Chapter 14: The First British Offensive in the Western Desert—I

See Map 15

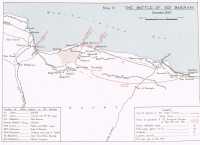

Map 15. The Battle of Sidi Barrani, December 1940

FROM THE moment of entering the war the Italians had frequent occasion to represent to the Germans that they lacked many kinds of up-to-date equipment. The Germans do not seem to have made any very great efforts to meet their needs; they preferred that German equipment should be used by Germans. If help was to be given to the Italians it had better be in the form of German units. It was accordingly suggested by Hitler in July that German long-range bombers might attack the Suez Canal from Rhodes. He did not press the point and nothing came of it, but when it became necessary to look for alternatives to the invasion of England the German staffs began to consider the use of their forces in the Eastern Mediterranean. The Army proposed that a corps of one motorized and two armoured divisions might be sent to strengthen the poorly equipped Italians in Libya, an idea which the Navy supported strongly because they regarded the Suez Canal as a most important objective which the Italians alone would be very unlikely to capture. Hitler gave his approval in principle, and General von Thoma was sent to Cyrenaica to study the problem. Meanwhile, the 3rd Panzer Division was ordered to prepare itself for North Africa. On October 4th the Dictators met on the Brenner and Hitler made his offer of mechanized and specialist troops, which Mussolini received without enthusiasm. They were not wanted, at any rate for the next phase—the capture of Matruh. But for the third phase—the advance to Alexandria—he admitted that he might need heavy tanks, armoured cars, and dive-bombers.

There the matter rested until von Thoma made his report. He had found the situation thoroughly unsatisfactory. Libya was a most unpromising theatre and the supply problem was very difficult. To add German troops in the present circumstances would only make things worse. He recommended that none should be sent until the port of Matruh was firmly in Italian hands. Hitler agreed with this in the main, though he did not give up the idea of sending long-range bombers to attack the Canal. The 3rd Panzer Division thereupon

ceased its preparations, and was placed in reserve for the intended operation ‘Felix’ against Gibraltar.1

Marshal Graziani was thus thrown back upon Italian resources, and, in fact, largely upon his own. He lost no opportunity of pointing out that although work on the water supply and on the road from Sollum to Sidi Barrani had made good progress, his resources were quite inadequate for an immediate advance upon Matruh. A great deal of forward stocking would be necessary, which had been impossible for want of a good road, and he had not enough transport to carry his troops across a very wide no-man’s-land and at the same time supply them at an ever increasing distance from the depots. The British, on the other hand, would be fighting within a reasonable range of their railhead; unlike him they did not have to rely upon one long incomplete road. What was more, their armoured division was by now refitted and rested, and he had not the means of dealing with it. The reply to all this was that his demands could not possibly be met, and on 5th November he was told that the principal Italian front was now in Albania, and that he ought to be helping by attacking the British so as to prevent the transfer of forces to Greece. Nothing immediately came of this but the impression was gained in Rome that Graziani would attempt a forward move about the middle of December.

All this time the British intelligence staffs were finding some difficulty in assessing the state of Italian readiness to resume the advance, though on the whole the administrative preparations seemed to be fairly complete. During the latter half of October the Italian papers and radio made frequent references to the imminence of great news from Egypt, but still nothing happened. Then came the attack on Greece, and Graziani made no move—not even as a diversion. By the middle of November it seemed that he must be ready to advance, but that considerations of high policy and perhaps the course of events in Greece would decide the moment.

But General Wavell did not intend to leave the initiative with the Italians a day longer than necessary. As far back as 11th September, when their first move across the Egyptian frontier was being awaited hourly, he had initiated a study of the whole problem of advancing into Cyrenaica, with particular attention to methods of supply. At this time his orders to the Western Desert Force were to conserve its strength in the opening stages of an Italian advance, but to counterattack if the enemy extended himself so far as to try to reach the Matruh area. This counter-attack was carefully prepared, and General O’Connor had every confidence in its outcome. So had General Wavell, who had formed a very low opinion of the Italians’ tactical skill and capacity to manoeuvre, and of the performance and

handling of their light and medium tanks. Within a few days of the withdrawal from Sidi Barrani he gave orders that if the Italians now attempted to capture Matruh they were to be struck an extremely heavy blow which was to aim at nothing less than the complete destruction of their force. With this aim in view the bulk of the Western Desert Force was disposed in the Matruh area, while the Support Group of the 7th Armoured Division maintained contact with the enemy. The 11th Hussars carried out their familiar task of far-ranging reconnaissance, and in October received a welcome reinforcement. This was No. 2 Armoured Car Company RAF from Palestine which, as D Squadron, was to work with the regiment for the next four months.

