Section 2: Origins of the Combined Bomber Offensive

Chapter 7: The Daylight Bombing Experiment

WHEN twelve B-17’s of the Eighth Air Force attacked Rouen on 17 August 1942, they inaugurated an experimental campaign of daylight bombing which was to culminate ten months later in the Combined Bomber Offensive. AAF leaders most intimately concerned, made soberly aware of the difficulty and the significance of their task by intensive study of British and German experience, were prepared to devote their earliest combat missions to testing American techniques and equipment in the war’s toughest air theater. What they could not then foresee was the inordinate length of the experimental phase of their program. Competing strategic policies and the chronic scarcity of equipment and trained men, which long dogged the Allied war effort, combined to postpone until summer of 1943 the launching of a full-scale bomber offensive. With the limited forces available in the interim, the fundamental theses of strategic bombardment could hardly be given an adequate test. Hence, though the early operations of the Eighth Air Force were successful enough eventually to insure augmentation of forces, the most immediate significance of those missions lay in the tactical lessons derived therefrom.

The delay was the more vexing because from an early stage in war planning the bomber campaign against Germany had been conceived as the first offensive to be conducted by United States forces. In conversations held early in 1941 (ABC-1), Anglo-American staff representatives had agreed on certain basic assumptions which should guide combined strategy if the two nations found themselves at war with the European Axis and Japan: that the main Allied endeavor should be

directed first against Germany as the principal enemy; that defeat of Germany would probably entail an invasion of northwestern Europe; and that such an invasion could succeed only after the enemy had been worn down by various forms of attrition, including “a sustained air offensive against German Military Power, supplemented by air offensives against other regions under enemy control which contribute to that power.”*

Those basic assumptions had guided proposed deployments in the operations plan (RAINBOW No. 5) current among the U.S. armed forces on the eve of Pearl Harbor. They had guided also the AAF’s first air war plan, by virtue of which heavy claims had been levied against the nation’s manpower and material resources. That plan (AWPD/1, 11 September 1941) had indeed subordinated air activities in all theaters to a protracted program of strategic bombardment of Germany on a scale hitherto unheard of. The early successes of the Japanese had seriously challenged the practicability of adhering to those plans, but in spite of the necessity of dispatching reinforcements to the Pacific the Combined Chiefs of Staff had stood firmly upon previous agreements. Proposals accepted in January 1942 for early deployment of heavy bombers in the United Kingdom were of necessity couched in modest terms, but in mid-April the Combined Chiefs and their respective governments had agreed to mount a cross-Channel invasion – preferably in spring 1943 (ROUNDUP), but if urgently required in September 1942 (SLEDGEHAMMER). Plans for the build-up of forces (BOLERO) were given high priority. With either D-day, the time allowed for softening up the enemy by bombing the sources of his military power would be more limited than had been contemplated in AWPD/1; counter-air activities and air support of ground operations became in prospect relatively more important. Hence, though BOLERO promised to quicken the flow of AAF units to the United Kingdom, it changed somewhat the nature of the force to be deployed and, in anticipation, the character of its mission.

AAF plans to organize, equip, and base an air force in the United Kingdom were brought rapidly to maturity.† The Eighth Air Force, activated in January 1942 and committed to BOLERO early in April, began its move across the Atlantic in May. Under the leadership of

* Early developments of policy affecting the role of the AAF in a European war have been discussed in Volume I of this history, passim.

† See especially Volume I, pp. 557–654

Maj. Gen. Carl Spaatz, the force had been organized into bomber, fighter, composite (for training), and service commands. Under Brig. Gen. Ira C. Eaker the VIII Bomber Command (with which this chapter is most intimately concerned) had been organized into three wings, based in East Anglia: the first, under Col. Newton Longfellow, with headquarters at Brampton Grange; the second, under Col. James P. Hodges, at Old Catton; the third, under Col. Charles T. Phillips, at Elveden Hall.1 Of the heavy bombardment groups allocated to the Eighth Air Force, only one, the 97th, had become operational by 17 August, but others were in training, at staging areas, and en route from the United States. Early in July, AAF Headquarters had estimated the BOLERO build-up of air units by 31 December 1943 at 137 groups, including 74 bombardment groups (41 heavy, 15 medium, 13 dive, and 5 light), 31 fighter groups, 12 observation groups, 15 transport groups, 4 photo groups, and 1 mapping group. Arrangements had been effected with the British to provide 127 airdromes and such other installations as would be required for an air force expected ultimately to constitute fully half the projected combat group strength of the AAF.2

By the beginning of August 1942, BOLERO plans had been thrown into a state of grave uncertainty by the decision to undertake an early invasion of North Africa. This meant an indefinite postponement of the cross-Channel push and the diversion to TORCH, as the new venture was called, of much of the air power previously allocated to BOLERO. The bomber offensive against Germany was not eliminated from Allied strategy – operations of the RAF Bomber Command went uninterruptedly along – and the new timetable, by postponing the continental invasion until probably 1944, coincided more accurately than the BOLERO plans with previous AAF thought. But with TORCH the Eighth Air Force had suffered, in anticipation, a heavy loss. This was the second blow within a week. Late in July it had been decided that AAF commitments to BOLERO would be readjusted in favor of the Pacific war. There were those, especially in the U.S. Navy, who argued with some cogency and much energy that the chief weight of American arms should be thrown first against Japan, and under the circumstances the immediate reallocation of fifteen groups from BOLERO to the Pacific had to be viewed as a temporary compromise rather than as a final settlement of the dispute. In the face of these diversions, fulfillment of the ambitious plans of the AAF for its bomber offensive would mean a top priority, possibly even an overriding priority,

for the production of airplanes, especially of heavy bombers. Already in 1942 the eventual limits of American productive capacity could be fairly gauged, and such a priority would conflict seriously with programs considered essential by the Army Ground Forces and the Navy, both of which had behind them the force of military tradition. Thus the fate of the American bomber offensive involved most difficult problems of strategy and logistics. For the Eighth Air Force there was a tactical problem as well, and on its solution hinged much of the answer to the broader issues.

The problems could be more simply stated than answered. Could Anglo-American bomber forces strike German production forces often enough and effectively enough to make the eventual invasion appreciably less costly? Could the forces required be provided without unduly hampering air activities elsewhere and the operation of the other arms in any theater? Could the bomber campaign be conducted effectively within acceptable ratios of losses? For those questions the RAF had answers which, if not conclusive, were founded upon experience. Their bombing of industrial cities had in recent attacks wrought great destruction; they had secured a favorable position for the heavy bomber in the allocation of production potential; and in their night area bombing they had learned to operate without prohibitive losses.

The Eighth Air Force, as yet without experience, had no answers. The basic concept of a combined bomber offensive presumed complementary operations of RAF night bombers and AAF day bombers. American doctrine called for the destruction of carefully chosen objectives by daylight precision bombing from high altitudes. Whether those techniques could be followed effectively and economically in the face of German flak and fighter defenses and under weather conditions prevailing in northwestern Europe remained to be proved. Many in the RAF were politely skeptical; Eighth Air Force leaders were guardedly optimistic. But the problem was crucial: upon its successful solution hung the fate of the Eighth’s participation in the combined offensive and of the Eighth’s claim to a heavy share of the forces later available. So it was that the tiny force of B-17’s which struck at the Rouen-Sotteville marshalling yard on 17 August was watched with an intensity out of all proportion to the intrinsic importance of the mission.* it was too that, in the months which followed, Eighth Air Force officers continued to experiment, weighing as carefully as they might

* See Volume I, pp. 655–68

the evidence provided by combat missions and trying desperately to overcome difficulties which stemmed in no inconsiderable part from the attenuated size of their force.

