Chapter 3: The Build-up in Stride, 1943

BOLERO in Limbo, January–April 1943

January 1943 brought renewed hope that the movement of U.S. troops to the United Kingdom would be resumed. The scale of the build-up obviously depended on a firm decision on future strategy. Late in November 1942 President Roosevelt, encouraged by the initial success of the TORCH operation, suggested to Prime Minister Churchill the desirability of an early decision, and a few days later asked General Marshall for estimates on the number of men that could be shipped to both the United Kingdom and North Africa in the next four months.1

OPD made a study of shipping capabilities and reported that 150,000 troops could be shipped to England by mid-April, assuming that there was no further augmentation of the North African force after the middle of January.2 The acceleration of movements to the United Kingdom depended largely on the demands on shipping from North Africa and on the availability of adequate escorts. Demands from North Africa, coupled with a continuing shortage of shipping, had caused a drastic amendment of earlier plans for a build-up of the 427,000-man force in the United Kingdom by the spring of 1943. Current plans called for shipment of only 32,000 men in the next four months.3

Future Allied strategy to follow TORCH had remained undecided throughout the fall of 1942, and the War Department was not inclined to favor a large build-up in the United Kingdom even if shipping were available. In January 1943 the Allied leaders met at Casablanca to resolve this uncertainty. By that time the world outlook was considerably brighter than it had been six months before. The Red armies had frustrated the first German attempt to break through in the Caucasus and were now on the offensive; Rommel had been beaten in North Africa and the Allied vise was closing on the German forces in Tunisia; and the land and sea actions at Guadalcanal had checked Japanese expansion in the South Pacific. But whatever optimism was inspired by the more favorable situation on these fronts was sobered by the gloomy aspect presented by the war on the seas. In spite of the rising production figures of the American shipyards, Allied shipping losses continued to exceed replacements throughout 1942. In the first months of 1943 the U-boat attacks reached their full fury. The shortage of shipping consequently

remained the severest stricture to Allied plans and prevented full utilization of the Allied war potential.

The Casablanca decisions recognized the Atlantic as one of the most important battlefields of the war by giving the fight against the submarine menace the first charge against United Nations resources. In view of the competing demands of the North African area and the Russian aid program on the limited shipping resources it was hopeless to think of a full-scale cross-Channel operation in 1943. The Allied leaders decided instead to continue the offensive in the Mediterranean. The invasion of Sicily was to be the major effort of 1943. Regarding operations from the United Kingdom, the Allied leaders gave impetus to air operations by assigning high priority to the inauguration of a combined bomber offensive, but their decisions fell somewhat short of a definitive commitment on ROUNDUP. Nevertheless, two decisions were made which confirmed the basic assumption that there would still be a cross-Channel operation. It was agreed to establish a combined command and planning staff in the United Kingdom to plan for cross-Channel raids and for a possible return to the Continent under varying conditions in 1943 or 1944, and a corollary agreement was reached to reinstate the BOLERO build-up. Both the Prime Minister and the President were anxious to build up forces in the United Kingdom, and President Roosevelt urged that a definite build-up schedule be prepared so that the potential effort of Allied forces in the United Kingdom could be estimated at any time to take advantage of any sign of German weakness.4 General Somervell calculated that shipping capabilities would permit only small movements in the first six months, and the Prime Minister expressed disappointment that only four divisions would arrive by mid-August. But the shortage of cargo shipping made it impracticable to schedule a more rapid troop build-up at first, since, as it was pointed out, there was no point in sending units without their equipment.5 After the middle of the year it was estimated that the rate of shipping could be vastly increased, and that a total of 938,000 troops, including fifteen to nineteen divisions, could be dispatched to the United Kingdom by the end of 1943. Added to the present strength in Britain, this would result in a build-up of 1,118,000 men.6

While the Casablanca Conference did not give a definite pledge regarding a cross-Channel attack, its decision to resume the BOLERO build-up on such a scale reinforced the belief that ROUNDUP eventually would take place. he estimate that nearly a million men and their equipment could be transported to the United Kingdom in the next eleven months was highly optimistic in view of the chronic shortage of shipping and the continued demands on Allied resources from the Mediterranean area and the USSR. Nevertheless, the Casablanca decision on BOLERO was welcome news to those in the United Kingdom who once before had begun preparations for such a build-up and had then seen the ETO experience a sudden bloodletting and loss of priority.

Theater officials were fully aware of the task which a revived program would present. To move nearly a million men with their supplies would mean the reception of

about 150 ships per month in the last quarter of the year, with all the attendant problems of discharge, inland transportation, storage, and construction. General Lee had attended the conference in Casablanca, and even before leaving North Africa took the first steps to get planning under way for the task which he knew the SOS would have to shoulder. On 28 January he wrote informally to Maj. Gen. Wilhelm D. Styer, chief of staff of the War Department SOS, giving him advance notice of some of the requests for service troops which he expected to make shortly through official channels.7 A few days later he informed General Littlejohn, who was acting for Lee in the latter’s absence, of the decision to resume the build-up and instructed him to study the implications with Lee’s British opposite, Gen. T. S. Riddell-Webster, the Quartermaster General.8 Before departing for North Africa General Lee had instructed his staff to draw up two supply and accommodation plans, one based on the current troop basis of 427,000, and another for the then hypothetical force of a million men.9

The renewed confidence which the SOS now felt for the build-up of the ETO was expressed on 5 February in the announcement that planning for the movement of a large force to the United Kingdom would no longer be considered as a staff school problem, but would be worked out as a firm program as expeditiously as possible. Complete plans on personnel, storage and housing, construction, transportation, and supply were to be developed, with the G-4 coordinating all plans.10 The reinstatement of BOLERO also brought the BOLERO Combined Committee of London together for the first time in several months.11

The year 1943 found the ETOUSA and SOS staffs considerably better prepared to plan for the reception and accommodation of U.S. forces than they had been six months earlier. Their experience in the summer of 1942 had made them more aware than ever of one essential prerequisite to such an undertaking—the advance arrival of sufficient service troops to prepare the necessary accommodations and facilities. This was even more imperative in 1943 than it had been earlier because of the unavailability of British labor. British officials had pointed out at the Casablanca Conference that the proposed shipments (150 ships per month at the peak) could be handled only if U.S. dock labor and locomotives were forthcoming.12 There was also a shortage of depot space. The British had stopped construction because of their own manpower shortages and because of the reduced requirements for the smaller 427,000-man troop basis. They therefore urged that U.S. service personnel be included in the earliest arrivals.13 It was precisely this problem that General Lee had in mind when he wrote to General Styer from North Africa late in January. He asked for 30 port battalions, 30 engineer regiments, 15 quartermaster service battalions, and about 30 depot companies of various categories. All these would be necessary in order to discharge the 120–150 ships per month, construct the needed depots, properly store and issue equipment and supplies, and carry out

the airfield construction program. He pointed out that the U.S. forces had been caught short of service troops in the summer of 1942 and had got by only by the emergency use of British labor and even combat units. This remedy could not be tried again. U.S. forces must become more self-sufficient and the SOS portion of the revived BOLERO program must be larger. Lee punctuated his argument with a lesson from history, quoting General Pershing who in 1918 had made a similar appeal for advance shipments of SOS troops for the necessary construction projects. With the experience of August and September 1942 fresh in his memory, General Lee noted that the SOS had learned the hard way in the past seven months, and he was determined that there should not be a repetition of the frantic efforts of the previous summer.14

