Chapter 10: Launching the Invasion: Organizing the Beaches

Tactical Developments in June

On the morning of 6 June 1944 five task forces, three British and two American, under continuous air cover and following air and naval bombardment, assaulted the coast of Normandy and won continental beachheads.1 On four of the beaches opposition ranged from light to moderate. On the fifth, OMAHA, unexpectedly strong enemy forces delayed the V U.S. Corps in its advance inland and inflicted heavy casualties. In the UTAH sector the VII U.S. Corps, assisted by two airborne divisions dropped six hours before the seaborne attack, secured a firm beachhead by the end of D plus 1. At the eastern end of the assault area British and Canadian forces initially enjoyed rapid success and pushed inland toward Caen and Bayeux. Although the two American landings remained unlinked for several days, it was apparent by the end of D plus 1 that the Allies had succeeded in the initial assault.

The Supreme Commander had made a significant change in the scheduled landings at the eleventh hour. The date for the attack had been set as 5 June, when moon and tidal conditions most satisfactorily met the requirements of all components of the invasion force. Loading of the assault elements was completed on 3 June, and certain vessels of the Force U Fire Support Group sailed from Belfast the same day, other convoys getting under way that evening. The night of 3–4 June was clear, but the wind was rising and the Channel was choppy.

General Eisenhower was given an unfavorable forecast for D Day that evening, and early on the morning of 4 June he made the difficult decision to postpone the assault twenty-four hours. Convoys that had already departed were immediately notified by prearranged radio signal, and destroyers were also dispatched to overtake them. Some of the ships and craft were forced to return to ports; others simply reversed their course and backtracked for the next twenty-four hours.

The decision to postpone D Day was based on a forecast of more moderate seas and more favorable flying conditions between the afternoon of the 5th and the afternoon of the 6th. But the forecast for the subsequent period was not encouraging, for it promised an indefinite period of unfavorable weather. The Supreme Commander was therefore faced with the necessity of making a further decision on whether to initiate the operation on 6 June

or order a further delay. To order a delay would have meant a postponement of two weeks, since the required conditions of tide and moon would not occur again until that time. The invasion had already been postponed a month in order to permit enlargement of the assault forces and widening of the assault front. Another delay of two weeks would shorten the summer campaign season still more. Furthermore, some of the assault forces were already on the Channel, others were briefed and embarked, and additional follow-up units had already moved into the marshaling areas. The entire mounting machinery was already in full operation. Early on the morning of 5 June General Eisenhower directed that the assault be launched the following day.

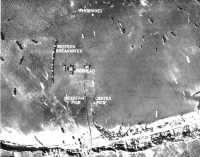

On the morning of 5 June the seventeen convoys of Forces O and U, comprising nearly 2,000 ships and craft, started across the English Channel. The voyage itself was uneventful, although the weather continued unfavorable. The convoy routes led through minefields, but well-marked lanes had been swept through them. Convoys began arriving in the transport area, approximately twelve miles off the beaches, about midnight. The moderate sea, greater at OMAHA than at UTAH, created some difficulty in transferring assault teams from the transports to the small landing craft, and there was much seasickness. By dawn of 6 June hundreds of craft in the invasion armada lay off the French coast, assembled in the transport area. At approximately midnight, 5–6 June, RAF bombers had ranged along the entire invasion coast striking at heavy coastal batteries and other specific targets. Shortly thereafter, beginning at H minus 6 hours, paratroops of the 82nd and the 101st Airborne Divisions began dropping astride the Merderet River and to the rear of the inundated areas to seize the causeway exits and thus facilitate the later landings of the 4th Infantry Division in the UTAH sector. Immediately preceding the seaborne landings came the preparatory naval and aerial bombardments. At H minus 40 minutes warships of the bombardment groups began firing on enemy shore batteries on both OMAHA and UTAH Beaches, and as the assault craft started for the beaches the naval bombardment was augmented by the fire from fire-support craft, variously equipped with rockets and small guns. In the meantime aerial bombardments hit both beaches. At UTAH Beach medium bombers of the Ninth Air Force struck at specific beach targets without destroying beach fortifications. The bombing by the Eighth Air Force planes at OMAHA meanwhile was foiled by bad weather. Forced to use blind-bombing equipment and to take special precautions against hitting friendly troops in the assault craft, bombers at OMAHA released their loads too far inland to be of any direct assistance to the assaulting infantry.

U.S. forces in the OMAHA sector badly needed an effective air effort. Initial assault units of the V Corps, comprising elements of the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions and Rangers, touched down on OMAHA Beach at approximately 0635, and met unexpectedly heavy opposition. As a result of the rough sea many craft foundered, amphibian tanks were swamped, and landing craft missed their assigned beaches. Heavy enemy fire prevented the proper clearance of beach obstacles. The landings lost all resemblance to the plan, and the beaches soon became congested with disabled and burning vehicles and with troops immobilized by enemy fire. Landing operations were finally halted

until enemy fire could be neutralized. With the help of close-range naval fire the situation was gradually brought under control and landings were resumed. Units gradually reorganized themselves and pushed up the slopes to destroy enemy positions behind the beaches. But for many hours the situation at OMAHA was uncertain, and at the end of D Day units of the V Corps clung precariously to a hard-won strip of land less than 3,000 yards deep.

At UTAH Beach, meanwhile, seaborne elements of the VII Corps carried out their landings with contrasting ease. Troops of the 4th Division touched down on UTAH at approximately 0630, rapidly overcame relatively weak enemy opposition, crossed the causeways spanning the inundated areas, and pushed inland as much as 10,000 yards on D Day. The initial success of the 4th Division was partly attributable to the naval and air bombardment, which was more effective than at OMAHA, but also to the assistance rendered by the airborne units that had dropped during the night. Both airborne divisions suffered heavy losses in men and matériel and were able to bring only a portion of their full strength to bear in the fighting on D Day. By striking suddenly in the enemy’s rear, however, the airborne infantry created confusion in the enemy’s ranks and secured the western exits of the inundated area, thus rendering much easier the initial task of the seaborne elements.

But there was little cause for optimism on either beach as D Day drew to a close. The V Corps held only a tenuous beachhead at OMAHA. At UTAH, in spite of the successful landings of the seaborne elements, heavy fighting with high losses had been going on inland. Both airborne divisions had had scattered drops, the 82nd Division had not linked up with the seaborne forces and had no communications with other units, and some of its elements were completely isolated west of the Merderet River.

Both V and VII Corps pressed forward on D plus 1, the VII Corps clearing out scattered enemy holdings and rounding out its lodgment, the V Corps enlarging and securing its precarious toe hold. In the next few days the V Corps pushed inland to capture the high ground between the beaches and the Aure River, and by 10 June it had pushed west to the Vire and south just beyond the Forêt de Cerisy. In the UTAH sector the VII Corps extended its beachhead north, west, and south. In the north the 4th Division fought through heavily fortified headland batteries toward Montebourg; in the west the 82nd Airborne Division established a bridgehead over the Merderet after hard fighting; and in the south the 101st Airborne Division crossed the lower Douve and established contact with the V Corps. Carentan, vital communications link with the eastern beachhead, was not captured till 12 June.

After the capture of Carentan VII Corps turned its attention to its major objective, Cherbourg. Its first move was to strike westward to cut the peninsula and prevent the enemy from reinforcing his forces in the north. The stroke was accomplished by the veteran 9th Division during the night of 17–18 June. The corps then quickly organized its attack toward Cherbourg and on 19 June pushed rapidly to the north its three divisions (the 4th, 79th, and 9th) converging on the port. Temporarily checked at the prepared defenses which ringed Cherbourg on the south, the three divisions, with the aid of an intensive air preparation on 22 June, finally broke through and captured the port on the 27th.

