Chapter 9: The Lull in the Desert

February—May 1942

See Map 2

THE two previous chapters will have left no doubts as to the seriousness of the loss of the airfields in Western Cyrenaica from the point of view of the replenishment of Malta. It was only from Malta that the sea-traffic to North Africa could be attacked to good purpose, so the longer Malta was without adequately supplied striking forces the stronger would General Rommel become. It was only to be expected that General Auchinleck would be pressed to recapture the Western Cyrenaican airfields as soon as possible. Cause and effect were thus chasing each other in a circle.

The retreat of the 8th Army in January and February had stopped about thirty miles west of Tobruk. The line taken up ran inland from Gazala, where the coastal road passed through a narrow gap which was easily blocked. While the position had no important tactical features it did cover the tracks running east towards Acroma, as well as the Trigh Capuzzo and Trigh el Abd farther to the south. At the beginning of February the line was only very weakly held, but General Auchinleck ordered it to be made as strong as possible to preserve Tobruk as the base for a new offensive. In the light of subsequent events it is of interest to note that General Ritchie was told that if he was compelled to withdraw again he was not to allow his forces to be invested in Tobruk. He was to make every effort to prevent Tobruk being lost to the enemy, ‘but it is not my intention,’ wrote General Auchinleck, ‘to continue to hold it once the enemy is in a position to invest it effectively. Should this appear inevitable, the place will be evacuated and the maximum amount of destruction carried out in it, so as to make it useless to the enemy as a supply base. In this eventuality the enemy’s advance will be stopped on the general line Sollum–Fort Maddalena–Jarabub’—in other words, on the line of the Egyptian frontier. This order was the outcome of a decision taken by the Commanders-in-Chief on 4th February. They knew well the advantages the enemy would draw from gaining possession of Tobruk, but General Auchinleck was unwilling to lock up a garrison of at least one division, having regard to his strength and his other possible commitments. (The Persia–Iraq–Syria front was always in his thoughts.)

Admiral Cunningham, remembering how much it had cost in ships to maintain the garrison in 1941, strongly agreed. Air Marshal Drummond, representing the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief, believed that we might well be unable to hold Tobruk, particularly as it would be impossible to provide it with fighter cover.

In addition to completing his defensive dispositions as soon as possible, General Ritchie was to organize a striking force with which to resume the offensive. He was also to study the possibility of regaining the airfields in the area Derna–Mechili–Martuba, or alternatively of preventing their use by the enemy—both these tasks without prejudice to the main one of defeating the enemy and reoccupying Cyrenaica. He might expect to have available three armoured divisions, two armoured brigade groups, one army tank brigade, and three infantry divisions. Most of these would be equipped and trained by the middle of April.

The Commanders-in-Chief communicated their intentions to the Chiefs of Staff on 7th February, but made no estimate of when the offensive would begin. The date, they said, would depend on the speed with which both sides would build up their armoured forces. They stated as a principle that to have a reasonable chance of beating the enemy on ground of his choosing we required a numerical superiority over the German tanks of 3 to 2 ‘owing to our inferiority in tank performance’. This principle, which was put forward by General Auchinleck, took account of many factors other than mere numbers. Leadership and training have often been referred to, and will be referred to again; there was also the time taken in overhauling and modifying newly arrived tanks, and the long time taken by a casualty to rejoin after being sent off to a base workshop—of which there were too few. In this connexion it should be mentioned that a Ministerial enquiry in England showed that reports from the Middle East had not exaggerated the defects of the Crusader tank in desert conditions. As for the Ordnance Workshops being too few, circumstances had been obstinately adverse. Of several that were ready to embark in October 1941 only two were on the sea by March 1942; the remainder had been shut out of two convoys mainly by drafts needed to replace battle casualties, and from a third because that convoy had suddenly been wanted for the Far East.

The Commanders-in-Chief’s telegram of 7th February started a debate between London and Cairo which went on until May. The question was when could General Auchinleck start an offensive in the Western Desert. The War Cabinet and Chiefs of Staff had weighty reasons for wishing it to open very soon. General Auchinleck, supported by the other Commanders-in-Chief and by the Minister of State, was unwilling to start until he had the number of tanks that he believed essential for a reasonable hope of success: the object, as before, being

to occupy Cyrenaica and press on into Tripolitania. Thus a great deal turned on the relative strength in tanks.

It is not necessary to follow in detail the rather tedious arguments about the British tanks which were put forward during the following three months. The whole episode recalls the dispute about aircraft strengths before CRUSADER and shows what misunderstandings can arise and how misleading figures—especially telegraphed figures—can be. Broadly, London was primarily interested in the numbers of tanks despatched from the United Kingdom to the Middle East, while Cairo was concerned with tanks in fighting trim—a very different thing. Other disputes occurred about whether ‘I’ tanks were to be included in the calculations or not, and whether only tanks with units should count towards the three to two superiority or those in reserve as well.

The calculations of the enemy’s future tank strength led to further argument. It was agreed that the Axis could spare no fresh armoured formations for Africa, except perhaps the Italian Littorio Division. It was also agreed that they would try to keep up the strength of the formations already in Africa, and had the tanks to do so. There was a difference of opinion as to what the ‘establishments’ of German and Italian armoured regiments were, and it will perhaps cause no surprise that Cairo’s estimate was higher in each case than London’s. Finally, London thought that the Middle East, although so well aware of the problems connected with tank replacements, tended to minimize unduly the enemy’s difficulties.

The Middle East had other anxieties. On 17th February came the order to send the 70th Division to the Far East, and a warning that the 9th Australian Division would probably be removed from the Middle East as well.1 On the same day the CIGS, General Sir Alan Brooke, warned General Auchinleck that one division might have to return to India from Iraq, and that not more than one division would be sent to the Middle East from England during the next six months. ‘I realize,’ he wrote, ‘that your plans for regaining Cyrenaica may have to be abandoned in favour of the defence of the Egyptian frontier and that you will be on little more than an internal security basis on your northern front ... It is a question of reinforcing where we are immediately threatened ...’

On 26th February the Prime Minister telegraphed to General Auchinleck:

‘I have not troubled you much in these difficult days, but I must now ask what are your intentions. According to our figures you have substantial superiority in the air, in armour, and in other forces over the enemy. There seems to be danger that he may gain reinforcements as fast as or even faster than you.

The supply of Malta is causing us increasing anxiety, and anyone can see the magnitude of our disasters in the Far East. Pray let me hear from you. All good wishes.’

General Auchinleck replied the next day with a long examination of all the factors which ended with a very unpalatable conclusion. This was that to launch a major offensive before the 1st June would be to risk defeat in detail and possibly endanger the safety of Egypt.

