Chapter 2: The Fiji Garrison

I: New Zealand's Responsibility

INFLUENCED to some degree by the Jellicoe report of 1919, New Zealand acknowledged Fiji as her immediate outpost in the Pacific, but without specifying any particular or possible aggressor. This was reiterated in every appreciation of the defence situation and in every recommendation of her Chiefs of Staff through the pre-war years, though little was done except to commit those recommendations to paper. Any fortification of Fiji by Great Britain was hampered by the provisions of the Washington Conference of 1921, which applied equally to the American base of Pago Pago in Eastern Samoa, though before the outbreak of war in 1939 certain action had been planned to meet a situation which involved New Zealand in her first conflict in the Pacific.

In 1936, when the British Overseas Defence Committee considered schemes of defence in the Pacific, it was presumed that New Zealand would provide the necessary military force for Fiji, since that Crown Colony was obviously unable to defend itself. As the rising tide of German power became more ominous in Europe and the Japanese menace created apprehension in the East, more attention was devoted to Fiji and the possible aggressor was named. In their comment to the New Zealand Government on the deliberations of the Committee of Imperial Defence in 1938, the New Zealand Chiefs of Staff—Major-General J. E. Duigan,1 Commodore H. E. Horan, RN,2 and Group Captain H. W. L. Saunders—expressed the opinion that Fiji, and not New Guinea or the Solomons, would be the more likely objective should the Japanese press an attack in the South Pacific. ‘We feel that in the past insufficient attention has been paid to these islands,’ they noted in a memorandum to the Organisation for National Security, outlining defence

measures for Fiji and Tonga. An early precautionary measure was an air survey in November 1938 by a Royal New Zealand Air Force expedition which visited outlying island groups north of Fiji. Alighting areas for seaplanes were buoyed on the lagoons of Fanning, Christmas, Hull and Gardner Islands in the Line and Phoenix Groups, and airfield and building sites were pegged out on the last three islands. This was all part of a scheme in which a series of landing fields radiated from Fiji through the Pacific, so that aircraft could be flown to any desired area should the necessity arise, as it did later. Four routes were planned: A, through the Gilbert Group; B, through the Phoenix Group; C, to Samoa, the Northern Cook and the Line Groups; and D, through Tonga and the Cook Islands.

Concrete plans for the defence of Fiji were resolved at the Defence Conference held in Wellington in April 1939, when conditions in Europe were rapidly deteriorating. These followed the recommendations of the Chiefs of Staff in 1938 and were approved by the New Zealand Government the following June. Heads of all three fighting services recognised Fiji as the key to the South West Pacific, as Jellicoe had visualised it earlier. They appreciated that an enemy force, strongly established in the group, could subdue and contain Auckland and most of the North Island by air, and that surface craft and submarines stationed at Suva could sever the Australian—New Zealand—American shipping lanes. Communication by submarine cable between the American continent and New Zealand and Australia would also be lost. As a result of this conference New Zealand undertook to maintain aerial reconnaissance along the line New Hebrides—Fiji—Tonga; establish and man an air base in Fiji; provide material and key men for the Fiji Defence Force; despatch an infantry brigade group to the colony when it was required and arrange for the construction of two landing fields—one at Nandi, on the west of the island of Viti Levu, and the other at Nandali, near Nausori, 15 miles from Suva on the Rewa River. The proposed capital expenditure for these projects suggests that New Zealand was acutely conscious of her responsibilities; future events confirmed it. Financial responsibility for the defences of Fiji was arranged on a pool basis—the Fiji administration contributing £500,000 a year, half of which was advanced on loan by the United Kingdom Government. New Zealand was to meet any expenditure over and above that amount.

Maintenance costs for the forces established in Fiji were met by the New Zealand Government, but a solution to financial questions concerning the defence of the Crown Colony was not reached without lengthy negotiations by Treasury officials and long despatches

between the three governments concerned—the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Fiji. Separate agreements were reached on the cost of various works and installations—for example, the capital cost of the airfields was met equally by the New Zealand and United Kingdom Governments, whereas the cost of the marine airport at Lauthala Bay was met by New Zealand and Fiji. The preliminary estimates, drawn up as a result of the Wellington conference in 1939 but which afterwards required much adjustment between governments, provided for the following costs:

Navy £25,680—of which £20,000 was set aside for oil storage tanks.

Army £290,000—including £245,000 for buildings.

Air £692,000—including £400,000 for the purchase of new aircraft, if they could be procured.

The proposed annual expenditure was estimated at:

| Navy | £8750—which included £3000 for pay and rations. |

| Army | £1,156,000—including £876,000 for pay and rations. |

| Air | £180,000—including £60,000 for pay and rations. |

A meteorological organisation costing £3300 was also recommended and later approved, New Zealand to pay 50 per cent of the cost, the United Kingdom and Fiji each 20 per cent, and the Western Pacific High Commission 10 per cent. These estimates also required adjustment as the scheme matured.3

Fiji's small defence organisation, consisting of a headquarters, signal unit, and one weak Territorial battalion under the command of the Commissioner of Police, Colonel J. E. Workman, was little more than a token force, but it provided the framework for expansion on the outbreak of war in Europe when, like so many other Empire outposts, she began hurriedly to put her small military house in order. The size of it is indicated by the Governor's authority, signed in September 1939, raising the full-time officers from one to four. New Zealand began immediately to honour her commitments. Five hundred rifles and sets of web equipment were sent to arm the new recruits. At the end of September HMS Leander made a hurried dash to Suva with two heavy guns, which were unloaded and emplaced under cover of darkness. They were dummies, carried ashore by two sailors. It was part of the policy of deception forced on authority by circumstance in those first confused days of the war. Four instructors followed in November—Captain H. G. Wooller, WO I D. W. Stewart, WO I C. E. Burgess,

and WO II C. Turner. Stewart and Burgess afterwards became captains with the Fijian forces, and served with them in the Solomons. Then, on 5 June 1940, New Zealand decided to raise and train an infantry brigade group for Fiji, the force to consist of 2908 all ranks, increased before departure to 3053. This scheme was originally envisaged as a combined garrison and advanced training ground for reinforcements for 2 NZ Division in the Middle East, the First Echelon of which had left New Zealand on 6 January. It provided for the relief of the men after six months’ service, after which they were to return to New Zealand to become reinforcements for the force in Egypt. Later events in the Pacific required drastic modification of this scheme.

Before the arrival of the brigade in Fiji a good deal of preliminary work had been either outlined or accomplished. Early in 1940 work began on the airfields at Nandi and Nandali by New Zealand construction units. Two modest 4.7-inch naval guns from the United Kingdom replaced the dummies and were sited on Mission Hill behind Suva by Lieutenant-Colonel F. N. Nurse, Royal Australian Artillery, and two New Zealand instructors, Battery Sergeant-Major A. Wainwright and Sergeant S. Wilce, who left New Zealand in October 1939 to organise and train staff and men for this coastal battery. When Major B. Wicksteed, RNZA,4 took over command of the battery in March 1940, the guns startled Suva residents in their trial shoots, the range of 10,500 yards enabling shells to fall beyond the reef which protected the harbour. Wicksteed took ten trained New Zealand gunners with him to hold key posts and mould the native Fijians who had been selected for training. General satisfaction was expressed by the townsfolk that some defence was at last obvious, even though these guns would have been about as useful as a catapult against the heavy armour of a modern warship.

Meanwhile, a desirable martial spirit had exercised the Territorial Force, which had been increased to 31 officers and 743 other ranks, who were guarding vital points in the Suva area when they were not training; 11 officers and 286 other ranks were similarly employed and disposed over the Lautoka-Mba-Vatukoula area. Major C. W. Free, MC,5 a New Zealand officer who had been in the Indian Army, joined the headquarters in August 1939 as staff officer G, and the number of instructors from New Zealand, both infantry and artillery, was increased to sixteen by 1940. When the

Niagara was sunk outside Auckland on 19 June 1940, Captain G. T. Upton's6 arrival at Suva was delayed, but only long enough to enable him to replace some to his kit. He took over command of the Suva Regular Company on 13 July 1940, and remained with the Fiji Defence Force until the end of the war, ultimately commanding a battalion. But Fiji was deplorably short of equipment at that time. Gunners practised their gun drill, with some degree of reality, on two ancient three-pounder guns discarded years previously and salvaged from a Public Works store; connecting rods from a captured 1914–18 German machine gun were brought out of the museum to enable a Vickers gun to operate.

