Chapter 8: The Winter Line

I: The Offensive Abandoned

(i)

IT was still Fifteenth Army Group’s intention that Eighth Army should cross the Senio River and Fifth Army strike towards Bologna. The date for launching the attack had not been settled, but the opinion was growing at Eighth Army’s headquarters that, with the exhaustion of its troops and the heavy drain on its reserves of ammunition, its contribution to a combined offensive could be only on a limited scale.

General McCreery wrote to General Clark on Christmas Day asking that the timing of the two-army attack be reconsidered. He pointed out that Eighth Army’s fighting during the last half of December had used half a million rounds of 25-pounder ammunition, and the availability of only 612,000 rounds during the next five weeks would not permit a major operation other than the forcing of the Senio and advance to the Santerno. The original target date for the attack by Fifth Army was to have been on or about 7 December. The three weeks of fighting which Eighth Army had completed since then had reduced by that length of time its capacity to conduct a simultaneous offensive with the Americans. Consequently, if a joint attack were launched, Eighth Army’s effort possibly might be expended by the time Fifth Army most urgently needed assistance.

Meanwhile planning went ahead for 5 Corps’ attack: in the first phase the New Zealand Division on the right and 10 Indian Division on the left were to establish bridgeheads across the Senio, and in the second they were to link in a firm corps bridgehead; they were then to advance northward or north-westward to the Santerno River. The 56th Division, which was to protect 5 Corps’ right flank and be prepared to relieve New Zealand troops on both

sides of the Senio, was ordered to advance to the river as rapidly as possible. An adequate roading system was to be constructed for the Indian division, and a conference to co-ordinate the objectives of the Indian and New Zealand divisions was held on the morning of 27 December. In General Freyberg’s opinion this ‘wasted a lot of time. ... All plans put forward were found to founder in the ammunition shallows.’1 It was no surprise when Corps advised the New Zealand Division in the evening that the attack across the Senio was cancelled.

A German offensive launched on Fifth Army’s front on the 26th disrupted the Americans’ deployment for the two-army attack. It had become evident shortly before Christmas, Field Marshal Alexander later wrote, that the enemy was planning an attack down the valley of the Serchio River, which debouches into the Arno basin at Lucca, near the west coast. ‘There had been no activity on this front for a very long time, since it was quite impracticable for the Allies to attempt a crossing of the mountains at this point; and for this reason it had been treated by both sides as a quiet sector. ...’2 It was lightly held by 92 US Division, a Negro formation.

By the evening of the 27th the German 148 Division and troops of the newly-formed fascist Monte Rosa and Italia divisions had penetrated five miles down the valley. An attack by a force of this size might not have been serious, but 10 days earlier the enemy had launched his vastly greater Ardennes counter-offensive on the Western Front, and the possibility of a similarly desperate effort in Italy could not be ignored. If the enemy could exploit across the Arno River and seize Leghorn, ‘it would be a major disaster for the whole Allied front since through that port came all the supplies for Fifth Army and in its neighbourhood there were very large dumps of military stores.’3 Therefore 1 US Armoured Division and two brigades of 8 Indian Division were diverted to the threatened sector, and by the end of the month had completely restored the situation. On the 28th, however, General Truscott ordered ‘a further postponement of planned operations pending clarification of the situation on the west flank.’4

Although Fifth Army had had comparatively little fighting in the last two months, its shortage of ammunition was almost as serious as Eighth Army’s because reduced allocations to the Italian theatre had prevented the accumulation of a substantial reserve.

Consequently Field Marshal Alexander, realising how very poor were the prospects of reaching Bologna that winter, decided on 30 December to abandon the plan for the Allied offensive and ‘to go on the defensive for the present and to concentrate on making a real success of our Spring offensive.’5

(ii)

Two days before this decision was reached, 5 Corps had advised the New Zealand Division that there would be no attack across the Senio before 7 January. General Freyberg presented a short-term and a long-term policy to an orders group conference on 28 December. He said that if Fifth Army attacked there would be two operations on Eighth Army’s front: the Canadian Corps was to clear out the pocket of enemy still east of the Senio, and at the same time 10 Indian Division was to cross the upper reaches of the river. The 43rd Gurkha Brigade was to pass from the New Zealand Division to 10 Indian Division. The chance of the New Zealand Division participating in the Indian Division’s operation might occur four days later (not before 11 January).

The short-term policy was one of holding the ground already gained until it might be necessary to regroup and push a brigade through to occupy a position on the flank of the Indian division and burst out west of Castel Bolognese. The GOC described the Division’s disposition for defence against counter-attack. ‘Nobody can tell but the enemy may be encouraged by the move of divisions to Greece and the knowledge that there is very little behind us, to have a go at Faenza.’6 Each of the two infantry brigades would have two battalions in the line; the 5th also would have one battalion at Faenza and one at Forli, and the 6th two at Forli. The reserve group, Campbell Force, was to protect Faenza and the gun positions north-west of the Lamone River, and was to link up with 6 Brigade; it might be required to hold on the line of the Scolo Cerchia if the enemy counter-attacked from the ‘Senio pocket’. Although the Division was on the defensive, the GOC insisted that ‘we should be offensive on the patrolling front and use our tanks.’7

Sixth Brigade continued to patrol the approaches to the Senio and gather information about the German defences and the river. A raid early on the morning of 27 December on a house occupied by a platoon of 26 Battalion had been repulsed without loss except to the enemy. ‘The upstairs pickets had hardly had time to give the others warning of the Germans’ approach before three bazooka

The Italian front, 31 December 1944

bombs exploded inside the building. This was the signal for the enemy to rush the back door, but two men on duty there opened fire and killed the leading German. Everyone inside the house was firing by this time and the Germans were forced to vacate their positions near the house. Grenades were tossed into the out-buildings, and the whole area was brought under intense LMG fire which induced the enemy to retire.’8 A quickly laid artillery stonk caught the Germans as they recrossed the stopbank. ‘Subsequently it was learned that the patrol consisted of 45 men, equipped with blankets and spare ammunition; its intention had been to occupy the house as a strongpoint. The stonk had caused many casualties.’9

Divisional Cavalry Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel N. P. Wilder) relieved 26 Battalion in the late afternoon and evening of the 27th, and was told that the enemy protected his front with minefields and occupied the near slope of the stopbank. The 26th had been making use of trip flares and listening posts, and it was essential to have tanks in the area. The following afternoon and evening 25 Battalion was relieved by the 24th, which took over the positions along the line running approximately south-eastwards from La Palazza through San Pietro in Laguna.

On the night of the 26th–27th 28 (Maori) Battalion completed the relief of 22 Battalion in 5 Brigade’s southern sector. The 2/6 Gurkhas of 43 Brigade, whose patrols had clashed with the enemy in the vicinity of Route 9, were relieved on 29 December by two companies of 23 Battalion, which came under 21 Battalion’s command until that battalion was relieved by the 23rd next day. The 21st then took over 23 Battalion’s role with Campbell Force in Faenza. Replaced by 19 Armoured Regiment (less a squadron in close support of the infantry in the vicinity of Route 9), 18 Armoured Regiment went back to Forli.10

Forli, the B Echelon town about seven miles from Faenza, ‘half ruined and bulging at the seams with a very mixed collection of soldiers, was no more attractive than Faenza. It was the same flat, ugly industrial town. Certainly there were more ways of killing time there. There was a NAAFI canteen and a picture theatre, both always overcrowded with Tommies and Kiwis. ... There were

New Year parties, farewell parties for the “old hands” leaving for New Zealand, and parties to celebrate nothing in particular except the existence of a big wine factory up the road, full of stocks that needed drinking up before they got too old or someone else beat you to them. There were occasional dances ... for, unlike Faenza, this place was full of civilians. But all these pleasures had no sparkle. Outwardly and inwardly, this was the depth of winter indeed.’11

The engineers ‘carried on with the never-ending task of keeping communications open in spite of snowstorms, frozen slush and thaws.’12 In 10 Indian Division’s sector 7 Field Company, assisted by an Indian pioneer company, widened and metalled a road along a ridge near Pideura and formed a way down towards the Senio River. This was known as Armstrong’s track because of the work done by the Mechanical Equipment Platoon13 under Captain Armstrong.14 The track was in view of the enemy-held village of Cuffiano and therefore had to be constructed at night and carefully camouflaged with netting before daybreak.

