Chapter 13: Battle of Northern Italy

DURING the late summer of 1944 the military situation in Europe was everywhere favorably inclined toward the Allies. In the east, Russian armies were overrunning the Nazi-dominated Balkan states. In France the swift conquest of the territory between Normandy and the Moselle River, coupled with the almost unbelievably rapid advance of Seventh Army up the Rhone Valley, had pushed the enemy back to the very borders of Germany. In Italy, too, after a pause at the Arno River to regroup, the Allied armies had renewed their offensive on 26 August and by 21 September had breached the vaunted Gothic Line.

However, the new offensive in Italy did not proceed with the vigor that had characterized the spring and summer fighting. The rapid pursuit of a fleeing enemy which had featured DIADEM came to an end as extended supply lines, demolitions, and stiffening German resistance slowed the movement of Allied troops. After pushing across the Arno and breaking through the Gothic defenses the Italian campaign bogged down. It became, during the winter of 1944–45, an unpleasant replica of the previous winter’s experience as the open country of central Italy, suitable to a war of movement, gave way to the mountainous country of the northern Apennines. Furthermore, the dramatic rush of the Seventh Army up the Rhone Valley had been made at the expense of the Italian campaign, both in ground and in air resources. France, long since chosen as the decisive combat area in Europe, henceforth would be of such overriding importance that the battle in Italy would have to get along on whatever remained after the requirements in France were met.1

Indeed, movement of the entire Twelfth Air Force into France was repeatedly under discussion from midsummer to the close of 1944. It

had been planned at the end of July that after DRAGOON was well along the Twelfth would follow Seventh Army into southern France, where eventually it would pass to the control of SHAEF,2 and until the last week of August planning went forward on that basis.3 At that time the British expressed grave concern over the proposed move, insisting at a supreme Allied commander’s meeting on 20 August that such a move would not leave adequate air resources, especially in the category of medium bombers, in the Mediterranean. It was also pointed out that there was no authority from the Combined Chiefs of Staff to turn the Twelfth Air Force over to SHAEF. General Eaker, feeling that no decisive action could be expected in the Mediterranean and fearing that the air and ground troops would stagnate if the Italian front became static, advised Arnold on the following day to support in the CCS the plan to move the Twelfth out of Italy and recommended that the Fifth Army be moved to France to reinforce General Devers’ 6th Army Group.4

By the end of August, however, the ground situation in Italy had taken a hopeful turn. Eighth Army’s offensive on the Adriatic flank, which began on 26 August, initially met such success that the prospect of breaching the German defenses during the next phase of the operation, when Fifth Army would launch a drive toward Bologna, looked good.5 Thus, Fifth Army, on the basis of its current commitments alone, would be required in the Mediterranean at least for the next several weeks. Accordingly, late in August, Generals Wilson, Eaker, and Spaatz, meeting in the Mediterranean to discuss the allocation of air forces between southern France and Italy, agreed that so long as U.S. ground forces remained in Italy the bulk of the Twelfth Air Force should also remain but that a few of its air units, already operating in France as XII TAC, would stay with 6th Army Group. Settlement of the ultimate disposal of the Twelfth should be postponed until the outcome of the current offensive was known.6 The decision of course actually belonged to Eisenhower, who was advised on 6 September by General Marshall that he should not hesitate to draw on the Mediterranean for such additional air resources as he felt were needed.7 Eisenhower agreed that for the moment neither ground nor air elements should be moved from Italy, but he recommended that the Twelfth be moved to France as soon as practicable. As an interim measure, the Ninth Air Force should assume operational control of Headquarters XII TAC together with one of its fighter-bomber groups, one tactical

reconnaissance squadron, and corresponding service units, which, when reinforced by units from ETO, would serve as the air arm for 6th Army Group.7 All other units of XII TAC and XII Air Force Service Command currently in France would remain with the Twelfth and would be returned to Italy as soon as the Ninth was in position to assume full responsibility for air support of the armies in southern France. According to Eisenhower’s recommendation, the Ninth would assume operational control of XII TAC on 15 September, the date on which operational control of DRAGOON forces would pass from AFHQ to SHAEF.8 The Combined Chiefs of Staff immediately gave their approval to these proposals.9

As the Combined Chiefs assembled with their respective heads of state at the OCTAGON conference in the second week of September, the British chiefs renewed their advocacy of a continuing offensive through northeastern Italy and into the Balkans. U.S. chiefs, influenced by the favorable situation in Italy, agreed to postpone for the time being any further major withdrawal of their forces, but they continued to oppose pursuing the campaign into northeastern Italy and on into the Balkans, where they felt no decisive action could take place. Instead, they recommended that as much of Fifth Army as could be profitably employed in the attack against Germany be transferred to France as soon as the outcome of the current battle in Italy was certain.10 The Combined Chiefs agreed finally that no further major withdrawals would be made from the Mediterranean until the outcome of the current offensive was known, after which the redeployment of the American Fifth Army and Twelfth Air Force would be reconsidered. In these August and September discussions regarding the redeployment of American forces in Italy, the US. Fifteenth Air Force had come in for very little consideration, it being generally agreed that at least for the moment the Fifteenth could best perform its strategic mission from its bases in the Foggia area.11

Later in the fall of 1944, as the Italian offensive lost its momentum, American leaders again pressed for the move of the Twelfth Air Force. In December they even suggested the advisability of moving the Fifteenth Air Force to France for a concentrated knockout blow against Germany.12 But, because of the difficulty of supporting additional units in France and the lack of suitable airfields there, the continuing close support requirement for Fifth Army in Italy, and the proximity of the Fifteenth’s Foggia bases to German industrial targets, both the Twelfth

and Fifteenth Air Forces were destined to remain in Italy until the final victory. Not until February 1945 did the CCS finally decide to reduce the Italian campaign to a holding effort and to transfer the bulk of Mediterranean resources to France.13 Because of the swift denouement of the war, the move was never completed. Instead, in April 1945, 15th Army Group (formerly Allied Armies in Italy) and MAAF once again combined their resources in a shattering offensive which culminated in the complete defeat of the Germans in Italy.

Breaking the Gothic Line

Air power was a vital factor in bringing about the final defeat. In fact, during the closing months of the war it was by far the most potent Allied weapon in the Mediterranean.* From late August through late October 1944, when it seemed that Kesselring had no alternative but to retire across the Po, the air forces operated under a double-edged strategy: they created a series of blocks in the enemy’s escape routes by knocking out bridges and other elements on his rail and road lines, and then combined their efforts with those of the ground forces in an attempt to drive the enemy back against these blocks where he could be annihilated.

The Po River constituted the first and most dangerous trap for the enemy should he be forced to withdraw from his mountain defenses. The MALLORY MAJOR operation of July† had proved that the permanent crossings over that river could be interdicted, and although their earlier destruction had been designed to separate the enemy from his major supply dumps, their continued destruction could now serve to hamper him in any attempt to withdraw. Consequently, the main striking power of MATAF, as it shifted back to Italy from southern France late in August, was devoted to two primary tasks: close support of the armies and interdiction of the Po.14

During the early stages of the ground-air offensive, from 26 August through 8 September, Desert Air Force handled the close support commitment. When XII TAC had been withdrawn from Italy in July for the approaching invasion of southern France, DAF had been given the responsibility for air action on both Eighth and Fifth Army fronts

* The ground forces, short on manpower and ammunition, were not able to generate an offensive until April 1945, while the Navy’s functions were “largely auxiliary to the other two forces.” (Report by Field-Marshal The Viscount Alexander of Tunis on the Italian Campaign, 12th December 1944–2nd May 1945, draft, p. 6.)

