Chapter 8: German Blockade, British Bombing

The Battle of Britain and ‘The Blitz’ were the most dramatic aspects of Hitler’s efforts to subdue us while we stood alone. But throughout the long months of the German assault on our homeland the enemy was also at work with a weapon which was quieter, more insidious, slower in its effects, but equally dangerous—the long-range blockade.

Until the spring of 1940 the war at sea had gone steadily in our favour. We had brought Germany’s overseas commerce to a stand-still, held her surface raiders in check, cut short the success of her U-boats, mastered her magnetic mines. Even the disastrous Norwegian episode we had emerged with at least one consolation—the campaign cost German Navy one-third of its cruisers and nearly one-half of its destroyers.

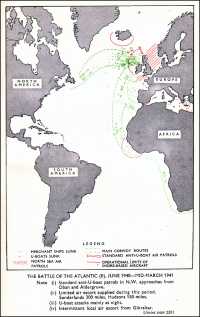

The German occupation of Norway, however, was the beginning of a profound transformation which was all too rapidly completed by the overrunning of France and the Low countries and the entry of Italy into the war. By virtue of these events, the enemy U-boats, E-boats and aircraft at once assumed new and deadly powers of destruction. From bases on the French Atlantic coast U-boats and aircraft such as the Focke-Wulf 200, an adapted civil machine of 2,000 mile range, began to haunt our Western Approaches or reach far out into waters previously free from their predatory attentions. From Norway the Germans harassed our east coast shipping and challenged our reconnaissance over the North Sea. From Sardinia and Sicily, southern Italy and the Dodecanese, Mussolini’s ships and planes threatened the short route to Egypt and forced us into the ‘long haul’ round the Cape. Everywhere in a few swift strokes the prospect became charged with gloom and menace.

In common with the Royal Navy, which found itself desperately short of escort vessels for the new situation, Coastal Command was

faced with a bewildering variety of fresh tasks. Anti-invasion patrols had to be flown over the North Sea and the English Channel, long-range fighter protection supplied over our Atlantic approaches, watch and ward maintained over thousands of miles of hostile coast. Escort patrols for convoys, offensive patrols against U-boats—all must be extended to distances unthought-of in earlier months. Yet for these and all his other duties Air Chief Marshal Bowhill in June 1940 had only some 500 aircraft. And a mere thirty-four of these—the Sunderlands—could operate beyond 500 miles from our shores.

At first the German U-boats and aircraft found their happiest hunting ground in our South-West Approaches. The simplest answer to this was to route our convoys to that they approached British ports by the north-west. This was quickly done. The new traffic line, however, was at once discovered, and the battle promptly shifted to the waters north and west of Ireland. In the absence of suitably placed airfields and flying-boat bases, the result was a still greater strain on Coastal Command. Hard on top of this, in August 1940, the U-boats made matters worse by adopting new tactics. Following up on the surface during the day at a respectful distance from the convoy and its attendant aircraft, they delayed closing in till night fall. Still on the surface to escape detection by the Asdics of the escort vessels, they then attacked under cover of darkness.

To these tactics Coastal Command had as yet no reply. Facilities for night flying were still in a very rudimentary stage in the north-west, and except in bright moon an ordinary aircraft stood no chance of spotting a U-boat. On darker nights, the only hope thus lay in A.S.V. (Air to Surface Vessel) radar, with which about a sixth of the Coastal Command aircraft were already equipped. Unfortunately this was still subject to serious limitations. As the radiations might guide the U-boat to its prey, the apparatus could not be switched on until a convoy was already threatened; even if a ‘contact’ was obtained, the aircraft had no means of lighting up the target; and in any case pilots would run grave risks in descending to ‘depth-charge’ height in bad visibility without a reliable low-reading altimeter—which did not yet exist. The A.S.V. sets at this time also showed little response unless the U-boat was fully surfaced and within a distance of three miles. All told, the immediate outlook was unpromising.

In this situation, and with air and surface escorts alike so weak, our convoys were forced to depend for their safety mainly on evasive routing. This was planned in the light of intercepted wireless signals. The same means also enabled us to concentrate our air patrols over areas where U-boats intended to operate. But information of this

The Battle of the Atlantic (II), June 1940–Mid-March 1941

kind was not always available or reliable, and when it failed, losses were apt to prove disastrous. Between the beginning of June and the end of 1940 over 3,000,000 tons of British, Allied and neutral merchant shipping were sunk by the enemy—an average of some 450,000 tons each month. Fifty-nine percent of this tonnage fell to the U-boats and twelve percent to the Focke-Wulf Condors and other aircraft. The remainder was accounted for by mines and surface-raiders. Over the whole period British losses exceeded replacements by more than 2,500,000 tons, and our volume of imports shrank by one-fifth.

At this stage, then, we were in desperate need of more and better weapons: more aircraft, more destroyers, more A.S.V., more depth-charges, more R/T sets for communication between air and surface escorts—but aircraft of longer range, A.S.V. of higher performance, depth-charges specially designed for dropping from the air. Means of illumination by aircraft, such as searchlights and slow-dropping flares, were also urgently required. Of all this Bowhill at Coastal Command was entirely aware. Yet a mounting volume of criticism now began to threaten his Command—criticism which, instead of fastening on the need to provide all these things with the utmost speed, called in question the whole system of naval and air cooperation. Once more there appeared the demand that the Admiralty should be responsible for all maritime aircraft. At the height of the U-boat crisis Coastal Command was confronted with the danger of being severed from the Royal Air Force and handed over en bloc to the Navy.

In an earlier form this demand had resulted in the compromise of 1937, when all carrier-borne aircraft were transferred to the Admiralty. The main advocate of completing the job by handing over the shore-based maritime aircraft as well was now, curiously enough, the Minister of Aircraft Production. Yet it was far from clear how the proposal would result in any increase in aircraft, which after all was the main consideration; and it was completely certain that the moral of the Command would suffer a grievous, if not irreparable, blow. Lord Beaverbrook’s proposal, too, took no account of the fact that Bomber and Fighter and Commands also played a great part in the war at sea. Fortunately it was a case of being more Catholic than the Pope. The Admiralty, while terming Coastal Command the ‘Cinderella’ of the Royal Air Force and criticizing its training and equipment, were not prepared to go as far as the Minister. In peacetime My Lords Commissioners might have felt otherwise; in the middle of a war they were rightly chary of assuming at one strike so vast and unfamiliar a responsibility.

