Chapter 9: Navy and Air Force

I: The Navy in the Solomons

IN addition to convoy duty in the Pacific, which was undertaken by ships of the Royal New Zealand Naval Squadron from the outbreak of hostilities, two New Zealand cruisers were damaged in action while fighting under American command in the battle for the Solomons. Corvettes of the squadrons also took part and lent valuable assistance, particularly during the struggle for Guadalcanal, where they were engaged on submarine patrol work.

Following one of several bombardments of the Munda airfield, in New Georgia, by surface craft, HMNZS Achilles, commanded by Captain C. A. L. Mansergh, DSC, RN,1 was damaged and forced to retire from service with Halsey's naval forces. On the night of 4–5 January 1943, a task force of four cruisers and three destroyers commanded by Rear-Admiral Mahlon S. Tisdale, in the cruiser Honolulu, patrolled off Guadalcanal while another task force bombarded Munda in the first co-ordinated night action of surface craft, aircraft, and submarines. Next morning, as both forces joined and steamed off Cape Hunter, Guadalcanal, they were surprised by four Japanese Aichi dive-bombers which came from the direction of Henderson Field and were mistaken for friendly aircraft.2 The enemy planes dived on the line of cruisers before

Captain Mansergh's report on the engagement, dated 17 Jan 1943, reads in part:

‘The armament was manned by the AA Defence Watch, the highest degree of antiaircraft readiness short of action stations, namely, all 4-inch guns and control manned, seven Oerlikons manned, “B” and “X” turrets skeleton-manned for barrage fire and all lookouts posted.

‘At 0925 a formation of four American Grumman fighters was sighted at about 12,000 feet immediately above the ship. These aircraft were positively and correctly identified as American machines. Two minutes later a further group of four aircraft were sighted spiralling down through the clouds at an angle of sight of about 40 degrees ahead of the ship and the aircraft alarm was sounded.

‘The aircraft followed one another in quick succession, the first three attacking Honolulu without success and the fourth attacking Achilles. The ship was swinging slightly to starboard when a bomb hit the top of “X” turret, piercing the roof and exploding on top of the right gun....’

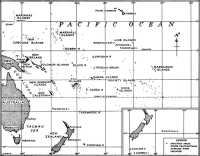

The Pacific Ocean

the Allied ships began firing, and a bomb from the third Japanese plane scored a direct hit on the roof of No. 3 gun turret of Achilles. It penetrated the one-inch steel plates and exploded on the cradle of the right gun, wrecking the gun house and killing six of the crew. Seven others were wounded. The right side of the turret was blown into the sea. The force of the explosion split the roof, one half of which was thrown on to the quarter deck; the other half turned upside down in the air and came down again on the turret. Fires were quickly extinguished. An American naval report recorded that Achilles, hero of the Battle of the River Plate, ‘took the damage in her stride and never lost position. Her A/A fire continued throughout the brief engagement.’

A few months later, during the progress of the battle for Munda airfield, strong naval forces periodically swept the waters of Kula Gulf, between New Georgia Island and Kolombangara, for the dual purpose of bombarding Japanese installations and concentrations ashore and holding off determined attempts to reinforce garrisons established near Rice Anchorage and at Bairoko Harbour and Enogai Inlet. By this time the line of the Tokyo Express had been reduced in length but it was still running under cover of darkness. These expeditions to contain enemy activity developed a further series of naval engagements, in one of which, the Battle of Kolombangara, HMNZS Leander was gravely damaged. She was commanded by Mansergh and for some months had been on convoy duty to Fiji, the New Hebrides, and Guadalcanal. On 11 July the Leander joined Rear-Admiral W. L. Ainsworth's task force to replace the cruiser Helena, which had been torpedoed in the Battle of Kula Gulf a week previously after surviving twelve major naval engagements in the Solomons. That night Ainsworth's force protected a convoy landing munitions and supplies for units fighting in the jungle, and after returning to Tulagi to replenish fuel and munitions was again ordered north to disrupt any enemy forces bringing reinforcements to New Georgia. Ainsworth moved out of Tulagi on the evening of 12 July, and on the journey north hugged the coast of Santa Isabel because of bright moonlight. Because the Leander's radar was inferior to that of the American cruisers, she was placed between Ainsworth's flagship, the Honolulu, and the St. Louis. Soon after one o'clock on the morning of 13 July, a Japanese force led by the light cruiser Jintsu was encountered off Kolombangara, and about twenty minutes after the action began the Leander was struck by a torpedo, after firing four herself, just as she was straightening up after completing a turn. Defects in the TBS system caused the

Leander and several of the United States destroyers to miss an executive signal, and the situation was further complicated by dense smoke from flashless powder.

The Leander came round promptly after seeing the movement of the flagship through a rent in the smoke clouds, but there was considerable bunching at the turn and drastic avoiding action had to be taken to prevent collisions as the cruisers and destroyers came into line again. The Leander was hit by a torpedo while executing this movement. The explosion tore a hole in her port side and flooded No. 1 boiler room; No. 2 boiler room had to be abandoned; the ship's electrical installations failed and five fuel tanks were wrecked. Seven men were killed. One gun crew and the upper deck fire party, numbering 21 all ranks, were swept overboard and the ship travelled some distance before this was noticed. Fifteen men were injured but the ship's crew, many of them in action for the first time, behaved like veterans throughout the engagement and afterwards. Two American destroyers, the Radford and the Jenkins, were detached by Ainsworth to escort the Leander 200 miles back to Tulagi, where she remained for a week before returning to Auckland. The American force lost heavily in this action, which continued after the Leander was struck. Both cruisers, Honolulu and St. Louis, were damaged by enemy torpedoes, the destroyer Gwin was lost, and two other destroyers damaged in a collision. The Jintsu was sunk.

