Section 4: Supporting Operations

Blank page

Chapter 14: Air Support for the Underground

The collapse of formal resistance to German aggression over most of the European continent early in the war had forced into exile or “underground” patriotic elements of the population which refused to accept defeat. To maintain contact with these persons, to encourage them in the organization of effective resistance, and to draw upon them for sorely needed intelligence from an enemy-dominated continent had been a major concern of the Allied governments since 1940. In that year the British government had established a Special Operations Executive (SOE),in whose office lay the over-all responsibility for a variety of operations that were convemently and most safely described as “special.” Similar in function was the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS), established in 1942, whose Special Operations (SO) branch in London cooperated with SOE. Special Force Headquarters (SFHQ),a joint organization staffed by SOE/OSS personnel, was charged with developing resistance in France and the Low Countries. The story of these organizations and of the underground movement itself falls outside the province of this history, but a large part of these special operations depended upon the airplane for their execution, and the assistance provided by the RAF and AAF constitutes a chapter in the history of air warfare as significant as it is unique.

Operating in an element beyond the control of surface forces, the airplane enabled the Allied governments to reach across borders that were otherwise closed to them. The RAF had begun special operations early in the war, and as all preparations for OVERLORD were stepped up in the fall of 1943 the AAF assumed a major share of the work. Chiefly it delivered freight – guns, ammunition, explosives, medical

supplies, and other items valuable in guerrilla warfare – from bases in Britain, Africa, or Italy to the Maquis in France and to the Partisans of northern Italy or the Balkans. But the task was also marked by an infinite variety of duties. Regular or specially equipped planes carried secret agents “Joes” and an occasional “Jane” – to points within enemy lines, and brought out, in addition to agents whose jobs had been accomplished, Allied airmen forced down in enemy territory, escaped prisoners of war, or wounded Partisans for hospitalization. The success of the entire program of special operations depended upon establishing liaison and channels of information between SOE/OSS and the resistance movements and upon coordination of underground activities with Allied plans. These objectives were accomplished by foreign and native agents who dropped or landed from special-duty aircraft and gave direction to resistance movements or served in less prominent but still significant roles. Agents bent on sabotage or espionage, organizers of patriot groups, weather observers, radio operators, aircrew rescue units, and formal military missions made up most of the “bodies” transported by aircraft devoted to special operations. The reverse process, evacuation of personnel from enemy-occupied countries, provided opportunities for firsthand reports, further training of agents, and refinement of plans through consultation with experienced personnel. And to these varied activities was added the task of delivering psychological warfare leaflets in territory wholly or partly occupied by the enemy.

Leaflet Operations from the United Kingdom

Dropping leaflets by aircraft was one of the more novel means of waging warfare during World War II. This method of delivering information and propaganda to friend and foe in enemy-occupied areas was used in every theater, but western Europe, with its many large centers of population and its concentrations of Axis troops, promised the greatest returns. In every area of the European theaters – from North Africa to northern Norway and from the Channel Islands to eastern Germany and Yugoslavia – Allied aircraft in thousands of sorties dropped billions of leaflets. The British, skilled in the coinage of military slang, called these leaflets “nickels,” and the process of delivering them by aircraft became known as “nickeling.”

Civilian agencies were responsible for leaflet production in England before the Normandy invasion; but after D-day, when tactical and

strategic factors were even more important than political considerations, most of the leaflets were produced by the Psychological Warfare Division of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Forces (PWD SHAEF). The leaflet section of PWD had its own writing team, controlled the operations of a special AAF squadron, and had a packing and trucking unit to service Britain-based aircraft with packages of leaflets and packed leaflet bombs1

Many types of nickels were used in psychological warfare. Classified according to general purpose, there were strategic and tactical leaflets. Strategic leaflets dropped before D-day were intended to weaken the will of the German people to resist and to raise morale in conquered nations. After D-day, this type of leaflet was used to deliver the su-preme commander’s communications to civilians, to provide accurate and contemporary news of the campaign, and to guide widely spread subversive activities behind the enemy’s lines. Before D-day, 43 per cent of the strategic leaflets went to France, 7 per cent to the Low Countries, and most of the remainder to Germany; after D-day, 90 per cent of the strategic leaflets were dropped over Germany, and the remainder fell to the French, Belgians, and Dutch.2 Many of the strategic leaflets were small single sheets which bore brief but pointed messages.3

Newspapers, such as the Frontpost, and single sheets in great variety made up the tactical leaflets; but three sheets were considered as basic: the “Passierschein” or safe-conduct, “One Minute Which May Save Your Life,” and “This Is How Your Comrades Fared.”4

Nickeling operations from the United Kingdom had their beginning in a small RAF mission over Kiel on the night of 3/4 September 1939. Four years later, in August 1943,the Eighth Air Force began to participate in this form of psychological warfare and by 6 June 1944 had dropped 599,000,000 leaflets over the continent. Although both medium and heavy bombers carried leaflets on regular combat missions, the task fell chiefly to the Special Leaflet Squadron, which had reached the theater in 1942 as the 422nd Bombardment Squadron (H) of the 305th Group and was transferred to special operations in the fall of 1943.* By June 1944 it had become an experienced night-flying unit, and between the Normandy invasion and the end of the war it dropped over the European continent a total of 1,577,000,000 leaflets. The total

* It flew its missions out of Chelveston until 25 June 1944, when it moved to Cheddington. A final change of station took it to Harrington in March 1945. The squadron was redesignated as the 858th Bombardment Squadron (H) on 24 June 1944, and on 11 August 1944 it changed numbers with the 406th Squadron.

distribution for the same period by heavy bombers on regular daylight missions was 1,176,000,000. With an additional 82,000,000 dropped by Ninth Air Force mediums, the grand total for the AAF after D-day greatly exceeded the 405,000,000 dropped during the same period by the RAF. Indeed, at the end of hostilities AAF units had dropped more than 57 per cent of the 5,997,000,000 leaflets carried to the continent by aircraft based in the United Kingdom.5

The earliest method of leaflet distribution consisted of throwing broken bundles from windows, doors, or bomb bays at high altitudes. In the first leaflet raids, pilots of B-17’s and B-24’s threw out leaflets when the planes were seventy-five miles away from a city, trusting that the wind would do the rest. Some of the propaganda dropped over France was picked up in Italy.6 A slight improvement came when leaflet bundles were placed in crude boxes and released through a trapdoor attached to a bomb shackle; but it was not until Capt. James L. Monroe, armament officer of the 422nd Bombardment Squadron, invented the leaflet bomb that a fully satisfactory method of distribution was found.7 The new bomb, which came into regular use on the night of 18/19 April 1944, was a cylinder of laminated wax paper, 60 inches long and 18 inches in diameter. A fuze that functioned at altitudes of 1,000 to 2,000 feet ignited a primer cord which destroyed the container and released the leaflets. Each bomb could hold about 80,000 leaflets which would be scattered over an area of about one square mile. The Special Leaflet Squadron’s bombers were modified to carry twelve leaflet bombs, two more than the load of a regular bomber. Early in the summer of 1944, a metal flare case was converted into a leaflet bomb for medium and fighter-bombers.8

The Special Leaflet Squadron began operations on the night of 7/8 October 1943 with a mission of four aircraft to Paris. By the end of December, the squadron had conipleted 146 sorties and had dropped 44,840,000 leaflets, most of them over France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Only three missions crossed over into western Germany during this period.9

During the first quarter of 1944, the Special Leaflet Squadron devoted most of its efforts to France, where Paris, Rouen, Amiens, Reims, Lille, Orléans, and Rennes were especially favored. Sorties went as far south as Toulouse and southeast to Grenoble.10 From 1 January to 31 March 1944, the Eighth Air Force dropped 583 short tons of propaganda.11 The 422nd Bombardment Squadron extended the scope of its operations considerably in April and “attacked” Norwegian

targets with the leaflet bomb. The number of cities nickeled per mission also increased until it was common for fifteen to twenty-five to be scheduled as targets for a five-plane mission.12 In May, the last full month before D-day, four of the leaflet-droppers were attacked by enemy planes. These attacks caused a few casualties, damaged one bomber, and resulted in destruction of one FW-190 and one Ju-88. Still the Special Leaflet Squadron had not lost a plane in 537 credit sorties over a period of eight months.13