(iii)

Although the offensive had been abandoned for the winter, it was still necessary for Eighth Army to secure a line which could be readily defended and which would serve as a jumping-off place for the spring offensive. This line, on both 5 Corps’ and the Canadian Corps’ fronts, became ‘inevitably, and not disadvantageously,’15 the Senio River, which was scarcely half the size of the Lamone, the Savio and other water obstacles already crossed.

The enemy, according to information gathered by Intelligence, had seven battalions east of the Senio, of which five or six were on the New Zealand Division’s front. An attack by 6 Brigade to the north probably would meet at least three battalions with an average strength of 200 men.

General Freyberg told General Keightley on 30 December that he thought ‘it should be a big crack. I think 56 Div should come in with us,’16 and also that the attack would use a good deal of ammunition. Keightley replied that he would be pressed by the Army Commander to use as little ammunition as possible, and

suggested using tanks as much as possible; he also wanted to choose a day when the Air Force would be able to give its support. Freyberg conferred with Brigadiers Parkinson and Queree, and then told Keightley, ‘There is a body of opinion that we should waste as little time as possible, start tomorrow and use tanks. The amount of ammunition required will be 2000 to 3000 rounds.’ The corps commander agreed to this, and the GOC concluded: ‘We shall go ahead then, and test the market.’17

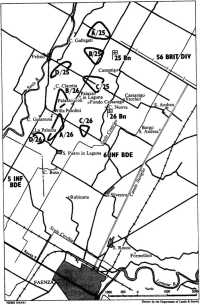

Patrols sent out by 24 Battalion during the night of 30–31 December met no enemy, and before daybreak the battalion and tanks of A Squadron, 20 Regiment, without opposition, occupied houses half a mile or so north-east and north of San Pietro in Laguna. Fine weather during the day permitted the Air Force to attack many targets close to the enemy’s forward positions, including houses just across the river from Divisional Cavalry Battalion. Probably because of this fighter-bomber activity 6 Brigade had a quiet day.

After hearing of 24 Battalion’s gains early in the morning, the GOC told the corps commander that he considered the enemy could be expelled from the north without any trouble, but would continue to hold a bridgehead east of the Senio until forced out; he also said, ‘we can’t go to the north and then go to the south afterwards. If they say the latter is on I would rather stay where I am.’18

It was decided to continue northward. Orders were issued in the afternoon for the Division to be prepared to clear the enemy salient east of the Senio in conjunction with an attack southwards by the Canadian Corps. Sixth Brigade was to be directed on Cassanigo (beyond the Sant’ Andrea – Felisio road), and 5 Brigade was to be responsible for the protection of the left flank; 56 Division was to advance northward in conformity with 6 Brigade’s right flank.

The CO of 24 Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Hutchens) held a conference on New Year’s Eve to define the battalion’s objectives and the artillery, mortar, machine-gun and tank support. It appeared at the time that all enemy vehicles and heavy weapons had gone back across the Senio and only an infantry screen had been left on the battalion’s front.

The sounds of revelry as the enemy celebrated the New Year were heard on many parts of the front. While waiting for the start of their attack, the 24 Battalion men ‘witnessed a really splendid sight. ... along the whole front, as far as the eye could see, streams of tracer bullets, light anti-aircraft shells and coloured flares weaved across the midnight sky.’19

The 24th Battalion’s advance, in bright moonlight, necessitated a swing round of its front from north-east to north-west. On the left flank, therefore, 7 Platoon of A Company had the shortest distance to its objective at Casa Galanuna, about half a mile along the road from La Palazza to Felisio. The platoon came under fire from Galanuna and also from Villa Pasolini, near the road junction about a quarter of a mile away, but captured eight or nine Germans and killed and wounded others, at a cost of six men wounded. Apparently the enemy at Galanuna was caught during a New Year party, for which food and wine were set out on a table with a Christmas tree in the centre.

While advancing towards Villa Pasolini, B Company came under severe machine-gun fire about 300 yards from its objective. Four men were killed and three wounded, one of them mortally. The company commander (Captain Pirrie20) consulted Battalion Headquarters and was ordered to withdraw.

D Company also ran into trouble. When 17 Platoon was within 30 yards of its objective, a house about 200 yards short of Palazzo Toli, the enemy, who was dug in in front of the house, opened fire in a semi-circle. The platoon was compelled to retire; it brought out six wounded men and left three dead. Meanwhile 18 Platoon rushed Palazzo Toli (600 yards north-east of Villa Pasolini) and gained possession, but was practically surrounded and in a precarious position. Accompanied by tanks of A Squadron, 20 Regiment, 16 Platoon moved in close and opened fire with all weapons, which forced the enemy either to lie low or withdraw while 18 Platoon, carrying its wounded on improvised stretchers, evacuated the house.

When it became evident that the attack had failed, 7 Platoon was withdrawn from Casa Galanuna, and before dawn on New Year’s Day the whole of 24 Battalion was back in its former positions. Brigadier Parkinson reported to the GOC that the enemy ‘was in every place we attacked. He was expecting an attack.’21 The 24th Battalion had had eight men killed and 20 wounded and had taken eight prisoners and killed ‘a good few’. The GOC told the corps commander how the battalion had been opposed, and said, ‘I am very much against these little attacks which don’t succeed.’22

Meanwhile 25 Battalion had relieved two companies of the London Irish of 167 Brigade, 56 Division, and placed two of its own companies in the line on the right of 24 Battalion. The two battalions rearranged their dispositions on the night of 1–2 January

so that each had two companies forward, one in immediate reserve and one farther to the rear. The same night 5 Brigade side-stepped to the right (north) when a battalion from 10 Indian Division replaced 28 (Maori) Battalion in the sector south of Route 9, and the Maoris took over from Divisional Cavalry (which went back to Forli) north of the railway. The 23rd Battalion continued to hold the sector astride the railway and highway.

By the afternoon of 2 January it was obvious that the enemy had gone from his positions immediately to the north. The London Irish, on 6 Brigade’s right, reached the crossroads near Cassanigo Vecchio (about half a mile south of Cassanigo) without opposition. South of the Sant’ Andrea – Felisio road, 25 Battalion discovered that Casa Nuova and Fondo Cassanigo were unoccupied, and 24 Battalion found only two or three stray Germans at Palazzo Toli. Next day 25 Battalion took Palazzo in Laguna and 24 Battalion Villa Pasolini, a nearby wine factory and Casa Galanuna, all of which had been vacated by the enemy.

The commander of 1 Canadian Infantry Division (Major-General H. W. Foster) had discussed with General Freyberg timings and other details of attacks by the two divisions to clear the enemy from the pocket between them. A plan was decided upon for 6 Brigade to continue its northward advance, but later this was cancelled, and on 3 January the GOC told a divisional conference that 56 Division would try to push the enemy out of his salient east of the Senio and thus link up between the New Zealanders and Canadians.

In case the enemy should attempt a counter-attack, which Freyberg thought might be possible, the New Zealand Division had taken ‘completely adequate defensive measures. There are 100 tanks distributed in depth right back to Forli; also plenty anti-tank guns. If we wanted him to do his war effort harm we would want him to come in on our position here. If we are properly prepared and our plans are co-ordinated then he will take a pretty hard knock. ...’23 The Division’s policy, although defensive, was to make the enemy’s tenure on the near side of the river as unpleasant as possible, but the ammunition supply was getting ‘tighter and tighter every day.’24

(iv)

The enemy was still holding on the south-eastern side of the Senio River in two places, north of Ravenna (which the Canadians

had captured on 4 December) and south of Bagnacavallo. He would have to be cleared from both before Eighth Army could establish a satisfactory winter line.

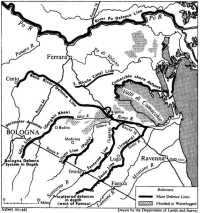

The more northerly of the enemy’s two salients covered the southern shore of the Valli di Comacchio, the great lagoon near the coast, which gave him a potential base from which to launch an attempt to recapture Ravenna. By cutting the embankments of the Comacchio on one side of Route 16 and the high banks of the Reno River on the other, he had flooded wide areas west of the lagoon and thus created a narrow and easily defensible defile through which the highway passed at Argenta, 15 miles beyond Alfonsine (where Route 16 crosses the Senio, which flows into the Reno).

