Chapter 10: Fiji Units in Action

I: Training a Brigade Group

THE history of the Fiji Defence Force became inseparably linked with New Zealand from the time the Dominion accepted responsibility for the defence of the Crown Colony. Officers and non-commissioned officers were despatched from Army Headquarters in Wellington to train the Fijians and to direct the activities of the organisation, and the senior command became a New Zealand appointment from 1940 when Cunningham arrived with 8 Brigade Group. When 3 New Zealand Division was relieved by American forces in June and July 1942, the remaining Fiji Defence Force came under American command, though retaining its identity as an individual organisation with a New Zealander as commander. Finally, when the danger from Japan receded in the Pacific in the last days of the war, command reverted to Fiji and the New Zealanders returned to the Dominion. Invaluable work was done during those years and provided a pattern for any similar future operation.

Although, under the principle of unity of command, responsibility for the military security of both Fiji and Tonga was vested in the United States from 1942, New Zealand continued to provide essential equipment, supplies, and personnel for both the Fijian and Tongan forces, the majority, of course, going to the Crown Colony. When 3 Division left Fiji, New Zealand also agreed to the American request for the retention of certain units and men, principally coast and anti-aircraft artillery, until their relief by American units later in the year or early in 1943. Colonel J. G. C. Wales was gazetted in his new appointment as Commandant of the Fiji Defence Force and Commander 2 NZEF Pacific Section on 18 July, at which date there were 1500 New Zealanders in Fiji, including 1035 with artillery units. He established his new headquarters at New Zealand Camp, in the village of Tamavua on the main Suva-Samambula road, taking with him a nucleus of New Zealand officers and non-commissioned officers necessary to staff and direct the various services. Throughout

August and September new units were formed and the force expanded by agreement with the New Zealand Government until, on 1 November, the formation of an infantry brigade group was announced and Wales was promoted to the rank of Brigadier. At that time there were 221 New Zealand officers and 1340 other ranks with the Fiji Defence Force, which the following month changed its title to the Fiji Military Forces. From the complex organisation which then existed, all units, both New Zealand and Fijian, were regrouped to come under command of either brigade or administrative headquarters. By that time Wales had selected the following staff and commands:

| Brigade Major | Maj A. J. Neil, MBE |

| DA and QMG | Maj J. I. L. Hill |

| GSO 3 | Capt J. M. Crawford |

| Staff Captain | Capt E. E. McCurdy |

| Intelligence Officer | Lt W. E. Crawford |

| 1 Field Battery, Fiji Artillery Regiment | Maj H. G. Flux |

| 1 Field Company, Fiji Corps of Engineers | Maj F. H. Stewart |

| 1 Section, Fiji Corps of Signals | Lt A. T. Fussell |

| Composite Company, ASC | Capt F. G. Tucker |

| Reserve Motor Transport Company | 2 Lt C. Turner |

| 36 Light Aid Detachment | Lt R. W. R. Johnson |

| Senior Medical Officer | Lt-Col W. D. Stoney Johnston |

| Ordnance Workshops | Capt H. B. New |

| Pay Section | Lt F. J. Martin |

| Records Section | Capt G. A. R. Johnstone |

| 1 Bearer Company | 2 Lt R. D. McEwan |

| School of Instruction | Maj E. E. Lloyd |

| 1 Battalion, Fiji Infantry Regiment | Lt-Col J. B. K. Taylor |

| 3 Battalion, Fiji Infantry Regiment | Lt-Col F. G. Forster |

| 4 Battalion, Fiji Infantry Regiment | Lt-Col R. Fraser |

| Eastern Independent Commando | Capt P. G. Ellis |

| Southern Independent Commando | Capt C. W. H. Tripp |

| Northern Independent Commando | Capt N. W. Steele |

Colonel J. P. Magrane, a member of the Fiji civil service (Police), was officer in charge of administration and controlled 2 Territorial Battalion, which provided officers and men for the three regular battalions. Two labour battalions and home and bridge guards also remained under Magrane's command.

Under the Americans Fiji became a separate island command, commanded by Major-General C. F. Thompson, and all Fiji forces came under him for operations. American artillery ultimately took over the coastal batteries at Vunda, Momi, Bilo, and Suva from the combined New Zealand and Fijian gunners, leaving only the Flagstaff Hill battery to the Fiji command. As the Americans withdrew in February 1943 they handed back the

Suva and Bilo batteries, and 1 Heavy Fiji Regiment was created to control them, with Lieutenant-Colonel P. M. B. Barclay in command of the fixed coastal defences.

The Fijian Infantry Brigade came into being with the idea of sending a force overseas to play a more active part in the war, and this no doubt affected the commitment of units to the battle in the Solomons. At a meeting of the Council of Chiefs in September 1942, they were informed by the Governor that further calls would be made for men and materials on the Fijian community. The Council agreed but expressed the wish that a detachment of Fijians should be sent overseas. Recruiting among the villages was stimulated with this as the objective, since years of garrison duty in Fiji led to ultimate boredom. Although at this date New Zealand was hard-pressed to provide sufficient men to bring 3 Division to full strength, she fulfilled the Fijian request for further key personnel—first for 58 officers and 214 noncommissioned officers, most of whom reached the Colony at the end of the year, and a further 45 officers in January 1943. Increased supplies of equipment were also sent from New Zealand, which was not always kept as fully informed of the activities of the brigade as was consistent with calls for aid. This was remarked by Puttick in March 1943, in his comment on a signal from Fiji asking for further supplies and equipment because of the immediate prospect of one battalion and one commando unit leaving for the battle area. Puttick emphasised that New Zealand had not been consulted about any departure of troops from Fiji and that there was a danger that New Zealand might be compelled, through the pressure of events, to contribute resources in replacing men and equipment without having had any voice in the prior arrangements. This emphasised, also, the difficulties of commanding a small force within the framework of a large command. Wales was responsible to the Americans for operations, to New Zealand for supplies and some of his personnel replacements, and to the Governor of Fiji for the satisfactory employment of Fijian ground forces. However, the brigade was never committed as a formation. Negotiations to incorporate it in 3 Division foundered when the Governor, Sir Philip Mitchell, who succeeded Luke in 1942, refused to allow the commitment of single battalions at different places. In a message to the New Zealand Government during these negotiations he explained that he would have to explain to the Fiji Legislative Council why the Colony had gone to great pains and expense to raise, train, and equip a brigade, only to break it up unused and scrap its ancillary services. The whole trend of the discussions between Governments and commanders which followed proposals to use

the brigade with 3 Division, suggested a desire by the American command to use the Fijians as scouts and small patrols in the jungle, and this they eventually did. Two battalions, the 1st and the 3rd, and two units of commandos served in the Solomons under American command but never under their own brigade command, and the ultimate despatch of these units to the battle area suggested a political desire to keep faith with the promises made earlier to the Fijian Council of Chiefs.