The 422nd Bombardment Squadron was, in a sense, the spearhead of the Normandy invasion. Led by the squadron commander, Lt. Col. Earle J. Aber, early on the morning of 6 June its planes went over the beachheads singly and unescorted to drop warnings to the people of seventeen villages and cities. That night the squadron set a new record with twelve B-17’s nickeling thirty-four targets in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands14 Missions of eight to ten planes were not uncommon in June and by the end of the month the squadron had set a record of 209.6 tons. This total was surpassed in July, when the first plane was lost. Beginning in August 1944, a large proportion of the squadron’s sorties was flown to drop combat leaflets over the battle areas and strategic leaflets to the German home front.15

The campaign to disseminate propaganda to the German people was further intensified in November. The 406th Bombardment Squadron, as the 422nd had now been designated, was raised in strength to twentyone aircraft and twenty-four crews, a change made possible by transferring seven planes and crews from the 492nd Bombardment Group. The result was to increase the squadron’s tonnage to 315.3 for the month, a record that was not surpassed until March and April16 Two factors exercised a decided influence on leaflet activities in December – bad weather and the German offensive in the Ardennes. The first hampered activities and the second made the usual tactical “leafleting” inopportune. The 406th Squadron dropped no leaflets at all in the salient but flew four missions to other parts of the front from 16 to 27 December. Then, when the German offensive had been stopped, it delivered 3,250,000 copies of Nachrichten to the enemy’s scattered forces. Special leaflets, rushed into print to aid the Allied counteroffensive, were also delivered by the RAF and AAF strategic bombers in large quantities.17

Both the regular bombers and the Special Leaflet Squadron set new records for leaflet-dropping during the last four months of the war.

The all-time high for the AAF came in March, with 654.9 tons; in April, the total was 557.3 tons. German, French, Dutch, and Belgian targets were visited frequently. Colonel Aber was killed by “friendly” flak over England on 4 March 1945 while returning from a mission to the Netherlands, thus ending a brilliant career as leader of a unit to which had been assigned a difficult and important role in the air war. In spite of this loss and a move from Cheddington to Harrington, the 406th Squadron dropped 407.9 tons of leaflets in March.18 When its operations ended on 9 May 1945, the Special Leaflet Squadron had flown 2,334 sorties and had dropped about 1,758,000,000 leaflets. Losses were low, with only three planes missing and sixteen flyers killed.19

CARPETBAGGER Missions to Westen Europe

Although AAF special operations from the United Kingdom began in October 1943 with a leaflet-dropping mission by the 422nd Bombardment Squadron, the major effort was to be devoted to the delivery of supplies, under the code word CARPETBAGGER and in accordance with a CCS decision of the preceding September.20 When plans to implement this decision were being made, General Eaker had available the 4th and 22nd Antisubmarine Squadrons of the 479th Antisubmarine Group, which had been disbanded following the dissolution of the AAF Antisubmarine Command in August.* From these two squadrons came the personnel and some of the B-24’s for the original CARPETBAGGER squadrons. The Eighth Air Force activated the 36th and 406th Bombardment Squadrons as of 11 November 1943 and attached them as a subgroup to the 482nd Bombardment Group (Pathfinder) at Alconbury. Several changes, both in station and in organization, occurred in February and March 1944. Shortly after having moved to Watton in February, the CARPETBAGGERS were assigned to the VIII Air Force Composite Command, with the 328th Service Group as administrative headquarters. On 28 March, the 801st Bombardment Group (H) (Prov.) was established as a headquarters under command of Lt. Col. Clifford J. Heflin, and the two squadrons moved to Harrington.21 At the end of May 1944, two more squadrons, the 788th and 850th joined the CARPETBAGGERS and raised their strength to more than forty B-24’s.22

In an extensive shifting of unit designations in August 1944, the 801st Bombardment Group became the 492nd Bombardment Group and the squadrons were numbered 856th, 857th, 858th, and 859th.23

* See Vol.II, 409.

Equipment peculiar to antisubmarine or routine bombing missions was discarded for such new installations as Rebecca, a directional air-ground device which records radar impulses on a grid to direct the navigator toward a ground operator whose sending set is called Eureka, and the S-phone, a two-way radio which provides contact with a ground phone. By December 1944, practically all special-duty aircraft were equipped with Rebecca sets, although as yet a sufficient number of Eurekas could not be delivered to the resistance forces on the continent.24 On the CARPETBAGGER planes the ball turret was removed and a cargo hatch, called the “Joe-hole” because parachutists dropped through it, was made by placing a metal shroud inside the opening. Other modifications included installation of a plywood covering to protect the floor, blackout curtains for the waist-gun windows, blisters for the pilot’s and co-pilot’s window to provide greater visibility, and separate compartments for the bombardier and the navigator. All special navigational equipment was rearranged to provide greater ease of operation, waist and nose guns were removed, and the planes were painted a shiny black. Crews were required to spend some time in familiarizing themselves with the modified bomber and with the use of its special equipment.25 The CARPETBAGGERS flew their first mission to France from Tempsford on the night of 4/5 January 1944, and by 1 March they had completed twenty-nine supply sorties.26

In the next three months, CARPETBAGGERS completed 213 of 368 attempted sorties, most of which were flown to supply patriot groups in France north of the Loire River.27 The number of successful sorties rose sharply after the 788th and 850th Squadrons joined the 801st Bombardment Group at Harrington on 27 May in anticipation of the greater demands for support of the French patriots that would follow the landing of Allied armies on the continent. During July, when the peak of operations was reached, the four squadrons in 397 sorties dropped at least 4,680 containers, 2,909 packages, 1,378 bundles of leaflets, and 62 Joes.28 The shiny black B-24’s flew on twenty-eight nights, sometimes through weather normally considered impossible for flying. August operations were somewhat smaller than the record set in July, since much of the area theretofore served had fallen into Allied hands. Occupation of most of France and Belgium by September 1944 brought full-scale CARPETBAGGER operations to an end with missions flown on the night of 16/17 September.29 In addition to its supply and leaflet-dropping missions, the unit flew a few C-47 landing sorties. The first of these missions tookplace on 8 July and the last on 18

August. During this period the group’s four C-47’s completed thxty-five sorties to twelve landing fields in liberated territory, delivered sixty-two tons of arms and ammunition, took in seventy-six passengers, and evacuated 213.30

Upon completion of its full-scale supply operations to the patriots, the 492nd Bombardment Group turned to delivery of gasoline and other items for the Allied armies and to medium-altitude night bombing. One squadron, the 856th, was held available for further CARPETBAGGER sorties and received the group’s C-47’s for the evacuation of Allied aircrews from Annecy. This squadron operated practically as an independent unit under the Eighth Air Force, performing such OSS missions as were required. Although the 856th Squadron flew two sorties to the Netherlands in November and early December, its CARPETBAGGER missions were not resumed to any extent until 31 December. Then one B-24 dropped supplies and personnel in Norway and two flew to Denmark. By 5 March 1945, the squadron had completed forty-one sorties to these countries. The 856th was returned to control of the 492nd Group on 14 March, and thereafter all three squadrons – the 859th had gone to Italy in December 1944 – were to be available for both special operations and standard bombing.31 Detachments of the 856th and 858th Squadrons flew out of Dijon, France, from 19 March to 26 April to drop agents into Germany, but the rest of the CARPETBAGGERS at Harrington continued to concentrate their effort on Norway and Denmark.32 Many of the Norwegian missions were for the purpose of dropping small parties of Norwegian-speaking paratroopers on the Swedish border.33

A statistical summary of the CARPETBAGGER project does not reveal its intensely dramatic character. Some of that drama came from encounters with night fighters, from the deadly flak of concealed antiaircraft batteries, and from the exploits of crews in escaping capture or in fighting as members of the Maquis. Far greater interest centers upon the reception committees waiting tensely for the sound of a B-24’s motors, on German patrols attempting to break up the underground organization, and upon the acts of sabotage made possible by airborne supplies. The CARPETBAGGERS alone are credited witfi having delivered 20,495 containers and 11,174 packages of supplies to the patriots of western and northwestern Europe. More than 1,000 agents dropped through Joe-holes to land in enemy territory. To accomplish these results, the CARPETBAGGERS completed 1,860 sorties out of 2,857

attempted. From January 1944 to May 1945, twenty-five B-24’s were lost, an average of one to every 74.4 successful sorties, and eight were so badly damaged by enemy action or other causes that they were no longer fit for combat. Personnel losses totaled 208 missing and killed and one slightly wounded.34 Many of those listed as missing parachuted safely and later returned to Harrington with patriot assistance in escaping from Europe.