The possession of the southern shore of the Valli di Comacchio by Eighth Army would make it possible to launch flanking amphibious attacks in support of an advance along Route 16 through the ‘Argenta Gap’ when the Allies resumed the offensive. This could be an alternative to the succession of frontal assaults on the numerous river lines which would have to be faced in a westward drive farther inland; in any case it could accelerate the advance. The German High Command was aware of this possibility. General von Vietinghoff was told not to regard the Valli di Comacchio as impassable terrain where he could economise in deploying the troops of Tenth Army. The Allies had employed amphibious vehicles with success in Belgium and Holland, but apparently the enemy did not know of the shortage of such equipment in Italy.

In five days (2–6 January), when the frozen ground allowed tanks to be used with greater freedom, 5 Canadian Armoured Division, with strong support from the Desert Air Force, advanced to the Reno River (the northern bank of which lay close to the shore of the Valli di Comacchio) and the Adriatic coast, and in the process so alarmed the enemy that he made a violent and costly counter-attack. The Canadians took 600 prisoners, killed 300 enemy and wounded many more; their own casualties were less than 200.

At the same time 1 Canadian Infantry Division and 56 Division of 5 Corps eliminated the other German salient, between the Senio River and the Naviglio Canal south of Bagnacavallo. It had been decided that 5 Corps’ forces already north of Route 9 between the Lamone and the Senio had little prospect of overrunning the enemy by the methods already employed. A fresh approach presented itself, however, when frost hardened the ground so that tanks could cross it and avoid the thickly mined roads, and a new type of equipment, the Kangaroo, could be tested. Turretless tanks modified to carry infantry, the Kangaroos were ‘designed to enable them to accompany tanks across country swept by bullets and

artillery fire and arrive together on their objectives.’25 They had not been used in the Italian theatre. The success of the project would depend on its completion before a change in the weather started a thaw.

The Canadians made a diversionary sally to the Senio stopbank west of Bagnacavallo, on the northern side of the German pocket, in the afternoon of 3 January. Before the noise of this had died down, they began an assault across the Naviglio Canal at Granarolo (half-way between Bagnacavallo and Faenza), and by daybreak had secured the village and reached the Fosso Vecchio about half a mile beyond it.

Fifth Corps began its attack early on the morning of the 4th, and ‘the whole plan worked with extraordinary smoothness.’26 Accompanied by the Kangaroos (a squadron of 4 Hussars) carrying infantry (2/6 Queens), 7 Armoured Brigade, under 56 Division’s command, passed through 24 NZ Battalion and set out from La Palazza on a mile-wide sweep along the bank of the Senio. To mop up the enemy cut off by this ‘left hook’, 167 Brigade advanced north-eastward farther to the right. Bombing and shelling almost silenced the enemy’s artillery, and the new method of attack took him by surprise. By midday 167 Brigade had made contact with the Canadians at the Fosso Vecchio, and before the end of the day the east bank of the Senio was clear as far as San Severo, between the river and Granarolo. That night the enemy gave way all along the front. The Canadians crossed the Naviglio north of Granarolo and on 5 January reached the Senio opposite Cotignola. At a cost of few casualties, 56 Division had taken over 200 prisoners and the Canadians well over 100; many Germans had been killed or wounded.

To conform with 56 Division’s northward advance, 6 NZ Brigade redisposed its troops to face the Senio on the night of 5–6 January; this brought 25 Battalion up on the right of the 24th.

II: Offensive Defence

(i)

When reporting on 8 January 1945 to the Combined Chiefs of Staff on his decision to go on to the defensive for the time being and to concentrate on making a success of an offensive in the spring, Field Marshal Alexander explained why he had modified his previous intentions and plans: Eighth Army had not been as

successful as had been hoped because of the difficulties of terrain and weather; the enemy had developed his defences round Bologna into a strong fortress area, from which Fifteenth Army Group would be unable to drive him in winter with the forces available; the enemy had formed a reserve of four divisions to meet an Allied offensive or launch a counter-offensive, while Fifteenth Army Group was unable to create an equivalent reserve; Eighth Army was in urgent need of re-organisation, for which some divisions would have to be withdrawn from the line; the artillery ammunition available to Fifteenth Army Group would allow an offensive for only about 15 days. ‘If that period was to be extended, I should be unable to carry out my primary mission; indeed, until stocks could be built up again, Fifteenth Army Group would be unable to follow up an enemy withdrawal with any chance of a decisive success.’27

Alexander had decided, therefore, ‘to pass temporarily to offensive defence in Italy. I intend to carry out minor offensive operations in order to keep the enemy on the alert and improve our positions. Plans will be made for the resumption of the offensive and will be concerted with Eisenhower.’28

By this time the enemy was on the line of the Senio River along the whole of Eighth Army’s front except near Alfonsine, on Route 16, where he continued to hold a small but strong salient east of the river. He had reacted to the Canadian Corps’ drive towards Valli di Comacchio by strengthening his Adriatic flank. By the middle of January he opposed Eighth Army with what amounted to eight and a half divisions; at the beginning of December he had had only six.

General McCreery held a conference of the corps commanders of Eighth Army on 9 January to discuss the possibility of an enemy counter-attack and to lay down a defensive policy. An attack down the axis of Route 16 might result in the loss of Ravenna and permit the enemy to continue to Forli, cut Route 9 and close Route 67, but the German reserves appeared to be too weak to arouse anxiety over this possibility. The policy decided upon, therefore, was to defend the existing line and prepare to resume the offensive.

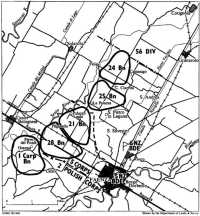

Already General Keightley had ordered the divisions of 5 Corps to prepare their positions nearest to the Senio as forward defended localities, to lay minefields and wire, and to prepare the bridges on the Lamone River and farther west for demolition. The corps’ intention was to hold a defensive position along a line east of the Senio with 56 Division, 2 New Zealand Division, 10 Indian Division

and 5 Kresowa Division (from the Polish Corps) from right to left in that order. The divisional commanders were to decide when they could finally clear the enemy from the eastern bank of the Senio, and in the meantime were to keep a sufficient reserve forward of the Lamone to be able to resist a German attack for 24 hours without additional support. A corps reserve of an infantry brigade and an armoured regiment was to be ready to go to the threatened sector if an attack developed.

The corps was to prepare for the resumption of the offensive by continuing the construction of roads, and by allowing as many troops as possible to rest and train. Defensive works were to be hidden and dummy tracks, leading towards the river where no crossing would be attempted, were to be built in full view of the enemy.

Headquarters 2 Polish Corps was withdrawn on 7 January, and 5 Kresowa Division, complete with its supporting arms, the Army Group Polish Artillery and other Polish units passed to the command of 5 Corps, which thus became responsible for the left sector of Eighth Army’s front. At the same time the corps’ right boundary was moved northward along the Senio to about a mile south of Cotignola. The New Zealand Division, whose units south of Route 9 already had been relieved by 10 Indian Division, took over the left of 56 Division at Felisio, and the 56th replaced the Canadians on the right of 5 Corps’ front, which was now about 17 miles long. The corps had the equivalent of five infantry brigades in the line, a sixth in reserve, and the rest of its troops resting in rear, ready to move up again at 48 hours’ notice.

The 56th Division, two brigades strong, was responsible for a relatively narrow sector on the right, while the New Zealand, Indian and Polish divisions occupied progressively broader sectors in the centre and on the left. The troops in reserve, quartered around Forli or farther back near Cesena, were in country which closely resembled that which Eighth Army would have to cross when it resumed the offensive; they were able to train, therefore, in realistic circumstances, and were close enough to the front to hurry back if the enemy attempted a counter-offensive.

