Chapter 8: Encouraging Start of the Struggle at Sea

WITH THE collapse of France and the consequent loss of the French Fleet it became quite clear that the whole position in the Middle East would depend upon the retention of the British Fleet in the Eastern Mediterranean. Admiral Cunningham’s fundamental aim remained unchanged: it was to seek out and destroy Italian naval forces. He had always realized, from what was known of the enemy, that it might not be easy to bring about the encounters he sought, and, as has been seen, his first attempts, made immediately after the entry of Italy into the war, were unsuccessful. It was quite possible, however, that the attitude of the Italian Fleet had at that time been governed by Mussolini’s desire to secure the fruits of victory without any unnecessary fighting; but now that the elimination of the French had altered the balance to such a marked extent Admiral Cunningham had some reason for hoping that he would be more successful in bringing the Italians to action.

It is now apparent that only in the Central Mediterranean was this at all likely to occur. On the day of the birth of the Italian High Command, 31st March 1940, the Duce announced that the general policy of the Navy would be ‘offensive at all points in the Mediterranean and outside’. The Service Chiefs of Staff—Graziani, Cavagnari, and Pricolo—met ten days later and discussed how this directive was to be interpreted. Marshal Badoglio, the Duce’s Chief of Staff, held that it should not be taken to mean that they should throw themselves ‘with lowered head’ against the French and English fleets, but rather that they should assume dispositions aimed at interrupting the enemy’s sea communications, especially by the use of submarines.

On April 14th Admiral Cavagnari submitted to Mussolini an aide-mémoire expressing the view that, in the absence of any definite strategic objective to be achieved by the combined operations of the three Services, the task of the fleet should be to engage the enemy’s forces. It must be assumed that he had no offensive action in mind, and certainly did not intend to ‘seek out and destroy’. He visualized only two possibilities: the Allied fleets would either be content to maintain their hold in the eastern and western basins and rely on economic pressure to exhaust Italy, or else would act

aggressively with the object of rapidly neutralizing her. In the latter event the Italian naval attitude would continue to be defensive, because the French and British could quickly make good their losses from other forces outside the Mediterranean whereas Italian losses could not be replaced.

The collapse of France completely altered the balance of naval power, but the Italian naval staff adhered to their views on the question of losses. Their policy was to remain on the defensive at each end of the Mediterranean; only in the centre were they prepared, so long as their forces did not become engaged with greatly superior forces of the enemy, to act offensively or counter-offensively.1 To fulfil this condition it was very desirable that the Navy should be particularly well served by air reconnaissance. The Italian policy had been to refrain from building aircraft carriers because there was no part of the Mediterranean which could not be reached by aircraft from shore bases on Italian soil. With the exception of the recon-naissance aircraft carried by warships and the few which operated under local naval Commanders, all the aircraft which would be used for supporting naval operations were under Italian Air Force command. From the frequency with which shadowing aircraft were observed by the British Fleet it seemed that the Italian air reconnaissance was reasonably good, especially as it was seldom long before a force of bombers appeared on the scene. It will be seen, however, that the percentage of hits obtained by the customary high-level attacks was very small.

The fact that the Italian Navy was to be supported mainly by aircraft not under its own command would seem to have been a strong argument for insisting upon the closest collaboration with the Air Force. This was evidently not fully appreciated, for it was certainly not done. The failure must be attributed primarily to those who were responsible for high policy and for making practical arrangements for training and operational control.

Apart from Admiral Cunningham’s aim of coming to grips with the Italian surface forces, there were many other tasks demanding his immediate attention, of which the most important was to throttle the supply line from Italy by which the Italian forces in Libya were being built up. Bombardment of concentrations of troops and stores near the coast would contribute to this aim, but attack on the sea-borne traffic was of far greater importance. Apart from the limited means

at the Commander-in-Chief’s disposal for doing this, his hands were still tied by the convention which prevented submarines and aircraft from attacking vessels other than warships and troop transports. Even in the process of identifying the latter a submarine would run great risk of detection, besides possibly losing a favourable opportunity to fire torpedoes. The same restriction seriously hampered the achievement of a further objective, which was the denial of sea-borne trade to Italy; for example, the bauxite traffic from Yugoslavia and the tankers which came from the Black Sea via the Corinth Canal or the Kithera Channel. While a measure of control could still be applied in the Aegean by surface forces, these were severely handicapped by the lack of an Aegean base.

An essential requirement for carrying out successful offensive operations at sea was extended vision, and this could only be supplied by ample air reconnaissance. With all his other commitments the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief had the greatest difficulty in providing the Navy with more than a fraction of the air reconnaissance it needed, as there were only two squadrons of flying-boats (with a combined first line strength of nine aircraft) at his disposal for the Mediterranean. For reconnaissance in the Mediterranean to be effective it was necessary that many of the aircraft employed on it should be able to work from Malta, but the constant air raids during June and the lack of defence against them had made it hazardous to refuel even flying-boats except during darkness. In a signal of 1st July Admiral Cunningham therefore urged once more that fighters should be sent to Malta and that more air reconnaissance should be made available. He explained that as he could not even refuel light forces at Malta, it was only possible to take intermittent action against Italian transport and supply ships on their way to Libyan ports. His further representations in the light of operational experience and the steps taken to strengthen Malta are referred to later in this chapter.