These arguments were readily seconded by General Lee’s staff in the United Kingdom. General Littlejohn pointed out to the new theater commander that the support of the new program necessitated the expansion and acceleration of the SOS construction program and supply operations. For this purpose he urged General Andrews to ask for a stepped-up shipment of SOS troops. There was sufficient reason for such a plea at this time. The SOS was already a reduced and unbalanced force as a result of the losses to TORCH. The hospital and airdrome construction programs were seriously behind schedule.15 Finally, the British could not be expected to provide labor on the scale they had maintained in the summer of 1942, and it was predicted that they would insist that SOS troops arrive well in advance of combat units.16

After the Casablanca decision the SOS staff members in the United Kingdom had immediately been instructed to figure their troop needs, which were to be used in formulating a service troop basis for presentation to the theater commander. Ever conscious of the repeated admonitions from the War Department and theater headquarters to keep service troop demands to a minimum, the service chiefs felt a strong compulsion to offer the fullest possible justification for their stated requirements. They had two favorite and seemingly indisputable arguments. Almost without exception they were able to show that percentagewise they were asking for fewer troops than the SOS of the AEF in 1917–18. The SOS portion of the AEF on 11 November 1918 had been 33.1 percent. On the basis of a total build-up of 1,118,000 men by December 1943, they argued, the SOS should therefore have a troop basis of 370,000. The chief of engineers, for example, maintained that on the basis of the practice in World War I, in which 26.9 percent of the SOS consisted of engineer troops, the present SOS should have 99,500 engineer troops. He was asking for only 67,000. The service chiefs further reinforced their claims by painting out that the present war was making much heavier demands on the services of supply. There had been a great increase in mechanized transport, in air force supply, and in the fire power of weapons; there were new problems of handling enormous tonnages of gasoline and lubricants, and of constructing airfields. Furthermore, in the

war of 1917–18 the U.S. Army had operated in a friendly country where port and transportation facilities were already available. Operations in Europe would now require landing supplies over beaches and restoring ports and railways. Thus, World War I was not even a fair basis of comparison so far as service troop requirements were concerned.17

By mid-February General Littlejohn had assembled sufficient data on the needs of the various services to present the theater commander with a tentative troop basis calling for a total of 358,312 men. By far the largest components were those of the Corps of Engineers, the Quartermaster Corps, and the Medical and Ordnance Departments, accounting for more than two thirds of the total. In presenting the needs of the SOS to General Andrews, General Littlejohn noted that every practicable measure had been taken to reduce SOS needs, and he again reviewed the limited possibilities of utilizing British labor. If it became necessary to reduce the SOS troop basis further, he continued, army and corps service units should be brought to the theater and made available to the SOS. The need for service units was so urgent that he even recommended securing the required manpower by breaking up organizations in the United States. The SOS desired the highest possible shipping priority for its units and asked for a rapid build-up to a strength of 189,000 by the end of June. The most pressing need was for engineer construction units, and these were therefore given a priority second only to air force units for the bomber offensive.18 But the air units were to be followed by service troops to support the bomber offensive, and by additional service troops for the BOLERO program.

It was only a matter of days before the hopes for this program were dashed. On 19 February General Marshall wired the theater that the decision to resume the build-up was not firm, and that the schedules set up in September 1942 would be followed until a definite decision was reached.19 Three days later this bad news was confirmed by a cable from OPD notifying the theater that there were indications that shipping for the U.K. build-up would be “nothing for the months of March and April because of the urgency of the situation in another theater.” The “other theater” was North Africa, which continued to make unexpected demands on both troops and cargo. Immediately after the Casablanca Conference the War Department had been asked to prepare a special convoy with urgently needed vehicles and engineer and communications equipment. Only a few days later General Eisenhower asked for an additional 160,000 troops to arrive by June. These demands were superimposed on the requirements for the planned Sicilian operation and entailed a great increase in cargo shipments to the Mediterranean.20 The results for BOLERO were inescapable. Meeting these demands meant not only a drain on troops and matériel but the

diversion of the limited shipping resources. The battle of the Atlantic reached its height in these months, and the competing claims of Russian aid, the support of operations in the Mediterranean, and the British civil import program on shipping simply precluded an immediate implementation of the Casablanca decision on BOLERO

The inability to rebuild the U.K. forces as planned in January was a bitter pill for the planners in England. General Andrews thought it would do no harm as far as ground forces were concerned, since theater planners had not even been able to arrive at a practical plan upon which to set up a ground force troop basis. In fact, upon reflection, he thought there was one aspect of a slower build-up which might be a partial blessing. Because training areas and firing ranges were inadequate in the United Kingdom, it was preferable that American troops get as much training as possible in the United States. A delayed build-up would also allow the SOS to build a firmer foundation.21 But the setback in building a bomber force was a serious blow. Andrews noted that units needed between forty-five and sixty days to prepare themselves for combat after arriving in the theater, and it had been hoped that every available unit in the United States might be brought over early in the year to take advantage of the favorable summer months.22 Air force units in England were suffering from both combat losses and war weariness. Lacking replacements, some groups were reduced to a strength of 50 percent, and progressive attrition was seriously lowering morale among the crews that remained.23

Cancellation of the build-up had an unavoidable repercussion in the United Kingdom and cast a pall of uncertainty over all planning. General Andrews appreciated fully the desirability of proceeding with planning for cross-Channel operations. In anticipation of a Combined Chiefs directive, based on the agreement at Casablanca, he urged that joint planning should again be resumed, emphasized particularly the importance of having a firm troop basis and a schedule of arrivals, so that U.K. planners would know what they were dealing with, and underlined the necessity of arranging for production and procurement of vast quantities of equipment, a task which would require many months.24 In its never-ending attempts to get more specific commitments and precise data on which to base its own preparations, however, the SOS was again frustrated. The G-4 of the SOS submitted a list of questions to the G-4, ETOUSA, early in March concerning future operational plans, the over-all troop basis, and levels of supply. The ETOUSA supply officer was helpless to offer any specific information on the size, place, extent, and timing of future offensive operations. He could only reply that the Casablanca program evidently had not been discarded but only delayed, and added hopefully that directives were expected from the War Department which would “permit planning to proceed beyond the present stage of conjecture.”25

The SOS meanwhile continued to analyze its troop needs with a view toward paring its demands even further. Late in March it completed a troop basis and flow chart calling for approximately 320,000 service troops based on a total force of 1,100,000 men. In submitting it to the theater commander General Lee asserted that it was the result of an exhaustive study by the chiefs of services and represented the minimum requirements. The reduction of 40,000 in the troop basis was made possible largely by the decision to use certain service elements of both the ground and air forces for administrative purposes.26 At the same time the SOS continued to plead for shipments of service troops in advance of combat units, underlining this need in every communication with higher headquarters.

For the moment these plans were largely academic, for the shipping situation made it impossible to implement the Casablanca decision on the scale expected. In the first three months of 1943 only 16,000 of the projected shipment of 80,000 men were dispatched to the United Kingdom, and 13,000 of these had already left the United States at the time of the Casablanca Conference. The main effect of the diversions to North Africa was felt in February, March, and April, when the flow of troops to the United Kingdom averaged fewer than 1,600 per month.27 The effect on troop movements was most pronounced because troop shipping was even scarcer than cargo shipping at this time. But in cargo shipment the record was similar. In the same period the monthly cargo arrivals averaged only 35,000 long tons (84,000 measurement tons).28

At this rate the ETO was barely maintaining its strength after the losses to TORCH, to say nothing of mounting an air offensive. Worried by the almost complete neglect of the United Kingdom, General Andrews in his last weeks as theater commander pleaded with the War Department not to let the build-up die. If necessary BOLERO should be retarded, he maintained, but not halted. There should be a steady building up of American forces in Britain for an overseas operation in 1944. At the least it was important to maintain the impression that American troops were arriving in large numbers and to say and do nothing which would appear inconsistent with this conception. General Andrews felt that any appreciable slowing down of BOLERO might even compromise an operation in 1944, since preparations were already behind schedule.29 Fortunately the question of the build-up was soon to be resolved.

