The Pacific

Chapter 1: Japan—Rise and Conquest

JAPAN'S role in the Pacific was not considered of any great importance, and certainly created no sense of insecurity, until after her defeat of Russia in 1905, which gave her control of Port Arthur and of Korea on the mainland of Asia. From comparative obscurity, Japan had risen to a second-class world power by her victory in the Sino-Japanese war of 1894–95, after which increasing world opinion was directed on her industrial activities and on a rising population which began to worry other countries. Until 1905, however, New Zealand's attitude was favourable, and any talk of a ‘Yellow peril’ referred only to the Chinese. A noticeable change came after the Russian defeat. Japan rose to the position of a first-class power, and her menacing birth rate drew warnings from such people as Sir Robert Stout, who publicly voiced the fear of her competition in industry and a possible demand for lands for emigration. Australia, with her ‘White Australia’ policy, had long been stridently conscious of the threat from Japan—a threat which was not completely allayed by the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902, into which Britain was forced by her fear of Russian expansion and possible supremacy in the Far East, for at that time Russia was attempting to obtain by diplomacy what she has obtained today by political influence and force of arms—a controlling interest in China.

By 1909 this Alliance was showing signs of deterioration as the power of the German Navy increased the alarm of Great Britain. New Zealand offered a battle cruiser, HMS New Zealand, to assist in strengthening the British Navy as well as removing a little of the load from the British taxpayer, and during Parliamentary debates which followed a proposal to borrow £2 million to pay for this gift, speakers displayed some concern for what they described as dangers north of the Equator. By that time Japanese infiltration into the Pacific was unmistakable. Apart from her increasing trade with Pacific countries, Japanese were being employed in mounting numbers in the rich chrome and nickel mines of New Caledonia, a French possession sitting astride most vulnerable sea lanes, and apprehension was displayed in 1911 that ultimately Japan might

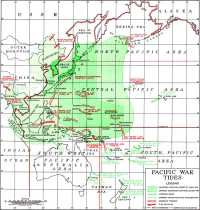

Pacific War Tides

use that island as a base which would imperil both Australia and New Zealand. It all seemed like a pattern of things to come.

Her ultimate goal—supremacy in the Pacific—was the subject of newspaper articles pointing out such dangers. The renewal of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance did nothing to stem a deepening mistrust of Japan, for in 1913 the Rt. Hon. W. F. Massey, Prime Minister of New Zealand, considered that such an alliance was not sufficient protection for this Dominion; therefore she must do something for herself.

British colonies and dominions in the Pacific regarded Singapore as their protector; the might of the British Navy as their shield. Even until the fall of that great strategical base, the whole of British Pacific strategy was centred on and about it. The Imperial Conference held in London in 1909 urged the necessity for creating and maintaining a strong fleet based on Singapore for Pacific defence, but its establishment was delayed because of the rapidly increasing strength of the German navy and its menace in European waters. Massey at that time most forcefully advocated the creation of a strong Pacific naval force, and proposed that Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa should join together in forming a fighting navy in the Pacific which, he said, prophetically, ‘would yet become the battlefield of the nations’. Because of the German menace, however, and before Massey's proposal bore fruit, the war of 1914–18 had broken on the world. Britain's action in maintaining a stronger fleet in Home and Mediterranean waters was justified, but the progress of the First World War provided Japan with her long-desired opportunity to establish herself in such strength and secrecy in Pacific islands north of the Equator that her bases there became her springboard in 1941.

Britain showed no great enthusiasm for Japanese intervention in the 1914–18 conflict and wished for none unless her Far Eastern and Pacific possessions were jeopardised, but all diplomatic persuasion failed to keep Japan neutral. She declared war on Germany on 23 August 1914, and on 7 October seized all the German-held islands north of the Equator, occupying the Pelew, Marianne, Caroline, and Marshall Groups, with Truk as the hub. Australia was prepared to send a force into the Carolines and Marianas before the Japanese move, but her troops were required in other theatres of war. Japan's precipitate action alarmed Australia, but this alarm was to some extent pacified by the British Government's statement that it would be more convenient to allow Japan to remain in the territory she had occupied until the end of the war, when the future of the islands would be decided. Japan became an ally, and ships of her navy protected convoys from Australia and

New Zealand in the Indian Ocean and also did convoy work in the Mediterranean.1

The Japanese move to take advantage of British weakness in the Pacific in 1914 was so swift and determined that it suggested a preconceived plan of action. Moreover, the demanded a stern price for any military or naval assistance which was forthcoming. By 1917 Japan was firmly entrenched in the islands she had seized. Her possession of the Marianas and the Carolines was discussed at the Imperial War Conference in London in 1917, when Japan's retention of all former German islands north of the Equator was assumed, but she was not to move south of that line. At the Peace Conference at Versailles in 1919, Australia and New Zealand, with extreme reluctance, yielded to those concessions already pledged to Japan. From the time of her occupation of the former German territory, Japan adopted a secretive attitude concerning her activities there. Every obstacle was placed in the way of traders and shipping until, finally, whole groups of islands became lost to the world's intelligence except on charts and maps. Those island bases were not captured and opened to the world again until 1944-45.