Controls and Target Selection

Whatever uncertainties may have faced the Eighth Air Force in August 1942, its leaders were anxious to get available bomber units into action at the earliest opportunity. The general mission had for the moment been clarified. As late as 21 July, Eisenhower, as theater commander, had defined the task of the Eighth in terms of the contemplated invasion of the continent – to achieve air supremacy in western France and to prepare to support ground operations. TORCH had outmoded that directive. By the first of August, Eaker could describe the job of his VIII Bomber Command as the destruction of carefully chosen strategic targets, with an initial “subsidiary purpose” of determining its “capacity to destroy pinpoint targets by daylight accuracy bombing and our ability to beat off fighter opposition and to evade antiaircraft opposition.” To accomplish these general objectives it was necessary to establish a definite system of operational control which would mesh AAF and RAF efforts and to determine specific target systems appropriate to the U.S. forces at hand.

Although the Eighth Air Force was established within the normal chain of command in the ETO, its bombing policy was supposed to originate with the Combined Chiefs of Staff, who were to issue the necessary strategic directives through the Chief of Staff, U.S. Army.3 For all practical purposes, however, such policy was left during this period to American commanders in the United Kingdom, who worked in closest cooperation with the appropriate RAF authorities. Much of the success of that cooperation derived from friendly personal relations between the two forces; the most formal definition of their mutual responsibilities consisted of the Joint American/British Directive on Day Bomber Operations Involving Fighter Cooperation, dated 8 September 1942.* Worked out by the RAF and General Spaatz, this document, as its title suggests, had been evoked by the Eighth’s current dependence upon British fighter escort.

Declaring that the aim of daylight bombing was “to achieve continuity in the bombing offensive against the Axis,” the directive laid responsibility for night bombing on the RAF, for day bombing on the

* For full text, see Volume 1, pp. 608–9

Eighth, which should accomplish its mission “by the destruction and damage of precise targets vital to the Axis war effort.” The daylight offensive was to develop in three phases marked successively by the increasing ability of the American force to provide its own fighter escort and to develop tactics of deep penetration. In the first phase, where the RAF would furnish most of the fighter support, targets would be limited to those within tactical radius of the short-range British fighters. As more U.S. fighters became available, they would provide direct support while the RAF flew diversionary sweeps and gave withdrawal support. Eventually the AAF would take over most of the task, requesting aid when necessary. Practical measures for control were described. During the first phase – with which this chapter is concerned – the commanding general of VIII Bomber Command was to initiate offensive operations, making preliminary arrangements for fighter support with the commander of VIII Fighter Command, who in turn would consult his British opposite number for detailed plans and assignment of forces.

Target selection, as periodically reviewed “within the existing strategy,” was to be the responsibility of the commanding general of the Eighth Air Force and the assistant chief of Air Staff for operations (British). To coordinate planning effectively, provision was made at Spaatz’ suggestion for regular meetings between the American command and the British Air Staff. Meeting first at the Air Ministry on 21 August, this group subsequently bore the cumbersome title of Committee on Coordination of Current Air Operations. In all, sixteen meetings were held between 21 August and 5 February 1943 – at weekly intervals before December, thereafter only as required. Thus the establishment of target priorities and the selection of particular targets, though primarily tasks for the Eighth Air Force, were subject to constant review in terms of over-all Allied strategy and of RAF operations. Among other advantages, this insured the AAF access to RAF target intelligence, still indispensable to the Americans. In addition to this liaison machinery at the air staff level, provision was made also for closest coordination between staff officers of VIII Bomber Command and RAF Bomber Command, and Eaker made it a point to attend the operational conferences of the latter organization at Southdown.4

Meanwhile, actual target systems for the earliest phase of the offensive were being selected. VIII Bomber Command had received its first bombing directive early in August. The Eighth Air Force had declared

as its general aim destruction of the enemy’s will and ability to wage war. Since his will to fight at present depended, it was thought, upon the success of his land armies and of his submarine campaign, the daylight bombing effort should be directed against (1) the factories, sheds, docks, and ports in which he built, nurtured, and based his s, (2) his aircraft factories and other key munitions establishments, and (3) his lines of communication. By 14 August this program had received

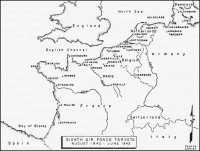

Map 10: Eighth Air Force Targets: August 1942–June 1943

additional refinement and some alteration. Daylight bombing objectives were then divided into two categories: a general objective which might be attacked anywhere in Europe with cumulative results; and a series of precise targets which could be attacked only when conditions were favorable but which, if destroyed, would seriously affect the German war effort. The rail transportation system constituted the general objective. Precision objectives, in order of priority, were fighter-plane assembly plants, Ruhr power plants, and submarine installations.5 Then on 25 August, in accordance with a decision reached in the commanders’ meeting on the previous day, Spaatz issued to VIII Bomber Command a list of specific targets, all in occupied France or the Low Countries. First priority was given to aircraft factories

and repair depots, next came marshalling yards, then submarine installations. Some miscellaneous targets previously authorized for attack, such as the Ford and General Motors plants at Antwerp, remained eligible.6

This list, except for the subsequent removal of the Antwerp plants, appears to have governed operations of the Eighth until 20 October 1942. It differed radically from that which had been suggested a year earlier in AWPD/1 Some changes from that previous plan were to be expected as the tactical situation fluctuated, but to no small degree the actual choice of targets in August was determined by the current weakness of the force. The tactical radius of RAF fighters limited the choice to objectives on or near the European coast. Missions of shallow penetration offered an excellent opportunity for the fledgling air force to find its wings, but the fact that those objectives lay wholly in friendly occupied countries was to raise political problems of some delicacy.

The First Fourteen Missions

The first mission had been flown by Fortresses and crews of the 97th Group from its East Anglian base at Polebrook.* The nervous tension common to a maiden effort had been heightened by repeated postponement of the mission, and when the little force of B-17’s finally bombed their first target without loss and with greater accuracy than had been expected from green crews the event did much to raise the morale of American airmen of all echelons.

The second mission, flown two days later, did nothing to diminish that warm feeling of accomplishment. On the 19th, B-17’s of the 97th Group (this time twenty-four of them) made an attack on the Abbeville/Drucat airdrome. The mission had been planned as part of the air operations undertaken in connection with the Dieppe raid. According to Air Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, it appeared “that the raid on Abbeville undoubtedly struck a heavy blow at the German fighter organization at a very critical moment during the operations” and thus “had a very material effect on the course of the operations.”7 RAF fighter pilots flying over the airdrome on the day following the attack reported the main dispersal area to have been apparently “completely demolished.” Subsequent reconnaissance indicated somewhat less cataclysmic devastation.8

It was not until Mission 9, on 5 September 1942, that VIII Bomber

* For a full discussion, see Volume 1, pp. 661–68

Command again equaled the force sent out on 19 August. Meanwhile, light missions were flown to targets consisting of the Longueau marshalling yards at Amiens, a vital focal point in the flow of traffic between France and northern Germany; the Wilton shipyard in the outskirts of Rotterdam, the most modern shipyard in Holland and one employed to capacity by the Germans for servicing surface vessels and submarines; the shipyard of the Ateliers et Chantiers Maritime de la Seine, at Le Trait; the well-equipped airplane factory of Avions Potez at Meaulte, an installation used extensively by the enemy as a repair depot for the near-by fighter base; and the Courtrai/Wevelghem airdrome, a base for Luftwaffe FW-190 fighters. All lay within easy fighter range and required at most only shallow penetration of enemy occupied territory.9

