Chapter 7: German Defense Measures, 1944

OKW Policy in 1944

German strategy for 1944 rested on the realization that decisive offensives could no longer be mounted in the east and that the growing strength of the Western Allies made almost certain a major invasion attempt before the end of the year. The prospective invasion of western Europe presented both the gravest danger to the Reich and the most hopeful opportunity for turning defeat into victory. If the Allies were not stopped at the landings, their attack would carry at once into the heart of Germany; if they were stopped and their beachheads annihilated, it was unlikely that a new attempt could be made for a long time to come, and as many as fifty German divisions might thereby be freed for the struggle against the Soviet Union.1

Recognizing the superiority of the Allied military potential, the Germans knew that their one chance for defeating the invasion was to defeat it quickly. It was therefore vital that the maximum German force be on the spot to fight the decisive battle as soon as the Allies attacked. To stake everything on a battle whose place and timing would be entirely of the enemy’s choosing was to put an all but impossible burden on the defense, demanding of it a mobility it did not have and a sure knowledge of enemy intentions it had no means of acquiring. It was one thing to decide—as Hitler did with the issuance of his Directive No. 51—to prepare the west for the critical battle to come; it was another to find the means to carry out those preparations.

Regardless of how critical the defense of the west was declared, there could be no question of withdrawing forces from the hard-pressed eastern armies to reinforce it. The best that could be hoped for was to hold on to forces already in the various occupied territories outside of Russia and devote to the west the bulk of the new resources in men and equipment that became available in the months remaining before the Allies attacked. After Hitler’s November order, OKW drew up a plan providing in detail for the shift of troops to meet a major Allied invasion of any one of the western theaters of operations. If the invasion hit France—the most likely possibility—OKW planned to move three infantry divisions from Norway and Denmark, one infantry division, a Werfer regiment and a corps headquarters from Italy, and four mobile infantry or Jäger divisions and some minor units from the Balkans.2 Although these

troop shifts would not amount to evacuation of any occupied area, they would mean a considerable concentration of force.

Such concentration was based on the assumption that the Allies would make one main attack. In January OKW began to wonder whether the assumption was justified. All signs still pointed to an attack across the Channel, probably at its narrowest point, but there were also indications that such an attack might be preceded or accompanied by other major thrusts. OKW noticed the “astonishing” emphasis in Allied quarters on preparations for a “second front” and reasoned that these might be designed to conceal another “main blow” that would not strike across the Channel. The “other place” selected might be Portugal or the Balkans, but the choice of the latter had particular plausibility.3 It seemed unlikely that the large Allied forces in the Mediterranean would be committed in the slow and costly attempt to push all the way up the Italian peninsula.4 The Balkan area offered greater strategic prizes and was conveniently at hand.

Whatever area was threatened OKW viewed the twin facts of accumulated Allied power in the Mediterranean and comparative stalemate in Italy as a kind of strategic unbalance which might be solved by another sudden major assault. German jitteriness on this score was not calmed by a report at about this time from agents in England that the ratio of Allied seagoing landing ships to landing craft for Channel use was ten times as great as the Doenitz staff had previously estimated.5 This discovery seemed to confirm the guess that the Allies were planning an expedition outside the Channel. All these fears seemed to be further confirmed by the Allied landings at Anzio on 22 January. The Anzio beachhead, in the German view, had only a slim tactical connection with the main Italian front. General Jodl, Chief of the Armed Forces Operations Staff, considering it to be an independent, self-sustaining operation, argued that it might well be the first of a series of attacks on the periphery of the Continent with the purpose of forcing dispersion of German reserves in preparation for a thrust across the Channel.6 This interpretation drew support from the fact (which the Germans found “surprising”) that the Allies instead of at once pushing inland from the Anzio beaches paused for about a week to consolidate a beachhead, as though the object were not to gain tactical objectives but to attract German forces. Reasoning thus, Jodl told Hitler that they now had to reckon with a peripheral Allied strategy which would probably entail attacks on Portugal, on the west and south coasts of France, or in the Aegean, before the assault on the Kanalküste. With regard to France, it was thought that the most likely Allied peripheral operations would be simultaneous landings on the Mediterranean and Biscay coasts to pinch off the Iberian Peninsula. This threat was taken seriously enough that during February two new infantry divisions then being formed were attached to Nineteenth Army for defense

of the south coast and the 9th SS Panzer Division was released from OB WEST and moved south into the Avignon area as army reserve. One new division went to First Army for defense of the Biscay coast and Spanish border.7

The most important effect of the new appreciation, however, was to unsettle German plans for the defense. If the Allies were going to pursue a policy of many simultaneous or successive assaults, the Germans could not afford to weaken sectors not immediately under attack in order to concentrate on one main invasion. It would, in fact, be very difficult to discover which of many attacks constituted the major threat. Partly for this reason, and partly because the military situation both in the Mediterranean area and in Russia was shifting so rapidly during the early months of 1944 that any plans for the future were subject to almost daily changes, OKW in March canceled its comprehensive defense plans. Instead, theater commanders were advised that troop movements would be ordered in detail only at the time they were needed, presumably after a given Allied attack had developed into a major action. In addition, a new plan was drawn providing for a shift of certain units from the Replacement Army in Germany to any OKW front under heavy attack. OB WEST by this plan might get one corps headquarters, two reinforced panzer grenadier regiments, one reinforced infantry demonstration regiment, Kampfgruppen of three infantry regiments which were cadre for new divisions, a motorized artillery demonstration regiment, five Landesschützen battalions, and one Nebelwerfer demonstration battalion.8 These miscellaneous, partly green units were hardly a substitute for the eight divisions (reinforced) which would have gone to OB WEST under the old plan. Although OKW did not formally abandon the intention of drawing additional reinforcements from occupied areas not under attack, as a practical matter the possibility of such reinforcement had by March become negligible. With the high command admitting the possibility of not one but several landings, strategic uncertainty would evidently delay any possible concentration.9

By March 1944, the German western defense had thus been weakened by a growing confusion as to Allied intentions. This confusion, however, was a relatively small element in the difficulties that multiplied for the Germans after the end of 1943. Not threats but immediate dangers in both the south and east were the principal preoccupations of the German high command. For three months after Hitler issued his order that the west was no longer to be weakened in favor of the Eastern Front, the Germans succeeded generally in holding the manpower dikes despite ominous cracks, and rising tides of Soviet victories. Just before Christmas, 1943, the Russians launched an offensive on the Kiev front which in a few days drove nearly two hundred miles west; in January, Leningrad was relieved by successful attack against the German Army Group North; at the end of the month,

much of the German Eighth Army was encircled near Cherkassy; in February, the Russians attacked the German Sixth Army in the Ukraine in a general offensive to clear the Dnepr bend. The temptation again to corral idle divisions from the west was very great. But only one infantry division was taken from Norway, and it was replaced by a unit which, though not completely formed, was roughly equivalent in combat strength. The west suffered only minor depredations. In February, three reinforced regiments being formed in Germany and earmarked for OKW reserve for the west went east. During the same month 3,000 Russian front soldiers who were suffering from frostbite were exchanged for a like number of troops in the west.10 Signs of the mounting pressure of the Russian war, these borrowings still did not constitute important weakening of the west.