Japan used the 1914–18 War to her great advantage, both in the islands and in China, but it was a price the British Commonwealth had to pay for its inability to maintain a major fleet in the Pacific. Even before the war ended, Japanese newspapers, influenced by a pro-German section of her politicians, insisted that it was Japan's ‘duty and right’ to maintain peace in the East. Some of those same politicians demanded that the Allies withdraw the whole of their military and naval strength from China, Vladivostok, Mongolia, Manchuria, Siberia, and the South Seas and India, leaving Japan in control of the regions thus evacuated. Such statements were not rebuked by Ministers. In September 1918 the Mayor of Tokyo foresaw a possible war with Great Britain and the United States and prophetically stated: ‘Japan must bravely face the inevitable, even though she will ultimately be defeated.’

But he was not the only prophet, as Massey had been. When Admiral Lord Jellicoe toured the Pacific in 1919, he realised the relentless ambition of the Japanese and the beginning of fulfilment of their Pacific ambitions once they obtained mandate control of the Marshall and Caroline Islands. He realised then that the interests of Japan and Britain must inevitably clash. ‘In the event of war with Japan’ was Jellicoe's theme in suggesting Pacific defence and strategy for the future advice of the Lords of the Admiralty.

At the conclusion of his tour in HMS New Zealand, during which he visited Fiji and the Solomons, Lord Jellicoe reported: ‘It is impossible to consider the question of naval strategy in the Pacific without taking account of Suva Harbour. This harbour holds a position of great strategic importance with reference to New Zealand and Australia. It should accordingly be strongly fortified and held. At first guns to meet a scale of attack of unarmoured vessels should be established and then heavy guns to meet a scale of attack of armoured vessels.’ A high-power radio station was also recommended by Jellicoe, who regarded Fiji as a most vital centre in Pacific communications. Except for the radio station, a commercial undertaking, nothing could be done in Fiji because of commitments at the Washington Conference, which also nullified Jellicoe's proposals to develop the Tulagi-Gavutu Harbour in the Solomons into a major naval base. At the outbreak of war in 1939, Suva still remained the dolce far niente island outpost it was during Jellicoe's visit twenty years previously. Even by June 1941 the coast defences of Fiji consisted only of two 6-inch naval guns and two 4.7-inch guns covering the more vulnerable reef passages, and these had been emplaced after the outbreak of war. Jellicoe's report also made manifestly clear the weakness of both Singapore and Hong Kong, if they were attacked with determination by land and sea forces. Ships of the Royal Sovereign and Queen Elizabeth class, he pointed out, could not dock at Singapore if they were fitted with bulge protection against submarines, and both bases were extremely vulnerable to attack by submarines and coastal motor boats. First-class fighting naval units were consequently unemployable for Pacific defence unless Singapore were greatly extended and improved.

Through the years following 1914 Japan built up her navy and extended her naval bases on the mainland, particularly at Kure, Yokosuka, and Sasebo. The Washington Conference of 1921, after which, as Churchill commented, ‘the British and American Governments proceeded to sink their battleships and break up their military establishments with great gusto’, really gave Japan command of the seas in the Pacific, a command she never lost until 1943. That conference enabled her to maintain in the north-west Pacific a fleet superior in strength to anything Great Britain or the United States could maintain. It also guaranteed that the United Kingdom and the United States would not develop bases in the status quo area, which included Hong Kong and the Philippines; the island base of Guam, on which a huge defence scheme was halted; Pago Pago, in American Samoa; Suva, in Fiji; and Tulagi in the Solomons. Even when the treaty lapsed, Congress rejected plans for

the refortification of Guam. A product of the Washington Conference was the Four Power Pact, signed by Japan, France, Great Britain, and the United States in 1922, and under its guarantee the signatory powers were to respect each other's property in the Pacific area. However, it did little except strengthen Japan's hand.

