Chapter 10: The End in Italy

The fall of Rome on 4th June, 1944, preceded the invasion of France by two days.’ It was very gratifying’, wrote General Alexander in his despatches, ‘to have provided a heartening piece of news so appositely’. Heartening the news certainly was, for Rome was one terminus of the Axis and its fall portended that of the other, Berlin. But though stimulating to the Allies and of no small political significance, it did not bring the war in Italy to an end: far from it. The capture of the city was but a phase, and for those in the air and on the ground who had compassed it there were still eleven months of hard fighting ahead. The Germans, though in sullen retreat, were still in Italy, and it became the immediate object of Operation DIADEM, as set out in General Alexander’s Orders, ‘to destroy the right wing of the German Tenth Army; to drive what remains of it and the German Fourteenth Army north of Rome; and to pursue the enemy to the Rimini-Pisa line inflicting the maximum losses on him in the process.

So the tide surged forward, and by the evening of 5th June the Fifth Army had crossed or reached the Tiber along most of its length from north of Rome to the sea, while on its right flank the Eighth Army, progressing more slowly through minefields, and over blown bridges and blocked mountain roads, had advanced on a seventy-mile front up the middle of the peninsula. Of the Luftwaffe, which might have hindered this progress, little to nothing was seen. Nor was this altogether surprising, for by the beginning of May the OKL (Oberkommando der Luftwaffe)1 , faced with the ever-increasing threat of an Allied invasion of northern France and the necessity to keep every operational unit ready for such an emergency, had withdrawn all Ju.88 bombers from Italy. It is true that in the opening phases of DIADEM the Luftwaffe reacted strongly, but so overwhelming were the Allied air forces that the German formations, usually in strength about thirty fighter-bombers escorted by some fifty fighters, were invariably set upon by superior numbers of Allied

fighters and dispersed before they could reach their targets. After suffering heavy losses in a number of such excursions, of little benefit to the armies and of none to themselves, the F.W.190 Gruppen gave up the practice of fighter-bombing and joined forces with the regular fighters engaged on defensive patrols in rear areas, where the air raid warning network had been strengthened by the introduction of Mobile Signals Troops. Even so, by the end of the month, at Hitler’s behest, all but two of the fighter formations were withdrawn from northern Italy to cope with the invasion of northern France, which had now become an accomplished fact. General Ritter von Pohl, the Commander of the Luftwaffe in Italy, soon found himself with but three Me. 109 Staffeln2 of the Tactical Reconnaissance Gruppe, a much depleted German fighter force, two Italian fighter squadrons, the Long Range Reconnaissance Gruppe and a Nachtschlachtgruppe3 of three Staffeln—all that remained of the once formidable Luftflotte 2. German fighters based in the Bologna-Ferrara-Udine area did, on occasion, make a gesture of defence, as, for example, on 5th June when twenty-five Me.109s intercepted a force of heavy bombers operating over Bologna and lost five of their number for their pains; but such encounters were rare, and more often than not the allied bombers would return from operations to report’ No enemy fighters; no flak; no losses’.

By day and by night the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces kept up a relentless pressure on the retreating German armies, for few targets are so vulnerable from the air as a retreating army which has lost the support of its air arm. No longer came the call for ‘Rover Patrols’ to attack fixed positions and lines of defence. The situation was now fluid and, between the 2nd and 8th June, the Tactical and Strategic Air Forces were able to strike hard blows against targets chosen by the advancing armies. Five thousand tons of bombs fell upon the general battle area, and a further 3,350 tons were aimed against communications north of the Pisa-Rimini line.

Meanwhile, Operation BRASSARD, the capture of the island of Elba, was successfully completed. On 17th June French troops from Corsica, carried and escorted by the Royal Navy, landed against stiff opposition which collapsed two days later. The speed of this operation was due appreciably to the effective support provided by the Thunderbolts and Spitfires of the 87th Fighter Wing based on Corsica, which attacked such targets as gun positions, small craft in

harbour and in the strait of Piombino, and certain harbour facilities. When the invasion and occupation had been completed more than 2,300 prisoners had fallen into French hands and the bodies of some 500 Germans awaited burial. How little the Luftwaffe desired or was able to interfere is shown by the fact that throughout the 19th, the culminating day, only two Me.109’s were encountered by our patrolling Spitfires. Both were shot down.

By mid-June the momentum of the exhilarating chase from Rome, now 130 miles to the rear, was beginning to flag in the face of stiffening resistance. Kesselring, that past-master of the spoiling fight, once more had his troops well enough under control to rally them for the defence of a coherent front. The ‘Gothic Line’, running along that last barrier of mountain before the country opened out into the wide plains of the Po Valley, was still far from complete, and he was doing all he could to hold Alexander in the area south of it while awaiting its completion. The line Kesselring had chosen was based in the east on the River Chienti, across the Apennines to the high ground north of Perugia, Lake Trasimene and Chiusi. From there it ran westwards along the River Astrone to the Orcia and the upper Ombrone. By 20th June LXXVI Panzer Corps, containing the crack 15th Panzer Grenadier, 1st Parachute and Hermann Goring amongst its seven divisions, was addressing itself to the task of delaying our advance on either side of the historic Lake Trasimene.

In spite of vagaries of weather, the Tactical Air Force had kept up an average of 1,000 sorties a day against the German lines of communication and road and rail movements. The pattern of air activity was made up of attacks by medium bombers on railways and road bridges well to the rear; fighter-bombers operated along the bomb-line over secondary roads leading northwards and against more distant rail targets; light bombers attacked supply dumps; fighters were out in their hundreds on armed reconnaissance patrols and tactical and artillery reconnaissances; and there was much light-bomber and defensive fighter activity at night.

The general control of the Force had been unified, but after the break-through south of Rome, when the Fifth and Eighth Armies were gradually spread evenly across the front once more, Desert Air Force Headquarters returned to the Eighth Army and the close support of the Fifth was resumed by the Twelfth Tactical Air Command. Interdiction of rail communications was continued, and since by his withdrawal Kesselring had shortened his lines of communication, the effort was directed farther north. The four rail routes from the Po Valley to Florence were all cut and special attention was paid to the two coastal routes. The Thunderbolts of the 87th Fighter Wing

from Corsica, operating against targets in the coastal area between Leghorn and Genoa, played an important part in these operations.