New Zealand's little ships, the 600-ton corvettes, added a well-documented page to the country's naval tradition while they worked as part of the American naval command. Six of them spent lengthy periods in the forward zone and were actively engaged round Guadalcanal, working from a base at Tulagi before and after the Japanese evacuation, and afterwards as far north as Green Islands, moving forward as naval bases were established on recaptured islands. Except for periods of refit in New Zealand, these corvettes remained in the Solomons until the end of the campaign. They constituted the 25 Minesweeping Flotilla, South Pacific Command—HMNZS Moa, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander P. Phipps, RNZNVR; HMNZS Kiwi, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander G. Bridson, RNZNVR; HMNZS Tui, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander J. G. Hilliard, RNZNVR; HMNZS Matai, commanded by Commander A. D. Holden, RNZNR, senior officer of the flotilla; HMNZS Gale, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander C. MacLeod, RNZNR; and HMNZS Breeze, commanded by Lieutenant-Commander A. O. Horler, RNZNR. These last two were small coastal ships taken over by the Government early in the war. Holden was

relieved by Phipps on 21 August 1944, and in December of that year HMNZS Arabis arrived in the Solomons to relieve Matai, and he transferred to her. From June 1945 until the end of the war two months later HMNZS Arbutus, commanded by Lieutenant N. D. Blair, RNZNVR, served with the British Pacific Fleet as an escort and radio and radar servicing vessel with the fleet train.

The corvettes' first ‘kill’ was one of Japan's submarine fleet operating with land forces at the time the evacuation of Guadalcanal began, the I-1, of 1970 tons. She was destroyed in a combined action by Kiwi and Moa on the night of 29 January 1943. In heavy rain squalls which limited visibility, they were on patrol off the northern tip of Guadalcanal opposite Kamimbo Bay when the Kiwi's Asdic officer, Sub-Lieutenant D. H. Graham,3 reported a contact 3000 yards away, the maximum range. It was then five minutes past nine. Further contacts confirmed the presence of the enemy submarine, and the Kiwi went into the attack, dropping six depth charges as she closed the distance between them, until the submarine could be seen outlined in the phosphorescence which is such a feature of tropical waters at night. A second release of depth charges forced the submarine to surface about 2000 yards away, and the Kiwi, being the nearer vessel, raced towards her with machine and 20-millimetre guns blazing and her searchlight, operated by Leading Signalman Howard Buchanan,4 playing on the enemy vessel. The Moa supported her sister ship, firing star shells to illuminate the murky tropic night. Both corvettes were outclassed by the submarine's heavier armament which by now had come into action. The Kiwi decided to ram her from about 150 yards. She struck the submarine on the port side to the rear of the conning tower, but was unable to cut through the ship's heavy plating. The Kiwi's guns put the submarine's 5.5-inch gun out of action, but her machine and six-pounder guns were still operating. Although he was mortally wounded and died later in the night, Buchanan continued to operate the Kiwi's searchlight, holding the enemy ship in its beam. Bridson5 decided to ram again, but as the submarine had begun to move towards the shore the two ships met at a glancing angle. Bridson quickly manoeuvred and rammed a third time, this time with success, for the Kiwi slid up on the submarine's deck, spilling the Japanese crew into the water. As she retracted from this dangerous position, oil spouted from the submarine's tanks.

The Kiwi's guns, which had been in action almost continuously for an hour, were now too hot to continue the fight. The Moa took over and scored more hits on the submarine, which struck a reef and sank before she could reach the shore. The Hon. Walter Nash later took I-1's flag back to New Zealand.

The Moa remained on patrol for the remainder of that night, and then, in company with the Tui, fought an engagement the following night off Cape Esperance, from which the Japanese had begun evacuating their troops. The two corvettes engaged four Japanese landing barges and sank two of them. Cordite on the Moa caught fire when she was struck by an enemy shell, but the flames were extinguished before any great damage was done.

As soon as the Japanese evacuation of Guadalcanal was confirmed, preparations were made by 14 Corps headquarters to move into the Russell Islands, a group farther north and most suitable for navy and air staging bases. To the Moa fell the task of carrying the first reconnaissance party there, and on the night of 17 February selected officers of 43 US Division and others from Navy and Marine units moved from Guadalcanal to Renard Sound, in the south of the group, where they were put ashore in darkness, only to be told by the natives that the Japanese had gone.

The Moa was lost at Tulagi two months later during one of the last concentrated Japanese air attacks on shipping lying in the channel between Florida and Guadalcanal and in Tulagi Harbour. Thirty-three of 117 enemy aircraft were shot down on 7 April 1943, but not before they had wrecked the New Zealand corvette, sunk an American destroyer and an LST, and damaged three cargo vessels. One 500-pound bomb struck the Moa near the bridge, passed through Phipps's cabin, and exploded below. Five ratings were killed, seven seriously injured, and Phipps6 and seven other ratings injured.