These six missions followed the pattern laid down by the preceding two. The B-17’s flew under heavy fighter escort, provided largely by the RAF, and bombed at altitudes from 22,000 to 26,000 feet in circumstances of generally excellent visibility. They encountered for the most part only slight enemy opposition. No B-17’s were lost. On 21 August, however, during an unsuccessful attempt to bomb the Wilton shipyard the bombers had a brisk battle with enemy aircraft.10 They were sixteen minutes late for their rendezvous with the RAF fighter escort, and as a result the escort was able to accompany them only halfway across the Channel. The bomber formation received a recall message, but by that time it was over the Dutch coast. While unescorted it was attacked by twenty to twenty-five Me-109’s and FW-190’s. A running fight ensued which lasted for twenty minutes, during which time both the pilot and co-pilot of one B-17 were wounded, the co-pilot so seriously that he died soon after. The gunners claimed two enemy fighters destroyed, five probably destroyed, and six damaged. It was the first time the Fortresses had been exposed to concerted fighter attack without the protection of friendly aircraft, and the results must have impressed the enemy pilots with the ability of the Fortress to defend itself.11

Bombing accuracy continued to be good for inexperienced crews. In each case enough high-explosive and incendiary bombs fell in or near the target areas to prompt General Eaker to predict that in the future 40 per cent might be expected to fall within a radius of 500 yards from the aiming point.12 These half-dozen missions demonstrated, however, that bombing which could be considered fairly accurate might

not produce a corresponding measure of damage to the target. On the mission to Le Trait, for example, although twelve bombs out of a total of forty-eight dropped were plotted within 500 yards of the aiming point, no material damage was apparently done to the shipyard installations themselves. Again in the attack on the Potez aircraft factory, ten craters were made which paralleled the target, close enough to it to be considered fairly accurate but far enough to land harmlessly in open fields.13

In Mission 9 the American bombers again struck at the Rouen-Sotteville marshalling yard. The force was the largest yet dispatched. Thirty-seven B-17’s took off, twenty-five from the 97th Group and twelve from the 301st, the latter on their first combat mission. Thirty-one planes bombed the target (the locomotive depot), the other B-17’s being unable to drop their bombs on account of mechanical failures. The bombers met little enemy opposition, although the RAF fighters supporting were challenged by a few FW-190’s.14

A large percentage of the bombs, almost one-fifth of the high-explosive bombs dropped, burst within the marshalling yard installations.15 Photo reconnaissance made almost a month later, on 2 October, indicated that, while practically the entire damage to the running lines throughout the yards had been repaired, the transshipment sheds and the locomotive depot were in very restricted operation. On 8 August, forty locomotives had been observed on the tracks around the latter; now only eighteen could be detected.16

To the local French population the success of the mission appeared less conclusive than it had to observers in the United Kingdom. A large number of bombs had in fact fallen outside the marshalling yards, many of them in the city itself, and several far enough from the target to seem to a ground observer to have borne little relation to any precise aiming point. As many as 140 civilians, mostly French, had been killed, and some 200 wounded17 One bomb, fortunately a dud, was reported to have hit the city hospital, penetrating from roof to cellar.18

Beginning with the tenth mission on 6 September, VIII Bomber Command encountered greatly increased fighter opposition. Indeed it was during that day’s operations over occupied France that the command suffered its first loss of aircraft in combat. Hitherto it had appeared that the B-17’s bore charmed lives; but then the enemy attacks had been light in weight and tentative in character. From now

on, the Fortresses had a chance to show what they could do in the face of relatively heavy and persistent fighter resistance.

On 6 September, heavy bombers of the 97th Group, augmented to a strength of forty-one by elements from the newly operational 92nd Group, were sent out again to strike the Avions Potez aircraft factory at Meaulte. In order to keep enemy fighters on the ground and provide a diversion for the main force, thirteen B-17’s of the 301st Group attacked the German fighter airdrome at St. Omer /Longuenesse. Similarly, twelve DB-7’s of the 15th Bombardment Squadron (L) attacked the Abbeville/Drucat airdrome.19 In spite of these diversionary efforts, all crews on the primary mission reported continuous encounters from the French coast to the target and from the target back to the French coast. As a result of perhaps forty-five to fifty encounters, mostly with FW-190’s, the B-17 crews claimed several enemy aircraft destroyed or damaged. Two of the heavy bombers failed to return. Many encounters also took place between FW-190’s and the supporting RAF fighters.20 The bombing at Meaulte seems to have suffered little in accuracy from the distracting fighter attacks, for it was, if anything, more accurate than on the previous attack against the same target and probably more effective.21

A similarly bitter aerial battle resulted when, on 7 September, a force of twenty-nine B-17’s made an attack on the Wilton shipyard near Rotterdam, the ineffectiveness of which resulted from adverse weather rather than from enemy action. Again the claims registered by the bomber crews were surprisingly high: twelve destroyed, ten probably destroyed, and twelve damaged.22 Even discounting the optimistic statistics of the gunners, it seemed evident that the Fortresses could take care of themselves in a surprisingly competent fashion.

Gunners did not again have the opportunity to test their ability until 1 October. Meanwhile, persistently bad weather, together with a directive ordering all combat activity of the Eighth Air Force to take second place to the processing of units destined for North Africa, had discouraged further operations.23 On 1 October, thirty-two B-17’s bombed the Avions Potez factory at Meaulte for the third time, while six of the heavies attacked the German fighter airdrome at St. Omer /Longuenesse for the second time. All bombers returned but they met constant and stubborn fighter opposition. So many encounters took place that crews had to be interrogated a second time and even then the claims registered were considered too high.24 This aerial battle was all

the more remarkable because the heavy bombers had flown under the cover, direct or indirect, of some 400 fighter aircraft, in spite of which the Germans had been able to drive home their attacks on the bombers. Whatever damage was inflicted on the aircraft repair and airdrome facilities – and several direct hits were scored – was swallowed up in the enthusiasm engendered by the remarkable defensive power displayed by the Fortresses.25

The day bombing campaign reached a minor climax in the mission against Lille on 9 October. It was the first mission to be conducted on a really adequate scale and it marked, as it were, the formal entry of the American bombers into the big league of strategic bombardment. Then, for the first time, the German high command saw fit to mention publicly the activities of the Flying Fortresses, although they had already made thirteen appearances over enemy territory. Lille’s heavy industries contributed vitally to German armament and transport. The most important of these industries, the steel and engineering works of the Compagnie de Fives-Lille and the locomotive and freight car works of the Ateliers d’Hellemmes, constituted one composite target.26

The mission had been planned on an unprecedented scale. One hundred and eight heavy bombers, including twenty-four B-24’s from the newly operational 93rd Group, were detailed to attack the primary target at Lille, and seven additional B-17’s flew a diversionary sweep to Cayeux. Of the aircraft dispatched, sixty-nine attacked the primary target;27 two bombed the alternative target, the Courtrai/Wevelghem airdrome in Belgium; six attacked the last resort target, the St. Omer airdrome; two bombed Roubaix; and thirty-three (including fourteen of the B-24’s) made abortive sorties. Approximately 147 tons of 500 pound high-explosive bombs and over 8 tons of incendiaries fell on Lille.28

The bombing this time did not demonstrate the degree of accuracy noticeable in some of the earlier and lesser efforts. Of 588 HE bombs dropped over Lille, only 9 were plotted within 1,500 feet from the aiming points. Many fell beyond the two-mile circle, some straying several miles from the target area.29 The errors may be explained in part by the fierce fighter attacks sustained by the bombers over the target, but they no doubt also owed much to the inexperience of at least two of the groups participating.30 A large proportion of the bombs fell on the residences surrounding the factory at Fives-Lille. Civilian casual ties were placed by a ground observer at forty dead and ninety

wounded.31 Ground intelligence sources also reported that a large percentage of the bombs failed to explode.32