But at the end of January the Anzio landings had opened another small crack. The Germans reacted to the Anzio attack in force, not only because they believed it to be the first of a series of major Allied amphibious assaults, but because they saw the possibility of gaining political prestige by wiping out at least one Allied beachhead. In accordance with plans for meeting a large-scale landing in the southwest, the fully motorized 715th Division was ordered out of France. By 4 February, however, it was seen that this reinforcement was not enough to crush the Anzio beachhead and General Jodl asked Hitler for permission to move in the 9th SS Panzer Division, the only fully combat ready armored division in France. Hitler refused. With an eye on the large Allied reserve forces in North Africa, he feared an attack against the Mediterranean coast of France. He doubted, furthermore, whether the 9th SS Panzer Division, even if eventually returned to France, could make up its losses in Italy, particularly in equipment. OB WEST thus survived that crisis. But the loss of the 715th Division, which because of its unusual mobility had been included with the reserve armored force, was serious enough.11

Much worse was to come. In March, the manpower dikes broke wide open as the Soviet Union launched a new offensive, and at the same time fears increased that Hungary was getting ready to pull out of the war. These circumstances forced temporary abandonment of the principles of Hitler’s Directive No. 51. The bulk of the troops for the occupation of Hungary (carried out in the latter part of the month) were to be furnished by the Commander in Chief Southeast from the Balkans, and by the Replacement Army, but OB WEST had to send the Panzer Lehr Division, a corps headquarters, some aircraft, and a few minor units. The plan was to return all these units as soon as Hungary was firmly in German hands. In fact, the occupation took place rapidly and smoothly and the bulk of the Hungarian Army remained under arms and continued to fight for the Germans. The Panzer Lehr Division thus was actually able to come back to France in May. But two divisions from the Replacement Army and two of the divisions contributed by the Commander in Chief Southeast were shuttled on to the Russian front and a third was saved only by a last-minute appeal to Hitler. The loss indirectly

affected the west in that it further reduced the reserves available to meet the invasion.

With the Russian armies again on the move and threatening to collapse the whole southern wing of the German defense, the danger of invasion in the west for a time dimmed by comparison. The Russians attacked on 4 March. On the 9th Uman fell; the Germans evacuated Kherson and Gayvoron on the 14th. Still the Russian armies suffered no check. Before the end of the month they crossed the Bug, Dnestr, and Pruth Rivers. In Galicia they temporarily encircled the German First Panzer Army. The crisis for the Germans was too desperate to permit consideration of long-range plans. Reinforcements were needed at once and they had to be taken wherever they could be found. On 10 March the 361st Division was ordered out of Denmark, and replaced with a division of much lower combat value. Two weeks later a similar exchange removed the 349th Division from France and brought as a substitute a new weak division, the 331st, from the Replacement Army. At about the same time four divisions under OB WEST (the 326th, 346th, 348th and 19th Luftwaffe Field) were ordered to give up all their assault guns, initially to strengthen Romanian forces and later to be distributed to various divisions along the whole Eastern Front. The big ax fell on 26 March when the whole II SS Panzer Corps with the 9th and 10th SS Panzer Divisions received marching orders to leave France and go to the assistance of the First Panzer Army.12

The departure of the II SS Panzer Corps left OB WEST with only one fully mobile division (the 21st Panzer). The OKW historian has suggested that, had the Allies invaded at that time, Rundstedt could have offered no effective resistance.13 This may be an exaggeration, but it is true that the end of March 1944 marked one of the low points of preparedness in the west and that during the next six weeks, with the Russian front relatively stabilized, the west did much to recoup its losses. By the middle of May four panzer divisions were ready for combat (despite deficiencies of equipment) and four more were being built up. Toward the end of the month Panzer Lehr Division returned from Hungary and the 1st SS Panzer Division from the Eastern Front was attached to OB WEST for rebuilding. At the same time the XLVII Panzer Corps under General der Panzertruppen Hans Freiherr von Funck, one of the oldest and most experienced armored commanders in the German Army, was brought from the east to serve under Rundstedt.

Actually the recuperative powers of the west under the severe and continuing strain of supplying transfusions to the east were remarkable. Between November 1943 and June 1944, the total of combat divisions under Rundstedt’s command increased from forty-six to fifty-eight. The increase was accounted for in part by the transfer of fought-out units from Russia but in larger part by the formation of new units. In the fall of 1942 the German Army, already sore-pressed for manpower, adopted the policy of combining training with occupation duties. The old combined recruiting and training units were split, and the recruit henceforth after induction into a recruiting

unit near his home was sent to an affiliated training unit in the field. In 1943 about two-thirds of these training units were located in France, the Low Countries, Denmark, Poland, Lithuania, the Soviet Union, and northern Italy. The infantry and panzer units were organized into reserve divisions of which twenty-six (including four panzer) were formed during 1942 and 1943. Half of these were stationed in the OB WEST sector. Though they remained under the commander of the Replacement Army and theoretically retained their primary function of training replacements, in reality they came to be regarded as low-grade field divisions. Their time was increasingly devoted to garrison duty and on occasion to fighting Resistance forces. In order to carry out these duties, they received administrative attachments from the regular field army. As their operational responsibilities expanded and they began to occupy a permanent place on OB WEST’s order of battle, it became impossible for them to give up personnel for filler replacements to regular units. In short they became themselves an integral part of the field army. In recognition of this fact, most of them were eventually redesignated as infantry or armored divisions. Six of OB WEST’s reserve divisions, including all three reserve panzer divisions, had thus been upgraded before the invasion. Five of the remaining seven were similarly converted in the summer of 1944; the other two were disbanded.14

Besides converting reserve divisions, the Commander in Chief West enlarged his army by rehabilitating German units from the east as already noted, and by activating new divisions out of miscellaneous personnel drawn in part from his own resources and in part from the Replacement Army. The effect of all this on the organization and character of the west army must be described in some detail, but in summary it may be said that the steady drain of the Eastern Front left to Rundstedt on the eve of his great battle two kinds of units: old divisions which had lost much of their best personnel and equipment, and new divisions, some of excellent combat value, some only partially equipped and partially trained. The majority of the new divisions were formed according to streamlined tables of organization designed generally to use the fewest possible men to produce the maximum fire power.

Organization for Combat

Between 1939 and 1943 the German standard infantry division contained three regiments with a total of nine rifle battalions. Each of the infantry regiments had, besides its twelve rifle and heavy weapons companies, a 13th (infantry howitzer) and 14th (antitank) company. The division had also an antitank and a reconnaissance battalion. Organic artillery consisted of one regiment of one medium (150-mm. howitzer) and three light (105-mm. howitzer or gun) battalions with a total armament of forty-eight pieces. German division artillery was thus roughly equal to that of a U.S. division. Chiefly because of the antitank and reconnaissance units, on the other hand, the division with 17,00 men was substantially larger than its U.S. counterpart.

It was also substantially larger than could be supported by the dwindling supply of manpower after four years of war. In October 1943 the division was drastically overhauled to reduce its size while maintaining its fire power. Organization charts of the new-style division (with 13,656 men) comprising three regiments of two battalions each had only just been published when further slashes were ordered. The problem (set in January 1944 by Hitler) was to trim the personnel to something like 11,000 without affecting the combat strength. Army planners rejected this sleight of hand as impossible and contented themselves with a further cut from 13,656 to 12,769. Reductions were made chiefly in supply and overhead, and the proportion of combat to service troops was thereby raised to 75-80 percent. The result was the so-called 1944-type infantry division.15

The reduction from nine infantry battalions to six was partly alleviated by the substitution of a Füsilier battalion for the old reconnaissance unit. The Füsilier battalion, still charged with reconnaissance duties, was organized like a rifle battalion except that one company was equipped with bicycles and the unit had slightly more horse-drawn vehicles and some motor transport. In practice the Füsilier battalion came to be reckoned as a seventh rifle battalion.