Civilians, reluctant to leave their homes, were evacuated from localities overlooked by the enemy, from buildings housing headquarters, and from a zone about 3000 yards deep behind the main defences. This was justified on humane grounds as well as those of security, because the enemy’s guns and tanks systematically destroyed all houses and farm buildings which might be used as strongpoints and observation posts. The Italians still in Faenza were not compelled to leave, but no more were allowed to enter

the town. A few contrived to stay in the forward zone, but most were evacuated; they made off slowly in long columns of trucks and farm carts. The New Zealand Division provided transport to assist in the removal of an estimated 1000 people and 500 cattle, as well as rabbits and other animals, from its sector.

Snow began to fall in the afternoon of 6 January and continued at intervals next day, covering the ground to a depth of about six inches. After a heavy frost the snow was frozen hard, which made silent movement on it almost impossible. Frosty nights and fine cold days followed until towards the middle of the month, when there was a spell of rain and misty weather, which in turn was succeeded by more frosty, fine weather during which the thaw reduced the roads to a very bad state. Daybreak on the 25th unexpectedly revealed a fresh snowfall four or five inches deep, but this also began to thaw.

There was little activity on the front. The enemy did not relax his hold on the stopbanks on both sides of the Senio, but showed no sign of launching an attack. North of Route 9, where the high stopbanks dominated the surrounding country, 56 Division and the New Zealand Division occupied positions about 500 yards from the near bank and based on houses and farms which they converted into strongpoints with mines and wire. Although white snow suits were worn, it was virtually impossible to reach the river in daylight, and although patrols did occasionally penetrate to the stopbank at night, they were unable to stay there.

South of Route 9 the stopbanks were comparatively low, vanishing altogether in some places, and therefore did not dominate the countryside. Immediately south of the highway the enemy still held positions east of the river, while farther south, towards Tebano, 10 Indian Division had control of the near stopbank and had outposts on the river line; farther upstream, beyond Tebano, the Indians were able to patrol across the river because the main German positions were on rising ground and only outposts remained in the river valley. On 5 Kresowa Division’s front, on Eighth Army’s extreme left, where both sides occupied high ground some distance from the banks of the Senio, the Poles patrolled deep into no-man’s land.

(ii)

The New Zealand Division held its sector, which extended about 6000 yards north-eastwards from just south of Route 9, with 6 Brigade on the right and 5 Brigade on the left, and with an ad hoc brigade group in Forli as divisional reserve. Each of the two

forward brigades had two battalions in the line and one in reserve at Faenza; they had under command an armoured regiment, an anti-tank battery (with 17-pounders and M10s) and a machine-gun company, and in support a 4.2-inch mortar battery and a field company of engineers. The divisional reserve consisted of Headquarters 4 Armoured Brigade, two infantry battalions, an armoured regiment, an anti-tank battery and 27 (MG) Battalion less two companies. The artillery and engineers functioned under the centralised command of the CRA and CRE respectively. Tank support for 5 Brigade was provided by 19 Regiment and for 6 Brigade by the 20th, each with one squadron close to the forward infantry, one on a gunline, and one in reserve. From time to time the infantry battalions changed places so that each in turn had a spell in the line and in reserve at Faenza or Forli. The tank squadrons exchanged positions in each regiment, and the anti-tank batteries and machine-gun companies were relieved the same way.

The defences were organised to withstand or repel a major attack. To cope with the possibility of an enemy penetration, 6 Brigade was to be prepared to attack northwards from Faenza to recapture the San Silvestro – Sant’ Andrea area, and 5 Brigade westwards to recapture Celle and the high ground between it and the Senio. In case the enemy should succeed in penetrating so far, defences were based on the Scolo Cerchia for the protection of Faenza and the bridges in the vicinity.

The patrolling policy was to dominate the near banks of the Senio, discover and clear gaps in the minefields, and reconnoitre enemy defences and possible crossing places of the river. The enemy outposts were alert and sensitive to the movement of patrols and working parties; the enemy also patrolled vigorously. The following incidents typify this activity.

Early one morning the Maori Battalion saw some Germans heading towards Palazzo Laghi from the river, and sent a patrol to investigate. The patrol brought back six prisoners, who were interrogated by two Jewish officers (attached to 28 Battalion for experience). The Germans had been sent out to take prisoners, and had gone to Palazzo Laghi unaware that Allied troops were in the vicinity. They were expecting a runner at 6 p.m. with news of their relief. The Maoris waited for the runner and enticed him into captivity by using the German codeword. He had orders for the German patrol to return to its headquarters, so the Maoris pretended to be that patrol with the object of reconnoitring the river for crossing places. Seven of them set off towards the stopbank, but they were met by small-arms fire and forced to withdraw with three wounded.

One evening three Germans, whose snow clothing was said to be so white that it could be easily detected, appeared with a dog in front of a house occupied by a platoon of 23 Battalion near the railway. When the New Zealanders engaged these men, another enemy party, estimated to be six strong, opened fire with automatic weapons at close range. They were all driven off by machine-gun and mortar fire.

A standing patrol from 26 Battalion at Galanuna was attacked next evening by eight Germans wearing white clothing and snowshoes; they gained a foothold in the outbuildings and fired a bazooka and grenades at the house, but were repelled by artillery, mortar, machine-gun and small-arms fire, which wounded three of them.

Three men dressed in snow clothing approached at night to within 100 yards of a Vickers platoon’s gunline near San Pietro in Laguna, but retired when challenged. The enemy reappeared about two hours later, but again withdrew after exchanging small-arms fire with the machine-gunners. In their flight they set off a trip flare, which attracted fire from other troops in the neighbourhood. At dawn two bazookas and a Schmeisser29 were found abandoned near the machine-gunners’ position.

This was one of several small German patrols armed with bazookas (or Panzerfausten) which approached the Division’s lines about this time; it was thought their object was primarily to reconnoitre, but they also were to attack any good target that offered. Usually they were chased away before they could do any damage.

A patrol from 26 Battalion set out before daybreak on 29 January for the stopbank west of Casa Claretta. Three men, covered by the others who stayed at a demolished house nearby, went on to the bank, but were conspicuous in their white clothing on the snow-free crest and were forced off by small-arms fire.

A patrol from 23 Battalion, with the intention of ambushing the enemy, set out one evening to cross the river near the railway, but found a dannert-wire fence on the far side of the stopbank, which dropped steeply to the ice-covered water, 25 to 30 feet wide. The patrol, which had brought with it two 15-foot ladders, did not try to cross.

A patrol from the Maori Battalion made three attempts one night to reach the stopbank from Palazzo Laghi, but encountered minefields and machine-gun fire and was compelled to withdraw each time. The following evening another Maori patrol, probing its way and crawling through a minefield, arrived at the stopbank a little farther upstream, went along the bank to the bend in the river

north of Palazzo Laghi, and reported that the watercourse was 30 to 35 feet wide and about five feet deep. The exploding of two mines, of which there were many on the bank, was the signal for German machine guns to open fire. The Maoris fought the enemy on the opposite side of the bank with grenades before withdrawing under covering fire.

(iii)

‘Last night’s fog carried a very unusual noise into our lines from the enemy side of the river – the sound of a train,’ stated the divisional Intelligence summary on 15 January. Reports from 5 Brigade suggested that the noise, which was heard on four or five nights, came from the railway between Castel Bolognese and Solarolo, roughly parallel with the Senio and behind the German front. Men of 22 Battalion claimed that twice before midnight on the 15th they heard ‘the sounds of puffing, the click of wheels passing over rails, the sound of a slow-moving train travelling just across the river in enemy territory. Men heard definite sounds of wheels going over jointed tracks.’30

No train was heard on the railway between Solarolo and Lugo, opposite the sector held by 56 (London) Division, most of whose troops ‘must have grown up with London expresses roaring in their ears.’31 Aerial reconnaissance and photograph interpretation threw no light on the mystery. No engine or wagons were seen, and the line to both the north-east and north-west of Castel Bolognese was in such a state that it could not be used. The road system in the enemy’s rear was adequate for the bringing up of supplies; there was no apparent reason why he should go to the trouble and risk of repairing and keeping the railway in working order.