The very same day the Chiefs of Staff signalled to the Commanders-in-Chief that Malta was of such importance that the most drastic steps were justifiable to sustain it.2

‘We are unable to supply Malta from the west. Your chances of doing so from the east depend on an advance in Cyrenaica. The situation in Malta will be dangerous by early May, if no convoys have got through. ... We appreciate that the timing of another offensive will depend on building up adequate tank superiority, and that its launching may necessitate taking considerable risks in other parts of Mideast Command. Nevertheless we feel that we must aim to be so placed in Cyrenaica by April dark period that we can pass substantial convoy to Malta.’

It is appropriate to recall how black at this moment seemed the immediate circumstances of the war, even if the entry of the United States made victory certain in the long run. In three weeks most of the British winter gains in Cyrenaica had been blown away. On 15th February had occurred the disaster of the fall of Singapore, quickly followed by the Allied collapse in the Netherlands East Indies. Then had come the Japanese invasion of Burma, and the prospect of losing that country was all too clear. Nearer home the escape through the Straits of Dover of the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Prinz Eugen had aroused bewilderment and indignation. The political situation was somewhat uneasy in spite of the overwhelming Vote of Confidence which the Prime Minister had obtained at the end of January, and public opinion was depressed and querulous.

The Defence Committee was deeply dissatisfied with General Auchinleck’s conclusion, all the more so because the enemy in the Middle East seemed able to rebound after his reverses and we could not. Accordingly on 3rd March the Chiefs of Staff again pressed upon the Commanders-in-Chief the vital need of sustaining Malta by a convoy before May. In their opinion General Auchinleck’s review was heavily biased in favour of the enemy and took no account of air power, in which we had temporarily the advantage in the desert.

They considered that an attempt to drive the enemy out of Cyrenaica in the next few weeks was imperative for the safety of Malta and gave the only hope of fighting a battle while the enemy was still comparatively weak. Looking ahead, they pointed to the danger to the Levant–Caspian front if the enemy were allowed to build up in Africa a force which could pin down the Middle East’s strength, already lessened by the needs of the Far East, to the defence of Egypt’s western flank. Moreover we could not stand idle while the Russians were straining every nerve to give the enemy no rest. ‘If our view of the situation is correct,’ they wrote, ‘you must either grasp the opportunity which is held out in the immediate future or else we must face the loss of Malta and a precarious defensive.’

To this the Commanders-in-Chief replied on 5th March agreeing that from the naval and air points of view there was nothing to gain and much to lose by waiting. But the battle would be primarily a land one, and the Army was not ready for it. A premature offensive might result in the piecemeal destruction of the new armoured forces now being built up, and would endanger the security of Egypt. The issue was therefore whether in the effort to save Malta they were to jeopardize our whole position in the Middle East.

This view angered the Prime Minister and troubled the Chiefs of Staff, and on 8th March Mr. Churchill asked General Auchinleck to come home for consultation. The General bluntly refused, saying that he felt unable to hand over his problems to anyone else even for ten days. He had given all the information there was about the tanks, and his coming home would not make it any more possible to stage an earlier offensive. Mr. Churchill saw in this refusal a manoeuvre to escape pressure and had it in mind to remove General Auchinleck.

However he did not do so, and instead asked Sir Stafford Cripps, the Lord Privy Seal, to break a journey he was making to India in order to give General Auchinleck the War Cabinet’s views. Sir Stafford would be joined by the Vice-CIGS, Lieut.-General A. E. Nye, who knew the opinions of the Chiefs of Staff.

On 21st March Sir Stafford Cripps reported the outcome of his discussions. He was convinced that we were not strong enough in armour or in the air to make it possible for an offensive to be begun with reasonable hope of success before mid-May. Sir Stafford included a good deal of detail in his report, which was separately elaborated by General Nye, who had brought with him from the Prime Minister a formidable list of questions enquiring into everything from the build-up of the armoured forces to the average ages of their commanders. General Nye, a very able and experienced Staff Officer, summarized the mass of facts which had led General Auchinleck to his conclusions. He also called attention to a factor which had frequently tended to slip out of sight—the need for proper training.

These reports were exceedingly unpleasing to the Prime Minister, who believed that his emissaries had failed to deal properly with the Middle East’s arguments. Nevertheless the Defence Committee reluctantly accepted mid-May as the date for the offensive, only to be told by the Commanders-in-Chief on 2nd April that they could not bind themselves to begin even then, in spite of the very obvious and urgent need to do so as soon as possible.

On 9th April the Chiefs of Staff informed the Commanders-in-Chief of the Japanese threat to Ceylon, and the consequent danger to the Middle East’s communications with the United Kingdom and to the oil supplies from Abadan. Ceylon must be given an air striking force, and at once. The Commanders-in-Chief were asked to send 30 Hurricane Hs, 20 Blenheim IVs and a squadron of Beaufort torpedo-bombers. The deeper implications of this telegram disturbed the Commanders-in-Chief even more than the loss of the aircraft, and they asked for some more information. On 23rd April the Chiefs of Staff replied with a stark review which led to the conclusion that if the Japanese pressed boldly and quickly westwards there would be a grave danger to India, and that the eventual security of the Middle East and of its essential supply lines would be threatened. This seemed to General Auchinleck to demand a complete reconsideration of Middle Eastern strategy. He told his colleagues that, in a general situation as desperate as the Chiefs of Staff had painted it, it would be taking a tremendous risk to launch an offensive in Libya; all their efforts should rather be applied to strengthening their defences and sparing everything they could for India in order to check the Japanese before it was too late.

Accordingly on 3rd May a proposal amplifying this conclusion was made to London, where, however, a very different view was held. In fact the wish to see the Middle East take the offensive had grown if anything stronger as things grew worse, in particular the situation at Malta. It may be recalled that on 23rd April the Chiefs of Staff had had to announce to Malta that she would get no convoy during May either from east or west.3 The Prime Minister now explained that the Chiefs of Staff’s review in question had been prepared on the British principle of facing the worst; when expounded to the House of Commons in Secret Session it had had a most exhilarating and heartening effect. He went on to show how the situation had now improved, and outlined the steps being taken to strengthen India, Ceylon, and the Eastern Fleet. He was grateful for the offer to denude the Middle East still further for the sake of the Indian danger, but the greatest help that the Middle East could give to the whole war at this juncture would be to engage and defeat the enemy in the Western Desert.