† See above, pp. [.403–5].

then, on 10 August, coincident with the opening of the preassault phase of DRAGOON, it also had assumed responsibility for communications targets in the area bounded by the Genoa–Pavia railway on the west and the Po River on the north (both inclusive) and the east coast.15 During a period of relative quiet on the Italian front (4–25 August) and while MATAF’s other elements were busily engaged with the invasion of southern France, DAF had worked largely to soften the Gothic Line defenses and disrupt enemy lines of communication immediately beyond the front lines.16 When Eighth Army began its assault against the left flank of Kesselring’s forces on 26 August almost the entire effort of DAF was concentrated in direct support of the advance. On the opening day DAF flew approximately 664 sorties, the majority of which were flown against defenses guarding Pesaro, the eastern terminus of the Gothic Line.17 Day and night operations set the pattern for DAF’s day-to-day close support operations as Eighth Army closed in on Pesaro (which was entered on the 31st) and penetrated the Gothic Line. While Kittyhawks, Mustangs, and Spitfires maintained pressure against tanks, troops, and guns, Marauders and Baltimores attacked fortifications between Pesaro and Rimini and marshalling yards at Cesena, Budrio, and Rimini. By night Bostons and Baltimores attacked communications in the Rimini, Ravenna, Forli, Prato, and Bologna areas as well as defenses south of Rimini while night fighters flew defensive and battle-area patrols. On three consecutive nights, 26/27, 27/28, 28/29 August, Wellingtons and Liberators from SAF’s 205 Group pounded enemy troop and equipment concentrations in support of Eighth Army’s attacks on Pesaro.18

Meantime, MATAF’s two bombardment wings and those units of XII TAC which were still based in Corsica had returned to Italian targets. By 21 August, XII TAC had begun to divide its effort between southern France and Italy, and by the last week of the month the campaign in southern France had passed beyond the range of its Corsica-based planes; then the 57th and 86th Fighter Groups, the 47th Bombardment Group, and the FAF 4th Fighter Group (until the latter two were moved to France early in September) turned to Italy altogether.19 As for the mediums, it was obvious by the last week of August that their attacks on bridges in the upper Rhone Valley were hampering Seventh Army’s advance more than they were hindering the German retreat,20 so after 28 August the mediums, too, returned to Italian targets. In addition, by late August the 350th Fighter Group had been

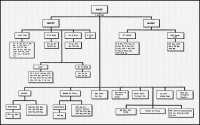

12th AF Organization Chart

re-equipped with P-47 type aircraft (from P-39’s) and had turned from its defensive coastal role to offensive operations in Italy.21

Owing to the necessity for concealing the main point of Fifth Army’s attack, which was to be launched as soon as Kesselring had weakened his center to contain Eighth Army’s threat to his left flank,22 the medium bombers and the Corsica-based fighter-bombers, plus those of the 350th Group, concentrated until 9 September, when Fifth Army jumped off, on communications targets. The mediums struck in force at the Po River crossings with the dual purpose of nullifying the German repair efforts on permanent bridges knocked out during MALLORY MAJOR and of extending the interdiction of the Po westward. After 112 B-25’s cut rail and road bridges at Casale Monferrato, Chivasso, and Torreberetti on the 3rd and 99 B-24’s destroyed the rail bridge at Ponto Logescuro just north of Ferrara (the bridge was too heavily defended for Tactical’s low-flying aircraft) on the 5th, all crossings over the Po from Turin to the Adriatic were blocked. To strengthen interdiction at the Po, mediums struck at numerous other communications targets north and south of the river. In an effort to isolate the rich industrial area of northwest Italy, with its several enemy divisions, the bombers blocked traffic on the Milan–Turin line by destroying all five rail bridges over the Ticino River between Lake Maggiore and the Po and maintained a block on the Milan–Verona line at Peschiera bridge. Fighter-bombers, meanwhile, concentrated on roads and rail lines leading to the Gothic Line; at the same time they supplemented the medium bomber’s interdiction by keeping lateral rail lines north and south of the Po cratered.23

When Fifth Army opened its assault on 9 September, the mediums shifted their attacks on communications from the Po to railroads leading directly into Bologna with the object of isolating the battle area. On the 9th and 10th, B-26’s created cuts on the four lines leading from Bologna to Piacenza, Rimini, Ferrara, and Verona.24 But the bulk of both the fighter-bomber and the medium bomber effort was devoted to blasting a path through the Gothic Line for Fifth Army. Beginning on the 9th and continuing until a spell of bad weather began to restrict operations on the 20th, fighters flew approximately 240 sorties daily against bivouac areas, command posts, troop assembly areas, and supply depots in La Futa and Il Giogo passes, the focal points of Fifth Army’s assault.25 During the same period, medium bombers devoted the major portion of their daily effort to the two army fronts. This included 337

sorties flown on the 9th and 11th in Operation SESAME,26 designed to neutralize selected enemy barracks, supplies, and gun positions which guarded both the Futa and Giogo passes. By the 12th, Fifth Army had overrun the SESAME targets,27 and 113 B-26’s and 33 B-25’s bombed Firenzuola, the supply and communications center for enemy troops in the Giogo area, with devastating effect. Fifth Army’s penetration then removed Firenzuola as a target,28 and for the next two days Marauders and Mitchells shifted their efforts to defenses north of the passes:29 169 mediums bombed in the Futa Pass area on the 13th while on the following day the entire effort of the 42nd Wing, consisting of 204 sorties, was devoted to enemy defenses on Mount Oggiolo and Mount Beni, both north of the Giogo Pass. Weather brought the operations of the mediums to a halt on the 15th; and although on the 16th, 132 B-25’s divided 237 tons of 500-pound and 100-pound phosphorus bombs between Bologna M/T repair and supply depots, Budrio storage depots, and Casalecchio fuel dump – multiplying enemy supply problems on both army fronts – the bulk of medium bomber close support operations had already passed to the Eighth Army front.30

The offensive on the Allied right flank, which had begun so auspiciously on 26 August, soon was slowed down along the last mountain ridges guarding the approach to Rimini by determined enemy resistance and early September rains. By 6 September enemy troops holding the Coriano ridge had succeeded in stabilizing the line; moreover, in the first two weeks of September, Kesselring continued to concentrate troops opposite Eighth Army until some ten divisions had been grouped in the Rimini area. German defenders held firm until the Eighth launched an all-out assault on the night of 12/13 September, which, by overrunning Gemmano, San Savino, and Coriano – all key points on the ridge – forced the enemy to fall back toward Rimini. Although Eighth Army was now overlooking that city, a week of steady fighting, accompanied by sustained efforts by DAF and TAF’s two medium bombardment wings, remained before the city was taken. At its strongest in mid-September, the formidable concentration blocking the advance of Eighth Army gradually weakened as Fifth Army’s threat to Bologna became increasingly serious. Nevertheless, by temporarily stabilizing the line south of Rimini the enemy won an important strategic victory by denying Eighth Army entry into the Po Valley until fall rains prevented full exploitation of the breakthrough.31

During the period of hard fighting for Rimini, DAF’s operations

were raised to new levels for sustained effort. They reached their peak on the 13th when aircraft flew more than 900 sorties and dropped in excess of 500 tons of bombs. The more than 800 sorties flown on the 14th paid particular attention to enemy movements which were increasingly noticeable. After a day of reduced effort on the 15th, DAF’s operations rose to more than 700 sorties daily for the next three days, the majority of them devoted to Army demands. For example, on 17 September, Eighth Army troops had pushed forward to a heavily defended ridge, known as the Fortunate Feature, which had to be stormed before Rimini could be invested; accordingly, from first light to 0745 hours on the 18th, DAF Kittyhawks and Spitbombers kept up ceaseless bombing and strafing attacks on guns, mortars, and strongpoints along the ridge in order to soften the opposition to the ground assault which followed. Close support missions, characterized by effective use of Rover Joe, were maintained throughout the day.32

On the 14th medium bombers threw their weight into the battle for Rimini. The rapid overrunning of Pesaro in the first week of the offensive had obviated the necessity for a medium bomber operation, planned since 25 August under the code name CRUMPET, against defenses and troop concentrations there.33 After this operation had been called off, stiffening enemy resistance before Rimini presented an opportunity for adapting the plan to a new locality. In fact, medium bomber reinforcement of the DAF effort against the Rimini defenses had been requested and planned under the code name CRUMPET II since 5 September,34 but owing to a period of unfavorable flying weather between 5 and 8 September and the heavy effort allocated to Fifth Army between 9 and 13 September, the operation was postponed until the 14th. Plans called for both wings of mediums to attack enemy troops, defenses, and gun positions on the hill feature three miles west of Rimini,35 but as it was necessary for the 42nd Wing to continue the pressure on the Futa Pass area, only the 57th Wing carried out CRUMPET II. In three missions its planes flew 122 sorties and dropped 10,895 x 20-pound frag bombs and 215 demolition bombs, totaling 163 tons, covering approximately 60 per cent of the target area. On the same day DAF Marauders and Baltimores flew eighty-four sorties against gun areas and defended positions outside Rimini.36