A month passed, and General Wavell judged that it was no longer necessary to await the enemy’s next move before attacking him. He thought it would be within the capacity of the Western Desert Force to make a long approach march and attack one or more of the enemy’s widely separated fortified camps which stretched from Maktila (east of Sidi Barrani) on the coast to Sofafi, 50 miles away to the south-west. The difficulties of supply would be great, but it ought to be possible to stage an operation lasting four or five days by making full use of the capacity of the British and Indian troops to endure hardship, manoeuvre by night, and live on short rations of food and water for a period. He was firmly convinced of their superiority over the enemy in everything but numbers, and this applied equally to the Air Force. He accordingly ordered General Wilson to make proposals for a short swift attack, after which the bulk of the forces would be withdrawn to railhead, and only covering troops left forward. The attack might perhaps be made simultaneously in the Sidi Barrani and Sofafi areas; and from the latter a force might strike north towards Buq Buq. The troops available would be 7th Armoured Division, 4th Indian Division, the Matruh garrison and the newly arrived 7th Royal Tank Regiment, equipped with heavy ‘I’ (Matilda) tanks.2 Nobody was to be told of the intention as yet except General Wilson’s chief staff officer; Lieutenant-General O’Connor, commanding the Western Desert Force, and Major-General O’Moore Creagh, commanding the 7th Armoured Division.

General O’Connor had already been thinking on these lines but had come to the conclusion that to attack the strongly held Sofafi group of camps simultaneously with the coastal group would involve too great a dispersion of the available forces. He proposed instead to attack first the centre group of camps, leaving those on the extreme flanks to be watched and dealt with later. The important supply

and water centre of Buq Buq would be a profitable objective for raids; and when the enemy’s administrative arrangements were thoroughly dislocated would be the moment to encircle Sofafi. This plan meant that the main attacking force must pass through the gap, fifteen miles wide, which existed between Nibeiwa and Rabia; from now on it would be necessary to ensure that this gap was kept open.

General Wavell agreed with General O’Connor’s plan, and on 2nd November ordered the senior commanders of the Western Desert Force to be informed of it, and of his own views on the feasibility and importance of the operation. By a bold stroke the Western Desert Force was to be thrust into the heart of the enemy’s position. There was a risk of discovery and heavy loss from air attack. In any case there would be much hardship and there might be heavy casualties. Great exertions would be called for, but this could be done with confidence: our troops were better trained and better equipped—especially the artillery with the new 25-pdrs; they were familiar with the ground and were better able than the enemy to adapt themselves to desert conditions. Self-confidence, esprit de corps, and a worthy cause were powerful assets. In short, quantity was going to be challenged by quality. There was no better way of helping the gallant Greeks than by inflicting a heavy defeat on the Italians in the desert and he was confident that it could be done. The operation, to be called COMPASS, would begin in the moonlit period at the end of November. The keynote was to be surprise, achieved by secrecy and deception.

For some days the plan looked like being wrecked by the need to despatch British forces to Greece and Crete, which entailed a serious reduction in the available numbers of fighter aircraft and the removal from the Western Desert of anti-aircraft guns, engineers, and transport, all of which were wanted for the operation. It has already been mentioned that the Secretary of State for War, Mr. Eden, was at the time on a visit to the Middle East:3 he was informed of the COMPASS plan and promised to do his utmost to hasten the arrival of the air reinforcements on which, in General Wavell’s view, the success of the plan largely depended. This led the Prime Minister to assure General Wavell that unremitting efforts would be made to this end, and that, although the timing of COMPASS would have to be considered in relation to the strength of the Air Force, General Wavell could count upon the full support of the Government in any well-considered resolute operation, whatever its outcome might be.

General O’Connor planned his operation in three phases. First, the 4th Indian Division and 7th RTR would pass through the

Nibeiwa—Rabia gap, wheel northwards, and attack in turn the camps Nibeiwa, Tummar East, and Point 90; in each case from the west—or rearward—side. The 7th Armoured Division would protect these operations from interference by any enemy from the direction of Buq Buq or Sofafi. Meanwhile, troops from the Matruh garrison were to pin down the enemy in Maktila camp, and ships of the Royal Navy would bombard Maktila and Sidi Barrani. The second phase was to be a move by the Indian Division northwards towards Sidi Barrani: meanwhile, the Armoured Division was to disrupt communications and generally play havoc in the direction of Buq Buq. Thirdly, if all had gone well, the Armoured Division might be ordered either to exploit in strength north-westwards or southwards towards Sofafi. The Navy would bombard coastal communications as far back as Sollum.

The plan for the Royal Air Force was broadly to intensify the activities which had, in varying degree, been continuous throughout October and November. During these two months frequent attacks had been made on the ports of Benghazi, Derna, Tobruk, and Bardia; on dumps, barracks, and airfields; and on coastal shipping between Derna and Sollum; the whole forming a sustained attempt to interfere with the enemy’s preparations for renewing his advance and to wear down his numerical superiority in the air. Just before the beginning of COMPASS the enemy airfields were to be systematically bombed from both Malta and Egypt. Offensive patrols would, as far as possible, protect the approach march and assembly of the attacking troops from discovery and interference by the Italian Air Force. The Air Force would then continue its programme of attacks on airfields, ports, supply depots, transport and troop concentrations.