Another task that was always present was the protection of British and Allied merchant shipping in the Eastern Mediterranean. On June 27th Admiral Cunningham informed the Admiralty of the shipping policy he intended to pursue. Trade convoys in the Aegean would be run periodically to connect with Red Sea convoys; convoys would be organized for oilers, transports, and armament supply ships moving between Haifa, Port Said and Alexandria, but other local shipping for Eastern Mediterranean ports outside the Aegean would be allowed to sail independently; and when occasion demanded he would run a convoy to Malta. In response to his request for a representative of the Ministry of Shipping in the Middle East, Sir Henry Barker was appointed on June 29th.

All this shipping had of course to be protected against surface

vessels, submarines, and aircraft. Distant cover by the battlefleet could provide against raids by the Italian Fleet; destroyers could provide reasonable protection against submarines; but there was little with which to counter the air menace from the Dodecanese. The anti-aircraft armament of ships themselves was inadequate; protection by fighters was not possible at such a distance from their bases; and the weight of bombing attacks that could be made on airfields in the Dodecanese was nothing like enough to neutralize them and was little more than a cause of irritation to the Italians

Just as the Commander-in-Chief was informing the Admiralty of his policy, an operation was actually in progress to cover a large movement in the Eastern Mediterranean, and it illustrates very clearly the interdependence of the various naval tasks at this time. Admiral Cunningham had planned to run two convoys, one fast and one slow, from Malta to Alexandria while the first of the Aegean convoys (A.S.1) was being escorted from the Dardanelles to Egyptian ports. For the latter, which originally consisted of seven ships but was subsequently joined by four more from Salonika, Piraeus and Smyrna, the two old 6-inch cruisers Capetown and Caledon with four destroyers were detailed as escort with orders to sail the convoy from Cape Helles on the morning of June 28th. Five destroyers were to sail from Alexandria at daylight on the 27th, carry out an antisubmarine sweep in the neighbourhood of Kithera and then proceed to Malta as close escort for the convoys to Alexandria. A covering force of the 7th Cruiser Squadron under the command of Vice-Admiral Tovey in the Orion would operate to the west of Crete, and a supporting force of two battleships, the Eagle and the 2nd Destroyer Flotilla would cruise south-west of Crete and act as the situation demanded.

Information about Italian submarine movements led to the five destroyers being routed instead through the Kaso Strait for an antisubmarine hunt to the north of Crete, and thence past Kithera to Malta. Barely half way between Alexandria and Crete an Italian submarine, Console Generale Luizzi, was sighted on the surface. It dived, was heavily attacked and damaged, surfaced again and was finally destroyed. The sweep passed without further incident until dawn on the 29th by which time the destroyers had passed through the Kithera Straits and were in position about 150 miles to the west of Crete. Another Italian submarine was then sighted on the surface. The attacks made upon it after it dived were unsuccessful, but meanwhile a third submarine, the Uebi Scebeli, was observed, also on the surface. As on the first occasion the vessel resurfaced on being damaged by depth charges, but when fire was opened the crew came on deck to surrender. The weather permitted boarding, and

some valuable confidential books and papers were seized. Prisoners from the two submarines amounted to 10 officers and 85 ratings. Flying-boats on patrol also had a number of encounters with sub-marines, and one of No. 230 Squadron had the good fortune to sink two—the Argonauto on the 28th and the Rubino on the 29th. From the latter she picked up four survivors.

The encounter with the Uebi Scebeli had taken place in almost the exact spot where, the evening before, the 7th Cruiser Squadron in its general covering role had engaged three enemy destroyers, now known to have been proceeding from Taranto to Tobruk. They had first been reported by a flying-boat of No. 228 Squadron at 12.10 p.m. on 29th May, when they were in a position about 50 miles west of the Ionian island of Zante and were believed to be steering towards Kithera. A later report from another flying-boat indicated that the destroyers were continuing to the south, so course was altered to intercept.

At 6.30 p.m. the enemy was at last sighted and fire was opened at a range of 18,000 yards. The course of the action was to the south-west, with the 1st division (Orion, Neptune, Sydney) on the starboard quarter of the enemy and the 2nd division (Liverpool, Gloucester) on the port quarter. Clever use of smoke by the Italians made ranging and spotting difficult for the British cruisers and shortly after 8.0 p.m. the Vice-Admiral broke off the action. By this time one of the enemy destroyers, the Espero, had been disabled, but continued to fire until 8.40 p.m. when she was sunk by the Sydney. Forty-seven survivors were rescued and an empty cutter with oars, provisions and water was slipped for any others. The action of the Italian destroyers in attempting to engage on a steady course in a duel with twelve 4.7-inch guns against forty-eight 6-inch was admittedly gallant, but with their turn of speed it would have been better tactics to turn away at once, then shadow, and attack with torpedoes during the night. As it was, the remaining destroyers Zeffiro and Ostro reached Benghazi the following morning.