On the 15th weather grounded all mediums and limited DAF to some 500 sorties, but on the 16th and continuing for three days, DAF and the medium bombers laid on a heavy aerial assault. With

CRUMPET II targets already occupied by the 16th, this medium bomber effort was applied to the area immediately north of the battle area, particularly along the banks of the Allarecchio River. Marauders and Baltimores of DAF added their weight to the attacks on each day. Although bad weather on the 19th brought to a halt operations by the two bombardment wings, DAF Spitfires and light and medium bombers continued to attack in the Rimini area. On the 20th the weather completely deteriorated, bringing air operations to a virtual standstill for the next several days.37 On the 21st the stubborn defense of Rimini was broken as elements of Eighth Army occupied the town. Gen. Sir Oliver Leese, commanding Eighth Army, expressed appreciation for the part played by the air forces in the assault, particularly their bombing of gun positions on the 16th and 17th, to which he attributed the negligible shelling received by Eighth Army in its attack on the 18th.38

The capture of Rimini coincided with Fifth Army’s successful breaching of the Gothic Line at Giogo and Futa passes. As Fifth Army moved through the breach to the Santerno Valley the stage was set for the next phase of the second winter campaign: the assault on Bologna by Fifth Army and exploitation of the breakthrough into the Po Valley north of Rimini by Eighth Army.

At this juncture it was felt in Italy, as it was at SHAEF, that the end of the war was near. Early in September, General Wilson had expressed the hope that the combined offensive by Fifth and Eighth Armies would result in reaching the line Padua–Verona–Brescia within a few weeks, thus securing the destruction of Kesselring’s armies and preventing their withdrawal through the Alpine passes.39 This seemed a distinct possibility as Fifth Army continued to push toward Bologna and Eighth Army fanned out toward Ferrara, the immediate objectives of the current offensive. AFHQ Weekly Intelligence Summary optimistically reported on 25 September:40 “There can now no longer be any question of the enemy’s reestablishing himself on the line of the Apennines ... tenacious as he is, Kesselring must now be exploring the prospects of conducting an orderly withdrawal.” But Kesselring proved the optimists wrong. Taking every advantage of terrain and favored beyond measure by torrential early fall rains, he stabilized his line and forced the Italian battle into an extra round of seven months.

Until near the end of October, however, there was still hope that a breakthrough might be achieved. Consequently, interdiction of the Po, the first barrier to enemy movement, remained as MATAF’s primary

communications objective,41 and after the period of intensive effort on the Army fronts, 9–18 September, medium bombers returned to the Po River crossings and to communications targets in northwestern Italy. The few attacks leveled at Po River bridges during the last ten days of September were designed to inflict fresh damage on crossings already cut and to counteract the German repair effort. A notable operation was that of B-26’s on the 26th when they completely destroyed a new bridge at Ostiglia after it had been in operation for not more than three days. At month’s end, all except one or two road and rail bridges between Turin and the Adriatic were cut.42 The success of these September attacks, coupled with the apparent German inability to keep pace with the destruction at the Po, permitted a considerable decline in medium bomber effort at this line during October. Five missions of 113 sorties were sufficient to maintain the interdiction of the permanent crossings until late in the month when the rail bridge at Casale Monferrato was restored to use. The mediums also kept the lateral lines north of the Po blocked at the line of the Ticino River and other points until the latter half of October when weather brought their operations almost to a full stop, allowing the Germans to repair some of the damage.43

In the meantime, both Eighth and Fifth Armies had continued to inch forward, the former supported – as always – by Desert Air Force and the latter by XII Fighter Command, formerly the AAF element of Mediterranean Allied Coastal Air Force. Owing to the recent and extensive ground advances in Italy and southern France and the disappearance of German air and sea threats in the Mediterranean, MACAF, charged since February 1943 principally with a defensive role, had lost much of its one-time importance.44 MAAF, therefore, to absorb the loss of XII TAC and to provide a working partner for Fifth Army, withdrew XII Fighter Command from Coastal and reconstituted it on 20 September as a tactical air command under Brig. Gen. Benjamin W. Chidlaw. By mid-September. Fighter Command’s 350th Group and three night fighter squadrons had been strengthened by the assignment of XII TAC units remaining in Corsica: 57th and 86th Fighter Groups and 47th Bombardment Group (L), though the latter’s air echelon was in France.45

Fighter Command was later augmented by units of XII TAC no longer required in France, although the return of these units was delayed until after the CCS on 16 September approved the split of the

Twelfth between Italy and France. Representatives from ETO and MTO then met in a series of conferences to work out the details of the division of units already in France.46 The choice of combat units to remain with XII TAC was readily made, but the question of service units was complicated by the fast-moving campaign in France which had multiplied the problems of service, as well as of airfield construction, and had led naturally to higher demands on the Mediterranean for service and engineer units than had originally been anticipated. Too, the impending return to Italy of Twelfth Air Force units from France and Corsica limited the number of service units which leaders in the Mediterranean felt could be spared. Consequently, it was not until 27–28 September, at a conference at Caserta, that final agreements were reached regarding the division of air units between France and Italy.47 By the terms of this agreement, Headquarters XII TAC, together with 64th Fighter Wing, the 324th Fighter Group, the 111th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron, and fourteen supporting units were to remain in France; all other Twelfth Air Force elements were to return to Italy, the combat units by the 10th of October and the service units by the 15th. Consequently, early in October units began returning from France, and XII Fighter Command’s operational strength was swelled by the addition of the 27th and 79th Fighter Groups. On 19 October the command, now composed of twenty-five squadrons, was officially redesignated XXII TAC* and, fully established in Italy, assumed the character it was to keep for the next several months.48 Meanwhile, early in September, Fighter Command had begun to change from its old defensive function to its new offensive role, although not until it was reconstituted a tactical air command on 20 September did it officially assume responsibility for close-support operations on the Fifth Army front. DAF retained its responsibility for this function on the Eighth Army front.49 This arrangement provided more intensive air efforts on both fronts. Yet the two air commands were mutually supporting when the situation required and when resources permitted, and in this regard, because there was a shortage of night intruder aircraft (always a serious problem in the Mediterranean)

* XXII TAC had lost the 79th Group with its three squadrons to Desert Air Force and the 417th Night Fighter Squadron to Headquarters Twelfth Air Force, but compensating for these losses, and giving the command an international flavor, RAF 225 and 208 Tactical Reconnaissance Squadrons, 324 Wing with its four squadrons of Spitfires, and the Brazilian 1st Fighter Squadron had been placed under the operational control of the command early in October. Thereafter, the only significant change that occurred in the new TAC until February 1945 was the replacement of 324 Wing with SAAF 8 Wing in November, the RAF element reverting to DAF.

pending the return of the 47th Bombardment Group from France, DAF’s 232 Wing operated over both armies. Although close support was the primary mission of Fighter Command and DAF, both were ordered to employ “the maximum force possible against communication targets compatible with the effort required for close support.”50 The communications for which the fighter-bombers had primary responsibility lay between the Po and the battle area from the Adriatic coast to Piacenza. The dividing line between Fighter Command and DAF was generally the inter-army boundary. Second priority was assigned the area north of the Po as far as Verona; here the boundary ran south from Verona along the Adige River to Legnano, thence due south to the Po River.51 Actually, the dividing lines were not strictly enforced and by mutual consent each of the commands often operated in the other’s area of responsibility.

