Chapter 7: The OVERLORD Logistical Plan

The Artificial Port

The magnitude of the cross-Channel operation is most fully revealed in its logistic aspects. Because it was to be an amphibious operation OVERLORD’s supply problems were many times magnified. Moving an attacking force and its equipment across the Channel in assault formation required, first of all, a highly coordinated staging procedure in the United Kingdom, large numbers of special craft, and meticulously detailed loading plans. Following the capture of a lodgment it involved the rapid organization of the beaches as a temporary supply base, the quick reinforcement of the forces ashore and the build-up of supplies, and the subsequent rebuilding of ports and development of lines of communications so that sustained operations of the combat forces could be properly maintained.

The detailed planning for the various tasks involved did not begin until after the establishment of SHAEF and the designation of the Supreme Commander in January 1944. In the following month the plans of the various headquarters began to appear. The basic operational plan, known as the NEPTUNE Initial Joint Plan, was issued by the joint commanders—that is, the commanders of the 21 Army Group, the Allied Naval Expeditionary Force, and the Allied Expeditionary Air Force on 1 February. First Army’s plan, which constituted something of a master plan for U.S. forces in view of that organization’s responsibility for all aspects of the operation, both tactical and logistical, in its early stages, appeared on 25 February. Those of its subordinate commands, V and VII Corps, were issued on 26 and 27 March respectively. On the logistical side the joint commanders’ Initial Joint Plan was supplemented on 23 March by instructions known as the Joint Outline Maintenance Project. The outline of the American logistic plan was issued as the Joint Administrative Plan by the U.S. administrative staff at 21 Army Group on 19 April. This was followed on 30 April by the Advance Section plan, covering the period from D plus 15 to 41, and on 14 May by the over-all Communications Zone plan issued by the Forward Echelon. The SOS mounting plan had appeared on 20 March.

The extent to which logistic considerations had entered into the deliberations of the COSSAC and SHAEF planners has already been pointed out. In the eyes of the planners the successful invasion of France was dependent first on breaking through the coastal defenses and establishing a beachhead, and second, on the subsequent battle with enemy mobile reserves. The enemy’s main line of resistance was the coast line itself, and it was known that the first objective of the enemy’s defense strategy was to defeat the

invaders on the beaches by the rapid deployment of his mobile reserves. The outcome of this critical battle with enemy reserves was seen as depending primarily on whether the Allied rate of build-up could match the enemy’s rate of reinforcement, and the degree to which this reinforcement could be delayed or broken up by air action or other means. The enemy’s second defense objective would be to prevent the Allies from securing ports, for the capture of an intermediate port, such as Cherbourg, and of other ports, was a prime necessity for the sustained build-up of men and supplies.1

In the original July 1943 outline plan of OVERLORD, which served as a basis for the later planning, it was estimated that the provision of adequate maintenance for the Allied forces in the initial stages, including the building of minimum reserves, would require a flow of supplies rising from 10,000 tons per day on D plus 3 to 15,000 tons on D plus 12, and 18,000 on D plus 18. These figures were based on an assault by three divisions, a build-up to a strength of ten divisions by D plus 5, and the landing of approximately one division per day thereafter.2 The capture of the Normandy and Brittany groups of ports was expected to insure discharge capacity sufficient to support a minimum of at least thirty divisions, and it was believed that if all the minor ports were developed this force could be considerably augmented. But frontal assaults on the ports themselves had been ruled out, and Mediterranean experience had shown that ports, even if captured shortly after the landings, would be found demolished and would be unusable for some time. The total capacity of the minor ports (Grandcamp-les-Bains, Isigny, St. Vaast-la-Hougue, Barfleur) on the front of the assault was not expected to reach 1,300 tons per day in the first two weeks. According to a later estimate, the capture of Cherbourg was not expected before D plus 14. Its capacity on opening was estimated at 1,900 tons, rising to only 3,750 tons after 30 days. In any event it was not sufficient for the maintenance of the lodgment forces. The Brittany ports would not offer a solution before D plus 60. It was clear, therefore, that the initial build-up would have to be over the beaches, and it was estimated that eighteen divisions would have to be supported over the beaches during the first month, twelve in the second, with the number gradually diminishing to none at the end of the third month as the ports developed greater and greater capacity.

The COSSAC planners considered the capacities of the beaches (which at that time did not include the east Cotentin) more than sufficient to maintain these forces, and believed that tactical developments should make possible the opening of additional beaches after D plus 12.3 Unfortunately these capacities were largely theoretical, and in this fact lay the very crux of the initial build-up problem. The Allies had two enemies to reckon with in their invasion of the Continent—the

Germans and the weather. By far the more unpredictable of these—”more capricious than a woman,” as one observer put it—was the weather.4 Meteorological studies covering a ten-year period indicated that the month of June was likely to have about twenty-five days of weather suitable for the beaching of landing craft. The record also revealed an average of about two “quiet spells” of four days or longer per month between May and September. Forecasting more than four days of fair weather was difficult, however, and it therefore followed that from D plus 4 onward maintenance plans would have to allow for the fact that on some days beach operations would be impracticable. To compensate for these interruptions it would be necessary to increase daily discharge by some 30 percent. Furthermore, even though it might be physically possible to land the necessary tonnages, a great problem of movement and distribution forward to the depots and the troops was inherent in maintenance on such a large scale in so restricted a beachhead. It was therefore necessary to develop discharge facilities for bad weather in order to reduce the peak loads over the beaches on operable days and to even out the flow of traffic through the maintenance areas. In addition, naval authorities warned that unless steps were taken to provide facilities for the landing of vehicles, the cumulative damage to craft continuously grounding on beaches might well reduce the available lift and jeopardize the success of the whole operation. The provision of special berthing facilities was considered a matter of such paramount importance, in fact, that the naval commander in chief stated he could not undertake such an operation with confidence without them.5

The planners made it clear at an early date, therefore, that unless adequate measures were taken to provide sheltered waters by artificial means the operation would be at the mercy of the weather, and that a secondary requirement existed for special berthing facilities within the sheltered area, particularly for the discharge of vehicles. They estimated that the minimum facilities required for discharge uninterrupted by weather were for a capacity of 6,000 tons per day by D plus 4–5, 9,000 tons by D plus 10–12, and 12,000 tons when fully developed on D plus 16–18.

The Allied planners proposed to meet this problem by building their own harbors in the United Kingdom, towing them across the Channel, and beginning to set them up at the open beaches on the very day of the assault. While their solution was in a sense an obvious one, it was at the same time as unconventional and daring in its conception as any in the annals of military operations.

The concept of a “synthetic” harbor was not entirely a new one, although a detailed blueprint for a prefabricated port was not immediately forthcoming. There was at least one precedent for the concept of “sheltered water” created for the express purpose of aiding military operations. Mr. Churchill had proposed a breakwater made up of concrete caissons in 1917 in connection with proposed landings in Flanders.6 In World War II Commodore John Hughes-Hallett, senior naval representative of the C-in-C Portsmouth, was the real progenitor of the artificial

harbor, although the Prime Minister again provided much of the inspiration and the drive in working out the solution of this basic invasion problem. In May 1942 Mr. Churchill sent his oft-quoted note to the Chief of Combined Operations directing that a solution be found for the problem of special berthing facilities on the far shore. Suggesting piers which “must float up and down with the tide,” he ordered: “Don’t argue the matter. The difficulties will argue for themselves.”7

Under the direction of COSSAC British engineers carried out experiments in the spring of 1943 to determine the practicability of constructing a prefabricated port, and they succeeded in building a floating pier that survived the test of a Scottish gale. But the exact form which such a port should take was not immediately determined, and the digest of OVERLORD presented by General Morgan to the Combined Chiefs of Staff at Quebec in August 1943 consequently included only the most tentative outline plan for such a harbor. The sheltered anchorage, this plan “suggested,” would be formed simply by sinking nineteen blockships to form a breakwater. Berthing facilities would be provided by four pierheads, consisting of four sunken vessels, which were to be connected to the shore by “some form of pontoon equipment.” The daily discharge capacity of such an installation was expected to be approximately 6,000 tons.8 The relatively simple form of the harbor thus outlined hardly suggested the myriad engineering problems that still had to be overcome, and resembled only in its barest essentials the harbors which eventually took form.