All CARPETBAGGER missions were planned in minute detail to insure maximum coordination of effort. Requests for supply drops originated either with field agents or at various “country sections” at the Special Force Headquarters in London where there was a section for each country that received airborne supplies. The chief of Special Operations, OSS, and his counterpart in SOE determined the priority of missions. Targets were pinpointed and then forwarded to Headquarters Eighth Air Force for approval. Upon receipt of an approved list, the air operations section, OSS, sent it on to the CARPETBAGGER group headquarters where the S-2 plotted the targets on a map. The group commander then decided whether the proposed missions were practicable, selected targets for the night’s operations, and the S-2 telephoned the information to OSS, which might suggest changes. After the target list had been settled, the appropriate country section notified its field agents to stand by and to listen for code signals broadcast by the BBC. Upon receipt of these signals, reception committees went to the designated drop zones to receive the supplies.35 An OSS liaison officer with the CARPETBAGGERS arranged for containers and packages to be delivered to the airdrome from the packing station near Holme. Packages, leaflets, and parachutes were stored in Nissen huts on the “Farm” near the airdrome perimeter; containers for arms and munitions and other supplies were stored at the bomb dump. The group armament section loaded packages and leaflets on the aircraft while containers were being fitted with chutes and loaded by the ordnance section. The OSS liaison officer checked each aircraft to be certain that the proper load was in place. The leaflets, usually carried as part of each load, were delivered to the field under direction of PWD SHAEF from the warehouse at Cheddington. Personnel to be parachuted, escorted by OSS agents, were fitted with their special and cumbersome equipment by the armament section and then placed in charge of the dispatcher who was to supervise their drop through the Joe-hole. When fully loaded, a B-24 CARPETBAGGER carried

about three tons of supplies, one or more Joes, and six to ten 4,000 leaflet bundles.36

In the end, success of the effort depended upon nearly perfect coordination at the point of delivery between the aircrews and reception committees. The latter groups varied in size according to the enemy interference expected, the quantity of supplies to be delivered, and other factors of a local nature. The Maquis committee usually had twenty-five men for each fifteen containers, which was the standard load of one supply bomber.37 The committees prepared drop zones, lighted signal fires or laid out panels, maintained contact with the aircraft and with resistance leaders, and arranged for recovery and removal of the supplies. Identification of the DZ was one of the principal problems. Pilots were guided to the pinpoint by S-phone contact and by the help of Rebecca/Eureka equipment; signal fires at night generally were burning before the aircraft reached the DZ and served as an invaluable aid. Many times, however, the DZ was either surrounded by the enemy or was in danger of being detected. On such occasions the fires were not lighted until identification signals had been exchanged. The aircraft, whether fires were lighted or not, circled over the pinpoint flashing the letter of the day. Upon receiving the proper response by Aldis lamp or flashlight, the crew prepared for the drop. The pilot let down to 700 feet or less, reduced his air speed to about 130 miles per hour, and flashed the drop signal to the dispatcher. Several runs over the target were required to drop the entire load, and some accidents were unavoidable while flying on the deck at near-stalling speeds. A steady stream of reports from reception committees provided a check on accuracy and revealed the reasons for unsuccessful sorties. Most of the reports told of missions completed, but some revealed the chagrin of patriots whose work had been nullified by betrayal to the Gestapo, appearance of a strong enemy patrol, or aircrew errors.38

Mass Drops of the 3rd Air Division to the Maquis

The Eighth Air Force greatly increased the quantities of supplies delivered to the Maquis during the period 25 June-9 September 1944 by diverting heavy bombers from bombing operations. These critical weeks in the invasion of France found the Maquis fighting in ever increasing strength to divert enemy troops and committing numerous acts of sabotage to hinder German military movements to the main battle areas. In the struggle for St.-Lô, which ended on 18 July, French

Forces of the Interior (FFI) prevented large numbers of German troops from reinforcing the front, and in the Seventh Army’s later drive northward toward Lyon, the FFI protected the right flank. Supplies previously received from the United Kingdom and North Africa were insufficient to support the desired scale of activity, but the Eighth Air Force, by diverting B-17’s from strategic bombing for mass drops on selected targets, delivered the additional materials required.

Shortly after the Normandy invasion (on 13 June, to be exact), SHAEF had received word that the Maquis lacked only supplies to enable them to play a major role in the battle for France. The underground already controlled four departments and fighting was in progress in several others. A conservative estimate placed the number of armed Maquis at 16,000, and the number awaiting arms at 31,800. Potential recruits might raise the total to more than 100,000.39 By ex-tending the range of their missions to Chiteauroux and the Cantal area southeast of Limoges, the CARPETBAGGERS could maintain about 13,500 Maquis in south-central France; but it was estimated that by diverting B-17’sto supply operations an additional 34,000 could be maintained by some 340 sorties monthly. Virtual control of all southern France seemed possible, and even partial control promised to threaten enemy communications in the area, endanger the German position on the Franco-Italian border, divert enemy troops from Normandy, and provide an airhead on the continent for use by Allied airborne troops.40

These arguments convinced SHAEF that the effort should be made. On 15 June the Eighth Air Force was ready to provide 75 B-17’s for the task, and three days later 180 to 300 B-17’s were promised. The 3rd Air Division, to which the job went, assigned five wings of thirty-six aircraft each to deliver the supplies. Crews received hasty training in CARPETBAGGER methods while Special Force Headquarters transported loaded containers to airdromes, arranged for communications and signals with the Maquis, and selected the targets most in need of supplies. Each of the five wings, it was estimated, could arm 1,000 to 1,200 men with rifles, machine guns, rocket launchers, ammunition, grenades, and side arms.

Five target areas were selected for Operation ZEBRA, the first of the mass drops by B-17’s to the Maquis. In the Cantal region west of the Rhone, heavy fighting had been going on since 3 June. Southeast of Limoges an uprising by the Maquis had stopped rail traffic on D-day, but subsequent fighting had exhausted FFI supplies. In the Vercors, the

entire population was in revolt. Southeast of Dijon, Maquis were unusually active in disrupting traffic. The mountainous Ain area west of Geneva had been practically liberated by 14June, when the Maquis were forced to fall back to more inaccessible ground, and the department of Haute-Savoie south of Geneva was almost entirely in FFI control by 18 June. Fighting in these regions had reduced Maquis supplies to a dangerously low level.41

Originally scheduled for 22 June, Operation ZEBRA was postponed for three days because of unfavorable weather. Then, with fighter escort provided at set rendezvous points, 180 B-17’s took off at about 0400 on 25 June in clear weather. One plane was lost to flak, another fell to an enemy fighter, and two others failed to complete the mission. In all, 176 B-17’s dropped 2,077 containers on four targets. Lack of reception at the Cantal target caused the wing scheduled for that point to drop with another wing southeast of Limoges.42

Operation CADILLAC, the second mass drop by B-17’s of the 3rd Air Division, took place on 14 July. At this time with the battle for St.-Lô reaching its climax, the Maquis could give valuable assistance by continuing to disrupt enemy troop movements and by engaging the maximum number of German forces. Fighting was heavy in the Vercors, where the Nazis were making a strong effort to eliminate the threat to their communications northward in the Rhone and Saône valleys, southwest of Chalon-sur-Saône, and in the area of Limoges. Operation CADILLAC was planned to deliver supplies to seven points in these three principal regions. Nine wings of thirty-six B-17’s each were assigned to the operation and each wing loaded six spares to insure a maximum drop. The bombers took off at about 0400 from nine airdromes, picked up a fighter escort of 524 P-51’s and P-47’s, and flew to their targets in daylight. The only opposition was that offered by some fifteen Me-109’s which attacked southwest of Paris. The bombers and fighters together claimed nine of the Me’s shot down, two probables, and three damaged. Two of the B-17’s landed in Normandy, and all told only three planes suffered major damage. Two wings of seventytwo B-17’s dropped 860 containers on the Vercors plateau, and one wing of thirty-six B-17’s dropped 429 containers southwest of Chalon-sur-Saône. The remaining 214 B-17’s dropped 2,491 containers on five targets in the Limoges–Brive area. Practically all of these 3,780 containers, loaded with nearly 500 tons of supplies, were recovered by reception committees.43