No full-scale attacks had been attempted on the remainder of the American

Map 11: Tactical progress: 6–30 June 1944

front after 20 June, and only minor advances were made in efforts to deepen the lodgment southward. Two additional corps meanwhile joined First Army forces. The VIII Corps, becoming operational on 15 June, assumed control of the divisions released from VII Corps (90th Infantry, 82nd and 101st Airborne) at the base of the Cotentin peninsula on 19 June and undertook to clear the area southward toward La Haye-du-Puits. Meanwhile the XIX Corps took over a sector between V and VIII Corps on 14 June, with the 29th and 30th Infantry Divisions under its command. It immediately took steps to consolidate the beachhead junction in the Carentan–Isigny area, and then drove southward astride the Vire River. On about 21 June, their supply limited by the priority given the Cherbourg operation and by an interruption of unloadings at the beaches, all three corps assumed an active defense, and only minor gains were made toward the city of St. Lô.

At the end of June, although advances were somewhat behind schedule, the First U.S. Army was firmly established on the Continent. (Map 11) It had cleared the Cotentin, captured a major port, and extended its holding inland from OMAHA Beach to a depth of about seventeen miles. Nowhere on the American front had the enemy been able to gather sufficient strength to threaten the continental beachhead seriously.

OMAHA Beach on D Day

The story of supply operations in the first weeks of the continental operation is almost exclusively that of the organization of the beaches and beach maintenance

Map 12: OMAHA beach and beach maintenance area

areas, and of the part played by the engineer special brigades.2

In the V Corps sector the beach known as OMAHA was a 7,900-yard flat stretch of sand running from Pointe et Raz de la Percée to Colleville-sur-Mer, backed by hills and flanked by steep rocky cliffs rising from the water’s edge. (Map 12) It had a great tidal range and a large tidal flat. Between the low- and high-water marks the flat consisted of hard, well-compacted sand, with shale outcroppings on the flanks. Its average width was 300 yards, and it was broken in places by a series of runnels, two and a half to four feet deep, located 50–100 yards from the high-water mark. This wide tidal flat was a key feature of OMAHA and figured importantly in both the invasion plans of the Allies and the defensive plans of the Germans. The enemy had assumed that the width of the beach was too great to permit a landing at low tide and had built his defenses to guard against a high-tide assault. These defenses consisted of rows of obstacles covering the tidal flat, including bands of steel hedgehogs, heavy log stakes driven into the sand at an angle pointing seaward, and huge iron gate barriers known as Element C or Belgian gates, often with Teller mines lashed to them. They were no barrier to men landing at low tide, but they created a great hazard for craft approaching shore after the tide began to rise. For this reason the Allies planned a low-tide assault, counting on heavy air and naval bombardment to neutralize shore defenses sufficiently so that men could cross the beaches and demolition teams could

destroy the obstacles before the tide again came in.

Above the tidal flat the OMAHA terrain varied greatly. Along most of its length the beach sloped upward sharply for about twenty-five yards. On the eastern half this rise ended in an extended shingle pile of small rounded stones. On the western end a wood and masonry sea wall rose from six to twelve feet high. Concertina wire was strung along both the shingle pile and the wall. A road ran along most of the beach, hard-surfaced at the western end, but hardly more than a trail through the dunes farther east. Two of the roads leading inland off the beach were blocked by antitank ditches, and fields were sown with mines or falsely marked with warning signs.

Just beyond this strip above the tidal flat the ground rose more precipitously, particularly at the western end, with most of the beach backed by hills of from 80 to 130 feet. Bisecting these hills and cliffs were several draws which served as natural exits from the beaches. Starting at the western end of OMAHA they were designated with letter-numbers as follows: D-1, which had one of the best roads from the beach, leading to the town of Vierville-sur-Mer, about 600 yards behind the beach; D-3, which also had a good road, leading to St. Laurent-sur-Mer, about one mile inland; E- 1, which had a narrow cart track leading up a steep hill on the west and also southwest to St. Laurent; E-3, which had a dirt road winding through thick scrub growth and trees to the small town of Colleville; and the easternmost exit F-1, which had only a cart track and was the poorest of all.

As the logical routes of advance from the beaches inland, these exits had great importance to both the defenders and the assaulting forces. They were well defended, therefore, with gun emplacements set into the sides of the hills, together with pillboxes, dugouts, and interlocking trenches designed to cover the exits as well as the beaches themselves. Artillery and mortar positions were placed well behind the high ground.

Inland from these hills and bluffs a rolling plateau extended two to four miles, descending to the low, swampy Aure River valley. The road network of this area was based on two highways. One (Route B), less than a mile from and roughly parallel to the beach, ran through the three principal villages immediately back of the beaches (Vierville, St. Laurent, and Colleville). The other was the Isigny–Bayeux road, roughly parallel and a few miles farther south. The area from the beaches to the Aure River comprised the planned beach maintenance area, and its organization for supply was the responsibility of the Provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group.

Infantry assault teams were scheduled to land in the first wave to overcome resistance on the beaches. Joint Army-Navy demolition teams were to follow closely behind and, under the infantry’s protection, blow gaps in the maze of obstacles on the tidal flat. But plans went wrong from the beginning. Most of the initial landings took place too far to the east, and some demolition teams landed before the infantry. The first waves suffered heavy casualties from enemy automatic small arms fire and artillery, and the infantry were thus unable to afford the necessary protection to the demolition teams. Assault engineers consequently were forced to work on a tidal flat drenched with fire. Only five of the sixteen teams came in on their assigned beaches, and they had only six of the sixteen

tank dozers scheduled to land, five of which were shortly knocked out. They were able to clear only five narrow lanes instead of the sixteen 50-foot gaps planned, and of the five only one proved very useful. Through these inadequately cleared gaps the succeeding waves tried to pour onto the beach.

The landings of assault elements were unnecessarily marred by the repetition of an error which had been detected as early as the first DUCK exercise in January. Troops as well as vehicles were overloaded in the assault, often with tragic consequences. While there is no precise record of the load men carried, it is clear that the equipage of the individual rifleman weighed at least sixty-eight pounds. The additional personal items not specified in orders which many men are known to have carried brought the load of even the most lightly equipped rifleman to seventy or more pounds. BAR-men and heavy weapons crewmen carried even greater burdens.3

Planners had taken early cognizance of the weight problem. In the critique of DUCK I, the director of umpires had recommended that the load of the infantrymen in the initial assault be kept under forty-four pounds. In subsequent exercises, however, these good intentions were gradually submerged as more and more “essential” items were added to the soldier’s pack, with the result that the load he carried in the OVERLORD assault eventually included several items not allowed for in recommendations of earlier conferences and critiques, such as grenades, TNT, a lifebelt, and a raincoat, which added about fifteen pounds to the load carried in the exercises.

Overloading had particularly serious consequences at OMAHA, where both surf and enemy opposition were greatest, and survivors of the landings there were virtually unanimous in their judgment that they had been overburdened with unessential impedimenta.4 Battle shock and fear in themselves are known to induce physical weakening, and every extra pound which the soldier carried only reduced his tactical capabilities still further and in many cases prevented men from ever reaching the beach.5

In the midst of mounting confusion and congestion came the first elements of the engineer special brigades, which were to organize the beaches for supply. First to land was a small reconnaissance party from the 37th Engineer Combat Battalion, which came ashore at exit E-3 within a half hour of the first assault wave. Within another thirty minutes eight other groups from the engineer brigades reached the beach, but it was immediately clear that their planned work was impossible. The tidal flat was becoming littered with dead and wounded, and the infantrymen who

had succeeded in reaching the sea wall or the shingle pile on the eastern end of the beach formed only a thin line of fire, which was inadequate to silence the enemy in his hill emplacements. Initially, therefore, engineers from the special brigades devoted themselves to aiding the wounded and building up the line of fire.