The difficulties did indeed argue for themselves as Mr. Churchill predicted, for the magnitude and complexity of the task became more and more apparent. Many of the world’s ports were “artificial” in that their sheltered harbors had been created by the construction of breakwaters. Cherbourg and Dover were both “made” ports in this sense. But whereas it had taken seven years to build the port of Dover in peacetime, the Allies were now faced with the problem of building a port of at least equal capacity in a matter of a few months, towing it across the Channel, and erecting it on the far shore amidst the vicissitudes of weather and battle. The plans as they were eventually worked out in fact called for the erection of two ports within fourteen days of the landings.

Two major requirements had to be met: a breakwater had to be provided to form sheltered anchorage and thus permit discharge operations in bad weather; piers were needed onto which craft could unload and thus supplement discharge from beached craft. Several solutions were considered in connection with the problem of providing sheltered water. In 1942 Commodore Hughes-Hallett proposed the use of sunken ships to form a breakwater. To the Admiralty this suggestion at first represented nothing but the sheerest extravagance in view of the impossible task it already faced in replacing the shipping lost to enemy submarines. The use of floating ships had the same drawback, of course, and in addition presented a difficult mooring problem.9 One of the more novel solutions suggested was the creation of an “air breakwater.” By the use of pipes on the

ocean floor this scheme proposed to maintain a curtain of air bubbles which theoretically would interrupt the wave action and thus provide smooth waters inshore of the pipe.10 This idea was actually not new either. Studies along this line had been carried out in the United States forty years before, and both Russian and U.S. engineers had conducted model experiments since 1933, although without conclusive results. The bubble breakwater would have required such large power and compressor installations that it was impractical for breakwaters on the scale envisaged, and the idea was discarded as infeasible early in September 1943.11

Meanwhile experimentation was carried on with several other schemes. One of the earliest to receive attention was a device called the “lilo,” or “bombardon.” Li-lo was the trade name for an inflated rubber mattress used on the bathing beaches in England. A British Navy lieutenant had casually observed at a swimming pool one day that the Li-lo had the effect of breaking up wavelets formed on its windward side, creating calm water in its lee, and conceived the idea of constructing mammoth lilos for use as a floating breakwater. The idea was believed to have possibilities, and experimentation began in the summer of 1943. As first conceived the lilo—or BOMBARDON, the code name by which it was better known—had two basic components: a keel consisting of a hollow concrete tube 11 feet in diameter; and a canvas air bag above, about 12 feet in diameter and extending the entire length of the unit. The keel could be flooded and submerged while the air bag extended above water. The BOMBARDONS were 200 feet long and had a 12-foot beam and a 13-foot draft, the concrete keel alone weighing about 750 tons. The first designs called for a rubberized canvas air bag, and a few units of this type were constructed. Since they were vulnerable to puncture by small arms fire, however, later designs provided for a steel cruciform superstructure, about 25 feet in width.12

In essence the BOMBARDON breakwater would consist of a string of huge, air-filled, cylindrical floats, moored at each end, but laced together to form a thin screen of air which was intended to break up wave action and thus provide sheltered water. The BOMBARDONS were believed to have an advantage over sunken blockships since they could be moored in comparatively deep water and thus provide sheltered water for the deeper-draft Liberties.13 Nevertheless, from the very beginning there were doubts about their effectiveness and feasibility, and they were never expected to do more than dampen wave action and provide anchorage supplementary to the main harbor for deep-draft ships.

Meanwhile experimentation had gone forward on another solution to the problem—the caisson, or PHOENIX, which eventually was to constitute the main element in the breakwater forming the harbor. The PHOENIXES were huge, rectangular, concrete, cellular barges designed to perform much the same function as sunken blockships. Their main specification was that they have sufficient weight and strength to withstand summer Channel weather; at the same time they had to be towable, easily sinkable, and of simple enough design to be constructed with a

CAISSONS, used for MULBERRY breakwater, sunken in position off the beaches

CAISSON afloat

minimum expenditure of labor and materials. Five types were eventually built, varying between 175 and 200 feet in length and between 25 and 60 feet in height, the largest of them weighing 6,000 tons and drawing 20 feet of water. The PHOENIX consisted fundamentally of a reinforced base with side walls tied together by reinforced concrete bulkheads. Each was to be given a 10-foot sand filling to achieve the proper draft, then towed across the Channel, flooded, and sunk at the 5-fathom (30-foot) line. The great height of the PHOENIXES was dictated by the desire to provide a breakwater at sufficient depth to accommodate Liberty ships, which drew as much as 28 feet when loaded. The beaches selected for the assault had a very shallow gradient and tide ranges of more than 20 feet. The harbor therefore had to extend a full 4,000 feet from the shore in order to provide sheltered water for Liberty ships at low tide, and the largest caissons had to be 60 feet high in order to rest on the ocean floor and still provide a sufficient breakwater for deep-draft vessels at high tide.14

Experimentation on the second vital portion of the harbor—the berthing and unloading facilities within the breakwater—had begun somewhat earlier in response to the Prime Minister’s directive in 1942. This was fortunate, for the engineer problems involved proved far more complex than those met in the construction of the PHOENIXES. Once again the gradient of the beaches and tidal conditions largely determined the requirement. Low tide along the Normandy coast uncovered as much as a quarter of a mile of beach, and it was necessary to go out another half mile to reach water of sufficient depth—12 to 18 feet—for the discharge of coasters.

The equipment developed to bridge this gap consisted of two basic components: pierheads, at which vessels were to berth and unload; and piers or roadways which connected the pierheads with the shore. Both were designed mainly by the British and involved an ingenious piece of engineering. The Lobnitz pierhead, as it was called, was an awesome-looking steel structure 200 feet long, 60 feet wide, and 10 feet high, weighing upwards of 1,500 tons. At each corner of the structure was a 4 x 4-foot spud leg 90 feet high, the height of which could be adjusted independently by means of winches located between the decks. These spud legs could be retracted during the towing of the structure. Once the pierhead was placed in position the legs were lowered, their splay feet digging into the sea floor to steady the structure, and their height was then adjusted to keep the pierhead at uniform height above water at all stages of the tide. The Lobnitz pierheads were intended to provide the principal unloading facilities for LCTs and LSTs that were not beached and for coasters. They were so designed that any number could be linked together to form an extended berth. To connect pierheads with the shore a flexible steel roadway, known as the WHALE, was developed. The WHALE pier consisted essentially of 80-foot sections of steel bridging, linked together by telescopic spans which gave it the needed flexibility to accommodate itself to wave action, the entire WHALE structure resting on concrete and steel pontons known as “beetles.” At low tide the sections near the shore would come to rest on the sand.

In the summer of 1943 the design of the artificial harbor had hardly reached the finality suggested by the above descriptions

LOBNITZ Pierhead

of its various components. Because experimentation had not yet produced conclusive solutions to many problems, the plan which COSSAC submitted at Quebec in August was necessarily sketchy and vague. Nevertheless the Combined Administrative Committee of the Combined Chiefs of Staff concluded at that time that the construction of artificial harbors was definitely feasible, and approved the project in its general outline. Early in September it rejected the bubble breakwater idea, but recommended continued experimentation with all the other proposed solutions—BOMBARDONS, PHOENIXES, and sunken and floating ships—and urged the immediate construction of PHOENIXES and BOMBARDONS without awaiting the completion of trials and prototypes of the latter. These projects were given the highest priority for labor, equipment, shipping space, and supplies, and construction of the first units now began in earnest.