The reply to this appeal was discouraging in the extreme, for the

Commanders-in-Chief signalled on 6th May that the latest comparison of tank strengths made it unjustifiable to attack before mid-June. ‘To start earlier would incur risk of only partial success and tank losses, and might in the worst case lead to a serious reverse, the consequences of which in present circumstances are likely, in our opinion, to be extremely dangerous.’ With this the Chiefs of Staff and the War Cabinet could not agree, and on 8th May the Prime Minister telegraphed their considered views, which were that the loss of Malta would be a disaster of the first magnitude to the British Empire and would probably be fatal in the long run to the defence of the Nile valley. ‘We are agreed that in spite of the risks you mention you would be right to attack the enemy and fight a major battle, if possible during May, and the sooner the better. We are prepared to take full responsibility for these general directions leaving you the necessary latitude for their execution.’ He went on to point out that the enemy might himself be intending to attack early in June.

But the Middle East Defence Committee felt unable as yet to accept these directions. They replied on 9th May putting forward the view that the fall of Malta would not necessarily be fatal to the security of Egypt for a very long time, if at all, provided our supply lines through the Indian Ocean remained uninterrupted. In its present almost completely neutralized state Malta was having very little influence on the enemy’s maintenance in North Africa. It was, however, containing large air forces and if the enemy continued to use these for attacking the island it was doubtful whether the recapture of Cyrenaica would restore Malta’s offensive power. Moreover, they believed that it would take at least two months to get a firm grip on Cyrenaica. And then came their deepest misgiving:

‘We feel that to launch an offensive with inadequate armoured forces may very well result in the almost complete destruction of those troops, in view of our experience in the last Cyrenaican campaign. We cannot hope to hold the defensive positions we have prepared covering Egypt, however strong we may be in infantry, against a serious enemy offensive unless we can dispose of a reasonably strong armoured force in reserve, which we should not then have. This also was proved last December, and will always be so in terrain such as the Western Desert, where the southern flank of any defensive position west of the El Alamein–Qattara depression must be open to attack and encirclement. ... We still feel that the risk to Egypt incurred by the piecemeal destruction of our armoured forces which may result from a premature offensive may be more serious and more immediate than that involved in the possible loss of Malta, serious though this would be.’

They agreed that there were signs that the enemy might be going to attack our strong positions at Gazala; this might result in his armoured forces becoming so weakened that our own would have a chance of destroying them.

For a moment the Chiefs of Staff were inclined to agree to postpone the offensive until mid-June, but they came to the conclusion that in the Middle East the danger to Egypt was being over-estimated. The War Cabinet agreed, and on 10th May the Prime Minister brought matters to a head with a telegram in the name of the War Cabinet, the Defence Committee, and the Chiefs of Staff:

‘We are determined that Malta shall not be allowed to fall without a battle being fought by your whole army for its retention. The starving out of this fortress would involve the surrender of over 30,000 men—Army and Air Force—together with several hundred guns. Its possession would give the enemy a clear and sure bridge to Africa with all the consequences flowing from that. Its loss would sever the air route upon which both you and India must depend for a substantial part of your aircraft reinforcements. Besides this, it would compromise any offensive against Italy and future plans such as ACROBAT and GYMNAST.4 Compared with the certainty of these disasters, we consider the risks you have set out to the safety of Egypt are definitely less, and we accept them.’

He repeated that General Auchinleck would be right to fight a major battle, if possible during May, and added that the very latest date for engaging the enemy which they could approve would be one which provided a distraction in time to help the passage of the June dark-period convoy to Malta.

This telegram in fact gave General Auchinleck the choice between complying and resigning. On 19th May he reported to the Prime Minister that he would carry out his instructions, but asked for confirmation that the primary object was to destroy the enemy’s forces in Cyrenaica and ultimately to drive him from Libya, and not solely to stage a distraction to help the Malta convoy. There were now strong signs that the enemy was about to attack; if he did not, General Ritchie would be told to launch his offensive to fit in with the object of providing the greatest possible help to the Malta convoy. General Auchinleck added that owing to the narrowness of our superiority, both on land and in the air, the success of a major offensive was not in any way certain and in any event was not likely to be rapid or spectacular.

The Prime Minister replied that General Auchinleck’s interpretation of his instructions was quite correct. The time had come for a trial

of strength in Cyrenaica. He realized, of course, that success could not be guaranteed: there were no safe battles. His confidence in the Army would be even greater than it was if General Auchinleck would go forward and take direct command. General Auchinleck replied that he had considered this point most carefully, but had decided that he must not become immersed in tactical problems in Libya. He might be faced with having to decide whether to continue to reinforce the 8th Army or to build up the northern front which he was now weakening in order to give General Ritchie all the help possible. Only at the hub could he keep a right sense of proportion, and his place was there.

The outcome of all this was that the enemy attacked first. It will be seen that he offered the British a chance of winning a really great victory, but they did not succeed in taking it. In conclusion it is of interest to note that when, in the following August, General Auchinleck was replaced by General Alexander, a separate Command was created for Persia and Iraq, because Mr. Churchill doubted whether the disasters in the Western Desert would have occurred if General Auchinleck ‘had not been distracted by the divergent considerations of a too widely extended front’.

During the lull in the Desert from February to May the Royal Air Force had a great deal to do in the way of reorganization and preparation for the next active phase on land, while continuing all the time to harass the enemy as much as possible. In the course of the CRUSADER campaign the Desert Air Force had been much weakened, the fighters in particular having suffered wastage much greater than the flow of replacements, in spite of the remarkable achievements of the salvage and repair units. The Hurricane Is had been outclassed, the supply of Tomahawks had dried up, few Hurricane IIs were arriving, and there had been only a trickle of Kittyhawks. As for bombers, the supply of Marylands was at an end, the Blenheims’ engines were suffering terribly from the dust, the new Bostons were also having engine troubles, and the few Baltimores were having to be modified. Apart from these local worries there had been calls from time to time to help the Far East—and there might be more. Looking further ahead there was always the possibility of having to send substantial air forces to the Northern Front.

In July 1941 the Air Ministry had set a target for the Middle East Air Force of 62+ squadrons, to be reached in March 1942.5 By the end of January there were 57 complete squadrons (including 5 in Malta) exclusive of various air transport, communication, photographic and survey reconnaissance, and Fleet Air Arm units. Another thirteen squadrons were forming or about to form. Thus, in spite of withdrawals

and diversions to the Far East, the intended figure was well within reach. In the meantime, however, the Air Ministry had reviewed Air Marshal Tedder’s requirements, and in December 1941 a new target was set at 85½ squadrons by August 1942. In early March further additions were made to the figure aimed at, but by increasing the number of aircraft in every light bomber and tactical reconnaissance squadron it was possible to reduce the figure to 80. Of these, 3 were to be heavy bomber squadrons, and 35 short-range fighter squadrons-15 of which were to have Spitfires.