Yet, despite a scattered bomb pattern and numerous duds, several bombs fell in the target area – enough, in any event, to cause severe damage to both targets, together with considerable incidental damage to industrial and rail installations.33 Ground observations made by Fighting French informants credited the U.S. forces with completely stopping work at the Hellemmes textile factory and with doing severe damage to the power station, the boiler works, and the turbines at the Fives-Lille establishment. A branch line to another power station apparently relieved the enemy’s situation, however, for work in the factory was resumed after a relatively brief time.34

Again, as in the Potez mission of 2 October, the question of bomb damage came to be overshadowed by that of the day bomber’s ability to defend itself against fighter attack. As in that mission, the attacking Me-109’s and FW-190’s concentrated on the bombers to the practical exclusion of the combined British and U.S. fighter escort, which in this instance numbered 156 aircraft, including 36 P-38’s from the VIII Fighter Command.35 Unusually heavy fighter opposition brought reports of numerous combats. Three B-17’s and one B-24 failed to return, although the crew of one Fortress was picked up at sea. In all, thirty-one crew members were reported missing and thirteen wounded, four B-17’s suffered serious damage, and thirty-two B-17’s and ten B-24’s were slightly damaged by fighter action.36 Those losses were subject to immediate and positive confirmation; the damage inflicted upon the GAF was less readily assessed.

Initially, it was reported that the bombers had destroyed fifty-six fighters, probably destroyed twenty-six, and damaged twenty. According to these figures, the Fortresses had put out of action 102 enemy planes – more than 15 per cent of the estimated GAF fighter strength in western Europe. British intelligence believed that no more than sixty enemy aircraft could possibly have intercepted. This discrepancy called for a re-estimate of losses inflicted in the Lille mission and confirmed the belief, engendered by the uniformly high claims on earlier missions, that VIII Bomber Command was in need of a system of interrogation and evaluation that would prevent such inflation in the future. By 24 October. the Lille claims had been scaled down to twenty-five destroyed but with a listing of thirty-eight probables and forty-four damaged for a grand total in excess of the original figure. In January

1943 a general review of early combat reports reduced the figures for this engagement to twenty-one destroyed, twenty-one probably destroyed, and fifteen damaged.37 These more conservative figures argued little against the earlier conclusion at AAF Headquarters that the Lille mission offered convincing evidence that the day bombers “in strong formation can be employed effectively and successfully without fighter support.38 But it is now apparent from enemy sources that this optimistic view was justified by the ability of the bombers to get through to the target and to return with limited losses rather than by any serious losses inflicted upon enemy fighter forces. Actually, the Germans listed one fighter destroyed in the Lille action and none damaged. One other fighter lost that day could possibly be credited indirectly to the effects of combat with the American planes. In short the maximum possible score was 2, not 102 or 57.*

Although it is difficult to explain so gross an exaggeration, the chief source of error was easily diagnosed. It was hard for crews in a large formation to determine which bomber had been responsible for an apparently destroyed or damaged German plane, so that each gunner who had fired at the enemy fighter from a reasonable range was likely to claim it: one fighter actually shot down might be multiplied into a dozen in the final report. The crew member, however honest in intent, could hardly qualify as a Detached witness. From his battle station, vision was straitly limited and his impressions of a complex and incredibly swift action must inevitably be faulty and incomplete; the promised award of a decoration for his first kill of a German plane did little to dissuade him from the not unnatural belief that it had been his bullet which had scored. These difficulties appear obvious in retrospect – and one may hope that they would so have appeared at the time to one familiar with the ordinary canons of historical analysis – but they presented a problem for which the interrogating officers had not been fully prepared. They had learned at the intelligence school at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, how to evaluate most of the important information elicited from a returning crew, particularly that concerning bombing results. But as late as 24 August 1942 the training manual on bomber crew interrogation did not even suggest, as part of the check list of questions, the query, “Were there other bombers firing at the enemy

* Information supplied through the courtesy of the British Air Ministry and based on German Air Ministry returns compiled by the General Quartermaster’s Department for the purpose of ascertaining replacement requirements and for personnel records.

fighter claimed as destroyed?” Harrisburg had been strongly influenced by RAF intelligence procedure, and it may be that the lack of English experience in day bomber battles over Europe helps account for this important omission. At any rate, the previously neglected question soon became a most important part of the interrogation.39

Stirred by the palpable improbability of the Lille claims, VIII Bomber Command made a prompt attempt to tighten up the interrogation procedure. Although crews were interrogated immediately on their return, before their first impressions of the battle had been distorted by reflection or a creative imagination, the pattern of any considerable battle was exceedingly difficult to re-create. By the end of the year it was becoming common practice to diagram all combats resulting in claims.40 Finally, on 5 January 1943, VIII Bomber Command headquarters issued the following rules governing evaluations. An enemy plane would be counted as destroyed when it had been seen descending completely enveloped in flames, but not if flames had been merely licking out from the engine. It would be counted as destroyed when seen to disintegrate in the air or when the complete wing or tail assembly had been shot away from the fuselage, but not if a wheel or some other part of the airplane had been shot away. Experience with many an AAF plane had demonstrated that a badly wounded plane might return and land safely. Single-engine enemy planes would be counted destroyed if the pilot had been seen to bail out. The “probably destroyed” category would include planes for which no certainty of destruction existed but where the intensity of flames or extent of damage seemed to preclude chance of a successful landing. An enemy plane could be claimed as damaged when any of its parts were seen shot away. Every effort would be made to reduce future claims and to eliminate41 crediting the same German fighter to two or more gunners.

In accordance with these principles, claims registered since the beginning of operations were reviewed. By previous standards, claims for all missions through 3 January 1943 had totaled 223/88/99. The new yardstick set them at 89 destroyed (a reduction of 60.1 per cent), 140 probably destroyed, and 47 damaged,42 a revision which did much to satisfy critics on both sides of the Atlantic.43 Even so, the figures were still too high, as has already been indicated in the case of the Lille mission of 9 October. That mission and an attack against Romilly-sur Seine on 20 December* were the most important in respect to claims in

* See below, pp. 256–58

the period before 3 January. Together they accounted for adjusted total claims of 42/52/22. Enemy sources reveal, however, that the total score was possibly no more than three planes destroyed and one damaged, and certainly no more than seven destroyed and eleven damaged.* Even under the new directive of 5 January, claims continued to be often inaccurate and seldom on the conservative side, a conclusion supported by a check of enemy records of critical air battles falling within the limits of this Volume.†

The failure to develop a more reliable method of estimating enemy losses was of grave significance. Public relations were inevitably involved. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the evaluations, especially in the early days, reflected a natural desire, existing all along the line from the combat crew to AAF Headquarters, to prove the case for daylight bombing. Inflated reports, widely published, sometimes had to be corrected to the embarrassment of the AAF. But the figures on GAF losses, however newsworthy, were not collected to adorn headlines; they constituted a type of intelligence indispensable for the strategic planner, and it was in realization of the need for accurate data that Eighth Air Force leaders strove to correct current mistakes. Those efforts did much to instill into the minds of crew members a more conservative attitude. The story (probably apocryphal) is told of a gunner on the Wilhelmshaven raid of 27 January 1943 who, on observing an intercepting enemy plane blow up not a hundred yards from the bomber, nudged a comrade who had been firing at it and asked “Do you want to claim that one?” – to which the second gunner replied “No, I didn’t see it crash.”44 Claims continued to run excessively high, as will be shown in subsequent accounts of the great air battles of 1943–44, but in general the mistakes seem to have derived from an honest failure to solve the problem of reporting and evaluating a most complex operation.