The following August the corvette Tui was primarily responsible for the destruction of Japanese submarine I-17, a craft of 2563 tons, which had shelled the Californian coast in February 1942. Early on the afternoon of 19 August the Tui left Nouméa, New Caledonia, to escort two American supply ships to Espiritu Santo. Sixty miles south-east of Nouméa, her Asdic operator recorded a contact and she made three runs over the area, dropping depth charges before proceeding on her way, but without confirming the presence of the enemy. Later that afternoon aircraft on patrol over the approaches to Nouméa Harbour asked the Tui to

investigate smoke on the horizon, and at 7.15 o'clock that evening she sighted the conning tower of the submarine which had been forced to the surface by the depth charges. The corvette opened fire at extreme range as the submarine tried to escape in the evening light, but she was ultimately sunk by aircraft. Six survivors of a crew of 97 were rescued by the Tui. I-17, which had spent from April to June in waters round Fiji, Tonga and Samoa, carried one reconnaissance aircraft and had a cruising range of 14,000 miles.

Until the Solomons campaign ended, New Zealand corvettes undertook tours of duty at anchorages of the various islands where ground forces were operating. When elements of 3 Division occupied the Treasury Group, they did patrol duty in Blanche Harbour and again at Green Islands, protecting the cargo ships which lay off the entrance to the lagoon. When the American forces landed in Empress Augusta Bay to establish a perimeter, the Breeze on the night of 1–2 November laid mines off Cape Moltke to protect surface craft unloading in the bay off Torokina.

‘The alert and courageous actions of the crews of these gallant little ships merits the highest praise’, Halsey observed in a report on their activities.

II: The Air Force Story

New Zealand's air strength in the Pacific grew from a small force despatched to Fiji in November 1940 under Squadron Leader D. W. Baird, which ultimately became known as No. 4 Bomber Squadron, and at the outbreak of war with Japan consisted of four outmoded de Havilland machines and six Vincents. Two aircraft of an army co-operation squadron were also stationed in Fiji. On 8 December 1941 this small unit was reinforced by six Vincents sent from New Zealand. From the time the United States assumed responsibility for the defence of the South Pacific area in 1942, New Zealand air units stationed there came under operational command of the Americans.

In planning air support and preliminary cover for the landing on Guadalcanal, Rear-Admiral John S. McCain, commander of air forces, South Pacific Command, requested the New Zealand Government to send six Vincent aircraft from the Fiji command to New Caledonia to assist with anti-submarine patrols over the sea approaches to the Solomons. Squadron Leader G. N. Roberts, who succeeded Baird, was then commanding New Zealand air force units in Fiji, where he had remained under American command after the return of 3 Division in 1942. New Zealand, however, considered that Hudsons would be more suitable for patrol work.

Two were flown from Fiji in July and the remainder from Nos. 1 and 2 Squadrons in New Zealand. From these aircraft grew No. 9 Bomber Squadron, commanded by Squadron Leader D. E. Grigg,7 which began operations from the Plaine des Gaiacs airfield, a dreary, dusty site on the west coast of New Caledonia near the primitive port of Nepoui. Dawn and dusk patrols to a distance of 400 miles began on 21 July 1942 and were continued until March 1943, under miserable and exasperating conditions. The squadron, ill equipped for both climate and maintenance, from the beginning of its tour of duty depended on American sources for medical services, signals, transport, rations, fuel and oil. No mosquito nets had been supplied with the unit's equipment, and the airmen suffered unmercifully from the clouds of mosquitoes which infest that corner of New Caledonia. Even when some prefabricated huts arrived later from New Zealand, they were unsuitable for the conditions. Time and infinite patience solved most problems as the unit became self-supporting.

While the squadron maintained its routine and often monotonous flights for eight months, No. 3 Bomber Squadron, under Wing Commander G. H. Fisher,8 moved from New Zealand to the island of Espiritu Santo, in the north of the New Hebrides, on 14 and 15 October, when the battle for Guadalcanal was reaching its climax. This move was the result of representations made by the Chief of the Air Staff (Air Vice-Marshal R. V. Goddard)9 while in Washington, for an operational role for the Royal New Zealand Air Force in the Pacific, and the answer to a request from the American Command for a second bomber squadron to relieve No. 9, so that it could move forward to the combat zone. Almost immediately, however, a change of plan by the Air Command requested No. 3 Squadron's services at Vila, on the island of Efate, and then at Espiritu Santo. The full resources of American construction might and industry had been turned on to this island, more commonly known as Santo, and airfields had been carved out of jungle and hill to make it both a reserve area and operational base and ultimately one of the great forward naval and air bases of the Pacific. Aircraft and crews of No. 3 Squadron staged to Espiritu Santo through Norfolk Island and New Caledonia from Whenuapai, and began operations from Pallikulo airfield on 16

October, patrolling the sea lanes for enemy submarines. Lack of liaison in the early planning for this hasty move prevented any preliminary survey of the area to be occupied, and on arrival tents were pitched wherever space could be found for them among the trees and undergrowth. Espiritu Santo is one of the wettest, hottest, and most mosquito-ridden islands of the group, and conditions for the squadron were most unhappy until more permanent quarters were constructed. Late in November, however, the first units of this squadron moved forward to Guadalcanal and joined American units operating in congested conditions from Henderson Field. On 23 November, at a most critical time in the campaign, the New Zealand Hudsons undertook long-distance patrols for which they were more suited than the torpedo- and dive-bombers the Americans had been using. Flying Officer G. E. Gudsell10 was the first member of the unit to meet the enemy. He was on patrol over Vella Lavella when three enemy aircraft guarding a convoy attacked him. A few days later Gudsell fought off three Japanese machines in a seventeen-minute engagement and proved the superiority of his Hudson in air combat. Sergeant I. M. Page11 bombed a submarine while on patrol to the west of New Georgia on 2 December.