On 20 September only the six squadrons of the 57th and 350th Fighter Groups and one night fighter squadron were in Italy. The remainder of Fighter Command’s new strength was either in process of moving from Corsica or was in France awaiting replacements from the Ninth Air Force.52 Nevertheless, the build-up of the command’s combat strength,* together with a break in the weather during the last six days of the month, allowed its planes to fly 457 missions, totaling 1,904 sorties, in the first ten days of its operation as a tactical air command.53 These missions were devoted largely to support of Fifth Army as it pushed from the Futa Pass northward toward Bologna and northeastward toward Imola. In addition to attacks on troop concentrations, strongpoints, and storage depots, with particular emphasis on enemy positions along Highway 65 south of Bologna, fighter-bombers hit enemy communications in the Po Valley from the bomb safety line as far north as Lake Maggiore; especially hard hit were enemy rail and road communications from Bologna northward through Reggio and Piacenza. Furthermore, as the Germans made increased use of ferries and pontoon bridges over the Po at night to counteract the medium bomber bridge-busting program, fighter-bombers attacked reserve pontoons stored along the banks and potential bridge sites. But the German’s clever use of camouflage made it difficult to locate the latter targets and the attacks were not particularly effective.54

* Consisting of the 350th, 57th, and 86th Fighter Groups, 414th and 416th Night Fighter Squadrons, and the 47th Bombardment Group, reinforced by DAF’s 7 SAAF Wing by month’s end. The latter unit remained under Fighter Command’s operational control only until 4 October.

DAF, likewise, was brought to a virtual standstill on five out of the last ten days of September by the unfavorable weather. Nevertheless, on the five operational days, it put in some telling blows for Eighth Army, which was driving along the narrow corridor between the mountains and the Adriatic. The fall of Rimini on 21 September widened the scope of DAF’s operations, for after that date specific strongpoints, guns, and concentrations became fewer and the advancing ground troops had less need for saturation bombing and strafing of specified points. DAF, therefore, raised its sights to communications targets immediately beyond the front lines in operations intended to hinder enemy movements, regrouping, and bringing up of supplies. Its principal bridge-busting activities took place along the Savio River. In addition, fighter-bombers cut railway tracks with particular emphasis on those in the triangle Ferrara–Bologna–Ravenna, while light and medium bombers attacked marshalling yards on the Bologna–Faenza–Cesena route.55

During October the operations of all of MATAF’s elements were severely restricted by the weather, which steadily worsened. Despite the restricting weather, aircraft from both DAF and XII Fighter Command (XXII TAC after 19 October) were airborne on every day of the month except one, although on seven days operations were held to less than 100 sorties a day. For the month DAF flew something over 7,000 sorties and XXII TAC about 5,000.56 Although the bulk of these operations was devoted to the Eighth and Fifth Army fronts, some effort was applied to communications. In fact, DAF’s attacks on communications continued to be closely identified with Eighth Army’s advance as bridges across the Savio River, the enemy’s next line of defense, absorbed a portion of the air effort on every operational day until 15 October when all of the bridges across that river, save one spared at Army request, were down; primary rail-cutting operations continued to take place south of the Po River along lines leading into the battle area, particularly those from Ferrara.57 XXII TAC concentrated its communications attacks, which became more numerous after the middle of the month, in the Cremona–Mantova area and on rails and roads radiating north, east, and west from Bologna, with particular emphasis on the Bologna–Faenza rail line; roads were cratered most extensively between Ferrara and Parma. Farther to the west, its fighter-bombers cut rail lines in the Milan and Genoa areas. Late in the month, as fighting died down on the Fifth Army front, XXII TAC penetrated

the lower part of the Venetian plain where it hit rolling stock in the marshalling yards of Verona and Padua and cratered tracks on the lateral Verona–Brescia line. A considerable effort continued to he applied to the Piacenza–Bologna line south of the Po.58

The primary commitment of both commands, however, was assistance to the land battle. DAF devoted the largest share of its effort for the month to Eighth Army’s advance, paying particular attention to troop and supply concentrations near the battle area; favorite targets were Cesena, until it was captured, and then Fork the Army’s next objective. In addition, on the first four days of the month, its Kittyhawks and Mustangs and one Spitbomber wing flew most of their sorties over XXTI TAC’s area on behalf of Fifth Army’s thrust toward Bologna.59

During the first half of October, XXII TAC had been busily engaged on the Fifth Army front. General Chidlaw had brought from XII TAC to his new command a thorough knowledge of the working arrangement that had existed between General Clark, Fifth Army commander, and General Saville of XII TAC, and he organized the new TAC to conform in principle to the old pattern. The same mutual respect that had existed between Clark and Saville soon existed between Clark and Chidlaw; air-ground relations were excellent, and close support operations on the Fifth Army front improved.60 Nevertheless, and in spite of the fact that almost the entire effort of XXII TAC during the first eleven days of October was given over to support of Fifth Army’s offensive, the adamant German defense held. And by holding, the Germans threatened to wreck the Allied strategy, which hinged on Fifth Army’s breaking through the center of Kesselring’s line and fanning out north of Bologna to form the left prong of the pincers which would catch the German armies in Italy. Eighth Army was already along the line of the Savio River and was slowly pushing toward Ravenna and Faenza, but Fifth Army, stopped some twelve miles south of Bologna by increasing German strength as Kesselring swung divisions away from the Adriatic flank to stem the threat to his center, was far from the breakthrough which was necessary to complete the strategic plan. Consequently, in mid-October, in far from favorable flying weather, MATAF and MASAF combined their resources in a new assault, given the name PANCAKE, which had as its object the destruction of enemy supplies and equipment in the Bologna area, the annihilation of enemy forces concentrated on the approaches to the

city, and the limited isolation of the battle area. The 42nd Wing’s B-26’s, taking advantage of a break in the weather on the 11th, divided 1,000 pound and 500-pound demolition bombs among three road bridges and an ammunition factory. The peak of the operations came on the 12th, when 177 B-25’s (out of 213 dispatched) dropped 1,011 x 500-pound bombs on four targets, including two supply concentrations, a barracks area, and a fuel dump, while 698 heavy bombers (out of 826) divided 1,271 tons of 20-pound fragmentation and 100-pound, 250-pound, and 500-pound bombs among ten assigned targets; unfortunately, only 16 out of 142 B-26’s airborne were effective, most of the remaining 126 being unable to locate specified targets because of cloud cover.61 During the three-day period XXII TAC flew some 880 sorties, concentrating on strongpoints, guns, troop concentrations, and occupied buildings in the battle area. Fighter-bombers also flew area patrols for the medium bombers but no enemy air opposition was encountered.62 A Fifth Army G-2 summary described the air support provided on 12 October as eminently successful.63 Assigned targets had been attacked in a timely, accurate, and most effective manner, thus aiding materially the advance of Fifth Army to take important positions. In addition, the air assault was credited with raising the morale of Allied soldiers and, conversely, with a demoralizing effect on the German defenders.

Unfortunately, Fifth Army, in its weakened condition and in the face of the bad weather, was not able to exploit fully the advantage gained by the air assault. U.S. II Corps made some progress; by 14 October it had occupied the southern half of the town of Livergnano on Highway 65. Nevertheless, the combined assault failed to take Bologna, although Fifth Army continued until the 26th a desperate attempt to break through the stubborn German defenses. From 14 through 20 October, when weather brought air operations to a virtual standstill, XXII TAC’s aircraft flew more than 300 sorties a day in support of the assault.64 By 26 October the weariness of the troops – they had been fighting steadily for six weeks – the shortage of replacements in the theater, the strength of the enemy, the status of available ammunition stocks, and the weather had combined to stop Fifth Army cold and there was no alternative but for it to pass temporarily to the defensive and make preparations for resuming its offensive in December.65

The weather was so bad during the last few days of the drive that it not only brought air operations virtually to a standstill but even blotted out artillery targets. Medium bombers, in fact, were grounded on all

but three days in the period 14 October-4 November, while XXIf TAC’s effort from 21 October until early in the next month was reduced to less than 100 sorties a day, save on the 25th.66

With the collapse of the offensive south of Bologna little hope remained of securing in the immediate future “the destruction of Kesselring’s army by preventing its withdrawal through the Alpine passes.” Even if the present line should be broken, the weather, which was swelling the rivers of the Venetian plain and making the mountainous country of northern Italy well-nigh impregnable,67 militated against a successful campaign during the winter.* This, however, left unchanged the mission of the Allied forces in the Mediterranean, which was to contain or destroy enemy troops.68