The introduction of heavy bombers into the Middle East programme deserves a word of explanation. The arrival of the first Liberator in December 1941 and its experimental use for bombing Tripoli has already been referred to.6 In April 1942 the serious situation at Malta led the Commanders-in-Chief to ask for heavy bombers to deal with the Sicilian airfields. In May, by a stroke of good fortune, a detachment of Liberators arrived on its way to the Far East, under orders to attack the Ploesti oilfields before moving on.7 The Commanders-in-Chief seized their opportunity, and at their urgent request these Liberators were retained and others bound for India were diverted to the Middle East, on the understanding that they were not to be used for local operations nor in a manner unsuited to their type. In addition two squadrons of Halifaxes were to be sent from the United Kingdom. The transfer of all these heavy bombers to the Middle East was in fact an exercise in strategic mobility, the intention being to switch them from one theatre to another as required.

The needs of the Middle East were not in dispute as far as aircraft were concerned, but the question of providing aircrews was hotly argued. The unsatisfactory state of operational training in the Middle East in 1941 was referred to in Volume II; in the spring of 1942 it had become worse. Reinforcements from the United Kingdom were as necessary as ever, but the Home Commands were now equally hard pressed. Bomber OTUs especially were strained to the limit; Bomber Command had been obliged to adopt a ‘one pilot’ policy for its heavy bombers, and the Middle East was eventually obliged to conform. Air Marshal Tedder’s repeated requests for aircrew reinforcements came under heavy fire from the Air Ministry, but during these months it was mainly from the United Kingdom that the aircrews were sent.

While these plans were going forward for forming new squadrons and for building up aircrews and aircraft, steps were being taken to eradicate certain weaknesses in the Desert Air Force before it should again be called upon to support a major land offensive. One of the most important of these steps was the creation of a fighter group headquarters. Hitherto the mobile fighter force had consisted of two wings,

both directly under Air Headquarters. The new group was formed mainly by absorbing Nos. 258 and 262 Wing Headquarters, and became No. 211 Group, which had previously been disbanded when its area of responsibility in Cyrenaica had been overrun by the enemy. The first Commanding Officer was Group Captain K. B. B. Cross, who had been the senior Fighter Wing Commander during CRUSADER. The new group was designed to control, for operational purposes only, three mobile fighter wings of four to six squadrons each. A central group operations centre was formed—in duplicate in order to be able to ‘leap-frog’. It absorbed the operations centres of Nos. 258 and 262 Wing Headquarters, which were themselves replaced by two new Wing Headquarters (Nos. 239 and 243), and the already existing No. 233 was brought forward to complete the group. For administration and maintenance the three wings were to be responsible to Air Headquarters; for all air operations and for the control of early warning arrangements and airfield defence they would be commanded by the new group.

Great efforts were made to raise the standard of air firing among the fighter pilots, and shadow firing took the place of the current method of firing at a towed drogue or sleeve.8 Navigation and ground-attack were strenuously practised. New tactics were developed for dealing with the Me.109F. The radar coverage was now so much better—it could, for example, deal with low-flying aircraft—and the wireless observer screen so much more complete, that the employment of wing formations on offensive patrols could be dropped in favour of using flights of four to six aircraft. It was hoped that by this means the Me.109Fs would find less to pick at.

For the day-bombers the main item of training was bombing practice, particularly with the new Boston aircraft. The usual height was between eight and ten thousand feet, with occasional high-level practices at fifteen thousand; experiments were also made in bombing from shallow dives. The day-bombers were now based at Bir el Baheira, only a few miles from the main fighter base at Gambut, and this was greatly to the advantage of both bomber and fighter pilots since one of the most important tactical changes at this time was in the system of giving fighter escorts to the day-bombers. The enemy’s growing fighter defence and the greater speed of the Boston compared with the Maryland were two of the reasons for the change. One fighter wing now specialized in this duty; radio communication between fighters and bombers was developed; and procedures were agreed and adopted for the bombers as regards formation flying, climbing and cruising speeds, and avoiding flying ‘down sun’.

In view of the shortage of day-bombers it was decided to aim at equipping every single-engined fighter to carry one or more bombs.

This did not affect its performance as a fighter once its bombs had been released, and as a fighter-bomber it was capable of being bombed-up and put into the air much more quickly than a bomber. It also used much less fuel, which was an important point when supply became difficult, particularly in a rapid advance. By the end of May one Hurricane and three Kittyhawk squadrons had been so equipped, and others, both Hurricane and Kittyhawk, were gradually fitted up during the summer. During the time of the lull the weapon used was the 250-lb. bomb, though Kittyhawks which were delivered later came equipped to carry one bomb of 500-lb.9

In the realm of army/air co-operation there were not many developments. The transfer of the Air Support Control from the level of Corps headquarters to that of Army/Air headquarters enabled requests for air support received through the tentacles to be presented quickly and simultaneously to the Army and Air Force Commanders, or their nominees. A system of land markings was introduced to help pilots to fix their position in featureless surroundings; by day bold letters of the alphabet were used, and by night large Vs of lighted petrol in cans. In an attempt to solve the vexed problem of the bomb-line arrangements were made to pass hourly forecasts of the position of the most advanced British troops to Air Support Control, the forecasts being made two hours ahead. The difficult question of recognition from the air continued to be a subject for argument between the two Services, and the suggestion that the RAF roundel should be painted on all vehicles had not been adopted before the next phase of active land operations began.

The retreat from Western Cyrenaica made it necessary to construct a number of new operational landing-grounds. The experience of the squadrons of the Desert Air Force had made them distinctly anxious about the protection that the army could give to their landing-grounds during a battle. There had been no permanent allotment of troops to this duty; such troops as were near were apt to become involved in some other task and the landing-grounds were frequently unprotected.

Much the same applied to the anti-aircraft defence, for the army tended to regard the guns as available for other tasks. It is of interest to note that the air defence of the back areas had been the subject of a special enquiry by an inter-Service mission from England under Air Vice-Marshal D. C. S. Evill in December 1941. Shortage of equipment, vehicles, aircraft, and trained men prevented many of its recommendations being put into effect by the spring of 1942, but the principle of unified air defence—including anti-aircraft defence—had been

accepted. In the forward area the same principle was adopted, but not yet.

The measures which have been outlined for raising the operational efficiency of the Desert Air Force were accompanied by a drive for better administration. Ground organization in particular received attention, especially as regards the speeding up of rearming and re-fuelling—two very important aspects of intensive air operations. Under the vigilant eye of Air Vice-Marshal Coningham the Desert Air Force was thus preparing itself for the next intensive phase. But a lull on land does not necessarily mean a lull in the air, as will be seen from the summary of operations which follows.