In reorganising the Fiji forces Wales disbanded the commandos, which emerged as new units organised into guerrilla groups. By 31 December 1942 his force had increased to 6519 all ranks. Peak strength was reached in August 1943, when the number increased to 8513, of whom 808 were New Zealanders.1 Changes of command, both of staff and units, were frequent, and there was a constant flow of returning sick and replacements passing between New Zealand and the Colony as climate and conditions weeded out those not physically fitted for such arduous tasks. Wales insisted on hard training and placed emphasis on individuality and initiative in leadership. Indeed, one of the exercises he organised became memorable as a training exploit and indicated the excellent standard of physical endurance achieved by all members of his force. This required each battalion to march 100 miles in five days over the most rugged country and made exhausting demands on the men, who were required to climb a cliff face, cross rivers while harrassed by commandos, and traverse broken jungle tracks rising to more than 1000 feet. In February, the hottest time of the year in Fiji, 1 Battalion completed the exercise with the loss of only one man. Only a few months previously many of those men had been brought from distant villages, knowing neither the feel of boots on their feet nor the sight of rifles and accoutrements of war.

II: Guerrillas in the Jungle

The first Fijian force to undertake service in the Solomons was a special party of 23 guerrillas, commanded by Captain D. E. Williams, which was drawn from the Southern and Eastern Independent commando units formed as part of 3 Division and retained in Fiji after the division's departure. Williams had Lieutenant D. Chambers as his second-in-command and Sergeants S. I. Heckler, L. V. Jackson, F. E. Williams, R. H. Morrison, and M. V. Kells as section leaders. They reached Guadalcanal via the New Hebrides and disembarked at Lunga Beach on 23 December 1942. The Japanese garrison was then still fighting desperately

along the Matanikau River-Koli Point line, and the American command employed the Fijians to probe the wooded country behind the Japanese garrison. The first patrol, led by Heckler on Christmas Day, was uneventful, but on 28 December a second small patrol led by Sergeant Williams, acting as scouts for 182 US Infantry Regiment, wiped out a Japanese patrol at short range, and without loss or injury, on the left bank of the Lunga River.

This little action was fought out with grenades, rifles, and revolvers on sloping ground round the massive, tangled roots of a banyan tree, and was characteristic of swift individual action and thought which spelled victory in a type of warfare these men were fighting for the first time. As the remnants of the Japanese force fell back before the Americans towards Cape Esperance throughout January and February, patrols from Williams’ small but resolute force moved ahead of the advance, producing vital intelligence and creating havoc among the Japanese, whose morale was born of desperation. Their work was of such value that Major-General Alexander M. Patch, island commander of Guadalcanal, asked for more Fijian troops similarly trained for patrol work in densely wooded country.

The guerrillas wore camouflaged American jungle suits, the green and blotched material of which was difficult to detect among the tangled growth. New Zealand army boots were preferred to the soft rubber-soled jungle boot, and had a longer life. Arms were varied and consisted of Owen guns, rifles, revolvers and hand grenades, and the men all carried sufficient rations to last them for at least five days. Because mobility was of the first importance, these guerrillas carried as little personal gear as possible, consequently they suffered in some places from the unmerciful attention of mosquitoes. Patrols sometimes worked only one hundred yards apart but were unaware of the existence of each other. Malaria, control of which was not strictly administered until later, played havoc with this special party during its brief but intense period of activity, and when the Guadalcanal campaign ended every member of it returned to Fiji with the exception of Captain Williams and Heckler, who transferred to units which followed them into the combat zone. Before departing, however, they trained a group of Solomon Islanders under Major M. Clemens, a member of the civilian administration, who moved forward from island to island with the advancing troops, both American and New Zealand.

The American request for more Fiji guerrilla troops was met by the despatch of two further units—1 Commando Fiji Guerrillas and 1 Battalion, Fiji Brigade Group, both of which landed on Guadalcanal on 19 April. Tripp commanded the guerrilla unit,

which the American command designated South Sea Scouts. It was made up of 39 New Zealand officers and non-commissioned officers selected from the Southern and Eastern Independent Commandos, and 135 Fijians from the same units, organised into a headquarters of 24 all ranks and two companies of 75 all ranks, each commanded by a lieutenant. Each company was broken into three platoons, each of three sections, with a New Zealand sergeant in charge of each platoon and New Zealand corporals as section commanders. Twenty-eight Tongans, commanded by Lieutenant B. Masefield,2 increased the strength of Tripp's unit to 203 before it went into action on New Georgia. Further training was carried out on Guadalcanal to accustom all ranks to the new territory in which they were to fight. During this time two hundred Solomon Islanders were absorbed into the unit, and changes made in its organisation so that each platoon became a patrol, commanded by a New Zealand sergeant with a New Zealand corporal as his second-in-command. A unit patrol under Lieutenant P. M. Harper3 reconnoitred the island of San Cristobal, but apart from obtaining valuable experience in the jungle no Japanese were encountered there.

By the time the Fijian patrols were committed to action on New Georgia, American units of 14 Corps had established a bridgehead at Zanana, on the shores of the Roviana Lagoon, as a preliminary to an overland advance on their objective, the Munda airfield, instead of a more costly frontal attack across the water from Rendova Island, where a strong landing had been made on 30 June. From Zanana began the slow, difficult, and exhausting move forward through particularly dense forest country to the Bariki River, from which the final advance on the airfield, a distance of four miles, was to be made. The only lines of approach were along narrow, boggy native tracks.

Conditions and territory, the worst encountered up to that time, hindered all action. The Tongans under Masefield gave valuable assistance to American units, who found the jungle a barrier not easily overcome, either physically or mentally, since the narrow trails were stoutly defended by Japanese strongposts. Between Zanana and stretching for miles towards Munda was a swamp cut through by the outlets of the Bariki River, but another patrol of Tongans, led with courage and initiative by Sergeant B. W. Ensor,4 reconnoitred territory behind the Japanese lines

and discovered a good bridgehead site at Laiana, some distance nearer to the objective. This gave the American forces two bridgeheads on the Roviana Lagoon, divided by the swamp which ran for some distance inland into the jungle.

In planning his attack on Munda, Griswold gave his force ten days in which to capture the airfield, but it was not finally captured for 35 days, during which three divisions of American troops were committed to action. The Corps commander wished to employ both 1 Commando and 1 Battalion as scouts, but this scheme was abandoned because of Taylor's objection to committing his battalion piecemeal instead of as a whole unit. The scouting work therefore fell to the commandos under Tripp, and the battalion remained in the rear on the island of Florida until the following October.