Changing political situations in Great Britain gravely affected the Singapore naval base which, by diplomatic manoeuvre at the Washington Conference, had been excluded from the status quo area and could therefore be fortified without restraint. Britain decided to embark on a scheme of expansion and extension, estimated to cost £21,000,000, but this was abandoned when the MacDonald Government came into power. Massey, during discussions at the Imperial Conference in London in 1923, strongly protested, pointing out that such action gravely exposed New Zealand and Australia to attack, but MacDonald, pinning his faith in the League of Nations, insisted that the building of the Singapore base would have a detrimental effect on the foreign policy of Great Britain, whose task before the world was to ‘allay international suspicions and anxieties’. The defeat of the MacDonald Government enabled the original plan to go ahead under Baldwin.2 In 1927, under the Coates administration, New Zealand offered to contribute £1,000,000 towards the cost of the base, payable over a period of years at the rate of £125,000 a year. This brought a strong protest from Mr. H. E. Holland, leader of the Labour Party in New Zealand, but Mr. W. Nash, also a Labour leader, in an address to the Institute of Pacific Relations in Honolulu, told his audience that New Zealand public opinion supported the contribution because the British Fleet was one of the great securities for the peace of the world. The urge behind the New Zealand Government's offer was purely one of defence.

In 1929, however, MacDonald was returned to power in England and work on the base was slowed down, although the following year the Imperial Conference agreed to proceed with the dock and air base, but to postpone all other work for five years.

Japan's withdrawal from the League of Nations in 1933, on the question of the League's refusal to recognise the State of Manchukuo, increased British distrust of her intentions. By this time she had violated the Nine Power Pact of 1921 and the Paris Pact

of 1928 by overrunning Chinese Manchuria. From then on she extended her territorial activities on the mainland of Asia in an undeclared war on China, during which she seized provinces in North China, bombed Shanghai, sank the United States ship Panay, and sacked Nanking. New Zealand, with the rest of the world, was deeply concerned by these continued hostilities and by the extension of Japanese trade as she sought to obtain raw materials, particularly wool and scrap metal, from abroad.3

Mr. W. J. Jordan, New Zealand High Commissioner in London and the Dominion's representative to the League of Nations in 1937, protested on behalf of New Zealand against the bombing of Chinese towns, but his recommendation ‘that members of the League use their influence to deter Japan from continuing her present from of aggression’ was lost. That year he also addressed the Imperial Defence College on New Zealand's preparations for defence (they were not ambitious), and in a note to the Prime Minister, the Rt. Hon. M. J. Savage, said that after speaking of the proposals he would come back to the point that the best form of defence was the settlement of the country by contented and prosperous people. Savage attended the Imperial Conference of 1937, at which opinion still considered the British Fleet sufficiently strong to prevent any major Japanese operations against New Zealand or Australia. But events in Europe, and the growing truculence of Japan as she continued her undeclared war on China and moulded her policy on that of Germany, created uneasiness and misgiving in the South Pacific. Mr. J. A. Lyons, Prime Minister of Australia, suggested in London a regional pact in the Pacific. Savage supported him and asked for an assurance from the British Government that the British Fleet, even if it were engaged in European waters, would also be sufficient to contain the Japanese fleet in Eastern waters. Obviously Singapore was still regarded as an impregnable base, though even by September 1940 there were only 88 first-line aircraft in Malaya and nine battalions of troops, whereas the estimated requirements were 336 aircraft and eighteen battalions.

The first decisive move in an attempt to overcome weakness which daily grew more obvious, was initiated by Savage, who suggested that representatives of Great Britain, Australia, and New Zealand should meet to discuss the defence of the Pacific ‘in its widest aspects, sea, land, and air’. This conference opened in Wellington on 14 April 1939 and was attended by senior representatives of the three fighting services from each country. A month previously Czechoslovakia had been absorbed and Hitler was still thundering over the air that he had no more territorial ambitions in Europe. The conference considered the defence of certain Pacific islands, and selected a limited number of island bases from which to maintain observation over a chain of islands between Tonga and New Guinea, so that the approach of any raiding forces could be advised. It was agreed, also, that Fiji was the most important island in any defence scheme for Australia and New Zealand. Recommendations made to the Government were that a third cruiser should be manned and maintained and New Zealand merchant vessels ‘stiffened’; the Royal New Zealand Air Force to increase its output of trained pilots for the Royal Air Force; the regular and Territorial forces be increased, and detachments despatched to Fanning Island and Fiji as soon as war with Japan seemed inevitable. Questions of supply were also discussed, and it was recommended that liaison officers be appointed to the Defence Department in Australia and the War Office in London and that all reports be exchanged. Action was taken on some of those recommendations.

At the conclusion of the conference Major-General Mackesy, the British military delegate, was asked by the New Zealand Government to report on the Dominion's land forces. His report was depressing but inevitable in view of a policy which had shown little interest or enthusiasm in defence matters. His considered opinion was that the New Zealand Army had been allowed to become the Cinderella of the services and that New Zealand was incapable of repulsing any serious landing force. He recommended the immediate creation of a small regular land force of three infantry battalions and the expansion of the Territorial Force. Savage lost no time in appealing for men. On 22 May he asked for an increase in the peace establishment from 9500 to 16,000 men, another 250 for the coast defences, and for every able-bodied man from 20 to 55 years of age to register in the national defence reserve. Additional defence equipment, supplies of which were dangerously low, was ordered from overseas, but before that could be obtained or industry geared for its production, war had overwhelmed Europe.