The respective spheres of responsibility of the United States and Britain with regard to experimentation and construction were also defined in September. By far the largest portion of the work had to be carried out in the United Kingdom, and the British consequently assumed major responsibility for the design, testing, and construction of the PHOENIXES, BOMBARDONS, pierheads, and WHALE bridging.

Trials with floating-ship breakwaters were to be carried out in the United States, and the United States was also called on to provide some of the tugs that would be required for towing purposes beginning just before D Day. The construction of BOMBARDONS and the provision of ships for the breakwater were Admiralty responsibilities; all other components were to be designed and built by the War Office.15

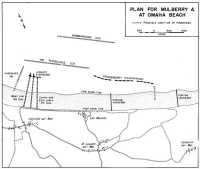

The principal units under construction or trial by late November were the BOMBARDONS, PHOENIXES, sunken- and floating-ship breakwaters, pierheads, and piers.16 There still was no definite blueprint of the harbors at that time, for there was continuing indecision as to the form the harbor should take. The use of sunken ships was still being considered, although it was realized that they were adaptable as a breakwater only in shallow water. The use of floating ships as a deep-water breakwater received less and less favorable consideration because of the mooring problem involved.17 The relative merits of BOMBARDONS and PHOENIXES were still being discussed, but there was continuing doubt as to the practicability of the former. Despite the indecision on these matters the final COSSAC draft of OVERLORD, published late in November 1943, specifically provided for two major artificial ports, one to be located at Arromanches-les-Bains in the British sector, with a capacity of 7,000 tons per day by D plus 16 or 18, and one at St. Laurent-sur-Mer in the American sector, with a capacity of 5,000 tons. For reasons of security the two projects had by this time ceased to be referred to as artificial ports. Late in October they had been christened with the code name by which they were henceforth known, the American port being designated MULBERRY A, and the British port as MULBERRY B.18

The design of the ports was more clearly established early in 1944. By January the concrete caisson or PHOENIX was definitely adopted as the principal unit of the breakwater. It was to be supplemented by sunken ships, the main reason being that sheltered waters were needed for a large number of craft in the earliest stages of the operation. Staff requirements had been amended in January to provide facilities for the discharge of 2,500 vehicles per day (1,250 at each port) by D plus 8 in addition to the tonnage already mentioned, and for shelter for small craft. The MULBERRIES were still big question marks at this time, as indeed they continued to be until the very time they began operating. In any case, naval authorities were very doubtful as to whether the harbors could be effective by D plus 4, when a break in the weather could be expected. They had therefore proposed the construction of five partial breakwaters, known as GOOSEBERRIES, each about 1,500 yards long, formed of blockships (referred to as CORNCOBS) sunk on the 2-fathom (12-foot) line at low water. There was to be one GOOSEBERRY at UTAH Beach, one at OMAHA, and one at each of the three British beaches. Seventy ships were to be used for this purpose, steaming across the Channel and going into position on D plus 1. Ballasted to draw 19 feet of water, they were to be prepared with explosive charges which would be fired after the

ships were properly planted, blowing holes below the water line so that they would sink rapidly.19 These shallow-water GOOSEBERRIES would provide early protection for the large number of tugs, ferries, DUKWs, and landing craft plying between the ships and beaches and for the craft which had been beached. At OMAHA and Arromanches they would tie in with the PHOENIXES to form a longer breakwater enclosing the entire harbor.20 The sheltered area formed by the breakwater at MULBERRY A was to provide a harbor of about two square miles, with moorings for 7 Liberty ships, 5 large coasters, and 7 medium coasters.

The plans for berthing and discharge facilities at the American installation finally called for three WHALE piers or roadways, one of 40 tons capacity (which could carry tanks) and two of 25 tons capacity. All three were to extend more than 3,000 feet out from the shore to about the two-fathom line. There they were to converge on six Lobnitz pierheads, grouped to accommodate both LSTs and coasters. These installations were to give the port a capacity of 5,000 tons of cargo and 1,400 vehicles per day. This was regarded as a conservative estimate, and the capacity of the harbor was actually believed to be well in excess of this minimum.21 In addition to these facilities, two ponton causeways were to be constructed at both OMAHA and UTAH Beaches to boost the unloading facilities for small craft such as LCTs and barges. These causeways were to be built of 5 x 7 x 5-foot ponton cells, bolted together into sections two cells wide and thirty long, and linked to form a roadway 14 feet wide and 2,450 feet long.22 (Map 7)

Both the British and American MULBERRIES eventually also included a row of BOMBARDONS, despite continued misgivings as to their probable effectiveness.23 These ungainly looking floats were to be placed about 5,000 feet seaward of the high-water mark to break the swell and form an additional deep-water anchorage for the discharge of Liberty ships. The UTAH Beach installation was to be much less elaborate. It was to have only a GOOSEBERRY breakwater, formed by sinking ten blockships beginning on D plus 1, and the two ponton causeways.

Over-all command of both MULBERRIES was given to Rear Adm. William Tennant (British). On the U.S. side Capt. A. Dayton Clark was placed in command of MULBERRY A, organized as Naval Task Force 127.1, but usually referred to as Force MULBERRY. Brigadier Sir Harold Wernher was designated to coordinate the work of the War Office and the civilian Ministries of Labour and Supply in the construction of the many components of the ports.

The construction and assembly of all the special port equipment proved a formidable task, and, along with the many other preinvasion preparations, taxed the resources of the United Kingdom to the

Map 7: Plan of MULBERRY A at OMAHA Beach

very limit in the last months before D Day. Many a sacrifice had to be made to permit the huge project to go forward, the Ministry of Labour giving up expert tradesmen and power equipment, the Army temporarily releasing men from the colors, the Navy foregoing frigate and aircraft carrier production. As General Morgan later observed, “Half of England seemed to be working on it and a lot of Ireland as well.”24 Despite the high priorities covering all phases of the project, planners and commanders responsible for the MULBERRIES were haunted by a thousand and one problems and fears until the ports were finally established, and they had to make many compromises with the goals originally set. Early in 1944, plans called for the construction of 113 BOMBARDONS, 149 PHOENIXES, 23 pierheads, and 6 roadways, and for the acquisition of 74 vessels for the sunken-ship breakwaters. The towing problem involved in the assembly and movement of the 600-odd major units involved was unprecedented. It was estimated at first that 200 tugs

would be needed for the task and that they would be occupied a full three months.

These requirements soon proved beyond the capabilities of U.K. resources. The construction of PHOENIXES had begun at the end of October 1943. Within two months the work had already fallen three or four weeks behind schedule, partly because the design of the caissons was altered, partly because the proper types of freight wagons to deliver steel were in short supply, and partly because contractors were unable to obtain the allocation of enough laborers, particularly in certain skilled categories. By 1 December 15,000 workers were supposed to have been assigned to the PHOENIXES, but less than half this number were on the job at that date.25 To meet the labor requirements it was eventually necessary to hire large numbers of Irish workers—a measure that involved additional security risks. Finding construction sites alone was a tremendous problem, for each caisson was equivalent in size to a five-story building. Some of the caissons were built at the East India docks in London, but dry docks were not available for the entire project, and special basins had to be dug behind river banks along the tidal stretches of the Thames, where the work was partially completed. The banks were then dredged away and the units floated to wet docks for completion. Construction of the PHOENIXES was farmed out to some twenty-five contractors and eventually required about 30,000 tons of steel and 340,000 cubic yards of concrete in addition to other materials.26

In the construction of the Lobnitz pierheads, which got under way somewhat earlier, bottlenecks developed also. In December 1943 it was announced that only 15 pierheads could be delivered by D Day instead of the desired 23. Plans for the U.S. MULBERRY, which had called for 8 of these units, were therefore altered to provide for only 6. Because of prior commitments for the manufacture of landing craft and heavy engineering equipment it was necessary, as with other components, to split up the contracts among a large number of structural steel works in all parts of the country and to prepare entirely new shipbuilding sites for the launching of the pierheads. The same was true in the construction of the WHALE bridging for the roadways, and because of the wide distribution of the contracts it was almost impossible to obtain details of the manufacturing progress. About 240 firms were eventually involved in fabricating the materials for these units, using 50,000 tons of steel.27 When construction fell behind schedule in March and April, a U.S. Naval Combat Battalion (the 108th) was assigned to assist in the manufacture of this equipment.28