Landings continued in the second hour, but most of the men and vehicles were confined to the beach. A few small groups of infantrymen worked their way up the hills, but their penetrations were initially insufficient to reduce the enemy fire. The result was additional congestion and confusion. Engineer brigade troops landing in the second hour, mostly on the wrong beaches, joined the others in aiding the wounded and building up fire power. In a few cases they helped to blow gaps in the wire obstacles. Some units lost a large part of their equipment. Signal Corps troops, unable to use their transmitters, turned them over to the infantry who had lost their radios in the water.

Most of the landings in the first two hours were made near exits D-3 and E-1, in approximately the center of OMAHA Beach, creating increasing congestion and a profitable target for the enemy. The beach soon became littered with wrecked vehicles and landing craft, and to add to these difficulties the tide began to rise, forcing the gap assault teams to come ashore. This made the landing of all craft more and more hazardous and inspired the commander of one unit in the 6th Engineer Special Brigade to radio offshore command ships to stop sending in vehicles.

In the next two hours the number of landings was greatly reduced. The fire from the hills continued to be heavy, and many of the engineer troops continued to aid the infantry. One sergeant in the 37th Engineer Combat Battalion led a mine detector crew into an open field in the face of enemy fire and cleared a path up a defile between exits E-1 and E-3, opening the first personnel trail. Infantry units were then organized and urged to advance inland on this trail, and between 0830 and 1030 infantry parties managed to clear enough of the area around E-1 to enable elements of the 37th and 149th Engineer Combat Battalions to begin opening that exit. A company from the 37th cut one road from the tidal flat east of the exit, and another company from the 149th cleared a road to the west with dozers. Men from both battalions helped fill the antitank ditch blocking the exit and cleared mines from the road and a field to the west. Near D-3 elements of the 147th Engineer Combat Battalion cut through wire entanglements, blew gaps in the sea wall, and cleared the beach with dozers.

At 1030 the prospects for the beginning of orderly landings and the organization of the beaches still appeared very dim. The

tide reached its peak at that time, landings had almost come to a halt, and except at E-1 enemy fire appeared as heavy as in the beginning. Infantry troops, however, were beginning to filter over the hills to get at enemy positions to the rear of the beaches, and two fortuitous events helped change the future. Two landing craft (an LCT and an LCI(L)), unable to find a safe landing place, suddenly drove full speed through the obstacles in front of E-3, firing all their weapons at the enemy emplacements. Both craft beached and landed their men. One of them was damaged and could not withdraw, but several enemy positions had been silenced, and the beach obstacles were found to be less formidable than expected. Observing the success of this daring experiment, other craft began to follow suit.

The second event to give heart to the attackers occurred at about the same time. A destroyer neared shore, swung broadside, and, beginning at D-3, fired on the German emplacements at that exit and then continued down the beach hitting all defenses spotted. Lack of communications with the beach had prevented calling for naval fire, and naval officers until that time had refrained from firing on beach targets because of the vague situation on the beaches and the fear of hitting friendly troops.

These two events unquestionably influenced the more rapid progress which followed. Men readily moved forward under the destroyer’s support to take the high ground, and in the next two hours, from 1030 to 1230, more and more troops exploited the penetration inland, particularly on the eastern half of the beach. Additional combat units also landed to reinforce those already ashore, and some degree of order gradually emerged from the earlier chaos.

Elements of the engineer special brigades played a large role in resolving the confusion and congestion, although hardly according to plan. Beach clearance had been assigned first priority. But in some sectors such work was impossible and even pointless. First things came first. In some cases this meant clearing the ramps of LCTs so that undamaged vehicles could come ashore. In others it entailed removing damaged tanks and half-tracks which were clogging the beach exits. Shortly after noon all exit strongpoints were neutralized and a bulldozer began clearing the beach road. An attempt to cut a new road directly south from E-1 to the highway (Route B) proved premature, for Germans still held the ground north of the road. But vehicles began moving off the beach and over the hill, thus escaping the artillery fire that was falling on the beach, and at 1400 tanks began to use exit D-1. Exit F-1 had been cleared, but was of no use to vehicles because of the poor road. In the middle of the afternoon exit E-1 , at the center of OMAHA, was still the focal point of beach operations.

Late in the afternoon, as the tide dropped, the gap assault teams returned to the tidal flat to carry out the mission that they had found impossible at H Hour, With salvaged explosives and detonating equipment and dozers borrowed from other units they resumed the work of clearing the beach of obstacles and debris. The task proved difficult even at this time. Artillery fire still covered all exits and continued to fall on the beach, and the almost continuous arrival of new waves of infantrymen hampered the demolitions. By late afternoon, however, five large and six small gaps were cleared and marked.

In the meantime the situation in the center of the beach continued to improve. Fighting in the vicinity of St. Laurent-sur-Mer

delayed the opening of through traffic in that area, but late in the afternoon 1st Division engineers pushed a branch road through from E-1 to the highway so that vehicles could be driven up from the beach and shunted off into fields adjoining the highway. The exit road was thus cleared and some of the congestion on the beach was relieved. Meanwhile brigade engineers cleared minefields and opened up transit and bivouac areas where units could pause and reorganize. On the beach they continued to aid the wounded and clear wreckage. Enemy small arms fire gradually slackened and died out as the infantry and engineers mopped up more and more of the hill area.

Organization of the eastern end of the beach also got under way late in the afternoon. Advance units of the 5th Engineer Special Brigade landed between exits D-1 and D-3, 4,000 yards from their assigned beach, and made their way eastward. The first men from the 336th Engineer Combat Battalion arrived at Exit F-1 at 1700 and found that good progress had been made in the removal of obstacles. Because the condition of the exit road had been miscalculated some changes in plan were necessary, but demining teams and tractors immediately started work on another route and built a through road to the highway. Antitank ditches were filled, fields were cleared of mines, and a number of LCTs and other craft were ordered to land on the beach opposite F-1 in anticipation of the opening of the new exit. The exit was actually opened at 2000 hours when two tanks passed through, although succeeding tanks struck mines and were disabled. A path around the tanks was cleared, and by 2230 other tanks were passing through to aid in clearing the enemy from the Colleville area. Two small fields on the high ground were then demined and used as dump areas, the first deliveries being made in DUKWs preloaded with gas. Additional fields near the exit were cleared for use as bivouacs.

Toward evening the situation also improved at exit E-3. Enemy small arms fire was finally silenced about 1630. Men of the 348th Engineer Combat Battalion began sweeping the lateral beach road for mines, completing the task by 1700. For some time, continued artillery fire on the beach prevented work on the exit road, but by 2000 hours it slackened sufficiently to permit beach engineers to work on this road also. They made the most of the unusually late hours of daylight, but sniper fire stopped work after darkness fell. Tanks began using the exit shortly after 0100.

By the end of D Day, then, the prospects for systematic organization and operation of the beaches at OMAHA were much more encouraging. Brigade engineers had opened enough beach exit roads to accommodate all incoming vehicles and had made a good start on clearing obstacles from the tidal flat. Three exits—D-1, E-1, and F-1—were in operation, the first dumps were open, and units of the Provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group were ready to reorganize and begin their planned missions. Logistic operations on the first day had been limited chiefly to such tasks as removing obstructions and cutting trails to permit the movement of men, vehicles, and a few supplies away from the congested beaches. Tonnage targets had to be forgotten, and only a negligible quantity of stores could be landed and placed in the hastily improvised dumps. Personnel build-up, on the other hand, fared quite well in view of the heavy fighting on OMAHA Beach. Of the two loaded forces intended for OMAHA—Force O, with 29,714 men, and Force B, the follow-up force of 26,492

men, only part of which was expected to land on D Day—more than 34,000 are estimated to have crossed the beach on the first day.

All engineer special brigade operations on D Day were under the direction of the commanding officer of the 5th Brigade, Col. Doswell Gullatt. In midafternoon the command party of the Provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group arrived at Exit E-1 and set up its first headquarters in a beach pillbox. At midnight the commanding general of the group, Brig. Gen. William M. Hoge, took command of all units ashore. Those of the 6th Brigade, which had been under the control of the 5th, then reverted to their parent headquarters. The commander of the 6th Brigade, Col. Paul W. Thompson, became a casualty on D Day and was succeeded by Col. Timothy L. Mulligan.