The first task allotted to Tripp's unit was the clearance of islands in the Roviana Lagoon. This was little more than an exercise. Patrols were then allotted to units of 43 US Division, one with 169 Regiment on the right flank and others with 172 Regiment, both of which worked as combat teams. Fighting was confused and uncertain in the early stages of the costly struggle for Munda airfield as the division moved forward only a few hundred yards a day, clearing out nests of Japanese strongpoints and avoiding ambushes. On one occasion, when an American battalion ran out of food, it was supplied by the commandos, who transported rations and ammunition in native canoes up the Bariki River. Malaria and war nerves, brought on by close fighting under dense overhead cover, rapidly reduced the American strength.

Led by New Zealanders, the commando patrols acquitted themselves fearlessly in their first clashes with the enemy along the Munda and Lambeti trails, which led towards the airfield. Their information enabled American artillery to be used with reasonable precision on any strongpoints encountered along the jungle trails. Masefield, a most able leader, was the first New Zealand casualty among the commandos. He had spent some days with four of his Tongans in enemy territory, reaching the Bairoko Trail and moving along it to the outskirts of the Munda airfield. He was unfortunately killed while patrolling ahead of the Americans, caught in their artillery barrage. Two of the Tongans were wounded by splinters from the shell which killed their leader. On 12 July, while patrolling about 100 yards ahead of an American platoon of 172 Regiment, Tripp and 23 of his men were cut off when the Japanese opened fire on the platoon. They had run against a defended enemy bivouac area, with several

patrols established in the thick undergrowth. In the confused fighting which took place as the Fijian patrols tried to regain regimental headquarters, they were ordered to break into small groups and made their way to the rear under cover of darkness. Most of them eventually regained the main force the following day after personal adventures involving narrow escapes. Tripp, with some Tongans, encountered a patrol strongpoint. In a personal encounter he shot a Japanese, and was himself saved from injury when a cigarette lighter and cartridge clip deflected an enemy bullet, the force of which felled him. Before he regained his feet he accounted for another Japanese whose companions were firing at the fleeing Tongans. He then hid in the undergrowth. Under cover of darkness he made his way back to the American regiment, investigating enemy positions on the way.

Two other New Zealanders, Corporal A. M. J. Millar and Corporal W. F. Ashby,5 escaped by avoiding three enemy machine-gun posts and then got trapped in the line of fire of American artillery, which they eluded by moving only when the noise of the exploding shells drowned the sounds they themselves made. However, they destroyed an enemy machine-gun post on the way back. One of the Tongans who accompanied Tripp was knocked unconscious and woke to find himself stripped naked, with Japanese standing round him. He eluded them and returned to camp dressed in jungle leaves. The commando losses included their Tongan officer, 2 Lieutenant Henry Taliai, who was killed, and Sergeant W. G. Conn,6 a New Zealander, whose body was never found, but the information obtained enabled the American forces to ambush the Japanese and establish, at Laiana, the most important bridgehead for the Munda operation. It was only three miles from the airfield.

After fourteen days of such action, which tried both nerves and stamina to the limits of human endurance, most of the commandos were withdrawn on 15 July for a rest at Rendova. Tripp remained at Laiana, and a patrol under Sergeant N. B. MacKenzie7 continued to work with 169 Regiment. Reinforcements under Captain Williams reached Rendova on 16 July from the rear base which had been established on Guadalcanal. The following day Williams, with 70 other ranks, reached the headquarters of 43 US Division

in time to assist clerks, orderlies, and drivers who were manning their perimenter to drive off an enemy attack which developed after dusk in such close country that concentration was possible only a few yards away. On 18 July Harper relieved MacKenzie's patrol and joined 169 Regiment, taking Sergeant W. A. Collins8 and thirteen Fijians with him through Japanese-held territory. All this time Japanese patrols had been creating havoc and disorganisation among the American units by infiltration in the darkness, and on his return from Rendova, to which he had gone for discussions, Tripp organised several patrols to work with American units, reducing each of them, from necessity, to one New Zealander and four Fijians.

Casualties, malaria, and nervous exhaustion so depleted 43 US Division that 37 Division was committed to the battle on 23 July, making its headquarters north of the Laiana beach-head. The attack was then pushed forward, though slowly. Commandos worked ahead to points overlooking the airfield, and enemy concentrations were pinpointed so that artillery fire could be directed on them. Corporal J. H. E. Duffield9 was killed while working with 161 US Regiment, and Collins, who was personally credited with killing nine Japanese and destroying more than one enemy machine-gun post, was also killed when within five yards of a machine-gun post on the Munda Trail he was attempting to put out of action.

At the end of July the third American division, the 25th, was committed in the final struggle for Munda airfield, the outskirts of which were reached by Corporal V. D. Skilling10 and his Fijians on 27 July. Japanese resistance weakened under the increased pressure of this fresh division, and by 2 August the enemy garrison was retreating to the coast at Ondonga, fiercely resisting as it went, in order to cover a general evacuation to Kolombangara.

During the final assault on the airfield, a period of three days marked by determined and ruthless fighting, valuable work was done by the commando patrols, but they lost heavily. Heckler's patrol reported the withdrawal of stretcher cases and supplies down the Bairoko Trail to the coast, and this information enabled the United States forces to shell and bomb the track. One of the tragedies of the campaign was the death of Harper, who was killed after volunteering to take food and water to an American detachment which was cut off on the Bairoko Trail. On the way he fought off an ambush, killing the Japanese and capturing their

machine gun which, unfortunately, the patrol carried on with them. As they approached the isolated detachment, Harper and an American were killed before they could reveal their identity to a distraught garrison which was unable to distinguish friend from foe. The following day Ensor was killed while taking part in an attack for which he and his patrol had made the necessary reconnaissance. His desire to see the result of his work cost him his life. Munda was finally occupied by the American forces on 5 August. It had taken three divisions five weeks to fight through eight miles of jungle and swamp.

The American divisional commanders paid generous tribute to the courage and enterprise of the Fijian guerrillas and their New Zealand leaders. Beightler, commander of 37 US Division, in a reference to the work of the non-commissioned officers of the commandos, said that their capacity for traversing the jungle both by day and by night for many miles was not equalled by any American troops. The 43rd Division's commander reported at the conclusion of the operations that ‘During the entire period in which South Pacific Scouts were attached to this division, they patrolled constantly to our front and flanks and carried out special small patrols at our request. The work of these scouts undoubtedly was of great aid in the campaign and played a definite part in the capture of Munda airfield.’

These tributes were both modest and just. The New Zealand officers and non-commissioned officers exercised a steadying influence on the less-experienced American troops, many of them seeing action for the first time. Others had fought through the Guadalcanal campaign and were battle weary. Their losses were heavy from sickness, and malaria took its toll of exhausted men. Information obtained by forward patrols, which were never free from danger, was of immense value in giving the exact site of Japanese bivouac and defence areas, so that artillery fire could be directed on them with precision. As in other campaigns, the only reliable information available was obtained by men creeping through the jungle, since dense cover prevented any accurate observation from the air.