The battle of Lake Trasimene lasted for approximately ten days, and General Leese, fighting on ground which had witnessed the rout of Flaminius and his legions more than two thousand years before, could, by the end of June, report that the major part of the ridge north of Pescia had been cleared and that the Germans had been driven from the Trasimene Line. Fighting had been prolonged and fierce, and casualties were heavy on both sides. The Allies had gained the important port of Piombino, and Kesselring the time he needed to withdraw his armies northwards, to a new line of defence. These tactics he was to follow until Florence fell, his method being to withdraw gradually to the Arno, turning to fight a series of rearguard actions on phase lines, known by girls’ names in alphabetical order.4 The German forces were now well balanced and there was little chance of seriously disrupting this programme. On 16th July Arezzo fell, and on the next day IV Corps reached the Arno, south of Pisa. On the 18th the Poles captured Ancona and on the 19th the Americans entered Leghorn.

In spite of these hard-fought, hard-won successes, the Allied line at this point was still on an average some twenty miles south of the ‘Gothic Line’. The possibility of a rapid advance to the north of Italy was diminishing daily as stiffer and stiffer resistance was encountered along the whole front. Moreover, diversion of considerable land and air forces away from the Italian front to the south of France, of which the assault was imminent, soon involved such a reduction of Allied strength that any rapid advance in northern Italy became out of the question. Because of this, the veto previously laid by the army on air attacks against road bridges across the Po, and which had been based on the hope that at least one bridge on each front could be seized when the moment came, by airborne troops, was withdrawn. A new plan, ‘MALLORY MAJOR’, was adopted. All bridges were to be broken, so as to confine as many of the enemy as possible south of the Arno, where they would be destroyed. The bridges were vulnerable and the opening attacks were delivered in considerable strength in order to cut them, if possible, before the enemy could mount heavy anti-aircraft cover. Between 12th and 27th July American medium bombers were able to destroy the main rail bridges at Casalmaggiore and Piacenza and the road bridge at Taglio, besides damaging many others. These onslaughts were the

first of many, for the Po bridges soon became one of the most important of the interdiction targets and their destruction a vital factor in the ultimate defeat of the German armies in Italy.

By 19th July active preparations for operation ANVIL, the invasion of the south of France (later renamed operation DRAGOON), were in hand. Headquarters, Mediterranean Tactical Air Force, was transferred from Italy to Corsica to prepare for the coming assault, and the command of the Tactical Air Forces was temporarily reorganized. While retaining general control of all tactical formations, the Headquarters left behind a rear echelon called Headquarters, Tactical Air Force (Italy), to advise the General Officer Commanding, Allied Armies in Italy. XII Tactical Air Command, the predominantly American formation which was responsible for the close air support of the Fifth Army, also moved to Corsica, but continued to operate on the Italian front until needed farther west. Thus the Desert Air Force was left to provide close support along the whole Italian front.

On 4th August elements of the Fifth Army entered Florence. Kesselring’s ‘phase lines’ had been overrun one by one. The Desert Air Force, though now alone in the air above the battlefield, gave such good service that the New Zealanders, held up for a time by particularly determined resistance at Impruneta, south of Florence, were presently able to signal back ‘Many thanks for accurate bombing. Counter-attacks prevented and decisive results brought nearer’. With Florence in Allied hands, a firm base existed for the main attack on the ‘Gothic Line’.

Meanwhile, on the night of 14th/15th August, operation DRAGOON was launched. At approximately 0430 hours, following a small ‘ Pathfinder’ force dropped an hour earlier, the first elements of the Task Force of Paratroops carried by some 400 aircraft of the United States Army Air Force dropped silently to earth through 500 feet of dense fog and dispersed about their allotted tasks of securing fields for the arrival of the glider force. At 0926 hours, in improved weather, the first of the gliders slipped its tow and made a safe landing. It was one of 407 which landed at intervals throughout the day. Altogether, including re-supply missions, 987 sorties were flown. Some 9,000 airborne troops, with 221 jeeps, 213 pieces of artillery and many thousand pounds of petrol, bombs, ammunition and rations—a total weight, exclusive of men, of over 1,000 tons—were thus borne to action. At 0800 hours on 15th August the first beach landings took place between Cannes and St. Tropez against no opposition in some sectors and only slight resistance in others.

For this happy beginning the Allied air forces were very largely responsible. Their preparations for the invasion had been begun on 29th April when a daylight attack by 488 heavy bombers, escorted by 181 fighters, was made on the port of Toulon. By 10th August, when the preliminary air phase of the assault opened, their activities had so increased in intensity that the fact that this day was to see their culmination was not immediately apparent to the enemy. To enhance this deception and to assist the operations in Normandy, as much attention had been paid to communication, oil and airfield targets in central France as to those farther north. Shuttle raids were also made, as, for example, on 5th July when seventy-one Fortresses escorted by fifty Mustangs of the United States Eighth Air Force, based in the United Kingdom, dropped 178 tons of bombs on Beziers marshalling yards on their way back from Italian bases. In this period, a total of some 12,500 tons of bombs was dropped by the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces, mainly on lines of communication.

From 10th to 15th August the Mediterranean bombers concentrated on the Marseilles/Toulouse area and on cutting the railway running from Valence to Modane, while the Tactical Air Forces assaulted rail bridges across the Rhone, south of Valence. The main coastal batteries and radar stations in the assault area were bombed and, in pursuance of the general deception plan, heavy attacks made in four coastal areas between Viareggio and Beziers. Finally, from first light to 0730 hours on 15th August, half an hour before the troops went ashore, heavy attacks were made by all available aircraft against the beach defences.

The Luftwaffe in south and south-west France could muster about 150 long-range bombers, 20 single-engined fighters, 25 twin-engined fighters, 20 long-range reconnaissance and 5 tactical reconnaissance aircraft, a total of 220 aircraft, and although they might possibly be reinforced from other fronts, it seemed unlikely that these additional aircraft would number more than 150 to 200 at the most. Against these the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces could put into the air some 5,000 aircraft or more, if necessary. It was not surprising, therefore, that by 19th August, after a show of resistance lasting four days, during which its casualties were far more serious than the very slight damage caused by the bombs it dropped, the Luftwaffe withdrew from the scene, and with its departure all enemy air activity over the battle area came to an end. In those days, too, the success of the preliminary air bombardment became manifest. Of the six railway bridges across the Rhone between Lyons and the sea, five, it was found, were unusable on ‘D Day’ and the sixth was fit for single line traffic only. In

consequence, German reinforcements from west of that river were held up until 18th August, and on arrival went to swell the army of prisoners which before the first week was over amounted to more than 15,000.