Much the same state of affairs existed with a coast watching system which had been organised by the civil administration to cover the islands of the group and report the presence of hostile shipping. Natives maintained a twenty-four hour watch at the more important vantage points, relaying their information by a variety of methods to a central station at Suva, where it was examined and the more important facts sent on to New Zealand. Efficient wireless equipment was lacking, and weather played havoc with the two-way sets then in use on only a few of the more important outlying islands, such as Kandavu. The long-distance telephone system on Viti Levu was little better than wireless and so temperamental from a variety of reasons as to be useless quite often. On many distant island stations communication was by canoe or pre-arranged smoke signal, a system much at the mercy of unpredictable elements. Breakdowns in this primitive system were frequent and inevitable, but it was the only one possible at the time and until more efficient equipment became available. Natives, often without shelter, were wonderfully loyal. Though they were unaccustomed to long and boring hours of this voluntary work in all weathers, they performed a magnificent task, reporting the movements of ships and aircraft in a queer formula devised for their use. It is not surprising that they did not pick up the German raider Orion, which cruised off the group from 19 to 23 July 1940. Communications were not satisfactorily or efficiently organised until 1941, when Mr. L. H. Steel, of the New Zealand Post and Telegraph Department, took them in hand when he was appointed Controller of Pacific Communications, with headquarters in Suva.

Deterioration of relations with Japan, and events in Europe after the fall of France, hastened the Fiji defence preparations and the departure of a force to the Colony. At the end of July the three New Zealand Chiefs of Staff, General Duigan, Commodore W. E.

Parry (who had replaced Horan as Chief of Naval Staff), and Air Commodore Saunders sailed for Fiji in HMS Achilles, accompanied by Colonel W. H. Cunningham, CBE, DSO,7 who had been called up from the reserve of officers to command the new brigade, and Major E. R. McKillop,8 of the Engineers. They spent four days considering troop dispositions and defence measures and conferred with the Governor, Sir Harry Luke, KCMG, before returning to Wellington, where they recommended the immediate despatch of the brigade to garrison Viti Levu and certain assistance in men and material to the Kingdom of Tonga. Cunningham and McKillop remained in Fiji selecting camp sites and drafting preliminary details of a defence scheme before returning to New Zealand in August.

On 20 September, seven days before Japan signed a military alliance with Germany and Italy, Cunningham, promoted to the rank of Brigadier, opened his headquarters at Ngaruawahia Camp. Although his command was officially designated 8 Infantry Brigade Group, it became B Force for purposes of organisation and despatch. Meanwhile, McKillop returned to Fiji to supervise and push forward the construction of camps in which to house the brigade. He was followed in August by an engineer unit originally destined for the Middle East—18 Army Troops Company under Major L. A. Lincoln,9 which also acted as advanced party for the main force. By the time the engineers arrived, McKillop's small army of 500 Fijian and Indian labourers was altering a landscape which had not suffered such mutilation for centuries, as they toiled from dawn to dusk seven days a week preparing camp sites. In a region where typhoid fever and dysentery were prevalent, hutted and mosquito-proof camps were essential. Major J. R. Wells, NZMC,10 preceded the main force and prepared a voluminous report which recommended the chlorination of all drinking water, fly-proofing of food stores, mess huts, and kitchens, in addition to septic tanks and underground drainage for camp areas. These were necessary if the

health of troops was to be maintained in a climate where broken skin turned to septic ulcers, and the continual bites of mosquitoes led to dengue fever and constant irritation. Because supplies of fresh meat, butter, and vegetables were almost unobtainable in Fiji and required by the civilians, most of these perishable stores were brought from New Zealand. It was some months, however, before the medical recommendations could be made fully effective.

There was much preliminary work to be done in great haste in both New Zealand and Fiji. Cunningham was unable to build up a fully trained staff, and the greater part of his brigade strength was retained from the Third Echelon, then being trained and equipped for service in the Middle East. Many of his headquarters staff and the battalion commanders had seen service in Egypt and France in 1914–18 and were referred to as ‘retreads’ by the younger generation. During organisation, also, components of the brigade were widely scattered. The 29th Battalion and 30 Battalion were trained and partly equipped at Ngaruawahia and Te Rapa. Two reinforcement companies, which by a process of evolution became the Reserve Battalion and then the 34th, 35 Field Battery, 20 Field Company, and 4 Composite Company, ASC, were all at Papakura. At Trentham 7 Field Ambulance and various details such as Pay, Records, Ordnance, Provost, and Signals were assembled for departure, so that units knew little of each other until they reached their destination. All of them were short of much essential equipment, and some of the men had been in camp only a few days before they sailed. They drew their equipment as it came to hand, some of the men visiting the quartermaster's stores as many as fifteen times. The fact that they were the first members of 2 NZEF to be issued with New Zealand made battle dress was little compensation for the long delays in obtaining equipment. Infantry units took turns in borrowing machine guns for training. Because of its distance from New Zealand and the task to which it was assigned, Cunningham's small force included units which normally were associated with a higher formation. It was equipped and maintained from New Zealand's own meagre supplies, which at that time were not sufficient even for her home defences.

Appointments to 8 Infantry Brigade Group on its arrival in Fiji in November 1940 were:

| Officer Commanding | Brig W. H. Cunningham, CBE, DSO |

| GSO 1 | Lt-Col C. W. Free, MC |

| GSO 2 | Maj J. H. Irving |

| Construction and Works | Lt-Col E. R. McKillop |

| AA and QMG | Maj G. T. Kellaway, MC |

| Supply Officer | Capt R. C. Aley |

| Intelligence Officer | Lt O. A. Gillespie, MM |

| Transport Officer | Lt C. A. Voss |

| Signals Officer | Lt L. C. Stephens |

| Pay | Capt W. P. McGowan |

| Records | Lt G. A. R. Johnstone |

| Provost | Lt A. L. Downes |

| Dental Officer | Capt H. A’C. Fitzgerald |

| 29 Battalion | Lt-Col H. J. Thompson, MC |

| 30 Battalion | Lt-Col J. B. Mawson, MC |

| Reserve Battalion (afterwards 34 Battalion) | Maj F. W. Voelcker, MC |

| 35 Field Battery | Maj C. H. Loughnan, MC |

| 20 Field Company, Engineers | Maj R. J. Black, MC |

| 4 Composite Company, ASC | Maj A. Craig |

| 7 Field Ambulance | Lt-Col P. C. Davie (also senior medical officer) |

Early in 1941 several changes took place and the staff was slightly increased: Free returned to India and his place was taken by Lieutenant-Colonel J. G. C. Wales, MC; Lieutenant Noel Erridge arrived to become Ordnance Officer, and Matron G. L. Thwaites arrived with a small nursing service with which to staff the military hospital.

II: The First Force and its Work

When New Zealand troops of the brigade landed in Fiji on 1 November 1940 they made history. It was the first time a defence force from a self-governing dominion had been sent to garrison a Crown Colony of the Empire. The brigade moved there in three flights, the first leaving Wellington on 28 October in the Rangatira after the traditional speeches of farewell from the Governor-General, Lord Galway, the Prime Minister, the Hon. P. Fraser, and the Minister of Defence, the Hon. F. Jones. HMS Monowai,11 a converted cruiser, was both escort for the convoy and transport for the field artillery. After disembarking troops at Suva the Rangatira ran a shuttle service, transporting the remaining two flights, one of which went direct to Lautoka, in the west. By the end of November the brigade was established in Fiji and enduring all the initial discomforts which attend a military expedition organised and despatched in haste, particularly to a hot and exhausting climate. Fiji, 1100 miles north of New Zealand, was new and unknown territory to most members of the force who were making their first acquaintance with the tropics, and in circumstances which gravely

disillusioned them as reality dispelled any romantic guide-book nonsense about tropical islands.