It was an open question whether the Air Force would be able to carry out this programme in sufficient strength, and when it became necessary for the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief to send squadrons to Greece he was very much afraid that the weakening of his force would spoil the chances of success of operation ‘Compass’ and, at the worst, prevent it from being launched at all. It seemed to him that every aircraft that could possibly be made available for Egypt would be needed if the Army was not to suffer severely from the Italian Air Force. He was not at all content with the state of the plan for reinforcements of aircraft, and on 21st November took the drastic step of summoning Nos. 11 and 39 Squadrons (Blenheim I) from Aden and No. 45 Squadron (Blenheim I) from the Sudan. K Flight was also moved from the Sudan to Egypt to form a slender battle reserve of Gladiator aircraft. This involved the acceptance of risks in the Red Sea area, but the other two Commanders-in-Chief agreed with him that it should be done. A further risk was taken in denuding Alexandria almost entirely of its fighter defence by moving No. 274

Squadron (Hurricane) to the Western Desert. No. 73 Squadron (Hurricane), just arrived from England, moved to Dekheila near Alexandria on 12th December, but for the previous five days the fighter defence of the naval base consisted of two Sea Gladiators of the Fleet Air Arm.

By these means the following air forces were assembled for operation COMPASS: two squadrons of Hurricanes, one of Gladiators, three of Blenheims, three of Wellingtons and one of Bombays; a total of 48 fighters, and 116 bombers, all under the operational control of Air Commodore Collishaw, commanding No. 202 Group, with headquarters at Maaten Baggush.4 In addition there was an Army/Air Component, controlled directly by General O’Connor through a senior air liaison officer at Headquarters Western Desert Force, consisting of two squadrons and one flight of mixed fighter and reconnaissance aircraft; its employment will be referred to again presently.

The problem of maintaining the attacking forces was complicated by the great distance separating them from the Italian fortified camps which were to be the first objectives. In order to achieve surprise this distance would have to be covered quickly; thereafter the force would have to be kept supplied with its essential needs for a battle to be fought at anything up to 100 miles from the present railhead depots. It was necessary to reduce this distance somehow, because there was not enough transport to lift the attacking troops forward (and perhaps back again) and also keep up the daily maintenance of the whole force. During the preparatory period, therefore, two forward dumps or Field Supply Depots (Nos. 3 and 4) were established some forty miles to the west of Matruh, about fourteen miles apart—one each for the 4th Indian and 7th Armoured Divisions. Great pains were taken to conceal these depots and to avoid drawing attention to them in any way. They had to be specially guarded, as there was only a thin screen of troops between them and the enemy; the risk of discovery, and disclosure of British intentions, and perhaps of loss, had to be accepted. The stocking of the depots could not be done in addition to the daily maintenance work of the whole Western Desert Force without moving forward the railheads for 7th Armoured and 4th Indian Divisions; these were accordingly reopened at points nearer to Matruh, whence they had been withdrawn for better security during the period of waiting for the Italians to resume their advance.

The Field Supply Depots were stocked with five days’ hard scale rations and a corresponding sufficiency of petrol and ammunition,

together with two days’ supply of water at half a gallon for every man and one gallon for every radiator daily. Stocking of the depots began on 11th November and was completed by 4th December; the three M.T. companies engaged (of nearly 300 lorries in all) were then ready to lift troops of 4th Indian Division. From now onwards there was no transport at all with which to replenish the depots with anything except water, which was carried by water-tank lorries from a specially provided store. This was not ready until 7th December, the day on which the forward moves were to begin.

All these arrangements were of course not ends in themselves, though they were an essential means of giving the attack the best possible chance of success. Much thought was given to the tactics of the assault, because failure. at Nibeiwa would wreck the whole plan. Valuable experience of desert fighting had been gained in the past few months, but there had been no attack on a strongly held perimeter camp, protected partly or wholly by an anti-tank ditch, mines, and barbed wire; nor had ‘I’ tanks yet been used in the desert. These were to be the main assaulting arm, and the line of approach and points of entry would be chosen in every case to suit them. To achieve surprise they would have to make their final approach at speed. Techniques were devised for exploding and lifting the mines and for crossing the ditches. The task of the artillery and close-support aircraft would be to demoralize the defenders and cover the approach of the tanks. Bren carriers, machine-guns and mortars would support the rifle companies whose task would be to deal with minor centres of resistance after the tanks had broken in, and generally to mop up. All this required very careful co-ordination and a high degree of tactical training, as well as a thorough mastery of dispersed movement.

To try out these methods a training exercise was held on 25th and 26th November near Matruh. Only a few officers knew that the objectives marked out on the ground were replicas of the Nibeiwa and Tummar camps. The exercise was in fact a rehearsal; as such it was of great value and led to many improvements. To the troops it was represented as merely an exercise on the attack of enemy camps in the desert; on its completion they were told that a further exercise would be held. Meanwhile, the administrative preparations—which could not pass unnoticed—were explained as precautionary measures to meet the expected Italian advance. Such deceptions were highly necessary in a spy and gossip ridden country like Egypt. But rumour has its uses, and back in the Delta it was not difficult to put about stories that routine reliefs were taking place in the desert and that the British forces were being weakened, and would be weakened still further, to provide reinforcements for Greece.