Just as she fought for time in Europe, Great Britain fought for time in the Pacific, though Singapore was still regarded as the impregnable keystone of her defence. When the Commonwealth Prime Ministers met in London in November 1939, Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, in a memorandum referring to the possibility of a Japanese attack against the base said, ‘it is not considered possible that the Japanese, who are a prudent people and reserve their strength for the command of the Yellow Seas and China, in which they are fully occupied, would embark on such a mad enterprise.’ Nor did the British Chiefs of Staff reveal any great apprehension. In a review of the strategical situation they reported: ‘We feel that the immediate danger to Australia and New Zealand is remote.’ Churchill considered that Singapore could be taken only after a siege by an army of 50,000; the Chiefs of Staff felt that the Japanese would direct their attack against the mainland of Asia. The policy outlined at the London conference stated that, in the event of conflict with Japan, the three main objectives of the United Kingdom would be:

1. The prevention of any major operations against Australia, New Zealand, or India.

2. To keep open sea communications.

3. To prevent the fall of Singapore.

Mr. Peter Fraser, Deputy Prime Minister, attended the conference and expressed his apprehension concerning defences in the Pacific. At least two flying boats, he urged, should be made available to New Zealand to carry out reconnaissance in the islands should the necessity arise. At that time Britain's diplomacy aimed at a policy which would do nothing to antagonise Japan. In July the American-Japanese Commercial Treaty of 1911 was terminated. Britain considered denouncing the Anglo-Japanese Treaty, and New Zealand was prepared to break her trade agreement with Japan, but the British Government delayed action, fearing Japanese reprisals. After the outbreak of war with Germany on 3 September 1939, Britain endeavoured to prevent essential supplies of Malayan tin and rubber from reaching Germany via Russia, and Japan agreed. Even when Britain tightened the blockade against Germany in the Far East by intercepting and examining ships of all nations thought to be carrying cargo to Vladivostok, certain conditions were laid down so that Japan would not be offended. There was to be no interception of ships within sight of the Japanese coast or north of latitude 20° 21'; Japan was also requested to give an undertaking that certain specified war purpose commodities would not reach Germany via Japan or Japanese territory or by Japanese

transport. The British Government, conscious of its weakness should the British Fleet be called on to fight in the Pacific, did its utmost, diplomatically, to keep Japan out of the war. The situation in Europe grew bleaker through 1940 as the German armies swept into Norway, Denmark, Holland, Belgium, and France. In the grim days of May 1940 Churchill took over from Chamberlain, but all he could offer was his historical quartet, ‘blood, toil, sweat, and tears’. In France, three days after Churchill's leadership was assured in England, Reynaud took over from Daladier, but nothing could stem the German tide. Between 27 May and 4 June the British armies were saved from annihilation by the Dunkirk evacuation, and on 22 June France signed an armistice with Germany.

The fall of France shattered British Commonwealth defence in the Pacific, and Japan again quickly seized her opportunity, just as she had done in 1914. General Hata declared in Tokyo: ‘We must not miss this rare opportunity. ... Japan must act drastically against the powers who obstruct her policy’. She demanded that Britain cease supplies to China and withdraw her garrison from Hong Kong. Demonstrations against British nationals in Japan became more frequent. The British Ambassador in Tokyo, Sir Robert Craigie, endeavoured to prevent Japan from entering the war on the side of Germany and Italy, with whom she had become partners under the Pact of Berlin, a military alliance signed on 27 September 1940. He attempted to obtain some declaration from the United States on Anglo-American policy in the Far East and suggested certain lines of action, including joint assistance to Japan in bringing about peace with the Chinese Government. Japan was to undertake to remain neutral in the European war and to respect the territorial integrity of the Netherlands East Indies and British, French, and American possessions in the Pacific. The British Government decided to act on Craigie's suggestions and was supported by the New Zealand Government, which also wished for some clear indication of the Far Eastern policy of the United States. But none was forthcoming. The United States Government would not take any action which might commit her to war in the Far East, though she raised no objection to Great Britain's exploration of a possible settlement with Japan on terms acceptable to China, ‘consistent with principles for which the United States stands’. Public opinion in America was being carefully nursed and nourished by Roosevelt, though certain action had been taken to assist Great Britain. Fifty of her older destroyers had been exchanged for bases in British territory in the West Indies, Newfoundland,

and Bermuda on a 99 years' lease and granted ‘freely and without consideration’. British and American war supplies were reaching China via the Burma Road, which the British refused to close when first requested to do so by Japan. New Zealand and Australia supported this action, but the outcry in Japan was such that Britain, hard-pressed by events in Europe and the Middle East, closed it to war supplies for three months on 18 July, opening the road again on 17 October. New Zealand protested against this concession, fearing the danger of a policy of appeasement, and that it might antagonise America. During those critical months, when the Battle of Britain was raging and the German submarine attack on British shipping was being intensified, there was a change of Government in Japan. Prince Konoye took over an administration which was more aggressive and pro-Axis than ever, basing its actions on the assumption that the British Empire was ‘effete and ripe for dissolution’.

