Chapter 13: Over the Rhine to the Elbe

The operations which Montgomery had been planning when the German counter-attack in the Ardennes was launched on 16th December, 1944, took place towards the end of January. They were known as VERITABLE and GRENADE and the air cover for them was supplied by No. 84 Group with the co-operation of XXIX Tactical Air Command of the United States Army, temporarily under Coningham’s control. It was the task of No. 83 Group to maintain the programme of interdiction beyond the Rhine in the enemy’s rear areas and to deal with the Luftwaffe should it be disposed to show itself. While this Group thus held the outer ring, No. 84 Group and the Americans operated over the battlefield itself. The sodden state of the ground forced the Army to proceed slowly and methodically, and this put a somewhat greater burden on the Tactical Air Force than they had expected. Nevertheless they were able to fulfil all their commitments. No. 83 Group made unnumbered assaults on all German vehicles that could be seen and bombed points in the Siegfried Line; but the weather was poor and not until 14th February was No. 84 Group able to use its full strength. XXX Corps was attacking a number of defended positions in the hotly contested area to the north of Cleve Forest, and its forward control posts on the ground directed the aircraft of the ‘cab ranks’ and the medium bombers on to any counter-attack which showed signs of developing.

All transport between the Meuse and the Rhine as far south as Rheinberg was kept at a standstill and even motor cyclists were chased from the roads. On 21st February, No. 35 Wing flew a record number of sorties, among their achievements being a very successful strike against shipping in the Zuider Zee. The results achieved that day would have been entirely satisfactory had it not been for an unfortunate incident at Goch, which received ninety-six bombs dropped by No. 320 (Dutch Naval) Squadron of No. 2 Group, then engaged in a daylight attack on targets in the Weeze area. The leader of the formation realized his mistake when the bombs were still in the air but he was unable to prevent some of his squadron

from following his example. The mistake most unhappily cost the lives of a number of men belonging to the 51st (Highland) Division, then in the town.

Meanwhile, No. 83 Group was penetrating deeply into Germany. Railway traffic north of the Ruhr was the main target, together with transport on the roads, and the claims of locomotives or vehicles destroyed rose to a new height. The general demoralization of the Germans, and the repeated assurances made by their generals after the war was over that our air power was overwhelming, are proof that the damage done was very great. The losses of the Group rose, for the enemy had made his anti-aircraft defence more mobile and spread it more widely. Moreover, the Luftwaffe put in a tardy appearance, more than one Messerschmitt 262, the new jet fighter, being encountered. This aircraft was a menace, and could be satisfactorily dealt with only when it was on the ground or when taking off and landing. For this purpose it became necessary to maintain continuous patrols above the airfields on which its squadrons were based. Fortunately these were few in number, for this jet fighter needed a concrete runway of about 1,500 yards. It could not therefore be used to any great extent and this was one excellent reason why it was not seen very often in the battle areas. When it did appear, the German tactical commanders made the worst possible use of it; for instead of directing it against the Royal Air Force or the American Air Force, it was used on unimportant targets on the ground and also to attack troops and vehicles.

On 22nd February, 1945, at 1300 hours, operation CLARION was launched. It was an especially concentrated effort to wipe out in the space of twenty-four hours all means of transport still possessed by the enemy. Nearly 9,000 aircraft, from bases in England, France, Holland, Belgium and Italy delivered an onslaught over a quarter million square miles of Germany. Railroad targets, from signal boxes to marshalling yards, were attacked, as well as canal locks, bridges and level crossings, and vehicles of all kinds on the road or in garages and depots.

Meanwhile Coningham was engaged, on the orders of the Supreme Commander, in producing a plan by which both the Tactical and Strategic Air Forces were to take part in the next and greatest operation of the campaign—the crossing of the Rhine. The lesson of Arnhem had been learnt and to the Commander of the Tactical Air Force most concerned had been given the all-important duty of designing the operation and any of a similar nature which might prove necessary. While he was engaged on this task, a lull ensued both on the ground and in the air, caused partly by the weather, but

for the most part by the need to build up the forces of what all knew would be, if it were successful, the last major enterprise of the war.