Revision of the Interdiction Campaign

Throughout November, while Fifth Army was making preparations to resume its offensive in December, Eighth Army continued to maintain pressure against the Germans and to make some progress. DAF, assisted on occasion by MATAF’s two medium bombardment wings, supported these operations. Forli fell on the 9th, after DAF had devoted approximately 800 sorties to defenses in the area on the 7th and 8th, and 92 B-26’s had bombed buildings, Nebelwerfer positions, and troop concentrations northeast of the town on the 7th.69 Eighth Army’s next objective along Highway 9 was Faenza, but before it could be taken it was necessary to establish a bridgehead over the Cosina River and then to exploit to the Lamone River. DAF, in addition to supporting the drive up to the Cosina, attacked roads and rails leading to the front lines. As a supplement to DAF’s effort to isolate the battle area,

* In view of the obvious difficulties of conducting a winter campaign in northern Italy, General Wilson, late in October, proposed that plans be made to take advantage of the favorable situation developing in the Balkans. It seemed that the Russian advances on the southeastern front would force the Germans to evacuate Yugoslavia, thus opening the Dalmatian ports to the Allies and giving them relatively easy access to Trieste and Fiume. He suggested therefore that the Italian campaign be halted as soon as his armies reached the Ravenna–Bologna–Spezia line; six divisions would then be withdrawn from the Italian battle, and in February 1945 be sent across the Adriatic and up the Dalmatian coast toward Fiuine and Trieste as the right prong of a pincer movement (the left prong would be the forces remaining in Italy) which would trap Kesselring in Italy. The Soviet’s Balkan offensive, however, swung from west to northwest late in October and the consequent German strength massed in northern Yugoslavia was far more formidable than Wilson had anticipated; furthermore, the decision that SHAEF would give the Germans no winter respite in France barred any relaxation of pressure in Italy. Consequently, late in November, Wilson cabled the CCS that his October proposal was no longer feasible.

the 57th Wing’s 340th Group flew 114 effective B-25 sorties on 16, 17, and 19 November against bridges across the Lamone River at Faenza.70 Beginning on 21 November and continuing through the 24th, B-25’s turned their attention to three areas farther to the east in an effort to neutralize guns which could be brought to bear on 5 Corps troops crossing the Cosina River (Operation HARRY);71 on three days, 21, 22, and 24 November (weather rendered an attempt on the 23rd completely abortive), B-25’s flew 262 effective sorties in the three target areas. During the four-day period, DAF devoted some 1,200 sorties to battle-area targets.72

Attempts to cross the Cosina on the 21st and 22nd were repulsed, but on the night of the 22nd, following the two days of devastating fragmentation bombing by the mediums and bombing and strafing attacks by DAF’s aircraft, Eighth Army established a bridgehead across the river and stopped the expected German counterattack. Following this all-out effort, the weather closed in, bringing air operations on Eighth Army front virtually to a stop until the end of November. Even so, by the end of the month the British army had reached the line of the Lamone River.73

In the meantime, the failure of Fifth Army to take Bologna at the end of October, coupled with a variety of other factors, had resulted in a revision of the air forces’ strategy of interdiction. As already noted, throughout September and October, in anticipation of a German withdrawal, interdiction efforts had been concentrated on the Po River crossings, where the destruction would impede the retreat of the greatest number of German divisions.74 But that was not enough, for the optimistic view that Kesselring would have no alternative but to retire across the Po and attempt to re-establish a line at the Adige River or at the foothills of the Alps dictated that interdiction of the Po be reinforced by blocking the enemy’s escape route farther to the north. This could be accomplished, first, by having MASAF interdict the Brenner, Tarvisio, Piedicolle, and Postumia rail routes (the only frontier lines available to the Germans, save those through Switzerland, after the rapid advance in southern France had closed the Franco-Italian routes) which passed through the mountainous country north of the Venetian plain and connected Italy with Austria and Yugoslavia, and, second, by having MATAF destroy the bridges which carried the complex rail network of the Venetian plain over the Brenta, Piave, Livenza, and Tagliamento rivers.75 All of these lines lay north of the Po.

Direct hit on highway bridge in Italy

Cathedral and bridge: Rouen

B-25 hits bridge at Brixlegg

B-25 hits bridge at Brixlegg

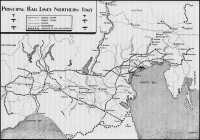

Principal rail lines Northern Italy

Orders to add these more northerly lines of communication to other commitments had gone out to Strategic and Tactical late in August,76 and for the next two months MAAF’s bombers paid some attention to the lines. Between 26 August and 4 September MASAF created one or more blocks on each of the four main frontier routes, and between 29 August and 1 September, MATAF’s medium bombers inflicted varying degrees of damage on the principal rail bridges over both the Piave and Brenta rivers. As a result, all through traffic in northeastern Italy was blocked at the Piave for perhaps as long as two weeks.77 Owing to the commitments of the heavies in the Balkans and of the mediums at the Po, no further pressure was applied to the northern routes for the next three weeks. But in view of the favorable ground situation after 21 September, MATAF, in addition to maintaining interdiction of the Po, sent its medium bombers back to the Brenta and Piave crossings on the 22nd, 23rd, 26th, and 30th (the only operational days for medium bombers in the period 20–30 September).78 In addition, in view of the enemy’s strenuous repair efforts, MASAF, on the 23rd, dispatched 350 B-24’s to the four main lines. Weather interfered with the attacks and no effective results were achieved at the primary targets; however, the heavies materially aided Tactical’s campaign against the Piave River crossings by the destruction of the Ponte di Piave and S. Donà di Piave, which were hit as alternate targets.79

By the end of September, as a result of the medium bombers’ successful attacks at the Piave and Brenta, there was a growing feeling that MATAF could take over the job of interrupting the northeastern routes, leaving Strategic free to concentrate on the more difficult Brenner route. Consequently, on 1 October, MASAF, on MATAF’s recommendation, was relieved of all responsibility for Italian communications except for interdiction of the Brenner.80 Although attacks by Strategic on the other routes would be welcomed, Tactical was given continuing responsibility for interdicting traffic from the northeast at the Piave and Brenta.

Despite bad weather in October, B-26’s during the month flew twelve missions of 187 sorties against crossings over the two rivers. These blows, coupled with heavy bomber attacks on targets on the Venetian plain (hit as alternates) on the 10th and 23rd, kept all three of the northeastern routes blocked at the Piave, and sometimes at other points as well, for sixteen days in October.81

MATAF felt that difficulties of terrain and heavy flak defenses at

the vital bridge targets precluded medium bomber attacks on the northern section of the Brenner. Late in September, however, MATAF had suggested that its mediums could supplement Strategic’s primary cuts by postholing the southernmost sections of the rail line above Verona; these same sections could be kept cratered by limited fighter-bomber action. The suggestion was put into effect, but neither Strategic nor Tactical could cope with the bad weather of October which, by obscuring targets or tying down the bombers at their bases, so handicapped operations against the Brenner that it was interdicted only spasmodically. On the 4th, MASAF damaged the Ora bridge and created numerous cuts in the fifty-six miles of railroad between Trento and Mezzaselya. On 3 October, MATAF’s mediums made their first efforts against the Brenner. Between that date and the 20th, B-26’s flew five missions of eighty effective sorties to the Ossenigo and Dulce rail fills on the southern, bridgeless extremity of the line; each mission cratered tracks and effected temporary blocks.82

Weather rendered abortive attempts by SAF to bomb the Brenner on the 10th and 20th. But later in the month, in view of the enemy’s repair effort and the report that two Italian Republican divisions were to be sent over the Brenner from Germany between 20 and 25 October as reinforcements for the Italian front, Strategic again attempted to block the line. Unfortunately weather again proved a hindrance and only 54 of the 111 B-24’s completed the mission, inflicting only temporary damage at various points along the line.83

These September and October interdiction operations in northern Italy had been on a small scale and had been laid on primarily to supplement the heavier effort at the Po. But by the end of October it had become obvious that the anticipated retreat across the Po Valley would not soon materialize. This new situation, with a stalemate developing on the ground, demanded that the air forces revert to their previous policy of interdicting to deny supplies to a stubborn foe. This could now be best accomplished by shifting the main interdiction effort to the Venetian plain and the frontier routes.84