The Troop Build-up Is Resumed, May–December 1943

The uncertainty regarding the United Kingdom build-up was finally largely dispelled in May 1943, when Allied leaders met at the TRIDENT Conference in Washington. Plans for the defeat of the Axis Powers in Europe were embodied in three major TRIDENT decisions: to enlarge the U.S.-British bomber offensive from the United Kingdom; to exploit the projected Sicilian operation in a manner best

calculated to eliminate Italy from the war; and to establish forces and equipment in the United Kingdom for a cross-Channel operation with a target date of 1 May 1944.30

The resolution concerning a cross-Channel attack was not an unequivocal commitment, as it turned out, and Allied strategy was to be reargued within another few months. Nevertheless, the naming of a date and the designation of the size of such an operation made it the most definite commitment yet accepted for the attack which American planners had supported for the past year. The likelihood that the BOLERO build-up would now be carried out was strengthened by a definite allocation of resources: twenty-nine Allied divisions were to be made available in the United Kingdom for the operation in the spring of 1944; and there was to be no further diversion of resources to the Mediterranean. In fact, four U.S. and three British divisions in the Mediterranean area were to be held in readiness after 1 November for movement to the United Kingdom.31

By May 1943 an additional factor was enhancing prospects for the U.K. buildup. After the near-record shipping losses in March (768,000 tons from all causes),32 the battle of the Atlantic took a sudden turn for the better. Beginning in April, with the increasing use of long-range and carrier aircraft, and of improved detection devices and convoy practices, the Allies took a mounting toll of U-boats. And as shipping losses fell off, the increasing output of the shipyards was reflected in the net gains in available tonnage. This turn of events was undoubtedly one of the most heartening developments of the war, and soon made it possible to plan the logistic support for overseas operations with considerably more confidence and on a greatly magnified scale. Together with the freezing of resources in the Mediterranean, it promised to create a tremendous potential for the U.K. build-up.

The TRIDENT planners scheduled a build-up of 1,300,300 American soldiers in the United Kingdom by 1 May 1944. Of these, 393,200 were to be air force troops, and 907,100 were to be ground and service troops, including eighteen and one-half divisions. By 1 June 1944, the planners calculated, a force of 1,415,300 (twenty-one divisions) could be established in Britain.33 These figures did not necessarily constitute a troop basis, nor did they reflect actual shipping capabilities. It was noted that there were actually more divisions available than were scheduled for shipment, and the rate of build-up was based on what the British indicated could be processed through their ports, not on shipping capabilities. The balanced movement of troops and their cargo was actually limited by the quantity of cargo which could be accepted in the United Kingdom, the maximum practical limit being 150 shiploads per month except in absolute emergency. From this time on British port capacity was to be a despotic factor governing the build-up rate. Once more, therefore, the Combined Chiefs emphasized the necessity for the early arrival of port battalions to aid in the discharge of ships, and engineer construction units to complete the needed depots. The wisdom of such a policy could hardly be disputed, and at the close of the conference Headquarters, ETO, was notified that the shipment of service troops was to be given

a priority second only to the air force build-up.34

The ETOUSA planners welcomed the green light which the TRIDENT decisions constituted, although they had not been idle despite the failure to implement the earlier Casablanca decisions. In the early months of 1943 the SOS staff had continued to plan for the eventual flow of troops and cargo, and had assembled a mass of logistical data covering all aspects of the build-up, such as manpower, storage and housing, transportation, construction, and supply. This information was issued in what were known as Tentative Overall Plans which were kept up to date by repeated revision. To implement the TRIDENT decisions in the United States, the BOLERO Combined Committee in Washington was now reconstituted as the BOLERO-SICKLE Combined Committee, the word SICKLE applying to the air force build-up, which was now planned independently of the ground and service components. As before, the Combined Committee of Washington was set up as a subcommittee of the Combined Staff Planners (of the CCS) with the mission of coordinating the preparation and implementation of the BOLERO-SICKLE shipping program.35 Although the London Committee had never been formally disbanded, it had not met since February after the abortive revival of BOLERO. On 20 July it once more met under the chairmanship of Sir Findlater Stewart. Headquarters, ETOUSA, had made some new appointments to the committee and the entire group assembled at this time primarily to introduce the new members. Direct contacts had long since been established between appropriate American and British services and departments, and there was no longer any pressing need for regular meetings of the entire committee. The July meeting consequently proved to be the only formal session under the new program, although small ad hoc meetings and informal conferences were called from time to time, and the various specialized subcommittees continued to meet to solve particular problems.36

British and American officials in the United Kingdom had already taken cognizance of the reception and accommodation problem posed by the new program, and had recognized the necessity for bringing older plans up to date. But it had been impossible to publish a new BOLERO Key Plan earlier because of the tentative status of the troop basis.37 Early in July Headquarters, ETO, submitted to the War Office new build-up figures and data to be considered in the distribution of U.S. forces in the United Kingdom. These planning figures approximated the TRIDENT shipping schedule, indicating a build-up of 1,340,000 men by 1 May 1944. The War Office was asked to use this total to plan the maximum accommodations.38 On the basis of this figure the BOLERO Key Plan underwent its last major revision, the Fourth Edition being issued by the Deputy Quartermaster General on 12 July 1943. The British Southern Command had already anticipated the changes and had issued its own

plan for the U.S. Southern Base Section area two weeks earlier.39

During the summer of 1943 the ETOUSA, SOS, and Eighth Air Force staffs devoted a large portion of their time to the all-important problem of obtaining a definitive troop basis for the ETO. No single other problem was the subject of so many communications between the various headquarters and between ETOUSA and the War Department. Solving it was perhaps the most important initial task after the strategic decisions of the Combined Chiefs which assigned the theater its mission. Not only was it essential that the War Department determine the total allotment of troops to the theater. It was necessary to come to an agreement with the theater over the apportionment of this over-all allotment between the air, ground, and service forces to create a balanced force, and decide on the specific numbers of each of the hundreds of different types of units. In one of the first staff conferences held by the SOS to discuss the implications of the TRIDENT decisions it was pointed out that the over-all troop basis—air, ground, and service—together with the priorities for shipment, was a basic factor in the preparation of an accommodation, maintenance, supply, and construction plan, and therefore a necessary prerequisite to the revision of the BOLERO Key Plan.40

Had the ETOUSA planners awaited the approval of a firm troop basis, however, little progress would have been made in preparing for the build-up in 1943, for the troop basis continued to be a subject of negotiation with the War Department for several months to come. Fortunately, ETOUSA and SOS planners had begun calculating the theater’s requirements before the TRIDENT Conference, and on 1 May General Andrews had submitted to the War Department a list of the units, totaling 887,935 men, which he desired shipped to the theater by 31 December. It was admittedly only a partial list, but provided sufficient data to the War Department for the employment of shipping for the remainder of the year. A complete troop basis was hardly possible at the time, since an operational plan had not yet taken shape to determine the precise troop needs.41 ETOUSA later submitted new priority lists, and by the end of the month shipments were beginning to be made on the basis of the interim 888,000-man troop list and the theater’s latest priority requests.42

Submitting the partial troop list was one of General Andrews’ last acts as commanding general of the European Theater. On 3 May, barely three months after assuming command, he was killed in an airplane crash while on a tour of inspection in Iceland. General Andrews was an air force officer, and his loss was therefore particularly regrettable in view of the plans then being formulated for an intensified aerial offensive. Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers, commander of the Armored Force at Fort Knox, was appointed his successor and arrived in England on 9 May 1943.43 To him now fell the task of bringing to

fruition the long-drawn-out and detailed work on a definitive troop basis.