The tasks of the air forces were five in number. First came the most important of all and that which they had had most practice in fulfilling—the winning of dominance in the air, especially over the areas of the assault and of the zones on which airborne troops would land. Secondly, special attention was to be paid to anti-aircraft defences which, to borrow a euphemism used by the Army, were to be neutralized: that is, either destroyed by rockets, cannon fire and bombs, or prevented from coming into action. Thirdly, the British and American transport aircraft carrying parachute troops were to be given fighter protection. Fourthly, close support was to be provided for all troops engaged on the operation. Lastly, any movement of the enemy in the area of battle and towards it was to be prevented.

It was decided that the winning of the air battle should be entrusted to Nos. 83 and 84 Groups and, south of the River Lippe, to XXIX Tactical Air Command of the United States Air Force. They were to prevent the appearance in the sky of the Luftwaffe. To aid them in this task all airfields within fighter range of the bridgehead to be established across the Rhine were to be bombed both beforehand and during ‘D Day’. Medium and fighter-bombers would assist the guns on the ground to deal with the anti-aircraft guns of the enemy, of which about 1,000 light and heavy had been discovered in the Bocholt-Brunen area. The escorting of the aircraft carrying the airborne troops was to be the responsibility of Fighter Command of the Royal Air Force, and of the United States Ninth Air Force, and close support was to be given by heavy bombers and fighter-bombers, particularly at Wesel, the main objective of the British Second Army, which was to be subjected to two attacks by Bomber Command. Any requests for air support from our advanced formations were to be met by fighters of the Second Tactical Air Force and the fighters of XXIX Tactical Air Command. Finally, enemy movement in the battle area or towards it was to be prevented by the bombing of specially chosen centres of communication.

The Twenty-First Army Group, not unnaturally, expected the opposition to be very heavy, for would not the armies of the Wehrmacht be defending the sacred soil of the Fatherland? They therefore urged strongly that the bombing programme should begin several days before ‘D Day’, which had been fixed for 24th March. To do so might, indeed would, sacrifice the element of surprise; but, so the Army Group Commander argued, that loss was inevitable given the size and weight of the proposed operation. After much

discussion, Tedder chose twenty-six targets in the Second Army area, three to be attacked by Bomber Command and the remainder by the Americans and No. 2 Group of the Second Tactical Air Force.

There remained the dispositions to be made for the use of airborne troops. By then these had risen to the dignity of an Army, under the command of General Brereton with Lieutenant-General R. N. Gale as his deputy. A Combined Command Post was set up at the Main Headquarters at Maison Lafitte, just outside Paris, and the closest liaison established between the British and the Americans. At long last, it seemed, that for the crossing of the Rhine, advantage would be taken of the experience acquired in campaigns fought in North Africa, Sicily, Normandy and Holland. This time the planners were determined that the new airborne army should be used to the fullest effect and that the minimum should be left to chance. A striking innovation was introduced. The airborne troops, of which the British element was the 6th Airborne Division, were to land, not before the Rhine had been crossed by the army on the ground, but several hours after. By these means, though casualties might occur at the moment of the drop and the landing of the gliders, tactical surprise would, it was hoped, be achieved. On one point Brereton was adamant. The airborne divisions taking part in the attack would be taken to their destination in one lift, and the airborne supplies, which they would need before being relieved by the advanced guards of Twenty-First Army Group, would be dropped, not twelve or twenty-four hours after the landing, but that same evening six hours at the most from the time the first parachute soldier touched ground. It will be perceived that the lessons of Arnhem had been well learnt.

Nos. 38 and 46 Groups of the Royal Air Force provided between them 440 aircraft and gliders to carry the air landing brigades, and the 52nd Wing of IX Troop Carrier Command 243 aircraft to carry the British and Polish parachute troops. Their orders were to seize the Diersfordter Wald, which overlooked the Rhine north of Wesel, the village of Hamminkeln and the crossings of the River Ijssel. The landing would begin at 1000 hours, four hours after the Rhine had been crossed by the leading elements of Twenty-First Army Group, the 1st Commando Brigade.