There was no improvement in Anglo-Japanese relations through the first six months of 1941. An indication of New Zealand's attitude was revealed in February when Mr. Kakafuji, the Japanese consul, called on Mr. Fraser, now Prime Minister in succession to Mr. Savage. He was left in no doubt regarding this Dominion's action in the event of trouble. New Zealand, Fraser forcefully told his visitor, would play her part fully with other members of the Commonwealth. In London the British Foreign Secretary, Mr. Anthony Eden, made clear to the Japanese Ambassador that Britain could not agree that Japan alone was entitled to mediate in Far Eastern disputes or was entitled to dominate all the peoples of the Far East. The existing tension, he said, had been created by the unexplained movements of Japanese forces in Formosa, Hainan, Indo-China, and the South China Sea.4

Although there was no public assurance from the United States of active armed support, the American Government did consider freezing Japanese credits. By June 1941 she had moved three battleships, four cruisers, nineteen destroyers, and one aircraft carrier from the Pacific Fleet to the Atlantic, and by so doing possibly lessened the disaster of Pearl Harbour. This action was regarded favourably by both Australia and New Zealand, who welcomed it as a deterrent on Japan by the implication that the United States would enter the war to help Great Britain, but both countries

wanted at least six American capital ships and two aircraft carriers to remain in the Pacific. The Lend-Lease Act,5 providing for much-needed assistance, was signed on 11 March 1941, and American naval vessels assisted British convoys in American waters. United States marines had also landed in Iceland. Though she did everything to avoid a conflict through 1941, Great Britain considered black-listing large Japanese firms and denouncing the Anglo-Japanese commercial treaty. New Zealand cautiously preferred the last-named action because ‘circumstances are now exceedingly delicate and any unnecessary irritation at this present juncture would be unwise.’

While diplomatic discussions were in progress Japan, whose troops were already in the country, demanded naval and air bases in Indo-China, to which the submissive Vichy Government agreed. On 26 July 1941 the British and United States Governments and the Netherlands East Indies Government issued orders freezing all Japanese credits. On the same day the British Government terminated the Anglo-Japanese commercial treaty. New Zealand took similar action on 27 July.

Japan was not deterred by such action, though her naval chiefs were gravely concerned about declining oil and petrol supplies after the imposition of an embargo by the United Kingdom and United States in July. By negotiation and intrigue she obtained a controlling interest in Thailand, thus directly menacing Malaya, gaining it in face of diplomatic moves by Great Britain and the United States and appeals from Thailand for assistance. On 13 April 1941 she signed a non-aggression pact with the USSR, using that as a weapon to exert pressure on the Netherlands East Indies Government for economic concessions—principally in rubber and oil—which the Dutch firmly opposed. New Zealand urged the necessity for guaranteeing the military security of the Dutch Indies, but Great Britain replied that she was in no position to do so without the necessary support of the United States Government, which was still non-committal.

Fearing Japanese reaction, the Dutch had declined to attend staff talks at Singapore when British, Australian, and New Zealand service chiefs met there in November 1940 and discussed Far Eastern defence problems. However, when Great Britain intimated her strategical interest in the Netherlands East Indies, Dutch officers did attend secret staff conversations but without political commitments on either side. New Zealand expressed disappointment that a full guarantee could not be given to the Dutch, but it

was obvious that without definite public assurances of American aid Great Britain could not commit herself too deeply in the Netherlands East Indies. In the event of attack Great Britain was too weak, particularly in land- and carrier-based aircraft, to defend her long lines of communication. The penetration of German armies into Russia at this time was also disturbing the war planning in London.

Late in 1941 the United States took the lead in negotiations with Japan in order to try to avert a clash, though her attitude and assistance to China governed any definite concessions to Japan. Craigie, in Tokyo, was of the opinion that Prince Konoye wished to meet President Roosevelt to discuss a possible settlement of the United States-Japanese conflict. The United States rightly maintained that any settlement involving China must provide fully for the sovereignty and territorial security of that country, otherwise permanent peace in the Pacific would be impossible. Konoye seems to have been perfectly sincere in his desire to avoid a conflict, and Craigie pointed out that the Japanese Prime Minister could only retain support for his policy if the meeting with Roosevelt took place quickly. But it never did—Konoye's Government fell on the issue of the Washington conversations, and General Tojo and his extremists took over.