A great sailor and the great airmen who headed their respective Services had therefore little difficulty in arriving at an agreement which went some way towards meeting naval criticisms without shattering the hard-won unity of British land-based air power. Coastal Command, whose rate of expansion since the outbreak of war already exceeded that of Bomber Command and would have been greater still but for the lamentable failure of the Lerwick flying-boat and the Botha, was to be increased by three squadrons at once and fifteen squadrons by June 1941. It would remain an integral part of the Royal Air Force, alike for administration, technical development and training; but its squadrons could not be diverted to non-maritime work without the consent of the Admiralty. As from April 1941 the Command would also come under the Admiralty’s operational control, which would be exercised through the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief. Apart from some improvement in the means of liaison between the Admiralty and the Command, this made no great alteration to the position, which remained in fact, if not in theory, much what it had always been. The Admiralty specified the broad requirement: the Command decided how, and with what, it should be met.

A more important innovation was the decision to operate Coastal Command aircraft from Iceland. The strategic value of Iceland had been long recognized, and on 26th September 1939 our only Catalina flying-boat had been sent off to reconnoitre its south and south-western coasts. Forced down by fog, the pilot had been technically interned, but within two days had taken off again for Scotland. On official orders he had then returned to Iceland, where the conditions of his internment enabled him to fill the time to good purpose. When British forces forestalled the Germans by landing at Reykjavik on 10th May 1940, a valuable report on the possibilities of the island was available, and in August a squadron of Battles—No. 98—was sent out to strengthen the local defences against a German invasion. Its first flight over Reykjavik, according to the squadron diary, ‘stirred one-half of the townspeople to enthusiasm’—the other half apparently being convinced that the dreaded Hun had at last arrived. But the enemy made no effort to challenge our position, and in the absence of any such attempt No. 98 Squadron came to be occupied more and more with purely naval reconnaissance. For this task its aircraft were unsuited and its crews largely untrained. In January 1941, the decision was accordingly taken to send out a squadron of Hudsons and a squadron of Sunderlands, and by April No. 30 Wing Headquarters had been set up to control the three squadrons. It worked under No. 15 Group, which

had been transferred from Plymouth to Liverpool on the formation of the new Western Naval Command.1 A few weeks later the Battles were withdrawn in favour of Northrop float-planes flown by the gallant young Norwegians of No. 330 Squadron, and by mid-summer Iceland was the base of a small but highly specialized and skilful maritime air force.

The year 1941 opened with tempestuous weather which hampered the U-boats and brought about some decline in the Allied losses. Then the enemy’s successes again began to mount. By 24th February Hitler felt sufficiently sure of himself to prophesy that the struggle would be over within sixty days. The next two months saw the German effort reach a climax. New ocean-going U-boats, powerful reinforcements of aircraft—He.111s as well as F.W.200s—surface raiders like the Hipper, Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Scheer, all played their part. In March the sinkings reached 532,000 tons, in April 644,000 tons. In the latter month no less than 296,000 tons were sent to the bottom by aircraft alone.

This intensified campaign was met by Winston Churchill’s Battle of the Atlantic directive on 6th March, by the creation of the Battle of Atlantic Committee, and by a host of practical measure on a lower plane. Blenheims withdrawn from Bomber Command took over some of the reconnaissance duties in the North Sea, so enabling Coastal squadrons to be moved to the vital north-west. The inestimable boon of bases in Eire remained unhappily denied to us, but new airfields quickly appeared in Northern Ireland, the Hebrides and Iceland. Convoys were strengthened by the arming of merchant vessels and the development of the fighter-catapult ship. A mounting weight of attack fell on the German naval bases; bombs and air-laid mines hemmed in the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau at Brest. At last strong enough to act offensively as well as defensively, Coastal Command began to scour the seas for U-boats far beyond the immediate vicinity of our convoys. All this, and more, was done. To one suggestion, however, the Air Staff remained resolutely deaf; the new long-range Halifaxes were preserved, as they were intended, for Bomber Command. Otherwise there was some danger, as Air Marshal A. T. Harris, then Deputy Chief of Air Staff, put it in his own characteristic fashion, that ‘twenty U-boats and a few Focke-Wulf in the Atlantic would have provided the efficient anti-aircraft defence of all Germany’.

It was not long before ample resources, improved equipment and revised tactics brought their reward. The U-boats, vulnerable to

attack on the surface for several hours each day while they recharged their batteries and emitted foul air, soon show their sensitiveness to our increased air activity by retiring further and further from our shores. By May 1941, when air escort and offensive sweeps stretched out to 400 miles from the coasts of Great Britain and Iceland, the U-boats were largely reduced to operating off West Africa or in the central Atlantic. The West African threat—the lesser of the two—was met by basing Sunderlands and Hudsons near Freetown. The central Atlantic was as yet beyond the range of the FW200s, and without their cooperation the U-boats were nothing like so formidable. At the same time the improved anti-aircraft defences of the convoys and the advent of the first Coastal Command Beaufighter squadron (No. 252) helped to master the ‘Big Bad Wulf’. The difference was soon clear enough. In may 1941 Allied and neutral shipping losses fell below 500,000 tons. In June they declined still further. In July and August they averaged no more than 125,000 tons. The immediate crisis was over.

The turning-point in this struggle was undoubtedly the sinking of five U-boats in March. When our destroyers put paid to the activities of Commanders Prien, Schepke and Kretschmer, they profoundly influenced the course of the whole battle. But the death-blow to Hitler’s hopes of a quick, victory at sea came with the crippling of the Gneisenau and the pursuit and destruction of the Bismarck.