There were some novel features in the air preparations also. The

Army/Air Component adopted, for the first time, a mixed organization, with fighter and reconnaissance aircraft in the same squadron.5 Experience in France and the Western Desert had shown that the Lysander, which was intended for army co-operation duties, was too vulnerable to carry out missions of tactical or artillery reconnaissance without fighter protection. It had been proved that co-operation with mobile forces could be undertaken with more economy and certainty by fighter aircraft, especially if the pilots had been trained in army co-operation duties. In the present case it was thought that troops in the attack might need close fighter protection from hostile aircraft and that this task and that of making low-flying attacks on a retreating enemy could most efficiently and quickly be carried out by aircraft under the direct control of the army commander. There were not enough fighters in the Middle East to replace all the Lysanders in the Army/Air Component, but the inclusion of a few made it possible for reconnaissances to be carried out by fighters and for escorts to be provided for the Lysanders when the need arose. This was the first practical application in the Middle East of the idea of Tactical Air Forces which were later to develop so greatly.

All through the preparatory period the Support Group of 7th Armoured Division was keeping up its aggressive inquisitiveness. Hardly a day or night passed in October and November without some part of the enemy’s defences being visited. From time to time there were encounters between patrols or mobile columns, never far from the enemy’s camps and often in the Nibeiwa–Rabia gap itself, culminating in an engagement on 19th November between the Left Column of the Support Group and a force of Italian tanks and lorry-borne infantry which emerged from Nibeiwa. Another force came out from Rabia but turned back. Five of the enemy’s medium tanks were destroyed and others damaged; eleven prisoners were taken and about 100 casualties inflicted. Thereafter the Italians were even less enterprising. The British losses were three killed and two wounded, all by air action. Reconnaissance elements of 4th Indian Division were gradually introduced, under the pretext of preparing to relieve the Support Group. From all these activities, and from air photographs, many of which were taken in the face of heavy fighter opposition, a fairly accurate impression was gained of the enemy’s dispositions. Most important of all, the Nibeiwa–Rabia gap was kept open.

In spite of the fact that it had been necessary for administrative reasons to plan an operation lasting only five days, General Wavell had no intention of giving the Italians any respite if they showed signs of ‘cracking’. In an instruction of 28th November he expressed to

General Wilson his belief that an opportunity might occur for converting the enemy’s defeat into an outstanding victory. Events in Albania had shown that Italian morale after a reverse was unlikely to be high. Every possible preparation was therefore to be made to take advantage of preliminary success and to support a possible pursuit right up to the Egyptian frontier. ‘I do not entertain extravagant hopes of this operation,’ he wrote, ‘but I do wish to make certain that if a big opportunity occurs we are prepared morally, mentally, and administratively, to use it to the fullest’.

On 2nd December General Wavell told Generals Platt and Cunningham, who had been summoned to Cairo from the Sudan and Kenya, what was about to happen. There had been a conference on future operations against Italian East Africa, the details of which are considered in Chapter 21. One of the decisions was that in the Sudan General Platt was to further the policy of helping the Patriot movement by maintaining pressure about Gallabat, where access could best be gained to the rebel area. He was also to make plans for attacking at Kassala with the object of securing the eastern loop of the Sudan railway and gaining a gateway into Eritrea. He was to assume that as soon as the 4th Indian Division had completed its task in the Western Desert, which would be about the middle of December, it would begin to move to the Sudan and come under his orders. The 6th Australian Division would join the Western Desert Force; one brigade group by the middle of the month, the whole division by the end.

On 5th December General Wilson sent his first and only written instruction about COMPASS to General O’Connor, who in turn issued his formal orders next day. (It could truly be said that there was the maximum of preparation and the minimum of paper.) The concentration began on December 6th with the move of 4th Indian Division from Maaten Baggush to Bir Kenayis, forty miles out from Matruh along the Siwa track. On December 7th the troops were told that this was not a second training exercise; it was the real thing. The assault would take place early on December 9th.

The information which the British had gathered about the Italian dispositions was on the whole accurate; but the picture was confused by the fact that at the end of November the enemy not only increased his strength in the forward area but also began to carry out reliefs. Actually, by 8th December the 1st and 2nd Libyan Divisions and 4th Blackshirt Division were in the Maktila, Tummar and Sidi Barrani camps; a strong mixed group under General Maletti was in Nibeiwa; 63rd Cirene Division in Rabia and Sofafi; 62nd Marmarica Division on the escarpment between Sofafi and Halfaya; while

64th Catanzaro Division had been moved up to an area east of Buq Buq, right opposite and behind the Nibeiwa—Rabia gap. Thus about seven comparatively weak enemy divisions east of the Egyptian frontier were to be attacked by one strong division and one armoured division.

The strength of the Italian air force in Libya was estimated at about 250 bombers and 250 fighters, which, it was always thought, could be supplemented from Italy at short notice. The actual numbers on December 9th were 140 bombers and 191 fighters and ground attack aircraft. Some of the bombers were based at Castel Benito near Tripoli; the others were grouped around Benghazi and Tmimi. Fighters and reconnaissance aircraft used the Tobruk, El Adem, and Gambut airfields. In order to cover the forward move of Western Desert Force the Royal Air Force had to aim at gaining temporarily complete air superiority, and the offensive against airfields was begun on December 7th with the attack on Castel Benito by eleven Wellingtons from Malta. Twenty-nine Italian aircraft were destroyed or damaged on the ground.6 Throughout December 8th three squadrons maintained offensive fighter patrols over the British concentration areas. That night twenty-nine Wellington and Blenheim IV bombers heavily attacked Benina, near Benghazi, and destroyed or damaged a further ten Italian aircraft; Bombays bombarded the area of the defended camps; and Blenheims attacked the forward airfields.