The commando unit returned to Guadalcanal on 12 August for rest and reorganisation, for after six weeks in the forward zone their relatively small force had lost 11 killed and 20 wounded. In the meantime American units continued pressing the Japanese and moved forward to Vella Lavella. On 31 August 50 commandos under Tripp landed on the island to join the 35 Regimental Combat Team, which was already there, and undertake reconnaissance work in the north of the island. Tripp

took one party of 16 men up the east coast to Lambu Lambu; Captain Williams, with a patrol of 20, followed the west coast, and then moved inland along old native tracks to a site in the jungle where coastwatchers, under Josselyn, were hidden with their wireless equipment; Graham, of 3 Division Intelligence, also reconnoitred Japanese tracks on the west coast of the island. These three groups worked through country later cleared of the enemy by 14 Brigade, but they made no actual contact with the Japanese since their task was solely one of investigation, recording the movement and dispersion of the enemy garrison.

These patrols were recalled to Barakoma on 18 September, the day on which 3 Division took over command of Vella Lavella from the American garrison. While waiting here they were visited by Wales, during the course of his tour of Fijian units in the forward zone prior to handing over his command before returning to New Zealand. He was succeeded on 12 September by Brigadier G. Dittmer, DSO, MBE, MC,11 after commanding the Fiji Military Forces for 14 months, during which he moulded them into a highly efficient organisation. Malaria had taken its toll, and many of the commandos were too ill to undertake further patrol work. The whole unit was therefore withdrawn from Vella Lavella on 25 September and returned to Guadalcanal, where it remained until 5 October and then moved to Florida Island. Brigade Headquarters, however, in the interests of morale and health, decided to withdraw the unit from the combat zone and replace it with another group. In November 1 Commando returned to Fiji and was finally disbanded on 27 May 1944.

The active service life of 2 Commando Fiji Guerrillas, commanded by Major P. G. Ellis, was a brief and unspectacular one. The unit was made up of 38 New Zealanders, 88 Fijians selected from the Northern, Southern, and Eastern Independent Commandos, all of which ceased to exist with the formation of the new unit, and 22 Tongans who joined the unit in November 1943. Training in Fiji, with which Ellis was associated from the inception of the Commandos, had hardened the men and made them efficient. Further training in the jungle was carried out on Florida Island, which the unit reached on 24 November and took over the camp occupied by 1 Commando. Patrols were also despatched to Santa Isabel Island, which was declared free of

the enemy. Ellis moved his unit forward to Empress Augusta Bay to come under command of 14 US Corps, landing there on 8 February 1944, and was delegated to undertake patrol work beyond the American perimeter. When the Japanese attack developed on 6 March, 2 Commando was given the task of defending 21 US Evacuation Hospital but resumed active patrolling on 14 March. In April, however, the unit was withdrawn, as its work was overlapping with that of 1 and 3 (Fiji) Battalions, which were also working with 14 Corps in the Empress Augusta Bay theatre. Most of the officers and men of 2 Commando transferred to the battalions and worked with them on Bougainville. The remainder returned to Fiji, where the unit was finally disbanded on 31 May 1944.

III: Battalions Move to the Solomons

Almost three years after its formation, 1 Battalion, Fiji Military Forces, sailed for the Solomons on 15 April 1943 in the USS President Hayes. Half the officers and many of the non-commissioned officers were New Zealanders, three of them former instructors lent to Fiji in November 1939. The battalion, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel J. B. K. Taylor, who had served with the New Zealand Division in Egypt and France during the 1914–18 War and later joined the Fiji administration, reached Guadalcanal on 19 April and occupied a camp at Kukumbona. On 8 May, after the American command had complied with Taylor's desire not to break up his unit into small groups for action in New Georgia, the battalion moved to a more agreeable camp site in the island of Florida. It remained there for five months, practising jungle tactics and landing exercises and carrying out such routine tasks as beach patrols and coastwatching.

Because of the increasing number of Fiji units in the forward zone and difficulties in obtaining particular stores and equipment, some of which took months to reach them, a forward base was established at Tenaru, on Guadalcanal, to service the battalion and the two commando units. The system of obtaining the necessary supplies from the American units to which they were attached did not prove satisfactory to the bulk of the troops, and it was felt that the increasing numbers of the force reaching the combat area warranted the establishment of a base to serve their needs. Lieutenant P. E. Holmes was the first quartermaster on whose shoulders fell the task of organisation. He was followed in December by Lieutenant F. G. K. Gilchrist. The original site was unsatisfactory and the unit's early life disastrous. Soon after

the camp was established, a Japanese aeroplane crashed 300 yards away and damaged tents and equipment. Two floods inundated the area, and then, on Thanksgiving Day 1943, an American ammunition dump a few hundred yards away caught fire and showered the camp with flaming fragments and sections of hot metal, which cut tents to pieces and set fire to store buildings. The unit then moved to Kukumbona on hills overlooking the sea, remaining there until the arrival of Captain M. P. Whatman in March 1944. A final site for the base was found in buildings vacated by 24 Field Ambulance of 3 Division when it moved forward to Green Islands in February. Here the forward base remained to serve all Fiji units in the Solomons until the end of their operational period.

On 8 October 1943, following the return of 1 Commando from the forward combat zone, 1 Battalion embarked on its first task, patrol work on the island of Kolombangara, to which the remnants of the Japanese garrisons from New Georgia and the surrounding islands had withdrawn on the first stages of their retirement to Bougainville. American units of 14 Corps had already crossed to the island and occupied Vila airfield on the southern coast, which they found deserted, but some uncertainty existed regarding the more mountainous north. On 11 October the battalion disembarked and occupied a bivouac area round the airfield, combing the coast and the jungle, only to find that the Japanese evacuation had taken place a week previously.

Units of 3 Division had by this time completed their task of consolidating Vella Lavella, only seven miles away from Kolombangara across the Vella Gulf. After a brief period of garrison work, 1 Battalion moved forward to Empress Augusta Bay, Bougainville, disembarking there from landing craft on 21 December. Taylor and his adjutant, Captain M. M. N. Corner, flew up the previous day from Munda for consultation with the American command, and on the evening of 20 December the battalion commander was injured during an enemy bombing raid on the American perimeter. He was succeeded by his second-in-command, Major G. T. Upton, whose arrival in Fiji in 1940 had been delayed a month when the Niagara in which he was travelling was sunk by an enemy mine outside Auckland Harbour on 19 June. He was promoted Lieutenant-Colonel, and commanded the battalion throughout the whole of its combat life.

The battalion now found itself a part of 14 US Corps, which had taken over the perimeter at Empress Augusta Bay from 1 Marine Amphibious Corps on 15 December, after the Marines had extended and consolidated the area.