Whatever concern Eighth Air Force leaders may have had for favorable publicity they realized the experimental nature of their early operations and attempted to interpret the data revealed by them in as

* The figures, based upon returns compiled by the General Quartermaster’s Department of the German Air Ministry, are exclusive of planes destroyed or damaged on the ground at Romilly.

† At the author’s request, the record has been checked by the British Air Ministry for the following missions in addition to those already indicated: Wilhelmshaven (27 January 1943); Bremen (17 April); Kiel (14 May); Bremen (8 October); Gdynia, Anklam, Marienburg (9 October); Münster (10 October); Schweinfurt (14 October).

nearly a scientific fashion as possible. That effort was reflected in the Eighth’s employment, as early as October 1942, of civilian experts trained in statistical analysis and in various other scientific disciplines pertinent to the study of the operations of a strategic bombing force. The work of this group, called originally the Operational Research Section, did not bear fruit until 1943, but during that year it was responsible for a review of many operational problems which led to significant tactical developments. The desire for full and reliable operational data led also to the development of a standardized mission report which consolidated all pertinent information from the combat units and the several staff sections. Compiled for current use of the tactical analyst, these reports have since become for the historian a source of invaluable information. So complete, indeed, were the mission reports and so accurate in most respects other than claims on enemy losses, that the historian rarely finds it necessary to utilize the operational records of the lower echelons. Upon completion of the first twenty-three missions (17 August to 23 November) an attempt was made to consolidate all valuable information on each mission and to analyze certain significant problems raised by three months of operations. This report, called “The First 1100 Bombers,” affected in turn the system of mission reporting. It has been used extensively as a source for this chapter.

Even before compiling that report the Eighth Air Force had begun to take stock. Whatever the score in combat may have been by early October, the first fourteen missions had been on the whole very encouraging. Targets had been attacked with reasonable frequency, especially during the first three weeks, and hit with a fair degree of accuracy. During the first nine missions, the Germans had evidently refused to take the day bombing seriously. The American forces had been small and the fighter escort heavy, and so the Germans had sent up few fighters, preferring to take the consequences of light bombing raids rather than to risk the loss of valuable aircraft. And when the German fighters did take to the air, they exhibited a marked disinclination to close with the bomber formation.45 The bombing had been more accurate than most observers had expected.46 Indeed, it was a tribute of sorts to the accuracy of the Americans that after the ninth mission enemy fighter opposition suddenly increased. And it was a source of satisfaction to the AAF commanders that the B-17’s and the B-24’s appeared more than able to hold their own against fighter attacks, even with a minimum of aid from the escorting aircraft. As for antiaircraft

defenses, at no time had they presented a serious threat to the bombers. After the tenth mission a marked increase in damage became apparent, but as yet the day bombers had suffered nothing to compare with the losses reported by the RAF on their night raids at lower altitudes.47 No heavy bombers had been lost from flak, and only minor damage had been sustained. On the other hand, six aircraft were destroyed by enemy fighters. It began to look as if altitude alone might provide decisive protection against antiaircraft; but events were to demonstrate that this forecast was too hopeful.

Eighth Air Force commanders were in an optimistic mood by 9 October 1942 and, in a measure, justifiably so. Possibly the early expressions of opinion, made after the first week of operations, had been a little too sanguine. On 27 August, for example, General Eaker had informed General Spaatz that the U.S. bombers gave promise of being able to place 90 per cent of their bombs within the one-mile radius, 40 per cent within 500 yards, 25 per cent within 250 yards, and 10 per cent dead on the aiming point, or within a “rectangle 100 yards on the side.” Therefore, given a force of ten groups of heavy bombers, enemy aircraft factories could be destroyed to the point where they could not supply the field forces, and submarine activity could be “completely stopped within a period of three months by destruction of bases, factories and docks.” Granting that weather would be bad in the United Kingdom for day bombing, he believed that at least ten missions per month would be possible. Although a larger force could be handled and would be advisable, ten groups in 1942, and ten additional by June 1943, would be adequate, “coupled with the British night bombing effort, completely to dislocate German industry and commerce, and to remove from the enemy the means for waging successful warfare.”48 General Spaatz declared himself entirely in accord with this estimate and spoke of the “extreme accuracy” of the American bombers.49

AAF Headquarters in Washington received these reports with some reservations. Rather than “extreme accuracy,” headquarters agencies preferred to speak of the “fair accuracy” achieved in the first missions. Bombing had been accurate in relation to European standards rather than according to any absolute standard, an opinion which General Spaatz himself expressed on further reflection.50 Nevertheless, it was possible for analysts in the office of AC/AS, Intelligence, looking back over the entire fourteen missions, to share General Eaker’s optimism

and to accept his estimates regarding both accuracy and force required.51 These early missions had also made a noticeable impression on British opinion. If not as enthusiastic as their American allies, British observers in September and October were at least ready to admit that the AAF day bombers and the policy of day bombardment showed surprising promise. As early as 24 August, General Spaatz reported a significant change of mind on the part of the RAF. In a statement which, among other things, indicates how tentative had been the British official acceptance of the American bombardment doctrine, he stated that the RAF was now willing to alter its conception of the nature of daylight bombing operations from one wherein the bombers were to be used mainly as bait to lure the enemy fighters into action to one in which the bombing had become the principal mission and the supporting fighters were employed to further that effort rather than to attack the German Air Force.52 General Eaker wrote at about the same date that the British “acknowledge willingly and cheerfully the great accuracy of our bombing, the surprising hardihood of our bombardment aircraft and the skill and tenacity of our crews.”53

A review made by the Air Ministry of the B-17 operations from 17 August to 6 September substantiated this interpretation. It referred to the high standard of accuracy attained, considering the inexperience of the crews. It pointed to the fact that in ten missions only two aircraft had been lost, owing to the ineffectiveness of the flak at high altitude and to the ability of the Fortress to take care of itself against fighter attack “The damage caused, commensurate with the weight of effort expended, is considerable,” the report read, adding (quite rightly) that complete destruction of any of the targets attacked with the forces at present available could not have been expected. But, it concluded – with some enthusiasm though little appreciation of what the AAF hoped to accomplish in its bombing offensive – if only these Fortresses were employed on night operations the effectiveness of the area bombing program could be raised from its current rate of 50 per cent to 100 per cent, and a decisive blow could be dealt to German morale during the coming winter54 British press opinion, which in mid-August had been cool, if not hostile, to the day bombing project, showed a similar change of tone.

On 1 September, Colin Bednall wrote in the Daily Mail as follows: “So remarkable has been the success of the new Flying Fortresses operated

by the US AAF from this country that it is likely to lead to a drastic resorting of basic ideas on air warfare which have stood firm since the infancy of flying.”55 Peter Masefield, whose comments on the eve of the first Fortress mission had been decidedly critical of the American bombers and patronizing towards their capabilities, revised his judgment frankly, but somewhat more gradually.56 Prior to the Lille mission of 9 October he stoutly maintained that the B-17’s needed escort and that therefore their effective range was limited absolutely to the range of the escorting fighters. “There is no doubt [he concluded] … that day bombing at long range is not possible as a regular operation unless fighter opposition is previously overwhelmed or until we have something too fast for the fighters to intercept.” Then, he believed, but only then, the entire Allied bombing force might well be turned to day bombing.57