When, early in February, the 8th Army’s retreat was halted at Gazala, Air Marshal Tedder and Air Vice-Marshal Coningham found themselves faced with much the same problems as had arisen after the failure of BATTLEAXE. Then, as now, the Army had needed a long spell of reorganization and preparation, while to the Air Force fell the duties of striking at the enemy’s supply lines, attacking his air forces in Cyrenaica, and harassing his troops. Reconnaissance of all kinds—strategical, tactical and photographic—was in great demand, and there were in addition numerous defensive commitments in both the forward and the rear areas, as well as the protection of coastal shipping, especially on the sea route to Tobruk.

There was one important difference from the autumn of 1941; the heavy air attacks on Malta were causing her offensive contribution to wane until it was to become almost non-existent. In the fifteen weeks of the lull in the Desert the Wellingtons from Malta could only fly about sixty sorties against Tripoli, though they also attacked Palermo and sank the Cuma of 6,652 tons, the Securitas of 5,366 tons, and sank or damaged several other vessels.10 The only aircraft from Egypt which could now reach Tripoli were the Liberators, but it was not until May that any number of these arrived. Consequently the attack on enemy ports amounted really to the attack of Benghazi, an off-loading place of great importance to the enemy because its use cut out the long road haul from Tripoli.

On Benghazi, then, the weight of the Wellingtons was mainly concentrated. The first attack was made early in February, and in three months the total day and night bomber sorties against the port and its surroundings, including the laying of mines off the harbour entrance, amounted to 741, or an average of 8 sorties every 24 hours. Some of the attacks were heavy; for example on 8th May twenty-eight aircraft bombed the port and ships in the offing. In May, when the enemy showed signs of preparing an offensive on land, the night

attacks were supplemented by the Bostons and long-range Kittyhawks by day. It appears that ships usually entered harbour at dawn and unloaded during daylight; photographs gave an impression of much damage, but, judging from the enemy’s statements of cargo unloaded, the interruption was not so serious as was hoped. The capacity of the port steadily rose, though without these attacks it would presumably have risen even faster.

Against the enemy’s airfields only a much weakened force of day-bombers was at first available, for reasons already given. But the effort soon grew, and the developments in tactics and equipment brought good results. As a rule the Wellingtons went for the important airfields at Martuba, and the day-bombers attacked Derna, Berka, Benina, Barce and Tmimi. Kittyhawk fighter-bombers also took part. An example of good fighter co-operation was on 14th March, when during an attack on Martuba West the escorting fighters successfully beat off determined attacks by German and Italian fighters without damage to a single Boston. Unescorted raids, however, occasioned some losses, as for instance when two out of three Bostons did not return from attacking Barce on 21st March. A notable success was scored on 15th March when four Italian fighters were destroyed and six others damaged; a German communications aircraft was also destroyed. At about this time the Germans gave an order to their fighter units to counter such attacks very aggressively and to strike at RAF airfields ‘to regain air supremacy’.

Another commitment for the day-bombers during the lull was the attack of troops, transport and supply lines in the forward area, though the force available did not allow of more than about a hundred sorties. A certain amount of experience, however, was gained by the Beaufighters and by the Hurricane and Kittyhawk fighters and fighter-bombers in the attack of ground targets. Not the least successful were the night-flying Hurricanes of No. 73 Squadron, which had just been put through a special course. Flying on free-lance patrols, either singly or in pairs, they attacked camps and vehicles, reconnoitred airfields, and intercepted returning night-flying aircraft.

During the first half of the lull No. 208 Squadron continued to provide tactical reconnaissance of the enemy’s troop positions and of movement around Derna, Martuba, Tmimi, Mechili and Tengeder. At the end of CRUSADER the tactical reconnaissance squadrons were still equipped with Hurricane Is, and it had been decided to replace one flight in each squadron with Tomahawks. (The greater speed of this aircraft was to prove a big factor in keeping up the morale of the pilots engaged on this exacting work.) In mid-March No. 40 Squadron SAAF, which had already received a few Tomahawks, took over from No. 208, which was then withdrawn to rest and refit. Various tactical methods were tried to counter the growing opposition by the

enemy’s fighters and to ensure the important work of reconnaissance being successfully accomplished. One way was for the Hurricane I to be accompanied by a Tomahawk as ‘weaver’; another was to send it as a part of a fighter formation; a third method depended upon the greatly improved radar coverage, which made it possible for the tactical reconnaissance aircraft to work independently, the pilot being informed by the fighter controller of the approach or absence of any hostile aircraft in the area of his reconnaissance.11

The fighter force was based first at Gambut and El Adem, with Gazala as a forward refuelling field. The last two received much attention from German fighter-bombers, and Me.109s equipped in this way met with considerable success. (The Italians also claimed to have attacked British airfields at Gambut by moonlight with CR42s carrying glider bombs.) The prevalence of dust at El Adem limited the use of this airfield and the fighters became concentrated at Gambut and Gasr el Arid. The improved warning system allowed time for interception over the forward area even from these bases, while communications were greatly simplified and the anti-aircraft defence much strengthened.

During most of the lull the fighters were mainly committed to defensive tasks such as escorting the day-bombers and aircraft on tactical reconnaissance, defending Tobruk, and protecting the shipping route from Alexandria as well as road and rail communications and airfields. During April and May there was a renewal of the enemy’s ‘jumping’ tactics by Me.109s flying out of the sun; on 20th April, for instance, six to eight of them pounced on four Hurricanes near Tobruk, shot down two and damaged the other two so badly that they had to land. On another occasion, however, the British scored a similar success when six Macchi 200s were shot down over Tobruk.

The passage of the convoy from Alexandria to Malta in March was the occasion for a special effort to keep the enemy’s air forces occupied. This led to many encounters; for example, the fighters, supporting raids by the army, destroyed three Me.109s and damaged two others for the loss of five Kittyhawks and one Hurricane.12 The Wellingtons joined in the same operation by attacking the naval base at Piraeus, the submarine base at Salamis, three airfields near Athens, two on Rhodes, and four on Crete.

Even after the attacks from Malta upon the sea route to North Africa had dwindled almost to nothing, the Germans made great use of their numerous transport aircraft to carry men and stores from Crete to Cyrenaica. On 12th May eight long-range Kittyhawks and

four Beaufighters intercepted twenty south-bound Ju.52s escorted by three Me.110s fifty miles off Derna; they shot down eight and damaged another, and destroyed a Me.110, all for the loss of one Beaufighter. Thereafter the Germans used Me.109s fitted with extra fuel tanks to escort their transport aircraft.