The enemy’s original plan was for the Bismarck, a newly completed battleship of immense power, to cooperate in the North Atlantic with the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. The two battlecruisers had destroyed 115,622 tons during the cruise which finished at Brest on 22nd March, but they had been handicapped by their inability to face the battleship escort of our convoys. The presence of the Bismarck, which was reputed to be more than a match for anything else afloat would remedy this weakness, and in company the three German ships would wreak unprecedented havoc on the British trade routes. Such was the broad German conception in April 1941.

This intention was frustrated by the Royal Air Force. After the Prime Minister’s directive of 6th March our air striking force was ordered to concentrate on objectives connected with the Battle of the Atlantic. When photographic reconnaissance on 28th March confirmed the presence of the two battlecruisers at Brest, they thus at once became a target of great importance not only for Coastal but also for Bomber Command. During the next few nights weather conditions were unfavourable, and though some 200 bombers attacked they scored no hits. but the effort was not wasted, for an unexploded

250-pound bomb caused the Gneisenau to be removed on 5th April from dry dock to the outer harbour. There it was at once detected by a photographic Spitfire, and a strike by Coastal Command torpedo-bombers was arranged for first light the following morning.

As 6th April dawned, a Beaufort of No. 22 Squadron—the only one of four aircraft to locate the target in the haze—penetrated the outer harbour. The Gneisenau was lying in the inner harbour alongside one of the shore quays. To her seaward was a long stone mole; behind her was sharply rising ground; in dominating positions all round were anti-aircraft guns—some 270 of them. Three flak-ships moored in the outer harbour and the battlecruiser’s own formidable armament added to the strength of its defences. Even if the Beaufort survived the fury of its reception, its crew could scarcely hope, after delivering a low-level attack, to avoid, to avoid crashing into the rising ground beyond. The Canadian pilot—Flying Officer Kenneth Campbell—was nothing daunted. Sweeping between the flak-ships at less than mast height, he skimmed over the mole and launched his torpedo at a range of 500 yards. Greeted by a searing hail of fire, his aircraft was instantly shot down, with the loss of all its gallant crew; but the torpedo ran true and pierced the Gneisenau’s stern beneath the waterline. Eight months later the starboard propeller shaft was still under repair.2

With great difficulty the crippled battlecruiser was redocked on 7th April. During the next few days unfavourable weather again frustrated our attacks on both ships, but on the night of 10/11th April Bomber Command inflicted further injury on the Gneisenau by four direct hits and two near-misses. Many of the vessel’s crew were killed or wounded, and extensive damage was done to one of the turrets, to the gunnery and damage-control rooms, and to the living quarters. The Scharnhorst, more fortunate, escaped direct hurt, but her refitting was delayed by the damage to dock facilities.

The enemy’s grand design of a combined break-out into the Atlantic trade routes was thus thwarted, and the Bismarck and an accompanying cruiser, the Prinz Eugen, were left to carry out the mission alone. How they in turn were harried and frustrated, and the Bismarck destroyed, is a striking example of the inter-dependence of modern sea and air forces.

The two German warships were first sighted, thought not identified, by a Swedish warship on 20th May, while passing through the Kattegat. Within a few hours a report reached the Admiralty from our Naval Attaché in Stockholm. The next day both ships were

spotted near Bergen by a Spitfire of the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit, and from the photographs then taken correct identifications were mad. Bad weather hampered air action, but on 22nd May, in 10/10ths cloud down to 200 feet, a Fleet Air Arm Maryland forced its way up the Bergen fjords at very low level and established that theGerman vessels had departed. In continued bad weather our aircraft remained unable to pick up the enemy, and it was a surface vessel in the Denmark Strait, between Iceland and Greenland, which detected the two ships as they attempted to break through into the Atlantic. This was done by radar—as possibility for which the Germans had not bargained. Coastal Command and the Fleet Air Arm as well as our surface vessels then set about shadowing the enemy. The credit for putting our forces firmly on the trail was thus shared by ships and aircraft alike.

The chase then took a fresh turn with the naval action of 24th May, when the ill-fated Hood blew up and the Prince of Wales scored hits which pierced the Bismarck’s oil tanks and reduced her speed. It was this which forced the German commander to make for a French port. But the agonizing uncertainties of the next stage, when the German battleship had covered up the departure of the Prinz Eugen and shaken off her pursuers, were ended mainly by brilliant work at Coastal Command. On 26th May, after many hours had passed with no sign of the enemy, Bowhill on his own initiative laid a patrol further south than the Admiralty appreciation required, and in so doing put Catalina ‘Z’ for Zebra of No. 209 Squadron, piloted by Pilot Officer D. A. Briggs, right on the missing vessel. Circling to confirm her identity, but unluckily breaking cloud only a quarter of a mile away, the flying boat was at once hit. It lost touch, but another Catalina, of No. 240 Squadron, was soon there to regain contact. By then it was too late for our heavy forces to come up before the quarry reached Brest, and every mile would bring the pursuers into greater danger from German bombers based in Brittany. So once more all depended on aircraft—on aircraft directed from the sea. ‘Homed’ on to the target by a shadowing cruiser, which they first attacked in error, Swordfish from the Ark Royal settled the matter when a well-aimed torpedo crippled the Bismarck’s steering gear. Defiant still, the pride of the German Navy was left a dangerous but certain victim for our oncoming surface forces. The whole pursuit had been a drama in which the two elements, air and sea, in turn dominated successive scenes.

A few days later, on 14th June 1941, Bowhill was posted from Northwood to form Ferry Command. The day before, the pilots of No. 42 Squadron gave him a parting present of his favourite kind by

torpedoing the Lützow off Norway. By that time, the worth and importance of Coastal Command were established beyond dispute. From being concerned almost entirely with reconnaissance, the Command had developed into an offensive weapon capable of inflicting serious damage on enemy warships, merchant shipping, aircraft and shore targets. Its equipment had improved out of all recognition. The nineteen squadrons of 1939 had grown to forty. The average range of its aircraft had doubled. Efficient torpedo-bombers and long-range fighters—though still all too few—had taken their place in the line of battle. More than half the aircraft of the Command had been fitted with A.S.V.—an improved A.S.V. effective at twice the range of the initial model. Experiments in the camouflage of Coastal aircraft and the development of an airborne searchlight were about to be crowned with success. It was with the knowledge that many, though by no means all, of the basic problems and difficulties had been overcome that Bowhill handed over to his successor, Air Marshal Sir Philip Joubert.