By late October, although all of the bridges over the Po were down, the Germans by ingenious use of pontoon bridges and ferries at night, and even pipelines, were continuing to meet their immediate supply requirements from depots north of the Po. Indeed, it was all too apparent that Kesselring had won the battle of logistics at the Po. On the other hand, operations against the Brenner and in northeastern Italy

had been effective enough to cause considerable delays in the shipment of materials from Germany and to create many additional fighter-bomber targets among the accumulations of rolling stock. But even here interdiction was being neutralized; the rate of repair on the Brenner was quickening, and after almost two months of interdiction, lines across the Piave were being reopened by restoring bridges and by constructing by-passes.85 furthermore, in September, the Germans (perhaps in anticipation of being forced out of Italy) had greatly accelerated their looting of the Po Valley, and trains moving toward the frontiers over the Brenner and Tarvisio routes became more numerous.86 Obviously then, if the removal of Italian industries were to be stopped, a stricter interdiction of the frontier routes would have to be imposed; likewise, if the enemy forces at the front were to be denied supplies, traffic would have to be halted before it reached the Po. But in the face of a growing German skill in effecting repairs this could be accomplished only by a greater concentration of effort against the four principal rail routes connecting Italy with the Reich.

These considerations led to the announcement of a new bombing policy on 3 November. The Po River was reduced from first to third priority in the interdiction scheme. In its stead, interdiction of the Brenner was to be maintained on a first-priority basis, followed by interruption of traffic over the northeastern lines at the Piave, Brenta, and Tagliamento rivers, in that order of priority. Although the Po Valley was to remain the principal commitment of fighter-bombers, they were given for the first time a commitment farther north: “When weather prevents medium bomber operations in Italy and it is considered that the Brenner or northeastern rail routes are in danger of being repaired, fighter-bombers will be directed ... , against vulnerable targets on these routes until such time as renewed medium bomber effort is possible.”87

The new bombing program was inaugurated on 6 November by an all-out attack on the electrical system of the Brenner line.88 The events of October had provided sufficient evidence that long spells of nonoperational weather precluded maintaining the bombing schedule necessary to keep the Brenner blocked. Air tacticians, searching for some means of reducing the capacity of the Brenner to an extent that would deny to the enemy full use of the line even in extended periods of bad weather, came up with the idea of forcing him to change from electrical to steam power. With electrical equipment the Brenner route

had a capacity of twenty-eight to thirty trains a day in each direction, representing up to 24,000 tons that could be transported daily when the line was in full working order. By forcing the Germans to switch to steam locomotion, which is less efficient on the long and steep grades of mountainous country, it was estimated that the capacity of the Brenner would be reduced to from eight to ten trains daily, thereby lowering the daily tonnage transported over the line by some 6,750 tons. Since this figure represented approximately twice the estimated daily tonnage required by the German forces in Italy, it was assumed that, with steam locomotion, it would be necessary for the enemy to keep the Brenner fully open at least 50 per cent of the time in order to maintain his supply levels.89 The targets for air attack would be transformer stations, of which there were fourteen between Verona and the Brenner Pass spaced some twenty miles apart where gradients were less severe and ten miles apart in the steeper sections of the line. Such was the arrangement of the system that not less than three consecutive stations would have to be destroyed in order to make the use of electric power impossible on any one section of the line. MATAF, therefore, ordered its medium and fighter-bombers to execute coordinated attacks on the four transformer stations between Verona and Trento. MASAF was requested to support Operation BINGO, as the plan had been coded, by attacking the stations at Salorno, Ora, and Rolzano, farther to the north.90

On 4 and 5 November weather conditions were favorable for extensive bomber operations along the lower Brenner line, and mediums cut the section between Trento and Verona at twenty-five to thirty points. Hundreds of units of rolling stock were trapped between these cuts and all rail traffic was completely disorganized on the southern section of the line. The time seemed appropriate for executing BINGO. Consequently, on the morning of 6 November, 102 B-25’s, 60 P-47’s, and 22 Kittyhawks struck the four MATAF targets. Thunderbolts and Kittyhawks of DAF put the station at Verona out of commission, while B-25’s, drawn from all three groups of the 57th Wing, and P-47’s of the 57th Fighter Group rendered completely useless the stations at Domegliara, Ala, and Trento. Closely coordinated with these operations were attacks by 103 B-26’s on vulnerable rail targets between Verona and Trento, at Ossenigo, Sant’ Ambrogio, Dulce, Morco, and Ala; the Marauders created seven blocks on the line.91 The enemy apparently despaired of the task of repairing the shattered transformers

and never regained the use of electric locomotion on the line from Verona to Trento.92 On the same day, MASAF dispatched twenty-three B-24’s, escorted by forty-six P-38’s, to the three targets on the northern end of the line, but no permanent damage was inflicted on the transformer stations and the enemy was able to continue to use electric power on that section of the track. On 7 and 12 November, SAF made amends for this failure by carrying out a series of successful attacks on bridges along the Brenner. In view of the enemy’s proved ability to repair minor damage very quickly, it was necessary to knock out one or more spans to give any permanence to the interdiction of bridges; therefore, bridges which had long spans were chosen as the most vulnerable targets, and they received the heaviest weight of the attacks. The bombers knocked out such bridges over the Adige at Ora and Mezzocorona; they also hit the,crossing over the Isarco River at Albes, but the temporary damage was speedily repaired. On the 11th, although clouds obscured the Brenner, 35 Liberators out of 207 dispatched supplemented MATAF’s campaign against the northeastern routes by rendering impassable bridges over the Tagliamento River.93 MATAF’s October operations against the Brenner’s lower reaches were considered as supplementary to MASAF’s attacks on the more crucial part of the line north of Trento. But Strategic’s operations even against this vital part of the Italian communications system were destined soon to end. Since September, when the Allied armies in France drew close to the German borders, there had been proposals for concentrating strategic bombardment against the railway system of Germany itself,94 and by November that system had been given a priority second only to oil* in the list of strategic targets.95 Accordingly, on 11 November, General Eaker relieved MASAF of all responsibility for attacking communications targets in Italy, including the Italian side of the Brenner, although ir was to maintain dislocation of traffic at Innsbruck in Austria, the important control center for rail traffic into the Brenner from the north.96 A few days later, when Strategic’s new commitment crystallized in a directive from MAAF, MASAF’s role in the isolation of Italy from the Reich was further reduced, for now the railway lines between southeast Germany and the Danubian plain were to be given precedence over those between southern Germany and Austria and Italy.97 Indeed, after 16 November, MATAF was fully

* See below, p. 653.

responsible for the selection of targets and air operations everywhere in Italy; and no target on the peninsula was to be attacked except upon request By or approval of MATAF. Thus, although MASAF and MACAF carried out occasional attacks in northern Italy at MATAF’s request (priniarily on a weather-alternate basis), after mid-November air operations in Italy rested with MATAF.98

MATAF did not at once expand the scope of its operations to cover the targets heretofore considered Strategic’s responsibility in northeastern Italy, but bridges on the lower and middle Rrenner became increasingly favorite targets. Medium bombers pushed past Trento to attack rail bridges over the Adige at San Michele and Ora on the 11th and the long viaduct at Lavis over the mouth of the Avisio River on the 17th, and attacked small bridges and fills south of Trento. From 1 through 19 November some forty-four medium bomber missions were flown against the Brenner, including those flown during BINGO. As a result of these operations, plus the damage inflicted by SAF and by an increasing effort By fighter-bombers against the lower Brenner after the 19th, the route remained closed to through traffic By multiple curs (which reached as many as thirty-five at one time) until the last day or two of the month. From 1 through 25 December, however, the weather limited medium bombers to twelve missions against the Brenner. Bridges at Ala, Rovereto, Calliano, and Sari Michele were targets on 2 and 10 December, but ground haze, smoke screens, and flak prevented the incdiums from inflicting structural damage to any of the rail crossings, although in each case temporary cuts were made in the tracks.99 Though this effort, combined with additional cuts in tracks created by fighter-bombers, gave German repair crews no respite, interdiction of the Brenner was intermittent and short-lived during the first twenty-five days of December.100