For the first time it was possible to develop the troop basis with somewhat more specific missions in mind. The air force troop basis was now formulated on the basis of the Combined Bomber Offensive, which was in the process of acceptance by the Combined Chiefs of Staff early in May. The ground force troop basis, while based on a still nebulous plan for a cross-Channel operation, was nevertheless firmly related to the plans which were now being formulated by the new Allied planning staff established in April in accordance with the decision made at Casablanca in January. Under the leadership of Lt. Gen. Frederick E. Morgan (British), who had been named Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (designate), or COSSAC, this group had taken the place of the old ROUNDUP planning staff and was already putting into shape an outline design for continental invasion.

The first of the troop bases to be developed in detail and submitted to the War Department was that of the air force. For this purpose General Arnold sent a special mission to the United Kingdom, headed by Maj. Gen. Follett Bradley, Air Inspector of the Army Air Forces, to study the personnel needs and organization of the Eighth Air Force and to prepare a troop basis adequate to the contemplated mission of the air force in the United Kingdom. General Bradley arrived in England on 5 May, at the very time that the command of the theater was changing hands. After three weeks of studies and conferences he submitted his plan to the War Department at the end of May, calling for an allocation of 485,843 men, including 113 groups, to be built up by June 1944. The proposal was approved by General Eaker, who had assisted in its preparation, and by General Devers, although with certain reservations. On the assumption that the VIII Bomber Command was to be built up at maximum speed and to its maximum strength for its new mission, the plan had been developed with little relationship to the theater’s other requirements. General Devers thought the air force troop basis was too large compared with those of the ground and service forces then under study in his headquarters, and he also opposed the speed of the build-up which the Bradley plan called for. He believed that the proposed build-up could be carried out only at the expense of SOS and ground troops, since there was not enough shipping to go around. He warned that the air could not operate without SOS support, and that the brunt of any reduction in movement schedules would therefore have to be borne by the ground forces.44

The War Department approved the Bradley plan as a basis for planning, but with important exceptions. In particular, it opposed certain organizational features of the plan and insisted on reductions in headquarters and service personnel, for which the plan had made a generous allocation of 190,000 men in a total of less than 500,000. Despite protests from the Eighth Air Force, a sizable reduction was eventually made in its troop basis. At the direction of the War Department a second group of officers went to England in October to make a new study of air force needs, and pared the allocation to 466,600. After a further review by the War Department, and the decision to

divert certain groups to the Mediterranean, the troop basis of the Eighth Air Force was finally established at 415,000, with a build-up of ninety-eight and a half groups to be achieved by June 1944.45

Meanwhile Headquarters, ETOUSA, and the SOS completed their studies of ground and service force needs, and the troop bases for these two components were submitted to the War Department in the month of July. On the 5th General Devers requested approval of a ground force troop basis of 635,552 (to include eighteen divisions), and on the 18th he submitted the SOS troop basis calling for 375,000 men. In both cases these figures represented only the “first phase” requirements—that is, the forces required to launch an operation on 1 May 1944 aimed at securing a lodgment on the Continent. General Devers carefully pointed out that additional units in all categories would have to augment this force in order to support continuing large-scale operations.46 Troop bases for the “second phase” were then being studied and were to be submitted within a few weeks.

As in the case of the Bradley plan, both ground and service force troop bases for the first phase came under careful scrutiny in the War Department. For the most part the ground force allocation was not seriously challenged, although questions were raised regarding the ratio of various types of troops.47 Most of the criticism was reserved for the SOS troop basis, just as the service troop allocations in the air force plan had also been subjected to the heaviest criticism. It was generally conceded that the supply and maintenance situation in the ETO before the actual start of operations was considerably different from that in a normal overseas theater. The construction program for camps, airdromes, and other installations, the receipt, storage, and issue of pre-shipped supplies and equipment, and other factors all tended to create a unique logistical problem. At the same time, the War Department staff noted, from the standpoint of economy it was not desirable to ship units merely to meet this abnormal situation if such units would not be needed when the peak load had passed at approximately D Day. As the SOS troop basis made its way through the War Department staff sections it was generally agreed that savings could be made. The G-3 specifically listed certain guard units, military police, and Ordnance and Transportation Corps units for elimination; and he cast a suspicious eye on certain other special units, the need for which was not considered to be critical, or whose functions could be performed by other units.

Among these were forestry companies, gas generating units, firefighting platoons, utility detachments, model maker detachments, bomb disposal companies, petroleum testing laboratories, museum and medical arts service detachments, radio broadcasting companies, and harbor craft service companies.48 The G-3 was emphatic in his assertion that nonessential units should not be approved for the ETO or any other theater. It was imperative, he noted, that combat and service units be required to perform, in addition to their normal duties, certain services for which they were not primarily organized or trained, for example, firefighting. The current manpower shortage made it extravagant in his opinion to provide service troops enough to meet peak loads which might occur only infrequently. The eight-hour day and the “book figures” for normal capabilities of service units simply had to be abandoned.49

The analysis of the ETOUSA troop basis was by the War Department’s own admission a highly theoretical matter, for Washington lacked detailed knowledge of operational plans and exact information on the type of operations to be undertaken. The War Department’s study was largely a statistical analysis, based on a comparison of the ETO’s requests with the allotment of various types of units in the over-all War Department troop basis, and on a comparison with a hypothetical thirty-division plan worked out in the War Department, supposedly with a cross-Channel operation in mind. There was great variance between the calculations made in the theater and in Washington, and the War Department was at a loss to make very many specific demands for reductions. On 25 August it returned the troop basis to the theater with the characteristic “approved for planning purposes,” but with the injunction to effect economies in the use of service troops. Most of its recommendations were of a general nature. The theater was instructed to reduce to a minimum the number of fixed logistical installations in the United Kingdom with the idea that certain of these installations would eventually be required on the Continent. As a temporary reinforcement of the SOS it was asked to utilize to the maximum the service units whose regular assignment was with the ground forces, and, if necessary, even to employ combat units where training would not suffer too seriously. Before making more specific recommendations the War Department preferred to await the development of a more detailed operational plan and also asked to see the theater’s administrative plan.50

The return of the troop basis to the theater was followed in a few days by letters from both Brig. Gen. John E. Hull, the acting chief of OPD, and General Handy, the Deputy Chief of Staff, re-emphasizing the serious manpower situation in the United States. The shortage of men was placing a definite limitation on the size of the Army, with the result that the War Department had been charged with sifting all theater troop demands. It therefore requested additional information on which to base its consideration of ETOUSA’s troop needs, and again asked

the theater specifically to submit an outline administrative plan for the cross-Channel operation.51

To these comments and injunctions ETOUSA could only reply that it had already taken into consideration precisely those economy measures which the War Department had listed. Every effort had been made to keep to a minimum the number of fixed installations. The War Department, it noted, was apparently unaware of conditions in the United Kingdom, for the logistical setup there was far from optimum. The British had long since dispersed most installations because of the threat of air attack. These had been accepted for use by the Americans largely because the shortage of both labor and construction materials precluded extensive building of new and larger depots. The rail distribution system and the limited capacity of the highways also favored more numerous, smaller, and dispersed installations, all of which tended to increase the need for service units. ETOUSA further assured the War Department that it had already counted on the use of service units of the ground forces wherever possible in formulating the SOS troop basis. ETOUSA admitted certain minor changes in its troop lists, but for the most part justified its requests. The submission of an administrative plan it regarded as impractical at that time.52

The problem of striking an adequate and at the same time economical balance between service and combat troops was a perennial one. Since the War Department’s 1942 troop basis had not provided adequate service troop units, it had been necessary to carry out piecemeal activations in order to meet the requirements for overseas operations. In 1943 the number of available troop units continued to fall short of the demands of the overseas commanders. The desire to place the largest possible number of combat units, both air and ground, in the field inevitably resulted in subjecting the service troop demands to the closest scrutiny. Increasingly conscious of the limited manpower resources, the War Department General Staff in November 1942 not only reduced the total number of divisions in the over-all troop basis, with corresponding cuts in the service units organic to the combat elements, but also took steps to reduce the over-all ratio of service to combat elements. There was no formula for economy which could fit all the varied circumstances of a global war, and it was difficult at best to prove that logistical support would be jeopardized by eliminating one or two depot companies or port battalions. In general the view persisted in the War Department that the ratio of service to combat troops was excessive, and it had become normal to regard the demands of the service forces with a certain suspicion, at times with some justification.53 Pressed by the manpower situation in the United States the War Department apparently felt doubly obliged to question the theater’s demands.