The Division found no satisfactory explanation for the ‘ghost train’. After hostilities had ceased in Italy, General Dr Fritz Polack, who had commanded 29 Panzer Grenadier Division at the time, said there had been no train running in the vicinity of Castel Bolognese. ‘No such sounds were heard by our forces. The only suggestion I can make is that it was the noise of long supply columns.’32

(iv)

From 10 January the 25-pounder ammunition was restricted to five rounds a gun each day. One battery in each field regiment took its turn in occupying an alternative harassing fire position from

which it did all the shooting; the other batteries (which were to fire only if an attack developed) remained silent so that the enemy could not register the main gun position.

To keep up the volume of fire in spite of the limitation on ammunition for the artillery and tanks, the infantry battalions made greater use of their own weapons, including six-pounder anti-tank guns and Piats; Browning machine guns were sited along the front; the M10s of 7 Anti-Tank Regiment gave defensive fire on call at night; the 4.2-inch mortars of 34 Battery covered the front for defensive and harassing fire. Because of the shortage of ammunition the Vickers guns of 27 (MG) Battalion seldom fired more than 15,000 rounds a day, often fewer; they were permitted to shoot only on call by the infantry and on special defensive-fire tasks.

Among the targets engaged by the artillery, tanks, M10s, mortars and machine guns were the German defences on the stopbanks of the Senio, working parties and patrols, vehicles, guns, mortars and occupied houses.

Normally quiet days, especially if Allied fighter-bombers were flying, followed nights of harassing fire, patrolling and much digging. Some of the enemy’s harassing fire was provided by self-propelled guns, which could be heard moving about beyond the river. Air photographs indicated that they were hidden by day in houses in the rear and brought forward by night to shoot. Althoug sought out by the artillery, M10s and fighter-bombers, they were not prevented from doing some damage.

The enemy seized the opportunity during a fog which blanketed the front in mid-January to strengthen his defences; his working parties could be heard hammering, digging, sawing wood and making other noises usually heard only at night. Whenever located, these activities were harassed and silenced, but they often started again after the shooting stopped. Some of the sounds were interpreted as coming from bridge-building. Air observation, however, disclosed on 22 January that there were fewer bridges after a spate in the river; a few days later none could be seen in front of the 56th and New Zealand divisions, but before the end of the month the enemy had replaced some and was preparing to replace others.

Observation of the enemy’s activities had aroused the suspicion that he might be thinning out preparatory to withdrawal. His mortars, Nebelwerfers and rockets – all weapons which could be moved easily – were still in use at night, but he had discontinued his artillery harassing programme. Although he obviously still had men on the stopbanks, no recent contact had been made with his patrols. More tracked-vehicle movement than usual was heard on the night of 24–25 January. The explanation, that a changeover had

been taking place, came the following night, when two men were captured from the newly arrived 4 Parachute Division which had relieved 29 Panzer Grenadier Division north of Route 9.

To test the strength of the German defensive fire and detect any sign of his thinning out, 5 Brigade put on fire demonstrations (or ‘Chinese’33 attacks, as they were called) after nightfall on 26 and 29 January, but stirred up very little response. After the later performance the enemy was seen reoccupying his positions on the stopbank.

General Freyberg gave instructions on 31 January for the Division to prepare to resume offensive operations; it was to implement immediately a policy which included reconnaissance and patrolling, the occupation of the near stopbank of the Senio as soon as possible, and the clearance of minefield gaps to permit the passage of tanks and the assembly of infantry for an attack across the river. In addition, the infantry brigade commanders were to examine two river-crossing operations, one from the Division’s present location and the other together with, and on the left of, a crossing by 56 Division between Cotignola and Felisio. The decision as to which course was to be adopted was to be reached at a conference on 2 February.

On the night of 31 January–1 February it was 6 Brigade’s intention that 25 Battalion should establish a fighting patrol of platoon strength on the stopbank about half a mile north-east of Felisio, and that 26 Battalion should secure a lodgement on the bank west of La Palazza and occupy a nearby house; at the same time 5 Brigade was to send out patrols to reconnoitre routes to the bank, lift mines and capture prisoners.

(v)

Having been instructed to take and occupy a 200-yard stretch of the stopbank south-west of Casa Gallegati, 12 Platoon (Second- Lieutenant Wilson34) of B Company, 25 Battalion, set out about 6.30 p.m. on the 31st. Probably warned by the noise of the men approaching over the encrusted snow, the enemy opened fire with spandaus from both flanks, but surprisingly stopped after a few minutes. Although Wilson’s men tripped the wires which fired two flares, they crossed open ground unchallenged and began to dig in on the stopbank. Strong opposition was expected from the left flank, where the Germans were known to be covering the road

6 Infantry Brigade, 31 January 1945

from Cassanigo, but apparently they thought they were being attacked by a larger force than one platoon; they abandoned their positions and weapons, dived into the river or made off to the left.

Four surrendered without a fight, and at least three were killed while trying to escape.

The enemy did not organise any opposition on the left flank for several hours, but brought increasingly heavy fire to bear from the front and the right. ‘Throughout the 15–16 hours we occupied these positions,’ Wilson later wrote, ‘enemy arty and mortar fire was extremely heavy with occasional relief. Our position on the stop-bank was difficult to hit. It was apparent that the enemy was consistently dropping his range on the advice of forward troops. ... Eventually, he reduced his range to such an extent that one heavy mortar “hate” dropped among his own troops with some effect if the groans and outcries were an indication of casualties.’35

The 3-inch mortars, responding well to 12 Platoon’s requests, made it hazardous for the enemy to venture on to the flat ground between the river and the far stopbank, which the platoon already covered with small-arms fire. The Germans who managed to cross the river in front of the platoon became the victims of their own mortar fire. ‘They lay or stumbled about as though wounded or “bomb happy” between the river and our positions and were the target of our fire and grenades. ... The enemy, however, soon appreciated the position and commenced to cross the river to our right and left. Darkness made visibility poor, but it was at times possible to disperse troops attempting to cross on our left. To the right, however, the bend in the stopbank obscured fire and enemy could cross unhindered except by mortar fire.

‘The difficulties of our position were very obvious at this stage. It was apparent that the enemy could cross in large numbers and attack from either flank. Positions to our right on the stopbank would enfilade us from the right rear. I did not foresee that he would later occupy Gallegati in strength and so cover our rear.’36 The enemy’s persistent supporting fire and sniping from the right made the bringing up of ammunition and the evacuation of casualties most difficult. Communications were improved when the company commander (Major J. Finlay) brought up a telephone and two lines, but very soon the lines were cut in many places by shellfire. After the platoon’s No. 38 set received a direct hit by a stick grenade, the only wireless communication came from an enemy set which ordered the platoon in English to surrender.

The enemy worked his way to within 50 yards, but Wilson felt that as long as his men had plenty of ammunition they could hold out and inflict more casualties than they themselves might suffer. Before dawn ‘a strong force attacked from the front and

both flanks with stick and rifle grenades which were employed with great accuracy. The only weapon of much use to us was [No.] 36 Grenades of which we threw between 150 and 180 in our period on the bank. With daylight, the enemy moved most effectively. From Gallegati and the stopbank to our right and from across the river he kept up persistent sniping and spasmodic bursts of Spandau while a large party operated with grenades on both flanks from in front.’ The section on the right ran out of ammunition and therefore could no longer hold off the enemy, who ‘with much daring ... worked right up to our central positions, suffering considerable casualties in doing so. He seemed to possess an unending supply of stick grenades and it was common during the last two hours to see up to two dozen in the air above us at the same time.’37

By mid-morning the platoon was practically out of ammunition and had no communication with B Company. Wilson reluctantly decided to withdraw and sent two men back at intervals to ask for smoke to cover the thinning out. Before this could be arranged, however, the enemy, sensing the platoon’s predicament, charged and overran the position. ‘It was extremely unpleasant to be taken so ignominiously. ... It is some consolation to record the enemy’s known casualties. ... I can record definitely that 11 of the enemy were killed, 15 wounded and 4 were taken PW. Others of my platoon claim to have seen further dead. ... It is possible that 40–50 casualties were inflicted. ... After the action had concluded, I was able to see within a 500 yard radius of my positions at least 500–800 enemy troops. ... The frontal attacking party I put at 80–100. ... I calculated that the enemy had been alarmed by the move and had expected it to be a prelude to a larger attack, and had consequently reinforced heavily.’38

The 25th Battalion’s casualties on 31 January and 1 February were four killed, 10 wounded and 22 missing. Among the missing were Wilson, twice wounded, and two others wounded. The prisoners were taken some 15 miles behind the German lines and interrogated, apparently without divulging any information of value to the enemy; eventually they all succeeded in rejoining the Allied forces.