Early in November Mr. Saburo Kurusu was despatched to Washington by his Government to assist the Japanese Ambassador, Admiral Nomura, in his conversations towards a settlement, but it soon became evident to Mr. Cordell Hull, United States Secretary of State, that all Japan wanted was time and the speedy removal of economic pressure. Mobilisation orders to the Japanese Southern Army were issued secretly in Tokyo on 6 November, and the areas to be seized were decided on 20 November, while the Washington conversations were taking place. Had this been revealed, the plans of the Japanese High Command would have been wrecked. What Japan hoped to gain from the Washington talks was a restoration of commercial relations such as existed before her credit was frozen, a supply of oil, and pressure from the United States on the Netherlands Indies Government to force it to supply Japan with petroleum and other products. Great Britain agreed with the United States that all Japan sought was ‘the speedy removal of economic pressure but not the speedy settlement of anything else’. Hull put up counter proposals, which the Chinese regarded as ‘disastrous’ and Great Britain as none too satisfactory. New Zealand was kept fully acquainted with these negotiations and supported the British Government. Hull's suggestion included the Japanese withdrawal of the bulk of her troops from China, and in

return referred to the possibility of the United States, Great Britain, and the Dutch Governments giving ‘some relief from economic pressure’. He considered this suggestion might lead to a wider settlement and gain valuable time. In view of Chinese opposition, which took the form of a direct appeal to Roosevelt by General Chiang Kai-shek, who considered that any relaxation of the embargoes would cause Chinese morale to collapse, Hull handed to the Japanese Ambassador a final plan, containing a proposal for a mutual declaration of the national policies of their two countries. This plan, ‘a broad but simple settlement covering the entire Pacific’, was in two parts, the first of which contained the proposed mutual declaration of policy, affirming the desire of both countries for lasting peace, the sovereignty of all Pacific nations, principles of commercial equality and opportunity, and an agreement to support and apply certain principles in their economic relations with each other. The second part set out in ten paragraphs steps to be taken by both countries to give effect to this plan, the more important of which were:

1. The Government of the United States and the Government of Japan will endeavour to conclude a multilateral non-aggression pact among the British Empire, China, Japan, the Netherlands, the Soviet Union, Thailand, and the United States.

3. The Government of Japan will withdraw all military, naval, air, and police forces from China and from Indo-China.

4. The Government of the United States and the Government of Japan will not support militarily, politically, and economically any government or regime in China other than the national government of the Republic of China, with capital temporarily at Chungking.

7. The Government of the United States and the Government of Japan will respectively remove freezing restrictions on Japanese funds in the United States and on American funds in Japan.

8. Both Governments will agree upon a plan for stabilisation of the dollar-yen rate and will allocate funds adequate for this purpose, half to be supplied by Japan and half by the United States.

After reading this document Kurusu intimated that his Government would be likely ‘to throw up its hands’, but he and the Ambassador asked to see the President and were received by him the following day.

The situation was then critical. The Japanese were reinforcing their troops in Indo-China, and reconnaissance planes of the Royal Air Force reported sighting Japanese transports off the Kra Isthmus. The Commander-in-Chief, Far East, Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, asked permission to move into the isthmus if it could be proved that the Japanese were entering that territory, but the British military advisers were still afraid that any such action

might involve Britain in war. Although time was running out, the British Government hastily sought the views of the United States, as well as the Commonwealth Governments. New Zealand suggested that the Thai Government should consider the possibility of inviting Britain to defend the isthmus, in collaboration with Thai forces, and, if American support were assured, an attempt should be made to forestall a Japanese occupation. Roosevelt assured Britain of support if Japan occupied the isthmus, and the British Government instructed Brooke-Popham to despatch troops if a landing was apparent or if the Japanese violated any part of Thailand. Instructions were also issued to Brooke-Popham to put into operation plans agreed on at the Singapore Conference if the Japanese attacked the Netherlands East Indies.

These plans were the outcome of American, Dutch, and British conversations (not made public at the time) held in Singapore from 21 to 27 April 1941, at which New Zealand was represented by Commodore W. E. Parry, RN,6 Air Commodore H. W. L. Saunders,7 and Colonel A. E. Conway.8 Their fulfilment would have altered greatly the course of the Pacific war, but they were shattered first by the attack on Pearl Harbour and then by the fall of Singapore. During the conversations agreement was reached, though without political commitment, on the employment and disposition of all forces in the Indian and Pacific Oceans and in Australian and New Zealand waters, but a subsidiary interest was the security of Luzon, in the northern Philippines, as it was envisaged that threats to Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies could be outflanked, providing submarines and air forces could still operate from Luzon bases. The plans also outlined British and American commands and the operations of the United States Pacific Fleet, based at Pearl Harbour, against Japanese mandated islands and her sea communications, should an attack develop against the Netherlands East Indies. Should Luzon fall, American naval and air units were to fall back on Singapore. But Singapore fell first.