UTAH Beach on D Day

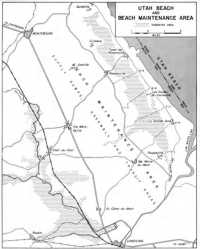

While operations at OMAHA were going badly, those at UTAH proceeded more nearly according to plan and provided one of the bright spots of the day. In many respects the physical characteristics of UTAH and OMAHA were similar, but in some ways they differed as sharply as did D-Day operations on the two beaches. UTAH Beach was a 9,000-yard stretch of flat sandy beach extending from the mouth of the Douve River north and northwest to Quinéville. (Map 13) The assembly, or transport, area for Force U was the same as for the OMAHA forces, ten to twelve miles offshore, and partially sheltered from westerly storms by the Cotentin peninsula. UTAH Beach itself, lying on the eastern shore of the peninsula, enjoyed even better protection than either OMAHA or the British beaches against storms from the northwest. Otherwise weather and tidal conditions were about the same. Deep anchorage for task force vessels was provided about two and a half miles offshore. UTAH, like OMAHA, had a wide tidal flat. In some places it was even wider than the one at OMAHA, and in the southern sector, near the mouth of the Douve, it was so wide and the gradient so slight that it was useless for landing craft.

The UTAH tidal flat had the usual type of beach obstacles, which were thicker toward the northern end of the beach. Beyond the high-water mark was a stretch of loose sand about twenty-five yards deep, backed by a concrete sea wall about five feet high which extended the entire length of the planned assault beaches. Gaps existed for exit roads at two places, but all other outlets were blocked off. Immediately to the rear of the wall were sand dunes, in some places barely extending above the wall, in others reaching a height of perhaps twenty-five feet. In this respect UTAH contrasted sharply with OMAHA, for there was no sudden rise immediately behind the beaches. Physically the dunes constituted no hazard to assaulting troops. But built into them were the enemy defenses—field fortifications consisting of fire and communications trenches, machine gun emplacements, and some field guns. Concrete pillboxes were built into the sea wall itself and thus were tied in with the other fortifications. The strongest of these were on the northern half of the beach, at Les Dunes de Varreville and beyond.

The grassy sand dunes extended inland from 200 to 600 yards, sloping downward and becoming flat pasture land and cultivated fields. The fields were small in size and distinctly outlined by their tall border hedges, drainage ditches, and tree lines. Behind the actual assault beaches, in the

Map 13: UTAH beach and beach maintenance area

southern sector of UTAH, the flat pasture land extended inland about 1,000 yards. Farther north it gradually decreased in width and almost disappeared, becoming only a narrow spit of solid ground between Ravenoville and Quinéville. Beyond this solid ground lay an inundated area. This feature of UTAH Beach, plus the absence of hills behind the beaches, formed the most striking contrast with OMAHA, and created an entirely different problem.

The flooded area extended from Quinéville south to the Douve River and averaged 1,500 to 2,000 yards in width. In the area of the assault opposite La Grande Dune the water started 1,000 yards behind the beach and extended 1,800 yards inland, its depth varying from two to four feet. This water barrier was an artificial one, created intentionally by the enemy to prevent, or at least hinder, an advance inland. The flooding was controlled by obstruction across several small streams south of Quinéville, and in the southern sector additional inundations could be created by the control of certain locks, for the land was slightly below sea level at high tide. Beyond these inundations the terrain was similar to that behind OMAHA Beach. It consisted of gently rolling country and offered no unusual difficulties to the attackers except for the hedgerows that sharply limited observation. The enemy built heavily fortified casemated batteries on the headlands overlooking the inundated area.

The flooded area posed a special problem in the UTAH area. Even if the assaulting troops overcame opposition on the beaches they would still have to cross the flooded area. There were only a few roads or causeways across these inundations, down which the attacking forces would be channeled, and it was likely that the western shore of this area, and particularly the road exits, would be defended. The anticipation of difficulties in crossing this barrier was one of the chief reasons for the decision to use airborne troops. These troops were to drop behind the inundations, disrupt communications, capture strategically important objectives, and secure the western exits to facilitate the crossings of the seaborne forces. The roads and causeways that led from the beach inland and across the inundations were therefore an important feature of the area. Infantry troops might with difficulty be able to wade through the shallower parts of the inundations; but the area was honeycombed with deep drainage canals and tributary ditches, which presented a hazard to any movement inland, and the causeways were vitally necessary to the movement of vehicles and artillery.

The roads leading across this artificial lake in the area of the assault varied as to type and state of repair. The following ones were the more important, from north to south: S-9, which was flooded along its entire length; T-7, which was also flooded for most of its length, but hard surfaced and usable even though under water; U-5, leading directly inland from the center of the assault area, narrow but hard surfaced and in good condition, and the first to be used by troops on D Day; and V-1, at the southern extremity, which was almost completely dry, but in poor condition and without a beach exit. All of the causeways were narrow, and their shoulders had been softened by the water. The importance of gaining immediate control of them was obvious.

Plans for the landings at UTAH Beach were very similar to those for the landings at OMAHA. Infantry assault teams were to constitute the first wave, followed closely

by the gap assault teams which were to clear avenues through the obstacles on the tidal flat. The initial landings by two battalions of the 8th Infantry (4th Division) took place approximately on time, but about 2,000 yards to the left (south) of the planned beaches. The error actually proved fortunate. Beach fortifications at the planned landing spots were stronger, and the tidal flat was mined and had many more obstacles than farther south. The actual assault beach had only one less favorable feature. The distance between the low- and high-water marks was greater, creating a wider tidal flat, forcing craft to remain farther offshore, thus causing some beaching difficulties.

The first landings were made astride route U-5, rather than T-7 as planned. Some of the amphibian tanks were late in arriving, but almost all of them landed and aided in reducing the opposition along the beach. The gap assault teams which had been scheduled to land in separate waves—the Army-Navy teams to clear the underwater obstacles, and the Army teams to clear those above water—actually landed almost at the same time. This departure from plan also proved fortunate, for all obstacles were found to be dry, and the demolition teams therefore found it possible to clear complete lanes by placing their charges on all bands and blowing them simultaneously. And since the obstacles were not as thick as had been expected, they cleared the entire assault beach on the first tide instead of blowing only fifty-yard gaps as originally planned. A wide avenue of approach was therefore open at an early hour, allowing uninterrupted landings on a relatively broad front. Other engineers meanwhile proceeded to blow gaps in the sea wall and to destroy barbed wire obstacles in front of the wall and on the dunes. Four gaps were soon blown in the wall to provide exits for vehicles, and two Belgian gates were blown from the exit at the terminus of route U-5.

Elements of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade, including its commander, Brig. Gen. James E. Wharton, began to cross the beach at about H plus 60 minutes. Initially the brigade was to organize two beaches, known as Uncle Red and Tare Green, each with a width of 1,000 yards. To the north of Tare Green a third beach, Sugar Red, was to be opened on the second tide. When the assault forces landed too far south these beach designations were simply shifted to correspond to the actual landings. Uncle Red and Tare Green therefore lay approximately south and north respectively of the U-5 exit.