After the USAAF operation of 9 October he declared that the question “Can we carry day air war into Germany?” – which had hitherto been answered in the unqualified negative – was now subject to a new assessment. It might be that altitude and firepower could some day make deep penetrations of enemy territory feasible. Several factors, however, still limited the range of the U.S. bombers: any raid to Germany would as yet have to be conducted beyond effective fighter range; long distance flights would give the enemy warning system sufficient time to work at maximum efficiency; bomber ammunition would likely run low in protracted encounters with enemy aircraft which would be free to attack in the most effective manner, unhampered by escort fighters; and finally weather over Europe between November and March was “not particularly favourable for high-flying operations.” Thus true air superiority remained confined to the range of the fighter, and cloud and darkness still offered the best cover for bombing attacks. But Masefield ended his article of 18 October in a pliable frame of mind. “The Americans have taught us much; we still have much to learn – and much we can teach. “58

This cooperative attitude on the part of the British the Eighth Air Force found encouraging in itself, for it was absolutely essential to the success of any combined campaign that the two partners should work together without friction, each possessed of a substantial faith in the other’s doctrines and equipment. General Spaatz was keenly aware of this fact. After the first week of operations he reported confidently that the American air forces had demonstrated that they could conduct

operations in close cooperation and harmony with the RAF. And, somewhat later, he expressed concern over what he believed to be an increasing habit among Americans of belittling the RAF and its bombing effort. Without underwriting everything done by the British, he pointed out that they were in a position to speak with authority on bombing operations and that, in point of fact, the RAF was the only Allied agency at the time steadily engaged in “pounding hell out of Germany.”59

Limiting Factors

If, as General Eaker said, both the RAF and the Eighth Air Force were more cheerful over the daylight bombing offensive “than had been thought possible a month ago,” many problems had yet to be faced before that offensive could be declared a success or, indeed, before it could be given an unquestioned place in the military scheme of things. Some of these problems could be solved, others could at best be only borne with hopefully and patiently: together they contributed an undertone of solemn seriousness to the chorus of official optimism. Among those which might presumably be solved in time was that of training; but it was still a major problem. The 97th Group had begun operations with inadequate preparation, and the new groups as they arrived in the United Kingdom and became operational found themselves in little better position. For want of time, none had been fully trained before leaving the States. Weather in the British Isles discouraged training in high-altitude flying, and facilities were lacking there for conducting realistic practice in aerial gunnery. The result was that much of the training in high-altitude flying, in high-altitude bombing, and in aerial gunnery had to be done on combat missions against a real enemy. Once combat operations had been begun, the lack of an adequate flow of replacement crews made it necessary to alert the same men on every mission scheduled, which was normally as often as weather permitted. It was consequently hard to keep up a regular schedule of training. It soon became evident that the place to perfect aircrews and units was in the United States, not in the United Kingdom, and efforts were accordingly made to shape training in the Zone of the Interior along lines indicated by experience in the theater.60

Another problem was involved in developing U.S. fighter support for the day bombers. Although of slight immediate importance to the activities of the Eighth Air Force in the fall of 1942, the concept of

U.S. fighter support was fundamental to the notion of a day bomber offensive. No matter how well the bombers had done in their early missions in combat with fighters, it was still regarded as a matter of the utmost urgency to provide them with as much protection for as great a distance into enemy territory as possible. It had long been axiomatic in the AAF that the primary role of American fighters in the ETO would be to escort bomber missions. To accompany missions deep into Germany it was essential to develop a suitable long-range fighter, and great things were hoped from the P-38. The priority given to TORCH for all such equipment made the operation of the fighters for the time being, however, of academic interest only, for they were virtually all withdrawn to the North African project in October. But the problem of the fighters remained one of the greatest significance for the bomber offensive from the United Kingdom.

During most of the period covered by this chapter the Eighth Air Force had an assigned strength of four fighter groups. Only one, however (the 31st, equipped with Spitfires according to an agreement between the AAF and the RAF), saw considerable action, flying 1,286 sorties prior to its removal to Africa in October and being credited with three enemy planes destroyed, four probably destroyed, and two damaged. The other three (the 1st and 14th with P-38’s and the 52nd with Spitfires) did not come to grips with the GAF during their short stay in Great Britain, although they flew several sorties over enemy territory.61 In addition, many American pilots had been serving in Eagle squadrons with the RAF. These units, equipped with Spitfires, were formally taken over by the VIII Fighter Command on 29 September 1942 and organized into the 4th Fighter Group.62

The Spitfire pilots, though operating some aircraft (the V-B) which were inferior to the FW-190, went into combat with confidence in their planes.63 The situation was not nearly so simple with the P-38. The RAF did not at first like the P-38. As in the case of the American bombers, early showings in the United Kingdom had been unfortunate. When, however, certain modifications had been effected, the P-38 became potentially as good a plane as any in the theater, a fact which the British themselves admitted.64 Yet suspicion of the P-38 still lurked among the U.S. pilots, fostered in part by hearsay and in part by a couple of bad accidents involving improperly manipulated power dives.65 Only actual combat experience was likely to dispel doubts in both AAF and RAF minds.

General Spaatz was therefore very anxious to get the P-38’s into action as soon as possible without committing them prematurely. Any fighters that went out over enemy territory ran the risk of tangling with the best of the German Air Force pilots; so it was necessary to give the Lightning pilots careful training in cross-Channel flights before sending them into a real battle.66 Bad weather and mechanical failures delayed their entry into combat, but after 16 September they became fully operational and flew on several missions before being removed to the North African project in October.67 Their contact with the enemy was slight, however, and no conclusions could be drawn. As of 14 September the four fighter groups of the VIII Fighter Command were transferred to the XII Fighter Command for shipment to North Africa. They continued to operate under the VIII Fighter Command until 10 October. Only the 4th Group, consisting of former Eagle pilots, remained in. the United Kingdom.68 It was many months before a significant force of AAF fighters was able to operate regularly from the British bases.

The development of a self-sufficient U.S. fighter force may have been essential to the plan of 8 September for the day bomber offensive, but it was not essential to the immediate prosecution of the campaign itself. If the basic fighter units were removed for TORCH, RAF units remained to provide cover for the American bombers. But TORCH constituted nevertheless a threat to bombing operations from the United Kingdom, the gravity of which can hardly be exaggerated. Immediately that TORCH was approved, it became evident that preparation for the North African operation would for an indefinite period take priority over all other air activities in the United Kingdom. On 8 September, General Spaatz issued specific orders to this effect, and although the order was rescinded a few days later, it appeared for the time being that tactical operations of the Eighth Air Force, including combat missions, would be completely suspended.69 Each command in the Eighth Air Force and each section in its headquarters was given responsibility for processing corresponding agencies in the new Twelfth Air Force. In addition to the four fighter groups contributed directly to the Twelfth, the older air force was scheduled also to lose two heavy bombardment groups (the 97th and 301st) after the first week in November and two more at a later date.70

Thus the drain on the combat strength of the Eighth Air Force caused by the TORCH operation was both direct and indirect. The

loss of two groups would reduce the heavy bomber strength by one-third – and combat effectiveness by an even larger proportion, since these were the two oldest and most experienced bomber units in VIII Bomber Command. The indirect effect involved in processing the Twelfth Air Force units was even more devastating. As General Eaker stated on 4 January 1943, VIII Bomber Command staff offices had been devoting half their time to supervising the training, supply, and maintenance of XII Bomber Command. The combat crew replacement center, from which combat units were supposed to draw necessary replenishment, had given first priority to the TORCH units which had to be built quickly up to strength.71 The Twelfth Air Force also enjoyed priority in organizational equipment, spare parts, and aircraft replacements; and the VIII Air Force Service Command was spending by far the greater part of its effort on the TORCH units, in addition to contributing large numbers of trained men and quantities of equipment.72 As a result, servicing and maintenance for VIII Bomber Command aircraft became slow and uncertain, preventing the most effective employment of such bombers as were on hand and increasing the likelihood of abortive sorties. Faced with shortages in almost every category, the VIII Bomber Command ground crews often had to resort to “cannibalism” – the dismantling of damaged aircraft, dubbed “hangar queens.” It was the opinion of some group commanders that if crews had not shown extreme energy and ingenuity in this regard at least half of the bombers maintained on operational status would have been out of combat.73 The VIII Fighter Command had been assigned the specific task of dispatching units to Africa, and this effort, in addition to the loss of four out of five groups, promised to render it practically useless as far as operations from the United Kingdom were concerned until the movement had been completed.74

