Chapter 2: The SOS and ETOUSA in 1942

BOLERO Is Born

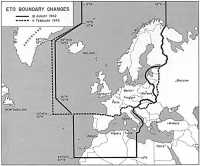

The first major task confronting the newly activated ETOUSA, beyond its internal organization, was to prepare for the reception of the American forces which were scheduled to arrive in the British Isles. The strategic decision which provided the basis for this build-up was taken in April 1942.

At the ARCADIA Conference in Washington in December 1941-January 1942, American and British military leaders had taken steps to allocate shipping and deploy troop units, had determined on the principle of unity of command, and had created the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) as an overall combined coordinating agency. Despite the unexpected manner in which the United States had been drawn into the war, they also reaffirmed the earlier resolution to give priority to the defeat of Germany. Beyond this, however, no decisions were made on how or where the first offensives were to be carried out. In 1941 British planners had drawn up a plan, known as ROUNDUP, for a return to the Continent. But ROUNDUP was not conceived on the scale required for an all-out offensive against a strong and determined enemy. It was designed rather to exploit a deterioration of the enemy’s strength, and to serve as the coup de grâce to an enemy already near collapse. It reflected only too well the meager resources then available to the British. The conferences at ARCADIA gave more serious consideration to a plan for the invasion of northwest Africa, known as GYMNAST. This also became academic in view of the demands which the Pacific area was making on available troops and shipping. The ARCADIA deliberations therefore led to the conclusion that operations in 1942 would of necessity have to be of an emergency nature, and that there could be no large-scale operations aimed at establishing a permanent bridgehead on the European Continent that year.

In the first hectic months after American entry into the war, when the United States was preoccupied with measures to check Japanese expansion toward Australia, U.S. planners had not agreed on a long-range strategy. But an early decision on ultimate objectives was urgently needed if the American concept of a final decisive offensive was ever to be carried out. The President urged immediate action on such a guide, and in March 1942 the Operations Division of the War Department worked out a plan for a full-scale invasion of Europe in 1943. General Marshall gave the proposal his wholehearted

support and, after certain revisions in language had been made, presented it to the President on 2 April. The Commander in Chief promptly approved the plan and also the idea of clearing it directly with the British Chiefs of Staff in London. General Marshall and Harry Hopkins accordingly flew to England immediately and, in discussions between 9 and 14 April, won the approval of the British Chiefs of Staff for the “Marshall Memorandum.” The plan that it embodied had already been christened BOLERO.

It contemplated three main phases: a preparatory period, the cross-Channel movement and seizure of beachheads between Le Havre and Boulogne, and the consolidation and expansion of the beachheads and beginning of the general advance. The preparatory phase consisted of all measures that could be undertaken in 1942 and included establishment of a preliminary active front by air bombardment and coastal raids, preparation for the possible launching of an emergency operation in the fall in the event that either the Russian situation became desperate or the German position in Western Europe was critically weakened, and immediate initiation of procurement, matériel allocations, and troop and cargo movements to the United Kingdom. The principal and decisive offensive was to take place in the spring of 1943 with a combined U.S.-British force of approximately 5,800 combat aircraft and forty-eight divisions.

Logistic factors were the primary consideration governing the date on which such an operation could take place. It was proposed that at the beginning of the invasion approximately thirty U.S. divisions should be either in England or en route, and that U.S. strength in Britain should total one million men. To move such a force required a long period of intensive preparation. Supplies and shipping would have to be conserved, and all production, special construction, training, troop movements, and allocations coordinated to a single end. The shortage of shipping was recognized as one of the greatest limitations on the timing and strength of the attack, and it was therefore imperative that U.S. air and ground units begin moving to the United Kingdom immediately by every available ship. Because the element of time was of utmost importance, the Marshall Memorandum emphasized that the decision on the main effort had to be made immediately to insure that the necessary resources would be available.1

Such a decision was obtained with the acceptance of the BOLERO proposal by the British in mid-April. Despite the succession of defeats in the early months of 1942, approval of the Marshall Memorandum instilled a new optimism, particularly among American military leaders. There now was hope that what appeared to be a firm decision on the Allies’ major war effort would put an end to the dispersion of effort and resources. The decision of April provided a definite goal for which planners in both the United States and the United Kingdom could now prepare in detail.

To implement such planning for the BOLERO build-up a new agency was established. Within a week after agreement was reached in London, Brig. Gen. Thomas T Handy, Army member of the Joint Staff Planners of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, on the suggestion of General Eisenhower, proposed the establishment of a combined U.S.-British committee for detailed

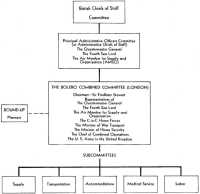

BOLERO planning,2 and on 28 April the Combined Chiefs of Staff directed the formation of such an agency as a subcommittee of the Combined Staff Planners. This agency was known as the BOLERO Combined Committee and consisted of two officers from OPD, two Navy officers, and one representative from each of the three British services. The committee was to have no responsibility for preparing tactical plans. Its mission was to “outline, coordinate and supervise” all plans for preparations and operations in connection with the movement to, and reception and maintenance of American forces in, the United Kingdom. This would cover such matters as requirements, availability, and allocation of troops, equipment, shipping, port facilities, communications, naval escort, and the actual scheduling of troop movements.3 As observed by its chairman, Col. John E. Hull, at the first meeting of the BOLERO Combined Committee on 29 April 1942, the new agency’s principal business would be to act as a shipping agency.4

A similar committee, known as the BOLERO Combined Committee (London), was established in England. The London committee’s main concern was with the administrative preparation for the reception, accommodation, and maintenance of U.S. forces in the United Kingdom. Working jointly, the two agencies were to plan and supervise the entire movement of the million-man force which was scheduled to arrive in Britain within the next eleven months. To achieve the closest possible working arrangement, a system of direct communications was set up between the two committees with a special series of cables identified as Black (from Washington) and Pink (from London). The exchange of communications began on the last day of April, when the Washington committee requested information on British shipping capacities and urged that the utmost be done to get the movement of troops started promptly in order to take advantage of the summer weather.5 By the first week in May detailed planning for the movement and reception of the BOLERO force was under way in both capitals.

For several weeks after the April decision on strategy and the establishment of the Combined Committees considerable confusion arose over the exact scope and meaning of the term BOLERO. The proposal that General Marshall took with him to London had carried no code word; it was titled simply “Operations in Western Europe.” The code name BOLERO had first become associated with the plan in the War Department OPD. In that division’s first outlines of the plan BOLERO embodied not only the basic strategic concept of a full-scale cross-Channel attack in 1943 but also the preparatory phases, including the supply and troop build-up in the United Kingdom and any limited operations which might be carried out in 1942. Within a few weeks two additional code names had come into use for specific aspects of the over-all plan. General Marshall’s memorandum had spoken of a “modified plan” which it might be necessary to carry out on an “emergency” basis. By this was meant a limited operation which might be launched against the

European Continent in the event the Red armies showed signs of collapse or the German position in France was materially weakened. For such an operation the scale of possible American participation would be particularly limited because of the shortage of shipping. It was estimated that not more than 700 combat planes and three and a half divisions would have arrived in England by mid-September, although considerably larger forces would be equipped and trained in the United States and ready to take part as shipping became available. This “emergency” or “modified plan” soon came to be known as SLEDGEHAMMER, a name which Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill had coined earlier in connection with similar plans made by the British. Similarly, the more purely tactical aspects of the BOLERO plan—the actual cross-Channel attack—were soon commonly referred to by the name which British planners had used in connection with their earlier plans for continental operations, ROUNDUP, even though those earlier plans bore little resemblance to the project now in preparation. There already existed in London a ROUNDUP committee engaged in the administrative planning for a cross-Channel operation.