In addition to attacks on the main Krenner line in November, mediums also struck hard at the loop line running southeast from Trento to Vicenza, and by the 13th had cut the line at Calceranica, Castelnuovo, and Engeo. This route remained locked for the next six weeks, for although the mediums were able to bomb the line only once during December, fighter-bombers kept a constant check on repair efforts and it was not until 3 January 1945 that the line was reported open.101

The interdiction of the rail routes across the Venetian plain was maintained through most of November, and by the middle of the month October’s interdiction of the northeastern routes at the Piava.

and Brenta rivers had been reinforced by additional cuts at the Tagliamento and Livenza rivers, By month’s end, the Nervesa bridge was the only one open between Udine and Padua across the Brenta, Piave, Livenza, and Tagliamento rivers. Swift repair and nonoperational weather permitted increased activity on the northeastern routes during the last week in November, but the number of cuts on the various lines and the consequent necessity of repeated transshipments over an eighty-mile zone continued for a time to interpose a barrier against transportation of heavy supplies into Italy.102 But other air commitments late in November – the most important of which was a substantial medium bomber effort at Faenza for Eighth Army from 21 through 24 November, and nonoperational weather in December, which limited the mediums to five missions against the northeastern routes, allowed the Germans to open at least one bridge or by-pass over each river barrier, so that although the enemy was frequently denied the most direct connections and was forced to resort to roundabout routes from early in December until the 25th, through traffic moved southward at least as far as the Brenta River.103

There was one other factor which accounted for the weakening of the interdiction campaign after 19 November: the loss to ETO of the 42nd Bombardment Wing headquarters with two of its B-26 groups. After the OCTAGON conference, at which the CCS had agreed that there would be no further withdrawals from Italy until the outcome of the current offensive was known, American air leaders, fearing that the 6th Army Group in southern France did not have adequate air resources, had continued to press for the move of the entire Twelfth Air Force.104 But when General Spaatz brought up the matter in mid-October at a conference at Caserta with Generals Wilson, Eaker, Cannon, and others, it was agreed that the conditions which had prevented an earlier move still prevailed: Twelfth Air Force could not be supported logistically in France and the requirement of air support for Fifth Army still remained. Since the Twelfth could not be spared, the alternative of forming a provisional tactical air force for 6th Army Group was proposed. Requirements from the Mediterranean included Headquarters 63rd Fighter Wing (at cadre strength), which was to serve as the headquarters for the new air force, and the 42nd Bombardment Wing, plus service units to support the latter. Plans were already under way to convert one B-26 group to B-25’s, and General Spaatz agreed to accept the two remaining B-26 groups.105 Consequently, on 5 November the 319th

MAAF Organization 1 Nov. 1944

Bombardment Group was transferred from the 42nd to the 57th Wing, and on the 15th, Headquarters 42nd Bombardment Wing with the 17th and 320th Groups, the entire 310th Air Service Group, and Headquarters 63rd Fighter Wing were transferred to ETO.106

MATAF’s waning medium bomber strength suffered another loss the following month when the War Department decided to withdraw one B-25 group and a service group for redeployment against the Japanese.107 Although MATAF was concerned lest this withdrawal render ineffective its interdiction campaign, which depended largely on medium bombers, General Eaker felt that in view of the static condition on the Italian front, another group could be spared. He urged, however, that no further withdrawals from the tactical air force be made in view of the necessity for keeping up the interdiction of the extensive rail and road nets supporting the German armies in Italy.108

The diminishing medium bomber strength increased the importance of fighter-bombers in the interdiction campaign. Although fighter-bombers from both XXII TAC and DAF had participated on 6 November in Operation BINGO, no further attempt was made to employ them against the Brenner until later in the month. Thereafter their efforts were indispensable to the maintenance of the blockade of Italy. The redeployment of the 42nd Wing coincided with deteriorating weather which prevented the B-25’s from reaching the international routes for the remainder of November so that it was necessary to call upon XXII TAC to maintain cuts on the lower end of the Brenner and to direct DAF to employ a good portion of its fighter-bomber effort against the northeastern routes.109

XXII TAC’s effort against the Brenner route commenced on 19 November when fighter-bombers postholed the tracks between Verona and Ala. From the 26th through 2 December, 148 sorties were flown against the line; concurrently, the zone of operations was extended north of Trento. On one of the early flights a strafing attack near Sant’ Ambrogio blew up a train and blasted 280 yards of trackage from the roadbed. Attacks were most devastating on 28 November, when forty-six P-47’s blew ten gaps in tracks over a forty-mile stretch near the southern extremity of the line. During December an average of twenty P-47’s ranged up and down the Brenner route daily, on occasion reaching as far north as San Michele, cutting tracks and attacking marshalling yards; pilots claimed 149 cuts on the line for the month. In addition, XXII TAC’s aircraft supplemented DAF’s and the 57th Wing’s efforts

on the Venetian plain by bombing crossings over the Brenta River on twelve occasions.110

In the meantime, DAF had begun to supplement the medium bomber attacks in northeastern Italy. On 22 November, Tactical made DAF responsible for the rail lines Mestre–Portogruaro, Treviso–Casarsa, and Nervesa–Casarsa, which were sections of the three coastal routes which crossed the Piave and Livenza rivers. On the same day DAF began cutting the line from Padua to Castelfranco and to Vicenza. But the heavy effort at Faenza, 21–24 November, and bad weather thereafter for the remainder of the month, hindered DAF’s first ten days of operations in northeastern Italy, although on the 29th its fighter-bombers struck bridges across the Livenza River. In December, the Venetian plain was the scene of a large part of DAF’s blows against communications. Particularly good results were achieved against rolling stock along the northern route to Udine, and, in addition to numerous attacks on open stretches of track, some eighteen attacks were made on rail bridges across the Piave and Livenza.111

Having called in its fighter-bombers to support the interdiction campaign, MATAF, on 1 December, also took action to strengthen the program by providing for round-the-clock attacks on targets north of the Po.112 Previously, the 47th Bombardment Group, XXII TAC’s night intruder group, had devoted most of its A-20 effort to the area south of the Po which was bounded on the west by Piacenza and on the east by the DAF/XXII TAC boundary; a lesser effort had covered the area north of the Po up to Verona.113 As the emphasis of bombers and fighter-bombers shifted farther to the north, it was appreciated that enemy night movement and repair effort would increase on the four main routes. Consequently, on 1 December, MATAF directed the employment of a portion of XXII TAC’s night bomber effort to the Brenner and of DAF’s to northeast Italy. XXII TAC responded by assigning several A-20’s to cover the Brenner line nightly as far north as Trento. Weather, however, rendered the effort largely ineffective. DAF’s night effort against the northeastern routes was limited owing to its duties on the Eighth Army front and to a commitment acquired on 3 November which called for the employment of three wings of medium and light bombers and four squadrons of fighters against Balkan targets on a first-priority basis to assist the Balkan Air Force to impede the German retreat from Yugos1avia.114

To complement the interdiction campaign, MATAF stressed the

importance of destroying the enemy’s accumulations of supplies in dumps. Because of the over-all fuel shortage among the German armed forces, it was believed that Kesselring’s quota of POL would be limited; hence the destruction of fuel in conjunction with the interdiction of supply lines entering Italy would have a major effect on the mobility of the German armies opposing the AAI.115 Although some effort had heen applied to targets in this category in September and October, it was not until 3 November that dumps were assigned a definite priority, corning last after the Brenner line and bridges over the rivers of northeastern Italy and the Po. MATAF then launched a large-scale assault on dunips and stores. Medium bombers, because of extensive commitments, limited their attacks on dumps to sixty sorties, all flown on 10–11 November against the Porto Nagaro supply dump and the Mestre fuel dump. But XXII TAC took up the task, and in the week of 16–22 November carried out a sustained campaign against enemy supplies, concentrating on fuel centers north of the Po, especially between the Po and the Brescia–Verona rail line, and ammunition dumps closer to the battle front, particularly in the vicinities of Bologna, Imola, and Faenza. Some eighteen fuel dumps, ten ammunition dumps, and sixteen others of the approximately fifty attacked were reported destroyed.116

Because of their value as alternate targets when communications were obscured by bad weather, dumps received greater attention during December, some 629 sorties being devoted to them.117 The anticipated resumption of offensive operations by Fifth Army in December and the German counterthrust in the Serchio Valley accounted for the concentration of these efforts on dumps (primary ammunition) in the Irnola, Bologna, and La Spezia areas.