A third mass drop, Operation BUICK, occurred on 1 August 1944. The 3rd Air Division assigned five wings of thirty-nine B-17’s each to drop on four targets. One wing went to the Chalon-sur-Saône area, where the FFI had won control over the Saône-et-Loire department by using the munitions delivered on 14 July; another wing dropped 451 containers west of Geneva. In Savoie in the Alps, 5,000 Maquis had fought an eight-day battle with an equal number of the enemy in Jannary 1944. The patriots had been forced to disperse because their supplies were exhausted; but they reorganized in May and had 5,500 waiting for arms. To this group, thirty-nine B-17’s dropped 463 containers, and seventy-five B-17’s delivered 899 containers to Haute-Savoie. In all, 192 B-17’s made successful sorties to drop 2,281 containers at a cost of six planes slightly damaged.44

One other Eighth,Air Force operation, which supplemented regular supply-dropping, is worthy of note. This took place on 9 September to a drop zone twenty-five miles south of Besancon. By this time the FFI controlled a score of departments and were growing stronger. The rapidly moving Seventh Army had overrun many of the drop zones; but the Besancon area, on the route to Belfort and Colmar, was not yet cleared of Germans. To this drop zone, six groups of twelve B-17’s each dropped 810 containers.45

These four mass drops, important though they were, lend particular emphasis to the significance of the earlier and continuing effort by special units, both of the RAF and the AAF, to keep alive the resistance movement and to prepare it for a major part in the expulsion of the Germans from France. And to that effort organizations operating from Mediterranean bases had made their own special contributions.

Special Operations in MTO

Special operations from Mediterranean bases to southern France had been conducted on a very limited scale prior to September 1943, when SOE/OSS agents operating among the Maquis pressed Allied Force Headquarters for greater deliveries. The RAF stationed a detachment of 624 Squadron at Rlida near Algiers for aid to the Maquis, but from 1 October to 31 December 1943 this unit succeeded in only seven of its attempts.46 A Polish flight of four Halifaxes and two Liberators arrived in North Africa in November, primarily for missions to Poland, and in that month the British formed 334 Wing as headquarters to command nearly all special-duty aircraft in the theater.47 The RAF and Polish

units moved to Brindisi in southeastern Italy in December 1943 and January 1944, leaving a detachment of 624 Squadron at Blida.48

The question of AAF participation in supply operations having been under consideration in the Mediterranean theater before 334 Wing was organized, General Eaker, on his transfer from ETO, gave close attention to the problem. The 122nd Liaison Squadron, a remnant of the Twelfth Air Force 68th Reconnaissance Group, had participated in special operations on a very limited scale since November 1944,49 and General Eaker in January 1944 requested authority to reorganize the 122nd Squadron into a heavy bombardment unit for assignment primarily to missions in support of the Maquis.50

General Arnold approved the request, and the 122nd Bombardment Squadron (in June redesignated the 885th) was activated on 10 April 1944, under command of Col. Monro MacCloskey. Based at Blida, the unit was attached to the Fifteenth Air Force.51 In February the British had concentrated 624 Squadron at Blida, to which base other RAF units later were assigned. A liaison section, called Special Projects Operations Center (SPOC), coordinated RAF and AAF activities, determined target priorities within the area selected by squadron commanders for a night’s missions, and contacted field agents who prepared the reception parties.52

By May 1944 the 122nd Bombardment Squadron was in full operation. During that month it completed forty-five sorties in seventy-two attempts. Weather and poor navigation were responsible for some failures, but inability to contact reception committees was the principal explanation for missions listed as incomplete.53

An increase in the supply of Eurekas to the Maquis brought an improvement of the record thereafter, and further help came from the designation of dumping grounds to be used as alternate targets when contact with reception committees failed. In areas selected for dumping, there were few Germans and the Maquis could be informed as to the exact location of the drop by radio. This practice ended in August when German withdrawal gave the Maquis greater freedom of movement.54

Since missions to the Maquis differed little except in details, one experience of the 885th Bombardment Squadron may be taken as typical. On the night of 12/13 August, less than three days before the Seventh Army invasion, the squadron was assigned the task of delivering last-minute supplies and dropping leaflets over French cities to alert the FFI of the Rhone Valley and along the coast. Eleven aircraft took off from Blida on a moonless night, flew individually to assigned pinpoints,

and dropped 67,000 pounds of ammunition and supplies, eighteen Joes, and 225,000 leaflets. For that night’s work the squadron received the Presidential unit citation.55

As was true with the CARPETBAGGERS, Allied success in France reduced the number of sorties flown from Mediterranean bases to the Maquis after the middle of September 1944. The 885th Bombardment Squadron, in its operations from 5 June to 13 September, had completed 484 sorties out of 607 attempts, dropped 193 Joes and 2,514,800 pounds of arms and ammunition. Additional deliveries were made after the 885th was moved to Brindisi in September, but the move itself gave notice of the greater importance now given to northern Italy and the Balkans. The combined RAF/AAF effort from MTO in behalf of the French resistance movement resulted in 1,129 successful sorties out of 1,714 attempts, the dropping of 578 Joes, and the delivery of a gross tonnage of 1,978. The RAF suffered eight aircraft lost, while the 885th Bombardment Squadron lost but one B-24.56

Two squadrons (7th and 51st) of the 62nd Troop Carrier Group had been sent from Sicily to Brindisi in February 1944 for operations in support of the Balkan Partisans. The AAF squadrons were attached to 334 Wing of the RAF, which had been delivering supplies to the Balkans for several weeks. Wing headquarters prepared flexible daily target lists with stated priorities within each list. Squadron or group commanders and operations officers attended daily meetings to select targets for their squadrons from the list, after which an operations schedule was prepared.57 Weather and availability of aircraft determined the number of targets for each mission. On night missions, the number of C-47’s averaged about thirty-five from April through October 1944; occasionally as few as four and as many as fifty were airborne. The number of targets averaged about fifteen for this period, and one to three planes dropped on each target.58

Supplies carried to the Balkans consisted principally of guns, ammunition, dynamite, food, clothing, medical supplies, and specialized equipment; but gasoline, oil, jeeps, mail, and even mules were included in the cargo when landing operations later became frequent. The weight of stores carried by a C-47 varied from 3,000 to 4,500 pounds net, and there was usually an additional 150 pounds of propaganda leaflets.59 Stores were kept in warehouses at Brindisi where Partisans, generally evacuees who had come to Italy for medical care, packed the supplies.Astock of some 8,000 bomb-rack containers and 25,000 fuselage

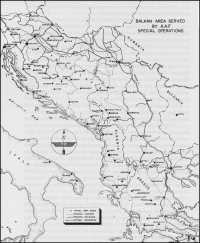

Balkan Area Served By AAF Special Operations

packages, known as standard packs, was kept on hand in anticipation of field requests.60 Each morning the air loads section at Paradise Camp, as the warehouse area was called, assembled maximum loads for scheduled sorties according to data received from SOE/OSS head-quarters. Each load was picked up by a truck, checked at the loads control hut, and delivered to the designated aircraft where a British checker supervised a Partisan loading team. Whereas C-47’s were loaded under British supervision by Partisans, the 885th Bombardment Squadron upon its removal to Brindisi was supplied from an OSS dump located adjacent to the dispersal area and operated by squadron personnel61

Assignment of AAF C-47’s to supply operations had helped to solve a critical situation for the rapidly growing Yugoslav Partisans. No. 334 Wing had been unable to meet all of the requests for missions, primarily because there were not enough special-duty aircraft under its control. Unfortunately, the 7th and 51st Troop Carrier Squadrons experienced a period of bad weather in February and March which caused 62 failures in 186 sorties and required another 97 scheduled sorties to be canceled. Nevertheless, the two squadrons succeeded in 82 attempts and dropped a gross weight of 374,900 pounds of supplies, leaflets, and personnel to all targets. Most of the targets lay in central and southern Yugoslavia, but sorties were flown to Albania, Greece, Bulgaria, and northern Italy. Lack of reception and incorrect signals combined to cause 41 failures, but pilots made every attempt to deliver their loads, even at the risk of inviting enemy action.62 On the night of 1/2 March, for example, two C-47’s of the 7th Troop Carrier Squadron took off for a drop zone seven miles north of Tirana in Albania. The first pilot to arrive located the pinpoint, flashed the signal, but received an incorrect reply. He “stooged” for nearly ninety minutes waiting for a correct signal, then returned to base with his load. The other pilot located the signal fires some distance from the pinpoint, but during his runs on the target the reception committee moved the fires to a new location.63 These two experiences bore eloquent testimony to German vigilance and to Partisan audacity in defying enemy patrols.