The conquest of the whole of the large island of Bougainville was never considered in the overall Pacific strategy by Halsey and his staff, nor by MacArthur. However, a hold on the island was essential for the construction of airfields to cover further forward moves and to bring enemy air and naval bases in the New Britain-New Ireland and Caroline Islands regions within range of Allied aircraft. Empress Augusta Bay was selected for this next by-passing movement, and because it also provided an anchorage for a minor naval base. The Japanese command was deceived and mystified by activity promoted by American strategy which preceded the landing at Empress Augusta Bay. In addition to the landing by New Zealand elements in the Treasury Group and the diversionary raid by American troops on Choiseul, patrols were put ashore from submarines in the Buin and Shortland areas during October to confuse the issue. During October, also, aircraft under Brigadier-General Field Harris, commander of air forces in the Northern Solomons, averaged four attacks a day on Japanese concentrations and installations at Kahili, Kara, Ballale, Buka and Kieta. Altogether they flew 3259 sorties, for which aircraft of the Royal New Zealand Air Force squadrons stationed in New Georgia frequently acted as close cover.

All this activity had the desired effect. The Japanese commander moved men, artillery, and heavy equipment from the mainland of Bougainville to the Shortland Islands and to the south of Bougainville itself in anticipation of landings there. A naval task force under Rear-Admiral Frederick C. Sherman, built round the two carriers Saratoga and Princeton, held off any surface interference during the actual Empress Augusta Bay landing, which took place on twelve miles of beaches, some of them so unsuitable that 86 valuable landing craft were stranded during the operation. Marines landed on 1 November and established themselves in a perimeter after bitter fighting in country almost as aggressive as the enemy. Behind the beaches wild tangles of jungle covered broken and swampy ground cut by rivers, much of which became lagoons as the rising tide blocked the silted outlets and inundated large tracts of the foreshore. In areas devoid of trees, coarse native grasses and reeds higher than the men themselves created a barrier as formidable as the jungle.

The original beach-heads were extended throughout November and December until, by March, the perimeter ran roughly four miles along the coast and three miles inland, but it was overlooked by a series of low foothills shelving down from high mountain ranges which form the backbone of Bougainville. Patrols worked beyond the perimeter and gradually pushed out until the extreme

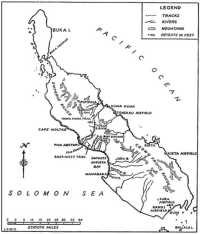

The island of Bougainville, where Fiji units fought as part of 14th United States Corps. Severe fighting took place in dense jungle beyond a perimeter first established between the Laruma and Torokina Rivers and afterwards extended beyond them.

boundaries were the Laruma River on the north and the Torokina River on the south, both of which issued from gorges in the Crown Prince Range. Strongposts in the foothills were held by American troops, and a 75-yards-wide strip of country had been cleared round the perimeter and partly protected with belts of barbed wire and land mines and covered with mortars and machine guns. Beyond the perimeter rose the 6560-foot crown of Mount Bagana, a steaming volcano which could occasionally be seen through the layers of storm clouds which swathed it.

Inside this giant bite of country, American engineers and naval construction battalions, working with the speed and precision which made them essential to any Pacific advance, constructed three airfields and a network of roads linking camps, dumps, and troop concentrations, as well as draining as much of the swamp lands as they could. It was a gigantic undertaking, second only to that on Guadalcanal. From the perimeter former native tracks radiated along the foreshore and into the mountains, following up river valleys to the opposite coast.

When the Fiji Battalion landed, American forces had established road blocks on these trails to prevent any surprise attacks from the main Japanese forces occupying the south and north-east coasts of Bougainville, with their principal concentrations round Buin, Kahili, and Kieta. The most disputed of these tracks was the Numa Numa Trail, which led through the mountains from the gorge of the Laruma River. Air observation by aeroplanes based on the Torokina and Piva airstrips, though valuable, was unreliable in country where ground movement could not be accurately discerned, so that all vital intelligence was obtained from patrols working through the rough country beyond the limits of the perimeter. Because of the desire to obtain as much intelligence information as possible without revealing their own strength, patrols were at first instructed not to fight unless they were forced to do so. Enemy patrols, on similar missions, worked down from the forest-clad hills towards the perimeter, so that these alert opposing groups, creeping through the jungle, continually tried to ambush each other and frequently succeeded. Lieutenant M. F. Fantham12 lost his life in one such ambush in February, after surviving earlier action.

Active patrolling by small groups from 1 Fiji Battalion began on Christmas Day in country as dense as any in the Solomons. First blood went to 2 Lieutenant N. N. MacDonald, whose patrol accounted for seven Japanese. Late in December loyal natives reported concentrations of Japanese along the north-east coast at Numa Numa and Tenekau, 40 miles across the island opposite Empress Augusta Bay, and in order to confirm these reports the battalion embarked on its most important undertaking, a reconnaissance in strength of the enemy area.

The task was allotted to a reinforced company of six officers and 198 other ranks under the command of Captain R. O. Freeman, which set out on 29 December for Ibu, a native village 30 miles beyond the perimeter and 1700 feet up in the dense forests of the Crown Prince Range. The route led along the Numa Numa

Trail, which began at the Piva stream inside the perimeter and followed the gorge of the Laruma River into the mountains. Its tortuous path, through ravines and over broken country, rose from stifling valleys where not a breath of wind stirred the heavy air, to chilly highlands of continual drenching rain, for this area is continually swept by thunderstorms of great violence. When the outpost was finally established at Ibu five days after leaving the perimeter, the men in their thin tropical uniforms suffered at that altitude from rain and cold. Because of the danger of ambush in the forest the men travelled as lightly as possible, and supplies were dropped to Freeman and his men from the air by parachutes gay with the colours which indicated their contents. Four large Douglas aircraft based in the perimeter spilled down the first supplies on the day of arrival, 2 January. This also helped to overcome the problem of warmth at night, for the men wrapped themselves in the parachutes and were able to sleep.

Ibu, 30 miles inside enemy territory, was immediately developed as a strongpoint. Road blocks were established along the approaches and patrols fanned out along the jungle trails, some of them reaching the north-east coast and returning with information of vital importance to the Corps commander, who was thus able to harass the enemy by directing air attacks on his concentrations and bivouac areas. The Japanese, aware of the activities of the patrols based on Ibu, frequently tried to ambush them. Lieutenant G. A. Thompson and Lieutenant Fantham, leaders of one strong patrol, fell into such a trap but fought their way out, Thompson spending the night under a fallen tree and escaping in the early morning by wriggling to a river bank, where he was helped by friendly natives.