Enemy shipping did not have to be seriously considered in the interdiction campaign in the fall of 1944. The advance of the Italian front to north of Pisa and Rimini and the invasion of southern France had reduced the zone of enemy coastal shipping, limiting it primarily to small ships plying the waters between Savona and Genoa and to the ports of Trieste, Pola, Venice, and Fiume in the upper Adriatic. Too, the German evacuation of Greece and the Aegean Islands in September and October had further reduced the need for water transportation in the Adriatic. Indeed, by September 1944, MACAF’s tasks of protecting rear areas and convoys, of antishipping strikes in the Gulf of Genoa and the northern Adriatic, and of air-sea rescue had become so reduced in importance that after the withdrawal of XII Fighter Command in

September, MACAF became and remained a small British organization.118 Although it continued until the end of the war to fly regular patrols, as its targers became increasingly scarce, its strength and effort showed a marked decline. From its August strength of 34 squadrons, with approximately 700 aircraft of all types (fighters, night fighters, bombers, and air-sea rescue craft), it was reduced by the end of October to 16 squadrons with a strength of approxiniately 380 aircraft. It remained at approximately that size until the end of the war.119 As the enemy submarine threat and air operations came to a virtual halt in the Mediterranean late in 1944 – thereby ending Coastal’s defensive role – and as surface vessels became increasingly scarce – thereby lessening its normal offensive role – its fighters and bombers turned their attention almost exclusively to assisting MATAF in its interdiction campaign.120

Only occasionally was it necessary for MAAF’s other elements to supplement MACAF’s antishipping strikes. On 4 September, 164 B-17’s dropped 490 tons of 500-pound bombs on the Genoa harbor, the base for the few remaining enemy submarines in the Mediterranean. By German admission, the attack destroyed seven submarines nearing completion, four submarines used for special operations, one transport submarine, and other small vessels; the submarine bases at both Genoa and Spezia were closed following the attack. Heavy bombers also made an occasional attack on the ports of Fiuine, Trieste, and Pola, where they not only damaged port facilities and shipbuilding installations but destroyed important stores of oil. Pola was attacked several times for the further reason that it held concentrations of small motorboats which the enemy used against Allied naval units operating off the Dalmatian coast.121

Twice during the fall medium bombers prevented the Germans from blocking ports of potential value to the Allies. In September, Admiral Cunningham, naval commander in chief in the Mediterranean, requested that the air forces sink the Italian liner Taranto which, it was believed, the Germans intended using as a block ship at La Spezia harbor. By sinking the vessel before it could be moved into position, the harbor could be saved for Allied use when captured. In response to the request, General Cannon called upon the highly efficient 340th Bombardment Group. On 23 September, the group, using an eighteen-plane formation, six of which were briefed to hit the stern, six the middle, and six the bow, executed a perfect attack. Bomb strike photos revealed three separate clusters completely covering the vessel; the

Taranto sank twenty-five minutes after the attack.122 General Cannon reported that this was the sixty-second consecutive pinpoint target which the 340th Group had attacked without a miss.123 On 28 November, seventeen B-25’s, this time from the 310th Group, sank another vessel at La Spezia harbor before it could be moved into position to block the channel.124

For the first time in several months it was necessary in November to carry out a series of counter-air force operations and to provide fighter escort for medium bombers. Actually, the air war in Italy had long since been won, and enemy aerial opposition to Allied operations, both air and ground, was so slight as to be scarcely worth mentioning. In fact, in mid-September when the GAF’s air strength was down to an estimated thirty Me-109’s at Ghedi, MATAF adopted the unprecedented* policy of sending out its mediums without fighter escort. The low rate of replacement of enemy aircraft, crews, and supplies precluded offensive tactics against Allied bomber formations and, furthermore, continuous fighter-bomber activity in the Po Valley was deemed reasonable protection to bombers from isolated attacks.125 By the middle of October, however, the 2nd Gruppo of the Italian Fascist Republic Air Force, trained and equipped in Germany, had become operational in Italy, and during the latter half of the month, MATAF’s crews, both fighter and bomber, reported encounters with hostile aircraft.126 The primary mission of these enemy fighters seemed to be the defense of the northern lines of communication and their efforts were concentrated over the Brenner. Small, scattered, and generally unaggressive enemy formations in October were replaced in November by aggressive forces ranging in size from fifteen to twenty and forty to fifty aircraft, and on the 5th, three B-26’s were lost and six damaged as twelve to fifteen enemy aircraft jumped a formation just as it reached its targets at Rovereto. Although no further losses were sustained for the next two weeks, there were almost daily sightings of and a few skirmishes with enemy aircraft.127

Though not carrying out a sustained campaign against this resurgence of enemy air power, MATAF arranged to keep the principal airdromes under surveillance. Daily fighter sweeps began to include patrols over the area from which enemy aircraft were operating. A-20’s

* Unprecedented to the extent that it was the first time a directive was issued on the subject. On earlier occasions enemy air forces in Italy had been so weak that mediums had flown without escort.

of the 47th Bombardment Group on their night intruder missions flew over one or more of the enemy fields on almost every night from 11 through 23 November, and on a few occasions chose enemy airdromes as their primary target. On 14 November MATAF rescinded its previous policy of not requiring fighter escort for medium bombers and ordered XXII TAC to provide either target-area cover or close escort for missions where enemy fighters were likely to be encountered.128

The necessity for escort was short-lived, however, as MASAF soon climaxed the counter-air campaign. On several occasions early in November heavy bomber crews had reported encounters with enemy aircraft based in northern Italy, and on the 16th, SAF aircraft, returning from southern Germany, met the first serious opposition from these planes. Some thirty to forty enemy fighters, contacted in the Udine area, concentrated on stragglers from the bomber formation, and despite the efforts of P-51 escorts, fourteen heavy bombers were reported missing from the operation. The P-51’s accounted for eight enemy aircraft destroyed, two probably destroyed, and two damaged; bombers claimed one destroyed.129 By that time approximately 100 enemy fighters had been located on the airdromes at Aviano, Vicenza, Villafranca, and Udine. In view of the increased size and aggressiveness of the enemy’s air strength, SAF decided to devote a day’s effort to reducing the threat. Actually the enemy’s bases were in MATAF’s area of responsibility but as they were located at the limit of range for TAF’s aircraft General Twining felt that assistance from SAF would be welcomed, and on the night of 17 and the day of 18 November, Strategic carried our a series of devastating attacks on the four fields. No opposition was encountered although 186 P-51’s patrolled the target areas to take care of any reaction that might develop.130

Although by the last week of November enemy air opposition had become almost nonexistent, it was appreciated that perhaps the bad weather which was playing such havoc with Allied air operations prevented a fair evaluation of the enemy’s air potential. But when clearing skies allowed a resumption of Allied air activity, the Luftwaffe was noticeably absent. It would never again be a factor in the Mediterranean war.

The 51st Troop Carrier Wing, after completing its assignments during DRAGOON, had turned its two groups, of four squadrons each, to their routine tasks of medical evacuation and of moving troops and supplies within Italy or between the peninsula and Corsica and France.

In November, Troop Carrier took on additional duties when MATAF assumed responsibility for supplying the Partisans in northern Italy.131

Over the Balkans

In the meantime, Italy-based aircraft had become increasingly active in the Balkans. On 20 August, Russian troops crashed through Rumania, forced a capitulation of Bulgaria, and by the end of September had developed two offensives into Yugoslavia in conjunction with increased Partisan activity. Then Soviet forces, after joining with Marshal Tito’s guerrillas to capture Belgrade on 20 October, turned north into Hungary. This rapid Russian drive up the Danube made necessary a German withdrawal from Greece, southern Yugoslavia, and eastern Hungary.132