The principal targets for the enemy at this time were Tobruk, the British desert railway, the airfields—especially Fuka and Gambut—and troops in the forward area. During March the Germans had been concentrating their air forces in Sicily for neutralizing Malta, and for this purpose they withdrew units from Greece and Crete, and left Fliegerführer Afrika to make do with what he had.13 During April there were a few attacks on Alexandria and towards the end of the month on the Suez Canal also—the first since February. The night-fighters of No. 89 Squadron took heavy toll of the enemy and it is probable that they shot down most, if not all, of the 4 Heinkels and 7 Ju.88s lost during those few weeks. In May there were signs that General Rommel was preparing for something. German fighter activity increased, though the dive-bombers and fighter-bombers were unusually quiet, as if gathering their strength. Actually their numbers, as we have seen, were being increased, because Malta had been neutralized and some of the air forces in Sicily were being sent back to Greece and Crete, and others to North Africa. In the third week of May there was an increase in reconnaissance flights and dive-bombing. The British lines of communication, especially the railheads, were frequently attacked, and attempts by RAF reconnaissance aircraft to find out what was going on met with increasing opposition. By now Nos. 40 SAAF and 208 Squadrons were both at work, the former with the 13th Corps and the latter with the 30th, operating from El Adem and Bir el Gubi respectively.

When it began to look as if an offensive might be expected during the moonlight period at the end of May, daily reconnaissance of the whole of the enemy’s area was intensified and fighters were drawn upon to swell the reconnaissance resources. From 21st May the attack of ‘strategic’ targets (such as Benghazi) was lifted, and the Wellingtons of No. 205 Group, together with the light bombers, fighter-bombers and night-flying Hurricanes of the Desert Air Force set about the task of disorganizing and weakening the Axis air forces in order to offset, from the start, the superiority of the German fighters and the greater numerical strength of the enemy in the air. First on the list came the single-engined fighter bases at Martuba and Tmimi, and the twin-engined fighter and dive-bomber base at Derna. By 26th May over 160 tons of bombs were dropped on these airfields—mostly on Martuba. Photographs taken by day and night indicated that there

had been considerable destruction, but German reports disclose less positive results. A feature of the night attacks at this time was the successful use of Fleet Air Arm Albacores, with their wide field of view and their ample flare-carrying capacity, as ‘pathfinders’ for the Wellingtons.

So passed the lull. For the Air Force it had been a difficult period, the urgent demands of operations on the one hand conflicting with the need of rest, refitting and training on the other. New problems had cropped up, as they always do; the four 20-mm. cannons of the Hurricane IICs were being affected by dust, the Allison engine in the Kittyhawk was giving trouble, and this aircraft, a difficult one to handle, was taking the Hurricane pilots longer than expected to master. In spite of all this, during the fifteen weeks from 7th February to 25th May the Middle East air force (including Malta’s bombers, but excluding anti-shipping operations) flew nearly 14,000 sorties, which is an average of 130 sorties a day. In the Desert during this time 89 German and over 60 Italian aircraft were destroyed by all causes. The British losses, amounting to nearly 300, were relatively high, and were the price paid for an aggressive air policy and a fighter force composed for the most part of obsolescent aircraft.

The experience of the winter fighting had led General Auchinleck to decide upon two important changes in the organization of the army. It was not only the enemy who had noticed that the British armour, artillery and infantry had often been unsuccessful in concerting their action on the battlefield. General Auchinleck accordingly made up his mind ‘to associate the three arms more closely at all times and in all places’. He thought that the British type of armoured division would be better balanced if it had less armour and more infantry—like a German Panzer division. In future, therefore, an armoured division would consist basically of one armoured brigade group and one motor brigade group. The former would contain three tank regiments, one motor battalion, and a regiment of field and antitank guns, and the latter three motor battalions and a similar artillery regiment. In addition, both types of brigade group would include light anti-aircraft artillery, engineers, and administrative units. The Army tank brigades, each of three regiments of ‘I’ tanks, would not form part of a division, but would continue to be allotted as the situation demanded.

The second decision concerned the infantry brigade. Here General Auchinleck thought that a permanent grouping of the various arms would make for better co-operation between them. In future, therefore, an infantry division would consist of three infantry brigade groups, each containing three battalions, a regiment of field and anti-tank

guns and a proportion of light anti-aircraft artillery, engineers, and administrative units.

These changes made it necessary to alter the composition of certain units. A regiment of horse or field artillery, for compactness, was now to contain three batteries each of eight 25-pdrs and one battery of sixteen anti-tank guns. (The anti-tank batteries would be provided by the existing anti-tank regiments which would then disappear.) A motor battalion was to consist of three motor companies, and one antitank company of sixteen guns. An infantry battalion was to consist of a headquarter company, three rifle companies, and a support company of a mortar platoon, a carrier platoon, and an anti-tank platoon of eight guns.14 The intention was to give the artillery the new 6-pdr anti-tank gun, and the infantry and motor battalions the 2-pdr.15

The tanks on both sides had undergone some changes since the fighting of the previous winter. The Crusader Mark II had slightly thicker frontal armour than the Mark I, but was no more reliable mechanically. The Germans had received so many reinforcements since the New Year that it must be assumed that almost all their tanks now carried thickened frontal armour, which was face-hardened—an important consideration in view of the fact that on the British side only the Stuart’s 37-mm. gun was provided with capped ammunition. This among other factors in the struggle between guns and armour is discussed in Appendix 8.

Apart from these changes there were two important newcomers. The Germans had begun to receive a new model of Pzkw III, called ‘III Special’, armed with a long 5-cm. gun similar to the highly successful Pak 38 anti-tank gun. The extra length of barrel gave greater muzzle-velocity and penetration than the short 5-cm. with which the bulk of the Pzkw IIIs were still armed. Only nineteen of the new model took part in the early fighting at Gazala.