The Crown Colony of Fiji, consisting of 250 islands, was ceded to Great Britain in 1874. Thakambau, an influential chief, had previously offered the territory to Britain for the modest sum of £9000, and also to the United States. The British Government rejected the first offer; accepted a second. The United States Government did not even bother to reply. The group lies in the hurricane belt, 15 degrees south of the Equator. Temperatures range from an average of 91 degrees in summer to 62 degrees in winter. One feature of the group, like so many other Pacific islands, is that each island has its wet and dry side, with a vastly differing rainfall. In the eastern area, which has an exhausting, humid climate, the average is 120 inches a year and sometimes 200 inches; in the west 70 to 80 inches fall annually. Suva, port, capital, and seat of Government, spreads its homes and gardens over a peninsula on the eastern coast of Viti Levu, the largest and most populous island, with the shopping areas and Government buildings on the water-front. Vanua Levu, the second largest island, lies to the north but is sparsely inhabited. Smaller islands of varying size, some of them merely atolls and banks, dot the seas around the two large islands. Coral reefs act as a natural defence line, with openings only at mouths of rivers and freshwater streams. The group is so situated that all trans-Pacific shipping lines converge on Suva, a town of 13,000 inhabitants, mostly Indian and Fijian. In addition to a moderately good harbour inside the reef, there is a vast stretch of protected water known as Lauthala Bay where, on the outbreak of war, a seaplane base was being constructed. New Zealanders watched the arrival there of the first regular American clippers on the trans-Pacific service, which ceased with the attack on Pearl Harbour; but work on the base continued and it proved an invaluable asset during the war years.

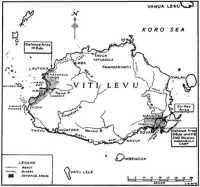

Cunningham decided to defend the two most vital areas on Vitu Levu—the Suva Peninsula in the east, with its harbour facilities, communications, cable link, supply depots and stores, and the Nandali airfield, 15 miles away on the left bank of the Rewa River; and the Namaka area in the west which included the small town and port of Lautoka, the Nandi airfield (later to play a vital part in Pacific strategy), and the Navula Passage, the entrance to Nandi anchorage, which was overlooked by the barren, rolling hills of Momi. These two zones were 150 miles apart, linked by one circular coastal road and, when it was organised later, a modest air service, operating when weather permitted between the two airfields. The confusing jumble of densely wooded hills of Viti

Cunningham's plan of two defended zones on the island of Viti Levu in Fiji is indicated by the shade areas. They were joined by one narrow coastal road.

Levu made cross-country communication impossible. Cunningham's problem was to defend those two vital zones with the inadequate force at his disposal, and its solution was made more difficult by the lack of armament and transport and the necessity of dividing his engineers, medical, signal, and supply units to service each zone. There were problems on a Government level also, for accommodation and public utilities were lamentably short in a remote island catering for seasonal tourists and a small white population of only 4000 Europeans.

Two principal camp sites were selected, one at Samambula, four miles from Suva, beside the golf links where undulating country met all reasonable requirements, and at Namaka, 17 miles from Lautoka, in the western coastal region of sugar-cane and pineapple plantations. Hutted camps were not ready when the force arrived, despite the sweating efforts of the engineers, and units went under canvas. Heavy rain, falling in warm grey torrents almost daily,

hindered construction work in the Suva zone, and the immediate camp areas soon bred a profane familiarity with the adhesive qualities of Fiji mud. Earth-moving equipment, heavy or light, was not available, and picks and shovels were not wielded with any great degree of urgency by natives long accustomed to leisurely movement in the heat. Progress was faster in the dry Namaka area, where a camp of 400 Public Works type huts was constructed.

Force Headquarters opened in the basement of Government Buildings in Suva until suitable accommodation was constructed early in the New Year round Borron's House, a private residence crowning a hill overlooking the town and the long, creaming surf ceaselessly breaking along the reef beyond. The 29th and Reserve Battalions, with ancillary services, were stationed at Samambula in tents, gradually taking over the standard 84 ft by 21 ft huts as they were finished at McKillop's constant urging. Headquarters staff was housed in hotels in the town or at Nasese, a Fiji Defence Force camp some distance away, and from which they marched to duty each morning in a lather of perspiration until a transport truck was made available to them. The 30th Battalion went direct to Lautoka from New Zealand, travelling from ship's side to camp area in the Colonial Sugar Refining Company's unique railway, the only one in the Colony and used principally for hauling cane to the crushing mill. The immediate fortification of the area, with 50 miles of coastline, was put in hand by Mawson,12 who also became area commander. On 6 November Cunningham was appointed Commandant of the Fiji Defence Force, with operational control over all land forces in Fiji, Tonga, and Fanning Island. Fiji units were absorbed into his command, 1 Battalion remaining in the Suva area and 2 Battalion at Namaka under Mawson. However, the Fiji Defence Force retained an administrative headquarters, under Lieutenant-Colonel J. P. Magrane, when Workman relinquished command after Cunningham's arrival.

At Cunningham's first unit conference on 4 November, areas were allotted and defence roles defined. The immediate task was the denial to a possible enemy of the beaches and harbours in both zones. Four of 35 Battery's 18-pounder guns were despatched to Momi to defend the Navula Passage between the mainland and Malolo Island; the remaining two guns were sited at Lami village to cover the entrance to Suva Harbour and assist the fixed guns sited on Mission Hill behind the town. Belts of barbed wire were erected inland along the waterfront at low-water level on the more vulnerable beaches. These were covered by machine-gun posts, gun

emplacements, and systems of trenches designed as alternative positions in the defence scheme. Roads were constructed by the engineers through both zones to give the battalions greater tactical mobility. By and large the Colony derived benefit from these defence preparations, for they gave it a fulfilled public works programme unthinkable in years of peace. These new roads, to this day commemorating the names of the first commanders, Cunningham and Mead, enabled the ASC to site supply dumps at strategical points throughout the defended areas in accordance with Cunningham's policy of building up a three months’ reserve of oil and petrol and six months’ reserve of rations, slowly accumulated as they arrived from New Zealand. The influx of thousands of troops naturally strained the limited public amenities of Suva and created some difficulty, particularly in the supply of water and electric power to camps and barracks. Unaccustomed to the heat and constant sweating, each man used an average of 80 gallons of water a day which even a bountiful rainfall could not hope to replenish. Restrictions were ordered by Cunningham, who was required to satisfy both civil and military authorities.

Much had been accomplished by the turn of the year, mostly by hard labour and the vigorous use of pick and shovel. Major difficulties were overcome, and the men became hardened to heat, mosquitoes, rain, and improvisation. Those who were allergic to the tropics never became accustomed to any of these things and voiced their sentiments in long, outspoken letters home. Soon their bodies were burnished to the colour of mahogany as they toiled in shorts, hat, and boots securing the defence lines. Gunnery and air problems were discussed by the commander with Colonel A. B. Williams, DSO,13 Director of Artillery at Army Headquarters, and Group Captain A. de T. Nevill,14 of Air Headquarters, who were among the first senior officers to arrive for consultations—Williams to advise on the siting of fixed guns; Nevill on air services. Two 6-inch naval guns intended for the defence of Lyttelton Harbour had been diverted to Fiji by the New Zealand Government to replace the 4.7-inch on Mission Hill. The smaller guns were then transferred to a site which also commanded the harbour entrance but from the opposite side. Engineers sealed off the defence zones with road blocks and arranged for the demolition of bridges on

their boundaries. The Suva Girls’ Grammar School was taken over and transformed into a military hospital, with Matron Thwaities15 in charge of a nursing staff which worked long hours to cope with ailments provoked by heat and a violent change of climate, and made worse by an epidemic of measles which coincided with the arrival of the force.

Shortages were the predominating worry, but these could not be met immediately by New Zealand, though appeals had been made overseas for additional equipment. Clothing was a problem which caused irritation among the men. Much of the tropical kit with which they had been issued—shorts and shirt suitable for the climate—was ill-fitting and bore the date of their manufacture in 1917. This was remedied later by the employment of Indian tailors, but in the intervening periods many of the men equipped themselves with more presentable garments made by local tailors. Increased issues of better fitting shirts, shorts, tunics, and long trousers stilled the complaints and pointed a moral for the equipment of similar expeditions. Tunics which buttoned closely to the chin were later discarded in favour of open-necked shirts.