On 6 December information was despatched from Singapore that two Japanese convoys, consisting of 35 transports escorted by eight cruisers and ten destroyers, had been sighted off Cambodia Point, sailing north-west. Even then the British Government hesitated, presuming that another warning might have some effect. A draft note, in which all Commonwealth Governments and the Netherlands Government concurred, was accordingly despatched to Sir Robert Craigie in Tokyo. After referring to the deep concern of the British and American Governments at the rapidly growing concentration of Japanese forces in Indo-China and the failure of any satisfactory Japanese explanation, the note read:

There is no threat from any quarter against Indo-China, and the concentration is only explicable on the assumption that the Japanese Government are preparing for some further aggressive move directed against the Netherlands East Indies, Malaya, or Thailand. The relations between the Governments of the British Commonwealth and the Netherlands Government are too well known for the Japanese Government to be under any illusion as to their reaction to any attack on territories of the Netherlands. In the interests of peace His Majesty's Governments feel it incumbent upon them, however, to remove any uncertainty which may exist as regards their attitude in the event of an attack on Thailand. His Majesty's Governments have no designs on Thailand. On the contrary, the preservation of the full independence and sovereignty of Thailand is an important British interest. Any attempt by Japan to impair that independence or sovereignty would affect the security of Burma and Malaya, and His Majesty's Governments could not be indifferent to it. They feel bound, therefore, to warn the Japanese Government in the most solemn manner that if Japan attempts to establish her influence in Thailand by force or threat of force she will do so at her own peril, and His Majesty's Governments will at once take all appropriate measures. Should hostilities unfortunately result, the responsibility will rest with Japan.

President Roosevelt also informed the Thai Premier that the United States would regard the invasion of Thailand, Malaya, Burma, or the Netherlands East Indies by Japan as a hostile act. That same day he also addressed a message to the Emperor of Japan in a last-minute attempt to avoid conflict. Roosevelt stressed the danger of Japanese moves in Indo-China and the fears of other states in the South Pacific, finally assuring the Emperor of America's desire for peace.

At 7.50 a.m. on Sunday, 7 December 1941,9 all further negotiations ended with a surprise attack by Japanese submarines and carrier-based aircraft on Pearl Harbour, the United States naval base in the Hawaiian Islands and the only powerful base, British or American, east of Singapore in the Pacific. Nineteen ships were

hit; the Arizona and the Oklahoma, both battleships, were lost—the first was wrecked, the second capsized; three other battleships sank in shallow water and three light cruisers were damaged but were later made seaworthy, as were three seriously damaged destroyers. Fortunately the three aircraft carriers based on Pearl Harbour were absent on manoeuvres and survived to play a decisive role later in the Pacific war. Only 52 out of 202 navy aeroplanes were airworthy after the attack, which rendered the American Pacific Fleet impotent as an immediate fighting force. The Navy, Army, and Marine Corps lost 2335 officers and men killed, missing, and died of wounds, and 1143 wounded. The Japanese lost 29 pilots. Had the Japanese concentrated on the destruction of shore installations such as oil supplies, repair shops, and storage depots with the same intensity they reserved for ships of war, American recovery would have been delayed and the Pacific war consequently prolonged.

Several hours after the attack, the Emperor's reply, containing assurances of peace, was delivered to the United States Ambassador in Tokyo. At 2.05 p.m. on 7 December the Japanese envoys presented themselves at the State Department in Washington and fifteen minutes later handed to Mr. Hull their country's formal reply to the American proposals of 26 November. This document, though it contained declarations of Japan's desire to promote peace, accused the United States and Great Britain of obstructing a settlement in China and by so doing, the document alleged, ‘ignored Japan's sacrifices in the four years of the China affair, menaces the Empire's existence itself, and disparages its honour and prestige’. The document concluded that the Japanese Government could not accept the proposal as a basis for negotiation.

Hull knew that Pearl Harbour had been attacked an hour previously. He finished reading the document and then, in words almost as historical as Churchill's ‘blood and sweat’, forcefully told the envoys, ‘In all my 50 years of public service I have never seen a document that was more crowded with infamous falsehoods and distortions—infamous falsehoods on a scale so huge that I never imagined until today that any Government on this planet was capable of uttering them’.