The increased use of SLEDGEHAMMER and ROUNDUP in communications produced an inevitable confusion and doubt over the exact meaning of BOLERO. Late in May USAFBI pointed out to the War Department the wide divergency in views held in Washington and London,6 and OPD finally took steps to have the term BOLERO defined. Early in July a presidential directive was issued stipulating that BOLERO would cover specifically the “preparation for and movement of United States Forces into the European Theater, preparation for their reception therein and the production, assembly, transport, reception and storage of equipment and supplies necessary for support of the United States Force in operations against the European Continent.”7 Thenceforth the use of the name BOLERO was confined to the plan for the great build-up of men and matériel in the United Kingdom.

The inauguration of the BOLERO buildup initially posed a fourfold problem: the establishment of a troop basis; a decision on the composition of the BOLERO force, including the priority in which units were desired in the United Kingdom; setting up a shipping schedule; and preparing reception and accommodation facilities in the United Kingdom. Designating the priority in which various units were desired and preparing their accommodations in the British Isles were problems that had to be solved in the theater. Establishing the troop basis or troop availability and setting up a shipping schedule were tasks for the War Department. the shipping schedule more specifically in the province of the BOLERO Combined Committee in Washington. But the four tasks were interrelated, and required the closest kind of collaboration between the theater headquarters, British authorities, the two Combined Committees, the OPD, and other War Department agencies.

One step had already been taken toward establishing a troop basis when the Marshall Memorandum set the goal of a build-up of a million men in the United Kingdom by 1 April 1943. In fact, this was the only figure that had any near-stability

in the rapidly shifting plans of the first months. The accompanying target of 30 U.S. divisions in England or en route by April 1943 represented hardly more than wishful thinking at this time. It proved entirely unrealistic when analyzed in the light of movement capabilities, and War Department planners within a matter of weeks reduced the figure first to 25 divisions, then to 20, and finally to 15.8

Meanwhile planners in both the United States and in the United Kingdom had begun work on a related problem—the composition of the BOLERO force, and the priority in which units were to be shipped. In determining what constituted a “balanced force” there was much opportunity for disagreement. Ground, air, and service branches inevitably competed for what each regarded as its rightful portion of the total troop basis. A survey of manpower resources in the spring of 1942 revealed a shocking situation with regard to the availability of service units. Only 11.8 percent of the 1942 Army troop basis had been allotted for service troops, a woefully inadequate allowance to provide support for combat troops in theaters of operations. Neglect of the service elements in favor of combat troops reflected an attitude which was common before the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, but which hardly squared with the proven logistic requirements of modern warfare. A study made in the War Department SOS in April showed that, of the total AEF force of nearly two million men in France at the end of World War I, 34 percent were service troops, exclusive of the service elements with the ground combat and air force units. On the basis of the 1917—18 experience the study estimated that the SOS component of the BOLERO force should be at least 35 percent, or about 350,000 men, and General Somervell requested OPD to take these figures into consideration in any troop planning for BOLERO.9

The earliest breakdown of the BOLERO force troop basis provided that approximately 26 percent of the troop basis be allotted to service forces. The Combined Committee in Washington tentatively suggested the following composition of the U.S. force early in May, and requested USAFBI’s opinion on the proportions:10

| Type | Number |

| Total | 1,042,000 |

| Air Forces | 240,000 |

| Services of Supply | 277,000 |

| Ground Forces | 525,000* |

* 17 Divisions plus supporting units.

These figures already embodied a small reduction of an earlier ground force troop basis made to preclude a reduction in the service troop allocation.11 Approximately one fourth of the BOLERO force was thus allotted to service troops.

Later in May the War Department established the general priorities for the movement of American units. Air units were to be shipped first, followed by essential SOS units, then ground forces, and then additional service units needed to

prepare the ground for later shipments.12 By the end of the month General Chaney, who was still in command in the United Kingdom, submitted lists of priorities within the War Department’s announced availabilities.13

There still remained the problem of finding and making available the numbers and types of troop units which the theater desired. This presented no insurmountable difficulty so far as combat units were concerned, since adequate provision had been made for their activation and training. But in the spring of 1942 few trained service troops were available for duty in overseas theaters, and service troops beyond all others were required first in the United Kingdom. It was imperative that they precede combat units in order to receive equipment and supplies, prepare depots and other accommodations, and provide essential services for the units which followed. Certain types of units were not available at all; others could be sent with only some of their complements trained, and those only partially.14 On the assumption that “a half-trained man is better than no man,” General Lee willingly accepted partially trained units with the intention of giving them on-the-job training, so urgently were they needed in the United Kingdom.15 As an emergency measure, the War Department authorized an early shipment of 10,000 service troops.16

Scheduling the shipment of the BOLERO units proved the most exasperating problem of all. The shortage of shipping circumscribed the planners at every turn, strait-jacketing the entire build-up plan and forcing almost daily changes in scheduled movements. U.S. shipping resources were limited to begin with, and were unequal to the demands suddenly placed on them by planned troop deployments in both the Atlantic and Pacific. War Department planners estimated early in March 1942 that 300,000 American troops could be moved to the United Kingdom by October. This prospect was almost immediately obscured by decisions to deploy additional British forces to the Middle East and the Indian Ocean area and U.S. troops to the Southwest Pacific, and by the realization that enemy submarines were taking a mounting toll of Allied shipping. Late in March the earlier optimism melted away in the face of estimates that large troop movements could not begin until late in the summer, and that only 105,000 men, including a maximum of three and a half infantry divisions, might be moved to Britain by mid-September.

British authorities had offered some hope of alleviating the shortage in troop lift by transferring some of their largest liners to the service of the BOLERO buildup as soon as the peak deployment to the Middle East had passed. But the shortage of cargo shipping was even more desperate, and the fate of the build-up depended on the balancing of cargo and troop movements. There was particular urgency about initiating the build-up during the summer months, in part to take advantage of the longer days which permitted heavier

unloadings at British ports, and in part to avoid the telescoping of shipments into a few months early in 1943 in view of the unbearable congestion it would create in British ports. In mid-April, at the time of the Marshall visit to England, American authorities took some encouragement from a British offer to provide cargo shipping as well as troopships on the condition that American units cut down on their equipment allowances, particularly for assembled vehicles. But these commitments were unavoidably vague, for it was next to impossible to predict what shipping would be available for BOLERO in the summer of 1942, when the Allies were forced to put out fires in one place after another.17

The hard realities of the shipping situation made themselves felt again shortly after the London conference. On 9 May the War Department issued a “Tentative Movement Schedule” providing for the transfer of about 1,070,000 American troops to the United Kingdom by 1 April 1943.18 The title was immediately recognized as a misnomer, for the figure simply indicated the number of troops which would be available for movement and bore no relationship to actual shipping capabilities. On the very day this so-called movement schedule was issued, the BOLERO Combined Committee of Washington revealed the sobering facts regarding the limitations which shipping imposed, notifying the London committee that a build-up of not more than 832,000 could be achieved in the United Kingdom by 1 April 1943.19 There was even talk of lowering the goal to 750,000 and so allocating the various components as to create a balanced force in case a reduction proved necessary. The revised figure would have been 250,000 short of the million- man target and more than 300,000 short of the total number of troops available. For the moment it again appeared that a force of only 105,000 men could be moved to the United Kingdom by September. Even this number was to be reached only by postponing the evacuation of British troops from Iceland. The Combined Chiefs of Staff, in approving these shipments, noted that while long-range schedules could be projected it was impossible to forecast what the shipping situation might be in a few months.20

The warning that shipping capacity might fluctuate was soon justified. Within a week British officials were able to promise additional aid for the month of June by diverting troop lift from the Middle East-Indian Ocean program. They offered the use of both of the “monsters,” the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, and part-time use of other ships, including the Aquitania, beginning in August.21 Accordingly in mid-May it was possible to schedule an additional 45,000 for shipment in June, July, and August, which would bring the strength in the United Kingdom to approximately 150,000 by 1 September 1942.22 Part of the accelerated movement

was to be accomplished by the overloading of troop carriers. The long-range shipping schedule now projected a build-up of 892,000 by 1 April 1943.