During the early months of the Fiji expedition, complaints reached New Zealand from those who were returned unfit for further service and others who wrote petulantly about the unsuitability of both clothing and rations, the attitude of the white residents, the lack of recreational facilities, and the high prices of tobacco and drinks. Cunningham, in one of his replies to the Minister, pointed out that such complaints ‘put senior officers to unending trouble endeavouring to answer the unanswerable. Complaints of a general nature, incapable of exact answer, exasperate one beyond endurance, particularly in this climate’. Davie,16 the senior medical officer, who had protested that many of the men sent to Fiji were unfit and that their ailments were aggravated by the heat and the prevailing conditions, reported very fully on a series of these complaints, stating that the few white residents of the Colony welcomed troops to their homes in a way unheard of in New Zealand. He concluded that the majority of the men were as happy as they could be without the stimulus of actual fighting. Investigation usually revealed that the complaints came from the usual small percentage of malcontents without which no armed force is complete. Generally speaking, the soldiers realised

their responsibilities. When Brigadier F. T. Bowerbank,17 Director-General of Medical Services, visited the force early in 1941 he reported that the health of the troops was good.

The authorities did all they could to provide amenities, and the residents themselves responded with enthusiasm. Churches of all denominations opened clubs and organised dances and concerts; the small European colony of Government officials and business and professional men opened their hospitable doors as wide as they were able; trading companies organised weekend picnics, and golf and tennis clubs offered the use of their courses and courts. YMCA representatives began in a modest way in the camps and provided some relief from boredom in the evenings. Finally a New Zealand Club, erected on the Suva waterfront by the National Patriotic Fund Board, provided a rendezvous for all, day or evening, and here the women of Suva emulated their Trojan sisters in hours of work.

During weekends and holidays parties of soldiers visited the more distant villages, where they were received by the hospitable Fijians and initiated into traditional kava-drinking ceremonies. From time to time, also, representative Fijians, smart in spotless white sulus and coats of European cut, visited the military camps bearing gifts of fruit and vegetables which supplemented menus not overburdened with fresh foods, most of which came from New Zealand and much deteriorated on the way. Refrigerated space was at a premium during the first year, but large cool-stores finally overcame the food problem. The New Zealand soldier dislikes being deprived of his customary meat, potatoes, and butter in generous quanity, and he soon grew tired of native fruits like pawpaw and pineapple, and vegetables such as yam and dalo were not to his taste. An endeavour to provide fresh fruit and vegetables from Fijian sources cost £500 a month. These were only a few of the growing pains of garrison duty on which 8 Infantry Brigade embarked without adequate provision and little advance preparation.

Although training was hampered by the shortage of mortars, grenades, and sub-machine guns, a certain amount was accomplished and provided relief from the construction of defence works. The brigade was still short of 66 of its motor vehicles in December. Picks, shovels, and other digging implements were so short that units took turns in using those available, and other construction material was obtained from the Fiji Public Works Department on

a ‘beg and borrow’ basis. However, through 1941, the force was built up and the defences improved as equipment slowly reached Fiji, but the distance from any active sphere of operations and the effects of the heat could be noticed in the attitude of the soldiers to service in the Colony. Digging and wiring, route-marching and guard duties, limited tactical exercises by day and night drained their enthusiasm and increased their desire for relief. In the sunbaked, waterless region of Momi, infested with flies and mosquitoes, and among the dry sugar plantations of Namaka, units of 30 Battalion and 35 Battery endured great physical hardship, relieved now and then by visits to lovely Sawani Beach, one of the few which really conformed to the standards of the tourist pamphlets. But it was a grim period for the men.

As soon as Force Headquarters was established at Borron's, with offices grouped round the main building on the hilltop, a combined operations centre was organised for the smoother and more efficient dissemination of all intelligence information pooled by representatives of the three services. Lieutenant-Commander P. Dearden, RN,18 whose service in the 1914–18 War had been summarily interrupted at the Battle of Jutland when his ship blew up, arrived in January to assume the duties of resident naval officer which, until then, were performed none too satisfactorily by Fiji Customs officials. The naval officer routed all shipping which passed through the group as part of the routine to avoid loss from enemy raiders, both surface craft and submarines, any knowledge of whose presence in and around the group was essential to naval intelligence in New Zealand. Coastwatching was also linked in with naval intelligence, and a workable system gradually emerged from the more primitive though useful original.

Reports from untrained but enthusiastic Fijian coastwatchers were responsible for much fruitless investigation but, however fantastic, they were never disregarded. Submarines invariably proved to be floating coconut logs, including one which was reported to have taken on fresh water and vegetables in an unfrequented bay, and another with the crew busily engaged in cleaning the hull on the beach. Suspicious lights were fishermen on the reefs, using flares at night as they have done for centuries; one aeroplane, complete with navigation lights, was a weather balloon released by Flight Lieutenant W. R. Dyer, of the meteorological staff; gunfire proved to be thunder, which it closely resembles in the tropics, and, on one occasion, a stranded whale threshing madly on a reef.

All such reports were investigated by air, if the weather was suitable. Squadron Leader D. W. Baird, RNZAF,19 operated a small air force detachment consisting of two de Havilland 89s and two de Havilland 96s which had formerly served a civil air line in New Zealand, and a Moth for training. Two of these aircraft were stationed at Nandi under command of Squadron Leader G. R. White.20 In addition to identification of ships in waters round the group, Baird's aircraft maintained a regular service between the east and west zones and made reconnaissance flights to Tonga. The first of many alarms that German raiders were off the coast occurred on 25 November 1940, when a coastwatcher at Momi reported an unidentified armed merchant cruiser off the coast. Battle stations were occupied by 30 Battalion with commendable speed, and Flight Lieutenant E. N. Griffiths, who was afterwards killed while piloting an Airacobra, flew over the ship and identified her as HMS Monowai. When night operations began on a brigade scale in 1941, Baird, who was also air adviser to Cunningham, flew his training Moth over the defences, dropping dummy bombs of homely flour as the troops moved to their positions in the early hours of the morning.

During January and February of 1941 the men experienced their first real rainy season, when the warm, moisture laden atmosphere produces mildew overnight inside hats and boots and even on tin trunks. With it came persistent hurricane rumours but, as none had visited Fiji for some years, they were ignored. February opened with oppressive heat and torrential rainstorms, producing conditions which, in the tropics, breed short tempers and imaginary slights and a disposition to procrastinate—conditions rather difficult to control and collectively referred to as malua. On 19 February the meteorological section of the RNZAF issued a warning that a storm of some violence might be expected as the erratic course of a hurricane was plotted, zigzagging at sea between Fiji and Tonga. It broke the following morning—the worst hurricane experienced in Fiji for twenty-one years. Warnings were issued to all units as the day broke with leaden skies and an unusual gusty wind. All tents were struck in both areas, canopies were removed from motor vehicles, and buildings were hurriedly wired and strutted to withstand a gale.

By nine o’clock the wind increased to tremendous force, driving in from the sea a wall of warm grey rain which stung like hail. Two hours later the hurricane was raging at its height. Huge trees toppled and snapped; palms bent so that their crowns of fronds swept the earth like dusters; sheets of corrugated iron whisked through the air like postage stamps or were wrapped round tree trunks like paper. At 11.15 a.m. the wind reached 110 miles an hour, but as the recording instruments broke at that time no accurate record was ever established. Telephone and power lines went down under the weight of wind and wreckage. One military line survived until midday, and when it broke headquarters was isolated from all units except by a wireless link which maintained communication with Namaka only with extreme difficulty.

Late in the afternoon, when the hurricane dissolved in heavy rain, the landscape looked as though it had been stripped by locusts. Tangles of branches, wreckage, and wires blocked streets and roads. Three ships in the harbour, which had escaped from Nauru Island when their convoy was shelled on 6, 7 and 8 December by the German raiders Orion and Komet, were driven high on mudbanks. Two aeroplanes, exactly half the RNZAF's strength in the Pacific, were wrecked on the Nandali airfield, where they had been tied down. Six buildings were blown down in Samambula Camp, and others, including officers’ quarters at Borron's House and a motor transport workshops at Samambula, were leaning at crazy angles. Camps in the Namaka area escaped with heavy flooding, though the Nandi River rose 30 feet.