Shortages of one type or another also forced a reduction in the number of BOMBARDONS and in the number of ships for the GOOSEBERRIES. The number of BOMBARDONS was eventually cut from 113 to 93. In the case of the blockships the original

request for about 80 had brought loud protests from the Admiralty. When the admirals began to ponder the probable alternative, however, and visualized their landing craft smashing against the beach for lack of sheltered waters, they reconsidered, and more than 70 vessels—”mostly old crocks”—were eventually provided, about 25 of them by the U.S. War Shipping Administration and the remainder by the Ministry of War Transport.29

The towing problem finally proved as onerous as any of the other procurement difficulties, and in the final months before the invasion it was touch and go as to whether the lag in construction or the shortage of tugs would be the greater limiting factor. Until the end of April construction was the main worry, and in that month the Ministry of Production even provided a labor reserve to meet any emergency demands.30 But anxiety over the construction schedule was eased somewhat in May, and all the essential units were in fact ready by the time of the invasion, although it was after the middle of May before the first operational Lobnitz pierhead was turned over to its U.S. Navy crew at Southampton. Fortunately the commander of the American Force MULBERRY ordered a thorough test of the pierhead that included discharging a fully loaded LST. The trial run disclosed numerous defects, and men struggled night and day under the relentless driving of the indefatigable Captain Clark to make the necessary modifications.31

No amount of last-minute effort could surmount the towing problem, and in the end it proved to be the most critical bottleneck. As each piece of equipment was completed it had to be towed, in some cases hundreds of miles, to the place of assembly on the south coast of England, and the movement of 600-odd units to the far shore within a two-week period posed the biggest tow job of all. The construction delays that developed in the spring only aggravated the problem, for the failure to complete units on schedule had the effect of compressing all towing commitments into a shorter period. There was little point in meeting construction schedules, in other words, if tugs were unavailable to tow units across the Channel. Here was another example of a single shortage or shortcoming creating a bottleneck which threatened to frustrate the successful execution of an entire plan. It was estimated in February that 200 tugs would be needed for all invasion commitments, of which 164 were required for the MULBERRY units. An allocation of 158 tugs was made for the artificial ports sometime during the spring; but despite the rounding up of every suitable vessel that could be spared in both the United Kingdom and the United States, only 125 were made available by the time of the invasion. Of these, 24 were taken for temporary service with various types of barges, leaving a bare hundred to meet the MULBERRY requirements. In light of this shortage it was necessary on the very eve of the invasion to set back the target date for the completion of the MULBERRY installations on the far shore from D plus 14 to D plus 21.32

In the months just before the invasion the question of how long the artificial ports were to be kept in operation received increasing attention. This matter was closely related to the estimates as to when the deep-water ports could be captured and brought into operation. The original plans for the artificial ports provided that they were to remain effective for ninety days, by which time deep-water ports were expected to be restored and able to handle the required tonnages. As early as March, however, after the tactical plan was revised, further logistical studies of the maintenance problem after D plus 90 revealed that the capacity of the ports would almost certainly have to be supplemented by that of the MULBERRIES for an additional thirty days (to D plus 120) and, unless operations went extraordinarily well after D plus 120, even through the winter months. Even if the Loire and Brittany ports were captured by D plus 45, it was concluded, the difficulties likely to be met in restoring and operating the lines of communications made it doubtful that U.S. forces could be supported entirely through those ports by D plus 90, and the British would not be able to have the sole use of Cherbourg after that date, as planned. In any case, Cherbourg and the smaller Cotentin ports did not have sufficient capacity in themselves to maintain the British forces after D plus 90. Thus, if the Seine ports were not captured and put into operation by D plus 120 it would be essential to keep the MULBERRIES operating to maintain British forces. The chief administrative officer at SHAEF, Lt. Gen. Sir Humfrey M. Gale, therefore urged that measures be taken to extend the usefulness of these ports. This entailed the construction of additional PHOENIXES as reserves and also the strengthening of the ports during the summer so that they might withstand the winter gales. General Gale also requested that spare blockships be provided to replace any that might break up. The necessity for prolonging the life of the MULBERRIES was immediately accepted, and in March construction of an additional 20 PHOENIXES was therefore approved.33

Beach Organization

While the artificial ports represented one of the most ingenious engineering accomplishments and one of the invasion’s most expensive investments of resources, they were to remain largely untried expedients and therefore unknown quantities until they were subjected to the twin tests of battle and weather off the Normandy coast. Of equal importance to the logistic preparations for the operation was the organization of the beachs, across which all equipment and supplies would have to pass in the initial stages regardless of whether they were discharged at the pierheads and brought ashore via the roadways or were discharged from landing craft at the water’s edge.

Beach organization was to have special importance in OVERLORD because of the magnitude of the forces to be built up over the Normandy beaches and because of the extended time during which the beaches were to serve as major points of entry for both troops and supplies. The OMAHA and UTAH Beach areas were to be the bases for

the first continental lines of communications. The initial organization of these areas was therefore a vital preliminary step in the transition to the normal administrative organization provided by the Communications Zone.

Responsibility for developing and operating the first supply installations on the far shore was assigned to the engineer special brigades: the 1st Engineer Special Brigade at UTAH, and the Provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group, consisting principally of the 5th and 6th Brigades and the 11th Port,34 at Omaha where the MULBERRY was to be located. As attachments to the First Army in the first stages of the operation these units were required to prepare plans based on the engineer special brigade annex to the First Army plan, and the brigades accordingly carried out detailed planning for the early organization of the beach areas.

In the next chapter more will be said about the origins and development of the engineer special brigades. These organizations, mothered by the necessities of the frequently recurring amphibious operations of World War II, were specially trained and equipped to handle the technical organization of the beaches. As outlined by a First Army operations memorandum, their general mission was “to regulate and facilitate the landing and movement of personnel and equipment on and over the beach to assembly areas and vehicle parks, to unload cargo ships, to move and receive supplies into beach dumps, to select, organize, and operate beach dumps, to establish and maintain communications, and to evacuate casualties and prisoners of war over the beach to ships and craft.”35 In short, it was their duty to insure the continuous movement of personnel, vehicles, and supplies across the beaches in support of a landing operation. By “the beaches” was normally meant an area known as the “beach maintenance area,” which included the beach, the first segregated supply dumps inland, and the connecting road net, an area which usually did not extend more than three miles inland. At OMAHA the beach maintenance area included MULBERRY A and the minor ports in the vicinity.

The mission defined above involved a formidable list of tasks. Among them were the following: marking hazards in the vicinity of the beaches and determining the most suitable landing points; making emergency boat repairs; establishing medical facilities to collect, clear, and evacuate casualties to ships; controlling boat traffic; directing the landing, retraction, and salvage of boats; maintaining communications with naval vessels; marking landing beach limits; constructing and maintaining beach roadways and exit routes; establishing and marking debarkation points and landing beaches; unloading supplies from ships and craft; assisting in the removal of underwater obstructions; clearing beaches of mines and obstacles; erecting enclosures for guarding prisoners of war, and later evacuating them to ships; establishing army communications within the brigade and with other brigades and units ashore; constructing landing aids; maintaining liaison with senior commanders ashore and afloat; maintaining order and directing traffic in the beach maintenance area; providing bivouac, troop assembly, vehicle parking, and storage areas in the beach maintenance

area for units crossing the beach; regulating and facilitating the movement of unit personnel and equipment across the beach and insuring the rapid movement of supplies into dumps; selecting, Organizing, and operating beach dumps for initial reception and issue of supplies; selecting, organizing, and operating beach maintenance area dumps until relieved by the army; maintaining records showing organizations, materials, and supplies which had been landed; providing for decontamination of gassed areas in the beach maintenance area; maintaining an information center for units landing; operating emergency motor maintenance service to assist vehicles and equipment damaged or stranded in landing and requiring de-waterproofing assistance; providing local security for the beach maintenance area; and coordinating offshore unloading activities.