The four C-47 squadrons of the 60th Troop Carrier Group arrived at Brindisi between 16 March and 5 April 1944 to replace the 7th and 51st Squadrons, and they flew their first sorties on the night of 27/28 March to drop leaflets over Italy and the Balkans. Supply missions, beginning the following night, initiated a period in which the troop carriers

were to deliver more than 5,000 short tons of supplies to the Balkans.64 A month’s operations by each of two squadrons may be taken as typical of the 60th Troop Carrier Group’s activities from 29 March to 17 October 1944. In April the 10th Troop Carrier Squadron flew 74 sorties and completed 42, all but 9 of which went to Yugoslavia.65 In June the 11th Troop Carrier Squadron flew 142 of its 170 successful sorties to Yugoslavia to deliver more than 246 short tons of supplies.66

The technique of supply-dropping to the Balkans varied little from that used by the CARPETBAGGERS’ except for a heavier dependence on landing rather than dropping operations. Unlike most of the drop zones in western Europe, those in the Balkans, and in northern Italy as well, frequently were located in narrow valleys surrounded by peaks and ridges. Transport pilots rarely failed to find their assigned pinpoints, and the Partisans, in no small part because of the munitions supplied by air, were able to set up definite lines of resistance which gave protection to a number of semipermanent and well-organized strips that remained under Partisan control for considerable periods of time.67 The first AAF transports to land in the Balkans, two C-47’s of the 60th Troop Carrier Group, came down on a rough strip near Tito’s headquarters at Drvar on the night of 2/3 April 1944.68

Subsequently, MAAF organized special service teams for the development and maintenance of strips as a part of the Balkan Air Terminal Service (BATS), which was placed under control of the Balkan Air Force on its organization in June 1944.” Most of the thirty-six landing grounds used at various times in Yugoslavia were prepared and operated by BATS teams.69 There was no way, however, to eliminate the special hazards of night operations. In addition to danger from enemy night fighters and ground fire, most of the fields were so located that only one approach was possible. Failure on that one attempt meant a wrecked plane and death or injury for its occupants. No night-flying facilities existed, except for fires to mark the rude runways and an occasional electric flare path. Nevertheless, night landings, as well as escorted daylight sorties, steadily increased in number, and in the period 1 April-17 October 1944 the 60th Troop Carrier Group completed 741 landings, practically all of them in Yugoslavia.70

The Partisans made heavy demands upon 334 Wing from May to September 1944, a period in which the Germans endeavored to liquidate

* See above, p. 399.

Marshal Tito’s forces. One enemy offensive began late in May and was directed against Tito’s headquarters at Drvar and other points in Slovenia and Bosnia. When these efforts failed, the Germans turned their attention to Montenegro in a July offensive which coincided with the beginning of operations by the Balkan Air Force.71 The BAF not only gave considerable tactical aid to the Partisans but also escorted transports on daylight landing missions. Maximum effort by the BAF, which exercised operational control over 334 Wing, could not prevent the Partisans from losing ground in Montenegro during August, when the 60th Troop Carrier Group delivered more than 620 short tons of supplies to Yugoslavia or about 75 per cent of its total Balkan effort.72 In 145 successful landings, most of them in Yugoslavia, the 60th Group also evacuated more than 2,000 persons to Italy.73 An unusual feature of the month’s operations was the delivery of twenty-four mules and twelve 75-mm. guns to two very difficult landing grounds in Montenegro. The weather was exceptionally bad, and the landings required flying on instruments between two jagged peaks at the destination.74

The strategic situation changed suddenly between 23 August and 5 September, when Rumania and Bulgaria capitulated before the swiftly advancing Russians. As the Germans directed their attention to extri-cating their exposed forces, the Allies endeavored to take full advantage of this turn of events during September, the last full month of the 60th Troop Carrier Group’s tour at Brindisi. Tito’s divisions in Montenegro and Serbia began to drive northeast to link up with the Russians advancing on Belgrade from western Rumania, and the BAF flew more than 3,500 sorties that resulted in heavy damage to German communications and transport.75 No. 334 Wing delivered 1,023 short tons of supplies to Albania and Yugoslavia, more than one-half of which was carried in AAF C-47’s. The 60th Troop Carrier Group made about 125 landings on Yugoslav grounds and evacuated some 1,500 persons.76 Three of the squadroils were withdrawn from Partisan supply missions on 8 and 10 October to take part in Operation MANNA, the British occupation of southern Greece. The 10th Troop Carrier Squadron continued its assistance to the Partisans until 25 October.77

Operation MANNA became possible because of the German withdrawal, and not because of successful Partisan activity on any considerable scale. The RAF had started supply missions to Greek patriots late in 1942, and by March 1943 a more or less regular flow of material was arriving for resistance groups organized by SOE agents. AAF C-47’s

completed 367 dropping and landing sorties to Greece betufeen February and November 1944, and the 885th Bombardment Squadron flew 35 successful sorties to the peninsula in October. Together the transports and bombers delivered about 900 short tons of supplies, which was approximately one-third of total Allied deliveries to Greece.78

A review of the 60th Troop Carrier Group operations for the period 29 March-17 October 1944 reveals the cumulative importance of its supply missions. More than 5,000 short tons of supplies were delivered to the Balkans, of which approximately three-fourths went to Yugoslavia and Albania. Some of these supplies were to maintain Allied missions and agents, but diversion for that purpose represented a coniparatively small percentage of the total. Landing operations began on a small scale in April with eighteen successful attempts, then increased rapidly: 50 in May, 125 in June, 194 in July, 145 in August, and 128 in September. In view of the hazards encountered, the loss of ten C-47’s and twenty-eight men was very low. This average of one C-47 lost for each 458 sorties was a remarkable record that testified to the pilots’ skill in evading enemy flak, night fighters, and mountain peaks and to the faithful performance of ground crews. Of about 1,280 incomplete sorties, only 58 were attributed to mechanical failure, 661 were caused by bad weather, and 486 by reception failures.79

During the last period of supply operations to the Balkans, from 17 October 1944 to the end of the war, the AAF assigned both transports and heavy bombers to the work. The 885th Bombardment Squadron completed its move from North Africa to Italy early in October; its primary mission thereafter was to supply distant targets in northern Italy and Yugoslavia. The 7th Troop Carrier Squadron, which had taken part in Operation MANNA, resumed special operations from Brindisi on 22 October and was followed five days later by the 51st Troop Carrier Squadron. The 7th left Brindisi early in December, but the arrival of the 859th Bombardment Squadron from the United Kingdom partially compensated for this loss. Replacing the 51st Troop Carrier Squadron at the end of March 1945, the 16th Troop Carrier Squadron of the 64th Troop Carrier Group continued supply-dropping until the end of the war.80 Three AAF squadrons, therefore, were available for missions to Yugoslavia through March; thereafter, the 16th Troop Carrier Squadron was the only AAF unit thus engaged.81 Squadrons flying supplies to the Balkans encountered a period of bad weather which canceled many missions during the third week of October