That evening the quartermaster's store at Samambula caught fire because of the faulty handling of petrol, destroying a quantity of equipment and ammunition. The day's damage was estimated at £1725 but no lives were lost, though escape from injury was miraculous. One supply convoy, returning by the northern coastal road from Namaka, was trapped by swiftly rising water and marooned for 36 hours, as were other parties moving along the south coast road, where bridges were washed away and slips prevented all traffic for several days. Calls for assistance were made on all units, and for a week gangs of infantrymen cleared debris from roads and streets, often with borrowed saws and axes. Engineers went to the aid of the Fiji Public Works Department, and men from Signals assisted the Post and Telegraph Department to restore and repair their grievously damaged services in both town and country. A special message from the Governor expressed the thanks of the Colony for military aid. Torrential rain continued through April, blocking roads and flooding coastal areas. Forty

inches fell in twenty-three days, sometimes at the rate of two inches an hour, which hindered both work and training.

In an effort to give variety to garrison life, 29 and 30 Battalions periodically exchanged areas throughout the year. A tour of duty in the Suva area certainly broke the monotony of life at Momi and Namaka. Early in May full-scale manoeuvres, made as realistic as possible despite shortages of equipment, began with alarms at midnight or the early hours of the morning. At the end of that month Cunningham submitted to New Zealand a list of equipment still vitally necessary for the efficient operation of his force. This included two 18-pounder guns to complete the establishment of 35 Battery; mechanical transport for both 35 Battery and 34 Battalion, which had now emerged from the chrysalis of the Reserve Battalion; fighting and training equipment, including twelve Lewis and four Vickers machine guns for 34 Battalion; trench mortars and Bren guns for all infantry units; medical supplies which were lamentably short; signals equipment; and tools for 20 Light Aid Detachment which, at the end of six months’ exacting work, kept the brigade's limited transport on the roads only with the greatest difficulty.

Manoeuvres were interrupted by the first of the reliefs, two sections (1708 all ranks) of which arrived on 23 and 29 May in the Rangatira, escorted by HMS Achilles. The remaining 1500 members of the relief did not arrive until the following August. The first departing troops sang their way lustily out of Suva and enjoyed leave in New Zealand before going on to join 2 Division, which by then had been blooded in the Greek campaign and was ending the ill-fated but valiant attempt to hold Crete. Only senior and administrative officers and non-commissioned officers of the original brigade remained in Fiji when the relief was completed. The new arrivals, for the most part untrained, contributed little to the efficiency of the force, as training had to begin again at the individual, platoon, and company level. A shortage of efficient non-commissioned officers was relieved by the formation of a training school at Natambua, commanded by Major J. H. Irving, whose place on headquarters staff was taken by Major A. J. Moore.

The defence scheme was drastically modified after a visit from General Sir Guy Williams, KCB, CMG, DSO, military adviser to the New Zealand Government and a former area commander in England with considerable experience in preparing and devising anti-invasion measures. After spending a week inspecting the defences of both Fiji and Tonga in July, he returned to Wellington and advised that operational control of all defence measures in both groups should be undertaken by New Zealand.

Such an agreement, in which the United Kingdom Government concurred, was signed in Suva on 18 November by the Hon. F. Jones, Minister of Defence, the Hon. J. G. Coates, Minister of the War Cabinet, and Sir Harry Luke, Governor of Fiji. From that date New Zealand assumed responsibility for the defence of British possessions in the South West Pacific, and was accorded the power to approve all defence works.

Before this agreement was signed, Cunningham was irked in the execution of his defence plans by long delays in obtaining approval for both works and expenditure from the New Zealand War Cabinet and the Governor of Fiji. The Chiefs of Staff, including Lieutenant-General E. Puttick,21 who had returned from the Middle East and replaced Duigan at Army Headquarters, and Mr. Foss Shanahan, secretary to the Organisation for National Security, accompanied the Ministerial party and inspected the island's defences. It was also the occasion for conferences with officials on costs, expenditure, and other subjects arising from New Zealand's participation in Pacific defence.

The Williams report went very thoroughly into the state of the brigade, listing its deficiencies but commending the work accomplished and the high morale of the troops. It also emphasised the unit shortages of light automatic weapons, first-line transport, and signal equipment; the army required at least 400 beds; the aeroplanes had an operational radius of only 250 miles; reinforcements had been sent to Fiji after only ten days’ training. His recommendations included a supply of 3-inch mortars and armoured vehicles; three months’ basic training for all men sent to Fiji, petrol supplies to go underground; the blocking of all subsidiary channels through the reefs; the development of Fiji as a naval and air base, and the establishment of wireless communication linking islands of the Pacific with a central station in Suva. Williams based his appreciation of any Japanese attack on Fiji at a strength of one infantry brigade with tanks, supported by carrier-based aircraft and naval vessles. His most important recommendation was an extension of the minimum tour of duty to one year, since the relief of the garrison every six months made efficient training impossible.

This report emphasised the difficulties under which Cunningham worked. New Zealand did its best to repair the deficiencies by putting the Williams recommendations into operation as quickly as

possible, but 24 Bren guns, 12 Lewis guns, and some Thompson sub-machine guns did not arrive until September.22

There were large quantities of other stores, including signal equipment, still required for Fiji, and Tonga was still short of 75 rifles and 24 Bren guns for its small garrison. Completion of defence works was pressed forward throughout the year.

Before the end of July twenty-two soldiers, selected volunteers from the brigade, were despatched as companions to fifteen wireless operators from the New Zealand Post and Telegraph Department to maintain stations scattered through the Gilbert and Ellice Groups, north of Fiji. This series of coral atolls extended almost to Japanese-held territory in the Marshall Islands, from which information was urgently desired by both War Office in London and the Army Department in Washington. These men were the first New Zealanders killed and taken prisoner by the Japanese, and their dauntless story is told later in this volume.

Japan's provocative attitude lent a spur to activity both above and below ground. Cunningham's plan of defended zones transformed twelve square miles of the Suva Peninsula into an area rather like a moated, mediaeval castle on the grand scale, but in this instance enclosing the whole town and the immediate countryside and villages. It was flanked by two rivers, the Lami on the right, the Samambula on the left, and between them anti-tank ditches linked such natural features as ravines, swamps, and hills, extending five and a half miles island to Prince's Road to include a new 300-bed military hospital erected at Tamavua, all supply and petrol depots and the water pumping stations, as well as deep and spacious underground quarters for the use of the Governor and his staff in an emergency. Along seven and a half miles of vulnerable beaches, a six-foot concrete wall, requiring 460 tons of cement, acted as a tank stop should the enemy enter over or through openings in the reef. Belts of barbed wire and trench systems provided alternative lines of defence behind the beaches.

| Motor cycles | 83 |

| Trucks, 15- or 20-cwt. | 33 |

| Water trucks, 15-cwt. | 3 |

| Trucks, 30-cwt. | 29 |

| Trucks, 3-ton | 72 |

| Bren guns | 192 |

| Grenades No 36 (25 per cent smoke) | 6000 |

| Mortar bombs, 3-inch | 1500 |

| Mortars, 3-inch | 18 |

| Bren carriers | 42 |

| Rifles | 400 |

| Carbons for searchlights, positive | 2000 |

| Carbons for searchlights, negative | 700 |

Such a definitely enclosed area was not possible at Namaka and Momi, where an undulating plain ran back from sandy beaches to low hills, but the best use was made of natural features, belts of barbed wire, and demolitions to protect camp areas, the airfield, and a 50-bed hospital at Namaka. Momi became a separate area under the Namaka command, and the two 6-inch naval guns emplaced there in May were enclosed in a system of wire and trenches. Suva was regarded as the last line of defence for the Colony should an attack develop, and any force moving from Namaka to Suva's aid was ordered to take the northern coastal route because of the vulnerability of the southern road from the sea.