Besides lopping off three battalions, the new division pruned out the rifle squad and company while at the same time increasing the proportion of automatic weapons.16 The basic unit, the rifle company, was cut to 140 enlisted men and 2 officers, as compared with the U.S. company of 187 enlisted men and 6 officers. Rifle strength in the German division was about 1,200 less than in the American but the total division fire power was superior. About equal in artillery, the German division enjoyed a slight preponderance in infantry howitzers, and a heavy superiority in automatic weapons.17

The 1944 infantry division was set up as the basic type for new divisions as well as for the reorganization of certain old formations, as for instance, the Luftwaffe field divisions.18 The division which included the bulk of Rundstedt’s infantry, however, the static (bodenständige) division, was exempted from reorganization unless specifically so ordered. The static divisions were formed at the request of Rundstedt in 1942 in order that he would have a nucleus of divisions not subject to transfer to the east. Though triangular with nine rifle battalions, they were substantially weaker than the normal old-type infantry division. They lacked the reconnaissance battalion and had only three battalions of artillery.19

Although the static divisions were expressly designed as permanent garrison troops for the west, they were by no means safe from the periodic troop collections

for the east. Actually, by the end of 1943, most of the divisions had lost their third regiments. Attempts in 1943 and early 1944 to rehabilitate the units and fill their ranks chiefly with Ost battalions resulted in virtual abandonment of tables of organization in favor of improvisation that reflected both the particular nature of the coastal assignments and the vicissitudes of the long struggle for manpower and equipment. In total strength and number and variety of combat units the static divisions bore little resemblance to one another. While the 716th Division, for instance, had six battalions and only one regimental headquarters under its control on D Day,20 the 709th, occupying two and a half times as long a coast line, had eleven battalions under three regiments.

Even after the 1944-type division had been standardized, experimentation continued. Certain divisions (notably the 77th and 91st in Seventh Army area) organized their six rifle battalions in two regiments. They lacked the füsilier battalion and had three instead of four artillery battalions.21 In the case of the 77th Division this organic lack was partly made up by the attachment of an Ost battery and a Volga-Tatar rifle battalion. The 91st Division went into combat with an attached parachute regiment. The two-regiment infantry division therefore did not operate in T/O form in the invasion area, and for the German Army as a whole it may be regarded as experimental and eccentric, designed further to conserve manpower but not accepted as a generally satisfactory solution.

The best infantry units in the 1944 German Army were the parachute divisions, administratively under the Luftwaffe but tactically always subordinated to Army command. Until the fall of 1943 German airborne forces comprised only one corps with two parachute divisions. At that time Goering proposed and Hitler approved a program intended to produce by the end of 1944 two parachute armies with a total strength of about 100,000 men. They were to be an elite arm and were put on an equal status with the SS units in recruiting, armament, equipment, and training.22

Of the new parachute units created during the early months of 1944, OB WEST received the 3rd and 5th Divisions and the 6th Parachute Regiment (from the 2nd Parachute Division).23 Only the separate regiment and the 3rd Division were encountered during the fighting described in this volume. Both were first-rate fighting units.

The 3rd Parachute Division comprised three regiments of three battalions each and in addition had in each regiment a 13th (mortar) company, 14th (antitank) company, and 15th (engineer) company. The mortar company in the 6th Parachute Regiment actually contained the nine heavy (120-mm.) mortars which the tables of organization called for, but in the 3rd Parachute Division weaponing

was miscellaneous, including 100-mm. mortars and 105-mm. Nebelwerfer.24 The parachute division had only one battalion of light artillery (twelve 70-mm. howitzers). An order of 12 May 1944 to substitute an artillery regiment with two light battalions and one medium was not carried out before the division entered combat. The same order called for formation of a heavy mortar battalion (with thirty-six 120-mm. mortars) but this, too, was apparently not complied with. During April and May the division was able to constitute its antiaircraft battalion which had, besides light antiaircraft artillery, twelve 88-mm. guns. The total ration strength of the division as of 22 May was 17,420. The strength of the 6th Parachute Regiment with fifteen companies was 3,457. Both were thus considerably larger than the normal corresponding infantry units. They were superior not only in numbers but in quality. Entirely formed from volunteers, they were composed principally of young men whose fighting morale was excellent.25

The average age of the enlisted men of the 6th Parachute Regiment was 17½. The parachute units were also much better armed than corresponding army units. The rifle companies of the 6th Parachute Regiment had twice as many light machine guns as the infantry division rifle companies. The heavy weapons companies with twelve heavy machine guns and six medium mortars each were also superior in fire power to army units. Chief weakness of the parachute troops was one they shared with the rest of Rundstedt’s army—their lack of motor transport. The 6th Parachute Regiment, for instance, had only seventy trucks and these comprised fifty different models.26

Theoretically, about on a par with the parachute divisions were the panzer grenadier divisions which, by American standards, were infantry divisions with organic tank battalions, some armored personnel carriers, and some self-propelled artillery. The only such division in the west during the invasion period was the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division (Goetz von Berlichingen). Like all SS divisions it was substantially stronger than the corresponding army division. On the other hand, like so many west divisions, its combat strength in fact was much less than it appeared on paper. Its six rifle battalions were organized in two regiments which were supposed to be motorized; one battalion was supposed to be armored. In reality four of the battalions had improvised motor transport (partly Italian), two being equipped with bicycles. The “tank” battalion had thirty-seven assault guns, five less than authorized. The division had no tanks. Intended

personnel strength was 18,354, of which on 1 June the division actually mustered 17,321. The antitank battalion, supposed to consist of three companies of self-propelled guns, had actually only one company, equipped with nine 75-mm. and three 76.2-mm. guns. The division had a full armored reconnaissance battalion of six companies, and an antiaircraft battalion. The latter contained twelve towed 88-mm. guns as well as guns of smaller calibers, but lacked almost a fifth of its personnel.27

To meet the invasion in June, OB WEST had six army and three SS panzer divisions. Their strength and organization varied so widely that it is impossible to talk of a type. Personnel strength of the army divisions ranged from 12,768 (9th Panzer) to 16,466 (2nd Panzer).28 The SS divisions, which had six instead of four infantry battalions, varied from 17,590 (9th SS Panzer)29 to 21,386 (1st SS Panzer). All the panzer divisions were thus much larger than their American counterparts, the 1st SS being more than twice as large. On the other hand they all had fewer tanks. Here again individual variations were enormous. The type organizational tables for both army and SS divisions called for a tank regiment with one battalion of Mark IV and one battalion of Mark V tanks. Each battalion was supposed to have four companies each with twenty-two tanks. The fact was quite different. Even the 2nd Panzer Division, the best prepared of the armored divisions on D Day, had less than its authorized number of the heavier Mark V’s.30 Each of the divisions had a separate and slightly different organization which in no case conformed to the type. The 1st SS Panzer Division, for instance, was supposed to have 45 assault guns, 21 Mark III, 101 Mark IV, and 81 Mark V tanks. It had in fact the full complement of assault guns but only 88 tanks in all, including 50 IV’s and 38 V’s. The table of organization for the 2nd SS Panzer Division, on the other hand, called for 75 assault guns of which 33 were on hand on 1 June; 7 Mark III tanks, none on hand; 57 Mark IV tanks, 44 on hand; and 99 Mark V’s, 25 on hand.31

The army panzer divisions included, in addition to the two regiments (four battalions) of infantry and one tank regiment, a self-propelled antitank battalion (armed more often with assault guns), an armored reconnaissance battalion, a towed antiaircraft battalion and an artillery regiment with one light self-propelled battalion, one light towed battalion, and one medium towed battalion. SS divisions had an additional towed light battalion.