1944, and in November less than one-half of the days were operational. In spite of this handicap, the two C-47 squadrons succeeded in putting up 312 sorties during the period ending 30 November, of which more than 75 per cent were successful, and about 386 short tons of supplies were landed or dropped on widely separated drop zones.82 Among the more notable landings were those at the Zemun airdrome on the edge of Belgrade. Zemun was rough, but not as bad as a strip near Skopje, where on one occasion twenty oxen were required to pull a C-47 out of bomb craters. In December, the 51st Troop Carrier Squadron completed forty-four landing sorties to a ground some fifteen miles north of Gjinokastër, Albania.83 While the 51st Troop Carrier Squadron was concentrating its attention on close targets in Albania, the 885th Bombardment Squadron served the more distant Yugoslav drop zones. Most of its 256 successful sorties from 18 October to 31 December 1944 went to the Zagreb and Sarajevo areas, although on 3 December the squadron flew a thirteen-plane daylight mission to supply Partisans near Podgorica in the south.84

Division of responsibility among the supply-droppers was more carefully drawn early in January 1945, in time to meet the critical situations that developed in connection with the German withdrawal from the Balkans. The 51st Troop Carrier Wing, assigned to MATAF, was given a primary responsibility for the 15th Army Group’s area in Italy. The 15th Special Group (Prov.) operated under MASAF until the middle of March and was then transferred to MATAF and redesignated 2641s Special Group. The 859th and 885th Bombardment Squadrons of this group served both Italy and the Balkans, although the 859th was to give first priority to the Balkans and the 885th was to concentrate its effort on Italian missions. Units under 334 Wing devoted their attention to the Balkans primarily, with second priority to northern Italy. One AAF troop carrier squadron, the 51st and then the 16th, remained on duty with 334 Wing.85

During the period 1 January-11 May 1945, AAF C-47’s and bombers flew nearly 1,000 sorties to Yugoslavia and Albania, although missions to the latter practically ceased in January, and delivered 1,685 short tons of supplies by landing and dropping.86 The 16th Troop Carrier Squadron in April set a new record for C-47 performance over the Balkans when it completed 183 of 196 sorties.87

Receipt of supplies from southern Italy was an important factor in Partisan successes in Yugoslavia and Albania. Although the Partisans

captured large quantities of stores from the enemy and significant amounts were taken in by surface craft, special-duty aircraft delivered the supplies that made the difference between victory and defeat. More than 18,150 short tons of supplies were flown to Yugoslavia and more than 1,320 tons to Albania. To accomplish this, Allied supply planes flew 9,t 11 successful sorties in 12,305 attempts. Eighteen aircraft were lost in Yugoslav operations and seven on Albanian missions.88 At least ten AAF C-47’s and two B-24’s are included in this total89 The 51st Troop Carrier Wing and the 2641st Special Group (Prov.) delivered somewhat less than one-half of the total tonnage to Yugoslavia, while C-47’s dropped or landed 65 per cent of the supply taken to Albania.90

The Germans were unsuccessful in the countermeasures adopted to decrease the flow of airborne supplies to the Partisans. Their difficulty may be understood when one recalls that there were at least 322 drop zones and landing grounds in Yugoslavia alone.91 These grounds were by no means secret; but enemy patrols and armored columns sent out to capture them, bombers dispatched in attempts to crater the landing strips, and night fighters undertaking to intercept the transports achieved only limited success.92

Aid for Italian Partisans

Poorly organized and scantily supplied, the Italian resistance movement was far less important to the Allies than its counterpart in Yugoslavia. Italy was a major battleground with well-defined combat lines manned by regular troops. These conditions, so different from those that prevailed in the Balkans, severely restricted Partisan activities except in limited areas. Not until the enemy had lost Bologna and was in full retreat across the Po Valley did the Partisans of town and country find opportunities to make a material contribution to Allied victory. While waiting for these opportunities, bands of anti-Fascist guerrillas harassed the enemy’s communications, perfected their own organization, harbored Allied agents, transmitted information to the Allies, and aided flyers in escape and evasion.

Organization and supply of these Partisan groups were functions of SOE and OSS. Until after the Salerno invasion in September 1943, the only special-operations flights to Italy were for the purposes of dropping agents or of delivering supplies to escaped prisoners of war. During the period extending from June to November 1943,624 Squadron (RAF) completed twenty-nine of forty-two attempted sorties to

Italy from Blida. Dropping and reception techniques used in connection with these flights were so faulty that many agents were captured and supplies often fell into the enemy’s hands. Improper location and identification of drop zones continued throughout the war to be a handicap, although well-trained officers dropped for assistance of the Partisans managed to accomplish a very real improvement in operating procedures.93

The AAF played a minor role in the support of Italian Partisan activity prior to September 1944.94 Squadrons of the 51st Troop Carrier Wing at Brindisi had completed eleven sorties to Italian targets by the end of May and flew another nineteen sorties in June.95 That the Italians were putting these supplies to good use is indicated by Marshal Kesselring’s announcement on 19 June 1944 that guerrilla warfare was endangering the German supply routes and the armament industry. He demanded that the guerrillas be suppressed with the utmost vigor, and hundreds of the Partisans were killed or captured in the resulting drive but the resistance movement was far from crushed.96 During the summer of 1944, when resistance groups in France were exerting maximum pressure on the enemy and Tito’s Yugoslav Partisans were engaged in critical battles, northern Italy was of necessity neglected. With the liberation of southern France, however, the 885th Bombardment Squadron became available for other assignments. The squadron moved from Blida to Maison Blanche, just outside of Algiers, and flew a first mission to northern Italy on the night of 9/10 September 1944. In less than two weeks it had completed thirty-six sorties which dropped nearly fifty-nine tons of supplies in the Po Valley. During the last week of September, the squadron, now operating from Brindisi, completed nine more sorties to the same area.97 Although transferred to Brindisi primarily for missions to Italian targets, the 885th often flew daylight missions to the Balkans. The weather during October seriously reduced the deliveries to northern Italy, which were usually made by night. Unfortunately for the Partisans, this period of bad weather coincided with determined German efforts to crush guerrilla activity in the Udine area in northeastern Italy and in the Ossola Valley in the northwest. The 885th Bombardment Squadron tried eighty-five sorties on the seven operational nights, but only thirty-three were successful and two B-24’s were lost in the effort to relieve the Partisans.98

Delivery of supplies in Italy increased sharply during November 1944 and remained on a high level to the end of the war. This result was

achieved by assigning the 62nd and then the 64th Troop Carrier Group to these operations and by the arrival of the 859th Bombardment Squadron from England in December. The 205 Bombardment Group (RAF), the Polish 301st Squadron, and 148 Squadron (RAF) all contributed in occasional missions to the total; but AAF units delivered practically all of the airborne supplies reaching the Italian Partisans after November 1944. Deliveries to Yugoslavia continued to be far greater than those to Italy, but the discrepancy became progressively less as the war drew to a close.99 The C-47’s, flying from Tarquinia, Malignano, and Rosignano; confined their attention largely to the area south of Turin and Piacenza, west of Modena, and north of Pisa, Lucca, and Pistoia. It was estimated that the Partisans in this area were keeping some 40,000 second and third-rate enemy troops on police duty.100 The Ligurian and Maritime Alps in the region, as well as more distant targets, were visited by the supply bombers in November and December.101

The 62nd Troop Carrier Group, stationed at Malignano and Tarquinia, loaded all of its planes at Malignano. Its first mission to north Italy was flown on 22 November when six C-47’s of the 4th Squadron, with an escort of two P-47’s, flew to a DZ near Massa. The 8th Squadron joined the 4th in this type of effort on 28 November, and the 7th followed suit on 10December. The three squadrons completed their daylight missions to northern Italy by 9 January 1945, having delivered more than 494 short tons of supplies.102 Most of the group’s sorties had been to DZs in the mountains 20 to 100 miles northwest of Pistoia, although some flights went west of Turin. Target LIFTON, about twenty-five miles north of La Spezia, received particular attention. The 7th Troop Carrier Squadron sent out thirty-eight sorties from 11 to 20 December in vain attempts to supply this target but finally succeeded in dropping no more than sixteen tons of supp1ies.103

