded), arrived with the other part of C Company, and called for stonks on Della Cura, but none fell on the target. The German tanks began to shell the building in which the Maoris were sheltering.

Meanwhile D Company sent two platoons (including the one attached from B) to Casa Bianca, and the other two to Villa Palermo, and by 2.30 a.m. held both places. At least 20 or 30 Germans were killed at Casa Bianca. German tanks could be heard moving along Route 9, and later a number of them appeared to be about to counter-attack from a road junction about half a mile north-east of Casa Bianca. Although the medium and heavy guns fired ‘murders’ and the field guns brought down several defensive stonks on this target, the Maoris, who were isolated and had no tanks or anti-tank guns at Casa Bianca, were compelled to withdraw to Villa Palermo when the enemy counter-attacked.

A Company discovered that La Morte, which had not responded to fire from C Company’s men when they passed it half-way to their objective, was occupied by the enemy, but captured it after negotiating a minefield. B Company took possession of the empty Case Ospitalacci, a short way along the road to Celle.

The Maori Battalion’s left flank was now on the ‘Ruatoria’–Celle road, but its right flank was most insecure. Mahuika decided to withdraw C Company. The men of 13 Platoon (Lieutenant Hogan44), told to go first, crawled along a ditch by the railway until they thought they could safely leave its shelter, but walked into a minefield. Some mines were exploded, and the enemy opened fire from the railway embankment; he was aided by the light of two haystacks which began to burn. Very soon there were not enough men to carry away the wounded. The survivors made for La Morte, though not sure whom they would find there; Hogan went forward alone and when within hailing distance identified himself in Maori. As La Morte was overcrowded, he took his men to Casa ‘Clueless’, near Case Ospitalacci. A party went back to bring in the wounded men who had been left behind.

Before 14 Platoon of C Company withdrew from the house near Della Cura, Mahuika was wounded, and Second-Lieutenant Paniora45 succeeded to the command. In the vain hope that the supporting tanks might arrive or that the enemy might depart, Paniora decided to stay. Two more German tanks joined the two at Della Cura, and after daybreak all four turned their guns on the house and blasted a corner off it. ‘An infantry attack ... then came in but

the range was suicidal and the survivors retired.’46 Paniora was killed and Sergeant-Major Wanoa,47 who next took command, decided that there was nothing to be gained by staying any longer with only a handful of men, so called for a smoke screen and defensive stonks, under which the survivors, carrying their wounded, safely reached Casa ‘Clueless’.

Villa Palermo and La Morte were now 28 Battalion’s foremost positions. The Maoris’ casualties during 14–16 December were 24 killed, 57 wounded, and two captured.

(ix)

The attack on Celle ‘brought to an angry head the feud between the senior officers of 18 Regiment and 23 Battalion that had been simmering since Florence.’48 This time the squadrons of the regiment were not under command of the battalions of 5 Brigade, but in support, ‘a change welcomed by squadron and troop commanders after their experiences at Florence and the Rubicon [Fiumicino]. Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas of 23 Battalion, in particular, was said to demand impossible feats from his tanks, forgetting that their crews were not superhuman or the tanks lightweights like jeeps.’49 Thomas and his company commanders, on the other hand, ‘felt strongly that the operation would have been more successful if the armour had been placed under command, as requested.’50

The battalion was required to advance about 2000 yards on a two-company front over broken, undulating ground on which the defences centred on houses. The plan was for B Company to attack on the right and C on the left; A Company was to follow 200–300 yards behind B and mop up posts bypassed by the leaders, collect prisoners, evacuate wounded, and if necessary assist in the final assault on the objective; D Company was to be in reserve and available to assist the tanks in the exploitation next day.

Before the attack began, 12 Platoon, which had entered the line 22 strong, came under severe tank and mortar fire, which reduced it to seven fit men; it therefore was replaced in B Company’s attacking force by 7 Platoon of A Company. The first shells of the barrage fell on 23 Battalion’s tactical headquarters – sited right on the start line – in a hilltop house which shook as it received several direct hits, but no casualties occurred among its occupants, most of whom sheltered in an underground cellar.