By 6 December the whole squadron, command of which passed later to Squadron Leader J. J. Busch,12 was concentrated on Guadalcanal as part of the American Task Force 63, leaving a rear echelon on Santo to provide replacements and servicing. Until 14 December, when a change of routine was made, individuals of the squadron flew four, five, and six patrols a day over the Japanese-held islands of New Georgia, Santa Isabel, Choiseul, and Vella Lavella, as far north as Bougainville and intervening waters, but this was reorganised into regular two morning and four afternoon searches. In addition to seeking for enemy surface craft, submarines, convoys, and troop concentrations, most valuable information in a daily assessment of the enemy's strength, patrolling aircraft reported on the weather in a climate where conditions changed swiftly and drastically hampered surface and air operations. The New Zealand patrols frequently reported on the activities of the Tokyo Express as it moved in daylight down ‘the Slot’, prior information which enabled operational command on Guadalcanal to be prepared for the enemy's approach

either by sea or air. One of the first attacks on the newly discovered Munda airfield in New Georgia, which was cunningly constructed underneath the heads of palms, supported on wires, was made by a Hudson on the morning of 9 December, and from that day the field was regularly attacked from the air and from the sea. Hudsons of No. 3 Squadron assisted with air cover for the task force which bombarded the airfield on the night of 4–5 January 1943, when the Achilles was put out of action. It was a pilot of No. 3 Squadron who reported the last run of the Tokyo Express to Guadalcanal on 7 February, while he was on patrol near Vella Lavella. Through rents in rain squalls he observed 19 Japanese destroyers moving south at high speed near Ganongga Island, and reported their presence and direction to headquarters on Guadalcanal. Interception failed to prevent them from uplifting the Japanese garrison from the beaches of Cape Esperance that night.

New Zealand air strength on Guadalcanal was increased in April when No. 15 Fighter Squadron arrived from Tonga, where it had been stationed for three and a half months, staging through Espiritu Santo to be equipped with more modern Kittyhawks (P40Ks). The new arrivals were soon in action. On 6 May Squadron Leader M. J. Herrick, the commander, and Flight Lieutenant S. R. Duncan13 shot down a Japanese float-plane north of Guadalcanal. Two days later Herrick led eight New Zealand fighters in a combined attack, with American bombers, on three Japanese destroyers which had been damaged by magnetic mines in Blackett Strait, between Kolombangara and New Georgia. Two destroyers, the Oyashio and the Kagero, were strafed by the New Zealanders and sunk by the bombers; the third destroyer, Kuroshiro, was sunk by mines.

The New Zealand airmen made reconnaissance flights in all weathers, and weather in the Solomons, which may change from a cloudless sky to violent electrical storms in a remarkably short time, can be as dangerous as any enemy. In March 249 bomber-reconnaissance flights were recorded by the New Zealanders and 197 searches and other missions in April. Submarines or suspected submarines were not often sighted, although targets were more plentiful during the first two weeks of April. Flight Sergeant C. S. Marceau14 reported one such successful mission on 3 April when, under cover of a rain squall, he dropped three bombs on a target off Vella Lavella.

By the time Halsey was ready to strike for the Munda airfield and force the Japanese out of New Georgia, he was still far from strong enough for the enormous task demanded of his available air strength. He had at his disposal 290 fighters, 170 dive- and torpedo-bombers, 35 medium bombers, 72 heavy bombers, 18 flying boats, and 42 other types of aircraft. With these he carried out reconnaissance missions over the whole of the Solomons as far north as Buka and New Ireland, supported land forces in action in the jungle, fought off enemy air attacks on shipping and his own bases, neutralised enemy shipping and destroyed as much of it as he could. Because of the shortage of aircraft, all units worked at high pressure in heat and humidity which soon drained the strength and affected the nerves of the aircrews. Servicing units worked round the clock to keep the aircraft available for combat.

Throughout the months of 1943 the Japanese attempted with their dwindling air strength to hinder concentration of Allied air and naval forces on Guadalcanal. On 7 June between 40 and 50 enemy fighters were broken up before they had time to attack new airfields established on the Russell Islands, into which the Americans had moved after the Japanese retreat from Guadalcanal. These were then the most advanced airfields in the Solomons and were hurriedly constructed to assist in the New Georgia operation. Twelve machines of No. 15 Squadron took part and shot down four Japanese, two of the squadron's planes crash-landing in the Russells. Another determined attempt followed on 12 June, when 25 Japanese aircraft were shot down. Eight aircraft of No. 14 Squadron, commanded by Squadron Leader S. G. Quill, were in the process of relieving No. 15 when the attack came. They joined in, shot down six Japanese aircraft, and lost one of their own. One of the most determined raids on airfields and shipping came on 16 June, when more than 100 Japanese bombers and fighters were driven off with great loss. Coastwatchers reported the flights moving south and Allied aircraft were prepared for them when they reached within striking distance. Pilots of No. 14 Squadron dived into a formation of 33 Japanese aircraft, four New Zealand pilots accounting for five Japanese. Seventy-seven enemy machines were claimed as destroyed by Allied planes in that attack and eleven more were brought down by anti-aircraft fire. The Allies lost six fighters, one cargo ship, and one LST.