The first elements of the brigade to land came from the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment and the 286th Joint Assault Signal Company. When they landed (H plus 60 minutes) there was no longer any small arms fire on the beach except from a few snipers, although there was intermittent shelling from inland batteries. There was none of the congestion that prevailed at OMAHA. Units arriving in the succeeding waves had no difficulty getting off the beach, and there was very little wreckage. The initial tasks of the engineers included the building of exit roads through the sea wall and dunes, and the clearing of mines from roads, dump sites, and transit areas. Few areas in the immediate vicinity of the assault beaches were actually mined, but the enemy had marked many fields as mined and they had to be combed thoroughly. While the fields were being checked, brigade engineers widened the gap at U-5 and blew additional gaps in the sea wall. They improved the existing

beach road with wood and wire matting known as chespaling. U-5 was found to be usable, and troops and tanks began crossing the flooded area via the causeway. Meanwhile General Wharton redesignated the beaches, and markers were prepared to aid incoming craft in locating the beaches, exits, and various installations as they were completed. Officers also reconnoitered the area north of Tare Green, and the beach was partially cleared in preparation for its operation (as Sugar Red) by the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment. The 1st Brigade command post was established about 700 yards behind the dune at the small hamlet of La Grande Dune. With the arrival of other brigade units, such as elements of the 1106th Engineer Combat Group, work also began on the causeway roads across the flooded area, and on the sluice gates which controlled the water in the inundations. The most important of the locks were the northern gates near Quinéville, the central gates north of Sugar Red beach, and the locks southeast of Pouppeville. Neither the northern nor central locks could be reached on D Day, but elements of the 1106th worked their way down the beach to the Pouppeville area, removed booby traps, and demined and opened the locks there to begin draining the southernmost area.

The organization and operation of UTAH Beach proceeded, but not without difficulties. Enemy shelling continued with varying intensity and hampered beach work to some extent. Perhaps more important were the navigational difficulties, changes in naval landing orders, and beaching troubles, which contributed to a general slowing down of the landings. The planned phasing of troops fell behind schedule quite early, vehicles arrived late throughout the day, and the sequence of landings was not strictly followed. The remoteness of the transport area and defects in ship-to-shore communications and coordination contributed to these difficulties. One of the chief tasks of beach engineers was to rescue drowned vehicles. Because of the shallow gradient, landing craft tended to discharge their loads in deep water, and many vehicles stalled as they left the ramps.

Nevertheless the build-up continued steadily and in a much more orderly manner than at OMAHA. Causeway U-5 had been placed in service during the morning after some difficulty with an enemy antitank gun on the west bank of the inundated area, and engineers had quickly installed a treadway bridge to replace a culvert which had been blown. U-5 was the best of the causeways and soon bore the main burden of vehicle traffic inland. By noon it was clogged with vehicles, and two-way traffic became almost impossible because of the trucks and guns which had slipped halfway off the soft shoulders and mired in the mud and water that came within a foot of the road’s surface.

Development of the beaches themselves continued as additional elements of the 1st Brigade landed. Work on the third beach, Sugar Red, was stepped up with the arrival of the 3rd Battalion of the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment, although the job was hindered somewhat by the continuing shellfire and by the late arrival of road construction equipment. As the tide again ebbed later in the day gap assault teams returned to the tidal flat they had cleared on the first low tide. They resumed the demolition and removal of obstacles on the flanks and thus cleared a still greater expanse of beach. Eight major gaps were blown in the sea wall, and Sommerfeld

track6 was laid to the existing lateral roads. About nightfall route T-7 was opened, although the road was still under water.

Unloading operations also proceeded more satisfactorily than on OMAHA, although hardly according to plan. Because every craft scheduled to land and discharge on D Day was combat loaded, all unloading was confined to the offloading of trucks and the unloading of engineer road-building equipment from preloaded LCTs. Only six of the twelve LCTs came in on D Day, and one of the six was lost after it beached when it received a direct hit from an enemy shell. Two others were hit but managed to transfer their loads to other craft. The remaining six beached and unloaded on D plus 1. Dumb barges7 were also beached on D Day, but were kept in reserve and not unloaded. Only limited use was made of DUKWs on the first day. Four of the amphibians came ashore with their cargoes at 1330 and during the rest of the day were used to evacuate casualties. Since the DUKWs were not yet greatly needed, most of them were held offshore until D plus 1 to prevent losses.

The establishment of dumps and transit areas also began on the first day, but could not proceed as planned because some of the chosen areas remained in enemy possession. Beach dumps were established on Tare Green for ammunition and medical supplies, and brigade officers reconnoitered inland dump sites. Class I, III, and engineer Class IV sites were in the hands of the 4th Division, but still under the fire of enemy snipers. None of the other planned locations had been captured. The same situation prevailed for the transit areas. One was overrun but was under enemy fire; another remained in enemy hands throughout the day. Incoming units therefore reorganized and bivouacked in an initial assembly area immediately behind the dunes, thus causing some congestion and hindrance to engineer operations toward the end of the day. Military police units began to land within the second hour of the landings, their principal task being to keep traffic moving inland so that troops and vehicles would be dispersed and other units could cross the beaches.

As at OMAHA, brigade units worked late on D Day (until 2300). Enemy planes raided the beach after darkness, but they inflicted no damage, and the end of D Day saw a fairly high degree of organization and security despite landing difficulties and enemy fire. The tidal flat was clear of obstacles, exit roads had been established, the beach area had been demined, two causeway roads were in use, and a few dumps were established and in operation. There are no estimates as to tonnages of supplies landed, but approximately 23,000 of the 32,000 men in Force U crossed the beach on D Day.

Development of the OMAHA Area

At both OMAHA and UTAH various difficulties hampered beach development, and discharge performance was erratic for some time. UTAH was subject to enemy artillery fire for a full week. The Germans shelled OMAHA only until about noon of D plus 1, but sniping from scattered enemy troops plagued the beach maintenance area for several days. The engineers were under the initial disadvantage of having to clear a great amount of wreckage. Ship-to-shore

operations did not go smoothly at either beach at first.

These troubles were gradually overcome, and tonnage discharge improved steadily. Beginning with an estimated capacity of 2,400 tons on D Day, the daily discharge rate at OMAHA Beach was scheduled to reach 10,000 tons by D plus 12 rising to 15,000 tons in about two months. UTAH was estimated to have a starting capacity of 2,250 tons, leveling off at 5,700 tons by the end of the first week and ultimately attaining a maximum of 10,000 by the end of the second month. There are no records of actual unloadings on D Day and D plus 1. Available figures indicate that UTAH exceeded its planned intake of 3,300 tons on D plus 2. But the chaotic situation at OMAHA in the first day or two and the shipping and unloading difficulties at both beaches permitted a total discharge of only 26.6 percent, or 6,614, of the planned cumulative 24,850 tons at the two beaches in the first three days.8

Marked improvement was made in the next few days at OMAHA, where the target of 7,000 tons was actually exceeded on D plus 5. At that time 28,100 tons or 46.6 percent of the planned cumulative 60,250 tons had been discharged on the two beaches. Vehicle build-up continued to lag at both beaches, with only 20,655 or 65.7 percent of the planned total of 31,424 tons unloaded at this date. Personnel build-up fared considerably better. By D plus 5, 88 percent, or 184,119, of the planned cumulative build-up of 207,771 had been achieved, with eight and a half of the planned nine divisions ashore.

The progress of the OMAHA area was made possible partly by the rapidly moving tactical situation. On the morning of D plus 1 enemy troops were still fighting on the edge of Vierville and St. Laurent. But the advance south of Colleville was more rapid. On D plus 2 the Americans entered both Formigny and Mosles and made a rapid advance westward almost to Grandcamp. On D plus 3 they entered Isigny, and with the taking of Trévières on D plus 4 all of the area north of the Aure River, the proposed beach maintenance area, came under V Corps control.

One of the chief concerns of the beach brigades was the protection of the beach area against enemy activity. Elaborate precautions were taken, particularly against air attacks. In addition to taking normal measures, such as providing antiaircraft artillery and camouflaging installations, the Americans made plans for the use of deceptive lighting to represent such things as convoys and beach exit roads, and also for the use of smoke. But the deception plan was abandoned as unfeasible, first, because capture of the area in which it was to be used was delayed and, second, because the bright moonlit nights made its success doubtful. Nor were smoke generators used, inasmuch as air attacks never became serious. The few enemy planes that appeared over the beach every night inflicted only slight damage on installations and troops. Enemy activity was directed mainly against ships anchored offshore and consisted primarily of dropping mines, which caused some sinkings. The most serious damage in the beach maintenance area occurred on the night of 13–14

June, when fifteen tons of ammunition were destroyed in a dump near Formigny. Beyond this sporadic and relatively ineffectual air activity the enemy did little to disrupt the organization of the beach. The development of the beach maintenance area and port area therefore proceeded relatively free of interruption.