The problem of tactical air support over the highly mobile front was notably facilitated by the operations of the Naval Carrier Task Force 88. Owing to our air superiority, the seven British and two U.S. carriers enjoyed a high degree of security, which enabled them to stay in the vicinity, refuelling in relays, for fifteen days. In addition to naval and beach cover and artillery spotting, their aircraft made a valuable contribution to the land advance, providing close support on short call for ten days while the Corsica land-based units moved progressively to the mainland. While there was no break in support by land-based fighters and fighter-bombers, the close proximity of the carriers and the dash and high performance of their Hellcat and Wildcat aircraft crews provided efficient aid at a critical period, both over the main front and in the reduction of the powerful defences of Toulon and Marseilles.

The form taken by local air support was dictated by the movements of the enemy; his troop concentrations were bombed and assaulted, as were his strong points, his transport, his road bridges and roads, his railway bridges and lines. The exploitation of the initial success by the army was, in these happy circumstances, rapid. In the first week Gap and Chatillon were captured, in the second Grenoble, in the third Lyons and Bourg, and advanced elements had penetrated as far north as Poligny. In the meantime Marseilles had been liberated and, with the fall of Montelimar on the 27th, all organized resistance south of the line Grenoble/Bordeaux had ceased. Such speed would have been impossible without the able and fierce aid given by the French Forces of the Interior and the Resistance Movements generally. By 22nd August, all elements of the Strategic Air Force, and by the 29th those of the medium bombers, were withdrawn because of lack of suitable targets. The fighters and fighter-bombers of the Tactical Air Force could supply all the necessary air cover. By 12th September the forces of General Patch’s Seventh Army joined with those of General Patton’s Third Army in the Avallon–Lormes–Corbigny area some sixty miles west of Dijon, and with this junction the whole of the Allied Forces in France were brought under the Supreme Allied Commander, General Eisenhower, and formed a continuous front of 600 miles from the frontier of Holland in the north to the principality of Monaco on the Mediterranean.

During operation DRAGOON and the subsequent advance Coastal Air Forces played their usual part. They protected the ports of

embarkation, they followed the convoys up to a point forty miles from the beaches, they covered the areas behind the front as they were freed. Throughout the spring and summer of 1944 assaults on shipping by U-boats and the Luftwaffe grew fewer and fewer. Between May and July only eight of the numerous Mediterranean convoys were attacked by U-boats. The losses in shipping amounted to one destroyer and two merchant ships sunk and the like number damaged. Four of the U-boats were destroyed and fourteen Ju. 88’s were shot down. The capture of Toulon and Marseilles left the U-boats in the Mediterranean without an adequate base for operations. On 19th August two were scuttled in Toulon and a third two days later. Three were scuttled on 10th September off the Turkish coast. The last U-boat to be sunk in the Mediterranean was caught by naval forces south of Greece on the 19th and from that date onwards the Mediterranean was no longer troubled by their activities.

Whether the invasion of the Riviera and the subsequent march, almost unopposed, to join General Patton was an operation of greater worth than the rupture of the Gothic Line’ which it postponed—for Alexander had to relinquish some of his best troops to mount it—will no doubt be long debated. To the air forces it brought little toil and little glory. They outnumbered their enemies by more than twenty to one and not surprisingly found themselves undisputed masters of the air from the first moment without having to fight for this privilege. Their fortunate situation was not unique, for in other theatres, too, the whirligig of Time had brought in his revenges, and the Luftwaffe, with death in its face, was drinking deep draughts of the medicine it had administered to others in 1940.

Back in Italy the withdrawal of seven divisions from Alexander for the invasion of Southern France, and the reinforcement of Kesselring by eight, of which one had come all the way from Holland, removed all prospect of further rapid victories. The plan had been to breach the centre of the ‘Gothic Line’ north of Florence and split the German armies in two; but with the departure of some of our best mountain troops such an enterprise was judged impracticable. The new design called for the secret transfer of the main weight of the Eighth Army from the central to the Adriatic sector of the front so that the ‘Gothic Line’ might be pierced near its eastern flank. Geography made such a course almost inevitable. North of Florence the Apennines cease to be the backbone of the peninsula and turn north-west to join the Maritime Alps on the French border. Thus a mountain barrier intervenes across any line of advance up the west coastal plain. Conversely the eastern coastal plain follows the bend of the mountains and, by thus opening out, offers the only

level approach to the Po Valley. The main ‘Gothic Line’ was constructed along this natural barrier. In the west its flank guarded the approach to Spezia. From here it swung south-east to become a chain of strong points covering the roads which run from Lucca to Modena and from Florence through the Futa and Il Giogo passes to the Via Emilia and Lombardy. It then followed the crests of the Alpe di San Benedetto and the Alpe di Serra, until, on reaching the course of the River Foglia, it turned eastwards to reach the sea at Pesaro.

All knowledge of the transfer of the Eighth Army had to be kept from the enemy. This was secured by the efficiency and vigilance of Desert and Coastal Air Force fighters and no enemy pilot on reconnaissance lived to take news of what he might have seen back to Kesselring. Wireless silence was imposed on the Eighth Army and on the Desert Air Force, which with it moved to more easterly bases, and elaborate deception plans executed so that the enemy should believe that our main threat would develop at the centre and that a move in the east would be a feint to divert attention from the real point of attack.

On the night of 25th/26th August the bombers of No. 205 Group, aided by illumination provided by Halifaxes, Wellingtons and Liberators, dropped 205 tons of bombs on the marshalling yards and canal terminus at Ravenna, the rear link in the enemy’s communications with what was to be the main battlefield. Baltimores and Bostons of the Desert Air Force on armed reconnaissance roamed behind the front along the roads and railways, their mere presence causing lights to be extinguished and movement to cease.