These schedules had no more permanency than those prepared earlier. A further revision was made early in June, slightly reducing the shipments for July and August. Later in June, the darkest month of the war, fresh disasters threatened to upset the entire build-up projected for that summer.

In the meantime the theater had attempted to reconcile its BOLERO troop allotment with limitations imposed by the shipping shortage. Early in June the War Department had submitted to ETOUSA a troop basis made up as follows:

| Type | Number |

| Total | 1,071,060 |

| Air Forces | 206,400 |

| Services of Supply | 279,145 |

| Headquarters Units | 3,932 |

| Combat Divisions (20) | 278,473 |

| Ground Support Units | 303,110 |

The deficit in shipping, however, obliged ETOUSA to determine whether, within the limitations, a force of adequate strength and balance could be built up in the United Kingdom. Senior commanders there had decided that a minimum of fifteen divisions out of the twenty provided for in the War Department troop basis must be present in the United Kingdom on the agreed target date. Theater planners therefore estimated that 75,000 places could be saved by dropping a maximum of five divisions. Another saving of 30,000 could be realized by deferring the arrival of certain ground support troops until after 1 April. Even these cuts left a deficit of 35,000 places, and the theater therefore found it necessary to direct its major commands to make a detailed study of their personnel requirements with a view toward further reducing troop requirements and deferring shipments. These steps were taken reluctantly, for the theater deplored deferring the arrival of units which it thought should be in the United Kingdom by the target date, and naturally would have felt “more comfortable” with assurances that the million-man build-up would be achieved.23

A few weeks later the theater headquarters made a new statement of its requirements for a balanced force. It called for a force of sixteen divisions and provided for reductions in all other components to the following numbers:

| Air Forces to | 195,000 |

| Services of Supply | 250,000 |

| Divisions (16) | 224,000 |

| Ground Support Units | 292,564 |

But the estimate included a new requirement for 137,000 replacements, which had the net effect of increasing the troop basis to approximately 1,100,000.24 The deficit in shipping consequently became greater than before. In attempting to achieve the target of the BOLERO plan the two nations thus faced an insuperable task in the summer of 1942. By the end of July, however, a major alteration in strategy was destined to void most of these calculations.

BOLERO Planning in the United Kingdom, May–July 1942: the First Key Plans

While the War Department wrestled with the shipping problem, preparations

for the reception and accommodation of the BOLERO force got under way in the United Kingdom. The principal burden of such preparation was assumed at first by British agencies, which had been prompt to initiate planning immediately after the strategic decisions made at Claridge’s in April, a full month before the arrival of General Lee and the activation of the SOS. British and American planners had of course collaborated in preparing for the arrival of the MAGNET force in Northern Ireland, but the BOLERO plan now projected a build-up on a scale so much greater than originally contemplated that it was necessary to recast accommodation plans completely.

The million troops that the War Department planned to ship to the European theater were destined to go to an island which had already witnessed two and one-half years of intensive war activity. Now the United Kingdom was to be the scene of a still vaster and more feverish preparation as a base for offensive operations. The existence of such a friendly base, where great numbers of troops and enormous quantities of the munitions of war could be concentrated close to enemy shores, was a factor of prime importance in determining the nature of U.S. operations against the continental enemy. It was a factor perhaps too frequently taken for granted, for the United Kingdom, with its highly developed industry and excellent communications network, and already possessing many fixed military installations, including airfields and naval bases, was an ideal base compared with the underdeveloped and primitive areas from which American forces were obliged to operate in many other parts of the world.

The United Kingdom already supported a population of 48,000,000 in an area smaller than the state of Oregon. In the next two years it was to be further congested by the arrival of an American force of a million and a half, requiring such facilities as troop accommodations, airfields, depots, shops, training sites, ports, and rolling stock. Great Britain had already carried out a far more complete mobilization than was ever to be achieved in the United States. As early as 1941, 94 out of every 100 males in the United Kingdom between the ages of 14 and 64 had been mobilized into the services or industry, and of the total British working population of 32,000,000 approximately 22,000,000 were eventually drafted for service either in industry or the armed forces.25 The British had made enormous strides in the production of munitions of all types. In order to save shipping space they had cut down on imports and made great efforts to increase the domestic output of food. There was little scope for accomplishing such an increase in a country where nearly all the tillable land was already in cultivation. In fact, the reclamation of wasteland was more than offset by losses of farm land to military and other nonagricultural uses. Raising the output of human food could be accomplished only by increasing the actual physical yield of the land, therefore, and by increasing the proportion of crops suitable for direct human consumption, such as wheat, sugar beets, potatoes, and other vegetables.

Despite measures such as these the British had accepted a regimentation that involved rigid rationing of food and clothing, imposed restrictions on travel, and brought far-reaching changes in their working and living habits. For nearly three years they had lived and worked under complete blackout; family life had been broken up both by the withdrawal of men and women to the services and by evacuation and billeting. Production had been plagued by the necessity to disperse factories in order to frustrate enemy air attacks and by the need to train labor in new tasks. Nearly two million men gave their limited spare time after long hours of work for duty in the Home Guard, and most other adult males and many women performed part-time civil defense and fire guard duties after working hours. An almost complete ban on the erection of new houses and severe curtailment of repair and maintenance work on existing houses, bomb damage, the necessity for partial evacuation of certain areas, and the requisition of houses for the services all contributed to the deterioration of living conditions. Britain’s merchant fleet, which totaled 17,500,000 gross tons at the start of the war, had lost more than 9,000,000 tons of shipping to enemy action, and its losses at the end of 1942 still exceeded gains by about 2,000,000 tons. A drastic cut in trade had been forced as a result. Imports of both food and raw materials were reduced by one half, and imports of finished goods were confined almost exclusively to munitions. Before the war British imports had averaged 55,000,000 tons per year (exclusive of gasoline and other tanker-borne products). By 1942 the figure had fallen to 23,000,000—less than in 1917.26

In an economy already so squeezed, little could be spared to meet the demands for both supplies and services which the reception and accommodation of the BOLERO force promised to make upon it. It is not surprising that British planners should visualize the impact which the build-up would have on Britain’s wartime economy, and they were quick to foresee the need for an adequate liaison with the American forces in the United Kingdom, and for administrative machinery to cope with build-up problems. Planning in the United Kingdom began in earnest with creation of the London counterpart of the BOLERO Committee in Washington on 4 May 1942. The BOLERO Combined Committee (London) was established under the chairmanship of Sir Findlater Stewart, the British Home Defence Committee chairman. Its British membership included representatives of the Quartermaster General (from the War Office), the Fourth Sea Lord (from the Admiralty), the Air Member for Supply and Organization (from the Air Ministry), the C-in-C (Commander-in-Chief) Home Forces, the Chief of Combined Operations, the Ministry of War Transport, and the Ministry of Home Security.27