Joubert, an extraordinarily keen-witted and versatile officer, was no newcomer to Coastal Command. He had already presided over its infant destinies in 1936–1937, when his ever-active intelligence had stimulated the development of airborne radar for locating ships at sea. After a spell in India just before the war, he had taken up the new position of Assistant Chief of the Air Staff (Radio) at the Air Ministry, in which capacity he had held a watching brief on all the manifold aspects of radar—no hint of which was as yet allowed to appear in his deservedly popular broadcast commentaries. It was because the air war at sea, like the bombing offensive, was becoming increasingly dependent on radar that Joubert was now reappointed to his old command. His first task was accordingly clear: to develop the most effective operational technique for A.S.V. aircraft, and in so doing to make the aeroplane at last a ‘U-boat killer’.

There were other subjects, too, in which there would be ample scope for Joubert’s talents. But in one respect he would be well content to leave matters as he found them. Under Bowhill, for all the shortages and difficulties of the period, the spirit of the Coastal crews had remained superb. Every demand, whether for the steely determination and cold courage of a daylight attack on Brest, or the patient, alert endurance of a U-boat hunt, had been met with equal fortitude. Only rarely had the crews been rewarded by the sight of some really satisfactory piece of destruction—‘The chimney’, reported one pilot lyrically after attack an oil refinery in Brittany, ‘was tossed from its base like a caber’. Promising-looking enemy vessels, too, had a disappointing habit of turning out, on closer inspection,

to be wrecks, or shoals of porpoises, or even basking whales. Yet the keenness and skill of Bowhill’s airmen had never become blunted. Cheerful and unwearying, they had faced long, monotonous hours of flying in which danger, if not ever present, had never been far distant. The newly made landing ground, with its toll of fatal crashes: the faulty engine or compass 400 miles out to sea: the fierce Atlantic ‘front’: all too-frequent attack from friendly flak or fighters: the landing with base blanked in mist or cloud and the aircraft too short of fuel to fly elsewhere—these, no less than the sharp, unforgiving clash with the enemy, were among the hazards they had accepted undeterred.

To turn the pages of the Operations Record Books of the Coastal squadrons is to recapture, despite the stereotype entries, something of these slow, uneventful hours so sharply broken by moments of deadly danger. Sometimes—it is the exception—a recording officer with a gift for putting pen to paper gives us not merely fact, but atmosphere. Such a record is that of No. 217 Squadron at St. Eval, where the mist rolling in from the Atlantic, the absence of convenient alternative landing grounds, and the frequent attentions of the enemy, provided no lack of incident:

St. Eval. 29.1.41

Beaufort A, which returned because of a faulty airspeed indicator, crashed on landing. When the remainder returned, conditions were very awkward at St. Eval. A mist had formed over the aerodrome, about 200 feet thick, and prevented the returning pilots from seeing the ground. The goose-neck flares were lighted, but the Chance Light was almost useless because of reflection from the most … P/O. W___ circled for some time without being able to see anything, then saw a break in the mist and recognized Mawgan Porth. He made several darts at a flare-path, but, as he said later, ‘every time it came into view it was in a different place!’ Eventually he landed anyhow, but ran into a patch of mist just as he was holding off. The machine must have touched and ballooned, because next time it hit, one wheel was pushed up through the wing. None of the crew was hurt.

Another machine landed across the flare-path and swung. It was sliding sideways in the mud when the undercarriage hit the runway and collapsed sideways. No one was injured.

Sergeant S___ had rather a shaky do. He was circling just above the mist when he felt his wheels hit something, probably the hills to the south east. He hastily climbed.

Flight Lieutenant O___ landed rather roughly, overshot and finished up in the Hurricane Dispersal Point. He taxied out, rather shaken, between two picketed machines.

A few months later, the diarist presents another angle:

St. Eval. 8.5.41.

About midnight, Group decided they wanted three machines for a moonlight convoy, though they had already released the squadron.

Action of the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen, 20 May–1 June 1941

Flying Officer K___, who was duty officer, nearly howled himself hoarse over the phone trying to find crews who had been released, and finally he got a large transport and drove around the countryside pulling out every aircrew he could find from bed, billet or hotel. Eventually he got two complete crews into camp, and the Station Commander washed out the job. Were the crews pleased!!

But ‘higher authority’, that convenient repository of all the sins, is not the only enemy:

St. Eval. 10.5.41.

Pilot Officer K___ and Squadron Leader R___ were just taxying out to take off, when they were stopped by the ‘Alert’. They taxied back to the perimeter track and switched off. After sitting in their cockpits for a while, it suddenly struck them that sitting on top of 2,000 pounds of bombs during a raid was rather silly a business. So they got out. Then the stuff began to fall, the R___’s aircraft was written off by a direct hit. R___ himself went into a ditch, and his observer head first into a bed of nettles. Altogether seven aircraft of the squadron were damaged—mostly written off. A/Cs Collier and Ball put up to a very good show by towing a bowser which was on fire away so that it could burn out in safety. One of them actually had to climb under the bowser to attach a cable to it. Their prompt and courageous action undoubtedly saved another aircraft from destruction.

And when Group and the Germans fail to come up to expectations, there is always the weather:

St. Eval. 22.5.41.

One of the ‘St. Eval’ speciality days—that is, fog and rain, consequently no flying. Four Beaufighters were expected to come in from Gibraltar. Flying Officer M—(late of this squadron and therefore knowing the local weather) took one look at the south coast and went down in the sea in Mount’s Bay. His aircraft floated for about 1¼ hours, but the fishing boat besides which he landed left them bobbing about in the water for half an hour before deciding they were not Huns! Another Beaufighter got in at Perranporth. The third went down in Ireland, and the fourth at Weston Zoyland.

