Chapter 11: The Logistic Outlook in June and July

Tactical Developments, 1–24 July

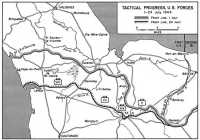

After the capture of Cherbourg on 27 June the First Army reoriented its resources for a general drive southward. At the end of June the lodgment in the OMAHA sector reached a depth of about seventeen miles, extending south to Caumont and almost to St. Lô. From there the American lines arched sharply northward and westward, and in the vicinity of Carentan, vital communications link between the U.S. forces in the Cotentin and those east of the Taute River, the lodgment had a depth of only five miles. Farther west the enemy still held the base of the Cotentin to St. Lô–d’Ourville. Confined in a relatively small area and confronted with difficult terrain and an inadequate road network, First Army needed elbow room and more advantageous ground in which to employ its growing forces more effectively. Farther south the terrain became increasingly favorable for offensive maneuver, but to reach it the American forces had to penetrate a belt ten to twenty miles deep which continued to favor the defender. For four tortuous weeks the First Army fought through this Normandy hedgerow country to win additional maneuver room and to gain the terrain considered essential as a line of departure for a general offensive. (Map 14)

After considerable regrouping which included the transfer of the VII Corps from Cherbourg to a position between VIII and XIX Corps, and after minor preliminary operations in the zones of the two latter corps designed to improve their positions, First Army was ready to launch its attacks on 3 July. Its objective was the general line Coutances–Marigny–St. Lô. First Army at this time comprised the VIII, VII, XIX, and V Corps, in line from west to east, with a total of twelve divisions operationally available. Since the attainment of the objective involved the greatest advances on the right (west), the army planned to have VIII Corps make the initial attacks southward along the coast, The offensive would then widen progressively eastward in a succession of blows by the VII and XIX Corps, each attacking on army order, with the whole front pivoting on V Corps, east of St. Lô.

In accord with these plans the VIII Corps (82nd Airborne and 79th, 90th, and 8th Infantry Divisions) opened the First Army offensive on 3 July with a three-division attack toward La Haye-du-Puits and the Forêt de Mont-Castre hills. The three divisions encountered strong resistance from the start. Favored by the terrain, the

map 14: Tactical progress, U.S. Forces, 1–24 July 1944

enemy met the attacks with heavy machine gun and mortar fire from well dug in positions on the hills that dominated the approaches to La Haye-du-Puits. In addition to the inevitable hedgerows, rain plagued the attackers almost every day, confining movement to the roads, limiting air support, and restricting observation. Persisting in their attacks, and repeatedly counterattacked, VIII Corps units inched forward, covering about 6,000 yards in the first three days. They finally captured La Haye-du-Puits on 8 July. Beginning on the 10th the attacks began to move faster against diminishing resistance, and by 15 July VIII Corps units had reached the northern slopes of the Ay River valley.

There First Army ordered its men to halt their advance, and they consolidated their positions while awaiting the outcome of action farther east. In twelve days of severe fighting the corps had advanced approximately eight miles, and was still twelve miles short of its objective, the high ground at Coutances.

The hard experience of the VIII Corps was typical of the fighting which took place along the entire front. On army order the VII Corps (4th, 9th, and 83rd Divisions) joined the attacks on 4 July. Hemmed in on one side by the Prairies Marécageuses and on the other by drainage ditches and tributaries of the Taute River, the VII Corps attack was channelized

down a narrow corridor only a few miles wide which offered no room for maneuver and first permitted the employment of only one division (the newly arrived 83rd). Moving generally astride the Carentan–Périers highway, the attacks ran into defenses organized in great depth by an enemy expecting the major effort in this sector. As in the VIII Corps area, gains were measured in yards.

By 6 July it was possible to commit an additional division—the 4th—on the VII Corps front, and three days later the corps left boundary was shifted eastward so that the 9th Division could also be employed. Fighting for every field against determined resistance, the 4th and 83d Divisions gradually pushed the enemy back along the axis of the Carentan–Périers highway and by 15 July captured the slightly higher ground at Sainteny. From there the approach to Périers narrowed into a corridor less than two miles wide, with streams on both flanks restricting all maneuver. Further advance in this sector was therefore halted.

Meanwhile in the eastern sector of the corps front the enemy launched a strong counterattack with armor and momentarily forestalled the 9th Division’s threatened breakout from its constricted area east of the Taute. After repulsing the German attack, the 9th Division made substantial gains and fought its way across the Tribehou–St. Lô highway, putting still another tributary of the Taute behind itself.

At the same time the 30th Division (of the XIX Corps) had been advancing abreast of the 9th just west of the Vire River. The 30th had inaugurated the XIX Corps attack on 7 July by seizing a bridgehead over the Vire and, followed by elements of the 3rd Armored Division, had expanded its crossing west and south. To bring all these operations between the Vire and Taute under one command, First Army now shifted the VII Corps boundary still farther east—to the Vire—thus bringing the 30th Division also under VII Corps control. In the next few days the 9th and 30th Divisions extended their gains a few miles more, almost reaching the St. Lô–Périers highway. While these positions were several miles short of the objective originally assigned at the beginning of July, VII Corps units had at least advanced through the worst of the maze of rivers, marshes, and canals which had hindered movement on every side.

East of the Vire the last of the series of drives along the army front got underway on 11 July. The attack of the XIX Corps (29th and 35th Divisions), in which the 2nd Division of the V Corps also took part, was aimed at the capture of the ridges along the St. Lô–Bayeux highway and finally at St. Lô itself. Both the 29th and 2nd Divisions made satisfactory gains on 11 July and won positions on the ridge that dominated St. Lô from the east. In the next few days the corps encountered the same determined resistance which had been met in other sectors. It plodded forward suffering heavy losses in routing the enemy from well-prepared positions. After a temporary lull on 14 July the corps resumed its attacks and with unrelenting pressure forced the enemy to give way. Finally on the 18th the two divisions of the XIX Corps closed in on St. Lô from both the north and east, and a special task force from the 29th Division captured the city the same day.

The fall of St. Lô concluded a period of the most difficult fighting the American forces had seen thus far. Favored by endless lines of natural fortifications in the characteristic Normandy hedgerows, and aided by almost daily rains which nullified

Allied tactical air support and reduced observation, an enemy inferior in numbers and deficient in supplies and equipment was able to contest virtually every yard of ground. For the American forces the period proved costly in the expenditure of ammunition and in casualties among their infantry.

The Normandy Supply Base

While the problem of maintaining an adequate flow of men and supplies across the Channel was due chiefly to difficulties at the beaches, which resulted in a shortage of shipping and played havoc with the entire marshaling process in the United Kingdom, the logistical problems in the continental lodgment area were due chiefly to the lag in tactical operations. Progress had not been as rapid as hoped, and on 1 July the front lines were approximately sixteen days behind the phase lines drawn into the OVERLORD plan.

The retarded advance had inevitable repercussions on logistic plans. Because Cherbourg had not been captured and put into operation as scheduled, port plans had to be reconsidered. Because lines of communications were short and the fighting in Normandy had become a struggle for hedgerows, requirements for both supplies and troops differed from those originally anticipated. Because the lodgment area throughout June and July remained small and congested, neither the continental administrative organization nor depot structure could be developed as planned. In short, the lag in tactical progress directly influenced the whole development of the Normandy supply base in the first weeks and determined not only its physical appearance but the nature of its operations and its organizational structure.