The miscellaneous tank armament of the panzer divisions was typical of the weaponing of nearly all units in the west and reflected the long drain on the German

war economy of the Russian war and the increasing production difficulties imposed by the accelerating Allied air offensive. As long as the Russian front was the main theater of war and the west was not immediately threatened, it was natural to ship the bulk of the best materiel to the east and arm the west as well as possible with what was left. The policy of equipping west divisions primarily with captured materiel was laid down in December 1941 when ten divisions were ordered so equipped.32 The east continued to enjoy priority on new equipment until the end of 1943, and although German-made tanks and assault guns were shipped to OB WEST during that time the deliveries were often more than outweighed by the transfer of armored units. First-class armored equipment remained a comparative rarity in divisions assigned to OB WEST until 1944. At the end of October 1943, for instance, there were in the west 703 tanks, assault guns, and self-propelled 88-mm. antitank guns (called “Hornets”). At the end of December the number had risen only to 823, the increase being largely in the lighter Mark IV tank. All the Hornets and Tiger (Mark VI) tanks had been shipped out to the Russian front, and the stock of assault guns was considerably decreased. The total of 823, moreover, compared to a planned build-up of 1,226.33 The new year brought a change. January showed only a slight increase, but thereafter the deliveries to the west were speeded up. Although most new Tiger tanks continued to go to the east, deliveries to OB WEST of the powerful Panther (Mark V) tank were notably increased. At the end of April OB WEST had 1,608 German-made tanks and assault guns of which 674 were Mark IV tanks and 514 Mark V’s. The planned total for the end of May was 1,994.34

Against the background of disintegrating German war economy, the tank buildup in the west was a notable achievement that strikingly revealed the importance assigned to the forthcoming struggle with the Western Allies. Exponents of the theories of Blitzkrieg, like Generaloberst Heinz Guderian, the Inspector General of Panzer Troops, believed that without a large armored striking force Germany could not hope to return to offensive operations essential for ultimate victory. In late 1943, therefore, Guderian proposed and Hitler approved a scheme to form a ten-division strategic armored reserve while at the same time trying to bring all armored divisions up to strength in equipment. The need, in short, was for new tanks in large numbers. But the combined pressure of the Allied air offensive and Russian ground attack was rapidly creating an economic quagmire in which the harder the enemy struggled the deeper he sank. Russian armies were destroying existing tanks while Allied bombers were making it increasingly difficult to produce new ones. The Germans tried to find an answer in diverting additional men, materials, and factory space into the manufacture of tanks. One result was to curtail the production of prime movers and parts. But without prime movers in adequate numbers the German armies in

Russia were unable to withdraw their heavy guns or retrieve tanks that were damaged or out of fuel. Between October and December 1943, 979 Mark III and IV tanks and 444 assault guns were lost, in large part because they had to be abandoned in retreat. Similarly between July and December 2,235 artillery pieces and 1,692 antitank guns were captured or destroyed. General Guderian at last pointed out that there was little sense in producing more tanks and guns if they were to be thus recklessly sacrificed.

A still more important by-product of concentrating on tank manufacture at the expense of a balanced production program was the increasingly serious lack of spare parts. In June 1943 the Germans had 2,569 operational tanks with 463 in process of repair. In February 1944, only 1,519 tanks remained operational while 1,534 were under repair. During February, moreover, only 145 damaged tanks were actually returned to the front. On the first of the month, Guderian estimated that the tanks and assault guns awaiting repair equaled about nine months’ new production. At the end of March, the situation had not improved; the number of operational tanks was still decreasing despite accelerated deliveries of new machines.

Although the German Army in the west on the eve of its great test was considerably weaker than planned in equipment, quality, and numbers, it was nevertheless a force strong enough to hope for victory in a battle in which Allied materiel superiority would be partly counteracted by the natural advantages of a coast line defense.

Under Rundstedt’s command on 1 June 1944 were 58 combat divisions of which 33 were either static or reserve, suitable only for limited defense employment. There were 24 divisions classified as fit for duty in the east by reason of their relative mobility and high-grade personnel. They included 13 infantry divisions, 2 parachute divisions, 5 army panzer divisions, and 4 SS panzer and panzer grenadier divisions. One panzer division (the 21st), being still equipped in part with captured materiel, was not considered suitable for service in Russia, although in other respects it was ready for offensive use, and in fact had exceptional strength in heavy weapons.35

All the infantry divisions were committed on or directly behind the coast under the command of one of the four armies or the German Armed Forces Commander Netherlands.36 The four armies were the First holding the Atlantic coast of France, the Seventh occupying Brittany and most of Normandy, the Fifteenth along the Kanalküste, and the Nineteenth defending the French Mediterranean coast. The Seventh Army, which was to meet the actual invasion, had fourteen infantry (including static) divisions under the control of four corps.37

Command and Tactics

It may be that the most serious weakness of the German defense in the west

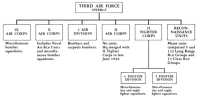

was not the shortage of men and materiel but the lack of a unified command. While Rundstedt was charged with the entire responsibility for the defense of France and the Low Countries, his powers were far from commensurate with that responsibility. He had, in the first place, no command over air and naval units. The four air corps that comprised the fighter and bomber aircraft stationed in the west were under command of the Third Air Force (Generalfeldmarschall Hugo Sperrle), which in turn was directly subordinate to OKL. Similarly Navy Group West, which under Admiral Theodor Krancke commanded the destroyers, torpedo boats, and smaller naval vessels based in the ports within Rundstedt’s jurisdiction, was responsible directly to OKM. Rundstedt could issue no orders to either Sperrle or Krancke; he could only request their cooperation. (Charts 2, 3, 4)

Air and naval forces were too small to have decisive effect on the battle. From Rundstedt’s point of view the more important limitation of his power was the fragmentation of the command over the ground forces. Some of this fragmentation was normal and universal in the German military establishment. The Third Air Force had, for instance, besides command of the flying units, administrative control over parachute troops and the antiaircraft units that were under the III Flak Corps.38 Navy Group West controlled through regional commanders not only ships and shore installations but most of the coastal artillery, although command of the latter was mixed. The Navy had complete jurisdiction before operations on land had begun. Afterward, firing on sea targets remained a naval responsibility, but at the moment of enemy landing, in most cases, command of the batteries in the beachhead area was to pass to the Army. Virtually the whole burden of tying in the important naval batteries to the coastal defense was thus shifted to the initiative of local commanders.

A similar division of command affected the employment of the security troops which as instruments of the occupation were normally under the two military governors (Militärbefehlshaber), France and Northern France (including Belgium). The military governors were directly subordinated to OKH, but for purposes of repelling invasion their security troops might be tactically under OB WEST. In preparation against invasion, the Commander in Chief West could only direct that the military governors cooperate with the army groups in matters affecting the latter’s authority and undertake to settle any differences that might arise between them. Even this control was limited. Employment of security troops could only be ordered by the Commander in Chief West “in matters outside the scope of security.”39

During 1944 OB WEST’s authority was abridged in special ways. In November 1943, it will be recalled, Field Marshal Rommel had taken command of the Army Group for Special Employment, which was charged at first with inspection

Chart 2: German Chain of Command in the West, May 1944

Chart 3: Luftwaffe Command in the West

Chart 4: German Naval Command in the West

of the western defenses and the preparation of plans for counterattack against the main Allied landings wherever these might take place. Ultimately the Rommel headquarters was to conduct the main battle against the invading forces. About the middle of December, Rommel, having completed the first of his tasks, the inspection of the coastal defenses of Denmark, arrived in France and began a survey of the Fifteenth Army sector. Both he and Rundstedt recognized at once that it was neither logical nor practical for the Special Army Group to remain outside the theater chain of command.40 Its independence could only be a source of friction and inefficiency. On 30 December Rundstedt recommended that it be subordinated to OB WEST as Army Group B with command of the Seventh and Fifteenth Armies and of the German Armed Forces of the Netherlands. Whether the initial suggestion for this change came first from Rommel or from Rundstedt, it was clearly in the beginning agreeable to both.41 Since the main Allied invasion was likely to strike somewhere along the Channel coast, it made sense to put Rommel in immediate command there in order to familiarize him with his task and allow him to take such steps as he found necessary to strengthen the defense. Hitler approved but warned OB WEST that the Rommel headquarters was still to be considered available for commitment elsewhere.42 Rundstedt accepted the condition, and the reconstitution of Army Group B was ordered to take effect on 15 January. Rommel’s subordination to OKW was at this time canceled.43