–:–

‘The Navy can lose us the war, but only the Air Force can win it. Therefore our supreme effort must be to gain overwhelming mastery in the air. The Fighters are our salvation but the Bombers alone provide the means of victory. We must therefore develop the power to carry an ever-increasing volume of explosives to Germany, so as to pulverize the entire industry and scientific structure on which the war effort and economic life of the enemy depend, while holding him at arm’s length from our Island. In no other way at present visible can we hope to overcome the immense military power of Germany …’

Thus the Prime Minister to the War Cabinet on the first anniversary of the outbreak of war. It was a policy with which the Air Staff

was in entire agreement. Indeed, their only regret was that a more powerful bombing offensive against German industry was not already under way.

Since the fall of France much of Bomber Command’s work had been defensive—first in reducing the threat from the enemy’s air force, then in disrupting the preparations for invasion. Targets in the directly offensive category, such as oil plants, had received less attention then they were normally reckoned to deserve. This arose from no fault of the Air Staff, whose belief in the value of a strategic offensive never wavered. Still less did it represent the ideals of Portal, who in the brief interval before the Battle of Britain protested against the use of Bomber Command to ‘bolster up Fighter Command, the A.A. defences and the A.R.P. before these had been really tried and found wanting’. Nor could it rightly be blamed on the Admiralty, whose incessant desire for the bombing of German naval objectives was entirely natural in the circumstances. The concentration on defensive bombing was, of course, simply a reflection of the general military situation. For nearly a year after the fall of France, the Germans, being free to devote their whole military effort to our destruction, could dictate the sequence of operations. The Battle of Britain, ‘The Blitz’, the blockade, were the changing facets of their offensive. With a huge numerical superiority on land and in the air, a nd a powerful fleet of surface-raiders and U-boats to challenge our superiority at sea, they held the initiative firmly in their hands. It would remain there until we had defeated their onslaught by the use of every weapon in our armoury.

By the end of September 1940, when the Germans had been forced to abandon massed bombing by day and disperse their invasion flotillas, the first and greatest crisis was over. It is a remarkable indication of the Air Staff’s faith in the conception of a strategic offensive that even in these grimmest hours Bomber Command was never entirely confined to defensive activity. in July and August 1940 twenty-four percent of our bombing effort had been aimed at German oil plants; only in September, when fifty-four percent of the effort was devoted to barge concentrations alone, were operations against oil reduced to a mere four percent. This decline was not allowed to persist a moment longer than the situation required. On the first clear signs of a break-down in the German invasion plans, the Air Staff at once seized the opportunity to reshape the pattern of our bombing policy nearer to their hearts’ desire.

In this determination to resume the strategic offensive our air leaders were powerfully supported by the Prime Minister. But the military and the political conceptions of the forthcoming operations

were by no means identical. With London under heavy bombardment, the politicians desired above all things retaliation on Berlin. The Air Staff, however, being more keenly aware that to reach Berlin British aircraft had to fly five times as far as German aircraft attacking London, favoured raids on objectives within easier range. The difference of opinion, however, went deeper than a choice between bombing the German capital and bombing the Ruhr. The political authorities, exasperated by the German ;Blitz’ and gauging ‘em back!’ They desired, in other words, not merely attacks on Berlin, but indiscriminate attacks—to which end the War Cabinet no 19th September recommended the use of parachute mines. Nothing could have accorded less with the ideas of the Air Staff, who drew an instructive contrast between the results of four German bombs which fell on the Fulham Power Station and several thousand German bombs which fell elsewhere.

The dispute ended in a compromise. The Air Staff agreed to give a high place to Berlin in their forthcoming bombing directive. But they insisted that the attack should be aimed, not against the population at large, but against precise objectives—power stations, gas-works, the electrical industry. In this, of course, they were moved by professional rather than humanitarian considerations. They wanted to do their job as quickly and efficiently as possible; and indiscriminate bombing against a well-disciplined population is—or was, before the atom-bomb—of all means of attack the most extravagant. They were fully as anxious as the political authorities to lower German morale, but they thought that this would best be achieved by, and in the course of, destroying vital industrial plant. Of actual physical injury the civilians would receive quite enough from the bombs that failed to find their mark on the factories.

The bombing directive of 21st September 1940, an interim measure which contemplated as yet only the release of the Whitley Group from anti-invasion works, accordingly gave a high place to power plants in Berlin. Other selected target systems elsewhere in Germany were oil plants, aircraft component and aluminium factories, railways, canals, and U-boat construction yards. The directive was not many hours old when Berlin was selected for a special retaliatory effort. On 23rd/24th September the Whitleys were joined by all available Wellingtons and Hampdens and 119 aircraft took off for the German capital. Their main objectives were the city’s gas-works and electric power stations, with the local marshalling yards and the Tempelhof airfield as subsidiary targets. Weather and icing conditions proved unexpectedly severe, but eighty-four of the bombers managed to

reach Berlin. The only significant success was at Charlottenburg, where incendiaries set fire to a gasometer. Many of the bombs failed to explode, including one which dropped in the garden of Hitler’s Chancellery. Several houses were damaged in the Tiergarten district—the Berlin West End—and 781 persons lost their homes. Twenty-two Germans were killed—ten more than our own losses in aircrew.

Unsatisfactory as operations of this kind were, they were not without some effect of the enemy. Berlin looked forward to a visit from the Royal Air Force no more enthusiastically than London looked forward to a visit from the Luftwaffe. Apart from direct damage to industrial targets and town property, the raids interfered with transport, caused loss or production, and showed the German people that war was not one unvarying succession of German victories. A minor but not unpleasant by-product was Hitler’s discomfiture when the arrival of our bombers coincided with that of distinguished foreign visitors. On 26th September, Ciano, travelling to Berlin, was turned out of the train at Munich: ‘Attacks by the Royal Air Force endanger the zone, and the Führer does not wish to expose me to the risk of a long stop in the open country. I sleep in Munich and will continue by air.’