By 25 July the Allied lodgment was to have extended southward to the Loire, eastward to a line running roughly through Le Havre and Le Mans, and westward into the Brittany peninsula as far as Lorient–St. Brieuc, covering an area of almost 15,000 square miles. Instead, the lodgment on that date consisted of only the Cotentin peninsula and a shallow beachhead with an average depth of twenty miles south of OMAHA and the British beaches. It covered an area of only 1,570 square miles, smaller than the state of Delaware and only one tenth of the planned size. The flow of men and supplies had continued apace, and the troop strength on 25 July was only slightly smaller than the planned build-up.

The first effect of the restriction in space was felt in the development of the depot system. OVERLORD administrative plans specified that the Advance Section should assume responsibility for the development of the supply base in Normandy after the initial two weeks of First Army control. In accord with these plans the Advance Section, after careful map reconnaissance, had tentatively chosen sites for every installation and unit and had allocated space so as to minimize conflict between the various services and facilitate the orderly development of a maintenance area. With a few exceptions the selected locations worked out successfully in the upper Cotentin, which was evacuated by the tactical units and made available to the Advance Section shortly after the capture of Cherbourg.

The development of the areas inland from the beaches proved more troublesome. The principal difficulty arose because the front lines were too close to the beaches. Contrary to plan, it was impossible to establish an army service area for-

ward of the beach maintenance areas. Truckheads, ammunition supply points, and advance dumps were moved forward as the situation required, south from OMAHA and west and southwest from UTAH, but the beach maintenance areas continued as the main depot areas throughout the first two months of operations. While the intake capacities of the beaches were enlarged, the maintenance areas remained relatively static in their growth because the lodgment could not be expanded. The result was that division, army, and ADSEC units and installations were telescoped into an area only a fraction of the size planned, and supply operations suffered an increasingly chronic congestion.

Development of the depot plan consequently was not as orderly as it was planned to be, and it was necessary to use open fields for storage to a far greater extent than was desirable. Fortunately the ground was for the most part well turfed. But the fact that most of the Normandy terrain was divided into small fields by thick earth embankments topped with hedges made it necessary to punch holes in the hedgerows in order to provide access for trucks. The usual practice at first was to stack supplies along the edges of fields to take advantage of the partial concealment which the hedges and trees afforded. The congestion became so bad in July, and the almost daily rain during that month created such muddy conditions, that more and more supplies were simply stacked in the middle of open fields to simplify the handling problem. Most camouflage efforts were abandoned in view of the light enemy air activity. Covered storage was largely nonexistent. Virtually the only such facilities were provided by the Amoit Aircraft Plant at Cherbourg, which was used as an ordnance Class II and IV depot, and by a large dirigible hangar near Montebourg, which was used as an ordnance maintenance shop. A small amount of inside storage for rations was also available in Cherbourg. Supplies received at OMAHA Beach, Isigny, Grandcamp, and Carentan flowed into a dump area south of Trévières. UTAH’S intake was generally sent to the Chef-du-Pont area. But to the casual observer it appeared by the end of July that almost every field in the lodgment was occupied by some type of supply or service installation.1

The crowding and congestion affected supply operations in various ways. The storage of ammunition, for example, was a matter of special concern since Class V supplies had to be adequately dispersed. In mid-July an explosion and fire destroyed more than 2,000 of the 50,000 tons of ammunition held in the large depot near Formigny.2 The delayed capture of Cherbourg, meanwhile, had its effect on the handling of Transportation Corps supplies. Plans had been made for the establishment of TC depots in Cherbourg rather than in the beach areas, with separate installations for railway supplies such as locomotive and car parts, and for marine supplies, including hand tools, rope, cable, and lifting gear. This equipment was scheduled for early shipment to the Continent, and when it arrived too soon to be received at Cherbourg it was taken into engineer and ordnance depots. A considerable quantity of equipment for both the

4th and 11th Ports was landed on the wrong beaches or at Barfleur and Isigny and lay there for a month before being recovered from an engineer dump. Poor documentation and improper packing contributed to the misdirection and even loss of some equipment. With the establishment of a TC depot at Bricquebec about D plus 30 this situation gradually began to improve.3

Traffic congestion was a natural concomitant of the confinement to the shallow lodgment area. The road net in Normandy was extensive enough, but was hardly suited to heavy military traffic. Most of the routes were narrow country roads with deep ditches and hedges that hampered two-way traffic, particularly in rainy periods. There were six or seven good hard-surface (macadam) routes leading southward from the Cotentin and from the OMAHA area, and there were good lateral routes in both beach maintenance areas. Even the metaled roads were often narrow, however, their edges soon crumbling under the constant pounding of the 2½-ton 6 x 6’s, and required constant mending by engineer road repair crews.

Traffic was particularly heavy in the OMAHA area because of larger tonnages discharged there. Many of the supply dumps lay astride the main lateral highway, which was a few miles inland from the beach and was intersected by all the routes leading inland. As the principal connecting link with the UTAH area at the base of the Cotentin, this highway bore a tremendous volume of traffic. There were at least four intersections in the lodgment area where more than a thousand vehicles passed a given point every hour during the periods of peak activity. At Formigny, the site of the large ammunition depot and the point where the main road from the beaches to St. Lô crossed the principal lateral artery, and at the main junction point between Isigny and Caren-tan, there was an hourly flow of almost 1,700 vehicles during the most active period of the day in mid-July. On 18 July a traffic count revealed that the bridge between Carentan and Isigny accommodated 14,434 vehicles in the hours between 0600 and 2100.4

Normal stoppages to permit cross traffic at important intersections often backed up traffic bumper to bumper for a mile or two and made it necessary to construct traffic circles and establish one-way routes through such bottlenecks as Ste. Mère-Eglise and Isigny. Choked with vehicles, the Normandy roads would have presented a remunerative target for a more active enemy air force. Only because of Allied air supremacy was it possible for this tremendous volume of traffic to continue relatively unmolested and in open violation of normal road discipline.

Trucks handled nearly all transportation in the lodgment in June and July. At the end of July nearly 30,000 tons of supplies were being cleared from the beaches and small ports every day, mostly by the truck companies of the provisional Motor Transport Brigade which the Advance Section had organized just before D Day. Rail transportation played a negligible role in these early months, although not because of any failure to rehabilitate the existing network. The delay in capturing and restoring Cherbourg ruled out the plan to

have that port receive railway equipment and rolling stock by D plus 25, but reconnaissance of portions of the main line running from Cherbourg to Carentan and southeastward began within a week of the landings, sometimes under fire. The 1055th Engineer Port Construction and Repair Group began to rehabilitate the Carentan yards on 17 June, shortly after the capture of the town. A few days later repair work was undertaken at Lison Junction to the southeast, and later at Cherbourg, where the destruction had been the greatest. By the end of July four rail bridges had been repaired and 126 miles of rails were in operating order, including the double-track line from Cherbourg to Lison Junction, and single-track branch lines from Barfleur and St. Vaast and from St. Sauveur-le-Vicomte. (See Map 17.) The first scheduled run between Cherbourg and Carentan was made on 11 July by a train operated by the 729th Railway Operating Battalion, a unit sponsored by the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad.5

Although the supply of rail equipment and construction materials was not entirely satisfactory, restoration of existing lines had progressed as far as the tactical situation permitted.6 Until the end of July, however, conditions in the lodgment made the use of railways uneconomical. Distances were short, and rail transportation would have involved multiple handling and initial hauls by trucks in any event. No freight of any consequence, therefore, was hauled by this means.7

Except for the congestion on the highways, transportation posed no serious problem in the first two months. At the end of July the Advance Section had ninety-four truck companies available for use on the Continent. While the number was considerably short of the 130 companies planned for that date, it was more than ample for the hauling requirements on the relatively short lines of communications at that time.8

The disappointingly slow tactical advance in July and the resulting claustrophobic confinement of the lodgment also had a direct bearing on the development of the administrative command and organizational structure on the Continent. One of the key factors in the evolution of the logistic structure was the question of when the army rear boundary should be drawn, for it was at that point that the Advance Section would be detached from the army and begin to operate as an advance echelon of the Communications Zone. In the plan it was assumed that the switch would occur between D plus 15 and 20. Another important factor was the matter of the introduction of a second COMZ section, which was to take over the Rennes–Laval–Châteaubriant area from the Advance Section and eventually organize Brittany as a base, for this step was to bring the Forward Echelon into active command of the Communications Zone. Both steps were of direct concern to the tactical command, for they involved the progressive surrender of its control over supply operations and the rear areas.