Wilson’s platoon had been given an absolutely impossible task. A raid to take prisoners, inflict casualties and obtain information about the enemy dispositions might have succeeded if the platoon had withdrawn before the enemy could counter-attack in strength. But the platoon was required to hold part of the near stopbank,

about 400 yards in advance of the battalion’s foremost posts, while the far stopbank and the river (proof against tank attack until bridged) afforded the enemy defensive positions where he could reinforce for attacks on the platoon’s front and both flanks.

(vi)

On the left of 25 Battalion the 26th had a similar task that night but adopted different tactics: only one section was sent to the stop-bank, and it withdrew when the German reaction showed there was no hope of success.

The plan was for 16 Platoon (Second-Lieutenant Brent39) of D Company to secure a position with one section on the stopbank west of La Palazza, one section at a demolished nearby house, and one section and platoon headquarters at La Palazza. To create a diversion A Company’s outpost at Casa Galanuna and some tanks fired on the stopbank north of D Company’s objective, which was taken without much opposition. Very soon, however, Corporal Cocks’s40 section on the stopbank came under fire from the farther bank and both flanks. One Bren gun was hit and put out of action and another damaged; two tommy guns jammed after a few rounds. The digging was exceptionally hard in the frozen ground, and the men had done little more than scratch the surface when the enemy attacked from the right. Concentrated fire from the section’s still serviceable weapons killed two Germans and drove back the others. The 3-inch mortars and the field guns fired concentrations when the enemy was seen to be preparing for another counter-attack. Nevertheless eight or ten Germans succeeded in crossing the river. Enemy mortars ranged on the section’s position and, as Cocks’s men were running out of ammunition (all the grenades had been used), Brent gave the order to withdraw. The section, which had had one man killed and one wounded, brought back two wounded Germans, who said they had been only three weeks in Italy.

Fifth Brigade patrolled as intended in the evening of 31 January. Three-man patrols from the Maori Battalion (one each from B, C and D Companies) with mine detectors reconnoitred routes towards the stopbank in the vicinity of the river bend north-east of Palazzo Laghi and south-west of Casa Cuclotta without finding mines. Two of these patrols were prevented by machine-gun fire from reaching the stopbank; the third did not see the enemy.

The more northerly of 23 Battalion’s two fighting patrols (nine men from A Company) went from a house near Paganella to the

other side of the stopbank, but because of the noise made walking on the snow, recrossed it before approaching the railway. The patrol then heard sounds of digging and stake-driving, and threw a phosphorus grenade at two Germans who had a spandau, wounding one of them, but this attracted the attention of others in the vicinity who fired spandaus and attacked with rifle grenades. the patrol therefore withdrew.

The other 23 Battalion fighting patrol (12 men from D Company) carried an assault boat to the stopbank on the southern side of the railway, but could not lower it into the water because it was too heavy and the banks too steep, ice-bound and slippery. Neither fighting patrol, therefore, succeeded in taking prisoners.

Obviously an attack by a much larger force than a platoon would be necessary to gain and hold a lodgement on the stopbank. A revised policy was announced at the conference on 2 February: the Division was to continue patrolling and lifting mines on its front, but was to occupy no permanent positions in front of the existing forward localities; it was to maintain standing patrols where possible on the stopbank during the hours of darkness. A river-crossing operation on a corps basis was being considered: this was to be done by one brigade group of 56 Division on the right and two brigades of the New Zealand Division on a front of about 3500 yards on the left, and was to take place between Cotignola and Felisio, with an axis of advance to the north-west. It was expected that there would be 10 days’ notice before any such’ attack.

III: Eighth Army Regroups

(i)

The possibility of a German counter-attack on Eighth Army’s front could be almost ignored by the beginning of February; the enemy had lost his best opportunity when Eighth Army changed from the offensive to the defensive in January. Taking into account his losses in eastern Europe and the failure of his Ardennes offensive in the west, the enemy had nothing to gain by a doubtful venture in Italy; he had little reason to deploy large forces on an unnecessarily extended front there when he needed them elsewhere. It seemed, therefore, to be the logical course for the German High Command to choose the most suitable moment to disengage and withdraw across the River Po to a shorter line in north-east Italy.

The line where the German armies stood in the winter of 1944–45 was largely gratuitous; it had no particular strategic

German defences south of the River Po

significance; it was where the Allied offensive had come to a halt because of the troops’ exhaustion, the bad weather, the lack of ammunition, and the need for regrouping. Between the Adriatic and the Apennines it crossed the Romagna on the line of the Senio River; it continued along the last northern ridge of the mountains south of Bologna and to the coastal plain where the Germans still held, in front of Massa, a remnant of the Gothic Line.

On this coast-to-coast line the enemy had fortified his positions as best he could. There had been little real activity since December except in the Romagna, where Eighth Army faced beyond the Senio more river lines, named by the enemy Laura (on the Santerno), Paula (on the Sillaro) and Genghis Khan (on the Idice and anchored in the flooded country west of Lake Comacchio).41

These lines ‘were designated to cover Bologna from the south-east; at their northern end a line based on the Reno River gave depth to the defence of the River Po, especially in the region near the coast. This was the essential element of any plan of defence: the eastern flank of the German front must hold firm to allow the west to swing back toward the northwestern passes into Germany and the line of the Adige.’42

For some months the enemy had been hard at work on what was known as the Venetian Line, based on the Adige River and the hills between the Adriatic at Chioggia and Lake Garda. Beyond the River Po and the already formidable defences of the Venetian Line was the Prealpine Defence Position (Voralpenstellung), protected by the ‘almost impregnable barrier of the Alps.’43 To prepare these defences the Inspector of Land Fortifications South-West (General Buelowius, who had won Rommel’s praise while serving with the Axis forces in Africa) had under his control 5340 German engineer specialist and construction troops, but most of the work was done by thousands of Italians and other foreign labourers conscripted into the Todt Organisation.

Since the autumn the Germans had a plan of withdrawal (which they had given the codename Herbstnebel – autumn fog), but Hitler had persistently refused permission to put it into effect. Had General von Vietinghoff been able to withdraw his Army Group C behind the Po in good time, his chances of manning and holding the Venetian Line and the Prealpine Defence Position would have been immensely greater. But he was even forbidden to make small withdrawals to stronger positions south of the Po.

The commander of Tenth Army (General Traugott Herr) had prepared a plan for a ‘false-front’ manoeuvre: he wanted to fall back, under the cover of a heavy artillery barrage, from the Senio to the much stronger line of the Santerno the day before he estimated Eighth Army would renew its offensive. Such a plan would have nullified Eighth Army’s elaborate scheme of air and artillery support for an attack on the Senio line; the ground yielded by Tenth Army would have had negligible strategic value, and Eighth Army would have been obliged to attack the main German defences farther west without the same preparation.

Herr pleaded for the adoption of this plan with Vietinghoff, who told him, ‘I quite agree with your appreciation of the situation. I am absolutely of your opinion, but I have to tell you that it just won’t do. It has been forbidden.’44 This provoked the commander

of 76 Panzer Corps (General Gerhard Graf von Schwerin) to ask Herr how long was the Fuehrer to be allowed to ‘interfere in tactical situations of which he knew nothing.’45

The commander of 29 Panzer Grenadier Division (General Polack) shared his superiors’ views on the use of the Senio as the winter line. After the defeat of the German armies he told a New Zealand interviewer that it might have been better to have withdrawn to the Santerno, ‘but strict orders came from the High Command “Stay! Stay! Halt!” “Defend every metre.” Once it was seen that we could hold at the River Senio then orders came from above to do so. ... We had instructions to build up lines behind the front “just in case”. That is all right if sufficient troops are available. If troops and supplies are short the situation then becomes dangerous; if one line is lost it is very difficult to get workshops etc back in time. ... It was impossible to win the war therefore we should have withdrawn in greater bounds.’46

(ii)

The Allied commanders, on the other hand, appreciated that if the enemy chose the right time to disengage on the Senio front, he might catch Eighth Army at a disadvantage. It was important that Eighth Army should attack before the enemy succeeded in disengaging, but the preparations for meeting such an eventuality were complicated by the reduction of Eighth Army’s fighting power by the removal of the Canadian Corps from the Italian theatre at the end of February. It would take time for the remaining corps and divisions to regroup to fill the gap left by the Canadians. Moreover, while the divisions which were to take part in the offensive were resting and training, sections of the front were held by comparatively weak Italian combat groups.47

Eighth Army, therefore, planned so that a proportion of its forces was always ready to turn to the offensive at fairly short notice, and regrouped in a way that did not interfere with the plan. General McCreery ordered the Polish Corps to take command of the left sector and relieve 5 Corps as far north as Route 9. If the enemy began to withdraw in February, 5 Corps was to attack in its sector north of Route 9 and the Canadian Corps was to attack on its right; they were to be assisted by a feint by the Polish Corps on the left.