U.S. forces in the United Kingdom were asked to send representatives to the committee. Four members of General Chaney’s staff—General Bolté, General McClelland, Colonel Barker, and Colonel Griner—attended the first meeting, held on 5 May at Norfolk House, St. James’s Square. Because of the continued shortage of officers in Headquarters, USAFBI,

however, regular U.S. members were not immediately appointed, and American representation varied at each meeting.28 General Lee first attended a session of the BOLERO Combined Committee with a large portion of his staff on 26 May, two days after he arrived in the United Kingdom.29

The mission of the London Committee was “to prepare plans and make administrative preparation for the reception, accommodation and maintenance of United States Forces in the United Kingdom and for the development of the United Kingdom in accordance with the requirements of the ROUNDUP plan.”30 The committee was to act under the general authority of a group known as the Principal Administrative Officers Committee, made up of the administrative heads of the three British services—the Quartermaster General, the Fourth Sea Lord, and the Air Member for Supply and Organization. To this group major matters of policy requiring decision and arbitration were to be referred. Each of the “administrative chiefs of staff,” as they were first called, was represented on the Combined Committee. Sir Findlater Stewart commented at the first meeting that much detailed planning would be required. But it was not intended that the committee become immersed in details. It was to be concerned chiefly with major policy and planning. The implementation of its policies and plans was to be accomplished by the British Quartermaster General through the directives of the Deputy Quartermaster General (Liaison) and carried out by the various War Office directorates (Quartering, Movements, for example) and by the various departments of the Ministries of Labor, Supply, Works and Buildings, and so on. These would coordinate plans with the Combined Committee through the latter’s subcommittees on supply, accommodation, transportation, labor, and medical service, which were shortly established to deal with the principal administrative problems with which the Committee was concerned. (Chart 2)

One of the key members of the Combined Committee was the Deputy Quartermaster General (Liaison), Maj. Gen. Richard M. Wootten. This officer was not only the representative of the British Quartermaster General on the London Committee and as such responsible for the implementation of the committee’s decisions, but also the official agent of liaison with the American forces. British problems with respect to BOLERO were primarily problems of accommodations and supply, which in the British Army were the responsibility of the Quartermaster General (Lt. Gen. Sir Walter Venning). It was logical, therefore, that his office become the chief link between the War Office and the American Services of Supply. To achieve the necessary coordination with the Americans on administrative matters the War Office established a special branch under the Quartermaster General to deal exclusively with matters presented by the arrival of U.S. forces. This branch was known as Q (Liaison), and was headed by General Wootten. Q (Liaison) was further divided into two sections, one known as Q (Planning Liaison) to deal with the executive side of planning for reception and accommodation, and the other as Q (American Liaison) to deal with problems of the relationship

Chart 2: The Bolero Administrative Organization in the United Kingdom

Representation on the subcommittees varied. For example, the Accommodations Subcommittee had representatives from the War Office, the Admiralty, the Ministries of Air, Works and Buildings, and Health, and from ETOUSA. The Subcommittee on Supply had representatives War Transport, and Air, and U.S. representatives. The Transportation Subcommittee had representatives from the War Office, the Railway Executive committee, the Home Forces, the War Office Director of Movements, the Ministries of War Transport, Air, and Production, and ETOUSA.

between British and American armies in matters of discipline, morale, welfare, and public relations.

It was through the office of the Deputy Quartermaster General (Liaison) that all the BOLERO planning papers were issued in the next year and a half. General Wootten issued his first directive on 5 May 1942, the same day on which the BOLERO Combined Committee (London) held its first meeting. In it he emphasized strongly the inseparable relationship between BOLERO and ROUNDUP, and sounded the keynote of the committee’s early deliberations by stressing the need for speed. The only purpose of the BOLERO build-up was to ready an American contingent of 1,000,000 men to take part in a cross-Channel invasion in April 1943. In view of the necessity to complete all preparations in less than a year, Wootten noted: “Every minute counts, therefore there must be a rapid equation of problems whilst immediate and direct action on decisions will be taken, whatever the risks, without of course disturbing the defense of this country as the Main Base.” Planners were enjoined to “produce the greatest possible effort in their contribution to defeat ‘Time,’ so that the goal might be met within the allotted twelve months.”31

It was intended, therefore, that the ROUNDUP plan would be the governing factor in the administrative development of the United Kingdom as a base of operations, although this objective actually proved difficult at first in the absence of a detailed operational plan. But the BOLERO Combined Committee planned to work in close consultation with the parallel ROUNDUP administrative planning staff, and the Deputy Quartermaster General immediately asked for an outline of requirements both in labor and materials for the development of BOLERO, even though he recognized that these could only be estimates at this time. He directed that basic planning data and information be submitted so that a plan for the location of installations and facilities could be issued within the next few weeks. In fact, General Wootten did not await the receipt of planning estimates. As preliminary steps he announced that the Southern Command would be cleared of British troops, and that a census of all possible troop accommodations, depot space, and possible expansion in southern England was already being made. Certain projects for base maintenance storage and for personnel accommodation were already being studied and carried out. Acutely aware of the limited time available, General Wootten foresaw the necessity of making a large allotment of British civil labor to these projects, and, lacking definite shipping schedules from the United States, he proposed to start preparations at once for an initial force of 250,000 which he assumed would arrive between August and December. These preparations included projects for troop quarters, the construction of four motor vehicle assembly plants, and the clearance of storage and repair facilities for this force. He then proposed to deal with accommodations and storage for a second increment of 250,000. General Wootten attacked the gigantic task with vigor and with full comprehension of the myriad problems and the measures which would have to be taken to receive a force of a million men. In the first planning paper he raised a multitude of questions which he knew must be answered, and made numerous suggestions

on the most economic use of existing accommodations, on methods of construction, and on the demands which might have to be made on the civil population.32

Within a few weeks the BOLERO Combined Committee appointed subcommittees on accommodations, transportation, and medical service, drawing on the War Office, the Admiralty, U.S. representatives, and the various Ministries of Health, War Transportation, and Works and Buildings for representation according to interest and specialty. The Combined Committee met six times in May and by the end of the month had gathered sufficient information and planning data to enable the Deputy Quartermaster General to outline for the first time in some detail the problem of receiving and accommodating the BOLERO force. This outline was known as the First Key Plan and was published on 31 May 1942. The First Key Plan was not intended as a definitive blueprint for the reception and accommodation of the American forces, the title itself indicating the probability of revisions and amendments. But it served as a basic outline plan for the build-up which was to get under way immediately. The Combined Committee and its subcommittees continued to meet and discuss various BOLERO problems in June and July, and additional planning papers and directives were issued by the Deputy Quartermaster General dealing with specific aspects of reception problems. On 25 July the more comprehensive Second Edition of the BOLERO Key Plan was published.