The battalion captured the houses more or less according to plan. On the right of B Company, 7 Platoon, after a brisk encounter, took 20 prisoners at its first house, half-way between the Celle road and Casa Colombaia, but was left with only enough men to guard the captives, so was replaced by 9 Platoon of A Company. The rest of B Company (10 and 11 Platoons) saw a surprising number of Germans on the Celle road. Some were already dead, killed by the barrage; the others were either shot or forced to surrender. Near Celle ‘the artillery and heavy mortars had wrought frightful havoc, but some determined enemy survived to give fight. B Company was now hard on the heels of the barrage. ... The softening-up process had its effect. ... Celle was occupied soon after 3 a.m.’51

The company commander (Major McArthur52) left 9 Platoon in Celle (which was a church with a few houses clustered around it) to hold the road junction, and pushed on with the rest of his force – about 28 men – to a cemetery, which they reached safely. Two Germans unsuspectingly sauntered down the road and were captured, but three enemy tanks and some infantry soon opened fire. McArthur left eight men (from 11 Platoon) to dig in at the cemetery and established a strongpoint with the remainder of his party at the northernmost house in Celle.

C Company, on the left, also made good progress. The officer commanding 14 Platoon was wounded at the start, but Sergeant Batchelor53 led the assault on the first house, Casa Colombarina, which was recognised as a strongpoint. The 10 Germans who survived were sent back with the walking wounded. Batchelor’s men took two more houses and were approaching the final objective when they heard two tanks close at hand and, as they were separated from the rest of the company, decided it would be wise to withdraw. They were surprised to find Germans in Casa Bersana, west of Celle, but promptly attacked and occupied it.

The shells of the barrage were still hitting the top storey of Casa Canovetta, south of Celle, when 15 Platoon attacked it. The first of two Piat bombs fired through the front door failed to explode but wounded the commander of 1 Battalion, 200 Panzer Grenadier Regiment; the second bomb exploded and shook part of the building. Some of the platoon dashed inside while others shot or captured the Germans who emerged. Thirty-nine prisoners were marched away; about a dozen dead or wounded Germans remained.

‘Thus, from house to house, the troops moved, losing a few

good men but rejoicing in the number of prisoners taken and in such a sight of dead Germans as few of them had ever seen before.’54 After taking 16 prisoners at one house 13 Platoon crossed open ground, where some of its men were pinned down by spandau fire from a slit trench. In the light of a burning haystack Private Litchfield55 stalked the gun, shot a German and took two prisoners.

A Company, reduced at this stage to 8 Platoon and Company Headquarters, passed a row of burning haystacks short of which some tanks of B Squadron of 18 Regiment were halted, and came under mortar, tank-gun and machine-gun fire, but managed to get into Celle and link up with B Company. A Company’s commander (Major Brittenden56) and Major McArthur decided to form a firm base in the church, where they found 9 Platoon.

By 4 a.m. on the 15th 23 Battalion had gained Celle but was still nearly half a mile from the final objective. At the cemetery just beyond the hamlet the eight men of 11 Platoon came under tank and machine-gun fire and, realising that they would be unable to fend off the tanks, withdrew to rejoin the rest of B Company in Celle. About this time Major Low57 was establishing C Company’s headquarters in Casa Camerini, on the road west of Celle, and his men also could hear tanks moving out in front. Tank-gun fire came from Casa Gessa, north of Celle, and the enemy appeared to be ready to launch a counter-attack. Both B and C Companies, therefore, called for tank support.