With the launching of OVERLORD the command structure agreed upon for the first phase had gone into operation, with First Army in command of all U.S. elements,

including the Advance Section. ADSEC troops and headquarters personnel began arriving on the far shore as early as D plus 1, and on 16 June the Advance Section announced the opening of its headquarters on an operational basis. Its staff maintained close liaison with opposite numbers in the First Army headquarters to prepare for the assumption of supply responsibility in the rear.

The question of drawing an army rear boundary arose almost immediately as the result of a request from General Eisenhower for information as to when it would be practicable to establish the Communications Zone on the Continent. General Lord promptly advised the theater commander that the transition could be made at any time, and that it was dependent only on General Bradley’s drawing of a rear boundary. He recommended that this be done at an early date, arguing that the Advance Section could relieve the army commander of a heavy administrative burden, and that the change would also result in better co-ordination of supply and service functions between the United Kingdom and the Continent.

But the First Army was reluctant to relinquish control of supply operations at so early a date and delayed action on the matter. The result was that the transition to ADSEC control of the rear area supply operations was very gradual, the army making piecemeal delegations of functions and transferring control of only a few installations at a time, meanwhile retaining over-all command of the entire lodgment. Instead of designating an army rear boundary First Army on 20 June established an ADSEC forward boundary, running along the road between Vierville-sur-Mer and Port-en-Bessin. By this ingenious device First Army assigned a narrow strip of land along the beach to Advance Section for its operations, but retained command of all forces on the Continent, with the Advance Section continuing to function as a major subdivision of the field army. While this did not accord with COMZ wishes, the Advance Section itself had no objection to the arrangement. It had established a close and friendly working relationship with First Army during the planning period, and, although a subcommand of the Communications Zone, actually felt a closer affinity with the armies throughout operations than with its parent headquarters.9

Had the plan been followed, an army rear boundary would have been drawn between 21 and 26 June (D plus 15–20), and the Forward Echelon would have assumed active command of the Communications Zone about 17 July (D plus 41). On the latter date, however, First Army was still attempting to break out of the difficult hedgerow and marécage country west of the St. Lô–Périers highway, 125 miles from the Loire. The crowded conditions which had militated against carrying out the arrangements for even the first phase still obtained.

The designation of a rear boundary was again considered in mid-July, and tentative plans were made to release most of the upper Cotentin and the UTAH Beach area to Advance Section. But action was again postponed, and instead the additional territory was assigned to the Advance Section by an extension of its forward boundary. The drawing of an army rear boundary in fact was not carried out until after the breakout from Normandy at the end of the month.10

The above developments had also altered the role of the Forward Echelon, Communications Zone, whose position in the command structure had occasioned so much debate. Plans provided for the establishment of Forward Echelon in two groups on the Continent—an advance group at St. Le) for the period when Forward Echelon functioned as part of the 21 Army Group staff, and a second group at Rennes for the later phase when Forward Echelon assumed actual control of the Communications Zone. The two were to merge into a single headquarters when the main COMZ headquarters arrived about D plus 90. The movement of Forward Echelon was to take place in six parties and was to be completed by about D plus 40. The actual movement was delayed somewhat, but the first echelon arrived on the Continent on 18 June and eventually located itself at Château Servigny, near Valognes. Additional increments crossed the Channel early in July and moved to Château Pont Rilly, also near Valognes. On 12 July Col. Frank M. Albrecht arrived and assumed direction of the group, General Vaughan having been relieved as deputy commander for the Forward Echelon and given a new assignment. This did not complete the displacement of the headquarters, however, for the operating party had by then been phased back for arrival early in August. In view of the course which tactical operations had taken, the original plans with regard to headquarters locations could not be followed, and the two châteaux near Valognes therefore became the headquarters of Forward Echelon, which officially opened on 15 July.

By that time the question of Forward Echelon’s role on the Continent had become closely tied up with the matter of drawing an army rear boundary, which the First Army had resisted in its desire to retain control of the lines of communications as long as possible. As time went on, however, the control of the increasingly complex supply operations on the Continent became a weighty responsibility, and the Communications Zone exerted increasing pressure to be allotted a definite sphere of responsibility. In an obvious attempt to allay First Army’s fears of any disadvantage attending Forward Echelon’s control of the lines of communications, COMZ headquarters early in July drew up a memorandum suggesting a delineation of function between the army commander and the Communications Zone. It stipulated that the senior field force commander would continue to control priorities in troop movements, that the Communications Zone would on request make available detailed information on the status of supplies, that the field force commander would retain control of allocations of scarce items of supply, that First Army would remain in control of all supply depots and distributing points in the beach area until separate army depots could be established, and that the Advance Section would continue to be the direct representative of the Communications Zone in all dealings with First Army.

While nothing came of this proposal, SHAEF stepped in in mid-July to institute the transitional phase in the command setup without drawing an army rear boundary. On 14 July Advance Section was finally detached from First Army and turned over to the control of the Commanding

General, Communications Zone, with the stipulation, however, that until SHAEF was established on the Continent General Bradley was to have final authority in all matters except conflicts over troop and supply priorities for the air forces. Thus, over-all control was to continue to rest with the senior field force command on the Continent, and, contrary to the view it had consistently held to before, the Communications Zone was at least in a transitional phase to be subordinated to the field force commander (at the moment the Commanding General, First Army, later the Commanding General, 12th Army Group, but in both cases the same person, General Bradley). Actually the SHAEF directive of 14 July did not materially affect the status of Advance Section, for its units were not officially relieved from attachment to First Army until 30 July. First Army therefore retained control of the entire U.S. zone until 1 August, when the Third Army and the 12th Army Group were introduced, although Advance Section was in effect the real Communications Zone on the Continent after mid-July.

Since the immediate administrative control of Advance Section had passed to Headquarters, Communications Zone, it would appear that the Forward Echelon should have become operational and taken control of the Advance Section at this time. But Forward Echelon’s continental mission was now radically altered. Forward Echelon had been formed in part to meet the expected interim need for an operational headquarters on the Continent in the belief that the main COMZ headquarters could not be moved across the Channel before D plus 90. In mid-July it was decided that there was no need for interposing such a command. In fact, with a breakout from Normandy a possibility, the desire to be closer to the scene of action and thus be able to guide the development of the expanding rear areas made good sense.

Actually, the decision to advance the transfer of that headquarters to the Continent was strongly influenced by another consideration. Despite the pretensions which the Communications Zone once permitted its offspring, Forward Echelon, to have, it began to grow apprehensive toward the end of July of the independence and authority which the Forward Echelon was beginning to display at Valognes.11 Accordingly, late in July Colonel Albrecht was ordered to prepare for the immediate reception of Headquarters, Communications Zone. In the next few weeks the headquarters at Valognes was greatly enlarged to accommodate the main body of the COMZ staff, and signal facilities were installed to permit communications with the United Kingdom, the United States, the subcommands on the Continent, and the field forces.