The British, for their part, had begun to receive their first American medium tanks—the M3 or General Grant—whose main armament was a 75-mm. gun firing either a high-explosive shell or a 14-lb. uncapped armour-piercing shot.16 Its arrival was welcomed by the Middle East as ‘a resounding event ... for it provided the means of killing German tanks and anti-tank gun crews at ranges hitherto undreamed

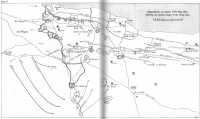

Dispositions at dawn 27th May 1942, showing the opening stages of the enemy plan

of. And this could be done from behind the heavy armour of a reasonably fast and very reliable tank’. In the turret was a high-velocity 37-mm. gun, similar to that of the Stuart. The Grant would have been better still if its 75-mm. gun had been mounted in the turret instead of in a sponson at one side, and if the latest armour-piercing ammunition had been available for it.17

The introduction of the Grant led to changes in the equipment of the British armoured regiments. There were obvious advantages in giving a regiment only one type of tank, but the whole programme depended upon what arrived from overseas and there were strong psychological reasons for giving every regiment some of the new and powerful Grants. The plan decided upon was for some regiments to have two squadrons of Grants and one squadron of Stuarts; others would have two squadrons of Crusaders and one squadron of Grants. Some armoured brigades would consist of regiments which had only American tanks, and others of Crusader-Grant regiments. This plan seemed to give the best compromise between speed of re-equipping and tactical and administrative advantages.

In the event the battle began before all the foregoing changes had been completed. Neither of the armoured divisions had changed over to the one armoured and the one motor brigade organization. Some progress had been made with the ‘brigade groups’ in the divisions of the 8th Army, but only 112 of the new 6-pdr anti-tank guns had arrived, so that many anti-tank batteries were still armed with the 2-pdr and many of the infantry and motor battalions had not got their anti-tank guns. Many artillery regiments had not yet changed over to the new organization. The three armoured brigades were up to strength in tanks, though some regiments had barely received all their Grants when the battle began.

It has been seen earlier in this chapter how reluctant General Auchinleck was to attack until he had the strength to beat the enemy decisively. Much work, however, had been put into the administrative preparations for an eventual offensive. Three forward bases were to be established: one at Tobruk containing 10,000 tons of stores, one at Belhamed of 26,000 tons, and a small one at Jarabub of 1,000 tons. The extension of the desert railway from Misheifa had begun as soon as the enemy’s frontier garrisons had surrendered, and by the middle of February the working railhead was at Capuzzo. In spite of much interference from the air the line was pushed on to Belhamed, where a temporary railhead was opened late in May. All this time stores had been arriving by road, rail and sea, and by 25th May the forward bases were roughly four-fifths complete except for petrol, which fell short at Belhamed by about one-third. This shortage was mainly

caused by attacks on ships on the Tobruk run, nearly 400,000 gallons having been lost when the Cerion and Crista were severely damaged by enemy aircraft in March. In April and May two more petrol carriers, the Kirkland and Eocene, were sunk by U-boats. Altogether from February to May five destroyers, six supply ships, and one hospital ship were lost in coastal operations from U-boat and air attack, and other ships were damaged. It had been far from easy to find the warship and fighter escorts for the Tobruk convoys: larger and less frequent convoys could not have been run without exposing too many ships for long periods in Tobruk harbour. The Army did its best to help by using the land route to the fullest possible extent, and generally speaking the administrative preparations may be said to have placed the maintenance of the 8th Army on such a firm foundation that there should be no cause to fear a breakdown. It will be seen, however, that the valuable base at Belhamed—which held for example 1½ million gallons of motor fuel—became something of an embarrassment to General Ritchie. In the battle which came about instead of the intended offensive, this base was too close to the fighting.

By 10th May, the day on which General Auchinleck was told that he would be right to fight a major battle during May and the sooner the better, there were already indications that Rommel was preparing to attack on a big scale. The 8th Army, on the other hand, was by no means ready, except administratively, to attack, and the prospect of fighting on its prepared position was welcome. On 16th May General Ritchie issued an instruction in which he gave his intention as ‘to destroy the enemy’s armoured forces in the battle of the Gazala–Tobruk–Bir Hacheim position as the initial step in securing Cyrenaica’. The British dispositions in this area are shown on Map 25 and it will be noticed that the distances separating the positions held by the frontline brigade groups were considerable; for instance, from the Free French locality at Bir Hacheim to that of the 150th Infantry Brigade Group was about thirteen miles, and from there to the 69th Infantry Brigade Group was about six miles. Thus these localities were too far apart to be mutually supporting, but they were well dug and wired and held about a week’s supplies and ample ammunition. The whole front from Gazala to Bir Hacheim was covered by fairly thickly sown minefields which at the southern end formed the sides of an inverted triangle with its apex at Bir Hacheim. These minefields were really a compromise solution to the problem of how far to extend the desert flank in the absence of any natural obstacle for it to rest on. If, for a given number of troops, the whole front were kept short it would be locally strong, but the enemy would be put to no great trouble in driving round it. If it were long it would be weaker, but if the enemy tried to drive round it he would have farther to go, and all his problems of supply would be increased. In the event the enemy did drive

round: the minefields had an important bearing on the fighting, but like any other obstacle that is not under the close fire of the defence they could, in time, be breached.

Behind the main line were other widely separated positions intended to block the more defined tracks and centres of communication or to form pivots of manoeuvre for the mobile forces. They are shown on the map at Commonwealth Keep, Acroma, Knightsbridge, and El Adem, but it must be noted that between the last two the escarpment is passable to vehicles in about five places only. The position shown at Retma was nearly ready a few days before the attack, but those at Pt 171 and Bir el Gubi were not begun until 25th May. The main forces under General Ritchie’s command were:

13th Corps (Lieut.-General W. H. E. Gott)

1st and 32nd Army Tank Brigades

50th Division (Major-General W. H. C. Ramsden)

69th, 150th and 151st Infantry Brigade Groups

1st South African Division (Major-General D. H. Pienaar)

1st, 2nd and 3rd South African Infantry Brigade Groups18

2nd South African Division (Major-General H. B. Klopper)

4th and 6th South African Infantry Brigade Groups

9th Indian Infantry Brigade Group19

30th Corps (Lieut.-General C. W. M. Norrie)

1st Armoured Division (Major-General H. Lumsden)

2nd and 22nd Armoured Brigade Groups

201st Guards (Motor) Brigade20

7th Armoured Division (Major-General F. W. Messervy)21

4th Armoured Brigade Group

7th Motor Brigade Group

3rd Indian Motor Brigade Group

29th Indian Infantry Brigade Group22

1st Free French Brigade Group

Directly under Army Command were:

5th Indian Division (Major-General H. R. Briggs)

10th Indian Infantry Brigade Group

2nd Free French Brigade Group23

‘Dencol’, a small column of all arms, comprising South African, Free French, Middle East Commando, and Libyan Arab Force troops.

Under orders to join the 8th Army were:

from Iraq:

10th Indian Division (Major-General T. W. Rees)

20th, 21st, and 25th Indian Infantry Brigades

from Egypt:

11th Indian Infantry Brigade (of 4th Indian Division)

1st Armoured Brigade.