Although issued by the British Deputy Quartermaster General, the Key Plans were confined primarily to a consideration of U.S. requirements. Their object was stated as follows: “to prepare for the reception, accommodation and maintenance of the U.S. Forces in the United Kingdom,” and “to develop [the United Kingdom] as a base from which ROUNDUP operations 1943 can be initiated and sustained.”33

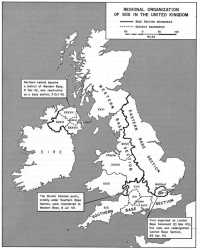

The July edition of the Key Plan reiterated that ROUNDUP should be the governing factor in developing Britain as a base. But in the absence of any indication as to how cross-Channel operations were to develop, and lacking a detailed operational plan, it was accepted that administrative plans could be geared to ROUNDUP only “on broad lines,” and that more detailed planning must await a fuller definition of the type and scope of the operations envisaged. One major assumption was made at an early date, however, and had a profound influence on the work of the BOLERO Committee. This was the assumption early in May which determined the location of U.S. forces in the United Kingdom. The committee noted that the general idea of any plan for a cross-Channel operation appeared to indicate that U.S. troops would be employed on the right and British troops on the left, and that U.S. forces would therefore embark from the southwestern ports when the invasion was launched. Since American personnel and cargo were to enter the United Kingdom via the western ports—that is, the Clyde, Mersey, and Bristol Channel ports—it was logical that they be concentrated in southwestern England, along the lines of communications between the two groups of ports. Such an arrangement would also avoid much of the undesirable cross traffic between American and British forces at the time of embarkation for the

cross-Channel movement.34 Thus the main principle governing the distribution of U.S. forces in the United Kingdom was that they be located primarily with a view to their role in ROUNDUP. It was not by accident, therefore, that the great concentration of American ground forces was destined at an early date to take place in the Southern Command area of the United Kingdom, and the early BOLERO planning dealt almost exclusively with that area.

The principal concern of the London Committee and the Deputy Quartermaster General was to find housing, depot space, transportation, and hospitalization for the projected BOLERO force. The size of this force had originally been set at a round figure of one million men. In the process of breaking down this figure into a balanced force of specific types and numbers of units, ETOUSA had by mid-May arrived at a troop basis of 1,049,000, and this was the working figure used in the First Key Plan.35 This figure underwent continuing refinement in the following weeks. The Second Edition of the Key Plan reflected ETOUSA’s upward revisions in June and used a troop basis of 1,147,000 men, with eighteen divisions.36

The BOLERO planners in the United Kingdom, like the Washington Committee, were well aware of the shipping shortage and based their program on the assumption that not more than approximately 845,000 of the projected 1,147,000 would arrive in the British Isles by 1 April 1943. But to establish a force of even that size presented an appalling movement problem, not only across the Atlantic, but from British ports to inland accommodations. The London Committee at one of its first meetings foresaw the cargo-shipping shortage as one of the greatest limitations on the movement of so large a force and considered some of the “heroic measures” which it thought were called for to reduce the problem to manageable dimensions. These included stringent economy measures, such as a further cutting of the U.K. import program, keeping down reserves and freight shipments to the lowest level, and scaling down vehicle allowances to the lowest possible figures. The problem of vehicle shipments was given particular attention because of the huge stowage space or requirements involved, and the committee advocated the shipment of as many unassembled partially assembled vehicles as possible and the construction of assembly plants in the United Kingdom.37

The magnitude of the movement problem within the United Kingdom is best illustrated by the tonnage which it was estimated would have to be handled, and the number of trains required for port clearance. Monthly troop arrivals were expected to average almost 100,000 men. To move such numbers would require about 250 troop trains and 50 baggage trains per month. The build-up of equipment and supplies for these forces was expected to require 120 ships per month, carrying 450,000 tons, in addition to approximately 15,500 vehicles, mostly in single and twin unit packs. To clear this

Crates of Partially Assembled Jeeps being unloaded at an assembly shop

tonnage inland from the ports alone would require 75,000 freight cars per month, the equivalent of 50 special freight trains per day.38

Reception in itself thus posed a formidable problem for the British both because of the limitations on the intake capacity of the ports and because of the added burden on the transportation system. Since the restriction on port discharge arose mainly from the shortage of dock labor, ETOUSA immediately took steps to arrange for the shipment of eight port battalions and three service battalions by the end of September, and for additional port units in succeeding months to augment the British labor force. The United Kingdom possessed an excellent rail network and the system was in good condition at the outbreak of the war. At that time it consisted of 51,000 miles of track, nearly 20,000 of which constituted route mileage, and it possessed nearly 20,000 locomotives, 43,000 passenger cars, and 1,275,000 freight “wagons.”39 Control of the railways had been greatly simplified by the consolidation of 123 separate companies into four large systems in 1923. These had come under the control of the government in 1939 through the Emergency Powers Defence Act, a control which

British “Goods Vans” unloading at a quartermaster depot

extended to docks, wharves, and harbors. Although the British railways easily withstood the first impact of the war with its increased demands and enemy bombings, it was hard put to accept the added burden which the U.S. build-up now entailed. The Movement and Transportation Sub-Committee of the Combined Committee estimated that the additional traffic resulting from BOLERO would require 70 freight trains per day. By the summer of 1942 the railways were already running 5,000 special trains for troops and supplies every month over and above normal traffic,40 and their net ton-mileage eventually surpassed prewar performance by 40 percent.41 An example of the remarkable degree of control and coordination and of the density of traffic on the British railways in wartime is seen in the scale of activity at Clapham Junction, on the Southern Railway south of London, which saw the passage of more than 2,500 trains each day.42

The British roads had been suffering from a deficiency of rolling stock for some time. The shortage of locomotives, in particular, had necessitated frequent cancellations of freight movements in the previous

English railway station scene with U.S. unit waiting to board train

winter (658 trains in one week in March). For troop and cargo arrivals under the BOLERO program alone the Transportation Sub-committee foresaw a need for 400 additional freight engines, and 50 shunting engines to operate on sidings at U.S. depots. In June the subcommittee requested that the United States meet these requirements,43 and orders were subsequently placed for 400 freight engines (2–8-0 type) and 15 shunting engines for early delivery to the United Kingdom. Measures were also taken in Britain to improve the rail lines of communications by providing “war-flat” and “war-well” cars to facilitate the handling of American tanks and other awkward loads on the British railways.44 In general, British rolling stock was small by American standards, the average “wagon” having only about one-sixth the capacity of freight cars on the American roads.

Four major types of accommodations were to be found or prepared for the BOLERO forces: personnel quarters, depot and shop space, hospitals, and airfields. Personnel accommodations and depot space were not immediately serious problems. Plans were made for the gradual removal of British troops from the Southern

Command area, to be completed by mid-December, and the housing of U.S. forces thus entailed only a minimum of new construction at first. Arrangements were already initiated in July 1942 to prepare for approximately 770,000 of the total force of 845,000 which was expected to arrive by 1 April 1943. Except for forces in Northern Ireland and air force accommodations to be arranged by the Air Ministry in eastern England, the great bulk of the American forces were to occupy installations in the Southern Command area, with a few going into southern Wales. The policy was early established that American troops would not be billeted in British homes except in emergency. Combat units were to be organized into divisional areas of 25,000 each and corps areas of 15,000, and service of supply troops were to be accommodated in depots, ports, and other major installations along the lines of communications. By July, four corps areas and fifteen divisional areas were already mapped out, and in some cases the specific locations of higher headquarters were determined. In general, availability of both signal communications and accommodations governed the location of headquarters. With these considerations in mind General Wootten in the First Key Plan of May had made a tentative selection of sites for several corps headquarters, had concluded that the SOS headquarters should be established at Cheltenham, and had chosen Clifton College, Bristol, as the most suitable location for an army headquarters. Both the army and SOS locations were eventually utilized as recommended.