In the end, therefore, to carry the story forward a bit, the organization whose authority and role had occasioned so much controversy and aroused so many suspicions was destined to be merged with Headquarters, Communications Zone, without ever becoming operational as intended, chiefly because the main headquarters moved to the Continent in the first week of August, a full month earlier than planned. So far as its continental activities were concerned, Forward Echelon was a stillborn organization.

At the end of the war a board of officers rendered a harsh judgment on Forward Echelon, asserting that its establishment “created confusion and misunderstanding at all levels and interfered with logistical

planning for Continental operations.” But Forward Echelon, as shown earlier, made a significant contribution in coordinating the logistical planning for OVERLORD, and although its performance on the continental stage was restricted to a walk-on role, that role was the useful one of advisory agency for Headquarters, Communications Zone, and insurer of continuity of action for that headquarters on the Continent.12

Attempts were also made in the first two months of operations to clarify the relationship between COMZ-ETO and Supreme Headquarters. General Eisenhower’s directive of 6 June had not definitely settled the issue of the role of the U.S. component of the SHAEF staff vis-à-vis the COMZ-ETO staff.13 The continued assumption by American officers at SHAEF that they were to be the theater commander’s staff and carry out theater functions led to several conferences after D Day. On 9 June Maj. Gen. Everett S. Hughes, as the personal representative of General Eisenhower, met with General Lord and reaffirmed the principle announced earlier that the theater functions assumed by the SHAEF staff should be kept to a minimum. General Hughes assured General Lee’s representative that the intention of the Supreme Commander’s letter of 6 June was to reduce the U.S. activities at SHAEF to the point where the Communications Zone would be paramount within the defined sphere of administration and supply. General Smith had agreed, observing that the American staff officers at SHAEF had all they could do to carry out their duties in connection with Allied matters. General Eisenhower expressed the same views in a personal conference with General Lee, and on 20 June he issued an additional memorandum enjoining the two staffs to observe established channels of responsibility and authority.

General Lee at that time still held the position of deputy theater commander, for this arrangement had not been terminated on 7 June when the SOS officially became the Communications Zone. The designation was finally dropped on 19 July, when General Eisenhower further amplified his earlier directive regarding the relative positions and authority of Headquarters, COMZ-ETO, and SHAEF. Except for this change the delineation of authority did not differ materially from that of earlier pronouncements. Under it the theater commander, as before, noted that he would from time to time delegate to the three major commands of the theater—the 1st Army Group, the Communications Zone, and USSTAF—responsibility and authority for certain matters normally reserved to himself. The determination of broad policies, objectives, and priorities affecting two or more of these commands was to be reserved to the theater commander under all circumstances, and in exercising these functions he announced that he would utilize the U.S. element of SHAEF and the chiefs of the special staff. The latter were to be located as directed by the Commanding General, Communications Zone, however, and they were to report to the latter and be responsible to or through him for the execution of all COMZ and theater duties. The Communications Zone remained the theater channel of communications with the War Department on all technical and routine matters.

Since the July memorandum terminated General Lee’s position as deputy theater

commander it appears that one of its purposes was to take away from the COMZ commander his theater prerogatives and establish the Communications Zone as coequal with the other two major commands. Although General Lee no longer exercised his prerogatives as deputy theater commander, however, the change did not alter existing responsibilities or channels of command nor the manner of doing business, and General Lee continued to regard his headquarters as theater headquarters even after movement to the Continent. The Communications Zone still remained the channel of communications with the War Department on technical and routine matters, the chiefs of services continued their residence at the COMZ headquarters, and General Lee’s general staff was still officially the theater general staff except that the U.S. officers at SHAEF were to advise General Eisenhower on problems which he reserved for himself.

General Eisenhower apparently was desirous of preserving as far as possible the established integration of supply and administrative matters in the theater, and he spelled this out in even greater detail in a memorandum issued a few days later. To avoid confusion in the utilization of the special staff at Headquarters, Communications Zone, he cautioned that “all of us in SHAEF must channel our communications through General Lee, or through his general staff, if he prefers it that way. Since we impose upon the Commanding General, L[ine] of C[ommunications], all theater duties except those of decision and policy wherein some major difference arises between two of our principal commands, we must carefully avoid interfering with his methods and subordinates.”

On the other hand, the Supreme Commander noted that it was impossible completely to separate American from Allied interests, and in the interests of economy in the use of personnel he announced that he would continue to use the senior U.S. officers in each of the various staff sections at Supreme Headquarters as advisers on U.S. matters that required the theater commander to take personal action. These officers he regarded as convenient agents for advising him when necessary, and for following up on matters of particular importance, but the SHAEF general staff officers were not to be regarded as part of the theater general staff. Finally, General Eisenhower thought it essential that “whenever any subject pertaining to American administration comes under consideration by the SHAEF staff, careful coordination with General Lee and his staff be assured,” particularly when communication with the War Department was contemplated.14

That the relationship thus outlined was not so clear cut as might have been desired was probably an unavoidable result of the dual position which General Eisenhower held. Basically, the theater commander was using the staff of the Communications Zone to do the normal job of a theater staff. The smooth functioning of this setup unquestionably required a high degree of mutual co-operation and co-ordination between the two headquarters. In passing General Eisenhower’s memo on to the U.S. element of the SHAEF staff General Smith underscored this point in noting that every precaution must be taken to insure that the COMZ staff be “kept well in the general picture,” and that “short cuts which might confuse or militate against the effective

use of the L of C staff in its administrative functions must be carefully avoided, and full coordination must be assured.”15 The COMZ staff was likewise asked to be careful to consult the SHAEF staff on all matters of Allied interest.

The delineation of responsibilities appears to have been as distinct as could be made at the time. It was admittedly not an ideal arrangement, and there was continuing friction between the COMZ and SHAEF staffs over jurisdiction in supply and administrative matters, and between the Communications Zone and the field commands over the handling of supply in general.16

The Status of Supply

Despite the difficulties over cross-Channel movements, the delay in the capture of Cherbourg, and the congestion of the lodgment, the actual delivery of supplies to the combat forces in June and July was generally satisfactory. The shortages that developed did not reach critical proportions in these first seven weeks, and certainly were not serious when compared with the difficulties that developed in later months. Fortunately, the unfavorable developments of this period were at least in part offset by factors that proved much more favorable than anticipated: lines of communications were short; the lack of interference from the Luftwaffe obviated the requirement for elaborate camouflage and dispersion measures in the rear areas; destruction, except at Cherbourg, was considerably less than expected, particularly of the railways; the utilization of captured supplies, especially signal and engineer items, helped considerably to compensate for the lag in receipts; and consumption rates of certain items, particularly POL, were lower than expected, helping offset deficits in planned discharges.

There was no difficulty with Class I supply in the first two months, although the issue of rations was not in the proportions planned and not to everyone’s taste. American troops had read many times that they were the best-fed soldiers of all time. But while their rations differed vastly from the hard tack and beef stew issued to the soldier in the Spanish-American War, and from the corned beef, baked beans, bread, and canned vegetables of World War I, American soldiers were hardly convinced of their palatability. Army cooking was something they wrote home about, but not always in a complimentary vein.