It was anticipated that, as a prelude to a withdrawal, the enemy would reduce to about two divisions his forces between Route 9

and the Russi-Lugo railway, where the main thrust was to be made. The 5 Corps’ plan of attack provided in the first phase for the capture of a bridgehead across the Senio in the northern part of the sector, between Cotignola and Solarolo, by 56 Division and the New Zealand Division; in the second phase, the capture of a bridgehead over the Santerno by the New Zealand Division and if possible also by 56 Division; in the third phase, an advance northwards through the bridgehead over the Santerno by 5 and 78 British Divisions, which it was intended should augment 5 Corps.

The 3rd Carpathian Division transferred from the Polish Corps to 5 Corps on 5 February, and in the next few days relieved 10 Indian Division south of Route 9; the Friuli Combat Group replaced 5 Kresowa Division farther to the left. The 38th Irish Brigade of 78 Division arrived from 13 Corps to take over the role of 5 Corps’ reserve from 43 Gurkha Brigade, which passed to 56 Division’s command. The first stage of Eighth Army’s regrouping was completed on the 13th when Headquarters 2 Polish Corps took command of the sector occupied by the Carpathian Division and the Friuli Group (south-westward from a point on the Senio 300 yards above the Route 9 bridge site). Fifth Corps’ sector (from the point near Route 9 to the Russi-Lugo railway) was then held by 56 Division on the right and the New Zealand Division on the left, with the Irish Brigade in immediate reserve.

The next phase of the regrouping was the relief of the Canadians, which was delayed while 8 Indian Division was brought from Fifth Army. Fifth Corps took command on 16 February of the Canadians’ sector from the Russi-Lugo railway to the Adriatic coast at the south-eastern tip of Lake Comacchio. The Cremona Combat Group, next to the coast, passed directly under 5 Corps’ command, and on the 25th 8 Indian Division completed the replacement of 1 Canadian Infantry Division.

The 5th Canadian Armoured Division had been withdrawn in mid-January, and with the departure of the infantry division the Canadians completed 20 months’ service with Eighth Army in Sicily and Italy.48 They were denied a share in the final victory in Italy, after having fought in the costly battles of Ortona, the Liri valley, the Gothic Line and the Romagna, but left a theatre recognised as secondary in importance to North-West Europe, where 1 and 2 Canadian Corps were reunited in First Canadian Army for the march on Berlin.

The transfer of 1 Canadian Corps to France was not the only reduction of the Allied forces in Italy: two fighter groups of

Twelfth US Air Force were also ordered to France. These losses, however, were compensated by the steady weakening of the enemy. When winter brought the Italian campaign temporarily to a standstill, the Russian front claimed any division which could be spared from Italy. Three49 were despatched.

The enemy’s difficulties were multiplied early in March when the American 10 Mountain Division, which had recently joined Fifth Army, attacked Monte Belvedere, south-west of Bologna, and in three days captured this key position with a thousand German prisoners. By the end of the month the German reserve in Italy had been reduced to two divisions, and with few exceptions the divisions in the line were unrested; Hitler’s orders to ‘defend every metre’ had prohibited their withdrawal to positions where they could more hopefully oppose ‘the inevitable offensive of two well rested Allied Armies, superior in equipment and morale, and almost every other respect.’50

(iii)

In mid-February, however, the enemy was still in undisputed possession of the Senio stopbanks, from which no attempt had been made to dislodge him since 25 NZ Battalion’s minor abortive assault at the end of January. After 5 Corps’ move farther to the right into the Romagna plain, control of the near stopbank – a prerequisite of the crossing of the Senio – was preferred about the centre of the front rather than on the comparatively unimportant sector held by the New Zealand Division on the left. An attack, therefore, was begun in the evening of 23 February by 56 Division (raised from two to three brigades by the inclusion of 43 Gurkha Brigade), with substantial help from the air force.

The Gurkhas gained most of their objective and beat off several counter-attacks between the Lugo-Russi railway and Cotignola, and also made contact with 167 Brigade south of this small town. The 1st London Irish reached the top of the stopbank at several places but failed to clear the Germans from a weir north-east of San Severo, while on the left 1 London Scottish did not reach the objective. On 3 March 2/7 Queens of 169 Brigade, using flame-throwers and supported by 40 fighter-bombers, drove the enemy from the stopbank in the locality of the weir. Although the enemy still held the bank at Cotignola and other isolated points, 56 Division now dominated it at several places.

Meanwhile the Italian Cremona Combat Group,51 together with the partisans of 28 Garibaldi Brigade and the tanks of the North Irish Horse, supported by British artillery and fighter-bombers, attacked the German positions guarding the spit of land between the east shore of Lake Comacchio and the Adriatic coast, with the object of securing a hold on the narrow tongue a few hundred yards wide between the River Reno and the sea. The enemy, who was carrying out a relief at the time, was taken by surprise. Over 200 Germans and Turcomen were captured. The ground was to form the base for an advance on the rest of the Comacchio spit.

In the first week of March, when the attacks by 56 Division and the Cremona Group ended, Eighth Army completed its regrouping. Since the departure of 1 Canadian Corps, 5 Corps had been responsible for a front of over 30 miles, and within its sector were the three major routes forward: Route 16 on the right, the road through Lugo and Massa Lombarda in the centre of the Romagna plain, and Route 9 on the left. The final stage of Eighth Army’s plan was to concentrate 5 Corps opposite the northern and central roads, and to bring 2 Polish Corps on to Route 9.

The Kresowa Division assumed command of the front along the Senio as far downstream as a point just south of San Severo, and thus relieved the New Zealand Division and the troops of 56 Division south of the new boundary between 5 Corps and the Polish Corps. By 8 March the New Zealand Division was in Eighth Army reserve.

IV: The Division Gets Ready

(i)

General Freyberg announced a revised policy at the conference on 2 February. The Division was to patrol and lift mines on its front, but was not to occupy permanent positions forward of those already held; where possible it was to keep standing patrols on the Senio stopbank during the hours of darkness. A river-crossing between Cotignola and Felisio by one brigade group of 56 Division on the right and two brigades of the New Zealand Division on the left was being considered. It was expected that 10 days’ notice would be given before any such attack.

Meanwhile the brigades were to practise river-crossing with assault boats and kapok bridging under conditions which resembled as closely as possibly the part of the Senio where the attack was

Dispositions, 15 February 1945

to be made. The time taken in these practice assault crossings would assist in drawing up the supporting artillery programme for the actual operation.

Except for one day (the 9th) of steady rain, February was fine; occasional thick mists, especially along the river, limited visibility to no more than a few yards, but usually dispersed before midday. The continuation of the thaw early in the month made the ground soft and muddy. The roads were almost unusable until they began to dry out; later they became dusty.

In the Division’s sector, which extended about 8000 yards along the Senio downstream from just south of Route 9, each infantry brigade continued to have two battalions in the line and one in reserve at Faenza; each battalion was given two weeks in the line and one in reserve.

The infantry continued to send patrols to the Senio to determine the state of the river and its approaches and to obtain information about the enemy defences and intentions. The enemy also endeavoured to gain information about dispositions, and there were several clashes with his patrols, in which his units were identified by the taking of prisoners.