Owing to the small amount of ammunition now remaining in the cruisers and to a report that numerous Italian submarines were at sea, the Commander-in-Chief postponed the sailing of the Malta convoys, directed the destroyers to return to Alexandria, and ordered the cruisers to afford support to the Aegean convoy. That night the 7th Cruiser Squadron swept up the west coast of Greece to Cephalonia, then turned and overhauled the convoy next day off the south-west corner of Crete. The ships had been subjected to a considerable amount of bombing and were re-routed past Kithera instead of through the Kaso Strait, though the attacks continued until they were well south of Crete. At least 85 bombs fell round the ships, without doing any damage. Meanwhile, the battle squadron

had patrolled without incident and all forces returned to Alexandria by July 2nd.

On July 5th it was the turn of the Fleet Air Arm to strike the enemy. No. 813 Squadron, armed with torpedoes, had moved from Dekheila to Sidi Barrani. Nine Swordfish launched their torpedoes against shipping at Tobruk while No. 211 Squadron RAF provided reconnaissance and eleven of its aircraft attacked the airfield. Twelve fighters of No. 33 Squadron RAF maintained patrols over the target. Seven torpedoes dropped inside the harbour and, according to an Italian report, the destroyer Zeffiro was sunk and another, the Euro, holed forward. Two merchant vessels, the Manzoni (4,000 tons) and Serenitas (5,000 tons), were also sunk and the Lloyd Triestino liner Liguria (15,000 tons) damaged. All aircraft returned safely. In his report the Commander-in-Chief stated that the success of this operation was due to the co-operation provided by the Air Force.2 While the attack was in progress the 3rd Cruiser Squadron (Capetown, Caledon) with four destroyers sailed as far as Bardia to bombard enemy shipping in that port and to render assistance to any returning aircraft in distress. Fire was opened at a range of 9,000 yards at dawn on July 6th and two military supply ships were hit. The force, though attacked by enemy aircraft, returned without damage. On the same evening as the attack was being carried out on Tobruk, No. 830 Squadron from Malta bombed hangars and workshops at Catania.

All this time there was the urgent question of the two convoys from Malta whose sailing had been postponed on 28th June; they carried men and stores required for the naval base at Alexandria, where their arrival was anxiously awaited. As it was expected that the Italians would dispute the passage of these ships, it was decided that the movement should take place under, cover of a fleet operation. As a diversion Force H was to cruise in the Western Mediterranean and carry out an air attack on Cagliari.

The fleet sailed from Alexandria on the evening of 7th July in three groups. Ahead was Vice-Admiral Tovey in the Orion with the remainder of the 7th Cruiser Squadron—Neptune, Sydney, Gloucester, Liverpool—and the Australian flotilla leader Stuart. The central group consisted of the Commander-in-Chief in the Warspite screened by five destroyers; some miles astern were the slower battleships Malaya and Royal Sovereign, the carrier Eagle (Nos. 813 and 824 Squadrons—seventeen Swordfish and two Gladiators) and a further ten destroyers. A few submarines were stretched on a patrol line across the Central

Mediterranean to report enemy movements. On the night of leaving harbour two submarines were attacked and probably damaged by the destroyer Hasty; their presence was only one of several indications that the Italians intended to harass the fleet from the moment it put to sea. Early on the 8th the submarine Phoenix reported two Italian battleships and four destroyers in a position half way between Benghazi and Italy steaming south, and flying-boat reconnaissance from Malta was directed to watch their movements. From this patrol the Phoenix did not return. Meanwhile, the Eagle’s air patrols sighted and bombed two more submarines.

Now began a series of high-level air attacks which persisted throughout the next four or five days. During the course of one forenoon the Warspite counted no less than 300 bombs dropped round her in 22 attacks, the most unpleasant occasion being when 24 bombs fell close along the port side simultaneously with 12 across the starboard bow, and all within 200 yards of the ship.3 The only hit was scored on the bridge of the cruiser Gloucester on the evening of the 8th, killing the Captain, six other officers and eleven men, and wounding others. The two Gladiators from the Eagle were in constant action and claimed to have brought down several enemy bombers.

Reports from a flying-boat late in the afternoon indicated that the enemy previously reported now consisted of two battleships, six cruisers and seven destroyers, and was about 60 miles north of Benghazi steering to the west of north. A later report stated that they had altered course to the eastward. To Admiral Cunningham this suggested that the Italian Fleet was covering a shipping movement to Libya, and this fact, coupled with the heavy air attacks he was experiencing, caused him to postpone the sailing of the convoys from Malta and move up at best speed so as to get between the enemy and his base at Taranto. It is now known that the whole Italian Fleet was returning after escorting an important convoy containing tanks and petrol to Benghazi.