It should be noted that the original SOS troop demands had already suffered a very sizable cut. The chiefs of services had originally submitted to the theater

commander a list of requirements totaling 490,000 men, each chief maintaining that he had asked for only the minimum number considered essential to do an efficient job. General Devers had taken issue with these demands, and had given a command decision limiting the total service troop basis to 375,000 and assigning the various services specific percentages of this total. The service chiefs consequently had little choice but to recalculate their needs and bring them within the prescribed allotments. Reductions were naturally made where they involved the least risk. The number of hospital beds was reduced by refiguring casualty estimates. Requirements for port battalions were refigured on the assumption that greater use could be made of civilian labor on the Continent, and for railway units on the assumption that railways would not be restored as rapidly as previously planned. In this way 115,000 bodies were lopped off the original “minimum” estimates. The 375,000-man troop basis which General Devers eventually submitted to the War Department in July was based on an allocation of 25 percent of the over-all theater troop basis to the SOS.54 This was certainly not exorbitant considering World War I experience and the enlarged services which the SOS was expected to perform. Whether a force thus limited by fiat would prove adequate to support the ground and air elements remained to be seen. At any rate, the theater stood firm on its July troop basis for the SOS, and it was eventually accepted by the War Department without important changes. While the various component troop bases underwent minor alterations from time to time, by November the ETOUSA first-phase troop basis for 1 May 1944 had reached relative stability with the following composition:55

| Type | Number |

| Total | 1,418,000 |

| Services of Supply | 375,000 |

| Ground Forces | 626,000 |

| Air Forces | 417,000 |

In the meantime work had also progressed on the troop basis for the second phase, the terminal date for which at first was designated as June 1945 and later moved forward to 1 February 1945. On 5 August General Devers submitted the ground force requirements, totaling 1,436,444,56 and on 26 September the theater notified the War Department that its second phase service troop needs would total 730,247 men.57 Added to the air force total, which did not change since it was to achieve its maximum build-up by 1 May 1944, the troop basis for the second phase thus totaled approximately 2,583,000. The second phase figures represented the cumulative build-up to 1 February 1945 and therefore included the first phase totals. They represented the estimated needs for extended operations on the Continent after seizure of a lodgment area, and were prepared at this time primarily to serve as a guide to the War Department in its activation and training program. As before, the War Department made a careful examination of ETOUSA’s stated

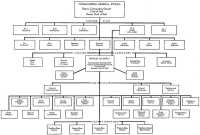

Table 3: Troop build-up in the United Kingdom in 1943

| Arrivals* | End of month strength | ||||||

| Month | Monthly | Cumulative from Jan 42 | Total | Ground Forces | Air Forces | Services of Supply | Hq ETO and Misc |

| January | 13,351 | 255,190 | 122,097† | 19,431 | 47,325 | 36,061 | 5,672 |

| February | 1,406 | 256,596 | 104,510 | 19,173 | 47,494 | 32,336 | 5,507 |

| March | 1,277 | 256,873 | 109,549 | 19,205 | 51,566 | 34,244 | 4,534 |

| April | 2,078 | 259,951 | 110,818 | 19,184 | 53,561 | 33,886 | 4,187 |

| May | 19,220 | 279,171 | 132,776 | 19,204 | 74,205 | 34,028 | 5,339 |

| June | 49,972 | 329,143 | 184,015 | 22,813 | 107,413 | 49,444 | 4,345 |

| July | 53,274 | 382,417 | 238,028 | 24,283 | 132,950 | 73,831 | 6,964 |

| August | 41,681 | 424,098 | 278,742 | 39,934 | 152,548 | 79,898 | 6,362 |

| September | 81,116 | 505,214 | 361,794 | 62,583 | 168,999 | 120,148 | 10,064 |

| October | 105,557 | 610,771 | 466,562 | 116,665 | 200,287 | 148,446 | 1,164 |

| November | 173,860‡ | 784,631 | 637,521 | 197,677 | 247,052 | 191,208 | 1,584 |

| December | 133,716 | 918,347 | 773,753 | 265,325 | 286,264 | 220,192 | 1,972 |

* By ship. Excludes movements by air.

† Includes 13,608 men assigned to Allied Force for this month only.

‡ A large portion of these arrivals consisted of units redeployed from North Africa.

Source: Troop arrivals data obtained from ETO TC Monthly Progress Rpt, 30 Jun 44, ETO Adm 451 TC Rpts. Troop strength data obtained from Progress Rpt, Progress Div, SOS, 4 Oct 43, ETO Adm 345 Troops, and Progress Rpts, Statistical Sec, SGS, Hq ETO, ETO Adm 421–29. These ETO strength data were preliminary, unaudited figures for command purposes, and while differing slightly from the audited WD AG strengths, have been used throughout this volume because of the subdivision into air, ground, and service troops. This breakdown is unavailable in WD AG reports.

needs. Once more it gave its tentative approval, but again pointed out the manpower ceiling under which the War Department was working, noting that the ETO’s troop basis would have to be compared with those of other theaters and weighed against over-all manpower availability. It returned the troop basis with recommended alterations and requested that ETOUSA make certain reductions, particularly in service units.58 In November, after restudying the theater’s needs, General Devers made his counter-recommendation, restoring some of the cuts, but accepting a reduction of more than 125,000 service troops. At the end of November the theater’s over-all troop basis, first and second phases combined, calling for a build-up of forty-seven divisions as of 1 February 1945, stood as follows:59

| Type | Number |

| Total | 2,377,000 |

| Services of Supply | 604,000 |

| Ground Forces | 1,356,000 |

| Air Forces | 417,000 |

The actual initiation of troop movements did not depend on the final approval of the various troop bases, and the BOLERO build-up had started on the basis of flow charts and priority lists worked out

earlier in the year. The ETOUSA air force had made a negligible recovery in the early months of 1943 despite the high priority accorded it at the Casablanca Conference. In April it was able to operate only six heavy bomber groups with a daily average strength of only 153 planes.60 Upon the approval of the Combined Bomber Offensive plan the build-up of the Eighth Air Force assumed a new urgency and the means were now finally found to carry out the movement of both personnel and cargo roughly as planned. The resumption of the BOLERO build-up first became evident in the month of May, when nearly the entire shipment to the United Kingdom (20,000 men) consisted of air units. The air build-up in fact continued to be favored for most of the summer, and from May through August accounted for approximately 100,000 or three fifths of the 165,000 men shipped to the United Kingdom. (Table 3) By the end of the year the air force had achieved a remarkable growth from 16 groups, 1,420 planes, and 74,000 men in May to 46 groups, 4,618 planes, and 286,264 men.61 The movement of air combat units actually proceeded ahead of the estimated shipping schedules set up at TRIDENT.