His position, however, remained anomalous: whereas he had less than full command over the armies attached to him, he enjoyed an influence over the whole defense of the west which was in some measure commensurate with Rundstedt’s. His orders provided that he was to be solely responsible for the conduct of operations (Kampfführung), but that in matters not directly affecting this tactical command OB WEST would continue to deal directly with the armies. Thus on questions of defense, training, organization and equipment, supply, artillery matters, communications, and engineer problems, the command channel might bypass the new army group.44 Rommel continued to be the coastal inspector for the whole of the west, and although his reports henceforth were forwarded through OB WEST his ability to influence coastal defense policies and practices did much to blur his subordination to Rundstedt. Moreover the binding of the Rommel staff to a geographical sector

was only tentative; the headquarters was thought of still as a reserve command and as such the recommendations of its commander carried special if informal weight.45 Finally, and most importantly, Rommel in common with all German field marshals enjoyed at all times the right of appeal directly to Hitler.46 That privilege was especially important for the west because of the personalities involved. The evidence indicates that Rommel had an energy and strength of conviction that often enabled him to secure Hitler’s backing, whereas Rundstedt, who was disposed whenever possible to compromise and allow arguments to go by default, seems to have relaxed command prerogatives that undoubtedly remained formally his. It is possible, of course, that he too came under Rommel’s influence and failed to press acceptance of his own ideas because he was content to allow Rommel to assume the main burden of responsibility. In any case the clear fact is that after January 1944 Rommel was the dominant personality in the west with an influence disproportionate to his formal command authority.

Rommel’s position, however, was not unchallenged. In November 1943 Rundstedt, thinking in terms of a large-scale counterattack against the main Allied landings, created a special staff to control armored units in that attack. The staff, designated Panzer Group West, was headed by General der Panzertruppen Leo Freiherr Geyr von Schweppenburg, and was directed to take over at once the formation and training of all armored units in the west and to advise the Commander in Chief West in the employment of armor. Geyr was ordered to cooperate with and respect the wishes of army group commanders.47 Actually, however, Geyr’s ideas on the proper employment of armor were so completely at variance with Rommel’s that cooperation was impossible.

In March 1944, at a meeting of the senior commanders in the west with Hitler, Rommel asked for an extension of his own authority that to all intents would have eliminated Geyr and Rundstedt as well from effective command of the defense forces. Specifically he requested that all armored and motorized units and all GHQ artillery in the west be put directly under his command and that he also be given some control over the First and Nineteenth Armies. The latter two armies, defending the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts of France respectively, were at this time still subordinated immediately to OB WEST. In one sense, Rommel’s request logically arose from his mission. Assigned responsibility for countering the major Allied invasion attempt, he required control over all the forces that might be used in the defense. It was plausible furthermore that such control should be turned over to him before the battle so that he could properly prepare and dispose the troops to fight the kind of battle he would order. Making a strong bid to unify defense policies, he asked that the Humpty-Dumpty command in the west be put together again under him. Although the method of repair naturally did not please Rundstedt, his objections

were unheeded at the March meeting and Hitler approved the expansion of Rommel’s command. Only after a study by the operations staff of OKW had supported Rundstedt’s later written protest did Hitler reverse himself. Even then the reversal was not complete. Three panzer divisions (the 2nd, 21st, and 116th) were assigned to Rommel as Army Group B reserves, over which he was to have full tactical control while Geyr remained responsible for their training and organization.48 The patchwork solution solved nothing.

At the same time four other panzer-type divisions in OB WEST’s sector (the 1st SS Panzer, 12th SS Panzer, 17th SS Panzer Grenadier, and Panzer Lehr) were set aside as a central mobile reserve under the direct command of OKW. The two decisions smacked of a compromise tending to preserve something of both Rommel’s and Rundstedt’s tactical ideas.49 The main effect, however, was to deprive the Commander in Chief West of the means to influence the battle directly without transferring those means to Rommel. Thus, even such inclusive authority as was possible in the German military establishment was scrupulously withheld from both high commanders in the west.

The final command change before the invasion was made in May when Rundstedt ordered the formation of a second army group headquarters to take command of the First and Nineteenth Armies. Army Group G, formed under Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz, took over, besides the two armies, the remaining three panzer divisions in France (the 9th, 11th, and 2nd SS).50 The reorganization provided a counterbalance for Rommel and somewhat simplified the command channels. It probably also expressed final recognition of the impracticability of the reserve high command concept.

With the establishment of Blaskowitz’s headquarters, Rundstedt undertook to define his own position. He outlined for himself what amounted to an over-all ground command in his theater, subject to the restrictions already discussed. He announced his intention of granting his army group commanders the maximum freedom of action in their own sectors. He would intervene only when he fundamentally disagreed with their policies or when decisions had to be made affecting the theater as a whole. He promised to confine his directives to passing on Hitler’s orders and to specifying policies that ought to be uniformly carried out by all commands.51

In fact, during the critical preparatory months of 1944, general directives were few either from Rundstedt or Hitler. Hitler, far away at his headquarters in

East Prussia, was so preoccupied with the Russian war that he did not even visit the west until after the invasion. Furthermore he seems not to have had any clear and consistent view of tactics himself, and his interventions in the western scene resulted more often in decisions of detail than in definitions of policy. The failure of Hitler to provide consistent guidance together with the vague demarcation of authority between Rommel and Rundstedt left the west with a vacillating leadership. Defense preparations in 1944 were increasingly scarred by compromise as the Commander in Chief West and the commander of Army Group B made detailed decisions in accordance with divergent aims.

The perspective from which Rommel viewed his task derived in part from his experience with desert warfare in North Africa and in part from the circumstances of his new assignment. It is important to bear in mind that Rommel came to the west only at the point when the battle was about to be fought there, and that he was assigned responsibility specifically for the conduct of that battle. He had not endured the long waiting period with its periodic alarms. He had not spent months making plans, calculating actual but shifting deficiencies against ideal needs, outlining defense systems and struggling to find the means to carry them out. The theoretical approach to tactics—the drafting of the abstractly best plan first, the search for resources second—was ruled out by the nature of his mission as well as by the limited time at his disposal. He was appointed coastal inspector and told to assess defensive capacities and make his plans accordingly. Whatever he chose to do had to be completed in three or four months. He was bound therefore to start by examining his limitations.

The experience in North Africa had convinced Rommel of the folly of trying to use massed armor as long as the enemy enjoyed air superiority. In Africa Rommel commanded some of the best trained and equipped troops that Germany produced. In France he was to command an army that was already crippled in part by inadequate training, inferior human material, and lack of mobility. Furthermore, there was still less hope in 1944 than in 1942 that the Luftwaffe could challenge the supremacy of the Allies in the air. To Rommel that meant that mobile operations were impossible in fact however desirable they might be in theory. If the German Army could not hope to maneuver on anything like terms of equality with the Allies, its only chance for a defensive success was to fight from the strongest possible natural positions. The pillboxes, entrenchments, wire, and mines of the Atlantic Wall and the waters of the Channel, in short, seemed to Rommel to offer not only the best but the only means to offset Allied superiority in mass and mobility.52