At 6.0 a.m. on 9th July the Warspite was some 60 miles west of Navarino. In the van, eight miles ahead, were the cruisers; astern a similar distance were the slower battleships and the Eagle. Two hours later the enemy force appeared to be almost right ahead, about 145 miles, and flying-boats of No. 228 Squadron RAF reported it consisted of two battleships, sixteen to eighteen cruisers, and twenty-five to thirty destroyers. This was a very accurate estimate: the two

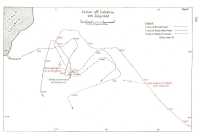

Map 8. Action off Calabria, 9th July 1940

battleships were of the Cavour class (12-inch); there were six 8-inch and ten 6-inch cruisers, and thirty-two destroyers. At 1.30 p.m. nine Swordfish of No. 824 Squadron made their first strike, but owing to an alteration of course they were unable to find the enemy battleships and attacked a cruiser. All torpedoes missed.

At 2.15 p.m. the fleet was between the enemy and Taranto, so course was altered due west. Contact was now imminent, and not wishing to be handicapped by the damaged Gloucester the Commander-in-Chief ordered her back to support the Eagle. The Malaya and Royal Sovereign were now racing up at their utmost speeds in a vain endeavour to join the Warspite before she became engaged with enemy battleships. At 2.47 the first sighting of smoke was made from the Orion, and fire was opened by the enemy half an hour later. The horizon became alive with a large number of ships which immediately concentrated on Admiral Tovey’s four cruisers. These, owing to the shortage of 6-inch ammunition on the station, carried only half their outfits. Heavily out-numbered, out-gunned, out-ranged, and unable to control the area ahead of the battlefleet, they were saved from a precarious position by the Warspite coming into action at 3.26 against enemy cruisers which then turned away under smoke. A short lull followed.

At 3.50 the enemy again came into view and the Warspite sighted two Cavour class battleships at 26,000 yards. Fire was exchanged and both sides obtained straddles. A few minutes later an unmistakable hit was observed at the base of the leading battleship’s foremost funnel. This was the flagship, Giulio Cesare. From signals made in plain language by the enemy it was learnt that the Italian Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Campioni, ordering his ships to make smoke, re- ported that he was constrained to retire, and the two battleships turned away. This retirement was observed by our aircraft to have been carried out in considerable confusion, and the enemy ships did not sort themselves out until after 6 p.m. Meanwhile, a second air striking force from the Eagle was unsuccessful.

The British destroyers, having been ordered to counter-attack, had now concentrated, and both they and the cruisers came for a time under heavy fire from enemy ships trying to cover the retirement of their battlefleet. Italian destroyers had made a half-hearted attack, but their torpedoes were fired at long range and all missed. During this period a Bolzano class cruiser (8-inch) received three hits from 6-inch shell and some Italian destroyers were also damaged. The Italian smoke screen was most effective. Cruisers and destroyers would dart out into the open, fire a few rounds and then disappear, which showed a clear determination on the part of the enemy to avoid close action. The targets presented were many and varied and the result was a most unusual battle in which the Malaya had now

joined. Enemy sorties from the cover of their smoke grew fewer and by 4.50 all firing had ceased. Admiral Cunningham had no intention of plunging into this smoke screen and decided to work round to windward and northward of it, for he suspected that the enemy had intended to draw our forces over a concentration of submarines.

This was, in fact, the aim of the Italian Commander-in-Chief, who had planned a running fight for the afternoon of the 9th. He hoped that with his superior speed, the proximity of shore-based aircraft, and the laying of a submarine barrage, he might be able to inflict damage with little risk to his own forces. Admiral Cunningham had suspected a submarine trap; as events turned out, his track passed some 60 miles north of the northernmost submarine. By 5.0 p.m. not a single enemy ship was in sight and the coast of Calabria was clearly visible 25 miles to the west. More high-level bombing attacks now developed on the British Fleet and lasted for four hours, during which the Italian aircrews distributed a large number of bombs on their own fleet also, even after the ships had begun to enter the Straits of Messina. Signals were overheard indicating the fury of Admiral Campioni, who stated in his report that his ships had frequently to react with gunfire, but that none of the bombs hit them. The episode showed clearly that the co-operation between the fleet and the shore-based bombers was very far from perfect.

So ended the action off Calabria. In spite of its disappointing material results, the action undoubtedly established a moral ascendancy over the Italian Fleet. In Admiral Cunningham’s opinion it must have shown the Italians that their air forces and submarines could not prevent our fleet from penetrating into the Central Mediterranean and that only their main fleet could seriously inter-fere with our operations there.

As soon as it was evident that the enemy had no intention of resuming the fight, the fleet turned towards Malta. That night an air striking force was launched from the Eagle to attack shipping in Augusta. Unfortunately the harbour was almost empty, but a tanker and a destroyer were sunk. For the next 24 hours the fleet cruised south and east of Malta while the Royal Sovereign and destroyers entered harbour to fuel. Meanwhile, on hearing that the fleets were engaged, the Vice-Admiral Malta had wisely sailed the convoys. During the passage back to Alexandria all forces experienced continual heavy high-level bombing attacks, but no ships were hit. On 12th July Blenheim fighters of No. 252 Wing provided fighter cover from late afternoon, after which no more was seen of the Italian bombers. Early next morning the fast convoy arrived, followed two days later by the slower.