Many of these tasks obviously called for troops other than engineers. In this respect the name “engineer special brigade” is misleading, for while the core of the brigade consisted of engineer combat battalions, each brigade normally contained a body of Transportation Corps troops, such as amphibian truck companies and port companies, exceeding the size of the engineer component, plus quartermaster service and railhead companies, and ordnance, medical, military police, chemical, and signal troops. In addition, depending on its mission, each brigade was augmented by the attachment of a host of other units and special detachments such as bomb disposal squads, naval beach units, maintenance and repair companies, fire-fighting platoons, and surgical teams, which might raise its total strength to 15,000 or 20,000 men. The engineer special brigade was a hybrid organization, therefore, without standard composition. But it was exactly this feature which gave it the desired flexibility and permitted it to be tailored to any task in an amphibious operation.

Portions of the brigades were scheduled to follow closely on the heels of the initial assault waves. Within the first two hours of the landings they were expected to complete the initial reconnaissance and beach marking preliminary to the development of the beaches. In that period advance parties of engineer shore companies, signal teams, and naval units were to come ashore, survey beach and offshore approaches, plan the layout of beaches for landing points, roadways, and exits, install ship-to-shore signal stations, and erect beach markers. Within the next two hours additional elements of the brigade would arrive, remove mines and beach obstacles, decontaminate beach areas, lay beach roadways, complete exits, establish collecting and clearing stations, start controlling traffic, build stockades for the control of prisoners of war, assist stranded craft, control boat traffic, reconnoiter initial dump areas, and establish motor parks for first aid to water-stalled vehicles. By the end of the first day the brigade was to have established the brigade command post, a signal system, and assembly areas for troops, sign-posted all routes to the dumps, repaired roadways to the dumps, opened beach exits, organized antiaircraft defense, organized initial dumps for the receipt, sorting, stacking, inventory, and issue of supplies, and to have started unloading supplies. Initial beach dumps were to be in full operation by the end of the first day. Within the next few days supplies were to be routed to new dumps established farther inland in the beach maintenance area.

Brigade units were so grouped for the assault that they could operate independently in support of specific landing forces. Each brigade was broken down into battalion beach groups, each consisting of an engineer combat battalion reinforced with the service elements necessary to support the assault landing of a regimental combat team. The battalion beach groups were further subdivided into companies, each of which was to support the landing of a battalion landing team and operate a beach of about 1,000 yards frontage. Once a beachhead had been won and the buildup began, service troops of the battalion beach groups were to revert to their parent units and operate under brigade control. At this stage the brigades would move out of the narrow confines of the beach itself and begin to develop the beach maintenance area.36

The beach maintenance areas in effect would be microcosms of the future Communications Zone, for the brigades performed there most of the functions which the expanded Communications Zone later carried out in its base and advance sections. Each brigade was organized to move 3,300 tons of supplies per day from ships and craft into segregated dumps, and to provide the technicians and labor necessary to operate those dumps. As tonnage requirements increased, the capacity of the brigades was to be increased by the attachment of additional service troops, the improvement of beach facilities, and the development of local ports. As the MULBERRY was completed and the minor ports were rehabilitated, other service troops were to be utilized under brigade attachment to operate them. This initial development of the continental supply structure was to be carried out directly under the control of the First Army, which planned to relieve the engineer special brigades of responsibility for operating the dumps in the beach maintenance area as early as possible, using its own service units for this purpose. Eventually, of course, an army rear boundary would be drawn, and the rear areas and the brigades themselves would be turned over to the Advance Section, which would assume full responsibility for operating the embryo Communications Zone until the arrival of the Forward Echelon of that organization itself.37

The brigades were thus destined to play an essential role in initiating the development of the far-shore logistic structure. Since they were to land in the first hours of the invasion, while the beaches were still under fire, they were expected to perform both combat and service missions. That they were aware of their dual role is indicated by their reference to themselves as “the troops which SOS considers combat, and the combat troops consider SOS.”

Port Reconstruction

While the organization of the beaches and the MULBERRIES was important for the initial supply and build-up of forces on the Continent, the major burden of logistical support was expected to be progressively assumed by the larger deep-water ports as they were captured and restored to operation. The Normandy area had been chosen as the site of the landings not only because it possessed the

best combination of features required for an assaulting force, including proximity to the port of Cherbourg, but also because it lay between two other groups of ports—the Seine and Brittany groups—permitting operations to develop toward one or the other. The OVERLORD planners actually expected to rely completely on the Normandy and Brittany groups to develop the required discharge capacity for the Allied forces to D plus 90, and their plans for the rehabilitation of the ports in the lodgment area were made accordingly.

Operating the continental ports was to be a Transportation Corps function, restoring them was the responsibility of the Corps of Engineers. In the final Communications Zone plan this reconstruction work was given a priority second only to the development of beach installations.38 Planning for this task fell mainly to the Construction Division of the Office of the Chief Engineer, ETOUSA. U.S. participation with the British in this planning for port salvage and repair began in July 1942, immediately after the activation of the European theater, when American representatives attended meetings of the ROUNDUP Administrative Planning Staff. General Davison, chief engineer of the theater, suggested the magnitude of the task of rehabilitating the European ports when he said that it could “best be visualized by imagining what would have to be done to place back in operation the ports of Baltimore, Md., Portland, Me., Portland, Oreg., Mobile, Ala., and Savannah, Ga., plus ten smaller shallow-draft U.S. ports, assuming that these ports had been bombed effectively for two years by the R. A. F., then demolished and blocked to the best of the ability of German Engineer troops.”39 He recommended at that time the creation of specially organized and equipped engineer port construction companies reinforced by engineer general service regiments, and suggested that they be organized with personnel from large U.S. construction firms in the same way that American railways sponsored railway operating battalions. These proposals were forwarded to the War Department, and the theater’s needs in this respect were later met by the formation of units substantially along these lines.

Shortly thereafter preliminary studies were undertaken of the problems involved in reconstructing particular continental ports. No operational plan was available at this early date, and the North African invasion intervened to detract somewhat from planning for continental operations. But the ROUNDUP planning staff continued its work throughout the winter of 1942, and early in 1943 a subcommittee on port capacities in northwest Europe was organized under the chairmanship of a British officer, Brigadier Bruce G. White. This committee eventually extended its investigations to the ports along the entire coast of northwest Europe from the Netherlands to the Spanish border.

With the establishment of COSSAC in 1943 the port committee was renamed, but its membership remained virtually unchanged. U.S. engineers still did not know definitely which ports they would be responsible for, but a great amount of preliminary planning was accomplished, and a mass of pertinent data was collected on the various ports. Procedure for the initial occupation of ports was worked out,

and spheres of authority were defined, fixing responsibility for the Engineers, the Navy, and the Transportation Corps. In October 1943 a Joint U.S.-British Assessment Committee drew up an analysis of capacity for each port in western Europe. This included draft, tonnage, operating plant, and weather data. For example, a port reconstruction estimate for Brest, which was expected to be one of the major American points of entry as it had been in World War I, contained a full description of the port, statistics on its prewar operations, estimates of probable demolitions and obstructions and of the port’s capacity, plans for reconstruction, including a timetable for such work, a schedule for the intake of cargo, and a mass of technical data, including graphs, charts, maps, and photos. The Office of the Chief Engineer eventually prepared detailed plans before D Day for eighteen ports in the Normandy and Brittany areas.40

The actual work of rehabilitating the captured ports was to be assigned to organizations specifically designed for this purpose—port construction and repair groups, or PC&R groups. The headquarters and headquarters companies of these groups comprised a nucleus of specialists trained in marine construction, and included a pool of heavy construction equipment together with operators. This nucleus was to be supplemented by engineer service troops and civilians to provide the necessary labor and, according to need, by dump truck companies, port repair ships, and dredges. The port construction and repair group with its attachments thus constituted a task group, tailored for the specialized mission of restoring ports, much as the engineer special brigades were organized for the task of developing the beaches.