Attacks on the scale of 23rd/24th September against the German capital were not yet the rule, and until the end of the month the invasion ports continued to attract the attention of the bulk of our bombers. An incident which occurred on the night of 9/10th September provided a good example of the dangers of adverse weather even on one of these short-range trips. Near its objective, the port of Boulogne, a Wellington of No. 149 Squadron ran into a severe electric storm. Climbing to avoid this, the aircraft was caught in even more turbulent conditions which for a few seconds left it uncontrollable. Badly iced up, it began to lose height, while the pilot, his vision obscured by the ice on the windscreen, and his compass hopeless defective, turned for home. Within a few minutes the port engine failed and burst into flames. Ahead the crew could catch glimpses of searchlights on the English coast, but as the aircraft drew nearer the light went out. Then the starboard engine fell silent. For a few minutes the Wellington glided down, while the crew peered anxiously into the murk beneath. By now, it seemed, they should be over land, and in any case they could not delay their jump much longer. But the aircraft, unknown to its occupants, had turned on a course parallel with the coast, with the result that the crew took to their parachutes some miles out to sea. Only one of the six men survived. Aided by his ‘Mae West’, Pilot Officer C. W. Parish, the second pilot, and a comparative newcomer to operational work,

floated and swam for several hours towards land, to which he guided himself at times by glimpses of searchlights, at times simply by the North Star. Despite cramp and sickness he kept going till dawn, when a final effort brought him to the shore. In full flying kit, save for his discarded boots, he had swum something like seven miles in the dark—an ordeal which apparently left him with little the worse, for he was back to duty and bombing Berlin within a fortnight. Two and a half years later, his brief career—long only for a bomber pilot—was to end on his fifty-fourth operation.

At the close of September more bombers were released from anti-invasion work, and on 6th October renewed attacks against Italy were authorized. Less than a hundred sorties in all had thus far been directed against Italian targets, and many of these had gone astray. Indeed, the most satisfactory feature had been, not the bombing, but the understanding attitude of the Swiss towards our use of their air. This may be gauged from the two wishes good-humouredly expressed by a Swiss representative—that if we had to pass over Switzerland, we would use the Geneva route, and that when the weather made it impossible for us to fly over his country we would draw attention to the correctness of our attitude. But the hope of attacking Italian industry in much greater force, like that of attacking Italian industry in much greater force, like that of attacking Germany, was soon disappointed. The needs of defence again came to the fore, the Admiralty pressed for action against the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in Kiel, and in October over a third of our bomber sorties were directed against naval and coastal objectives.

Before October was out Sir Cyril Newall, whose services in building up the Royal Air Force and guiding it through its greatest hour of trail had been second to none, reached the age of retirement. He was succeeded by Portal from Bomber Command. The new Chief of Air Staff, a man of quiet but powerful resolution whose polite address, discretion and immense ability mad an immediate impression on all who met him, came to Whitehall imbued not only with enthusiasm for the bombing offensive against Germany, but also with a first-hand appreciation of its difficulties. His place at Bomber command was taken by Air Marshal R. E. C. Peirse, who as Vice-Chief of Air Staff had already been closely concerned with our bombing policy.

The effect of Portal’s appointment was seen in the new ‘winter’ directive issued on 30th October 1940. Oil plants remained ‘top priority’, but they were to be attacked only in bright moonlight, when there was some chance of hitting them. ‘Fringe’ coastal targets, mining (by the inexperienced crews), Italian targets, marshalling yards, Berlin, all figured in the directive. But the essence of the new policy was then that the precise objective selected for attack—the power

station, or oil refinery, or aircraft plant—should be situated in a well-populated centre. In the words of the directive, ‘regular concentrated attacks should be made on objectives in large towns and centres of industry, with the primary aim of causing very heavy material destruction which would demonstrate to the enemy the power and severity of air bombardment’. While still intent on damaging individual factories, the Air Staff thus recognized that these were being hit less frequently than might appear from the crews’ reports, and that at the same time some retaliation for the sufferings of British towns would not be amiss. Accordingly, they were now choosing, not merely profitable targets, but profitable targets in profitable targets in profitable surroundings.

From this to ‘area bombing’ was a short and natural progression. In November a small force of bombers attacked Berlin, Essen, Munich and Cologne; in each case a target in the middle of an industrial area was chosen as the general aiming point. Then, on 16/17th December, as the result of a War Cabinet decision four days earlier, came an experiment in heavy concentration in the ‘Coventry’ manner. Two hundred and thirty-five aircraft were ordered, under the not inappropriate code-name ‘Abigail’, to bring about the ‘maximum possible destruction in a selected German town’. Fourteen of the most experienced Wellington crews were to bomb first with incendiaries; the rest, navigating individually but helped by the fires, and carrying incendiaries; land-mines and the biggest available bombs, were to arrive in succession over the target area throughout the night. The choice of objective was to be mad at the last moment, in accordance with the weather forecast, from three towns in different areas of Germany—Bremen (‘Jezebel’), Düsseldorf (‘Delilah’) and Mannheim (‘Rachel’).

At 1015 on 16th December the waiting squadrons obediently booked a date with ‘Delilah’, only to have it changed three hours later for a rendezvous with ‘Rachel’. Good weather was reasonably certain for the first part of the night, but not for the early hours of the following morning, and the number of aircraft was accordingly cut down to 134. The moon was bright, with excellent visibility, and 103 aircraft claimed to have made their way successfully to Mannheim. All the later sorties had no difficulty in recognizing the town from the flak and the fires. The aiming point was officially 1,500 yards south of the Motorenwerke-Mannheim—a works engaged in the production of Diesel engines for submarines—and 89 tons of H.E. and nearly 14,000 incendiaries (including a number of special 250-pounders) were dropped in the six hours of attack. Total casualties, including crashes on return, were ten aircraft. Among the noteworthy

incidents, Pilot Officer Brant of No. 10 Squadron brought his Whitley back from south-west Germany to Bircham Newton on one engine, jettisoning guns, ammunition and all loose objects to maintain a height of 2,000 feet over the sea.