Almost more depressing than the demands of TORCH to those whose duty it was to keep up a bombing offensive from the United Kingdom was the weather in that region. Unlike TORCH, this handicap was to be recurrent. Favorable weather was an absolute prerequisite to successful day bombing, at least until more efficient methods of blind bombing had been discovered than any yet developed. It had been with the full knowledge of this fact that the USAAF had projected its scheme for a day bombing offensive from the United Kingdom. But the weather in the fall of 1942 seemed – and British observers claimed that it was – unusually bad.75 Fewer operational days had

turned up in September than had been hoped for, and as October progressed, the situation only grew more disheartening.76

By early October it was seriously debated whether it was feasible to conduct a full-scale offensive of this sort from British bases, especially in view of the fact that a successful North African campaign might be expected to open up a very attractive alternate base area in that quarter. To offset such a defeatist attitude General Eaker wrote on 8 October that weather should not cause too much alarm. There were, he maintained, five to eight days in every month favorable to maximum effort at high level, which was about all the current rate of replacements would allow in the best of circumstances. This represented a more cautious estimate than that of ten missions a month made in August, but General Eaker hoped to keep the enemy from resting during the interim periods of relatively bad weather by developing a highly trained and skilled intruder force, capable of employing bad weather as a cloak for small blind-bombing operations.77 Plans were in fact already made for these “moling” missions which, it was hoped, by the use of the most advanced navigational and bombing devices, would make it possible for single B-24’s to keep enemy air raid systems and defensive establishments on the alert and so interrupt enemy industrial production.78

What bothered the Eighth Air Force commanders most about both the diversion to TORCH and the bad British weather was that, for a successful day bomber offensive, time was of the essence; and on both counts vital time seemed likely to be lost. Every month of delay in mounting a full-scale offensive against German industry gave the enemy just that much time in which to redeploy his forces and to readjust his techniques to counter the Allied attack. So far the GAF had reacted to the daylight attacks of the Eighth Air Force with less alacrity and with less deadly effect than had been generally anticipated. The GAF kept barely one-fourth of its total day fighter strength on the western front during the fall of 1942, preferring to concentrate its forces on the two land fronts in Africa and Russia. Furthermore, it showed no signs of reinforcing the fighters on the western front, even after the pattern of Eighth Air Force bombing activity had become evident and its seriousness at least partially appreciated. By the end of the year the German fighter defenses in the west were still deployed in a relatively thin line from Norway to Brittany, with some concentration in the Pas de Calais area and in Normandy, both of which areas defended,

among other things, the route to Paris. Nor had it been too difficult for the daylight bombing missions to avoid disastrous concentrations of enemy fighters. Although the high-level bombing mission was, almost from its time of take-off, an open secret to the German radar detectors, it had been possible by diversionary sweeps and deceptive measures to confuse the enemy as to the identity and size of the main attacking force. Medium bomber attacks accompanied by fighter sweeps had generally succeeded in drawing off a number of German fighters that might otherwise have tangled with the heavy bombers. And a radio countermeasure known as “moonshine,” employed by a small force of RAF Defiants in order to make themselves appear to German controllers as a large heavy bomber formation, worked very well as an evasion technique until November 1942.79

These facts seem to have made the task of penetrating enemy fighter defenses look deceptively easy to American observers. To some it appeared possible that the day bombers might after all be able to penetrate German fighter defenses without their own fighter protection. It was strongly suggested in Washington that the GAF was actually on the wane, that the fighting on the land fronts, coming on top of the earlier air action in the west, had forced the enemy to cut heavily into its stored reserves in order to maintain its front-line strength.80 This estimate, though since shown to be in error, was not without justification for it was not until 1943, after the strategic day bombing by the Eighth Air Force became an unmistakable threat, that the German high commander took seriously to build up the total GAF fighter force or to redeploy it to strengthen the western front. Even if true, of course, a decline in the strength of the GAF would in itself have been a strong argument for pressing the attack before the enemy could rebuild his forces. Beneath this optimism, however, lay a sober respect for the resiliency and intelligence of the GAF. The Germans had it in their power to do either of two things: they could increase their production of fighter aircraft, at the expense of other types if need be,81 or they could build up a strong force of heavy bombers in order to strike back at the British cities. In either case, time would be required to reorganize production. One of the alternatives seemed, however, inevitable; and it occurred to General Spaatz that the Germans might well profit by the lessons in daylight bombing delivered so recently and convincingly by the Eighth Air Force. By adding firepower and armor to their four-engine FW 200s they might act against the United Kingdom

before the American forces could exploit their current technical advantage. “Daylight bombing,” he wrote on 16 September, “with the same accuracy as we have gotten and with the same casualty ratio in air fighting would raise hell with this island. We must hit their aircraft factories before Spring and it requires a large number of B-17’s to attempt this.”82

Thus the picture presented by the day bombing offensive just after the mission against Lille on 9 October was one of sharply contrasting lights and shadows. During the rest of the month the shadows tended, in a sense quite literally, to lengthen. On the 25th, General Arnold requested a full explanation of the small number of missions recently carried out. The answer merely recounted the problems and obstacles that had been faced increasingly during the previous weeks: the weather, the demands of the TORCH movement, and the inadequate training status of the remaining units.83 Owing to unfavorable weather, only one mission had been accomplished since 9 October.84 The RAF reported that no reconnaissance photographs of any value had been turned over to its bomber command since the middle of September as a result of the consistently poor visibility.85

By 1 November, too, the inroads made by the Twelfth Air Force on the strength of the older organization had become more apparent. In addition to four fighter and two heavy bomber groups, the Eighth Air Force had turned over trained personnel to the extent of 3,198 officers, 24,124 enlisted men, and 34 warrant officers, of whom 1,098 officers, 7,101 enlisted men, and 14 warrant officers came from the VIII Bomber Command alone.86 The remaining heavy bombardment groups (the 44th, 91st, 92nd, 93rd, 303rd, 305th, and 306th) suffered considerably from loss of such essential equipment as bomb-loading appliances and transport vehicles. They suffered even more from the complete lack of replacements, both crews and aircraft, a fact which made it impossible to keep a large force in the air even when weather conditions permitted; and no prospect was in sight of receiving any during November.87

Of the heavy bombardment groups scheduled to be left in the United Kingdom (five groups of B-17’s and two groups minus one squadron of B-24’s), only two were by the end of October in fully operational status.88 It had been found necessary to give two to three weeks’ extra training to all new units in formation flying at high altitude, in radio operation, and in aerial gunnery. And even as the crews

gained in experience it was the policy of the Eighth Air Force to send them out only in circumstances for which their state of training had made them fit. General Eaker believed that nothing could be gained by dispatching green units when conditions of weather or enemy defenses would only cause inordinate loss. For the same reason it was not thought wise to undertake missions that would require landing or take-off in darkness, an attitude which seriously limited the time available for operations during the short fall and winter days.89

Furthermore, the scope of Eighth Air Force missions had been restricted to a relatively narrow area in occupied France and the Low Countries which could be reached in a short time, with the bombing formation exposed to attack only for brief periods, and which, presumably, did not as yet possess such strong defenses as might be expected in Germany proper. Unfortunately, this otherwise necessary restriction prevented the bomber command from making use of occasional streaks of fine weather over more distant targets and over Germany proper at times when France and the Netherlands were completely closed in. Restrictions in the area and time of attacks simplified the GAF’s problems of defense.