Rommel therefore was led to place an exclusive dependence on fortifications that Rundstedt never advocated and that even Hitler had not contemplated in his directive of November. The battle for the west, Rommel believed, would be decided at the water’s edge, and the decision would come literally within the first forty-eight hours of the Allied landings.53 In accord with that diagnosis, his first aim was to create a defensive belt around

the entire coast with special concentration on the Fifteenth Army sector) extending five or six kilometers inland. Within this belt all infantry, artillery, headquarters staffs, and reserves up to division level were to be located in a series of resistance nests.54 Between the resistance nests mines and obstacles were to be laid so thickly as to prevent enemy penetration. Because of limited time, labor, and materials, Rommel concentrated on many simple, field-type defenses rather than on a few complex fortifications. He stressed in particular the laying of mines. He introduced further, a defense device new to the Atlantic Wall: underwater obstacles designed to wreck landing craft.55 In Normandy, hedgehogs and tetrahedra located inland as tank obstacles were moved to the beaches suitable for enemy landings. They were supplemented by Belgian Gates and stakes slanting seaward. The intention was to cover every possible landing beach between high- and low-water marks with obstacles staggered to leave no free channel for even a flat-bottomed boat to reach shore. Obstacles as far as possible were to be mined. As it was considered most likely that the Allies would land at flood tide to reduce the amount of open beach to be crossed under fire, laying of the obstacles began at the high-water line and was extended in belts seaward as materials and labor became available.56

To complete his hedgehog fortress, Rommel undertook to stake all fields suitable for glider landings behind the coastal zone. The stakes were to be placed close enough together so that gliders could not come down between them. They, too, were to be mined. The German estimate was that Allied airborne troops would be used in diversionary and subsidiary operations, for which Brittany and Normandy were considered the most likely target areas. Rommel therefore concentrated the erection of antiairlanding obstacles in these areas.57

The general scheme of obstacle defense of the Continent was further to be extended by mine fields in the Channel. Sixteen fields, each about five miles long, were put down in the Channel between Boulogne and Cherbourg from August 1943 to January 1944. These were to be kept renewed as far as possible, but it was not believed that they would have much effect on Allied shipping. They were therefore to be supplemented by hasty mine fields laid down by all available vessels immediately before the invasion was expected. These fields would be planted without keeping open any marked lanes for German vessels. From Zeebrugge to Granville thirty-six mine fields were planned. It was also planned, when invasion seemed imminent, to sow mines from the air in British harbors. Finally along the French coast shallow-water mines were to be laid and a special seventy-kilogram concrete mine was developed for the purpose.58 In all these

Anti-landing obstacles under construction on a French beach

Belgian Gate [Element C]

ways Rommel sought to make the expected invasion physically impossible. The Allied force entangled in the spider web of obstacles would be given the paralyzing sting by the German Army waiting at the water’s edge.

Rommel’s construction and mine-laying program called for a very large expenditure of labor, and labor was scarce. It has already been pointed out that Organization Todt was employed chiefly in the major port fortress areas, on V-weapon sites, and, in the spring of 1944, on railroad maintenance. In the apportionment of the remaining labor supply among the armies, Fifteenth Army continued to receive priority. Seventh Army thus had special difficulty in completing its defense works. The LXXXIV Corps was assigned three engineer battalions in January, two for fortress building and one for mine laying. In addition, 2,850 men of the former French Labor Service were set to work on a secondary defense line immediately behind the belt of coastal resistance points. Pleas for more construction hands were answered by attachment of two Ost battalions.59

The only other available labor source was the combat troops. Increasingly during 1944 infantrymen were employed in work details on the Atlantic Wall with consequent serious reduction of combat training. The reserve battalion of the 709th Division, for instance, devoted three days a week exclusively to labor duty. The time for training in the rest of the week was further reduced by transport and guard details. During the first two weeks in May the battalion was employed full time on the coastal defense in the Barfleur sector.60 The 709th was an old division, but its personnel constantly shifted. The lack of continuous adequate training meant that the total combat fitness of the division steadily deteriorated through the accretion of untrained recruits.

Still worse was the effect on the new and reorganized divisions that represented a large proportion of the German striking force in the west. In Seventh Army all but one of the nonstatic infantry divisions were organized during 1944. New divisions accounted for six of the fourteen divisions under the army’s command. All of these units were burdened with construction duties. In February Rommel ordered that infantry be used to lay mines and obstacles. On 25 May Seventh Army reported to OKH that all its units were engaged in construction projects and that consequently the necessary training was not being carried out.61

The only units specially exempted from work on the fortifications were the two parachute divisions. The 3rd Parachute Division was brought into Brittany in March and stationed east of Brest. Its mission was to complete its organization and at the same time train for defense against airborne attack. The 5th Parachute Division moved into the Rennes area between 5 and 14 May with a similar mission. Both divisions in May were put under command of the II Parachute Corps which, though subordinated tactically to Seventh Army, was administratively and for training purposes under the Third Air Force. Since the Luftwaffe was thus responsible for parachute unit

training and, on the other hand, was not responsible to army commands anywhere in the hierarchy, Reich Marshal Goering ordered that the parachute divisions not be used for construction work except in providing local security for themselves against airborne attack.62 The 5th Parachute Division had scarcely more than begun to fill out its ranks when invasion struck; but the 3rd proved one of the best prepared of the new units in Seventh Army.

The general stinting of training under the circumstances seems to have been inevitable and apparently did not arouse any serious protests at the time.63 Where Rommel’s program met really effective opposition was in his efforts to concentrate reserves within the coastal zone. If it was true that the Germans had to fight on a fortified line, if they could not hope to maneuver freely, and if the crisis of the battle against the invaders would come within the first forty-eight hours, then it followed that all forces would be wasted which were not near enough to the coast to be committed at once against the first landings. This deduction was the final extension of the doctrine of static defense implicit in the original decision to build the Atlantic Wall. At least one high German commander had predicted the development and had warned against it in caustic tones. Sodenstern, commanding the Nineteenth Army, wrote privately in the summer of 1943 of his fear that German generalship would exhaust itself in the construction of huge masses of concrete. “As no man in his senses,” he argued, “would put his head on an anvil over which the smith’s hammer is swung, so no general should mass his troops at the point where the enemy is certain to bring the first powerful blow of his superior materiel.”64 Rommel’s answer, in all likelihood, would have been, first, that there was no practical alternative, second, that the first Allied blow at the point of the landings would not be the most powerful but the weakest since only a small portion of Allied fire power could then be effective, and, third, that the German general in massing his troops in fortified positions was at least giving their heads some protection against the smith’s hammer.

The difference of opinion was essentially a difference in judgment of what was possible. Rommel’s chief of staff has testified that Rommel would have preferred a battle of maneuver had he seen any chance of its succeeding.65 Rundstedt, like Sodenstern, was clearly more optimistic, perhaps because he had not had firsthand experience with the air power of the Western Allies. In any case, he did not accept Rommel’s thesis and the influence of OB WEST was exerted spasmodically in resisting Rommel’s efforts to shift the weight of the army forward to the coast, and in trying instead to free as many units as possible from bondage to the rigid defense system.

In practice any plan to introduce flexibility into the defense depended primarily on whether units could be made

mobile and whether they could be organized and equipped to support themselves in combat. Through the early months of 1944 Rundstedt struggled to strengthen and provide some transport for the coastal divisions. In the Seventh Army area he succeeded in forming mobile Kampfgruppen (of reinforced regiments) from four of the infantry divisions (the 265th, 266th, 275th, and 353rd) defending the Brittany coast. In case of a major invasion of Normandy, Seventh Army had plans to move these Kampfgruppen into the combat zone. In the Cotentin, the 243rd Division was converted from a static into a nominal attack infantry division.66 It was reorganized according to the 1944 type with six infantry battalions. Four battalions were to be equipped with bicycles. The artillery regiment, supply troops, and antitank battalion were to be motorized. Reorganization took place in late 1943, but the motorization planned to begin in May 1944 could be carried out only in very limited degree.67

It should be observed in this connection that German notions of mobility in the west in 1944 hardly corresponded to American concepts of a motorized army. A mobile infantry unit in general was one equipped with bicycles, with horse-drawn artillery, and a modicum of horse and motor transport for supply purposes. It was called mobile more because of its ability to maintain itself in the field than because of its ability to move rapidly from one place to another.