The Eighth Army’s attack was launched an hour before midnight on 25th August. Surprise was complete. More than that, the assault caught the enemy when he was in the midst of executing a complicated withdrawal and regroupment. The fact that in executing this manoeuvre he was falling back as we advanced made it hard for him to detect the weight of our attack, which he mistook for an advance to occupy ground which he was voluntarily abandoning. Not until the 29th did the German Corps Commander appreciate the full implication of the Eighth Army’s secret concentration and realize that a break-through was intended. His reaction was violent, but in spite of it elements of V Corps and the Canadians crossed the River Foglia and captured forward positions in the ‘Gothic Line’ before the enemy had had time to man them. Further advances on 31st August and 1st September gave the Allies a stretch of the main defences some twenty miles long from the coast to Monte Calvo. These works, too, were untenanted, many of the minefields were still

carefully marked and set at ‘safe’, and the newly arrived garrison of one position were captured while sweeping out the pill-boxes they were about to occupy. The air forces had done their work and, having so well begun, continued to press hard. The Desert Air Force was directed against such close-support targets as gun positions, strong points and enemy troops and transport moving against the Eighth Army. Its Baltimores and Bostons combed the roads far in the rear seeking everywhere for a prey. After nightfall, Wellingtons and Liberators of the Strategic Air Force, aided by Halifaxes dropping flares, took up the burden and on one night loosed 231 tons of bombs against troop concentrations at Pesaro, while night Beaufighters kept an uneventful look-out for any enemy bombers.

With the success of the south of France landings the Germans were denied the use of the Riviera and Mont Cenis supply routes into Italy. This left them only four railway routes into the country; the Brenner line into northern central Italy and the Tarvisio, Piedicolle and Postumia lines into the north-east. In the four days ending on 29th August, American heavy bombers of the Strategic Air Force dropped somewhat more than 1,200 tons of bombs upon bridges and viaducts along these four lines. The results were for the moment good. Italian partisans blew up the viaduct on the Piedicolle line between Gorizia and Jesuice, and this feat, joined with the bombing, temporarily put a stop to all through railway traffic between Northern Italy and Austria and Yugoslavia.

With the need to economize his strength and to reinforce his left flank against the full development of the Eighth Army’s attack, Kesselring withdrew his forces into positions in the right and central sectors of the ‘Gothic Line’. Now was the time to strike, and in the early morning of 13th September General Alexander launched the second half of his two-fold attack. The Fifth Army joined battle in the centre sector of the ‘Gothic Line’, while the Eighth Army moved against the Coriano Ridge, and there began a week of the heaviest fighting that either army had experienced. The demands for close air support increased daily, and the efforts of the Desert Air Force to supply it reached their peak on 18th September when the Eighth Army was held up by the heavily defended feature known as the Fortunata Ridge. This had to be taken before Rimini could be invested. From 0745 hours until the assault went in, Kittyhawks and Spitfire bombers maintained their attacks on guns, mortars, trenches and strong points along the ridge. These vigorous methods, combined with the elan of the army, achieved success. On the 19th and 20th the remnants of the Germans withdrew from the feature and the Allies entered Rimini.

All this time the Po bridges, always major targets, received constant attention in spite of periods of bad weather, and the railway bridges at Torre Beretti, Casale Monferrato and Chivasso were all cut. As the bridge at Ferrara was in a similar condition because of the attacks by the strategic bombers, no trains were able to cross the river at any point between Turin and the sea. Coastal Air Force was also busy and, on 8th September, flying with squadrons of the Balkan Air Force, sank with rockets the 51,000 tons Italian liner Rex at Capodistria, thus preventing her from being used as a block-ship in Trieste harbour.

During this third week of September, the situation in the south of France was so satisfactory that the American Tactical Air Command returned to Italy to assume, under the name of XII Fighter Command, control of operations in close support of the Fifth Army. On 20th September the Desert Air Force went back to the Eighth Army and the eastern sector of the front, and on the 25th the Headquarters of the Mediterranean Allied Tactical Air Forces were once again side by side with those of Alexander.

On 21st September, the day Rimini fell to the Eighth Army, the Fifth drove a gap thirty miles wide in the central defences of the ‘Gothic Line’ and were soon pushing forward against weakening resistance. By the end of the month, with the capture of Monte La Battaglia, seven and a half miles north of Palazzuola, Firenzuola and the Futa Pass, the ‘Line had been overrun except for a few places in the western sector. The nature of the country dictated that of the air support which was mainly directed against road and railway communications and dumps of all sorts to the north of the battle area. Enemy headquarters, gun positions, troops and defended positions were also successfully attacked by the Thunderbolts of XII Fighter Command. In the last week of September Tactical Command’s medium bombers scored heavily by sinking the cruiser Taranto in Spezia harbour. Seventy-two 1,000-lb. bombs were dropped by twenty-seven United States Mitchells, hits being made on the bows, midships and stern, and when the bombers left, not only was the Taranto well aflame, but an 8,000-ton vessel anchored alongside had also been sunk.

For the next six months mud ruled the Italian front. Through the weeks of September, that versatile month which can be equally faithful to both summer and winter, the diminishing total of air sorties showed that, for the year 1944, she favoured winter. The rains began early and bad weather was soon cancelling air operations of all kinds. By October the armies were bogged and the airfields transformed into lakes. Nevertheless, small gains continued to be

made and consolidated, counter-attacks to be repulsed, and weary battalions regrouped and rested. The enemy was allowed no rest or respite either from the ground or from the air. The interdiction programme was as strong and continuous as the weather would allow, and German wheeled traffic along Route 9 was always liable, without warning, to become the target of Allied fighters and bombers slipping through the scudding clouds. Kesselring himself discovered this to his cost when, early in October, he was wounded in an air attack and had for some weeks to hand over his command to General von Vietinghoff of the Tenth Army. By the end of December he was fit enough to return, when he found little change in the general situation. Allied gains varied from five miles in the west to twenty miles in the centre, and from thirty to forty miles on the eastern flank. Bologna still lay just beyond Alexander’s grasp, but Faenza had fallen and the River Lamone formed the eastern boundary of the defence.