By the time of the Normandy invasion the Quartermaster Corps was issuing five major types of combat rations. The C ration, as developed up to that time, consisted of six cans (each of twelve fluid ounces’ capacity), three containing meat combinations (either meat and vegetable hash, meat and beans, or meat and vegetable stew), and three containing biscuits, hard candy, cigarettes, and either soluble coffee, lemon powder, or cocoa. The entire ration (three meals) weighed approximately five pounds, could withstand a temperature range of 170°, and could be eaten either hot or cold. Although touted as “a balanced meal in a can,” the C ration was not popular until new combinations were added early in 1945 to give it considerably more variety.

The K ration was better packaged and, according to the theater chief quartermaster, more popular in the early months of

fighting, although the validity of this conclusion is debatable. As finally standardized it consisted of a breakfast unit, made up of meat and egg product, soluble coffee, and a fruit bar; a dinner unit, containing cheese product, lemon powder, and candy; and a supper unit with meat product, bouillon powder, and a small D-ration chocolate bar. In addition, each unit had biscuits, sugar tablets, chewing gum, and a few cigarettes. The idea for the K ration was suggested by a concentrated food of the American Indian known as pemmican, made up of dried lean venison mixed with fat and a few berries pressed into a cake. Variants of pemmican had been used by Arctic and Antarctic explorers, and experimentation with a similar product, beginning with tests at the University of Minnesota in 1940, eventually resulted in a standardized ration in 1942. The ration was originally designed for airborne and armored units and for other troops engaged in highly mobile operations. It was well packaged, each meal’s perishable component being hermetically sealed in a small can, and the other items in a sealed bag. Each unit was enclosed in an inner carton dipped in wax, plus an outer cardboard box, and the three packages were of convenient size to be pocketed. Both the C and K rations were individual rations and were intended to be used only for short periods of time when tactical conditions prevented better arrangements for feeding.

Meanwhile, experimentation begun before World War I had resulted in the adoption in 1939 of a supplementary field ration, the D ration. This was known at first as the Logan Bar, named for Capt. Paul P. Logan, who had developed it in 1934–36 while head of the Quartermaster Subsistence School. Its main component was chocolate, although it also contained powdered skim milk, sucrose, added cacao fat, oat flour, and vanillin. Strictly an emergency food, the D ration was intended to sustain men for only very short periods of time under conditions in which no means of resupply was possible.

Finally, mainly as a result of British experience in North Africa, and suggested by the successful British 12-in-1 composite pack, two types of composite rations known as 5-in-1 and 10-in-1 had also been developed, each unit containing sufficient food for five or ten men. These rations contained a considerably greater variety of food and were put up in five different menus. A sample 10-in-1 menu contained premixed cereal, milk, sugar, bacon, biscuits, jam, and soluble coffee for breakfast; ten K-ration dinner units; and meat stew, string beans, biscuits, prunes, and coffee for the supper meal. The 10-in-1’s also contained a preserved butter which, in deference to a well-known brand of lubricants, the troops quickly dubbed “Marfak No. 2.” Considerable controversy over the adequacy of its caloric content attended the development of the composite ration. It was developed for use over longer periods than either the C or K ration, for troops in advance areas that could not be served by field kitchens, and for troops in highly mobile situations. It was well suited for bridging the gap between the C and K rations and the B ration, the normal bulk ration which was intended to be served over long periods of time in the field. The B ration was essentially the garrison or A ration without its perishable components.17

The OVERLORD administrative plans provided that men in the assault stages

would personally carry one D and one K ration. Their organizations were to carry an additional three rations per man, either C or K. Maintenance shipments in the first few days were to consist wholly of C and K rations, but after the fifth day 50 percent of the deliveries were to be in 10- in-1’s. After the first month of operations half the subsistence was to be in B rations, about one quarter in 10-in-1, and the remainder in C and K. In actual practice there was considerable departure from the plan after the first few days. Rations were delivered to the Continent principally in prestowed ships loaded in New York weeks before the invasion, each vessel containing from three to eight 500-ton blocks. In this way approximately 60,000,000 rations were delivered in the first four weeks of operations. The shift to 10-in-1 rations, however, was more rapid than contemplated, and in the first four weeks approximately 77 percent of all issues were of this type, at the expense of the less popular C’s and K’s. Early in July, as planned, came the shift to the B ration, starting with issues to about 57 percent of all troops on the far shore. By that time the operational ration was already being augmented by the issue of freshly baked white bread, which began on 1 July, with one static bakery (at Cherbourg) and seven mobile bakeries in operation. As was the case with the 10-in- 1’s. the change-over to type B was more rapid than planned. By mid-July more than 70 percent of all troops were receiving the B ration.18

Experience with the C, K, and 10-in-1 rations in the first two months of operations produced mixed reactions. The 10-in-1 was undoubtedly the best liked initially. Troops found the C ration monotonous with its indestructible biscuits and its constant repetition of meat and vegetable hash, meat and beans, and meat and vegetable stew. But whether the C or the K was least popular is debatable. The demand for one or the other was influenced at least in part by convenience in handling. The K ration was the handiest for the man on foot; headquarters organizations and units with adequate transportation and heating facilities tended to prefer the C ration. All three had one component which was the subject of universal derision—powdered lemon juice. Showing little concern as to whether they received the proper amount of ascorbic acid in their diet, troops consistently disposed of the powder in ways not intended by quartermaster dietitians, either. discarding it or combining it with liberated spirits in new tests of inventiveness.

Early in July the almost universal demand for more coffee in the menus, and for improvement of the biscuits, particularly in the C and 10-in-1 rations, led the chief quartermaster of the ETO to request improvement in the packaged rations, including an augmentation of their nutritional value. Eventually all rations were greatly improved in palatability by the introduction of a considerable variety of foods, but these changes were not to appear until early in 1945.19

Difficulties in Class II and IV supply arose either from shipping delays or from unexpected maintenance and consumption factors in the fighting of the first two months. Engineer supply was generally adequate, though only because captured stocks of construction materials were extensively

used. Delivery of construction materials suffered from the initial lag in tonnage discharges, and receipts also fell behind because of the inability to receive them at Cherbourg, where mine clearance took much more time than expected. Fortunately a large portion of the construction materials required in the rehabilitation of Cherbourg could be procured locally or from captured stocks. Large quantities of cement, lumber, concrete mixers, and small items of equipment and supplies were found in the Cotentin.20 Huge rafts of timber piling were towed across the Channel for use in the reconstruction of the ports.

One engineer supply shortage that could not be solved locally was in maps. Allowances were found to be quite inadequate, partly because of the slow tactical progress, for the relatively static conditions of July occasioned demands beyond all expectations for large-scale (1:25,000) maps. Most of these demands were met by air shipments from the United Kingdom.21

Signal Corps supply followed the same general pattern as Engineer supply. The delivery of Signal Corps construction materials also lagged because of transportation difficulties. But the deficiency was largely made up by the capture of construction supplies and the discovery of enemy equipment in only slightly damaged condition. Shortages developed in certain types of radios because of losses in the landings, but these were made good by express shipments via both air and Water. The major supply problem was lack of information as to location of Signal Corps supplies aboard ships arriving off the beaches.22

Shortages of ordnance Class II and IV equipment resulted either from losses in the landings or from the nature of operations. Enemy action and mishaps in unloading at the beaches caused immediate shortages in 105-mm. howitzers, medium tanks, jeeps, and multigun motor carriages. Some of the lacks were rectified by priority call on the United Kingdom for replacements. Perhaps the most unexpected shortages occurred in mortars, light machine guns, BAR’s,23 and grenade and antitank rocket launchers.