The intention that Force H should carry out a diversionary operation has already been referred to. Admiral Cunningham had

suggested that this should include air attacks on ships in Naples, Trapani, Palermo, or Messina, but owing to lack of destroyers with sufficient endurance Admiral Somerville considered that the only feasible operation would be an air attack on Cagliari. With this object Force H consisting of the Hood, Valiant, Resolution, Ark Royal, three cruisers and ten destroyers left Gibraltar at 7.0 a.m. on 8th July. When south of Minorca, they met with continual heavy air attacks pressed home with such determination that although no ships were actually hit Admiral Somerville considered that the risk of damage to the Ark Royal outweighed the advantage to be gained from a minor operation. He therefore turned back to Gibraltar, and on the way the destroyer Escort was torpedoed and sunk.

After these operations the Admiralty made a policy signal defining the roles of the East and West Mediterranean forces and inviting Admiral Cunningham’s remarks on the composition of each as regards battleships and aircraft carriers. It was the intention to maintain a strong force in the Eastern Mediterranean as long as possible and another force at Gibraltar to control the western exit and carry out offensive operations against the coast of Italy. The Commander-in-Chief pointed out that in the Western Mediterranean the greatest danger to British interests lay in the possibility of attacks on Gibraltar and the break-out of Italian naval forces into the Atlantic. Both were unlikely while Spain remained neutral, and it was reasonable to suppose that the Italians were disinclined to proceed far from their bases. On the other hand, there were many Italian interests in the Eastern Mediterranean, where a British Fleet dominated the situation. For this reason, together with the fact that the west coast of Italy could easily be given air cover from Sardinia and Sicily, the enemy would probably base the bulk of his naval forces at Messina, Augusta, and Taranto. Hence the Eastern Mediterranean Fleet should be the stronger, and Force H should be regarded more as a raiding force.

As regards the composition of his fleet, he said that the Royal Sovereign class battleships were merely a source of constant anxiety and could be released at once. He wanted three, or if possible four, Queen Elizabeth class, including the Valiant, which was fitted with radar, a device not yet possessed by any of his ships: moreover she was armed with a battery of twenty 4.5-inch dual purpose guns which would be most useful in combating the air menace at sea and in harbour. He must have at least two capital ships whose guns could cross the enemy line at 26,000 yards and fast enough to have some hope of catching the enemy. It was also necessary to have two 8-inch cruisers to strengthen the forces in the van. He pointed out that he had not enough destroyers to take four battleships and the Eagle to sea simultaneously. The addition of the carrier Illustrious would, be invaluable,

as it would enable both an adequate striking force and a reasonable degree of fighter protection to be provided for the fleet. With the forces proposed he was certain that the Mediterranean could be dominated and the Eastern Mediterranean held indefinitely, provided that proper fighter protection was given to Malta and adequate air reconnaissance was forthcoming. He further believed that by a concerted operation from east and west it would be possible to pass the reinforcing, ships through the Mediterranean. With these views Admiral Somerville generally concurred, but emphasized that the main task of Force H must be the control of the Straits of Gibraltar; raids on the Italian coast would result in losses by attrition without accomplishing much of value. The redistribution of forces was finally decided upon and it was expected that the forces for the Eastern Mediterranean would be ready to leave Gibraltar for passage through the Mediterranean about 15th August.4 On Admiral Cunningham’s urgent representation reserve ammunition and spares were to be sent in fast merchant ships round the Cape.

Meanwhile a successful action between light forces had taken place in the Eastern Mediterranean. On 19th July four destroyers of the 2nd Flotilla—Hyperion (Commander (D) H. St. L. Nicholson), Ilex, Hero, Hasty—were engaged on a routine anti-submarine sweep to the north of Crete. At 7.22 a.m., as they were passing the northwest coast of the island on a westerly course, they sighted two enemy cruisers right ahead. These cruisers—both 6-inch—were the Bande Nere (flag of Rear-Admiral Casardi) and the Bartolomeo Colleoni; they had left Tripoli on the 17th to proceed to Leros and attack British shipping in the Aegean. Making an enemy sighting report, Commander Nicholson rightly turned his division 16 points (i.e. right round, through 180 degrees), by which movement he also hoped to draw the enemy towards the Australian cruiser Sydney (Captain J. A. Collins, R.A.N.), who with the destroyer Havock was operating about 40 miles to the NNE in search of Italian shipping.

The position of the destroyers was unenviable, for the superior speed of the enemy together with the range and power of their guns gave the Italians a preponderant advantage. But they threw it away. Instead of pursuing the retiring destroyers, which were now steering ENE, they altered course cautiously to the north under the misapprehension that because the destroyers were spread in line abreast they were forming a screen for heavier units. Fire was opened;

Map 9. Action off Cape Spada, 19th July 1940

the Italian shooting was erratic but the range too high for the 2nd Flotilla to respond effectively. Having increased his distance Commander Nicholson altered to a parallel course, but when the enemy eventually began to haul round to the east about 8 o’clock he turned back to a similar direction.