During the battle for Munda air formations from Guadalcanal and the new fields on the Russells protected convoys, covered landings, and neutralised Japanese airfields as far north as Vila, Ballale, and Kahili. By this time the air superiority of the Allies

was acknowledged. Construction work had forged ahead during April and May, and by June four fields were operating on Guadalcanal, with two subsidiary strips in the Russell Islands. When the American units landed at Rendova, in the initial thrust into the New Georgia Group, No. 14 Squadron aircraft provided air cover, working for the operation from the Russell Islands, where refuelling and rearming were maddeningly slow from the still inadequately organised fields, and food supplies were neither sufficient nor palatable. But the pilots never relaxed their efforts, despite the debilitating heat and the seas of mud which busy feet and vehicles enlarged each day round the airstrips and installations. July 1943 was a month of intense air activity as the Americans maintained the superiority they had at last achieved and intended to retain. The month opened successfully on the 1st when Flight Lieutenant E. H. Brown15 led a flight of eight New Zealand aircraft and combined with Americans in holding off an attack by 22 Japanese machines on the Rendova beach-head, where the Americans went ashore, shooting down seven enemy planes. Brown baled out of his damaged machine on the way back to base and spent four and a half hours in the water before he was rescued. Two days later, while again on patrol over Rendova beach-head, eight more machines of No. 14 Squadron were surprised by forty of the enemy, who swept on them out of a cloud. Quill, who was wounded, and Sergeant R. C. Nairn,16 each accounted for a Japanese machine. Flying Officer G. B. Fisken17 claimed three. During the month, in addition to arduous patrols, No. 14 Squadron pilots escorted flights of American bombers during attacks on enemy ships and air and naval bases as far north as the Shortland Islands and Bougainville.

Halsey's air strength was sufficient by the middle of July 1943 to justify increased strikes against enemy bases, and on 17 July No. 14 Squadron combined with the Americans in the largest air operation undertaken up to that time in the Solomons. A concentration of 71 dive- and torpedo-bombers and seven heavy bombers, escorted by 114 fighters, sought out enemy shipping at Kahili, sank and damaged seven ships and dispersed others. The following day a similar mission, in which New Zealand fighter pilots were employed in close escort for the American bombers, attacked enemy shipping in the Shortland Islands and the south of Bougainville anchorages.

Because of the prevailing conditions in the Solomons, New Zealand fighter squadrons were relieved after a six weeks' tour of duty in the forward area. Squadrons usually spent six weeks in Espiritu Santo before they were sent forward. From the combat zone they returned to New Zealand for rest and reorganisation. No. 14 Squadron,18 which had accounted for 22 Japanese aircraft, was relieved by No. 16, commanded by Squadron Leader J. S. Nelson,19 on 25 July and moved back to base at Espiritu Santo, remaining there until relieved by No. 17 Squadron under Squadron Leader P. G. H. Newton,20 after which No. 14 moved back to New Zealand. The periodical rotation of active squadrons made for greater efficiency and reduced sickness. No. 16 Squadron remained on Guadalcanal for two months, undertaking much of the same kind of work as No. 14 had done and earning similar praise from American commands and from the crews of the bombers they protected. Encounters with enemy aircraft, however, were becoming less frequent as pressure on the ground was maintained and captured islands were consolidated, but the New Zealanders continued to provide cover for American bombing missions and themselves searched out and destroyed Japanese shipping, particularly barge traffic round the islands. On 25 August Flight Lieutenant R. L. Spurdle21 and Flight Sergeant N. A. Pirie22 set fire to some Japanese barges on the coast of Choiseul, then shot up three more boats used by the Japanese in evacuating their scattered forces from the New Georgia Group. Flight Lieutenant J. R. Day23 led a flight which set fire to two vessels off Ganongga Island, just south of Vella Lavella, the following day. While returning to their base after covering an American bombing mission on 3 September, two of the squadron's pilots, Flight Lieutenant M. T. Vanderpump24 and Flight Sergeant J. E. Miller,25 fell back to protect a damaged American bomber which was being attacked by eight enemy Zeros. They drove off the Japanese and escorted the damaged bomber to a safe landing. Both pilots were awarded immediate American

decorations. During its tour of duty, which ended in September, the squadron's aircraft flew a record of 2100 flying hours.

On 11 and 15 September No. 17 Squadron moved up from the New Hebrides and took over, and with its arrival New Zealand air strength in the forward zone was increased to two squadrons, with a third in reserve on Espiritu Santo. No. 15 Squadron returned for its second tour of duty on 14 September, and No. 18 Squadron took over fighter defence duties in the New Hebrides on 17 September. Their arrival coincided with the landing of 3 New Zealand Division on Vella Lavella, for which aircraft from both 15 and 17 Squadrons helped to cover disembarkation and subsequent ship-to-shore operations. These aircraft were based on Guadalcanal, but operated from Segi airfield (which had been constructed by the Americans at Segi Plantation, in New Georgia, to assist with the final attack on Munda) and Munda itself, long since in American hands and now headquarters of the American 14 Corps under Griswold. On 1 October pilots of No. 15 Squadron claimed seven Japanese dive-bombers from a concentration which attacked a 3 Division convoy off Vella Lavella.