Any detailed account of the work accomplished in constructing these defences implies long hours of manual labour by all troops of all units, including the medical units, and it continued with deadly monotony for months. The achievements reveal the story—one of constant burrowing into the soapstone, a variety of soft rock found in Fiji, and removing the spoil in barrows; and wiring and digging and filling sandbags. In September 1941, before 30 Battalion returned to the western area to permit 29 Battalion's return to the more civilised region of Suva, the 30th had used ‘21½ miles of barbed wire, and made 330 knife-rests, erected 4200 stakes for wiring the beaches and mangrove swamps, cut 2500 feet of mangrove posts for roofing, and filled and used 25,500 sandbags’. Fifty-five defence posts with bullet-proof overhead cover had been constructed, fire lanes 950 yards long and nine yards wide had been cut through mangrove swamps, and twelve storage tunnels each 15 feet by seven by six had been gouged in the soapstone hillocks. Later, when it arrived, 35 Battalion erected 18,000 yards of barbed wire in a month. These figures indicate, in a modest way, the work done by units which at the same time continued with their training. They also indicate the extent of the fortifications in Fiji—fortifications which were never used but anticipated an enemy attack. Men frequently worked in the evil-smelling mud of the mangrove swamps, sometimes knee-deep in water. They assisted the engineers by removing spoil from underground excavations, where compressors chattered incessantly. One task of some magnitude was the completion, by the end of October, of ten tunnels, each measuring 100 feet long, 10 feet wide and 10 feet high, for the storage of 150,000 gallons of reserve petrol for the air force.

Until the New Zealanders left Fiji they continued these burrowing operations, which included the construction of a complete underground hospital with an air-conditioned operating theatre and wards opening off a central corridor; ammunition and food stores; and three giant petrol tanks in Sealark Hill, behind Suva Harbour,

where men worked night and day in shifts to complete them. These bulk tanks were the biggest single excavation undertaking by the engineers, whose activities were directed by Major W. G. McKay23 when McKillop returned to New Zealand in 1941. They ranged from 50 to 70 feet deep, one with a diameter of 58 feet and two of 48 feet. An operational headquarters was also excavated in the hill on which Borron's House stood. It contained chambers for the accommodation of all staffs and signal equipment, and was used frequently during trial manoeuvres. In the western area, which contained harder rock, the engineers could not penetrate so far underground, but their work was just as arduous as they built shelters for headquarters, air force, and hospitals. The duplication required by the two zones in Fiji weakened the force and increased administrative worries.

In the last months of 1941, visits of United States aircraft and ships of war indicated both the vital importance of Fiji and the trend of events, though it was impossible to convey to the men as they toiled and trained far from scenes of more obvious activity, any information concerning diplomatic talks and the mounting delicacy of the political situation with Japan. Such visits, pointers to coming events, were conducted without publicity. When the United States cruiser Chicago and five destroyers called at Suva on their return to Pearl Harbour after visiting New Zealand and Australia, few people were aware that they had made a secret test dash across the Pacific. Not until long afterwards was it revealed that a Tongan coastwatcher reported the ships. He was night-fishing far from the shore and was almost swamped by the wash as destroyers passed on either side of his frail canoe. Late in October two United States flying boats, carrying military and naval staff officers bound for the Philippines, called at Suva during a flight to investigate alternative air routes should hostilities cut the route to the Philippines via Wake and Midway Islands. An earlier air visitor was the old Empire flying boat ‘Calypso’, which, as A. 1811, was used by the Royal Australian Air Force to patrol from Port Moresby to Tulagi in the Solomons and Vila in the New Hebrides, and made one trip to Suva.

From these tours of investigation the importance of Fiji as a vital Pacific base was confirmed, and when, on 17 November 1941, certain sections of the American Neutrality Act were repealed by Congress a request was made to the New Zealand Government to

construct three airfields in the Namaka area, capable of accommodating the largest service aircraft. Because of the urgency of the request, New Zealand acted swiftly, and by the end of November 440 men of the Public Works Department reached Namaka to begin work on extending the existing field to take the Liberators soon to arrive. They were the first of 1219 Public Works men to reach Fiji for employment on this project.24 Following earlier discussions with General Puttick, all assistance, including rationing and quarters, was provided by Brigadier Cunningham's headquarters.

The successful completion of this project was one of New Zealand's most important achievements in the Pacific theatre of war. Three airfields, each with a runway measuring 7000 feet long by 500 feet wide, with revetments and servicing areas, were asked for, the first to be ready by 15 January 1942, the other two by 15 April. Their estimated cost was £750,000, repayable by the United States Government. They required one and a half millions yards of earth-works and 20,000 tons of cement, and the estimated time for completion was five months. The airfields were ready before that time. The first three Flying Fortresses landed at Nandi on 10 January; three Liberators followed on 23 January, and until the end of the war the Namaka area was a scene of intense air activity as fields were still further extended to cope with the demands of increasing traffic. Fiji had begun the vital role (which it still holds) as a staging centre for aircraft moving to and from New Zealand, New Caledonia, Samoa, Tonga, Australia, and America.

From the day the first New Zealand Public Works men arrived in November, construction went ahead without delay as bulldozers, carry-alls, tractors, and a fleet of trucks swiftly altered the landscape. For months the Namaka area lay under clouds of dust which mounted higher and higher in the hot air and tarnished all green vegetation for miles around. Although a blackout was imposed in Suva after the Japanese entry into the war, such precautions were impossible in the west, where huge arc-lights illuminated the landscape as work continued through the night. Trouble was anticipated and the provost officer, Captain A. L. Downes, prepared for it, but the civilians and servicemen worked amicably side by side, despite vastly differing rates of pay, conditions, and privileges which provoked much discussion at the time. Some difficulties concerning rates of pay and conditions did arise among the civilian workers from New Zealand, but they were smoothed out by the timely arrival by air of the Prime Minister and the Hon. P. C. Webb,

Minister of Labour. Peace reigned after three undesirables were returned to New Zealand. Not all these men desired to play a combatant role should the necessity arise, but 600 of them were armed with American rifles and Browning machine guns and trained for emergency operations. Authority for the construction of a flying boat base at Lauthala Bay, near Suva, had been given by 5 December 1941, and this work was also pressed forward with speed. The nucleus of an American Catalina squadron was operating there by March 1942.

III: From Pearl Harbour to Relief

There was not one anti-aircraft gun in the South West Pacific in November 1941 and the strength of the defences would not have deterred the most irresolute enemy. Pago Pago, the American naval base in Eastern Samoa, was as hamstrung by international agreement as were British bases. At the end of that month Cunningham's force, increased slightly during the year, totalled 4943 all ranks, made up of 8 Brigade Group and the Fiji Defence Force units, of which 945 were native troops. Artillery support consisted of six 18-pounder guns (some of which had been experimentally mounted on motor trucks in an effort to give them greater mobility) and fixed coastal defences of four 6-inch and two 4.7-inch naval guns. Air strength had been slowly increased under Group Captain G. N. Roberts, AFC,25 who relieved Baird in July, and consisted of six Vincents, two old Singapore flying boats of doubtful quality, three de Havilland multi-engine civil type machines, and one Moth trainer. The Fiji ship Viti, a small vessel which took the Governor round his scattered island domains, and five patrol launches constituted the naval strength based on Suva. In Tonga there were 462 native troops, commanded by nine New Zealand officers and warrant officers. These made up the defence force which had been organised by Lieutenant-Colonel R. Bagnall26 during his brief command. They were equipped with rifles and two Vickers machine guns and supported by two 18-pounder field guns. A detachment of 110 New Zealanders held Fanning Island, where one 6-inch naval gun had been emplaced to defend the vital cable station. In Samoa one New Zealand warrant officer had 150 native under his command. Rarotonga's force consisted of 100 natives and one

European officer, Captain Gladney, a local resident, with two Vickers machine guns as their only armament.

Small detachments of Australians acted as coastwatchers and guarded vital points on Nauru and Ocean Islands. Australia had also sent a small cavalry detachment, No. 3 Independent Company, to roam the unfrequented coastal regions of New Caledonia, where the collective armament had been increased from one old mountain gun to four 65-millimetre guns carried on lorries, two 37-millimetre guns, four 3-inch mortars, and 32 machine guns. Three hundred men of doubtful fighting quality, armed with rifles and two machine guns, had been mobilised in Tahiti, where three old 47-millimetre and two old 65-millimetre guns had been resurrected for action. New Zealand coastwatchers maintained a lonely vigil throughout the Gilbert and Ellice Islands, and in the Phoenix, Tokelau, Samoa, Line, Cook and Tongan Islands, and farther south, in the Kermadecs and Chathams. Petrol supplies for both aircraft and army motor transport totalled 118,300 gallons held in Fiji and another 20,000 gallons held in Tonga.