Batchelor (14 Platoon) set out from Casa Bersana with three men to find C Company headquarters, which he thought Low might have established at Casa Salde, farther north, but this house was still held by the enemy. Undeterred by or unaware of the occupants’ superior numbers, Batchelor and his companions attacked, killing five and capturing 19 Germans. Batchelor located the company headquarters at Casa Camerini. Shortly afterwards 15 Platoon was counter-attacked by German infantry supported by tank fire, but beat off the assault. Low ‘adopted the somewhat desperate expedient of calling down artillery fire on the house occupied by his own men in order to break up the worst counter-attack.’58

When word reached Battalion Headquarters that C Company had been counter-attacked and 11 Platoon forced back to Celle, Colonel Thomas ordered D Company forward to consolidate the

position between the hamlet and C Company, and went forward himself to investigate. D Company arrived about 7.30 a.m. to link up with the forward companies, and half an hour later four tanks from B Squadron of 18 Regiment also arrived. Two of the tanks took up a position behind B Company’s headquarters (in the church) and two behind a house occupied by a D Company platoon.

Second-Lieutenant Paterson59 took a section of D Company to the northern end of Celle, from which McArthur had withdrawn his B Company men. After 8 a.m. two German Mark IVs, accompanied by infantry, came down the road. Paterson’s men had no Piats or other anti-tank weapons with which to offer a fight. Some ran back into the hamlet, but five men remained flat on the floor of a house while armour-piercing shells penetrated the walls. One man, caught in the open, was captured. The enemy approached the centre of Celle, but was forced to ground by artillery concentrations and then withdrew.

As long as German tanks remained outside Celle, 23 Battalion could not feel secure. Colonel Thomas, who asked the B Squadron commander (Major E. C. Laurie) ‘to get his tanks forward, and later personally appealed to the tanks crews,’60 reported that ‘it was extremely disappointing that our tanks were not able to give battle.’61 Major Low also referred to their ‘most ineffectual and disappointing support. ... At no time did our armour move out to engage the enemy who was dive bombed both morning and afternoon and repeatedly stonked by Mediums and Field whenever we saw him move. ... Our troops, who had been halted by the tanks alone, were greatly disheartened at seeing German tanks advance, force back our right flank troops, withdraw and then manoeuvre throughout the day only 300 yds to 500 yds from our positions whilst our armour sat back evidently unable to compete.’62

It is debatable whether B Squadron could have contributed more to the battle by making greater sacrifices. Although 23 Battalion ‘felt somewhat aggrieved at not receiving more effective support from the tanks’,63 it was satisfied with its own performance in taking well over 100 prisoners, mostly from 200 Panzer Grenadier Regiment. One of the documents captured from the headquarters of a German battalion revealed that a relief had not been completed when the artillery barrage opened, which might account for the many dead found on some of the roads and tracks as well as in the

houses. Over 80 enemy were killed in 23 Battalion’s area. The battalion’s own casualties on 14–16 December were 12 killed and 48 wounded.

(x)

Of 5 Brigade’s three assaulting battalions, the 22nd (Lieutenant-Colonel O’Reilly), on the left, had the most difficult country to cross: to reach its objective west of Ferneto, in the vicinity of the road running westward from Celle, it had to descend into the valley of the Ianna stream, climb the steep ridges on which stood Casa Ianna and Casa Elta, and descend again to the Camerini stream, beyond which the ground rose once more. Casa Elta was a two-storied farmhouse on a spur flanked by steep gullies and protected by many well-placed machine-gun posts and thickly-sown minefields; Casa Ianna was in a similar position about a quarter of a mile to the east.

The advance began with A Company on the right and C on the left, supported by D and B respectively. The enemy reacted almost immediately to the barrage with artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire. The right-hand platoon of A Company (No. 7) suffered so many casualties, first from shellfire and then in a minefield, that its place had to be taken by the reserve platoon (No. 8). The left-hand leading platoon of A Company (No. 6) passed safely through an undetected minefield in front of Casa Ianna and was in possession of the house by 3 a.m. Corporal Clark64 silenced a spandau post with hand grenades and tommy-gun fire. The platoon set alight the nearby haystacks, which drove out the enemy who were occupying pits underneath, and altogether captured 17 Germans.