The Army Chiefs and their Corps Commanders had for some time been provided with small mobile flights of Auster aircraft flown and maintained by the Royal Air Force. Not only did these light aircraft, carrying distinguished and other passengers, perform an uncounted number of journeys between the various headquarters, they frequently crossed the lines with army officers in the passenger’s seat equipped with field-glasses and a great determination to see the progress of the battle. Those who flew these Austers were undergoing a period of rest from supposedly more perilous flying duties. ‘On arriving at Headquarters, V Corps’, reports Flying Officer K. H. Salt, a New Zealand pilot ‘resting’ after a tour of duty flying Spitfires, ‘I found the landing strip, barely 300 yards long, situated in the gravel bed of the dried-up Rubicon, near Rimini, with our tents pitched on an island beside the landing area. Here I had to adapt myself to the strange business of flying with the right hand on the throttle and the left on the stick, a passenger seated alongside, and a stream at one end of the strip and a bank at the other, with a squadron of tanks dotted about on either side. A couple of nights later a long-range gun lobbed a few shells along the river valley, and as the piercing whine of each shell drew nearer, I felt a nostalgic yearning for a nice wide runway, guaranteed 1,200 yards long, to land my stable Spitfire on and then head for a comfortable mess’. Conditions were hardly better when Rimini was passed. Dried-up river beds gave place to tiny rectangular fields, all bounded by fruit trees and high spreading grape vines, which were barely wide enough to land in and rarely long enough. ‘As there was little time to prepare a field during the advance, we generally had to search for the longest available field

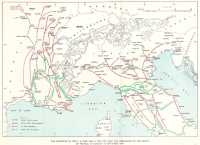

The campaign in Italy, 8 June 1944–2 May 1945 and the liberation of the South of France, 15 August–12 September 1944

facing the prevailing wind, land in it and chop down the trees at either end, and fill in the odd ditch.’ One such was easily distinguished from the air and on the ground by a row of six dead oxen, ‘whose presence became increasingly obvious despite the efforts of the sanitary squad to burn them’. A road near the River Senio was the best landing strip of all until one of the Auster pilots landed on the back of a lorry driven by a Pole who had gone astray. The passenger, who was the Deputy Supreme Commander, ‘escaped with minor injuries’.

Such were the contretemps experienced by a small but most useful body of men who, in Italy as well as in France, Burma and all other fronts, provided a swift means of transport and observation of great use to those directing the battle.

The Mediterranean Allied Strategic Air Force, although an integral part of the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces, played a role in the conduct of the war which was by no means bounded by Italy or the Italian front. It was, in effect, the heavy bomber force of the Southern Front and was made up of two sections, the United States Fifteenth Air Force and No. 205 Group, Royal Air Force, its day and its night bomber force respectively. In numbers, the day bombers by far exceeded the night bombers, for whereas, before the war was over, the Fifteenth Air Force comprised some eighty-five heavy bomber squadrons of Liberators and Fortresses and a further twenty-two squadrons of long-range escort fighters, mostly twin-engined Lockheed Lightnings (P.38’s) and single-engined Mustangs (P.51’s), No. 205 Group consisted of some six Wellington squadrons and three heavier squadrons of Liberators and Halifax aircraft.

By April, 1944, this powerful force, based on the dusty airfields round Foggia, had got into its stride, and by June was striking blows at railway communications in south-east Europe, their aim being to aid Russian military operations against Rumania. With the cutting of the main enemy supply line through Lwow, all traffic from Germany to the Rumanian front had to pass through Budapest and from there move to the frontier along three routes, via Oradea, Arad and Turnu Severin. All three were vulnerable and all three were attacked. The most remarkable of these assaults took place on 2nd June, when a force of United States Fortresses, escorted by long-range Mustangs, bombed railway communications at Debrecen and flew on to an air base in Russia. From this base four days later 104 Fortresses, with their escort, attacked the Rumanian airfield of Galatz, a target chosen by the Russian High Command, and destroyed fifteen enemy aircraft on the ground and eight in the air for the loss of two of the escorting Mustangs.

Throughout the summer Austrian aircraft production centres at Wiener Neustadt were attacked by day and night, and assaults made on enemy oil production and storage, in conjunction with those carried out by Bomber Command from bases in England; these assaults became so important that, by the autumn of 1944, they took priority over all others. The general policy, aimed at on all fronts but not consistently achieved, was that the American heavy bombers with escorting long-range fighters should attack by day, and the Royal Air Force by night, and alone. The American Fifteenth Air Force, with its Fortresses and Liberators, escorted by Mustangs and Lightnings, dropped many tons of bombs in daylight on to the refineries at Ploesti in Rumania, on Budapest, Komarom, Gyor and Petfurdo in Hungary, on Belgrade, Sisak, Osijek, and Brod in Yugoslavia, and on Trieste in Italy, while No. 205 Group, with its Wellingtons and Liberators, continued the assaults during darkness.

The enemy defences varied. Those surrounding oil targets were very strong. On the night of 9th/10th August, for example, an attack was made on the Ploesti oilfield. One of the Wellingtons taking part in it was ‘B for Baker’ of No. 37 Squadron based on Tortorella, one of the Foggia group of airfields. In bright moonlight it was approaching the target when ‘a blue searchlight’, records Warrant Officer J. Killoran, the wireless operator, ‘flickered and caught us’. More searchlights found the Wellington and then came the flak. ‘I could see’, he says, ‘all kinds of pink, blue and green lights flashing round us. I could feel the aircraft shudder as the bursts came closer. ... Small points of light appeared along the fuselage’. A moment later the rear gunner was wounded, the port engine smashed and ‘B for Baker’ ‘certainly a pepper-pot’ began to plunge earthward. The bombs were jettisoned and a duel then fought between the wounded rear gunner and a Ju. 88, while the Wellington climbed laboriously to 4,000 feet on one engine. After three attacks the night fighter fell steeply away. Killoran dragged the gunner from the turret and the pilot set course for Turkey, it being impossible to return over the Alps. On reaching the neighbourhood of Istanbul, the navigation lights were turned on and this was a signal for heavy fire from the Turkish batteries, which destroyed the other engine. The crew, the wounded air gunner among them, took to their parachutes and were picked up by shepherds, who took them, the wounded air gunner in an ox-cart, to Istanbul. Here they were hospitably entertained and made ‘gloriously inebriated’ before being sent back to Foggia. In ten days they were again flying against the enemy.