The SOS and ground force build-up also achieved an encouraging record, but only after a serious lag in the early months. Ground force strength in the United Kingdom remained almost unchanged from January through May, with fewer than 20,000 men (comprising only one division, the 29th), and made only negligible gains in June and July. By December it was built up to 265,325 men. This was far short of the build-up which the theater commander had originally requested in May (390,000 by 31 December), but the shortage was not serious in view of the fact that large-scale ground combat operations were not contemplated until the following spring.

The progress of the service troop buildup gave far more cause for concern, particularly in the early months. The SOS force in the United Kingdom, like the ground forces, had remained almost stationary, with a strength of about 34,000 throughout the first five months of 1943. In June the theater repeated a request which had been heard many times before—to speed up the arrival of service troops in order to take advantage of the long summer days and good weather to advance the construction of the needed facilities in the United Kingdom. There now were additional reasons for a more rapid build-up, for the decision to reinstitute the preshipping procedure resulted in heavy advance shipments of cargo, and it appeared that there would be insufficient British labor to handle more than about seventy-five ships per month. The theater was already employing Medical Corps, ground combat, and air force troops alongside British civilian labor in depots and ports, and the shortage of labor was already adversely affecting certain British services to the U.S. forces, such as vehicle assembly, tire retreading, and coal delivery to North Africa. At one time during the summer the theater commander considered using the entire 29th Division as labor.62

From June through August the theater received fewer than 46,000 service troops. The lag resulted in part from diversion of shipments to another area, in part from the unavailability of the desired types of

units. Despite the earlier restrictions which the Combined Chiefs of Staff had placed on any further diversion of resources to the Mediterranean, the Sicilian operation had met with such brilliant success, and prospects for an Italian collapse were so favorable that the decision was made in July to invade Italy. Once more, therefore, operations in the Mediterranean area asserted a prior and more urgent claim to available resources. In response to requests from General Eisenhower approximately 66,000 troops were diverted to the North African theater, and only 37,000 troops (mostly air units) out of a projected 103,000 could be shipped to the United Kingdom in August.63 Theater officials expected that the net loss would be even greater, and would have a cumulative effect on the total BOLERO program, since the postponement of the SOS build-up would necessarily delay the ETO’s readiness to accept ground and air force units.64

General Lee and the Combined Committee of London learned of the prospective diversions early in July.65 The SOS commander immediately protested, warning the War Department that any further postponement or curtailment of the SOS troop arrivals would jeopardize the cross-Channel operation itself, for the theater was losing unrecoverable time through its inability to undertake the necessary preparations for the later ground force arrivals.66 The inability of the War Department to ship service units of the required types was essentially the fruit of its earlier neglect of the SOS troop basis. Although the activation of service units had been greatly expedited since the fall of 1942, it had been a struggle to obtain from the General Staff the men needed to fill out the units authorized in the 1943 troop basis, and the SOS units had had to be activated earlier than had been anticipated to meet ETOUSA’s requirements.67 So urgent did the need become in the summer of 1943 that the War Department finally resorted to the expedient of diverting partially trained ground and air personnel to the Army Service Forces (formerly the War Department SOS, renamed in March) for training as service troops.68

Shortages in the United Kingdom were particularly acute in the category of engineer construction units needed to complete the program for airdromes, hutments, storage, hospitals, shops, and assault-training facilities. General Lee noted that standards had already been lowered from those recommended by the chief surgeon for shelter and hospital beds, and airdrome standards were also below those of the RAF.69 The SOS commander had asked for twenty-nine engineer general service regiments by 30 September. Late in July the War Department informed him that only nineteen could be shipped unless certain unit training was waived. The theater, as in 1942, was willing enough to train units in the United Kingdom, and therefore accepted the partially trained troops.70 Much the same

situation obtained with regard to air force service troops, and as a result the build-up of combat units took place at the expense of service troops, creating a serious lack of balance in the summer of 1943. In October the Air Forces began shipping thousands of casuals to the United Kingdom, where the Eighth Air Force planned to give them on-the-job training and organize them into various types of service units.71

Beginning in September the shipment of service units improved appreciably. In the last four months of the year the SOS almost tripled its strength in the United Kingdom, rising from 79,900 to 220,200. The Combined Chiefs meanwhile had raised the sights for the U.K. build-up. In August the Allied leaders met in the QUADRANT Conference at Quebec for a full-dress debate on strategy for 1944. By that time the tide of war had definitely turned in favor of the Allies. Italy was at the very brink of collapse; the German armies had already been ejected from the Caucasus and the Don Basin, and were now being forced to give up the last of their conquests east of the Dnieper. For the most part the Quebec meeting resulted in a re-endorsement of the TRIDENT decisions so far as operations in the European area were concerned. It again gave the air offensive from the United Kingdom the highest strategic priority, approved the first product of the COSSAC planners—the OVERLORD plan for cross-Channel attack in May 1944—and directed that preparations should go forward for such an operation. As a result of the diminishing scale of shipping losses it was also possible to raise the target for the BOLERO build-up. Troop movement capabilities were now increased from the previous TRIDENT figure of 1,300,300 to 1,416,900 by 1 May 1944.72

Troop shipments in the remaining four months of the year did not quite achieve the QUADRANT estimates, although the theater received record shipments of air, ground, and service troops from September through December. In October the arrivals topped 100,000 for the first time, and in November rose to 174,000. At the end of the year ETOUSA had a total strength of 773,753 men (as against a cumulative build-up of 814,300 projected at Quebec), which represented slightly more than half of the authorized first phase troop basis. General Devers was acutely aware of the limited port and rail capacity in the United Kingdom, and had hoped for a heavier flow.73 It was obvious at the end of the year, however, that there would have to be heavy shipments in the first months of 1944.

The Flow of Cargo in 1943

The flow of supplies and equipment to the United Kingdom under the revived BOLERO program got under way somewhat in advance of the personnel buildup, largely because of the more favorable cargo shipping situation. As a result of the gradual elimination of the submarine menace and the record-breaking production of shipping, the total tonnage lost from all sources by the Allies and neutrals since September 1939 was more than replaced during 1943. In that year the tonnage constructed was four times the total lost in the same period.74

Cargo shipping had been allocated on the basis of a build-up of 80,000 men in

the first three months, and 169,000 in the second quarter. The subsequent cancellation of troop movements to the United Kingdom freed approximately 150,000 ship tons per month from hauling the equipment of these units, and left the Army Service Forces (ASF) with the problem of finding cargo for the space.

To both ETOUSA and the ASF this situation was ready made for the reinstitution of the preshipping procedure which had been attempted on a limited scale in 1942. ETOUSA in particular wanted equipment to arrive in advance of troops so that it could be issued to them on their arrival and loss of training time could thereby be avoided. Pre-shipment would also preclude telescoping heavy shipments in the months immediately preceding the invasion, when British port capacity was expected to be a decisive limiting factor.