Such were the plans and, while they were still under review, the preliminary process of launching heavy attacks from the air on suitable targets was pursued with great vigour. The first move seemed to some to be somewhat irrelevant to the main object. The Allied Air Forces were set on to ensure the interdiction of the Ruhr. All enemy troops or supplies were to be prevented from moving in or out of this area by the ruthless bombing of all means of

communication. More than one member of the Joint Air Staff at Supreme Headquarters expressed opinion that the value of attacks such as these was, so to speak, more economic than military. Tedder, however, was of the opposite view and held that a programme of interdiction, provided that it was supported by heavy assaults on the railway centres in the Ruhr itself, would be of immediate value in the forthcoming battle. His instinct and his tactical sense were alike correct. The nearest German reinforcements available to the watchers on the Rhine were Model’s Army Group ‘B’, made up of the Fifteenth Army and the Fifth Panzer Army, comprising in all some twenty-one divisions. They must be prevented from moving.

To do so special attention had to be paid to bridges and communications. Of these the most important were the viaducts at Bielefeld, Altenbeken and Arnsberg, which carried the main traffic lines from the Ruhr to the rest of Germany. Between 22nd February and 20th March the Bielefeld viaduct was attacked seven times, four times by Bomber Command and thrice by the United States Eighth Air Force. Success was achieved on 14th March when a 22,000-lb. bomb shattered two of its spans, and thirteen 12,000-lb. bombs wrecked the by-pass which the Germans had been quick to build when attacks on the viaducts had first been made earlier in the campaign. Four days before ‘D Day’ for the Rhine crossing, ten bridges had been destroyed, five rendered impassable, and only two, those at Cölbe and Vlotho, again attacked on ‘D Day’, could, it was considered, still be used.

The attacks on the railway centres of the Ruhr were made by Bomber Command and the United States Eighth and Ninth Air Forces, assisted by the light bombers of the Second Tactical Air Force. A total of 115 were carried out, the most outstanding being that on 11th March when a force of 1,055 Lancasters, Halifaxes and Mosquitos dropped nearly 4,700 tons of bombs on Essen through 10/10th cloud. This was followed on the 12th by an even heavier attack, also by Bomber Command, on Dortmund, which received 4,851 tons. Marshalling yards, notably those at Münster, Soest, Osnabrück and Hanover, were attended to by the Americans. The medium bombers of No. 2 Group of the Second Tactical Air Force made twenty-three attacks from the 1st to the 20th March in the north of the Ruhr, mostly on the same railway centres and, in addition, on those at Rheine, Borken, Dorsten and Dülmen.

The attacks on German airfields began on 21st March and were carried out entirely by the United States Eighth Air Force based on the United Kingdom. To assist them by creating a diversion, fighter sweeps over the northern airfields were made daily by the fighter

squadrons of the Second Tactical Air Force, and on 22nd March thirty-two Tempests, taking part in one of them, shot down five out of twelve Focke Wulf 190’s, making one of their now comparatively rare appearances near the battlefield.

As ‘D Day’ drew nearer, the Strategic Air Forces attacked Münster, Rheine and other already well-bombed centres of communication. Bomber Command also destroyed two bridges at Bremen and one at Bad Oeynhausen. The fighter-bombers of the Second Tactical Air Force and of XXIX Tactical Air Command redoubled their efforts. On 21st March, Nos. 83 and 84 Groups succeeded in cutting German railway lines at forty-one places, while No. 2 Group by day attacked seventeen towns close to the Rhine and by night any transport that could be seen.

The final targets were enemy camps and barracks. These received attention mostly from the United States Eighth Air Force and No. 2 Group, which in three days made 400 sorties against twenty of them. On 21st March, five Typhoon and three Spitfire squadrons of No. 84 Group made a successful attack on a camouflaged village near Zwolle, which concealed the depot of German parachute troops, and on the same day the same squadrons scored direct hits with rockets and incendiary bombs on the headquarters of the Twenty-Fifth German Army at Bussum in Holland. On the day before ‘D Day’ itself, the 23rd, seven squadrons of Nos. 121 and 126 Wings of No. 83 Group attacked anti-aircraft positions beyond the range of the Second Army’s artillery. Throughout this period the night fighters of No. 85 Group made sure that during the hours of darkness the Luftwaffe should not be able to operate. It was so little in evidence, however, that the Group was able to claim the destruction of only two German aircraft.