An important feature of the campaign waged by the Mediterranean Strategic Bomber Force was the sustained assaults made on the Hungarian and Rumanian railway systems. These were of special value to the Germans who, by the early summer of 1944, had been deprived by the Russians of the Lwow–Cernauti railway. They were, however, not only insufficient in themselves but also under constant and increasing air attack. The alternative route to them was the River Danube, which flows for 1,500 miles through Germany, Austria, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Rumania and Bulgaria, and could carry 10,000 tons of material daily. This great river was the natural link between the Third Reich and the grain lands of Hungary, a link with Turkey, a strategic route to the Russian Front, and above all a life-line connecting the Reich with the Rumanian oilfields. One Rhine-type barge could transport a load equivalent to that carried by a hundred 10-ton railway wagons, and hundreds did so. It was estimated that, in 1942, approximately 8,000,000 tons of materials reached Germany by means of the Danube waterway alone. This traffic was gradually increased until, by the middle of March, 1944, not only had the major part of all oil products coming from Rumania been diverted from the railways, but the river traffic was 200 per cent. more intense than the rail. Even the temporary stoppage of such a flow would have a far-reaching effect upon the enemy’s continued capacity to make war, and Mediterranean Allied Air Forces Headquarters laid plans to make the interruption as complete as possible.

At the beginning of April, 1944, No. 205 Group, working closely with naval specialists, opened its offensive against the River Danube, and on the night of the 8th/9th three Liberators and nineteen Wellingtons, passing low along the river near Belgrade, dropped the first forty mines. In ten days this total had risen to 177. During May a further 354 mines were dropped, and although no sorties were flown in June, the resumption of the offensive on the night of 1st/2nd July saw the biggest mission of the operation when sixteen Liberators and fifty-three Wellingtons dropped a total of 192 mines. On the following night a further 60 were added.

At first GARDENING missions—the code word was, it will be noted, the same as that used by Bomber and Coastal Commands for the same kind of operation—were flown only in moon periods because GARDENERS had to fly at no more than 200 feet, and heights of forty and fifty feet were often reported. Later on, however, the use of Pathfinder aircraft and of illumination by flares made it possible to operate over any part of the river during any period of the month. Further missions in July, August and September added a total of 555 mines to those already dropped, and the final mission

of the Operation took place on the night of 4th/5th October when four Liberators and eighteen Wellingtons laid a total of fifty-eight mines in areas of the river in Hungary, west of Budapest, north of Gyor and east of Esztergom. The operation had lasted for a little over six months, and during that time some 1,382 mines had been dropped in eighteen attacks by the Liberators and Wellingtons of No. 205 Group.

In support of them flew the night fighter Beaufighters of Mediterranean Allied Coastal Air Force to attack river craft with cannon-fire, or suitable targets on nearby roads and railways. On the night of 29th/30th June, intruders of No. 255 Squadron found a group of barges north of Slankamen. The cannon shells poured into them and the 200-foot barges, freighted with oil, ‘mushroomed up in vivid red and orange flashes’. During these intruder operations eight large oil barges and their cargoes were destroyed and 102 other vessels damaged, a total of some 100,000 tons of shipping.

The first mining attacks took the Germans by surprise, and it was not until the middle of August that they were able to produce counter-measures. A de-magnetizing station was erected at Ruschuk, and a squadron of minesweeping Junkers 52’s fitted with mine detonating rings began to operate. A Serbian tug-boat, the Jug Bogdan, was taken over and modified as a minesweeper, but her crew, consisting of a captain, who directed operations from the safety of the bank, and seven naval ratings, all of whom were terrified by their new and dangerous duties, did not succeed in detonating a single mine.

As No. 205 Group warmed to its work, several vessels were sunk in the busy stretch of the Danube between Giurgiu and Bratislava and traffic brought to a stand-still. By May, coal traffic was virtually suspended, the ports became increasingly overcrowded, storage facilities were equally strained, and barges were piling up at Regensburg awaiting a tow to Budapest. On 1st June, listeners in London and Foggia were gratified to hear the Hungarian wireless warn all shipping between Goenuye and Piszke to remain where it was until further notice. Barges loaded at Svishtov at the end of April were still there on 10th June. Photographic reconnaissance showed the Begej canal between Titel and Jecka to be full of inactive barges, while more than a hundred were dispersed along the banks of the Danube and Sava. The lugubrious Captain Mossel recorded no more than the truth when he wrote in his diary in June, 1944: ‘The enemy has mined the Danube systematically and has achieved his object of upsetting the traffic in the Balkans. During the moon period it was discovered that the main point of the mining operations was that part of the river where there were distinct banks visible and therefore

not in inundated areas. We have no reports of the disturbing of the Danube during May. Nevertheless I am under the impression that the entire length of the river was only free for ship traffic for a very few days. The enemy sets mines which are very difficult to sweep and are not to be swept by a few mine-detecting aircraft. This explains the loss of shipping in sections which have been swept for days without success. The crews of the Danube vessels are creating difficulty. Frequently they desert, but it is intended to out-manoeuvre this by militarizing them. Finally it must be stated that the enemy by the mining of the Danube harms us very considerably and that at present we are unable to cope with the situation.’

In July he was even gloomier. ‘The enemy’, he writes, ‘has mined the Danube according to plan. Thirty-nine vessels have been sunk from the beginning of May to the middle of June, and forty-two damaged by these weapons. The most effective means for mine-sweeping are the mine-detecting aircraft, but unfortunately they are few in number owing to lack of fuel. It is therefore not possible to clear the Danube of mines with the means we have at hand, and the position regarding shipping is badly affected in consequence.’

There can be no doubt as to the outstanding success of these GARDENING operations. The broad result of them was that between April and August, 1944, the volume of traffic on the Danube was reduced by some 60 to 70 per cent. The enemy was forced to deploy, along a considerable length of the river, very great quantities of antiaircraft equipment, including balloons and guns as well as trained crews to man them. Skilled minesweeping crews, both naval and air, were diverted to the Danube at a time when their services could ill be spared from home waters. Finally—and most important of all, perhaps—considerable aid was given to the Russian Forces in their westward drive, for the transport of German reinforcements to the Eastern Front suffered long delays.