The equipment requirements for port reconstruction were difficult to estimate in advance, and little attempt was made to analyze and determine the requirements for individual ports. Instead a stockpile of materials was created, and estimates were made of the necessary repair and construction materials for a fixed length of quay, assuming a certain degree of destruction. These estimates were used to develop standard methods of repair that would be generally applicable to all types of repair work in French ports. Apart from an initial representative list of basic materials and equipment accompanying the repair groups, reconstruction materials were to be ordered to the Continent after the capture and reconnaissance of each port.

The reconnaissance was to be an important preliminary to the rehabilitation of a port, and the composition of the reconnaissance party and its specific mission were planned long in advance. Normally the reconnaissance team was to consist of representatives of the COMZ G-4, the Advance Section, the chiefs of engineers and transportation, and occasionally SHAEF. Upon capture of a port this team had the mission of surveying it for damage to facilities, locating sunken ships and other obstructions, preparing bills of material, deciding the extent and methods of repair, determining the availability of local or salvageable materials, and arranging for the phasing in of the required PC&R units for the actual reconstruction work. The reconnaissance team would therefore determine the degree of

rehabilitation to be undertaken and the initial course of the reconstruction program.41

Several factors had to be taken into consideration in planning the reconstruction of a port and arriving at its estimated capacity. Among them were its prewar capacity and use, the known and assumed damage to the port when captured, and the ability and availability of Army and Navy Engineer units. The damage factor was by far the most variable and unpredictable. For planning purposes, however, certain assumptions had to be made. It was figured, for example, that up to 90 percent of the existing suitable quayage would be initially unusable. Of this, half was expected to be in such condition that it could be repaired fairly quickly or in a matter of days, and the remainder was expected to require varying amounts of work or be beyond repair in any reasonable time. It was also assumed that all craft in the harbors would be sunk, cargo-handling equipment destroyed and tipped into the water, most of the buildings in the port area demolished, road and railway access blocked with debris, entrances to ports and lock chambers blocked and all locks demolished, and water and electric services broken. In addition, it was anticipated that extensive dredging would be necessary in some cases to allow the entrance of anything but the shallowest-draft vessels into waters that had undergone four years of silting.42

By D Day detailed plans were complete for the rehabilitation of Cherbourg, Grandcamp, Isigny, St. Vaast, Barfleur, and Granville in the Normandy area, and of St. Malo in Brittany. (See Map 4.) Cherbourg was the only large port in this group and was the first major objective of the American forces. Except for Granville, all the others were very small and possessed discharge capacities of only a few hundred tons per day. Another Normandy port—Carentan—had been rejected as having a potential too meager to warrant the effort required for its rehabilitation. All were scheduled to be opened by D plus 30, and their restoration was therefore the responsibility of the Advance Section. The schedule for the opening of these ports and their estimated initial discharge capacities were as follows:43

| Port | Opening Date | Tonnage at Opening |

| Isigny | D plus 11 | 100 |

| Cherbourg | 11 | 1,620 |

| Grandcamp | 15 | 100 |

| St. Vaast | 16 | 600 |

| Barfleur | 20 | 500 |

| Granville | 26 | 700 |

| St. Malo | 27 | 900 |

Headquarters, Communications Zone, meanwhile made plans for the later reconstruction of the Brittany ports, the schedule for which was as follows:

| Port | Opening Date | Tonnage at Opening |

| Brest | D plus 53 | 3,240 |

| Quiberon Bay | 54 | 4,000 |

| Lorient | 57 | 800 |

Although plans were made for phasing equipment and the required Engineer and TC units into the Brittany ports and a schedule was written for their opening, the ports of Normandy naturally enjoyed

the first priority in development, and the plans for its six ports plus St. Malo were worked out in much greater detail before D Day.

Of these seven ports all except Cherbourg were tidal, drying out completely at low water. Most of them had a mud- or sand-bottomed basin and two or three quays which were entirely tidal, and at high water they could accommodate only vessels drawing a maximum of thirteen or fourteen feet.44 In this respect they were typical of the French ports along the English Channel and the Bay of Biscay, where tide and weather conditions had required the construction of massive breakwaters, locked basins, and channels, in contrast with ports in the United States where such elaborate paraphernalia were unnecessary.

St. Malo was known to have a large amount of locked quayage, but it could be blocked easily and had poor rail clearance facilities. Consequently it was considered suitable only for operations employing amphibian trucks (DUKWs) for at least the first ninety days. Granville, on the west coast of Normandy, had somewhat better facilities than the other ports. In addition to quayage in its Avant Port, where vessels could “dry out” (that is, beach at ebb tide, unload, and then float out on the next tide), Granville had a locked or “wet” basin with berthing facilities that could accommodate seven 4,000-ton ships of 14-foot draft simultaneously. The Allies did not count on immediate use of the wet basin, for the enemy was expected to destroy the lock gates and sink blockships in the chamber. But with the removal of obstacles they planned to dry out coasters at the inner quays and to utilize Granville for the reception of coal and ammunition.45

Although the movement of craft into and out of these “minor” ports would be restricted by the tide, they at least offered some protection from stormy weather, and the desperate need for discharge capacity in the early phases appeared to warrant bringing them into use. The total discharge capacity of these six minor ports was not great. At D plus 30 it was scheduled to be 4,500 tons per day. At D plus 60, with the small Brittany port of Lorient added, they were to develop a capacity of 7,700 tons, and at D plus 90, 10,650 tons.46 As for clearance facilities, all the ports had good road connections, but only Granville had first-class rail clearance. All the other minor ports would have to be cleared by motor transport.

The division of responsibilities and the procedure for restoring and operating the ports were defined in minute detail. Work of a more strictly marine nature was assigned to the British and U.S. Navies, the former assuming responsibility for minesweeping the harbors, and the latter for removing obstacles such as sunken blockships in the channels and along quays and for making hydrographic surveys. Reconstruction or enlargement of discharge facilities was an Army Engineer responsibility, and the plans for the first six weeks were written in full detail by the Advance Section. The ADSEC plan provided that a reconnaissance party should debark on D plus 3 and successively examine the condition of port facilities at all the minor ports, beginning at Isigny. As these preliminary surveys were completed, the commanding officer of the port construction and repair group was to draw up a definite

reconstruction job schedule to meet the planned port capacity. The first repair work was to get under way on D plus 6 at Isigny and Grandcamp with the arrival of the headquarters of the 1055th PC&R Group and work parties consisting of advance elements of the 342nd Engineer General Service Regiment. Upon completion of its task the entire group was to proceed in turn to St. Vaast, Barfleur, Granville, and St. Malo for similar projects.47

While repair and construction might continue for several months, as at Cherbourg, the Transportation Corps was to start operating the ports as soon as the unloading of cargo could begin. For this purpose the 11th Major Port was attached to the Provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group at OMAHA to handle pierhead operations at the MULBERRY and to operate the small ports of Isigny and Grandcamp.48 It was also to furnish a detachment to the 1st Engineer Special Brigade to operate the small port of St. Vaast (and eventually Carentan, as it turned out) in the UTAH area. The operation of Barfleur, Granville, and St. Malo was to be supervised by the 4th Major Port at Cherbourg. Another major port, the 12th, was to take over the operation of Granville and the ports in the vicinity of St. Malo. The Allies hoped that St. Malo itself could be developed to a capacity of 3,000 tons per day, and the St. Malo area, including Cancale and St. Brieuc, to 6,000 tons, and thus relieve beach operations at OMAHA and UTAH. They counted on the St. Malo development to provide all the tonnage capacity necessary to sustain the Third Army, and possibly even to debark some of its personnel.49

Since the minor ports possessed only limited capacities and were rather uneconomical to operate, their development was never intended to be more than a stop-gap measure designed to meet a portion of the discharge requirements in the period before the full potential of the larger ports was realized. Plans for their restoration were completely overshadowed by those made for Cherbourg. This port was expected to handle 6,000 tons at D plus 30, 7,000 at D plus 60, and 8,000 at D plus 90, and was to exceed in capacity the combined tonnage of the six minor ports throughout the first 60 days. Even Cherbourg was to have but a temporary importance for U.S. forces, for plans were tentatively made to turn the port over to the British after a short time, and to route the major portion of American cargo through the Brittany ports and later through others farther up the Channel. Cherbourg, however, played a wholly unexpected role in the support of U.S. forces and eventually ranked as one of the big three of the continental ports.