There was little or no difference in this state of affairs when Japan ended all speculation of her intentions when she struck at Pearl Harbour. Plans for manoeuvres on a brigade scale in Fiji had been outlined some time previously and worked out by Lieutenant-Colonel Wales, GSO 1,27 and troops moved into their defence positions in brilliant moonlight on the night of 7 December. As they prepared a soldierly breakfast of bully beef and smoky tea in their mosquito-infested trenches and splinter-proof machine-gun posts early the following morning, news of the attack was being broadcast to the world. Because of the international date line the attack on Pearl Harbour, which occurred at 7.50 a. m. on 7 December, Honolulu time, became 1.20 p. m. on 7 December in Washington, 3.20 a. m. on 8 December in Tokyo, and 6.20 a. m. in Suva and Wellington. One junior artillery officer who was fraternising with a short-wave enthusiast from Suva, was the first to receive the news. He lost no time in passing it on.

New Zealand's available forces at the outbreak of war with Japan consisted of HMNZS Leander, ready for sea at Auckland, HMNZS Monowai refitting at Auckland, and HMNZS Achilles, on her way to Singapore; 13,250 men were in camp, including reinforcements (600 of them intended for Fiji and others for 2 Division), the Army Tank Brigade, recruits and training cadres. Four

thousand six hundred fortress troops were mobilised—1000 each for Auckland, Wellington, Lyttelton, and Port Chalmers, and one company of 120 each for the Bay of Islands, Great Barrier Island, Waipapakauri, and Nelson, to protect aerodromes near the coast. Eleven thousand Territorials entered camp on 15 December and by the 28th 28,850 men were in camp, with preparations for an increase to 39,350 by 10 January. Forty-four converted machine guns, none too new, were issued to the Home Guard units. Navy reopened 24 coastwatching stations round New Zealand. The Air Department had 10,500 men in camp and in training, including 2155 despatched to air training centres in Canada, 2512 to the Royal Air Force, and 450 in Fiji. The only operational aircraft available were 36 Hudsons and 29 Vincents; all others, including 62 Harvards, 143 Oxfords, and 46 Hinds were used for training, though some of them could be used operationally in an emergency. In answer to immediate calls to the United Kingdom and United States Governments for urgent war materials to meet the needs of New Zealand forces both on the home front and in the Pacific, field guns were diverted from the Middle East, mortars from South Africa, rifles, ammunition, and signal equipment from America, Bren guns from Canada, and machine guns, tractors, rifles, and binoculars from the United Kingdom.

New Zealanders of 8 Brigade Group in Fiji were the only troops in the Pacific at their battle stations when war broke with Japan, and they remained there for three days, until the excitement wore off. There was little incident other than daily routine, but aircraft increased their dawn and dusk patrols with the machines still available.28 The first shot was fired by a sentry at a motor patrol boat which, ignorant of the startling turn of events, quietly chugged to its moorings in the dawn of the following day and did not answer the challenge; the second when HMS Gale, a small coastal steamer commissioned for service, arrived from New Zealand on Christmas Day and had a shot put across her bows by the shore battery when she failed to give the correct recognition signal as she approached the harbour entrance.

The movement of Japanese naval craft in waters north of Fiji was confirmed by the coastwatches in the Gilberts on 9 December, when they reported the presence of enemy ships and aircraft from carriers round their islands, and from that date, until they were either killed or taken prisoner, information of vital importance came from the men of those remote stations. December the 9th was a memorable day. A flight of five Hudson aircraft, the first reinforcements despatched from New Zealand, circled Suva before going on to Nandi and coincided with the arrival there of two long awaited 18-pounder guns, to complete the complement of field guns for 35 Battery, and four 4.5-inch howitzers. But the 10th brought the dreary news that two British battleships, HMS Repulse and HMS Prince of Wales, had been sunk off the coast of Malaya, sealing the fate of Singapore and leaving the whole Pacific Ocean open to the Japanese navy, until the stricken United States naval forces could be reorganised, after Pearl Harbour, to oppose the threat. In the midst of those grave days New Zealand supplied the Fiji Treasury with £30,000 worth of £5 notes and £50,000 worth of £1 notes, all overprinted, to meet a temporary shortage of currency caused by the demands of the garrison forces.

New Zealand's declaration of war with Japan at eleven o’clock on the morning of 8 December was quickly followed by preparations to expand the force in Fiji to two brigades and to strengthen all artillery, both field and anti-aircraft. War Cabinet approved the despatch of a further 3500 men and considerable quantities of supplies. For the remainder of December and January, two exceedingly hot and busy months, men and materials arrived in the Colony.

Units of Cunningham's force were brought up to strength by reinforcements speedily despatched in two voyages of the Wahine. On Boxing Day, 27 Mixed Anti-Aircraft Battery, under Major J. A. Pym, MC, reached Suva with four anti-aircraft guns which had been dismantled from the harbour defences of Auckland and Wellington. They were the first to reach Fiji. Three battalions—the 35th, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel W. Murphy, MC,29 the 36th, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel J. W. Barry,30 and the 37th under Lieutenant-Colonel A. H. L. Sugden31—formed at Burnham

Camp from the 8th Reinforcements for the Middle East, were organised and despatched to Cunningham's force; and in Fiji itself 2 Territorial Battalion was called up for full-time service. The new units made the voyage in a convoy of four ships—the Matua and the Rangatira, which went to Lautoka, and the Wahine and the Monowai to Suva, all under the escort of the cruisers Australia, Perth, and Achilles. The ships reached their destinations on 6 January and returned to New Zealand for the second flight, which arrived in Fiji on 14 January, the Port Montreal replacing the Matua on the second trip.

The new brigade commanders and their staffs flew to Fiji on 2 January, in the same aircraft which took Brigadier K. L. Stewart,32 Deputy Chief of the General Staff, for consulation and inspection. On 6 January Cunningham relinquished command of 8 Brigade Group and two days later was promoted Major-General commanding the Pacific Section, 2 NZEF, the official title of the force, which was not given divisional status until later. By the end of the month reorganisation was almost complete, and the new defence areas allotted to the expanded force. Command of 8 Brigade, which remained in the Suva area, passed to Brigadier L. G. Goss33 until the arrival of Brigadier R. A. Row34 late in February, after which Goss became New Zealand liaison officer on MacArthur's headquarters in Melbourne. Brigadier L. Potter35 took over the newly formed 14 Brigade for the defence of the western area, and established his headquarters at Namaka. In strengthening Fiji, New Zealand denuded herself of much of her available artillery. ‘We have sent the only four heavy anti-aircraft guns and the only four Bofors guns we possess’, Fraser cabled to Churchill, then in Washington, on Christmas Eve 1941. He did not say that the New Zealand guns had been replaced temporarily by dummies.

Reorganisation in Fiji brought about many changes in appointments and an extension of the two defended zones so that battalions took over areas formerly held by companies and platoons, but basically the plan of defence remained the same, though the mobility of the force was increased by the arrival of motor transport, so long anticipated. Cunningham's headquarters remained at Borron's House, where the accommodation was proportionately increased. Eighth Brigade took over a private residence, Hedstrom's House, at Tamavua, as its headquarters and gouged itself an underground operations room in the soapstone nearby. Fourteenth Brigade's operational headquarters was excavated in a feature known as Black Rock, which commanded a vast sweep of country overlooking Namaka, the airfields, and the beaches of the Nandi anchorage, and was made reasonably secure by the use of 50 tons of cement. Potter became the area commander, with the responsibility for defending 1000 square miles of country, extending from Momi to a line north of Lautoka and taking in such vulnerable localities as Thuvu, near Singatoka, where the coral reef merged with the foreshore. It was indicative of the vast stretches of territory which were included in the Fiji defence scheme.