During this time important changes had been made in the organisation and administration of the Royal New Zealand Air Force units in the South Pacific zone. Early in 1943, as the drive through the Solomons gained momentum, the Dominion's increasing air strength provoked such problems of administration as to warrant the establishment of a group headquarters. From their earliest participation in the Pacific war, units were scattered over several widely separated islands, each operating under different commands. Moreover, operational command was exercised by the commander in whose area the unit happened to be stationed, but administrative control was still exercised from Air Department in Wellington. To achieve some unity of control in the forward zone, No. 1 (Islands) Group was established at Espiritu Santo on 10 March, under command of Group Captain S. Wallingford,26 who had been RNZAF staff officer on McCain's headquarters in the USS Curtiss, then anchored in Segond Channel, near the principal American air bases. At this time administration of the several units was confused. On Espiritu Santo were the advanced echelons of Nos. 9, 14, and 15 Squadrons, all separated from their ground and headquarters organisations, which were hundreds of miles away on other islands. The rear details of No. 3 Squadron, which administered

No. 4 Repair Depot, were also on Espiritu Santo. Some further unity of command was desirable as the year progressed, for New Zealand's air strength was still further increased in the forward zone and greater expansion was planned for 1944. The changing strategical situation towards the end of 1943 also made it desirable to move administrative headquarters farther forward. Ancillary and maintenance organisations had grown proportionately and increased problems of administration, which had not been helped by the haphazard method of unloading supplies at Santo, where representatives of each service sought its own from the immense quantities dumped ashore from ships eager to make a quick turn-round. At times goods destined for Espiritu Santo sometimes lay at Nouméa for weeks. This was due principally to the existing multiplicity of commands, and also to the fact that as soon as ships reached the South Pacific area their destination could be altered by Halsey's headquarters, according to the demand for shipping in any certain given area.

Since many of the functions of a base organisation were already being undertaken by No. 1 Group Headquarters, it was decided late in 1943 to establish a base depot on Espiritu Santo and move Group Headquarters to Guadalcanal, which would take it 600 miles farther forward. At the end of October Wing Commander I. E. Rawnsley, MBE,27 who had been commanding the New Zealand station on Espiritu Santo, was appointed to command the station on Guadalcanal. A base depot, with a strength of 1196 all ranks, was established at Santo on 1 November and Wing Commander H. L. Tancred, AFC,28 appointed to command it. By the end of the month Air Commodore M. W. Buckley, MBE,29 succeeded Wallingford, who in the meantime had been promoted to similar rank. At its formation the base depot administered the following units: No. 14 Squadron, No. 3 Squadron (back from Guadalcanal), No. 6 Flying Boat Squadron (then based on Segond Channel), No. 4 Repair Depot, No. 1 and No. 12 Servicing Units, Base Depot Headquarters, and No. 2 RNZAF Hospital. A transit camp and group headquarters were also sited at base depot. As part of the 1943 reorganisation, fighter and bomber maintenance units were divorced from flying squadrons and renamed servicing units, by which they were known

until the end of the war. Then, in January 1944, Group Headquarters moved forward to Guadalcanal. These and other changes were achieved only after long-delayed negotiations and a lengthy exchange of correspondence between the group commander and Air Headquarters in Wellington regarding the respective responsibilities of the two units, and a visit to Wellington by the group commander to urge his claims, most of which were finally agreed to by Air Headquarters. These are only the broad details of an involved organisation, the domestic details of which will be told in the separate Air Force history.

The consolidation of the New Georgia Group and the island of Vella Lavella, throughout September and October 1943, which forced the Japanese evacuation of Kolombangara, enabled air units to move still farther forward in readiness to cover advances by ground troops into the Treasuries and on to Bougainville itself, in accordance with the plan to destroy the strategic base of Rabaul. Two New Zealand fighter squadrons were therefore welded into a fighter wing under Wing Commander T. O. Freeman, DSO, DFC,30 and with their ground staffs moved forward to Ondonga in October, where they came under direction of the United States Marine Corps for impending operations. The wing consisted of No. 15 and No. 18 Fighter Squadrons, No. 2 and No. 4 Servicing Units, a tunnelling and sawmilling detachment (which was based on Arundel Island, separated from Ondonga by a narrow channel). Two radar units, Nos. 56 and 57, which had also gone forward and were stationed at Munda and Rendova respectively, also came under Freeman's command, as did the American operational aircraft in the area. The wing was based in a coconut plantation which became a sea of deep, evil-smelling mud, churned by constant activity and deluges of rain, but by 23 October, by dint of long hours of strenuous labour, the field was ready for operations and in time to give air protection for the landing in the Treasury Group on 27 October. That morning, as New Zealanders went ashore, eight aircraft from No. 18 Squadron covered the landing beaches from 5.40 a.m. to 8.40 a.m., and another four aircraft from 5.40 a.m. to 8.10 a.m. Other patrols maintained observation at two-hourly intervals. No. 15 Squadron also flew patrols throughout the day, but the enemy was not encountered until the afternoon when 30 to 40 Japanese divebombers and 50 to 60 fighters attacked landing craft on the beaches and in Blanche Harbour, a sheltered reach of water between the islands of Mono and Stirling. New Zealand pilots

accounted for four of them without loss. Four days later, aircraft from both squadrons maintained patrols over Rear-Admiral Aaron S. Merrill's huge task force for the landing at Empress Augusta Bay on 1 November, covering it until the small craft reached the beaches. Here eight aircraft from No. 18 Squadron patrolled the area and watched a landing which spread over twelve miles of beach below. One flight of eight aircraft, commanded by Flight Lieutenant R. H. Balfour,31 attacked a formation of 50 to 60 Japanese Zekes flying south towards Kahili and shot down seven of them. One pilot of this flight, Flying Officer K. D. Lumsden,32 lived through a series of misadventures which, in a few minutes, brought him near to death more than once. Two Japanese aircraft chased him south and anti-aircraft shells from an American destroyer damaged his plane; then an Allied aircraft fired at him by mistake and forced him to ditch his machine in the sea off Vella Lavella. The crew of the rescue barge which came from the shore mistook him for a Japanese and almost machine-gunned him before he could establish his identity. Two days later he returned to his unit.