Plans had outlined three phases in the development of the beach areas after the assault. In the first phase, known as the initial dump phase, the beaches were to be marked and cleared of wreckage, and temporary supply dumps were to be established on the beach itself. The second phase, called the beach maintenance area dump phase, was to begin when the dumps were moved farther inland. The third, or port phase, would begin with the opening of the MULBERRY. These designations were established simply for convenience in planning, and no schedule was written for the beginning and ending of the phases. The transition from one to another was expected to be gradual, with certain installations closing as new ones were opened.

The initial dump phase may be said to have begun on the morning of D plus 1, the first beach dumps having been opened late the first night. One of the first tasks on D plus 1 was marking the beaches so that incoming craft could locate the proper unloading points. The few markers that had been erected on D Day were shot down by enemy artillery. Beaches were designated in accordance with the British “World Wide System” of marking. Under this system the entire 7,900-yard stretch of beach was divided into sectors, named after the phonetic alphabet, beginning with Able at the western extremity. What is usually referred to as OMAHA Beach consisted of beaches Dog, Easy and Fox. Each of these was further subdivided into three sub-beaches known as Green, White and Red. The beaches were marked with large panels, and with colored lights at night.

Another task which had high priority was beach clearance. On the morning of D plus 1 the tidal flat was still littered with wrecked ships, drowned vehicles, obstacles, and equipment. Scores of craft lay beached at the high-water mark, some undamaged, but many torn by shellfire. The clearance of the flat was obviously necessary to allow the beaching of additional craft and the movement of men and supplies. Special brigade units applied themselves to this task at first light at D plus 1. In addition, survivors of the demolition teams returned to remove the remaining obstacles, and dozers towed away swamped vehicles. Some craft were patched up enough to be floated again. Several days were required to complete this cleaning up. In the meantime work also proceeded inshore of the high-water mark. Gaps through the shingle pile and sea wall were widened, chespaling was laid on the soft sand to provide a firmer footing for vehicles, beach exit roads were improved, and mines were swept from fields needed as bivouac areas or parking and dump sites.

Preoccupation with preliminary work such as clearance delayed the planned development of the beaches. One result was that LCTs and preloaded barges intended as an insurance against bad weather were the only means of supply on both beaches in the first days, and larger vessels could not be berthed inshore until late on D plus 1. By D plus 2 an enormous pool of unloaded ships lay offshore, and the debarkation of personnel and unloading of supplies consequently fell far behind schedule.

Other conditions contributed to this lag. Certain methods of discharge of the various types of ships and craft had been specified and a system of calling in and berthing of craft had been worked out. Both plans had to be radically altered before unloading met requirements. Troops and vehicles continued to go ashore on D plus 1 via two methods. Under the first, landing craft, except LSTs, beached and when necessary “dried out.” The craft would beach on a falling tide, discharge after the water had receded, and then wait to be refloated on the next tide. Vehicles and men could thus go off the ramps onto a dry beach instead of wading through several feet of water. Only the smaller craft used this procedure. MT coasters, MT ships, APA transports, and LSTs were unloaded onto ferry craft and DUKWs. But it became evident on D plus 1, when unloadings fell behind, that the process had to be speeded up. One solution was to beach LSTs and dry them out, as was being done with smaller craft. This method was urged by ground force commanders in both the V and VII Corps, for there was growing concern over the lag in the build-up. Naval authorities had not favored this procedure for LSTs because ground inequalities on the beaches might cause hogging damage. Larger craft had been successfully beached in the Mediterranean, where tides were small, but it was feared that they might break their backs if dried out on the Normandy beaches. When landings fell behind schedule, however, and when the Americans realized that scores of smaller craft had been lost in the assault, they decided to take the risk. Experimentation with several vessels revealed no damage to the ships,9 and, beginning on D plus 2, LSTs were dried out regularly. More than 200 were unloaded in this manner at OMAHA in the first two weeks, all without damage. The discovery that the beaching and drying out technique could be applied to LSTs was an important factor in the accelerated build-up of troops and vehicles.

A second important modification was necessitated by the partial failure of the plan for calling in and berthing ships and craft. Supply plans for OVERLORD had laid down a procedure by which stowage and sailing information could be transmitted to the First Army, enabling the latter to establish unloading priorities in accordance with immediate and foreseeable needs. Times of departure, identities of ships, and manifests showing their content and stowage plans all were supposed to be communicated to the First Army in advance by a combination of radio and airplane or fast surface craft. First Army was to consolidate this information and send it to the beach brigades, assigning priorities for unloading. Upon the actual arrival of ships at the far shore, the Naval Officer in Command (NOIC) at the beach was to inform the brigades, which would indicate the time and place of berthing according to priorities established by the army.

This plan broke down in actual operations, mainly as the result of poor communications. The inability of planes to get through, and the tardy arrival of courier launches, plus other failures in communications, meant that ships would arrive and no agency ashore or afloat would know their identity or their contents. Stowage plans were not received, and ships arrived without being seen by the NOIC. In addition,

there was a shortage of ferry craft to transfer cargo from ship to shore. The lack of orderly control of allocation and berthing of ships resulted in considerable confusion afloat and ashore. Lacking instructions, ships’ masters frequently made their own decisions on where to anchor their ships, some going to the wrong beaches, many of them anchoring too far offshore, thus necessitating long round trips for ferry craft and DUKWs.

First Army initially insisted on adhering to the system of selective unloading and unloading on a priority basis, even though manifests were unavailable and the names of the ships offshore were unknown. For a time Navy and Transportation Corps officers had the impossible task of going about in small boats to determine what ships were present and what cargo they carried. Armed with this information First Army would then indicate the vessels it wanted unloaded. Since unloading priorities and allocations were often made late or not at all, the brigades likewise resorted to expedients and adopted the practice of scouting for ships awaiting discharge, and then working whatever vessels were ready and eager to unload.

The subsequent provision of radio communication between the offshore naval control craft and beach headquarters made it possible to identify craft on arrival at the control point and to make arrangements with the beach brigades for berthing. But these improvements in communications were not made in time to prevent the formation of a large backlog of loaded ships and craft. A more immediate although temporary remedy was found in abandoning the priority system. After repeated requests by naval authorities, First Army finally agreed on D plus 4 (10 June) to order LSTs and LCTs unloaded in the order of their arrival, and on the following day it ordered all ships and craft unloaded without delay and without regard to priorities. Another expedient which aided in speeding up unloading operations was the relaxation of blackout restrictions. Because opposition was slight, vessels were authorized on 12 June to use hooded lights to permit unloading to proceed at full capacity throughout the night. By that date a shortage in some types of ammunition had developed, particularly in 155-mm shells, and ammunition was therefore given unloading priority for a time. The new plan quickly solved the problem, and the backlog of ships was cleared by D plus 9 (15 June).10

In ship-to-shore operations, cargo was moved by a variety of ferry craft, including lighters, barges, DUKWs, and landing craft of the smaller types, principally the LCT, which was considered one of the most useful of the naval craft. By plan, the deputy assault group commanders were to direct the use of ferry craft until the NOIC was ready to take control. After the assault, however, the landing craft were scattered, it was difficult to concentrate them at the designated rendezvous points, and the deputy assault group commanders were not equipped to operate the large numbers of craft. Consequently the transition of control to the NOIC was “not notable for its orderliness,” and the employment of ferry craft was not efficient in the early stages. In many instances craft were unavailable when needed, and sometimes they were as much as forty-eight hours late in responding to requests. While

their first-priority mission was to unload vessels carrying vehicles, in which a backlog developed, it became necessary to shift the ferry craft to certain coasters loaded with critical supplies.