Thus all was made ready for 23rd March. On that day the final blows were delivered by Bomber Command in two attacks on the little town of Wesel—which was the objective of the 1st Commando Brigade—the first attack being carried out at 1530 hours by seventy-seven Lancasters.

Hardly had the dust raised by this onslaught settled, when the orders were flashed from Twenty-First Army Group Headquarters that operations PLUNDER, FLASHPOINT and VARSITY—the crossing of the Rhine and the landing of airborne troops near the Diersfordter Wald—would take place as planned. Dusk had given place to night when the fire of the guns, which had not ceased all day, rose in crescendo. Shell after shell screamed across the broad Rhine and dense smoke soon covered the entire front of the assault. At 2235 hours Bomber Command’s main attack on Wesel began. By

then the leading elements of the 1st Commando Brigade and the 51st Highland Division were over the Rhine and on the outskirts of the doomed town, which only a few hours before had been almost obliterated. In the course of this second assault, carried out by 212 Lancasters and Mosquitos of Nos. 5 and 8 Groups, 1,100 tons of high explosive fell on Wesel, mainly on the north-west quarter. The results were overwhelming. Whole streets were blocked with confused masses of debris, all road and rail bridges on the west were shattered, and almost all resistance paralysed. The 1st Commando Brigade had no difficulty in overrunning the town, and would certainly endorse Montgomery’s message to Harris that the attack had been an invaluable factor in their success.

Meanwhile the Mosquitos of No. 2 Group were heavily engaged all that night against enemy transport opposite the Second and Ninth Army fronts, dropping in all one hundred and thirty-eight 500-lb. bombs on towns, villages and woods. At Weseke, flames gushed out of the houses and rose to the fantastic height of 1,000 feet.

Punctually at 0600 hours as planned, the British 6th Airborne Division took off from their East Anglian airfields. The ground crews of Nos. 38 and 46 Groups had made a particularly sturdy effort to put every aircraft and glider for which they were responsible into the air. So successful were they that only one glider combination failed to take off. From rendezvous above Hawkinge in Kent the great aerial fleet, escorted by fighters, set course for Brussels where it joined aircraft carrying the United States 17th Airborne Division from Continental bases. Passing over the field of Waterloo, the two armadas turned onto parallel courses to fly northwards for the Meuse. ‘From there’ records Brigadier G. K. Bourne, a passenger in one of the gliders, ‘I could see the Rhine, a silver streak, and beyond it a thick black haze for all the world like Manchester or Birmingham as seen from the air’.

Two small contretemps marred the otherwise perfect execution of the elaborate plan. The gliders and tugs arrived over the battle area seven minutes early, thus preventing the fighter-bombers of the Second Tactical Air Force from carrying out to the full their task of attacking anti-aircraft defences, and the parachute troops and gliders had to descend through air still much obscured by the dust and smoke from the bombing of Wesel, drifted by a westerly wind across the landing zones. Nevertheless, the landing of the gliders was exceedingly accurate, many touching down within twenty or thirty yards of their objective. This happy result was due, as Air Vice-Marshal Scarlett-Streatfeild, soon to lose his life in an air accident in Norway, pointed out, to the very careful training and briefing

which the crews of both tugs and gliders—of which the majority was at this late stage of the war being flown by pilots of the Royal Air Force—had been given.

About 300 gliders were damaged, more or less severely, and ten were shot down. The comparative failure of the efforts made by the Second Tactical Air Force and the United States Ninth Air Force to quell the anti-aircraft fire of the enemy was in part the cause of these casualties. The assault was begun by the medium bombers of No. 2 Group and the United States Ninth Bomber Division, who together dropped some 550 tons of 500-lb. and fragmentation bombs on chosen gun posts. None of them was hit, though the concentration of bombs round several of the batteries were good. The next phase was carried out by Typhoons, which attacked these and similar positions in the dropping zones or near them with rockets, cluster bombs and 20-mm. cannon shells. As has been explained, their activities had to be curtailed owing to the premature arrival of the 6th Airborne Division. During the landing itself there were as many as sixty Typhoons in the air over the landing zones and an average of thirty-seven remained in their neighbourhood throughout the day. The smoke and dust from Wesel made it hard for the pilots to see their targets which were, in any case, extremely small. Only one light anti-aircraft gun was directly knocked out, and the crew of one 88-mm. gun in a pit were killed by a fragmentation bomb. Many other gun positions showed signs of damage, but that was all. Subsequent statements by prisoners of war make it clear that the German gunners were not unduly perturbed by the assaults of the fighter-bombers. What filled them with dismay was the sudden arrival of the 6th Airborne Division, who appeared in thousands in the air above them.