The contemporary German record of the raid makes somewhat disappointing reading. The scale of attack was estimated at 40–50 aircraft, and the number of bombs dropped at 100 H.E. and 1,000 incendiaries. Most of the damage occurred in the residential area of Mannheim, but several bombs fell across the river at Ludwigshafen. Many aircraft were reported to have bombed from a great height without aiming, owing to the strength of the anti-aircraft defences. Sixteen large and seventy-five medium and small fires were caused, fire-fighting being made difficult by bomb damage to the main water system and by the freezing of water brought from the Rhine. A sugar and a refrigerator factory were put out of action, the Mannheim-Rheinau power station was damaged, and output of armoured fighting vehicles and tank components from the Lanz works was cut by a quarter. Four other industrial plants were also hit. Twenty-three Germans were killed and eighty injured.

No further attacks of this sort were made during the rest of December. The Admiralty was now clamouring for action against the U-boat bases at Lorient and Bordeaux as well as the construction yards in Germany, and by the end of the year as big a weight of bombs was being aimed against naval targets as against all other types of objectives put together. A run of bad weather also helped the German towns to escape further serious damage for the time being, and enabled both side to make a virtue of necessity at Christmas.

The next experiment in area bombing was an attack on Bremen early in January 1941. Then, following the latest report of the Lloyd Committee on German oil production, came a sharp revulsion of opinion. The new report emphasized once more that the Axis powers would be dangerously short of oil until Germany had increased her domestic production and overcome the difficulty of transport supplies from Rumania. The critical period would be the first six months of 1941, during which time any further significant reduction in German output of the synthetic product—the Committee considered that a cut of 15 percent had already been achieved by our bombing—would have consequences of the highest value. If the nine largest synthetic plants could be destroyed, out of the total of seventeen, output would be reduced by eighty percent, and a devastating blow struck at the entire German war effort. On 15th January Peirse was accordingly instructed that the whole primary aim of the bombing offensive, until further orders, should be the destruction of the

German synthetic oil plants. The secondary aim, when the weather was unfavourable for the major plan, would be to harass industrial towns and communications. The only diversions contemplated from this strict programme were such operations as might be necessary against invasion ports and enemy naval forces.

This renewed attempt to concentrate against oil broke down before the threat to the French armies. The directive was not many days old when an extra task was reimposed in the form on mine-laying. The came requests for the bombing of the Hipper at Brest and of the Focke-Wulf bases at Bordeaux and Stavanger. Next it was considered essential to delay the completion of the Tirpitz at Wilhelmshaven; over 400 sorties were despatched against this target within two months. Finally there was the decision to divert Bomber Command Blenheims to coastal duties in the North Sea, so that Coastal Command could be reinforced in the North-West Approaches. The result, taken in conjunction with a good deal of unfavourable weather, was that during January and February 1941 the bomber force operated exclusively against its priority objective, oil, on only three nights. Against naval targets it operated exclusively on thirteen nights and partially on six. Only one attempt was made during these two months at a crash concentration against a German city by over two hundred aircraft. On 10th February 221 bombers—the largest force thus far detailed against a single town—took off to attack an industrial areas in Hanover. It was chosen for its importance in the manufacture of U-boat components.

All this was before the Prime Minister’s directive of 6th March 1941 gave absolute priority to the Battle of the Atlantic. During the seven weeks that followed, more than half the total bombing effort was directed against naval targets. At Brest, as already described, 1,655 tons of bombs were aimed at the German battlecruisers in two months. From Norway to Brittany the Blenheims of No. 2 Group, reverting entirely to daylight operations, sought out and struck at enemy shipping. Mines were laid off the Biscay ports and the Frisian islands. In Germany the weight of attack fell, not upon the Ruhr or Berlin or the oil plants, but on the ports and dockyard towns of the north—Hamburg, Bremen, Kiel and Wilhelmshaven.

From the 1,161 Bomber Command sorties against the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in the eight weeks following their arrival at Brest, only four bombs found their mark. Peirse soon grew restive at this kind of work. On 15th April, after conclusive reports of damage to the Gneisenau and the sowing-in of both ships by mines, he demanded impatiently whether he was ‘to continue ad nauseam to cast hundreds

Principal targets attacked by Bomber Command, 3 September 1939–31 December 1941

of tons more on to the quays and into the water of Brest harbour’. His complaint met a ready response at the Air Ministry, where targets in the enemy’s homeland were naturally regarded with greater favour than targets in the occupied territories. By return signal he was permitted, subject to agreement by the War Cabinet, to transfer his primary effort to objectives in Germany until any fresh movement of the battlecruisers was suspected. Unofficial approval from the Prime Minister was at once obtained, and by the time formal approval from the War Cabinet followed three weeks later the new policy was well under way.

Operations against the north German ports proved a much more profitable affair than repeated assaults against the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Hamburg, second largest city in the Reich, was attacked in force eight times in early 1941–twice in March, once in April, five times in May.3 During the May raids the Blohm and Voss shipyards were hit three times in five nights, and much damage was done to the docks. Bremen, too, suffered severely. Excellent results were obtained in January, when the buildings and the river stood out vividly from the snow-covered countryside. An important machine-factory sub-contracting to the U-boat building yards of Bremer Vulkan, a searchlight and dynamo factory, a power station, the woods were among the industrial objectives completely destroyed or heavily damaged, and the whole city was left, according to one of our pilots, ‘like a gigantic illuminated Christmas-tree’. In March, the Focke-Wulf works—which made not only the Condor but the new F.W.190 fighter and the Me.110—received further damage. In May the main objectives to suffer included the docks, the railways, the Atlas shipbuilding and naval component works, and the Weser aircraft factory, where Ju.88s and Dornier flying-boats were produced. Focke-Wulfs, too, were again hit.

Still better results were obtained at Kiel. As the main German naval base and one of the greatest centres for building ships and U-boats, Kiel had a standing claim on the attention of our bombers. In the first two months of 1941 it was attacked only lightly, since the Admiralty gave priority to Wilhelmshaven, where the Tirpitz was nearing completion. Between mid-March and the end of May, however, Bomber Command flew no less than 900 sorties against Kiel—the largest number against any town in Germany. The climax came in mid-April, when 288 and 159 bombers attacked on successive nights. After this there was something approaching devastation at the

main objectives, with the three great naval shipyards—the Deutsche Werke, the Krupp Germania Werft and the Kriegsmarinewerft—reporting temporary losses of production of 60, 25 and 100 percent respectively. Among other damage at the Deutsche Werke was the complete destruction of the U-boat welding sheds and many of the welding plants.