Because of its value in supplying information, Griswold decided to retain the Ibu outpost for longer than at first anticipated, but the problem of evacuating the sick and wounded, which would have taken several precarious days over mountain trails, had first to be overcome. Upton and officers of Corps Headquarters visited the outpost early in January and decided that the problem could be overcome by carving a small airfield out of the forest. This was soon accomplished, using a few axes dropped from the air and the garrison's entrenching tools and bayonets to clear an area of ground 200 yards long by 50 yards wide. Every available man worked throughout the daylight hours, and on the third day a small reconnaissance plane landed and took off again without mishap. A regular but hazardous service began the following day from this tiny strip, so dwarfed by the forest around it that it

looked like a pencil from the air. Machines landed up the hill and took off down the slope. It was named the Kameli airstrip in honour of the first Fijian killed on the Ibu expedition and was an example of the ingenuity, enterprise, and spirit of the battalion.

Fortified by this means of communication, the work of the patrols went on through January, penetrating into the heart of enemy territory. The action of one such patrol, audaciously led by 2 Lieutenant B. I. Dent,13 who was killed in a subsequent action, ultimately found its way into American army textbooks as a model of jungle patrol work and determined leadership. It took place near the native village of Pipipaia, far beyond the outpost, when Dent's platoon was fired on by Japanese snipers in trees. These were disposed of, only to find that the patrol was close beside an enemy bivouac area. After fifteen minutes of brisk action, during which two machine guns were silenced and an unspecified number of Japanese shot down, Dent's sergeant suggested a temporary cease-fire. This ruse worked. When the Japanese emerged from cover in the belief that the Fijians were retiring, the waiting patrol mowed them down, concentrating on an old tin shed, in and out of which they ran confusedly. Dent and his men killed 47 Japanese without loss to themselves before they retired.

Intelligence reports at the end of January continued to indicate the massing of enemy strength in and around Ibu, despite the work of the patrols. Reinforcements under Captain J. W. Gosling were therefore despatched from the perimeter on 3 February to strengthen the garrison to ten officers and 411 other ranks. Then, on 8 February, Upton flew out to take over command, but by that time the Ibu garrison was almost surrounded by enemy moving in from both Buka and Buin. Such was his concern at the gathering enemy strength, for 600 of them were reported in high country at Vivei, well behind his small force, that Upton feared all escape routes back to the perimeter via the Laruma River would be cut off. On 14 February, in accordance with a prior arrangement, he requested 14 Corps headquarters to establish a road block to keep the escape route open.

A strong combined patrol from 129 US Infantry Regiment and 1 Fiji Battalion set out from the perimeter, but was driven back soon after it entered the rough hill country towards Sisivie and Tokua, two native villages which gave their names to the forest tracks leading to the garrison area from the rear. Almost simultaneously the Japanese began their attacks on road blocks

established along the tracks covering the Ibu post. Upton decided to evacuate the position and withdraw his force down the Ibu–Sisivie trail, which would bring him to the Laruma River and the Numa Numa Trail and so into the perimeter. Early on the morning of 15 February he despatched Corner from the outpost with the first section of the garrison, which included 120 native carriers with ammunition and radio equipment, and 100 native women and children from mountain villages who feared enemy reprisals. Upton followed at midday, leaving Gosling with a small rear party to cover him and join up later.

Meanwhile Corner found his way blocked by determined Japanese attacks on the road posts and retired along the trail he had just traversed, taking up a defensive position at a ravine which offered the only good natural barrier. He was joined there later in the afternoon with the main force under Upton, who was confronted with a disturbing situation. All escape routes were blocked by the Japanese, who greatly outnumbered him, and no help was available from American or Fiji units from the perimeter. He had little time to decide how to get 400-odd men and 200 natives over a mountain range and down to the perimeter unknown to the Japanese, who were now pressing the battalion patrols blocking the tracks along which Upton's force was extended. A Fijian sergeant, Usaia Sotutu, who had been a missionary on Bougainville for twenty years, saved the day. He remembered an old, disused track near the ravine and led the battalion along it, carefully camouflaging the entrance where it branched off the main trail the force had just used. The men began to move late on the night of 15 February, but the inky darkness in the dim recesses of the jungle and the pouring rain forced a halt until daybreak.

Gosling and his party were guided in that night by Corner, in such darkness that each man was instructed to hold the equipment of the man in front of him. A check of all ranks revealed that 25 were still missing, including a section under Sergeant B. D. Pickering which had manned a road block while the main party escaped. They rejoined Upton next day, after fighting their way through the jungle, as did all other small groups from the battalion. On 19 February the force reached the coast intact and with only one man wounded. In those four days, travelling slowly and with the utmost difficulty, the Ibu force climbed 5000 feet through dense forest drenched with rain, and carried arms and equipment, which included Vickers guns, 3-inch mortars, and food for more than 600 people—soldiers and natives. ‘The success of the

battalion at the Ibu outpost was one of the finest examples of troop leading that has ever come to my attention’, Griswold generously recorded in his report from Corps Headquarters.

The massing of these enemy troops in the neighbourhood of Ibu was a prelude to an attempt to drive the American forces off the island in a co-ordinated attack from both land and sea. Intercepted signals gave Corps Headquarters ample warning to prepare for this attack, which began on 9 March with an assault on the perimeter in what became known as the ‘Easter action’. All possibility of air and naval support from the sea, however, had been dissipated by the capture and occupation of Green Islands by 3 New Zealand Division on 15 February, a forward move which had immobilised Rabaul. Some dents were made in the perimeter defences, but American artillery, both field and anti-aircraft, boxed in the gaps in the wire through which the Japanese were attacking, and counter-attacks restored the line. At night battery searchlights and the headlights of tanks were directed on to low-lying clouds, which deflected the beams into ravines and valleys below so that any Japanese who moved there were revealed as targets. By 17 March 700 Japanese dead were counted before they were buried by bulldozers. During this action 1 Battalion remained in reserve behind 132 US Infantry Regiment of the Americal Division, one of the three American divisions holding the perimeter, but during lulls in the intermittent fighting, which continued for some time afterwards, battalion patrols searched areas outside the perimeter for snipers and infiltration groups.

On 23 March the Japanese attacked again, but with decreasing violence, and once more the American line was restored by vigorous counter-attacks. Immediately action died away, 1 Battalion began active patrolling outside the perimeter, usually moving with about 200 men from two companies extended on a 500-yard front, combing the jungle, brushing aside any small opposing groups, or indicating enemy positions for attention by artillery or aircraft. It was the kind of fighting requiring initiative and dash, for which the battalion was noted. On 25 March, during a battalion sweep in front of the sector held by 129 US Regiment which developed into an all-day engagement, Dent was killed and the unit lost one of its most promising young officers. The Japanese did not go easily. They stubbornly contested the pressure of battalion patrols along the Numa Numa Trail as they were forced back to the mountains.