The Normandy hedgerow fighting took an unprecedented toll of these weapons. The heavy losses in BAR’s—835 in First Army in June, or one third of the total number authorized—were attributed mainly to the special effort which enemy infantrymen consistently made to eliminate the BAR man in the American rifle squad.24 The shortage of grenade launchers was laid to the fact that the M1 rifle could not be fired automatically with the launcher attached. Many launchers were lost when they were removed, and in mid-July First Army reported a shortage of 2,300.25

The delay in the arrival of ordnance troops and bulk shipments of supplies was felt keenly, especially since an accelerated build-up of combat units caused available reserves to be expanded at rates far greater than anticipated. The shortage of at least one item, the 2.36-inch rocket launcher, was met by having service organizations

turn their weapons over to combat units.

Vehicle maintenance was not a serious problem in the first weeks, undoubtedly because most vehicles were new. But shortages of spare parts began to give trouble as early as July, when First Army had its first troubles with cannibalization, particularly of certain types of tires.26 At the end of July, on the basis of its first two months’ experience, First Army recommended upward revisions of replacement factors for forty ordnance items.27

The first weeks of fighting also produced reports on the quality of U.S. equipment, particularly combat vehicles. The inferiority of the 75-mm. gun on American tanks was recognized before the invasion, and remedial measures had already been taken. Before D Day the theater had received 150 tanks mounting the 76-mm. gun, which had somewhat better armor-penetrative power, and more shipments were expected during the summer months. In addition, there had been a limited authorization of tanks mounting the 105-mm. howitzer. General Bradley, aware of the limitations of both the 75-mm. and 76-mm. gun, had indicated in April that the 105-mm. howitzer and the still newer 90-mm. gun motor carriage (the M36 tank destroyer), which was not yet available, might well become the logical successors to the 75 and 76 respectively to meet the dual requirement for a gun with superior high-explosive qualities and an armor-piercing weapon capable of engaging hostile armor.

The first few weeks of combat on the Continent made it abundantly clear that the 75-mm. and 76-mm. guns were no match for the enemy’s Panthers (Mark V’s) and Tigers (Mark VI’s), and on 25 June Brig. Gen. Joseph A. Holly, chief of the ETOUSA Armored Fighting Vehicles and Weapons Section, was called to the Continent to meet with senior combat commanders and determine the details of their requirements. Shortly thereafter he went to the United States to obtain expedited shipment of the maximum number of both the 105-mm. and 90-mm. weapons. Meanwhile General Eisenhower himself reported the inferiority of American tank armament to the War Department, and made an urgent request for improved ammunition and weapons. The War Department agreed to expedite the shipment of the new 90-mm. gun tank destroyer and released the first hundred to the New York Port early in July. In the meantime the only immediate action-that could be taken within the theater was to dispatch to the far shore fifty-seven of the new medium tanks equipped with 105-mm. howitzers, which had just been received in the United Kingdom.28

The status of POL (Class III) supply in June and July was entirely satisfactory. Plans for the delivery of gasoline and other petroleum products proved quite adequate in view of the slow rate of advance, the short lines of communications, and the resulting low consumption. Bulk deliveries of gasoline were scheduled to begin on D

plus 15, but construction of the Minor Pipeline System was delayed by difficulties in delivering construction materials, all of which had to arrive over the beaches or through Port-en-Bessin. POL construction materials were mixed with other cargo on several vessels and, in the early confusion and competition for priorities, did not arrive as scheduled. A limited quantity of materials was gathered together very shortly, however, and, the 359th Engineer General Service Regiment began work on D plus 7, although many needed fittings were still unavailable. Just before D Day, when the discovery of additional enemy forces in the invasion area indicated that the capture of Cherbourg would be delayed, thus enhancing the importance of the Minor System, 21 Army Group had fortunately made a special allocation of LCT lift to bring in additional construction materials. This cargo began arriving on D plus 9 and was routed to Port-en-Bessin, where it was promptly unloaded.29

The POL plan benefited by another favorable development. Previous intelligence had indicated that only the east mole at Port-en-Bessin could be used for discharge and that only small tankers of 350 tons capacity could be handled. On arrival the Allies found that both the west and east moles could be used, one for the British and one for the Americans, and that tankers of up to 1,300 tons’ capacity could be received. Eventually it was therefore possible to develop intake capacity of some 2,000 tons per day instead of the 700 originally estimated. This was most fortunate in view of the increased burden put on the Minor System during the prolonged period required to clear the port of Cherbourg.

Meanwhile construction of the facilities at Ste. Honorine also proceeded, although plans for a third TOMBOLA were canceled because of terrain difficulties. Operation of the two underwater lines was actually restricted to fair weather because of difficulties in mooring tankers and connecting pipeheads in rough seas. Reconnaissance of the port areas shortly after the landings also resulted in some change in the siting of the tank farms. Many of the sites selected from contour maps before the landings were unsuitable, primarily because of unfavorable gradients. The number and size of tanks placed at the ports were therefore held to a minimum, and the main storage was sited on better ground at Mt. Cauvin, near Etreham.

Construction of the pipeline inland from Ste. Honorine was delayed somewhat by the necessity of clearing thickly sown minefields in the area. Several casualties were sustained in this operation, but losses were undoubtedly kept down thanks to information provided by a former French Army captain on the location of mines both inland and offshore. He had witnessed the sowing from his home near the beach.30

Construction of the Minor System progressed steadily and was far enough along for the 786th Engineer Petroleum Distributing Company to begin operations on 25 June, when the first bulk cargo of MT80 was received, about nine days behind the planned schedule, at the Mt. Cauvin tank farm. (See Map 16.) More than enough packaged gas was on the far shore to bridge the gap, inasmuch as vehicular mileage had been much less than expected

in the limited area of the lodgment.31

Because of the delay in the capture of Cherbourg the Minor System assumed even greater importance than expected. It was expanded beyond the original plans after the port was captured because the number of obstacles in the harbor promised to delay still further the use of the Querqueville digue for tanker deliveries. Pipelines were extended from the Mt. Cauvin tank farm to St. Lô for both MT80 and Avgas, and a branch line for Avgas was laid to Carentan to take advantage of existing facilities there. Eventually the Minor System had seventy miles of pipeline instead of the planned twenty-seven. Additional tankage was also constructed to give the system a storage capacity of 142,000 barrels instead of the planned 54,000. Because of rough sea conditions at the OMAHA beach fueling station, the Ste. Honorine-des-Pertes installation was not used by the Navy as intended, but was turned over to the Army to be used exclusively as an MT80 receiving and storage terminal.32

The Minor System was intended to deliver a total of about 6,000 barrels per day of MT80 and Avgas combined. By the end of July the output was double that figure.33 At that time the First Army was consuming about 400,000 gallons (9,500 barrels) of motor fuel alone each day.34 Though originally scheduled to have served its purpose by D plus 41, the Minor System was compelled by tactical conditions to continue in operation at maximum capacity for many weeks to come. For a twelve-day period in September its daily issues averaged 18,000 barrels.35

While the over-all supply situation was generally satisfactory in June and July, there was one major exception. Ammunition (Class V ) supply was a repeated cause of concern in this period and came nearest being a “critical” shortage in the sense of jeopardizing the success of operations, although, disturbing as it was, the situation was not serious when compared with later difficulties. Most of the trouble over ammunition supply arose not so much from excessive or unexpected expenditures as from difficulties in delivery of adequate tonnages to the Continent.