The Sydney meanwhile was steering south at full speed, acting on Nicholson’s reports but observing wireless silence. Thus at 8.26 a.m. the sudden flash of her guns in the north as she entered the battle caused surprise and consternation to the enemy, who believed they were now facing two cruisers instead of one cruiser and a destroyer. The Sydney’s firing was rapid and effective and the duel on parallel courses lasted only a few minutes. Turning to the south and west—flight to the eastward being blocked by Nicholson’s division—Admiral Casardi sought to escape and at the same time avoid punishment by making smoke and violently zig-zagging. This reduced his advantage in speed and enabled the range to be closed.

The battle had now developed into a chase with the Sydney concentrating her fire on the rear cruiser, and the destroyers joining in as they came within range. The Italian reply was ragged; the only hit the Sydney received penetrated a funnel and caused one minor casualty. At 9.23 the Colleoni was seen to be stopped five miles to the west of Cape Spada, apparently out of action. She had been hit in the engine room and the electric power had everywhere failed. Detailing the Hyperion, Ilex and Havock to finish her off, the Sydney with the remaining destroyers continued to pursue the Bande Nere which was disappearing to the southward past the west coast of Crete. An hour later, with the range still increasing and spotting rendered impossible by the haze and smoke, the Sydney checked fire, abandoned the chase, and set course for Alexandria. She had only four rounds per gun left for one of the foremost turrets and one round per gun left for the other.

In the meantime, two torpedoes had finished off the Colleoni, which had been abandoned by the majority of her company. Having rescued over 280 survivors the Hyperion and Ilex proceeded to join the Sydney, leaving the Havock to complete the work of rescue. Shortly after noon, however, enemy aircraft came on the scene and the destroyer with a further 260 prisoners on board was forced to retire at high speed. In the course of the subsequent air attacks a near miss did slight damage to the Havock. As a result of this experience the Commander-in-Chief issued a warning of the unjustifiable hazards involved in the rescue of survivors from enemy ships.

When the first news of the action reached the Commander-in-Chief at Alexandria he considered it probable that other enemy units might be in support, so he arranged for flying-boat reconnaissance, ordered the fleet to sea, and postponed the sailing of an

Aegean convoy from Port Said. It was soon evident, however, that the Bande Nere could make the African coast before being intercepted by any of our forces, and, when by 9.0 p.m. all reports of enemy movements in the Eastern Mediterranean were negative, the fleet returned to harbour. Successful bombing attacks were, nevertheless, carried out on Tobruk by Blenheim bombers of Nos. 55 and 211 Squadrons and by torpedo carrying aircraft from the Eagle. Hits were scored on two destroyers, two merchant vessels, and an oiler.

It had been amply demonstrated that Malta could, if adequately defended, play an important part in naval operations. The attempt made during June to fly Hurricanes across France to Malta and Egypt had been only partially successful, but even this route was no longer available. If more fighters were to reach Malta, some other way had to be found. On 12th July the Admiralty had informed the Commander-in-Chief that twelve Hurricanes for Malta and twelve for the Middle East would shortly be shipped in a merchant vessel for Gibraltar. Was it advisable, they asked, for this ship subsequently to be routed direct to Malta? Both Admirals Cunningham and Somerville considered this to be impracticable, and the latter pro-posed that the aircraft should be transferred to a carrier and flown off from a position south of Sardinia. Men and stores could be transported in two submarines.

Accordingly HMS Argus left the United Kingdom on 24th July: with twelve Hurricanes to be flown to Malta (operation HURRY). Postponement of the date of sailing of the Argus from Gibraltar to 31st July necessitated a change in Admiral Cunningham’s plans for creating a diversion. Nevertheless he was able to arrange for a sweep by cruisers and destroyers in the Aegean, which included a feint to the westward through the Kithera Channel on the evening of August 1st. Two battleships and the Eagle would advance to a point between Crete and Libya during daylight on 1st August, and he hoped that a general impression would be given of movement into the Central Mediterranean which would deter the Italian surface forces in Sicily and Southern Italy from moving westward.

The fleet had left harbour during the early hours of the 27th to cover an Aegean convoy which had been escorted from Cape Helles by two cruisers and four destroyers. To divert attention an attack and landing on Castelorizo was simulated by two Armed Boarding Vessels supported by light forces. As the convoy encountered heavy bombing in the Aegean, it was diverted to proceed west of Crete, where it was sighted and covered during the 28th by the main fleet, which had itself been subjected to a number of air attacks. No hits

had been obtained and no casualties suffered. In the course of these operations the Greek steamer Hermione, carrying aviation spirit for the Italians in the Dodecanese, was intercepted and sunk, her Master and crew being left in boats close to land. Ships returned to Alexandria on 30th July.

During the sweep planned for cruisers and destroyers between 31st July and 2nd August as a diversion for operation HURRY no incidents occurred and there was little bombing. In the battleship force, a defect in the Malaya caused the squadron and the Eagle to return to harbour soon after they had sailed. All these movements seem to have created such uncertainty in the minds of the Italians that, unable to decide whether to move east or west, they kept their ships in harbour throughout the operation.