For the most part the Germans lacked resources even to provide that limited mobility for the west army. Rundstedt’s efforts to restore mobility to his static divisions on the whole failed. A beginning, for instance, was made to upgrade the 709th Division, but the vehicles allotted in March had to be withdrawn in May when, as a result of the Allies’ successful rail bombing attacks, Seventh Army began to scrape together everything on wheels to form corps transport companies.68

Rundstedt’s efforts to put wheels under his army were at least partly offset by Rommel’s concurrent labors to dig in every available soldier and gun along the coast line. After an inspection trip in the LXXXIV Corps sector in February, Rommel concluded that reserves were held in too great strength too far from the coast. In particular, he felt that the 352nd Division, located near St. Lô, and the 243rd Division, near la Haye du Puits, should be regrouped so that they could be committed in the first hours after an enemy landing. Seventh Army therefore ordered that the divisional reserves of the 709th and 716th Divisions (the 795th Georgian Battalion and 642nd Ost Battalion respectively) should be committed at the coast, that the 243rd and 352nd Divisions should move slightly northward,69 and that the 352nd Artillery Regiment of the latter division should be emplaced in the coastal zone under the control of the

German mobile infantry equipped with bicycles

German mobile infantry equipped with animal transport (below).

Captured German Armor. U.S. troops inspecting Panther (Mark V) tank

Captured German Armor. U.S. troops inspecting 75-mm. assault gun mounted on Mark IV chassis.

716th Division.70 Similar reshuffling in Brittany put the artillery of the 275th and 353rd Divisions into static defense positions.71 The shift forward of the 352nd Division meant in effect that it was no longer in reserve. On 14 March Seventh Army therefore proposed that the division actually take over responsibility for the left half of the 716th Division sector. On OB WEST’s approval, this change was accomplished by 19 March. With the doubling of the troops on the coast, the former battalion sectors of the 716th Division became regimental sectors. The 726th Regiment of the 716th was attached to the 352nd, less the 2nd Battalion which became division reserve for the 716th. One regiment of the 352nd plus the Füsilier Battalion was held in corps reserve in the vicinity of Bayeux.72

Hitler, whose ideas, possibly under Rommel’s influence, had undergone some change since Directive 51, wondered at this time whether all units of limited mobility which were located immediately behind the coast should not as a matter of policy be incorporated in the main line of resistance (MLR), leaving only fully mobile forces as attack reserves. General Jodl of the OKW pointed out that, except for three divisions, units were already far enough forward for their artillery to bear on the invasion beaches. To shift all troops into the coastal fortifications would be dangerous since concrete shelters were limited and field work might be destroyed by Allied bombing in Brittany and the Cotentin, moreover, it was necessary to preserve some depth of defense in order to resist probable airborne landings.73

Commitment of all forces at the MLR was thus not accepted as a principle. But in practice Rommel continued to shift the weight of his army forward. In April the 21st Panzer Division was moved from Rennes to Caen where its battalions were split on either side of the Orne River and its artillery committed on the coast. The disposition to all intents removed the 21st Panzer Division as a unit from the pool of mobile reserves.74 The other two panzer divisions directly under Rommel’s command were placed in position to reinforce the Fifteenth Army, one between Rouen and Paris, the other near Amiens. In May, another inspection tour convinced Rommel that movement of units from right to left into the invasion area would be impossible. He therefore requested that the four divisions in OKW reserve be assembled nearer the coast. Rundstedt entered an immediate protest with OKW, contending that the move was tantamount to committing the reserves before the battle. OKW agreed, and Rommel’s proposal was turned down.75

These four divisions (three panzer and one panzer grenadier) thus saved by OKW’s intervention were the only mobile units in the west on the eve of invasion which could properly be designated strategic reserves. Three were located within easy marching distance of Normandy (easy, that is, if the Allied air forces were discounted); the fourth was far away on the Belgium-Netherlands border.

In summary, the conflict between Rommel’s and Rundstedt’s theories of defense was never resolved definitely in favor of one or the other and led to compromise troop dispositions which on D Day were not suitable for the practice of either theory. The pool of mobile reserves had been cut down below what would be needed for an effective counterattack in mass; it had been removed from OB WEST’s control, and, as though to insure finally that it would not be employed in force, it had been divided among three commands. While the possibility of seeking a decision by counterattack had thus been whittled away, considerable forces were still held far enough from the coast so that, if Rommel’s theories were correct, they would be unable to reach the battlefield in time to influence the action. In short, operational flexibility had been curtailed without achieving a decisive thickening of the coastal defense.

The Defense on the Eve of Invasion

The scheduled completion date for the winter construction program and all troop preparations for meeting the expected invasion was 30 April.76 Up to that time the Germans made all arrangements to repel a major attack against the Kanalküste. At the end of 1943 Hitler ordered the assembly of all available forces behind the front of the Fifteenth Army and the right wing of Seventh Army, but the latter sector was to be considered much less in peril. OB WEST was to release four divisions from coastal sectors of the Seventh, First, and Nineteenth Armies. Of these, the 243rd Division, released from Seventh Army, was to remain as a reserve division in the army area. The other three were all attached to Fifteenth Army. Similarly, of four reinforced regiments obtained at this time from the Replacement Army, three went to Fifteenth Army; one was attached to the 709th Division. The latter attachment was made because the coastal defenses of the 709th Division were thin and enemy attack there was “possible.”77

That possibility, however, was not taken very seriously until the end of April. Since the German intelligence system had been supplying very little reliable information, estimates of Allied intentions continued to be based more on logical inference than on fact. Air reconnaissance was severely restricted by Allied air supremacy. Reconnaissance by sea could never be depended on. German agents in England steadily dwindled and the work of those remaining was made almost fruitless by the closing off of the English coastal areas in April 1944. News filtering through neutral countries, especially from Portugal and Switzerland, was abundant but confusing.78 The difficulty

was not that no reliable reports got through, but that they were too few and too spasmodic to allow the formation of a convincing picture of Allied intentions, particularly since such a picture had to compete for acceptance with various preconceptions.

The best guess was Hitler’s, though how he arrived at it the records do not show. While military leaders were nearly unanimous in predicting invasion in the Pas-de-Calais area, Hitler in March suddenly decided that the Allies were likely to land on the Cotentin and Brittany peninsulas. He believed they would be tempted by the ease with which defensible bridgeheads could be established there, but he apparently did not undertake any analysis of the possible military advantages.79

The supposition of a special threat to Normandy and Brittany received some support a few weeks later from the Navy. On 26 April Admiral Krancke, Commander of Navy Group West, observed that recent air photographs showed no activity in the ports of southeast England or the mouth of the Thames, and concluded that Cap Gris Nez and the coast northeast were not threatened by Allied landings. The conclusion was reinforced by the facts that Allied air attacks against coastal batteries and radar installations were concentrated between Boulogne and Cherbourg, that Allied mine sweeping and mine laying generally blocked off the same area, and that the bombing of railroads had interrupted traffic to the Channel coast but had not affected communications with the Atlantic area. In short, Admiral Krancke felt that all signs pointed to an invasion between Boulogne and Cherbourg, probably with the main effort against the Cotentin, the mouth of the Seine, or the mouth of the Somme.80 This appreciation differed from previous estimates only in lopping off the Pas-de-Calais sector between Boulogne and Dunkerque as a possible landing area. The resulting difference in emphasis, however, was striking, particularly in the singling out of the Cotentin as threatened by a possible major attack. Later reports by Admiral Krancke further emphasized this threat, particularly from Allied airborne attack.81 Krancke’s view, developed chiefly during May, was that Le Havre and Cherbourg seemed likely prime objectives for the Allied invasion forces. This conviction grew as it was seen that Cherbourg and Le Havre alone of the major French ports had been spared from heavy air attack.