One of the most useful of the various types of craft was the Rhino ferry, a barge made up of ponton units and propelled by outboard motors. Rhino ferries were towed across the Channel, their crews riding on the open and unprotected decks, and then used to unload LSTs and MT ships. They enjoyed several advantages over other craft, for they had a large load capacity (two could normally empty an LST), their cellular construction made them almost unsinkable, and they could discharge vehicles on beaches of almost any gradient. Even when they were poorly beached and broke their backs the undamaged sections could readily be joined with others to build a new ferry. In the early stages, before LSTs were beached, these craft brought in a large percentage of the vehicles, and their crews displayed a high quality of seamanship in handling the unwieldy craft.11

Much of the initial cargo unloading was accomplished by DUKWs. These 2½-ton amphibians were called on to bear a heavy burden in the early ship-to-shore operations and, as in the earlier Mediterranean operations, proved their versatility and endurance. The first DUKWs were scheduled to land within the first hour on D Day. One unit attempted to land at that time, but its officer was killed and none of the amphibians reached the beach. Others went ashore early in the afternoon, but most of the DUKWs scheduled to land on D Day were held offshore until D plus 1. Once they were available great demands were placed on them because of the shortage of both ferry craft and trucks. The lack of trucks forced the DUKWs to carry a major portion of the supplies the entire distance from the ships to the initial dumps. They had originally been intended to carry their cargo only to beach transfer points, where it was to be lifted onto trucks and transported to dumps. The practice of having DUKWs carry their cargo beyond the beaches was uneconomical, for their ship-to-shore function was a highly specialized one. They had a relatively slow speed in the water, and the added mileage only increased their turnaround time and thus reduced their overall capacity. Nevertheless they continued to make the complete round trips to the dumps until enough trucks became available and transfer points were established.

To make matters worse, many of the DUKWs were discharged as far as twelve and fifteen miles from shore in the first two days. Many exhausted their fuel in the long run, in maneuvering, in searching for the proper beach, or in awaiting an opportunity to land. When they ran out of fuel they sometimes sank, for the bilge pumps stopped when the motor went dead. In addition, most of the amphibians preloaded for the assault were overloaded. Their normal load was three tons, but most of them carried at least five tons, and some as many as six and seven, a burden that caused many to swamp. While maintenance of the DUKWs was generally good, there was a serious lack of spare parts, which had to be salvaged from sunken vehicles and from 2½-ton cargo trucks, many of the parts being interchangeable. Despite excessive periods of operation and special maintenance problems the DUKW again demonstrated its usefulness and dependability. Its unique ability to transport

Discharging at the beaches. Landing craft

Discharging at the beaches. Rhino ferry

cargo both from ship to shore and overland to dump contributed immeasurably in meeting the problem posed by the shortage of trucks, cranes, and transfer rigs during the first days, In the words of one observer, “It converted this beach operation from what might have been a random piling of supplies on the beach to an orderly movement from ship to dump.”12

Landing hazards had reduced the number of trucks available, and many were either lost or held offshore longer than planned. The losses resulted more from drowning than enemy fire. Landing craft often beached in front of deep runnels and sometimes lowered their ramps in four to six feet of water. Waterproofing failed to protect vehicles in such depths, and many were either swamped or mired in sand after leaving the craft. The 5th Brigade alone lost forty-four trucks in the first two days, mainly in this way. At no time were there enough vehicles to meet the great demand for them on the beach. The critical period in operations came at low tide when trucks were needed for hauling the cargo brought ashore by ferry craft as well as the cargo brought to transfer points by DUKWs. Maintenance work on trucks was therefore restricted to high-tide periods, and available vehicles were pooled under brigade direction and allotted to the engineer battalions in accordance with needs.

Quartermaster and Ordnance units, attached to the brigades to set up the first dumps, began landing at D plus 90 minutes, but they found it impossible to carry out their assigned tasks because of enemy fire. Elements of the 95th Quartermaster Battalion, for example, suffered sixteen casualties coming ashore, others were forced to dig in on the beach, and still others were held offshore. Despite the situation on the beach some supplies were brought ashore and piled on the beach, and the 37th Engineer Combat Battalion cleared a few small fields for emergency dump and transit areas, at which preloaded DUKWs discharged the first ammunition. These emergency dumps in the 5th Brigade area operated through D plus 2, and then were consolidated with larger dumps. In the 6th Brigade area on the western half of OMAHA Beach emergency Class V dumps were established as late as D plus 1 and 2, and one continued to issue ammunition till D plus 5. Meanwhile the first planned dumps were opened in the 5th Brigade area on D plus 1 and in the 6th Brigade area on D plus 4. They were located behind the cliffs, inland from the beach. Sniper fire hampered operation of the 5th Brigade’s initial dumps until D plus 3, and in the western sector the dumps were still so near the front lines when they opened on D plus 4 that shells were taken from their boxes at the dump and carried by hand to the artillery batteries. Very little segregation of supplies was possible, and it was difficult to locate required items. In these first days priority of cargo unloading was generally given to ammunition, and on D plus 4 a special air shipment of 200,000 rounds of small arms ammunition was made to overcome a developing shortage in this category. The reserves of Class I and III (rations and gas) carried by the units in the assault tided them over the critical first stages when supply was difficult.13

On D plus 6 (12 June) the initial beach dump phase ended and the beach maintenance area dump phase began. On that

day the inland dumps began to function, although a few had actually begun to issue supplies the day before. The dumps were located very much as originally planned, except those for Class V (ammunition), which were consolidated near Formigny. It became evident early in the operation that ammunition would offer the biggest supply problem, since stocks were not built up as rapidly as had been hoped. The Americans decided to open only one Class V dump, the one near Formigny, and First Army almost immediately took charge of it. On D plus 7 First Army decided to take control of all inland dumps from the beach brigades in order to tighten control over the issue of critical items. The responsibility of the special brigades was thereby limited to unloading supplies from ships and craft and passing them across the beach to the army supply points. In the next few days engineer, signal, and medical dumps were opened, and existing installations were expanded. Most of the dumps were located in the small Normandy fields, with supplies usually stacked along the hedgerows which provided partial concealment. In many cases it was necessary to fill ditches and punch gaps in the hedgerows to permit truck movements. The fields were well turfed and provided a firm footing for storage, but there was considerable trouble with mud during rainy spells.

While the beach maintenance area dumps were being established, the first transfer points were opened on the beach in order to speed deliveries to the dumps and to save DUKWs the long trip inland. The transfer points were simple, consisting mainly of crane facilities to swing nets of cargo from DUKWs to trucks. They were set up so that DUKWs and trucks approached the cranes in parallel lanes on either side, with the cargo being transferred either directly or to a platform where it could be sorted and reloaded. Later, when more trucks were available, a highly organized transfer system was worked out with carefully coordinated control, closely regulated traffic, and an efficient communications system connecting traffic control towers, truck pools, and transfer points, to facilitate the most economical use of all vehicles.

In contrast to the confusion and chaos of D Day, activities at OMAHA Beach by the end of the second week resembled the operations of a major port. Except for three or four wrecked craft, beaches were clear, and minefields behind the sea wall were slowly being cleared. Additional roads were pushed through the shingle pile, and exits were blasted through the sea wall. The discharge and inland movement of cargo and the evacuation of casualties and prisoners of war were highly organized. One of the most encouraging developments for the engineer special brigades was the build-up of trucks, for every additional truck increased the amount of cargo which could be unloaded and moved forward. By the end of the second week the limiting factor in supply build-up was no longer the number of trucks, DUKWs, and ferry craft, but the arrival of ships. At that time the daily tonnage discharge at OMAHA averaged nearly 9,000 tons, about 95 percent of its target, and approximately 11,000 men and 2,000 vehicles were crossing the beach every day and moving forward to add their weight to the offensive.