A patrol from 23 Battalion – while searching for eggs at Casa Paganella – captured in a haystack two enemy who had been sent out to ascertain whether Paganella was held and if possible take prisoners. One was an Austrian and the other a Sudeten German officer-cadet who had left Berlin three days earlier to get battle experience; the latter was confident that the Russians would be hurled back and that Germany would win the war.

A patrol from 26 Battalion reconnoitred a gap the enemy had blown in the stopbank west of Casa Claretta. The New Zealanders approached to within 100 yards of the demolition and heard digging and voices, but could not observe properly because of fog. Several theories were advanced as to the purpose of the gap: it was to flood the low-lying land when the river rose with the spring thaw; it was to be an aperture through which a self-propelled gun was to fire; it was intended to be a bridge site.52

The rain on 9 February occupied the enemy’s attention for 24 hours. Observers reported that the river had risen until it was from eight to ten feet from the top of the stopbank – with no apparent effect at the breach on 26 Battalion’s front. The noise of hammering and chopping indicated that the enemy had found it necessary to strengthen some of his bridges; and in at least one locality German slit-trench dwellers spent most of the night baling water.

After concentrated machine-gun fire and a bazooka bombardment, an enemy party believed to be at least a dozen strong, unobserved in the fog before dawn, approached an outpost which 23 Battalion had occupied on the stopbank about 200 yards north of the railway. The New Zealanders claimed that they inflicted several casualties on the enemy with grenades, but had to withdraw when more Germans arrived. The enemy prevented a patrol from reoccupying the outpost in the evening and engaged later patrols with tank and mortar fire. One patrol was ambushed and had to fight its way out with two men wounded.

The enemy swept 21 Battalion’s front with machine-gun, mortar and shell fire for three minutes and then engaged platoon and

outpost buildings with self-propelled guns, which scored direct hits on four houses. Two buildings collapsed, but the men, who sheltered in covered dugouts, were extricated later. During the harassing fire a German six-man patrol approached an outpost at Palazzo Laghi under the cover of smoke, but withdrew when engaged by infantry weapons and mortars.

Three deserters who came into the lines of 56 Division (on the New Zealanders’ right) on the night of 19–20 February were from 26 Panzer Division, which apparently had replaced 278 Division the previous night. The 26 Panzer had withdrawn from Faenza after the New Zealand attack on 15 December and had been resting and rehabilitating north-west of Lake Comacchio. Five deserters, all from the same company of 9 Panzer Grenadier Regiment of this division, gave themselves up to 26 Battalion during the next two nights; they said others of their company would do the same were it not for the danger of the minefields. Of the five, one was a young Soviet national of German stock who had fought with three different armies – the Russian, the German, and the Italian partisans; he had been caught up in the Wehrmacht again after being wounded with the partisans. Of the other deserters, one was a Reich German and three were Poles.

Deserters also came from 4 Parachute Division, which was astride Route 9 between 90 Panzer Grenadier Division on its right and 26 Panzer Division on its left. Of the 73 enemy who passed through 5 Corps’ prisoner-of-war cage between 26 January and 25 February, 51 were deserters; more than half of these were Poles, Alsatians and Yugoslavs who were unwilling to go on fighting for the Germans. The fear of reprisal against the deserter’s family ceased to be a deterrent when Poland and Silesia were ‘liberated’ by the Russians.

The German’s traditional upbringing had taught him that desertion was dishonourable, but many who realised that the war had been lost but was being continued for the sake of the Nazi leaders were anxious to save their own lives. Only a fanatical minority had any hope of an outright German military victory, but propaganda had sustained in others the vain hope that if they stuck it out long enough a satisfactory compromise could be achieved. After the defeat of the German counter-offensive in the west and the failure to stop the Russian drive in the east, German prisoners admitted that morale had slumped badly and many were waiting for a chance to desert. Nevertheless, throughout the German divisions a hard core of tough and experienced men was still prepared to fight to the end.

(ii)

February in the Division’s sector followed much the same pattern as January. The artillery did very little shooting because of the stringent restriction on the expenditure of ammunition; there was little or no activity among the guns during the daylight hours and usually only light harassing fire at night. They engaged self-propelled guns, mortars, machine guns, buildings and dugouts, vehicles, patrols and working parties. The lack of ammunition prevented the M10s, 17-pounders and 4.2-inch mortars from attempting all the tasks requested by the infantry. The tanks53 were called upon to shell enemy positions and other targets. When some fired along the stopbank north of Palazzo Laghi, the infantry saw the shells penetrate the bank in three places and explode on houses 200 yards beyond it.

The ‘Chinese attacks’ were repeated, usually for a quarter of an hour at a time, to test the enemy’s reaction. In the evening of 3 February the heavy mortars smoked an area across the river north of Palazzo Laghi and 5 Field Regiment, 19 Armoured Regiment, the mortars and the Maori Battalion’s infantry weapons brought down fire on selected targets and suspected positions on the stop-bank and across the river. The enemy retaliated with heavy shell, mortar and machine-gun fire. His reaction to a similar ‘Chinese attack’ by 26 Battalion four evenings later was described as violent: he fired flares and harassed the front with machine guns and mortars, and employed heavy mortars and medium guns in well-placed defensive shoots on crossroads and open approaches to the stopbank. A demonstration by the artillery, tanks, M10s, mortars and Maori Battalion’s weapons before dawn on the 19th, however, produced only harassing fire from mortars and small arms.

Sixth Brigade staged a ‘Chinese attack’ in the evening of the 23rd to assist 56 Division’s attack north of the New Zealand sector. This provoked the enemy to put up flares and bring down artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire for about an hour. Fifth Brigade mounted probably the most spectacular demonstration of all on the evening of 2 March with fire from the artillery, tanks, mortars and 23 and 28 Battalions’ weapons. Again the enemy replied with shell, mortar and machine-gun fire, much of it directed on the roads.

Usually the German harassing fire was light, but occasionally concentrations caused casualties. The German self-propelled guns on the roads beyond the river, especially in the vicinity of Felisio, continued to be troublesome. A very thorough programme was

organised so as to concentrate fire, including air-burst by anti-aircraft guns, on each self-propelled gun as soon as it went into action, usually with the result that it moved away quickly after firing only a few shots.

Shells containing propaganda leaflets were fired by both sides. Some which landed among 21 Battalion described methods of producing symptoms of diseases and claimed that it was ‘better a few days ill than all your life dead’. Propaganda was also broadcast by loudspeakers, including invitations to the enemy to desert. Among those who did were Poles who subsequently found themselves back in the line with the Polish Corps. A news commentary in German and two musical recordings (‘J’Attendrai’ and ‘Vienna Blues’) were broadcast from the church at Pieve del Ponte. The enemy appeared to listen attentively and was noticeably less active until the programme ended.

(iii)

On the Lamone north of Route 9 the battalions of 5 Brigade practised river-crossing with assault boats and kapok bridging; Wasps and Crocodiles demonstrated flame-throwing against the defences on the far bank; the engineers experimented in bridging the river between high stopbanks in which gaps were cut by explosives and bulldozers so that they could be negotiated by tanks and other vehicles.

On 3 March, a brilliantly sunny day, the Division demonstrated its river-crossing and bridge-building techniques to a very large number of spectators, including visitors from Corps and other divisions, who were addressed by the GOC. There were, he said, two ways of forcing a canalised river where the enemy held both banks: to attempt to take both banks in ‘one bite’ under a heavy bombardment, or alternatively to ‘take two bites’ by first securing the near stopbank and then the other by going through far enough to allow the bridging of the river for the supporting arms. The second method was preferred ‘because you cannot get surprise in the fullest sense by doing one attack. If you make only one attack then heavy equipment has to be assembled at least 400 yards back from the near stopbank and it must take about ten minutes to get all this forward, and by that time the enemy will have had ample opportunity to hold the far bank in strength.’54

The General announced that the Division was going out of the line for a month’s training for the next battle. If the enemy still was on the near stopbank when the Division returned to the line, he

was to be pushed off 10 days before the attack.55 The Division was to attack on a two-brigade front, and each brigade was to have a two-battalion front. The frontage of the battalion depended on the strength of the enemy positions; the policy was to attack with two and a half times the number of men the enemy had.