Whether Hitler saw and reacted to these naval estimates or whether he had access to other information, in late April his interest in Normandy increased and he began to insist strongly on the need to reinforce the defense there.82 On 6 May

Seventh Army was notified by Rommel of Hitler’s concern, and the army ordered the deployment of one parachute regiment and two separate battalions in the immediate vicinity of Cherbourg. The parachute regiment selected was the 6th and it was to be placed in the general area of Lessay–Periers. The 206th Panzer Battalion, a separate tank battalion equipped with a miscellany of Russian, French, and German light tanks, was ordered to dig in between Cap de la Hague and Cap de Carteret. The Seventh Army Sturm Battalion was sent to la Haye du Puits and later shifted to le Vast, southeast of Cherbourg. Decision was made at the same time to divert to the Cotentin the 91st Division, which was then on its way from Germany to Nantes. Orders were issued the next day switching the trains to the vicinity of la Haye du Puits. The 91st Division was told that on arrival it would take over command of the 6th Parachute Regiment. This movement was completed on 14 May. On 9 May Rommel ordered that the 101st Stellungswerfer Regiment, released from OB WEST reserve, be committed in the Cotentin, split between the east and west coasts. On the day that this move was completed, 12 May, the 17th Machine Gun Battalion (a well-trained unit of young men) also completed relief of the 795th Georgian Battalion on Cap de la Hague and the latter battalion, under command of the 709th Division, was moved on 17 May south to Brucheville northeast of Carentan. Mission of all the major units, the 91st Division, 6th Parachute Regiment, and Seventh Army Sturm Battalion, was defense against airborne landings. The 100th Panzer Replacement Battalion south of Carentan at the same time was instructed to be prepared for action against airborne troops.83

The Cotentin was thus substantially reinforced and fully alerted a month before the two U.S. airborne divisions were dropped there. While expecting airborne assault on the Cotentin, however, neither Rommel nor Rundstedt reckoned that such assault would form part of the main Allied effort. Having reinforced the actual garrison in the peninsula, therefore, they took no further steps to cope with a major landing in the area. On the contrary, a Seventh Army proposal on 5 May to shift the whole of the LXXIV Corps from Brittany to Normandy in case of large-scale landings in the LXXXIV Corps sector was rejected by Field Marshal Rommel.84 No reserves were moved nearer the Cotentin, and no plans were made to move them in mass in case of attack.

As for the Navy, having called its opponent’s trumps it relaxed under the curious delusion that the Allies might not play at all. Krancke’s thesis seems to have been that unless the invasion were preceded by large and devastating attacks on

the coastal batteries it could not succeed.85 He noted on 31 May that such attacks had indeed increased, but they were, he thought, still too limited to insure the success of landings. Actually, from his point of view, he was right. Despite his prognostications about the threat to the Cotentin he continued to believe that large-scale landings would strike the Pas-de-Calais. Here the coastal batteries were formidable. The Allied air attacks had hit them more often than they had hit any other sector of the coast, and yet the attacks up to the eve of D Day had eliminated only eight guns. In the Seine-Somme sector five had been destroyed, and three in Normandy.86 The Navy thus remained confident that its artillery could still knock the Allied invasion fleet out of the water—provided of course it sailed where it was expected. That confidence was further nourished by the fact that, despite heavy air attacks on radar stations, the radar warning system remained virtually intact as of 31 May. In fine, reviewing the situation on 4 June Admiral Krancke was driven to the conclusion that not only was attack not imminent but there as a good chance that observed Allied preparations were part of a huge hoax. The mixture of bluff and preparation for a later invasion would keep up, the naval chief thought, until German forces were so weakened in the west that landings could be attempted without great risk.87

The contrast between Krancke’s optimism about enemy intentions and his sober accounting of the helplessness of his own forces in the face of enemy overwhelming superiority was the most striking aspect of his last report before the invasion. His fleet of combat ships was so small that it could scarcely be talked about in terms of a naval force and even what he did have was for the most part bottled up in the ports by what he called “regular and almost incessant” Allied air sorties. His main offensive units in June were a flotilla of destroyers (which on 1 April had two ships operational),88 two torpedo boats,89 and five flotillas of small motor torpedo boats (S-Boote) with thirty-one boats operational. In addition he had a few mine sweepers and patrol craft. Fifteen of the smaller submarines based in French Atlantic ports, though not under Krancke’s control, were scheduled to take part in resisting the invasion. Midget submarines and remote-controlled torpedoes were being developed but they never got into the fight.90 Even this tiny fleet could not operate. Krancke reported thirty Allied air attacks on his naval forces during

May and added that even in dark nights his units got no relief. He predicted an enforced reduction of effort and heavy losses in the future.91 In the meantime he found himself unable to carry out his plan for blocking off the invasion coast with mine fields. Delivery of all types of mines had been delayed chiefly by transportation difficulties. Up to the end of April there were on hand only enough concrete shallow-water mines to put in two mine fields in the Dieppe area.

In May, more mines became available. But in the meantime the mine-laying fleet had been depleted by Allied attacks, and increased Allied air surveillance of the sea lanes made all German naval activity difficult.

“The anticipated mining operations [Krancke reported on 4 June] to renew the flanking mine fields in the Channel have not been carried out. On the way to the rendezvous at Le Havre T-24 fell behind because of damage from [a] mine, “Greif” was sunk by bombs, “Kondor” and “Falke” were damaged by mines, the former seriously. The 6th MS-Flotilla [mine layers] likewise on its way to Le Havre to carry out KMA [coastal mine] operations reached port with only one of its six boats, one having been sunk by torpedoes and the other four having fallen out through mine damage, air attack or sea damage. The laying of KMA mines out of Le Havre therefore could not be carried.”92

In fact during the month only three more coastal mine fields could be laid and all these were put down off the Kanalküste. The essential mining of waters around the Cotentin could scarcely be begun. Naval defense preparations were actually losing ground. The program of replacing the 1943 mine fields in mid-Channel finally had to be abandoned in March 1944 because of lack of mines and because of Allied radar observation. Krancke estimated that the deep-water fields would all be obsolete by mid-June. Some hasty mine fields were laid in the Bay of the Seine during April but their estimated effective life was only five weeks. The dearth of materials and adequate mine layers continued to disrupt German plans. Krancke’s conclusion on the eve of invasion was that mining activity of E-boats could only provide a “nonessential” contribution to the German defenses.93

If Admiral Krancke’s forces were helpless in naval action, they were scarcely more effective on land, where their assigned task of casemating coastal batteries dragged along past the completion date with no end in sight. Hitler had ordered in January that all batteries and antitank guns were to be casemated by 30 April.94 On that date Admiral Krancke reported that of 547 coastal guns 299 had been casemated, 145 were under construction; remaining concrete works had not been begun. Like all other defense preparations, this effort had been concentrated along the Kanalküste. In the Pas-de-Calais and Seine-Somme sectors, 93 of the 132 guns had been casemated. Normandy had 47 guns, 27 of which were under concrete at the end of April. As for the fixed antitank positions, 16 of the 82 guns had

been covered in the Fifteenth Army area. The nine guns in the Seventh Army sector were all open.95

The Army’s construction program, of course, suffered along with the Navy’s and was far from completion on D Day. Shortage of materials, particularly cement and mines, due both to production and to transportation difficulties affected all fortification work. The shortage of cement, critical even at the outset of the winter construction program, was greatly intensified by the Allies’ all-out rail bombing offensive. Late in May LXXXIV Corps, for example, received 47 carloads of cement in three days against a minimum daily need of 240 carloads. Two days after this report was made, the flow of cement to the Seventh Army area stopped altogether as trains had to be diverted to carrying more urgently needed ordinary freight. During May the cement works in Cherbourg were forced to shut down for lack of coal. Plans were then made to bring up cement by canal to Rouen and ship by sea to the Seventh Army area, but this was a last-minute solution and could never be tried out.96