Ammunition supply became serious at the very start of the operation, particularly at OMAHA Beach. Scheduled landings of supplies had been upset by the loss of key personnel, vehicles, and equipment of the beach brigades. Fortunately the artillery, except for separate armored battalions, had not engaged in particularly heavy firing in the first days, and naval gunfire had given good support to ground units. Expenditures had actually been below estimates.36 But ammunition was not arriving at planned rates, and it was almost immediately necessary for the First Army commander to take emergency action in order to give high priority to the

beaching of ammunition vessels. By 10 June the situation had already improved somewhat.37

Nevertheless the ammunition supply picture was subject to frequent ups and downs in the first weeks. The initial shortages had developed in small arms ammunition and hand grenades, of which there was an unusually large expenditure in the hedgerow fighting. These shortages were relieved by air shipments from the United Kingdom.38 By the middle of the month ammunition stocks in general were far below planned targets, and steps were taken to give Class V supply, particularly field artillery ammunition, the highest priority, replacing scheduled shipments of POL.39 On 15 June restrictions on expenditure were imposed for the first time when First Army rationed ammunition by limiting the number of rounds per gun which could be fired each day by the two corps. Stocks were low in part because of nondeliveries. But rationing was resorted to mainly because corps and divisions had violated army directives in creating excessive unreported unit dumps at artillery positions. Lower units had stocked excessive amounts forward, reducing reserve stocks in army dumps and therefore under army control.40

A more serious threat to the whole ammunition position came in the period of the storm, when unloading virtually ceased. Special measures were taken at that time both to limit expenditures and to expedite deliveries of items in critical supply. First Army immediately limited expenditures to one-third unit of fire per day, and then arranged for air shipments of 500 tons per day for three days, ordered ammunition coasters beached, and called forward from U.K. waters five U.S. Liberties prestowed with ammunition.41 The shortage of field artillery ammunition was alleviated somewhat by employing tank destroyer and antiaircraft battalions in their secondary role as field artillery to perform long-range harassing and interdiction, for the expenditure of 90-mm. and 3-inch gun ammunition was not restricted.42

With the general improvement in the entire build-up after the storm, First Army on 2 July temporarily lifted the restrictions on expenditures. At the same time, however, army presented a table of expenditures which, on the basis of experience, it regarded as ample enough to allow its corps to accomplish their respective missions, and it directed that units conform on a corps-wide basis to expenditures at rates not to exceed one unit of fire in the initial day of an attack, one-half unit of fire on each succeeding day of an attack, and one-third unit of fire for a normal day of firing. Any expenditure in excess of these rates had to be justified to First Army within twenty-four hours. The new system eased the previous rigid restriction on the basis of rounds per gun per day and gave the corps more leeway in planning their operations, but the army warned that any abuse would result in a return to strict rationing.43

This limitation was in force for the next two weeks, during which the army made a succession of limited attacks with all four corps through the difficult terrain already

described. In effect, the army directive imposed very little restriction on firing, and “morale” firing by new divisions, plus increased depth and width of concentrations fired to compensate for poor observation, tended to increase expenditures. The result was a period of the most continuous heavy firing in the first two months. Reserves were depleted at the rate of .2 unit of fire per day, and depot stocks became insufficient to sustain the army’s allowed expenditure rate. The depot level of 105- mm. howitzer ammunition dropped to three and a half units of fire after having been built up to six units of fire earlier in the month.44 The stocks of 81-mm. mortar ammunition, which was the most critically short of all, were reduced to .3 unit of fire on 16 July.45

Aware that the situation was worsening, First Army on 13 July issued warnings about expenditures in hopes of avoiding a return to rationing. In a letter to the division and corps commanders, Maj. Gen. William B. Kean, the army chief of staff, noted that expenditures had been far in excess of the replacement capabilities of the supply services. He expressed doubt that the results had justified the heavy firing of the past few days.46

His warnings were insufficient. Three days later, on 16 July, army imposed a strict rationing system in order to rebuild reserves for the offensive operation then being planned. It now made detailed allocations that differed for each corps on the basis of the estimated scale of combat activity during the period covered by the allowance. Initially the allowance was for specific numbers of rounds per weapon on a day-to-day basis and permitted no accumulation from one day to the next.47

Combat commanders objected strongly, arguing that it was false economy to limit the expenditure of ammunition, for combat units consistently sustained fewer casualties and made better progress when artillery support was ample.48 Undoubtedly these restrictions did not represent the wishes of the army commander either.

The difficulties in replenishing the supply of ammunition were not at this time the result of shortages in the theater, although such shortages were to develop very soon. They were due rather to inadequate arrivals and discharges at the beaches.49 In mid-July ammunition was being unloaded at the rate of only 3,000 tons per day. First Army asked the Advance Section for a daily discharge of 7,500 tons, the amount which it insisted was necessary to maintain an adequate supply for the combat forces then on the Continent.50

After rationing was imposed in mid-July the ammunition situation improved rapidly. From the 16th to the 24th expenditures were actually less than rationing permitted. Firing was light, for the bulk of the artillery was held silent in new positions in preparation for the attack of 25 July.51 The shipping and discharge situation

also improved in this period, and as a result of the calling up of additional ammunition ships there were approximately twenty-nine vessels with a capacity of about 145,000 tons awaiting discharge off the beaches at the end of the month.52

The special express shipping services to the far shore to meet unexpected or unusual demands by the combat forces proved a farsighted provision. Arrangements had been made for shipments by both air and water, the latter being handled either as GREENLIGHT shipments, consisting of 600 tons per day of ammunition or engineer Class IV supplies, or as Red Ball shipments, under which 100 tons of supplies could be rushed to Southampton by truck and dispatched by daily coaster to the far shore. In the first eleven days of operations four GREENLIGHT, fourteen Red Ball, and ten emergency air shipments were made to the Continent, ranging in size from small boxes of penicillin to fifteen 105-mm. howitzers. In the first month more than forty special ammunition shipments were made, approximately one third of them by air. It had been estimated that requests for Red Ball shipments would be filled in from three to five days. At the end of July General Ross reported that up to that time the average elapsed time from receipt of requests to delivery had been eighty-nine hours (three days, seventeen hours).53 Although shipment by air was still in its early stages of development and did not account for a large portion of the over-all tonnages, it was particularly useful in meeting urgent demands for certain types of ammunition in the period of the storm. Approximately 6,600 tons of supplies were flown into the lodgment area during June and July.54

While the various express services operated satisfactorily to meet emergency requirements on the far shore, the supply system as a whole developed an undesirable rigidity and thus tended to bear out the misgivings voiced before D Day by General Moses, the army group G-4.55 Several factors contributed to its inflexibility, some of them inherent in the supply plan, some of them resulting from difficulties on the far shore. The prescheduling of supply shipments for the entire first three months imposed an initial strait jacket, for it placed a great burden on the U.K. depots and also resulted in the building up of unbalanced stocks on the Continent. The U.K. depots were hard put to prepare shipments of small quantities of many items for each day’s requisition and also meet sudden priority demands for shipments via GREENLIGHT, Red Ball, and air. On the Continent, meanwhile, the receipt of prescheduled shipments led to the creation of unbalanced stocks. Record keeping on the far shore was not sufficiently accurate to provide a true picture of supply stocks there. Since actual consumption rates and depot balances were not known, no attempt was made to alter requisitions to reflect real needs. Under these circumstances the far-shore commands found it easier to have their urgent requirements met by the various express services.

Selective unloading on the far shore created additional inflexibility, for it promoted forced idleness of shipping at the beaches, lengthened the turn-round time, and reduced the number of vessels returning

to the U.K. loading points. The net result was to increase the in-transit time for all supplies and to place a larger portion of the theater’s supplies in the pipeline. Once committed to movement an item was not available for issue until it was stocked in a depot on the far shore. The tonnages thus committed to the pipeline sometimes constituted a substantial percentage of the available theater stocks of certain items.