Documents produced during the war trials in Tokyo revealed that plans for the execution of the war were well in hand while American and British diplomats were attempting to keep Japan neutral. In an ‘Outline of Japanese Foreign Policy’ dated 28 September 1940, the day after Japan signed a military alliance with Germany, the establishment of ‘Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere’ was defined as follows:

In the regions including French Indo-China, Dutch East Indies, the Straits Settlements, British Malaya, Thailand, the Philippines, British Borneo and Burma, with Japan, Manchukuo, and China as centre, we should construct a sphere in which the politics, economy, and culture of those countries and regions are combined.

(a) French Indo-China and the Dutch East Indies: We must, in the first place, endeavour to conclude a comprehensive economic agreement (including distribution of resources, trade adjustment in and out of the Co-prosperity Sphere, currency and exchange agreement, &c.), while planning such political coalitions as the recognition of independence, conclusion of mutual assistance pacts, &c.

(b) Thailand: We should strive to strengthen mutual assistance and coalition in political, economic, and military affairs.

A further document dated 4 October 1940, by which time the Dutch had refused the economic concessions demanded by Japan, gave details of a ‘Tentative plan for policy towards the Southern Regions’, of which the first paragraph read:

Although the objective of Japan's penetration into the Southern Regions covers, in its first stage, the whole area to the west of Hawaii, excluding for the time being the Philippines and Guam, French Indo-China, the Dutch East Indies, British Burma and the Straits Settlements are the areas which we should first control. Then we should gradually advance into the other areas. However, depending upon the attitude of the United States Government, the Philippines and Guam will be included.

French Indo-China:

(a) We should manoeuvre an uprising of an independence movement and should cause France to renounce her sovereign right. Should we manage to reach an understanding with Chiang Kai-shek, the Tonking area will be managed by his troops, if military power is needed. ... According to circumstances, we should let the army of Thailand manage the affairs of Cambodia.

(b) The foregoing measures must be executed immediately after a truce has been concluded with Chiang Kai-shek. If we do not succeed in our move with Chiang Kai-shek, these measures should be carried out upon the accomplishment of the adjustment of the battle line in China. However, in case the German military operations to land on the British mainland (which is to be mentioned later) takes place, it may be necessary to carry out our move towards French Indo-China and Thailand regardless of our plans for Chiang Kai-shek. (This is to be decided according to the liaison with Germany).

The United States, the Governments of the British Commonwealth, China, and the Netherlands declared war on Japan on 8 December 1941, New Zealand's actual declaration being made at eleven o'clock that morning. Japan's formal declaration of war on the United States was made after her attack on Pearl Harbour and simultaneous attack on Malaya, Hong Kong, Guam, the Philippines and Wake Islands. These attacks crumbled the weak defences

of the Allied powers. Guam, where defences were being hastened, fell on 13 December. Thailand became a Japanese ally on 21 December. The Wake garrison held out against great odds until the 23rd. Hong Kong, with a garrison of 12,000, surrendered on 25 December—a crippling loss to the Allies in both power and prestige. Two British capital ships—the Prince of Wales, a new battleship, and the Repulse, a battle cruiser, were lost on 10 December in an attempt to destroy, without air cover, a Japanese convoy off the Malayan coast. It was probably the worst ending of an old year ever experienced in the history of the British Commonwealth. By 23 January 1942 the Japanese had occupied Borneo, Timor, the Celebes, and a part of New Guinea. Singapore surrendered on 15 February and her garrison of 60,000 was lost. Rangoon, Burma's chief city, fell on 10 March, and the retreat to India had begun. British, Dutch, American, and Australian naval units heroically attempted to stem the tide while the Japanese pressed their attack on the Netherlands East Indies, but their forces were destroyed in the Battle of Java Sea on 27 February and landings were almost unopposed. The remnants of the Dutch army were finally overthrown near Sourabaya.

By 9 March the Japanese were in full control almost to the coasts of Australia, and all the immense and vital stocks of tin, rubber, food, quinine, and oil had been lost to the Allies. Small garrisons of American troops held out until 6 May on Corregidor, the last remaining foothold to surrender in the Philippines. Bataan had been abandoned on 9 April. By that time General Douglas MacArthur had been evacuated to Australia, where he landed on 17 March. Resistance had been courageous but hopeless against overwhelming numbers and the organisation and unified command of the Japanese, whose infiltration tactics and air superiority overwhelmed every line of Allied defence. By the middle of 1942 the Allies were defending on a line which enabled them to retain only a corner of New Guinea beyond the immediate Australian mainland, with island garrisons in Fiji, New Caledonia, Tonga, and Samoa beyond New Zealand. While the United States Navy held off further attacks and repaired its strength, troops and equipment moved into the island bases in readiness for the deciding conflict of the Pacific war, the battle for Guadalcanal.