The relatively high tonnage targets for Cherbourg appear optimistic in view of the port’s peacetime performance. Cherbourg, home of the French luxury liner Normandie, had been primarily a passenger port and a naval base. It had handled an average of less than 900 tons per day, ranking twenty-second among all the

Aerial View of Cherbourg. Digue de Querqueville, 1; Naval Arsenal, 2; Nouvelle Plage, 3.

French ports in cargo tonnage. Warehouse and storage facilities were correspondingly small, and cargo-handling equipment was in keeping with a port that specialized in passenger trade rather than freight.50

Built up over a period of two hundred years, Cherbourg’s port facilities were essentially completed in the early 1920’s, but at the outbreak of World War II they were still undergoing improvements designed to facilitate the berthing of the largest ocean liners. Cherbourg’s harbor is artificial, consisting of a double set of breakwaters which form both an inner and outer roadstead, one known as the Petite Rade and the other as the Grande Rade. The only facilities in the outer harbor consisted of tanker berths along the Digue de Querqueville, the western arm of the outer breakwater, which the Allies intended to restore for the bulk reception of POL. Otherwise the outer harbor was chiefly an anchorage, affording some protection to shipping, but too rough in stormy weather to permit lighterage operations. The inner roadstead was workable in all weathers. Both had sufficient depth at all variations of the tide to receive the largest ocean liners. The Petite Rade, or inner harbor, contained almost all of the port’s berthing

facilities, most of which were concentrated along the western and southern sides. The entire western side of the port was occupied by the great Naval Arsenal, consisting of repair shops, drydocks, and maintenance facilities grouped around its three basins—the Avant Port, Bassin Charles X, and Bassin Napoléon III—and including additional berthing facilities at the Quai Homet and along the Digue du Homet, the western jetty enclosing the inner harbor. This area alone was expected to provide discharge facilities for 5 Liberty ships, 2 train ferries, 24 coasters, and 2 colliers.

Just south of the main arsenal installation lay the seaplane base and its three small basins—the Bassin des Subsistences, Avant Port, and Port de l’Onglet—which were expected to provide berths for 13 coasters. Adjoining this area to the southeast was a broad bathing beach known as the Nouvelle Plage, believed to be ideal for unloading vehicles from LSTs. Immediately to the east of this beach and directly in the center of the harbor lay the entrance channel to the Port de Commerce, consisting of two basins (the Avant Port de Commerce and the Bassin à Flot) which jutted deeply into the heart of the city. These two basins were planned to accommodate 17 coasters and 2 LSTs with tracks for the discharge of railway rolling stock.

Dominating the entrance to these basins was the large Darse Transatlantique, the deepest portion of the harbor, where the Quai de France and the Quai de Normandie provided berthing for large passenger liners, and where discharge facilities were now to be provided for 7 Liberty ships, 2 LSTs carrying rolling stock, and a train ferry. A large tidal basin in the southeast corner of the port was believed to be suitable for the reception of additional vehicle-carrying LSTs.

In all, the port was expected to provide berths for 12 Liberty ships, 18 LSTs (6 of which would deliver rolling stock), 56 coasters, 2 tankers, 3 colliers, and 1 train ferry. In addition, the harbor of course offered alternative anchorage for other shipping which could be worked by lighters—either DUKWs or barges. When these facilities were fully developed the port was expected to attain a daily discharge capacity of 8,000 tons.51

Despite the assumption that the enemy would carry out a systematic destruction of Cherbourg before surrendering it, Allied planners hopefully scheduled the opening of the port and the start of limited discharge operations three days after its capture. The procedure for restoring Cherbourg and bringing it into operation was similar to that described for the minor ports. In the three days following its capture the Royal Navy was to sweep mines from the harbor, and U.S. naval salvage units were to begin removing blockships. Rehabilitation of the port’s inshore facilities meanwhile was to be undertaken by the 1056th Port Construction and Repair Group, with attached elements of an engineer general service regiment, an engineer special service regiment, and an engineer dump truck company. A reconnaissance party of this organization was scheduled to debark at UTAH Beach on D plus 5, proceed to the port on D plus 8, and immediately establish priority of debris clearance in the port area. In conjunction with the Navy salvage party, it was to establish priority for ship salvage and removal operations for approval of the port commander. It would also decide on the

schedule for initial quay repair jobs and examine locations where initial cargo discharge from DUKWs, barges, and LSTs could begin.

The actual rehabilitation work was to begin the second day after capture (D plus 10), early priority being assigned to such projects as debris clearance from the Quai Homet area, preparation of LST landing sites on the Nouvelle Plage, and construction of a tanker berth at the Digue de Querqueville on the west side of the outer harbor. By D plus 11 progress on these first projects was expected to be sufficient to permit the unloading of about 1,600 tons of cargo by a combination of DUKWs and barges unloading from Liberties and coasters, the unloading of at least one docked coaster direct to a usable quay, and the discharge of 840 vehicles per day from LSTs at the Nouvelle Plage. By the fourth day the Allies planned to boost unloading to about 3,800 tons, and by the tenth to about 5,000 tons. The great bulk of this discharge was to be carried on by DUKWs and barges working Liberty ships and coasters at anchor. In fact, only one coaster berth and four Liberty berths were expected to be in use at the end of the first month of operations, and direct ship-to-shore discharge consequently was expected to account for only a fraction of total discharge in these early weeks.

Some conception of the minute detail and scope of preparations for the rehabilitation of the ports can be gained from a glance at the engineer reconstruction plans. In sheer bulk the ADSEC engineer plan outweighed that of all other services combined, comprising two thick volumes of data on the Normandy ports. These included an analysis of their facilities, a schedule of reconstruction, and a detailed catalogue of equipment and material needs. The length and width of every quay, the depth of water alongside, the nature of the harbor bottom, the number and types of cranes, the capacities of berths, road and rail clearance facilities, all were set down in enclosures to the plan. Next, every reconstruction project was defined and given a priority, and units were phased in to undertake these jobs in prescribed order on specific days. On the basis of the above data, the ADSEC planners estimated the type and number of craft that could be accommodated and the tonnage discharge targets that should be met on each day by the beaching of vessels, by DUKW, coaster, and barge discharge, and by direct unloading from either coasters or deep-draft ships. In meticulous detail they drew up lists of materials needed in the reconstruction, specifying the exact quantities of hundreds of items from bolts and nails, ax handles, valves, washers, and turnbuckles in quantities weighing only a few pounds, to heavy hoists, tractors, sandbags, and cement, weighing many tons. The ADSEC plan scheduled twenty-one projects to be started by D plus 31, establishing the days and priority in which they were to be undertaken, specifying the crews available for each job, and the time in which they were to be completed. While it was unlikely that this clocklike schedule would be followed to the minute in view of the many unforeseeable circumstances, plans nevertheless had to be made on the basis of the most optimistic forecast of tactical progress in order that logistical support should not fall short of requirements.