On land the preliminary moves went smoothly. In the coastal sector a mixed force under Brigadier A. R. Selby made up of units and detachments from the garrison of Matruh, about 1,800 strong—the most for which transport could be provided—had moved out from Matruh with the task of preventing the occupants of Maktila from giving any help to the Tummar camps. Having stationed a brigade of dummy tanks at a harmless part of the desert to act as a decoy to the Italian Air Force, Selby Force moved into position before daybreak on 9th December a few miles to the south and east of Maktila. Maktila itself was heavily bombarded for an hour and a half in the middle of the night by the monitor Terror (twin 15-inch and eight 4-inch guns) and the gunboat Aphis, helped by flares and spotting from a Swordfish of the Fleet Air Arm. At the same time the gunboat Ladybird bombarded Sidi Barrani.

The camp at Nibeiwa, a rough rectangle of a mile by a mile and a half, had a perimeter wall all round, protected by a tank obstacle of a bank and ditch. It was known that mines had been laid on parts of the front, but in the north-west corner there was an entrance habitually used by the supply lorries where there might well be no minefield. A special patrol of 2nd Rifle Brigade verified this point

on the night of December 7th/8th, and it was finally decided that this was where the assault would be made. On this decision depended the selection of the final rendezvous, a point six and a half miles south-west of Nibeiwa.

The 4th Indian Division (Major-General N. M. de la P. Beresford-Peirse) halted, well dispersed, for 36 hours in the Bir Kenayis area. On December 8th it made a long move by day of over sixty miles to a rendezvous only fifteen miles from Nibeiwa. The sky was clear at first but there was a ground haze; as the day wore on it became overcast, and the visibility grew less. Everything possible was done to reduce the dust but there was of course a considerable risk of discovery. As it was, only one Italian aircraft was seen, at about midday, but nothing occurred to suggest that it had observed anything unusual. At dusk the force which was to capture Nibeiwa—the 11th Indian Infantry Brigade Group (Brigadier R. A. Savory) with 7th RTR (Lieutenant-Colonel R. M. Jerram) under command—was again on the move and covered the thirteen miles to the final rendezvous in darkness. Farther to the south-west the 7th Armoured Division (Brigadier J. A. L. Caunter in temporary command) was assembled, with the 4th Armoured Brigade (Colonel H. L. Birks in temporary command) leading, in preparation for its task of preventing interference with the 4th Indian Division next day by any enemy from the direction of Azziziya or Sofafi. The precision with which these difficult and important night marches were done reflected great credit on the staff and troops, and was largely responsible for the subsequent success.

The night was bitterly cold. At first the Italians in Nibeiwa were alert, firing and sending up flares. This lasted until midnight, and shortly before 5 a.m. they were roused again by a diversion created by a detachment who fired into Nibeiwa from the east and generally attracted attention to that quarter. By 6 a.m. this excitement also had died down. By 7 a.m. the 4th Divisional Artillery had come into action to the south-east of the camp and although hampered by the haze began to register targets. At 7.15 a.m. 72 guns opened with concentrations on selected targets and at that moment two squadrons of 7th RTR supported by 31st Field Battery R.A. bore down upon the north-west corner of the perimeter. On the flanks of the ‘I’ tanks were the Bren carrier platoons of 2nd Battalion The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders and 1/6th Rajputana Rifles, firing as they advanced.

Outside the camp were about twenty medium and a few light Italian tanks, unready for action; these were quickly overrun. Not until the ‘I’ tanks entered the camp were they opposed or obstructed at all; but immediately afterwards the Italians opened artillery and machine-gun fire, and a few gallant but useless attempts were made

to check the ‘I’ tanks with grenades. At 7.45 a.m. the Cameron Highlanders, who had moved up in lorries to little more than half a mile away, were ordered to advance, followed by the Rajputana Rifles. Tanks and infantry now quartered the camp methodically, helped by a section of 31st Field Battery R.A. firing at point blank range at a few stubborn and isolated centres. By 10.40 a.m. all was over. General Maletti had been killed, and some 2,000 prisoners taken. Large quantities of supplies and water were found intact. British casualties were eight officers and forty-eight men.

Meanwhile 5th Indian Infantry Brigade (Brigadier W. L. Lloyd) and 25th Field Regiment R.A.—less 31st Field Battery—were moving up west of Nibeiwa preparatory to attacking the next objective, Tummar West camp. The remainder of the divisional artillery moved up to the east of Nibeiwa into position for supporting this attack, being bombed from the air as it did so.

Tummar West camp was not unlike Nibeiwa, and of roughly the same size, with a low parapet and a tank ditch, neither of which was continuous. Air reconnaissance had shown that here too the defences were weakest at the north-west corner, and the plan for the break-in was consequently much the same as for Nibeiwa. 7th RTR, having lost six tanks on a minefield as they left Nibeiwa, joined the 5th Indian Infantry Brigade at 11 a.m. The day had become dull and overcast and a sand-storm was rising, which made the recognition of targets and objectives very difficult. At noon the artillery began to register. An hour later the tanks advanced and broke through the perimeter without difficulty. There was more opposition from the garrison than at Nibeiwa and again the Italian gunners fought courageously. Twenty minutes after the tank assault 1st Battalion The Royal Fusiliers, followed by 3/1st Punjab Regiment, literally drove up, for the drivers of 4th Reserve M.T. Company, New Zealand A.S.C., brought their lorries through artillery and machine-gun fire to within 150 yards of the western face of the camp. (Not to be outdone many of the drivers then joined in the fight.) By 4 p.m. all resistance was over except in the extreme north-east corner.