In the early days of 1945 it became evident that holding operations in Italy were all that were feasible until the advent of spring made it possible to resume the offensive on a grand scale. Close air support was therefore reduced to the minimum required for strictly local operations and the main objective of the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces became the reduction of the enemy’s fighting capacity. This task required the major disruption of his lines of communication so that he would be denied freedom of movement and access to his sources of supply. Above all, those of his divisions which remained in Italy must be cut off, must be unable to reinforce each other and must be incapable of carrying out a sustained operation. The disruption of Italian communications had long been a matter of

great importance, but it now put all else in the shade. Action against the frontier railway routes was given priority. XXII Tactical Air Command, a new formation made up of the short-lived XII Fighter Command and former units of the old XII Tactical Air Command returned from the South of France, was directed against the Brenner Pass while Desert Air Force bombers attacked the nearer stretches of the north-east routes. Strategic Air Force heavy bombers were also available from time to time to add weight to the onslaught which was occasionally turned against targets in the valley of the Po.

In spite of twelve days when the Brenner Pass, across which ran the rail and road route connecting Verona with Innsbruck, was shrouded in thick cloud, 923 sorties were flown in January, 1945, and 1,725 tons of bombs dropped by the Tactical medium bombers. Avisio, Rovereto and San Michele were the main targets, but the loop line from Trento to Bassano was also bombed. Strategic Air Force heavy bombers dropped a further 776 tons, 460 of which were directed at the Verona marshalling yards. During that month the route was made impassable for fifteen days and probably for another five. Photographic reconnaissance showed that there was little rail activity south of Trento. Better weather in February produced better results. One thousand seven hundred and sixty-one tons of bombs from the medium bombers and 3,000 from the heavies, together with 200 attacks, involving 1,117 sorties by fighter-bombers so devastated this route that at no time was it open to continuous through traffic. On 26th February, for example, the Brenner route was blocked at nine places. By then German stocks of petrol had been so much reduced that any considerable movement by road of troops or supplies was out of the question. March saw the completion of the operation with the highest level of interdiction yet achieved—ten to twelve blocks at a time on the route were common, and on one occasion there were fifteen on the vital stretch between Verona and BolzaNo. The Brenner route was no longer a line but a series of disconnected stretches of track. Even the neutral Swiss were impressed, for they hastened to conclude an agreement with the Allies which laid an embargo on the passage of war materials through their country between Italy and the Reich. The blockade of Northern Italy was now virtually complete.

A similar and equally effective havoc was wrought upon the Postumia, Tarvisio and Piedicolle railway routes in the north-eastern frontier zone. The targets of the Tactical medium bombers were three bridges and diversions in the Livenza, Brenta and Tagliamento river zones. It was, however, with the Desert Air Force that the task lay of blocking the eastern approaches from Cremona to

Chiusaforte on the Tarvisio route, Gorizia to Canale d’Isonzo on the Piedicolle route and the longer southerly stretch, Padua to Sesana, on the Postumia route. Its efforts, together with 620 tons of bombs from the Strategic heavy bombers, which were mainly against the marshalling yards at Udine, denied the enemy all through rail traffic in and out of north-east Italy during January. In spite of greatly increased attempts at repair made by the enemy, which enabled through traffic for a few days at the beginning of February, by the end of that month the interdiction was again complete and remained so throughout March.

Dumps and installations, though not quite so high on the list, were also essential targets. As the first three months of the year drew to a close the onslaught upon them in all areas mounted steadily, the main targets being dumps of fuel and ammunition. Vessels plying along such stretches of the Adriatic coast as were still under German control were also bombed. The most satisfactory of these operations was that to which the code name BOWLER was given. Its choice, by Air Vice-Marshal Foster, signified to the pilots taking part the type of head-gear that lay in store for him, and probably them, if any of the monuments of Venice, in the harbour of which the vessels to be attacked were lying, were damaged. Great accuracy allayed the Air Vice-Marshal’s apprehensions. The S.S. Otto Leonhardt was severely damaged and a number of barges, a tanker and a torpedo boat were set on fire. The Venetians crowded the roofs of their venerable city to watch the free and fiery spettacolo. The air forces had done their utmost to ensure that the enemy would be as weak as possible when the time came to launch the final offensive of all.

On 23rd March, 1945, Field Marshal Kesselring took leave of Army Group ‘C’ and left Italy to assume command of the Western Front. His successor, General von Vietinghoff, was promoted from the command of the Tenth Army. It is difficult to understand why Army Group ‘C’ should, at this time, still have been the best manned and best equipped in the German Army, having some 200 tanks, almost as many as there were on the whole Western Front. Possibly there still remained visions of a Southern Redoubt amongst the crumbling ruins of the ‘Thousand Year Reich’. Whatever the reason, Alexander’s armies in Italy, comprising seventeen divisions, four Italian combat groups, six armoured and four infantry brigades, were faced by twenty-three German and four Italian divisions. Of these, sixteen German divisions and one Italian held the Apennine-Senio Line with two German mobile divisions in reserve, the remainder of the enemy’s forces being stationed in the

north-east and north-west where Yugoslav Partisan activities in the neighbourhood of Trieste and Allied movements on the other side of the Alps held them in situ.

On the morning of 9th April the number of Allied aircraft above the front line was hardly large enough to cause the enemy to look upwards. It passed quietly enough until shortly before 1400 hours, when the deluge opened. Two hundred and thirty-four medium bombers and 740 fighter-bombers of the Tactical Air Force, and 825 heavy bombers of Strategic Air Force, went into the attack. A carpet of 1,692 tons of bombs, laid by the heavy bombers, covered the defended areas west and south-west of Lugo; and the medium bombers saturated, with 24,000 twenty-pound incendiaries, gun positions to the east and south-east of Imola across the Rimini/Bologna highway. Immediately these carpets had been laid the fighter-bombers came screaming from the sky down upon special targets such as command posts, divisional headquarters, gun positions, occupied buildings, battalion and company headquarters, and threw into confusion the enemy’s troops in the forward areas. The work was then taken up by the guns, and in the evening the Eighth Army’s V Corps and II Polish Corps attacked across the River Senio. The first objectives were quickly captured and the New Zealand Division were able to cross the Senio without a single casualty either killed, wounded or prisoner.