In February and March General Andrews repeatedly urged the War Department to adopt this procedure. Early in April he came forward with a detailed proposal requesting that shipments arrive thirty to forty-five days in advance of troops, or, as a less desirable alternative, that organizational equipment be shipped force-marked and arrive at least simultaneously with the arrival of troops. The War Department General Staff gave the request a cool reception. Recalling the unhappy experience with pre-shipped supplies in the summer of 1942, when much equipment had been temporarily lost in the U.K. depots, the General Staff feared that this situation might be repeated. Theater officials were fully aware of the danger, and it was for precisely this reason that they were at the same time urging the early shipment of service troops. There was also a question as to whether equipment should be shipped in bulk or in sets for “type” or specific units. Because of the habit of shipping equipment force-marked, precedent indicated the latter method. But the instability of the troop basis in the spring of 1943, and the impossibility at that time of accurately forecasting troop arrivals, reduced to guesswork the planning of advance shipment for specific units. Bulk shipment, on the other hand, would allow the build-up of depot stocks in the United Kingdom with less regard for lists of specific troop units and could thus proceed with relative disregard for changes in the troop basis.75

At the urging of both ETOUSA and the ASF, the General Staff gave a cautious approval to the preshipment concept on 16 April. As authorized at that time, the plan provided for the shipment of organizational equipment, force-marked, thirty days in advance of the sailing of units. In effect, this was not preshipment at all as envisaged and proposed by the theater, for it meant that equipment would arrive, at best, at approximately the same time as the units. Moreover, it adhered to the old force-marking practice by which sets of equipment were earmarked for specific units and therefore did not embody the idea of shipments in bulk. Advance shipment was applied only to a selected list of items—combat maintenance, boxed general purpose vehicles, and Class IV supplies (items such as construction and fortification materials, for which allowances are not prescribed)—in which production at this time exceeded current requirements. Established priorities then in force also limited the application of the program, since North African operations, training requirements in the United States, the bomber offensive in the United Kingdom, and two major operations in

the Pacific all had more urgent call on supplies. Applying the force-marking principle even made it difficult to compute requirements because of the unstable troop basis. In general, then, preshipment was accorded hardly more than lip service at this stage, reflecting both the War Department’s reluctance to go further and the theater’s continued low priority position.

Unsatisfied with this half-hearted acceptance of the preshipment idea, the ASF immediately exerted efforts to obtain a fuller implementation of the concept. On 16 May it succeeded in getting OPD’s approval of an amended procedure which overcame one of the most restrictive features of the original directive. To circumvent the difficulty of computing requirements for the very tentative troop basis then in existence, it was decided that equipment would not be shipped for specific units, but rather for “type” units. While shipments were ostensibly computed from the troop basis, the troop basis was recognized as largely fictitious, and equipment was to be shipped for type infantry divisions, antiaircraft battalions, port battalions, and so on, on the safe assumption that the theater would eventually need and get these types of units. The equipment was to be stockpiled or pooled in U.K. depots for issue to such units upon their arrival. Thus, while having a definite relationship to a troop basis of tentative dimensions, equipment was to be shipped in bulk and not earmarked for particular units.

Even this amendment did not permit a full blossoming of the preshipment idea as originally conceived. Supplies intended for advance shipment still were to be drawn only from excess stock or production. They not only held a priority below that assigned to normal shipments to the United Kingdom, which was already near the bottom of the priority list of overseas theaters, but were far down on the priority list of units in various stages of training in the United States. Only after all the prescribed training allowances of units had been filled as they moved upward in the priority scale in preparation for overseas movement could supplies be made available for advance shipment purposes.

The preshipment procedure therefore began under heavy handicaps. Other theaters, the training allowances of troops in the United States, and high priority operations all took precedence. In fairness to those who worked out the emasculated version of the scheme it should be said that this was probably the highest position preshipment could be accorded at the time. It was wholly consistent with current strategic aims, for the cross-Channel operation was to remain in doubt for several months to come. The immediate aim of preshipment, after all, was not to guarantee an unlimited build-up for BOLERO, but to obtain sufficient cargo to fill the available shipping space in the next few months. In the four months from May through August the “surplus” of space over the normal requirements of troops moving to the United Kingdom was expected to total 784,000 measurement tons. Beginning in September the heavier troop flow was expected to absorb all available tonnage for the cargo which would normally accompany units. In fact, cargo shipping space would fall short of requirements in the fall, and the preshipment program was therefore anticipating the heavy cargo requirements of later months. These expected developments gave the proposal an unassailable logic.

Even in the context of its limited objective,

Table 4: Cargo flow to the United Kingdom in 1943

| Measurement tons Received | Long tons Received | ||||

| Month | Monthly shipments (measurement tons) | Monthly | Cumulative from Jan 42 | Monthly | Cumulative from Jan 42 |

| January | 129,694 | 117,913 | 2,297,909 | 38,562 | 881,554 |

| February | 92,948 | 75,566 | 2,373,475 | 20,373 | 901,927 |

| March | 115,856 | 65,767 | 2,439,242 | 24,719 | 926,646 |

| April | 134,950 | 111,245 | 2,550,487 | 60,784 | 987,430 |

| May | 251,832 | 87,056 | 2,637,543 | 36,593 | 1,024,023 |

| June | 542,001 | 348,900 | 2,986,443 | 176,033 | 1,200,056 |

| July | 779,906 | 670,024 | 3,656,467 | 292,701 | 1,492,757 |

| August | 730,300 | 753,429 | 4,409,896 | 324,308 | 1,817,065 |

| September | 906,981 | 778,102 | 5,187,998 | 302,914 | 2,119,979 |

| October | 1,018,343 | 956,888 | 6,144,886 | 395,359 | 2,515,338 |

| November | 848,054 | 790,754 | 6,935,640 | 322,757 | 2,838,095 |

| December | 910,482 | 1,008,150 | 7,943,790 | 378,078 | 3,216,173 |

Source: Shipment data from [Richard M. Leighton] Problem of Troop and Cargo Flow in Preparing the European Invasion, 1943–44, prep in Hist Sec, Control Div, ASF, MS, p. 154, OCMH. Receipt data from TC Monthly Progress Rpts, Statistics Br, OCofT, SOS ETO, ETO Adm 450–51.

however, preshipment did not achieve its goal. Despite strenuous efforts, sufficient cargo could not be found to fill the space released by the reduction in troop movements. A total of 135,000 measurement tons was shipped to the United Kingdom before the end of April, but this left approximately 100,000 tons capacity which could not be filled and was therefore turned back to the War Shipping Administration.76 The same inability to fill available shipping space continued in varying degree throughout the next four months. Approximately 1,050,000 tons of shipping were made available for May and June, but less than 800,000 tons of cargo were dispatched. (Table 4) In July 780,000 tons of an allocated 1,012,000 tons of space were utilized, and in August only 730,000 tons were shipped as against the available 1,122,000. Of the 2,304,000 measurement tons shipped to the United Kingdom in the four-month period from May through August, slightly more than 900,000 tons, or 39 percent, represented pre-shipped cargo. This was a large proportion, but hardly represented a spectacular achievement in preshipment. The percentage was this high only because troop sailings to the United Kingdom were small in these months and the normal accompanying equipment and supplies accounted for a relatively small portion of the total cargo space. Pre-shipment was actually failing to achieve its immediate purpose, which was to utilize

all available shipping. Furthermore, full advantage was not being taken of the long summer days when British ports were at their maximum capacity and relatively free from air attack.

The failure to achieve even the narrow aims of the preshipment program is not too surprising in view of the status of Allied plans in the summer of 1943. Fundamental to the failure was the low priority accorded preshipment cargo. This in turn reflected in part the doubts that surrounded future strategy. Even the TRIDENT Conference, with its resolutions on the Combined Bomber Offensive, cross-Channel attack, and the accelerated build-up, did not resolve these doubts. The temptation still remained to commit Allied resources more deeply into the Mediterranean, and throughout the summer the possibility remained that there might be no cross-Channel operation after all. Late in June came the request from North Africa for additional personnel, which further upset planned troop flow to the United Kingdom, and in July there were indications that the entire European strategy would be reconsidered.

In view of the wavering strategic plans, preshipment definitely involved risks. Tying up additional equipment in the U.K. depots might actually make it difficult to equip a force for a major operation elsewhere except by reshipping the stocks from the United Kingdom. Logistic plans had been mapped out at TRIDENT to conform with strategy; but with the strategic emphasis subject to change, logistic plans could hardly be stable. Nothing demonstrated so pointedly the necessity for firm objectives if the logistic effort was to be effective.