Six tanks of 7th RTR then moved off to attack Tummar East. 4/6th Rajputana Rifles, who were to follow them, came under fire from the enemy still holding out in Tummar West, and had then to meet a counter-attack made by Italian infantry and light tanks who emerged from Tummar East. By the time they had successfully dealt with this, inflicting heavy casualties and taking many prisoners, it was too dark to press home the attack on Tummar East, though the ‘I’ tanks, having advanced by a different route, had already forced their way in.

All this time the left flank and rear of 4th Indian Division was

being protected by 4th Armoured Brigade. Passing to the west of Nibeiwa at first light the brigade advanced north and north-west towards the Azziziya area. There was no interference from the air but there were desultory encounters and a certain amount of shelling; prisoners were taken here and there. At Azziziya the garrison of 400 surrendered and no tanks were found. Light tank patrols of 7th Hussars penetrated across the Sidi Barrani-Buq Buq road, while the armoured cars of 11th Hussars moved out farther to the west. Thus in general 4th Armoured Brigade dominated the area to the west of 4th Indian Division and was soon in a position to prevent the enemy from reinforcing Sidi Barrani. The 7th Armoured Brigade was held in reserve, while the Support Group kept the approaches from Rabia and Sofafi under observation and protected the southern flank.

News of the fall of Nibeiwa did not reach Brigadier Selby’s Force until 3.20 p.m. He was unaware of the situation at the Tummars but nevertheless decided to send off a detachment in an attempt to block the westerly exits from Maktila. The difficult going and darkness prevented the accomplishment of this task, and the 1st Libyan Division made good its escape during the night.

No reports from Selby Force had reached General O’Connor when at 5 p.m. on December 9th he joined General Beresford-Peirse in Tummar West camp and decided upon plans for the next day. The 5th Indian Infantry Brigade was to clear up Tummar East, and 16th Infantry Brigade, which had been in divisional reserve and was now pushing on as far as possible to the north before nightfall, was to continue northwards and get astride the roads leading to Sidi Barrani. Two field regiments of artillery moved up during the night to support the advance and 7th RTR worked hard to get as many tanks into action as possible.

The operations on December 10th bore little resemblance to the more precise tasks of the previous day, because the enemy’s dispositions were unknown and there was not the same element of surprise. Shortly before 6 a.m. the commander of 16th Infantry Brigade (Brigadier C. E. N. Lomax) decided not to wait for the supporting artillery and tanks but to move forward from the very exposed position which his brigade had reached the night before. Italian artillery firing at very short range caused a certain amount of loss, but when at 8.35 a.m. the 1st and 31st Field Regiments and 7th Medium Regiment R.A. came into action the enemy’s fire soon began to slacken.

Thus supported, and helped by the advance of ten tanks of 7th RTR on their left flank, the brigade pressed on. They were much hampered by a dust storm, which greatly reduced the visibility, made inter-communication and co-operation very difficult, and caused the

shortage of water to be felt acutely. Prisoners soon began to pour in. There was some bombing and machine-gunning from the air, and in the centre of the attack the 1st Battalion The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders met stiff opposition about Alam el Dab, but by 1.30 p.m. the brigade had gained its objective and the exits from Sidi Barrani to south and west were barred.

General Beresford-Peirse decided not to relax the pressure, and ordered 16th Infantry Brigade to attack Sidi Barrani before nightfall. He placed the remaining ‘I’ tanks and the Cameron Highlanders under command of Brigadier Lomax, and arranged for 2nd Royal Tank Regiment—cruisers and light tanks—from 4th Armoured Brigade to operate on the left flank. The attack was launched just after 4 p.m., supported by the whole divisional artillery. The heart had now gone out of the enemy and in half an hour the 16th Infantry Brigade had passed through to the east of Sidi Barrani. The remains of 1st and 2nd Libyan Divisions and 4th Blackshirt Division were thus hemmed in between Selby Force and 16th Infantry Brigade, whose casualties during the day amounted to 17 officers and 260 other ranks.

On 10th December 4th Armoured Brigade, having lent its two cruiser regiments to 4th Indian Division and Selby Force, continued to operate with armoured cars across the coast road, while its artillery and light tanks engaged various Italian camps a few miles to the south and east of Buq Buq. Early on 11th December 7th Armoured Brigade (Brigadier H. Russell) moved out to deal with the enemy remaining in the Buq Buq area and made large captures of men and guns. The 4th Armoured Brigade had been ordered overnight to withdraw towards Bir Enba, but a further order to cut off the enemy from the west of Sofafi was unaccountably delayed and arrived too late to be acted on.

A patrol of the Support Group found Rabia empty on the morning of the 11th, the Cirene Division having withdrawn from there and from Sofafi during darkness. They were pursued along the top of the escarpment and contact was made by 2nd Rifle Brigade shortly after noon about ten miles south of Halfaya pass. Except for the escape of the Cirene Division, which was a great disappointment, the 11th was a day of successes. In the morning Selby Force and 6th Royal Tank Regiment (of 4th Armoured Brigade), attacked the 1st Libyan Division, which surrendered by 1 p.m. By nightfall all resistance from the 4th Blackshirt Division had also ceased.