‘We watched from the air’, says Flying Officer Salt, who was above the battlefield that day with an army observer, ‘and saw a dense mass of dust arising from the heart of the defensive positions across the Senio. Stretching right back to the coast was a double line of white smoke flares, the final two just on our side of the river being orange, with Lugo a mile or so beyond. As we cruised beneath the bomber stream we suddenly saw a carpet of dust almost below us and hastily steered clear. That evening we again watched the terrific offensive from the air. Flame-throwers of the 8th Indian and 2nd New Zealand Divisions, leaning against the Senio stop-banks, poured a grim barrage of flame at the hapless enemy in dug-outs. All along the fine little flashes of flame flickered through the evening haze. The mighty roar of the barrage ceased abruptly at regular intervals for just four minutes, when fighters swept in to strafe the German positions and dive-bombers hurled bombs at their vital points. It was awe-inspiring enough to watch; no wonder the wretched prisoners next day asked in a stupified daze: “What have we done to deserve this?”‘ That night No. 205 Group Liberators pressed on with the business, sometimes only 2,000 yards in front of the troops of the Eighth Army, their targets being marked by shells emitting

red smoke. On the next day Lugo was captured and by the 17th, with air support which ceased neither by day nor night, Argenta had been overrun and the Eighth Army was about to debouch through the gap on to Ferrara. The weather was now dry, the cloying mud of the winter had disappeared, and the movements of armies could now be made without difficulty or delay.

The Fifth Army opened its attack in the centre sector on 14th April, and as on the eastern flank it was heralded by an intense air offensive. The troops had first to burst their way out of the mountains south of Bologna before any great advance could be made, and this they did laboriously ridge by ridge while XXII Tactical Air Command and the American heavy bombers of the Strategic Air Force gave all the support that weather and cloud conditions would allow. Bologna fell on 21st April, the leading troops of the Fifth and the Eighth Armies entering it simultaneously from different directions. By the evening of 22nd April the Fifth Army had reached the Po at San Benedetto and by the next day the Eighth Army was in strength on either side of Ferrara. Between them they had trapped and immobilized many thousands of German troops. Those in the east belonging to the Tenth German Army tried desperately to cross the Po, but, pursued by Allied armour and harried by the air forces, they were obliged to abandon what remained of their equipment and transport south of the river. Such as won to the further bank were too weak in guns and armour to make a stand on the Adige River, and began to straggle along the weary road to the Alps. The situation of the enemy’s forces in the west was no better. Orders to abandon their positions were issued but arrived too late; the speed of the Allied advance had cut most of the escape routes leading north. By the end of April there remained only four German divisions which bore any resemblance to fighting formations, and they were in no position to defend the Southern Redoubt. On 21st April, after the fall of Bologna, the speed and amplitude of the Allied advance is best measured by the list of towns captured and the date on which they fell; on the 23rd Modena, on the 24th Ferrara and Mantua, on the 25th Verona, Spezia and Parma, on the 27th Piacenza and Genoa, on the 29th Padua, on the 30th Turin, and in the first two days of May, Cremona, Venice, Milan and Udine. One course alone was open to von Vietinghoff—unconditional surrender. On 24th April the instrument was signed at Field Marshal Alexander’s Headquarters in the royal palace at Caserta, the cease-fire being ordered for the 2nd May.

That the share of the air forces in the achievement of this victory was great is beyond question. ‘I don’t suppose’, averred one army

commander, ‘that there has ever been a campaign where the army has asked so much of the Royal Air Force or where the Royal Air Force has given such whole-hearted and devastating support, always in close proximity to our men’. The main effort was directed against the tortuous communications upon which the enemy had to rely to maintain his fighting strength. It was a tedious and difficult offensive to wage but in the end it was decisive. The speed with which calls for close support were answered also greatly heartened the troops whose valour had been put to so many and to such searching tests. The fulfilment of the interdiction programme and the unrelenting manner in which the fighter and fighter-bomber pilots pursued their tasks eventually immobilized the enemy, who became, with every day that passed, more and more like a man, strong-armed and vigorous, whose feet are firmly held in an unbreakable trap. As long as his strength endures he may continue to strike with his fists, but he cannot move forward or back and must in the end surrender or perish.

General von Vietinghoff has left no doubt as to his views on the performance of the Allied fighter-bombers. ‘They hindered’, he said, ‘essential movement, tanks could not move, their very presence over the battlefield paralysed movement’. He also ruefully appreciated the success of the air attacks on focal points carried out at the opening of the battle. ‘The smashing of all communications was especially disastrous. Thereafter orders failed to come through at all or failed to come through at the right time. In any case the command was not able to keep itself informed of the situation at the front so that its own decisions and orders came, for the most part, too late.’

General von Senger, who commanded XIV Corps of the German Fourteenth Army, was equally forthright. ‘The effect of Allied air attacks on the frontier route of Italy’ he said, ‘made the fuel and ammunition situation very critical. It was the bombing of the Po crossings that finished us. We could have withdrawn successfully with normal rearguard action despite the heavy pressure, but owing to the destruction of the ferries and river crossings we lost all our equipment. North of the river we were no longer an Army.’

The struggle had been long and hard, for both adversaries had displayed the highest resolution and valour. Moreover, they had been very evenly matched and Alexander had never had that numerical superiority in the field which, in modern times at least, is regarded as necessary if the attacking army is to achieve success. Nor had his victory been the result of the transfer from Italy by the enemy of divisions to another front. On the contrary, Kesselring had been reinforced more than once. In the Allied Mediterranean

Air Forces, however, the Allies possessed a weapon which not only made defeat impossible but victory certain. Throughout the long campaign, begun in a July dawn within sight of Etna and ending on a May noontide within sight of the Alps, the Luftwaffe had been unable to defend itself, much less to dominate the field of battle. Had it done so, had the Allies not applied from the outset that simple formula, ‘Army plus Air Force produces victory’, the results would have been far otherwise, for the country in which the Italian campaigns were fought everywhere favoured the defence. If Kesselring had possessed freedom of movement and communications which were safe and secure with all that that implies, he must have held at bay, and perhaps defeated, armies many times larger than any commanded by Alexander. As it was he was unable to manoeuvre with that freedom and speed which his carefully laid and skilful plans required, and his men had only too often to fight with eyes turned to the fighter and the bomber in the skies rather than to the bayonets advancing up the hillside or across the plain. However resolute and well-trained troops may be, they cannot maintain the fight against opposites of equal merit when behind their lines oxen have had to be harnessed to lorries, for whose tanks fuel has been unobtainable for weeks, and when a thousand cigarettes is the reward of any man fortunate enough to bring back a tin of petrol from patrol.

Such was the condition of the German armies in Italy when the last blows fell.