Daily encounters developed into sullen actions, which often required the support of artillery and mortars before nests of

Japanese could be driven from the protection of splaying tree roots in which their defence posts were concealed. This work continued until 1 April, when patrols declared the area clear between the Numa Numa and Logging Trails, which ran into the valley of the Laruma River, on the left of the perimeter. Unburied dead and deserted stores and equipment indicated a retreat under cover of darkness. During one of its last patrols in this area, a Fijian soldier reported missing and killed three days previously was found still alive in a deserted Japanese dugout. He was Private Esivoresi Kete, a virile member of A Company, whose remarkable powers of endurance kept him alive. During an attack on an enemy strongpost he was shot through the head, the bullet entering behind the right ear and coming out below the left eye. When the Japanese found him they took his clothing and his rations, bayoneted him twice in the chest and once through an arm and believed him dead. The area in which he lay was thrice shelled by American artillery after the patrol to which he belonged retired. But he still lived, and in a period of semi-consciousness he crawled into the dugout in which he was found. Kete completely recovered and returned to his home on the island of Kandavu.

When the Japanese attacked the perimeter in March, RNZAF aircraft had moved from New Georgia and were stationed at Torokina with American formations. Because enemy artillery was able to reach the airstrips and endanger them, aircraft were flown each night for safety to Green Islands, where the strip was already operating, to Stirling Island in the Treasury Group, and to Ondonga in the New Georgia Group, returning to Torokina each morning to begin daily operations and aid the ground troops. All available New Zealand airmen were organised into three companies to assist with the defence of the airfields in the reserve area, and the commanders, Pilot Officer F. J. J. Angus, Flying Officer J. M. Molloy, and Pilot Officer E. D. B. Bignall, with a reserve company under Flight Lieutenant R. B. Watson, were allotted to positions covering the junction of the Piva Road and Marine Drive, two main roads leading to the Torokina strip.

Late in March, while 1 Battalion was engaged on extensive patrols, other Fiji units reached Empress Augusta Bay: they were 3 Battalion, command of which passed to Lieutenant-Colonel F. W. Voelcker, MC,14 on 22 December 1942, 1 Docks Company, and

Advanced Brigade Headquarters under Major J. R. Griffen.15 They went ashore on 24 March, and officers and non-commissioned officers from the battalion immediately joined those of 1 Battalion for experience. By 27 March the battalion's first patrol began operations, searching broken country for three days between the coast and Laruma River. At the same time the rest of the battalion was sent to clear a hill feature dominating a sector of the Numa Numa Trail known as OP9, but in face of determined opposition the force withdrew so that artillery fire could be directed against it. Even after an artillery barrage the enemy could not be dislodged, and finally a composite force consisting of two battalions from 37 US Division and 1 Fiji Battalion was brought in, only to find that the Japanese had withdrawn farther into the mountains.

When the force withdrew, 1 Battalion remained in the area until 6 April, after which 3 Battalion returned, took over, and combed the Java Creek-Laruma River area. Among the graves discovered in this area was that of Major-General Saito, who had been killed in the previous week's fighting and probably inspired the resistance. Battalion patrols moved in the wake of dive-bombing and artillery fire, with instructions to count the enemy dead, pick up any survivors and obtain all the intelligence information possible, but only one wounded Japanese was found. When this search was complete, 3 Battalion moved to its next assignment, the left-flank protection of an American force attacking Japanese detachments entrenched on a ridge overlooking the Saua River, on the southern rim of the perimeter, in country where bitter fighting had taken place soon after the original landing.

The East-West Trail, leading south from the Piva River and crossing the Torokina and Saua Rivers, cut through this area, well inland past Hill 600 and Hellzapoppin Ridge, two familiar and disputed features. Here the battalion spent a week, its patrols clashing almost daily with small enemy forces, during one of which Lieutenant O. W. Stratford16 was killed. Enemy attempts to ambush the Fijian patrols and isolate them by cutting the battalion supply line were constantly avoided.

At the end of a week's continuous activity, patrols reported that the enemy had moved into the valleys from the higher country, and artillery fire was directed on them, forcing them to retire still further beyond the perimeter. Road blocks established on both the East-West and Waggon Trails were taken over by 1 Battalion on 19 April to permit 3 Battalion to return for a rest.

Forward elements of 1 Battalion immediately advanced these road blocks and continued deeper into the enemy territory. On 21 April Lieutenant D. N. Mowatt17 showed resourcefulness and initiative in handling his platoon in one of the frequent situations calling for such qualities. He and his men were attached to a composite force ordered to sweep across the Saua River and then down to the coast to investigate enemy lines of communication. It was country thick with tall reeds and undergrowth and cut by tracks. As his forward section reached the beach it was attacked on both flanks, but the rear sections swung into action and killed 20 Japanese. An American platoon followed, fighting its way through to the beach to establish a bridgehead, which it did under cover of Mowatt's men. Mowatt afterwards skilfully withdrew his platoon, section by section, without loss, and landing craft uplifted the little force, which had accounted for 46 Japanese. Other patrols assisted an American force to clear two prominent features, Hill 150 and Hill 350, after which the battalion withdrew to the perimeter, where the Governor, Sir Philip Mitchell, visited all Fiji units and informed them that they would soon be returning to the Colony.

Meanwhile 14 Corps commander decided to push the Japanese farther back from the perimeter as they were still able to reach the airfields with field guns sited on high country, and on 29 May 1 Battalion moved back into the jungle to relieve American units holding posts in the foothills along the Laruma River. There, for sixteen days, working from a base established in the Doyabie River valley, strong patrols again combed country as rough as any encountered outside the perimeter. Almost daily they encountered enemy posts established to prevent any Allied movement through the mountains along the Numa Numa Trail, which had been widened to enable native carrying parties to maintain the Japanese during their attack on the perimeter during the Easter action.

Meritorious work was accomplished by Lieutenant A. P. Spittal18 and Lieutenant T. C. Scott19 in daring reconnaissance raids to pinpoint enemy positions for the supporting artillery. Arms, equipment, and documents captured by the battalion were a valuable indication of the enemy's condition. Solomon Island natives carried food and supplies to the battalion during this period of action, which ended with a return to the perimeter on 13 June. Preparations for departure continued through the next fortnight, and the

battalion sailed from Bougainville on 26 July. It had been engaged from 21 December to 13 June almost continuously, and claimed to have killed 418 Japanese and captured eight prisoners, with the loss of 33 killed in action and died of wounds and sickness and 64 wounded.

While 1 Battalion was engaged on its final task on Bougainville, 3 Battalion moved south on 31 May with instructions to eliminate enemy gun positions near the mouth of the Jaba River on the southern extremity of the perimeter. The force, supported by American artillery and engineers, moved south across Empress Augusta Bay in two LCTs protected by gunboats, and from a beach-head established without opposition at dawn, pushed patrols out along the Jaba Trail. The country here was difficult, and progress was hampered by tidal swamps and inland marshes cutting through the coastal strip. In places dense jungle gave way to more open tree-covered country of tall reeds and native grasses. On the fifth day the battalion reached the Maririci River, established a perimeter, and repulsed an enemy attack. Two days later, moving slowly, it reached the Mawaraka Trail along the coast which led inland to the Japanese headquarters at Mosigetta, a native village surrounded by plantations, from which well-protected trails radiated to mountain and coast.