It was confidently hoped that a force of sufficient size and training to saturate enemy defenses would remove many of the limitations. Such a force would permit deeper penetrations into Germany and a consequently wider choice of weather conditions. General Spaatz hoped it would also allow operations at lower altitudes beyond the range of the fighter escort, with a consequent increase in the effectiveness of the attacking force.90 Given a force of 300 heavy bombers flown by trained crews, General Eaker believed he could attack any target in Germany by day with less than 4 per cent loss. Smaller numbers would naturally suffer more severely. Despite all problems and currently effective limitations, he stoutly maintained that “daylight bombing of Germany with planes of the B-17 and B-24 types is feasible, practicable and economical.”91

Meanwhile it was a question either of committing valuable crews and aircraft prematurely to operations over heavily defended territory and in bad weather or else of proceeding cautiously as training status and rate of replacements would permit effective operations of wider scope. General Eaker preferred the latter alternative, for to adopt the former would be not only to incur crippling losses but to ruin “forever” the “good name of bombardment.”92

It would [he wrote to General Stratemeyer somewhat earlier in October] have been very easy for us to commit the force in such a way that improper conclusions would have been drawn from day bombardment. We knew the critical aspect of our task and the fact that it might affect the whole future of day bombardment in this war. The way we are doing it we are going to draw conclusions – some have already been drawn – which will be entirely favorable to the power of bombardment. Please do not let anybody get the idea that we are hesitant, fearful, laggard or lazy.

In other words, these early missions were less important for what they contributed directly to the Allied war effort than for what they contributed indirectly by testing and proving the doctrine of strategic daylight bombing. In either instance it was as difficult and dangerous to strive for quick results as it was natural for observers, especially those at some distance from the scene of operations, to look impatiently for them.

New Directives

On 20 and 29 October 1942, Eighth Air Force received two significant directives governing the scope of its operations and the priority of its targets. The directive of 20 October, issued by General Eisenhower as theater commander and acting as agent for the CCS in the matter of bombing policy, did nothing more than the directives issued during August to clarify the strategic policy underlying the daylight bombing operations – its relation, for example, to a joint British-American offensive such as had been adumbrated in the Joint Directive of 8 September. It did, however, reflect the immediate urgency of TORCH as the currently important item of Allied strategy.

In order to move the huge amounts of men, supplies, and equipment from the United Kingdom to North Africa, it was necessary to protect that movement from both submarine and aircraft attack. Accordingly, General Eisenhower required the Eighth Air Force, as a matter of first priority, to attack the submarine bases on the west coast of France from which the major portion of the German Atlantic fleet operated: Lorient, St. Nazaire, Brest, La Pallice, and Bordeaux. Secondary targets for missions against the above bases would consist of shipping and docks at Le Havre, Cherbourg, and St. Malo. In second priority came the aircraft factories and repair depots at Meaulte, Gosselies, Antwerp, and Courcelies and the airfields referred to as Courtrai/Wevelghem, Abbeville/Drucat, St. Omer/Fort Rouge, Cherbourg/Maupertuis, Beaumont/Le Roger, and St. Omer/Longuenesse.

Transportation targets and marshalling yards in occupied countries were left in third place.93

This directive committed the Eighth Air Force for the immediate future to the support of TORCH. By naming enemy submarine bases as targets of first priority it also committed the Eighth indefinitely to strategic bombing of an essentially defensive order in place of the direct offensive attack on the industrial vitals of the German war machine. The increasing submarine menace threatened the entire logistical plan for Allied operations in Europe and Africa. It constituted Germany’s most powerful weapon against the Allies’ ocean-borne forces and supplies. It had, as a result, featured conspicuously in Allied strategic planning during the fall of 1942. The early directives issued to the Eighth had all included submarine targets. On 13 October, General Eisenhower informed General Spaatz that he considered the defeat of the submarine “to be one of the basic requirements to the winning of the war.” He appreciated the importance of striking the GAF but, as he made clear in subsequent discussions, that objective must be considered as an intermediate one, something that must be dealt with in order to get at the primary objective which must be the enemy submarine fleet – at least for the duration of the North African operation.94 It was a new point of view for the Eighth; earlier plans had called submarine installations – like the Luftwaffe – an “intermediate” objective.

Conferences between American and RAF commanders resulted in general agreement that, inasmuch as the British bombing force could not operate against bases in the Bay of Biscay during daylight hours owing to limitations of equipment and since night bombing of such targets would be ineffective, they should be left to the daylight bombers of the Eighth Air Force. Meanwhile, the RAF Bomber Command would operate against submarine manufacturing centers and other allied installations in Germany itself. Spaatz and Eaker were both confident that their heavy bombers could do the job. It would, of course, involve penetrations beyond the range of fighter protection, but experience to date with enemy fighters had been encouraging. Still, relatively heavy casualties would have to be accepted; and heavier losses would probably postpone seriously current designs for bombing Germany proper.95

On 29 October, the Eighth Air Force received still another directive, this time regulating its missions against targets in occupied countries. The problem with which this paper dealt was a delicate one. Objectives

vital to Germany’s war effort existed in occupied France and the Low Countries, and it had been a point of tactical policy to restrict American bombing effort to these areas. But it was impossible, even with greater precision than the U.S. bombers were as yet capable of, to insure the safety of civilians and their property in the neighborhood of the targets. Thus, there arose a political problem which threatened radically to affect bombardment plans.

In an effort to prepare the French population, some warning had been given by radio. On 7 October 1942, two days before the Lille raid, the British Broadcasting Company included in its broadcasts to Europe a message of warning from the American high command. AAF bombing, it stated, was aimed only at Nazis and those activities in France and other occupied territory which helped support the German war effort. It advised all French people living within two kilometers of factories supporting the German war machine to vacate their homes, since bombing small targets from great altitudes would doubtless be attended by some inaccuracy. Targets especially liable to attack were factories manufacturing or repairing aircraft, tanks, vehicles, locomotives, firearms, or chemicals. Railway marshalling yards, shipyards, submarine pens, airdromes, and troop concentration centers were also likely to be bombed.

French opinion had nevertheless been deeply stirred as a result of the bombing at Rouen, at Lille, and again at Lorient, in each of which civilian French casualties had been distressing, if not always extremely numerous; at Rouen some 140 were killed, at Lille approximately 40, and at Lorient a few Frenchmen were numbered among the 150 dead, more than half of whom were Germans, the rest Belgian and Dutch.96 Naturally the French viewed the bombing of their cities with mixed emotions, the mixture varying pretty much with the severity of their own losses. Although generally happy in a grim sort of way to see any damage dealt the Nazis, even in their own land, many Frenchmen found it hard to take a long-term view of the situation when American bombs fell on French property and took French lives. The Germans leaped at this opportunity to poison French minds against the Allies, covering walls with posters which featured the civilian deaths and civilian sufferings attendant upon the American bombing. The controlled press did its best to keep the bitterness alive. Even those who understood the strategic necessity for the Allied bombing felt that, in planning such missions, the sorrow and destruction suffered by the

French should be carefully weighed against the doubtful results to be attained from bombing at extremely high altitudes. It was on this point that most French criticism seemed to be concentrated in the fall of 1947. French observers could not help believing that as long as bombing attacks were made at 25,000 feet only a small percentage of bombs were likely to hit the target; and results had not as yet been such as to persuade them to the contrary.97 Some also urged, apparently quite seriously, that bombing of factories and shipyards should be done only on Sundays and holidays when French workmen would be absent.98