A picture of the personnel and equipment required to operate the ports is afforded by the Transportation Corps plan. For the beach areas alone, including the minor ports in the vicinity, the basic units

allotted included 1 major port headquarters (the 11th), 10 port battalion headquarters, 48 port companies, 1 harbor craft service company, 7 quartermaster truck companies, and 19 amphibian truck companies. Cherbourg was assigned 1 port headquarters (the 4th), 6 port battalion headquarters, 20 port companies, 2 harbor craft service companies, 1 port marine maintenance company, and 4 amphibian truck companies. Floating and nonfloating equipment needs at the beaches included 950 DUKWs, 16 tugs, 7 sea mules, 66 barges, and varying numbers of cranes, tractors, trailers, and various types of boats. Cherbourg was to be furnished 200 DUKWs, 176 barges, 38 tugs, 11 sea mules, a floating drydock, and various crane barges, landing stages, and boats. These items were solely for harbor use. On shore there were additional requirements for 69 cranes of various sizes and types, 30 derricks, plus conveyors, trailers, and tractors.52 In addition to these elaborate plans for the development of the port’s discharge capacity the Communications Zone plan scheduled the introduction of railway equipment to meet the corollary requirement of developing Cherbourg’s clearance facilities.

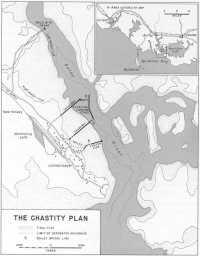

Plans for the rehabilitation of the Brittany ports were written in far less detail, since the final decision regarding the development of that entire area was to depend on circumstances following the battle of Normandy. No specific units were named to handle reconstruction and operation of the Brittany ports, although estimates were made as to types of units and quantities of equipment needed to bring Brest, Quiberon Bay, and Lorient into operation. Plans for the Brittany ports had undergone several alterations. Before April 1944 they contemplated the development of St. Nazaire, Morlaix–Roscoff, St. Brieuc, Concarneau, and Le Pouliguen in addition to St. Malo, Lorient, and Brest. With the acceptance of the Quiberon Bay (CHASTITY) project early in April the final COMZ plans provided for the restoration of only Lorient, Brest, and St. Malo with its adjacent beaches at Cancale, and the development of Quiberon Bay. These four ports were planned to develop a daily capacity of about 17,500 tons.53

The plan that finally evolved for the development of Quiberon Bay differed substantially from the original concept. A study of the area revealed that while the bay itself provided ample anchorage of required depth, and while the inland transportation net could be developed to needed capacity, bad weather conditions barred the use of lighters to unload ships in the winter. The development of deep-water berths was likewise found to be impracticable since the wide tidal range and the gentle slope of the sea bottom near the shore would have required the construction of extremely long piers. The answer to the problem lay rather in the Auray River, which flows into Morbihan Gulf and Quiberon Bay from the north. This estuary had scoured a narrow channel almost eighty feet deep near the small fishing village of Locmariaquer, providing deep and sheltered water where large ships could lie alongside piers or landing stages and discharge their cargo, and anchorage from which lighterage operations could be safely conducted. (Map 8)

As finally evolved the plan called for moorings for thirty deep-draft vessels in the deep-water “pool,” and a landing stage designed to float up and down with the

Map 8: The CHASTITY Plan

tide providing berths for five Liberty ships at the edge of the deep-water anchorage. Two fixed-construction causeways were to extend across the tidal flat from the shore to the landing stage. In addition a floating pier, constructed of naval lighterage pontons, was planned south of the landing stage, and an existing mole with rail connections farther north was to be extended into deep water to make possible the handling of heavy lifts. These facilities were expected to give the port a capacity of 10,000 tons per day.

The CHASTITY project had much to commend it. Among its attractive features was the fact that it made the most of an existing natural advantage—that is, sheltered water—and that it required only a fraction of the labor and materials that were to go into the artificial ports or MULBERRIES. Furthermore, no special design or manufacturing problems were involved, for all the components of the piers and landing stage consisted of standard materials and equipment already available.54

The port capacities given above were those embodied in the final OVERLORD plan, and represented substantial revisions made in March and April 1944, when it was realized that additional discharge capacity would be needed. As plans stood at that time the port situation remained very tight for both the OVERLORD and post-OVERLORD periods and imposed a considerable rigidity in logistical plans, for every port and beach would be forced to work to capacity. In fact, it was estimated in March that port capacities would actually fall short of U.S. tonnage needs at D plus 41. By that date the daily requirements would total approximately 26,500 tons, while discharge capacities were estimated to reach only 20,800.55

In March and April the entire problem had been restudied with a view toward making up the recognized deficiencies. The substitution of the CHASTITY project for St. Nazaire and the other minor Brittany ports was a partial solution. But the Brittany ports were not scheduled to come into use until after D plus 50. Measures were also taken in March to prolong the life of the MULBERRIES. In addition, estimates were revised, first, of the time required to capture the ports, and second, of the time required to open the ports. At the same time the estimates of their tonnage capacities were increased. Cherbourg’s maximum capacity, for example, was boosted from 5,000 to 8,000 tons. Its capture was more optimistically scheduled for D plus 8 instead of D plus 10, and the time required for its opening changed from ten to three days. Cherbourg was thus scheduled to receive cargo on D plus 11 instead of D plus 20, and in greater volume. As a result of similar alterations in the schedule for the other ports the planned tonnages of the Normandy ports were increased by over 4,000 tons per day.

Two encouraging developments made these revisions possible. Experience in the Mediterranean, particularly at Philippeville and Anzio, indicated that ports could be brought into operation and capacities developed much faster than had been originally believed possible. In addition, both the British and Americans had greatly improved their equipment and engineering techniques for the reconstruction of destroyed ports. All these developments were reflected in the final plans. The Normandy and Brittany port plans as they

Beach and Port Plans for Operation OVERLORD

| Port or Beach | Opening Date | At Opening | Discharge Capacity (in Long Tons): | |||

| D plus 10 | D plus 30 | D plus 60 | D plus 90 | |||

| Total | 14,700 | 27,200 | 36,940 | 45,950 | ||

| OMAHA Beach | D Day | 3,400 | 9,000 | 6,000 | 5,000 | 5,000 |

| UTAH Beach | D Day | 1,800 | 4,500 | 4,500 | 4,000 | 4,000 |

| Quinéville Beach | D + 3 | 1,100 | 1,200 | 1,200 | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| Isigny | D + 11 | 100 | 0 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

| Cherbourg | D + 11 | 1,620 | 0 | 6,000 | 7,000 | 8,000 |

| MULBERRY A | D + 12 | 4,000 | 0 | 5,000 | 5,000 | 5,000 |

| Grandcamp | D + 15 | 100 | 0 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

| St. Vaast | D + 16 | 600 | 0 | 1,100 | 1,100 | 1,100 |

| Barfleur | D + 20 | 500 | 0 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| Granville | D + 26 | 700 | 0 | 700 | 1,500 | 2,500 |

| St. Malo | D + 27 | 900 | 0 | 900 | 2,500 | 3,000 |

| Brest & Rade de Brest | D + 53 | 3,240 | 0 | 0 | 3,240 | 5,300 |

| Quiberon Bay | D + 54 | 4,000 | 0 | 0 | 4,000 | 7,000 |

| Lorient | D + 57 | 800 | 0 | 0 | 800 | 2,250 |

were written into the final COMZ and ADSEC plans in May are summarized above.56

These final estimates were regarded as adequate to meet the needs of U.S. forces in the first three months. But even these schedules were subject to last-minute revision. With the discovery in May of an additional German division in the Cotentin peninsula the tactical plans of the VII Corps had to be amended only a few days before D Day. The estimated capture date of Cherbourg was changed from D plus 8 to D plus 15, with a resultant loss of tonnage, estimated to total 34,820 tons for the period D plus 11 to D plus 25.57

Unfortunately the anxieties and uncertainties attending port planning were not to end with the establishment of a lodgment on the Continent. Port discharge was to become one of the most frustrating limiting factors of the continental operation and was to persist as a major logistic problem for fully six months after the landings.

Troop Build-up and Replacements