November and December were periods of intense activity for the air units of the South Pacific Command, particularly the New Zealand fighter squadrons, for the thrust into Bougainville required the maintenance of constant pressure on any remaining Japanese bases. Despite fatigue, hard and difficult working conditions, heat, rain, mud and monotonous food, which were the daily lot of both air crews and ground staffs, flights operated from dawn to dusk, always on the offensive. Then, when the machines returned, maintenance crews took over, working through the night to have them ready for their missions the following day. The New Zealand fighter wing flew more than 1000 sorties in November and created a record no other air unit has ever established. Circumstances made this possible, since it was the first time two New Zealand squadrons operated together as a fully established wing. Rabaul was bombed almost daily after the Bougainville landing to prevent and break up any counter-attack from that quarter. On 11 November, anniversary of Armistice Day of the 1914–18 War, 700 aircraft took off from Munda in the heaviest attack made up to that time on the rapidly crumbling Japanese stronghold. On 17 December, by which time the Torokina airfield inside the perimeter at Empress Augusta Bay was ready for operation, 24 New Zealand aircraft under Freeman joined the Americans for a still heavier raid. The

machines left Ondonga and refuelled for the first time at Torokina before continuing their flight. Five Japanese aircraft were shot down by the New Zealanders during the raid, but unfortunately Freeman was lost. His damaged aircraft was last seen attempting to land in New Ireland, but no trace of him was ever found. On Christmas Eve another big strike at Rabaul included aircraft from the fighting wing. They shot down twelve Japanese aircraft and registered four probables, with the loss of five New Zealand pilots. It was the biggest daily bag of Japanese obtained by them in the Solomons.

During a reconnaissance raid on the Green Islands Group by elements of 3 Division on 31 January-1 February 1944, aircraft of No. 18 Squadron maintained a watch over Nissan Island to report any enemy counter-attack and maintain communication with the ground forces.

During the foregoing period No. 1 Bomber Reconnaissance Squadron, commanded by Squadron Leader H. C. Walker,33 and using Venturas, began working in the area from its base on Guadalcanal and then moved forward to Munda. One of its more important tasks was directing Catalinas to pick up airmen from the sea after they had baled out from damaged machines. The squadron flew 135 of these ‘survivor’ patrols and saved many airmen, particularly round Rabaul. For example, the Christmas Eve attack was followed by two of the squadron's machines, piloted by Flying Officer R. J. Alford34 and Flying Officer D. F. Ayson.35 Just as Alford spotted a pilot floating in the water in St. George's Channel, off Rabaul, his machine was attacked by three Japanese fighters. He damaged two of them and escaped into a cloud, but not before he had signalled the airman's position to the Catalinas. Ayson's aircraft was attacked by six Japanese machines over the same channel. One of the crew, Flying Officer S. P. Aldridge,36 who was acting as fire controller, was wounded in the running fight which ensued, and the navigator, Warrant Officer W. N. Williams,37 took over and continued the fight. Three of the Japanese machines were shot down. Ayson's Ventura was badly damaged but returned to its base. This action was commended in a personal letter from the American air operations commander. Ayson and Williams

were awarded the DFC, and the air gunner, Flight Sergeant G. E. Hannah,38 who was credited with two and a half Japanese fighters, was awarded the DFM.

New Zealand fighter pilots took part in all strikes on Rabaul, often acting as escort for American bombers, the crews of which frequently asked for New Zealand fighter cover. The New Zealanders' flying discipline was high, and only severe damage diverted them from their tasks and objectives. By the time No. 17 Squadron was due for relief in January, its strength had been gravely reduced by sickness and casualties. Both New Zealand and American airmen operated under extreme difficulty during the Solomons campaign, because of swiftly changing weather conditions and the fact that airfields were often widely scattered on islands hundreds of miles apart. On 17 January 1944 the New Zealand Fighter Wing moved still farther forward to the Torokina airfield on Bougainville, a move which reduced flying time to Rabaul by three hours. Squadron Leader J. S. Nelson acted as commanding officer after Freeman's death until the appointment of Wing Commander C. W. K. Nicholls, DSO, RAF, in February 1944.

The New Zealanders fought their last Solomons air battle against Japanese machines on 13 February 1944, when fighter pilots of No. 18 Squadron escorted American bombers over Rabaul. They brought the total of Japanese aeroplanes destroyed in the Pacific by RNZAF fighter squadrons to 99, but could never achieve the century. When 3 Division occupied the Green Islands Group on 15 February, the fighter wing, working with American units, maintained a solid cover over the atoll, but never encountered any Japanese. By the time the New Zealand pilots came on station the landing was over, and all Japanese opposition had been shot out of the skies.

From February 1944 the Japanese air force in the South and South West Pacific ceased to exist, though there were still many thousands of their ground forces in the jungles of Bougainville, New Britain, and New Guinea. Of 700 navy and 300 army aircraft which had flown into Rabaul throughout 1942 and 1943, only 70 remained to fly out again. With the capture of the Green Islands Group, which was virtually the end of the Solomons campaign, all ground activity centred on Bougainville, where the remains of 17 Japanese Army were trapped and isolated. New Zealand aircraft remained in the perimeter and assisted the American squadrons in bombing enemy concentrations and in driving off the attack which developed later by the fanatical