Admiral Somerville arranged two subsidiary operations to conceal from the Italians his aim of flying off aircraft to Malta from the Argus. The first was an air attack from the Ark Royal on the Cagliari airfields, which it was hoped would weaken enemy air effort against the Argus; and the second was a simulation of activity in the northern part, of the western basin by the broadcasting of wireless reports by a cruiser lying off Minorca. The Force sailed from Gibraltar at 8.0 a.m. on 31st July; it consisted of the Argus, the Hood, the battleships Valiant and Resolution, the Ark Royal, two cruisers and ten destroyers. Italian air attacks began on the following day, but they were noticeably less determined than on the previous occasion; aircraft were seen either to jettison their bombs at a distance or to sheer off without dropping them.

That evening the Hood and the Ark Royal parted company from the remainder of the Force to carry out the attack on Cagliari, and, shortly before dawn, nine Swordfish armed With bombs and three with mines took off. Direct hits were scored on hangars, fires were started, several aircraft were hit on the ground, and the mines were successfully laid inside the gate of the outer harbour—all in the face of heavy anti-aircraft fire. One Swordfish crashed on taking off, another made a forced landing, but the remainder returned in safety. Meanwhile the Argus had arrived in position for flying off her aircraft at 4.45 a.m. and the operation was performed successfully. All twelve Hurricanes reached Malta, the only mishap being that one was damaged on landing. All forces then returned to Gibraltar by 4th August, without being further attacked from the air. A few days later the submarines Pandora and Proteus reached Malta with the necessary aircraft stores, thus completing a successful operation during which the weakness of the Italian reaction had been most noticeable.

Shortly afterwards Force H was ordered to the United Kingdom for reorganization in accordance with the decision to alter the composition

of the two naval forces in the Mediterranean. Admiral Somerville’s ships were to reassemble at Gibraltar on 20th August in preparation for the operation (HATS) in which naval reinforcements were to be passed through to Malta and the eastern basin.5

The first batch of Hurricanes to reach Malta after the French collapse was of course very welcome, but it was not only fighters that were wanted. In order to locate and follow the movements of the Italian Fleet and merchant shipping there was a need of reconnaissance aircraft to keep watch on Italian harbours and search wide stretches of sea. Without adequate information attacks on the Italian communications with North Africa could only be spasmodic. Malta was clearly the base from which the majority of operations for this purpose would have to be launched. Swordfish from Malta had made a successful attack on merchant shipping in Augusta and a Sunderland had possibly damaged a merchant vessel in convoy. But that was all. Admiral Cunningham represented that the security of Malta was the key to our Mediterranean strategy, and the prospect of the island remaining so weakly defended that it could not be used as an offensive base caused him the utmost concern. Not only was there a lack of air raid shelters and underground protection for indispensable services, but he doubted whether the fortress was strong enough to defeat a determined attempt at capture. The scale of defences approved more than a year ago showed little sign of being achieved. A much more vigorous approach to the problem was required. He therefore urged on 22nd August that the aim should be to make Malta fully usable by April 1941, when he would wish light forces and submarines to be able to operate from the island, in addition to bomber and reconnaissance squadrons supported by four squadrons of fighters. The base defences should be brought as quickly as possible to a state which would allow of this. In the meantime, offensive action ought to be restricted to attacks on sea targets.

The Chiefs of Staff had not been unmindful of the importance of strengthening Malta; in fact an allotment of guns and equipment was already on its way.6 As regards bomber squadrons, they had come to the conclusion that none could be spared to attack targets in Italy from Malta. Fighter squadrons presented a difficulty because the lack of reserves of all kinds meant that air and ground crews, aircraft and ground equipment could only be sent to Malta at the expense of Fighter Command, whose strength was still far below what was considered necessary for home defence. There were many other demands, too, for anti-aircraft guns, both at home and in the Middle East. Nevertheless the Chiefs of Staff agreed that everything

possible should be done to make Malta reasonably secure as a base for light forces, and they decided to bring the anti-aircraft defences up to the approved scale by 1st April 1941 by allocations from monthly production, and to make up the fighter strength to a total of four squadrons as soon as circumstances would permit.

On completion of operation HURRY the Commander-in-Chief had in mind no large scale operation before HATS. Ships needed docking, and destroyers all required boiler cleaning and minor repairs. He therefore carried out a number of local operations, including frequent anti-submarine sweeps by destroyers in the Eastern Mediterranean, sometimes combined with bombardments of the North African coast; the maintenance of pressure in the Aegean by cruiser patrols; and the cover of shipping. During the first of these operations four valuable barges and one tug which had escaped from the River Danube were encountered off Crete and escorted safely to Alexandria. In the course of three other similar sweeps no enemy forces were sighted. Even submarines were little in evidence, although eight to ten were always on patrol in the Eastern Mediterranean. In fact the only indications of their existence were the sinking of the Greek steamer Loula south of Crete on 31st July and the discovery of a newly laid minefield off Alexandria, which led to the sweeping of nineteen mines between 12th and 14th August. The usual air attacks were experienced, but even these showed markedly less weight and skill.