Oil plants, warships, merchant shipping, airfields, industrial centres, the north German and Channel ports, Berlin, mine-laying—that were the main, but by no means the exclusive preoccupation of Bomber command in the year following the fall of France. Among minor activity deserving of record, if only for a certain picturesqueness, was the attempt in the autumn of 1940 to fire German crops and forests by means of a new incendiary weapon invented in America. This consisted of two strips of celluloid about three inches in length, between which was a small piece of phosphorous wrapped in wet wadding. The leaves—code-name ‘Razzle’, or, in a larger version, ‘Decker’—were packed in liquid, some 450 to a tin, and dropped through a special chute. After several hours on the ground the phosphorous dried out and ignited the celluloid, which burned for thirty seconds. A few fields and woods suffered from our attacks, but the advocates of the weapon seem to have taken too favourable a view of northern European weather, and results on the whole were insignificant. According to the Neue Frankfurter Zeitung, however, many souvenir-hunting Germans received an unpleasant shock after placing the leaves in their trouser pockets.

Another subsidiary task was propaganda. Leaflet-dropping, suspended during the campaign in France, was resumed in July 1940. Usually it was carried out in the course of bombing operations, but it was also undertaken as a final exercise over France for the pupils at Operational Training Units (O.T.U.s). An agreeable variation from the usual forms of propaganda occurred in March and April 1941. About 4,000 pounds of tea, a gift from the Dutch of Batavia, was dropped over Holland in small cotton bags, each weighing two-thirds of an ounce, and bearing the message ‘Holland will rise again, Greeting from the Free Netherlands Indies. Keep a good heart.’ The reaction of the Dutch people to the gift, as reported by their Naval Attaché in London, was—‘Why not bombs?’ The Free French, however, were more impressed, and asked for coffee to be dropped over France. Ten crates, suitably subdivided, were accordingly distributed by O.T.U. crews.

By July 1941, when the immediate crisis in the Battle of the Atlantic was over, Bomber Command was free to adopt an offensive policy. The trials through which it had passed, and was still passing,

had left its crews and its Commander quite undaunted. Forced into a policy of night bombing by the strength of the German defences, it had orthodox navigation inadequate for the appalling difficulties of operating over blacked-out territory in thick weather or absence of moon. Against objectives fairly near at hand or easily identifiable by the presence of water, such as the north German or Channel ports, it had achieved excellent results, but elsewhere, and particularly in the smoke-laden maze of the Ruhr, much of its effort had gone astray. We now know, for instance, that no less than forty-nine percent of the bombs dropped on south-west Germany between May 1940 and May 1941 fell in open country. Evidence of this waste was beginning to accumulate in mid-1941, as night photography improved and more bombers were fitted with cameras. With it would come the danger, unless the subject were carefully handled—and unless there was some prospect of a remedy—of demoralization among the crews and the abandonment of the whole strategic offensive on which so many hopes had been built; for clearly no one could justify devoting so large a share of the national resources to the bomber force unless it held a real promise of consistently impressive results. Fortunately the Command was to hold firm through its gravest hours, while the skill of the scientists at the Telecommunications Research Establishment had already evolved, even before the imperative need for it was put before them, the first of the great radio navigational aids for bombers. By August 1941 the merits of this new system, which was to be known first as ‘G’ and then as ‘Gee’, were clearly established, but many months were yet to pass before sets could be produced in sufficient quantity for effective use. Meantime the Command would have to battle not only against its two constant adversaries, the weather and the Germans, but also against the more insidious foes of domestic doubt and criticism.

Inaccurate navigation and bombing, though in fact the biggest obstacle to the progress of our offensive, had not thus far been the Air Staff’s main worry, for the seriousness of that particular problem was only gradually becoming realized. What was more obvious was that the total bombing effort had been disappointingly small. Bombers had been diverted—to O.T.U.s, to the Middle East, to Coastal Command. Bomber crews had been called upon to ferry Blenheims and Wellingtons out to Egypt, and force one reason and another throughout the winter little more than half the full establishment of crews had been operationally fit. On top of this, naval targets had absorbed most of the available effort. All told, it was little wonder that German industry had escaped lightly.

Yet if the phase now passing had proved a time of trial and not infrequent error, Bomber Command had done much valuable work. It had played a notable part in upsetting the German invasion plans, had made a useful contribution to the defeat of the blockade, and had tied down more than a million Germans to civil and anti-aircraft defence. Even in its weakness, alone of the British forces it had carried war to the heart of Germany. Now it was building up into a more formidable force. In May 1941, with better weather, and a new group (No. 1), operational, it had managed to put down an impressive weight of bombs on the German ports. Nineteen raids of over fifty bombers had been despatched during the month, and on one night—8th May—over 300 bombers had operated. The size of the bombs, too, was increasing—the first 4,000 pound bomb had been used against Emden at the end of May—and the new heavy bombers, the Manchesters, Stirlings and Halifaxes, were coming into service. Problems and difficulties of the utmost complexity still lay ahead, even with the aircraft—the Manchester was to prove a failure, the Stirling a disappointment—but the tactical and technical requirements for an efficient night offensive were becoming clear, and fuller understanding would assuredly breed greater success.

So, as the spring of 1941 gave place to summer, the Air Staff looked forward to better things. ‘The Blitz’ had died away, the shipping losses were falling well below the danger line, the strategic initiative was passing into our hands. No longer compelled to concentrate on defence, our fighters were winning air superiority on the other side of the Channel. In the Balkans a hastily constituted and ill-provided front had broken down in swift and utter collapse, but the back door of Egypt in Iraq had been held as firmly as the front door in the Western Desert. Everywhere the future seemed to hold greater promise. On 22nd June, as the Nazi hordes drove east against Russia, it became certain that Hitler’s folly and our own exertions had indeed earned us a respite. The German onslaught against Britain, so long and valiantly defied, had faltered to an uneasy pause. The British onslaught against German, for many months to come the exclusive privilege of Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force, could at last gather momentum.