Bad weather, as usual, was the principal cause of incomplete missions, while enemy interference and improper reception accounted for about onetenth of the failures to drop after the planes had reached the DZ’s. An escort of four P-47’s or Spitfires, which generally met the C-47’s over Marina di Pisa, provided protection from hostile aircraft but no opposition was encountered except for occasional bursts of flak.104

Italian Partisans, supplied on a scale never before attempted, increased their activities materially in December 1944. In the last week of that month, the Germans countered with a drive to clear their lines

of communication, especially around PiacenzA where two Partisan divi-sions had organized and armed some 7,000 men. The offensive scattered the Partisans and opened the roads temporarily; but while bands were reassembling northwest of La Spezia, activity increased in such distant areas as Udine and Vittorio Veneto.105

The 64th Troop Carrier Group, operating under MATAF at Rosignano, began its supply operations on 11 January 1945. When its missions ended on 7 May, the group had completed more than 1,000 sorties in which there had been dropped better than 1,800 short tons of supplies.106 During this same period the 2641st Special Group (Prov.) dropped nearly 1,260 tons.107 Most of the missions continued to be flown during daylight hours and, asbefore, wearher and reception difficulties accounted for most of the failures, The January experience of the 16th Troop Carrier Squadron was typical: of twenty-four sorties, twelve failed to receive the correct signals.108 Weather caused 50 to 142 failures for the 64th Group in February.109 Enemy opposition, on the other hand, was insignificant and but one C-47 wds lost.110

Swift disintegration of the German position in April provided the Partisans with splendid opportunities to aid the Allied advance. Guerrillas captured large quantities of enemy material, thus freeing themselves of a heavy dependence on air supplv, but far to the north there were more or less isolated groups which co&inued to depend upon supplies dropped by the 2641st Special Group. New targets were opened for the B-24’s in the Alps, where Partisans were disrupting traffic toward the Brenner Pass, and in the Po Valley. Other Partisan groups were attacking the Verona–Udine–Villach withdrawal route from strongholds in the Adige and Piave valleys.111 Even after hostilities had ceased, on 2 May 1945, the supply-droppers continued to receive calls from units that had been cut off from other sources. But special operations may be considered as having ended in Italy by 7 May, During the period of hostilities, Allied special-duty aircraft had completed 2,646 of 4,268 attempted sorties to Italian targets and had dropped more than 6,490 short tons of supplies. The AAF flew 70 per cent of the completed sorties and dropped 68 per cent of the tonnage.112

Leaflets dropped by aircraft over Italy and the Balkans were similar to those delivered to western Europe. The principal purposes were to inform isolated peoples of the march of events, to counteract enemy propaganda, and to maintain morale. Among strategic leaflets dropped over Italy after the Salerno invasion were those that urged the preservation

of art treasures, informed enemy soldiers of Allied successes on other fronts, and encouraged and directed Italian Partisans in works of sabotage.113 Bombers on strategic missions and supply planes in the course of their normal operations were able to meet the need without the aid of a special leaflet squadron or the assignment of special bombers to the work. Tactical aircraft, the medium and fighter-bombers in particular, and artillery “shoots” were used extensively to nickel the enemy’s front-line positions and rear areas. Supply-droppers from North Africa, both of the RAF and the AAF, carried propaganda to southern France, and a number of purely nickeling sorties were flown to that area, most of them just prior to the Allied invasion of August 1944.114

MASAF dropped appropriate leaflets on large cities in Italy and the Balkans. Its attacks on Rome, for example, were preceded and accompanied by nickeling, and leaflets urging a general strike and sabotage of enemy communications preceded the Salerno invasion.115 Most of the nickeling by MASAF after September 1943 was carried out by the 205 Bombardment Group (RAF).116

Nearly every C-47 of the 60th Troop Carrier Group carried from 150 to 450 pounds of propaganda to the Balkans or north Italy on supply missions. Written in many languages, the leaflets were dropped on Germans, Greeks, Albanians, Yugoslavs, Bulgarians, and Italians while the planes were en route to or from their targets. A sufficient number of nickeling sorties, on each of which some 4,000 to 4,500 pounds of leaflets were carried, were flown to keep the monthly total at forty-five to sixty-eight tons. In the period 12 February-31 December 1944, the 51st Troop Carrier Wing dropped 414.4 tons on the Balkans and Italy. After the 885th and 859th Bombardment Squadrons entered Italy, they also carried nickels for PWD. In two typical months of operation, the 264 1st Special Group flew 209 successful sorties to the Balkans and 152 to northern Italy, during which its two squadrons dropped a total of 34.6 tons of leaflets.117

Infiltration and Evacuation

Infiltration of special agents by air began in 1940 when the RAF dropped operatives over France118 and grew rapidly as Allied intelligence agencies expanded and as the preliminary work of Partisan organizers began to bear fruit. The presence of “Joes” and “Janes” in (C-47’s and B-24’s became common. CARPETBAGGERS from the

United Kingdom dropped 617 Joes from January to September 1944, and by April 1945 had raised the total to 1,043. Units of the MAAF dropped or landed 4,683 Allied agents and Partisans in various Europcan countries from 1943 to 1945.119

Most of the infiltration work was mere routine for the air forces, however dramatic the experience might be for the agents, although interesting assignments appeared from time to time. The 492nd Bombardment Group participated in a few missions in 1945 that departed from the ordinary. The 856th Bombardment Squadron, operating from a base at Lyon, dropped parachutists in Germany on 21 January and, with the 858th Bombardment Squadron, flew out of Dijon from 19 March to 26 April. During this period the two squadrons dropped eighty-two agents, equipped with radios, at key locations in Germany. Another interesting variation was the “Red Stocking” series in which pilots flew Mosquito aircraft from Dijon. These planes, equipped with recording devices, were flown at high altitudes over designated pinpoints to pick up and record messages transmitted by agents on the ground.120

Supply-droppers in Italy were called upon at times to execute special infiltration missions that varied considerably from their usual work. Operation ORATION, infiltration of the Maclean military mission* to Yugoslavia by parachute, was carried out by the RAF in January 1944.121 Another special mission, Operation MANHOLE, infiltrated a Russian military mission by glider on 23 February 1944. The Russians had arrived in Italy in two C-47’s, and General Wilson, the theater commander, agreed to facilitate their entrance into Yugoslavia. This mission was at first assigned to the RAF, which planned a daylight landing mission with C-47’s at Medeno Polje, but snow covered the strip and compelled a revision of plans. The assignment was then given to the 51st Troop Carrier Squadron, which was to provide three C-47’s for the tow of the same number of Wac0 (CG-4A) gliders. Twentyfour P-40’s from the Desert Air Force and twelve Fifteenth Air Force P-47’s flew as escort. The transports, carrying a gross load of 10,500 pounds of supplies to be dropped, took offfrom Bari with the gliders in tow on the morning of 23 February. Twenty-three Russian and six British officers were in the gliders, which made perfect landings.122 The third mission, Operation BUNGHOLE, also had been assigned

* Brig. F. H. Maclean headed a British liaison mission attached to Tito’s headquarters in September 1943.

to the RAF, but it was flown by the 7th Troop Carrier Squadron on 27 February. This required two C-47’s to drop American meteorologists and their supplies at a drop zone near Ticevo. A heavy snowstorm prevented one of the planes from locating the DZ, but the other dropped successfully.123 Landings in Yugoslavia, Albania, and Greece increased in number as the war drew to a close, and the 51st Troop Carrier Wing in effect operated an air transport service at Brindisi. Outgoing traffic consisted primarily of Allied agents and supplies; incoming traffic was largely made up of Balkan nationals and Allied airmen.