ETOUSA had estimated that approximately 15,000,000 square feet of covered storage would be required, including 1,228,760 square feet of workshop space. Approximately half of this requirement already existed, and a program was immediately outlined for the expansion of existing facilities and for new construction. But it was estimated that space would have to be turned over to the Americans at a minimum rate of one and two-thirds million feet per month, and very little new construction was expected to become available before January 1943. There was likely to be an interim period in November and December 1942 before new construction became available, when there would be a serious deficiency of covered storage accommodation. To overcome this threatened deficit the planners concluded that additional space would simply have to be found and requisitioned in the Southern Command.45 U.S. forces also needed facilities for the storage of 245,000 tons of ammunition. This requirement the British also expected to meet by turning over certain existing depots from which they would evacuate their ammunition, and by expansion and new construction. In the case of currently occupied depots the final clearance of ammunition was to be phased with the evacuation of British troops, and Americans were to replace British depot personnel in easy stages so that the British could initiate the Americans in the operation of the depots.

The provision of adequate hospitalization called for a larger program of new construction than did either personnel or depot accommodations. It proved one of the more troublesome of the BOLERO problems, and the construction program repeatedly fell behind schedule. Hospital requirements had to be calculated in two phases. In the pre-ROUNDUP or build-up phase provision had to be made for the

normal incidence of sickness and would have to keep pace with new arrivals. In the period of actual operations hospitalization was required for casualties as well as normal illness. The number of beds required in the build-up period was based on a scale of 3 percent of the total force, with an additional allowance for colored troops owing to their higher rate of illness, and an additional provision for the hospitalization of air force casualties. On this basis it was figured that the BOLERO force would need 40,240 beds. Requirements in the ROUNDUP period were estimated on a scale of 10 percent of the total force engaged plus the accepted rate for sickness of forces remaining in the United Kingdom. On this basis an additional 50,570 beds were needed, or a total of 90,810 beds for the BOLERO force after operations began. Before publication of the First Key Plan, negotiations with the British for the acquisition of hospitals was conducted on an informal basis by the theater chief surgeon. By May 1942 Colonel Hawley by personal arrangements had procured from the War Office and the Ministry of Health five hospitals with a capacity of some 2,200 beds.46 Arrangements were also made in May for the transfer to the Americans of certain British military hospitals, and in addition several hospitals constructed under the Emergency Medical Service program. The latter had been undertaken in preparation for the worst horrors of the Nazi air blitz. Thanks to the victory over the Luftwaffe not all the emergency hospitals were needed, and several were now offered to the U.S. forces.47

The hospital requirement, unlike that for personnel and depot accommodations, could be met only in small part by the transfer of existing facilities. In the buildup period much of the requirement for hospital beds had to be met by new construction. During May the group with which the chief surgeon had been meeting was formally constituted as the Medical Services Sub-Committee of the BOLERO Combined Committee, and by the end of the month the subcommittee had determined in general the methods by which U.S. hospital requirements would be met. Most of the new construction was to take the form of hospitals with capacities of 750 beds, and a few of 1,000 beds. As a rough guide it had been accepted that one 750-bed hospital should be sited in each divisional area of about 25,000 men. By the time the Second Edition of the Key Plan was issued in July, orders had already been given for the construction of two 1,000-bed Nissen hut hospitals and eleven 750-bed Nissen hospitals, and for the expansion and transfer of certain British military hospitals. Reconnaissance was under way for sites for nine more 750-bed hospitals, and British authorities hoped to obtain approval for a total of thirty-five of this type of installation by mid-August so that construction could begin in the summer months.

To ease the great strain on U.K. resources, the BOLERO planners hoped to meet the additional requirements of the

General Hawley, Chief Surgeon, ETOUSA. (Photograph taken in 1945.)

second phase or ROUNDUP period with a minimum of new construction. The Deputy Quartermaster General estimated that the 54,000-bed program, if provided by new construction, would cost about $40,000,000, which represented one fifth of the entire U.K. construction program in terms of labor and materials. A proposal was therefore made to use hutted camps, barracks, and requisitioned buildings to fill the need, any deficiency to be made up in the form of tented hospitals. Colonel Hawley objected strongly to this feature of the First Key Plan, insisting that neither hutted nor tented camps would be suitable. Faced with a desperate shortage of labor and materials, however, there was little choice but to adopt the basic idea behind the proposal. Before publication of the July plan, agreement was reached on the use of two types of military camps—the militia camp and the conversion camp—which were to be converted to hospitals after the departure of units for the cross-Channel operation. The militia camps were already in existence and, with the addition of operating rooms, clinics, and laboratories, could be rapidly converted when the troops moved out. Representatives of ETOUSA proceeded to reconnoiter all existing camps and barracks with a view to conversion after ROUNDUP was launched, and found a good number of them suitable for this purpose. It was broadly estimated that 25,000 beds could be provided in this way. The conversion camp was essentially the same type of installation—that is, an army barracks—but was not yet built, and could therefore be designed with the express intention of conversion after D Day by certain additions. Ten of the 1,250-man camps being built in southern England accordingly were laid out to make them readily convertible to hospitals of 750 beds each, which would provide an additional 7,500 beds. A total of some 32,500 beds was to be provided by conversions after D Day. To make up the remaining deficit of 18,000 beds the BOLERO planners had to project new construction. In July plans were under way to provide 10,000 of these beds by building ten 1,000-bed Nissen hospitals.48

Financing the above construction program was another of the earliest hurdles to be surmounted, and the London Committee pressed for quick approval of a block grant of £50,000,000 ($200,000,000), well aware that such an estimate could only be tentative at the time. It is of interest to

record, however, that the construction program eventually was carried out at almost precisely that cost.49

The requirements described above were the responsibility of the War Office and were outlined in the Key Plan. Independent of this program, and involving more than twice as great an expenditure of funds, was that undertaken by the Air Ministry to provide accommodations for the bulk of the U.S. air forces and the airfields they required. Air force plans underwent several revisions in the summer of 1942. Originally calling for only 23 airfields and personnel accommodations for 36,300, the program was momentarily expanded in May to 153 airfields in addition to workshop and depot facilities. In July the air force program achieved relative stability with stated requirements of 98 airfields, 4,000,000 square feet of storage space, 3 repair depots, 26 headquarters installations, and personnel accommodations for 240,000.50

By far the largest single task faced by the BOLERO planners was that of construction. Although the U.S. forces were to acquire many of the facilities they needed by taking over British installations, a substantial program of new construction could not be avoided. Because of the ever-worsening shortage of labor it was impossible for British civil agencies to carry the program to completion unaided. Foreseeing the difficulty the BOLERO planners specified that the military services of both Britain and the United States would assist the British works agencies. Construction was to be carried out by both British military labor or civil contract under the supervision of the Royal Engineer Works Services Staff, through the agency of the Ministry of Works and Planning, and by U.S. engineer troops in cooperation with the Royal Engineers.51

While the provision of accommodations was undoubtedly the foremost preoccupation and worry of the BOLERO planners, the first Key Plans of May and July 1942 were remarkably comprehensive in their anticipation of other problems attending the reception of American forces. The BOLERO planners foresaw that U.S. troops, coming into a strange land, would be “as ignorant of our institutions and way of life as the people among whom they will be living are of all things American,” and recognized that one of their most urgent tasks was “to educate each side so that both host and guest may be conditioned to each other.”52 They also foresaw that U.S. forces initially would be unavoidably dependent on the British for many services, and the Deputy Quartermaster General went to great lengths to insure that the arrival of American troops would be as free of discomfort as possible. Reception parties were to be formed to meet new arrivals and to minister to all their immediate needs, including such items as hot meals, canteen supplies, transportation, training in the use of British mess equipment, and all the normal barracks services. Key British personnel were to remain in existing

depots, wherever possible, for necessary operation, and British workshops were to be handed over as going concerns. British Navy Army Air Force Institute (NAAFI) workers were to continue to run existing canteens in accommodations occupied by U.S. troops until American post exchanges were in a position to take over. In short, arrangements were made to provide all requirements for daily maintenance, including rations, water, light, fuel, cooking facilities, hospitalization, and dental care, and, to include a more somber aspect, even cemetery space. The guiding principle was to give all possible aid to American units at the outset and to train them so that they would as soon as possible assume full responsibility for their own maintenance.53

The BOLERO planners envisaged a gradual relinquishment by the British of military responsibilities and activities in the Southern Command area. On the operational side it was specified that the existing chain of command and its parallel operational administrative organization would remain in being until the immediate threat of a German invasion had receded, and until American forces were in a position to assume operational responsibility. On the administrative side the British command was to pass through two phases: the planning and constructional phase, which included the reception of increasing numbers of U.S. troops and responsibility for all aspects of their daily maintenance; and a final phase in which operational command had passed to the Americans, and in which the British would retain responsibility for only residual functions toward American troops and the control and maintenance of the existing Home Guard organization and a small number of British troops.