The armed reconnaissance and close support sorties, flown by Nos. 131, 132, and 145 Wings of No. 84 Group, and, in the afternoon, by Nos. 121 and 124 Wings of No. 83 Group, also did not achieve any very great result; but the reason for this was simple. There were but few targets to attack. The enemy showed small desire to use the roads, and apart from an occasional trickle of cyclists or a lorry towing a gun, there was little at which to fire.

The close support work called for by the ‘contact cars’ of Twenty-First Army Group was carried out by No. 83 Group. These were more successful, for in this instance the targets were designated by the Army and the enemy in them were active in defence. The Typhoons were presently joined by No. 2 Group who attacked three medium gun positions south of Ijsselburg with good results. The reconnaissance missions made a valuable contribution to the success of the assault. Their photographs and signals provided targets for the artillery.

The railway viaduct at Bielefeld three days after Bomber Command’s attack of 14th March, 1945

A battered target in the path of the allied advance-Bocholt

Finally, Bomber Command, No. 2 Group, and the United States Ninth Air Force, wound up their heavy preparatory attacks by bombing Gladbeck and Sterkrade. They flew without escorts in excellent weather and caused very heavy damage. Railway lines were cut, stations wrecked and the towns themselves reduced to rubble. Two oil refineries, which were situated in the target area, were also put out of action.

Throughout this memorable day the Luftwaffe was powerless to intervene. The ring made by the British and American fighters round the troops crossing the Rhine was far too strong. Between dawn and dusk some 4,900 sorties were flown by fighters and fighter-bombers and more than 3,300 by the medium and heavy bombers.

Once past the Rhine the armies of Eisenhower were in the straight with the winning post clearly before them. Between the 25th and 29th March the expansion of the bridge-head made steady progress. By the 26th the Germans were showing signs of collapse and there was for once a larger number of targets available for assault. Convoys of motor transport were discovered seeking to escape from the neighbourhood of the battlefield, and the total number of sorties flown that day by the fighter-bombers of the Second Tactical Air Force reached 671. One hundred and thirty-nine vehicles, it was claimed, had been destroyed. No. 2 Group went out against enemy artillery, and by the evening of the 25th, Second Army was able to report that only two German batteries were still firing into Rees, which was then under attack. Once more the Luftwaffe was almost invisible. It was perhaps recovering from an attempt to show fight on the previous day when it had lost twelve Focke-Wulf 190’s to Royal Air Force Tempests and Spitfires. Anti-aircraft fire was now to be feared more than Focke-Wulfs or even Messerschmitt 262’s. On 1st April Broadhurst lost twenty-six fighters from this cause.

By this date the Ruhr had been completely encircled and the German Army in it trapped. This victory gained, Eisenhower, despite the opposition of the British Chiefs of Staff and the Prime Minister, determined to direct his main attack against the Leipzig area. For that reason he removed the United States Ninth Army from the sphere of Montgomery and instructed him to cross the Weser, Aller, and Leine, capture Bremen, pass the Elbe and then move up to the Baltic coast. The departure of the United States Ninth Army entailed that of XXIX Tactical Air Command, who had fought so blithely beside the Second Tactical Air Force. Regrets at parting were mutual. Both British and American pilots had learned to know and understand each other, and the harmony which had existed between them and the staffs directing their efforts had been complete.