The ability of the supply system to respond to requirements depended largely on movement capabilities, which were always limited. Committing a large portion of the lift to prescheduled shipments, some of which were unnecessary, eliminated whatever cushion there might have been. In a postmortem of the OVERLORD supply plan after the war critics, agreed that the shipments of supplies on a daily basis could have been discontinued much earlier, and that the prescheduling of shipments for three months imposed an unnecessary rigidity on movement capabilities in view of the large percentage of theater stocks which were tied up as a result. Furthermore, had the turn-round time of shipping been shorter, and had an accurate running inventory of depot stocks been kept so that predetermined shipments could have been adjusted to reflect actual consumption, a greater degree of flexibility in the use of shipping would have been achieved, and the demands of the combat forces could have been met more promptly.56

Troop Build-up

Even before D Day the OVERLORD planners had hopefully considered the possibility of carrying out the continental troop build-up at a greater speed than that laid down in the priority lists. After the operation was launched the prospect of accelerating the flow of troops, first from the United Kingdom and then from the United States, was examined repeatedly.

The theater first sounded out the War Department early in June on the possibility of advancing the shipment of divisions. Through the chief of OPD, General Handy, who was then in the theater, it suggested that under favorable circumstances the build-up might be accelerated, and it asked the War Department for an estimate of its ability to speed up the flow of units after D plus 30. OPD replied that no additional divisions could be shipped in July and noted that it also was too late to preship equipment for any in addition to the four already scheduled for August.57 Three additional divisions could be shipped with their equipment in August, however, and could go directly to the Continent. The War Department also held out the possibility of shipping two divisions in September by advancing one scheduled for movement in October. It emphasized that the big problem in accelerating the flow of divisions was not one of readying them from the standpoint of training, but finding sufficient equipment.58

Meanwhile logistics officers at both the

SHAEF and ETO headquarters also studied the problem, considering both the theater’s ability to receive and equip additional divisions and the prospect of maintaining them on the Continent. For one thing, they noted, the theater would not yet be ready to receive divisions on the Continent directly from the United States in August. To process them through the United Kingdom would create added administrative burdens since a number of divisions were already scheduled to remain in the United Kingdom until D plus 180 because of the inability to support them on the Continent. Furthermore, the reception of additional divisions would entail a drain on existing stocks of supplies, for there was no surplus equipment in the United Kingdom.

As far as receiving the divisions on the Continent was concerned, it was admitted that the rate of build-up might be increased “under favorable conditions”—that is, if supply requirements were materially less than anticipated, or if port capacity and enemy railway demolitions proved more favorable than expected. But the very opposite might well be true, and the maintainable build-up therefore actually less than forecast. Logistical planners felt that the pre-D-Day forecasts were not unduly conservative to begin with, and were in fact based on far lower supply levels than were desirable. They had already considered that the support of the current troop list would be critical in the period from D plus 60 to 90, and had concluded that limitations in both beach and port capacity and in transportation facilities would be a major restriction on the maintenance of a force larger than the one currently planned. Early in June, therefore, supply planners at SHAEF, 1st Army Group, and the Communications

Zone were in general agreement, for the moment at least, that an acceleration of the flow of divisions would be unsound. At any rate, it was rather academic to plan a more rapid build-up on the Continent until the trend of operational developments could be seen more clearly.59

The importance of the whole matter was accentuated by the initially slow tactical progress, with its attendant danger of a strong enemy build-up on a relatively narrow front. The nature of the early fighting led General Bradley to order the first major alteration in the build-up schedule on 15 June, advancing the movement of the 83rd Division by nine days, from 30 June to 21 June. He also ordered that a study be made as to the possibility of similarly advancing the movement of the entire XV Corps (three divisions), across the beaches if necessary.

The army commander was extremely conscious of the necessity to keep the situation in Normandy from “solidifying” in view of the increased resistance building up, and he felt that it might be necessary to bring in additional divisions to enable

the army to continue the attack along the entire front. This view was fully shared by the Supreme Commander, who took steps to advance the shipment of fighting units and ammunition at the expense of service personnel and other types of supplies.60

The administrative implications of such re-phasing were fully appreciated.61 While developments on the Continent could fully justify the acceleration at the moment, there was an inherent danger that the development of an imbalance of combat and service forces might at some future date jeopardize over-all operations. For this reason the advisability of further accentuating the disparity in forces was seriously questioned.62

At General Eisenhower’s request, meanwhile, the whole matter of accelerating the long-range build-up from the United States was again investigated, prompted in part by questions submitted by the British Prime Minister. Mr. Churchill had expressed disappointment, both to the Supreme Commander and to President Roosevelt, over the great preponderance of service troops over combat troops in the forces scheduled for shipment from the United States. He pointed out that the 553,000 men arriving from May through August included only seven divisions, which would indicate a division slice of about 79,000 men. In his opinion the “administrative tails” were too long, and he desired that there be more “fighting divisions” at the expense of service units.63

The protest was hardly warranted, for the shipments in this particular period bore little relationship to the apportionment of combat and service forces planned for the theater—that is, a division slice of 40,000. Service force shipments in these months were abnormally large only because those of earlier months had been disproportionately small in deference to combat units.

In their analysis of the problem both the G-3 and G-4 of SHAEF at first recommended caution in attempting any further acceleration in the build-up of combat forces or reduction in maintenance scales. Some acceleration had already taken place, with the result that the preponderance of combat elements was already greater than planned. As of 27 June, for example, eleven divisions were ashore, as planned, plus the two airborne divisions which had not been withdrawn as scheduled, although the over-all U.S. build-up on the Continent was behind by more than 100,000 men. Only 63,000 of the troops ashore were service troops of the line of communications, the great bulk of the forces consisting of divisions, corps, air force units, and army overheads. The division slice at the time was only 31,000. Some disparity had been planned for in the initial phases, but the continued landing of combat elements more or less on schedule while the build-up as a whole fell in arrears, and the phasing in of some elements (notably the 83rd Division) ahead of schedule had created an even greater disparity. Changes in the movement dates for certain service elements, predicated on the early fall of Cherbourg, had been postponed

when the capture of that port was delayed.64

Several developments to date had admittedly been favorable, resulting in reduced scales of logistical support and therefore indicating the possibility of a more rapid build-up of combat forces. Casualties had been fewer than expected; demolitions had been on a small scale and most rail lines had been captured intact; the small scale of enemy air activity had reduced the need for antiaircraft defenses; and the food situation in Normandy was good.

There were unfavorable factors as well. Bad weather had interfered with shipping and unloading, particularly retarding the discharge of motor transport; the U.S. MULBERRY and many landing craft had been destroyed by the storm; and the capture of Cherbourg had been delayed. Referring to the Prime Minister’s observations on reducing logistic requirements, Maj. Gen. Harold R. Bull noted that it had become “a favorite pastime ... to compare the excessive American tonnage required per divisional slice to that required by the British.” He thought it might be appropriate to point out the difference in the respective tactical missions of the American and British army groups. U.S. forces would have by far the longest lines of communications in their advance westward into Brittany, south to the Loire, and then on the outer edges of the huge wheeling maneuver toward the Seine, which would add immeasurably to their logistical problems.

The G-4, General Crawford, noted that while it was true that administrative requirements had been low thus far as a result of the slow advance, it was by no means certain that tactical progress would continue at such a slow pace, and if a break-through occurred and a rapid exploitation became possible, the maximum number of service troops would be required to develop the lines of communications. He noted further that the build-up was already restricted by the available lift for vehicles and by the over-all supply situation, and that the reduced requirements for antiaircraft defense did not allow any material reduction in air force needs, for these were designed largely for offensive operations.