As radio contact had been lost with A Company early in the attack, 16 Platoon was sent from D to follow A and keep in contact with C on the left by radio. This platoon found A Company in possession of Casa Ianna, and the rest of D was then guided to the house. The two companies investigated other houses in the vicinity and, while D was left in occupation, A went on to Sebola, near the Camerini stream, which brought it into line with 23 Battalion on its right.

Casa Elta did not fall to C Company until 4 a.m. The left-hand platoon (No. 15) lost its officer, who was wounded on the start line, and two sergeants, killed in minefields. The platoon split into small groups, one of which, led by Private Dixon,65 captured two defended localities, took a few prisoners, and joined in the assault

on Casa Elta. The other two platoons of C Company (13 and 14), which had fewer casualties but also lost touch and became scattered, converged independently on the house. One group was held up by machine-gun fire until Private McIvor66 stalked a spandau post and silenced it with his tommy gun, and then wiped out a second spandau post with a grenade when his weapon jammed. Lance- Sergeant Seaman67 led a party uphill on the left flank and around to the rear of the house, where he rallied his men before leading a charge into the strongpoint. Although severely wounded, he refused aid until he had disposed his men against counter-attack. About 20 Germans were captured and 15 killed, and seven machine guns were among the equipment seized.

B Company, having passed through C Company’s area before the capture of Casa Elta, climbed a steep ridge slightly behind and to the west of it, and had casualties while the men were silhouetted on the skyline by the artificial moonlight. After a sharp engagement the company captured Casa Mercante, which yielded 40 prisoners, soon after dawn. Five tanks from A Squadron of 18 Regiment helped to consolidate.

There was no threat of a counter-attack on 22 Battalion’s front, where a quiet day ensued, marred only by the bombing and strafing of Battalion Headquarters by ‘friendly’ aircraft in the afternoon. As well as killing many of the enemy, 22 Battalion had taken over 100 prisoners, most of whom were from 361 Regiment of 90 Panzer Grenadier Division. The battalion’s own casualties were seven killed and 30 wounded.

(xi)

The members of 23 Battalion who were so critical of the support given by 18 Armoured Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel J. B. Ferguson) probably had little idea of the appalling difficulties the tank crews had to contend with that night.

Half of A Squadron had been placed in support of 28 Battalion and half in support of the 22nd; the whole of B Squadron was in support of 23 Battalion because Celle was expected to be strongly defended and German Mark IV and Mark VI (Tiger) tanks had been seen there. The New Zealand tanks were expected to be on the objectives with the infantry at daybreak, about 7 a.m.; then C Squadron, with infantry following the tanks, was to go through and charge the Senio River crossing. ‘This idea had a suicidal sound about it. ... However, C Squadron could drag some

comfort from the news that, as soon as it was light enough, the Air Force was to lay on a massive assault with all the planes it could produce. ...

‘Celle ... looked a potential bottleneck, for 28 and 23 Battalions’ tanks would all have to go that way before fanning out to join the infantry. It was on C Squadron’s road forward too. More than that, the whole regiment had only one road to move up, and a mere lane at that, winding up and over a [Ragazzina] ridge and diagonally down to the flat below, then coming out on to another road that ran dead straight for Celle church. Those who had been up to the top of the ridge for a cautious look reported that this lane (what they could see of it) looked churned up and exposed and generally undesirable.’68

Both B Squadron, which went first, and A Squadron began badly. The troop of tanks leading up the Ragazzina ridge, west of ‘Charing Cross’ (known to the Maoris as ‘Ruatoria’), ‘was at once caught in a torrent of shells, apparently ours.’69 An officer was killed, a tank was damaged, and it was some time before any could move. Another B Squadron troop took a wrong turning and had to back along a narrow road. A Squadron’s commander (Captain Passmore70) was wounded, and when a 17-pounder tank was hit and went over a bank, three of its crew died. The tanks edged around a large crater in the road half-way up the ridge, and slowly groped ahead in single file, while their commanders, despite the shellfire, walked ahead to show the way. They kept strictly to the lane because the fields were boggy and mined.