General O’Connor now decided to pursue vigorously with the armoured division; 7th Armoured Brigade along the coast, and 4th Armoured Brigade above the escarpment. This raised an acute

problem of supply which is referred to in the next chapter. It was eased by windfalls of Italian stores, but these were more than offset by the embarrassing flood of prisoners—twenty times the estimated number—to be watered, fed and removed. The attempt to supplement the overland channels of supply by sea was only partially successful; a few lighters which had come ready loaded were able to put ashore some water and rations at Sidi Barrani, but the sea was too rough for a supply ship to discharge and nothing more was possible until the harbour at Sollum became available.

The bad weather also prevented an intended Commando landing and a further shoot from seaward on December 10th. But on the 11th the Terror and the two gunboats bombarded the Sollum area all day and well into the night. Movements of troops and transport crowding along the coastal escape-route offered exceptional targets, which received 220 rounds of 15-inch H.E. and 600 of 6-inch, in addition to the fire of 3-inch guns and pom-poms from very close range.

By the evening of December 12th the only Italians left in Egypt were those in position blocking the immediate approaches to Sollum and a force of some strength in the neighbourhood of Sidi Omar. Passing between these, the 4th Armoured Brigade sent forward a force to cut the road between Tobruk and Bardia, and by nightfall on the 14th the armoured cars of the 11th Hussars had done so; but it soon became impossible to maintain the brigade so far forward and they were ordered instead to capture Sidi Omar, which fell on the 16th. The enemy withdrew from Sollum, Capuzzo, and the other frontier posts, and Bardia became his most forward position in the coastal sector. Farther inland he still held Siwa and Jarabub.

By 11th December General Wavell had decided to go ahead with his plan for sending 4th Indian Division to reinforce General Platt in the Sudan. This decision came as an unwelcome surprise to General O’Connor, who had not been forewarned in order not to add to his preoccupations. To the existing complications on the L. of C. were therefore added the withdrawal of this division from Sidi Barrani and the forward move of 16th Australian Infantry Brigade. This was to be followed as soon as possible by the remainder of the 6th Australian Division, whose commander, Major-General I. G. Mackay, was given the task of capturing Bardia if the enemy decided to defend it. The 16th (British) Infantry Brigade, which was not to accompany 4th Indian Division to the Sudan, would be placed under his command together with additional artillery and the 7th RTR General Wavell directed that there was to be no risk of failure or of heavy casualties; subject to this, the attack was to be made as soon as possible. The 7th Armoured Division was ordered to move out between Bardia and Tobruk directly its maintenance arrangements would allow.

In reviewing the week’s operation General O’Connor gave high praise to the Air Force for having dominated the Italian Air Force to the extent they did. The bomber attacks on the airfields at Derna, El Adem, Tobruk and Gambut had been very effective. The approach march was not interfered with at all, and the attacks made on Western Desert Force during the first two or three days of the battle were not serious. Thereafter the Italian Air Force became more active, doing its best to secure some respite for the disorganized army, and by the 15th it was being a decided nuisance to the troops, though it did surprisingly little damage. Meanwhile, it undertook no counter air operations, and did no bombing of Alexandria or the Delta.

Air Commodore Collishaw’s policy had been to get the utmost out of his limited resources from the outset; during the peak of the first week’s intensive operations some of his fighter pilots were making as many as four sorties a day. Gladiators were used for patrolling over the forward troops, while Hurricanes attacked enemy movements as far afield as fifty miles west of Bardia. The superiority of the Hurricane over the Italian fighter C.R.42 was very marked. Casualties were surprisingly light—four Blenheims and six fighters in the first half of December—but the intense activity had a big effect upon the number of fighters that could be kept serviceable. After December 13th, for instance, No. 3 Squadron R.A.A.F., which was providing close support, had to curtail its activities, and the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief ordered forward another flight of fighters from the defences of Alexandria. At the same time he felt obliged to warn Collishaw not to go on operating at this intensity because the reserves of Gladiators were practically exhausted.

The whole COMPASS plan showed not only great imagination but a firm determination to do the utmost with the resources available. The role of 7th Armoured Division was not, of course, a new one to them; but to 4th Indian Division the operation had several novel features, yet the confidence and enthusiasm of the troops, when they learned what they had to do, could not have been greater. The execution of the plan bore witness to sound training and good leadership, and to a fine fighting spirit in the troops. The tactics of the battle had been designed to suit the ‘I’ tanks, which fully justified the confidence placed in them; one of the many risks inherent in the plan was that, if the opposition had been great enough to cause the attack to be called off after four or five days, a large number of these valuable tanks would have been lost altogether, because there were no vehicles available that could transport or even tow them. More lessons are probably learned from battles

which go wrong; in this battle most thing went right. Even so, the difficulty of exercising control over such a large battlefield was made very clear, and pointed to the need of more reliable wireless communications.