The implementation of the Key Plans required the closest possible coordination between U.S. and British agencies. U.S. staffs had to confirm plans for the locations of division and corps areas, and specify breakdown of storage and workshop requirements; the British Southern Command, in collaboration with U.S. officials, had to allocate space in accordance with American needs, prepare projects for construction, and select sites for hospitals. British administrative staffs were therefore to be strengthened in the planning and constructional phase (the next several months), and the Key Plans provided for an enlarged machinery of liaison between the U.S. and British forces. In addition to the liaison between the Deputy Quartermaster General and ETOUSA, a liaison officer was to be appointed from the former’s staff to visit SOS headquarters each day. U.S. Army liaison officers were to be attached to War Office branches as soon as more officers were available for such duty. In the meantime the War Office attached officers to Headquarters, SOS. At the next lower level a Q (Liaison) branch was established at Southern Command headquarters, eight U.S. officers were attached to the staff of Southern Command, and U.S. officers were also to be attached to the headquarters of the British districts (subdivisions of Southern Command.)54

To handle the tremendous administrative arrangements entailed by the buildup in the United Kingdom and to ensure that the preparations visualized in the Key Plan could be made effective, the London Combined Committee felt it

imperative that U.S. service units should arrive in correct proportions ahead of combat formations. U.S. units were needed not only to assist in the construction or expansion of installations and accommodations, but also to receive and build up maintenance and reserve supplies and equipment, to operate depots, and to provide local antiaircraft protection for the main depots and installations.55 The BOLERO planners also hoped that every effort would be made in the United States to dispatch units in accordance with the priority lists, but there were difficulties in the way. Bulk sailing figures were not likely to be known until shortly before convoys left the United States, and the breakdown of these bulk figures into individual units might not be available until sometime after the convoy had actually sailed. The lack of advance information on these sailings was regarded as a major difficulty in arranging quarters. By late June, however, the London Committee was satisfied that sufficient accommodations were being made available in bulk, and reception arrangements could be made at fairly short notice for the assignments of specific units to specific accommodations once the units were identified.56 U.S. forces in the United Kingdom at the end of June had a strength of 54,845. At the end of July the BOLERO build-up had not yet achieved any momentum. Shipments were still proceeding haltingly and U.S. forces in the United Kingdom at the end of the month numbered only 81,273.

As indicated earlier, the BOLERO plan was an inseparable part of the concept of a cross-Channel invasion. The Key Plans pointed toward such an operation in the spring of 1943, and assumed that the build-up of U.S. forces in the United Kingdom would be carried out with the greatest possible speed. Concurrent with the BOLERO preparations planning had also been initiated on both the operational and logistical aspects of ROUNDUP. The first meeting of the ROUNDUP administrative officers took place within a few days of the organization of the BOLERO Combined Committee, early in May. In the absence of a firm operational plan much of the logistical planning was at first highly hypothetical. Nevertheless, in mid-June the ROUNDUP administrative planners issued the first comprehensive appreciation of administrative problems in connection with major operations on the Continent, dealing with such matters as maintenance over beaches, the condition of continental ports, and inland transportation. The deliberations of the first two months were carried on with almost no representation from the U.S. Services of Supply, for the SOS was then in its earliest stages of organization. Both General Eisenhower and General Lee appreciated the need for coordination of ROUNDUP logistical planning with BOLERO, particularly with regard to procurement planning, and early in July took steps to have SOS officers placed on the ROUNDUP Administrative Planning Staff so that they could participate in the decisions which vitally affected their own planning. The work of the staff by this time had been divided among forty committees which had been formed to study the many administrative aspects of a cross-Channel operation.57 Significant preliminary steps had thus been taken by mid-July to prepare for a continental invasion.

The SOS Organizes, June–July 1942

At the height of the U.S. build-up in the United Kingdom, the American uniform was to be evident in every corner of the land, American ammunition and other supplies and equipment were to be stacked along every road, and American troops were to occupy more than 100,000 buildings, either newly built or requisitioned, and ranging from small Nissen huts and cottages to sprawling hangars, workshops, and assembly plants, in more than 1,100 cities and villages.

There was little visible evidence in June 1942 to portend the future scale of American activity in the United Kingdom. At the time the European theater was activated there were fewer than 35,000 American troops in the British Isles, most of them ground force units assigned to the V Corps in Northern Ireland. In England the first stirrings of American activity centered around the small air force contingent and in the theater headquarters in London. There were at this time only about 2,000 air force troops in England, hardly more than an advance echelon of the VIII Bomber Command. This small force was in the process of taking over the first airfields in the Huntingdon area and preparing to utilize the first big depot and repair installation at Burtonwood. Londoners were of course already familiar with the sight of Americans in Grosvenor Square, and the U.S. headquarters was to grow rapidly after the formation of ETOUSA.

As the governing metropolis of the United Kingdom and the seat of the War Office, London naturally became a center of American activity. That this activity should center about Grosvenor Square arose primarily from the fact that the work of the Special Observers had brought them near the American Embassy and the military attaché with whom they worked closely. Situated in the heart of Mayfair, Grosvenor Square was one of the exclusive residential areas in London. Surrounding it were the multistoried town houses and luxury flats which had provided the setting for the dinners and balls of the London social season. In the center was a private park of hedges and tall trees, once enclosed by an iron fence which had since disappeared into the scrap heap of war. From behind the dense shrubbery there now arose each evening a barrage balloon which swayed gently back and forth in the black of the London night.

Most of the modern buildings in Grosvenor Square were untouched by the blitz, but many were vacant, their former occupants having moved to the country. Beginning with the lease of No. 18—20 to SPOBS in May 1941, more and more of the apartments were taken over by the Americans. Stripped of their furnishings they quickly lost their glitter and acquired the utilitarian appearance of an army installation. Grosvenor Square was soon to be transformed into a bit of America, and the good humor with which Londoners received the increasing evidence of American “occupation” was expressed in the parody of a popular song: “An Englishman Spoke in Grosvenor Square.”

The first housekeeping units had arrived in London in March, a dispensary was opened, and the first enlisted billet was established at the old Hotel Splendide at 100 Piccadilly. Aside from this halting expansion of the new headquarters and

the beginnings of activity at a few airfields, there were as yet no operating services and no depots prepared to receive large shipments of either cargo or troop units. Until April 1942 there was not even a single army storage point in London. The scale of supply operations in the London area is illustrated by the fact that such supplies as were required in the headquarters were received and handled in a room on the fourth floor of No. 20 Grosvenor. That month a small warehouse was opened in the former showrooms of the Austin Motor Company on Oxford Street, and before long it was necessary to turn over all requisitions to a new depot in the East End. In the absence of U.S. shipments to fill immediate needs, meanwhile, there was a great scramble to obtain supplies and services in the British market, and considerable confusion was to result from the initial lack of reciprocal aid policy on such local procurement.