As soon as he was firmly on the other side of the Rhine, among other orders given by Montgomery was one of great importance to the Second Tactical Air Force. The capture of airfields should be one of the major objects of the Army. Such operations were very necessary, for Coningham had warned Twenty-First Army Group that if, as was hoped, the advance would be rapid, it might not be possible for his Command to give full support unless it could be provided with the requisite number of forward airfields. Up to 12th April, No. 83 Group under Broadhurst, supporting the Second Army, had been based on Eindhoven and other airfields in southwest Holland. On 10th April, Broadhurst, always in close touch with Dempsey, set up his headquarters at Mettingen, near Osnabrück, and two days later his Group was operating from four bases east of the Rhine and two west of it. Until the arrival, some nine days later, of No. 84 Group, under Air Vice-Marshal Hudleston, it was to be his task to cover the troops unaided. The Spitfire squadrons of No. 125 Wing were the first to cross the river and station themselves at Twente, an airfield captured twenty-four hours earlier by the British Second Army. Two days before, No. 83 Group had been assisted by No. 84 Group, and the combined Second Tactical Air Force made 628 sorties over the new bridgehead which had been formed beyond the Weser. Throughout these days, when final victory was very near, great efforts were made by the indefatigable Mosquitos of No. 2 Group to attack the enemy during the hours of darkness when he had still a chance to move unseen.

The smoothness of the Second Army’s advance had been much helped by the tactical reconnaissance flights of No. 39 Wing, while No. 35 Wing had kept the Canadian Army, left behind to deal with the enemy in Holland, closely informed of all his movements in that area. No. 34 Wing on strategical reconnaissance over Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein was soon reporting that much of what was left of the Luftwaffe was concentrated on airfields in the Danish peninsula.

By 24th April, VIII Corps, the advance guard of the Second Army, had reached the west bank of the Elbe and cleared it, and the day before, XII Corps had arrived opposite Hamburg, while XXX Corps was on the outskirts of Bremen. The Second Army was now, therefore, within easy range of the Luftwaffe bases east of the Elbe. The German Air Force, however, was in no position to take any steps against them. Its airfields were congested, it was short of fuel and was suffering heavy casualties daily. Already on 13th April pilots of No. 83 Group reported that the Germans were burning aircraft on the airfield at Lüneburg.

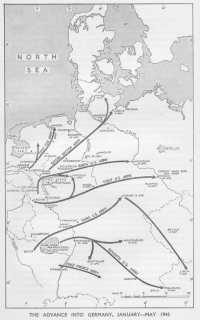

The Advance into Germany, January–May 1945

The end was in sight. Nevertheless during the last fortnight of April, No. 83 Group was still called upon frequently to help the army, usually by means of attacks on fortified villages with bombs and rockets. On 20th April, its fighter pilots had a stroke of luck and shot down eighteen Messerschmitt 109’s and Focke-Wulf 190’s in the act of taking off from an airfield near Hagenau. Altogether that day the Group destroyed thirty-nine of the enemy for the loss of seven of their own aircraft, thus bringing the number of German aircraft of which they claimed the destruction, to more than 1,000 since 6th June, 1944.

At night No. 2 Group continued to harass communications and attack convoys. The performance of the squadrons flying the Mosquito VI’s was particularly praiseworthy. As soon as the sun went down, they were on the wing ranging from Gröningen in north-east Holland to as far into Germany as Stendal and Magdeburg. In daylight the Mitchells, together with the United States Ninth Air Force, attacked towns and villages on the line of the Army’s advance, where the presence of troops and transport was suspected. The life of the pilots of No. 85 Group during this period was uneventful, for very few German aircraft crossed the lines in the hours of darkness.

In the meantime, No. 84 Group was giving support to the Canadian Army in their task of clearing Holland of the enemy. With it operated the only jet fighter squadron in the whole Command, No. 616, flying Meteors Mark III. During April, since enemy aircraft were lacking, this squadron attacked vehicles. The immediate task of the Group was to provide air cover for II Canadian Corps advancing towards Zutphen with the object of freeing north-east Holland. Besides supplying the prescribed air cover, for so long a matter of routine, certain operations for the transport to their destination of Special Air Service troops were planned; but few were mounted, for the speed of the advance on the ground made the intervention of this secret force, among the most gallant of the whole army, unnecessary. On the night of 7th/8th April, one such operation did take place, two battalions of French Special Air Service troops, commanded by Brigadier J. M. Calvert, being dropped in conditions of low cloud and fog in the area to the south of Gröningen, then under attack by the 2nd Canadian Division. Considering the very bad weather, the forty-seven Stirlings of No. 38 Group which carried out this operation were remarkably successful, though some of the troops were landed three and a half miles away from the dropping zone. On the 8th and 12th April, they were supplied several times with weapons and equipment by Typhoons of No. 84 Group.