By the end of January the force had been stepped up to 7600 all ranks, with units disposed through the areas they were to hold until their relief later in the year. In a hot and exhausting introduction to the tropics, the men dug, excavated, and erected belts of barbed wire through days and weeks of unremitting toil. Like the earlier arrivals they suffered all the discomforts of mosquitoes, dhobie's itch, prickly heat, septic sores, and tinea which were to harass them during the whole of the Pacific campaign.36

In the final reorganisation of the two brigades, in which unit commands were retained by some of the former officers, the 8th was made up of 1 Fiji Battalion (commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel J. B. K. Taylor, a New Zealander from the Fiji Civil Service), the 34th, the 36th, and two companies of 2 Fiji Battalion (under Lieutenant-Colonel F. G. Forster), two fixed coastal batteries, 35 Field Battery (increased to four 18-pounders, four 25-pounders, and four 4.5-inch and four 3.7-inch howitzers), 7 Field Ambulance (now commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel W. D. Stoney Johnston after the return to New Zealand of Davie), 20 Field Company Engineers (Captain S. E. Anderson), 4 Composite Company, ASC, and 36 Light Aid Detachment.

Potter's brigade group was made up of 30 Battalion (commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel J. H. Irving, who took over when Mawson returned to New Zealand), 35 Battalion (command of which passed to Lieutenant-Colonel G. H. Tomline, MC, when Murphy went almost immediately to headquarters as GSO 1), 37 Battalion, the remaining companies of 2 Fiji Battalion, one fixed coastal battery at Momi, 37 Field Battery (commanded by Major W. A. Bryden and made up of four 18-pounders and four 4.5-inch and four 3.7-inch howitzers), 27 Mixed Anti-Aircraft Battery, 23 Field Company Engineers, 16 Composite Company, ASC (Captain R. Gapes), 2 Field Ambulance (Major E. N. d’Arcy), Namaka Hospital (Major P. C. E. Brunette), and section of ordnance workshops. As divisional reserve, 29 Battalion was stationed at Nausori, beyond the Suva perimeter, to deny the use of the Rewa River bridge and to defined the Nandali aerodrome, where P-39s (Airacobras) of an American pursuit squadron of 60 officers and 600 men under Colonel Edgar T. Seltzer maintained some of their machines, the remainder being at Namaka. They were the first Americans to reach Fiji, where they arrived at the end of January 1942.

Artillery during the whole of the Pacific campaign was always an involved problem since the force had under its command fixed coastal batteries of naval guns and also defended base aerodromes, tasks not normally required of a division in the field, but island warfare demanded revolutionary changes in prescribed war establishments. The artillery organisation of the forces in Fiji, later repeated in New Caledonia, was perhaps the most involved of all the New Zealand island undertakings. The fixed coastal batteries of the Fiji artillery, sited in each zone to defend the ports, anchorages, and the more vital openings through the reefs leading to them, came under area commanders for operations but were administered from headquarters. At the time the force artillery was relieved by

the Americans, it consisted of these fixed coastal batteries, heavy and light anti-aircraft batteries (both fixed and mobile), and field batteries. Circumstances also altered the functions of the infantry and other services. For example, in Fiji the ASC issued rations on seven different ration scales at one time and supplied not only the New Zealand force but also Americans, New Zealand civilians working on the airfields, Fijian soldiers and labourers, and Indians employed on camp staffs.

Alarms came frequently during the earlier months of 1942 as signals from Wellington and Washington warned of a possible attack. Reports from the coastwatchers in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands recorded any activity in those waters, and there were moments of excitement in Suva, as on the afternoon of 16 January when HMS Monowai, outward bound for New Zealand, reported an attack by enemy submarine soon after she passed beyond the protection of the reef. Shots were exchanged as the vessel zigzagged, and she reported that a conning tower broke the surface of the water. Although aircraft searched the area until darkness fell, no trace of the submarine was disclosed and no confirmation of the attack could be obtained from Japanese sources, though it must be added that several enemy submarines operating in the South Pacific at that time never returned to their base.

A fleet of these underwater craft kept headquarters at Truk, in the Caroline Islands, moderately well informed of Allied activities in the Pacific, and native coastwatchers were often correct with their quaintly expressed reports that they had seen strange aircraft and ships. Much of the information attributed to fifth columnists really came from Japanese submarines, which cruised about the Pacific and surfaced off the islands to launch their aircraft which made reconnaissance flights, usually just before dawn. On 19 March 1942 native coastwatchers on Kandavu, an island on the outer rim of the Fiji Group, reported that a large bird had settled on the water and entered a ship, which immediately sank. It was an aircraft from submarine I-25, which had also reconnoitred Auckland and Wellington some days previously. On 21 May an aircraft from submarine I-21, which patrolled the Pacific until it was sunk in the Marshalls in 1944, was chased into the clouds by American aircraft stationed at Nandi.

Until the arrival of radio direction-finding apparatus late in the days of the force, detection of these elusive craft was difficult. From February 1942 until September 1943, 23 Japanese submarines, of which 14 carried aircraft, operated round the Australian and New Zealand coasts as well as in waters round New Caledonia,

Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, and the New Hebrides. Even after enemy reverses in the Solomons they continued to patrol south, but in decreasing numbers. These submarines reported the arrival of the first big convey of American troops in Fiji on 10 June 1942, and they sighted the convoy 200 miles south of Suva carrying the first reinforcements to strengthen Cunningham's force earlier in the year.

All such information was passed by radio to Japanese naval headquarters in the Caroline Islands and transmitted to Tokyo. Moving to and from Truk to refuel and revictual, Japanese submarines made the following voyages: From February to March 1942 submarine I-25 reconnoitred the Auckland and Wellington Harbours, the east coast of Australia, Suva, and Pago Pago; in April I-25, I-27, and I-29 investigated Suva, Sydney, Auckland, and Nouméa; in June and July I-22, with I-27 and I-29, again reconnoitred the New Zealand and Australian coasts, sinking one ship; throughout July and August I-11, I-175, I-174, I-169, and I-171 sailed round New Caledonia, Fiji, Samoa, and the east coast of Australia, sinking five ships; in October I-15, I-17, I-19, and I-26 patrolled the New Caledonian coast; I-21 returned there in November and stayed until early December; in November I-31 and I-7 reconnoitred Suva, Pago Pago, and Espiritu Santo, in the New Hebrides. From July to the end of September 1943 five of these submarines returned and investigated waters round Fiji, New Caledonia, and the New Hebrides. I-17 was sunk in August 1943.

If men and materials were haphazard in reaching Fiji before Japan entered the war, they came in quantity afterwards, even if quality was lacking. Some of the motor transport impressed in New Zealand was despatched without reasonable inspection of either its cleanliness or its serviceability and was condemned on arrival. As evidence of the haste, animal droppings still covered the floors of many of the vehicles. By the end of January the first American supplies arrived, including 3900 rifles, 24 two-inch mortars, 98 Thompson sub-machine guns, and 118.30 machine guns, as well as field telephone cable, telephones, switchboards, 23 wireless sets, and 200 mines to block the openings through the reef. Two thousand of the rifles and the .30 machine guns were sent on to New Zealand. Blackouts, previously imposed but lifted at the request of the Governor when the citizens complained of the stifling discomfort, were again enforced. Tactical exercises by the brigades tested their own mobility and the state of the defences. One such exercise by 8 Brigade assumed all the elements of reality by coinciding with the arrival of an American convoy at Suva. The

exercise began just before midnight of 8 March, when units occupied battle stations on receipt of information that an enemy convoy was approaching Fiji. Early next morning reports were circulated to units that the Nandi airfields were being bombed. This news, carried with the speed of gossip to the civilian population, produced a mild panic when aircraft of the force made low-level runs over camps, roads, and assembly points. Indians hastily loaded their belongings on trucks, cars, handcarts, and even bicycles and fled to the hills, blocking road traffic and indicating conditions which would attend a genuine attack. After that experience all orders concerning exercises were prefaced with the word ‘Practice’.

By the end of June there were 10,000 New Zealanders in Fiji. This in itself created an acute accommodation problem, happily overcome by building native style huts called bures, which had the added advantage of assisting the general scheme of camouflaging all camps and defences, because these bures were sited to resemble small native villages. Troops helped with this camouflage by making nets from vau bark to cover gunpits and supply depots, and by planting such creepers as ‘mile a minute’ which quickly covered any newly broken ground. This plant spread with astonishing speed. One excused duty soldier who had times to watch it verified that it grew at the rate of 14 inches a day.