Development of the UTAH Area

UTAH Beach likewise developed into an important logistic base within the first two weeks, although on a smaller scale than OMAHA. In the first few days UTAH was actually able to receive greater tonnages

than its neighbor (a total of 7,541 tons in the first four days as against OMAHA’S 3,971) and in the second week of operations it began to achieve a daily discharge of between 5,000 and 5,500 tons, which roughly approximated the planning figures.

In developing that rate UTAH experienced difficulties not unlike those encountered at OMAHA, despite the initial advantages enjoyed as the result of the more orderly landings. Although the beachhead at UTAH was relatively deep, its flanks were not immediately extended sufficiently to secure beach operations from enemy artillery fire. Expansion of the lodgment was slow in the first week, and in the north the limited progress had special importance because of the strongly fortified headland batteries in that sector. Observed artillery fire fell on the beach until D plus 5, and sporadic unobserved fire continued until 12 June and had a noticeable effect on unloading operations. On that day the 4th Division finally overran the last enemy battery able to fire on the beach.

The UTAH installations were also subjected to enemy air attacks, but, as at OMAHA, the Germans made their raids entirely at night and concentrated on shipping and on mining the harbor. Several casualties resulted, but no damage was done to beach installations. Activity was hampered more by the slow progress in broadening and deepening the beachhead. The 1st Engineer Special Brigade’s units were confined to a much smaller area than planned. During the first week five battalions of engineers were restricted to an area which was scheduled to have been operated by two.

The UTAH beaches were to have been marked like the OMAHA beaches, but differences in the physical features of the two areas made this impossible. At OMAHA the signs were placed well up on the hills and were clearly visible to incoming craft. Since there was no high ground at UTAH, markers were initially erected along the sea wall where they could not be seen from very far offshore. The addition of barrage balloons as markers remedied the situation on D plus 1. The balloons, appropriately colored and numbered, were flown at the beach boundaries, and on the cables holding the balloons naval signal flags were flown to guide incoming craft. The system proved very successful, although there was suspicion in some minds that the balloons provided a convenient target marker for enemy artillery in the first week.

While the removal of debris and obstacles from the beach of necessity held first priority at OMAHA, supply clearance was the main problem at UTAH because of the inundations. The 1st Engineer Special Brigade had to give immediate attention to drainage of the flooded area and improvement or construction of exit roads. The engineers began drainage at once and at the southern end of the beach did the job rapidly. The central gates north of Sugar Red were opened on D plus 2, but they required constant maintenance and had to be closed during periods of high tide. The northern gates could not be opened until after D plus 8 because the enemy occupied the Quinéville ridge. Even in the southern area, where drainage was effected, the fields remained saturated and could not be used as transit areas or dumps. The chief effect of the drainage on military operations was to make some of the previously flooded roads usable. Route T-7, although completely under water, was used beginning the night of D Day, but the heavy traffic quickly made it impassable. On D plus 3 it was closed, and troops of the 531st

Engineer Shore Regiment worked continuously for thirty-six hours to improve it. By that time the water was drained off and the road was graveled, and it proved one of the most useful of all routes leading from the beach.

To relieve pressure on the lateral road which paralleled the beach about 700 yards inland, and also to speed traffic along the beach itself, engineers quickly laid Sommerfeld matting along the base of the dunes and parallel to the sea wall about 125 feet inland. They blew additional gaps in the wall, improved the exits by dozing and grading, and laid matting in these exits and also along stretches of the beach itself. At the southern extremity of the beach, route V-1 was improved and carried some traffic beginning the night of D Day. To provide access to it the engineers extended a lateral beach road southward from U-5. By D plus 1 UTAH Beach had several exits through the sea wall, two lateral beach roads, and three outlets across the flooded area.

Throughout the first weeks the three beaches opened on D Day—Uncle Red, Tare Green, and Sugar Red—continued to serve as the principal landing points. Initially the most important was the southernmost of these beaches—Uncle Red. It was free from shellfire and had the best exit and road, U-5. One battalion of the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment was originally supposed to move north on D plus 1 and open a fourth beach south of Quinéville. Since the area was not cleared for several days, such a move was impossible.

Instead, plans were made to open an additional beach north of Sugar Red, known as Roger White. That beach was reconnoitered on D plus 2, while still under enemy artillery fire, and on D plus 4 elements of the 38th Engineer General Service Regiment landed and began developing the area. The principal route (S-3) serving Roger White had been flooded, like S-9 to the south, but the opening of the gates drained it sufficiently to make it usable. The engineers meanwhile proceeded with their usual tasks of preparing the beach for unloading operations. Beach obstacles, which included tetrahedra and mined stakes in this area, they either blew or pulled off the tidal flat, and they blasted gaps in the sea wall. By 12 June the beach was announced ready for operation. No DUKWs were on hand at that time, however, and no coasters were ready for unloading. Furthermore; the beach was still subject to enemy fire. Its opening was postponed, therefore, and it was not put into operation till later.

While unloading operations got off to a better start at UTAH than at OMAHA, build-up targets were not met in the VII Corps sector for several days. The unloading of the first tide convoy was not completed until D plus I. Of the twelve preloaded LCTs scheduled to land on D Day, six came in on the second tide, and the remainder did not beach until the morning of D plus 1. Some of the LBV’s landed at OMAHA by mistake. By D plus 2 all sixteen supply coasters were located and were unloading, but discharge proceeded slowly because the DUKWs had to make such long trips from the transport area to the dumps. The initial refusal to beach LSTs compelled all unloading to be accomplished by DUKWs, by ferry craft such as LCTs and LBV’s, and by the dumb barges intended as a bad weather reserve. Unloading soon fell behind schedule, and the lag created apprehension on the part of the ground commanders. In this respect UTAH’S experience was similar to OMAHA’S. A backlog

of shipping developed and was not relieved until the decision was made to beach LSTs. Once this decision was made, as many as fifteen LSTs were brought ashore at a time.

Other factors contributed to the slow start. Neither trucks nor DUKWs were plentiful. Three DUKW companies came ashore on D plus 1, and an additional four companies came in within the next five days.14 But the shortage of trucks made it necessary for DUKWs to carry cargo the entire distance to the inland dumps. Some vessels carrying hatch crews from the United Kingdom failed to arrive on schedule. And before the first week had passed, a partial breakdown of the loading arrangements at Southampton set back the movement of troops and supplies still further.15

Additional difficulties arose from the initially imperfect functioning of the brigades and the temporary disorganization of ship-to-shore operations. While some units of the special brigades had trained together, the beach organizations were really put together for the first time on the beaches and did not immediately achieve their highest efficiency. A loose control of certain units of the brigades, such as the DUKW companies, at first resulted in wasted effort and inefficient ship-to-shore operations. Furthermore, the early lag in unloading created a natural anxiety in the minds of the corps commanders, who intervened in the beach organization in an effort to hasten the discharge of supplies.16

Part of the trouble lay in poor coordination between the Army and Navy at the beaches. Control of shipping at both OMAHA and UTAH left much to be desired, and close cooperation with the Navy was delayed by the late arrival of the Naval Officer in Command, who was responsible for the control of ferry craft and for the location and berthing of all vessels. At UTAH the NOIC was finally ordered ashore at the request of the VII Corps commander.17 A further stumbling block to the smooth functioning of the beach port was the disagreement between the Navy and the brigade over the former’s policy of holding ships offshore to prevent damage from shelling. Once these various difficulties were ironed out and lines of control were clearly established, discharge at UTAH proceeded more smoothly. On the whole, cooperation between the 1st Engineer Special Brigade and the Navy was close, since the 2nd Naval Beach Battalion had operated with 1st Brigade in the Mediterranean. Brigade headquarters eventually established a close control over all units involved in cargo unloading; it notified the NOIC of its requirements, and the NOIC allocated ferry craft through the Navy’s Ferry Craft Control.