In the air assistance afforded to the Canadian Army, the ubiquitous No. 2 Group also took a hand, attacking gun positions and strong points, especially when the Lower Rhine was crossed at Arnhem. By the 15th, this town, which had witnessed possibly the most gallant fighting of the whole war, was cleared of the enemy. The Zuider Zee was reached on 18th April and there, having arrived at what was called the Grebbe line, the Canadians halted. To have advanced further west might well have provoked the Germans into cutting the dykes and inundating yet more of Holland.

No. 84 Group was also able to help a large garrison of Russian so-called volunteers, stationed on the Island of Texel, who had revolted against their German masters and called for air support. This was furnished by two squadrons of Typhoons which bombed German gun emplacements with 1,000-lb. bombs.

While remaining static in Holland the Canadian Army moved in Northern Germany against Oldenburg to the capture of Emden. Here the support of the fighter-bombers of No. 84 Group was so effective as to call forth the praise of the commander of the troops in the field, who was especially impressed by the assault delivered on 12th April by Typhoons against the village of Friesoythe, which they set on fire with rockets. In the days following, foggy and misty though they were, the pilots turned their attention to enemy airfields in the neighbourhood of Oldenburg and destroyed a number of aircraft on the ground. They also attacked such enemy shipping as might still be found between the Hook of Holland and the mouth of the Elbe.

By the last week in April the Allies and the forces of the U.S.S.R. were so close that it became necessary to make sure that the Russians approved the targets given to the Tactical Air Forces before the attacks were made. Disputes on this matter and on the location of the bombline, now a matter of considerable difficulty for the situation was extremely fluid, were eventually settled on 23rd April. By then the Second Tactical Air Force was being supplied with petrol, oil, and ammunition largely from the air by Nos. 38 and 46 Groups, 280 aircraft being available every day for these operations, which were most successful. During April, No. 46 Group carried nearly 7,000 tons of supplies while No. 38 Group carried 514. Nor did their Dakotas, Stirlings and Halifaxes return empty, for, during that period they brought back to England 27,277 British and American prisoners of war and 5,986 casualties.

The last great obstacle facing Montgomery’s forces was the Elbe, next to the Rhine the widest river in Germany. At first the intention was that it should be crossed in the same manner as the Rhine and that a battalion of the airborne division should be dropped on the

other side. The fall of Bremen, however, led to a weakening of the German resistance and the operation was cancelled. Preceded by commandos, VIII Corps crossed the Elbe on 29th April against very little opposition. That day the chief task of No. 83 Group was to silence a number of railway guns, which were interfering with the bridging operations. Though no direct hits were scored, the German gunners appear to have been harassed, for their firing was wild and inaccurate. Once the bridgehead on the other side of the Elbe was secured, opportunities to raid it by the Luftwaffe were many. They had but a very short distance to fly and therefore would consume very little petrol. The weather, moreover, was atrocious, thick cloud, often as low as 600 feet, obscuring the battlefield and making the task of the fighter pilots far from easy. No. 83 Group was soon engaged with Focke-Wulf 190’s and Messerschmitt 109’s. On 30th April a battle brisker than had been fought for many a long day took place, the fighters of No. 83 Group claiming thirty-seven of the enemy destroyed. The previous day the Meteors of No. 616 Squadron had appeared on the scene but could find no fighters to oppose them. Two of them collided in cloud and their pilots were killed. These were their only casualties.

Having passed the Elbe, the British Second Army moved on 2nd May towards Lübeck, and, on that day, the 6th Airborne Division made contact with the Russians at Wismar on the Baltic. It was Montgomery’s intention to turn north-west to liberate Denmark, but there was no need. On 3rd May Dönitz, who had succeeded Hitler after his suicide on 30th April, sent emissaries to Montgomery’s headquarters set up on Lüneburg Heath. By that date, and indeed for some time before, panic had seized the leaders of Germany, both high and low. Seeking for means of escape they looked longingly across the Baltic to Norway. Thither they determined to flee and for that purpose large convoys, amounting in all to about 500 ships, began to assemble in the wide bays of Lübeck and Kiel. For a moment it seemed possible that they contemplated not flight only but also the continuation of the struggle. On putting to sea these convoys were at once attacked by aircraft of the Second Tactical Air Force. Every effort was made to bring this last despairing move to naught, it being believed that a number of high Nazi officials were in all probability on board several of the ships. In their attack of 3rd May No. 83 Group claimed to have sunk thirteen vessels and damaged one hundred and one, No. 84 Group claimed four and six respectively. Losses to Second Tactical Air Force amounted to thirteen aircraft shot down by flak or damaged by explosions from enemy shipping.