During those seven days the battalion gathered up a considerable quantity of equipment, including two 75-millimetre guns, two 47-millimetre and two 37-millimetre, and destroyed quantities of stores and equipment. As the main force of the battalion moved along the coast and inland, other patrols moved up and down the coast, increasing their mobility by using small landing craft to establish beach-heads, and investigated any signs of enemy activity in the locality. When a gunboat arrived off the coast to support the ground force Japanese gunners opened fire on it, thus revealing the site of their 6-inch gun to the spotting aircraft which was operating with 3 Battalion. Dive-bombers from the perimeter attacked the gun site. After further brushes with the enemy the battalion was recalled to the perimeter on 6 June, where it continued training in readiness for other tasks to be undertaken after the departure of 1 Battalion.

On 21 June the battalion was again despatched to the Mawaraka area, with the dual task of destroying the Japanese headquarters at Mosigetta and aiding Solomon Island natives who had obtained arms and ammunition and were engaged in a limited resistance movement in country at the headwaters of the Jaba River. As on the former occasion, Voelcker's battalion was strengthened by the addition of American artillery, engineer and chemical mortar

units, and accompanied by a tank liaison officer, as it was anticipated that if the attack progressed satisfactorily tanks could be usefully employed. Once more the force moved south along the coast in landing craft to the mouth of the Jaba River. There was some confusion in getting the force ashore under cover of a smoke screen, as the wind changed, blowing the smoke back on the landing craft. E Company went in at the wrong point and had to be taken off again, but fortunately there was no opposition. After establishing a bridgehead, patrols moved out to secure with road blocks the Jaba Trail, which ran inland to the foothills. Late that same afternoon 100 natives who had escaped from the Japanese were brought in, giving the battalion information on enemy dispositions, but in view of later events this seems to have been inaccurate and of little use.

Maps of the region, although supplemented with air photographs, were incomplete and often led to confusion in the identification of rivers and tidal lagoons along the coast, most of which closely resembled each other. Early on the morning of 22 June three companies of the battalion moved farther south, with the intention of landing at Tavera River, three miles beyond the Jaba, leaving one company to protect the supporting artillery at the original beach-head. Once again there was confusion and the force landed instead at the Maririci, still farther to the south in enemy territory and within reach of Mawaraka. Here another perimeter was established for further operations. Behind the beach tidal lagoons and swamps of the river deltas made the country almost impassable, but a trail led along the coast, following the sandhills and a narrow belt of reasonably firm foreshore. The Japanese ranged on the beach-head, but fortunately any shells burst in the tops of the surrounding trees. At daybreak on the morning of 23 June, D Company continued to move south along the beach to Mawaraka Point, a small feature jutting out towards an off-shore reef and covering a village of that name which was occupied by Japanese. Good progress was made until the company began to cross an open stretch of country, which unhappily was covered by Japanese emplacements on the point. A supporting barrage for the advance was given by American artillery units on the coast and gunboats in the bay, and the company was able to establish another perimeter in preparation for a further advance. C Company, in continuing the advance to the point, ran into trouble where a section of beach was backed by tidal swamps and lagoons of the Hupai River delta. A Company attempted to go to its aid but was also pinned down.

Meanwhile E Company, which had moved about 300 yards inland in an attempt to join the Mawaraka Road, reached within

100 yards of its objective when it also was pinned down by enemy machine-gun and mortar fire. For three hours the company held to its swampy ground, while other companies of the battalion lent support until it could be withdrawn. This was done with difficulty and individual sacrifice which won the only Victoria Cross in the Pacific. When the company's leading scouts were hit, other men were wounded in abortive attempts to rescue them. Two of the wounded were rescued by Corporal Sefanaia Sukanaivalu, who in going back a third time was himself seriously wounded in making that perilous journey. Attempts at rescue only resulted in further casualties, and the Fijian NCO called to his men to leave him where he was. This they refused to do, calling out in their native tongue that they would never permit him to fall alive to the enemy. The Fijian corporal realised that such loyalty to him would result in further death and injury to his own men. He lay exposed to enemy fire, so that any movement drew a hail of bullets whipping through the rough grasses about him. In full view of the enemy and his own people he deliberately raised himself and was shot down. The following October, when Australian troops took over the perimeter at Empress Augusta Bay from 14 American Corps, they found his body and buried him with full military honours, with Fijian, New Zealand, Australian, and American servicemen in attendance.

Late in the afternoon of 23 June, Voelcker asked for and received permission to withdraw his force and return to the perimeter. Under cover of darkness that night the companies transferred to landing craft waiting off the beaches, to which some of the units made their way after losing direction and wandering for hours in the swamp. In this, the last active operation of the Fijian forces in the Solomons, 3 Battalion lost four men killed and fifteen wounded, but did not succeed in reaching the Japanese headquarters.

Dittmer, who retained his brigade headquarters in Fiji, flew to Bougainville to inspect the battalions before their departure. Griswold, the Corps commander, inspected the troops at a farewell ceremonial parade on 11 July, after which the units completed their final packing. On 26 July 1 Battalion sailed in USS Altnitah, calling at Guadalcanal to embark men and stores of the disbanded forward base. The ship reached Suva on 4 August and returned to Bougainville to embark 3 Battalion, which left Empress Augusta Bay on 23 August and reached Suva on 6 September. The Fiji Docks Company remained under American command, with Major A. W. Lewis as port operations officer, and assisted with the departure of the American forces and the

arrival of the Australians who relieved them. This company remained in the perimeter with the Australian command and departed from Torokina on 26 February 1945. With its arrival at Suva on 23 March the return of all Fiji units from the Solomons was completed.

Intensive training of the Fijian brigade continued in the Colony in anticipation of another move overseas to the Burma front, as the services of the force had been offered for that theatre, but it was never employed there. When the last of the American forces left Fiji in 1945, Dittmer moved his headquarters back to Borron's House and occupied the same quarters and offices as the first New Zealand force, remaining there until the end of hostilities. On 23 August 1945 a victory parade on Albert Park, scene of so many parades in the early days of the war, marked the end of the war service of the Fiji Military Forces. Demobilisation began from 1 September, but New Zealand officers and non-commissioned officers remained until the final records were completed. Brigade Headquarters ceased to function on 27 October, by which time there were still about 150 New Zealanders remaining with the force. Dittmer handed over to Magrane on 21 November 1945, and the intimate partnership of three years between New Zealand and Fijian soldiers ended.