remnants of the ground forces. In March the fighter wing modified its aircraft and fitted bomb racks in place of belly tanks, so that these machines rated as fighter-bombers, carrying 500-pound bombs at first and later 1000-pounders. Nicholls led the first of these fighter-bombers over Rabaul on 7 March. Further changes were made in March 1944 when two dive-bombing squadrons, No. 25 commanded by Squadron Leader T. J. MacLean de Lange,39 and No. 30 commanded by Squadron Leader R. G. Hartshorn,40 reached Bougainville and were stationed at Torokina. Their servicing units arrived at Empress Augusta Bay during the Japanese attack on the perimeter. When the squadrons reached Torokina at the end of the month, they immediately joined the Americans in bombing and strafing enemy concentrations and gun positions beyond the perimeter. In May, when these two squadrons returned to New Zealand and were disbanded, they were replaced on Bougainville by No. 31 Squadron, under Squadron Leader M. Wilkes,41 and No. 20 Squadron, led by Squadron Leader S. R. Duncan, which was the first to reach Bougainville with the Corsairs with which the RNZAF fighter squadrons had been re-equipped in 1944. Although there was no air opposition in the final stages of the war in Bougainville, the New Zealand squadrons were constantly employed on reconnaissance work and in spraying Japanese gardens and rice fields with oil, after which these sources of food were bombed with incendiaries. This routine continued when American formations withdrew in 1944 and were replaced by an Australian command, which remained on Bougainville until the Japanese surrender in August 1945. Any necessary air support for the Australians was supplied by the New Zealanders.

New Zealand air units in the Pacific were as scattered as those of the Army, and much of their work, valuable and necessary to the vast strategic plan, was necessarily dull and monotonous, with only occasional missions to give it variety. Two of these units did particularly good work in saving survivors from torpedoed ships and in saving ships from submarine attack. No. 4 Bomber Reconnaissance Squadron, stationed in Fiji, gave cover to the American ship William Williams when she was attacked 120 miles south of Suva in May 1943, and saved her from further

attack while she was being towed into that port. Later that month when another American ship, the Hearst, was sunk near Suva by submarine, Hudsons from the squadron dropped supplies to the survivors. On 25 June 1943 a Hudson dropped depth charges on a submarine 180 miles south-west of Suva. It was probably RO-107, which the Japanese recorded losing that month in the South Pacific. The following month, while Hudsons of the squadron escorted the USS Saugatuck between Fiji and Tonga, they sighted and attacked another submarine. When the USS San Juan was torpedoed and sunk 300 miles south-east of Suva on 11 November, the squadron's aircraft covered her during rescue operations.

Catalinas of No. 6 Squadron, commanded by Wing Commander G. G. Stead, DFC,42 also originally based on Fiji, guided rescue ships to the San Juan after she was torpedoed, and picked up survivors from the American ship Vanderbilt who were found floating on rafts off Fiji. When the squadron moved to Espiritu Santo, Stead was succeeded by Squadron Leader I. A. Scott.43 It then moved forward into the Solomons and was based at Halavo, on Florida Island, from which it flew its first mission to rescue ten survivors seen floating on rafts 220 miles north of Florida. One of the squadron's Catalinas, piloted by Flying Officer W. B. Mackley, DFC,44 landed on the water and flew them back to safety. The next was the rescue of American airmen 100 miles south of Nauru, when a Catalina piloted by Flying Officer D. S. Beauchamp45 picked up five survivors from a Liberator which had been forced down on the water while returning from a bombing raid on Kwajalein. This was a tricky operation, hindered by a bumpy sea which so strained the hull of the craft that, after several attempts, she lifted off the water only with great difficulty. In February 1944 two Catalinas of No. 6 Squadron were detached and based on Blanche Harbour, in the Treasury Group, from which they flew on mercy missions and rescued 28 airmen from the sea between Bougainville and the approaches to Rabaul.

At Halsey's request, New Zealand supplied several radar units for service in the Pacific at a time when this vital service was most urgently needed and there was a shortage of trained men to operate the equipment. Radar was the silent service of the Air Force and

little was heard of these units, some of which were sited from necessity on isolated islands. Their difficulties were many, due principally to a lack of suitable sites on the islands. On 21 March 1943 the first RNZAF radar unit to reach Guadalcanal began operations with the American forces. Several more followed, and on 15 August No. 62 Radar Squadron came into existence under the command of Flight Lieutenant J. Conyers Brown.46 One of the most isolated units was No. 53, which was sited on the unoccupied island of Malaita, where the natives were none too friendly and the staff worked far from any other service organisation. No. 52 unit was sited on Guadalcanal, and received a letter of commendation from the United States Air Command for the accuracy of its plots of enemy aircraft during one of the heaviest raids on 7 April. It did similar work during another raid in June, when its information was invaluable in directing American fighters to the enemy. No. 56 unit was sited at Munda, New Georgia; No. 57 across the water at Rendova; No. 58 at West Cape on Guadalcanal; and No. 59 on Bougainville. Their work was of inestimable value to fighter control, with which they were linked, the whole being part of the anti-aircraft and air defence of any occupied locality. They gave adequate warning of the approach of enemy aircraft and directed the defending fighters towards enemy machines. The Japanese frequently confused New Zealand and American pilots by dropping strips of metal which distorted the readings on radar screens. Radar was not infallible, but it was invaluable to both navy and air force elements in battle. The last radar units returned to New Zealand from the forward area in February 1945.

By the end of February 1944, No. 1 (Islands) Group had been expanded to three fighter squadrons, three bomber reconnaissance, one dive-bomber, one torpedo and one flying boat squadron, with a total strength of 5108 all ranks. These were being expanded still further to twenty squadrons, which were to be ready by the end of the year as New Zealand's commitment to the war in the Pacific. Fifteen of them were to be employed in the forward area and the remainder on the home front to ensure exchange and relief, and all were to be equipped with American types of aircraft. This scheme was almost completed when the war ended.