For the last six weeks of the war the main headquarters of the Second Tactical Air Force had been in a deserted lunatic asylum at Suchteln on the borders of the Rhine. A reconnaissance party of the Royal Air Force Regiment, sent early in April to Bad Eilsen in search of a place at which to locate the advanced headquarters, stumbled on Professor Tank, the head designer of the Focke-Wulf Aircraft Company. He and his assistants were made prisoners and subsequently supplied information which showed that, as far as design went, the Luftwaffe was probably ahead of the Allied Air Forces.

In every other respect as a fighting service, this once proud force was finished. It had been brought so low not only as the result of mishandling by the German High Command, but primarily because it had been outfought in battle. The Royal Air Force and the American Army Air Force had missed few opportunities to attack it and to maintain that attack regardless of circumstances, and the aggressive attitude of their pilots far from wavering had increased to a point when they would brook no opposition in the fulfilment of their tremendous and variegated task. They rode in triumph a whirlwind of their own creation, all-devouring, insatiable, irresistible. The long years of trial when fortune swayed this way and that, when the fate of a campaign might depend on the capture or retention of a few airfields, or the arrival of a tanker or two of aviation spirit, were but memories now. At long last the will had become the deed. Nevertheless, the poor showing made by the Luftwaffe in the defence of Germany in the later stages of the war came as a surprise at the time. Some two months before the end, its numbers had been reduced to 2,278 aircraft of all kinds, of which 1,704 were serviceable, the great majority being fighters, 739 day and 748 night. This small number of operational aircraft may be contrasted with the huge number awaiting delivery at the German factories. Despite the long series of attacks by Bomber Command and by the heavy bombers of the American Army Air Force, the fighter production of the German factories appears to have risen steadily, until by January, 1945, if the figures supplied by Speer after the war are accurate, which is by no means certain, it had reached the very high figure of 2,552 a month. Long before then, however, the shortages of petrol and transport caused by the unceasing attacks of the Allies had rendered all this labour of no avail. These were the immediate causes of its impotence; the root cause went deeper and is to be found in the attitude of its High Command.

Though the British and Americans made many mistakes, yet long before the war ended they had come to understand and to apply the correct principles which must govern air power. They had never

stood still, but had constantly expanded and sought to improve their air forces. The Germans, on the other hand, made over-confident by early and easy success, made no attempt till it was far too late to improve the Luftwaffe. Aircraft which had been good enough to win victory in 1940 and 1941 were still expected to do so in 1942 and 1943. That was their belief and that was their great error. The weapons of the German Army constantly improved; those of the Luftwaffe on the whole did not, despite the advent of its jet fighters. These might have proved a formidable menace had their development been pressed and had pilots of the requisite calibre been available. Moreover, being under the domination of the Army, the Luftwaffe moved uneasily to and fro between the Russian front and the Western. Not all the bravery of its pilots—and they remained of good courage till the end—could offset this mishandling. It was like a precocious child whose parents suddenly neglect it and then, when an emergency arises, expect it to assume the responsibilities of an adult, though it has never received the bodily or mental sustenance to enable it to do so. These were denied it not only by the supineness of the German High Command, but chiefly by the aggressive attitude of its enemies. As the war progressed, the mounting bomber offensive forced the transfer of more and more of the best German pilots to night fighter formations, the day fighters were gradually mastered by those of the American air forces whose long range penetrations of Germany became of increasing importance and the general onslaught played havoc with training programmes. Before the end came there were neither instructors nor petrol available. This behaviour of the Germans towards their own air force, which in the earlier days of the war had served them so well, is an epitome of the innate defects of judgement which led to their country’s ruin. Meanwhile the Japanese fought on.