On 20th May General Auchinleck had given General Ritchie in writing his views on the coming battle. He thought that the enemy might try to envelop the southern flank and make for Tobruk; alternatively he might break through the centre on a narrow front, widen the gap, and then thrust at Tobruk. General Auchinleck regarded the second course as the more likely and dangerous, and expected it to be accompanied by a feint to draw the British armour southward. He suggested that both armoured divisions should be disposed astride the Trigh Capuzzo west of El Adem, where they would be well placed to meet either threat. He saw the 8th Army as consisting of two parts: one, whose task was to hold the fort—in this case the quadrilateral Gazala–Tobruk–Bir el Gubi–Bir Hacheim; and the other whose task was to hit and destroy the enemy wherever he might thrust out. General Auchinleck had made it clear that he did not wish the armour to become engaged piecemeal. ‘I consider it to be of the highest importance,’ he wrote, ‘that you should not break up the organization of either of the armoured divisions. They have been trained to fight as divisions, I hope, and fight as divisions they should. Norrie must handle them as a Corps Commander, and thus be able to take advantage of the flexibility which the fact of having two formations gives him.’

The senior commanders in the 8th Army, however, were by no means sure that the enemy’s attack would be made against the centre. General Norrie thought that it would fall on the 13th Corps and be coupled with a thrust from the south, while General Ritchie expected an approach round the desert flank. There could be no certainty, and preparations would have to be made to meet a main attack against each Corps front or round the south of Bir Hacheim. The last possibility led to the 7th Armoured Division being placed farther to the south than General Auchinleck had suggested. Both armoured divisions were given various alternative roles for delaying the enemy and later counter-attacking in order to destroy him. If he advanced round the south of Bir Hacheim the 7th Armoured Division was to observe and harass him, and the 1st was to be prepared to join in either on the east or west of the 7th.

The basis of 13th Corps’ plan was a resolute defence and local

counter-attacks in each formation’s area. For this purpose two regiments of the 32nd Army Tank Brigade were divided between the 1st South African and 50th Divisions. Two columns of all arms—‘Stopcol’ and ‘Seacol’—were placed by the 2nd South African Division to guard the coastal plain from seaborne or airborne landings, and to hold the passage of the escarpment near Acroma. Naval patrols to guard against seaborne attack were also instituted. The 1st South African and 50th Divisions were each to earmark one brigade group and all the ‘I’ tanks for a future counter-offensive.

The whole British front was actively screened by armoured car patrols and small mobile columns. To these must be given the credit for preventing the enemy from reconnoitring the defensive positions and minefields.

At the meeting of Axis leaders held at Berchtesgaden on 1st May it was decided that General Rommel should attack at the end of May with the object of capturing Tobruk.24 He was not to move farther east than the Egyptian frontier and was then to remain on the defensive while the main Axis effort turned to the capture of Malta, for which purpose some air forces would have to be withdrawn from North Africa. When his supply lines had been made safe by the elimination of Malta, Rommel was to invade Egypt.

Rommel’s plan relied on boldness and speed. He had not a very high opinion of the state of training of the British, and doubted the ability of their commanders to handle armoured forces. In general his information about the British forces in the Middle East was accurate, but he underestimated the strength of the 8th Army in the forward area to the extent of one armoured brigade, one army tank brigade, and three infantry brigades. His knowledge of the tactical dispositions was incomplete, for he knew nothing of the defended locality at Sidi Muftah, and had only the vaguest idea of the mine marshes running down to Bir Hacheim.

He decided to start by creating the impression that a heavy attack was coming between the sea and the Trigh Capuzzo, and placed General Crüwell in command of the whole of this portion of the front.25 In the afternoon of 26th May the troops in this sector were to close up to the British positions and dig in, covered by heavy dive-bombing and artillery fire. Noise and movement were to continue throughout the night. Meanwhile, in the moonlight, a mobile force led by Rommel himself was to sweep through Bir Hacheim with the Italian 20th

Corps (Ariete Armoured and Trieste Motorized Divisions) on the inside of the wheel, and the 90th Light Division and the DAK, now commanded by General Nehring, on the outside. Next morning the Panzer Divisions would turn north towards Acroma and get in rear of the British 13th Corps. The 90th Light Division was to move farther east and create havoc about El Adem and Belhamed. The 1st South African and 50th Divisions would then be attacked from both east and west, and their communications with Tobruk cut by a force (the Hecker Group) landed from the sea. The capture of Tobruk would follow. Four days were considered enough for the whole operation. To ensure supplies during these four days special arrangements were made for the DAK to be closely followed by columns carrying the balance of four days’ rations and water, ammunition for three days’ fighting, and fuel for about 300 miles.

Some last-minute information about the presence of British mobile forces to the north-east of Bir Hacheim caused the plan to be modified. The Ariete Division was now to capture Bir Hacheim while the DAK and the 90th Light Division made a wide sweep round to the south of it. The final plan is illustrated on Map 25.

The strength of the mobile force in tanks was approximately 332 German and 228 Italian. This does not include the Littorio Armoured Division which was only in process of arriving in the back area. Of the German tanks 50 were Pzkw IIs, 223 were IIIs, 19 were III Specials, with the long 5-cm. gun, and 40 were IVs.26 Nearly all the Italian tanks were M13/40 or M14/41 mediums.

On the British side the reorganization of the armoured forces described on pages 213-4 had resulted in the following distribution of tanks in the 8th Army. The 1st and 7th Armoured Divisions and reserves—167 Grants, 149 Stuarts and 257 Crusaders; 1st and 32nd Army Tank Brigades (five regiments)—166 Valentines and 110 Matildas. The 1st Armoured Brigade, under orders to join, had 75 Grants and 70 Stuarts.

During May there had been substantial transfers of Axis aircraft to North Africa, and by the 26th it was estimated that the German and Italian numbers had risen to 270 and 460, of which about 400 in all might be serviceable. It is known now that the actual figures were 312 and 392, making a total of 704 of which 497 were serviceable. The Desert Air Force had some 320 aircraft, of which about 190 were serviceable.27 Behind it, but not under Air Vice-Marshal Coningham’s control, was the rest of the Royal Air Force in the Middle East, with some 739 serviceable aircraft. Similarly, on the Axis side, there were

some 215 serviceable German aircraft in Greece, Crete and Sicily and over 775 Italian scattered throughout the Mediterranean, making a total, excluding Libya and Metropolitan Italy, of about 1,000 serviceable Axis aircraft. The British were therefore outnumbered in the whole theatre and also in the Desert. Moreover, in fighter aircraft performance, the Germans held the trump card in the Me.109F.

Blank page