In the three days from 9th to 11th December the Western Desert Force captured no fewer than 38,300 Italian and Libyan prisoners, 237 guns, and 783 light and medium tanks. The total of captured vehicles was never recorded, but more than a thousand were counted. The British casualties were 64 killed, wounded, and missing. This extraordinary result showed how shred had been General Wavell’s estimate of the effect that an early success would have upon Italian morale. Everything possible had been done to ensure that the battle should be given a good start, and great emphasis had been laid upon the importance of taking the enemy by surprise. It is appropriate, therefore, to examine the extent to which surprise was really achieved.

Intelligence summaries issued by the Italian 10th Army show that throughout October and November the enemy was continually receiving reports from Egypt and elsewhere of the movements of British troops and aircraft. Some of these were accurate, some quite ludicrous; the general impression was an exaggerated one of greatly increasing strength in Egypt. From the beginning of November onwards it was assumed that many of the new arrivals would go to Greece, but it was rightly believed that the British could deploy much stronger forces in Egypt or the Sudan, or even both, than they could have done two months earlier. No very clear deduction seems to have been made from this.

Throughout November the Italian Air Force made frequent reports of concentrations of vehicles in the Western Desert, and of an increase in the movement along the lines of communication. Right up to December 5th the conclusions drawn from this were that the troops who had been so long in the forward area were being relieved, or that measures were being taken to meet the expected Italian advance, or both. The chances of a British offensive were not rated very high, though it was thought that some small enterprise might be undertaken for propaganda purposes. IN this connection it was noticed that the British were particularly active in the neighbourhood of the Nibeiwa-Rabia gap, and Marshal Graziani claims to have told the Army Commander, General Berti, on November 18th to give this matter his attention.

On December 4th the general attitude of the British was regarded as unchanged; that is to say, they were continuing to watch all Italian movements very closely. The next day an increase in the air

activity was noted. On the 6th some information, inaccurate in itself, drew attention to a supposed trend of movement westward from the Delta. December 7th passed without any recorded comment, but on the 8th an Italian aircraft reported having seen 400 vehicles at midday at various points about thirty to forty miles south-east of Nibeiwa. (This would have been the aircraft seen by the 4th Indian Division.) Marshal Graziani7 also mentions this air report and says that the 10th Army was immediately notified. He thought the report particularly significant because the interrogation of a prisoner captured on December 5th had led to a verbal warning to 10th Army and 5th Squadra that a strong British attack might be expected in ten days or so. This warning, he states, was given on December 7th. There is no mention of it in the 10th Army’s Intelligence Summary, but General von Rintelen, in an official letter dated 2nd January 1941, refers to a warning being given to Graziani by the Italian Intelligence Department on December 6th that a British attack was imminent.

The fact is that in war it is usually possible to produce some sort of evidence in support of almost every course of action open to the enemy; the art lies in knowing what to make of it all. In this case the Italian Air Force had observed and reported movements and dispositions with fair accuracy—indeed, it was often intended by the British that they should. The important point was that these reports were consistent with what the 10th Army were convinced was happening. They themselves were very much occupied with their own preparations for renewing the advance, and were only too ready to interpret the air reports as indicating that the British were actively improving their defensive arrangements. The British attempt at strategic deception was therefore successful.

But this did not alter the fact that the Italians had a very large force stationed east of the frontier. What really mattered was how competently the higher commanders would handle the defensive battle, and how well the troops would fight. In both these vital matters the Italians must be judged to have failed. They handicapped themselves from the start by failing to act on the air report of 8th December; no attack was made upon the British concentration and nothing was even done to ensure that it was kept under observation. The commanders in the forward area made no special efforts during the night to gain any information for themselves, or to increase their vigilance. The result was that at the first objective, Nibeiwa, tactical surprise was complete: the assault came at an unexpected moment from an unexpected direction, and was led by a type of tank whose presence was entirely unsuspected.

The Italians in the Western Desert suffered, of course, from a great inferiority in armoured units. Neither of the armoured divisions had been made available for them; the Centauro had gone to the mountainous Albanian front and the Ariete had stayed in Italy. There was an armoured brigade near Tobruk, too far off to be of any use. Such tanks as there were in the forward area were not used on any clear plan for making a decisive contribution to the battle; thirty-five or so, for instance, were locked up in Nibeiwa camp and lost there.

In short, this three-day battle led to the conclusions that the enemy’s higher commanders had little or no idea of fighting a battle in desert conditions, and that on the whole the junior leaders and men were apt to lose heart very quickly. It remained to be seen whether the Italian troops, without the Libyans, would make a better showing in the defence of an important centre, like Bardia, for which there had been ample time to construct strong permanent defences.

The Prime Minister was quick to telegraph his appreciation to General Wavell. ‘The Army of the Nile has rendered glorious service to the Empire and to our cause and rewards are already being reaped by us in every quarter. . . . Pray convey my compliments and congratulations to Longmore upon his magnificent handling of the Royal Air Force and fine co-operation with the Army. . . .’ He added, as his thoughts dwelt on even better things to come, ‘It looks as if these people were corn ripe for the sickle’. General Wavell made a characteristic reply, giving full credit to his subordinates and to the other Services, and added that, while he and his colleagues were fully aware of the need to exploit their success, it must be realized that Bardia possessed strong permanent defences and its capture might prove to be beyond their present resources.

Blank page