The gigantic task of organizing the Services of Supply was undertaken by General Lee upon his arrival in England late in May 1942. There were three major tasks to be carried out in fulfilling the mission of the SOS: organizing the reception of troops and cargo in the port areas, establishing a depot system for the storage and distribution of supplies, and initiating the construction program, particularly of airfields. Transforming the SOS into an operating organization, however, presented innumerable problems which first required solution.

Within twenty-four hours of his arrival in the United Kingdom, General Lee was busily engaged in a series of conferences, first with General Chaney, which led to a definition of the responsibilities and authority of the SOS (discussed in Chapter I), and then with members of the BOLERO Committee at Norfolk House, London, where he learned of the plans British officers had already made for the accommodation of the projected American force. During the next several weeks General Lee spent much of his time inspecting ports, depots, and other accommodations offered by the British. On the first of these reconnaissance trips he was accompanied by General Somervell, Brig. Gen. Charles P. Gross, the Chief of Transportation, War Department SOS, and Brig. Gen. LeRoy Lutes, Chief of Operations of the SOS in the War Department, who had followed Lee to England late in May. The special train of General Sir Bernard Paget, commander of British Home Forces, was put at the disposal of the party to tour port installations at Avonmouth, Barry, Liverpool, Manchester, Glasgow, and Gourock. On the basis of the survey, General Somervell reported to General Marshall his opinion that administration and supply arrangements for the reception and accommodation of American troops could be worked out satisfactorily, although he recognized tremendous problems for the SOS, and foresaw particular difficulties in rail transportation and airfield construction. General Somervell at this time stressed the importance of the early completion of operational plans so that supply and administrative planning could get under way. This was to become a familiar and oft-repeated request from the Services of Supply.58 General Lee later took members of his own staff on a reconnaissance of possible port and depot areas in southern England. including Bristol, Plymouth, Exeter, Taunton, Warminster, Thatcham, and Salisbury, all of which later became

key installations in the SOS network of facilities.

Meanwhile General Lee also made progress in the organization of the SOS staff which was announced at the end of June. It included Brig. Gen. Thomas B. Larkin as chief of staff, Lt. Col. Ewart G. Plank as deputy chief of staff, Col. Murray M. Montgomery as G-1, Col. Gustav B. Guenther as G-2, Col. Walter G. Layman as G-3, Col. Paul T. Baker as G-4, Lt. Col. Orlando C. Mood as Chief, Requirements Branch, and Col. Douglas C. MacKeachie as Chief, Procurement Branch.

The services were at first divided into operating and administrative, the former including the normal supply services under the supervision of the G-4, the latter the more purely administrative services under the Chief of Administrative Services. The incumbents of the operating services were the following: Col. Everett S. Hughes, Chief Ordnance Officer; Brig. Gen. Robert M. Littlejohn, Chief Quartermaster; Brig. Gen. William S. Rumbough, Chief Signal Officer; Brig. Gen. Donald A. Davison, Chief Engineer; Col. Edward Montgomery, Chief of Chemical Warfare Service; Col. Paul R. Hawley, Chief Surgeon; Col. Charles O. Thrasher, Chief, General Depot Service; Col. Frank S. Ross, Chief, Transportation Service. Brig. Gen. Claude M. Thiele was named Chief of Administrative Services, which included the following officers: Col. Roscoe C. Batson, Inspector General; Lt. Col. William G. Stephenson, Headquarters Commandant; Col. Alexander M. Weyand, Provost Marshal; Col. Adam Richmond, Judge Advocate; Col. Victor V. Taylor, Adjutant General; Col. Nicholas H. Cobbs, Chief Finance Officer; Col. James L. Blakeney, Senior Chaplain; Lt. Col. George E. Ramey, Chief of Special Services; Col. Edmund M. Barnum, Chief of Army Exchange Service. In addition, Col. Ray A. Dunn was named Air Force Liaison Officer, and Col. Clarence E. Brand was designated President of the Claims Commission, both on the SOS staff.

This organization within the SOS reflected very closely the organization of the SOS in the War Department, the memorandum outlining the organization of the administrative services following virtually word for word a similar memorandum issued by the SOS in the zone of interior. Within two months, however, several changes were announced and no further mention was made of the division into operating and administrative services. The general division of function continued, with the supply or operating services coming under the supervision of the G-4, and the administrative services passing to the province of the G-1, who later came to be known as the Chief of Administration. In general, the operating services included those whose chiefs were also members of the theater special staff and thus served in a dual capacity, maintaining senior representatives at Headquarters, ETOUSA. The administrative services were those in which counterparts were named at Headquarters, ETOUSA, and in which the division of authority became very troublesome. Even those staff sections which General Eisenhower had decreed should be placed under ETOUSA—that of the provost marshal for example—were split when the SOS moved to Cheltenham. ETOUSA and SOS each established its own adjutant general, inspector general, provost marshal, and other special staff officers. The inevitable result was an overlapping of function and a conflict over jurisdiction.

Chart 3: Organization of the Services of Supply, ETOUSA, 19 August 1942

(Chart 3) In varying degrees this tendency also carried over into the supply services, where the senior representatives at theater headquarters were inclined to develop separate sections and encroach on the functions of the SOS.

Following the organizational pattern of the War Department SOS, the newly founded SOS also included a General Depot Service as one of the operating agencies. Colonel Thrasher was named as its first chief, and the service was announced as an ETOUSA special staff section operating under the SOS. Shortly thereafter, however, again in line with similar War Department action, the functions of the General Depot Service were turned over to the chief quartermaster. The operation of the depots was eventually shared by the chiefs of services and the base sections which were soon to be formed. The Army Exchange Service, likewise established as a special staff section of ETOUSA and operated by the SOS, also ceased to be a special staff section and was placed under the chief quartermaster.

From the very beginning it was established policy in ETOUSA that the United States would purchase as many of its supplies as possible in the United Kingdom in order to save shipping space. Local procurement was therefore destined to be an important function, and to handle such matters a General Purchasing Board and a Board of Contracts and Adjustments were created in June, both of them headed by a General Purchasing Agent. Colonel MacKeachie, former vice-president of the Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company and Director of Purchases for the War Production Board, had been brought to the United Kingdom by General Lee to fill this position.

Among the other agencies created during the summer of 1942 were a Claims Service, the Area Petroleum Board, and an agency to operate training centers and officer candidate schools. ETOUSA had stipulated that the SOS would be responsible for the “adjudication and settlement of all claims and administration of the United States Claims Commission” for the theater. Here still another facet of the ever-present problem on the division of authority was to be revealed. The fact that the U.S. Congress had provided that claims be settled by a commission appointed by the Secretary of War complicated matters. Such a claims commission had been appointed directly by the War Department and was already working in close cooperation with British authorities. The SOS meanwhile had organized a Claims Service to investigate claims and report on them to the Claims Commission, which alone had the authority to settle them. General Lee hoped to resolve this division by consolidating the two agencies and bringing them under the SOS. Instead a circular was published strictly delineating their respective jurisdictions and authority, placing the operation of the investigating agencies under the Claims Service of the SOS, and the actual settlement of claims under the Claims Commission.

Another field in which special or unusual arrangements were necessary was the handling of petroleum products, or POL.59 While the procurement, storage, and issue of fuel and oil was a quartermaster responsibility, there was need for an over-all agency to coordinate the needs of the Army, Navy, and Air Forces in the