Flying agents into enemy territory was an easy task in comparison with getting them out again. The return trip was especially difficult from western Europe and Poland, although there are a few cases of successful pickups by the RAF and AAF from these areas. Most of the pickups from fully clandestine fields, as distinguished from well-established strips under Partisan control, were carried out by British Lysanders.124 But the number of agents who escaped from enemy territory by this means was far less than the number brought out of the Balkans on regular sorties.125

The principal reason for evacuation of Partisans from the Balkans was the inability of guerrilla forces to care properly for their wounded and to protect women and children threatened with extermination by Nazi and satellite forces. Although a few Partisans had been evacuated at an earlier date, chiefly it seems by the RAF, Capts. Karl Y. Benson and Floyd L. Turner of the 60th Troop Carrier Group are credited with having initiated large-scale evacuations from Medeno Polje, a strip in use since February, on the night of 2/3 April 1944.The two planes took out thirty-six evacuees, most of them wounded Partisans.126 By the end of the month fifteen transports had landed and evacuated 168 personnel, among whom were members of the Maclean mission and a Yugoslav delegation to MAAF. These operations were so successful that MAAF sent a flying control and unloading party, forerunner of the BATS, to Medeno Polje in the interest of better service.127 Successful transport landings in Yugoslavia increased by 400 per cent in May when 60 completed sorties evacuated 1,098 persons, 777 of whom were Partisan wounded. All but thirty-seven of the evacuees were brought out by the 60th Troop Carrier Group.128 Although reliable statistics are incomplete, the total number of persons evacuated from the Balkans in the period 11 April 1944–30 April 1945 was about

19,000, of which about one-half were evacuated by the 60th Troop Carrier Group in the period 1 April-30 September 1944.129 Thereafter most of the Balkan evacuation sorties were flown by the RAF, since the niajor effort of AAF C-47’s had been directed to northern Italy. The importance of evacuation to Tito is indicated by the record for August and September 1944, when 418 successful landings evacuated 4,102 wounded Partisans.130

Landing sorties were far more interesting and dangerous than routine supply drops and frequently required a high degree of courage and skill. Capt. Homer L. Moore, 28th Troop Carrier Squadron, won the DFC for his exploit on the night of 3/4 June 1944. His target was a crude strip in the bottom of a narrow valley surrounded by 300-foot hills. Captain Moore let down successfully through a thick overcast, delivered his supplies, and carried twenty-two wounded Partisans to Italy.131 Lt. Robert H. Cook, 10th Troop Carrier Squadron, lost an engine at 10,000 feet on the night of 7/8 July when he was flying a load of wounded Partisans to Italy. Losing altitude all the way, Lieutenant Cook set course for the island of Vis where he crash-landed without injuring his passengers. Lt. Harold E. Donohue, of the 28th Troop Carrier Squadron, seems to have set a record of some sort on 3 July when he loaded sixty-six Yugoslav orphans and three adults in his C-47 and delivered them safely in Italy.132

On at least three occasions special-duty aircraft responded to urgent calls from Marshal Tito for mass evacuations. The first of these oc-curred in late May 1944 at the time of the so-called seventh Gernim offensive in Yugoslavia, a drive which nearly succeeded in its attempt to capture Tito and his staff. Intensive enemy air reconnaissance on 24 May had aroused Tito’s suspicions, and he moved a part of his headquarters from the vicinity of Drvar back into mountains;133 the but the move had not been completed when the Germans struck early on the morning of 25 May. Tito and the foreign missions fled to the hills while Partisans fought off the attack. MAAF responded to Tito’s calls for aid with bomber and fighter sorties to strike enemy concentrations, shipping, dumps, and transports.134 No. 334 Wing flew emergency supply missions and prepared to rescue the Partisan and Allied fugitives who were being encircled in the Prekaja Mountains. ABATS party prepared an emergency strip in the Kupresko Valley, and while Tito’s party was assembling, C-47’s were on their way. A Russian transport from Rari landed at 2200 on 3 June, took on Tito and other

important officers, delivered them safely at Ban, and returned for another load.* Three C-47’s of the 60th Troop Carrier Group took out seventy-four persons on the same night. The group continued operations until the night of 5/6 June. The last C-47, loaded with wounded Partisans, took off just a few hours before the Germans captured the field.135

The German offensive in the Drvar area failed to achieve its objective and the principal attack then shifted to Montenegro. In the severe fighting that followed in July and August, Partisan casualties were heavy. Some 900 of the wounded finally assembled at Brezna, ten miles north of Niksic, where patriots cleared cornfields to make an emergency landing ground. On the morning of 22 August, escorted RAF Dakotas evacuated 219 of the seriously wounded. Then twentyfour AAF C-47’s arrived with emergency supplies and evacuated 705 wounded and 16 Allied flyers. A Russian air unit, currently attached to 334 Wing, took out 138 Partisans on the night of 22/23 August, raising the total to 1,078 persons evacuated. All but nineteen of this number were wounded Partisans. The Yugoslav commander, relieved of his casualties and resupplied with arms, ammunition, and food, was able to check the enemy offensive and to recover most of the lost ground.136

The next large-scale evacuation, known as Operation DUNN, took place on 25–26 March 1945. Tito requested on 21 March that about 2,000 refugees, in danger of annihilation By the retreating Germans, be evacuated from an area northeast of Fiume.137 At this time the only AAF unit at Brindisi was the 51st Troop Carrier Squadron, commanded by Maj. Bruce C. Dunn. The squadron moved to a temporary base at Zemonico airdrome, Zara, and began to fly shuttle evacuation missions on 25 March. In two days the twelve C-47’s rescued 2,041 persons and delivered more than 118 short tons of supplies. Operation DUNN completed a twelve-month period in which special-duty aircraft had rescued well over 11,000 Yugoslav refugees and casualties.138

One of the problems facing MAAF was the evacuation of Allied aircrews from the Balkans. These men were survivors who had parachuted or crashed while over enemy territory on combat missions. The problem was especially acute through most of 1944,when heavy air strikes were made on such targets as Ploesti, Klagenfurt, Sofia, and

* Marshal Tito was back in Yugoslavia by the middle of June, presumably having been returned by a Russian plane.

other objectives in or near the Balkans. Chetniks and Partisans both aided aircrews who escaped capture, fed them and tended to their wounds as well as possible, and frequently gave them assistance in reaching the Adriatic coast. From September to December 1943, the Fifteenth Air Force processed 108 evaders who had made their way back to base from Italy and the Balkans. During the next five months, more than 300-evaders were brought back, most of them in April and May.139 This great increase in the spring of 1944 was a direct result of landing operations by special-duty aircraft.

Allied agencies in the Balkans participated in the rescue and evacuation of aircrews in addition to their other duties, but it was not until 24 July 1944 that a unit was created solely for this work. On that date General Eaker directed the Fifteenth Air Force to establish Aircrew Rescue Unit (ACRU) No. 1.140 The first ACRU field party was dropped on the night of 2/3 August in chetnik territory about fifty-five miles south and slightly west of Belgrade. About 100 American flyers, with several refugees of various nationalities, had assembled in thzt area during July and were awaiting evacuation. The ACRU field party prepared a landing strip while other evaders gathered, and on the night of 9/10 August four C-47’s landed with supplies. A total of 268 men, all but 42 of whom were Allied flyers, were evacuated from the strip.141

Special-duty aircraft continued to evacuate Allied aircrews for the duration of the war, but most of the work was in conjunction with regular supply missions. Aircrew evacuation by all agencies in the Mediterranean theater reached a peak in September 1944, although August was the heaviest month for special-duty aircraft. In Septem-ber alone, over a thousand Americans were evacuated from Rumania by B-17’s in Operation REUNION,* and nearly 300 Allied flyers were taken out of Bulgaria by B-17’s.142 By 1 October 1944, 2,694 Allied flyers had been rescued from the Balkans. Of this number 1,088 came from Yugoslavia, 46 from Greece, and 11 from Albania in special-duty aircraft. Chetnik territory in Yugoslavia yielded 356 flyers and Partisan territory gave up 732.143 During the period from 1 January to 30 April 1945, 310 Allied flyers were evacuated by specialduty aircraft from Yugoslavia and Albania.144

Such, in general, was the nature of the special operations. With special organizations, equipment, and techniques adapted to their peculiar

* See above, p. 298.

operational problems, units engaged in air support for the underground took on a certain character which set them apart from normal combat units. The security measures which shrouded their activities in secrecy while bomber and fighter missions made daily headlines emphasized that separateness. There was good-humored skepticism, both within the special operations squadrons and without, as to the efficacy of nickeling, the results of which could not readily be assayed. But the delivery of supplies and agents and the evacuation of Allied personnel and US. flyers brought results immediate and tangible enough to bolster morale. Certainly by V-E Day there was cause for satisfaction in the successful execution of the over-all mission, hazardous and important if unsung at the time.