The instability of preshipment plans was best exemplified in the Chief of Staff’s directive of 8 July ordering the advance shipment suspended after 15 August until the strategic situation was clarified. By early August most of the equipment for troops scheduled to reach the ETO by the end of 1943 had been shipped, and it was necessary to reach a decision on preshipment of equipment for troops sailing after the first of January. Fortunately the air had cleared somewhat by this time, and the list of ground units scheduled to sail before 1 May 1944, completing the first phase troop basis, was complete. On 13 August came approval of preshipment on the extended troop basis, thus allowing advance shipment of supplies to continue.

It was only a few days later that the QUADRANT Conference at Quebec reaffirmed earlier decisions on operations in Europe, dispelling much of the fog of the past two months and incidentally reaffirming the validity of preshipment. The conferees again recognized the all-important problem of U.K. port capacity, which had a significant bearing on the entire cargo shipping program. British officials had already called attention to the problem at Casablanca and at TRIDENT, noting that the maximum practical limit was 150 shiploads per month, even with the help of U.S. dock labor. At the TRIDENT Conference in May they had agreed to a quarterly schedule of sailings to meet U.S. requirements averaging 90 ships per month in the third and fourth quarters of 1943, and 137 per month in the first and second quarters of 1944. By August, however, it had become evident that the slow rate of troop and cargo movements during the spring and summer would force a tremendous acceleration of movements in the fall and winter, which would be beyond the capacity of U.K. ports. British officials were particularly

concerned about the pressure in the months immediately preceding the invasion, when ports would also be taxed by out-loading activities. The primary cause of this limitation was the shortage of labor, and measures were already being taken to dispatch additional U.S. port battalions to the United Kingdom in anticipation of the deficits.

At Quebec British officials insisted on a revision of the earlier sailing schedules, calling for an increase to 103 shiploads per month in the fourth quarter of 1943, and a reduction to 119 per month in the first and second quarters of 1944.77 Advancing the heavier shipments to the fall of 1943 was obviously indicated to relieve the strain in the early months of 1944, and also to make up for the lag during the summer of 1943. The schedule revision meant a net reduction of 77 ships for the nine-month period, however, and placed a ceiling on U.K. reception capacity which was considerably below the quantity of ships and cargo the War Shipping Administration and the ASF could provide. So far as preshipment was concerned, the remaining months of 1943 were to be crucial, since the equipment accompanying the heavy troop unit movements in 1944 would certainly absorb the bulk of the available shipping after the first of the year. Efforts were therefore bent toward finding cargo to fill the available shipping in the remaining months of 1943.

Cargo shipments to the United Kingdom in August totaled only 730,300 measurement tons, and well reflected the numerous logistical problems which could affect the carrying out of BOLERO. Rearmament of additional French divisions in North Africa, first of all, had drawn off about 250,000 tons. In addition, August had seen the diversion of U.S. personnel to North Africa, resulting in smaller troop movements to the United Kingdom and, in turn, relatively small normal cargo shipments. Consequently, of the 730,200 tons shipped that month, an abnormally large proportion—about 48.7 percent—represented pre-shipped cargo, even though the total tonnage was not large. Shipments in September and October were considerably larger, totaling 906,981 and 1,018,343 measurement tons, respectively. In these months, however, troop sailings were so much heavier that pre-shipped cargo accounted for only 40.4 and 36.5 percent.

November shipping also felt the effect of outside logistic factors. The decision had been made at TRIDENT, and reaffirmed at Quebec, to transfer four American divisions from the Mediterranean to the United Kingdom. This redeployment was largely carried out in November and had its repercussion on the U.K. build-up by diverting troop shipping and cutting deeply into the planned troop sailings from the United States. Once more the ASF was suddenly faced with the problem of finding equipment to fill the cargo shipping released by this cancellation of troop movements. The result was evident in the tonnage figures for November. Less than 850,000 tons were shipped that month, but of this total 457,868 tons, or 54 percent, were pre-shipped equipment, the largest advance shipment yet achieved in both actual tons and percentage of total cargo. Even this figure was misleading, however, for three of the four divisions transferred from North Africa had to be equipped from stocks established in the United Kingdom. In December a total of 910,482 measurement tons was shipped to

the United Kingdom. Because of the considerably heavier troop sailings with their accompanying equipment, however, pre-shipped cargo totaled only 318,314 tons, or 35 percent. A comparison of actual ship sailings with those scheduled in May and August is given below:78

| Date | TRIDENT | QUADRANT | Actual |

| 3rd Quarter 1943 | 259 | – | 241 |

| 4th Quarter 1943 | 280 | 308 | 273 |

Actual sailings, therefore, did not even achieve the ceilings established at the TRIDENT Conference, much less the accelerated schedule agreed on at Quebec for the last three months of 1943. A comparison of total tonnages shipped with tonnage allocated likewise reveals the inability to allocate sufficient cargo to fill the available shipping. In the eight-month period from May through December approximately 1,400,000 tons of shipping were allocated in excess of the ASF’s ability to provide cargo. The result foreboded serious trouble, for the mounting troop movements of 1944 were bound to turn the surplus tonnages of 1943 into deficits.79

At the heart of the supply build-up problem was the system of priorities which had been necessitated by the inability of U.S. production facilities to fill all requirements simultaneously. Existing priorities relegated ground force cargo for the European theater to eighth place (priority A-1b-8) and gave advance shipments to the theater an even lower rating. Fully aware of the priority handicap, the ASF in the early stages of the preshipment program had suggested a revision of priorities for equipment as applied to units in training in the United States, but met strong opposition from the Army Ground Forces. In September the ASF again raised the question, this time with strong backing from the theater. ETOUSA was particularly worried about certain critical shortages and pointed out that even minimum requirements of engineer and signal equipment had not been met. There was need for 125,000 long tons of organizational equipment for troops arriving in October alone, and in view of the time required for distribution, supplies were neither arriving sufficiently in advance nor keeping pace with the personnel build-up.80 Yet no action was taken to change priorities, and in September and October sufficient cargo was again lacking to fill available shipping space.

In November the ASF finally succeeded in persuading the General Staff to accord cargo for preshipment the same priority as normal theater shipments (that is, A-1b-8 for ground forces and A-1b-4 for air forces). But this proved to be a minor concession. At the end of November, when the new priority went into effect, it was already apparent that available cargo space could not be filled for that month.

More important, by this time troop movements to the United Kingdom had increased to such a scale that the bulk of available tonnage was taken up by the normal equipment accompanying troops. In other words, the flow of personnel was now beginning to catch up with the flow of cargo, and it was no longer possible to advance-ship large tonnages. The stock of pre-shipped equipment in the United Kingdom was beginning to melt away. Of the estimated 1,040,000 tons of pre-shipped equipment in the United Kingdom on 1 November, almost half was to be issued to arriving troops within two months. Some question even arose as to whether an adequate flow of cargo could be maintained to support the scheduled flow of troops. There certainly were doubts about the possibility of meeting the critical shortages under existing priorities.

By the end of the year, then, the nub of the problem was the theater’s priority, which it now became imperative to raise. Early in December the ASF asked OPD to raise ETOUSA’s priority for air force equipment from 4 to 1, and that for ground force equipment from 8 to 2. It requested the same priority for advance shipments. The General Staff approved this plan and put it into effect before the end of the year. In the remaining months before D Day ETOUSA was therefore to enjoy the highest priority for all items required. Enormous tonnages still remained to be shipped to meet the requirements of the 1 May troop basis and the many special operational needs of the cross-Channel invasion.