During one of these sweeps four destroyers, instead of returning to Alexandria, proceeded to Malta, where they arrived on 22nd August. After fuelling they were sailed to Gibraltar on temporary loan to Force H during the forthcoming passage of fleet reinforcements. When off Cape Bon the Hostile struck a mine and had to be sunk by a consort. The channel through which the destroyers were routed was the one planned for the reinforcements and therefore had to be changed.

Another of the fleet’s activities was to engage concentrations of enemy troops reported near the Libyan frontier, which were possibly assembling for the advance into Egypt. On 17th August the Commander-in-Chief himself took command of a force consisting of three battleships and an 8-inch cruiser (Kent) screened by twelve destroyers for the purpose of bombarding Bardia in co-operation with the Army and Air Force.7 The target area was well plastered

and the opposition was weak and ineffective, but Admiral Cunningham reported that the enemy’s skill in dispersion made this type of operation unjustifiable for heavy ships as long as warfare in the Western Desert remained static. It had, however, provided a useful opportunity to test methods of co-operation between the Services, and indeed the fighters had broken up air attacks on the fleet and brought down several enemy aircraft. Gladiators of the Fleet Air Arm working from Sidi Barrani destroyed others.

For further operations of this kind the gunboat Ladybird had now arrived on the Station. On 23rd August she carried out her first bombardment. Penetrating Bardia by night and finding no shipping, she proceeded to engage shore targets at point blank range from a few yards off the pier. It was believed that the moral effect of this action on the enemy was considerable, and it was clear that the use of gunboats off the North African coast would be of much value in conjunction with military operations ashore.

From experience so far gathered it was possible to assess the Italian menace with some accuracy. The reinforcement of the fleet by the two new battleships of the Littorio class (nine 15-inch, 31 knots) was believed to be imminent—in fact the Littorio and Vittorio Veneto came into service early in August—and the modernization of the battleships Duilio and Doria was almost completed. The chances of a fleet action had therefore increased. On the other hand, there was a general feeling that the Italians were unwilling to meet the British in open battle. Though they were capable of great individual gallantry, their leadership seemed poor and their training inadequate. Time and again submarines had been caught on the surface in daylight, and in spite of their numbers and their many opportunities they had achieved very little. Apart from the heavy cruisers at Calabria, ships had been handled in action with lack of skill and initiative, and the only battleships encountered had retired after receiving one hit.

The main threat was from the air, and only good fortune had enabled the fleet to escape so lightly from the intense high-level bombing to which it had been subjected, particularly just before and after the Battle of Calabria when ships were straddled again and again. As the number of bombs dropped ran into four figures, considerable damage might have been sustained. In Admiral Cunningham’s opinion the accuracy of these attacks was likely to increase with experience, and this factor would have to be carefully weighed when considering the employment of valuable ships in the Mediterranean. But he believed that if the anti-aircraft armament of ships was improved and a measure of fighter protection provided, this scale of bombing could be accepted as a reasonable war risk.

On the whole therefore the naval situation in the Mediterranean could be viewed with a certain amount of satisfaction. The first ten weeks of war had provided encouragement for the future, although there was still much to cause concern. The Italian Fleet was not the menace it appeared to be on paper: it did not seriously challenge the position of the British Fleet in the Eastern Mediterranean, and Admiral Cunningham had undoubtedly acquired an ascendancy over it. But by choosing when to go to sea it could pass convoys in safety to North Africa and so increase the land threat to Egypt. This in turn would imperil the Fleet base at Alexandria.

In aircraft and submarines we were too weak to provide more than an irritant to this movement. In spite of long and arduous submarine patrols, in which five boats had been lost,8 all that had been achieved was the destruction of three merchant vessels, apart from an Italian transport which had been sunk after striking a mine laid by the Rorqual off Derna. Aircraft made a number of attacks on shipping in enemy harbours; operations from Egypt—in addition to those already mentioned—included attacks on Derna, Bomba and Tobruk. On 3rd August three ships were hit by the Air Force at Derna; on the 9th, attacks were directed on naval oil tanks and vessels in Tobruk, where one ship was left on fire; and on the 22nd the three naval Swordfish operating with the Air Force from Maaten Baggush torpedoed in daylight one submarine on the surface off Bomba and a depot ship in the harbour. On August 27th bombers made another attack on Derna destroying one merchant ship. There were also attacks by single bombers on Tobruk.

The submarine sunk at Bomba, the Iride, had just embarked from the depot ship four underwater assault craft (human torpedoes) which were to have attempted an attack on British warships at Alexandria on the night of the 25th. This was the first attack of its kind to be planned in the Mediterranean during this war.

The enemy’s air attacks on British bases had so far been singularly ineffective. In the course of nine attacks on Alexandria during July and August they had only succeeded in sinking one mooring vessel, dropping an incendiary on an ASIS (happily empty), and penetrating the netlayer Protector with a splinter which killed one rating. Damage ashore was negligible and casualties low. Haifa, which provided a vulnerable target, had only been attacked three times, during which the oil tanks had received some damage. The first raid on the Canal area did not occur until 28th August, and this, too, did little harm.